Abstract

Two-dimensional (2D) materials have garnered momentous consideration owing to their inimitable structural and physiochemical properties, enabling diverse technological applications. Tungsten disulfide (WS2), a prominent transition metal dichalcogenide, exhibits exceptional characteristics such as a tunable bandgap, large surface area, and strong biocompatibility, making it highly suitable for biosensing applications. This review explores various WS2 synthesis techniques, including mechanical exfoliation, sonication, and chemical exfoliation, highlighting their impact on nanosheet quality and scalability. Furthermore, it examines WS2’s role in biosensing, particularly in cancer biomarker detection, DNA/RNA sensing, enzyme activity monitoring, and pathogen identification. Despite its promising applications, challenges such as oxidation, long-term stability, and large-scale synthesis persist. Future advancements in hybrid nanostructures, functionalization techniques, and AI-assisted biosensing are expected to enhance WS2’s reliability and expand its practical deployment. By addressing these challenges, WS2-based technologies can drive significant innovations in diagnostics and environmental monitoring.

Keywords: Tungsten disulfide (WS2), Biosensing, Transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDs), Synthesis methods, Hybrid nanostructures, AI-assisted biosensing, Environmental monitoring, Diagnostic applications

Introduction

In the last decade, two-dimensional (2D) materials have captured significant interest due to the exceptional structural and physiochemical characteristics which they possess. These materials, composed of atomically thin layers, possess a unique two-dimensional atomic arrangement, which has made them highly versatile. Their outstanding properties like high surface area, flexibility in tuning electronic and optical characteristics and exceptional mechanical strength, have positioned them as valued tools across a wide range of technical and industrial disciplines [1]. From microchip technology and energy storage to catalysis and biosensing, the diverse potential of 2D material has sparked considerable enthusiasm within the global research community, leading to ground-breaking advancement and innovation applications across multiple domains [1].

2D materials serve as a dynamic building block for creating heterostructures that exhibit a wide spectrum of properties like numerous bandgap choices, absence of dangling bonds, excellent agility at atomic layer thickness, and high optical absorption while transparent [2]. These one-atom-thick crystals belong to a rapidly growing family of materials that span a vast array of characteristics. Graphene, the first discovered, is a zero-overlap semimetal that sparked interest in 2D materials. Since then, this family has expanded to include metals like NbSe2, semiconductors such as MoSe2 and insulators like hexagonal boron nitride (hBN) [3]. Many of these materials are stable under normal environmental conditions and techniques have been developed to handle those that are more reactive. Remarkably, the behaviour of 2D materials generally differs from their bulk i.e. their three-dimensional counterparts, which offers new possibilities for studies. Additionally, even well-established phenomena such as superconductivity or ferromagnetism present new complexities in 2D systems, where lack of long-range order raises interesting scientific questions [4].

While there have been remarkable advancements in the study of 2D materials, several significant challenges continue to impede their full industrial potential. Achieving large-scale production with consistent high quality and precise structural control remains elusive. The ability to fine-tune various parameters such as composition, thickness, lateral size, crystal phase, doping levels and surface characteristics is crucial to fully understanding how these factors influence the material’s properties [5]. The need to address defects, strains and vacancies further adds complexity to the development of these materials.

Additionally, the success of layered 2D material has sparked interest in two-dimensional nanomaterials such as 2D metals and perovskites. These materials are anticipated to exhibit similarly intriguing properties, making them promising candidates for future research. Their most capable applications are in areas like electronics, storage of energy and environmental monitoring which further reinforce the importance of expanding the scope of study beyond traditional 2D materials.

The continuous efforts and interdisciplinary collaboration within the scientific community will likely lead to significant breakthroughs in this area, paving the way for the eventual commercialisation of 2D materials in everyday technologies. This themed issue aims to bring through recent developments in the 2D material field, offering insights into a wide array of research topics and setting the stage for future innovations [6].

Recently, a developing scientific body of research has focussed on 2D nanosheets derived from transition metal dichalcogenides (TMD), including materials like MoS2, WS2, TiS2, TaS2, MoSe2, MoTe2, TaSe2, NbSe2, NiTe2 and BiTe2. These materials had garnered peculiar interest due to their unique structural characteristics. TMDs are arranged in closed-pack triangular layers, which are arranged along the (0, 0, 1) direction. Within this structure, every coating of the metal is encapsulated amid the layers of chalcogenide atoms, creating edge-sharing octahedral configurations.

The multi-layered nature of TMDs held intact by the Van der Waals force of interaction amid the atoms of chalcogenide which imparts unique properties to these materials [7]. One of the key features of this arrangement is that it allows the layers to be easily separated or cleaved along their basal planes, providing a level of flexibility in their applications. This structural flexibility, combined with the interesting electronics and mechanical properties of TMDs, has led to their increased exploration in fields such as electronics, catalysis and photonics [8].

Just like graphene, TMDs which are layered can be made up of single or few-layered nanosheets, which describe unique developing physical features which are completely dissimilar from those of their bulk counterparts. Till today, numerous methods have been executed in order to acquire 2D TMD films, which include particularly alkali metal embolism, mechanical cleavage exfoliation, chemical vapour deposition as well as wet-chemical synthetic methods [9]. One of the most peculiar TMD metals used after MoS2 is WS2. Owing to its several properties, it is extensively expended in numerous applications.

WS2 is composed of multiple layers which are bonded by Van der Waals force of interaction between chalcogenide atoms i.e. Sulphur (S) this type of configuration allows WS2 to be readily cleaved along the basal planes. WS2 has many distinguishing physical properties like transition of direct to indirect band gap, strong spin–orbit splitting, large excitation binding energy, valley selection rule etc. Due to these properties, WS2 is used in numerous applications like transistors, diodes, LEDs, photodetectors, pulsed lasers etc. [10]. Tungsten Dichalcogenides have garnered a considerable amount of attention due to the bigger magnitude of Tungsten (W), which can alter the 2D structure. Though tungsten is a heftier element its natural abundance is slightly higher than that of Mo. As of now though there are lower amount of mineral resources but engineering utilization of Mo is developed. This is what sets W i.e. Tungsten more suitable for industrial applications [11].

The nanosheets of WS2 are considered to be of great importance in various applications. At an unintended band gap of 1 eV, the bulk materials of WS2 are semiconductors. Upon the formation of nanosheets, this indirect gap turns into the direct gap of 1.8–2.0 eV that enables the application of WS2 in transistors and various other applications. WS2 nanosheets have been manufactured by sonication, the Scotch tape method, lithium intercalation and chemical vapour deposition by means of metal oxide or precursors [12].

Analytical devices like biosensors consist of biological sensing elements. It is used in the detection of a chemical substance, which is a combination of a biological component with a physiochemical detector. Biosensors intention to employ the power of electrochemical methods for biological procedures by quantitatively manufacturing a indication that relays to the concentration of a organic analyte [13]. Biological elements can be tissues, micro-organisms, organelles, enzymes, antibodies, nucleic acid, etc. These are biological elements that are combined with the analyte under study [14]. Biosensors consist of 3 elements Transducer, Bio-receptor and electronic system.

The transducer changes one form of signal into another. It works in a physiochemical method, it can be optoelectronics, electrochemical, piezoelectric etc. [15, 16]. The bio-receptor is designed because when an effect produced by a specific analyte of interest can be measured by the transducer. Biosensors are classified based on the types of receptors involving interactions like antibodies/antigens, ligands/enzymes, nucleic acid/DNA, and biomimetic materials [17, 18].

Tungsten (W) is widely used in electrochemical biosensors. Its electrical conductivity can be enhanced by combining it with compounds with conductive properties such as gold, silver and platinum [19]. WS2 is used as a substrate in immobilizing species. WS2 nanomaterials show an excellent property of conductivity for its use in electronics and biosensors as well. WS2 nanotubes functionalized with the C-dots have shown considerable results for photothermal therapy and cell imaging [20]. Witnessing all the properties and applications of WS2 is one of the reasons to choose it as a material for this review paper.

With the advancement in modern technology, people have started to pay their utmost attention to their health and environmental protection issues. This review paper describes the advancements in biosensor technology, with a particular focus on the integration of 2D TMD material, notably tungsten disulphide (WS2) to enhance biosensing performance. The primary focus is on its significant applications in areas like medical diagnostics as well as environmental monitoring, where accuracy and sensitivity are paramount. By analyzing the exclusive characteristics of WS2, such as its huge specific surface area, adjustable bandgap and strong biocompatibility [19, 21]. Additionally, this review identifies the research gap and suggests future paths for expanding innovation in this field, contributing to the expansion of additional well-organized and widely accessible biosensor technologies. Overall, it aims to provide a detailed understanding of how WS2 can revolutionize biosensing systems for emerging applications. In addition to exploring WS2’s foundational properties, this paper discusses its integration with other nanomaterials and sensing mechanisms. By combining WS2 with other functional elements, such as polymers, metal nanoparticles or quantum dots, researchers can improve the sensitivity and specificity of biosensors [22].

Although WS2-based biosensors have been investigated in several research, the domain remains disjointed, characterized by diverse synthesis methods, sensor architectures, and application areas that frequently lack direct comparisons. Current reviews concentrate on either TMD materials broadly or specific features of WS2; nevertheless, a thorough study integrating WS2 synthesis methodologies, biosensing applications, related obstacles, and future possibilities remains absent.

This review comprehensively evaluates the synthesis methods of WS2 (e.g., mechanical exfoliation, sonication, and chemical exfoliation) and their effects on nanosheet quality and scalability, therefore addressing this gap. Furthermore, it integrates recent progress in biosensing applications while rigorously evaluating obstacles like as oxidation and stability. The article ultimately examines solutions to surmount these limits via hybrid nanostructures, functionalization methods, and AI-enhanced biosensing. This review seeks to offer a cohesive viewpoint to direct forthcoming research and technological advancements in WS2-based biosensors, facilitating improved diagnostics and environmental monitoring applications. The paper also addresses the need for continued research into scalable production methods for WS2 ensuring high-quality material suitable for widespread adoption in biosensors. Furthermore, challenges like long-term stability, reproducibility and efficient coupling with electronic devices are analyzed [23, 24]. Future research directions are proposed to overcome these obstacles, with a particular focus on novel fabrication techniques and surface engineering to enhance WS2’s performance in diverse environments. This review not only underscores WS2’s transformative impact on biosensing but also presents a roadmap for future innovations. As technology advances, WS2 is positioned to play a remarkable role in the creation of the next-gen biosensors, with diverse applications in both health as well as environmental fields like e-skin, which has diverse applications in human–machine interfaces, robotics and AI [25].

Fabrication techniques of WS2

It’s quintessential to choose the appropriate method during the synthesis of WS2. Various methods used during the synthesis of WS2 are due to the requirements of the metal as well as the properties which set it apart. Various approaches are used to achieve the above goals few of them are mentioned in the diagram.

The top-down method is one of the size reduction techniques or physical procedures. The top-down method is used to produce nanostructured material from its bulk [26]. In the top-down approach for the bulk materials lateral patterning is done by either of the methods subtractive or additive so as to comprehend nano-sized structures. In the bottom-up method, the fabrication of nanostructures is done by building upon single atoms or molecules. Here, there is measured segregation of atoms which happens as they gather into an expected nanostructure (2–10 nm) [27].

Top-Down methods

There are several techniques included in a top-down approach. In this review, we will be dealing with mainly 3 techniques.

Mechanical exfoliation

The exfoliation is most appropriate way for the manufacturing of nanosheets [28]. To date, mechanical exfoliation is one of the most effective habits of producing the freshest, extremely crystalline as well as atomically thin nanosheets of layered materials. The basic principle of mechanical exfoliation is interfacial peeling and intralayer tearing processes which completely depend upon the properties of the material, geometry and the exfoliation kinetics [29]. During a conventional mechanical exfoliation process, from the bulk crystals thin TMD crystals are peeled off on the tape and are then placed onto a target substrate and further cleaved by rubbing them with tools such as plastic tweezers. As there is removal of the scotch tape, the substrate is left with 1L and multilayer TMD nanosheets[30]. Graphene has garnered a great interest because of the eclectic properties which it possesses. However, it is difficult to use because of its gapless band structure for conventional transistors and logic circuits which are used in electronic switching at room temperature [30]. TMDC materials like WS2 have sizable bandgaps which generally interchange from secondary to primary in single layers, that allows them to be utilized in the purposes such as transistors, photodetectors as well as electroluminescent devices [31]. Mechanical exfoliation (ME) produces the highest quality materials but its application is because of very low and uncontrollable yield [32].

There are several techniques by which mechanical exfoliation can be attained to produce WS2. In this review will be discussing about 3 major techniques mentioned as follows:

Scotch tape method

In the Scotch Tape Method, a bulk sample of WS2 is applied to the scotch tape which is grown through the chemical vapour transport method [33]. In the scotch tape method, we apply mechanical forces to the bulk sample of WS2 and eventually removes the thin sheets. Then a substrate is applied to the sheets, which leaves behind fine flakes of different sizes as well as thicknesses [34]. WS2 possesses a layered crystal structure. In the layered crystal structure, each of the layers consists of three atomic planes. Every atomic plane has hexagonal packed atoms, the Tungsten (W) metal atom plane is exactly in between two planes of S atoms, which forms an S-W-S structure. There is exactly 0.65 nm of distance between each layer. Dangling bonds do not exist upon the surface of every layer, due to this surface becomes nonreactive as well as very stable. Van der Waals interaction is the reason these layers are intact together. As the Van der Waals force of interaction is weak, the scotch tape can be used to exfoliate the crystals of WS2 mechanically [35].

Sonication

Sonication is the procedure in which sound energy is applied to excite and remove the particles in the bulk sample of the material, for various purposes like the preparation of nanoparticles from the bulk sample of a material. For this purpose, ultrasonic frequencies are used i.e. (> 2 kHz). Therefore, this process is also known as ‘Ultra-sonication’ [36]. Figure 1 below shows the synthesis of WS2 quantum dots by facile ultra-sonication method from hydrothermal synthesized hydrothermal powder. When we apply sulfuration further the number of defects in it would be reduced and the electrical properties of WS2 will be improved significantly [37].

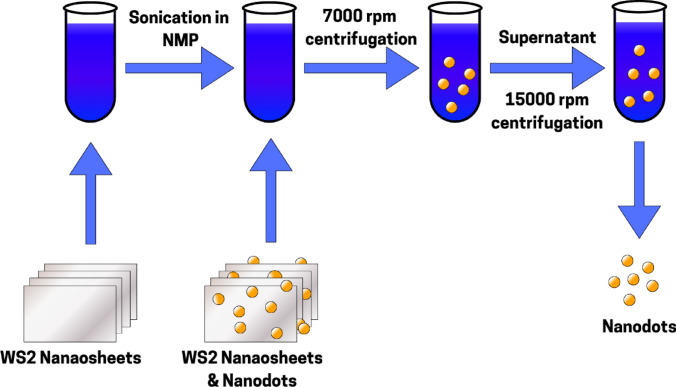

Fig. 1.

The graphic illustrates the manufacturing procedure of WS2 quantum dots. Initially, WS2 nanosheets are exfoliated through sonication in NMP, followed by stepwise centrifugation at 7000 rpm and 15,000 rpm. This sequential process separates nanosheets and nanodots, ultimately isolating WS2 nanodots for further applications

Ball milling

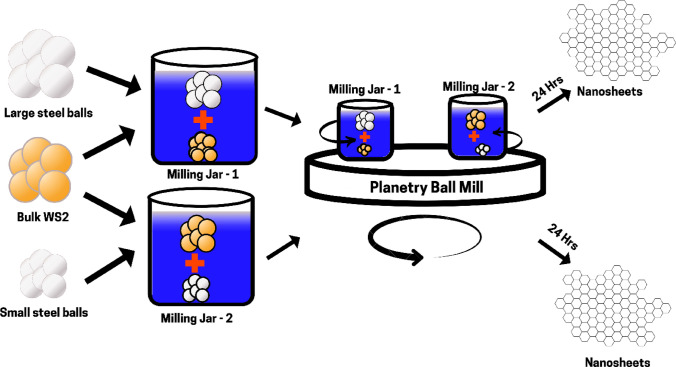

In this process an instrument named ‘ball mill’ is used. Ball Mill is a type of grinder that contains grinding balls that are used in order to grind or blend the materials. The principle of ball mill working is impact and attrition i.e. the size of the sample of the bulk is reduced by dropping the ball from the top of the shell [38]. During WS2 synthesis, the commercial WS2 powder (Wc) (2 g) and chromium steel balls (20 g) are added to the milling container. As a solvent Ethanol (30 ml) is added into the milling jar to increase the efficiency of milling. A high-energy planetary ball milling mechanism is loaded by the milling jars. At room temperature, the WS2 powder is milled using two different milling balls of size 0.5 mm and 7 mm for 24 h at a milling rate of 364 rpm. As shown in Fig. 2, the steel balls are taken out and the suspension that is created is kept for drying for 4 h at 50 °C to get the final product i.e.WS2 nanosheet [39].

Fig. 2.

The diagram outlines the ball milling process for the synthesis of WS2 nanosheets. Bulk WS2, combined with either large or small steel balls, is placed into a milling jar. The jars are subjected to high-energy planetary ball milling for 24 h. This mechanical grinding process exfoliates bulk WS2 into nanosheets, which are collected and used for further applications in nanotechnology and material sciences

These were a few methods by which mechanical exfoliation is done in order to exfoliate WS2 to produce its nanosheets.

Liquid-phase exfoliation

Generally, liquid-phase exfoliation is time-consuming, extremely sensitive to the environment and incompatible with most solvents [39]. Liquid Phase Exfoliation is a solution processing method. It helps in converting layered crystals into 2D nanosheets in bulk. It is considered one of the important methods in order to produce 2D nanosheets. In liquid-phase exfoliation, we add powdered layer crystals to precise solvents and insert energy either by ultrasonication or high-shear mixing. Due to energy addition, it makes a combination of fragmentation and exfoliation which causes the small nanosheets to erode from the layered crystals [40]. There are various techniques to exfoliate WS2 into nanosheets like sheer exfoliation, sonication-assisted exfoliation, electrochemical exfoliation etc.

During WS2 liquid-phase exfoliation we take WS2 in powder form. Then we sonicate WS2 (40 mg) powder in 10 ml of NH3 aqueous solution(50% v/v) with the help of the sonic tip of the horn probe for nearly 3 to 4 h at 750 W and at an amplitude of 20%. The tip pulse was set to five sec ON and two sec off, in order to avoid damage during processing as well as to minimize heating of the solution. In the water bath cooling arrangement, in order to keep the temperature at 5 degrees, sonication was carried out. The dispersion that was attained after sonication was provided to the centrifuge tubes and centrifuged at 3000 rpm to 8000 rpm so as to eradicate aggregates. As shown in Fig. 3, the supernatants are carefully collected at the top to avoid the withdrawal of precipitated bulk particles. Colors which range from brown to yellow of supernatants which depend on the centrifugation speed are obtained. As a result, the sediments with greater configuration speeds, thick and large sheet sediments as well as supernatants with thin as well as small nanosheets remain at the peak. Thus the nanosheet of WS2 is obtained during liquid-phase exfoliation [41].

Fig. 3.

The schematic illustrates the liquid-phase exfoliation process for synthesizing WS2 nanosheets. Bulk WS2 is dispersed in a suitable solvent and subjected to shear forces through sonication or ball milling with steel balls. This process promotes exfoliation, breaking the bulk material into thinner nanosheets. After 24 h of milling or sonication, the nanosheets are separated and collected for various applications in nanotechnology

Chemical exfoliation

We can prepare WS2 nanosheets by chemical exfoliation method. The general process of chemical exfoliation of WS2 is mentioned as follows:

In a flask which contains 5.1 mL of concentrated HCL (Hydrochloric acid), 2.0 g nitrate was added to it. The solution is then shaken well. Thereby, 0.4 g of WS2 is added to it. The mixture is then passed through the process of ultrasonication at 25–35 degrees for nearly 30 min so that the toxic gas collecting is set up. Water is added to the reaction. Thereafter, the centrifugation of the reaction mixture takes place at 1000 rpm for nearly 30 min to eradicate the thick WS2 sheets. At last, the centrifugation of the supernatant portion takes place at 8000 rpm for thirty minutes and the precipitated nanosheets of WS2 are obtained [42].

Bottom-Up method

In this method to the fabrication of WS2, nanostructures are made-up by building upon single atoms or molecules. In the bottom-up approach, there occurs a measured seclusion of atoms and molecules, as these atoms and molecules are assembled into desirable nanostructures with a size variety from 2 to 10 nm. In general, the bottom-up production method takes place in two stages i.e. gas-phase synthesis and liquid-phase formation [27]. In short, the bottom-up method is classified as the self-assembly of atoms and molecules into nanostructures [43]. This review presents two bottom-up methods Chemical Vapour Deposition (CVD) and Sol–Gel Process.

Chemical vapor deposition (CVD)

CVD is a material-processing technique that involves the development of thin films on a heated substrate by a chemical reaction of gaseous precursors. CVD depends on chemical reactions that provide modifiable deposition rates and yield superior products with superior conformance [44]. CVD offers several advantages, including relative simplicity, a variety of precursors, and a rapid development rate. This enables a result for the hands-on implementation of wafer-scale synthesis of two-dimensional atomic layers on diverse substrates. In 2008 and 2009, various wafer-scale synthesis techniques utilizing graphene and other metals were established [45]. Numerous investigations have identified high-quality 2D materials and associated heterostructures with scalable dimensions, adjustable thickness, and superior physical and chemical properties by the CVD process. The primary objective of CVD growth is to produce low defect density, large-area 2D materials that exhibit quality comparable to their exfoliated equivalents, while allowing for fine control over layer count, domain size, and morphology. The CVD process comprises the excitation of precursors to the requisite vapor phase, the transit of reactive gaseous species, and a heterogeneous surface reaction on the substrate that yields solid phase materials [46].

The condition under which the reaction takes place plays a noteworthy part in forecasting the quality and characteristics of the resultant thin films. Temperature, precursor, concentration, pressure and carrier gas flow are the factors that must be controlled in order to achieve precise results. Advancements in CVD techniques like plasma-enhanced CVD (PECVD) and low-pressure CVD (LPCVD) have significantly increased the probability of producing materials with exceptional structures and characteristics, which ultimately enhances their application potential in numerous grounds like photonics, energy storing and catalysis.

CVD has emerged as one of the significant approaches for the synthesis of high-quality 2D TMD supplies, which includes Tungsten Disulphide WS2. WS2 is one of the peculiar materials for electronic and optoelectronic appliances and benefits significantly from the versatility and precision of the CVD process. The controlled environment in CVD allows the growth of the WS2 layer systematically with adjustable properties like layer thickness, crystal size and defect density which are crucial factors in judging the performance of the device.

Several methods of CVD Metal Organic Chemical Vapour Deposition (MOCVD) for WS2.

Deconstructed’ MOCVD growth of WS2 on Au

In this method, 25 µm Au foils with a purity percentage of 99.985% from Alfa Aesar were taken as the substrates. All the Au substrates which are received are annealed for 6 h at a temperature of around 1025 °C under a pressure of 800 millibars with H2: Ar = 1: 9. Before the development of the samples, the samples are treated with oxygen RIE (150 mTorr, 50 W, 5 min) in order to eradicate the surface carbon adulteration. All the ex-situ MOCVD growth is carried out in the cold-wall low-pressure furnace for MOCVD. For the purpose of sample heating, 808 nm continuous wave IR laser is used. 1.6 µm IR pyrometer by assumptive transmission 0.9 and 0.2 emissivity was used in order to monitor sample temperature during growth. Approximately 50 °C us was estimated as the temperature measurement error. The sample is heated to 700 °C under the base pressure of 3 × mbar for 15 min to anneal and stabilise the system. W was sublimed at 120 °C and fed into the system as a Tungsten precursor during metallization, after annealing. The leak valve is used to control the partial pressure of W , which allows a pressure control precision better than 5 × bar. 5 × bar. W was in applied to the chamber and exposed to Au foil at 700 °C for nearly 5 min, after metallization. Later, 5.5 × mbar is applied in order to stabilize the base pressure when S was given into the system as an S precursor in the process of sulfidation. Again the leak valve is used to control the partial pressure of S . For sulphidation of different samples in order to equivalence its impact on WS2 produced S with measured fractional pressure extending from 0.01 to 1 mbar was presented. At last, for further characterization after sulfidation, the sample is cooled down rapidly [47].

Sol–Gel process

The development of sol–gel technologies acts as a substitute for the groundwork of glasses and ceramics at significantly low temperatures [48]. The sol–gel name itself indicates, that it involves sol formation thereby the formation of gel, as can be seen from Fig. 4, which is mainly used for colloidal dispersions or inorganic precursors as the base material [49]. During the early development of sol–gel chemistry, the method was particularly based on simple, easily available precursors, the great capability of new precursors which are chemically altered for special applications is greatly felt. This method offers a wide availability of ceramics and glasses with improvised properties [50]. Sol–gel technology is also used as an alternative pre-treatment for the corrosion of metals [51].

Fig. 4.

The diagram represents the stages in the sol–gel process for synthesizing nanostructures. The procedure starts with the research of a precursor solution, typically a metal alkoxide or inorganic salt, which undergoes hydrolysis and condensation to form a sol. The sol then transitions into a gel-like network, leading to the formation of a wet gel. This gel is further dried ad subjected to calcination or sintering, resulting in the desired nanostructures with measured morphology and properties

In short to describe, the sol–gel as well as the Chemical Solution Deposition method are low-temperature, nanomaterial production methods where there is production of solid materials with the help of its small molecules. In this method sols are generated inside a liquid then they later are connected to form the gel network. Then there is evaporation of liquid thereby leading to powdered thin-film formation [52].

Sol–Gel method for WS2 synthesis

The sol–gel procedure generally begins with the preparation of the precursors. Precursor often consists of a metal salt like metal alkoxides and metal chlorides i.e. tungsten chloride or tungsten alkoxide which is dissolved in an appropriate solvent [53]. A source of sulphur like thiourea or thioacetamide is added thereafter to the solution in order to introduce sulphur atoms required for the formation of WS2Error! Bookmark not defined.Then the solution undergoes hydrolysis and polycondensation reaction which gives rise to the formation of a gel-like network that contains the precursors for WS2 [54]. During the gel formation stage, the precursors polymerise to produce a 3D network, trapping the solvent within the structure. The ageing process further solidifies the gel and it may also involve the evaporation of the solvent, which results in a stable structure with controlled porosity. During calcination the dried gel is taken and the heat treatment process is carried out in a controlled atmosphere, generally under inert gases or a reducing environment (like hydrogen gas or Ar/H mixture). This step ensures the conversion of precursors into crystalline WS2 while controlling the stoichiometry and phase of the material. This is how the sol–gel technique is handled in order to produce the crystalline WS2 using multiple sub-methods of production (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison of different fabrication methods

| Synthesis method | Advantages | Disadvantages | Typical applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mechanical Exfoliation | Simple, cost-effective, produces high-quality monolayers | Low yield, not scalable | Fundamental research, optical studies |

| Liquid Phase Exfoliation (Sonication) | Scalable, suitable for large-area processing | Sheet thickness control is challenging, defects may form | Ink-based biosensors, flexible electronics |

| Chemical Vapor Deposition (CVD) | Large-area uniform films, precise control over thickness | High temperature, expensive setup | Nanoelectronics, optoelectronic biosensors |

| Hydrothermal Synthesis | Low-cost, environmentally friendly, good crystallinity | Long synthesis time, impurities possible | Catalysis, environmental sensing |

| Chemical Exfoliation | Produces ultra-thin nanosheets, scalable process | Chemical residues, structural damage risk | Biosensing, electrochemical sensors |

| Sulfurization of Tungsten Films | Controlled growth of WS2 layers | Requires high temperature, complex processing | Thin-film transistors, high-performance sensors |

Structure and surface chemistry of WS2

If bio-sensing functions are taken into consideration, the structure and surface chemistry of tungsten disulphide (WS2) does a critical part in determining the presentation and its interaction with biological molecules. In this section of the review structure of WS2 and the surface chemistry of WS2 are discussed and its impact on the properties of WS2 as well as on its applications. The structure of tungsten disulphide is a layered structure containing of a metal layer which is sandwiched amongst two sulphur layers which forms a hexagonal cell in its most steady form which is sustained organized by Van der Waals forces [55, 56]. The WS2 (S = W = S) layers are disconnected by 0.62 nm distance and are consistently dispersed on either side [57]. WS2 exhibits trigonal prismatic structure [58]. The WS2 layers are stacked in an AA’ pattern, which means that the sulphur atoms in one layer are vertically aligned with the tungsten atoms in the adjacent layer. This type of arrangement increases the mechanical strength without compromising the flexibility of the material. Due to this, it become suitable for integration into various biosensing platforms which requires durability as well as responsiveness.

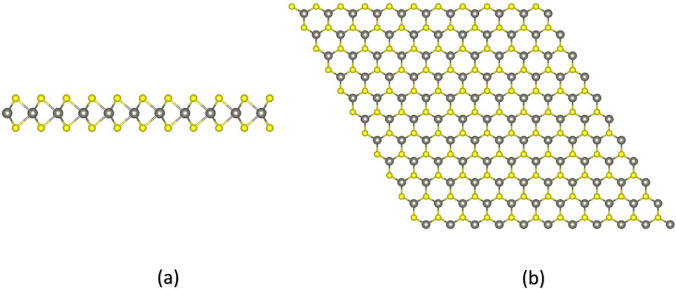

WS2 is a material which has high density and high molecular weight as shown in Fig. 5. WS2 also has a stronger spin–orbit interaction (SOI) i.e. numerous hundreds of millivolts in valance bands and tens of millivolts in conduction band [59, 60]. Hybridization of WS2 offers mesmerising mechanical, electrical and photonic properties for several uses [61]. WS2 has a bandgap of 1.3–2.2 eV which makes it attractive for photovoltaic applications. Due to its 2D structure, it is likely to alter its electronic characteristics by doping it with other atoms and molecules between the weakly bonded layers [62]. Due to the 1.3 eV indirect band gap, it exhibits oxidative and thermal stability as compared to MoS2. Electronically as well as structurally, monolayers of WS2 exhibit unique properties like high emission quantum yield, non-blinking photon emission, high spin–orbit coupling and high excitation binding energy [63]. The transition metal atoms i.e. M-M bond length is almost identical for MoS2 and WS2 i.e. 3.16 Angstroms and 3.15 Angstroms [58].

Fig. 5.

a Top view of WS2 and b Side view of WS2

WS2 appears in two more phases i.e. the semiconducting 2H phase and the metallic 1 T phase. These are the structural phases of WS22. In the 2H phase, the layers are stacked into an ABAB sequence. In the 2H phase, the trigonal prismatic coordination is observed and in the 1 T phase, the octahedral coordination is observed. Chemical Exfoliation is used in order to induce 2H and 1 T phase transition. Due to this, the electronic properties as well as the catalytic activities are significantly improved of the material. The 2H-WS2 and WSe2 are isotopic with 2H-MoS2. 2H is the most common and stable stacking structure of WS2 wherein, the W atoms of given layers are sitting exactly on top of the S atoms of its neighboring layer. Bulk and multilayer WS2 structures are indirect-gap semiconductors [30].

The Monolayer of WS2 degrades over time at room temperature [64]. The majority of the WS2 atoms have low vacancy density [65]. The oxidation of the monolayer of WS2 under the ambient condition is called as photo-oxidation process. WS2 operates with stability under environmental conditions so it is mostly favoured for numerous research and practical applications. Bulk tungsten disulphide WS2 is naturally in mineral form and called ‘tungstenite’. It possesses a hexagonal structure in which the layers in the structure are kept intact by weak van der Waals forces. The bulk WS2 is well known for its high lubricity, its thermal stability and its numerous semiconductor properties [66]. WS2 is highly suitable for biosensing applications due to its layered structure and unique electronic properties [67]. Due to WS2’s specific surface area, its ability to exfoliate into monolayers provides numerous active sites for biomolecule interaction [68, 69] (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparative evaluation of WS2 with other 2D materials in biosensing

| Property | WS2 | MoS2 | Graphene |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bandgap | Tunable (~ 1.4–2.1 eV) | Tunable (~ 1.2–1.9 eV) | Zero bandgap (semi-metallic) |

| Surface area | Large (~ 800 m2/g) | Large (~ 700 m2/g) | Very high (~ 2600 m2/g) |

| Electrical conductivity | Moderate | Moderate | Very high |

| Optoelectronic properties | Strong photoluminescence & high absorption | Strong photoluminescence | Poor photoluminescence, high carrier mobility |

| Chemical stability | Higher oxidation resistance than MoS2 | Prone to oxidation in ambient conditions | High stability, but susceptible to functionalization |

| Biocompatibility | Excellent for biosensing applications | Good, but less explored than WS2 | Requires functionalization for enhanced biocompatibility |

| Biosensing sensitivity | High, due to strong light-matter interaction | High, but slightly lower than WS2 | Good, but requires chemical modifications |

| Flexibility and mechanical strength | High flexibility, suitable for wearable sensors | Moderate flexibility | Extremely high flexibility and strength |

| Selectivity in biosensing | Enhanced selectivity due to high sulfur reactivity | Moderate | Can be tuned via functionalization |

| Application in biosensing | DNA/RNA detection, cancer biomarker detection, enzyme activity monitoring, pathogen sensing | Electrochemical biosensors, fluorescence sensors | Electrochemical biosensors, flexible bioelectronics |

By harnessing the structural properties of WS2, biosensors with better performance with respect to sensitivity, selectivity and stability can be developed. Designing advanced sensing platforms can be done by modulating their structure either by combining with other materials in heterostructures or by inducing phase transitions. It provides a promising aspiration of next-generation biosensing technologies by witnessing the unique layered structure of WS2 which comes with its properties like adjustable electronic and optical properties [70].

The surface chemistry of WS2 plays a crucial factor in its diverse applications like catalysis, sensing and energy storage. WS2 exhibits properties which are unique like tuneable band gap covering, which can be spotted by UV range, high level of absorption, high emission quantum yield etc. [71, 72] which are induced from its layered structure due to the presence of both sulphur and tungsten atoms on the surface. Due to the 2D nature of WS2 which in turn results in a high-surface-to-volume ratio this significantly increases the interaction of WS2 with external molecules [73]. This makes WS2 a suitable candidate for surface-related applications like biosensing.

There is a strong covalent bond between the atoms in the same layer and the layers are intact because of the weak van der Waals force of attraction. Basal face’s sulphur atoms are fully bonded so they are not reactive to ambient or the chemical reaction. Conversely, the chemical bonds of sulphur or tungsten atoms on the orthogonal prismatic crystal surface so the surfaces become chemically very reactive also oxidation and corrosion occur on them instantly [74].

Functionalization of WS2 surface

Various functionalization techniques have been implemented to enhance the surface chemistry and applicability of WS2. Here, functionalization involves modifying the surface with specific chemical groups to improve interaction with target molecules. A widely used technique for functionalization is thiol-based functionalization [75]. The thiol-based functionalization is significantly used to produce a strong covalent bond between the atoms which are present in WS2. Due to this ability of WS2 to attach to thiol-based molecules, it gives a wide range of parameter space of chemistries which are used for significant applications as well as sophisticated patterning [76]. It also improves its performance in biosensing applications. Functional groups like carboxyl, hydroxyl and amine are used to modify hydrophilicity and improve the solubility of various solvents which are used in various processes like catalytic processes [77]. By promoting the transfer of electrons between the WS2 surface as well as external molecules, surface functionalization is enhanced by the catalytic properties of WS2.

Chemical changes, including doping, hybridization, and nanocomposites, are essential for improving WS2-based biosensors. Doping with metals (e.g., Mo, Nb) or non-metals (e.g., N, P) enhances electrical conductivity and catalytic activity, hence optimizing signal transduction. Hybridization with graphene or MoS2 augments charge transport, whereas WS2-nanocomposites with gold or silver nanoparticles boost electrochemical and plasmonic sensing capacities. These alterations markedly improve sensitivity, selectivity, and long-term stability in biosensing applications. Nonetheless, WS2’s vulnerability to oxidation and degradation constrains its practical applications. Exposure to oxygen and moisture transforms WS2 into tungsten oxides, impairing its electrical characteristics. Ultraviolet-induced oxidation and reactive oxygen species (ROS) expedite deterioration. To mitigate this issue, surface passivation techniques like graphene encapsulation, polymer coatings (e.g., polydopamine), and self-assembled monolayers (SAMs) have been investigated. Surface changes rich in sulfur and thiol functionalization enhance stability in aquatic conditions. Furthermore, low-oxygen storage and WS2 stabilization in organic solvents augment sensor longevity. These methods significantly enhance the dependability, reproducibility, and commercial feasibility of WS2 biosensors, rendering them exceptionally appropriate for real-time, long-term biomedical and environmental monitoring applications. Additional investigation into scalable functionalization and stability methodologies is essential for the progression of WS2-based biosensing devices.

Defect engineering: creating active sites

There has been remarkable progress made in the last few decades, but the issue that remains unsettled and uncontrolled is the formation of defects during the growth of the material, which significantly degrades the growth of the material [78]. Defect engineering is one of the critical strategies for tunning the surface chemistry of WS2. Electronic properties of WS2 can be modified by defects like sulphur vacancies, edge dislocations or doping with foreign atoms by introducing the localized states in the bandgap [79, 80]. Due to the high reactivity of these defect sites, WS2 becomes more suitable for catalysis and sensing.

Active sites on WS2 by sulphur enhance adsorption significantly thereby making it an excellent element for gas sensing applications [81]. Due to sulphur vacancies not only there is an increase in the surface reactivity but also the material’s band structure is changed, which in turn improves charge transfer in numerous catalytic processes. Elements like nitrogen and oxygen when doped with WS2 enhance the electronic properties as well as reactivity of WS2, which creates more efficient sites for interaction with the analytes. Due to highly energetic active sites on the surface of WS2 undergo engineering for immobilization of bio-receptors, which play a vital role in biofunctionalization and biosensing applications [82]. Defects create highly sensitive biosensors because of the strong interaction between the sensor surface as well as biomolecules, which helps in the accurate detection of biological targets.

Phase transition and its influence on surface chemistry

Another important aspect of WS2’s surface chemistry is its ability to transform the phase between 1H (semiconducting) and 1 T (metallic) phases, which include atomic distortions as well as significant structural variations [83]. The 2H phase of WS2 which has trigonal prismatic coordination is most stable under ambient conditions. WS2 transitions to 1 T phase during chemical exfoliation or intercalation. 1 T phase has the most reactive octahedral coordination as it is formed by highly reactive metals and sulphur sources [84].

1 T phase has high electrical conductivity as well as active site which is helpful in catalytic and sensing applications. As Sulphur atoms increase in the 1 T phase it allows stronger interactions with other molecules which significantly improves sensor performance. 1 T phase has higher carrier mobility which is suitable for electrochemical sensors and other applications where there is a need for high charge transfer.

Oxidation and environmental stability

WS2’s surface reactivity is considered beneficial in numerous applications, but if oxidation is concerned it poses a great challenge. Oxidation in WS2 is evident in the ambient conditions and when it is brought into light the characteristic of laboratory conditions for weeks [85]. Due to oxidation, there is a formation of tungsten oxide W (O)2 on the surface of tungsten disulphide (WS2). Oxidation degrades the performance of the material in sensing and catalytic applications.

Various techniques are being used to mitigate this effect like encapsulating WS2 with protective layers of graphene or polymers which reduces oxidation and preserves the material’s surface properties [86]. Another method is controlling the degree of oxidation in order to create a stable oxide layer which can take part in catalytic reactions without hampering the performance.

Applications of WS2 in biosensing

2D TMD materials have captured significant attention due to their ultrathin sheet nanostructure and diversified electronic structure to achieve high performance among all parameters. Tungsten disulphide is emerging as one of the choices for biosensing applications because of the properties of WS2 in terms of direct band gap, stronger photoluminescence, greater mobility, magnetic field interaction well and better thermal stability. WS2 has numerous diverse applications like field-effect transistors (FET), in sensing etc. [87]. The properties that WS2 possesses such as large surface-to-volume ratio, tunable bandgaps well as strong interaction with biomolecules all these qualities make WS2 as a prominent choice for developing extensively sensitive and selective biosensors [88, 89]. In the past few decades, WS2 have exhibited remarkable properties by detecting numerous biological entities from small biomolecules such as glucose and cholesterol to very complex molecules like DNA, proteins as well as pathogens [90–92]. WS2 has given a rise in innovations in biosensing mechanisms as well as in improving detection limit and response time. In this section on applications of WS2 in biosensing, we will focus on its role in the detection method enhancing and expanding the possibility of real-time diagnostics.

Following are the emerging applications of WS2 in biosensing:

Cancer biomarker detection

Due to WS2’s distinctive structural and chemical properties there are significant applications of Tungsten Disulphide (WS2) in cancer biomarker detection. Cancer biomarkers are the specific molecules released into the body fluids by cancer cells or by the body in response to cancer, such as proteins, nucleic acids and small metabolites. Saliva is also a tumour source associated with nucleic acid, proteins and metabolites [93].

Accurate and early detection of these biomarkers is pivotal for diagnosing cancer at early stages, which leads to improving patient outcomes. As a member of the TMD family, WS2 has an added advantage in the field of cancer biomarker detection. Adsorption and immobilisation of biomolecules are led by their large surface area and high conductivity, which enables highly sensitive electrochemical and photoluminescent assays [94]. The layered structure of WS2 as well as its modifiable surface allow functionalization with the antibodies, peptides and other biomolecules which enhances its selectivity to specific cancer markers like carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), prostate-specific antigen (PSA) and alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) [95, 96]. These markers are linked to various cancers including colorectal, prostate and liver cancers respectively.

A major benefit of WS2 based sensors lies in their flexibility and potential for integration into portable diagnostic devices. Combining WS2 with gold nanoparticles has been shown in order to increase electrochemical responses which enables the detection of cancer biomarkers at ultralow concentrations. WS2’s Platform compatibility with microfluidis aids in creating miniaturised sensing devices which offer rapid and point-of-care cancer diagnostic. Due to WS2’s high surface reactivity and tunable electronic properties can be further optimised through doping and heterostructure formation. By introducing elements like nitrogen or sulphur, improved electron transfer rates have been achieved by researchers which boosts the material’s sensitivity to minute concentrations of cancer biomarkers. Heterostructures like WS2 combined with graphene, exhibit synergistic effects that further amplify signal detection, creating highly sensitive biosensors which are capable of real-time monitoring. In cancer biomarker detection, WS2 based sensors often use electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) and photoluminescence techniques [97]. EIS measures changes in electrical resistance when a biomarker interacts with the WS2 surface, by providing rapid and and specific biomarker identification. WS2’s photoluminescent properties are important because WS2 nanosheet exhibits fluorescence that can be modulated upon biomarker binding, offering a visual and quantitative means of detection. This dual-mode approach not only enhances sensitivity but also minimizes false positives, which is a mandatory requirement in clinical diagnostics. Moreover, WS2’s biocompatibility and low cytotoxicity make it suitable for in vivo applications, opening possibilities for its integration into implantable sensors [98]. For instance, researchers are exploring WS2 based nanocomposites in wearable devices that could continuously monitor cancer biomarker levels through sweat or interstitial fluids. Such types of applications could enable early cancer detection for at-risk populations through non-invasive, real-time monitoring. Furthermore, WS2 can be functionalized with aptamers-synthetic, single-stranded DNA or RNA molecules designed to bind specific biomarkers. Aptamers functionalized WS2 has shown enhanced selectivity towards cancer-related markers, which makes it highly effective in differentiating in cancerous and healthy cells. This ability to target specific biomarkers with high precision holds promise in personalised cancer diagnostics and therapy monitoring.

Integrating WS2 sensors with AI algorithms for data analysis could lead to even more powerful diagnostic platforms. AI models can analyse huge datasets generated from WS2sensors, identifying trends, and patterns with disease progression. The development of smart sensing systems will revolutionize cancer diagnostics drastically for mankind.

DNA and RNA detection

Detection of DNA and RNA is fundamental in diagnostics, identifying pathogens and genetic research [99]. A great help in identifying genetic mutations and infectious agents is provided by effective nucleic acid detection, which is very essential for personalised medicines and public health. Nucleic acid detection methods may involve complex protocols, high cost as well as extensive time [100]. So, there’s a great demand for label free, sensitive accessible detection technologies. WS2 has emerged as one of the powerful candidates in biosensing due to its unique structure and properties. WS2 has some unique attributes that are advantageous for DNA/RNA detection [101]. Some of those attributes are its large surface area, its biocompatibility, its optoelectronic properties, its sensitivity and stability. There are several DNA & RNA detection with WS2 based sensors they are mentioned as follows.

Fluorescence Quenching and Recovery: Fluorescence quenching is one of the common approach in WS2 based sensors [102]. When fluorophore labelled DNA/RNA strands are attached to WS2, the signal is quenched. Fluorescence either reappears or changes which makes detection possible upon hybridization with the target. This approach is popular for applications that require fluorescent probes and works well in complex biological samples.

Electrochemical sensing: WS2 can also serve as an electrode material, enabling the detection of DNA/RNA hybridization events through measurable shifts in electrochemical signals. This label free method is effective for quick, on site testing due to its low power requirements and efficiency [103].

Field effect transistor (FET) sensing: WS2’s compatibility with FET based sensors enables the real-time nucleic acid detection. When DNA and RNA binds to WS2 in an FET setup, the current and conductance of the device changes, providing a sensitive immediate readout of the binding events [104].

WS2 biosensors has been showcased in several studies in specific DNA and RNA detection scenarios. For instance, they have been used to detect viral RNA, which has significant implications in infectious disease management, including emerging pathogens like SARS-CoV-2 [105]. These sensors have shown high sensitivity with low limits of detection (LOD) making them essential for early diagnosis [104].The potential of WS2 in order to advance DNA and RNA detection is substantial, combining sensitivity, stability and versatility. Continued research on WS2’s application in biosensing could lead to its adoption in next-gen diagnostic tools, meeting the demand for efficient, accurate and accessible biosensors.

Protein and enzyme sensing

Protein and Enzyme Detection is fundamental to wide range of fields, which includes clinical diagnosis, biomedical research and environmental monitoring [106–109]. Enzymes are critical in catalysing biochemical reactions and numerous roles are played by proteins, from structural to regulatory [110]. Changes in presence or levels of specific proteins and enzymes can signal various health conditions, infections as well as metabolic disorders. There are effective traditional methods but they can be often limited by cost, complexity or time constraints, which leads to exploration of novel efficient materials for protein and enzyme biosensing.

There are numerous advantages of WS2 in protein and enzyme detection.

High surface area and functionalization potential: WS2 has a large surface-to-volume ratio, which allows extensive functionalization with specific molecules. Strong binding with target proteins or enzymes are enabled which enhances detection sensitivity [88].

Excellent conductivity and excellent mobility: Electronic properties of WS2 support the development of biosensors with quick response times [82, 111]. Changes in the concentration of proteins or enzymes can lead to detectable shifts in voltage or current [112].

Optical and electrochemical versatility: Strong fluorescence quenching as well as electrochemical properties exhibited by WS2 make it a dual-functional material that can support multiple detection methods in order to sense protein and enzymes [113]. There are several mechanisms to detect protein and enzymes using WS2 which are mentioned below.

Fluorescence quenching: WS2 can be employed in fluorescence-based assays by quenching the fluorescence of proteins labelled with fluorophores. Protein or enzyme interacts with the WS2 surface in order to change fluorescence signal can indicate its presence or concentration. This method specifically detects enzymatic activities or protein binding events in complex samples [114].

Electrochemical detection: WS2 modified electrodes in electrochemical biosensors are effective for protein and enzyme sensing. When enzymes or proteins interact with WS2, they cause measurable electrochemical responses like current or potential changes. This label-free approach allows rapid, on-site detection and is advantageous for clinical and environmental applications where time and portability are essential [115].

Field-effect transistor (FET) mechanism: FET sensors which are based on WS2 can detect proteins and enzymes in real time. Binding events on the WS2 surface induce changes in the current or conductivity within the FET in order to provide a highly sensitive detection method. This real-time capability is very essential for applications that require dynamic monitoring of biomolecular interactions.

Studies have demonstrated WS2-based biosensors in various protein and enzyme detection contexts like disease biomarker detection in which certain proteins act as biomarkers for diseases like cancer, cardiovascular conditions or diabetes [116]. In enzyme activity monitoring the enzymes are often monitored in pharmaceutical and biochemical industries in order to ensure quality control. Even in environmental monitoring, WS2 sensors have been tested for detecting enzymes or proteins in environmental samples such as pollutant tracking, underscoring their versatility beyond clinical diagnostics. WS2 based biosensors have shown remarkable potential for improving protein and enzyme detection by combining sensitivity, biocompatibility and versatility in various situations. The continued development of WS2 in this area can open many pathways for accessible, reliable and sensitive biosensors whose applications can be in medical diagnostics, environmental monitoring etc.

Glucose and cholesterol monitoring

In managing diabetes, cardiovascular diseases and other metabolic disorders it is crucial to keep track of the cholesterol and glucose levels [117]. Regular and accurate tracking of these biomolecules leads to early diagnosis and effective disease management. Conventional detection techniques often rely on bulky lab equipment or it involve complex biochemical protocols which limit accessibility. As WS2 has numerous advantageous properties it has been explored as a cheaper and highly efficient alternative in biosensing for glucose and cholesterol monitoring [118]. WS2 is one of the most suitable elements for glucose and cholesterol sensing. Due to the large surface area of WS2 which is advantageous for attaching enzymes or other sensing molecules, it boosts detection efficiency and sensitivity [87]. WS2’s conductive and optoelectronic features facilitate electrochemical reactions, which is essential for detecting small molecules like glucose and cholesterol [119]. Also, WS2 is stable under physiological conditions which makes it suitable for biosensing applications that require contact with biological fluids [120]. There are several mechanisms to detect glucose and cholesterol using WS2.

Enzymatic electrochemical detection: It is one of the popular approaches for WS2 based glucose and cholesterol sensors which use enzymes like glucose oxidase for glucose detection and cholesterol oxidase for cholesterol detection. While interacting with their specific substrates these enzymes produce hydrogen peroxide or other by-products in order to generate an electrochemical response generated by WS2 electrodes. Due to this approach, WS2’s electrochemical properties are leveraged which enables rapid and sensitive detection [121].

Non-enzymatic electrochemical sensing: WS2 can also function in non-enzymatic glucose or cholesterol sensing. In these systems, WS2 facilitates the oxidation of glucose or cholesterol sensing which eliminates the need for enzyme immobilization. Due to this approach, the sensor’s stability is improved, as enzyme-free devices tend to be less sensitive to environmental conditions like temperature or pH [122].

Field effect transistor (FET) sensors: WS2 based FET sensors detect glucose or cholesterol by monitoring changes in conductivity caused by biomolecular binding events. This approach enables real-time detection with high sensitivity which is valuable for applications that demand quick response time, just like continuous glucose monitoring.

There are specific applications in glucose and cholesterol monitoring. Several studies have found out that WS2based sensors can detect glucose at concentrations as low as a few micromoles, which is in line with physiological levels necessary for clinical use like Diabetes management, and cholesterol detection for cardiovascular health [123].

Diabetes management: WS2 sensors have been applied to glucose detection in blood samples, showing high sensitivity and rapid response times. It is significantly useful for diabetes patients who require frequent monitoring.

Cholesterol detection for cardiovascular health: WS2 based cholesterol sensors are able to detect elevated cholesterol levels which provide data that is critical to assessing cardiovascular risk [124]. These sensors offer an added advantage as they require only a small blood sample, improving user comfort and compliance.

WS₂based sensors offer mesmerizing prospects for non-invasive, sensitive rapid detection of glucose and cholesterol, which meets the rising demand for user-friendly and accessible health solutions. As WS2 biosensors continue to evolve, they may act as a vital player in the next generation of healthcare technologies, which contributes to better patient outcomes and more efficient disease management.

Pathogen detection

One of the essential parts of preventing and controlling infectious diseases is pathogen detection, which is one of the major public health concerns [125]. Rapid, early, and accurate detection of pathogens like bacteria, viruses, and fungi is critical in clinical diagnostics, food safety, and environmental monitoring [126]. Conventional detection methods like PCR and ELISA are highly specific but can be time-consuming and often require complex lab equipment [127]. This has developed interest in manufacturing biosensors, particularly those based on 2D materials like WS2 to enable faster, more accessible pathogen detection. There are several advantages of WS2 for pathogen detection which are as follows:

High Surface Reactivity for Target Binding: Due to WS2’s high surface area, it provides ample space for functionalization, which allows it to capture target pathogens or pathogen-specific biomolecules with high efficiency. Fluorescent and Electrochemical Sensitivity: WS2 demonstrates fluorescent and electrochemical properties, which allows it to act as a dual-mode biosensor. Its sensitivity enhances the detection of low pathogen concentrations [128]. Biocompatibility and Stability: WS2 is stable in aqueous and physiological conditions which enables it to maintain functionality in biological samples which is a crucial feature in order to detect pathogens in real-world samples [98].

There are several mechanisms for detecting pathogens using WS2:

Fluorescence quenching for label-free detection: WS2 is widely in fluorescence-based biosensing as it has the ability to quench fluorescence [129]. When it is functionalized with probes that bind to specific pathogens or their genetic material, WS2 is able to detect pathogens by measuring changes in fluorescence. Due to this method, it is possible for label-free, real-time detection which reduces the need for complex sample preparation.

Electrochemical sensing with functionalized WS2 electrodes: By immobilizing antibodies, aptamers, or nucleic acids on WS2 modified electrodes, electrochemical WS2 sensors are based. When these come into contact with pathogens they generate electrochemical signals that correlate with pathogen concentration for quantitative analysis [130].

Field effect transistors (FET) devices for rapid detection: Promising results have been shown by WS2 based FET devices in pathogen detection, leveraging changes in conductivity that occur when a pathogen binds to the WS2 surface. It is beneficial for real-time, high-sensitivity applications as it permits continuous monitoring without the need for extensive sample handling [104].

There are several applications of WS2 in pathogen detection they are used in exploring and detecting various pathogens including viruses, bacteria, and fungi with high sensitivity and selectivity. Some of the applications are mentioned as follows: Viral Detection: WS2 based sensors have shown a great capability in detecting viral genetic material at low concentrations which makes it suitable for applications in point-of-care dengue diagnostics [131]. Bacterial Contamination in Food and Water: WS2 based biosensors have been applied in order to detect bacteria like E. Coli and Salmonella in food and water samples which is crucial for food safety monitoring and environmental protection [132]. Fungal Pathogen Detection: WS2 based sensors have also demonstrated potential in detecting fungal pathogens which are important in controlling agricultural diseases as well as crop health [133].

Recent innovations in hospital-on-chip and nose-on-chip technologies have facilitated real-time, non-invasive disease diagnoses [134]. WS2-based nanocomposites, including polypyrrole-Ag/AgCl electrodes, exhibit potential in monitoring exhaled breath acetone for diabetes diagnosis, whilst WS2-polyaniline-WO₃ sensors provide breath-based hydrogen detection for irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) [135]. In comparison to MoS2, graphene, and black phosphorus, WS2 exhibits superior photoluminescence, biocompatibility, and adjustable optoelectronic characteristics, rendering it optimal for breathomics and VOC-based diagnostics. Additional investigation into hybrid nanostructures and AI-enhanced biosensors can enhance WS2’s function in advanced portable and clinical diagnostic systems [136].

WS2’s unique properties have enabled the development of a great sensitive and versatile pathogen identification system, showing promise for onsite diagnostic applications. Continued advancements in this field may provide a way WS2 based biosensors to become a key tool in rapidly accessible infectious disease diagnostics and other pathogen detection applications. Abbreviations.

Future prospects

The growing applications of WS2 in biosensing suggest that it has the potential to transform diagnostics, environmental monitoring, and healthcare technologies. Because of the high surface area of WS2as well as tunable electronic properties and biocompatibility, WS2 has been highly effective in applications ranging from pathogen detection to glucose monitoring. However, the research could focus on integrating WS2 with other nanomaterials to enhance sensitivity, selectivity, and stability. Such hybrid materials may enable more efficient biosensors capable of detecting multiple biomarkers simultaneously which is essential in complex diagnostic scenarios. The amalgamation of WS2 with gold nanoparticles has resulted in the formation of nanohybrids that enhance Raman signals, facilitating the detection of biomolecules at extremely low concentrations [137]. This improvement is ascribed to the synergistic plasmonic and chemical characteristics of the nanohybrids. Novel methodologies have shown that WS2 can be utilized on paper substrates to create thermoresistive sensors [138]. These devices demonstrate significant sensitivity to temperature fluctuations and have been successfully employed in monitoring breathing patterns, highlighting their potential in wearable health monitoring systems. WS2 has been utilized in the advancement of electrochemical sensors designed to identify certain DNA sequences and proteins. The material’s distinctive electronic characteristics enable swift and precise measurements, rendering these sensors indispensable in medical diagnostics. The integration of WS2 with flexible substrates has produced wearable sensors that track physiological data, including glucose levels and heart rate. These gadgets provide real-time data collection, enhancing individualized healthcare solutions.

Furthermore, the development of WS2-based wearable and implantable biosensors is a promising direction, particularly for real-time, continuous health monitoring. This aligns with the trends in personalized healthcare, wherein patients could receive proactive care based on continuous monitoring of biomarkers, improving early detection and disease prevention. There is another area of potential growth in WS2’s applications is in the Internet of Things (IoT)-enabled biosensing systems, facilitating remote, on-demand diagnostics for both clinical and environmental settings.

Despite its promise, challenges such as large-scale, reproducible synthesis, long-term stability, and performance in complex biological environments remain. Addressing these issues could involve advanced fabrication methods and functionalization techniques. Additionally, integrating WS2 biosensors with AI-driven data analysis tools could enhance the precision of diagnostics and enable predictive modeling for health monitoring. With these advancements, WS2 based biosensors are well positioned to lead future innovations in biosensing, providing accessible, accurate, and versatile solutions across various fields. The exploration of WS2 as a cornerstone for advanced biosensing applications has emerged as a transformative advantage in diagnostics, environmental monitoring, and health care technologies. The multifaceted properties including high surface area, exceptional electrical conductivity, and unique optoelectronic features make it a prime candidate for next-generation biosensing platforms. Building upon the analysis of its current applications, several emerging trends and innovations are to enhance the utility of WS2 in this field. Future developments in WS2-based biosensing necessitate enhancements in fabrication, hybrid materials, and artificial intelligence integration. Improvements in fabrication, including optimal CVD growth, refinements in liquid-phase exfoliation, and advancements in electrochemical exfoliation, can enhance scalability and consistency.

A significant direction for the future environment involves the integration of WS2 with other 2D materials or nanostructures to create hybrid composites. These hybrid materials can leverage the synergistic properties of different components leading to enhanced sensitivity, selectivity, and robustness in biosensors. The hybrid approach also opens opportunities to design multifunctional sensors capable of detecting multiple analytes simultaneously, which is critical for comprehensive health monitoring. With the rise of personalized healthcare, wearable and implantable biosensors that use WS2 could revolutionize how individuals monitor their health in real-time. WS2’s mechanical flexibility and biocompatibility make it suitable for integration into wearable electronics that conform to the human body. Innovations in this domain may lead to non-invasive devices capable of monitoring glucose levels, vital signs, or even specific biomarkers related to chronic diseases. Implantable biosensors that leverage biocompatibility of WS2 could be developed for continuous monitoring of internal biological changes, facilitating early diagnosis and targeted treatment.

The convergence of WS2 based biosensing technologies with the Internet of Things could transform healthcare delivery and environmental monitoring. IoT-enabled biosensors equipped with wireless communication capabilities would allow for seamless data transmission and real-time health analytics. This integration would support remote patient monitoring reducing the need for frequent hospital visits and enabling healthcare professionals to track patient health data continuously. WS2–based sensors, with their high sensitivity, could form the backbone of these systems by providing reliable and precise data for digital health applications.

AI can significantly enhance the diagnostic capabilities of WS2 based biosensors. By applying machine learning algorithms to analyze the complex data generated by these sensors, AI can help identify patterns and correlations that may not be discernible through conventional methods. This could lead to faster diagnosis, prediction of disease outbreaks, and development of personalized treatment plans. Integrating WS2biosensors with AI-driven platforms could facilitate adaptive learning systems wherein the sensor parameters are automatically optimized based on the collected data to improve accuracy over time. The use of WS2 in biosensing extends beyond healthcare into environmental monitoring. Future applications may include sensors capable of detecting pollutants, pathogens, and toxic chemicals in water and air. Given WS2 ‘s high reactivity and flexible electronic properties, it’s particularly well suited for detecting trace amounts of hazardous substances. The development of portable cost-effective WS2 based sensors could support efforts in environmental protection and sustainability enabling real-time assessment of pollution levels and promoting cleaner practices across various industries. Hybrid materials, such as WS2-graphene composites, metal nanoparticle functionalization (e.g., Au, Ag), and biofunctionalization using aptamers, can improve sensitivity and selectivity. The incorporation of AI in biosensing facilitates real-time signal processing, predictive diagnosis, and IoT-enabled remote monitoring, hence enhancing the efficiency of biosensors. These developments will facilitate the development of highly sensitive, selective, and scalable WS2 biosensors, transforming personalized healthcare, environmental monitoring, and disease detection with enhanced accuracy and dependability.

While the potential of WS2 in biosensing is vast several challenges must be addressed to fully harness its capabilities. One primary concern is the scalability of producing high-quality WS2 nanosheets with consistent properties. Advancements in fabrication techniques such as chemical vapor deposition (CVD) and liquid phase exfoliation are necessary to ensure uniformity and reproducibility. Surface modification strategies must be defined to enhance the stability and functionalization of WS2for specific biosensing applications. As WS2 based biosensors move towards commercialization, it is imperative to establish regulatory frameworks and standards to ensure their safety and efficacy. Collaboration between researchers, industry stakeholders, and regulatory bodies can facilitate the development of guidelines that define the performance criteria for these sensors. This step is essential not only for gaining public trust but also for streamlining the process for bringing new WS2 based technologies to market.

Looking ahead, WS2 is poised to play a central role in advancing biosensing technologies across multiple disciplines. Continued research focussing on optimizing its functional properties, exploring novel hybrid configurations, and developing user-friendly devices will dive into widespread adoption. The integration of WS2 based sensors with digital health tools, Al platforms, and sustainable practices promises to create a future where rapid accurate, and accessible diagnostics are the norm.

In conclusion, the journey of WS2 from an emerging 2D material to a mainstay in biosensing represents a promising frontier in scientific research and innovation. By addressing existing challenges, embracing technological convergence, and adhering to standardized practices, WS2 based biosensing technologies can unlock new levels of precision and efficiency in medical and environmental diagnostics.

Author contributions

Conceptualization, C.-C.W., H.-C.W.; methodology, C.-C.W., H.-C.W.; preparation of samples, H.-C.W.; data curation, A.M., K.S.J., R.K.; writing—original draft preparation, A.M., K.S.J., R.K., C.-C.W., H.-C.W.; writing—review and editing, A.M., H.-C.W.; visualization, R.K., H.-C.W.; supervision, C.-C.W., H.-C.W.; project administration, C.-C.W., A.M.,R.K., K.S.J.;. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Science and Technology Council, the Republic of China, under grants NSTC 113-2221-E-194-011-MY3, 112-2634-F-194-001, and Emerging Technology Application Project of Southern Taiwan Science Park under the grants 113 CM-1-02. This study was financially or partially supported by the Dalin Tzu Chi Hospital, Buddhist Tzu Chi Medical Foundation-National Chung Cheng University Joint Research Program and Kaohsiung Armed Forces General Hospital Research Program KAFGH_D_114064 in Taiwan.

Data availability

The data presented in this study are available in this article upon considerable request to the corresponding author (H.-C.W.).

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent to publish

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Gupta A, Sakthivel T, Seal S. Recent development in 2D materials beyond. Prog Mater Sci. 2015;73:44–126. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pham PV, et al. 2D heterostructures for ubiquitous electronics and optoelectronics: principles, opportunities, and challenges. Chem Rev. 2022;122(6):6514–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ares P, Novoselov KS. Recent advances in graphene and other 2D materials. Nano Mater Sci. 2022;4(1):3–9. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meng R, et al. Hole-doping induced ferromagnetism in 2D materials. Comput Mater. 2022;8(1):230. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shanmugam V, et al. A review of the synthesis, properties, and applications of2D materials. Particle. 2022;39(6):2200031. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang H. Introduction: 2D materials chemistry. Chem Rev. 2018;118(13):6089–90. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Choudhary N, et al. Two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenide hybrid materials. Nano Today. 2018;19:16–40. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chhowalla M, Liu Z, Zhang H. Two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenide(TMD) nanosheets. Chem Soc Rev. 2015;44:2584–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang HH, Fan X, Singh DJ, Zheng WT. Recent progress of TMD nanomaterials: phase transitions and applications. Nanoscale. 2020;12(3):1247–68. 10.1039/C9NR08313H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lan C, Li C, Ho JC, Liu Y. 2D WS2: from vapor phase synthesis to device applications. Adv Electron Mater. 2021. 10.1002/aelm.202000688. [Google Scholar]