Abstract

Background

This study aimed to investigate the associations of functional performance, sarcopenia, and components of sarcopenia with the onset of chronic kidney disease (CKD), while also determining the optimal predictive factor.

Methods

This observational multicenter study included 8,647 community-dwelling adults. Activities of daily living (ADL) scale, physical performance, and sarcopenia were assessed at baseline, and participants were followed to track CKD incidents. The discriminatory performance and cutoffs of ADL and other indices for predicting CKD onset were evaluated. Multivariable-adjusted logistic regression models were employed to analyze the association of ADL with CKD occurrence.

Results

There were 4,681 women and 3,966 men (median age = 57.0 years). Over a 7-year follow-up, 940 CKD incidents occurred. Optimal thresholds for left handgrip strength, right handgrip strength, the 5-time chair stand test, appendicular skeletal muscle index, and ADL to predict CKD onset were established at 35.2 kg, 30.9 kg, 10.4 seconds, 7.3 kg/m,2 and 1 for men; and 16.1 kg, 30.9 kg, 12.8 seconds, 6.3 kg/m,2 and 1 for women, respectively. Among all factors investigated, the ADL score was optimal to predict CKD onset in both men (area under the curve = 0.546; 95% CI, 0.528-0.564) and women (area under the curve = 0.559; 95% CI, 0.538-0.581). Functional performance decline (ADL score ≥1) demonstrated an independent and dose-dependent association with CKD (OR = 1.841; 95% CI, 1.446-2.329; P for trend < 0.001).

Limitations

The use of an anthropometric equation to estimate skeletal muscle mass may not be as precise as other methods. Additionally, the observational nature of the study and reliance on self-reported CKD data may lead to potential confounding, misclassification, and reverse causality, requiring further validation through studies with laboratory-confirmed CKD events and larger, more diverse populations.

Conclusions

The ADL score indicated that functional performance is superior to sarcopenia and its components in predicting the onset of CKD in middle-aged and older Chinese adults. These findings may facilitate the prevention and management of CKD.

Index Words: Activities of daily living, functional performance, sarcopenia, chronic kidney disease, cohort study

Plain-Language Summary

This study looked at how physical function, sarcopenia (loss of muscle mass and strength), and related factors might predict the development of chronic kidney disease (CKD). This study followed over 8,600 adults for 7 years and found that declines in daily functioning—measured by an activities of daily living score—were linked to an increased risk of CKD. Among several factors studied, the activities of daily living score was the best predictor of CKD onset. The study shows that monitoring physical performance, especially the ability to perform everyday tasks, could help identify people at higher risk for CKD. This insight may improve early detection and prevention strategies, particularly for middle-aged and older adults, helping reduce the burden of CKD in the community.

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a highly prevalent condition characterized by the persistent alterations in kidney structure or function with health implications.1 The global prevalence of CKD is 7%-12%, which can vary significantly across different regions.1 In China, large-scale surveys have reported a CKD prevalence ranging from 8.2% to 10.8% in the general population.2,3 Chronic kidney disease can progress to end-stage kidney disease despite optimal treatment and is associated with an increased burden of cardiovascular diseases, other health issues, and mortality.4 There exists a crucial imperative for early diagnosis and timely intervention to impede the progression of CKD.5

Identifying the risk factors or underlying causes of CKD, especially those that are modifiable, is essential for optimal management and is recommended by current guidelines.6 Various factors have been suggested to contribute to the pathogenesis of CKD, such as low birthweight,7 genetic factors,8 obesity,9 infectious diseases,10 diabetes,11 inappropriate medication use,12 and aging.13 Among these, aging-related conditions, such as functional disability and loss of muscle mass/function, on the onset of CKD have recently emerged as topics of growing medical and public health concerns worldwide.9,14,15 Age-related loss of skeletal muscle mass, along with loss of muscle strength or reduced physical performance, collectively known as sarcopenia, is associated with an increased likelihood of multiple adverse health outcomes.16 Patients with CKD have one of the highest prevalences of muscle wasting disorders.17 Furthermore, the progression of kidney disease itself can further exacerbate muscle wasting disorders.17 A randomized controlled study has shown that exercise training in older adults with advanced CKD is safe and is associated with functional improvements.18 These findings underscore the efficacy of intervening in muscle and functional loss to improve clinical outcomes in patients with CKD.

However, these lines of evidence mainly originate from clinical settings involving patients who have already developed CKD17,19,20 or from studies conducted in Western populations.20, 21, 22 It remains largely unknown whether the decline in functional performance and the loss of muscle, as potentially modifiable factors, can predict the future onset of CKD in middle-aged and older Chinese adults. This study specifically focused on evaluating the efficacy of scale-based functional performance scores, sarcopenia, and its components in predicting the onset of CKD. This work aimed to provide evidence to better understand the etiology of CKD and to help develop generalizable prevention algorithms for CKD.

Methods

Study Design and Population

This was an observational cohort study. Participants were enrolled from an ongoing nationally representative longitudinal survey in China, the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS).23 The CHARLS project employs a structured questionnaire to collect high-quality data through in-person interviews from a nationally representative sample of Chinese adults aged 45 years and older. The questionnaire includes standardized assessments of sociodemographic and lifestyle factors, and health-related information. In 2011, the CHARLS study recruited participants from 10,257 households located in 150 counties or districts and 450 villages across 28 provinces in China. Follow-up surveys were conducted every 2 years after the baseline survey. The collected data were weighted to ensure that the survey sample accurately represented the national population. More comprehensive information regarding the study design of CHARLS has been published.24

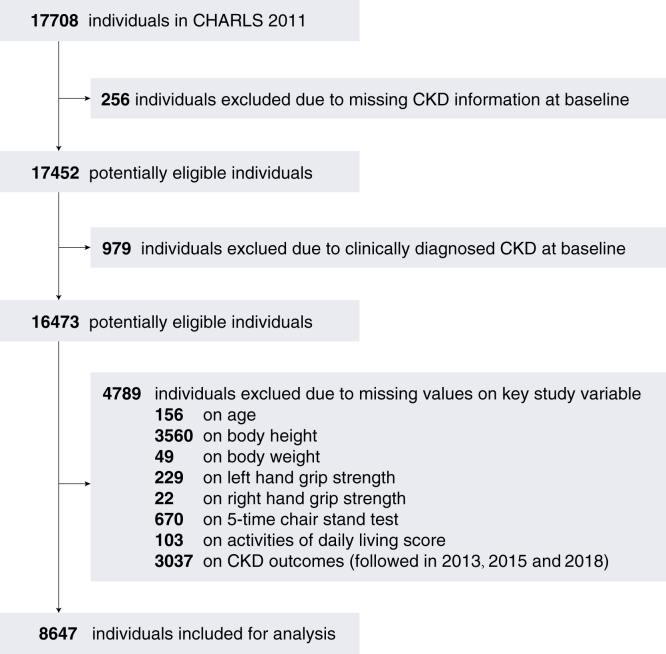

In this study, we conducted a retrospective analysis of data from the CHARLS surveys conducted in 2011, 2013, 2015, and 2018. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) individuals aged 45 and above at baseline; (2) those with available data on activities of daily living (ADL) score, variables used for diagnosing sarcopenia, and CKD status; and (3) individuals without clinically diagnosed CKD at baseline. Exclusion criteria included: (1) missing data on CKD status at baseline; (2) individuals with clinically diagnosed CKD at baseline; (3) missing data on key study variables such as age, body height, body weight, sarcopenia-related variables, and ADL; and (4) missing data on CKD outcomes. A flowchart illustrating the inclusion of subjects is provided in Fig 1.

Figure 1.

A flowchart of the subject inclusion. CHARLS, the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study; CKD, chronic kidney disease.

The research protocol received approval from the ethical review committee of Peking University (approval number: IRB00001052-11015), and all participants provided informed consent. The procedures involving human participants adhered to the principles outlined in the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its subsequent amendments, or equivalent ethical standards, and the ethical standards set by the institutional or national research committee. This study was conducted after the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines.

Exposure

The ADL refers to the routine activities that individuals typically carry out daily without requiring assistance, and it is widely used as a measure of functional performance.25 In this study, functional performance was evaluated using a 6-item ADL scale, which comprised: “Do you have some difficulty with bathing?”, “Do you have some difficulty with dressing?”, “Do you have some difficulty with eating?”, “Do you have some difficulty with getting in and out of bed?”, “Do you have some difficulty with using the toilet?”, and “Do you have some difficulty with controlling urination and defecation?”. A response of "yes" to any of these items was assigned a score of 1 point. The total ADL score was analyzed as continuous, binary (≥1 vs 0), and ternary (0, 1, and ≥2) variables in statistical analysis.

Sarcopenia was retrospectively defined based on the 2019 consensus update of the Asian working group for sarcopenia for Asians.16 Sarcopenia is diagnosed as low appendicular skeletal muscle (ASM) mass (low appendicular skeletal muscle index, men < 7.0 kg/m2 or women < 5.4 kg/m2) plus low muscle strength (low handgrip strength [HGS], men < 28 kg or women < 18 kg)16 or reduced physical performance (5-time chair stand test, with a completion time of ≥12 seconds indicating low physical performance). In terms of severity grading: low ASM plus low muscle strength or low physical performance indicates the presence of sarcopenia; low ASM plus low muscle strength and low physical performance indicates the presence of severe sarcopenia. The ASM (kg) was calculated retrospectively using an anthropometric equation previously validated for use in Chinese populations26 and subsequently adjusted for height in meters squared to obtain the ASM mass index (ASMI, kg/m2). Body weight and height were measured using a stadiometer and a digital floor scale, respectively, to the nearest 0.1 cm and 0.1 kg. Handgrip strength (kg) was measured in the dominant hand and nondominant hand using a dynamometer (Model: YuejianTM WL-1000, Nantong Yuejian Physical Measurement Instrument Co, Ltd).24 Individuals were asked to squeeze the dynamometer using their maximum strength. Additional detailed information about the definitions of sarcopenia components in the CHARLS survey can be found in previous researches.27

Follow-Up and Main Outcome

We analyzed the follow-up data in 2013, 2015, and 2018 after the baseline recruitment in 2011. The main outcome of this study was defined as the new onset of CKD during the entire follow-up period (2011-2018). The CKD events were assessed using the following question: “Have you been informed by a doctor that you have been diagnosed with a kidney problem?” Individuals who answered 'yes' to this question were classified as having CKD, as the question indicated that the kidney disease had been clinically diagnosed and confirmed by a physician. Previous studies have shown that self-reported history of chronic diseases is reliable.28

Covariates

The baseline characteristics of the study population were obtained by trained researchers using a structured questionnaire. Social-demographic factors included age, sex, marital status, residency (rural vs urban), drinking, smoking, education level (elementary school and below, secondary school, and college and above). Health-related factors included body height (cm), body weight (kg), body mass index (BMI, kg/m2), smoking (yes vs no), drinking status (yes vs no), blood pressure (systolic and diastolic, mm Hg), comorbidities (hypertension, diabetes, and heart disease), and use of medications (antihypertension, antidiabetes, and lipid-lowering). The BMI was also categorized as underweight (< 18.5 kg/m2), normal (18.5 to < 24 kg/m2), overweight (24 to < 28 kg/m2), or obese (≥28 kg/m2) according to Chinese recommendations.29 In the baseline survey in 2011, a subgroup of 11,847 individuals underwent measurements of metabolic biomarkers, such as serum urea nitrogen, serum creatinine, uric acid, and cystatin C. The baseline estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was retrospectively calculated using the Chronic Kidney Disease-Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) equation, which estimates eGFR via serum creatinine level, age, race, and sex.30

Statistical Analysis

Continuous data are presented as medians (25th percentile and 75th percentile) and were compared using a nonparametric Wilcoxon’s rank-sum test. Categorical data were expressed as numbers (percentages) and compared using a χ2 test. Between-variable correlations were assessed using Spearman’s rank correlation analysis. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were utilized to determine optimal cutoffs for various variables in predicting CKD by maximizing the Youden index (sensitivity + specificity −1). Area under the curve (AUC) along with a 95% confidence interval (CI) was used to evaluate and compare the predictive performance of the variables. Delong’s test was employed to compare the differences between correlated ROC curves. Integrated discrimination improvement (IDI) and continuous net reclassification improvement were used to further assess the discriminatory performance of different predictors. AUC calculations involved 1000 iterations of bootstrap resampling, while IDI and continuous net reclassification improvement were adjusted with 1000 iterations of perturbation-resampling to obtain unbiased estimates.

The associations between functional performance categories and the onset of CKD were evaluated using multivariable logistic regressions. Odds ratios (OR) with 95% CI were calculated to estimate the effects. Incremental models were developed with increasing numbers of covariates. Sensitivity analyses were conducted to test the time-dependent robustness of the logistic regression models by assessing the onset of CKD at the first wave of follow-up (baseline in 2011 and follow-up in 2013) or the first 2 waves of follow-up (baseline in 2011, 2 waves of follow-up in 2013 and 2015). Subgroup analyses were performed in different strata of the adjusting variables to evaluate modification of the associations observed in the overall population and to determine the applicability of functional performance across different subgroups. Multiplicative interactions were tested by adjusting the cross-product terms of the ADL and other covariates. Covariates showing statistically significant multiplicative interactions (P < 0.05) were considered potential effect modifiers. All tests were 2-sided, and significance was set at P < 0.05. The analyses were conducted using R (version 4.3.1, foundation for statistical computing).

Results

Subject Inclusion and Cohort Overview

Among the 17,708 baseline subjects studied, 256 subjects lacking CKD information and 979 subjects with clinically confirmed CKD at baseline were excluded. In addition, 4,798 individuals were excluded because of missing key study variables necessary for analysis. This left 8,647 individuals for formal analysis. There were 4,681 women and 3,966 men, with a median age of 57.0 years. Sarcopenia was diagnosed in 884 (10.2%) individuals, and 1,123 (13.0%) subjects exhibited an abnormal ADL score. Over a 7-year follow-up period, 940 CKD incidents were recorded (with 138, 510, and 940 incidents identified in 2013, 2015, and 2018, respectively). Detailed baseline characteristics of the study cohort categorized by sex are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of the Study Population by Sex

| Characteristicsa | Overall (n = 8,647) | Women (n = 4,681) | Men (n = 3,966) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 57.0 (50.0-63.0)b | 56.0 (49.0-63.0) | 58.0 (52.0, 64.0) |

| Sex, male | 3.966 (45.9)c | 0 (0.0) | 3,966 (100.0) |

| Marital status, married (vs others) | 7,402 (85.6) | 3,856 (82.4) | 3,546 (89.4) |

| Residency, rural area (vs urban) | 5,737 (66.3) | 3,090 (66.0) | 2,647 (66.7) |

| Drinking | 2,854 (33.0) | 563 (12.0) | 2,291 (57.8) |

| Smoking | 2,620 (30.4) | 265 (5.7) | 2,355 (59.6) |

| Education level, n (%) | |||

| Elementary school or below | 7,801 (90.2) | 4,408 (94.2) | 3,393 (85.6) |

| Secondary school | 763 (8.8) | 251 (5.4) | 512 (12.9) |

| College or above | 83 (1.0) | 22 (0.5) | 61 (1.5) |

| Body height, cm | 1.6 (1.5-1.6) | 1.5 (1.5-1.6) | 1.6 (1.6-1.7) |

| Body weight, kg | 58.0 (51.3-65.9) | 55.6 (48.9-63.1) | 61.0 (54.3-69.0) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 23.2 (20.9-25.8) | 23.7 (21.4, 26.4) | 22.6 (20.6-25.1) |

| BMI category, n (%) | |||

| Underweight | 517 (6.0) | 295 (6.3) | 222 (5.6) |

| Normal | 4,576 (52.9) | 2,183 (46.6) | 2,393 (60.3) |

| Overweight | 2,547 (29.5) | 1,521 (32.5) | 1,026 (25.9) |

| Obese | 1,007 (11.6) | 682 (14.6) | 325 (8.2) |

| Blood pressure, mm Hg | |||

| Systolic | 125.5 (113.0-140.0) | 124.5 (112.0-140.0) | 126.0 (114.5-139.5) |

| Diastolic | 74.0 (66.5-82.5) | 73.5 (66.5-82.0) | 75.0 (67.0-83.0) |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | |||

| Hypertension | 2,021 (23.5) | 1,172 (25.1) | 849 (21.5) |

| Diabetes | 471 (5.5) | 274 (5.9) | 197 (5.0) |

| Heart disease | 892 (10.3) | 555 (11.9) | 337 (8.5) |

| Use of medications | |||

| Hypertension medications, yes | 1,425 (16.5) | 842 (18.1) | 583 (14.8) |

| Diabetes medications, yes | 262 (3.1) | 151 (3.3) | 111 (2.8) |

| Lipid-lowering medications, yes | 344 (4.0) | 210 (4.6) | 134 (3.4) |

| Serum urea nitrogen, mg/dL | 15.1 (12.5-18.2) | 14.4 (12.1-17.3) | 15.9 (13.3-19.1) |

| Serum creatinine, mg/dL | 0.7 (0.6-0.9) | 0.7 (0.6-0.8) | 0.9 (0.8-1.0) |

| Uric acid, mg/dL | 4.2 (3.5-5.1) | 3.8 (3.3-4.5) | 4.8 (4.1-5.6) |

| Cystatin C, mg/L | 1.0 (0.9-1.1) | 0.9 (0.8-1.0) | 1.0 (0.9-1.2) |

| eGFR, mL/min/1.73 m2 | 90.9 (78.8-104.8) | 90.3 (78.1-103.4) | 92.1 (79.4-106.9) |

| Left hand grip strength, kg | 30.0 (24.0-37.5) | 25.0 (20.5-30.0) | 37.5 (32.0-43.0) |

| Right hand grip strength, kg | 31.0 (25.0-39.5) | 26.5 (22.0-31.0) | 39.5 (33.0-45.0) |

| HGS, normal | 7,291 (84.3) | 3,940 (84.2) | 3,351 (84.5) |

| Five-time chair stand test, s | 9.9 (8.0-12.3) | 10.3 (8.3-12.8) | 9.4 (7.6-11.6) |

| Physical performance, normal | 6,261 (72.4) | 3,176 (67.8) | 3,085 (77.8) |

| ASMI, kg/m2 | 6.8 (5.9-7.6) | 6.0 (5.5-6.6) | 7.6 (7.1-8.1) |

| ASMI, normal | 6,910 (79.9) | 3,627 (77.5) | 3,283 (82.8) |

| Sarcopenia, grade, n (%) | |||

| No sarcopenia | 7,763 (89.8) | 4,156 (88.8) | 3,607 (90.9) |

| Sarcopenia | 653 (7.6) | 368 (7.9) | 285 (7.2) |

| Severe sarcopenia | 231 (2.7) | 157 (3.4) | 74 (1.9) |

| Sarcopenia, binary, yes | 884 (10.2) | 525 (11.2) | 359 (9.1) |

| ADL, continuous | 0.0 (0.0-0.0) | 0.0 (0.0-0.0) | 0.0 (0.0-0.0) |

| ADL, binary, ≥1 versus 0 | 1,123 (13.0) | 699 (14.9) | 424 (10.7) |

| CKD onset during 2011-2018 | 940 (10.9) | 439 (9.4) | 501 (12.6) |

Abbreviations: ADL, activities of daily living score; ASMI, appendicular skeletal muscle mass index; BMI, body mass index; CKD, chronic kidney disease; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HGS, handgrip strength.

Missing data: smoking = 16, systolic blood pressure = 59, diastolic blood pressure = 59, hypertension = 34, diabetes = 63, heart disease = 26, hypertension medications = 35, diabetes medications = 65, lipid-lowering medications = 152, serum urea nitrogen = 2,092, serum creatinine = 2,106 and cystatin C = 3,781.

Median (interquartile range), all such values.

Number (percentage), all such values.

Correlation Analysis

Sex-specific correlations between the ADL score and sarcopenia, and its components, are shown in Fig S1. Similar patterns were observed in both women and men: ADL was positively correlated with sarcopenia and chair stand test time (both P < 0.001), whereas it was negatively correlated with right HGS, left HGS, and ASMI (all P < 0.001).

Cutoff Values and Predictive Performance of Different Indicators by Sex

For men, the optimal cutoff values for left HGS, right HGS, 5-time chair stand test, ASMI, and ADL were 35.2 kg, 30.9 kg, 10.4 seconds, 7.3 kg/m2, and 1, respectively. Corresponding cutoffs for women were 16.1 kg, 30.9 kg, 12.8 seconds, 6.3 kg/m2, and 1 for the same indicators (Figs S2 and S3).

The predictive performance of the ADL score, sarcopenia, and its components in predicting the onset of CKD was statistically compared (Table 2). Among men, the ADL score demonstrated the highest performance (AUC = 0.546; 95% CI, 0.528-0.564) in predicting CKD compared with other investigated indicators. Delong’s method statistical tests showed that the ADL score had a greater predictive value compared with HGS (binary), chair stand test (binary), ASMI, ASMI (binary), sarcopenia severity, and sarcopenia (all P < 0.05), but similar performance to left HGS, right HGS, and chair stand test (all P > 0.05). The IDI and NRI analyses yielded consistent results, indicating that the ADL score had the optimal predictive value among all the indicators examined. Similar results were observed for women, with the ADL score demonstrating the highest performance in predicting the onset of CKD (AUC = 0.559; 95% CI, 0.538-0.581). Consequently, the ADL score was selected for future analysis.

Table 2.

Diagnostic Performance of the Sarcopenia, Sarcopenia Components and Functional Performance on Onset of Chronic Kidney Disease

| Parameter | Model Diagnostic Performance |

Inter-Model Comparison on Discrimination Performance |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUC (95% CI) | Cutoff | Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV | P-AUC | IDI (95% CI) | P-IDI | NRI (95% CI) | P-NRI | |

| Men (n = 3,966) | |||||||||||

| Left HGS, kg | 0.529 (0.502-0.557) | 35.2 | 0.459 | 0.595 | 0.141 | 0.884 | 0.28 | −0.012 (0.017 to −0.007) | <0.001 | −0.086 (0.119 to −0.053) | <0.001 |

| Right HGS, kg | 0.532 (0.505-0.559) | 30.9 | 0.226 | 0.832 | 0.163 | 0.881 | 0.33 | −0.012 (0.017 to −0.007) | <0.001 | −0.086 (0.119 to −0.053) | <0.001 |

| HGS, low | 0.520 (0.502-0.538) | Positive | 0.190 | 0.850 | 0.154 | 0.879 | <0.001 | −0.012 (0.017 to −0.007) | <0.001 | −0.086 (0.119 to −0.053) | <0.001 |

| Chair stand test, s | 0.535 (0.507-0.563) | 10.4 | 0.449 | 0.649 | 0.156 | 0.891 | 0.48 | −0.012 (0.013 to −0.008) | <0.001 | −0.085 (0.118 to −0.052) | <0.001 |

| Chair stand, low | 0.527 (0.506-0.548) | Positive | 0.269 | 0.785 | 0.153 | 0.881 | <0.001 | −0.011 (0.016 to −0.006) | <0.001 | −0.086 (0.119 to −0.053) | <0.001 |

| ASMI, kg/m2 | 0.505 (0.478-0.532) | 7.3 | 0.369 | 0.675 | 0.135 | 0.878 | 0.01 | −0.013 (0.018 to −0.008) | <0.001 | −0.086 (0.119 to −0.053) | <0.001 |

| ASMI, low | 0.501 (0.483-0.519) | Positive | 0.174 | 0.828 | 0.127 | 0.874 | <0.001 | −0.013 (0.018 to −0.008) | <0.001 | −0.086 (0.119 to −0.053) | <0.001 |

| Sarcopenia, grade | 0.515 (0.500-0.529) | Positive | 0.116 | 0.913 | 0.162 | 0.877 | 0.006 | −0.012 (0.017 to −0.007) | <0.001 | −0.086 (0.119 to −0.053) | <0.001 |

| Sarcopenia, yes | 0.514 (0.500-0.529) | Positive | 0.116 | 0.913 | 0.162 | 0.877 | 0.006 | −0.012 (0.017 to −0.007) | <0.001 | −0.086 (0.119 to −0.053) | <0.001 |

| ADL, binary | 0.546 (0.528-0.564) | Positive | 0.188 | 0.905 | 0.222 | 0.885 | 0.92 | −0.003 (0.006 to −0.001) | 0.006 | 0.002 (0.016 to 0.019) | 0.84 |

| ADL score | 0.546 (0.528-0.564) | 1 | 0.188 | 0.905 | 0.222 | 0.885 | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Women (n = 4,681) | |||||||||||

| Left HGS, kg | 0.523 (0.495-0.552) | 16.1 | 0.141 | 0.899 | 0.127 | 0.910 | 0.066 | −0.013 (−0.017 to −0.008) | <0.001 | −0.070 (−0.100 to −0.040) | <0.001 |

| Right HGS, kg | 0.538 (0.510-0.567) | 30.9 | 0.806 | 0.270 | 0.103 | 0.931 | 0.20 | −0.012 (−0.016 to −0.008) | <0.001 | −0.070 (−0.100 to −0.040) | <0.001 |

| HGS, low | 0.517 (0.498-0.536) | Positive | 0.189 | 0.845 | 0.112 | 0.910 | <0.001 | −0.013 (−0.013 to −0.009) | <0.001 | −0.070 (−0.100 to −0.040) | <0.001 |

| Chair stand test, s | 0.534 (0.505-0.563) | 12.8 | 0.317 | 0.760 | 0.120 | 0.915 | 0.15 | −0.013 (−0.017 to −0.008) | <0.001 | −0.066 (−0.097 to −0.036) | <0.001 |

| Chair stand, low | 0.529 (0.505-0.552) | Positive | 0.374 | 0.684 | 0.109 | 0.913 | <0.001 | −0.013 (−0.017 to −0.008) | <0.001 | −0.070 (−0.100 to −0.040) | <0.001 |

| ASMI, kg/m2 | 0.529 (0.505-0.552) | 6.3 | 0.403 | 0.647 | 0.106 | 0.913 | 0.038 | −0.014 (−0.018 to −0.009) | <0.001 | −0.070 (−0.100 to −0.040) | <0.001 |

| ASMI, low | 0.507 (0.487-0.527) | Positive | 0.788 | 0.227 | 0.095 | 0.912 | 0.001 | −0.014 (−0.018 to −0.009) | <0.001 | −0.070 (−0.100 to −0.040) | <0.001 |

| Sarcopenia, grade | 0.507 (0.487-0.527) | Positive | 0.134 | 0.890 | 0.112 | 0.909 | <0.001 | −0.013 (−0.018 to, −0.009) | <0.001 | −0.070 (−0.100 to −0.040) | <0.001 |

| Sarcopenia, yes | 0.512 (0.496-0.529) | Positive | 0.134 | 0.890 | 0.112 | 0.909 | <0.001 | −0.013 (−0.018 to −0.009) | <0.001 | −0.007 (−0.100 to −0.040) | <0.001 |

| ADL, binary | 0.558 (0.537-0.579) | Positive | 0.255 | 0.862 | 0.160 | 0.918 | 0.23 | −0.005 (−0.007 to −0.003) | <0.001 | −0.007 (−0.100 to −0.040) | <0.001 |

| ADL score | 0.559 (0.538-0.581) | 1 | 0.255 | 0.862 | 0.160 | 0.918 | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

Abbreviations: ADL, activities of daily living score; ASMI, appendicular skeletal muscle index; AUC, area under the curve; CI, confidence interval; HGS, handgrip strength; IDI, integrated discrimination improvement; NRI, net reclassification improvement; NPV, negative predictive value; PPV, positive predictive value.

Activities of Daily Living Score Category and Clinical Characteristics

The clinical characteristics of individuals categorized by the ADL categories (≥1 vs 0) are presented in Table 3. Compared with the group with a negative ADL score (= 0), the ADL positive group (≥1) was associated with a higher value/rate of age, residency in rural area, hypertension, diabetes, heart disease, use of medications (antihypertension, antidiabetes, and lipid-lowering), serum urea nitrogen, cystatin C, chair stand test seconds, sarcopenia, and individuals with CKD, and was associated with a lower value/rate for the male sex, nonmarried marital status, drinking, smoking, education level, body height, body weight, serum creatinine, uric acid, left HGS, right HGS, normal HGS, normal physical performance, ASMI, and normal skeletal muscle. Furthermore, the BMI categories and sarcopenia severity were also different between the negative and positive ADL groups (all P < 0.05).

Table 3.

Baseline Characteristics of the Study Population by Functional Performance

| Characteristicsa | Overall (n = 8,647) | ADL negative (n = 7,524) | ADL positive (n = 1,123) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 57.0 (50.0-63.0)b | 57.0 (49.0-63.0) | 61.0 (55.0-68.0) | <0.001 |

| Sex, male | 3,966 (45.9)c | 3,542 (47.1) | 424 (37.8) | <0.001 |

| Marital status, married (vs others) | 7,402 (85.6) | 6,485 (86.2) | 917 (81.7) | <0.001 |

| Residency, rural area (vs urban) | 5,737 (66.3) | 4,889 (65.0) | 848 (75.5) | <0.001 |

| Drinking | 2,854 (33.0) | 2,546 (33.8) | 308 (27.4) | <0.001 |

| Smoking | 2,620 (30.4) | 2,334 (31.1) | 286 (25.5) | <0.001 |

| Education level, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Elementary school or below | 7,801 (90.2) | 6,723 (89.4) | 1,078 (96.0) | |

| Secondary school | 763 (8.8) | 722 (9.6) | 41 (3.7) | |

| College or above | 83 (1.0) | 79 (1.0) | 4 (0.4) | |

| Body height, cm | 1.6 (1.5-1.6) | 1.6 (1.5-1.6) | 1.6 (1.5-1.6) | <0.001 |

| Body weight, kg | 58.0 (51.3-65.9) | 58.3 (51.6-66.1) | 56.0 (48.8-64.5) | <0.001 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 23.2 (20.9-25.8) | 23.2 (21.0-25.8) | 23.0 (20.6-26.1) | 0.17 |

| BMI category, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Underweight | 517 (6.0) | 419 (5.6) | 98 (8.7) | |

| Normal | 4,576 (52.9) | 4,007 (53.3) | 569 (50.7) | |

| Overweight | 2,547 (29.5) | 2,231 (29.7) | 316 (28.1) | |

| Obese | 1,007 (11.6) | 867 (11.5) | 140 (12.5) | |

| Blood pressure, mm Hg | ||||

| Systolic | 125.5 (113.0-140.0) | 125.0 (113.0-139.5) | 126.5 (113.5-142.5) | 0.11 |

| Diastolic | 74.0 (66.5-82.5) | 74.0 (67.0-82.5) | 74.0 (65.5-82.5) | 0.061 |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | ||||

| Hypertension | 2,021 (23.5) | 1,683 (22.5) | 338 (30.2) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes | 471 (5.5) | 386 (5.2) | 85 (7.6) | 0.001 |

| Heart disease | 892 (10.3) | 710 (9.5) | 182 (16.3) | <0.001 |

| Use of medications | ||||

| Hypertension medications, yes | 1,425 (16.5) | 1,170 (15.6) | 255 (22.8) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes medications, yes | 262 (3.1) | 207 (2.8) | 55 (4.9) | <0.001 |

| Lipid-lowering medications, yes | 344 (4.0) | 272 (3.7) | 72 (6.5) | <0.001 |

| Serum urea nitrogen, mg/dL | 15.1 (12.5-18.2) | 15.0 (12.5-18.1) | 15.3 (12.7-18.7) | 0.038 |

| Serum creatinine, mg/dL | 0.7 (0.6-0.9) | 0.7 (0.6-0.9) | 0.7 (0.6-0.8) | <0.001 |

| Uric acid, mg/dL | 4.2 (3.5-5.1) | 4.3 (3.5-5.1) | 4.2 (3.5-5.0) | 0.010 |

| Cystatin C, mg/L | 1.0 (0.9-1.1) | 1.0 (0.9-1.1) | 1.0 (0.9-1.2) | <0.001 |

| eGFR, mL/min/1.73 m2 | 90.9 (78.8-104.8) | 91.1 (79.1-105.0) | 90.5 (77.5-104.1) | 0.17 |

| Left hand grip strength, kg | 30.0 (24.0-37.5) | 30.0 (24.5-38.3) | 26.0 (20.0-33.0) | <0.001 |

| Right hand grip strength, kg | 31.0 (25.0-39.5) | 32.0 (25.5-40.0) | 27.0 (21.0-34.5) | <0.001 |

| HGS, normal | 7,291 (84.3) | 6,479 (86.1) | 812 (72.3) | <0.001 |

| Five-time chair stand test, s | 9.9 [(8.0-12.3) | 9.7 (7.8-12.0) | 11.5 (9.3-14.2) | <0.001 |

| Physical performance, normal | 6,261 (72.4) | 5,635 (74.9) | 626 (55.7) | <0.001 |

| ASMI, kg/m2 | 6.8 (5.9-7.6) | 6.9 (6.0-7.6) | 6.5 (5.6-7.3) | <0.001 |

| ASMI, normal | 6,910 (79.9) | 6,106 (81.2) | 804 (71.6) | <0.001 |

| Sarcopenia, grade, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| No sarcopenia | 7,763 (89.8) | 6,869 (91.3) | 894 (79.6) | |

| Sarcopenia | 653 (7.6) | 503 (6.7) | 150 (13.4) | |

| Severe sarcopenia | 231 (2.7) | 152 (2.0) | 79 (7.0) | |

| Sarcopenia, binary, yes | 884 (10.2) | 655 (8.7) | 229 (20.4) | <0.001 |

| CKD onset during 2011-2018 | 940 (10.9) | 734 (9.8) | 206 (18.3) | <0.001 |

Abbreviations: ADL, activities of daily living score; ASMI, appendicular skeletal muscle mass index; BMI, body mass index; CKD, chronic kidney disease; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HGS, handgrip strength.

Missing data, smoking = 16, systolic blood pressure = 59, diastolic blood pressure = 59, hypertension = 34, diabetes = 63, heart disease = 26, hypertension medications = 35, diabetes medications = 65, lipid-lowering medications = 152, serum urea nitrogen = 2,092, serum creatinine = 2,106, and cystatin C = 3,781.

Median (interquartile range), all such values.

Number (percentage), all such values.

Multivariable Analysis

The results of the multivariable logistic regression model analyzing the associations between the ADL score and the onset of CKD are shown in Table 4. The ADL score was examined as a continuous variable, binary variable (≥1 vs 0), and as a categorical variable (0, 1, and ≥2). In the fully adjusted model (Model 4), the continuous ADL score showed an independent association with an increased likelihood of developing CKD in the overall population (OR = 1.258; 95% CI, 1.130-1.393). Similarly, consistent results were observed when the ADL score was analyzed as a binary variable (OR = 1.841; 95% CI, 1.446-2.329). Regarding ADL categories, individuals with moderate functional performance decline exhibited higher odds of developing CKD (OR = 1.590; 95% CI, 1.168-2.133). This association was even stronger in those with severe functional performance decline (OR = 2.274; 95% CI, 1.612-3.161). A subsequent statistical test revealed a dose-dependent relationship between ADL-represented functional performance decline and CKD incidents (P for trend < 0.001).

Table 4.

Multivariable Models of the Relationship Between Functional Performance and Chronic Kidney Disease

| Models | Overall Populationa, OR (95% CI) |

Sensitivity Analysisa, OR (95% CI) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No./events | Model 1b | Model 2c | Model 3d | Model 4e | No./events | Model 5f | No./events | Model 6g | |

| ADL, continuous | 8,647/940 | 1.293 (1.199-1.391) | 1.300 (1.203-1.401) | 1.280 (1.181-1.383) | 1.258 (1.130-1.393) | 8,647/138 | 1.298 (1.021-1.587) | 8,647/510 | 1.267 (1.107-1.436) |

| ADL, ≥1 versus 0 | 8,647/940 | 2.078 (1.751-2.457) | 2.125 (1.783-2.525) | 2.051 (1.710-2.452) | 1.841 (1.446-2.329) | 8,647/138 | 1.773 (0.992-3.020) | 8,647/510 | 1.971 (1.448-2.654) |

| ADL, severityh | |||||||||

| 0 | 7524/734 | Ref = 1 | Ref = 1 | Ref = 1 | Ref = 1 | 7524/107 | Ref = 1 | 7524/389 | Ref = 1 |

| 1 versus 0 | 690/120 | 1.948 (1.571-2.397) | 1.987 (1.599-2.452) | 1.922 (1.535-2.390) | 1.590 (1.168-2.133) | 690/19 | 1.636 (0.777-3.108) | 690/72 | 1.847 (1.257-2.649) |

| ≥ 2 versus 0 | 433/86 | 2.293 (1.780-2.924) | 2.363 (1.824-3.033) | 2.271 (1.738-2.939) | 2.274 (1.612-3.161) | 433/12 | 2.003 (0.843-4.165) | 433/49 | 2.175 (1.387-3.305) |

Abbreviations: ADL, activities of daily living; CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

Individuals with missing values of independent variable were excluded from analysis.

Model 1 is the unadjusted crude model.

Model 2 is adjusted for the age at baseline and sex.

Model 3 is adjusted for the age at baseline, sex, marital status, residence, drinking status, smoking status, body mass index, educational level, hypertension, diabetes, heart disease, use of hypertension medications, use of diabetes medications, and use of lipid-lowering medications.

Model 4 is adjusted for all variables in Model 3, plus serum urea nitrogen, serum creatinine, cystatin C, and uric acid.

Model 5 is adjusted for all covariates in Model 4, but only assessed the onset of chronic kidney disease at the first wave of follow-up (baseline in 2011, first wave of follow-up in 2013).

Model 6 is adjusted for all covariates in Model 4, but only assessed the onset of chronic kidney disease at the first 2 waves of follow-up (baseline in 2011, second wave of follow-up in 2013 and 2015).

P for trend: Model 1 < 0.001, Model 2 < 0.001, Model 3 < 0.001, Model 4 < 0.001, Model 5 = 0.039, and Model 6 < 0.001.

Sensitivity analysis was conducted by focusing only on CKD incidents occurring within the first 2 years (Model 5) or the first 4 years (Model 6) to explore the impact of elapsed time. In Model 5, the ADL score was associated with higher odds of CKD incidents when analyzed in continuous format (OR = 1.298; 95% CI, 1.021-1.587), but not in binary or ternary format. For Model 6, the associations observed in the fully adjusted model for the overall population (Model 4) remained consistent.

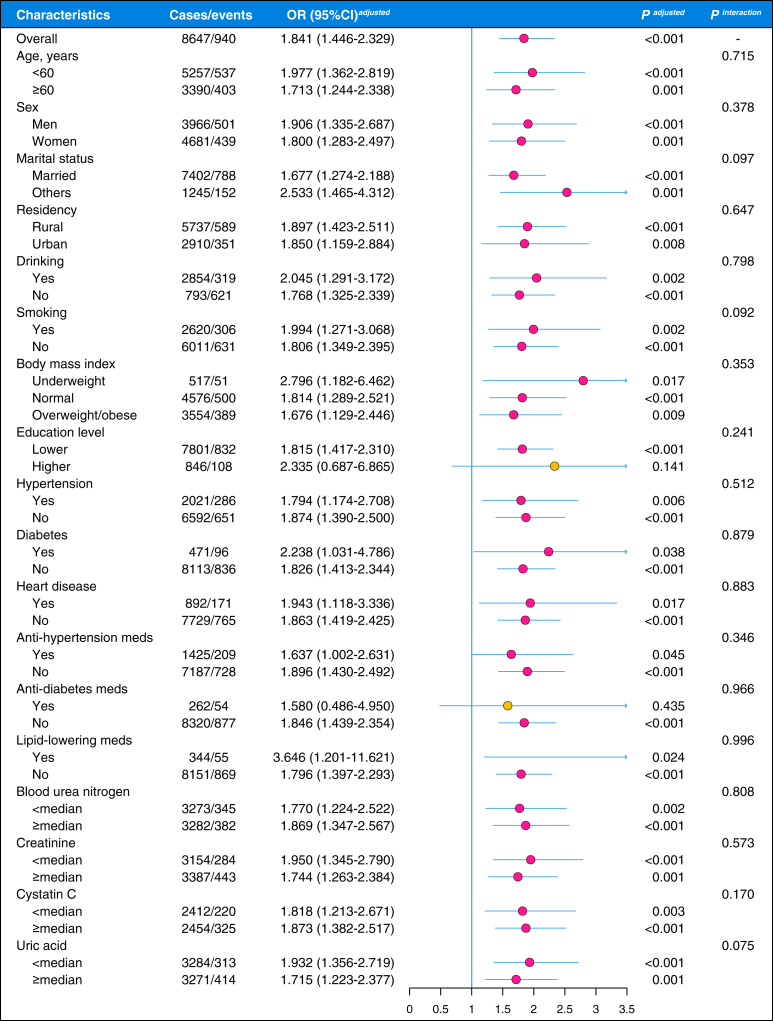

Subgroup and Interaction Analysis

The fully adjusted models were repeated in different covariate subgroups to study the effect modifications, and all covariates were statistically screened for potential interactive effects (Fig 2). Although the positive association between ADL-represented functional performance decline and CKD incidents seemed to have attenuated in subjects with higher education levels (OR = 2.335; 95% CI, 0.687-6.865) and in those using antidiabetes medications (OR = 1.580; 95% CI, 0.486-4.950), no statistical significance was observed for these interactions (all P > 0.05). In summary, the positive association between ADL-represented functional performance decline and CKD incidents is robust in different covariate subgroups.

Figure 2.

Subgroup and interaction analysis of the associations of the activities of daily living (ADL)-represented functional performance decline and onset of chronic kidney disease. OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; medians (serum urea nitrogen = 15.10 mg/dL, serum serum creatinine = 0.75 mg/dL, cystatin C = 0.97 mg/L, and uric acid = 4.25 mg/dL).

Discussion

In this report, we compared the predictive value of different functional performance and sarcopenia-related parameters for the new onset of CKD in a nationally representative multicenter cohort in China. Our findings suggest that the ADL-represented functional performance score outperforms sarcopenia and various sarcopenia components in predicting CKD incidents in middle-aged and older Chinese adults. ADL-indicated functional performance decline was independently and robustly associated with increased odds of CKD incidents during a 7-year follow-up.

The association between functional/physical performance and CKD remains controversial. A recent meta-analysis found that being physically active, as opposed to being sedentary, is associated with lower odds of CKD.21 Similarly, another study conducted in an Asian population also found that sarcopenia is linked to an increased likelihood of CKD onset.14 In contrast, other studies have reported either insignificant22,31,32 or negative associations33 in this regard. Our primary finding was consistent with some of these studies,14,21 showing that ADL-represented functional performance decline is a risk factor for CKD. The ADL used in this study consists of only 6 binary questions that can be easily obtained through in-person or telephone interviews. In contrast, a full diagnosis of sarcopenia requires a comprehensive assessment of muscle strength, muscle mass, and physical performance.16 Notably, dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry or computed tomography is necessary to measure ASM, and the assessment of physical performance needs to be supervised by trained technicians. These reasons make the ADL score much easier to implement in practical surveillance algorithms in both community and clinical settings. The ADL impairment, as an indicator of a later stage of disease, has a stronger predictive ability for incident CKD than sarcopenia. A recent study found that individuals with sarcopenia were more likely to develop new-onset CKD than those with possible sarcopenia,14 which partially supports this viewpoint. In addition, among the 7,763 individuals without sarcopenia, 894 (11.5%) still exhibited varying degrees of ADL impairment. This suggests that the predictive capacity of ADL for CKD is not solely dependent on sarcopenia but may also operate through other pathways or mechanisms. Recent evidence has shown that resistance exercise in patients with CKD could have multiple physiological benefits, such as an increase in skeletal muscle mass, reduced systemic inflammation, and improved bone health.34 However, these beneficial effects were observed in people who have already developed CKD. Randomized controlled studies are needed to determine whether interventions on functional performance could reduce the incidence of CKD in community-dwelling adults.

The mechanism underlying the results of this study warrants further discussion. The ADL are largely determined by the functioning of skeletal muscle.35 Skeletal muscles, which are widely distributed throughout the body, play a significant role in various metabolic processes.36 As the primary storage site for proteins and a central hub for glucose metabolism, muscles are crucial in systemic protein and glucose regulation.37 Studies have shown an inverse relationship between muscle mass and insulin resistance, suggesting that a reduction in muscle mass due to sarcopenia may impair the muscle’s ability to take up glucose, thereby increasing the risk of insulin resistance.37, 38, 39 Insulin resistance is considered a key factor in the development of kidney dysfunction.40 In addition, physical activity has been shown to promote the upregulation of antioxidant defense systems,41 and skeletal muscles also possess anti-inflammatory properties.42 These findings suggest that sarcopenia may contribute to an increase in systemic inflammatory responses, which are known to drive the progression of CKD.5 Further mechanistic studies are needed to clarify these issues and provide additional evidence.

Limitations

There are several limitations associated with this study that need to be acknowledged. First, the estimation of skeletal muscle mass in this study was based on an anthropometric equation.26 Although imaging-based technologies, bioimpedance analysis, or dual-energy X-ray imaging could offer a more precise measurement of muscle mass for diagnosing sarcopenia, it is important to note that good consistency was observed between the equation used and dual-energy X-ray imaging.26 Second, due to the observational nature of this study, the observed associations may not imply causation because of potential unmeasured confounding effects and the risk of reverse causality. To enhance statistical power and include as many individuals as possible for multivariable logistic regression analysis, we made a trade-off by adjusting covariates that were most pertinent to our research objectives, encompassing demographic, lifestyle, comorbidity, medication, and laboratory data. In addition, we conducted sensitivity analyses across various dimensions, such as the number of covariates, incident time of CKD, ADL format, and individual subgroups. These efforts should help mitigate the potential for reverse causality and bolster the reliability of the observed associations. Third, limited to the scope and design of the original CHARLS study, laboratory values (eg, eGFR) were only available at the baseline level. Therefore, the information on chronic diseases was self-reported, raising the possibility of misclassification of CKD onset. Although previous study has shown that self-reported history of chronic diseases is reliable28 and many CHARLS-based studies have employed this self-report approach to define chronic disease events,14,43 studies with information on serum indices-confirmed CKD events and disease stages are needed to replicate our findings. Fourth, the AUC of ADL alone in predicting CKD is relatively low. Therefore, future studies should consider incorporating additional indicators to enhance the overall predictive performance of the model. Future studies with larger sample sizes, encompassing a broader range of ethnic groups, will be essential to address these questions and replicate our findings.

In conclusion, we herein demonstrated that ADL, as a representation of functional performance, outperforms sarcopenia and its components in predicting the onset of CKD among middle-aged and older Chinese adults living in the community. The decline in functional performance is independently and strongly linked to an increased likelihood of developing CKD, and the severity of functional performance decline is proportional to the CKD incidents. These findings have implications for public health practitioners and clinicians by providing valuable insights for decision-making related to CKD prevention.

Article Information

Authors’ Full Names and Academic Degrees

Liangyu Yin, MD, PhD, Furong Li, MD, PhD, Tangli Xiao, MD, Jun Zhang, MD, Yan Li, MD, PhD, Jicong Luo, MD, Jinghong Zhao, MD, PhD, and Jiachuan Xiong, MD PhD

Authors’ Contributions

LY: conceptualization, data curation, methodology, investigation, formal analysis, funding acquisition, and supervision. FL, TX, YL, and JL: data curation and investigation. JZ: data curation, investigation, methodology, funding acquisition, and supervision. JX: methodology and investigation. Each author contributed important intellectual content during manuscript drafting or revision and accepts accountability for the overall work by ensuring that questions pertaining to the accuracy or integrity of any portion of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Support

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82304131, LYY), the Natural Science Foundation of Chongqing, China (CSTB2024NSCQ-MSX1233, LYY), the Young Doctoral Talent Incubation Program of the Xinqiao Hospital, Army Medical University (2024YQB033, LY), the Key program of the Joint Funds of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (U22A20279, JHZ) and the Key project of Chongqing technology development and application program (CSTB2023TIAD-KPX0060, JHZ).

Financial Disclosure

The authors declare that they have no relevant financial interests.

Peer Review

Received July 31, 2024. Evaluated by 2 external peer reviewers, with direct editorial input from the Statistical Editor, an Associate Editor, and the Editor-in-Chief. Accepted in revised form January 21, 2025.

Footnotes

Complete author and article information provided before references.

Figure S1: Sex-specific correlations of activities of daily living score with sarcopenia and sarcopenia components. ∗∗∗P < 0.001.

Figure S2: Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis to calculate the optimal cutoffs for difference variables to predict chronic kidney disease in men. HGS, handgrip strength; AUC, area under the curve; CST, 5-time chair stand test; ASMI, appendicular skeletal muscle mass index; ADL, activities of daily living.

Figure S3: Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis to calculate the optimal cutoffs for difference variables to predict chronic kidney disease in women. HGS, handgrip strength; AUC, area under the curve; CST, 5-time chair stand test; ASMI, appendicular skeletal muscle mass index; ADL, activities of daily living.

Contributor Information

Liangyu Yin, Email: liangyuyin1988@tmmu.edu.cn, liangyuyin1988@qq.com.

Jiachuan Xiong, Email: xiongjc@tmmu.edu.cn.

Supplementary Material

Figures S1-S3.

References

- 1.Romagnani P., Remuzzi G., Glassock R., et al. Chronic kidney disease. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017;3 doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2017.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang L., Xu X., Zhang M., et al. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease in China: results from the sixth China chronic disease and risk factor surveillance. JAMA Intern Med. 2023;183(4):298–310. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2022.6817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang L., Wang F., Wang L., et al. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease in China: a cross-sectional survey. Lancet. 2012;379(9818):815–822. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60033-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zoccali C., Mark P.B., Sarafidis P., et al. Diagnosis of cardiovascular disease in patients with chronic kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2023;19(11):733–746. doi: 10.1038/s41581-023-00747-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ruiz-Ortega M., Rayego-Mateos S., Lamas S., Ortiz A., Rodrigues-Diez R.R. Targeting the progression of chronic kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2020;16(5):269–288. doi: 10.1038/s41581-019-0248-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stevens P.E., Levin A. Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes Chronic Kidney Disease Guideline Development Work Group Members. Evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease: synopsis of the kidney disease: improving global outcomes 2012 clinical practice guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(11):825–830. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-11-201306040-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Low Birth Weight and Nephron Number Working Group The impact of kidney development on the life course: A consensus document for action. Nephron. 2017;136(1):3–49. doi: 10.1159/000457967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oliveira B., Kleta R., Bockenhauer D., Walsh S.B. Genetic, pathophysiological, and clinical aspects of nephrocalcinosis. Am J Physiol Ren Physiol. 2016;311(6):F1243–F1252. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00211.2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lu J.L., Molnar M.Z., Naseer A., Mikkelsen M.K., Kalantar-Zadeh K., Kovesdy C.P. Association of age and BMI with kidney function and mortality: a cohort study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2015;3(9):704–714. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(15)00128-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jha V., Garcia-Garcia G., Iseki K., et al. Chronic kidney disease: global dimension and perspectives. Lancet. 2013;382(9888):260–272. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60687-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tonneijck L., Muskiet M.H.A., Smits M.M., et al. Glomerular hyperfiltration in diabetes: mechanisms, clinical significance, and treatment. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;28(4):1023–1039. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2016060666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stanifer J.W., Kilonzo K., Wang D., et al. Traditional medicines and kidney disease in low- and middle-income countries: opportunities and challenges. Semin Nephrol. 2017;37(3):245–259. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2017.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Denic A., Mathew J., Lerman L.O., et al. Single-nephron glomerular filtration rate in healthy adults. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(24):2349–2357. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1614329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu T., Wu Y., Cao X., et al. Association between sarcopenia and new-onset chronic kidney disease among middle-aged and elder adults: findings from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study. BMC Geriatr. 2024;24(1):134. doi: 10.1186/s12877-024-04691-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Song Y., Liu Y.S., Talarico F., et al. Associations between differential aging and lifestyle, environment, current, and future health conditions: findings from Canadian longitudinal study on aging. Gerontology. 2023;69(12):1394–1403. doi: 10.1159/000534015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen L.K., Woo J., Assantachai P., et al. Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia. Consensus update on sarcopenia diagnosis and treatment. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2019;21:300–307. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2019.12.012. e2:2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Okamura M., Konishi M., Butler J., Kalantar-Zadeh K., von Haehling S., Anker S.D. Kidney function in cachexia and sarcopenia: facts and numbers. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2023;14(4):1589–1595. doi: 10.1002/jcsm.13260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weiner D.E., Liu C.K., Miao S., et al. Effect of long-term exercise training on physical performance and cardiorespiratory function in adults with CKD: A randomized controlled trial. Am J Kidney Dis. 2023;81(1):59–66. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2022.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nakano Y., Mandai S., Naito S., et al. Effect of osteosarcopenia on longitudinal mortality risk and chronic kidney disease progression in older adults. Bone. 2024;179 doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2023.116975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hannan M., Chen J., Hsu J., et al. Frailty and cardiovascular outcomes in adults with CKD: findings from the chronic renal insufficiency cohort (CRIC) study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2024;83(2):208–215. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2023.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kelly J.T., Su G., Zhang L., et al. Modifiable lifestyle factors for primary prevention of CKD: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2021;32(1):239–253. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2020030384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Foster M.C., Hwang S.-J., Massaro J.M., Jacques P.F., Fox C.S., Chu A.Y. Lifestyle factors and indices of kidney function in the Framingham Heart Study. Am J Nephrol. 2015;41(4-5):267–274. doi: 10.1159/000430868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lei X., Sun X., Strauss J., et al. Health outcomes and socio-economic status among the mid-aged and elderly in China: evidence from the CHARLS national baseline data. J Econ Ageing. 2014;4:59–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jeoa.2014.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhao Y., Hu Y., Smith J.P., Strauss J., Yang G. Cohort profile: the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS) Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43(1):61–68. doi: 10.1093/ije/dys203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Katz S., Ford A.B., Moskowitz R.W., Jackson B.A., Jaffe M.W. Studies of illness in the aged. Index Adl A Standardized Meas Biol Psychosoc Funct JAMA. 1963;185:914–919. doi: 10.1001/jama.1963.03060120024016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wen X., Wang M., Jiang C.-M., Zhang Y.-M. Anthropometric equation for estimation of appendicular skeletal muscle mass in Chinese adults. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2011;20(4):551–556. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gao K., Cao L.-F., Ma W.-Z., et al. Association between sarcopenia and cardiovascular disease among middle-aged and older adults: findings from the China health and retirement longitudinal study. EClinicalmedicine. 2022;44 doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.101264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Najafi F., Moradinazar M., Hamzeh B., Rezaeian S. The reliability of self-reporting chronic diseases: how reliable is the result of population-based cohort studies. J Prev Med Hyg. 2019;60(4):E349–E353. doi: 10.15167/2421-4248/jpmh2019.60.4.1118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen C., Lu F.C., Department of Disease Control Ministry of Health, PR China The guidelines for prevention and control of overweight and obesity in Chinese adults. Biomed Environ Sci. 2004;17(suppl):1–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Levey A.S., Stevens L.A., Schmid C.H., et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(9):604–612. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hawkins M., Newman A.B., Madero M., et al. TV watching, but not physical activity, is associated with change in kidney function in older adults. J Phys Act Health. 2015;12(4):561–568. doi: 10.1123/jpah.2013-0289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ramezankhani A., Tohidi M., Azizi F., Hadaegh F. Application of survival tree analysis for exploration of potential interactions between predictors of incident chronic kidney disease: a 15-year follow-up study. J Transl Med. 2017;15(1):240. doi: 10.1186/s12967-017-1346-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kanda E., Muneyuki T., Suwa K., Nakajima K. Alcohol and exercise affect declining kidney function in healthy males regardless of obesity: A prospective cohort study. PLOS One. 2015;10(8) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0134937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bishop N.C., Burton J.O., Graham-Brown M.P.M., Stensel D.J., Viana J.L., Watson E.L. Exercise and chronic kidney disease: potential mechanisms underlying the physiological benefits. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2023;19(4):244–256. doi: 10.1038/s41581-022-00675-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kirk B., Cawthon P.M., Arai H., et al. The conceptual definition of sarcopenia: Delphi consensus from the global leadership initiative in sarcopenia (GLIS) Age Ageing. 2024;53(3):afae052. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afae052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Borowik A.K., Murach K.A., Miller B.F. The expanding roles of myonuclei in adult skeletal muscle health and function. Biochem Soc Trans. 2024;52(6):1–14. doi: 10.1042/BST20241637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Son J.W., Lee S.S., Kim S.R., et al. Low muscle mass and risk of type 2 diabetes in middle-aged and older adults: findings from the KoGES. Diabetologia. 2017;60(5):865–872. doi: 10.1007/s00125-016-4196-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.DeFronzo R.A., Tripathy D. Skeletal muscle insulin resistance is the primary defect in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(suppl 2):S157–S163. doi: 10.2337/dc09-S302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nishikawa H., Asai A., Fukunishi S., Nishiguchi S., Higuchi K. Metabolic syndrome and sarcopenia. Nutrients. 2021;13(10):3519. doi: 10.3390/nu13103519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.De Cosmo S., Menzaghi C., Prudente S., Trischitta V. Role of insulin resistance in kidney dysfunction: insights into the mechanism and epidemiological evidence. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2013;28(1):29–36. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfs290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ji L.L. Antioxidant signaling in skeletal muscle: a brief review. Exp Gerontol. 2007;42(7):582–593. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2007.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nielsen S., Pedersen B.K. Skeletal muscle as an immunogenic organ. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2008;8(3):346–351. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2008.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Song Y., Zhu C., Shi B., et al. Social isolation, loneliness, and incident type 2 diabetes mellitus: results from two large prospective cohorts in Europe and East Asia and Mendelian randomization. EClinicalmedicine. 2023;64 doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2023.102236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figures S1-S3.