Abstract

Objectives

This study seeks to examine the impact of hospital organizational behavior on Physicians' Patient-centered care and aims to offer innovative insights and strategies for enhancing the quality of healthcare services.

Methods

A conceptual model was developed based on organizational behavior theory. Data were collected via questionnaires from 10 large public hospitals in China, encompassing eight independent variables, including hospital organizational culture, change behavior, and motivational behavior, as well as moderating variables like physician title and control variables such as personality traits. SPSS software was used for descriptive statistics, correlation analysis, covariance testing, and multiple linear regression analysis.

Results

(1) The study of the 10 large public hospitals revealed a coexistence of four types of organizational cultures. Support-oriented and innovation-oriented cultures were dominant, followed by rule-oriented cultures, while goal-oriented cultures scored relatively low. Additionally, these hospitals showed effective organizational change behaviors in technology and resource optimization, as well as inter-professional teamwork. Incentives related to employee welfare systems and development programs also demonstrated high implementation effectiveness.

(2) Supportive and innovation-oriented hospital cultures positively influence Physicians' Patient-centered care, while goal-oriented cultures negatively impact Physicians' Patient-centered care.

(3) In public hospitals, organizational change behaviors such as technology and resource optimization, along with inter-professional teamwork, positively influence Physicians' Patient-centered care. Additionally, organizational incentives like employee welfare systems and training programs enhance Physicians' Patient-centered care.

(4) The moderating variable of physician title negatively affects the relationship between the employee welfare system and Physicians' Patient-centered care, as well as the relationship between the staff development program and Physicians' Patient-centered care.

Conclusions

Hospital organizational behavior significantly impacts Physicians’ Patient-centered care. Supportive and innovative cultures, effective change behaviors, and incentives enhance Physicians’ Patient-centered care. Addressing limited resources and high demand is essential for optimizing healthcare service quality.

| Text box 1. Contributions to the literature |

|---|

| 1. The study reveals that the organizational culture of large public hospitals in China exhibits a coexistence of four orientations, with supportive and innovative cultures being predominant. |

| 2. The organizational change behaviors and motivational behaviors of public hospitals positively influence Physicians'Patient-centered care, indicating that effective organizational change and motivation are crucial for healthcare quality. |

| 3. Supportive and innovative organizational cultures, along with effective change behaviors and motivational measures, can enhance Patient-centered care and address issues of limited resources and high demand, which are essential for optimizing healthcare quality. |

Introduction

With economic development and population growth, the number of patients with chronic diseases has continued to rise, and the public's demand for high-quality medical services has increased significantly. The rapid development of information technology has not only enhanced the public's health awareness, but also raised patients'expectations for medical quality. In this situation, modern patients not only seek effective treatment methods but also attach greater importance to their experiences during the medical process.

Existing studies have shown that modern medical services emphasize patient-centered care. This model not only focuses on the quality and efficiency of healthcare services but also on the experience and satisfaction of individual patients [1]. In the process of doctor-patient communication, doctors play a crucial role in providing medical information and treatment plans, and their behaviors directly affect the quality of hospital services and the patient experience [2]. With the rise of online healthcare options such as telemedicine, it has become more convenient for the public to access medical information. At the same time, the improvement of healthcare awareness and the right to self-treatment has prompted the public to have more communication with doctors during the healthcare process [3–5]. Many scholars have pointed out that the patient-centered care model requires healthcare providers to place patients'needs, preferences and values at the core of medical decisions and services [6–12]. Under this model, doctors and patients collaborate closely, which can provide more personalized, comprehensive and coordinated healthcare services, thereby enhancing patient satisfaction and the overall quality of care [13–17].

However, although patient-centered care has significant advantages in improving patient satisfaction and the quality of healthcare, the conflict between limited medical resources and the growing public demand has led to prolonged waiting times for patients and reduced communication time with doctors [18]. The research by Liu and Wang shows that from January 2018 to December 2020, approximately 86.1% of the disputes in eight hospitals in Shanghai were related to doctors, mainly attributed to insufficient communication [19]. Meanwhile, doctors are confronted with challenges such as high work pressure, low income satisfaction, long working hours and negative media coverage [20]. Importantly, while existing research on physician behavior has primarily focused on internal factors (e.g., self-efficacy, achievement motivation) [21–23] and organizational influences on job satisfaction or loyalty, it has overlooked the specific impacts of macro-level organizational behaviors (e.g., culture, change initiatives) and micro-level mechanisms (e.g., incentive systems) on physicians’ patient-centered care (PCC) practices [22, 24–26]. Most studies to date have also neglected how external organizational contexts shape PCC behaviors, despite growing recognition of their role in clinical decision-making [27–30]. These gaps highlight an urgent need to understand how hospitals can effectively promote PCC amid resource constraints, particularly by addressing organizational determinants of physician behavior.

Drawing on organizational behavior theory, which emphasizes how leadership styles and group dynamics influence individual actions, this study aims to fill these gaps by examining the effects of hospital organizational behaviors—conceptualized at both macro (organizational culture, change initiatives) and micro (incentive systems) levels—on physicians’ PCC practices. The study constructs a conceptual model to explore this relationship, incorporating physician professional title as a moderating variable and physician personality traits as a control variable to account for individual differences in behavior.

To achieve this, we adopted an online anonymous questionnaire (6 sections, 5-point Likert scale) and collected data from 10 large hospitals in China, yielding 324 valid responses from 350 questionnaires. Data were analyzed using SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences 27.0.1), with three-level regression models used to test the hypothesized relationships among variables.

The structure of this article is arranged as follows: Chapter Two elaborates on the research methodology, including survey design, sample characteristics, and analytical methods (detailing variable definitions for moderators and control variables); Chapter Three presents descriptive statistics, correlation analyses, and regression results; Chapter Four discusses theoretical contributions (e.g., distinguishing macro–micro organizational influences on PCC) and practical implications for healthcare management; Chapter Five summarizes key findings and outlines directions for future research and policy. By bridging organizational behavior theory with empirical evidence of physician behavior, this study seeks to offer new insights into fostering patient-centered care within resource-constrained healthcare systems.

Methods

Questionnaire design

The questionnaire design of this study focuses on the influence mechanism of hospital organizational culture (rules, goals, support, and innovation based on Quin-based model), change behavior (technical resource optimization and cross-team collaboration), and incentive behavior (welfare system and training plan) on doctors'PC diagnosis and treatment behavior, and introduces doctors'titles as moderating variables and Big five personality traits as controlling variables. The questionnaire was anonymized online, covering doctors with different titles, departments and seniority in 10 public hospitals in China to ensure the diversity of samples and the universality of conclusions. The structure includes six parts: (1) the information of doctor's title; (2) Big five personality traits assessment; (3) Four dimensions of organizational culture; (4) Technical resources and cooperation indicators of change behavior; (5) Welfare coverage and training effectiveness of incentive behavior; (6) Core characteristics of PC diagnostic behavior (attitudinal care, information sharing, and patient engagement). The 5-point Likert scale was used to quantify scores for each module, and the reliability and validity of item were optimized by pretest (such as adjusting the form of organizational culture scale), and the mean value was calculated to achieve variable standardization.

The quantitative data generated from the survey provides a foundation for subsequent statistical analyses, enabling this study to explore the relationship between organizational behavior characteristics and Physicians’ Patient-centered care through correlation and regression analyses, as well as the potential moderating effect of physician titles.

Data sources

This study utilizes offline data from large public hospitals to capture the authentic organizational behaviors of these institutions and the genuine Physicians’ Patient-centered care.

Based on the number of items in the questionnaire, this study selected 10 representative large tertiary hospitals in China. The questionnaires were distributed online, targeting Physicians from various departments within each hospital, with a minimum of 26 and a maximum of 35 responses per hospital. The selected hospitals represent a diverse range of scales and services, including large general hospitals and specialty hospitals that provide comprehensive healthcare as well as those focused on specific areas (such as pediatrics and oncology). This diversity in resource allocation, management models, and service priorities offers a multi-dimensional perspective on the impact of hospital organizational behavior on Physicians'practices.

Data collection

In this study, a pilot distribution of the questionnaire was conducted, resulting in 95 responses from Physicians in public hospitals. The reliability and validity of the scale items were found to be good, indicating that the questionnaire effectively reflects the constructs intended for exploration in this research.

Data analysis

This study utilized SPSS as the data analysis software. After distributing the questionnaire, invalid responses were excluded, resulting in 324 valid entries imported into SPSS. Descriptive statistics were generated for each variable, with significance determined at .

This study employed hierarchical regression analysis to explore the relationships between various variables and Physicians’ Patient-centered care, dividing the analysis into three models to assess the changes in as each variable is added. The hierarchical regression analysis consists of three models, outlined as follows:

(1) Model 1 examines the impact of control variables, specifically Physicians'personality traits, on their Patient-centered, as described by the following equation:

(2) Model 2 explores the effects of independent variables—hospital organizational culture, technology and resource optimization, inter-professional teamwork, employee welfare systems, training programs—and the moderating variable of physician title on Physicians’ Patient-centered care, as described by the following equation:

(3) Model 3 builds on Model 2 by including interaction terms between physician title, hospital organizational culture, change behaviors, incentive behaviors, and Physicians’ Patient-centered care, as described by the following equation (Table 1):

Table 1.

Parameter definition table

| Parameter | Definition |

|---|---|

| DPC | Physicians’Patient-centered care |

| i | i = 1,……N, Physician |

| βi | i = 0,1,2…, Estimated Parameter |

| Title | Physician Title |

| DPT | Physician’s personality traits, |

|

ROC GOC SOC IOC TRO DTC EWS EDP ε |

Rule oriented hospital organizational Goal oriented hospital organizational Support oriented hospital organizational Innovation oriented hospital organizational Technology and resource optimization Disciplinary team collaboration Employee welfare system Employee development plan Error Term |

Results

Based on the results from the pilot survey, adjustments were made to the questionnaire before distributing it to Physicians at the 10 selected public hospitals in the city to gather data on hospital organizational behavior and Physicians’ Patient-centered care. After the official distribution, a total of 350 questionnaires were collected, indicating that the number of responses from each hospital was within the expected range without any extreme cases. Following this, 26 invalid questionnaires were removed due to unusually fast completion times or extreme scores, resulting in 324 valid responses.

Descriptive statistics

Overall, the current data distribution is nearly flat and approximates a normal distribution, with the skewness also approaching normality. For the control variables, the mean scores of the Physicians'personality traits are close (), indicating a generally positive self-assessment, with most Physicians showing balanced traits across the Big Five personality factors. The standard deviations range from 1.183 to 1.246, suggesting that while many Physicians share similar evaluations of their personality traits, there are still some differences. Notably, neuroticism has the lowest average score and the highest standard deviation ( 3.75, 1.25), indicating the greatest variation in self-assessment among Physicians.

For the independent variable of hospital organizational culture, goal-oriented culture has the lowest average score among the four types (, ), indicating a relatively weak goal-oriented culture in public hospitals in the city. Conversely, supportive organizational culture has the highest average score (, ), suggesting it is the most prominent type in these hospitals. The relatively low standard deviation indicates that most employees share a consistent positive evaluation of the supportive culture.

For the independent variable of hospital change behaviors, it is evident that public hospitals in the city have a high level of technology and resource optimization (, ), indicating significant achievements, though internal evaluation differences are considerable. Additionally, these hospitals excel in inter-professional teamwork (, ), demonstrating effective collaboration and communication across different specialties.

For the independent variable of hospital incentive behaviors, public hospitals in the city perform well in employee welfare systems (, ), indicating a strong focus on employee benefits. Additionally, the implementation of employee training programs is high (, ), with employees generally believing that the training and development opportunities provided by the hospitals meet their career advancement needs.

For the dependent variable of Physicians’ Patient-centered care, public hospitals show a high level of Patient-centered care (, ), indicating that physicians perform well in providing patient-centered care.

Regression bode (Table 2)

Table 2.

Regression model results

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 4.043** | 0.970* | 0.816* |

| DPT | −0.087 | −0.032 | −0.021 |

| Title | 0.057 | 0.088 | |

| ROC | −0.006 | −0.007 | |

| GOC | −0.100* | −0.083* | |

| SOC | 0.182** | 0.205** | |

| IOC | 0.157** | 0.168** | |

| TRO | 0.140** | 0.179** | |

| DTC | 0.104* | 0.088 | |

| EWS | 0.134** | 0.142** | |

| EDP | 0.111* | 0.064 | |

| ROC*Title | 0.035 | ||

| GOC*Title | 0.135 | ||

| SOC*Title | 0.205 | ||

| IOC*Title | 0.085 | ||

| TRO*Title | 0.232 | ||

| DTC*Title | −0.076 | ||

| EWS*Title | −0.211* | ||

| EDP*Title | −0.384** | ||

| 0.008 | 0.478 | 0.519 | |

| 0.005 | 0.461 | 0.491 | |

| F□ | F (1,323) = 2.578,p = 0.109 | F (10,314) = 28.698,p = 0.000 | F (18,306) = 18.329,p = 0.000 |

| △ | 0.008 | 0.47 | 0.041 |

| △F□ | F (1,323) = 2.578,p = 0.109 | F (9,314) = 31.358,p = 0.000 | F (8,306) = 3.282,p = 0.001 |

Dependent Variable: Physicians’ Patient-centered care

*p < 0.05 **p < 0.01 (t values in parenthesis)

Using Pxe (Model 1) and their implementation of Physicians’ Patient-centered care as the dependent variable, a linear regression analysis was conducted. The results indicate that personality traits do not significantly affect Physicians’ Patient-centered care , not significant by F-test). Therefore, it is not possible to analyze the impact of the independent variable on the dependent variable. We believe that healthcare institutions typically have strict policies and regulatory mechanisms to ensure that Physicians'practices comply with standards and legal requirements. These policies aim to safeguard patient safety and treatment outcomes, reducing the arbitrary influence of personal factors (such as personality traits) on medical behaviors. Additionally, Physicians undergo rigorous professional training and education that emphasize adherence to standardized medical procedures and clinical guidelines. Consequently, Physicians'personality traits have only a minimal explanatory significance and do not influence their implementation of Physicians’ Patient-centered care.

In Model 2, after adding the independent variables of physician title and hospital organizational culture, as well as technology and resource optimization, the F-value shows significance (p < 0.05), indicating that these moderating variables provide explanatory power for the model. Physician title does not directly affect Physicians’ Patient-centered care (p > 0.05), and further observation of the interaction terms is necessary.

Additionally, rule-oriented hospital organizational culture does not influence Physicians’ Patient-centered care (). Goal-oriented culture has a significant negative impact on Physicians’ Patient-centered care (=−1.000, p < 0.05), while supportive culture positively influences Physicians’ Patient-centered care (=0.182, p < 0.01). Innovative culture also has a significant positive effect on Physicians’ Patient-centered care (=0.157, p = 0.000 < 0.01).

Technology and resource optimization have a significant positive impact on Physicians’ Patient-centered care (). Inter-professional teamwork also positively influences Physicians’ Patient-centered care ). The employee welfare system significantly enhances Physicians’ Patient-centered care (), and employee training programs positively affect Physicians’ Patient-centered care as well ().

In Model 3, after adding interaction terms (ROC*Title, GOC*Title, SOC*Title, IOC*Title, TRO*Title, DTC*Title, EWS*Title, EDP*Title), the model shows explanatory significance ( and accounts for 4.1% of the variance in Physicians’ Patient-centered care. However, none of the interaction terms ROC*Title, GOC*Title, SOC*Title, IOC*Title, TRO*Title, or DTC*Title show significance (p > 0.05), indicating that hypotheses H4a, H4b, H4c, H4 d, H5a, and H5b are not supported. Notably, EWS*Title has a significant negative effect on Physicians’ Patient-centered care (), and EDP*Title also negatively impacts Physicians’ Patient-centered care ().

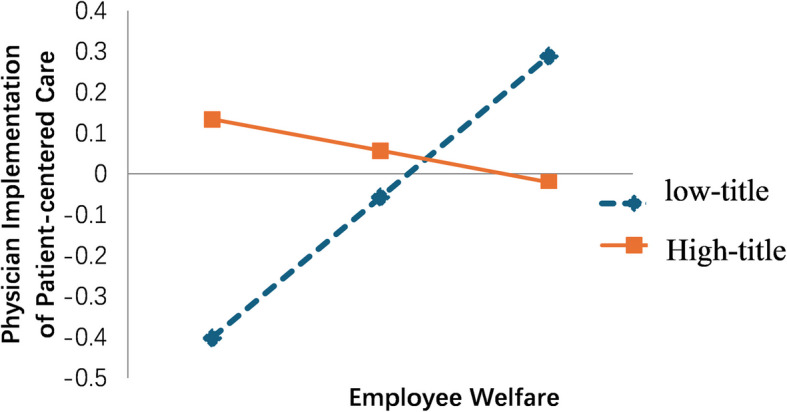

As shown in Fig. 1, the x-axis represents the independent variable of employee welfare systems, while the y-axis indicates the dependent variable of Physicians’ Patient-centered care, with the moderating variable being physician title. This study standardizes the regression coefficients for the low and high groups of employee welfare systems concerning the dependent variable. The values on the y-axis represent the extent of the moderating effect of physician title on the relationship between employee welfare systems and Physicians’ Patient-centered care. Based on the regression coefficient for physician title (0.057) and the interaction term between physician title and employee welfare systems (−0.211), the moderation effect graph is created. The minimum value for low-title Physicians moderating the relationship is −0.4, and the maximum is 0.285, while for high-title Physicians, the minimum is 0.15 and the maximum is −0.03.

Fig. 1.

The moderating effect of physician rank on the relationship between employee welfare system and physician implementation of patient-centered care

As shown in Fig. 1, the x-axis represents the independent variable of employee welfare systems, while the y-axis indicates the dependent variable of Physicians’ Patient-centered care, with the moderating variable being physician title. This study standardizes the regression coefficients for the low and high groups of employee welfare systems concerning the dependent variable. The values on the y-axis represent the extent of the moderating effect of physician title on the relationship between employee welfare systems and Physicians’ Patient-centered care. Based on the regression coefficient for physician title (0.057) and the interaction term between physician title and employee welfare systems (−0.211), the moderation effect graph is created. The minimum value for low-title Physicians moderating the relationship is −0.4, and the maximum is 0.285, while for high-title Physicians, the minimum is 0.15 and the maximum is −0.03.

Starting with the low group, the positive slope indicates that employee welfare systems positively influence Physicians’ Patient-centered care. However, as the physician title increases from low to high, the impact of employee welfare systems on Physicians’ Patient-centered care behaviors decreases (the slope becomes less steep). This means that the influence of employee welfare systems on Physicians’ Patient-centered care is weakened by physician title, suggesting a negative moderating effect.

The regression results indicate that employee welfare systems positively influence Physicians’ Patient-centered care (). For Physicians with low titles, this positive effect strengthens as employee welfare systems increase. However, for high-title Physicians, there is a diminishing marginal effect as employee welfare systems rise, resulting in a less significant economic incentive. This suggests that lower-title Physicians place greater importance on employee welfare systems, resulting in a stronger impact on their Physicians’ Patient-centered care. For higher-title Physicians, the design of these welfare systems may not align with their core work objectives and values, leading to misaligned incentives. Higher-title Physicians typically face greater management and administrative responsibilities alongside clinical work and research activities. This demanding environment, coupled with a lack of effective psychological support and adequate rest, can lead to burnout. Consequently, direct material incentives may fail to meet their psychological needs and work goals, resulting in a diminished Physicians’ Patient-centered care among higher-title Physicians.

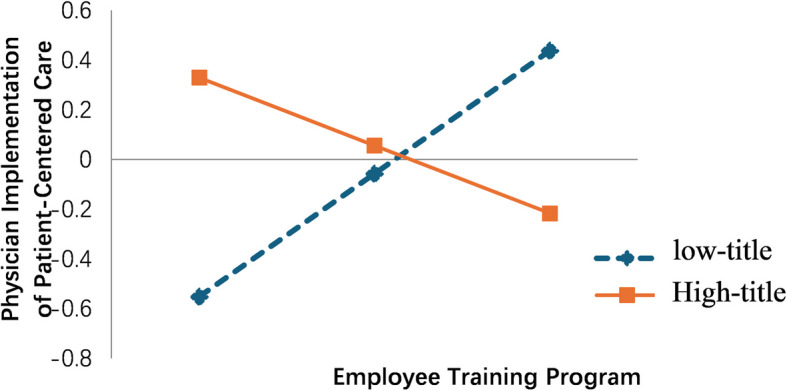

As shown in Fig. 2, the horizontal axis represents the independent variable of employee training programs, while the vertical axis indicates the dependent variable of Physicians’ Patient-centered care, with the moderating variable being Physicians'titles. Similarly, we can illustrate the moderating effect of Physicians'titles on the relationship between employee training programs and the Physicians’ Patient-centered. Starting with the low-title group, the positive slope indicates that employee training programs positively influence Physicians’ Patient-centered care. However, as the title variable shifts from low to high, the impact of employee training programs on Physicians’ Patient-centered care decreases (the slope becomes smaller). This means that the influence of training programs on Physicians’ Patient-centered is weakened by Physicians'titles, demonstrating that higher titles negatively moderate the effect of employee training on the implementation of Physicians’ Patient-centered.

Fig. 2.

The moderating effect of physician rank on the relationship between employee training program and physician implementation of patient-centered care

According to the regression results, employee training programs have a positive overall impact on Physicians’ Patient-centered care (). After adding the moderating variable of Physicians'titles, it is evident that, among low-title Physicians, employee training programs positively influence the implementation of Physicians’ Patient-centered care, with increasingly significant motivational effects as training levels rise. In contrast, among high-title Physicians, the increase in training levels shows diminishing marginal effects, and the motivational impact is not significant. Notably, the slope reduction for the moderating variable of Physicians'titles is more pronounced as it shifts from low to high levels, indicating a stronger diminishing marginal effect. This suggests that high-title Physicians, having already achieved greater professional status, pay less attention to training programs compared to their low-title counterparts, further reinforcing the stronger influence of training programs on Physicians’ Patient-centered among low-title Physicians. For high-title Physicians, the design of employee training programs may not align with their actual work needs or may be too basic, leading them to perceive the training as unhelpful and a waste of time. This can create resistance to training and diminish their motivation to implement Physicians’ Patient-centered care in their work. Additionally, high-title Physicians often possess strong intrinsic motivation and professional pride. If training programs are overly prescriptive, they may undermine their autonomy and intrinsic motivation, resulting in reduced initiative in Physicians’ Patient-centered care. Furthermore, frequent training can increase work-related stress, especially if these programs do not account for their workload. A sustained high-pressure environment can lead to burnout, reducing high-title Physicians'engagement in Physicians’ Patient-centered care, which require significant emotional and psychological investment. Consequently, there is a stronger diminishing marginal effect among high-title Physicians.

Discussion

Based on the theory of organizational behavior [31], especially the significant influence of leadership style and group behavior on individual behavior, this study explores how organizational behavior in hospitals [32–37] affects doctors'clinical practice [21–26, 38, 39] and establishes a conceptual model. This study defined the organizational behavior of hospitals at both macro and micro levels, using samples from ten large public hospitals. Through the questionnaire survey, it collected data on eight independent variables, including hospital organizational culture, change behavior and incentive practice, as well as the moderating variable of doctor titles. Furthermore, in order to rule out the potential influence of personality traits on doctors'patient-centered care, these traits are regarded as control variables. Then, descriptive statistics, correlation analysis and multicollinearity test were conducted using SPSS software, and then multiple linear regression analysis was carried out to explore how these variables affect doctors'patient-centered care.

Existing studies have revealed the association between organizational behavior and hospital performance. For example, in terms of the impact of organizational culture on performance, Braithwaite [36] found that organizational behavior significantly affects hospital culture and shapes task scheduling and discussion methods. His research emphasizes the importance of understanding the multi-faceted nature of culture in the healthcare environment, demonstrating that organizational culture can promote innovation, improvement or maintain the status quo. However, most of the existing studies remain at the performance correlation at the organizational level and rarely involve the micro-mechanisms of individual doctors'behaviors.

Zhang Y and Dare PS [37] explored how organizational culture coordinates the role of human resource management in achieving innovative performance in healthcare institutions, emphasizing the importance of organizational culture, organizational climate, and healthcare management in promoting sustainable innovative performance. Rotia, C. C. and Ploscaru [32] examined the direct and indirect relationships between human resource management practices and organizational performance, highlighted the mediating role of the organizational change process, and found that human resource management practices directly affect organizational performance and have an indirect impact through these change processes. These studies provide a framework for the role of macro organizational behavior, but have not yet answered the key question of"How organizational behavior specifically affects doctors'patient-centered diagnosis and treatment behavior".

Furthermore, Chmielewska and Stokwiszewski [34] discovered that there is a relationship between doctors'work motivation and the organizational performance of public hospitals; Deressa and Zeru [35] found that nurses'motivation improved job performance, job satisfaction, team spirit, patient satisfaction and job engagement, and pointed out the importance of financial incentives and professional recognition. However, most of the existing studies focus on the direct relationship between"motivation and performance", and there is a lack of detailed exploration of the influence mechanism of doctors'PCC, a specific practical behavior. Especially, the interaction between external organizational behaviors and doctors'internal motivation is still unclear.

The research results of various scholars show that in the field of health care, the multidimensional relationship between organizational behavior, employee motivation and hospital performance has great significance. However, once we focus on the subfield of how organizational behavior concretely affects individual physician behavior, we can find that there are obvious shortcomings in relevant research. Current research on individual physician behavior tends to explore the impact of organizational behavior on physicians'perceived behavior. Indicators such as job satisfaction and loyalty have attracted most research attention, while PCC diagnosis and treatment behavior, which is directly related to medical service quality and patient experience, has rarely been deeply explored. At the same time, in view of the influencing factors behind doctors'diagnosis and treatment behavior and its formation mechanism, existing studies focus on exploring doctors'internal factors (such as motivation theory and sense of accomplishment) [21–23], and pay little attention to the influence of external organizational behavior on doctors'behavior. Physician behavior is influenced by both internal (e.g., self-efficacy, achievement motivation) and external (medical institution resources, policies, leadership strategies, style) factors [22, 24–26]. In addition, current researches on individual physician behavior mostly focus on job satisfaction to improve hospital performance, while there are few researches on physician PCC behavior [27–30]. On the one hand, this theoretical gap makes it difficult for us to understand why there are differences in physician PCC behavior in seemingly the same organizational environment. On the other hand, it also greatly limits the precise implementation of organizational management strategies, and can not achieve effective intervention and optimization of diagnosis and treatment behaviors.

The results of this study indicate that (1) the study of the 10 large public hospitals revealed a coexistence of four types of organizational cultures. Support-oriented and innovation-oriented cultures were dominant, followed by rule-oriented cultures, while goal-oriented cultures scored relatively low. Additionally, these hospitals showed effective organizational change behaviors in technology and resource optimization, as well as inter-professional teamwork. Incentives related to employee welfare systems and development programs also demonstrated high implementation effectiveness.(2) Supportive and innovation-oriented hospital cultures positively influence Physicians’ Patient-centered care, while goal-oriented cultures negatively impact Physicians’ Patient-centered care (3) In public hospitals, organizational change behaviors such as technology and resource optimization, along with inter-professional teamwork, positively influence Physicians’ Patient-centered care. Additionally, organizational incentives like employee welfare systems and training programs enhance Physicians’ Patient-centered care.(4) The moderating variable of physician title negatively affects the relationship between the employee welfare system and Physicians’ Patient-centered care, as well as the relationship between the staff development program and Physicians’ Patient-centered care.

The findings of this study provide important insights into the complex relationship between hospital organizational behavior and Physicians’ Patient-centered care. By examining the dimensions of organizational culture, change behavior, and incentive mechanisms, this research enhances our understanding of how these factors influence Physicians’ Patient-centered care.

Conclusions

Based on the theory of organizational behavior, especially the significant impact of organizational leadership style and group behavior on individual behavior, this paper discusses the impact of hospital organizational behavior on doctors'diagnosis and treatment behavior, and builds a conceptual model. The research on the influencing factors and formation mechanism of doctors'PCC treatment behavior and the influence of organizational behavior on doctors'patient-centered nursing behavior were added.

The study defined hospital organizational behavior from macro and micro levels, and took 10 large public hospitals as research samples. Through questionnaire survey, this paper collected eight independent variables including hospital organizational culture, hospital change behavior and hospital incentive behavior, and mediating variables including doctor titles. This study highlights the critical role of hospital organizational behavior in shaping physician PC clinical practice. By creating a supportive organizational culture, implementing effective change behaviors, and developing targeted incentives, hospitals can improve the quality of care that patients receive. In addition, recognizing individual differences among physicians can lead to more targeted and effective management strategies. As the healthcare environment continues to evolve, understanding these dynamics is critical to improving patient outcomes and satisfaction.

Theoretical Implications: (1)To construct a theoretical framework for the influence of organizational behavior on doctors'PC diagnosis and treatment behavior. By analyzing the action paths of hospital organizational culture, change behaviors and incentive mechanisms on doctors'PC diagnosis and treatment behaviors, the application dimensions of organizational behavior in medical scenarios have been expanded, providing a new perspective for understanding the internal dynamic mechanism of medical organizations. (2) Refine the mechanism of organizational behavior in the medical field. Focus on specific medical professional scenarios, reveal the differentiated influences of different organizational cultures and management strategies on doctors'PC diagnosis and treatment behaviors, promote the deepening of medical service theories towards professionalization and personalization, and provide theoretical support for precise management strategies; (3) Promote the integration of interdisciplinary research: By integrating theories from organizational behavior, medical management, and psychological science, and analyzing the complex interaction between organizational behavior and doctors'diagnosis and treatment behaviors from a multi-disciplinary perspective, it enriches the methodological tools for medical management research and lays the foundation for subsequent interdisciplinary exploration.

Policy Implications: (1) Optimize hospital management strategies. Provide a scientific path for managers, enhance the management efficiency of the doctor team, and directly affect the improvement of the efficiency and quality of medical services; (2) Strengthen the cross-professional collaboration mechanism. By analyzing the promoting effect of teamwork on the diagnosis and treatment behavior of PC, guide medical institutions to optimize the internal collaboration model, improve the collaborative efficiency of the diagnosis and treatment process, and thereby improve the patient experience and treatment effect; (3) Promote the upgrading of medical service quality. By improving organizational behavior, provide practical solutions for hospitals to reduce resource waste, lower excessive medical treatment, and enhance the satisfaction of patients and staff, thereby strengthening market competitiveness; (4) Support the formulation of medical policies. Provide empirical basis for policymakers, assist in improving the relevant systems of PC medical services, and promote the transformation of the industry as a whole to a patient-centered service model; (5) Empower innovative practices in the medical industry. Output innovative management strategies from the perspectives of organizational structure and group behavior, providing theoretical and practical guidance for the continuous innovation of technology, services and management models, and promoting the transformation of the healthcare industry.

Future research can be further developed in the following directions: (1) Integrating online and offline data (such as sentiment analysis technology) to evaluate differences in diagnosis and treatment patterns; (2) Expand the range of data collection (such as data crawler) to compare the influence of organizational behavior of hospitals of different grades/nature; (3) Construct a multidimensional theoretical model to quantify the moderating/mediating variables (such as doctor's mental state); (4) Research on organizational culture differences in specific departments (classified by disease type); (5) The system identifies the core factors driving PC diagnosis and treatment in the organizational behavior of hospitals, such as the dynamic interaction effect of incentive mechanism and change strategy.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks Jianchao Wang and Yang Liu who provided supports in data collection and project management. We have obtained written permission from the individuals mentioned above.

Authors'contributions

Concept and design: P.Z. and H.Z. Acquisition of data: A.W. and H. Z. Analysis and interpretation:H. Z. Drafting of manuscript:H.Z. and P. Z. Critical revision of paper for important content: All authors Statistical analysis: Z.H. Obtaining of funding: P. Z. Supervision: P. Z.

Funding

This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Shaanxi Province, China (Grant No.: 2023-JC-YB-613), Social Science Foundation of Shaanxi Province, China (Grant No.: 2023R017).

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Our study did not require further ethics committee approval as it did not involve animal or human clinical trials and was not unethical. Consent to Participate All respondents were informed about the study and its potential risks and benefits prior to participation. Respondents had to sign an informed consent to participate in the study and to have their data used to develop the results contained in this paper. In addition, participation was voluntarily and the participant could stop at any time.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Kwame A, Petrucka PM. A literature-based study of patient-centered care and communication in nurse-patient interactions: barriers, facilitators, and the way forward. BMC Nurs. 2021;20:158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bokhour BG, Fix GM, Mueller NM, Barker AM, Lavela SL, Hill JN, et al. How can healthcare organizations implement patient-centered care? Examining a large-scale cultural transformation. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18:168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bauder L, Giangobbe K, Asgary R. Barriers and Gaps in Effective Health Communication at Both Public Health and Healthcare Delivery Levels During Epidemics and Pandemics; Systematic Review. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2023;17: e395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang D, Ai X, Cai M, Tong Q, Mei K, Yang Q, et al. Research on doctor-patient communication teaching for oncology residents: a new teaching model. J Eval Clin Pract. 2024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Liu X, Zeng J, Li L, Wang Q, Chen J, Ding L. The Influence of Doctor-Patient Communication on Patients’ Trust: The Role of Patient-Physician Consistency and Perceived Threat of Disease. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2024;17:2727–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brickley B, Williams LT, Morgan M, Ross A, Trigger K, Ball L. Patient-centred care delivered by general practitioners: a qualitative investigation of the experiences and perceptions of patients and providers. BMJ Qual Saf. 2022;31:191–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dyb K, Berntsen GR, Kvam L. Adopt, adapt, or abandon technology-supported person-centred care initiatives: healthcare providers’ beliefs matter. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21:240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ekman I, Ebrahimi Z, Olaya CP. Person-centred care: looking back, looking forward. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2021;20:93–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mead N, Bower P. Patient-centredness: a conceptual framework and review of the empirical literature. Soc Sci Med. 2000;51:1087–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garfield S, Etkind M, Franklin BD. Using patient and carer perspectives to improve medication safety at transitions of care. BMJ Qual Saf. 2023;bmjqs-2023–016801. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Grudniewicz A, Gray CS, Boeckxstaens P, De Maeseneer J, Mold J. Operationalizing the Chronic Care Model with Goal-Oriented Care. Patient. 2023;16:569–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnsen S. Patient-Centered Care in Action: How Clinicians Respond to Patient Dissatisfaction with Contraceptive Side Effects. J Health Soc Behav. 2024;221465241262029. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Edgman-Levitan S, Schoenbaum SC. Patient-centered care: achieving higher quality by designing care through the patient’s eyes. Isr J Health Policy Res. 2021;10:21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Soo J, Jameson J, Flores A, Dubin L, Perish E, Afzal A, et al. Does the Doctor-Patient Relationship Affect Enrollment in Clinical Research? Acad Med. 2023;98:S17-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cosey-Gay F, Johnson D Sr, Perez E, Milkovich R, Robles C, Rogers SO Jr. Strengthening Doctor-Patient Relationships Through Hospital-Based Violence Interventions. Acad Med. 2023;98:S69-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Riboulet M, Clairet A-L, Bennani M, Nerich V. Patient Preferences for Pharmacy Services: A Systematic Review of Studies Based on Discrete Choice Experiments. Patient. 2024;17:13–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marshall DA, Suryaprakash N, Lavallee DC, Mccarron TL, Zelinsky S, Barker KL, et al. Studying How Patient Engagement Influences Research: A Mixed Methods Study. Patient. 2024;17:379–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holmér S, Nedlund A-C, Thomas K, Krevers B. How health care professionals handle limited resources in primary care – an interview study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2023;23:6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu Y, Wang P, Bai Y. The influence factors of medical disputes in Shanghai and implications - from the perspective of doctor, patient and disease. BMC Health Serv Res. 2022;22:1128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xiong X, Cao X, Luo L. The ecology of medical care in Shanghai. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21:51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gupta DM, Boland RJ, Aron DC. The physician’s experience of changing clinical practice: a struggle to unlearn. Implementation Sci. 2017;12:28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schuttner L, Hockett Sherlock S, Simons C, Ralston JD, Rosland A-M, Nelson K, et al. Factors affecting primary care physician decision-making for patients with complex multimorbidity: a qualitative interview study. BMC Prim Care. 2022;23:25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.West CP, Shanafelt TD. The influence of personal and environmental factors on professionalism in medical education. BMC Med Educ. 2007;7:29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Trybou J, De Caluwé G, Verleye K, Gemmel P, Annemans L. The impact of professional and organizational identification on the relationship between hospital–physician exchange and customer-oriented behaviour of physicians. Hum Resour Health. 2015;13:8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Körner M, Wirtz MA, Bengel J, Göritz AS. Relationship of organizational culture, teamwork and job satisfaction in interprofessional teams. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15:243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sehanovic L, Hadziahmetovic N, Kurtcehajic A. IMPACT OF LEADERSHIP STYLES ON EMPLOYEE BEHAVIOR IN HEALTHCARE INSTITUTIONS DURING THE COVID-19. Journal Human Research in Rehabilitation. 2022;12:171–3. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Queenan CC, Angst CM, Devaraj S. Doctors’ orders–If they’re electronic, do they improve patient satisfaction? A complements/substitutes perspective J Oper Manag. 2011;29:639–49. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu H, Deng Z, Wang B, Wu T. Online service qualities in the multistage process and patients’ compliments: A transaction cycle perspective. Inf Manage. 2020;57: 103230. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zahedi FM, Zhao H, Sanvanson P, Walia N, Jain H, Shaker R. My Real Avatar has a Doctor Appointment in the Wepital: A System for Persistent, Efficient, and Ubiquitous Medical Care. Inf Manage. 2022;59: 103706. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu S, Zhang M, Gao B, Jiang G. Physician voice characteristics and patient satisfaction in online health consultation. Inf Manage. 2020;57: 103233. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moon SE, Van Dam PJ, Kitsos A. Measuring Transformational Leadership in Establishing Nursing Care Excellence. Healthcare. 2019;7:132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rotea CC, Ploscaru A-N, Bocean CG, Vărzaru AA, Mangra MG, Mangra GI. The Link between HRM Practices and Performance in Healthcare: The Mediating Role of the Organizational Change Process. Healthcare. 2023;11:1236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fahlevi M, Aljuaid M, Saniuk S. Leadership Style and Hospital Performance: Empirical Evidence From Indonesia. Front Psychol. 2022;13: 911640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chmielewska M, Stokwiszewski J, Filip J, Hermanowski T. Motivation factors affecting the job attitude of medical doctors and the organizational performance of public hospitals in Warsaw. Poland BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20:701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Deressa AT, Zeru G. Work motivation and its effects on organizational performance: the case of nurses in Hawassa public and private hospitals: Mixed method study approach. BMC Res Notes. 2019;12:213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Braithwaite J, Herkes J, Ludlow K, Testa L, Lamprell G. Association between organisational and workplace cultures, and patient outcomes: systematic review. BMJ Open. 2017;7: e017708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang Y, Dare PS, Saleem A, Chinedu CC. A sensation of COVID-19: How organizational culture is coordinated by human resource management to achieve organizational innovative performance in healthcare institutions. Front Psychol. 2022;13: 943250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dyrbye LN, Major-Elechi B, Hays JT, Fraser CH, Buskirk SJ, West CP. Relationship Between Organizational Leadership and Health Care Employee Burnout and Satisfaction. Mayo Clin Proc. 2020;95:698–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Salvatore D, Numerato D, Fattore G. Physicians’ professional autonomy and their organizational identification with their hospital. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18:775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.