Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to explore how haematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) recipients define quality of life (QoL) and the impact of receiving a stem cell transplant.

Methods

Qualitative one-on-one semi-structured interviews were conducted with patients aged ≥ 18 years who had received HCT. Interviews were audio recorded, transcribed verbatim and thematically analysed using NVivo 14 software. A patient advisory group (n = 6 patients) co-designed the qualitative interview study and were involved in developing the initial coding framework and themes generated.

Results

Data saturation was reached after 21 interviews (median age 45 years, range 26–71 years). Participants described a change in perspective about the meaning of QoL post-transplant and having to adapt to a ‘new normal’. Specifically, patients described how being immunocompromised post HCT negatively affected social, emotional and occupational QoL. Participants described facing a new, unfamiliar reality post-transplant and a feeling of being un-prepared for the long-term impact of HCT.

Conclusion

Patients require support to cope with continuously changing physical, social, emotional and occupational challenges. Supportive care interventions should be designed to address the impact of being immunocompromised.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00520-025-09578-4.

Keywords: Haematopoietic stem cell transplantation, Quality of life, Immunocompromised, New way of life, Patient input, Qualitative research

Background

Haematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) is an effective therapy for the management of advanced haematological malignancies, non-malignant diseases and bone marrow failure syndromes. Over 4000 autologous and allogeneic transplants are performed in the UK each year [1]. Advances in the use of haploidentical donors for allogeneic transplant, conditioning regimens and supportive care have led to reductions in morbidity and mortality post-transplant. However, the transplant process is intensive and transplant-related complications including graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), allograft rejection and long-term immunocompromisation are common [2, 3].

QoL is a subjective experience, and the importance of domains can vary depending on the patient population [4, 5]. It encompasses subjective evaluations of both positive and negative aspects of life. Whilst current literature tends to focus on negative shifts in QoL post-transplant such as emotional wellbeing, return to work and physical symptoms, there is also evidence to suggest some positive changes in relation to social and family support [6]. This study will contribute to existing work on this topic by providing patient perspectives of these shifts in QoL perceptions.

There are many unmet needs of cancer survivors that current models of care fail to address. Appropriate care models should be patient-centred [7]. Limited qualitative work has been conducted to investigate what QoL means to patients recovering from stem cell transplant and how patients’ perspective of QoL changes post-treatment. Understanding what QoL means for transplant recipients specifically will help inform what the supportive care model should look like for improved outcomes and QoL.

There is a growing interest in gathering QoL data amongst transplant recipients [8, 9]. However, most studies explore physical or emotional aspects of QoL and the impact of a transplant on patients’ functional wellbeing [10]. Studies are typically observational and describe an initial deterioration in QoL after HCT followed by a subsequent improvement in functional wellbeing over time [11]. Existing studies indicate patients feel that having a pre-defined set of items exploring pre-defined domains of QoL cause them to miss important domains of QoL that are relevant to the patient [8, 12–14]. Few studies have explored how patients’ self-evaluation and perception of QoL can shift after treatment, particularly in relation to changing values and internal standards [15]. There is a significant gap when it comes to defining QoL from the patient’s perspective. This study addresses this research gap by documenting what matters to patients when it comes to QoL measurement. This insight is essential and could be used to indicate whether existing standardised QoL measures reflect patient experience. Furthermore, exploring the multifaceted impact of HCT in depth will support the development of supportive care interventions for transplant patients.

The purpose of this study was to explore how HCT recipients define QoL and the impact of receiving a stem cell transplant. In addition, this study explored how patients perceive their quality of life to have changed since receiving their transplant.

Methods

Study design

This was a qualitative study using one-on-one semi-structured interviews. All interviews were conducted online via Microsoft teams. The study was performed in accordance with, and received approval from, the Anthony Nolan Research Review Board (RRB). The consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ) checklist was followed [16].

Patient involvement and co-design

A patient advisory group (PAG) of individuals (n = 6) with lived experience of receiving a transplant were involved in the development of the study. The PAG members were recruited using an advert that was shared through Anthony Nolan patient and family channels. Our aim was to recruit a diverse range of 6–8 PAG participants who had different lived experience of receiving a transplant. Members of the PAG represent a diverse range of participants in terms of age, gender, ethnic background, those with caring responsibilities and those receiving benefits or other financial support. Two initial online meetings were held with the PAG to identify patient perspectives on what elements of QoL post-transplant should be explored during the study. Draft study materials were then developed and presented to the PAG for feedback during a 1-day workshop. During the workshop, the PAG were involved in co-creating the study adverts, participant information sheets and interview topic guide (see supplementary files A, B and C). PAG members also took part in a mock focus group testing the interview topic guide in practice. After the interviews had been conducted by the study team (GP, KD, CY), the initial emergent thematic map was presented to the PAG. Data triangulation occurred, and the PAG were involved in checking the validity and reliability of the emergent themes and agreeing the final thematic definitions.

Recruitment

Any patient ≥ 18 years of age who had received a transplant within their lifetime was eligible to participate. Using a convenience sampling approach, an open invitation to participate was circulated via Anthony Nolan-hosted patient forums and community channels. The study advert and invite contained a link to register interest. Once the patient had completed the registration form, a member of the research team shared the participant information sheet and consent form and scheduled an interview time.

Interviews and topic guide

Interviews were conducted via videoconference by a member of the research team (GP, KD or CY). Online interviews meant that interviews could be face-to-face, rather than via phone call. This was beneficial as it meant interviewers could consider the body language and facial expressions of participants as they spoke. Participants were able to take part in the study in an environment where they are comfortable. In-person interviews would have been beneficial; however, some participants involved in this study were immunocompromised, and so this would have been a challenging ask. All interviews followed the same semi-structured topic guide which was developed in partnership with the PAG (Supplementary file C) [17]. Interviews were continued until data saturation was reached, meaning no new themes emerged. [10, 11].

Qualitative analysis

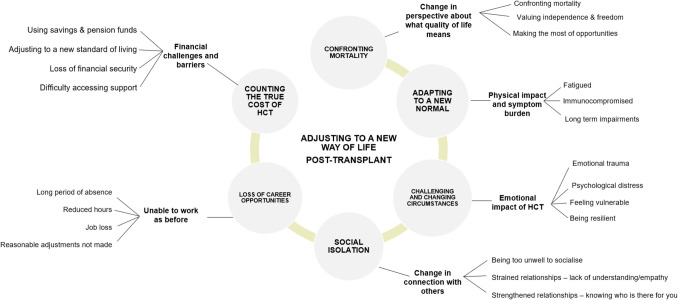

All interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. The analysis was carried out using the NVivo 14 (QSR International) qualitative analysis software and applied the Braun & Clarke’s six-phase approach to thematic analysis [18]. GP led the analysis and generated initial thematic codes; second coding was conducted by KD. Codes and themes were discussed within the research team before being presented to the PAG for feedback. The PAG were involved in co-designing the thematic map (Fig. 1). Representative quotes were selected to illustrate each emergent theme. Data on patients’ perspectives towards QoL post-transplant is included within this article, data collected on patient reported outcome measures (PROMs) is currently under review.

Fig. 1.

Thematic map. Diagram of emergent themes arising from interviews with patients, showing how each theme is interconnected

Incentive vouchers

A £25 incentive was offered to all interview participants. In line with NIHR funding guidance, all PAG members also received voucher payments (£25p/h) as renumeration for their involvement in the study.

Results

Participant characteristics

Table 1 outlines the demographic and transplant characteristics of participants. Data saturation (defined as the point at which no new themes emerged) was reached following 21 interviews. Thirty patients expressed an interest in taking part in the study. Two patients dropped out due to illness ahead of the scheduled interview, five were excluded because they did not meet the eligibility criteria of receiving a transplant in the UK, and two interviews were excluded from analysis due to poor audio quality. Most patients were female (57%, n = 12) and White British (67%, n = 14) and over 45 years of age (71%, n = 15). The average time since transplant was 6 years (standard deviation ± 7 years). Almost a quarter (24%, n = 5) of participants were in receipt of social benefits, 29% (n = 6) had caring responsibilities and 48% (n = 10) lived rurally or > 2-h distance from a transplant centre.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics for study

| Participants | 21 |

|---|---|

| Median age (range) years | 45 (26–71) |

| N (%) | |

| Time since transplant | |

| < 1 year | 6 (29) |

| 1–5 years | 7 (33) |

| 6–10 years | 4 (19) |

| 11 + years | 4 (19) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 9 (43) |

| Female | 12 (57) |

| Diagnosis | |

| Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia | 5 (24) |

| Acute myeloid leukaemia | 8 (38) |

| Myeloma | 3 (14) |

| Myelodysplastic syndrome | 3 (14) |

| Non-Hodgkins lymphoma | 1 (5) |

| Multiple cancers | 1 (5) |

| Transplant | |

| Autologous | 2 (10) |

| Match related | 5 (24) |

| Match unrelated | 13 (62) |

| Mis-match unrelated | 1 (5) |

| Socioeconomic characteristics | |

| Live a distance from transplant centre | 10 (48) |

| Receive benefits | 5 (24) |

| Caring responsibilities | 6 (29) |

| Ethnicity | |

| White British | 14 (67) |

| Indian | 1 (5) |

| Bangladeshi | 1 (5) |

| Other white | 3 (14) |

| Other ethnicity | 2 (10) |

| Index of multiple deprivation | |

| IMD 2 (most deprived) | 2 (11) |

| IMD 3 | 1 (5) |

| IMD 4 | 1 (5) |

| IMD 6 | 4 (16) |

| IMD 8 (least deprived) | 3 (11) |

| Missing data | 10 (53) |

Qualitative interviews

All interviews were conducted in September 2023 via MS Teams. The average interview duration was 55 min (range 32–82 min).

Emergent themes

Figure 1 outlines emergent themes from interviews which asked patients to describe the impact of transplant on their QoL. During discussions with the PAG, the thematic map was developed as a circular linked diagram, with connections between each theme designed to demonstrate how the physical and emotional toll of transplant, particularly being immunocompromised, influences patient QoL and social, occupational and financial wellbeing. Supplementary file D presents supporting quotations.

Confronting mortality

Receiving a transplant altered patients’ perspective of what QoL means.

It’s definitely diminished in a lot of ways. And it’s to a certain extent mentally freed me in others. Because I think priorities change, shift, you get a different perspective. But quality of life is definitely significantly diminished, compared to pre-transplant [P13].

Often patients’ change in perspective towards QoL was a result of having to confront their own mortality. Participants described how post-transplant, they became focused on staying healthy and doing everything they could to stay alive. This often meant altering their lifestyle to avoid the risk of infection:

I was always going to be uber careful. So, I wasn’t the sort of person that would have gone, “Ah, if the pubs are open, I’ll go for a quick one anyway, I’ll be alright.” I was like, “No, my jobs to get healthy. Why would I take a risk? If I get ill, I die [P13].

Other participants described wanting to make the most of life post-transplant and how they now embraced new opportunities. The impact of being faced with mortality influenced some participants to want to not take life post-transplant for granted.

I think one of the interesting things about the whole transplant experience… it’s given me a kind of vigour to learn more and to experience more [P2].

Adapting to a new normal

Participants described adapting to a new normal when asked about the physical impact of receiving a stem cell transplant. Physical factors including fatigue, treatment-related side-effects and being immunocompromised significantly impacted the day-to-day life of patients.

I find it hard to do daily things. I find it hard to have the energy to stand up and actually cook food and things like that and hold my toddler… [P8].

About six months after the transplant I had started getting symptoms of hot flushes, and not being able to sleep, and sweats and headaches and low mood, and that's when they tested my hormones and said ‘you're in chemo induced menopause now… [P1].

Participants talked about the frustrations of not being able to return to their pre-transplant level of fitness and physical activity, stating that ‘you don’t have the abilities you had before, and you’re just lying in bed’ [P15].

Being immunocompromised after transplant has a significant physical impact on patients. Participants describe changes they had to make to their daily routine to avoid infection. Often, this meant isolating at home and being unable to see family and friends for a prolonged period.

A number of my friends and family wanted to come and see me. I knew that I had to pace that because of my immune system [P10].

Some participants reflected on their experience of receiving a transplant during COVID and how this highlighted further the risks of being immunocompromised.

And then, coming out of the period when most people would have stopped isolating, it was I guess more elongated for us, because when everything opened up, we didn’t [P13].

Challenging and changing circumstances

Receiving a transplant was emotionally challenging for patients. During the interviews, participants disclosed feelings of trauma and psychological distress and struggling to reconcile with how vulnerable they were as a result of being so severely immunocompromised:

So, I suppose it's a traumatic, emotional experience where I actually felt really empty and scared. I felt very alone at that time [P10].

Participants were often frustrated that once they were in remission or recovering post-transplant, others would assume they were now healthy. Participants often described how family and friends were unaware of the full extent of the physical and psychological impact of transplant. This often led patients to feel misunderstood.

And then the next natural question from everyone is, “Oh, but aren’t you in remission now?” Like, “Yes, that doesn’t mean I’m okay [P13].

Other participants described experiencing psychological growth post-transplant; the change in perspective about life in general was often accompanied by a determination to survive and demonstrate courage in the face of adversity.

I just felt that I had to keep going, you know [P18].

I think whatever doesn’t kill you makes you stronger [P22].

Social isolation

Most participants were immunocompromised as a result of their transplant and described being anxious and concerned about picking up an infection in social settings. As a result, many participants felt they were unable to socialise as they did pre-transplant.

That’s something that then reflects in wanting to do some of the social things that I would have done previously, or have a “normal” social life, but then reality hits of, I don’t want to get the tube for an hour, because I’m going to get a cold. And if I go and sit in a bar for four hours, I’m likely to get ill, and/or how is the fatigue going to kill me the next day? If I want to drink alcohol, how is my acid reflux, because I’ve got GvHD in my stomach, going to impact me? [P13].

Being immunocompromised and needing to shield had a detrimental impact on relationships. Many reflected that their relationships with friends and family became strained due to a lack of empathy and understanding when they were too unwell to attend social events they had been invited to.

And so, the anxiety over getting ill reflects in me getting ill, in a slightly different way. So, that then turns into declining invitations last minute because I’m ill, because I was worried about getting ill, which leads to not being invited in the future [P13].

Becoming isolated from friends and family who may not fully understand the complexity of life post-transplant was another key concern. There was a strong feeling amongst participants that ‘it was very easy to become an isolationist’ [P13] because of the long-term impact of being immunocompromised. In one circumstance, a participant who was diagnosed with myeloma claimed they ‘felt very, just not connected, disjointed. I couldn’t talk to anybody’ [P10].

Alternatively, others described their social relationships with friends and family to be strengthened following transplant. They recognised the ones who stood by them, and those who supported them throughout their recovery process.

It was when I was bedridden earlier in the year, and I was upset, and my husband said to me, “I really enjoy looking after you.” He’s never had to do that… [P10].

Loss of career opportunities

When asked about the impact of transplant on their occupational wellbeing, participants reflected on the challenges of returning to work and coming to terms with the inability to work as they did before. For example, working reduced hours, outright job loss and having to give up previous careers.

…So, you get a feeling that you are not back to normal, because now you need to focus more on your health. Or you need to either find a job that's less stressful, that doesn't require lots of hours, that you can take some rests in between, so it's not going to be the same [P15].

Participants described a loss of self-worth at being unable to return to their previous careers and feelings of reduced social worth. For many participants, their career made them feel ‘valued, I had something to contribute that was important’ [P1].

Participants who had returned to work post-transplant commented that often their employers were unable or reluctant to make reasonable adjustments to facilitate their return. Employers were often unaware about long-term effects of receiving a transplant on individuals physical and mental function. Employers lack of knowledge about the needs of patients following transplant was distressing for participants, and many felt that it was their own responsibility to advocate for adjustments to be made.

…a lot of difficult conversations with a head teacher who hadn't had any experience with anyone like me…When I returned to work it was a lot of hassle because his awareness of reasonable adjustment was poor at best [P1].

Counting the true cost of transplant

Long periods of absence during post-transplant recovery and the inability to return to work as before often resulted in loss of income and financial security for participants. Many described feeling anxious about their finances and had difficulty staying financially afloat.

So, I’m reliant on benefits just to help pay the mortgage, for example, which at the beginning of the year we had no idea how we were going to find the money [P10].

Participants talked about the need to ‘tap into my pension’ [P10] and ‘significantly dip into savings’ [P2] due to having no income during their recovery. Some also described how the financial impact of transplant often extended to partners and family members who were forced to take long periods of absence from work to provide care for the patient.

Which was probably lucky because he could focus on me as well. But it took a bit of a battering for us because there was nothing coming in, only my sick cover was paying for stuff. Because there was rent and all that stuff going out. Yeah, that was a hard time. I mean, he’s burnt out now. He’s just like, ‘I don’t want to do this anymore [P9].

Difficulty staying on top of mortgage or rent payments was common, and some participants described selling or moving home because of financial pressure.

Staying alive is hard psychologically… I think a big one is once they take your financial security away. I mean we’re alright, but we had to sell our property [P6].

Participants felt let down by the lack of financial support available for patients recovering from a transplant and often described difficulty accessing financial benefits such as Personal Independence Payment (PIP).

I wasn’teligible for any benefits, except for the ESA, so that was really difficult. I’d had sick leave for awhilst, and then I had the stress of having to appeal to the kindness of employers to see if they could extend sick leave after having worked there full time for 11 years [P1].

Other participants were unable to make use of these due to owning a property or having money invested.

We had to take the money that we were squirrelling away, nest eggs and all those things that we had to do and use that to survive because obviously when you tell benefits people that you’ve got a property and you’ve got money invested in it, they say ‘no benefits for you’ [P6].

Being immunocompromised was a central thread throughout all emergent themes. The PAG validated the patient experience and confirmed that this aspect of life post-transplant was something they felt unprepared for and was detrimental to a return to ‘normal’.

Discussion

Patient perspectives of QoL change significantly post-transplant. Within this study, participants described adapting to a new, unfamiliar reality post-transplant, often managing long-term impairments. The most debilitating effect of transplant was being immunocompromised. Patients described how being immunocompromised affected their physical, emotional, social and occupational QoL. Interventions and services to improve QoL post-transplant should provide patients with the coping strategies to prepare for the long-term impact of HCT and self-management skills to support rehabilitation and return to previous levels of functioning [7].

Participants were determined to make the most of life post-transplant. They described the impact of being faced with their own mortality throughout the transplant pathway. For researchers and clinicians, QoL is a standard of health measurement. Current quantitative measures capture pre-defined QoL variables in a specific moment in time. These measures fail to capture the full patient perspective about the meaning of QoL for patients and how this shifts post-transplant. Participants describe post-transplant QoL as the desire to not only survive but thrive.

The impact of being immunocompromised on patient QoL is significant and was a central thread throughout all themes. Whilst the incidence of immunocompromisation following transplant is well documented [19, 20], this study adds novel insights into the extent of how being immunocompromised can impact patient QoL. Priorities shift for patients post-transplant, and QoL becomes focused on staying alive and not putting themselves at risk whilst in a vulnerable position. This is not dissimilar to the experiences of those who were forced to shield during Covid-19. Studies from throughout the pandemic demonstrate that shielding and social isolation had a detrimental impact on mental health. Depression and anxiety were common amongst those who were shielding as psychological isolation led to a perceived lack understanding from others [21, 22]. Patients remain in protective isolation post-transplant to prevent infections. Studies have shown that interventions during hospital isolation such as provision of TV, Wi-Fi and entertainment, as well as prolonged visiting times with family reduces isolation-related distress. [23]. Evidence shows that psychological support provided by HCPs during hospital isolation can reduce distress amongst patients [24]. This support should continue through the post-transplant care pathway. Supportive care interventions should empower patients and promote self-determined action, signposting to resources that can facilitate this.

Adding to previous work, this study shows that social support from family and peers is an important indicator of post-transplant QoL [25–29]. However, this study demonstrated that occupational wellbeing and ability to return to work post-transplant strongly influenced QoL. Patients face a 6-month period of absence from work, potentially longer based on recovery and response to treatment with a lasting financial burden persisting beyond 2 years post-transplant [30–33]. Participants reflected on the challenges faced when returning to work due to vulnerability and immunocompromised status, often, not being able to return to the career they had before affected their self-esteem. Existing studies show there is inadequate support for return to work (RTW) after a period of shielding [34]. Employers should be willing to understand the concerns of patients returning to work post-transplant, for example, uncertainty about job security, occupational status and career progression. Workplaces should have measures in place to make reasonable adjustments when needed to support safe and satisfactory RTW for patients. In addition, our research contributes new insights into post-transplant financial hardship, highlighting the measures patients take to stay afloat.

This study can provide important findings to influence supportive care. By exploring QoL in depth through patient experience, we can have a better understanding of the full impact of transplant on QoL. This in turn can help us better understand what is important to patients, so that we can help inform and improve clinical practice to better meet patients’ supportive care needs post-transplant.

Strengths and limitations

This study presents novel data on patient experience of QoL post-transplant. Semi-structured interviews enabled the collection of patient experience data typically not collected via standard patient reported outcome measures (PROMs). This is particularly in relation to the impact of being immunocompromised on all other measures of QoL. Further, this study has highlighted the impact of transplant on occupational and financial wellbeing, adding real depth to this through data from interviews. A PAG provided input on the study design and interpretation of the results; this ensured that the study conduct and findings were representative of patients’ experience. The final themes were finalised in alignment with patients’ experiences and main concerns.

However, the typical limitations of qualitative research apply [35]. Specific to this study, participants were recruited through convenience sampling through Anthony Nolan patient channels. This may have introduced an element of bias to participant’s experience of transplant as patients on these forums have received stem cells through donor, received a grant from Anthony Nolan or had accessed Anthony Nolan support.

Conclusion

This study adds important new insights into patient QoL post-transplant. In particular, it highlights what is important to patients in relation to their QoL and gives insight into how being physically immunocompromised has a knock-on effect on all other domains of QoL. This data could be used to inform clinical service development to help better meet patient’s supportive care needs. These future supportive care interventions should address the impact of being immunocompromised on QoL.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

(PDF 164 KB)

(PDF 162 KB)

(PDF 148 KB)

(PDF 129 KB)

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Patient Advisory Group for their invaluable input in co-designing and informing this research. We would also like to express gratitude to the study participants for sharing their experiences, insights and perspectives, which significantly contributed to the success of this research.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by GP, KD and CY. The first draft of the manuscript was written by LY and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Therakos UK and the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR205434).

Data availability

Restrictions apply to the availability of the data within this study, however all data and materials are available upon reasonable request made to the corresponding author and with permission from Anthony Nolan.

Declarations

Ethics approval

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was performed in accordance with and received approval from the Anthony Nolan Research Review Board (RRB).

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. Participants consented to interviews being audio-recorded and transcribed and to publication of the findings.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.British Society of Blood and Marrow Transplantation (2022) BSBMTCT registry annual activity. https://bsbmtct.org/activity/2022/. Accessed 30 May 2025

- 2.Inamoto Y, Lee SJ (2017) Late effects of blood and marrow transplantation. Haematol Ferrata Storti Found 102:614–25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Vere Hunt I, Kilgour JM, Danby R, Peniket A, Matin RN (2021) Is this the GVHD? A qualitative exploration of quality of life issues in individuals with graft-versus-host disease following allogeneic stem cell transplant and their experiences of a specialist multidisciplinary bone marrow transplant service. Health Qual Life Outcomes 1:19(1) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.van Lonkhuizen PJC, Heemskerk AW, Slutter L, van Duijn E, de Bot ST, Chavannes NH et al (2024Dec 1) Shifting focus from ideality to reality: a qualitative study on how quality of life is defined by premanifest and manifest Huntington’s disease gene expansion carriers. Orphanet J Rare Dis 19(1):444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sonsby L, Dueholm JR, Danbjørg DB, Abildgaard N, Nielsen LK (2023) Changes in health-related quality of life during multiple myeloma treatment: a qualitative interview study. Oncol Nurs Forum 50(5):635–645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Niederbacher S, Them C, Pinna A, Vittadello F, Mantovan F (2012Jul) Patients’ quality of life after allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation: mixed-methods study. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 21(4):548–559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jefford M, Howell D, Li Q, Lisy K, Maher J, Alfano CM et al (2022) Improved models of care for cancer survivors. The Lancet Elsevier BV 399:1551–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seghers PAL, Kregting JA, van Huis-Tanja LH, Soubeyran P, O’hanlon S, Rostoft S et al (2022) What defines quality of life for older patients diagnosed with cancer? A qualitative study. Cancers (Basel) 1(5):14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Badawy SM, Beg U, Liem RI, Chaudhury S, Thompson AA (2021Jan 26) A systematic review of quality of life in sickle cell disease and thalassemia after stem cell transplant or gene therapy. Blood Adv 5(2):570–583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Le RQ, Bevans M, Savani BN, Mitchell SA, Stringaris K, Koklanaris E et al (2010Aug) Favorable outcomes in patients surviving 5 or more years after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for hematologic malignancies. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 16(8):1162–1170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shaw BE, Lee SJ, Horowitz MM, Wood WA, Rizzo JD, Flynn KE (2016) Can we agree on patient-reported outcome measures for assessing hematopoietic cell transplantation patients? A study from the CIBMTR and BMT CTN. Bone Marrow Transplant Nat Publ Group 51:1173–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hamidou Z, Baumstarck K, Chinot O, Barlesi F, Salas S, Leroy T et al (2017) Domains of quality of life freely expressed by cancer patients and their caregivers: Contribution of the SEIQoL. Health Qual Life Outcomes 12(1):15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bellino S, La Salvia A (2017) The importance of patient reported outcomes in oncology clinical trials and clinical practice to inform regulatory and healthcare decision-making. Drugs in R and D Adis 24:123–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brice L, Gilroy N, Dyer G, Kabir M, Greenwood M, Larsen S et al (2017Feb 1) Haematopoietic stem cell transplantation survivorship and quality of life: is it a small world after all? Support Care Cancer 25(2):421–427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beeken RJ, Eiser C, Dalley C (2011) Health-related quality of life in haematopoietic stem cell transplant survivors: a qualitative study on the role of psychosocial variables and response shifts. Qual of Life Res 20:153–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J (2007) Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care 19(6):349–357 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Naz N, Gulab F, Aslam N (2022) Development of qualitative semi-structured interview guide for case study research. Compet Soc Sci Res J (CSSRJ) 3(2):42–52. www.cssrjournal.com. Accessed 30 May 2025

- 18.Braun V, Clarke V (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 3(2):77–101. https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=uqrp20. Accessed 30 May 2025

- 19.Sahin U, Toprak SK, Atilla PA, Atilla E, Demirer T (2016) An overview of infectious complications after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. J Infect Chemother Elsevier BV 22:505–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Foord AM, Cushing-Haugen KL, Boeckh MJ, Carpenter PA, Flowers MED, Lee SJ et al (2020Apr 14) Late infectious complications in hematopoietic cell transplantation survivors: a population-based study. Blood Adv 4(7):1232–1241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lasseter G, Compston P, Robin C, Lambert H, Hickman M, Denford S et al (2022) Exploring the impact of shielding advice on the wellbeing of individuals identified as clinically extremely vulnerable amid the COVID-19 pandemic: a mixed-methods evaluation. BMC Publ Health 1(1):22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Silverthorne CA, Jones B, Brooke M, Coates LC, Orme J, Robson JC et al (2024) Qualitative interview study of rheumatology patients’ experiences of COVID-19 shielding to explore the physical and psychological impact and identify associated support needs. BMJ Open 22(4):14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Annibali O, Pensieri C, Tomarchio V, Biagioli V, Pennacchini M, Tendas A, Tambone V, Tirindelli MC (2017) Protective isolation for patients with haematological malignancies: a pilot study investigating patients' distress and use of time. Int J Hematol Oncol Stem Cell Res 11(4):313–318 [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Song Y, Chen S, Roseman J, Scigliano E, Redd WH, Stadler G (2021Mar) It takes a team to make it through: the role of social support for survival and self-care after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant. Front Psychol 26:12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Amonoo HL, Johnson PC, Dhawale TM, Traeger L, Rice J, Lavoie MW et al (2021Apr 15) Sharing and caring: the impact of social support on quality of life and health outcomes in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Cancer 127(8):1260–1265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nørskov KH, Yi JC, Crouch ML, Fiscalini AS, Flowers MED, Syrjala KL (2021Dec 1) Social support as a moderator of healthcare adherence and distress in long-term hematopoietic cell transplantation survivors. J Cancer Surviv 15(6):866–875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Amonoo HL, Deary EC, Harnedy LE, Daskalakis EP, Goldschen L, Desir MC et al (2022Jul 1) It takes a village: the importance of social support after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, a qualitative study. Transplant Cell Ther 28(7):400.e1-400.e6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nenova M, Duhamel K, Zemon V, Rini C, Redd WH (2013Jan) Posttraumatic growth, social support, and social constraint in hematopoietic stem cell transplant survivors. Psychooncology 22(1):195–202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Langer SL, Yi JC, Chi NC, Lindhorst T (2020Apr 1) Psychological impacts and ways of coping reported by spousal caregivers of hematopoietic cell transplant recipients: a qualitative analysis. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 26(4):764–771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Majhail NS, Rizzo JD, Lee SJ, Aljurf M, Atsuta Y, Bonfim C et al (2012) Recommended screening and preventive practices for long-term survivors after hematopoietic cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant 47(3):337–41. www.survivorshipguidelines.org. Accessed 30 May 2025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Denzen EM, Thao V, Hahn T, Lee SJ, McCarthy PL, Rizzo JD et al (2016Sep 1) Financial impact of allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation on patients and families over 2 years: results from a multicenter pilot study. Bone Marrow Transplant 51(9):1233–1240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Khera N, Chang hui Y, Hashmi S, Slack J, Beebe T, Roy V et al (2014) Financial burden in recipients of allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Biol Blood and Marrow Transplant 20(9):1375–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Khera N, Hamilton BK, Pidala JA, Wood WA, Wu V, Voutsinas J et al (2019Mar 1) Employment, insurance, and financial experiences of patients with chronic graft-versus-host disease in North America. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 25(3):599–605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Martin A (2024) Experiences of junior doctors who shielded during the COVID-19 pandemic. Clin Teach 1(2):21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mwita K (2022) Strengths and weaknesses of qualitative research in social science studies. 10.2139/ssrn.4880484

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(PDF 164 KB)

(PDF 162 KB)

(PDF 148 KB)

(PDF 129 KB)

Data Availability Statement

Restrictions apply to the availability of the data within this study, however all data and materials are available upon reasonable request made to the corresponding author and with permission from Anthony Nolan.