Abstract

Introduction

Transient viremia can occur in people with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), often referred to as people with HIV (PWH), and is sometimes related to poor adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART). Guidelines recommend achieving virologic resuppression with existing ART regimens while addressing the reasons for the lack of virologic control. However, there are limited clinical trial data on the effectiveness of the strategy of continuing the same ART regimen in treatment-experienced PWH following a period of viremia. This was a post hoc pooled analysis of eight clinical studies in PWH receiving bictegravir/emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide (B/F/TAF).

Methods

Viremic events occurring in participants receiving B/F/TAF were defined as ≥ 1 viral load (VL) measurement of ≥ 50 copies/mL after virologic suppression (VL < 50 copies/mL). Outcomes after viremic events were categorized as: virologic resuppression (≥ 1 subsequent VL < 50 copies/mL); continued viremia (all subsequent VLs ≥ 50 copies/mL); or not evaluable (no subsequent VL assessment). Adherence was calculated by pill count from returned pill bottles.

Results

The analysis included 2801 participants. A total of 411 viremic events were experienced by 290 participants, 50% of whom were treatment naïve at B/F/TAF initiation, and the other 50% were virologically suppressed. A total of 91 participants experienced ≥ 1 viremic event of ≥ 1000 copies/mL. The proportion of viremic events followed by resuppression on B/F/TAF was 90.3%, rising to 96.6% when nonevaluable data were excluded. The median (quartile [Q]1, Q3) time from a viremic event to documented resuppression was 22 (18, 36) days. Among 13 participants with continued viremia, 11 (84.6%) prematurely discontinued B/F/TAF. No treatment-emergent resistance was observed in participants with continued viremia. A significantly higher proportion of participants with a viremic event had < 85% adherence compared with those without (10.0% and 4.2%, respectively; p = 0.0003).

Conclusions

Most participants receiving B/F/TAF experienced no viremic events. The vast majority of viremic events resolved with B/F/TAF continuation, without the need for treatment change.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40121-025-01153-y.

Keywords: Adherence, Antiretroviral therapy, Bictegravir/emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide, Genotype analysis, Human immunodeficiency virus, Virologic suppression

Key Summary Points

| Why carry out this study? |

| In people with HIV (PWH) experiencing viremia, guidelines recommend the continuation of antiretroviral therapy (ART) and support to increase adherence to the existing regimen. |

| However, there is a lack of clinical trial data on the effectiveness of continuing the same ART regimen in PWH experiencing viremia. |

| What was learned from the study? |

| This post hoc analysis using pooled data from eight clinical trials of bictegravir/emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide (B/F/TAF) found that most participants on B/F/TAF did not experience any viremic events throughout the studies; approximately one-third of viremic events exceeded an HIV-1 RNA viral load of 1000 copies/mL. |

| Participants with lower adherence (< 85%) experienced more frequent viremic events than those with higher adherence. |

| Over 90% of viremic events resolved on B/F/TAF, without the need for treatment change. |

Introduction

Treatment guidelines state that the primary goal of antiretroviral therapy (ART) in people with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), often referred to as people with HIV (PWH), is the prevention of HIV-associated morbidity and mortality, achieved through maximal and durable suppression of plasma viremia [1]. However, an estimated one in three individuals in the USA receiving ART for HIV do not maintain continuous virologic suppression over a 12-month period [2]. Lack of virologic suppression is associated with an increased risk of HIV transmission, worsening immune function, poor clinical outcomes, and potential for the development of drug resistance [1, 3].

Although there is no international consensus on the terms used to describe the nature and duration of viremia, various terms are commonly used to classify different viremic events [1]. These include low-level viremia (detectable HIV-1 RNA levels but < 200 copies/mL), virologic blip (an isolated detectable viremic event preceded and followed by virologic suppression), virologic rebound (confirmed viremic event after achieving virologic suppression), and incomplete virologic response (an individual who has not yet achieved virologic suppression with their ART). Virologic failure is the inability to achieve or maintain virologic suppression, with the guideline-defined threshold of either HIV-1 RNA > 50 copies/mL [4] or ≥ 200 copies/mL [1].

Viremic events occur for a range of reasons [5]. Maintaining adequate adherence to ART is key to achieving long-term virologic suppression [1, 3]. In cases of loss of virologic control without treatment resistance, guidelines state that ART should be reinitiated and that PWH should be supported to improve adherence to their existing regimen [1, 4, 6]. However, data on the effectiveness of ART following viremia are limited.

Bictegravir/emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide (B/F/TAF) is a three-drug regimen containing bictegravir, emtricitabine, and tenofovir alafenamide coformulated as a single tablet [1]. B/F/TAF was approved in the USA and European Union (EU) in 2018 [7, 8] and has subsequently been licensed in many countries [9]. B/F/TAF has demonstrated high levels of efficacy and acceptable safety in clinical trials in both antiretroviral treatment-naïve and treatment-experienced, virologically suppressed PWH [10–18]. On the basis of these data, B/F/TAF has become a recommended first-line ART regimen in international guidelines [1, 4, 6].

In a recent observational study in Italy, of 12 individuals who experienced virologic rebound after switching to B/F/TAF, 10 (83.3%) achieved virologic resuppression without a treatment change [19]. However, further evidence in a larger and more varied population is needed to understand the optimal treatment strategy in people who experience viremic events while on B/F/TAF.

In this study, we pooled data from eight clinical trials to examine viremic events and subsequent outcomes in both treatment-naïve and treatment-experienced, virologically suppressed PWH receiving B/F/TAF.

Methods

Studies Included in this Analysis

This post hoc pooled analysis evaluated data from six multicenter phase 3/3b randomized controlled trials (Study 1489: GS‑US‑380‑1489 [NCT02607930] [12], Study 1490: GS‑US‑380‑1490 [NCT02607956] [17], Study 1844: GS‑US‑380‑1844 [NCT02603120] [16], Study 1878: GS‑US‑380‑1878 [NCT02603107] [11], Study 4030: GS‑US‑380‑4030 [NCT03110380] [18], and Study 4580: GS‑US‑380‑4580 [NCT03631732]) [13], one phase 3 open-label, single-arm study (Study 4449: GS‑US-380‑4449 [NCT03405935]) [15], and one phase 2/3 pediatric study (Study 1474: GS-US-380–1474 [NCT02881320]) [20] (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Study design. n-values show the number of participants with ≥ 1 postbaseline HIV-1 RNA measurement and ≥ 1 virologic suppression on B/F/TAF during each study. aAge ≥ 65 years for Study 4449 and 2 to < 18 years for Study 1474; identifying as Black, African American, or mixed race (including Black) for Study 4580. bNRTI resistance was permitted in Study 4030; FTC resistance was permitted in Study 4580; resistance to the following drugs was not permitted in certain studies: INSTIs (Studies 4030 and 4580), ABC and 3TC (Study 1489), DTG (Study 1844), and BIC (Study 4449). c ≥ 30 mL/min for Studies 1490, 4030, and 4449; ≥ 50 mL/min for Studies 1489, 1844, 1878, and 4580; and ≥ 90 mL/min/1.73 m2 by the Schwartz formula for Study 1474. d ≥ 6 months for Studies 1878, 4030 (if there was documented or suspected NRTI resistance prior to screening), 4580, and 1474. eStudies 4449 and 4580 did not include a scheduled week 8 visit. 3TC lamivudine, ABC abacavir, ARV antiretroviral, ATV atazanavir, B/BIC bictegravir, C cobicistat, DTG dolutegravir, E elvitegravir, eGFRCG estimated glomerular filtration rate by Cockcroft–Gault equation, F/FTC emtricitabine, INSTI integrase strand-transfer inhibitor, NRTI nucleoside/nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitor, TAF tenofovir alafenamide, TDF tenofovir disoproxil fumarate

Studies 1489 and 1490 enrolled treatment-naïve PWH with plasma HIV-1 RNA ≥ 500 copies/mL. The remaining six studies enrolled treatment-experienced PWH who had both been receiving a stable ART regimen and were virologically suppressed (plasma HIV-1 RNA < 50 copies/mL) for ≥ 3–6 months prior to screening. Resistance to some or all of the components of B/F/TAF and prior virologic rebound were permitted in some of these studies (the resistance mutations that were permitted or excluded at entry to the eight studies have been detailed previously [11–13, 15–18, 20]). The current analysis included all participants with ≥ 1 postbaseline HIV-1 RNA measurement and ≥ 1 visit with virologic suppression while on B/F/TAF.

For Studies 1489, 1490, 4030, and 4580, the pooled analysis included data from the randomized and extension phases. For Studies 1844, 1878, and 4449, data up to week 48 were included. For Study 1474, data were included up to the last participant reaching week 96 in cohorts 1 and 2 (aged 6–18 years) and the last participant reaching week 24 in cohort 3 (aged 2–5 years) [21]. These study periods applied for all outcomes evaluated in this pooled analysis.

Each study in this analysis was conducted in accordance with the protocol and ethical principles derived from international guidelines, including the Declaration of Helsinki of 1964 and its later amendments, Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences International Ethical Guidelines, applicable International Council for Harmonization (ICH) guidelines for Good Clinical Practice (GCP), and all applicable laws, rules, and regulations. The protocols for each study were approved by an institutional review board or ethics committee. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Outcomes

Definition of the Viremic Population for this Post Hoc Analysis

Viremic events occurring in participants receiving B/F/TAF were defined as ≥ 1 HIV-1 RNA measurement of ≥ 50 copies/mL after virologic suppression (< 50 copies/mL) on B/F/TAF. For participants switched from comparator ART regimens in the randomized phase of the studies to B/F/TAF in the extension phase, viremic events on comparator ART were defined as baseline HIV-1 RNA ≥ 50 copies/mL on or prior to the first dose of B/F/TAF. Sensitivity analyses were also performed for viremic events on B/F/TAF, with the viremic event threshold set to either ≥ 200 copies/mL, per the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) guidelines of viremic failure [1], or ≥ 1000 copies/mL, per the World Health Organization definition of an unsuppressed viral load [22].

Efficacy Outcomes

Viremic events were classified on the basis of viral load assessments recorded at any scheduled or unscheduled clinic visits. These were categorized on the basis of virologic outcomes following the event: virologic resuppression (≥ 1 HIV-1 RNA measurement < 50 copies/mL after the viremic event); continued viremia (all subsequent HIV-1 RNA measurements after the viremic event ≥ 50 copies/mL); or not evaluable (no subsequent HIV-1 RNA assessment after the viremic event).

Viremic event outcomes at the participant level were categorized on the basis of the last viremic event.

At the event level, the duration of viremic events was analyzed as follows: time from suppression to viremic event (time from first HIV-1 RNA < 50 copies/mL before a viremic event to first HIV-1 RNA ≥ 50 copies/mL in a viremic event), time from viremic event to resuppression (time from first HIV-1 RNA ≥ 50 copies/mL in a viremic event to first HIV-1 RNA < 50 copies/mL after the viremic event; for viremia in participants with HIV-1 RNA ≥ 50 copies/mL at last study visit on comparator ART, time from last visit on comparator ART [prior to initiation of B/F/TAF] to resuppression on B/F/TAF), and duration of continued viremia (time from first HIV-1 RNA ≥ 50 copies/mL in the continued viremic event to last HIV-1 RNA ≥ 50 copies/mL on B/F/TAF, with no intervening measurements of < 50 copies/mL). The analysis of the duration of viremic events was limited by only having data collected at clinic visits.

Baseline Resistance Testing

When available, historical genotype reports using commercial or local assays were collected at enrollment, and resistance-associated substitutions in protease (PR), reverse transcriptase (RT), and integrase (IN) were recorded. In the studies of treatment-naïve PWH, PR/RT genotyping was prospectively determined, and IN genotyping was retrospectively assessed using screening plasma samples. In the studies of PWH who were virologically suppressed, retrospective genotypic analyses of PR/RT/IN from proviral HIV-1 DNA were performed on baseline whole blood samples. Data from historical and screening/baseline genotypes were aggregated, and composite baseline sequences were derived from cumulative data for participants with multiple pretreatment genotypes and assessed for the presence of preexisting resistance-associated substitutions.

Postbaseline Resistance Testing

Postbaseline genotypic and phenotypic resistance analyses were carried out for participants who experienced virologic failure with HIV-1 RNA ≥ 200 copies/mL. Virologic failure was defined as virologic rebound or having HIV-1 RNA ≥ 50 copies/mL at key study endpoints or the last on-treatment study visit (including study drug discontinuation).

Virologic rebound was defined as: at any visit after day 1, a rebound in HIV-1 RNA to ≥ 50 copies/mL, which was confirmed at the following visit, or, at any visit, a > 1 log10 increase in HIV-1 RNA from the nadir, which was confirmed at the following visit (studies in treatment-naïve PWH only).

Baseline and postbaseline assessments of HIV-1 PR, RT, and IN were performed using commercially available assays.

Adherence Measurements

Study drug adherence over the study duration or up to the time of the interim analysis was calculated for participants who returned ≥ 1 pill bottle as the number of pills taken divided by the number of pills prescribed. The number of pills taken was imputed or calculated as the number of pills dispensed minus the number of pills returned.

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented for the B/F/TAF analysis set, which included all participants who received ≥ 1 dose of B/F/TAF, had ≥ 1 postdose HIV-1 RNA value, and achieved virologic suppression (HIV-1 RNA < 50 copies/mL) at ≥ 1 study visit while on B/F/TAF.

The proportion of participants within each category of outcome following their last viremic event and the proportion of each category of viremic event outcome (at the event level) were analyzed using the following two methods for imputing data for participants who had viremia at the last assessment (i.e., not evaluable):

“Not evaluable = continued viremia,” which treated participants with nonevaluable data as having continued viremia. The denominator for percentages is the number of participants with any viremia (at the participant level) or number of any viremic events (at the event level).

“Not evaluable = excluded,” which excluded participants with nonevaluable data from both the numerator and denominator in the computation of the percentages.

Efficacy outcomes of achieving HIV-1 RNA < 50 copies/mL on B/F/TAF were analyzed using the “missing = excluded” approach (excluding missing data from both the numerator and denominator in the computation of percentages). Two analyses were conducted: (1) baseline reset at the date of first viremia and (2) baseline reset at the date of last viremia.

On the basis of previous studies [23, 24], low adherence was defined as < 85%.

Baseline characteristics were compared between participants with and without a viremic event using the Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel test for categorical data and the two-sided van Elteren test for continuous data stratified by participant population type (treatment-naïve versus virologically suppressed). Statistical comparisons of viremic event status by participant population type (treatment-naïve: including participants randomized to B/F/TAF in Studies 1489 and 1490; virologically suppressed: including participants switched to B/F/TAF in the extension phase of Studies 1489 and 1490, and those treated with B/F/TAF in studies of PWH who were virologically suppressed) were conducted using the Fisher exact test.

Statistical analysis of adherence was performed for participants with versus those without viremic event using the Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel test stratified by participant population type.

Unless otherwise specified, all statistical tests were two-sided and performed at the 5% significance level. Nominal P-values (without multiplicity adjustment) were provided. The Clopper–Pearson Exact method was used to obtain 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Statistical analyses were conducted in SAS version 9.4.

Results

Participant Disposition and Baseline Characteristics

Of the 2801 participants included in the analysis, 290 experienced at least one viremic event on B/F/TAF. Participant inclusion in the analysis is shown in Fig. 2. A total of 145 participants had been treatment naïve at study entry, and 145 were virologically suppressed. In total, 14 participants were randomized to receive a comparator ART, had viremia at their last visit on study drug, and subsequently switched to B/F/TAF in the open-label extension phase of the studies. A total of 6 of these 14 participants also had viremic events during B/F/TAF treatment and were included in the group of 145 virologically suppressed participants who experienced ≥ 1 viremic event on B/F/TAF.

Fig. 2.

Participant inclusion in the analysis. aIncludes six participants randomized to receive a comparator ART who had viremia at their last visit on comparator drug and subsequently switched to B/F/TAF in the open-label extension phase of the studies. ART antiretroviral therapy, B bictegravir, F emtricitabine, TAF tenofovir alafenamide

Overall, compared with participants without any viremic events, those with ≥ 1 viremic event were significantly more likely to be treatment naïve, younger, Black, have baseline HIV-1 RNA ≥ 50 copies/mL, have lower baseline cluster of differentiation 4 (CD4) count, and have CD4 < 200 cells/μL) (Table 1). Sex at birth and being of Hispanic or Latine ethnicity did not significantly predict the occurrence of viremic events. Participants with viremic events on a comparator ART had a median (quartile [Q]1, Q3) age of 38 (27, 50) years and were predominantly male at birth (9/14; 64%) and Black (9/14; 64%).

Table 1.

Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics

| Participants with ≥ 1 viremic event on B/F/TAF | Participants without viremic events ( n = 2511) | P-valuea | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All (n = 290) | Treatment naïve (n = 145) | Virologically suppressed (n = 145) | |||

| Treatment naïve, n (%)b | 145 (50.0) | 145 (100.0) | 0 | 479 (19.1) | < 0.0001 |

| Virologically suppressed, n (%)b | 145 (50.0) | 0 | 145 (100.0) | 2032 (80.9) | |

| Age, years, median (Q1, Q3)c | 36 (25, 50) | 29 (25, 40) | 44 (29, 54) | 44 (32, 54) | 0.0010 |

| Sex at birth, n (%) | 0.2099 | ||||

| Male | 239 (82.4) | 132 (91.0) | 107 (73.8) | 2067 (82.3) | |

| Female | 51 (17.6) | 13 (9.0) | 38 (26.2) | 444 (17.7) | |

| Race, n (%)d | 0.0005 | ||||

| American Indian, Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian, or Pacific Islander | 3 (1.0) | 2 (1.4) | 1 (0.7) | 18 (0.7) | |

| Asian | 9 (3.1) | 1 (0.7) | 8 (5.5) | 66 (2.6) | |

| Black | 142 (49.1) | 68 (47.2) | 74 (51.0) | 987 (39.4) | < 0.0001 versus non-Black |

| White | 125 (43.3) | 68 (47.2) | 57 (39.3) | 1292 (51.6) | |

| Other | 10 (3.4) | 5 (3.4) | 5 (3.4) | 141 (5.6) | |

| Hispanic or Latine, n (%)d | 53 (18.3) | 29 (20.1) | 24 (16.6) | 457 (18.3) | 0.3037 |

| HIV-1 RNA, log10 copies/mL, median (Q1, Q3) | 3.0 (1.3, 4.7) | 4.7 (4.3, 5.1) | 1.3 (1.3, 1.3) | 1.3 (1.3, 1.3) | |

| HIV-1 RNA < 50 copies/mL, n (%)c | 137 (47.2) | 0 | 137 (94.5) | 2002 (79.7) | 0.0003 |

|

CD4 count, cells/μL, median (Q1, Q3)c |

523 (341, 755) | 391 (237, 529) | 693 (490, 926) | 666 (476, 881) | 0.0070 |

| CD4 count < 200 cells/μL, n (%)c | 31 (10.7) | 27 (18.6) | 4 (2.8) | 78 (3.1) | 0.0040 |

aWith versus without any viremic event

bParticipants randomized to B/F/TAF in Studies 1489 and 1490 are included in the treatment-naïve group; all other participants are included in the virologically suppressed group

cDefined at the first dose date of B/F/TAF

dOne participant with ≥ 1 viremic event and seven participants without viremic events were missing race (n = 7) and/or ethnicity data (n = 8) owing to local regulators not permitting the collection of this information, and were therefore excluded from percentage and P-value calculations

B bictegravir, CD cluster of differentiation, F emtricitabine, Q quartile, TAF tenofovir alafenamide

Efficacy Outcomes

Overview of Viremic Events

In total, 411 viremic events were identified among 290 participants receiving B/F/TAF, with 219 (75.5%) experiencing one viremic event. Of those with multiple viremic events (i.e., separated by periods of virologic suppression [HIV-1 RNA < 50 copies/mL]), 49 (16.9%) experienced two viremic events and 22 (7.6%) experienced three or more. These values were similar between treatment-naïve participants and those who were virologically suppressed at their first dose of B/F/TAF (data not shown). At the participant level, the first viremic event occurred a median (Q1, Q3) of 254 (135, 541) days after first virologic suppression following B/F/TAF initiation.

Resuppression after a Viremic Event

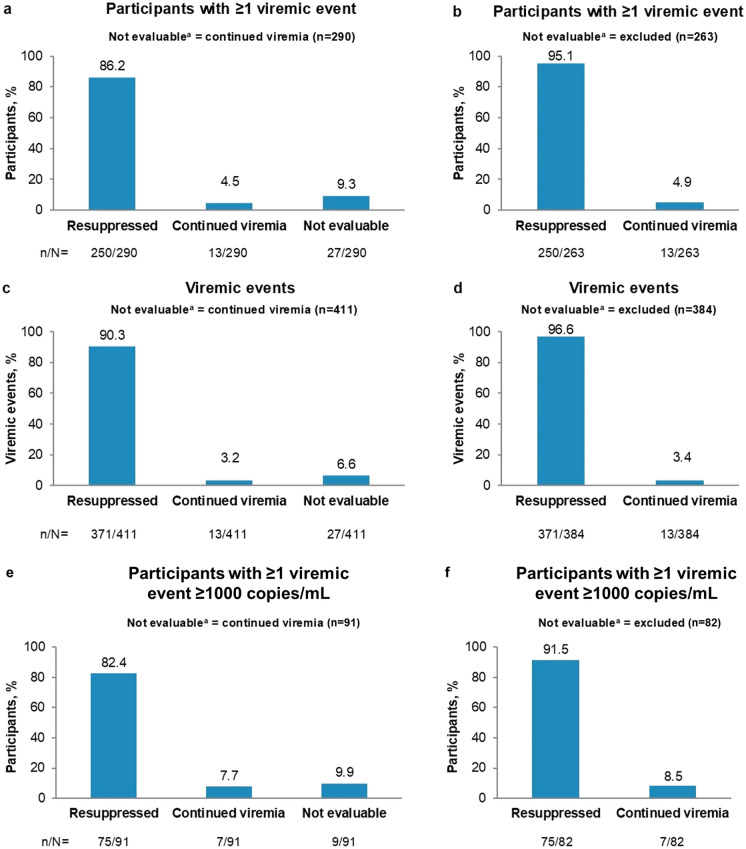

Among participants with ≥ 1 viremic event, 250/290 (86.2%; 95% CI: 81.7–90.0%) achieved resuppression after their last viremic event (Fig. 3). When nonevaluable events were excluded, resuppression was achieved in 250/263 participants (95.1%; 95% CI: 91.7–97.3%). At the event level, 371/411 of viremic events (90.3%; 95% CI: 87.0–93.0%) were followed by resuppression, rising to 371/384 (96.6%; 95% CI: 94.3–98.2%) when nonevaluable viremic events were excluded (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Virologic outcomes following viremic events on B/F/TAF. Main analysis with viremic event threshold ≥ 50 copies/mL: (a and b) outcomes per participant, based on outcome of last viremic event; (c and d) outcomes per viremic event. Sensitivity analysis with viremic event threshold ≥ 1000 copies/mL: (e and f) outcomes per participant, based on outcome of last viremic event. Data were analyzed using the “not evaluable = continued viremia” approach (a, c, e) and using the “not evaluable = excluded” approach (b, d, f). aNot evaluable = virologic event at last assessment. B bictegravir, F emtricitabine, TAF tenofovir alafenamide

The median (Q1, Q3) time from a viremic event to documented resuppression at a subsequent clinic visit was 22 (18, 36) days (Table 2). The median (Q1, Q3) HIV-1 RNA at the start date of the viremic event for all viremic events (n = 411) was 2.25 (1.88, 3.01) log10 copies/mL. The median (Q1, Q3) follow-up time (and sustained suppression on B/F/TAF) after resuppression of the last viremic event, based on HIV-1 RNA measurements, was 319 (127, 797) days.

Table 2.

Characteristics of viremic events on B/F/TAF

| Days, median (Q1, Q3) | Number of events | |

|---|---|---|

| Time from suppression to viremic event | 225 (85, 500) | 411 |

| Time from viremic event to resuppression | 22 (18, 36) | 371 |

| Duration of continued viremia | 72 (43, 87) | 13 |

| HIV-1 RNA, log10 copies/mL, median (Q1, Q3) | Number of events | |

|---|---|---|

| At time of any viremic event | 2.25 (1.88, 3.01) | 411 |

Data are based on viral load assessments made at scheduled or unscheduled clinic visits

B bictegravir, F emtricitabine, Q, quartile, TAF tenofovir alafenamide

Time to Resuppression following Viremic Events on B/F/TAF

Among participants who experienced a viremic event on B/F/TAF, and for whom complete HIV-1 RNA data were available for the subsequent visits, 192/242 (79.3%; 95% CI: 73.7–84.3%) had achieved resuppression by week 4 (baseline reset at the date of last viremia) and 197/207 (95.2%; 95% CI: 91.3–97.7%) had achieved resuppression by week 12 following the viremic event (Supplementary Digital Content Fig. S1). All participants with complete HIV-1 RNA data up to week 36 after the viremic event achieved resuppression (160/160).

At week 24 after the first viremic event (baseline reset at the date of first viremia), 205/225 participants (91.1%; 95% CI: 86.6–94.5%) had HIV-1 RNA < 50 copies/mL. By week 48, 149/157 participants (94.9%; 95% CI: 90.2–97.8%) had HIV-1 RNA < 50 copies/mL.

Participants with Continued Viremia

Among the 13 participants with continued viremia, the median (Q1, Q3) duration of viremia from the first instance of HIV-1 RNA ≥ 50 copies/mL to the last HIV-1 RNA assessment on B/F/TAF was 72 (43, 87) days (Table 2). In total, 9 of the 13 participants (69.2%) had continued viremia with ≥ 200 copies/mL (i.e., not low-level viremia) and a median (Q1, Q3) duration of 79 (30, 127) days. Of these nine participants, seven had continued viremia with ≥ 1000 copies/mL. In total, 11 of the 13 participants (84.6%) with continued viremia prematurely discontinued B/F/TAF (4 lost to follow-up, 4 due to participant’s decision, and 3 due to lack of efficacy), 1 participant remained on B/F/TAF to study completion and continued on B/F/TAF (Study 4030), and 1 participant was still on B/F/TAF in Study 1474 at the time of this analysis.

Resuppression with B/F/TAF after a Viremic Event on Comparator ART

Among the 14 participants who had viremia on a comparator ART before switching to B/F/TAF, 100% achieved resuppression on B/F/TAF, although 6 had a subsequent viremic event on B/F/TAF. The median (Q1, Q3) HIV-1 RNA at the first assessment of the viremic event for these 14 participants was 2.5 (2.0, 4.3) log10 copies/mL. The median (Q1, Q3) time from a viremic event to documented resuppression at a subsequent clinic visit was 25 (21, 42) days.

As expected, the median (Q1, Q3) baseline HIV-1 RNA at study entry for treatment-naïve participants (from Studies 1489 and 1490, n = 634) of 4.42 (4.00, 4.88) log10 copies/mL was higher than that reported above for participants who were virologically suppressed prior to experiencing a viremic event (either on B/F/TAF or a comparator ART). For these treatment-naïve participants, the median (Q1, Q3) time from study day 1 to documented virologic suppression was 29 (29, 33) days.

Treatment Naïve versus Virologically Suppressed at First Dose of B/F/TAF

Among 145 participants who were treatment naïve at first dose of B/F/TAF who experienced ≥ 1 viremic event, 134 (92.4%; 95% CI: 86.8–96.2%) achieved resuppression after their last viremic event. When nonevaluable events were excluded, resuppression was achieved in 134/138 participants (97.1%; 95% CI: 92.7–99.2%).

Among the 145 participants who were virologically suppressed on their first dose of B/F/TAF and who had ≥ 1 viremic event, 116 (80.0%; 95% CI 72.6–86.2%) achieved resuppression after their last viremic event. When nonevaluable events were excluded, resuppression was achieved in 116/125 participants (92.8%; 95% CI: 86.8–96.7%).

For comparison, the median (Q1, Q3) HIV-1 RNA for treatment-naïve participants at the date of last viremia was 2.29 (1.93, 3.29) log10 copies/mL, compared with 2.19 (1.85, 2.96) for virologically suppressed participants.

Baseline Genotype Resistance Data for Participants with a Viremic Event

Analysis of preexisting primary resistance substitutions for the overall population (not limited to participants with viremic events) has previously been published both for the treatment-naïve [25] and virologically suppressed [15, 26–30] participants in this analysis.

As part of our analysis, baseline genotyping data were available for 284/290 participants (97.9%) with viremic events on B/F/TAF. The most frequent preexisting primary resistance substitutions overall were K103N/S (n = 28), E138A/G/K/Q/R (n = 16), M184I/V (n = 14), and G190A/E/Q/S (n = 11) in RT (Table 3). The proportion of participants (with available data) with M184V/I among those with viremic events (4.9%; 14/284) was similar to the proportion in the overall population (6.6%; 177/2690).

Table 3.

Baseline genotype data for participants with viremic events on B/F/TAFa

| INSTI-R (n = 281) | NRTI-R (n = 284) | PI-R (n = 284) | NNRTI-R (n = 284) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participants with preexisting primary resistance, n (%) | 8 (2.8) | 29 (10.2) | 11 (3.9) | 56 (19.7) |

| Primary resistance substitutions (n) |

T97A (4) E92G/Q (2) R263K (1) Y143C/H/R (1) |

M184I/V (14) K219E/N/Q/R (7) T215Y/F (7) K70E/R (6) M41L (6) D67N (3) L210W (3) L741/V (1) |

L90M (5) I84V (3) M46I/L (3) D30N (2) I54M/L (1) N83D (1) Q58E (1) V82A/F/L/S/T (1) |

K103N/S (28) E138A/G/K/Q/R (16) G190A/E/Q/S (11) Y181C/I/V (7) K101E/P (6) V108I (4) Y188C/H/L (3) M230I/L (2) V106A/M (2) H221Y (1) L100I (1) P225H (1) |

aRates of preexisting primary resistance among participants with viremia on comparator ART were 0% for INSTI-R, 14.3% (2/14) for NRTI-R, 14.3% (2/14) for PI-R, and 21.4% (3/14) for NNRTI-R

ART antiretroviral therapy, INSTI integrase strand-transfer inhibitor, NNRTI nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor, NRTI nucleoside/nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitor, PI protease inhibitor, R resistance

Of the 14 participants with M184V/I receiving B/F/TAF, 10 (71.4%) had virologic suppression after their last viremic event, 3 (21.4%) had continued viremia, and 1 (7.1%) did not have an evaluable outcome after viremia. Of the eight participants with INSTI resistance receiving B/F/TAF, 7 (87.5%) had virologic suppression after their last viremic event and 1 (12.5%), with T97A, had continued viremia.

Postbaseline Virology Data

Of the 13 participants who had continued viremia after their last viremic event, 8 (61.6%) met the criteria for postbaseline resistance testing and had data available for PR/RT/IN. None had treatment-emergent resistance to study drugs.

Study Drug Adherence

Among participants without viremia who had available adherence data (n = 2491), the median (Q1, Q3) adherence rate was 98.2% (95.5%, 99.4%); in those with viremia (n = 290), it was 96.6% (92.0%, 99.0%). A significantly higher proportion of participants with viremic events had low adherence (< 85%) to B/F/TAF compared with those without viremic events (10.0% and 4.2%, respectively; p = 0.0003) (Fig. 4). Similar to the overall study population, resuppression after last viremia was achieved in 21/23 participants (91.3%; 95% CI: 72.0–98.9%) with < 85% adherence when nonevaluable data were excluded.

Fig. 4.

B/F/TAF adherence. Participants who returned ≥ 1 pill bottle and had calculable drug adherence were included. B bictegravir, F emtricitabine, TAF tenofovir alafenamide

The adherence rate, duration of viremia on B/F/TAF, and last HIV-1 RNA measurement on B/F/TAF for the 13 participants with continued viremia are shown in Supplementary Digital Content Table S1. Two of these participants (15.3%) had < 85% adherence.

Among the 14 participants with viremia on a comparator ART before switching to B/F/TAF, 3 (23.1%) had < 85% adherence to B/F/TAF.

Sensitivity Analyses

Similar overall findings were observed when the analysis was repeated with the HIV-1 RNA threshold for a viremic event set to ≥ 1000 copies/mL (Fig. 3, e and f). This was also the case for results from an additional analysis with the threshold set to ≥ 200 copies/mL. Full details can be found in Supplementary Digital Content Sensitivity Analyses.

Discussion

We conducted a pooled analysis of eight B/F/TAF clinical trials to assess rates of viremic events and subsequent virologic outcomes in both treatment-naïve and virologically suppressed individuals. To our knowledge, this is the largest study to date to assess the outcome of viremic events in PWH following virologic suppression with B/F/TAF. We found that most people on B/F/TAF did not experience a viremic event and that the majority of the observed viremic events resolved without the need for treatment change.

Of note, our definition of a viremic event included individuals with HIV-1 RNA ≥ 50 copies/mL. This is a lower threshold than included in some studies [31, 32]. Thus, it is possible that some of the viremic events may have been related to reasons other than increased viral replication (e.g., biologic variability of the assay at low viral loads [33], differences in blood sample processing, and so on), resulting in a more heterogeneous group of individuals than if a higher viral event threshold had been used. It was encouraging, therefore, that high rates of virologic suppression were observed and that these were in keeping with results seen in clinical practice [34]. Moreover, the rates of virologic suppression and the median time from viremia to documented virologic resuppression were similar when a viremic event was defined as HIV-1 RNA ≥ 50 copies/mL (main analysis), ≥ 200 copies/mL, or ≥ 1000 copies/mL (sensitivity analyses).

Our results provide insights into the clinical relevance and categorization of viremic events in PWH receiving B/F/TAF. We assessed time from viremia to documented resuppression and also provide data on participants whose viremic events exceeded 200 copies/mL and 1000 copies/mL. Together, these findings indicate that some of the viremic events in our analysis may be categorized in routine clinical practice as virologic blips (isolated viremic events, often with relatively low viral load, preceded and followed by virologic suppression) [1]. Of the 290 participants who experienced ≥ 1 viremic event of HIV-1 RNA ≥ 50 copies/mL, 91 (3.2% from the total population of 2801) experienced ≥ 1 viremic event of HIV-1 RNA ≥ 1000 copies/mL. A total of 13 of these participants experienced more than one viremic event of HIV-1 RNA ≥ 1000 copies/mL.

The two sensitivity analyses performed in this study (≥ 200 copies/mL, and ≥ 1000 copies/mL) allow an estimation of those participants whose continuing viremia would be categorized as low-level (< 200 copies/mL) or unsuppressed viremia (≥ 1000 copies/mL) [1, 22]. In our analysis, approximately 31% of participants (4/13) with continuing viremia had low-level viremia.

The design of this pooled analysis offered a unique opportunity to directly compare virologic outcomes following a viremic event on therapy with outcomes in treatment-naïve participants. Similar results were obtained in those participants who experienced viremic events on B/F/TAF, those who experienced viremic events on comparator ART before switching to B/F/TAF, and those who were treatment naïve upon entry to Studies 1489 and 1490 and therefore had viremia at study entry (a reference for comparison). These similarities were evident both in the high rates of virologic resuppression and the median time to documented resuppression following viremia or initial suppression upon entry to the studies (22–29 days).

These findings show that viremic events in PWH receiving B/F/TAF show similar characteristics and response to B/F/TAF treatment, regardless of whether they occur in virologically suppressed or treatment-naïve individuals who have yet to achieve virologic suppression. These findings have relevance for clinical practice; currently, the majority of US prescribing information for ART does not include an indication for PWH who have viremia and are treatment experienced [35].

The DHHS guidelines recommend that in people experiencing virologic failure, treatment should focus on the availability of a fully susceptible antiretroviral drug with a high barrier to resistance. International guidelines highlight the importance of achieving virologic suppression and stress the key role that adherence to therapy plays in achieving this [1, 4, 22]. Strategies to improve adherence can include selection of a simple, once-daily ART regimen with minimal side effects and few drug–drug interactions; development of a treatment plan; use of long-acting ART; cognitive behavioral therapy; weekly reminder text messages; and counseling to emphasize the personal benefits of maintaining virologic suppression [1, 36, 37]. As expected, our results showed that adherence of < 85% was significantly associated with viremic events, both in the main analysis and the sensitivity analysis in which a viremic event was defined as HIV-1 RNA ≥ 1000 copies/mL. These findings, and our observations that younger and Black participants experienced higher rates of viremic events, are in line with recent data showing lower rates of adherence among these groups [38]. These results further reinforce the critical role of adherence as a major determinant of virologic suppression and highlight the need to mitigate barriers to adherence in specific populations.

Although participants with lower adherence rates experienced more frequent viremic events, they had a high rate of resuppression. This is in line with a recent analysis showing that 96% of study participants with low adherence (< 85%) to B/F/TAF had virologic suppression at their last study visit [24]. It was also notable that no participant developed treatment-emergent resistance during the study. These findings support both the efficacy and high barrier to resistance previously reported for B/F/TAF [25, 34, 39, 40] and provide further insights into the level of forgiveness associated with B/F/TAF—the ability of ART to maintain viral suppression despite suboptimal adherence [41].

Of note, adherence appeared to be higher in this study than typically observed in observational studies, with around 95% of participants in our analysis having adherence of > 85%. In contrast, a retrospective study in Canada found that almost half of people receiving ART had suboptimal adherence [42]. This may be due to greater adherence support in the clinical trials for individuals who struggle to adhere to therapy, which has previously been shown to improve estimates of adherence to ART in PWH [43–45]. Overall, our findings suggest that with the adherence support provided in a clinical trial setting, the vast majority of PWH who experience viremic events can achieve resuppression, underscoring the importance of providing this support in routine clinical practice.

The current pooled analysis has some inherent weaknesses. First, there was no formal control/comparator group, and it was an exploratory post hoc analysis. In addition, since assessments of viral load were only taken at clinic visits, it was not possible in our analysis to provide more accurate estimates of the time to resuppression. Median follow-up time after resuppression was longer in treatment-naïve participants (92.0 weeks) than in virologically suppressed participants (28.7 weeks), which could potentially confound the interpretation of the results of this analysis. Future research could focus on long-term patterns of virologic suppression in PWH who are virologically suppressed at study entry. Finally, adherence support in the Phase 3/3b trials was provided at the site level rather than being protocol mandated.

A strength of this analysis was that pooling of data from eight clinical trials created a sufficiently large dataset to enable meaningful analysis of relatively infrequent viremic events. The regularity of testing (which is likely more stringent in the clinical trial setting than in typical clinical practice) provides a more accurate insight into the number and duration of viremic events. In addition, the extended duration of the included studies allowed for the capture of viremic event outcomes over prolonged treatment periods. Future research is needed to ascertain whether low-level viremia is associated with virologic failure over a longer follow-up period.

Conclusions

This large post hoc pooled analysis, which included both treatment-naïve and virologically suppressed individuals, showed that most participants receiving B/F/TAF did not experience viremic events and that the viremic events that did occur were associated with low adherence (< 85%). The majority of viremic events resolved with B/F/TAF, without the need for treatment change, supporting the advice from international guidelines.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We thank all participants and investigators involved in the study.

Medical Writing, Editorial, and Other Assistance

Medical writing support, including development of a draft outline and subsequent drafts in consultation with the authors, collating author comments, copyediting, fact checking, and referencing, was provided by Victoria Warwick, PhD, CMPP, and Noel Curtis, PhD, at Aspire Scientific, Ltd (Bollington, UK). Funding for medical writing support for this article was provided by Gilead Sciences, Inc. (Foster City, CA, USA).

Author Contributions

Anton Pozniak, Chloe Orkin, Yazdan Yazdanpanah, Axel Baumgarten, Karam Mounzer, Laurie A. VanderVeen, and José R. Arribas contributed to data analysis or interpretation. Michelle L. D’Antoni, Hailin Huang, Hui Liu, Kristen Andreatta, Christian Callebaut, and Jason T. Hindman contributed to both study design and data analysis or interpretation. All authors reviewed and critically revised the manuscript, approved the final draft, and are accountable for the accuracy and integrity of this work.

Funding

This study, and the journal’s Rapid Service fee, were funded by Gilead Sciences, Inc. (Foster City, CA, USA). The study sponsor, Gilead Sciences, Inc., played a role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, and preparation of the manuscript.

Data Availability

Gilead Sciences shares anonymized individual data upon request or as required by law or regulation with qualified external researchers on the basis of submitted curriculum vitae and reflecting nonconflict of interest. The request proposal must also include a statistician. Approval of such requests is at Gilead Sciences’ discretion and is dependent on the nature of the request, the merit of the research proposed, the availability of the data, and the intended use of the data. Data requests should be sent to DataSharing@gilead.com.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

Anton Pozniak has received honoraria and support for attending meetings from Gilead Sciences, Inc. and ViiV Healthcare. He is the President of NEAT ID, and a member of the guideline committee for BHIVA and EACS. Anton Pozniak’s institution has received grants or contracts from Gilead Sciences, Inc. and ViiV Healthcare. Chloe Orkin has received honoraria from Bavarian Nordic, Gilead Sciences, Inc., GSK, MSD, and ViiV Healthcare, and support for attending meetings from Gilead Sciences, Inc. She is an unpaid member of the governing council of the International AIDS Society. Chloe Orkin’s institution has received grants or contracts from Gilead Sciences, Inc. and ViiV Healthcare. Yazdan Yazdanpanah and Axel Baumgarten declare that they have no conflicts of interest. Karam Mounzer has received honoraria and consulting fees for advisory boards from Epividian, Gilead Sciences, Inc., Janssen Therapeutics, Merck, and ViiV Healthcare. Michelle L. D’Antoni, Hailin Huang, Hui Liu, Kristen Andreatta, Laurie A. VanderVeen, Christian Callebaut, and Jason T. Hindman are employees of Gilead Sciences, Inc., and have received employee stock grants. José R. Arribas has received grants or contracts from Gilead Sciences, Inc. and ViiV Healthcare, and consulting fees from Alexa, Gilead Sciences, Inc., Janssen Therapeutics, Lilly, MSD, Serono, Teva, and ViiV Healthcare. He has received payment for expert testimony from Gilead Sciences, Inc., Janssen Therapeutics, MSD, and ViiV Healthcare.

Ethical Approval

Each study in this analysis was conducted in accordance with the protocol and ethical principles derived from international guidelines including the Declaration of Helsinki of 1964 and its later amendments, Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences International Ethical Guidelines, applicable International Council for Harmonization (ICH) guidelines for Good Clinical Practice (GCP), and all applicable laws, rules and regulations. The protocols for each study were approved by an institutional review board or ethics committee. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Footnotes

Prior Presentation: This manuscript is based on work presented as a poster at the 19th European AIDS Conference (EACS; 18–21 October 2023; Warsaw, Poland).

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents. Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in adults and adolescents with HIV. Department of Health and Human Services. 2024. https://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/sites/default/files/guidelines/documents/adult-adolescent-arv/guidelines-adult-adolescent-arv.pdf. Accessed 9 Aug 2024.

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Behavioral and clinical characteristics of persons with diagnosed HIV infection. Medical Monitoring Project, United States 2022 cycle (June 2022–May 2023). 2024.

- 3.Liu T, Chambers LC, Hansen B, et al. Risk of HIV viral rebound in the era of universal treatment in a multicenter sample of persons with HIV in primary care. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2023;10:ofad257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.European AIDS Clinical Society. EACS Guidelines Version 12.0. 2023. https://www.eacsociety.org/media/guidelines-12.0.pdf. Accessed 9 Aug 2024.

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Behavioral and clinical characteristics of persons with diagnosed HIV infection—Medical Monitoring Project, United States, 2018 cycle (June 2018–May 2019). 2020.

- 6.Gandhi RT, Bedimo R, Hoy JF, et al. Antiretroviral drugs for treatment and prevention of HIV infection in adults: 2022 recommendations of the International Antiviral Society—USA panel. JAMA. 2023;329:63–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gilead Sciences. Biktarvy: summary of product characteristics. 2023. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/biktarvy-epar-product-information_en.pdf. Accessed 22 Jan 2025.

- 8.Gilead Sciences. Biktarvy: prescribing information. 2024. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2024/210251s019lbl.pdf. Accessed 9 Aug 2024.

- 9.Gilead Sciences. Gilead announces new license agreement with the medicines patent pool for access to bictegravir. 2017. https://www.gilead.com/news/news-details/2017/gilead-announces-new-license-agreement-with-the-medicines-patent-pool-for-access-to-bictegravir. Accessed 22 Jan 2025.

- 10.Avihingsanon A, Lu H, Leong CL, et al. Bictegravir, emtricitabine, and tenofovir alafenamide versus dolutegravir, emtricitabine, and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate for initial treatment of HIV-1 and hepatitis B coinfection (ALLIANCE): a double-blind, multicentre, randomised controlled, phase 3 non-inferiority trial. Lancet HIV. 2023;10:e640–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Daar ES, DeJesus E, Ruane P, et al. Efficacy and safety of switching to fixed-dose bictegravir, emtricitabine, and tenofovir alafenamide from boosted protease inhibitor-based regimens in virologically suppressed adults with HIV-1: 48 week results of a randomised, open-label, multicentre, phase 3, non-inferiority trial. Lancet HIV. 2018;5:e347–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gallant J, Lazzarin A, Mills A, et al. Bictegravir, emtricitabine, and tenofovir alafenamide versus dolutegravir, abacavir, and lamivudine for initial treatment of HIV-1 infection (GS-US-380-1489): a double-blind, multicentre, phase 3, randomised controlled non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2017;390:2063–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hagins D, Kumar P, Saag M, et al. Switching to bictegravir/emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide in Black Americans with HIV-1: a randomized phase 3b, multicenter, open-label study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2021;88:86–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kityo C, Hagins D, Koenig E, et al. Switching to fixed-dose bictegravir, emtricitabine, and tenofovir alafenamide (B/F/TAF) in virologically suppressed HIV-1 infected women: a randomized, open-label, multicenter, active-controlled, phase 3, noninferiority trial. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2019;82:321–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maggiolo F, Rizzardini G, Molina JM, et al. Bictegravir/emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide in virologically suppressed people with HIV aged ≥ 65 years: week 48 results of a phase 3b, open-label trial. Infect Dis Ther. 2021;10:775–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Molina JM, Ward D, Brar I, et al. Switching to fixed-dose bictegravir, emtricitabine, and tenofovir alafenamide from dolutegravir plus abacavir and lamivudine in virologically suppressed adults with HIV-1: 48 week results of a randomised, double-blind, multicentre, active-controlled, phase 3, non-inferiority trial. Lancet HIV. 2018;5:e357–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sax PE, Pozniak A, Montes ML, et al. Coformulated bictegravir, emtricitabine, and tenofovir alafenamide versus dolutegravir with emtricitabine and tenofovir alafenamide, for initial treatment of HIV-1 infection (GS-US-380-1490): a randomised, double-blind, multicentre, phase 3, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2017;390:2073–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sax PE, Rockstroh JK, Luetkemeyer AF, et al. Switching to bictegravir, emtricitabine, and tenofovir alafenamide in virologically suppressed adults with human immunodeficiency virus. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;73:e485–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Armenia D, Forbici F, Bertoli A, et al. Bictegravir/emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide ensures high rates of virological suppression maintenance despite previous resistance in PLWH who optimize treatment in clinical practice. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2022;30:326–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gaur AH, Cotton MF, Rodriguez CA, et al. Fixed-dose combination bictegravir, emtricitabine, and tenofovir alafenamide in adolescents and children with HIV: week 48 results of a single-arm, open-label, multicentre, phase 2/3 trial. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2021;5:642–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Food and Drug Administration. NDA 210251 Supplement 14; Clinical Review, Cross Discipline Team Leader and Division Director Summary Memorandum. 2021.

- 22.World Health Organization. The role of HIV viral suppression in improving individual health and reducing transmission: policy brief. 2023. https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/360860/9789240055179-eng.pdf. Accessed 9 Aug 2024.

- 23.Sax PE, Eron JJ, Frick A, et al. Patterns of adherence in bictegravir and dolutegravir-based regimens [CROI Abstract 495]. In: Special issue: abstracts from the 2020 conference on retroviruses and opportunistic infections. Top Antivir Med 2020;28:483.

- 24.Andreatta K, Sax PE, Wohl D, et al. Efficacy of bictegravir/emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide versus dolutegravir-based three-drug regimens in people with HIV with varying adherence to antiretroviral therapy. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2025;80:281–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Acosta RK, Willkom M, Martin R, et al. Resistance analysis of bictegravir–emtricitabine–tenofovir alafenamide in HIV-1 treatment-naive patients through 48 weeks. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2019;63:e02533-e2618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Acosta RK, Willkom M, Andreatta K, et al. Switching to bictegravir/emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide (B/F/TAF) from dolutegravir (DTG)+F/TAF or DTG+F/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) in the presence of pre-existing NRTI resistance. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2020;85:363–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Andreatta K, Willkom M, Martin R, et al. Switching to bictegravir/emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide maintained HIV-1 RNA suppression in participants with archived antiretroviral resistance including M184V/I. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2019;74:3555–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Andreatta K, D’Antoni ML, Chang S, et al. High efficacy of bictegravir/emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide (B/F/TAF) in Black adults in the United States, including those with pre-existing HIV resistance and suboptimal adherence. J Med Virol. 2024;96:e29899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rodriguez CA, Natukunda E, Strehlau R, et al. Pharmacokinetics and safety of coformulated bictegravir, emtricitabine, and tenofovir alafenamide in children aged 2 years and older with virologically suppressed HIV: a phase 2/3, open-label, single-arm study. Lancet HIV. 2024;11:e300–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Andreatta K, Cox S, Chokephaibulkit K, et al. Preexisting and post-baseline resistance analyses in pooled pediatric studies of emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide (F/TAF)-based antiretroviral therapy. Presented at IAS 2023, the 12th IAS Conference on HIV Science 2023. Brisbane, Australia.

- 31.Oomen PGA, Wit F, Brinkman K, et al. Real-world effectiveness and tolerability of switching to doravirine-based antiretroviral therapy in people with HIV: a nationwide, matched, prospective cohort study. Lancet HIV. 2024;11:e576–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Elvstam O, Malmborn K, Elen S, et al. Virologic failure following low-level viremia and viral blips during antiretroviral therapy: results from a European multicenter cohort. Clin Infect Dis. 2023;76:25–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ruelle J, Debaisieux L, Vancutsem E, et al. HIV-1 low-level viraemia assessed with 3 commercial real-time PCR assays show high variability. BMC Infect Dis. 2012;12:100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Esser S, Brunetta J, Inciarte A, et al. Twelve-month effectiveness and safety of bictegravir/emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide in people with HIV: real-world insights from BICSTaR cohorts. HIV Med. 2024;25:440–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.HIVinfo.NIH.gov. FDA-approved HIV medicines. 2024. https://hivinfo.nih.gov/understanding-hiv/fact-sheets/fda-approved-hiv-medicines. Accessed 18 Sept 2024.

- 36.Mbuagbaw L, Sivaramalingam B, Navarro T, et al. Interventions for enhancing adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART): a systematic review of high quality studies. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2015;29:248–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nachega JB, Scarsi KK, Gandhi M, et al. Long-acting antiretrovirals and HIV treatment adherence. Lancet HIV. 2023;10:e332–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li P, Prajapati G, Geng Z, et al. Antiretroviral treatment gaps and adherence among people with HIV in the US Medicare Program. AIDS Behav. 2024;28:1002–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sax PE, Arribas JR, Orkin C, et al. Bictegravir/emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide as initial treatment for HIV-1: five-year follow-up from two randomized trials. EClinicalMedicine. 2023;59: 101991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.D’Antoni ML, Andreatta K, Chang S, et al. Brief report: HIV-1 resistance analysis of participants with HIV-1 and hepatitis B initiating therapy with bictegravir/emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide or dolutegravir plus emtricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate: a subanalysis of ALLIANCE data. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2024;96:380–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shuter J. Forgiveness of non-adherence to HIV-1 antiretroviral therapy. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2008;61:769–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Angel JB, Freilich J, Arthurs E, et al. Adherence to oral antiretroviral therapy in Canada, 2010–2020. AIDS. 2023;37:2031–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fox MP, Berhanu R, Steegen K, et al. Intensive adherence counselling for HIV-infected individuals failing second-line antiretroviral therapy in Johannesburg, South Africa. Trop Med Int Health. 2016;21:1131–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Uusküla A, Laisaar KT, Raag M, et al. Effects of counselling on adherence to antiretroviral treatment among people with HIV in Estonia: a randomized controlled trial. AIDS Behav. 2018;22:224–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nyoni T, Sallah YH, Okumu M, Byansi W, Lipsey K, Small E. The effectiveness of treatment supporter interventions in antiretroviral treatment adherence in Sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS Care. 2020;32:214–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Gilead Sciences shares anonymized individual data upon request or as required by law or regulation with qualified external researchers on the basis of submitted curriculum vitae and reflecting nonconflict of interest. The request proposal must also include a statistician. Approval of such requests is at Gilead Sciences’ discretion and is dependent on the nature of the request, the merit of the research proposed, the availability of the data, and the intended use of the data. Data requests should be sent to DataSharing@gilead.com.