Abstract

Regenerating limbs retain their proximodistal (PD) positional identity following amputation. This positional identity is genetically encoded by PD patterning genes that instruct blastema cells to regenerate the appropriate PD limb segment. Retinoic acid (RA) is known to specify proximal limb identity, but how RA signaling levels are established in the blastema is unknown. Here, we show that RA breakdown via CYP26B1 is essential for determining RA signaling levels within blastemas. CYP26B1 inhibition molecularly reprograms distal blastemas into a more proximal identity, phenocopying the effects of administering excess RA. We identify Shox as an RA-responsive gene that is differentially expressed between proximally and distally amputated limbs. Ablation of Shox results in shortened limbs with proximal skeletal elements that fail to initiate endochondral ossification. These results suggest that PD positional identity is determined by RA degradation and RA-responsive genes that regulate PD skeletal element formation during limb regeneration.

Subject terms: Mesoderm, Regeneration, Bone development, Cartilage development

How axolotl salamanders know what portion of the limb to regenerate remains a mystery. In this article, the authors show that precise retinoic acid degradation is critical for instructing regeneration of the appropriate limb segment.

Introduction

Tissue regeneration requires a complex cellular choreography that results in restoration of missing structures. Salamander limb regeneration is no exception, where mesenchymal cells, including dermal fibroblasts and periskeletal cells, dedifferentiate into a more embryonic-like state and migrate to the tip of the amputated limb to form a blastema1,2. Mesenchymal cells within the blastema contain positional information which coordinates proximodistal (PD) pattern reestablishment in the regenerating limb, enabling autopod-forming blastema cells to distinguish themselves from stylopod-forming blastema cells3,4. It has been proposed that continuous values of positional information exist along the PD axis and that thresholds of these values specify limb segments5,6. These segments are genetically established by combinations of homeobox genes including Hox and Meis genes7–9, and each limb segment contains a unique epigenetic profile around these homeobox genes10. However, a mechanistic explanation for how continuous values of positional information are established and differentially interpreted by limb segments during limb regeneration is lacking.

Retinoic acid (RA) is a small, pleiotropic molecule that is pervasively involved during vertebrate morphogenesis, including initiating and patterning the developing limb. The prevailing model suggests that RA is synthesized in the lateral plate mesoderm during amniote limb development and diffuses into the limb bud to specify proximal limb identity through activation of Meis genes11–15. An intrinsically timed, antagonizing gradient of fibroblast growth factors (FGFs) emanating from the apical ectodermal ridge (AER) then creates a zone of distal identity marked by Hoxa13 expression15–17. This activates CYP26B1, which eliminates RA from the distal limb cells and creates a gradient of RA that patterns the developing limb PD axis18. Perturbing the establishment of this gradient often results in PD patterning defects18,19. Our understanding of the role of RA in urodele limb development is not as comprehensive as in amniotes, but some aspects have been elucidated. Similar to amniotes, a gradient of active RA signaling exists along the developing urodele PD axis20 and disruption results in abnormal skeletal morphologies along the PD axis21–23.

As in limb development, RA concentration is thought to differentiate the positional identity of upper limb blastemas from lower limb blastemas, thereby ensuring regeneration of the appropriate PD limb structures from disparate amputation planes. RA synthesis occurs endogenously within the blastema in response to injury24,25, and RA signaling is approximately 3.5 times higher in proximal blastemas (PBs) compared to distal blastemas (DBs)26. These endogenous levels of RA are necessary for proper regeneration23,27,28. Furthermore, administering RA to DBs reprograms blastema cells to a proximal identity, resulting in regeneration of more proximal structures in a concentration-dependent manner29,30. This reprogramming is associated with downregulation of distal limb patterning genes like Hoxa13 and upregulation of proximal limb patterning genes like Meis1 and Meis29,22. In agreement with this, perturbing Meis1 and Meis2 in RA treated DBs partially blocks limb duplication31. These studies collectively point to a model whereby heightened RA signaling in PBs specifies proximal positional identity through activation of proximal patterning genes and repression of distal patterning genes. Despite strong evidence that RA regulates positional identity along the regenerating PD axis, the differences in RA signaling levels between PBs and DBs are not fully understood.

In this work, we examine the spatiotemporal expression of limb patterning genes in PBs and DBs and compare it to expression of genes related to RA synthesis, degradation, and signaling. We observed that Cyp26b1 was more highly expressed in mesenchymal cells of DBs than PBs, suggesting that differences in RA signaling levels between PBs and DBs are due to RA degradation. Pharmacological inhibition of CYP26B1 in DBs increases RA signaling and results in concentration-dependent duplications of proximal limb segments. These duplications occur by repressing distal limb patterning genes and activating proximal limb patterning genes. Two such genes, Shox and Shox2, are both RA-responsive and differentially expressed in PBs and DBs. Disruption of Shox yields phenotypically normal autopods but shortened stylopods and zeugopods that fail to initiate endochondral ossification. Moreover, we show that Shox is not required for limb regeneration but is crucial for endochondral ossification of stylopodial and zeugopodial skeletal elements during regeneration. Our results collectively suggest that RA breakdown via CYP26B1 is required for establishing positional identity along the regenerating PD axis, enabling the activation of genes such as Shox that confer proximal limb positional identity.

Results

The spatiotemporal expression of PD patterning genes differs in PBs and DBs

To explore how patterning genes regulate RA signaling in PBs and DBs, we examined the expression of known RA-responsive homeobox genes, including Meis1 and Meis215,31. We assessed the expression of these genes in limbs amputated at the upper stylopod (US), lower stylopod (LS), upper zeugopod (UZ), and autopod levels at 10 DPA using qRT-PCR and found that Meis1 and Meis2 expression decreases in progressively distal amputations (Fig. 1A–C). We next reanalyzed blastema scRNA-seq data from proximally amputated limbs (Fig. S1) to identify cell types expressing Meis1 and Meis232, and found Meis1 expression in mesenchymal and epithelial cells, while Meis2 was undetected (Fig. S2A, B).

Fig. 1. PD patterning genes are dynamically expressed during limb regeneration.

A Schematic of PD amputation plane qRT-PCR experiment. B, C qRT-PCR of Meis1 (B) and Meis2 (C) at different PD amputation locations (3.5 cm (HT) animals aged 2.5 months, 10 DPA). Expression normalized to Ef1a and analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Tukey-Kramer multiple comparisons. Boxplot top and bottom represent the 75th and 25th percentiles, the red line indicates median, and whisker ends show minima and maxima. R2 and p values from linear regression analysis are shown. * = p < 0.05. D HCR-FISH for Meis1 and Meis2 in PBs and DBs at 10 and 14 DPA. Dashed lines indicate amputation plane. Scale bars = 200 µm. E Quantification of mesenchymal Meis1 and Meis2 in PBs and DBs at 10 and 14 DPA (3.5 cm (HT) animals aged 2.5 months). Differences analyzed by two-tailed pairwise clustered Wilcoxon rank-sum tests. * = p < 0.05. F PD intensity plots for mesenchymal Meis1 and Meis2 in PBs and DBs at 10 and 14 DPA (3.5 cm (HT) animals aged 2.5 months). Shaded region represents 99% confidence interval. G–I qRT-PCR of Hoxa9 (G), Hoxa11 (H), and Hoxa13 (I) at different PD amputation locations (3.5 cm (HT) animals aged 2.5 months, 10 DPA). Boxplot and analyses as in (B, C). * = p < 0.05, *** = p < 0.001. J HCR-FISH for Hoxa9, Hoxa11, and Hoxa13 in PBs and DBs at 10 and 14 DPA. Dashed lines indicate amputation plane. Scale bars = 200 µm. K Quantification for mesenchymal Hoxa9, Hoxa11, and Hoxa13 in PBs and DBs at 10 and 14 DPA (3.5 cm (HT) animals aged 2.5 months). Axes and analyses as in Fig. 1E. * = p < 0.05. L PD intensity plots for mesenchymal Hoxa9, Hoxa11, and Hoxa13 in PBs and DBs at 10 and 14 DPA (3.5 cm (HT) animals aged 2.5 months). Axes and analyses as in (F). Sample size and exact p-values are located within the source data file. Source data are provided as a source data file.

We then visualized Meis1 and Meis2 in DBs at 7, 10, and 14 DPA and found Meis1 was primarily expressed in the epithelium while Meis2 was lowly expressed in the mesenchyme and epithelium (Fig. 1D, E, Figs. S2C, D and S3). Similarly, PBs at 7 DPA exhibited low mesenchymal Meis1 and Meis2 expression (Fig. S2C). At 10 DPA, Meis1 was significantly higher in the mesenchyme of PBs, and Meis2 was elevated in PBs but was generally lowly expressed (Fig. 1D, E, Fig. S4). By 14 DPA, Meis1 was significantly higher in PBs and localized to the proximal-most mesenchyme cells, creating a distal zone devoid of Meis1 expression (Fig. 1D–F, Fig. S5). A similar Meis1 expression pattern was observed during axolotl (Figs. S3E and S6A), mouse, and chick limb development33,34, suggesting an evolutionarily conserved role reutilized for limb regeneration. Meis2 was significantly higher in PBs at 14 DPA but was generally lower than Meis1 (Fig. 1D, E). Neither Meis1 nor Meis2 expression differed in the epithelium of PBs and DBs at any time point (Fig. S2D), underscoring the importance of mesenchymal cells in conveying PD positional identity within the blastema.

We next examined Hoxa9, Hoxa11, and Hoxa13 which have a known role in establishing both the amphibian regenerating and developing PD axis by providing positional identity to each limb segment7–9. We observed similar Hoxa9 expression in blastemas at each amputation location (Fig. 1G), while Hoxa11 was elevated in blastemas amputated at the UZ and autopod levels relative to US and LS amputations (Fig. 1H). Hoxa13 was significantly more highly expressed in autopod amputations compared to any other amputation level (Fig. 1I), reflecting activation of more 5’ Hox genes in increasingly distal limb amputations. Additionally, we found that Hoxa9, Hoxa11, and Hoxa13 were expressed in mesenchymal and epithelial cells (Fig. S2F–H).

We observed that Hoxa9, Hoxa11, and Hoxa13 were expressed uniformly in the mesenchyme of DBs at 7, 10, and 14 DPA (Fig. 1J, Figs. S2I and S7). In PBs at 7 DPA, only Hoxa9 was expressed in the mesenchyme while Hoxa11 and Hoxa13 were absent (Fig. S2I). By 10 DPA, Hoxa9 and Hoxa11 were expressed in the mesenchyme of PBs, but Hoxa13 remained low (Fig. 1J, K, Fig. S2J). At 14 DPA, Hoxa9 was expressed throughout the mesenchyme of PBs at similar levels as DBs (Fig. 1J, K, Fig. S2J), and Hoxa11 was detected in cells from the mid-blastema to the distal tip (Fig. 1J–L). Hoxa13 was detected in the distal-most mesenchymal cells of PBs, although at lower levels than in DBs (Fig. 1J–L). This colinear activation of 5’ Hox genes mirrors Hoxa9, Hoxa11, and Hoxa13 expression during limb development (Figs. S2K and S6B), supporting the hypothesis that progressive specification establishes PD positional identity in both processes7.

RA signaling levels within blastemas are determined by Cyp26b1 expression

We hypothesized that RA signaling pathway members regulate RA signaling levels in response to PD patterning genes. We reasoned that a candidate gene would be expressed in the blastema mesenchyme, show graded expression along the PD axis, and complement the spatiotemporal expression of Meis1, Hoxa11, and Hoxa13, which direct limb morphogenesis35. To this end, we focused on RA receptors (Rara, Rarg), genes involved in RA synthesis (Raldh1, Raldh2, Raldh3), and genes involved in RA degradation (Cyp26a1, Cyp26b1). Both Rara and Rarg were expressed in the mesenchyme, but their expression did not match Meis1, Hoxa11, and Hoxa13 (Figs. S8 and S9). Raldh1 and Raldh2 expression did not differ between PBs and DBs, and Raldh3 did not exhibit a spatiotemporal expression pattern comparable to that of Meis, Hoxa11, and Hoxa13 (Figs. S10 and S11). We next investigated RA degradation in PBs and DBs and found that Cyp26a1 expression was higher in US blastemas and decreased in distal amputations (Fig. 2A). Conversely, Cyp26b1 expression was highest in autopod level amputations and decreased in more proximal amputation locations (Fig. 2B). Cyp26a1 and Cyp26b1 expression levels appeared to form gradients independent of limb segment, with similar levels in blastemas amputated at the LS and UZ (Fig. 2A, B). ScRNA-seq did not detect Cyp26a1, but Cyp26b1 was highly expressed in the mesenchyme and epidermis of DBs (Fig. S12A, B). Spatially, Cyp26a1 expression was similar in PBs and DBs and showed no bias towards the epithelium or mesenchyme (Fig. 2C, D, Figs. S12C–E and S13). This difference in Cyp26a1 detection between our HCR-FISH and qRT-PCR results is likely due to the higher sensitivity of qRT-PCR. In contrast, epithelial Cyp26b1 was observed in PBs and DBs at 7 DPA but was more highly expressed in the mesenchyme of DBs (Fig. S12C). By 10 DPA, Cyp26b1 expression was similar in the epithelium of PBs and DBs, but significantly higher in the mesenchyme of DBs (Fig. 2C, D). At 14 DPA, Cyp26b1 was no longer differentially expressed between PBs and DBs (Fig. 2C, D), but was concentrated at the distal tip of PBs, tapering off proximally (Fig. 2E). Finally, the spatiotemporal expression of Cyp26b1 within the mesenchyme resembled that of Hoxa11 and Hoxa13 while appearing negatively correlated with Meis1 (Fig. 2E). These results indicate that Cyp26b1 expression is graded in mesenchymal cells along the PD axis and its spatiotemporal expression correlates with PD patterning genes.

Fig. 2. Cyp26b1 is differentially expressed in PBs and DBs and is related to Meis1, Hoxa11, and Hoxa13 expression.

A, B qRT-PCR of Cyp26a1 (A) and Cyp26b1 (B) at different PD amputation locations (3.5 cm (HT) animals aged 2.5 months, 10 DPA). Boxplot and analyses as in Fig. 1B, C. * = p < 0.05, *** = p < 0.001. C HCR-FISH for Cyp26a1 and Cyp26b1 in PBs and DBs at 10 and 14 DPA. Dashed lines indicate amputation plane. Scale bars = 200 µm. D Quantification for mesenchymal Cyp26a1 and Cyp26b1 in PBs and DBs at 10 and 14 DPA (3.5 cm (HT) animals aged 2.5 months). Axes and analyses as in Fig. 1E. * = p < 0.05. E PD intensity plots for mesenchymal Cyp26b1, Meis1, Hoxa11, and Hoxa13 in PBs and DBs at 10 and 14 DPA. Shaded region represents 99% confidence interval. Axes and analyses as in Fig. 1F. Sample size and exact p-values are located within the source data file. Source data are provided as a source data file.

CYP26 inhibition increases RA signaling and duplicates proximal skeletal structures

We hypothesized that positional identity along the regenerating PD axis depends on RA degradation in the blastema. To test this, we used talarozole (TAL, or R115866) to inhibit CYP26 during limb regeneration. Three TAL concentrations (0.1 µM, 1 µM, and 5 µM) or DMSO were administered at 4 DPA30 to animals with proximally amputated left limbs and distally amputated right limbs for 7 days (Fig. 3A). The skeletal structures of regenerates were then analyzed for abnormalities in morphology (Fig. 3A). At 14 DPA, we observed that drug treated blastemas were smaller than DMSO controls (Fig. S14A, B). After fully regenerating, DMSO treated limbs and proximally amputated limbs treated with 0.1 µM or 1 µM TAL exhibited normal skeletal morphology (Fig. 3B, Table S2). At 5 µM TAL, 15.4% of proximally amputated limbs regenerated without skeletal irregularities while limbs in the remaining 84.6% regressed to the scapula and failed to regenerate (Fig. 3B). Conversely, 92.3% of distally amputated limbs treated with 0.1 µM TAL exhibited whole (61.2%) or partial (30.1%) zeugopod duplications while 7.7% displayed no limb duplications (Fig. 3B). Increasing TAL to 1 µM resulted in full (66.7%) or partial (33.3%) stylopod duplications from distal amputations (Fig. 3B). Treatment with 5 µM TAL inhibited regeneration in 92.3% of distally amputated limbs, while 7.7% showed full humerus duplication (Fig. 3B). These results mirror both the inhibition of limb regeneration by excess retinoids36 and PD duplications observed in regenerating Xenopus laevis hindlimbs after TAL treatment37.

Fig. 3. CYP26 inhibition phenocopies exogenous RA during limb regeneration.

A Timeline of TAL experiments and tissue collection timepoints. B Brightfield images of regenerates and skeletal structures of PBs and DBs treated with DMSO or 0.1, 1, or 5 µM TAL. Dashed lines indicate amputation plane. Scale bar = 2 mm. C 10 DPA DBs from RA reporter animals treated with DMSO or 1 µM TAL (3 cm (HT) animals aged 2 months). Dashed lines indicate amputation plane. Scale bar = 500 µm. D qRT-PCR of Gfp in tissue from RA reporter animals. (3.5 cm (HT) animals aged 2.5 months, 10 DPA). Boxplot and analyses as in Fig. 1B, C. *** = p < 0.001. E HCR-FISH for Cyp26a1 and Cyp26b1 in DBs administered 1 µM TAL at 14 DPA (3.5 cm (HT) animals aged 2.5 months). Dashed line indicates amputation plane. AF = autofluorescence. Scale bar = 200 µm or 20 µm (inset). F Dot quantification for mesenchymal and epithelial Cyp26a1 and Cyp26b1 in DBs treated with DMSO or 1 µM TAL at 14 DPA (3.5 cm (HT) animals aged 2.5 months). Axes and analyses as in Fig. 1E. * = p < 0.05. G 14 DPA DBs from Hoxa13:mCHERRY reporter animals treated with DMSO or 1 µM TAL (7.5 cm (HT) animals aged 6 months). Dashed lines indicate amputation plane. Scale bar = 500 µm. Sample size and exact p-values are located within the source data file. Source data are provided as a source data file.

Limb duplications after TAL treatment resembled the effects of administering excess RA to regenerating limbs. To determine if TAL increased RA signaling, we administered 0.1 µM or 1 µM TAL to RA reporter animals20 and assessed GFP expression in DBs at 10 DPA. We observed increased GFP signal and Gfp expression following TAL administration (Fig. 3C- D), indicating TAL increased RA signaling in the blastema. Additionally, mesenchymal Cyp26b1 decreased in DBs treated with 1 µM TAL while Cyp26a1 expression was unaffected (Figs. 2C and 3E, F, Fig. S14E). However, epithelial Cyp26a1 was elevated following TAL treatment (Fig. 3E-F), suggesting that CYP26A1 degrades detrimental levels of RA in the epithelium but is uninvolved in regulating mesenchymal RA levels.

Previous studies have shown that excess RA decreases Hoxa137,9,22, leading us to hypothesize that Hoxa13 would similarly decrease following TAL treatment. To address this, we utilized Hoxa13 reporter animals38 to visualize the impact of TAL on HOXA13. DMSO treated DBs demonstrated strong mCHERRY signal at 14 DPA, whereas expression was absent in DBs treated with 1 µM TAL (Fig. 3G). We also observed reduced Hoxa13 expression at the transcript level (Fig. S14C, D, F), showing that Hoxa13 decreases following TAL administration.

Our results indicate that TAL increases mesenchymal RA signaling in DBs, leading to both concentration-dependent increases in RA signaling and skeletal morphologies that mimic RA-induced limb duplications. Considering Cyp26a1 and Cyp26b1 expression (Figs. 2C, D and 3E, F), the final skeletal morphologies are likely due to inhibition of CYP26B1, not CYP26A1. Moreover, we observed no change in skeletal morphology of proximally amputated limbs treated with the same TAL concentration that caused full limb duplication in distally amputated limbs, indicating RA breakdown is crucial for positional identity in distally, not proximally, amputated limbs. However, most PBs treated with 5 µM TAL failed to regenerate, suggesting that some RA breakdown is necessary for limb regeneration in PBs (Fig. 3B, Table S2).

Limb duplications require RA synthesis and RAR activity

To elucidate the mechanism behind TAL-induced proximalization of DBs, we cotreated animals with TAL and either disulfiram (DIS), a pan RALDH inhibitor, or AGN 193109 (RAA), a pan-RAR antagonist. Treatments were administered as above (Fig. 3A), with DIS or RAA administered alone or with 1 µM TAL. DMSO treated limbs appeared phenotypically normal regardless of treatment condition (Fig. S15A–D, Tables S3 and S4). Animals treated with DIS or RAA alone showed either no phenotype or minor skeletal abnormalities from both proximally and distally amputated limbs, but nothing that appeared to affect PD patterning (Fig. S15A, B, Tables S3 and S4). In distally amputated limbs treated with 1 µM TAL and 0.1 µM DIS, all limbs were duplicated at the radius/ulna level (Fig. S15C, Table S3). Similarly, 80% of the limbs treated with 1 µM TAL and 1 µM DIS showed either half duplication of the radius/ulna or no duplication (Table S3). These results show that DIS inhibits full proximalization of TAL-treated DBs, indicating that RA synthesis is required for proximalization. We next administered 1 µM TAL and either 0.1 µM or 1 µM RAA to animals with proximal and distal amputations. None of the distally amputated limbs treated with 1 µM TAL and 0.1 µM RAA showed duplications (Fig. S15D, Table S4), and 83.3% of those treated with 1 µM TAL and 1 µM RAA (Table S4) failed to duplicate. This shows RA signaling through RARs is necessary for limb duplication.

CYP26 inhibition transcriptionally reprograms DBs into a more PB-like identity

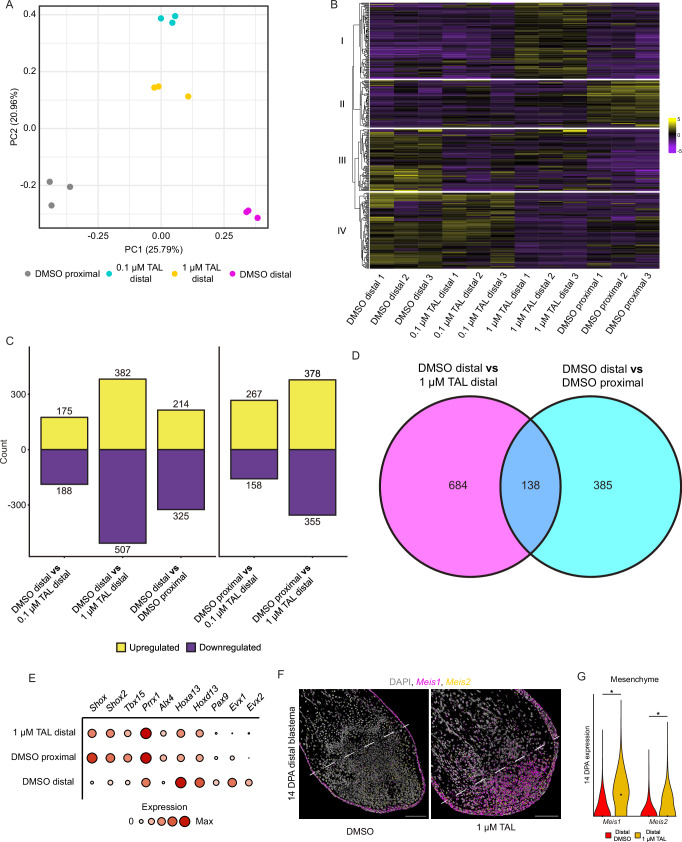

We next hypothesized that increasing TAL concentration in DBs would progressively reprogram DBs into a more PB-like identity. Additionally, we hypothesized that reprogramming would be driven by RA-responsive genes that are differentially expressed along the PD axis. We tested these hypotheses using bulk RNA-seq on DBs treated with DMSO, 0.1 µM TAL, 1 µM TAL, and PBs treated with DMSO at 14 DPA. Principal component analysis (PCA) showed segregation between treatment groups including PBs and DBs treated with DMSO (Fig. 4A). DBs treated with 0.1 or 1 µM TAL were more transcriptionally similar to each other compared to either DMSO treated PBs or DBs (Fig. 4A, Fig. S14A). TAL-treated DBs exhibited transcriptomes more akin to DMSO treated PBs, suggesting a shift towards a more PB-like positional identity (Fig. 4A, Fig. S16A–N). However, the transition from DB to PB is likely incomplete, impacting gene expression beyond just positional information.

Fig. 4. CYP26 inhibition reprograms DBs into a more PB-like identity.

A PCA of bulk transcriptomes from DBs treated with DMSO, 0.1, or 1 µM TAL and PBs treated with DMSO. B Heatmap of the top 371 (padj <0.01, FC = 1.5) genes expressed in each sample type. Cluster numbers are next to the dendrogram. C Bar graphs of significantly upregulated and downregulated genes (padj <0.1) within each comparison. D Venn diagram of overlapping DEGs (padj <0.1) from DMSO treated DBs vs DMSO treated PBs and DMSO treated DBs vs 1 µM TAL treated DBs. Full gene lists are located in the source data file. E Selected shared DEGs from (D). F HCR-FISH for Meis1 and Meis2 in DBs administered DMSO or 1 µM TAL at 14 DPA. Dashed line indicates amputation plane. Scale bars = 200 µm. G Dot quantification for mesenchymal Meis1 and Meis2 in DBs treated with DMSO or 1 µM TAL at 14 DPA (3.5 cm (HT) animals aged 2.5 months). Axes and analyses as in Fig. 1E. * = p < 0.05. Sample size and exact p-values are located within the source data file. Source data are provided as a source data file.

We classified these transcriptional differences using hierarchical clustering of the top 371 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) (padj <0.01, FC > 1.5) and observed four clusters (Fig. 4B). In cluster one, we observed RA-responsive genes upregulated by 1 µM TAL, including Cyp26a1, Krt15, and Acan which are known to be upregulated in response to RA (Fig. 4B)22,39. Considering these genes were not differentially expressed in PBs and DBs, it is unlikely that they play a role in PD positional identity. Cluster two consisted of genes highly expressed in DMSO-treated PBs, some of which increased in TAL treated DBs concentrations, while cluster three included genes highly expressed in DMSO-treated DBs. TAL treatment generally decreased cluster three gene expression, with the lowest levels in DMSO-treated PBs (Fig. 4B). Cluster four represents a transitional phase between DBs treated with 0.1 µM and 1 µM TAL, containing genes that are highly expressed in DBs treated with DMSO and 0.1 µM TAL but lowly expressed in DBs treated with 1 µM TAL and PBs treated with DMSO (Fig. 4B). The number of DEGs relative to DMSO treated DBs increases from 363 to 889 (padj <0.1) as TAL concentration rises from 0.1 or 1 µM, respectively (Fig. 4C). In comparison, DMSO treated PBs contained 539 DEGs (padj <0.1) relative to DMSO treated DBs (Fig. 4C). The number of DEGs between DMSO treated DBs and 1 µM TAL treated DBs was higher than between DMSO treated DBs and PBs, likely reflecting RA-responsive genes from cluster one not involved in PD patterning. DMSO treated PBs had 425 and 733 DEGs (padj <0.1) compared to 0.1 or 1 µM TAL treated DBs, showing that while TAL treated DBs adopted a more PB-like identity, differences remained (Fig. 4C).

Comparisons between DMSO treated DBs and either DMSO treated PBs or 1 µM TAL treated DBs enabled identification of RA-responsive genes associated with proximal or distal limb identity. We found that 138 DEGs (FDR < 0.1) were shared between both comparisons (Fig. 4D). Among these genes, we identified several that have known roles in patterning the developing or regenerating limb, including Pax940, Evx141, and Alx442 (Fig. 4E). Notably absent were Meis1, Meis2, and Cyp26b1 despite our previous results (Figs. 1–2) and their known roles as RA-responsive genes involved in PD patterning18,22,39,43. We suspect these genes were absent from our RNAseq analysis due to equally high levels in the wound epithelium of PBs and DBs (Figs. S2D, J and S12D). However, we observed significantly different expression levels of mesenchymal Cyp26b1, Meis1, and Meis2 in DBs treated with 1 µM TAL compared to DMSO treated DBs at 14 DPA (Figs. 3E, F and 4F–G, Fig. S16O), indicating that these genes are both involved in patterning and responsive to TAL treatment. Together, our results show that TAL treatment induces DBs to adopt a more proximal positional identity, likely mediated by RA-responsive patterning genes differentially expressed between PBs and DBs.

Shox is a downstream target of RA involved in stylopod and zeugopod patterning

Among RA-responsive genes that were differentially expressed between PBs and DBs were Shox and Shox2 (Fig. 4E). Shortened limbs are frequently observed in humans with Shox haploinsufficiency, which is commonly linked to idiopathic short stature, Turner syndrome, and Leri-Weill dyschondrosteosis44,45. While mice lack a functional Shox ortholog, Shox2 mutant mice develop with shortened humeri46. In the axolotl, SHOX and SHOX2 share 73.98% sequence similarity and contain a 100% identical homeodomain (Fig. S17A). Shox and Shox2 have previously been noted for their potential role in proximal positional identity during axolotl limb regeneration43, and were more epigenetically accessible in uninjured connective tissue (CT) cells of the stylopod compared to those of the autopod10. These findings suggest that Shox and Shox2 are involved in maintaining and reestablishing proximal limb positional information during limb regeneration.

To explore the role of Shox and Shox2 in patterning the PD axis, we visualized Shox and Shox2 expression in developing limb buds from stage 44-47 (Fig. 5A, Fig. S18). During limb development, we observed high levels of Shox throughout the mesenchyme of stage 44 limb buds with Shox2 localized to the posterior mesenchyme. At stage 47, Shox2 expression remained in the posterior limb mesenchyme but was proximally biased (Fig. 5A). Shox was exclusively expressed in the proximal mesenchyme of the stage 47 limb bud, leaving a Hoxa13+ zone of distal mesenchymal cells devoid of Shox expression (Fig. 5A). These results suggest that Shox is involved in establishing proximal limb identity during limb development.

Fig. 5. Shox and Shox2 mark proximal and posterior positional identity.

A Whole mount HCR-FISH for Shox, Shox2, and Hoxa13 in stage 44-47 developing limb buds. The images represent a single, 2D z-plane within a 3D image stack. Scale bars = 50 µm. B, C qRT-PCR of Shox and Shox2 in DMSO or 1 µM TAL treated DBs (3.5 cm (HT) animals aged 2.5 months, 10 DPA). Each gene was normalized to Ef1a and the groups were analyzed using a two-tailed t-test. Boxplot as in Fig. 1B, C. * = p < 0.05. D, E qRT-PCR of Shox (D) and Shox2 (E) at different PD amputation locations (3.5 cm (HT) animals aged 2.5 months, 10 DPA). Boxplot and analyses as in Fig. 1B, C. * = p < 0.05, *** = p < 0.001. F HCR-FISH for Shox and Shox2 in PBs and DBs at 10 and 14 DPA. Dashed lines indicate amputation plane. Scale bars = 200 µm. G Dot quantification for mesenchymal Shox and Shox2 in PBs and DBs at 10 and 14 DPA (3.5 cm (HT) animals aged 2.5 months). Axes and analyses as in Fig. 1E. * = p < 0.05, ** = p < 0.01. H PD intensity plots for mesenchymal Shox, Shox2, Meis1, and Hoxa13 in PBs and DBs at 10 and 14 DPA. Shaded region represents 99% confidence interval. Axes and analyses as in Fig. 1F. I, J HCR-FISH for Meis1, Shox2, and Shox (I) or Shox, Shox2, and Hoxa13 (J) in a PB at 14 DPA. Dashed line indicates amputation plane. Scale bars = 200 µm. K UMAP of Shox+ and Hoxa13+ cells in blastemas at 7, 14, and 22 DPA from reanalyzed scRNA-seq dataset32. Sample size and exact p-values are located within the source data file. Source data are provided as a source data file.

We next examined Shox and Shox2 expression following limb amputation. In agreement with our RNA-seq results, Shox and Shox2 expression increased in DBs upon 1 µM TAL treatment and were more highly expressed in US amputations compared to autopod amputations (Fig. 5B–E). Shox expression appeared to decrease incrementally in more distal amputations whereas Shox2 was expressed at the same level in LS blastemas and autopod blastemas (Fig. 5D, E). We also observed that while Shox2 expression in PBs treated with 1 µM TAL was identical to DMSO treated PBs, Shox expression was significantly lower in PBs treated with 1 µM TAL compared to control PBs (Fig. S17B, C). These results suggest that Shox is more sensitive to heightened RA levels observed in PBs treated with 1 µM TAL than Shox2. Furthermore, Shox and Shox2 were primarily expressed in mesenchymal cells with little expression in any other cell type (Fig. S17D, E). As in limb development, Shox2 expression in PBs and DBs at 7, 10, or 14 DPA was localized proximally and posteriorly in mesenchymal cells (Fig. 5F–H, Figs. S17F and S19). Shox2 expression levels in PBs and DBs at 10 DPA were similar, but by 14 DPA Shox2 was significantly more highly expressed in the proximal and posterior mesenchyme of PBs (Fig. 5F, G). This may indicate that Shox2 has a role in patterning both the PD and AP axis during limb development and regeneration. Shox was lowly expressed in the mesenchyme of PBs and DBs at 7 DPA (Fig. S17F). By 10 DPA, Shox expression was located throughout the mesenchyme of PBs and was significantly more highly expressed than in DBs (Fig. 5F–H). The limited areas of Shox expression in DBs at 10 and 14 DPA seemed to be associated with the uninjured skeletal elements (Fig. 5F). At 14 DPA, Shox remained significantly more highly expressed in PBs but was restricted to the Meis1+ proximal mesenchyme, leaving a distal subset of Hoxa13+ cells devoid of Shox expression (Fig. 5F–J, Fig. S17G, H). Shox+ and Hoxa13+ cells appeared mutually exclusive (Fig. 5J, K), suggesting that Shox is uninvolved in autopod formation.

The spatiotemporal expression patterns of Shox, Meis1, and Hoxa13 (Fig. 5H–K) suggest that Shox is activated by Meis1 and repressed by Hoxa13. Given that Meis1 is RA-responsive (Fig. 4F, G), this overlap in expression may indicate that mesenchymal Shox is activated by RA via Meis1. Indeed, the Shox promoter contains several putative Meis1 binding sites (Table S5). Conversely, Hoxa13 is repressed by RA (Figs. 3G and 4E), suggesting that Hoxa13 is involved in creating the distal limit for Shox.

Shox is required for stylopodial and zeugopodial endochondral ossification

Our gene expression results led us to hypothesize that Shox has a role in establishing both stylopod and zeugopod, but not autopod, positional identity during both limb development and regeneration. To test this hypothesis, we utilized CRISPR/Cas9 to genetically inactivate Shox. We targeted Shox with two sgRNAs specifically designed against exons 1 and 2 and simultaneously injected these sgRNAs into axolotl embryos to create mosaic F0 Shox knockout animals (Shox crispants) (Fig. 6A). NGS genotyping analyses of 10 Shox crispants indicated that both targeted loci were highly mutated, ranging from 75.15 to 97.62% of all sequenced alleles being mutated across each animal (Fig. S20A–D). Furthermore, these animals developed to adulthood, enabling us to examine the role of Shox during limb development and regeneration. Shox crispants developed significantly smaller limbs than controls with significantly smaller stylopods and zeugopods (Fig. 6B, C). Interestingly, autopod length was unaffected in Shox crispants compared to controls (Fig. 6C), showing that Shox is critical for stylopod and zeugopod development but dispensable for autopod development. To confirm this finding, we generated F1 homozygous Shox knockout axolotls (Shox−/− animals) by crossing two Shox crispants. Like the F0 crispants, Shox−/− animals exhibited shortened stylopodial and zeugopodial elements, while their autopods appeared relatively unaffected (Fig. S20E). This indicates that despite mosaicism, F0 crispants display the same limb phenotype as F1 Shox−/− animals. A similar phenotype was observed in the limbs of Shox2 knockout mice, where chondrocytes in shortened stylopods and zeugopods failed to proliferate and mature, preventing endochondral ossification46.

Fig. 6. Shox crispants show defects in endochondral ossification of proximal limb skeletal elements.

A Schematic of the Shox genomic landscape. Introns reduced 50X for visibility. Scale bar = 100 bp. B Brightfield images of control and Shox crispant limbs (3.5 cm (HT) animals aged 2.5 months). Scale bar = 1 mm. C Skeletal element quantification in control and Shox crispant limbs (7.5 cm (HT) animals aged 6 months). Differences between control and Shox crispants were analyzed using a two-tailed t-test. Boxplot as in Fig. 1B, C. n.s. = no statistical difference, ** = p < 0.01, *** = p < 0.001. D Alcian blue and alizarin red stain of adult control and Shox crispant limbs (12 cm (HT) animals aged 10 months). Scale bar = 2 mm. E H&E&A of whole stylopods, proximal epiphyses, and digits from controls and Shox crispants (8 cm (HT) animals aged 7 months). RZ = resting zone, PZ = proliferative zone. Stylopod scale bar = 1 mm. Digit scale bar = 0.5 mm. F HCR-FISH for Shox and Sox9 in a whole mount stage 46 developing limb. Scale bar = 50 µm. Sample size and exact p-values are located within the source data file. Source data are provided as a source data file.

We observed that while skeletal elements in adult control stylopods and zeugopods were partially calcified, those from Shox crispants appeared to lack calcification (Fig. 6D). Additionally, chondrocytes from control stylopods demonstrated clear progression from proliferation to hypertrophy before calcifying (Fig. 6E). In contrast, chondrocytes from Shox crispants failed to proliferate, appearing to remain as reserve cartilage through adulthood (Fig. 6E). Considering autopod size was not impacted in Shox crispant limbs, we next examined the digits of Shox crispants limbs to determine if endochondral ossification in autopodial elements was disrupted. Chondrocytes from both control and Shox crispant digits underwent phenotypically normal endochondral ossification, suggesting that while essential for more proximal limb segments, Shox is not required for autopodial skeletal maturation (Fig. 6E). This indicates that proximal and distal skeletal elements of the limb have distinct transcriptional programs responsible for endochondral ossification. Collectively, our data indicate that Shox is required for chondrocyte maturation within proximal skeletal elements. During limb development, however, many Shox+ cells are Sox9-, suggesting that Shox may also be involved in patterning non-chondrogenic mesenchymal cells (Fig. 6F, Fig. S20F).

Shox is not required for limb regeneration but is essential for proximal limb patterning

Finally, we found that Shox was dispensable for limb regeneration, as Shox crispants successfully regenerated limbs and progressed though typical stages, including blastema and palette formation, without obvious abnormalities (Fig. 7A). Shox crispant limbs remained shortened after fully regenerating, suggesting that Shox is dispensable for limb regeneration but crucial for patterning the regenerating stylopodial and zeugopodial segments (Fig. 7A). This finding was also confirmed in Shox−/− animals, which regenerated similarly sized autopods as controls but significantly smaller stylopods and zeugopods (Fig. S21). We further observed that while many Shox+ cells in PBs at 21 DPA were Sox9+, many other Shox+ cells were Prrx1+ and Sox9- (Fig. 7B, C). Additionally, Sox9 was expressed in the presumptive digits of DBs at 21 DPA (Fig. 7C, Fig. S22), indicating that Shox is not required to activate Sox9 expression. Together, these results both suggest that chondrocyte formation is independent of Shox and that Shox has an additional role in patterning non-chondrogenic mesenchymal cells during limb regeneration.

Fig. 7. Shox is dispensable for limb regeneration but required for PD patterning.

A Regeneration time course of PBs and DBs in Shox crispants. Scale bar = 1 mm. B UMAP of Shox+ and Sox9+ cells in blastemas at 7, 14, and 22 DPA from reanalyzed scRNA-seq dataset32. C HCR-FISH for Shox and Sox9 in a control PB and DB at 21 DPA. Dashed line indicates amputation plane. Scale bars = 200 µm. D HCR-FISH for Meis1, Shox2, and Hoxa13 in control and Shox−/− PBs and DBs at 14 DPA. Dashed lines indicate amputation plane. Scale bars = 200 µm. E–H qRT-PCR of Meis1 (E), Hoxa13 (F), Shox2 (G), and Cyp26b1 (H) in control and Shox−/− PBs and DBs (2.5 cm or 3.2 cm (HT, Shox−/− and controls, respectively) animals aged 2.5 months, 14 DPA). Boxplots and analyses as in Fig. 1B, C. * = p < 0.05, ** = p < 0.01, *** = p < 0.001. I Brightfield images of regenerates and skeletal structures of control or Shox crispant limbs treated with 1 µm TAL. Dashed lines indicate amputation plane. Scale bar = 2 mm. Sample size and exact p-values are located within the source data file. Source data are provided as a source data file.

We next assessed Meis1 and Hoxa13 expression in Shox−/− PBs and DBs and found their spatial expression patterns unchanged compared to controls (Fig. 7D, Fig. S22), consistent with findings from Shox2 KO mice46. Correspondingly, the relative expression of these genes in Shox−/− PBs and DBs was unchanged from controls (Fig. 7E, F). These results suggest that PD positional identity is unaffected by the absence of Shox. Furthermore, while Shox2 was expressed in the posterior mesenchyme of both control and Shox−/− DBs, it was generally more lowly expressed in Shox−/− DBs (Fig. 7D, G). In contrast, Shox2 expression expanded into the anterior mesenchyme of Shox−/− PBs, though its levels remained unchanged compared to controls (Fig. 7D, G). This suggests that Shox2 compensates for the loss of Shox in Shox−/− PBs.

The observations that Hoxa13 and Meis1 expression are unaffected by Shox knockout (Fig. 7D–F), along with Meis1 and Shox colocalization (Fig. 5H, I), suggest that Shox acts downstream of Meis1 to regulate endochondral ossification of proximal skeletal elements. Considering Meis1 is RA-responsive and limb-specific Meis KO mice lack proximal skeletal elements14, RA likely directs proximal endochondral ossification through Shox via Meis1. Consistent with this, Cyp26b1 was significantly more highly expressed in Shox−/− DBs than Shox−/− PBs (Fig. 7H). In addition, Cyp26b1 expression levels did not vary between control DBs and Shox−/− DBs, as well as between control PBs and Shox−/− PBs (Fig. 7H). These observations suggest both that Shox does not determine RA concentration in the blastema and physiological levels of RA are similar in regenerating control and Shox−/− limbs. Further, Shox crispant DBs treated with 1 µM TAL regenerate with shortened duplicated proximal elements (Fig. 7I), showing that Shox crispant limbs respond to RA but cannot properly pattern proximal elements.

Discussion

Our study shows that regulation of endogenous RA levels is required for PD limb patterning during regeneration. We propose that Cyp26b1-mediated RA breakdown, not RA synthesis or RAR expression, determines PD positional identity by setting the RA signaling levels in the blastema, activating or repressing RA signaling (Fig. 8). Moreover, CT cells in the uninjured limb have inherent, epigenetically encoded positional identity10. Upon amputation, these cells dedifferentiate into a limb bud-like state while retaining their PD positional memory2. We propose that dedifferentiated blastema cells modify Cyp26b1 expression depending on their positional memory, which adjusts RA signaling levels to the appropriate PD location and regulates genes that convey PD positional identity. Elevated RA levels in PBs activate Shox, promoting endochondral ossification in proximal skeletal elements. In contrast, reduced RA levels in DBs leads to a Shox-independent mechanism for endochondral ossification of distal skeletal elements. Our results show that RA signaling levels exert segment-specific effects during skeleton regeneration (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8. Model for PD patterning during limb regeneration.

Proposed model for how PD patterning occurs during axolotl limb regeneration.

The model that we propose explains how positional identity is determined among cells at two spatial scales: the entire limb PD axis and PD axes within different limb segments. Cyp26b1 expression was graded across the limb PD axis, with similar levels of expression observed between blastemas that formed from different, but spatially juxtaposed limb segments (e.g., LS and UZ blastemas). However, within limb segments, Cyp26b1 expression differed considerably between blastemas that formed from spatially disparate locations (e.g., US and LS blastemas). Our model suggests that positional identity is conveyed in a segment specific manner, as Shox expression is mutually exclusive from Hoxa13 and Shox perturbation affects only stylopodial and zeugopodial skeletal elements. Further evidence for this comes from Hoxa13 knockout newts that fail to regenerate autopods8. This may imply that each limb segment requires a specific threshold of positional values determined by RA signaling levels, as posited by the French Flag model5. Once this threshold is met, blastema cells can create intra-segmental positional values based on RA signaling levels, enabling fine-tuning of limb segment morphology. It may also explain why half-segment duplications are observed following treatment with lower concentrations of TAL or RA during limb regeneration29,30.

While our model specifically focuses on RA degradation in PBs and DBs, it does not address RA synthesis along the regenerating PD axis. Our results present two possibilities: (1) heightened levels of RA synthesis at more proximal amputations and (2) identical levels of RA synthesis at any amputation level that is fine-tuned at each amputation location by RA degradation. Regarding the former, our qRT-PCR analysis revealed that Raldh3 expression was significantly higher in proximal amputations compared to distal amputations, suggesting that elevated RA levels in PBs are generated primarily through Raldh3 rather than Raldh1 or Raldh2. However, this finding was inconsistent with our FISH and RNAseq results, which showed no differences in expression of Raldh1, Raldh2, and Raldh3 between PBs and DBs. Furthermore, inhibiting RA synthesis in PBs and DBs caused skeletal abnormalities in the final regenerate at each amputation location. These results are more consistent with the possibility that RA synthesis is uniform along the PD axis. Nevertheless, our results do not exclude either scenario, and future studies are needed to ascertain RA synthesis levels along the PD axis. An outstanding question related to this is why RA would be synthesized in the regenerating limb only to be degraded depending on amputation location. While our work does not address this complexity directly, we speculate that RA has several roles during limb regeneration outside of providing proximal limb positional identity. RA is important for directing nerves to their targets, including epithelial and neuromuscular junctions47. Furthermore, RA plays an essential role in replenishing epithelial cells during physiological growth48, which may contribute to the scarless wound healing following injuries in salamanders49.

Further studies are needed to identify upstream activators of Cyp26b1 during amphibian limb regeneration. We observed that Cyp26b1 exhibited a similar spatiotemporal expression pattern as Hoxa11 and Hoxa13, providing circumstantial evidence that 5’ Hox genes regulate Cyp26b1 expression. Previous studies on mouse limb development have suggested that AER-derived FGFs activate Cyp26b1 instead of 5’ Hox genes to create a domain of distal identity while simultaneously interacting with SHH to promote distal outgrowth17. Indeed, Fgf8 expression in Cyp26b1−/− limbs does not appear to be impacted by the loss of CYP26B1 function18. However, this may differ during limb regeneration as the SHH-FGF feedback loop is required for blastema distal outgrowth and proliferation50, and neither Fgf8 nor Shh were differentially expressed between PBs and DBs in our RNA-seq. For these reasons, it seems more likely that Cyp26b1 is regulated by 5’ Hox genes including Hoxa11 and Hoxa13 during limb regeneration.

How a cell conveys its PD positional identity to neighboring cells in response to RA to coordinate patterning in the blastema remains an unanswered question in the field. Several lines of evidence suggest that differences in adhesivity and cell adhesion molecules (CAMs) differentiate PBs from DBs51. These differences in adhesivity can be modified by RA, suggesting that RA signaling levels are important for generating a gradient of adhesive properties in PBs and DBs52,53. In agreement with these studies, two CAMs, TIG1 and PROD1, have previously been identified that are RA-responsive and modify adhesivity during limb regeneration38,54. Neither of these CAMs appeared to be RA-responsive or differentially expressed in PBs and DBs, despite their importance in directing cell adhesivity during limb regeneration. However, our RNAseq represents only a small portion of gene expression during the entire duration of limb regeneration. Indeed, Tig1 expression appears strongest at earlier timepoints, which may explain its absence from our dataset38. Nonetheless, our RNA-seq dataset should serve as a helpful resource for identifying other RA-responsive CAMs that are differentially expressed in PBs and DBs.

Methods

Animal procedures & drug treatments

Transgenic lines (RA reporter- tgSceI(RARE:GFP)Pmx, Hoxa13 reporter- tm(Hoxa13t/+:Hoxa13-T2A-mCHERRY)Etnka) used in this study were bred at Northeastern University. d/d genotype axolotls (RRID:AGSC 101E; RRID:AGSC101L) were bred at Northeastern University or were obtained from the Ambystoma Genetic Stock Center (RRID: SCR_006372). Crispant lines were generated at both Northeastern University and the University of Kentucky. An equal distribution of males and females were used in this study. All surgeries were performed under anesthesia using 0.01% benzocaine and were approved by the Northeastern University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Talarozole and AGN 193109 were resuspended in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) to 5 mM and stored at −20 °C. Disulfiram was resuspended in DMSO to 20 mM and stored at −20 °C. Animals received amputations through the carpals on one limb and through the upper humerus on the contralateral limb. Four days post amputation (DPA), animals were placed in drug or DMSO. Animals were redosed every other day for 7 days. Following treatment, animals were removed from the drug water and placed into axolotl housing water. Regenerated limbs were collected from the animals 120 days post treatment for analysis of skeletal morphology.

qRT-PCR

Blastema tissue (4–5 blastemas per sample, 3–6 samples per experiment) was collected from 3.5 cm animals head to tail (HT) aged 2.5 months and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen. RNA isolation and qRT-PCR were performed with standard protocols, using 1 ng of cDNA per reaction. Each qRT-PCR reaction was run in duplicate. Primers for each gene are listed in Table S1. Gene expression was normalized to Ef1α and the Livak 2−ΔΔCq method was used to quantify relative fold change in mRNA abundance. Statistical significance between groups was tested using either a two-tailed Student’s t-test or a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with post-hoc Tukey’s honestly significant difference (HSD) test on ΔCt values. Linear regression analysis was performed to test for linear relationships across samples.

Single-cell gene expression quantification and reanalysis

Existing single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) data from proximally amputated forelimbs was accessed from NCBI SRA PRJNA58948432. UMI counts for gene expression data were generated using kallisto55 and bustools56 against Ambystoma mexicanum transcriptome v4.757. Isoform-level count matrices were generated using “bustools count” with the --em flag. Counts matrices were imported into Seurat v558 in an RStudio IDE. Cells expressing fewer than 200 features and features expressed in fewer than 3 cells were filtered out; matrices were further filtered to include cells with between 500 and 25,000 counts, <5% red blood cell gene content, and <15% mitochondrial gene content. Counts were normalized using the SCTransform function with regression for mitochondrial content and red blood cell content. The counts layers were flattened with the IntegrateLayers function using RPCAIntegration, after which FindClusters was run with a resolution of 0.4 followed by RunUMAP using the first 30 dimensions, 50 nearest neighbors, and a minimum distance of 0.1. Following cluster annotation, SCTransform-normalized isoform-level expression for genes of interest was summed and log-transformed for plotting with ggplot2 using UMAP coordinates from Seurat59.

HCR-FISH and imaging

Whole mount and tissue section version 3 hybridization chain reaction fluorescence in-situ hybridization (HCR-FISH) protocols were performed as previously described60 with slight modifications on the tissue section protocol. Namely, fresh frozen blastema tissue from 3.5 cm animals (HT) aged 2.5 months were sectioned at 10 µm. Slides were then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 15 min at room temperature and washed with 1X phosphate buffered saline (PBS) three times for 5 min at room temperature before being stored in 70% ethanol at 4 °C until use. Slides were washed again three times for 5 min with 1X PBS at room temperature before beginning HCR-FISH protocol. Probes for each gene were generated using ProbeGenerator (http://ec2-44-211-232-78.compute-1.amazonaws.com) and can be found in the source data file.

All tissue sections were imaged using a Zeiss LSM 880 confocal microscope at 20X magnification with airyscan fast settings. For each image, 4–6 optical sections were captured in the 10 µm tissue section. Following acquisition, images were processed on Zen Black using airyscan processing with the automatic 2D setting, then a maximum intensity projection step was performed. If obvious issues in tile alignment were observed, an additional stitching step was performed prior to maximum intensity projection.

Whole mount samples stained using HCR-FISH were mounted in 1.5% low-melt agarose and refractive index matched with EasyIndex (LifeCanvas Technologies) overnight at 4 °C60. Samples were then imaged in EasyIndex using a Zeiss Lightsheet Z1 at 20X magnification. All representative images are a single z-plane from the stack.

HCR-FISH dot visualization and quantification

Dot detection in HCR-FISH images was performed using RS FISH61. For visualization of HCR-FISH dots in figure pictures, RS-FISH dots were flattened atop the DAPI channel and background dots outside tissue sections were removed. For quantification, identified dots from RS-FISH were overlaid on a black background and the image was flattened. The ImageJ function “Find Maxima” with prominence greater than 0 was used to convert dots to single pixels. Cell outlines were obtained using Cellpose segmentation run on the DAPI channel using the “cyto2” model with default settings and a diameter of 6062. A modified version of the region of interest conversion script provided by the Cellpose authors was used to obtain measurements of area and raw integrated density per cell. Pipeline documentation can be accessed at https://github.com/Monaghan-Lab/HCRFISH-DotCounting.

All measurements were concatenated and filtered for cells with an area greater than 60, as smaller areas can indicate poor segmentation or cells at a nonoptimal plane. To evaluate the expression levels for each gene between groups, two-tailed clustered Wilcoxon rank-sum tests (n = 2–6 blastemas, sample size for each group located within the source data file) were performed with FDR p-adjustment using the R package “clusrank” with test method “ds”63. Violin plots were generated in RStudio using the ggplot2 package59.

HCR-FISH PD intensity measurements

Images of RS-FISH maxima were rotated with no interpolation such that the top of the image represented the most proximal end of the blastema. An equal rotation was performed on the DAPI channel from the same tissue. The freehand selection tool was used to isolate the blastemal mesenchyme from the DAPI image, then this selection was overlaid onto the rotated maxima image and used to clear any points lying outside of the selection before adding a value of 25 to each pixel within the blastema selection. The value z at every (x,y) pixel in the image was then measured.

Measurements for each image were imported into R and filtered for z > 0 to select for points falling only within the blastemal mesenchyme. The y values were then rescaled to generate a pseudo-proximodistal axis with range [0, 1]. Z values were reassigned such that 25 represented a 0 or “negative” pixel and 255 represented a 1 or “positive” pixel, then grouped at each pseudo-y value and averaged to yield a proportion of positive pixels. The square root of these proportions was plotted as a smoothed curve along the pseudo-proximodistal axis using the “stat_smooth()” function in ggplot2 with an n of 200059. A sample script can be accessed at https://github.com/Monaghan-Lab/HCRFISH-DotCounting.

Alcian blue/alizarin red staining

Whole mount alcian blue/alizarin red staining was performed using a modified version of a previously published protocol64. Briefly, regenerated limbs were collected and immediately fixed in 4% PFA overnight at 4 °C. The next day, limbs were washed three times for 5 min each with 1X PBS at room temperature and skinned. Limbs were dehydrated in 25%, 50%, and 100% ethanol for 20 min at each concentration before being placed in alcian blue mixture (5 mg alcian blue in 30 mL 100% ethanol, 20 mL acetic acid) and left on a rocker overnight at room temperature. The next day, limbs were rehydrated in 100%, 50%, and 25% ethanol for 20 min at room temperature at each concentration. Limbs were placed into trypsin solution (1% trypsin in 30% borax) and rocked for 45 min at room temperature. Samples were washed twice in 1% KOH for 30 min each before being placed in alizarin red mixture (5 mg alizarin red in 50 mL 1% KOH) and rocked overnight at room temperature. Limbs were again washed twice with 1% KOH for 30 min at room temperature and placed in 25% glycerol/1% KOH solution until samples cleared. The limbs were then dehydrated in 25%, 50%, and 100% ethanol for 20 min at room temperature at each concentration. Finally, limbs were placed in 25%, 50%, and 75% glycerol solutions (made in 100% ethanol) before being stored in 100% glycerol for imaging.

Bulk RNA sequencing and analysis

Animals received a proximal amputation through the upper humerus of the left forelimb and a distal amputation through the carpals of the right forelimb. TAL was administered in the housing water as indicated above. Samples (n = 3 samples per condition, 2-3 blastemas per sample, 5 cm (HT) animals aged 3 months) were collected at 14 DPA and immediately flash frozen in liquid nitrogen before storing at −80 °C. Samples were shipped to Genewiz for RNA sequencing using an Illumina HiSeq platform and 150-bp paired-end reads for an average sequencing depth of roughly 24.1 million reads per sample. Raw sequencing data are available at GEO (accession number GSE272731).

Reads were quality trimmed before quasi-mapping to the v.47 axolotl transcriptome65 and quantification. Differential expression analysis was performed on counts matrices with DESeq2 v1.34.066 using the Trinity v2.8.5 script67 “run_DE_analysis.pl” with default parameters. Visualizations were produced with ggplot2, ggvenn, and ComplexHeatmap68 where appropriate. Sample correlation heatmap was produced using Trinity script “PtR” on the gene counts matrix67.

Shox promoter analysis

The first 20 Kb upstream the Shox transcriptional start site were analyzed for Meis1 binding sites using the web-based platform https://molotool.autosome.org.

Generating and genotyping Shox crispant axolotls

Shox crispants were generated using CRISPR/Cas9 according to previous protocols69. The following sgRNAs were used:

Shox sgRNA 2—GAGGGAGGACGTGAAGTCGG

Shox sgRNA 3—GGCCAGGGCCCGGGAGCTGG

NGS-based genotyping was conducted on a pool of 10 tail tips from crispant animals and analyzed using CRISPResso270.

Hematoxylin, eosin, and alcian blue staining

Samples for hematoxylin, eosin, and alcian blue staining (H&E&A) were collected and placed in 4% PFA overnight at 4 °C. Samples were then washed with 1X PBS three times for 5 min each. Following the third wash, samples were placed in 1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) for four days at 4 °C. The EDTA solution was changed every other day. After EDTA treatment, the samples were again washed with 1X PBS three times for 5 min each before being cryoprotected in 30% sucrose. Once the samples sunk in the 30% sucrose, the samples were mounted in optimal cutting temperature medium and frozen at −80 °C until use. These blocks were then sectioned at 10 µm, and the resultant slides were baked at 65 °C overnight. To improve the adherence of the skeletal structure to the slide, slides were placed in 4% PFA for 15 min at room temperature. Slides were washed three times for 5 min with 1X PBS, then the slides were placed in alcian blue solution (5 mg of alcian blue in 30 mL 100% ethanol and 20 mL acetic acid) for 10 min at room temperature. The slides were then dehydrated with 100% EtOH for 1 min at room temperature and allowed to air dry. Hematoxylin solution was added to the slides and incubated at room temperature for 7 min. Slides were then dipped into tap water five times, then clean tap water another 15 times. Slides were dipped another 15 times in clean tap water before adding bluing buffer for 2 min at room temperature. Slides were again dipped in clean tap water five times, and eosin solution was pipetted onto the slides for 2 min at room temperature. Residual eosin was removed by dipping slides ten times in clean tap water, and the slides were air dried before imaging.

Statistics and reproducibility

Animals for each experiment were randomly selected. Sample size for each experiment is indicated in source data file. No statistical method was used to predetermine sample size. Statistical analyses are indicated within the figure legends and methods, and exact p-values are indicated in the source data file. Analyses were conducted on Matlab or R. Fluorescent images not compatible with RS-FISH and qRT-PCR samples that demonstrated abnormal amplification were excluded from the analyses. Experiments were replicated at least twice, and all attempts at replication were successful. The experiments were randomized, and the investigators were blinded to allocation during experiments and outcome assessment.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Source data

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Guoxin Rong for his imaging expertise and assistance with microscopy. Additionally, we thank Prayag Murawala for providing transgenic animals and the Ambystoma Genetic Stock Center for non-transgenic animals. We thank Malcolm Maden for his critical analysis of the manuscript. We finally thank the Institute for Chemical Imaging of Living Systems at Northeastern University for consultation and imaging support. The work from this paper was funded by NIH grant R01HD099174 and by NSF grants 1558017 and 1656429, all obtained by J.R.M. Non-transgenic animals were obtained from the Ambystoma Genetic Stock Center funded through NIH grant P40-OD019794 obtained by S.R.V.

Author contributions

T.J.D and J.R.M. designed and conceived the project. S.R.V. and J.R.M. obtained funding and supervised the project. T.J.D., M.M., D.B., J.R.G., A.K.G., D.D., and S.R.V. performed experiments. T.J.D., M.M., S.K., and D.B. analyzed the data. T.J.D. and J.R.M. wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to the final draft.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Maximina Yun, who co-reviewed with Catarina Rodrigues Olivera; Mekayla Storer, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Data availability

Raw bulk RNAseq data have been deposited in the GEO database under accession code GSE272731. scRNAseq data were accessed at NCBI SRA under accession code PRJNA589484. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

All custom code generated for this manuscript were submitted to GitHub for public access. Code for HCR-FISH dot quantification and HCR-FISH PD intensity measurements can be accessed at https://github.com/Monaghan-Lab/HCRFISH-DotCounting.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-025-59497-5.

References

- 1.Currie, J. D. et al. Live imaging of axolotl digit regeneration reveals spatiotemporal choreography of diverse connective tissue progenitor pools. Dev. Cell39, 411–423 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gerber, T. et al. Single-cell analysis uncovers convergence of cell identities during axolotl limb regeneration. Science362, eaaq0681 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Kragl, M. et al. Cells keep a memory of their tissue origin during axolotl limb regeneration. Nature460, 60–65 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nacu, E. et al. Connective tissue cells, but not muscle cells, are involved in establishing the proximo-distal outcome of limb regeneration in the axolotl. Development140, 513 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wolpert, L. Positional information and the spatial pattern of cellular differentiation. J. Theor. Biol.25, 1–47 (1969). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pescitelli, M. J. Jr. & Stocum, D. L. Nonsegmental organization of positional information in regenerating Ambystoma limbs. Dev. Biol.82, 69–85 (1981). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roensch, K., Tazaki, A., Chara, O. & Tanaka, E. M. Progressive specification rather than intercalation of segments during limb regeneration. Science342, 1375–1379 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takeuchi, T. et al. Newt Hoxa13 has an essential and predominant role in digit formation during development and regeneration. Development149, dev200282 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Gardiner, D. M., Blumberg, B., Komine, Y. & Bryant, S. V. Regulation of HoxA expression in developing and regenerating axolotl limbs. Development121, 1731–1741 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kawaguchi, A. et al. A chromatin code for limb segment identity in axolotl limb regeneration. Dev Cell59, 2239–2253.e2239 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Niederreither, K., Vermot, J., Schuhbaur, B., Chambon, P. & Dolle, P. Embryonic retinoic acid synthesis is required for forelimb growth and anteroposterior patterning in the mouse. Development129, 3563–3574 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cooper, K. L. et al. Initiation of proximal-distal patterning in the vertebrate limb by signals and growth. Science332, 1083–1086 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roselló-Díez, A., Ros, M. A. & Torres, M. Diffusible signals, not autonomous mechanisms, determine the main proximodistal limb subdivision. Science332, 1086–1088 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Delgado, I. et al. Proximo-distal positional information encoded by an Fgf-regulated gradient of homeodomain transcription factors in the vertebrate limb. Sci. Adv.6, eaaz0742 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mercader, N. et al. Opposing RA and FGF signals control proximodistal vertebrate limb development through regulation of Meis genes. Development127, 3961–3970 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saiz-Lopez, P. et al. An intrinsic timer specifies distal structures of the vertebrate limb. Nat. Commun.6, 8108 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Probst, S. et al. SHH propagates distal limb bud development by enhancing CYP26B1-mediated retinoic acid clearance via AER-FGF signalling. Development138, 1913–1923 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yashiro, K. et al. Regulation of retinoic acid distribution is required for proximodistal patterning and outgrowth of the developing mouse limb. Dev. Cell6, 411–422 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Niederreither, K., Subbarayan, V., Dolle, P. & Chambon, P. Embryonic retinoic acid synthesis is essential for early mouse post-implantation development. Nat. Genet21, 444–448 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Monaghan, J. R. & Maden, M. Visualization of retinoic acid signaling in transgenic axolotls during limb development and regeneration. Dev. Biol.368, 63–75 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Scadding, S. R. & Maden, M. Comparison of the effects of vitamin A on limb development and regeneration in the axolotl, Ambystoma mexicanum. J. Embryol. Exp. Morphol.91, 19–34 (1986). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nguyen, M. et al. Retinoic acid receptor regulation of epimorphic and homeostatic regeneration in the axolotl. Development144, 601–611 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maden, M. Retinoids as endogenous components of the regenerating limb and tail. Wound Repair Regen.6, 358–365 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Viviano, C. M., Horton, C. E., Maden, M. & Brockes, J. P. Synthesis and release of 9-cis retinoic acid by the urodele wound epidermis. Development121, 3753–3762 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Scadding, S. R. & Maden, M. Retinoic Acid Gradients during Limb Regeneration. Dev. Biol.162, 608–617 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brockes, J. P. Introduction of a retinoid reporter gene into the urodele limb blastema. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA89, 11386–11390 (1992). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scadding, S. R. Citral, an inhibitor of retinoic acid synthesis, modifies pattern formation during limb regeneration in the axolotl Ambystoma mexicanum. Can. J. Zool.77, 1835–1837 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee, E., Ju, B.-G. & Kim, W.-S. Endogenous retinoic acid mediates the early events in salamander limb regeneration. Anim. Cells Syst.16, 462–468 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maden, M. Vitamin A and pattern formation in the regenerating limb. Nature295, 672–675 (1982). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thoms, S. D. & Stocum, D. L. Retinoic acid-induced pattern duplication in regenerating urodele limbs. Dev. Biol.103, 319–328 (1984). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mercader, N., Tanaka, E. M. & Torres, M. Proximodistal identity during vertebrate limb regeneration is regulated by Meis homeodomain proteins. Development132, 4131–4142 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li, H. et al. Dynamic cell transition and immune response landscapes of axolotl limb regeneration revealed by single-cell analysis. Protein Cell12, 57–66 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Roselló-Díez, A., Arques, C. G., Delgado, I., Giovinazzo, G. & Torres, M. Diffusible signals and epigenetic timing cooperate in late proximo-distal limb patterning. Development141, 1534–1543 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mercader, N. et al. Ectopic Meis1 expression in the mouse limb bud alters P-D patterning in a Pbx1-independent manner. Int J. Dev. Biol.53, 1483–1494 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Uzkudun, M., Marcon, L. & Sharpe, J. Data-driven modelling of a gene regulatory network for cell fate decisions in the growing limb bud. Mol. Syst. Biol.11, 815 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maden, M. The effect of vitamin A on the regenerating axolotl limb. J. Embryol. Exp. Morphol.77, 273–295 (1983). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cuervo, R. & Chimal-Monroy, J. Chemical activation of RARβ induces post-embryonically bilateral limb duplication during Xenopus limb regeneration. Sci. Rep.3, 1886 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Oliveira, C. R. et al. Tig1 regulates proximo-distal identity during salamander limb regeneration. Nat. Commun.13, 1141 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Polvadore, T. & Maden, M. Retinoic acid receptors and the control of positional information in the regenerating axolotl limb. Cells10, 2174 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.McGlinn, E. et al. Pax9 and Jagged1 act downstream of Gli3 in vertebrate limb development. Mech. Dev.122, 1218–1233 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Niswander, L., Jeffrey, S., Martin, G. R. & Tickle, C. A positive feedback loop coordinates growth and patterning in the vertebrate limb. Nature371, 609–612 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.te Welscher, P., Fernandez-Teran, M., Ros, M. A. & Zeller, R. Mutual genetic antagonism involving GLI3 and dHAND prepatterns the vertebrate limb bud mesenchyme prior to SHH signaling. Genes Dev.16, 421–426 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bryant, D. M. et al. A tissue-mapped axolotl de novo transcriptome enables identification of limb regeneration factors. Cell Rep.18, 762–776 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rao, E. et al. Pseudoautosomal deletions encompassing a novel homeobox gene cause growth failure in idiopathic short stature and Turner syndrome. Nat. Genet16, 54–63 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shears, D. J. et al. Mutation and deletion of the pseudoautosomal gene SHOX cause Leri-Weill dyschondrosteosis. Nat. Genet19, 70–73 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yu, L. et al. Shox2 is required for chondrocyte proliferation and maturation in proximal limb skeleton. Dev. Biol.306, 549–559 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dmetrichuk, J. M., Spencer, G. E. & Carlone, R. L. Retinoic acid-dependent attraction of adult spinal cord axons towards regenerating newt limb blastemas in vitro. Dev. Biol.281, 112–120 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zasada, M. & Budzisz, E. Retinoids: active molecules influencing skin structure formation in cosmetic and dermatological treatments. Postepy Dermatol Alergol.36, 392–397 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Seifert, A. W., Monaghan, J. R., Voss, S. R. & Maden, M. Skin regeneration in adult axolotls: a blueprint for scar-free healing in vertebrates. PLoS ONE7, e32875 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nacu, E., Gromberg, E., Oliveira, C. R., Drechsel, D. & Tanaka, E. M. FGF8 and SHH substitute for anterior-posterior tissue interactions to induce limb regeneration. Nature533, 407–410 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nardi, J. B. & Stocum, D. L. Surface properties of regenerating limb cells: evidence for gradation along the proximodistal axis. Differentiation25, 27–31 (1984). [Google Scholar]

- 52.Johnson, K. J. & Scadding, S. R. Effects of tunicamycin on retinoic acid induced respecification of positional values in regenerating limbs of the larval axolotl, Ambystoma mexicanum. Dev. Dyn.193, 185–192 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Crawford, K. & Stocum, D. L. Retinoic acid coordinately proximalizes regenerate pattern and blastema differential affinity in axolotl limbs. Development102, 687–698 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.da Silva, S. M., Gates, P. B. & Brockes, J. P. The newt ortholog of CD59 is implicated in proximodistal identity during amphibian limb regeneration. Dev. Cell3, 547–555 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bray, N. L., Pimentel, H., Melsted, P. & Pachter, L. Near-optimal probabilistic RNA-seq quantification. Nat. Biotechnol.34, 525–527 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Melsted, P., Ntranos, V. & Pachter, L. The barcode, UMI, set format and BUStools. Bioinformatics35, 4472–4473 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schloissnig, S. et al. The giant axolotl genome uncovers the evolution, scaling, and transcriptional control of complex gene loci. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci.118, e2017176118 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hao, Y. et al. Dictionary learning for integrative, multimodal and scalable single-cell analysis. Nat. Biotechnol.42, 293–304 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wickham, H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis (Springer International Publishing, 2016).

- 60.Lovely, A. M., Duerr, T. J., Stein, D. F., Mun, E. T. & Monaghan, J. R. Hybridization chain reaction fluorescence in situ hybridization (HCR-FISH) in Ambystoma mexicanum tissue. Methods Mol. Biol.2562, 109–122 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bahry, E. et al. RS-FISH: precise, interactive, fast, and scalable FISH spot detection. Nat. Methods19, 1563–1567 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Stringer, C., Wang, T., Michaelos, M. & Pachitariu, M. Cellpose: a generalist algorithm for cellular segmentation. Nat. Methods18, 100–106 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jiang, Y., Lee, M.-L. T., He, X., Rosner, B. & Yan, J. Wilcoxon rank-based tests for clustered data with R package clusrank. J. Stat. Softw.96, 1–26 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 64.Riquelme-Guzmán, C. & Sandoval-Guzmán, T. Methods for studying appendicular skeletal biology in axolotls. Methods Mol. Biol.2562, 155–163 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Nowoshilow, S. et al. The axolotl genome and the evolution of key tissue formation regulators. Nature554, 50–55 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Love, M. I., Huber, W. & Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol.15, 550 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Grabherr, M. G. et al. Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-Seq data without a reference genome. Nat. Biotechnol.29, 644–652 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gu, Z., Eils, R. & Schlesner, M. Complex heatmaps reveal patterns and correlations in multidimensional genomic data. Bioinformatics32, 2847–2849 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Trofka, A. et al. Genetic basis for an evolutionary shift from ancestral preaxial to postaxial limb polarity in non-urodele vertebrates. Curr. Biol.31, 4923–4934.e4925 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Clement, K. et al. CRISPResso2 provides accurate and rapid genome editing sequence analysis. Nat. Biotechnol.37, 224–226 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Raw bulk RNAseq data have been deposited in the GEO database under accession code GSE272731. scRNAseq data were accessed at NCBI SRA under accession code PRJNA589484. Source data are provided with this paper.

All custom code generated for this manuscript were submitted to GitHub for public access. Code for HCR-FISH dot quantification and HCR-FISH PD intensity measurements can be accessed at https://github.com/Monaghan-Lab/HCRFISH-DotCounting.