Abstract

Background:

Interstitial lung disease (ILD) is the leading cause of death in patients with systemic sclerosis (SSc), affecting more than 40% of this population. Despite the availability of effective treatments to stabilize or improve lung function, survival for patients with SSc-ILD remains poor. Poor outcomes have been attributed to delayed diagnosis and initiation of treatment for SSc-ILD. Although recent guidelines have provided conditional recommendations for early screening, pulmonary function tests (PFTs) are insensitive for early diagnosis, and computed tomography (CT)—the current gold standard—often detects disease after irreversible lung injury has occurred. A single sensitive biomarker that can accurately predict the risk of SSc-ILD development and mortality is lacking. We hypothesized that applying machine learning (ML) methods to multiple features from readily available electronic health records (EHR) could construct a model to detect ILD and predict mortality in patients with SSc.

Methods:

We retrospectively analyzed EHR data from participants enrolled in a single-center registry of patients with SSc over a period of twenty-eight years (1995–2024). We applied a combination of ML models to seventy-four clinical features encompassing demographics, clinical history, PFTs, and laboratory results. The resultant models were tasked with detecting ILD and predicting mortality in participants with SSc.

Results:

1,169 participants with SSc were included in this study, spanning 15,494 person-years of observation. Models detecting ILD achieved an AUC of 0.818 and confirmed the importance of known biomarkers, such as autoantibodies and PFTs, as risk factors for SSc-ILD. Unexpected clinical values including white blood cell count and mean corpuscular volume were also important for model prediction of SSc-ILD. For prediction of one-year all-cause mortality, models reached an AUC of 0.903. In a subgroup analysis of those with prevalenet radiographic SSc-ILD, three-year all-cause mortality prediction reached an AUC of 0.831. These models identified features strongly associated with mortality that are routinely collected during clinical assessment of patients with SSc, including unexpected associations with values such as red cell distribution width and serum chloride concentration.

Conclusions:

ML-based analysis of clinical features and laboratory tests collected as part of routine clinical care detect ILD and predict mortality in patients with SSc.

INTRODUCTION

Systemic sclerosis (SSc) is a rare autoimmune disease that predominantly affects middle-aged adults and is characterized by progressive multi-organ fibrosis.1,2 Interstitial lung disease (ILD) is the most common pulmonary manifestation of SSc and the leading cause of death.3,4 Estimates of the prevalence of SSc-ILD range from 40–60%.5–8 Most patients with SSc-ILD will present with ILD at the time of SSc diagnosis;9–11 however, a significant number will develop ILD in later disease stages.12 Furthermore, the clinical course of SSc-ILD is highly heterogeneous.13,14 Most patients experience a gradual decline in lung function that stabilizes over time while some exhibit rapid deterioration, resulting in respiratory failure and early mortality.14 Clinical tools to effectively risk stratify patients with SSc-ILD are needed to guide post-screening follow-up and optimize the use and timing of effective treatments.15

Pulmonary function tests (PFTs) and computed tomography (CT) scans of the chest are used to diagnosis and monitor the progression of SSc-ILD; however, these typically detect disease only after significant, often irreversible, lung injury has occurred.16 For example, early in the course of SSc-ILD, forced vital capacity (FVC) and diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide (DLCO) measurements may decline but still be in the normal range.17 Furthermore, fine crackles on chest examination—a sensitive marker of ILD18—can be detected in those who have baseline normal CT scans who later develop SSc-ILD.19 Delays in diagnosis facilitated by insensitive clinical screening tools and variation in practice are particularly problematic given the importance of early treatment in modifying disease course.13,20 While antifibrotic and myelosuppressive therapies are available and effective,21–23 initiation is often guided by clinical gestalt rather than objective indicators,20 potentially leading to suboptimal timing of treatment. As a result, mortality in SSc-ILD has remained largely unchanged,24 suggesting the need for a more streamlined, data-driven approach to disease management. Clinical tools that allow for early recognition of patients at risk for progressive ILD or adverse clinical outcomes, particularly mortality, have promise to change the management paradigm for patients with SSc-ILD.

Deep learning applied to CT imaging can classify ILD subtypes, detect abnormal interstitial patterns, and assess the extent of fibrotic disease.25–28 These models, however, do not leverage readily available longitudinal information in the electronic health record (EHR). In a recent study, machine learning (ML) methods that applied clinical data predicted ILD progression in patients with SSc, but the model only incorporated features previously associated with ILD progression.29 In this study, we developed ML models that utilize multiple EHR features routinely collected in clinical practice of the care of SSc patients as input, irrespective of known associations with SSc-ILD. Our predictive models distinguish patients who may benefit from closer monitoring, additional evaluation, or initiation/discontinuation of therapy. The model was informed by both known and unexpected associations with SSc-ILD progression. Our findings suggest that these models might be useful in developing individualized monitoring and treatment plans for patients with SSc and identifying new biomarkers or pathways associated with SSc-ILD pathogenesis.

METHODS

Human Participants, Data Collection, and Label Generation for Models

All human participant research was approved by the Northwestern University Institutional Review Board. All participants provided informed consent and were enrolled in study STU00002669—the Northwestern Scleroderma Registry—from 1995 through 2024. Data for patients enrolled in the study were extracted from the Northwestern Electronic Data Warehouse, which is a continuously updated and searchable repository of EHR data.30 Additional data were collected by study-associated research coordinators or physicians during patient encounters or extracted through patient chart review and captured in a study-specific REDCap database. To be included in the Registry, participants had to meet either the 1980 American College of Rheumatology (ACR) or the 2013 ACR/European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology criteria for SSc, depending on date of enrollment.31,32 Disease onset was defined as the date of first non-Raynaud’s symptom. A detailed explanation of each data source and its specific contribution to the dataset can be found in Supplemental Section 1.

Diagnoses of limited cutaneous SSc (lcSSc), diffuse cutaneous SSc (dcSSc), or scleroderma sine scleroderma (SSS) were confirmed by adjudication of EHR data by a board-certified rheumatologist (C.R.). Cases with mixed connective tissue disease or overlap with another connective tissue disease(s) were excluded. Lung transplantation was treated as equivalent to death, and data post-transplantation was excluded. Diagnoses of SSc-ILD were adjudicated by review of radiology reports of chest CT imaging by experts in ILD (A.J.E., B.C.B., J.E.D.) utilizing a three-reader method that has been previously described.33,34 In cases of disagreement between readers, consensus was obtained through collaborative discussion of the report. Readers were blinded to their initial assessment during consensus adjudication. Participants with persistent uncertainty of ILD diagnosis despite collaborative adjudication were labeled as “unknown” and excluded from subgroup analyses of SSc-ILD. It is important to note that CT images were not reviewed by the readers, as the aim of this study was to utilize EHR data alone, and not imaging data, for predictive modeling. Mortality was adjudicated by recorded dates of death or lung transplant from the EHR and REDCap database.

Data Pre-Processing and Feature Selection

Clinical features such as age, sex, race, autoantibody status (anti-topoisomerase I (Scl-70), anticentromere (ACA), anti-RNA polymerase III (RNA Pol III)), pulmonary hypertension (PH) status (no PH, pre-capillary PH, post-capillary PH), and time-to-event intervals (e.g., time from SSc diagnosis to ILD diagnosis) were collected. A total of seventy-four features were selected through multidisciplinary expert adjudication of potential clinical relevance. A known association between SSc or SSc-ILD was not required for a feature to be included in the model. The features were grouped into demographics, vital signs, six-minute walk tests, PFTs, complete blood counts (CBC), autoantibody profiles, and chemistries (see Supplemental Section 1). Features were described by either continuous or categorical (binary or ordinal) data types.

Features were grouped into year-by-year aggregates based on the first measurement for each patient (Figure 1). A participant’s first year would start at his or her first measurement and every following year was subsequently incremented. If multiple measurements occurred within the same year, values were averaged. Missing values were handled differently depending on the modeling approach: XGBoost35 and LightGBM36 utilized raw feature values without imputation, whereas all other models applied binning-based imputation as described in Supplemental Section 2.

Figure 1. Labeling strategy and modeling tasks for ILD detection, mortality prediction in all SSc participants, and mortality prediction in participants with SSc-ILD.

(A): ILD Detection. Displays the timeline for ILD detection based on CT scan results. Participants with no evidence of ILD are labeled as “0,” transitioning to “−1” during uncertain periods (e.g., after negative CT and before CT establishing ILD diagnosis) and “1” after ILD is confirmed by CT. Each green marker represents a CT scan without ILD, while red markers represent CTs confirming ILD. (B): Mortality Prediction in all SSc participants. Labels are determined by proximity to the death/lung transplant event, represented by the brown vertical line. If the end of a yearly bin falls within the specified prediction window from the time of death/transplant, the label is “1” (blue); otherwise, it is “0” (green) (e.g., Death_3 = Participant Died within 3 years from the end of the current year bin. (C): Mortality Prediction in participants with SSc-ILD. Focuses on SSc-ILD participants, where mortality prediction begins one year before ILD diagnosis (marked in red). Annual prediction bins are used. Similar to Panel B, the brown line marks the time of death/lung transplant. Labels are “1” (blue) if the end of a bin falls within the corresponding prediction window from the death/transplant event, and “0” (green) otherwise.

Clustering and Phenotypic Analysis

Hierarchical clustering was applied to identify phenotypic groups using features such as autoantibody status, SSc subtype, age at SSc diagnosis, and ILD status. Specifically, we employed agglomerative hierarchical clustering using Euclidean distance metrics and the complete linkage method, implemented through the Morpheus package. This approach maximizes the distance between elements of each cluster, resulting in more compact well-separated phenotypic groupings. We determined that ten was the optimal number of clusters through iteratively increasing the number of clusters until the addition of a new cluster no longer provided meaningful clinical differentiation, as determined by a multidisciplinary team of SSc and ILD experts (A.J.E., J.E.D, B.C.B, C.R.). This approach enabled the identification of distinct participant profiles, which were subsequently analyzed for patterns related to development of ILD and mortality.

Modeling Outcomes of Interest

Modeling Task 1 (ILD detection in participants with SSc):

To identify whether a participant with SSc currently has ILD using solely annual EHR data. The purpose of this task was to associate previously unrecognized biomarkers with disease.

Modeling Task 2 (Mortality prediction in participants with SSc):

To predict participant mortality (or lung transplant) within one, three, and five years from first EHR data entry using annualized EHR-derived data from all participants with SSc in the Registry. This model utilizes ILD as a feature, which distinguishes it from Task 3.

Modeling Task 3 (Mortality prediction in participants with known SSc-ILD):

To predict mortality (or lung transplant) after ILD diagnosis within one, three, and five years from the ILD diagnosis using annualized EHR-derived data from a subgroup of participants with an adjudicated SSc-ILD diagnosis. Data within one year prior to ILD onset were grouped into the first prediction window, with subsequent years aggregated into annual bins (Figure 1).

Statistical Methods

Comparative analyses between participant groups were conducted using the non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables given the potential for non-normally distributed data across features. Sample proportions were compared by chi-squared analysis. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were generated to assess time-to-event outcomes, and comparisons between groups were performed using the log-rank test. For predictive modeling tasks, model performance was evaluated using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis with the area under the curve (AUC) reported to quantify discriminatory ability. All statistical tests were two-sided with significance defined at a threshold of p < 0.05.

Modeling and Framework

We employed Logistic Regression (LR)37, Random Forest Classifier (RF)38, XGBoost,35 LightGBM36, and Neural Networks (NN)39 ML models to direct ILD detection and mortality prediction tasks. Hyperparameter optimization was conducted using Optuna,40 with twenty-five trials per model-task pair. Model selection was based on five-fold cross-validation scores. Missing data were addressed with an imputation pipeline combining quartile binning (continuous features), mask-based encoding (missing features), and one-hot encoding (categorical features). Feature importance was evaluated using SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP)41 and ablation studies, identifying key predictors and assessing model robustness to missing data. A detailed description of the model framework, imputation strategy, and optimization process can be found in Supplemental Section 2.

Code and Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during this study are currently not publicly available. The code used for data processing and model development is available on GitHub: https://github.com/NUPulmonary/SScILD-EHR-M1.

RESULTS

We recruited 1,169 patients with SSc to participate in this study from the Northwestern Scleroderma Registry. The cohort contained EHR data encompassing a total of 15,494 person-years of observation. The cohort was predominantly female (84.0%), of White race (83.3%), with a median age of forty-five years at time of SSc diagnosis (Table 1). lcSSc accounted for 60.0% of the cohort; 35.2% had dcSSc. Autoantibody analysis revealed that 26.8% of participants had abnormal titers of Scl-70, 22.7% had abnormal ACA, and 16.9% had abnormal RNA Pol III.

Table 1.

Cohort Characteristics.

| Full Cohort | CT Subgroup* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| N (%) | 1169 (100) | 709 (60.7) | ||

| Age at SSc Diagnosis, years, median [Q1, Q3] | 45.4 [35.4, 54.3] | 45.1 [36.0, 53.4] | ||

| Sex, female, n (%) | 982 (84.0) | 585 (82.5) | ||

| Race, n (%) | ||||

| Asian | 43 (3.7) | 26 (3.7) | ||

| Black | 122 (10.4) | 96 (13.5) | ||

| White | 974 (83.3) | 567 (80.0) | ||

| Other | 30 (2.6) | 20 (2.8) | ||

| Ethnicity, n (%) | ||||

| Hispanic or Latino | 94 (8.0) | 66 (9.3) | ||

| Non-Hispanic or Latino | 1054 (90.2) | 636 (89.7) | ||

| Unknown | 21 (1.8) | 7 (1.0) | ||

| Tobacco Smoking Status | ||||

| Current Smoker | 41 (3.5) | 20 (2.8) | ||

| Former Smoker | 247 (21.1) | 163 (23.0) | ||

| Never Smoker | 407 (34.8) | 273 (38.5) | ||

| Unknown | 474 (40.5) | 253 (35.7) | ||

| Alive, n (%) | 977 (83.6) | 566 (79.8) | ||

| Scleroderma Subtype, n (%) | ||||

| Limited Cutaneous | 701 (60.0) | 377 (53.2) | ||

| Diffuse Cutaneous | 411 (35.2) | 297 (41.9) | ||

| Sine Scleroderma | 57 (4.9) | 35 (4.9) | ||

| Autoantibodies ** | ||||

| Scl-70, n (%) | 313 (26.8) | 240 (33.9) | ||

| Centromere, n (%) | 265 (22.7) | 147 (20.7) | ||

| RNA polymerase III, n (%) | 197 (16.9) | 138 (19.5) | ||

| ILD Status | ||||

| Negative ILD | 255 (21.8) | 255 (36.0) | ||

| Incident ILD | 34 (2.9) | 34 (4.8) | ||

| Prevalent ILD | 420 (35.9) | 420 (59.2) | ||

| Unknown (No CT scan) | 460 (39.3) | - | ||

| SSc to ILD Onset, years, median [Q1, Q3] | - | 3.4 [1.2, 7.9] | ||

| CT Chest Images Available, n (%) † | 685 (58.6) | 605 (85.3) | ||

| Number of CTs per Participant, median [Q1, Q3] ‡ | - | 2.0 [1.0, 5.0] | ||

| PFT Available, n (%) | 905 (77.4) | 651 (91.8) | ||

| Number of PFTs per Participant, median [Q1, Q3] | 4.0 [2.0, 8.0] | 5.0 [2.0, 10.0] | ||

| Pulmonary Hypertension Status, n (%) § | ||||

| No Pulmonary Hypertension | 99 (8.5) | 90 (12.7) | ||

| Pre-Capillary Pulmonary Hypertension | 134 (11.5) | 112 (15.8) | ||

| Post-Capillary Pulmonary Hypertension | 74 (6.3) | 64 (9.0) | ||

| Unknown | 862 (73.7) | 443 (62.5) | ||

Participants were only included in this subgroup if at least one CT chest imaging report was available for adjudication of ILD diagnosis.

Participants can be negative for all three major SSc-associated autoantibodies or have missing data for specific autoantibodies (See Supplemental Section 1 for further details).

104 participants had external CT imaging reports available without accessible images for review.

Only includes participants with at least one CT scan representative of the subgroup participants with CT data available.

Pulmonary Hypertension definitions are based on right heart catheterization data. Participants were categorized as “no PH”, “pre-capillary PH”, or “post-capillary PH” using mean pulmonary arterial pressure and pulmonary vascular resistance values. See Supplemental Section 1 for full criteria and longitudinal classification methodology.

In subgroup analyses (“CT Subgroup”), we included those participants who had at least one CT chest imaging report available for multidisciplinary adjudication of ILD in our model to detect ILD and predict mortality in participants with SSc-ILD. The median number of CT chest reports available was two (interquartile range: 1–4) per participant. The subgroup of participants who had an available CT report had a lower proportion of lcSSc (53.2%) compared to the full cohort (60%; p=0.0045). In contrast, the proportion of dcSSc was higher in the CT subgroup (41.9%) compared to the full cohort (35.2%; p = 0.0041). Similarly, a higher proportion of the CT subgroup tested positive for Scl-70 (33.9%) autoantibody compared to the full cohort (26.8%; p = 0.0013).

Longitudinal Follow-Up, Clinical Engagement, and Survival Trends in SSc and SSc-ILD

The median duration of participant follow-up was 6.2 years (Figure 2A), and 56.5% of participants had more than five years of follow-up. The number of participants who were lost-to-follow-up was 519 (44.4%). Because only 14.0% of participants from the full cohort were enrolled before 2015, most data reflect more recent clinical encounters. A smaller subset of participants (3.3%) was observed over two decades. The number of clinical encounters per year increased over time (Figure 2B). Similarly, the number of active participants under observation by year (Figure 2C) increased progressively, peaking around 2016.

Figure 2. Longitudinal characteristics of the Northwestern Scleroderma Registry cohort.

(A) Distribution of participant follow-up duration binned by number of years. (B) Number of clinical encounters for the aggregate Registry cohort over time. (C) Cumulative number of active participants (blue), lost to follow-up (orange), and death (red) over time. (D) Age at SSc diagnosis subgrouped by sex. (E) Kaplan-Meier survival curves comparing SSc participants with and without ILD within the CT Subgroup cohort. NOTE: Of the CT Subgroup cohort (n=709), 9 participants were excluded from the survival analysis due to missing non-Raynaud’s onset data.

Age at SSc diagnosis was normally distributed (Figure 2D) with a peak incidence around forty-five years, consistent with prior literature.7 Sex-based differences were apparent, with female participants (44.0 years) demonstrating an earlier median age at diagnosis compared to males (46.5 years; p=0.0082), aligning with known epidemiological patterns in SSc.7

As expected, participants with SSc-ILD had significantly shorter survival than SSc participants without ILD (Figure 2E). Time-to-event analysis of the CT subgroup demonstrated a significant survival advantage for participants without ILD compared to those with ILD (median survival 36.9 vs 29.1 years from diagnosis; p < 0.0001). While these durations appear longer than typically reported in clinical studies,42,43 there was a 5.4-year reduction in median survival for those with ILD compared to those without ILD.

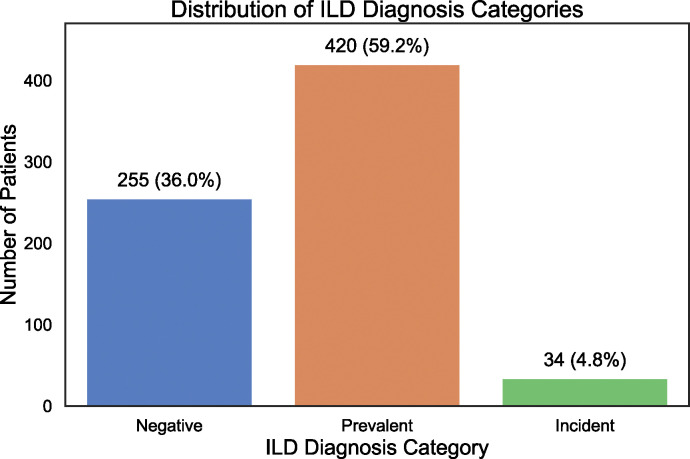

Characteristics of SSc-ILD in Cohort

A subgroup of 709 participants—included if at least one CT chest imaging report was available for review—underwent multidisciplinary adjudication for ILD diagnosis (“CT Subgroup” Characteristics are in Table 1). 454 participants (64%) in this subgroup had definitive evidence of ILD (Figure 3). Of those with confirmed ILD, the overwhelming majority had evidence of ILD on their first CT evaluation (n=420 or 93%), defined as “prevalent ILD”. A smaller proportion (n=34 or 7% of those with confirmed ILD) were diagnosed with ILD after an initial negative CT evaluation, defined as “incident ILD”.

Figure 3. Distribution of ILD diagnosis by expert adjudication of radiologic reports in SSc participants in the Northwestern University Scleroderma Registry.

Phenotypic Clusters within SSc Cohort

To explore phenotypic heterogeneity in our SSc cohort, we performed hierarchical clustering on clinical and disease-related features, ILD status if a CT was available, autoantibody status, age at SSc diagnosis, and highest recorded modified Rodnan skin score (mRSS) (Figure 4). Demographic and clinical characteristics were overlaid as annotations to contextualize the identified clusters. Cluster 6 was dominated by ACA-positive participants, lcSSc, and no ILD (88.3% of participants in this cluster had concomitant lcSSc and ACA+). Scl-70-positive participants, on the other hand, were associated with mostly dcSSc participants and exhibited a higher prevalence of ILD as shown in clusters 7 and 8 (47.7% and 52.2% respectively). Additionally, clusters 3 and 8 were predominantly participants who were RNA Pol III-positive, dcSSc, and had SSc-ILD.

Figure 4. Hierarchical clustering of SSc participants reveals distinct clinical and ILD-associated phenotypic subgroups.

Each vertical column represents an individual participant of the 1,169 participants with SSc in the full cohort. The top section includes participant demographics and clinical characteristics, which were not employed in cluster analysis. The bottom section displays hierarchical clustering (clusters=10) results.

We further explored the three subgroupings of ILD diagnosis (negative, prevalent, incident) to better understand the timing and frequency of ILD onset in SSc participants. We observed that many of the participants with negative ILD status had limited long-term follow-up, with 255 of these participants undergoing a cumulative 609 CT scans. Peak frequency occurred within the first two years (Supplementary Figure 1A). For those with prevalent ILD, 247 of 420 participants (58.8%) received their baseline CT two years after their first non-Raynaud symptom (Supplementary Figure 1B). Most cases of ILD following the last negative CT were diagnosed within the first two years of follow-up (52.9%), with the highest incidence (seven participants) occurring in the first six months (Supplemental Figure 1C). When considering time from the first non-Raynaud symptom, ILD was diagnosed within three years in 38.2% of incident ILD participants (Supplementary Figure 1D).

Feature distributions with respect to ILD and mortality also highlighted differences in mortality: 75% of deceased participants had ILD compared to 62% of survivors (p<0.001). Supplemental Figures 3A and 3B display comparisons between both ILD and mortality across the identified phenotypes.

Feature Averaging

For modeling purposes, data was averaged on a yearly basis beginning with the participant’s initial datapoint collected. Supplemental Figure 4 quantifies the extent of averaging applied. Many yearly bins did not require averaging for the majority of features; however, even with features that required averaging, the coefficient of variation remained relatively low across the averaged values.

ILD Detection

We developed ML models to detect ILD solely using data from the EHR (Figure 5). The LightGBM model achieved robust performance, with an AUC of 0.818, to distinguish participants with ILD from those without ILD. SHAP analysis highlighted autoantibodies, particularly ACA and Scl-70, as key detectors of ILD (e.g., ACA-negative participants were more likely to have ILD than those who were ACA-positive). Functional parameters (DLCO, FVC), PH, smoking status, and advanced age were also predictive of ILD.

Figure 5. Model performance and feature importance in ILD detection.

Performance of the LightGBM model in ILD detection. The ROC curve (A) shows strong discriminative ability (AUC 0.818). SHAP analysis (B) identifies key features of ILD detection.

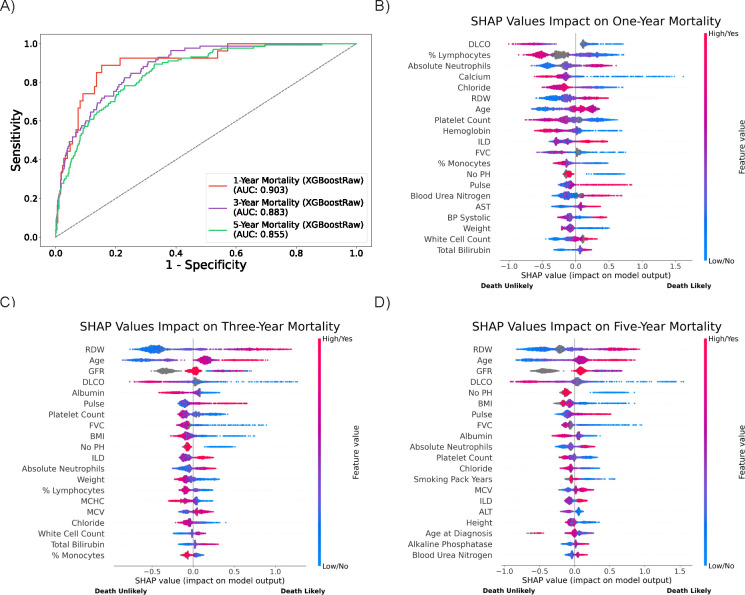

Mortality Prediction in Overall SSc Cohort

Mortality prediction models were evaluated for one-, three-, and five-year survival after SSc diagnosis. The XGBoostRaw model achieved the best performance for the tasks of one- (AUC 0.903), three- (AUC 0.883), and five-year mortality prediction (AUC 0.855) (Figure 6) compared to other tested models.

Figure 6. Model performance and feature importance in mortality prediction.

ROC curves (A) for mortality prediction over one-, three-, and five-year intervals show declining performance with longer time horizons. Feature importance plots (B, C, D) highlight shifting predictors from laboratory values in the short term to chronic disease markers over longer periods.

Feature importance analyses revealed dynamic shifts in predictors across time horizons. Clinical measurements associated with acute disease—such as serum calcium concentration, red cell distribution width (RDW), platelet count, absolute neutrophils, percent lymphocytes, and serum chloride concentration—were the strongest drivers of one-year mortality risk along with DLCO. For three- and five-year prediction models, chronic disease markers—including PFT parameters (DLCO), laboratory values (for example, RDW and glomerular filtration rate (GFR)), and demographic factors (age)—were more important predictors. Distributions of these key features across outcome labels further support their relevance, with higher RDW levels notably associated with both ILD diagnosis and increased mortality risk (Supplementary Figure 5).

Mortality Prediction in Participants with SSc-ILD

To explore the unique impact of ILD on mortality in SSc patients, we developed models specific to participants with SSc-ILD. The XGBoostRaw model again demonstrated the highest performance for the tasks of one- (AUC 0.759), three- (AUC 0.831) and five-year mortality prediction (AUC 0.822) (Figure 7) compared to other models.

Figure 7. Model performance and feature importance in mortality prediction for participants with SSc-ILD.

ROC curves (A) for mortality prediction in participants with confirmed SSc-ILD over one-, three-, and five-years show distinct patterns compared to mortality in the general SSc cohort. Feature importance plots (B,C,D) reveal evolving predictors, from vital signs and labs at one-year to demographics and chronic disease markers by five-years.

Short-term mortality in participants with SSc-ILD was influenced by vital signs and laboratory markers (e.g., blood pressure (BP), pulse, serum bicarbonate level, serum blood urea nitrogen level); conversely, long-term prediction models highlighted chronic disease markers (DLCO, albumin, RDW, GFR) and demographic factors (age, body mass index (BMI)).

DISCUSSION

Our study leveraged a large, single-center registry of participants with SSc containing data collected longitudinally from the EHR. We employed ML algorithms to these data to detect ILD and to predict all-cause mortality in both all-comers with SSc and a subgroup of those with SSc-ILD. The resultant models yielded high predictive accuracy in assessing risk for these clinically important outcomes with AUC ranging from 0.759 to 0.903. While the models identified important biomarkers previously associated with SSc-ILD progression such as impaired pulmonary function and autoantibody status, many were unexpected (e.g., RDW, GFR, serum chloride/calcium levels) and, importantly, are routinely collected in the care of patients with SSc. Furthermore, these predictive features often have values that fall within the normal range, increasing the likelihood that they would be overlooked in a busy clinical practice. The ability of our models to highlight these novel biomarkers underscores the potential of ML to refine risk stratification and ultimately guide early interventions for SSc-ILD.

Our cohort of SSc participants represents one of the largest studies of its kind and demonstrates similar patient characteristics previously described within other cohorts. Like other large SSc registries such as the European Scleroderma Trials and Research (EUSTAR) Group,44 our cohort predominantly consisted of middle-aged female participants with either limited or diffuse cutaneous disease. The prevalence of ILD in our dataset is higher than those in other cohort studies.5–8 Although this might result from selection bias, the alignment of our cohort’s clinical characteristics with prior studies suggests that our findings are generalizable. Specifically, we observed a strong association between ILD and Scl-70 positivity as well as dcSSc, both of which are well-documented risk factors for ILD development and progression. Also consistent with findings in the literature, lcSSc and ACA positivity were associated with a lower prevalence of ILD.5 As predicted, RNA Pol III positivity was strongly correlated with dcSSc. Interestingly, clusters enriched for RNA Pol III-positive dcSSc participants contained fewer deceased individuals, suggesting a different disease trajectory in this subgroup. Indeed, others have identified an association between RNA Pol III positivity and dcSSc with disease trajectory and mortality risk.45,46 These observations are further supported by our feature importance visualizations, which highlighted RNA Pol III-positive lcSSC participants as having stronger association with ILD but weaker association with all-cause mortality.

Our results demonstrate that most cases of ILD (92.5%) were detected on a participant’s first available CT. Those with a normal initial screening CT developed incident ILD in only 7.5% of the cohort. These results align with prior findings from the EUSTAR Group, which reported that only 8.2% of participants developed ILD during follow-up.47 This underscores the importance of recently published ACR/American College of Chest Physicians Screening Guidelines conditionally recommending CT screening for ILD at the time of diagnosis of SSc.48 While some patients develop ILD later, the rarity of incident cases suggests that baseline imaging plays a key role in risk stratification.

Current diagnosis and monitoring of SSc-ILD is limited primarily to PFTs and CT scans of the chest. Although the latter is the gold standard for detection, current guidelines from professional societies conditionally recommend a single baseline screening chest CT at diagnosis of SSc. They do not provide explicit guidance on when to repeat imaging in patients who are high-risk for incident ILD,48 which is a small but not insignificant proportion of patients.12 A similar dilemma surrounds timing and selection of therapies for SSc-ILD, many of which have demonstrated efficacy in altering the course of disease.21–23 While there is mounting evidence that most patients with SSc-ILD will progress,13,14 clinical tools to identify those at high-risk are lacking. Our study extends the use of ML as a clinical tool to a large, longitudinal cohort of patients with SSc. ML is capable of integrating large volumes of data and may aid clinicians in identifying those who are high risk and guide clinical personalized decision-making.49–51 Conversely, ML may also identify those at low risk for poor clinical outcomes and provide the clinician with guidance on which patients may be appropriate for discontinuation of immunomodulatory therapy, a common scenario that currently has little guidance in clinical practice outside expert opinion.20

Unsurprisingly, established predictors of SSc-ILD—including negative ACA, positive Scl-70, and lower DLCO—were among the most important features in our ML models. However, our analyses also identified routine clinical measurements, such as serum chloride level, white blood cell count, and RDW, as predictive of ILD status. These clinical measurements—readily available in the EHR—may be commonly overlooked during evaluation of ILD, as they are not classic markers of disease and, even within our cohort, most values were reported in the normal range. In a previous study, investigators identified an association between RDW and changes in FVC and DLCO in participants with SSc-ILD and other connective tissue diseases.52,53 Our findings provide an unbiased validation of these observations and suggest that commonly measured EHR features could provide additional diagnostic and prognostic value and possibly insights into disease pathogenesis.

In assessing mortality risk, our models demonstrated high predictive performance, particularly for one-year mortality (AUC 0.903). In short-term predictions (e.g., one-year mortality), laboratory values associated with acute disease—such as percent lymphocyte differential, absolute neutrophil count, serum calcium concentration, and serum chloride concentration—were the strongest markers of risk, suggesting that rapidly deteriorating clinical states contribute significantly to early mortality.54 However, in longer-term prediction models (three- and five-year mortality models), chronic disease markers—including DLCO, RDW, age, and GFR—were more prominent, suggesting that persistent physiologic decline and demographic factors are important determinants of long-term survival.

When assessing mortality risk specifically among SSc-ILD participants, our models exhibited moderate predictive accuracy (AUC 0.759–0.831), with vital signs and laboratory markers predominating in early mortality prediction and PFT parameters mounting importance in later outcomes. These data suggest that while acute clinical events may precipitate early mortality in ILD patients, long-term survival is dictated by chronic respiratory decline. The strong association between DLCO and mortality risk reinforces the well-established role of gas exchange impairment as a key predictor of outcomes in ILD,55 further supporting its role as a primary monitoring tool in the management of SSc-ILD.

Our study has several limitations. First, our retrospective single-center design may introduce referral and selection bias, particularly in terms of ILD prevalence and follow-up patterns. While our cohort is large and representative of broader SSc populations, external validation in independent datasets is necessary to confirm the generalizability of our findings. Second, ILD classification was based on expert adjudication of CT reports rather than direct imaging analysis, which could introduce inter-reader variability. This methodology was implemented intentionally, as the goal of our study was to utilize available EHR data and not rely on physician assessment of imaging. The methods employed, therefore, could lead to classification bias of ILD. However, we believe that use of only the EHR data allows this model to be translated into settings that lack expert adjudication of ILD diagnoses, expanding its use beyond tertiary care centers. Next, the sporadic and retrospective nature of EHR data presents a challenge in ML modeling. For example, PFT, CT, and laboratory data were collected at varying intervals and not at random. Our model approached this unstructured dataframe by averaging values annually, which may have led to insensitive attention to variation in data over a short timeframe. Regardless, our models were able to robustly predict patient outcomes despite the averaging we employed and the coefficient of variation of the features was low. Future work should explore the integration of deep learning-based image analysis to enhance diagnostic accuracy. Finally, our models relied on structured EHR data downloaded from a repository, which may underrepresent important clinical features that are captured in unstructured physician notes, such as patient-reported symptoms or nuanced disease severity assessments. Additional studies should consider use of natural language processing approaches to extract these data that may further refine predictive performance of our models.

CONCLUSIONS

Our findings demonstrate that ML models can effectively identify ILD and predict risk of mortality in patients with SSc using routinely collected, and potentially overlooked due to “normal” values, EHR data. The ability of our models to detect ILD at or before clinical diagnosis suggests that predictive modeling may enhance early screening efforts, foreseeably acting as an “early warning signal” to enable earlier intervention to promote improved outcomes through prevention of loss of lung function. Moreover, the identification of both established and previously unrecognized biomarkers could inform risk stratification and disease monitoring. Given the challenges inherent to management of SSc-ILD, integrating ML-driven risk assessment into routine care could support proactive clinical decision-making, shifting the paradigm from reactive treatment of progressive disease toward prevention. Future prospective studies are needed to validate these models in external cohorts and to explore their potential for real-time deployment in clinical settings to ultimately improve patient outcomes in this complex, heterogeneous, and high-risk population.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported in part through a generous gift from K. Querrey and L. Simpson. This research was also supported by the computational resources and staff contributions provided for the Quest high-performance computing facility at Northwestern University, which is jointly supported by the Office of the Provost, the Office for Research, and Northwestern University Information Technology. This research was also supported in part through the computational resources and staff contributions provided by the Genomics Compute Cluster, which is jointly supported by the Feinberg School of Medicine, the Center for Genetic Medicine, Feinberg’s Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Genetics, the Office of the Provost, the Office for Research, and Northwestern Information Technology. The Genomics Compute Cluster is part of Quest, Northwestern University’s high-performance computing facility, with the purpose of advancing research in genomics. N.S.M. was supported by the American Heart Association (grant no. 24PRE1196998). M.H. was supported by the NIH (grant no. R01AR07327). C.A.G. was supported by the NIH (grant no. K23HL169815), a Parker B. Francis Opportunity Award, and an American Thoracic Society Unrestricted Grant. R.G.W. is supported by the NIH (grant nos. U19AI135964, R01AI158530, R01HL149883, P01HL154998, U01TR003528). G.R.S.B. was supported by a Chicago Biomedical Consortium grant, Northwestern University Dixon Translational Science Award, Simpson Querrey Lung Institute for Translational Science, the NIH (grant nos. P01AG049665, P01HL154998, U54AG079754, R01HL147575, R01HL158139, R01HL147290, R21AG075423 and U19AI135964), and the Veterans Administration (award no. I01CX001777). A.V.M. was supported by the NIH (grant nos. U19AI135964, P01AG049665, P01HL154998, U19AI181102, R01HL153312, R01HL158139, R01ES034350 and R21AG075423). A.A. was supported by the NIH (grant nos. U19AI135964 and R01HL158138) and Simpson Querrey Lung Institute for Translational Science. A.J.E. was supported by the NIH (grant no. L30HL149048). The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Systemic sclerosis. Lancet 401, 304–318 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khanna D. et al. Etiology, Risk Factors, and Biomarkers in Systemic Sclerosis with Interstitial Lung Disease. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 201, 650–660 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Elhai M. et al. Mapping and predicting mortality from systemic sclerosis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 76, 1897–1905 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tyndall A. J. et al. Causes and risk factors for death in systemic sclerosis: a study from the EULAR Scleroderma Trials and Research (EUSTAR) database. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 69, 1809–1815 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walker U. A. et al. Clinical risk assessment of organ manifestations in systemic sclerosis: a report from the EULAR Scleroderma Trials And Research group database. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 66, 754–763 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoffmann-Vold A.-M. et al. Tracking impact of interstitial lung disease in systemic sclerosis in a complete nationwide cohort. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 200, 1258–1266 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bergamasco A., Hartmann N., Wallace L. & Verpillat P. Epidemiology of systemic sclerosis and systemic sclerosis-associated interstitial lung disease. Clin. Epidemiol. 11, 257–273 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gupta R. S., Koteci A., Morgan A., George P. M. & Quint J. K. Incidence and prevalence of interstitial lung diseases worldwide: a systematic literature review. BMJ Open Respir. Res. 10, (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jaeger V. K. et al. Incidences and risk factors of organ manifestations in the early course of systemic sclerosis: A longitudinal EUSTAR study. PLoS One 11, e0163894 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoffmann-Vold A.-M. et al. Predictive value of serial high-resolution computed tomography analyses and concurrent lung function tests in systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 67, 2205–2212 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Distler O. et al. Predictors of progression in systemic sclerosis patients with interstitial lung disease. Eur. Respir. J. 55, 1902026 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoa S. et al. Characterization of incident interstitial lung disease in late systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Rheumatol. (2024) doi: 10.1002/art.43051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scheidegger M. et al. Characteristics and disease course of untreated patients with interstitial lung disease associated with systemic sclerosis in a real-life two-centre cohort. RMD Open 10, (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoffmann-Vold A.-M. et al. Progressive interstitial lung disease in patients with systemic sclerosis-associated interstitial lung disease in the EUSTAR database. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 80, 219–227 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abraham D. J. et al. An international perspective on the future of systemic sclerosis research. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 21, 174–187 (2025). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khanna S. A., Nance J. W. & Suliman S. A. Detection and Monitoring of Interstitial Lung Disease in Patients with Systemic Sclerosis. Curr. Rheumatol. Rep. 24, 166–173 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bernstein E. J. et al. Performance characteristics of pulmonary function tests for the detection of interstitial lung disease in adults with early diffuse cutaneous systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 72, 1892–1896 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moran-Mendoza O., Ritchie T. & Aldhaheri S. Fine crackles on chest auscultation in the early diagnosis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a prospective cohort study. BMJ Open Respir. Res. 8, e000815 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Launay D. et al. High resolution computed tomography in fibrosing alveolitis associated with systemic sclerosis. J. Rheumatol. 33, 1789–1801 (2006). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rahaghi F. F. et al. Expert consensus on the management of systemic sclerosis-associated interstitial lung disease. Respir. Res. 24, 6 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Distler O. et al. Nintedanib for Systemic Sclerosis–Associated Interstitial Lung Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 380, 2518–2528 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tashkin D. P. et al. Mycophenolate mofetil versus oral cyclophosphamide in scleroderma-related interstitial lung disease (SLS II): a randomised controlled, double-blind, parallel group trial. Lancet Respir. Med. 4, 708–719 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khanna D. et al. Tocilizumab in systemic sclerosis: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Respir Med 8, 963–974 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Volkmann E. R. et al. Short-term progression of interstitial lung disease in systemic sclerosis predicts long-term survival in two independent clinical trial cohorts. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 78, 122–130 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Soffer S. et al. Artificial Intelligence for Interstitial Lung Disease Analysis on Chest Computed Tomography: A Systematic Review. Acad. Radiol. 29, S226–S235 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Raghu G. et al. An Official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT Statement: Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis: Evidence-based Guidelines for Diagnosis and Management. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 183, 788–824 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Walsh S. L. F. et al. Role of imaging in progressive-fibrosing interstitial lung diseases. Eur. Respir. Rev. 27, (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mei X. et al. Interstitial lung disease diagnosis and prognosis using an AI system integrating longitudinal data. Nat. Commun. 14, 2272 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Allam A. et al. Predicting interstitial lung disease progression in patients with systemic sclerosis using attentive neural processes - a EUSTAR study. medRxiv (2024) doi: 10.1101/2024.04.25.24306365. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Starren J. B., Winter A. Q. & Lloyd-Jones D. M. Enabling a Learning Health System through a Unified Enterprise Data Warehouse: The Experience of the Northwestern University Clinical and Translational Sciences (NUCATS) Institute. Clin. Transl. Sci. 8, 269–271 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Preliminary criteria for the classification of systemic sclerosis (scleroderma). Subcommittee for scleroderma criteria of the American Rheumatism Association Diagnostic and Therapeutic Criteria Committee. Arthritis Rheum. 23, 581–590 (1980). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van den Hoogen F. et al. 2013 classification criteria for systemic sclerosis: an American College of Rheumatology/European League against Rheumatism collaborative initiative. Arthritis Rheum. 65, 2737–2747 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Washko G. R. et al. Lung volumes and emphysema in smokers with interstitial lung abnormalities. N. Engl. J. Med. 364, 897–906 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Washko G. R. et al. Identification of Early Interstitial Lung Disease in Smokers from the COPDGene Study. Acad. Radiol. 17, 48–53 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.XGBoost | Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining. https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/2939672.2939785.

- 36.Ke G. et al. LightGBM: A Highly Efficient Gradient Boosting Decision Tree. in Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems vol. 30 (Curran Associates, Inc., 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Introduction to the Logistic Regression Model. in Applied Logistic Regression 1–33 (John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Breiman L. Random Forests. Mach. Learn. 45, 5–32 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pedregosa F. et al. Scikit-learn: Machine Learning in Python. arXiv (2018) doi: 10.48550/arXiv.1201.0490. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Akiba T., Sano S., Yanase T., Ohta T. & Koyama M. Optuna: A next-generation hyperparameter optimization framework. (2019). doi: 10.1145/3292500.3330701. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lundberg S. M. & Lee S.-I. A Unified Approach to Interpreting Model Predictions. in Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems vol. 30 (Curran Associates, Inc., 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 42.De Almeida Chaves S. et al. Sine scleroderma, limited cutaneous, and diffused cutaneous systemic sclerosis survival and predictors of mortality. Arthritis Res. Ther. 23, 295 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rubio-Rivas M., Royo C., Simeón C. P., Corbella X. & Fonollosa V. Mortality and survival in systemic sclerosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 44, 208–219 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lescoat A. et al. Cutaneous Manifestations, Clinical Characteristics, and Prognosis of Patients With Systemic Sclerosis Sine Scleroderma: Data From the International EUSTAR Database. JAMA Dermatol. 159, 837–847 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wielosz E., Dryglewska M. & Majdan M. Clinical consequences of the presence of anti-RNA Pol III antibodies in systemic sclerosis. Postepy Dermatol. Alergol. 37, 909–914 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.The Prognosis Of Scleroderma Renal Crisis In RNA-Polymerase III Antibody (ARA) Positive Compared To ARA Negative Patients. ACR Meeting Abstracts https://acrabstracts.org/abstract/the-prognosis-of-scleroderma-renal-crisis-in-rna-polymerase-iii-antibody-ara-positive-compared-to-ara-negative-patients/. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bruni C. et al. Pos0235 New Onset of Interstitial Lung Disease in Systemic Sclerosis: Clinical Course and Outcomes from a Eustar Database Analysis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 83, 337–338 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Johnson S. R. et al. 2023 American College of Rheumatology (ACR)/American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST) Guideline for the Screening and Monitoring of Interstitial Lung Disease in People with Systemic Autoimmune Rheumatic Diseases. Arthritis Care Res. (Hoboken) 76, 1070–1082 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Murdaca G. et al. A Machine Learning application to predict early lung involvement in Scleroderma: A feasibility evaluation. Diagnostics (Basel) 11, 1880 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chassagnon G. et al. Deep learning-based approach for automated assessment of interstitial lung disease in systemic sclerosis on CT images. Radiol. Artif. Intell. 2, e190006 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schniering J. et al. Computed tomography-based radiomics decodes prognostic and molecular differences in interstitial lung disease related to systemic sclerosis. Eur. Respir. J. 59, 2004503 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ebata S. et al. Increased Red Blood Cell Distribution Width in the First Year after Diagnosis Predicts Worsening of Systemic Sclerosis-Associated Interstitial Lung Disease at 5 Years: A Pilot Study. Diagnostics (Basel) 11, 2274 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shi S. et al. Association of Red Blood Cell Distribution Width Levels with Connective Tissue Disease-Associated Interstitial Lung Disease (CTD-ILD). Dis. Markers 2021, 5536360 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Foy B. H. et al. Haematological setpoints are a stable and patient-specific deep phenotype. Nature 637, 430–438 (2025). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rose L. et al. Survival in pulmonary hypertension due to chronic lung disease: Influence of low diffusion capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 38, 145–155 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cooper B. G. et al. The Global Lung Function Initiative (GLI) Network: bringing the respiratory reference values together. Breathe (Sheff) 13, e56–e64 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bowerman C. et al. A Race-neutral Approach to the Interpretation of Lung Function Measurements. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 207, 768–774 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate (eGFR) | National Kidney Foundation. https://www.kidney.org/kidney-topics/estimated-glomerular-filtration-rate-egfr. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.