Abstract

Purpose

Previous studies have suggested that serum uric acid (SUA), a byproduct of purine metabolism, may be associated with cancer development. However, the relationship between SUA levels and skin cancers—malignant melanoma (MM) and non-melanoma skin cancer (NMSC)—remains poorly understood. The main purpose of this study is to investigate the relationship between serum uric acid levels and the risk of malignant melanoma and non-melanoma skin cancer.

Patients and Methods

This research examined NHANES data (1999–2020) to explore the association between serum uric acid levels and skin cancer risk in a cohort of 1219 patients (336 mm cases and 883 NMSC cases). Using Mendelian randomization (IVW as primary method, MR-Egger and weighted median as secondary approaches), GWAS data evaluated causality. Sensitivity tests were conducted to ensure the robustness of the findings, while RCS models were used to analyze nonlinear exposure-outcome relationships. Multivariable regression models were employed to adjust for age, sex, race, lifestyle, and comorbidities, thereby isolating the independent effect of serum uric acid.

Results

High serum uric acid (SUA) levels are strongly linked to increased risks of MM and NMSC, particularly in women and Mexican American populations. Risk trends vary at different SUA thresholds, and elevated levels are tied to other negative health outcomes. However, no causal relationship between SUA levels and skin cancer has been established.

Conclusion

This study addresses gaps in prior research by revealing a significant association between high serum uric acid (SUA) levels and increased risks of both malignant melanoma (MM) and non-melanoma skin cancer (NMSC). Notably, SUA may serve as a valuable biomarker for risk assessment, particularly among women and Mexican Americans. Even so, further research is needed to better understand the biological mechanisms underlying SUA’s role in skin cancer development.

Keywords: observational studies, risk factor, cancer, NHANES, Mendelian randomization analysis

Introduction

Skin cancer ranks among the most prevalent malignant neoplasms worldwide and is primarily classified into two principal categories: malignant melanoma (MM) and non-melanoma skin cancer (NMSC). MM originates from melanocytes in the skin, while NMSC arises from keratinocytes.1 NMSC can be further subdivided into basal cell carcinoma (BCC), squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), and other rare common subtypes. Melanoma is characterized by its aggressive proliferative nature, invasiveness, and high metastatic potential.2 In contrast, BCC typically exhibits slow growth and a low propensity for metastasis.3 Certain subtypes of SCC, however, demonstrate significant invasiveness and a relatively higher potential for metastasis.4 According to the Cancer Research Institute approximately 100,000 new cases of malignant skin tumors are reported annually, as per the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program (data from 2022).5 The incidence of skin cancer is influenced by multiple factors, including population aging, occupational exposure, and recreational ultraviolet (UV) radiation exposure.6 Despite the extensive availability of preventive measures, skin cancer rates remain high. Additionally, early screening and timely diagnosis within high-risk populations continue to present substantial challenges. In this sense, the identification of new biomarkers is of great importance for improving the early diagnosis of skin cancer.

Serum uric acid (SUA), a common antioxidant molecule in human blood, is produced through the oxidation of xanthine and hypoxanthine by xanthine oxidoreductase (XOR),7 and is primarily excreted via the kidneys and intestines.8 There is evidence suggesting that elevated blood uric acid levels may play a role in metabolic regulation and are associated with the pathogenesis of various diseases, including cancer.9 Furthermore, populations with high uric acid levels may be at an increased of skin cancer.10,11 Long-term follow-up studies have shown that the incidence of skin cancer is significantly higher in patients with gout compared to the general population.12 To date, no studies have examined the potential causal relationship or correlation between SUA levels and the risk of MM and NMSC.

The Mendelian randomization (MR) method, which utilizes genetic variation as an instrumental variable (IV), offers a robust framework for addressing reverse causality and confounding factors commonly encountered in observational studies.13 This method capitalizes from the random distribution of genetic variation and its temporal precedence, rendering it a potent tool for probing potential causal relationships.14 In this study, MR is employed to examine whether genetically predicted serum uric acid concentration is causally linked to skin cancer risk. Additionally, leveraging data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), we evaluate the influence of serum uric acid concentration on the incidence of MM and NMSC. This study furnishes empirical evidence to elucidate for the relationship between serum uric acid concentration and skin cancer risk, offering critical insights for the prevention and treatment of skin cancer.

Materials and Methods

Research Process

The research is organized into two parts, The first part, observational study, involves: participants selected from NHANES, a comprehensive survey conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) under the auspices of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). As a nationally representative survey, HANES data encompasses non-institutionalized individuals of all age groups across the United States. Collecting data on demographics, socioeconomic status, health-related variables, and healthcare utilization. The NHANES data (1999–2020) utilized in this study underwent rigorous ethical review. Conducted biennially, the survey employes a stratified, multistage probability sampling method to ensure representative sampling. More details regarding NHANES can be found on the CDC official website (https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/index.htm). Subsequently, a genetic instrumental variable analysis was conducted to examine the causal relationship between the two variables.

Gwas Data Collection

In this study, serum uric acid (SUA) served as the exposure variable, while MM and NMSC as outcome variables. Instrumental variables (IVs) were identified by selecting SNPs linked to SUA (P < 5 × 10⁻8), with an LD threshold (r² > 0.001 within 10,000 kb) to mitigate bias. After excluding SNPs in linkage disequilibrium and those weakly associated with serum uric acid levels, we selected 239 and 237 independent SNPs as genetic instrumental variables for malignant melanoma and non-melanoma skin cancer, respectively. The analysis adhered to the three assumptions of two-sample MR. GWAS summary stats for SUA were sourced from the UK Biobank, Japan Biobank, and Finnish databases (GWAS ID: ebi-a-GCST90018977),15 with the exposure cohort comprising 343,836 samples and 19,041,286 SNPs from European populations. Skin cancer data were obtained from FinnGen consortium. The NMSC group had 23,503 patients and 345,118 controls, and the MM group had 3932 patients and 345,118 controls.

Instrumental Variable Selection

To guarantee the robustness and validity of the analysis, it is imperative to meticulously select instrumental variables (IVs) that satisfy these assumptions. For the selection of IVs, we initially identified single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) that exhibited a strongly association with SUA. To minimize the risk of bias introduced by weak instrumental variables, SNPs with an F-statistic below 10 were excluded.16 The formula for calculating the F-statistic is as follows:

|

R2 indicates the share of variance in the exposure accounted for by each instrumental variable (IV), and N refers to the sample size:

|

Here, β represents the effect size of the allele, and EAF denotes the effect allele frequency. To ensure the independence of instrumental variables (IVs), a clumping process was applied, given the potential for strong linkage disequilibrium (LD) among SNPs, which could introduce bias. The clumping parameters were set to an R2 threshold of 0.001 and a physical window of 10,000 kilobases (kb). This step ensures the independence of IVs and minimizes the risk of spurious associations due to LD. Finally, to exclude confounding factors and uphold the exclusion restriction assumption, we used Phenoscanner V2, a tool designed to identify SNPs associated with potential confounders or outcomes. This step ensures that the IVs exert their influence on the outcome exclusively through their effect on SUA levels, thereby minimizing confounding bias.

MR Evaluation Methods

Three Mendelian randomization (MR) methods—inverse variance weighting (IVW), MR-Egger regression, and weighted median (WM)—were utilized to explore the causal link between serum uric acid (SUA) levels and cancer risk. IVW was employed as the primary method, with MR-Egger and WM validating its results. Consistent and robust findings across all methods would substantiate SUA’s potential role as a predictive or protective determinant for Malignant melanoma (MM) and non-melanoma skin cancer (NMSC).

To ensure the reliability of the analysis, scatter plots and Egger regression were adopted to assess horizontal pleiotropy, while funnel plots and Cochran’s Q statistics were utilized to evaluate SNP heterogeneity. Moreover, a leave-one-out analysis was conducted to identify influential SNPs. In case of instability, additional cohort data from the IEU Open GWAS Project were incorporated and analyzed using the same MR techniques.

These approaches were designed to yield robust evidence for the causal link between the exposure and the outcome. Statistical analyses were performed using R (version 4.4.2) and associated packages, including TwoSampleMR.

Variable Selection for Observational Studies

Measurements

Drawing upon the existing research,17 Serum uric acid (SUA) levels were stratified by sex and categorized into three distinct groups: Low SUA group: <5.0 mg/dL for men and <4.0 mg/dL for women; Normal SUA group: 5.0 to <7.0 mg/dL for men and 4.0 to <6.0 mg/dL for women. High SUA group: ≥7.0 mg/dL for men and ≥6.0 mg/dL for women. A subgroup analysis was performed to delve into the relationship between varying SUA concentrations and the risk of skin cancer. A two-sided p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Definitions

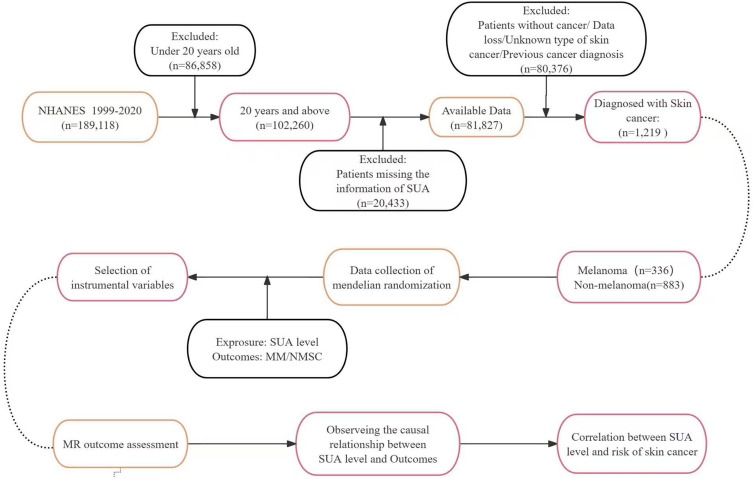

To explore the association between hyperuricemia and skin cancer, we conducted a retrospective analysis using the NHANES dataset from 1999 to 2020, which spans 11 cycles. Initially, 189,118 participants were enrolled. After applying exclusion criteria for age, missing data, and cancer status, the final analysis cohort comprised 1219 individuals (336 malignant melanoma cases and 883 non‑melanoma skin cancer cases). Specifically, participants younger than 20 years (n = 86,858) were excluded, yielding 102,260 adults. Those with missing serum uric acid measurements (n = 20,433) were then removed, leaving 81,827 participants. Next, individuals without a confirmed cancer diagnosis, with unknown cancer type, or with missing cancer information (n = 80,376) were excluded. Finally, participants reporting any physician‑diagnosed malignancy other than skin cancer prior to SUA measurement were excluded. Cancer data were obtained from self-reported responses to the question: “What kind of cancer was it?” only participants who reporting MM or NMSC were included in the analysis. A total of 336 cases of MM were identified, with 184 (55%) male and 152 (45%) female. For the 883 cases of NMSC, 55% were male and 45% were female.

Covariate Selection

Covariate selection was informed by an extensive review of the prior literature. Continuous variables, such as age and BMI, were included. While categorical variables—covering ethnicity, smoking status, alcohol use, education, hypertension, high cholesterol, and diabetes were considered to evaluate their impact on the primary outcomes.18,19

Observational Analysis

All analyses accounted for the intricate sampling design of NHANES to ensure nationally representative estimates.20 The baseline characteristics of participants were described using the mean (95% confidence interval) for continuous variables and percentage frequencies (95% confidence interval) for categorical variables.

This study employed restricted cubic spline (RCS) functions to analyze the nonlinear relationship between SUA levels and the risks of MM and NMSC. A p-value < 0.05 was indicative of a statistically nonlinear relationship.21,22 Also, multivariable logistic regression was used to evaluate the association between SUA levels and outcomes.

Results

Characteristics of the Included Population

From the 1999–2020 NHANES database, our study initially included 189,118 participants. After excluding 86,858 individuals under the age of 20. 20,433 participants with missing serum uric acid (SUA) data, and 80,376 individuals without a cancer diagnosis or with incomplete data, a total of 1219 participants diagnosed with skin cancer were included in the final analysis. This group consisted of 336 mm cases and 883 NMSC cases. The flowchart is presented in (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria Flowchart.

This study classified the US population into three groups based on serum uric acid (SUA) levels: normal, low, and high, to assess demographic and clinical differences affecting risks of MM and NMSC. Findings showed that men and women with high SUA were older (men: 50 ± 18 years, women: 56 ± 19 years, both p < 0.001) and had higher BMIs (p < 0.001). Lifestyle habits indicated that 82.6% of men with high SUA consumed alcohol frequently, and 56.2% had a history of smoking. Racial demographics showed a predominance of Mexican Americans and African Americans in the low SUA group, while non-Hispanic Whites were more common in the high SUA group (p < 0.001). Educational attainment was lower among those with high SUA (p < 0.001). Health conditions such as hypertension and high cholesterol were more prevalent in individuals with high SUA (p < 0.001), along with an increased prevalence of diabetes. In the malignant melanoma group, women were more likely to develop malignant melanoma (male: p = 0.0813, female: p = 0.0383). In the non-melanoma group, both men and women developed non-melanoma skin cancer. The data showed that the correlation between changes in blood uric acid levels and the incidence of non-melanoma skin cancer was higher in men than in women (male: p = 0.004; female: p = 0.006). These results suggest a potential link between SUA levels and MM and NMSC risks (Table 1).

Table 1.

US Population Characteristics by SUA Level

| Characteristic | Male | Female | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal SUAa | Lower SUAa | Higher SUAa | P | Normal SUAa | Lower SUAa | Higher SUAa | P | |

| Age, year | 50 ± 19 | 51 ± 19 | 50 ± 18 | <0.001b | 50 ± 19 | 45 ± 18 | 56 ± 19 | <0.001b |

| BMI (Kg/2) | 27.5 ± 5.7 | 25.4 ± 5.5 | 30.1 ± 6.4 | <0.001b | 29 ± 7 | 26 ± 6 | 32 ± 8 | <0.001b |

| Smoking status | ||||||||

| Over 100 cigarettes | 9928 (53.6%) | 1921 (50.4%) | 7670 (56.2%) | 7984 (40.5%) | 4485 (33.9%) | 2948 (46.4%) | ||

| No | 8583 (46.3%) | 1886 (49.5%) | 5967 (43.7%) | 11,729 (59.5%) | 8717 (66.0%) | 3398 (53.5%) | ||

| Refused | 4 (0.0%) | 2 (0.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (0.0%) | 2 (0.0%) | 1 (0.0%) | ||

| Don't know | 16 (0.1%) | 3 (0.1%) | 11 (0.1%) | 11 (0.1%) | 9 (0.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | ||

| Alcohol consumption | ||||||||

| Over 12 alcohol drinks/year | 9807 (80.4%) | 1609 (72.5%) | 7569 (82.6%) | 7643 (60.8%) | 5056 (59.5%) | 2295 (59.2%) | ||

| No | 2384 (19.5%) | 609 (27.4%) | 1584 (17.3%) | 4917 (39.1%) | 3436 (40.4%) | 1575 (40.7%) | ||

| Don't knows | 7 (0.1%) | 1 (0.0%) | 7 (0.1%) | 11 (0.1%) | 7 (0.1%) | 4 (0.1%) | ||

| Race | <0.001c | <0.001c | ||||||

| Mexican American | 4493 (22.2%) | 1167 (24.8%) | 2479 (17.6%) | 4296 (19.9%) | 3300 (23.0%) | 1151 (16.7%) | ||

| Other Hispanic | 1133 (5.6%) | 164 (3.5%) | 767 (5.4%) | 1268 (5.9%) | 1070 (7.5%) | 225 (3.3%) | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | 8971 (44.4%) | 1997 (42.5%) | 6569 (46.5%) | 9543 (44.2%) | 6171 (43.1%) | 3137 (45.4%) | ||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 4185 (20.7%) | 1137 (24.2%) | 3180 (22.5%) | 4897 (22.7%) | 2798 (19.5%) | 1963 (28.4%) | ||

| Other Race | 1421 (7.0%) | 237 (5.0%) | 1127 (8.0%) | 1575 (7.3%) | 979 (6.8%) | 427 (6.2%) | ||

| Education | ||||||||

| High school education | 4878 (24.2%) | 1212 (25.8%) | 3527 (25.0%) | 5537 (25.7%) | 3349 (23.4%) | 1961 (28.5%) | ||

| University degree | 4832 (24.0%) | 1057 (22.5%) | 3715 (26.3%) | 6103 (28.3%) | 3986 (27.9%) | 1838 (26.7%) | ||

| College degree or above | 3610 (17.9%) | 526 (11.2%) | 2630 (18.6%) | 3328 (15.4%) | 2757 (19.3%) | 711 (10.3%) | ||

| High blood pressure | <0.001c | <0.001c | ||||||

| Yes | 5465 (28.4%) | 989 (23.6%) | 5676 (40.9%) | 6932 (33.6%) | 2667 (19.6%) | 3743 (56.0%) | ||

| No | 13,741 (71.4%) | 3195 (76.2%) | 8195 (59.0%) | 13,629 (66.2%) | 10,945 (80.3%) | 2921 (43.7%) | ||

| Don't know | 28 (0.1%) | 8 (0.2%) | 20 (0.1%) | 42 (0.2%) | 25 (0.2%) | 19 (0.3%) | ||

| High cholesterol level | ||||||||

| Yes | 5459 (39.1%) | 992 (35.5%) | 4553 (42.3%) | 6191 (39.6%) | 2865 (29.4%) | 2564 (49.4%) | ||

| No | 8396 (60.1%) | 1775 (63.5%) | 6114 (56.9%) | 9334 (59.8%) | 6829 (70.1%) | 2562 (49.4%) | ||

| Don't know | 110 (0.8%) | 28 (1.0%) | 84 (0.8%) | 90 (0.6%) | 52 (0.5%) | 61 (1.2%) | ||

| Diabetes | ||||||||

| Yes | 2009 (10.6%) | 546 (12.1%) | 1464 (11.2%) | 1925 (9.5%) | 901 (6.7%) | 1107 (16.8%) | ||

| No | 16,575 (87.7%) | 3938 (86.9%) | 11,354 (86.5%) | 17,893 (88.8%) | 12,340 (92.3%) | 5319 (80.8%) | ||

| Borderline | 291 (1.5%) | 42 (0.9%) | 305 (2.3%) | 330 (1.6%) | 127 (0.9%) | 154 (2.3%) | ||

| Don't know | 20 (0.1%) | 5 (0.1%) | 3 (0.0%) | 11 (0.1%) | 8 (0.1%) | 5 (0.1%) | ||

| MM | 0.081c | 0.038c | ||||||

| Yes | 85 (0.4%) | 18 (0.4%) | 81 (0.6%) | 79 (0.4%) | 39 (0.3%) | 34 (0.5%) | ||

| No | 20,118 (99.6%) | 4684 (99.6%) | 14,041 (99.4%) | 21,500 (99.6%) | 14,279 (99.7%) | 6869 (99.5%) | ||

| NMSC | 0.004 | 0.006 | ||||||

| Yes | 270 (1.3%) | 35 (0.7%) | 178 (1.3%) | 206 (1.0%) | 110 (0.8%) | 84 (1.2%) | ||

| No | 19,933 (98.7%) | 4667 (99.3%) | 13,944 (98.7%) | 21,373 (99.0%) | 14,208 (99.2%) | 6819 (98.8%) | ||

Notes: aMean ± SD; n (%). bOne-way ANOVA. cPearson’s Chi-squared test.

In conclusion, our study demonstrates significant demographic and clinical differences among individuals with varying SUA levels. Higher SUA levels were associated with older age, higher BMI, cardiovascular risk factors, and increased melanoma prevalence in both males and females. These findings highlight the potential importance of SUA as a risk factor for melanoma and underscore the need for further investigation into the underlying mechanisms.

The Relationship Between SUA Level and Outcomes

Table 2 presents the results of three regression models analyzing the relationship between serum uric acid (SUA) levels and the risk of Malignant melanoma (MM) and non-melanoma skin cancer (NMSC). In the unadjusted model, SUA showed a significant positive association with melanoma risk (OR = 1.19, 95% CI = 1.12–1.28, P < 0.001), suggesting that each 1 mg/dL increase in SUA raised melanoma risk by 19%. A similar trend was observed for NMSC, where every 1 mg/dL increase in SUA was associated with a 13% increase in risk (OR = 1.13, 95% CI = 1.08–1.18, P < 0.001). In Model 1, after adjusting for age, race, and sex, the significant association between SUA and melanoma risk persisted (OR = 1.13, 95% CI = 1.05–1.21, P = 0.001), indicating a 13% increase in melanoma risk per 1 mg/dL increase in SUA. For NMSC, the association weakened but remained statistically significant (OR = 1.05, 95% CI = 1.00–1.10, P = 0.045), reflecting a 5% increase in risk. In Model 2, after further adjustment for BMI, smoking, alcohol consumption, and education level, the association between SUA and melanoma risk remained significant but was attenuated (OR = 1.09, 95% CI = 1.00–1.19, P = 0.045), suggesting a 9% increase in melanoma risk per 1 mg/dL increase in SUA. However, the association between SUA and NMSC was no longer statistically significant (OR = 1.04, 95% CI = 0.98–1.09, P = 0.184). In Model 3, with additional adjustment for comorbidities such as hypertension, diabetes, and hypercholesterolemia, the association between SUA and melanoma risk was no longer significant (OR = 1.05, 95% CI = 0.95–1.15, P = 0.316). Similarly, the association between SUA and NMSC risk did not reach statistical significance (OR = 1.03, 95% CI = 0.97–1.09, P = 0.28).

Table 2.

Multivariate Logistic Regression Analysis of SUA and MM and NMSC

| Melanoma | P value | Non-Melanoma | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude Model (OR, 95% CI) | 1.19(1.12, 1.28) | <0.001 | 1.13(1.08, 1.18) | <0.001 |

| Model 1 (OR, 95% CI) | 1.13(1.05, 1.21) | 0.001 | 1.05(1.00, 1.10) | 0.045 |

| Model 2 (OR, 95% CI) | 1.09(1.00, 1.19) | 0.045 | 1.04(0.98, 1.09) | 0.184 |

| Model 3 (OR, 95% CI) | 1.05(0.95, 1.15) | 0.316 | 1.03(0.97, 1.09) | 0.28 |

Notes: Model 1: Age/Race/Gender; Model 2: Model 1 incorporates bmi/ smoking/drinking status/ education level; Model 3: Model 2 incorporates disease conditions (yes or no, including high blood pressure, diabetes and high cholesterol).

Abbreviations: OR, Odds Ratio; CI, Confidence Interval.

These results suggest that although SUA levels seemed to correlate with a heightened risk of malignant melanoma and non-melanoma skin cancers at first glance, this connection diminished and became statistically insignificant once confounding variables were considered. This underscores the necessity of factoring in additional potential influences when assessing the link between SUA and the risk of MM and NMSC.

Subgroup Analysis

In this study, a detailed subgroup analysis was conducted to explore the relationship between serum uric acid (SUA) levels and malignant melanoma (MM) and non-melanoma skin cancer (NMSC). Our analysis focused on three key factors—age, sex, and ethnicity—and evaluated their effects across three different regression models. The findings suggest that SUA levels may be a relevant risk factor for skin cancer, with significant subgroup differences observed based on age, sex, and ethnicity. In the context of MM, elevated SUA levels showed a notable positive correlation with melanoma risk among individuals aged 60 and older in both unadjusted and partially adjusted models (eg, unadjusted model: OR = 1.14, 95% CI = 1.06–1.24, P = 0.001). However, this link diminished and became statistically insignificant in the fully adjusted model (Model 3: OR = 1.06, 95% CI = 0.95–1.19, P = 0.306). For those under 60, SUA levels were significantly tied to melanoma risk in the partially adjusted model (Model 2: OR = 1.19, 95% CI = 1.01–1.39, P = 0.035), though this connection vanished in the fully adjusted model (Model 3: OR = 1.07, 95% CI = 0.89–1.29, P = 0.446). In males, SUA levels were significantly linked to melanoma risk in the unadjusted model (OR = 1.15, 95% CI = 1.05–1.27, P = 0.004), but this association faded in the fully adjusted model (Model 3: OR = 0.99, 95% CI = 0.87–1.13, P = 0.905). Conversely, in females, the relationship between SUA levels and melanoma risk held strong across all models (Model 3: OR = 1.17, 95% CI = 1.02–1.34, P = 0.027), indicating that high SUA levels might independently elevate melanoma risk in women. When examining ethnicity, SUA levels were significantly associated with melanoma risk in Mexican Americans (Model 3: OR = 1.41, 95% CI = 1.07–1.87, P = 0.015). For non-Hispanic Whites, the association was significant in the unadjusted model (OR = 1.16, 95% CI = 1.07–1.25, P < 0.001) but lost significance after full adjustment (Model 3: OR = 1.02, 95% CI = 0.92–1.13, P = 0.751). Among non-Hispanic Blacks, marginal significance was noted in the unadjusted and partially adjusted models (Model 2: OR = 1.27, 95% CI = 1.00–1.61, P = 0.049), but this link disappeared in the fully adjusted model. No significant associations were found for other ethnic groups. For non-melanoma skin cancer (NMSC), SUA levels showed no significant association across all models in individuals aged 60 and older (Model 3: OR = 1.02, 95% CI = 0.95–1.10, P = 0.511). Among those under 60, the unadjusted model revealed a significant association between SUA levels and NMSC risk (OR = 1.11, 95% CI = 1.03–1.21, P = 0.009), though this weakened in the fully adjusted model (Model 3: OR = 1.07, 95% CI = 0.96–1.19, P = 0.2). In sex-specific analyses, SUA levels were significantly tied to NMSC risk in males in the unadjusted model (OR = 1.10, 95% CI = 1.04–1.17, P = 0.002), but this association lost significance after full adjustment (Model 3: OR = 1.04, 95% CI = 0.96–1.13, P = 0.303). In females, no significant associations were observed. Among Mexican Americans, SUA levels showed marginal significance in the unadjusted and partially adjusted models (Model 1: OR = 1.22, 95% CI = 1.01–1.49, P = 0.041), but this did not hold in the fully adjusted model. For non-Hispanic Whites, SUA levels were significant in the unadjusted and partially adjusted models (eg, unadjusted model: OR = 1.13, 95% CI = 1.07–1.18, P < 0.001), but the association disappeared in the fully adjusted model (Model 3: OR = 1.04, 95% CI = 0.98–1.11, P = 0.176). No significant links were found for non-Hispanic Blacks or other ethnic groups. These findings suggest that SUA levels may play a role in melanoma development, particularly among women and Mexican Americans, as these associations remained robust after multivariable adjustments. However, the connection between SUA levels and NMSC risk was less pronounced and not statistically significant in fully adjusted models (Table 3).

Table 3.

Association Between SUA Levels and Skin Cancer in Different Groups

| Melanoma | Crude Model (OR, 95% CI) | P value | Model 1(OR, 95% CI) | P value | Model 2(OR, 95% CI) | P value | Model 3(OR, 95% CI) | P value |

| Age | ||||||||

| ≥60 years old | 1.14(1.06, 1.24) | 0.001 | 1.13(1.04, 1.23) | 0.003 | 1.08(0.97, 1.19) | 0.148 | 1.06(0.95, 1.19) | 0.306 |

| <60 years old | 1.12(0.98, 1.27) | 0.088 | 1.14(0.99, 1.30) | 0.066 | 1.19(1.01, 1.39) | 0.035 | 1.07(0.89, 1.29) | 0.446 |

| Gender | ||||||||

| Male | 1.15(1.05, 1.27) | 0.004 | 1.15(1.04, 1.27) | 0.005 | 1.03(0.92, 1.16) | 0.57 | 0.99(0.87, 1.13) | 0.905 |

| Female | 1.20(1.09, 1.33) | <0.001 | 1.12(1.01, 1.25) | 0.031 | 1.21(1.07, 1.37) | 0.003 | 1.17(1.02, 1.34) | 0.027 |

| Race | ||||||||

| Mexican American | 1.40(1.12, 1.75) | 0.003 | 1.41(1.12, 1.77) | 0.003 | 1.49(1.14, 1.93) | 0.003 | 1.41(1.07, 1.87) | 0.015 |

| Non-Hispanic White | 1.16(1.07, 1.25) | <0.001 | 1.09(1.01, 1.18) | 0.03 | 1.16(1.07, 1.25) | <0.001 | 1.02(0.92, 1.13) | 0.751 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 1.31(1.08, 1.58) | 0.005 | 1.29(1.05, 1.57) | 0.013 | 1.27(1.00, 1.61) | 0.049 | 1.23(0.95, 1.59) | 0.109 |

| Other race | 1.39(0.96, 2.00) | 0.08 | 1.55(1.05, 2.27) | 0.026 | 1.52(0.95, 2.43) | 0.078 | 1.18(0.63, 2.20) | 0.603 |

| Non-melanoma | Crude Model (OR, 95% CI) | P value | Model 1(OR, 95% CI) | P value | Model 2(OR, 95% CI) | P value | Model 3(OR, 95% CI) | P value |

| Age | ||||||||

| ≥60 years old | 1.05(1.00, 1.11) | 0.052 | 1.04(0.99, 1.10) | 0.143 | 1.02(0.96, 1.09) | 0.47 | 1.02(0.95, 1.10) | 0.511 |

| <60 years old | 1.11(1.03, 1.21) | 0.009 | 1.08(0.99, 1.18) | 0.093 | 1.10(0.99, 1.22) | 0.069 | 1.07(0.96, 1.19) | 0.2 |

| Gender | ||||||||

| Male | 1.10(1.04, 1.17) | 0.002 | 1.10(1.03, 1.17) | 0.002 | 1.04(0.96, 1.12) | 0.33 | 1.04(0.96, 1.13) | 0.303 |

| Female | 1.11(1.04, 1.19) | 0.002 | 1.00(0.93, 1.07) | 0.9 | 1.04(0.96, 1.13) | 0.305 | 1.03(0.94, 1.13) | 0.525 |

| Race | ||||||||

| Mexican American | 1.18(0.98, 1.43) | 0.083 | 1.22(1.01, 1.49) | 0.041 | 1.24(0.99, 1.56) | 0.063 | 1.08(0.85, 1.39) | 0.524 |

| Non-Hispanic White | 1.13(1.07, 1.18) | <0.001 | 1.05(1.00, 1.10) | 0.046 | 1.04(0.98, 1.11) | 0.16 | 1.04(0.98, 1.11) | 0.176 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 1.05(0.92, 1.20) | 0.453 | 1.06(0.92, 1.21) | 0.444 | 1.06(0.91, 1.24) | 0.468 | 0.99(0.84, 1.16) | 0.86 |

| Other race | 0.93(0.66, 1.32) | 0.692 | 0.86(0.60, 1.24) | 0.426 | 0.67(0.42, 1.07) | 0.09 | 0.72(0.42, 1.22) | 0.221 |

Notes: Model 1: Age/Race/Gender; Model 2: Model 1 incorporates bmi/ smoking/drinking status/ education level; Model 3: Model 2 incorporates disease conditions (yes or no, including high blood pressure, diabetes and high cholesterol).

Abbreviations: OR, Odds Ratio; CI, Confidence Interval.

In summary, our results reveal a illuminate a complex relationship between SUA levels and the risks of MM and NMSC, emphasizing the importance of targeted subgroup analysis in different populations. These findings provide new insights into the potential role of SUA in skin cancer development and offer a basis for preventive strategies in specific populations. However, as the relationship between SUA levels and outcomes may be influenced by multiple factors, future studies with larger sample sizes and diverse populations are needed to validate and expand upon these findings.

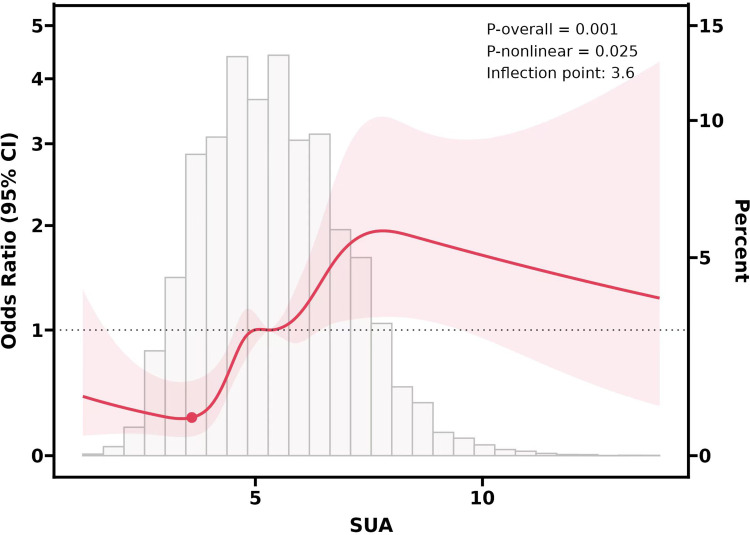

Nonlinear Relation of SUA Level with MM and NMSC

A restricted cubic spline (RCS) analysis evaluated the nonlinear relationship between serum uric acid (SUA) levels and malignant melanoma (MM) and non-melanoma skin cancer (NMSC) risks. Figures 2–4 depict these associations, with shaded areas representing 95% confidence intervals. NHANES data divulged a significant nonlinear link between SUA levels and MM risk (P < 0.001; P-nonlinear = 0.025), with a threshold at 5.9 mg/dL beyond which MM risk increased. For NMSC, SUA levels between 3.6 and 7.7 mg/dL correlated with higher risk, peaking at 7.7 mg/dL before declining. Both P values (P = 0.001; P-nonlinear = 0.025) confirmed the reliability of these nonlinear trends.

Figure 2.

Association between SUA and MM with the RCS function.

Notes: A restricted cubic spline (RCS) function was used to examine the nonlinear relationship between serum uric acid (SUA) levels and malignant melanoma (MM) risk. Results indicated that MM risk significantly increases when SUA exceeds 5.9 mg/dL.

Figure 3.

Association between SUA and NMSC with the RCS function.

Notes: To examine the link between serum uric acid (SUA) levels and the likelihood of developing non-melanoma skin cancer (NMSC), a restricted cubic spline (RCS) function was employed to explore potential nonlinear patterns. The findings revealed a notable uptick in NMSC risk once SUA levels surpassed the 3.6 mg/dL mark, highlighting a critical threshold in the relationship.

Figure 4.

The association between SUA levels after the inflection point and RCS curve for NMSC.

Notes: A restricted cubic spline function was used to investigate the link between serum uric acid (SUA) levels and non-melanoma skin cancer (NMSC) risk. Results indicated that when SUA exceeded 7.7 mg/dL, the risk of NMSC decreased with higher SUA concentrations.

MR Analysis of the Effect of SUA Level on Outcomes

First, we selected single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) that were significantly associated with the exposure data (P < 5 × 10⁻8, F-statistic > 10) and independent (r² < 0.001, physical window = 10,000 kb). Subsequently, the exposure data and outcome data were aligned, and 239 SNPs for MM and 237 SNPs for NMSC were chosen as instrumental variables for Genetic causal inference.

The inverse variance weighted (IVW) method with random effects was employed in this study, and the results showed no genetic association between serum uric acid (SUA) levels and the two types of cancer (P = 0.577; P = 0.214) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Five Mendelian Randomization Analysis Methods for Estimating the Causal Relationship Between SUA Level and Outcomes

| Exposure | Outcome | Method | SNP(n) | OR(95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SUA level | Malignant melanoma | IVW | 239 | 0.961 (0.837–1.104) | 0.577 |

| SUA level | Malignant melanoma | MR Egger | 239 | 0.833 (0.635–1.095) | 0.193 |

| SUA level | Malignant melanoma | Simple mode | 239 | 0.789 (0.459–1.355) | 0.392 |

| SUA level | Malignant melanoma | Weighted mode | 239 | 0.824 (0.628–1.081) | 0.164 |

| SUA level | Malignant melanoma | Weighted median | 239 | 0.894 (0.715–1.118) | 0.327 |

| SUA level | Non-malignant melanoma | IVW | 237 | 1.055 (0.970–1.147) | 0.214 |

| SUA level | Non-malignant melanoma | MR Egger | 237 | 1.032 (0.874–1.219) | 0.712 |

| SUA level | Non-malignant melanoma | Simple mode | 237 | 1.018 (0.794–1.307) | 0.886 |

| SUA level | Non-malignant melanoma | Weighted mode | 237 | 1.002 (0.880–1.140) | 0.976 |

| SUA level | Non-malignant melanoma | Weighted median | 237 | 0.997 (0.889–1.119) | 0.963 |

Abbreviations: OR, Odds Ratio; CI, Confidence Interval; SUA, Serum uric acid; IVW, Inverse variance weighting.

Other Analysis

Studies show that SNPs analyzed for skin cancer are evenly distributed across the funnel plot, indicating low heterogeneity (Figure S1). Cochran’s Q test confirmed this for most SNPs in MR analysis, except those linked to melanoma (p > 0.05). Although melanoma-associated SNPs showed heterogeneity (p < 0.05), it did not invalidate IVW-derived conclusions, ensuring MR findings for melanoma remain robust. Scatter plots declared minimal SNP influence on SUA levels or skin cancers, suggesting no significant pleiotropic effects (Figure S2). Egger regression further supported this, with no statistically significant pleiotropy detected (p-values > 0.05), confirming SNP effects were not confounded (Supplementary Table 1). The leave-one-out sensitivity analysis indicates that the observed association remains relatively robust to the choice of instrumental variables. Excluding individual SNPs does not substantially alter the overall estimation of the causal effect (Figure S3). Forest plot analysis evinced no significant causal relationship between SUA levels and either malignant melanoma or non-melanoma skin cancer (Figure S4). The inverse analysis also did not find a link between SUA levels and results. (Supplementary Table 2 and Figures S5–S8).

Discussion

Skin cancer, one of the most prevalent malignant tumors globally, encompasses two primary types: malignant melanoma (MM) and non-melanoma skin cancer (NMSC).23,24 Although the pathogenic mechanisms underlying both MM and NMSC have been extensively studied, their associated risk factors remain inadequately understood. Besides, the relationship between serum uric acid (SUA) levels, proposed as a potential biomarker, and the risk of MM and NMSC remains elusive. A large cohort study conducted in the Stockholm region reported11 a significant correlation between serum uric acid (SUA) levels and the risk of NMSC in men; however, no such relationship was found between SUA levels and MM in either men or women. This discrepancy could be attributed to study design, sample populations, and the influence of confounding factors.

In terms of this study, it leveraged the NHANES database and genetic instrumental variable analysis to investigate whether SUA levels relate to the risk of disease onset. By means of examining diverse populations and adjusting for confounding factors, the study aimed to clarify the role of SUA across various groups and evaluate its viability as a risk biomarker.

Above all, a retrospective analysis of the extensive NHANES dataset demonstrated that high SUA levels were associated with an array of adverse health factors such as higher BMI, smoking status, alcohol consumption, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, and diabetes. Among women, increased SUA levels were correlated with a heightened risk of MM, whereas both men and women exhibited a positive correlation between higher SUA levels and an increased risk of NMSC. The bond between SUA levels and the risk of MM and NMSC followed a nonlinear trajectory. Our analysis revealed a notable spike in the risk of MM when serum uric acid (SUA) levels exceeded 5.9 mg/dL. As for NMSC, the risk progressively intensified within the SUA range of 3.6–7.7 mg/dL, peaking at 7.7 mg/dL before tapering off. Based on our study findings, serum uric acid levels exceeding 7.7 mg/dL appear to confer a protective effect against non-melanoma skin cancer (NMSC). While the specific underlying mechanisms remain to be fully elucidated, the antioxidant properties of uric acid are likely pivotal in this relationship. As an endogenous antioxidant,25 uric acid can effectively scavenge free radicals through the hydrogen atom transfer mechanism, exerting an antioxidant effect.26 Previous research27,28 has demonstrated that elevated serum uric acid levels are associated with reduced mortality and prolonged survival in patients with malignant tumors. Moreover, evolutionary enhancements in the antioxidant defense system of organisms may be crucial in diminishing cancer risk, with high serum uric acid concentration a key protective factor.29 Beyond that, it is hypothesized that when uric acid levels exceed 7.7 mg/dL, a compensatory biological pathway may be activated, thus contributing to anticancer effects. From a molecular perspective, uric acid—produced via xanthine oxidoreductase (XOR) metabolism—exerts antioxidant effects that can modulate tumor cell proliferation and metastasis.30 The downregulation of XOR may result in heightened immune evasion and oxidative stress within the tumor microenvironment, thereby facilitating cancer progression. As an additional point, the regulatory role of uric acid may involve alterations in fructose metabolism, activation of the AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) signaling pathway, modulation of inflammatory responses, and engagement of mTOR/AKT signaling pathways, all of which collectively instrumental in the suppression of tumor initiation and progression.31 These findings suggest that SUA levels may not function as independent risk factors for MM or NMSC, as their associations with these diseases appear to be influenced by multiple confounding factors. Interestingly, subgroup analyses yielded the following key insights: Among women, the association between SUA levels and melanoma remained statistically even after adjusting for multiple confounders, implying that SUA may act as an independent risk factor for melanoma in women. A similar significant association was observed in Mexican Americans. Nevertheless, in other populations and for NMSC, the associations between SUA levels and outcomes diminished or disappeared following adjustment for confounders, indicating that SUA may not be an independent risk factor for these groups or for NMSC. When comparing genders, men demonstrated a more pronounced correlation between SUA levels and NMSC. In addition to that, for individuals aged 60 years and older, the association between SUA levels and skin cancer risk was particularly marked, whereas NMSC was more commonly observed in those under 60 years of age.

Although no definitive causal evidence was established between the two, previous studies have suggested potential inconsistencies between observational research and causal inference findings. For instance, while observational studies indicate an association between atopic dermatitis and the risk of skin cancer, MR analysis failed to validate a causal relationship.32 Similarly, a cohort study identified a nonlinear relationship between sleep duration and cognitive function, but genetic causal inference was unable to confirm this connection.33

The connection between high uric acid levels and cancer has been extensively studied and firmly established. Research employing a Mendelian Randomization (MR) approach has investigated the potential causal relationship between serum uric acid (SUA) levels and both cancer risk and mortality.10 The findings reveal that elevated SUA levels are linked, both observationally and genetically, to an increased cancer incidence and overall mortality. This suggests that lowering SUA levels could represent a promising strategy for cancer prevention and for strengthening risk assessment models. On top of that, hyperuricemia not only exacerbates mortality rates and worsens outcomes in cancer patients but may also undermine the effectiveness of cancer treatments.34 Specifically, in the context of skin cancer, studies have displayed that high SUA levels in hyperuricemic mice hinder the effectiveness of immunotherapy in curb melanoma progression. Long-term follow-up studies further unveil that individuals with gout, a condition characterized by elevated uric acid, experience a significantly higher incidence of skin cancer compared to the general population.12

Evidence from the literature indicates that elevated serum uric acid (SUA) levels influence the initiation and progression of skin cancer through mechanism, such as chronic inflammation, oxidative stress, metabolic dysregulation, and the disruptions in signaling pathways.35,36 Chronic hyperuricemia may exacerbate persistent inflammation, resulting in increased DNA damage in skin cells and ultimately facilitating carcinogenesis, which gives demonstration to that the short-term antioxidant effects of uric acid may be overshadowed by its long-term pro-inflammatory effects. A detailed mechanistic pathway underlies the effects of hyperuricemia on the skin tumor microenvironment. When hyperuricemia occurs,37 monosodium urate (MSU) crystals precipitate in bodily fluids and are subsequently phagocytosed by neutrophils and macrophages, which in turn triggers the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome. This activation catalyzes the cleavage of pro–IL-1β into its active form, IL-1β, thereby initiating a cascading inflammatory response.38 At elevated concentrations, soluble uric acid further intensifies the secretion of IL-1β and other proinflammatory mediators via the TLR4/MyD88 signaling pathway, while simultaneously downregulating the expression of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-1Ra.39,40 What’s more, uric acid modulates cellular transcription programs by upregulating inflammatory genes such as IL-1β and NLRP3, establishing a sustained low-grade systemic inflammatory milieu.41 This chronic inflammation, driven by serum uric acid (SUA), remodels the tumor microenvironment and fosters conditions conducive to tumor cell growth and invasion.34 Furthermore, IL-1β, along with other inflammatory mediators, not only directly accelerate the proliferation of keratinocytes and melanocytes42 but also induce the secretion of additional factors that promote cellular survival and angiogenesis through the activation of NF-κB and related signaling pathways, thereby driving both the initiation and progression of skin cancer.43 Hyperuricemia may also disrupt the normal functioning of the immune system, weakening immune surveillance and thereby increasing the risk of malignant transformation in skin cells, which brings an increase to the likelihood of skin cancer development. A single-center, multi-omics study demonstrated that uric acid contributes to the formation of an immune-suppressive tumor microenvironment by promoting chronic inflammatory responses, inhibiting T cell infiltration, and downregulating the expression of immune checkpoint and HLA molecules. These effects, in turn, influence cancer progression and the response to immunotherapy.44 The chronic inflammatory response induced by uric acid facilitates tumor cell proliferation and invasion by activating cytokines, chemokines, and other mediators, creating favorable conditions for the development of both malignant melanoma and non-melanoma skin cancers. However, some studies have presented alternative viewpoints.45 Serum uric acid (SUA) mitigates oxidative stress by means of scavenging reactive oxygen species (ROS), thereby protecting melanocytes from ROS-induced DNA damage. Uric acid derivatives, such as 1-methyluric acid and 1,7-dimethyluric acid, exhibit principal antioxidative and photoprotective properties, effectively reducing UV-induced oxidative damage and lowering the risk of melanoma development. In a similar vein, the onset of NMSC is often frequently correlated with ultraviolet (UV) exposure. UV-induced oxidative stress emerges as a major pathogenic factor, and uric acid, owing to its antioxidative capacity, ameliorates UV-induced cellular damage, indirectly attenuating the incidence of NMSC. Therefore, the relationship between serum uric acid (SUA) and skin cancer is not only complex but also bidirectional. Recent epidemiological studies suggest that the relationship between serum uric acid (SUA) and cancer risk is better characterized by a U-shaped curve rather than a simplistic linear association, with both excessively low and high SUA levels being implicated in heightened cancer incidence and mortality.46,47 A comprehensive analysis denotes that critical inflection points for man and women are approximately 6 mg/dL and 4 mg/dL respectively, with an elevated cancer risk occurring when SUA levels fall below or exceed these thresholds.48 These findings underscore the dose-dependent nature of uric acid’s influence on tumorigenesis:49 within an optimal range, uric acid’s antioxidant properties predominate, conferring potential protective benefits, whereas concentrations beyond this range shift its effects toward pro-inflammatory and pro-oxidative processes that promote carcinogenesis.50 Modern lifestyles marked by prolonged high-purine diets and metabolic dysregulation can lead to chronic hyperuricemia, providing sufficient time for the development of pathogenic processes—including pro-inflammatory responses, oxidative stress, and immune dysregulation. These processes may diminish the short-term antioxidant protection afforded by uric acid and, in turn, increase the risk of malignancies.51 Apart from that, gender appears to be a significant modifier, as notable gender-based differences in the association between SUA levels and skin cancer risk suggest that sex hormones or sex-specific metabolic variations may modulate uric acid’s biological effects.11 In summary, the influence of SUA on tumorigenesis is multidimensional and context-dependent: only under specific combinations of concentration thresholds, duration, and host environmental factors do the tumor-promoting effects of uric acid outweigh its antioxidant benefits. Consequently, when evaluating the role of uric acid in the risk of skin cancer, it is imperative to account for such variables dose, duration, and individual patient’s physiological background to holistically elucidate this dual-effect mechanism. Hyperuricemia may increase the risk of MM and NMSC through multitude of mechanisms, including chronic inflammation, immune dysregulation, and cumulative DNA damage. The role of uric acid in skin cancer may vary depending on its antioxidative and immune-modulating effects on tumor development.

One of the standouts features of this research lies in its innovative integration of Mendelian Randomization alongside cross-sectional data to dip into the potential link between serum uric acid (SUA) levels and both malignant melanoma and non-melanoma skin cancers. The results consistently demonstrate a positive correlation between elevated SUA levels and an increased risk of these skin cancers across diverse populations, genders, and ethnicities, as a way to solidify SUA as a noteworthy risk factor. This approach effectively addresses critical gaps left by earlier studies. Observational studies are often more vulnerable to confounding factors and reverse causation, which can introduce uncertainty into the observed associations between exposures and outcomes. In contrast, Mendelian Randomization (MR) exploits inherent genetic variations that are randomly assigned at fertilization, thereby approximating an individual’s “lifetime exposure” from birth. By integrating MR into the research framework, cross-sectional observational studies can be refined to complement and strengthen causal inference, while also mitigating potential biases and reducing unnecessary sample attrition seen in traditional observational research.52 Furthermore, leveraging the NHANES database—a resource renowned for its standardized, comprehensive, and large-scale data collection—bolsters the study’s statistical robustness, generalizability, and overall reliability. By utilizing multivariable regression models, the research meticulously accounted for a variety of potential confounding variables, including age, gender, ethnicity, education, comorbidities, smoking habits, and alcohol consumption. This methodological rigor not only minimizes bias but also enhances the accuracy and credibility of the findings.

The case information available in the NHANES database is confined to US adults, which raises concerns regarding the extrapolation of its findings to other global populations. Although the study meticulously controlled for a wide array of variables, it did not fully account for factors such as environmental influences, ultraviolet exposure, and genetic susceptibility. Moreover, NHANES provides only a single measurement of serum uric acid,53 constraining our ability to accurately assess average levels over long-term follow-up. While the Mendelian randomization (MR) method reflects lifetime cumulative effects, its exposure time window does not align with that of the observational analyses, thereby introducing potential temporal bias. Future research should use longitudinal or repeated data to better reflect lifelong genetic exposure, minimizing time-window discrepancies in study design. Additionally, cancer‐related outcomes were solely based on participants’ self‐reports, which may introduce recall bias and compromise the accuracy of our results. Furthermore, the outcome samples were derived exclusively from a Finnish population, thereby restricting the generalizability of our findings and potentially introducing selection bias. Finally, reliance on publicly available GWAS data hinders the effective control of individual-level confounding, leaving room for residual confounding. With all these considered, future research should prioritize expanding sample diversity, gathering more granular phenotypic data, and incorporating methods including multivariate Mendelian randomization (MR) to enhance the robustness and generalizability of the research findings.

Conclusion

Elevated serum uric acid (SUA) levels are linked to increased risks of malignant melanoma (MM) and non-melanoma skin cancer (NMSC), mediated by systemic inflammation, oxidative stress, and immune suppression, all of which facilitate tumor growth. SUA levels above a critical threshold heighten the risk of MM, particularly among females and Mexican Americans, while the risk of NMSC declines post-threshold. Aged individuals (≥60 years) show stronger MM-SUA correlations, whereas NMSC is more prevalent in younger populations (<60 years). Lifestyle and comorbidities may act as confounders in the relationship between SUA and skin cancer. Genetic analyses suggest that SUA acts as a non-causal risk marker rather than a direct etiological factor. Future studies should lay focus on addressing confounders, refining genetic tools, and integrating basic and prospective research to clarify SUA’s complex, bidirectional role in skin cancer pathogenesis.

Acknowledgments

We would like to extend our heartfelt appreciation to the National Center for Health Statistics at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) for making the data available for public access. We sincerely thank the Macau University of Science and Technology for their generous funding support.

Funding Statement

This work was funded by The Science and Technology Development Fund, Macau SAR (File no. 006/2023/SKL).

Abbreviations

MM, Malignant melanoma; NMSC, Non-melanoma skin cancer; SUA, Serum uric acid; NHANES, National health and nutrition examination survey; MR, Mendelian randomization; BCC, basal cell carcinoma; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma; IVW, Inverse variance weighting; WM, weighted median; RCS, restricted cubic spline.

Ethical Clearance and Participant Consent

Since this study utilizes publicly available anonymous data, it complies with Article 32, Paragraphs 1 and 2 of the “Measures for Ethical Review of Life Science and Medical Research Involving Human Subjects”, issued by China’s National Health Commission and the State Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine in February 2023. According to these guidelines, research involving human data or biological samples may be exempt from ethical review if it poses no risk, omits sensitive personal information, and has no commercial interest. Furthermore, all human data used in this study were approved by the Ethics Review Board of the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS).

Disclosure

Peiyu Yan and Jiyou Kou are co-corresponding authors with equal contributions. No conflicts of interest are declared by the authors.

References

- 1.Khayyati Kohnehshahri M, Sarkesh A, Mohamed Khosroshahi L, et al. Current status of skin cancers with a focus on immunology and immunotherapy. Cancer Cell Int. 2023;23(1):174. doi: 10.1186/s12935-023-03012-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nakayama K. Growth and progression of melanoma and non-melanoma skin cancers regulated by ubiquitination. Pigm Cell Melanoma Res. 2010;23(3):338–351. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-148X.2010.00692.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bowden GT. Prevention of non-melanoma skin cancer by targeting ultraviolet-B-light signalling. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4(1):23–35. doi: 10.1038/nrc1253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang M, Gao X, Zhang L. Recent global patterns in skin cancer incidence, mortality, and prevalence. Chin Med J. 2024;138(2):185–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lan W, Zhuang W, Wang R, et al. Advanced lung cancer inflammation index is associated with prognosis in skin cancer patients: a retrospective cohort study. Front Oncol. 2024;14:1365702. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2024.1365702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Apalla Z, Nashan D, Weller RB, Castellsagué X. Skin cancer: epidemiology, disease burden, pathophysiology, diagnosis, and therapeutic approaches. Dermatol Ther. 2017;7(Suppl 1):5–19. doi: 10.1007/s13555-016-0165-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Agtas G, Alkan A, Tanriverdi Ö. Serum uric acid level can predict asymptomatic brain metastasis at diagnosis in patients with small cell lung cancer. J Egypt Natl Canc Inst. 2024;36(1):28. doi: 10.1186/s43046-024-00235-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yan S, Zhang P, Xu W, et al. Serum uric acid increases risk of cancer incidence and mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mediators Inflamm. 2015;2015(1):764250. doi: 10.1155/2015/764250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Allegrini S, Garcia-Gil M, Pesi R, Camici M, Tozzi MG. The good, the bad and the new about uric acid in cancer. Cancers. 2022;14(19):4959. doi: 10.3390/cancers14194959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kobylecki CJ, Afzal S, Nordestgaard BG. Plasma urate, cancer incidence, and all-cause mortality: a Mendelian randomization study. Clin Chem. 2017;63(6):1151–1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yiu A, Van Hemelrijck M, Garmo H, et al. Circulating uric acid levels and subsequent development of cancer in 493,281 individuals: findings from the AMORIS Study. Oncotarget. 2017;8(26):42332–42342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boffetta P, Nordenvall C, Nyrén O, Ye W. A prospective study of gout and cancer. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2009;18(2):127–132. doi: 10.1097/CEJ.0b013e328313631a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen Y, Zhang S, Wu J, et al. Exploring the link between serum uric acid and colorectal cancer: insights from genetic evidence and observational data. Medicine. 2024;103(47):e40591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang S, Zhang Z, Su Y, et al. Association between serum urate levels, gout and breast cancer: observational and Mendelian randomization analyses. Transl Cancer Res. 2025;14(1):473–485. doi: 10.21037/tcr-24-1141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sakaue S, Kanai M, Tanigawa Y, et al. A cross-population atlas of genetic associations for 220 human phenotypes. Nat Genet. 2021;53(10):1415–1424. doi: 10.1038/s41588-021-00931-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li J, Wang J, Yang M, Wang G, Xu P. The relationship between major depression and delirium: a two-sample Mendelian randomization analysis. J Affect Disord. 2023;338:69–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2023.05.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Odden MC, Amadu AR, Smit E, Lo L, Peralta CA. Uric acid levels, kidney function, and cardiovascular mortality in US adults: national health and nutrition examination survey (NHANES) 1988-1994 and 1999-2002. Am J Kidney Dis. 2014;64(4):550–557. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2014.04.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shimazu T, Inoue M, Sasazuki S, et al. Isoflavone intake and risk of lung cancer: a prospective cohort study in Japan. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91(3):722–728. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.28161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lin L, Hu Y, Lei F, et al. Cardiovascular health and cancer mortality: evidence from US NHANES and UK Biobank cohort studies. BMC Med. 2024;22(1):368. doi: 10.1186/s12916-024-03553-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yin J, Wang H, Li S, et al. Nonlinear relationship between sleep midpoint and depression symptoms: a cross-sectional study of US adults. BMC Psychiatry. 2023;23(1):671. doi: 10.1186/s12888-023-05130-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marrie RA, Dawson NV, Garland A. Quantile regression and restricted cubic splines are useful for exploring relationships between continuous variables. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(5):511–517.e511. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.05.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen Y, Guan M, Wang R, Wang X. Relationship between advanced lung cancer inflammation index and long-term all-cause, cardiovascular, and cancer mortality among type 2 diabetes mellitus patients: NHANES, 1999-2018. Front Endocrinol. 2023;14:1298345. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2023.1298345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhao H, Wu J, Wu Q, Shu P. Systemic immune-inflammation index values are associated with non-melanoma skin cancers: evidence from the national health and nutrition examination survey 2010-2018. Arch Med Sci. 2024;20(4):1128–1137. doi: 10.5114/aoms/177345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gordon R. Skin cancer: an overview of epidemiology and risk factors. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2013;29(3):160–169. doi: 10.1016/j.soncn.2013.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schlotte V, Sevanian A, Hochstein P, Weithmann KU. Effect of uric acid and chemical analogues on oxidation of human low density lipoprotein in vitro. Free Radic Biol Med. 1998;25(7):839–847. doi: 10.1016/S0891-5849(98)00160-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith RC, Reeves J, McKee ML, Daron H. Reaction of methylated urates with 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl. Free Radic Biol Med. 1987;3(4):251–257. doi: 10.1016/S0891-5849(87)80032-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Taghizadeh N, Vonk JM, Boezen HM. Serum uric acid levels and cancer mortality risk among males in a large general population-based cohort study. Cancer Causes Control. 2014;25(8):1075–1080. doi: 10.1007/s10552-014-0408-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dziaman T, Banaszkiewicz Z, Roszkowski K, et al. 8-Oxo-7,8-dihydroguanine and uric acid as efficient predictors of survival in colon cancer patients. Int J Cancer. 2014;134(2):376–383. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ames BN, Cathcart R, Schwiers E, Hochstein P. Uric acid provides an antioxidant defense in humans against oxidant- and radical-caused aging and cancer: a hypothesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1981;78(11):6858–6862. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.11.6858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Linder N, Martelin E, Lundin M, et al. Xanthine oxidoreductase - clinical significance in colorectal cancer and in vitro expression of the protein in human colon cancer cells. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45(4):648–655. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yan W, Xiang P, Liu D, Zheng Y, Ping H. Association between the serum uric acid levels and prostate cancer: evidence from national health and nutrition examination survey (NHANES) 1999-2010. Transl Cancer Res. 2024;13(5):2308–2314. doi: 10.21037/tcr-24-46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Luo M, Zheng Y, Zhuo Q, Lin L, Han Y. The causal effects of atopic dermatitis on the risk of skin cancers: a two-sample Mendelian randomization study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2024;38(4):703–709. doi: 10.1111/jdv.19674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Qiu P, Dong C, Li A, Xie J, Wu J. Exploring the relationship of sleep duration on cognitive function among the elderly: a combined NHANES 2011-2014 and mendelian randomization analysis. BMC Geriatr. 2024;24(1):935. doi: 10.1186/s12877-024-05511-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mi S, Gong L, Sui Z. Friend or Foe? An unrecognized role of uric acid in cancer development and the potential anticancer effects of uric acid-lowering drugs. J Cancer. 2020;11(17):5236–5244. doi: 10.7150/jca.46200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zambrano-Román M, Padilla-Gutiérrez JR, Valle Y, Muñoz-Valle JF, Valdés-Alvarado E. Non-melanoma skin cancer: a genetic update and future perspectives. Cancers. 2022;14(10):2371. doi: 10.3390/cancers14102371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Emanuelli M, Sartini D, Molinelli E, et al. The double-edged sword of oxidative stress in skin damage and melanoma: from physiopathology to therapeutical approaches. Antioxidants. 2022;11(4):612. doi: 10.3390/antiox11040612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rock KL, Kataoka H, Lai JJ. Uric acid as a danger signal in gout and its comorbidities. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2013;9(1):13–23. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2012.143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shi Y, Mucsi AD, Ng G. Monosodium urate crystals in inflammation and immunity. Immunol Rev. 2010;233(1):203–217. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2009.00851.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Crișan TO, Cleophas MC, Oosting M, et al. Soluble uric acid primes TLR-induced proinflammatory cytokine production by human primary cells via inhibition of IL-1Ra. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75(4):755–762. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-206564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Braga TT, Forni MF, Correa-Costa M, et al. Soluble uric acid activates the NLRP3 inflammasome. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):39884. doi: 10.1038/srep39884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cabău G, Crișan TO, Klück V, Popp RA, Joosten LAB. Urate-induced immune programming: consequences for gouty arthritis and hyperuricemia. Immunol Rev. 2020;294(1):92–105. doi: 10.1111/imr.12833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cheong KA, Kil IS, Ko HW, Lee AY. Upregulated guanine deaminase is involved in hyperpigmentation of seborrheic keratosis via uric acid release. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(22):12501. doi: 10.3390/ijms222212501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Snezhkina AV, Kudryavtseva AV, Kardymon OL, et al. ROS generation and antioxidant defense systems in normal and malignant cells. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2019;2019:6175804. doi: 10.1155/2019/6175804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen H, Shi D, Guo C, et al. Can uric acid affect the immune microenvironment in bladder cancer? A single-center multi-omics study. Mol Carcinog. 2024;63(3):461–478. doi: 10.1002/mc.23664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fini MA, Elias A, Johnson RJ, Wright RM. Contribution of uric acid to cancer risk, recurrence, and mortality. Clin Transl Med. 2012;1(1):16. doi: 10.1186/2001-1326-1-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Crawley WT, Jungels CG, Stenmark KR, Fini MA. U-shaped association of uric acid to overall-cause mortality and its impact on clinical management of hyperuricemia. Redox Biol. 2022;51:102271. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2022.102271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cho SK, Chang Y, Kim I, Ryu S. U-shaped association between serum uric acid level and risk of mortality: a cohort study. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018;70(7):1122–1132. doi: 10.1002/art.40472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hu L, Hu G, Xu BP, et al. U-shaped association of serum uric acid with all-cause and cause-specific mortality in us adults: a cohort study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2020;105(1):e597–e609. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgz068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Suzuki T, Ozawa-Tamura A, Takeuchi M, Sasabe Y. Uric Acid as a photosensitizer in the reaction of deoxyribonucleosides with UV light of wavelength longer than 300 nm: identification of products from 2’-deoxycytidine. Chem Pharm Bull. 2021;69(11):1067–1074. doi: 10.1248/cpb.c21-00501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Huang CF, Huang JJ, Mi NN, et al. Associations between serum uric acid and hepatobiliary-pancreatic cancer: a cohort study. World J Gastroenterol. 2020;26(44):7061–7075. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v26.i44.7061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fini MA, Lanaspa MA, Gaucher EA, et al. Brief report: the uricase mutation in humans increases our risk for cancer growth. Cancer Metab. 2021;9(1):32. doi: 10.1186/s40170-021-00268-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gill D, Karhunen V, Malik R, Dichgans M, Sofat N. Cardiometabolic traits mediating the effect of education on osteoarthritis risk: a Mendelian randomization study. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2021;29(3):365–371. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2020.12.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Li B, Chen L, Hu X, et al. Association of serum uric acid with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2023;46(2):425–433. doi: 10.2337/dc22-1339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]