ABSTRACT

Background and Aims

Nowadays, the social media video‐sharing website YouTube is globally accessible and used for sharing news and information. It also serves as a tool for migraine sufferers seeking guidance about Daith piercing (DP) as a potential migraine treatment; however, shared and disseminated video content is rarely regulated and does not follow evidence‐based medicine. This study aims to investigate the content, quality, and reliability of YouTube videos on DP for the treatment of migraine.

Methods

YouTube videos were systematically searched from the video portal inception until 17th January 2024. “Daith piercing” AND “migraine” were the applied search terms. The primary outcome of interest was assessing the Global Quality Scale (GQS) and DISCERN to evaluate each video blog's quality, flow, and reliability. Secondary outcomes included the relapse time of migraine after DP, and further outcomes related to DP.

Results

In the final analysis, 246 videos were included (N = 69 categorized as Personal Experience; N = 176 as Others, defined as videos from bloggers, piercers, or other persons; and N = 1 as Healthcare Professionals). The GQS rating in the category Personal Experience revealed that the quality of 50.7% of videos was very poor; 29.0% poor; 11.6% moderate, and 8.7% good. In the category Others, GQS rating showed that the quality of 60.8% of videos was very poor; 25.6% poor; 11.9% moderate, and 1.7% good. The one video in the category Healthcare Professionals was rated “poor quality”. Ratings applying the DISCERN tool were comparable. Overall, 111 (45.1%) videos recommended and 14 (5.7%) discouraged DP for migraine relief.

Conclusion

Based on the GQS and DISCERN scores, the information, usefulness, and accuracy of most YouTube content on DP for migraine treatment are generally of poor quality and reliability. The lack of high‐quality and reliable videos might expose users to potentially misleading information and dissemination of unproven medical interventions.

Keywords: acupuncture, complementary and alternative medicine, headache disorders, migraine piercing, pain, YouTube

Summary

The systematic search and the final analysis of 246 YouTube videos on Daith piercing as a migraine treatment revealed that most videos were anecdotal, lacked input from healthcare professionals, and demonstrated poor quality and reliability.

The findings highlight that YouTube is not a reliable source for medical information on Daith piercing for migraine treatment, underscoring the importance of consulting physicians and referencing peer‐reviewed research for well‐informed decision‐making.

1. Introduction

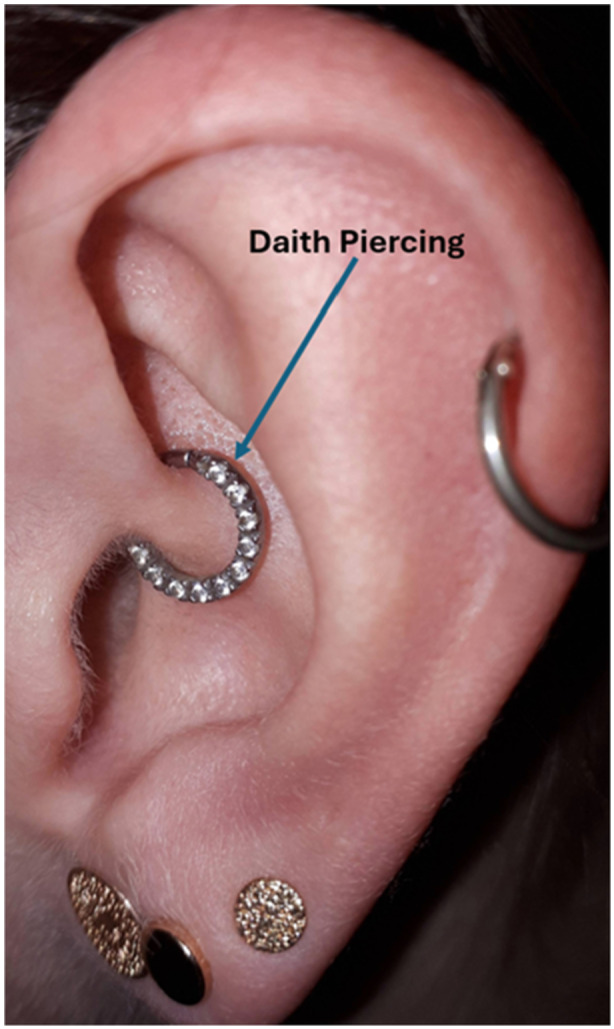

Migraine is a complex, recurring neurobiological disorder whose pathophysiology is still not fully understood [1]. Daith piercing (DP) also known as “migraine piercing”, consists in piercing the crus of the helix (Figure 1) and has gained popularity in recent years. Numerous video blogs on social media, such as YouTube, present DP as a potential alternative treatment for migraine. While anecdotal patient reports on the internet suggest an improvement in migraine symptoms, evidence to the extent to which YouTube influences patient decision‐making remains limited. In contrast, certain headache societies have released statements not supporting the use of DP as a treatment for migraine [2, 3]. A recent literature search about DP in migraine treatment discovered only one narrative review [4] and no clinical trials. The available literature, along with the documented recurrence of pain and the accompanying side effects attributed to DP, suggests that the current evidence does not substantiate the use of DP as an effective treatment for migraine [4]. Moreover, we found insufficient evidence for DP against migraine‐related pain relief [4]. As individuals with chronic or recurrent migraine progressively turn to the World Wide Web to obtain health‐related facts, the accessibility of a vast array of such information has become notably expedient. The use of YouTube for health‐related information has witnessed a major post content, facilitating easy communication and commentary among users [5]. Unlike TikTok and Instagram, YouTube allows unrestricted access to videos without requiring registration for passive viewing. It supports long‐form content, enabling in‐depth discussions and functioning as both a social media platform and search engine. While TikTok and Instagram prioritize short‐lived content that quickly becomes less visible in user feeds, YouTube videos remain accessible over time, potentially extending their influence. In contrast to Reddit, where discussions are often user‐driven and fragmented, YouTube enables creators to produce structured content with visual demonstrations, which may enhance perceived credibility. Additionally, monetization incentives can lead to more polished and persuasive content, influencing the dissemination of information. However, only consulting YouTube for health information presents various drawbacks, particularly the complexity of medical terminology for laypersons, potentially inaccurate content and presentation, and a possible lack of regulation to ensure evidence‐based accuracy. A recent comprehensive review by Raggi A. et al. examines multiple dimensions of migraine, including its genetic predispositions, diagnostic indicators, therapeutic options, and societal consequences [6]. Therefore, understanding the accuracy and reliability of disseminated information is crucial. Due to the absence of evidence but increasing popularity of applying health‐related measures promoted on YouTube, the primary aim of this systematic video analysis was to evaluate the current state of quality and reliability of published YouTube videos concerning the efficacy of DP in relieving migraine.

Figure 1.

Daith piercing on the crus of the helix.

2. Research Question

-

1.

What is the current state of quality and reliability of published YouTube videos concerning the efficacy of DP in relieving migraine?

-

2.

What are the reported characteristics of migraine and the efficacy of DP for migraine treatment? Do the analyzed videos recommend DP for migraine?

3. Methods

This systematic video review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses (PRISMA) [7] guidelines and was pre‐registered at PROSPERO (Nr: CRD42024510089). The PRISMA checklist can be found in the supplemental table S1.

3.1. Search Strategy

On January 17, 2024, a YouTube search was initiated on www.youtube.com using the keywords “Daith piercing” AND “migraine.” To streamline the search, the default sorting option was set to filter content by “number of views,” which is likely the most frequent choice in YouTube's sorting algorithm. Other criteria were also considered: relevance, upload date, view count, and rating. All identified YouTube videos from channel inception until the date of data extraction were screened for eligibility.

3.2. Study Eligibility Criteria

During the video screening, the following exclusion criteria were applied: (1) videos without comments or audio; (2) advertisements; (3) videos not related to migraine and/or DP; and (4) replicated videos, either in part or in whole. Furthermore, videos containing multiple sequences or segments were treated as a single entity, where each video, regardless of its internal divisions, was analyzed as a unified whole rather than as separate parts.

3.3. Data Extraction

The retrieval process was facilitated via the YouTube Data application programming interface version 3 (API v3) and programmed on Python, handling queries and storing the results into a pre‐defined data file. Two investigators (S.K.P. and G.T., trained in headache rehabilitation and fluent in Chinese, French, English, and German) independently evaluated each video by following a pre‐specified procedure and standardized form. Initially, the videos underwent full‐length screening and were selected based on whether they met the inclusion criteria. Before the video evaluation, and to minimize inter‐rater variability, both raters scored the first ten videos independently. Any discrepancies or issues that arose were discussed and solved to ensure alignment, thereby maintaining high standards of quality and consistency throughout the evaluation process. Thereafter, the two raters exchanged their ratings in regular meetings, ensuring stable coherence and agreement about video ratings. In case of disagreement, the video was discussed with the corresponding author.

3.4. Quality Assessment

Quality assessment was performed using the Global Quality Scale (GQS) [8]. The GQS involves a 5‐point Likert scale to evaluate each video blog's quality, flow, and user‐friendliness. A rating of 1 (very poor) stands for “poor quality, poor flow of the site, most information missing, not at all useful for patients”; while a rating of 2 (poor) means “generally poor quality and poor flow, some information listed but many important topics missing, of very limited use to patients”; 3 (moderate) stands for “moderate quality, suboptimal flow, some important information is adequately discussed but others poorly discussed, somewhat useful for patients”; 4 (good) means “good quality and generally good flow, most of the relevant information is listed”; and 5 (excellent) represents “excellent quality and excellent flow, very useful for patients” [8].

3.5. Reliability Assessment

Reliability assessment was applied by using the DISCERN tool [9]. DISCERN is structured into three sections consisting of 16 questions aimed at assessing the accuracy of health data for laypersons [10]. The first eight questions—section one—evaluate a publication's reliability regarding treatment information; questions 9–15—section two—focus on specific treatment details, and the final question—section three ‐ gives an overall quality rating based on the previous responses [9]. Each query is assessed on a 5‐point scale ranging from 1 (“criterion is not met at all”) to 5 (“criterion is fully met”). A maximum of 75 points could be achieved when, as suggested by Weil et al., omitting the final question and categorizing the DISCERN score as followed: 63–75 points for excellent, 51–62 for good, 39–50 for fair, 27–38 for poor, and 16–26 for very poor quality [11, 12].

3.6. Primary and Secondary Outcomes

The pertinent baseline details for each selected video were recorded, including URL, title, channel name, channel handle, channel ID, posted date and time, views, days on YouTube, likes, duration of the video in seconds, and the access date.

The primary outcome of this study was the overall quality and reliability of each selected video. This was performed by using two standardized tools. The GQS [8] was applied to rate the videos on a 5‐point scale, where 1 indicates poor quality and 5 reflects excellent quality. Additionally, the DISCERN [9] tool was used to assess the reliability of the health information provided in the videos, with 16 questions, each rated on a 5‐point scale, aimed at evaluating the quality of the content presented.

As secondary outcomes of interest, we defined the efficacy of DP in relieving migraine by using a 4‐point scale: 1 (very effective), 2 (effective), 3 (less effective), and 4 (not effective at all). Migraine relapse time was also recorded, documenting the time until migraine recurrence after receiving a DP. Healing time was assessed by noting the duration required for the pierced side to heal. Any comparisons made between DP and acupuncture in the videos were also documented. In addition, video updates were recorded, noting whether any updates or edits had been made to the video content after its initial posting.

The number of days the video had been available on YouTube was calculated. Information about which ear(s) were pierced was also recorded, specifying whether the piercing was performed uni‐ or bilaterally. The frequency of migraine before and after DP was documented, noting any changes in the number of migraine episodes reported by the video participants. Furthermore, the use of rescue medication before and after DP was tracked, as was the use of pharmaceutical pain relief, documenting whether a prescribed medication was utilized to manage migraine pain.

The quality of life (QoL) after DP was assessed on a scale from −2 (much worse) to 2 (much better), reflecting the participant's perceived improvement or decline in QoL postprocedure. The infection rate was captured, presenting the occurrence or percentage of infections associated with DP. We also noted whether medical consultation for infection was sought and whether the video provider recommended DP as a treatment for migraine. Additionally, any adverse or serious adverse events related to the DP procedure were documented.

Pain intensity measures were included in the analysis whenever possible. Migraine pain intensity was assessed using a Numeric Rating Scale (NRS) ranging from 0 to 10, where 0 represented no pain, and 10 the worst imaginable pain [13]. Comparisons of pain levels before and after DP were made utilizing this tool. Additionally, pre‐existing pain before receiving the procedure was measured on the same NRS scale from 0 to 10.

3.7. Assumptions for Missing or Unclear Data

In instances where specific data points or outcome measures were missing or unclear, several assumptions were made. If a critical piece of data, namely NRS migraine pain pre‐DP and post‐DP, was not specified in the video, it was marked as “not available.” Similarly, if the video did not provide detailed or full information, e.g., on the use of rescue medication or other relevant details, this was noted as missing but did not affect the overall analysis. Missing data was not replaced.

3.8. Inter‐Rater Reliability Between Raters, Based on Cohen's Kappa

Before the video evaluation, and to minimize inter‐rater variability, both raters scored the first ten videos independently. Based on this analysis, a detailed assessment guide was developed. Any discrepancies were thoroughly discussed to ensure alignment, thereby maintaining high standards of quality and consistency throughout the evaluation process. The inter‐rater reliability of GQS and the DISCERN was then calculated by means of Cohen's Kappa coefficient. Cohen's Kappa values smaller than 0.00 mean no agreement, between 0.01 to 0.20 poor, between 0.21 to 0.40 fair, between 0.41 and 0.60 moderate, and above 0.81 for near perfect agreement [14].

3.9. Statistical Analysis

To allow detailed insights into the quality and reliability of included videos, these were stratified by the sources: Health Professionals, Personal Experience, or Other. The category Other included videos from bloggers, piercers, and other non‐health professionals reporting about DP without personal experience. While further stratification could enhance precision, we opted to summarize these sources as “Other” to maintain focused and concise. Acknowledging these distinctions could be certainly essential for understanding the potential impact and credibility of the information shared across these platforms. Due to the non‐normal data distribution in the majority of outcomes, descriptive data used to describe the characteristics of the included videos about DP in treating migraine are presented with median (interquartile ranges [IQR]). For binominal outcomes, numbers and proportions were calculated and compared using Chi‐Square statistics or Fisher Exact Test. Continuous outcomes were compared between sources by using Mann‐Whitney two‐sample statistics. Statistical and graphical analyses were performed using RStudio (R version 2024.04.0), STATA version 15.1, and Sigmaplot version 15. A p‐value < 0.05 was considered to reflect statistical significance. To account for multiple testing in the co‐primary outcomes DISCERN and GQS, a Bonferroni correction of 0.05/2 = 0.025 was applied.

3.10. Ethical Considerations

Since all obtained videos were publicly available and the data were treated confidentially, no personal information was obtained. The Ethics Committee of Northwestern and Central Switzerland confirmed that the study does not fall within the scope of the Swiss Human Research Act. Therefore, no ethical approval was required. Written informed consent to publish photo‐documentation was obtained from the patient (Figure 1).

4. Results

A total of 496 video recordings were initially identified on YouTube. After removing 20/496 (4%) duplicate videos, 476/496 (96%) records were screened, resulting in the exclusion of 230/476 (48%) videos. Reasons for the exclusion were: the lack of comments and audio (102/476, 21%); videos unrelated to migraine (98/476, 21%); language restrictions (17/476, 4%); or videos that did not pertain to DP (13/476, 3%) (Figure 2). Therefore, a total of 246 videos were included in the final analysis (Supplement, S2). 69/246 (39.8%) of these were categorized as Personal Experience, 1/246 (0.5%) as Healthcare Professionals, and the remaining 176/246 (71.5%) as Other: The Other category contained 63/246 (25.6%) videos from bloggers, 69/246 (28.0%) from piercers, and 15/246 (6.1%) from news channels. The median number (IQR) of days the videos were available on YouTube was 63 (43; 78) days, with a median video duration of 3:59 (2:32; 8:04) min. Table 1 provides an overview of the included video characteristics related to DP for migraine treatment. The inter‐rater variability for rating the primary outcomes yielded a Cohen's Kappa value of 0.50 for GQS and 0.47 for DISCERN, indicating moderate agreement between raters.

Figure 2.

Video selection flowchart.

Table 1.

YouTube video characteristics about Daith piercing in treating migraine.

| n | Total | Personal experience | Other | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of videos, n | 2461 | 69 | 176 | |

| Days on YT | 246 | 63 (43; 78) | 58 (38; 78 | 64 (44; 78) |

| Views, n | 246 | 600 (206; 5738) | 561 (185; 5934) | 643 (213; 5717) |

| Likes, n | 235 | 8 (2; 56) | 5 (1; 55) | 10 (2; 56) |

| Duration, min: sec | 246 | 3:59 (2:32; 8:04) | 3:04 (1:51; 4:18) | 4:53 (3:00; 8:57)* |

| Quality and reliability assessment | ||||

| DISCERN publication reliability2 | 246 | 10 (8; 15) | 10 (8; 21) | 10 (8; 14) |

| DISCERN treatment details2 | 246 | 9 (7; 13) | 8 (7; 12) | 10 (7; 14)* |

| DISCERN total score2 | 246 | 20 (15; 28) | 19 (15; 35) | 21 (16; 27) |

| DISCERN categorization | 246 | |||

| Excellent, n (%) | 5 (2.0%) | 5 (7.2%) | 0 (0.0%)* | |

| Good, n (%) | 22 (8.9%) | 7 (10.1%) | 15 (8.5%) | |

| Moderate, n (%) | 35 (14.2%) | 9 (13.0%) | 26 (14.8%) | |

| Poor, n (%) | 105 (42.7%) | 18 (26.1%) | 87 (49.4%)* | |

| Very poor, n (%) | 79 (32.1%) | 30 (43.5%) | 48 (27.3%)* | |

| GQS total score3 | 246 | 1 (1; 2) | 1 (1; 2) | 1 (1; 2) |

| GQS categorization | 246 | |||

| Excellent, n (%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Good, n (%) | 9 (3.7%) | 6 (8.7%) | 3 (1.7%)* | |

| Moderate, n (%) | 29 (11.8%) | 8 (11.6%) | 21 (11.9%) | |

| Poor, n (%) | 66 (26.8%) | 20 (29.0%) | 45 (25.6%) | |

| Very poor, n (%) | 142 (57.7%) | 35 (50.7%) | 107 (60.8%) | |

| Secondary outcomes (if reported in the video) | ||||

| Related to acupuncture, yes/no (%) | 246 | 16/230 (6.5%) | 9/60 (13.0%) | 7/169 (4.0%)* |

| DP recommendation, yes/no (%) | 125 | 111/14 (88.8%) | 12/6 (66.7%) | 99/8 (92.5%)* |

| Efficacy of DP in relieving migraine, %4 | 149 | 2 (1; 2) | 2 (1; 2) | 2 (1; 2) |

| Frequency of migraine before DP, days per month | 51 | 16 (4; 29) | 25 (12; 30) | 12 (4; 20) |

| Frequency of migraine after DP, days per month, % | 32 | 0 (0; 2) | 0 (0; 0) | 0 (0; 2) |

| Infection rate after DP, yes/no (%) | 36 | 21/15 (58%) | Not reported | 21/15 (58.3%) |

| Medical consultation due to infection, yes/no (%) | 13 | 1/12 (7.7%) | Not reported | 1/12 (7.7%) |

| NRS migraine pain before DP | 0 | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| NRS migraine pain after DP | 0 | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Pharmacological pain relief, yes/no (%) | 52 | 45/7 (86.5%) | 7/0 (100%) | 38/7 (84.4%) |

| Piercing healing time, weeks | 35 | 20 (5; 43) | 36 (12; 36) | 18 (4; 43) |

| QoL after DP score5 | 133 | 1 (1; 2) | 1 (1; 2) | 1 (1; 2) |

| Rescue medication before DP, yes/no (%) | 56 | 54/2 (96.4%) | 8/0 (100%) | 46/2 (95.8%) |

| Rescue medication after DP, yes/no (%) | 28 | 20/8 (71.4%) | 1/1 (50.0%) | 19/7 (73.1%) |

Values are presented in median (IQR).

p < 0.05 between Personal Experience and Other group.

One video originating from Health Professionals is not separately listed in this table, however, it is incorporated in the Total section.

The DISCERN tool consists of 16 questions divided into three sections to assess health information accuracy for laypersons. Questions 1–8 evaluate the publication reliability; questions 9–15 examine the treatment details [9, 10]. Each question is rated on a 5‐point scale from 1 (“not met”) to 5 (“fully met”), with a maximum score of 75. Videos are categorized by DISCERN scores: excellent (63‐75), good (51‐62), fair (39‐50), poor (27‐38), and very poor (16‐26) [11].

The GQS involves a 5‐point Likert scale denoting 1 (very poor) “Poor quality, poor flow of the site, most information missing, not at all useful for patients”; 2 (poor) “Generally poor quality and poor flow, some information listed but many important topics missing, of very limited use to patients”; 3 (moderate) “Moderate quality, suboptimal flow, some important information is adequately discussed but others poorly discussed, somewhat useful for patients”; 4 (good) “Good quality and generally good flow, most of the relevant information is listed; and 5 (excellent) “Excellent quality and excellent flow, very useful for patients [8].

DP for relieving migraine was rated using a 4‐point scale: 1 (very effective), 2 (effective), 3 (less effective), and 4 (not effective at all).

Quality of life after DP was assessed on a scale from −2 (much worse) to 2 (much better), reflecting the participant's perceived improvement or decline in QoL postprocedure.

DP, Daith piercing; GQS, Global Quality Score; NA, Not available. NRS, Numerical rating scale; QoL, Quality of Life; YT, YouTube.

4.1. Primary Outcome

4.1.1. Quality Assessment By GQS

Overall, videos categorized as “very poor” accounted for 142/246 (57.7%) of the total, including 35/69 (50.7%) in the Personal Experience group and 107/176 (60.8%) in the Other group. “Poor quality” videos made up for 26.8% (66/245) of all videos, with 20/69 (29.0%) from Personal Experience and 45/176 (25.6%) from Other as well as the one Healthcare Professionals video. No videos were rated as “excellent quality”, and a small proportion of videos were “good quality”, specifically 9/246 (3.7%) overall, 6/69 (8.7%) in Personal Experience, and 3/176 (1.7%) in Other.

4.1.2. Reliability Assessment By DISCERN

The analysis of video reliability based on the DISCERN score categorized 105/246 (42.7%) of all videos as having “poor” and 79/246 (32.1%) as “very poor” reliability. In Personal Experience, 30/69 (43.5%) were rated “very poor”, while 18/69 (26.1%) scored poor reliability. In Other, 48/176 (27.3%) were “very poor”, and 87/176 (49.4%) were “poor quality”. Only 5/69 (7.2%) of Personal Experience videos and 15/176 (8.5%) in the Other group scored “excellent” reliability (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Quality and reliability assessments by the Global Quality Scale (GQS) and DISCERN categorization across the three video categories: Personal experience, Other, and Health professionals. The category Other contains videos published from bloggers, piercers and news channels. *p < 0.05 versus Personal Experience in the same quality category of the GQS or DISCERN score.

4.1.3. Secondary Outcome

The association between DP and acupuncture, rooted in the theoretical framework of traditional acupuncture, was mentioned in 16/246 (6.5%) videos. The left ear was pierced in 66/246 (26.8%) of videos, the right ear in 57/246 (23.2%), and both ears in 61/246 (24.8%), while 62/246 (25.2%) of videos provided no information as for the pierced side(s) (Table 1). The median (IQR) efficacy score in relieving migraine was 2 (1; 2) points on a 4‐point Likert scale, derived from 149/246 (60.6%) of videos. The median migraine frequency per day/month before DP was 16 (4; 29) and decreased to 0 (0; 2) after DP. Rescue medication use before DP was described in 54/246 (21.9%) of videos and decreased to 20/246 (8.1%) after DP. The median duration for piercing healing was 20 (5: 43) weeks. The incidence of infection following DP was reported in 21/246 (8.5%) of videos. Only 1/246 (0.4%) of videos described a patient seeking medical consultation for infection, which can be regarded as an adverse event. From all videos providing a recommendation statement 111/125 (88.8%) recommended and 14/125 (11.2%) discouraged DP for migraine relief. According to our statistics, significantly fewer videos in the Personal Experience recommend DP for migraine compared to those in the Other category.

5. Discussion

An increasing number of migraine patients are turning to social media, such as YouTube, as a source of information regarding DP in migraine treatment, which is largely attributable to the platform's ease of access. The 246 videos analyzed in this systematic video review collectively received a total of approximately 4.7 million views, indicating a substantial interest in DP as a possible therapeutic intervention for migraine. Overall, 111/125 (88.8%) of videos recommended DP to relieve migraine. In contrast and based on our systematic video review, YouTube cannot be recommended from a medical point of view for patients seeking information on DP as a treatment for migraine. The poor quality and reliability of the video content, high rates of missing data, and limited involvement of healthcare professionals raise concerns about the information quality, the accuracy of the content, and reliability of the information available on YouTube regarding DP for migraine treatment.

In the study by Karacan et al. on Botox treatment, crucial correlations were observed between GQS and DISCERN (R = 0.757; p < 0.001), with an average DISCERN score of 3.09 out of 5 [15]. The present DP study showcased “poor” and “very poor” quality DISCERN scores across most video categories, with 105/246 (42.7%) of total videos rated as “poor” and 79/246 (32.1%) as “very poor”. Specifically, 48/176 (27.3%) of videos from Other and 48/176 (43.5%) from Personal Experience were ranked as “very poor” quality, with only 5/69 (7.2%) from Personal Experience being evaluated as “excellent”. The sole video from a Healthcare Professionals in the DP analysis was also graded as “very poor”. As for reliability, the videos from Karacan et al., showed moderate DISCERN scores, with substantial differences observed based on the narrator's qualifications (p = 0.002), whereas videos produced by university/nonprofit physicians or professional organizations pointed out greater reliability [15]. While videos on Botox for migraine displayed higher quality and reliability [15], DP videos largely lacked reliable content.

In another study, Hakyemez et al. demonstrated that videos uploaded by physicians had a notable higher GQS (4.66 ± 0.47) compared to those uploaded by non‐physicians (3.30 ± 0.91, p < 0.01). Similarly, DISCERN scores were higher for physician‐uploaded videos (4.56 ± 0.50) compared to non‐physician videos (3.32 ± 0.85, p < 0.01) In comparison, this DP study discovered a high prevalence of poor quality videos and an overall mean GQS score of 1.61 ± 0.83 and DISCERN score of 24 ± 10 in the 246 included videos. While both studies evaluated the quality and reliability of YouTube videos, substantial differences were observed. Neonatal sepsis videos, particularly those submitted by healthcare professionals, confirmed notably higher GQS and DISCERN scores [16]. Again, DP videos exhibited much lower scores in GQS and DISCERN scores.

The majority of the videos analyzed by Erten et al. on glycated hemoglobin levels (HbA1c) involved professionals, with 19/56 (34%) originating from medical educational channels, 14/56 (25%) from medical doctors, and 14/56 (25%) from other healthcare providers [17]. The GQS for all videos was 3.7 ± 1.0 (median: 4), with medical doctor‐uploaded videos achieving the highest GQS scores (4.6 ± 0.4, median: 5) [17]. The mean DISCERN score across all videos was 59.0 ± 10.5 (median: 60.5), with videos produced by medical doctors again reaching the highest scores (66 ± 8, median: 68). A considerable correlation was observed between GQS and DISCERN scores (R = 0.874; p < 0.05) [17]. Furthermore, regression analysis revealed that the video duration was profoundly associated with GQS and DISCERN scores (p < 0.05) [17]. In contrast, the current DP study predominantly included videos from non‐professional sources, highlighting the potential for improvement.

The findings of this study suggest that YouTube does not provide high‐quality and reliable information regarding DP as a treatment for migraine. The qualitative content and the reliability of information on YouTube regarding DP for migraine are poor across all video categories, as displayed by both GQS and DISCERN scores (Figure 3). Considering the 246 videos analyzed, the vast majority (n = 245) were created based on personal experience or by bloggers, piercers or news channels without providing sufficient medical information. This high prevalence of non‐medical content may be explained by the subjective nature of migraine pain, which patients primarily experience themselves. Consequently, videos are more likely produced by individuals sharing personal narratives and experiences rather than by medical professionals. Although higher quality ratings of videos originating from Personal Experience were observed, the overall poor quality and trend raises concerns about the potential for misinformation related to DP for migraine treatment on YouTube. Healthcare professionals may hesitate to engage with YouTube content on DP due to the lack of scientific evidence supporting its efficacy, professional caution given its unproven status, the procedure being performed by non‐clinical practitioners, ethical and legal concerns about spreading unverified information, and the risk of contributing to misinformation in a public domain.

Despite some videos reporting migraine relief from DP, the majority of these miss out on reliable information, suggesting a publication bias. The reported reduction in migraine frequency after DP ‐ from an average of 20.7 days per month to 13.0 attacks/month, might underscore the potential of DP as an alternative treatment option in migraine management. The reported effects on migraine frequency are described without a control‐group and therefore may be affected by effects like placebo, selection bias, or regression to the mean. However, the high rates of missing data and the lack of prospective clinical trials do not allow to recommend DP for migraine. Furthermore, Pradhan et al. have demonstrated in their literature review that no link between auricular acupuncture and DP exists in the context of migraine relief [4], raising further concerns about the its efficacy and mechanism of action for migraine treatment.

5.1. Limitation

The current study has some limitations. First, numerous other social media platforms such as Facebook, TikTok, Instagram, LinkedIn, Twitter, Vimeo, and other video platforms provide similar content. Therefore, the inclusion of additional platforms might have provided different results. Nevertheless, the scope of this study focused on YouTube, since YouTube supports videos with a longer duration, potentially allowing the creators to discuss the topic in full. Nonetheless, future research could consider examining other social media platforms, or include videos in other languages than English, Chinese, French, and German to better understand how social media serves as a source of information about DP in the context of migraine management [18]. Furthermore, the outcome of this study may be influenced by the search terms selected. Our systematic video analysis focused on the keywords “Daith piercing” AND “Migraine.” However, these may not necessarily reflect the keywords that an average user might enter while exploring content on YouTube on this relevant subject. It is possible that patients could utilize different terms, leading to different video results and findings. Lastly, analyzing video content is a subjective interpretation, which might result in varying quality assessments.

6. Conclusion

Based on our systematic video review, YouTube cannot be recommended as a reliable source from a medical point of view for patients seeking information on DP as a treatment for migraine. The poor quality and reliability of the video content, high rates of missing data, high‐risk for placebo effects, insufficient updates, and limited involvement of healthcare professionals raise concerns about the information quality, the accuracy of the content, and reliability of the information available on YouTube regarding DP for migraine treatment. Furthermore, most videos reflect anecdotal experiences rather than scientifically validated data, which might lead to a positive reporting bias. A large number of videos focus on immediate headache relief experience, often neglecting the long‐term consequences of DP healing time, infections and potential side effects. Nevertheless, while many videos are of low quality, some could still contain valuable patient experiences that warrant consideration.

Author Contributions

Saroj K. Pradhan: conceptualization, data curation, methodology, investigation, validation, formal analysis, project administration, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing. Michael Furian: conceptualization, methodology, supervision, data curation, investigation, validation, formal analysis, writing – review and editing. Giada Todeschini: data curation, formal analysis, investigation, writing – review and editing. Qiong Schürer: data curation, formal analysis, writing – review and editing, investigation. Xiaying Wang: formal analysis, investigation, writing – review and editing. Bingjun Chen: formal analysis, investigation, writing – review and editing. Yiming Li: validation, formal analysis, investigation, writing – review and editing. Andreas R. Gantenbein: conceptualization, formal analysis, investigation, validation, methodology, supervision, writing – review and editing.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript. Saroj K. Pradhan had full access to all of the data in this study and takes complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

1. Transparency Statement

The lead author Saroj K. Pradhan affirms that this manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

Supporting information

Supplement S1 PRISMA 2020 checklist.

Supplement S2 YT DP final.

Acknowledgments

This review was supported by SWISS TCM UNI, the China‐Swiss TCM Centre and TCM Ming Dao AG. The supporting sources had no role in designing this study, in writing the manuscript, or in deciding to submit this manuscript.

Saroj K. Pradhan and Michael Furian contributed equally

Data Availability Statement

The data that supports the findings of this study are available in the Supporting material of this article.

References

- 1. Goadsby P. J. and Holland P. R., “Pathophysiology of Migraine,” Neurologic Clinics 37, no. 4 (2019): 651–671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. DMKG . Die DMKG warnt: Piercing ist nicht zur Therapie der Migräne geeignet! 2022,https://www.dmkg.de/therapie-empfehlungen/migraene/die-dmkg-warnt-piercing-ist-nicht-zur-therapie-der-migraene-geeignet.

- 3.American‐Migraine‐Foundation. Daith Piercings & Migraine. 2017, https://americanmigrainefoundation.org/resource-library/daith-piercings-101/.

- 4. Pradhan S. K., Gantenbein A. R., Li Y., et al., “Daith Piercing: Revisited From the Perspective of Auricular Acupuncture Systems. A Narrative Review,” Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain 64, no. 2 (2024): 131–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Osman W., Mohamed F., Elhassan M., and Shoufan A., “Is Youtube a Reliable Source of Health‐Related Information? A Systematic Review,” BMC Medical Education 22, no. 1 (2022): 382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Raggi A., Leonardi M., Arruda M., et al., “Hallmarks of Primary Headache: Part 1—Migraine,” Journal of Headache and Pain 25, no. 1 (2024): 189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Page M. J., McKenzie J. E., Bossuyt P. M., et al., “The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews,” BMJ 372 (2021): n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bernard A., Langille M., Hughes S., Rose C., Leddin D., and Veldhuyzen van Zanten S., “A Systematic Review of Patient Inflammatory Bowel Disease Information Resources on the World Wide Web,” American Journal of Gastroenterology 102, no. 9 (2007): 2070–2077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Charnock D. and Shepperd S. Welcome to Discern: Radcliffe Online; 2004, http://www.discern.org.uk/index.php.

- 10. Charnock D., Shepperd S., Needham G., and Gann R., “DISCERN: An Instrument for Judging the Quality of Written Consumer Health Information on Treatment Choices,” Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health 53, no. 2 (1999): 105–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cassidy J. T. and Baker J. F., “Orthopaedic Patient Information on the World Wide Web: An Essential Review,” Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery 98, no. 4 (2016): 325–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Weil A. G., Bojanowski M. W., Jamart J., Gustin T., and Lévêque M., “Evaluation of the Quality of Information on the Internet Available to Patients Undergoing Cervical Spine Surgery,” World Neurosurgery 82, no. 1–2 (2014): e31–e39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Breivik H., Borchgrevink P. C., Allen S. M., et al., “Assessment of Pain,” British Journal of Anaesthesia 101, no. 1 (2008): 17–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. McHugh M. L., “Interrater Reliability: The Kappa Statistic,” Biochemia Medica 22, no. 3 (2012): 276–282. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Karacan Gölen M. and Işik Ş. M., “Quality and Reliability Analysis of Migraine Botox Treatment Information on Youtube,” Medicine 103, no. 38 (2024): e39824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hakyemez Toptan H. and Kizildemir A., “Quality and Reliability Analysis of Youtube Videos Related to Neonatal Sepsis,” Cureus 15, no. 5 (2023): e38422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Erten M., “HbA1c AND E‐Health: Youtube Might be Good for You, If You Use It Wisely,” Acta Endocrinologica (Bucharest) 18, no. 4 (2022): 531–535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chen J. and Wang Y., “Social Media Use for Health Purposes: Systematic Review,” Journal of Medical Internet Research 23, no. 5 (2021): e17917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplement S1 PRISMA 2020 checklist.

Supplement S2 YT DP final.

Data Availability Statement

The data that supports the findings of this study are available in the Supporting material of this article.