Abstract

Background

Snakebites are problematic in many developing regions, including India, where over half of global snakebite deaths occur. Antivenoms are currently the only licensed treatment for snakebites. However, their use causes several challenges, most notably geographical limitations in efficacy and adverse side effects. Therefore, therapeutic alternatives are urgently needed. Recently, several studies have evaluated small molecule inhibitors (SMIs) and highlighted their promise as safe and effective alternatives to antivenoms. We investigate their potential use against Indian snakes, particularly Russell’s viper (Daboia russelii), responsible for over half of India’s snakebite cases.

Methods

Here, we explored the effectiveness of two phase-2-approved SMIs in countering the diverse and variable toxicities of D. russelii from across India.

Results

The phospholipase inhibitor varespladib and the metalloproteinase inhibitor marimastat, individually or in combination, effectively counter the toxicities of D. russelii venoms in vitro. Specific drug efficacy varies across geographic regions. These SMIs and their combination prevent lethality caused by the pan-Indian D. russelii, even in rescue experiments where treatment is delayed, in mice.

Conclusions

Our findings support the potential use of SMIs as effective, affordable, and accessible future therapies for treating bites from the world’s most medically important snake species.

Subject terms: Clinical pharmacology, Diseases

Rudresha et al. evaluated small molecule inhibitors as early intervention therapeutics against Russell’s viper (Daboia russelii) envenoming. Varespladib and marimastat effectively neutralise the toxicities of pan-Indian Daboia russelii venom in vitro and in vivo, including with delayed treatment.

Plain Language Summary

Russell’s viper (Daboia russelii) causes over half the snakebite cases in India. Animal-derived antivenoms have some limitations so we investigated alternative snakebite treatments. We found that two repurposed drugs, which previously entered phase III clinical trials for other indications, called varespladib and marimastat, could prevent the lethal effects of D. russelii venom from various regions across India. Both drugs, used individually or in combination, effectively neutralised the venom and fully protected mice from lethal venom effects, even if administration was delayed. Our findings suggest that these drugs could be an effective alternative treatment for snakebite and reduce the impact of D. russelii across the Indian subcontinent.

Introduction

Snakebite is a medical emergency that causes an alarming number of deaths and disabilities, particularly in rural tropical communities that lack access to timely and affordable treatment1,2. Current estimates suggest that as many as 138,000 people die because of snakebites each year, with India suffering the highest burden, with an estimated 58,000 annual deaths3,4. Antivenom is the only scientifically advocated treatment for snakebite. Despite its life-saving efficacy, antivenoms exhibit several important shortcomings, including limited potency and cross-snake species efficacy, high incidences of adverse reactions, the inability to counter snakebite-induced morbidity, cost of production, and the necessity to be delivered intravenously in a clinical setting5–7. As a result, alternatives to antivenom therapies are urgently warranted.

Snake venoms vary extensively among species. They are a concoction of enzymatic and nonenzymatic components found in variable proportions but are primarily dominated by a few toxin superfamilies8. Viper venoms, for example, mainly consist of phospholipase A2 (PLA2), metalloproteinases (SVMPs) and serine proteases (SVSPs)9,10. PLA2s are multi-functional enzymes that can cause cytotoxicity, skeletal muscle damage, presynaptic neurotoxicity, inflammation, and interference with components of the blood clotting cascade to induce anticoagulant effects11–16. SVSPs also affect various physiological functions, though those mainly relate to haemostasis by perturbing blood coagulation via fibrinogenolysis and platelet aggregation17–20. SVMPs are primarily responsible for causing haemorrhage, apoptosis, cytotoxicity, and chronic tissue necrosis at the bitten site21,22 but can also interfere with coagulation through the destruction or activation of blood clotting factors, often leading to venom-induced consumptive coagulopathy (VICC) in snakebite victims23,24. Targeting such major enzymatic snake venom toxins using small molecule inhibitors (SMIs), many of which are already approved for clinical use or have previously entered clinical trials, could offer a safer and more effective alternative to antivenom treatment25–27.

Several studies have highlighted SMIs - individually or as a combination of drugs - as promising leads for neutralising snake venoms worldwide28–32. Compared to conventional antivenom, SMIs may offer several advantages, including broad-spectrum effectivity, little to no adverse reactions, greater stability, cost-effectiveness and the possibility of creating orally active formulations26,31. Furthermore, due to their smaller size, SMIs may exhibit superior distribution into affected peripheral tissues than conventional antivenoms, thereby making them an ideal candidate for topical therapies for snakebite-induced morbidity27,31.

The most notable SMIs with potential application in snakebite treatment are the PLA2 and SVMP inhibitors, varespladib and marimastat, which previously entered Phase 3 clinical trials for other indications33–38. Recent studies have shown that the therapeutic combination of marimastat and varespladib is particularly promising by providing preclinical protection against the lethal and local tissue destructive effects of geographically diverse viper venoms, including from Africa, Central America and Asia32,39. Unfortunately, SMIs remain largely unexplored in the context of treating snakebites in the Indian subcontinent, where conventional antivenoms fail to counter the vast inter and intraspecific venom variation in the region40–47. A few studies evaluating the usefulness of SMIs in India have assessed venoms of unknown origin and/or from a single geographic location32,39,48. While these studies have focussed on three of the ‘big four’ Indian snake species, the use of SMIs for treating bites from Russell’s viper (Daboia russelii), which is the snake species responsible for the largest number of snakebite deaths and disabilities worldwide, remains uninvestigated. The dearth of knowledge in this part of the world is particularly concerning since India is considered a snakebite hotspot, where over 58,000 snakebite-related deaths and three times as many disabilities are reported annually4. Since D. russelii is responsible for over half of snakebite-related deaths and disabilities in the country4, an effective solution for treating bites from Daboia will greatly help solve the problem posed by this neglected tropical disease.

To bridge this knowledge gap with the hope of improving future snakebite treatment in India, here we explore the effectiveness of SMIs, such as the PLA2 inhibitor varespladib, the SVMP inhibitor marimastat and the SVSP nafamostat, in countering toxicities inflicted by India’s medically most important snake species, Russell’s viper. Our findings demonstrate that varespladib and marimastat, individually or in a therapeutic combination, counter the diverse and variable toxicities caused by venom sourced from different geographic populations of D. russelii across India. Preincubation and rescue in vivo experiments using a murine model of envenoming suggest that SMIs can offer complete protection against the systemic and lethal effects of D. russelii envenoming, even with delayed treatment administration. Overall, our findings highlight SMIs as promising leads for counteracting the systemic envenoming pathology caused by D. russelii across India.

Materials and methods

Ethical clearance

Approval for evaluating the effectiveness of SMIs against D. russelii venoms in the murine model of envenoming was granted by the Institutional Animal Ethics Committee (IAEC) at the Indian Institute of Science (IISc), Bengaluru (CAF/Ethics/947/2023; 24-05-2023 and CAF/Ethics/082/2024; 26-06-2024). The animals (male CD-1 mice) were housed and quarantined at the Central Animal Facility, IISc, for seven days to minimise the confounders. Post quarantine, three- to four-week-old mice weighing 18 to 20 g were randomly segregated into groups of five animals per cage. The cages were subjected to a 12:12 day/night cycle at 18 to 24 °C with 60 to 65% relative humidity. All animal experiments adhered to the guidelines of the Committee for Control and Supervision of Experiments on Animals (CCSEA), Government of India. Inclusion/exclusion criteria were not used for selecting animals, and the experimenters were not blinded. We used male rather than mixed sex mice in this study due to supplier limitations in accessing female mice. Given the acute overwhelming toxicity caused by envenoming in this animal model, we do not anticipate any impact of the use of single sex mice on the outcomes of this study. The coagulopathic effects of venoms on human blood were evaluated with permission from the Institutional Human Ethics Committee, IISc, Bengaluru (IHEC: 09/31.03.2020). Blood samples were collected from healthy volunteers with informed consent.

Snake venoms

D. russelii venoms were sourced from various regions (Table S1) of India with appropriate permission from the State Forest departments: Andhra Pradesh: 16284/2016/WL-3; Goa: 2-66-WL-RESEARCH PERMISSIONS-FD-2022-23-Vol.IV/858; Karnataka: PCCF(WL)/E2/CR06/2018-19; Kerala: KFDHQ-1006/2021-CWW/WL10; KFDHQ-636/2021.CWW/WL10; Madhya Pradesh: #/TK-1/48-II/606); Maharashtra: 22(8)/WL/RESEARCH/CR-60 (17-18)/3349/21-22; Punjab: #3615;11/10/12; Rajasthan: F19 (29) Permission/MWL/2017-18/595 and West Bengal: 1023/WL/4R-12/2022. Venoms were also sourced from the Irula Snake Catchers Industrial Cooperative Society, Tamil Nadu. The lyophilised venom was reconstituted with molecular grade water (1 mg/ml), and the protein concentration was determined using the Bradford assay49 with bovine serum albumin (BSA, Sigma-Aldrich) as a standard (Table S1).

SMIs

Varespladib (SML1100), Marimastat (M2699) and Nafamostat (N0959) were procured from Sigma-Aldrich. The inhibitor stock solution (20 mg/ml) was prepared using Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; D8418, Sigma-Aldrich), and the working solution was prepared by serially diluting the stock solution with sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4).

Phospholipase A2 (PLA2) activity

The PLA2 activity of D. russelii venoms were evaluated as described previously40. The standard assay mixture contained (4-nitro-3-octanoyloxy-benzoic acid) NOB buffer (100 µl; 10 mM Tris-HCl, 10 mM CaCl2, 100 mM NaCl, pH 7.8) and D. russelii venoms (5 µg in 20 µl of NOB buffer) to which 500 µM of NOB substrate was added to bring the final volume to 220 µl. Then, the reaction mixture was incubated for 40 min at 37 °C, and the absorbance was measured at 425 nm every 10 min in an Epoch 2 microplate spectrophotometer (BioTek Instruments, Inc., USA). PLA2 activity was calculated based on the increase in absorbance at the 40th min, and results were expressed as nanomoles of the product released by nanogram of the protein per minute. In the PLA2 inhibition assays, D. russelii venoms (5 µg) were preincubated with various concentrations of varespladib (0–100 µM in NOB buffer in a final volume of 20 µl) at 37 °C for 15 min.

Proteolytic activity

Proteolytic activities of D. russelii venoms were assayed as described previously50. Azocasein (0.5% in 0.05 M Tris-HCl buffer, pH 8) was incubated with D. russelii venoms (10 µg) at 37 °C for 90 min. Bovine pancreatic protease (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) was used as a positive control. The reaction was terminated by adding 200 µl of trichloroacetic acid (TCA; 5%) and centrifuging at 1000 × g for 5 min. The supernatant (125 μl) was collected and mixed with equal volumes of 0.5 M NaOH, and the absorbance was measured at 440 nm using an Epoch 2 microplate spectrophotometer (BioTek Instruments, Inc., USA). In the proteolytic inhibition experiments, D. russelii venoms (10 µg) were preincubated with or without various concentrations of marimastat and/or nafamostat (0–100 µM in a final volume of 20 µl) at 37 °C for 15 min.

Cell viability

Cytotoxicity induced by D. russelii venom on murine C2C12 skeletal muscle myoblast cells (American Type Culture Collection; Cat no: CRL-1772; authenticated and mycoplasma tested) was assayed according to the published method with some modifications51. The cells were maintained as undifferentiated myoblasts at sub-confluent levels in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM, Gibco; Cat no: 11320033) supplemented with 10% foetal bovine serum (FBS, Sigma-Aldrich; Cat no: 10438-026), and 1% of Antibiotic-Antimycotics (Sigma-Aldrich; Cat no: A5955). Approximately 10,000 myoblast cells were transferred to each 96-well cell culture plate and incubated overnight at 37 °C with 5% CO2. When the cells reached 80–90% confluence, they were treated with D. russelii venom (50 µg/ml) for 180 min. After the treatment, cells were incubated with fresh media (100 µl) containing WST (Water-Soluble Tetrazolium) assay mixture (5 µl) for 60 min at 37 °C. The absorbance was measured at 450 nm using an Epoch 2 microplate spectrophotometer (BioTek Instruments, Inc., USA). The percentage of cytotoxicity or cell viability was calculated using 0.1% Triton X-100 as a positive control. For neutralisation studies, D. russelii venom (50 µg/ml) was preincubated with various concentrations of varespladib and/or marimastat (0–100 µM each) for 15 min at 37 °C prior to addition to the cells. Cells treated with varespladib and/or marimastat (100 µM) alone were used as drug controls.

Coagulation assays

The coagulopathic effects of D. russelii venoms on the intrinsic and extrinsic pathways were evaluated by assessing activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) and prothrombin time (PT), as described previously40. Blood samples were collected from healthy consenting volunteers using sodium citrate-containing vacutainers and centrifuged at 3500 × g for 15 min. Post centrifugation, the resultant platelet-poor plasma (PPP) was used in the coagulation assays. Briefly, 50 μl of PPP was incubated with D. russelii venom (5 μg in 50 µl PBS), along with PT or aPTT reagents according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The time taken for the initial appearance of the fibrin clot was measured using a Hemostar XF 2.0 coagulometer. A prewarmed calcium thromboplastin reagent (Uniplastin; 200 μl) was mixed with 50 μl of PPP for the PT control, while activated cephaloplastin reagent (Liquicelin-E; 100 μl) and 0.02 M CaCl2 (100 μl) were mixed with 50 μl of PPP for the aPTT control. In the inhibition assays, D. russelii venom (5 µg) was preincubated with varying concentrations of marimastat and/or nafamostat (0–100 µM) in a final volume of 50 µl for 15 min at 37 ⁰C.

Fibrinogenolytic activity

The human fibrinogen degradation activity of D. russelii venom was examined as described previously52. Briefly, 20 μg of fibrinogen (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) was incubated with D. russelii venom (2 μg) for 60 min at 37 °C. The degradation pattern of fibrinogen subunits were observed by performing electrophoresis on 12% sodium dodecyl sulphate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) under reducing conditions. The gels were stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue R-250 (Sisco Research Laboratories Pvt. Ltd, India) and imaged using an iBright CL1000 gel documentation system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA). Following this, ImageJ software was used for densitometric analysis of each band53. In the inhibition experiments, D. russelii venom (2 µg) was preincubated with marimastat (100 µM) or a mixture of marimastat and nafamostat (100 µM each) for 15 min at 37 °C before electrophoresis.

Venom median lethal dose (LD50)

The venom LD50s of the pan-Indian D. russelii populations were determined via intravenous (i.v.) or intraperitoneal (i.p.) routes of administration54,55. Five distinct doses of each venom diluted in physiological saline (0.9% NaCl) in a final volume of 200 μl were administered to five groups of male CD-1 mice (18–22 g) with five animals each40 (Tables S2 and S3). Mortality was monitored hourly for 24 and 48 h after i.v. and i.p. injections, respectively, and the median lethal dose was calculated using Probit statistics56.

Preclinical efficacy: preincubation

The preclinical efficacy of SMIs was assessed in the murine model of envenoming using the preincubation model55. Here, a challenge dose (2.5x LD50) of venom was mixed with various concentrations of varespladib, marimastat, and nafamostat, individually or in combination. SMIs were serially diluted to 1.5–2.5% in saline from a 20 mg/ml stock prepared in DMSO. The final reaction mixture was adjusted to 200 μl in saline and then incubated at 37 °C for 30 min. Following incubation, the mixture was administered to five mice through i.v. Mice (n = 5) receiving only venom or SMIs served as positive and negative controls, respectively. Mice were monitored for 24 h for signs of toxicity, such as paralysis, drooping of the eyelids, bleeding from the mouth, sickness, sluggishness, etc. Following this observation period, the number of dead and surviving animals were recorded.

Preclinical efficacy: rescue experiments

A challenge dose (2.5x LD50) of venom, prepared in saline, was administered intraperitoneally (i.p.) to five mice. Following venom injection, an i.v. dose of varespladib and marimastat (60–120 μg/mouse)—either individually or in combination—prepared in a final volume of 100–200 μl of saline, was administered at various time intervals (0, 15, and 30 min). Another group of mice (n = 5) receiving venom alone served as the positive control. Mice were monitored for 24 h, and data was recorded as described above. Although a subcutaneous (s.c.) route of venom injection would mimic the real-world scenario of snakebite more closely, an i.p. route was chosen for this experiment, as the former required substantially large amounts of venom to cause murine lethality (>40 μg). Mice injected with 100 μg of D. russelii venom, corresponding to a 2.5x LD50 dose, succumbed to lethal effects rapidly, rendering rescue experiments with secondary treatment unviable.

Statistical analysis

One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s and Sidak’s multiple comparison tests was used to statistically compare biochemical and cytotoxicity assay results, while the log-rank (Mantel–Cox) test was used to estimate the statistical significance of the survival curve comparison. The non-linear regression curve fitting and the sum of squares F test were used to calculate the in vitro IC50 values of small molecules and the variation in their effectiveness across different populations. All statistical analyses were carried out using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software 8.0, San Diego, California, USA; www.graphpad.com).

Results

Varespladib and marimastat inhibit D. russelii venom biochemistries

We first evaluated the ability of varespladib, marimastat and nafamostat to neutralise the in vitro PLA2 and proteolytic activity of D. russelii venom collected from geographically diverse populations. The venoms from the northern (Punjab: PB) and southern (Tamil Nadu: TN) Indian populations exhibited the highest PLA2 activity (335.85 nmol/mg/min and 297.25 nmol/mg/min, respectively), followed by the other southern (Kerala: KL), western (Maharashtra: MH), southwestern (Goa: GA) and central (Madhya Pradesh: MP) regions (121.32 nmol/mg/min, 103.94 nmol/mg/min, 98.24 nmol/mg/min and 73.88 nmol/mg/min, respectively; Fig. 1A; Supplementary Data 1A). In contrast, D. russelii venoms from all other regions exhibited minimal PLA2 activity, ranging from 7.33–14.05 nmol/mg/min (Fig. 1A; Supplementary Data 1A). In inhibition assays, the PLA2 inhibitor varespladib was able to neutralise PLA2 activity in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 1C) and countered the high PLA2 activity of southern (TN) and northern (PB) regions (IC50: 7.227 μM and 5.925 μM, respectively; Fig. 1C, E), albeit being relatively more effective against the latter (Supplementary Data 1A). Varespladib also effectively inhibited the more modest PLA2 activities of venoms sourced from other Indian regions (all IC50: <2 μM; Fig. 1E).

Fig. 1. Enzymatic activities of the pan-Indian D. russelii venoms and their inhibition by SMIs.

This figure illustrates the (A) PLA2 and (B) proteolytic activities of D. russelii venoms from across India and their dose-dependent inhibition by (C) varespladib and (D) marimastat. The IC50 (n = 3) of varespladib and marimastat is reported in (E) and (F), respectively. Here, *p < 0.01; ***p < 0.0001 (one-way ANOVA; p-values are provided in Supplementary data 1A); ns non-significant, PB Punjab, KL Kerala, KA Karnataka, GA Goa, MH Maharashtra, MP Madhya Pradesh, AP Andhra Pradesh, TN Tamil Nadu, WB West Bengal, RJ Rajasthan, IC50 Inhibitory Concentration 50, nmol nanomol, ng nanogram, min minute, µm micromolar.

When the proteolytic activities of the pan-Indian D. russelii venoms were investigated using azocasein as a protease substrate, one of the southern (Karnataka: KA) Indian populations exhibited the highest activity (50.95%; Fig. 1B; Supplementary data 1A), followed by the western (Rajasthan: RJ), central (MP), southwestern (GA) and southeastern (Andhra Pradesh: AP) regions (39.45%, 35.90%, 34.17% and 33.62%, respectively; Fig. 1B; Supplementary data 1A). While the eastern (West Bengal: WB), northern (PB) and one of the southern (TN) populations exhibited little to no activity (0.01–2.06%), the rest of the pan-Indian D. russelii venom samples exhibited modest proteolytic activity, ranging between 16.61 and 20.59% relative activity (Fig. 1B; Supplementary data 1A). The matrix metalloprotease-inhibiting drug, marimastat, effectively inhibited the SVMP-driven proteolytic activities of D. russelii venoms in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 1D). The drug was not only effective against populations with high proteolytic activities (KA IC50: 1.977 μM; Supplementary data 1A) but also exhibited highly potent inhibitory effects against other venoms with more moderate activities: MP: IC50: 1.508 μM; RJ IC50: 1.667 μM; AP IC50: 1.957 μM; GA IC50: 2.33 μM (Fig. 1F; Supplementary Data 1A). In contrast, the serine protease inhibitor, nafamostat, failed to inhibit the protease activity of D. russelii venom (Fig. S1).

Varespladib, marimastat or a combination thereof inhibit pan-Indian D. russelii venom-induced cytotoxicity

Next, we evaluated the ability of varespladib and marimastat to neutralise venom-induced cytotoxicity using murine C2C12 skeletal muscle myoblasts in a WST (Water-Soluble Tetrazolium) cell viability assay. In our assays, D. russelii venoms from southeastern (AP: 79.80%), northern (PB: 78.56%), southern (TN: 77.98%) and western (MH: 70.08%) populations induced greater cytotoxicity than other populations (Fig. 2; Supplementary Data 1B). Venom from eastern (WB: 69.47%), southern (KL: 69.77% and KA: 67.69%), central (MP: 66.39%), western (RJ: 60.38%), and southwestern (GA: 50.12%) populations exhibited more moderate cytotoxicity (Fig. 2; Supplementary data 1B). Inhibition experiments with varespladib and marimastat—individually or in a therapeutic drug combination—showed significantly reduced D. russelii venom-induced cytotoxicity. Marimastat almost completely inhibited cytotoxicity induced by southern (KA: 97.51%) and southeastern (AP: 94.89%) populations, while varespladib inhibited the cytotoxicity caused by the northern (PB: 85.32%) and western (MH: 88.67%) populations (Fig. 2; Tables S4–S6). Both inhibitors (0–100 μM) were effective in reducing the cytotoxicity of southwestern (GA), southern (KL) and central (MP) populations by 72.88–94.85% (Fig. 2; Tables S4–S6). While both drugs only partially (41.20–70.51%) inhibited the cytotoxicity of the southern (TN), eastern (WB) and western (RJ) regions, the therapeutic combination of varespladib and marimastat nearly completely (85.58–90.59%) inhibited these activities (Fig. 2; Tables S4–S6), suggesting that simultaneously blocking both PLA2 and SVMP toxins might be required to prevent cell death caused by venom from these populations. Neither inhibitor exhibited cytotoxicity at the highest test concentrations (100 μM), confirming that they are not toxic to cells (Fig. S2).

Fig. 2. Cytotoxicity of pan-Indian D. russelii venoms and their inhibition by varespladib, marimastat, or a combination thereof.

This figure shows the cytotoxicity of D. russelii venoms (red) from across India and their dose-dependent inhibition by varespladib (blue), marimastat (orange) or a combination of the two (grey). Here, the y-axis represents cell viability in percentage, the x-axis shows inhibitor concentrations in µM (micromolar), while error bars represent the standard deviation (n = 3). The venom-induced cytotoxicity with or without SMIs was compared by one-way ANOVA (p-values are provided in Tables S4–S6 and Supplementary data 1B). PB Punjab, KL Kerala, KA Karnataka, GA Goa, MH Maharashtra, MP Madhya Pradesh, AP Andhra Pradesh, TN Tamil Nadu, WB West Bengal, RJ Rajasthan.

Marimastat by itself or in combination with nafamostat inhibits D. russelii venom-induced coagulopathy

SVMPs and SVSPs are key enzymatic toxins responsible for coagulopathy associated with viper bites57,58. Venoms of D. russelii from across India exerted potent procoagulant effects on human plasma by reducing the standard prothrombin time (PT: ~18 s) and activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT: ~32 s) to ~7 ± 2 s (Fig. S3). We then tested the abilities of the SVMP inhibitor marimastat and the SVSP inhibitor nafamostat in neutralising these potent effects. Marimastat reversed the PT and aPTT alterations induced by southern (TN and KL), southwestern (GA) and western (MH) populations in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 3A, C). Marimastat was also capable of inhibiting PT alterations induced by venom from northern (PB) and eastern (WB) populations and the aPTT alterations caused by the southeastern (AP) and central (MP) populations (Fig. 3A, C). However, marimastat was ineffective against venom from one of the southern (KA) and western (RJ) populations, where reduced PT and aPTT times were documented even at the highest dose (100 µM) of the drug (Fig. 3B, D), suggesting that different venom toxins may be driving this effect. Similarly, marimastat failed to inhibit the PT alterations caused by the central (MP) and southeastern (AP) populations and aPTT alterations by northern (PB) and eastern (WB) populations at the highest tested concentration of 100 µM (Fig. 3B, D). When we examined the ability of varespladib to inhibit PT and aPTT alterations induced by one of the southern (TN) populations with a venom rich in PLA2, the drug failed to prevent coagulopathy (Fig. S4; Supplementary Data 1C).

Fig. 3. Inhibition of D. russelii venom-induced coagulopathy by marimastat and a combination of marimastat and nafamostat.

Panels (A, B) and (C, D) show the effects of marimastat in reversing the effects of the pan-Indian D. russelii venoms on the extrinsic (PT) and intrinsic (aPTT) blood coagulation pathways, respectively. Marimastat-sensitive populations are depicted in (A) and (C), while those that required nafamostat for a complete reversal of coagulopathy are shown in (B) and (D). The inhibitory effect of the marimastat and nafamostat drug combination is depicted in (E, F). The time (seconds) taken for the formation of the first clot (y-axis) is plotted against various doses (µm) of SMIs (x-axis). A dotted horizontal line indicates the negative control and the data points are presented as Mean ∓ SEM (n = 3). Inhibition of D. russelii venom-induced coagulopathy by SMIs was compared using one-way ANOVA (p-values are provided in Supplementary data 1C); PB Punjab, KL Kerala, KA Karnataka, GA Goa, MH Maharashtra, MP Madhya Pradesh, AP Andhra Pradesh, TN Tamil Nadu, WB West Bengal, RJ Rajasthan.

Consequently, we next investigated the inhibitory effects of a mixture of marimastat and nafamostat for those venoms where marimastat alone was ineffective in completely reversing coagulopathy. The therapeutic mixture countered the PT and aPTT alterations induced by southern (KA) and western (RJ) populations. It also reversed the PT alterations by southeastern (AP) and central (MP) Indian populations and aPTT alterations by northern (PB) and eastern (WB) populations back to baseline levels (Fig. 3E, F; Supplementary data 1C).

SMIs prevent human fibrinogenolysis by D. russelii venom

Because fibrinogen is a key clotting factor that acts as a precursor to fibrin clots and is well known to be depleted during snakebite coagulopathy, we next assessed the inhibition of venom-induced fibrinogenolysis by SMIs. The pan-Indian D. russelii venoms mainly affected the Aα and Bβ subunits of human fibrinogen, as evidenced by the resulting degradation profile (Fig. S5). Venoms from the southern (TN), eastern (WB) and central (MP) regions were the exceptions, as they additionally exhibited considerable fibrinogenolytic activity on the γ-chain of fibrinogen (Fig. S5). Venoms from southern (KL), southeastern (AP) and western populations (MH and RJ), however, primarily affected the Aα subunit, while one of the southern populations (KA) cleaved the Bβ subunit. Other populations (southwestern: GA and northern: PB) exhibited partial degradation of fibrinogen (Fig. S5).

When assessing the ability of marimastat to protect against venom-induced fibrinogenolysis, we found it to be very effective against D. russelii venom from the northern (PB), southern (KA and KL), southeastern (AP), southwestern (GA) and western (RJ) regions (Fig. S5). However, marimastat alone did not completely neutralise the fibrinogenolytic activities of certain populations, specifically southern (TN), western (MH), central (MP) and eastern (WB) populations, but the double drug combination of marimastat and nafamostat was found to be protective, suggesting a dual role of SVMPs and SVSPs in the fibrinogenolysis caused by these venoms (Fig. S5).

SMIs neutralise D. russelii venom-induced lethality in a murine preincubation model of envenoming

Before determining the neutralising potency of SMIs, we estimated the i.v. median lethal dose (LD50) of D. russelii venoms from across India. The highest venom potency was documented for the central (MP: 0.11 mg/kg), northern (PB: 0.14 mg/kg) and one of the western (RJ: 0.15 mg/kg) populations (Table S2). These were followed by the other southeastern (AP: 0.18 mg/kg), western (MH: 0.19 mg/kg), southern (KA: 0.22 mg/kg; TN: 0.259 mg/kg) and eastern (WB: 0.34 mg/kg) regions.

Varespladib exhibited varying efficacy against the pan-Indian D. russelii venoms in a preincubation neutralisation assay, where the drug and venom were mixed and incubated for 30 min before intravenous co-injection into mice. At an initial dose of 60 µg/mouse, varespladib provided complete protection against 2.5x LD50 venom challenge doses from the western (MH) and central (MP) Indian populations (Fig. 4; Table S7). However, at the same dose, varespladib offered only 40% protection against eastern (WB) and western (RJ) populations, and it failed to protect mice injected with venom from the southern (TN and KA), southeastern (AP) and northern (PB) regions. While an increased dose of varespladib (90 µg/mouse) completely protected mice against the lethal effects of the southern (TN) population (Fig. 4; Table S7), only 60–80% survival was documented against the western (RJ) and northern (PB) regions, respectively (Fig. 4; Table S7), and a much higher dose (120 µg/mouse) was needed to achieve complete protection. Interestingly, even at the highest test dose (120 µg/mouse), varespladib provided only 40% protection against the eastern (WB) population while failing to prevent lethality caused by venom from the southern (KA) and southeastern (AP) populations (Fig. 4; Table S7). However, varespladib did extend the survival time of mice from a mean of 3 min to 39 min (13x) against the venoms of both these populations.

Fig. 4. Different SMIs protect mice against the lethal effects of D. russelii across India.

Graphs depict survival time (hours) on the x-axis and the survival percentage on the y-axis. In these graphs, red lines represent the venom (2.5× LD50) only positive control group. Groups of mice (n = 5) receiving 2.5× LD50 of D. russelii venom and various concentrations of SMIs (60, 90, and 120 µg/mouse), or their therapeutic mixture (120 µg of each drug/mouse), i.v., are shown. M marimastat, V varespladib, N nafamostat.

In contrast, 60 µg/mouse of marimastat was sufficient to neutralise the lethal effects of venom from the southern (KA), southeastern (AP), southwestern (MH) and central (MP) regions (Fig. 4; Table S7). However, at this dose, the drug failed to protect mice from venom lethality caused by the northern (PB), one of the southern (TN), eastern (WB) and western (RJ) populations. When the therapeutic dose was escalated to 120 µg/mouse, complete protection was documented against the northern (PB) and southern (TN) populations, while only 60% survival was noted against the eastern (WB) population (Fig. 4; Table S7). Interestingly, the drug failed to protect mice injected with the venom from the western (RJ) region, even at this higher dose, though it did extend the survival time of mice from a mean of 3 min to 36 min (12x; Fig. 4; Table S7). As marimastat was not fully protective against this population, we then tested the efficacy of the serine protease inhibitor, nafamostat, which we previously showed to inhibit coagulopathy caused by this venom alongside marimastat (Fig. 3E, F). At the highest tested dose (120 µg/mouse), treatment with nafamostat offered only modest protection by delaying the onset of lethality from a mean of 3 min to 480 min (160x; Fig. 4; Table S7). When a combination of marimastat and nafamostat (120 µg/mouse of each) was tested, it only offered 60% protection from venom-induced lethality (Fig. 4; Table S7).

Since both varespladib and marimastat offered 40% and 60% protection, respectively, against D. russelii venom from the eastern (WB) population, we also evaluated the ability of a dual drug combination (120 µg/mouse of each drug) and found that a mixture of varespladib and marimastat provided complete protection from venom-induced lethality (Fig. 4; Table S7). Collectively, these findings show that treatment with varespladib or marimastat provides protection against lethality caused by all populations of D. russelii across India, except for the eastern population (WB), which required the dual drug combination to deliver preclinical efficacy.

Efficacy of SMIs against venom-induced lethality in a rescue model of snake envenoming

To better replicate the real-world scenario of snakebite envenoming, we next tested the neutralisation potency of SMIs in rescue experiments, where drug treatments were injected after the venom challenge. Given animal ethics considerations, we performed these experiments on selected venoms, specifically from populations that were either rich in PLA2, SVMP or both toxin types: PLA2-rich northern (PB), SVMP-rich southern (KA), and PLA2 and SVMP-rich central (MP) populations (Fig. 1A, B). In these rescue experiments, mice were administered with a 2.5x LD50 venom challenge dose via the i.p. route (Table S3), followed by the intravenous administration of different SMIs (i.e. those relevant to each particular venom) at various time intervals after venom injection (0, 15 and 30 min later).

The positive control receiving venom alone resulted in the lethality of all mice, with those envenomed with northern (PB) and southern (KA) venom succumbing within 6.5 h, while those receiving the central (MP) venom died within 4.5 h (Fig. 5). Rescue experiments revealed the effectiveness of varespladib (120 µg/mouse) against the PLA2-rich D. russelii venom from northern (PB) India, as the drug showed complete protection against venom-induced lethality, even when administered 30 min post-venom injection (Fig. 5; Table S8). In contrast, while marimastat was effective in neutralising venom-induced lethality against this population in the preincubation experiments, it was ineffective in rescue experiments, even when administered at a dose of 120 µg/mouse with no time delay after venom delivery (Fig. 5; Table S8). Marimastat did delay the onset of lethality caused by venom from the southern (KA) population. Still, it only provided a 40% survival rate against the SVMP-rich venom from the southern (KA) population at the end of the experimental time course (24 h) and when administered directly after venom injection (i.e., 0 min delay; Fig. 5; Table S8). Since varespladib did not protect from the toxic effects of the southern (KA) population of Daboia venom in the preincubation experiment, rescue experiments were not performed with this drug (Fig.4; Table S8). Similarly, against the central Indian (MP) population, which was rich in both SVMP and PLA2, varespladib (120 µg/mouse) and marimastat (120 µg/mouse) on their own provided only 60% and 40% protection, respectively, when dosed immediately after venom challenge (Fig. 5; Table S8). However, when a therapeutic mix of varespladib and marimastat at 120 µg/mouse each was injected, complete protection from venom-induced lethality was observed even with the delayed drug administration (i.e., 30 min post-venom injection; Fig. 5; Table S8).

Fig. 5. The preclinical efficacy of varespladib and marimastat in rescue experiments.

Here, graphs depict survival time (hours) on the x-axis and the survival percentage on the y-axis. In these graphs, red lines represent the positive control or venom (2.5× LD50) only group. Groups of mice (n = 5) receiving 2.5× LD50 of D. russelii venom (i.p.) and SMIs (120 µg/mouse: i.v.) or their therapeutic mix at various time points after venom injection are shown.

Discussion

Russell’s viper is the most medically important snake species in the Indian subcontinent and is likely responsible for the highest number of snakebite-related deaths and disabilities globally4. The venom of this snake is dominated by three prominent toxin families, SVMP, PLA2 and SVSP, which are found in varying abundances across its geographical range40,43,44,59,60. The medical importance of these toxins in Daboia venoms makes them an ideal target for developing more effective snakebite therapies. Recently, SMIs have been described as promising toxin-inhibiting alternatives to antivenom treatment. For example, varespladib and its orally administrable methylated form have shown promising levels of PLA2 inhibition across several snake species, including vipers25,35. Similarly, marimastat and other matrix metalloproteinase inhibitors effectively neutralise several SVMP-rich viper venoms27,32,61. Until now, however, the potential of SMIs in treating snakebites in India has mainly remained undescribed. To address this shortcoming and to explore the potential use of SMIs against the world’s most medically important snake species, we assessed the effectiveness of varespladib and marimastat in countering the toxicities of venom sourced from geographically diverse populations of Indian D. russelii.

In vitro, varespladib potently inhibited the PLA2 activity of most of the pan-Indian Daboia venoms (Fig. 1C, E). Similarly, marimastat effectively countered Daboia venom-induced proteolysis in many regions (Fig. 1D, F). Further, both drugs could inhibit the cytotoxicity induced by venoms from the southwestern (GA), southern (KL) and central (MP) regions (Fig. 2), suggesting that both PLA2s and SVMPs contribute to the cytotoxic effects seen in these populations. Marimastat alone inhibited the cytotoxicity caused by the venoms from the southern (KA) and southeastern (AP) regions, highlighting the role of SVMPs in driving cytotoxicity. In contrast, varespladib inhibited the cytotoxicity induced by northern (PB) and western (MH) region venoms, suggesting that PLA2s are primarily responsible for cytotoxicity in these populations (Fig. 2). As both PLA2s and SVMPs were contributing to the overall cytotoxicity in the southern (TN), eastern (WB) and western (RJ) regions, a combination of varespladib and marimastat was necessary for the near-complete inhibition of this activity. Similarly, marimastat and nafamostat were able to prevent PT and aPTT alterations caused by Russell’s viper venom, indicating that SMIs can counter venom-induced coagulopathy, which is considered one of the most clinically relevant symptoms associated with the bite from this species. Overall, our results suggest that SMIs are very effective in neutralising the in vitro toxicities of D. russelii venom. However, more than one SMI may be needed in certain regions.

Because of the potent inhibition of D. russelii venom in vitro, we then tested the abilities of SMIs to protect mice from the lethal effects of envenoming in vivo. In our WHO-approved preincubation assays, varespladib and marimastat (i.v.) were able to protect mice from the lethal effects of Russell’s viper venom (i.v.) from various corners of India (Fig. 4). However, the two drugs showed different neutralisation profiles, with venom from the western (RJ) Indian region being fully countered by varespladib but not marimastat (Fig. 4). At the same time, the reverse was the case against the lethal effects of southeastern (AP) and one of the southern (KA) regions (Fig. 4). Interestingly though, mice injected with D. russelii venom from northern (PB), western (MH), central (MP) and one of the southern (TN) regions were fully protected by either varespladib or marimastat (Fig. 4). This finding is particularly surprising and, perhaps, hints at an uninvestigated synergy between SVMPs and PLA2 toxins in this context. Alternatively, this could suggest that neutralising either SVMP or PLA2 toxins could be enough to bring down the overall toxicity of D. russelii venom in certain regions. However, both SMIs failed to protect mice against the lethal effects of D. russelii venom from the eastern (WB) Indian region as solo therapies. A therapeutic mix of the two drugs, however, was found to be effective in offering complete protection against this population, suggesting that simultaneous inhibition of both SVMP and PLA2 toxins is critical for preventing venom lethality in certain parts of the country (Figs. 4, 6). These findings emphasise the complexity of intraspecific venom variation across India and highlight the need to better understand the interplay between different toxin classes in the context of causing systemic envenoming pathology.

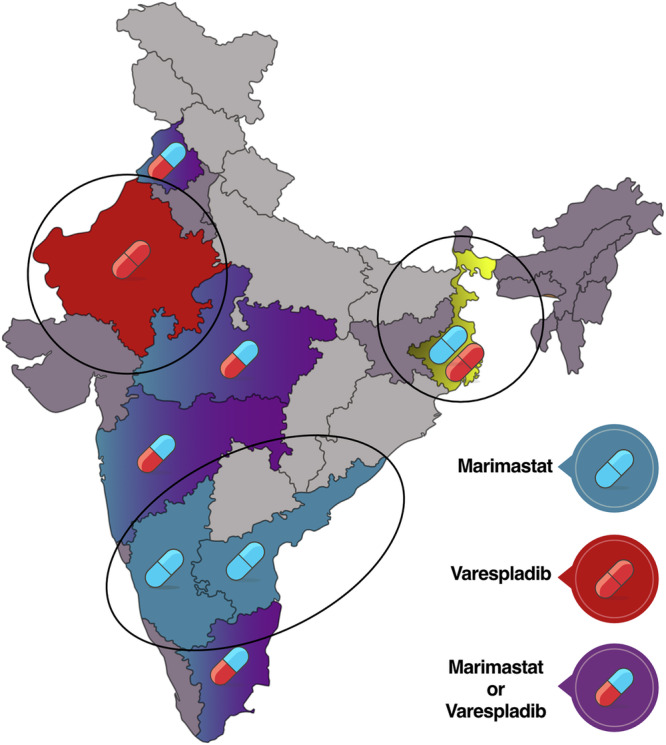

Fig. 6. Proposed strategy for trialling SMIs for treating D. russelii envenoming in India.

Based on the preclinical findings of this study, drugs (varespladib, marimastat or their therapeutic combination) that effectively countered D. russelii venom-induced toxicity from different regions are shown as pills on a map of India. The three regions that may require specific drugs or drug combinations are marked. This visualisation may help identify sites for future clinical trials designed to evaluate the efficacy of these drugs in snakebite patients.

Because preclinical experiments where venom and treatment are coincubated together before administration are increasingly recognised to be an unrealistic measure of likely clinical efficacy (i.e. this model represents best-case conditions for first triaging whether therapy can provide efficacy in vivo62), we undertook rescue experiments to replicate a real-world snakebite scenario. Experiments with selected venoms injected intraperitoneally (i.p.) followed by intravenous (i.v.) treatment with SMIs further emphasised how variable intraspecific venom compositions can impact therapeutic efficacy, with varespladib protecting mice injected with PLA2-rich venom from the northern (PB) region, while marimastat was inefficacious, whereas marimastat offered a modest degree of protection against the SVMP-rich venom from the southern (KA) Indian population, with varespladib untested due to inefficacy in preincubation experiments (Fig. 5). While the limited efficacy of marimastat in this model against the southern (KA) population was underwhelming, evidence of a shift in survival times away from the venom control advocates for future experiments further escalating the dose of marimastat. Critically, these rescue experiments also demonstrated that combination therapy of marimastat and varespladib was required to prevent lethality caused by the central (MP) Indian population of D. russelii, as the individual drugs only showed 40% and 60% protection in this model, despite both providing complete protection in preincubation experiments as solo therapies. Perhaps most promisingly, this dual drug combination against the central (MP) population and varespladib against the northern (PB) population provided complete protection against lethal venom effects even when dosed 30 min after the venom challenge (Fig. 5).

Overall, the findings of our neutralisation experiments suggest that both SVMP and PLA2 are the clinically most relevant toxins in D. russelii venom and neutralising both toxin types seems to be sufficient for offering complete protection against lethal venom effects, irrespective of the considerable venom variation documented in this species across India40,43,44. Perhaps most surprising is evidence that for most D. russelii populations, a single SMI can neutralise lethal venom effects in the preincubation model of envenoming, and for some populations, it does not matter which toxin family (i.e., PLA2 or SMVP) is inhibited. This is particularly surprising since snake venoms are often considered a complex cocktail with many different toxins found in various proportions, making the effective neutralisation of distinct drug targets challenging. As mentioned above, these findings may suggest that the PLA2 and SVMP toxins found in D. russelii may work in an additive or synergistic manner, and inhibiting one of these toxin types may be sufficient to prevent severe pathology. Such observations are analogous to recent studies showing that African spitting cobra venoms rely on a combination of cytotoxic 3FTx and PLA2 toxins to cause severe local envenoming and that inhibiting one of these toxin classes is sufficient to inhibit most venom toxicity63,64. Irrespectively, these findings provide strong support for future clinical testing of marimastat, varespladib and a dual drug combination of the two to robustly assess their efficacy in treating Russell’s viper bites in the Indian subcontinent.

Given the challenges associated with conventional equine antivenom treatment, such as cost of production, undesirable incidences of adverse reactions, animal ethics considerations, and the inability to counter inter- and intraspecific venom variation41,44,65,66, alternative therapies for tackling snakebite are highly desired. As outlined by our preclinical investigation, various SMIs - either as solo therapies or in combination - may offer a promising alternative to conventional antivenoms. While the preclinical efficacy of certain SMIs in countering viperid snake envenoming has been demonstrated in many regions of the world, including sub-Saharan Africa, the Middle East and Central America32,39,48,63, their effectiveness in countering bites from medically important snakes of the Indian subcontinent is largely unexplored. A few studies assessing the effectiveness of SMIs against Indian snakes have investigated venoms of unknown origin and/or from a single geographic location32,39,48. However, while three of the ‘big four’ Indian snake species have been included in these studies, the efficacy of SMIs against the venom of Indian D. russelii, which is responsible for the largest number of snakebite deaths and disabilities worldwide, remained uninvestigated. Despite the absence of published preclinical efficacy data, varespladib is currently being clinically tested for treating snakebites in human trials in several regions across India67,68. Several studies in the past have unravelled considerable inter- and intraindividual venom variation in D. russelii venom and the negative impact of this variation on the effectiveness of Indian antivenom40,43,44. Consistent with these reports on varying antivenom efficacy across India, our findings, for the first time, reveal that the efficacy of SMIs, too, varies geographically. Thus, our findings accentuate the importance of undertaking preclinical studies on SMIs for guiding clinical trials and, particularly in this context, clinical trial sites.

Based on our in vitro and in vivo results, we have generated a detailed map depicting the efficacies of SMIs in countering various toxic functions of venoms sourced from D. russelii from across India. This detailed map can potentially guide health policy decisions and the future deployment of SMIs, either as ancillary or standalone therapies in future clinical trials, to counter D. russelii envenoming. We have identified three main regions that may require specific SMIs, while varespladib and marimastat are likely to be effective everywhere else in the country (Fig. 6). In certain regions of southern (KA and AP) India, marimastat alone seems to be sufficient in countering Russell’s viper envenoming, whereas, in western (RJ) India, varespladib seems to be effective (Fig. 6). Interestingly, in northern (PB), southern (TN), western (MH), and central (MP) India, either marimastat or varespladib could be deployed. In eastern (WB) India, however, a combination of both marimastat and varespladib would be necessary (Fig. 6), and given evidence of the increased efficacy conveyed by the dual drug combination in rescue experiments in the central (MP) region, it may be reasonable to anticipate that in the long term, the therapeutic combination of marimastat and varespladib could be beneficial in boosting the therapeutic potency of either drug across much of the country.

Since certain SMIs under study (e.g., marimastat and the methylated prodrug version of varespladib) can be administered orally and may prove to not require administration in a clinical environment, unlike antivenoms, these drugs could greatly enhance the clinical outcomes of snakebite treatment in India. In a country where it takes several hours for victims to reach hospitals post-snakebite, varespladib and marimastat or their therapeutic combination could be a valuable early community-level intervention to provide snakebite victims with precious additional time to seek clinical assistance and could potentially offer protection against the toxic effects of D. russelii venom, possibly reducing the need for or the dose of secondary antivenom. However, the preclinical findings in this study require validation through robust human clinical trials to assess their efficacy and potential utility in snakebite patients, including evaluating whether the combination therapy proposed here can counter the therapeutic challenge D. russelii venom variation poses in India.

Before clinical trials can commence, several key research activities are needed to enhance the potential use case for SMIs. First, dose optimisation remains crucial for robustly evaluating the efficacy and safety of these treatments, particularly in the context of optimising an appropriate oral dosing regimen with desirable pharmacokinetic characteristics suitable for snakebite indication. Further, investigating the potential of SMIs in protecting against the effects of local envenoming caused by D. russelii (i.e. local tissue and muscle damage) remains unexplored and warranted, as such drugs could potentially alleviate or reduce the severity of the incapacitating, morbidity-causing, consequences of envenoming. Additionally, owing to the diversity of venomous snakes in India, notably Naja (cobras), Bungarus (kraits), Echis (saw-scaled vipers), and other neglected yet medically important snake species, a broad-spectrum approach would be desirable for treating snakebite in India. For instance, previous reports documented the effectiveness of varespladib against N. naja69 and B. caeruleus48 venom, while marimastat has previously demonstrated neutralising effects against the venom of E. carinatus32,39,70. Therefore, in a similar manner to the data presented here suggesting a combination therapy may provide broad protection against the intraspecific venom variation observed in D. russelii (Figs. 5, 6), the combination of varespladib and marimastat may prove to be beneficial against bites by other medically important Indian snake species that exhibit extensive interspecific venom variation. Studies evaluating the preclinical efficacy of SMIs against other Indian snake species should, therefore, be a priority, as leveraging the strengths of each component in a combination therapy could increase the geographical spectrum and cross-species efficacy of a therapy32,39, which has the potential to improve the clinical outcomes of snakebite patients in India.

Conclusion

Russell’s viper is the primary cause of snakebite envenoming in the Indian subcontinent and is likely responsible for nearly 30,000 of the 58,000 estimated snakebite-related fatalities annually. Considering the many limitations of currently used conventional antivenoms, exploring alternative strategies to mitigate snakebite is imperative. This study reports crucial findings concerning the use of two phase-2 approved SMIs (varespladib and marimastat) to counter venom-induced lethality caused by pan-Indian populations of D. russelii. These drugs, individually or in combination, neutralised the toxic effects of D. russelii venom under in vitro conditions, and in murine models of envenoming, they were capable of fully protecting mice from the lethal effects of diverse populations of D. russelii from across India, even with delayed administration. These findings have enabled us to formulate an SMI deployment strategy in India to support the future development of new treatments for D. russelii envenoming in the region and should facilitate the use of therapeutic combinations of SMIs in human clinical trials to assess their safety and efficacy in snakebite victims robustly.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the State Forest Departments of Andhra Pradesh, Goa, Karnataka, Kerala, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Punjab, Rajasthan and West Bengal for the kind support and permits for venom collection. The authors also thank Romulus Whitaker, Ashok Captain, Gerrard Martin, Ajay Kartik, Prasad Gond and Ajinkya Unawane for their valuable assistance with sample collection. GVR was supported by the DBT Research Associateship (DBT-RA) Programme of the Department of Biotechnology [DBT-RA/2023/January/N/3636]. KS was supported by the DBT/Wellcome Trust India Alliance Intermediate Fellowship (IA/I/19/2/504647).

Author contributions

Conceptualisation: KS; Investigation: GVR, SK, and KS; Analyses: GVR and KS; Interpretation: GVR, NRC, and KS; Figures: GVR and KS; Manuscript writing: GVR, SK, NRC, and KS; Manuscript editing: NRC and KS.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Medicine thanks Juliana Zuliani and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer review reports are available.

Data availability

The data used to plot all figures in this publication are provided in Supplementary Data 2.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s43856-025-00900-z.

References

- 1.Harrison, R. A. et al. Snake envenoming: a disease of poverty. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis.3, e569 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Longbottom, J. et al. Vulnerability to snakebite envenoming: a global mapping of hotspots. Lancet392, 673–684 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gutierrez, J. M. et al. Snakebite envenoming. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim.3, 17063 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Suraweera, W. et al. Trends in snakebite deaths in India from 2000 to 2019 in a nationally representative mortality study. Elife9 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Warrell, D. A. et al. New approaches & technologies of venomics to meet the challenge of human envenoming by snakebites in India. Indian J. Med Res.138, 38–59 (2013). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Silva, H. A., Ryan, N. M. & de Silva, H. J. Adverse reactions to snake antivenom, and their prevention and treatment. Br. J. Clin. Pharm.81, 446–452 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaur, N., Iyer, A. & Sunagar, K. Evolution bites—timeworn inefficacious snakebite therapy in the era of recombinant vaccines. Indian Pediatr.58, 219–223 (2021). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Casewell, N. R. et al. Causes and consequences of snake venom variation. Trends Pharm. Sci.41, 570–581 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Casewell, N. R. et al. Medically important differences in snake venom composition are dictated by distinct postgenomic mechanisms. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA111, 9205–9210 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.N. R. Casewell, N. R. et al. in Venomous Reptiles and Their Toxins: Evolution, Pathophysiology and Biodiscovery (ed. Fry, B.) 347–363 (Oxford University Press, 2015).

- 11.Teixeira, C. F. et al. Inflammatory effects of snake venom myotoxic phospholipases A2. Toxicon42, 947–A62 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gutierrez, J. M. & Ownby, C. L. Skeletal muscle degeneration induced by venom phospholipases A2: insights into the mechanisms of local and systemic myotoxicity. Toxicon42, 915–931 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Montecucco, C., Gutierrez, J. M. & Lomonte, B. Cellular pathology induced by snake venom phospholipase A2 myotoxins and neurotoxins: common aspects of their mechanisms of action. Cell Mol. Life Sci.65, 2897–2912 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saikia, D., Thakur, R. & Mukherjee, A. K. An acidic phospholipase A(2) (RVVA-PLA(2)-I) purified from Daboia russelli venom exerts its anticoagulant activity by enzymatic hydrolysis of plasma phospholipids and by non-enzymatic inhibition of factor Xa in a phospholipids/Ca(2+) independent manner. Toxicon57, 841–850 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sunagar, K. & Reeks, B. G. in Venomous Reptiles and Their Toxins: Evolution, Pathophysiology and Biodiscovery (ed. Fry, B.) 327–324 (Oxford University Press, 2015).

- 16.Alangode, A., Reick, M. & Reick, M. Sodium oleate, arachidonate, and linoleate enhance fibrinogenolysis by Russell’s viper venom proteinases and inhibit FXIIIa; a role for phospholipase A(2) in venom induced consumption coagulopathy. Toxicon186, 83–93 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cortelazzo, A. et al. Effects of snake venom proteases on human fibrinogen chains. Blood Transfus.8, s120–s125 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lu, Q., Clemetson, J. M. & Clemetson, K. J. Snake venoms and hemostasis. J. Thromb. Haemost.3, 1791–1799 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Serrano, S. M. The long road of research on snake venom serine proteinases. Toxicon62, 19–26 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Trabi, M. & Jackson, B. G. in Venomous Reptiles and Their Toxins: Evolution, Pathophysiology and Biodiscovery (ed. Fry, B. G) 261–266 (Oxford University Press, 2015).

- 21.Rudresha, G. V. et al. Echis carinatus snake venom metalloprotease-induced toxicities in mice: Therapeutic intervention by a repurposed drug, Tetraethyl thiuram disulfide (Disulfiram). PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis.15, e0008596 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gutierrez, J. M. et al. Hemorrhage caused by snake venom metalloproteinases: a journey of discovery and understanding. Toxins (Basel)8, 93 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yamashita, K. M. et al. Bothrops jararaca venom metalloproteinases are essential for coagulopathy and increase plasma tissue factor levels during envenomation. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis.8, e2814 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Priyankara, S. et al. Mild venom-induced consumption coagulopathy associated with thrombotic microangiopathy following a juvenile Russell’s viper (Daboia russelii) envenoming: a case report. Toxicon212, 8–10 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang, Y. et al. Exploration of the inhibitory potential of varespladib for snakebite envenomation. Molecules23, 2 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bulfone, T. C. et al. Developing small molecule therapeutics for the initial and adjunctive treatment of snakebite. J. Trop. Med. 2018, 4320175 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Layfield, H. J. et al. Repurposing cancer drugs batimastat and marimastat to inhibit the activity of a group I Metalloprotease from the Venom of the Western Diamondback Rattlesnake, Crotalus atrox. Toxins (Basel)12 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Lewin, M. R. et al. Delayed LY333013 (Oral) and LY315920 (Intravenous) reverse severe neurotoxicity and rescue juvenile pigs from Lethal Doses of Micrurus fulvius (Eastern Coral Snake) Venom. Toxins (Basel)10 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Rucavado, A. et al. Inhibition of local hemorrhage and dermonecrosis induced by Bothrops asper snake venom: effectiveness of early in situ administration of the peptidomimetic metalloproteinase inhibitor batimastat and the chelating agent CaNa2EDTA. Am. J. Trop. Med Hyg.63, 313–319 (2000). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chowdhury, A. et al. The relative efficacy of chemically diverse small-molecule enzyme-inhibitors against anticoagulant activities of African Spitting Cobra (Naja Species) Venoms. Front Immunol.12, 752442 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Clare, R. H. et al. Small molecule drug discovery for neglected tropical snakebite. Trends Pharm. Sci.42, 340–353 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Albulescu, L. O. et al. A therapeutic combination of two small molecule toxin inhibitors provides broad preclinical efficacy against viper snakebite. Nat. Commun.11, 6094 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nicholls, S. J. et al. Varespladib and cardiovascular events in patients with an acute coronary syndrome: the VISTA-16 randomized clinical trial. JAMA311, 252–262 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sparano, J. A. et al. Randomized phase III trial of marimastat versus placebo in patients with metastatic breast cancer who have responding or stable disease after first-line chemotherapy: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group trial E2196. J. Clin. Oncol.22, 4683–90 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lewin, M. et al. Varespladib (LY315920) appears to be a potent, broad-spectrum, inhibitor of snake venom Phospholipase A2 and a possible pre-referral treatment for envenomation. Toxins (Basel)8 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Wang, Y. et al. Correction: Wang et al. Exploration of the inhibitory potential of varespladib for snakebite envenomation. Molecules23, 391 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Howes, J. M., Theakston, R. D. & Laing, G. D. Neutralization of the haemorrhagic activities of viperine snake venoms and venom metalloproteinases using synthetic peptide inhibitors and chelators. Toxicon49, 734–739 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Arias, A. S., Rucavado, A. & Gutierrez, J. M. Peptidomimetic hydroxamate metalloproteinase inhibitors abrogate local and systemic toxicity induced by Echis ocellatus (saw-scaled) snake venom. Toxicon132, 40–49 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hall, S. R. et al. Repurposed drugs and their combinations prevent morbidity-inducing dermonecrosis caused by diverse cytotoxic snake venoms. Nat. Commun.14, 7812 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Senji Laxme, R. R. et al. Biogeographic venom variation in Russell’s viper (Daboia russelii) and the preclinical inefficacy of antivenom therapy in snakebite hotspots. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis.15, e0009247 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rashmi, U. et al. Remarkable intrapopulation venom variability in the monocellate cobra (Naja kaouthia) unveils neglected aspects of India’s snakebite problem. J. Proteom.242, 104256 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Attarde, S. et al. The preclinical evaluation of a second-generation antivenom for treating snake envenoming in India. Toxins (Basel)14 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Kalita, B. et al. Proteomic analysis and immuno-profiling of eastern India Russell’s viper (Daboia russelii) venom: correlation between rvv composition and clinical manifestations post rv Bite. J. Proteome Res17, 2819–2833 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Senji Laxme, R. R. et al. From birth to bite: the evolutionary ecology of India’s medically most important snake venoms. BMC Biol.22, 161 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Patra, A., Chanda, A. & Mukherjee, A. K. Quantitative proteomic analysis of venom from Southern India common krait (Bungarus caeruleus) and identification of poorly immunogenic toxins by immune-profiling against commercial antivenom. Expert Rev. Proteom.16, 457–469 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Deka, A. et al. Proteomics of Naja kaouthia venom from North East India and assessment of Indian polyvalent antivenom by third generation antivenomics. J. Proteom.207, 103463 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Khochare, S. et al. Fangs in the ghats: preclinical insights into the medical importance of pit vipers from the Western Ghats. Int. J. Mol. Sci.24 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Tan, C. H., Lingam, T. M. C. & Tan, K. Y. Varespladib (LY315920) rescued mice from fatal neurotoxicity caused by venoms of five major Asiatic kraits (Bungarus spp.) in an experimental envenoming and rescue model. Acta Trop.227, 106289 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bradford, M. M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem.72, 248–254 (1976). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chowdhury, M. A., Miyoshi, S. & Shinoda, S. Purification and characterization of a protease produced by Vibrio mimicus. Infect. Immun.58, 4159–4162 (1990). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mora-Obando, D. et al. Synergism between basic Asp49 and Lys49 phospholipase A2 myotoxins of viperid snake venom in vitro and in vivo. PLoS ONE9, e109846 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hiremath, V. et al. Differential action of medically important Indian BIG FOUR snake venoms on rodent blood coagulation. Toxicon110, 19–26 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schneider, C. A., Rasband, W. S. & Eliceiri, K. W. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat. Methods9, 671–675 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Saganuwan, S. A. The new algorithm for calculation of median lethal dose (LD(50)) and effective dose fifty (ED(50)) of Micrarus fulvius venom and anti-venom in mice. Int J. Vet. Sci. Med. 4, 1–4 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.(WHO), W.H.O. World Health Organisation Guidelines for the Production, Control and Regulation of Snake Antivenom Immunoglobulins (World Health Organisation, 2018).

- 56.Finney, D. J. Probit Analysis 3rd edn. xv + 333 (Cambridge University Press, 1971).

- 57.Rogalski, A. et al. Differential procoagulant effects of saw-scaled viper (Serpentes: Viperidae: Echis) snake venoms on human plasma and the narrow taxonomic ranges of antivenom efficacies. Toxicol. Lett.280, 159–170 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Still, K. B. M. et al. Multipurpose HTS coagulation analysis: assay development and assessment of coagulopathic snake venoms. Toxins (Basel)9, (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 59.Senji Laxme, R. R. et al. The Middle Eastern Cousin: comparative venomics of Daboia palaestinae and Daboia russelii. Toxins (Basel)14, (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 60.Pla, D. et al. Phylovenomics of Daboia russelii across the Indian subcontinent. Bioactivities and comparative in vivo neutralization and in vitro third-generation antivenomics of antivenoms against venoms from India, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka. J. Proteom.207, 103443 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Menzies, S. K. et al. In vitro and in vivo preclinical venom inhibition assays identify metalloproteinase inhibiting drugs as potential future treatments for snakebite envenoming by Dispholidus typus. Toxicon X14, 100118 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Knudsen, C. et al. Novel snakebite therapeutics must be tested in appropriate rescue models to robustly assess their preclinical efficacy. Toxins (Basel)12, (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 63.Bartlett, K. E. et al. Dermonecrosis caused by a spitting cobra snakebite results from toxin potentiation and is prevented by the repurposed drug varespladib. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA121, e2315597121 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Du, T. Y. et al. Molecular dissection of cobra venom highlights heparinoids as an antidote for spitting cobra envenoming. Sci. Transl. Med. 16, eadk4802 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Williams, D. J. et al. Ending the drought: new strategies for improving the flow of affordable, effective antivenoms in Asia and Africa. J. Proteom.74, 1735–1767 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gutierrez, J. M. Global availability of antivenoms: the relevance of public manufacturing laboratories. Toxins (Basel)11 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 67.Carter, R. W. et al. The BRAVO Clinical Study Protocol: oral varespladib for inhibition of secretory Phospholipase A2 in the treatment of snakebite envenoming. Toxins (Basel)15 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 68.Lewin, M. R. et al. Varespladib in the treatment of snakebite envenoming: development history and preclinical evidence supporting advancement to clinical trials in patients bitten by venomous snakes. Toxins (Basel)14 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 69.Zhao, W. et al. Varespladib mitigates acute liver injury via suppression of excessive mitophagy on Naja atra envenomed mice by inhibiting PLA(2). Toxicon242, 107694 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Xie, C. et al. Neutralizing effects of small molecule inhibitors and metal chelators on coagulopathic viperinae snake venom toxins. Biomedicines8 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Data Availability Statement

The data used to plot all figures in this publication are provided in Supplementary Data 2.