Abstract

This Perspective covers discovery and mechanistic aspects as well as initial applications of novel ionization processes for use in mass spectrometry that guided us in a series of subsequent discoveries, instrument developments, and commercialization. Vacuum matrix-assisted ionization on an intermediate pressure matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization source without the use of a laser, high voltages, or any other added energy was simply unbelievable, at first. Individually and as a whole, the various discoveries and inventions started to paint, inter alia, an exciting new picture and outlook in mass spectrometry from which key developments grew that were at the time unimaginable, and continue to surprise us in its simplistic preeminence. We, and others, have demonstrated exceptional analytical utility. Our current research is focused on how best to understand, improve, and use these novel ionization processes through dedicated platforms and source developments. These ionization processes convert volatile and nonvolatile compounds from solid or liquid matrixes into gas-phase ions for analysis by mass spectrometry using e.g., mass-selected fragmentation and ion mobility spectrometry to provide accurate, and sometimes improved mass and drift time resolution. The combination of research and discoveries demonstrated multiple advantages of the new ionization processes and established the basis of the successes that lead to the Biemann Medal and this Perspective. How the new ionization processes relate to traditional ionization is also presented, as well as how these technologies can be utilized in tandem through instrument modification and implementation to increase coverage of complex materials through complementary strengths.

Introduction

The accumulation of discoveries, developments, and implementations of new ionization processes for use in biological MS was honored with the Biemann Medal to Prof. Sarah Trimpin by The American Society for Mass Spectrometry (ASMS). Together with collaborators from academia, government, and industry, key limitations of materials characterization have been identified for which current analytical technology are insufficient. Material characterization is an essential component of materials developments, clinical precision and timeliness, and safety, and, consequently, commercialization. The objective of our work is, inter alia, to improve the utility through simplicity, speed, and sensitivity of the new ionization processes in mass spectrometry (MS), with some emphasis on vacuum matrix-assisted ionization (vMAI),1,2 in order to broaden the scope of materials for which molecular surface and chemical defect analyses can be applied. Recent summaries include research on fundamentals and applications and, in some cases, are supported by movies showcasing the operation of different methods.3–9 In this Perspective we present work delivered in the Biemann lecture10 and other ASMS presentations from us and other researchers to demonstrate scientific and broader societal impact. We first start with the current state-of-the-art of the new technologies. Subsequently, we include a synopsis of discoveries going from the solvent-free and voltage-free experiments to the dedicated sources presenting vMAI as the newest, simplest, and a robust alternative within these new ionization processes, as well as the lessons learned toward taking informed steps through hypothesis-driven fundamental research questions guiding and enabling the discoveries to advance the new technologies and applications. To assist the reader, Scheme 1 summarizes the path of the discoveries and inventions, how they are interconnected fundamentally and how they have been used by us and others, as well as the homebuilt modifications to commercially available manual and automated platforms (inlet ionization) and sources (vacuum ionization). The discoveries led to 11 issued patents and two additional patents at various stages of intellectual protection. In the interest of the academic character of the Biemann Special Issue and perceived conflict of interest, we refrain from referring to any of the patents that resulted from this research.

Scheme 1. Timeline for the Path of Discoveries of New Ionization Processes Developed into Ionization Methods with Applicability Ranging from Imaging to Liquid Chromatography and Spanning Pressure Regimes from Above Atmospheric Pressure (AP) to Low Pressure (High Vacuum).a.

a Inlet ionization (in red color) is referred to when the ionization is assisted by an inlet tube, preferably heated, that connects a higher pressure with a lower pressure region by default available with AP ionization mass spectrometers. Depending on the vendor, mass spectrometer specific ion source configurations can be used “as is” or with inlet modifications. In MAI, a laser is not used to initiate ionization of the matrix:analyte sample. An inlet tube is also used with SAI, but the matrix is a liquid, typically the solvent used to dissolve the analyte. Vacuum ionization (in blue) is referred to when the matrix:analyte is introduced directly into the sub-AP of the mass spectrometer, typically on a substrate without use of an inlet tube. vLSI proved that a heated inlet tube was not necessary; instead, multiply charged ions are obtained from a thermal process assisted by the laser. Without the use of a laser, using the matrix 3-nitrobenzonitrile (3-NBN) under vacuum (vMAI) conditions, the matrix:analyte sample produces ESI-like charge states. Using vMAI, the changes in the instrument can be as minimal as with inlet ionization, or substantial, by replacing the source and inlet to the mass spectrometer. The purple color combines substantially the aspects of inlet and vacuum ionization. MSTM products include manual and automated Ionique platforms and sources developed through the National Science Foundation (NSF) STTR and SBIR funding.

Experimental

Details are included in the SI of this contribution.

Results

1. State-of-the-Art Technologies for Fast, Sensitive, and Robust Analyses Without Mass Spectrometry Expertise

We start this Perspective at the current state of development and then describe the important progression from its inception, bringing us full circle from the first observation of vMAI spontaneously producing gas-phase ions simply by exposing the matrix:analyte sample to the vacuum of the mass spectrometer. Briefly, this was accomplished on Waters SYNAPT G2 intermediate pressure matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization (MALDI) sources using the vMAI matrix 3-nitrobenzonitrile (3-NBN) and required 2 minutes to insert the sample into vacuum and positioned in front of the ion transfer region. Because 3-NBN sublimes, especially when exposed to vacuum conditions, we needed a faster means of delivering the sample. This was accomplished in the Trimpin academic laboratory at Wayne State University (WSU) with a probe inserted through a ball valve providing ca. 10-second introduction.11 The results, as described below, were so enticing that MSTM, a university spin-off company between WSU and the University of the Sciences, founded to commercialize the new ionization technologies, built a probe device to test on a Thermo Orbitrap mass spectrometer.12 The results, especially from the second-generation probe device were astonishing in sensitivity, robustness to carryover and instrument contamination as described in more detail later on. While the Trimpin group focused on fundamentals of the ionization process and discovery of new matrixes which had been too volatile to survive the time constraints of the vacuum (v)MALDI source introduction (described later), MSTM focused on achieving automated high throughput, while maintaining the advantages of a vacuum-probe.11,12 In order to give the reader a feel for the analytical power of the new ionization technologies described herein, we begin with the developments relative to high throughput vMAI.

The performance of the manual vacuum-probe on the Q-Exactive Focus12 convinced MSTM to develop a high throughput vMAI source using a novel sample introduction approach. The success of the probe sources,11,12 even though limited to single samples, inspired a new plate source (Figure 1) concept for sample introduction to vacuum with the potential for sensitive, robust, and high throughput analysis using vMAI. In spite of the promise of the plate source concept, the version shown in Figure 1 was limited in that great care had to be exercised to prevent venting the instrument, cross contamination and carryover, and additionally, reproducibility was generally poor, and the limitation to alternating two samples. However, the approach was promising, and because this vMAI concept, in theory, can be applied to any atmospheric pressure ionization (API) mass spectrometer (vendor neutral) providing capabilities of high mass resolution, accurate mass measurement, MS/MS, and ion mobility spectrometry (IMS)-MS technology for structural characterization studies, MSTM applied for and was awarded NSF SBIR Phase I grant. The roadblocks were successfully addressed during the NSF SBIR Phase I award period (Figure 2).

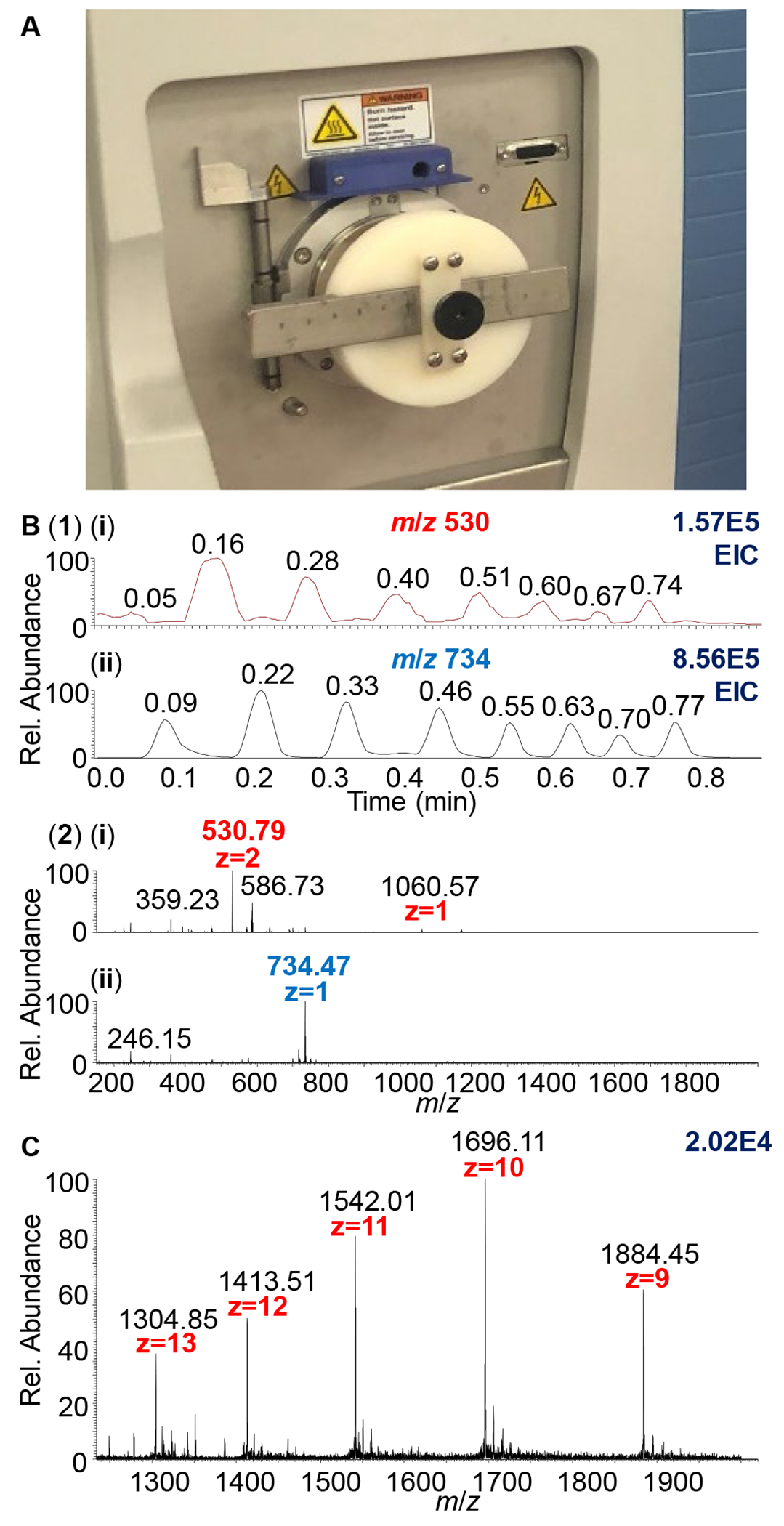

Figure 1.

Sampling by vMAI-MS directly from AP into sub-AP of the mass spectrometer. (A) Photograph of the source setup using plate introduction in which each matrix:analyte sample is exposed to the sub-AP in successions; (B1) Chronograms displaying 2 samples acquired in less than 4 s per sample and (B2) mass spectra of the two compounds: (i) bradykinin and (ii) azithromycin. (C) Mass spectrum of the multiply charged ions of myoglobin, molecular weight ~ 16.9 kDa.

Figure 2.

(A) MSTM vMAI/vMALDI prototype manual rapid analysis vacuum source; (1) valve plate, (2) sample plate (glass slide required for TG vMALDI), (3) spacer plate with channels therethrough, (4) channel positions where samples applied to sample plate align, (5) laser beam (represented by pointed blue arrow) aligned with channel in flange (not shown) to vacuum for TG vMALDI. Ionization in vMAI occurs when a spacer plate channel aligned with a vMAI sample aligns with the flange channel and thus exposed to vacuum. Multisample plates are exchanged in ca. 2 sec. (B) vMAI mass spectrum of 2 picomoles of ubiquitin in detergent using 3-NBN as matrix applied to a glass slide. Instrument Q-Exactive Focus. Movie-S01 is included to demonstrate the acquisition of myoglobin in detergent using the plate vMAI/vMALDI source.

A number of modifications were made to address issues of inconsistency, carryover, and ease of instrument venting. Two important findings were (1) airflow used to influence the rate of ionization and sweep ions, charged clusters, and clusters toward the mass analyzer was inconsistent and chiefly responsible for inconsistent results, and (2) incorporation of a spacer plate between the sample and entrance to the vacuum of the mass analyzer essentially eliminated carryover and instrument contamination. The successful development and implementation of the plate source concept (Figure 2A) has allowed vMAI analysis speeds of 4 sec/sample including the time required to load samples using 8-well sample plates.13 Future applications of the plate source may be enhanced by the finding that almost all compounds which sublime at an appreciable rate when placed in sub-atmospheric pressure (sub-AP) conditions produce gas-phase ions opening the potential for selective ionization.14 Two contributions in this Biemann Special issue provide detailed information toward innovative instrumentation, new measurement capabilities, and fundamentals that can be now studied.13,14

Although a laser adds complexity and costs, MSTM later expanded the plate vacuum ionization source to include vMALDI (Figure 2A).13 The new plate vacuum ionization source with the two modes of operation (vMAI/vMALDI) operates directly from AP while only the sample being ionized is at the vacuum of the first vacuum stage of the mass spectrometer. The combined vMAI and vMALDI plate source gives either singly (vMALDI) or multiply charged (vMAI) ions with the same mass spectrometer and no waiting time for the sample to be introduced to vacuum through a vacuum lock. Samples can be loaded on a glass slide and affixed to a spacer plate with channels therethrough so that each sample fits within a channel. This sample plate assembly (sample and spacer plates) can displace another sample assembly plate, or a valve plate, by sliding over the flat flange face. Samples are sequentially be exposed to vacuum when the channel it resides within is over the opening in the mass spectrometer inlet flange. The spacer plate eliminates cross contamination caused by samples in wells of the sample plate having direct contact with the flange surface. A key concept is that the sample plate assembly remains at atmospheric pressure (AP) while samples isolated by the spacer plate channels are individually exposed to vacuum. Spacer plates can be rapidly replaced without venting the instrument if contaminated, which is not possible if the flange surface were to become contaminated.

The plate multi-mode vacuum ionization source of vMAI and vMALDI uses a flange component that is rather simple in concept as it consists of the flange having a flat surface with an opening (ca. ¼”) to the instrument vacuum. Details are included in ref. 13. Vacuum is maintained by having flat plates slide over the flat flange surface. Ionization commences with vMAI when a matrix:analyte sample experiences vacuum and with vMALDI when the matrix:analyte sample in vacuum is ablated by the laser beam. With vMALDI, analysis speeds of one sample per second with full mass range acquisitions have been achieved.13,15 In an interesting example of the complementary nature of the two ionization methods, polyethylene glycol (PEG)-2000 and ubiquitin were mixed and applied on adjacent positions on a glass slide, one sample using 2,5-dihydroxyacetophenone (2,5-DHAP) as matrix, and the other 3-NBN.13 A nitrogen laser was used to ablate the 2,5-DHAP prepared sample (vMALDI), and the 3-NBN sample spontaneously produced gas-phase ions when exposed to sub-AP (vMAI). With 3-NBN, multiply charged ions of ubiquitin were observed, but no PEG ions, and with 2,5-DHAP, singly charged ions of the PEG sample were observed but no ions from ubiquitin, possibly because with MALDI, they are out of the instruments’ mass range. The acquisitions were obtained just a few seconds apart. This new vMAI plate source was also used to investigate the applicability of analyzing e.g., proteins in the presence of detergents in collaboration with Dr. Vladislav Lobodin (BASF Corporation). Highly charged ubiquitin ions (Figure 2B) and even out of a variety of different detergents, without dilution, were ionized in a straightforward manner. Movie S-01 shows ubiquitin in detergent solution, acquired in overall just under 10 seconds, is included to visualize this point, as it is nothing short of astonishing! Future applications of the plate source may be enhanced by the finding that almost all compounds which sublime when placed in sub-AP conditions produce gas-phase ions. At present, the ions observed from most subliming matrices, at least when no analyte is present, are unknown, but this may suggest the potential for finding matrices for selective ionization.14 Two contributions in this Biemann Special issue provide detailed information toward innovative instrumentation, new measurement capabilities, and fundamentals that can be now studied.13,14

MSTM’s current aim is to build an ultimately simple, highly robust, high throughput, automated source based on vMAI and vMALDI capitalizing on high speed complementary analyses. Meanwhile, work in progress in the Trimpin group (Figure S1) is to implement the vacuum source to optionally include vMAI, vMALDI, and vacuum laserspray ionization (vLSI), including laser alignments both in transmission geometry (TG), and reflection geometry (RG) (the default laser configuration with commercial instruments), based on the plate source concept while offering inlet ionization and ESI capabilities. This next generation multi-mode ionization source, ideally available on any vendor’s mass spectrometers, has the potential to be transformative in how direct ionization is achieved with high speed, sensitivity, and robustness with the full scope of capabilities of state-of-the-art mass analyzers, including tandem mass analyzers, IMS interfaced with MS, and with collision induced dissociation (CID), electron transfer dissociation (ETD) and other fragmentation technologies. Such developments could not have been imagined just a few years ago. In the next sections are described how we systematically developed the new technologies based on the new ionization processes.

Lesson 1:

A novel ion source makes vacuum ionization as simple to use as ambient ionization, but with unprecedented speed and robustness ref. 13

Multi-mode ionization sources are cost-effective and analytically exceptional in information coverage, as shown in more detail in ref. 13

Exciting new fundamental research can now be performed to decipher the basics associated with the new ionization processes because the same mass spectrometers can be used under well-functioning conditions for the specific method of interest. Initial progress is detailed in ref. 14

Chemical, clinical and biological applications for sensitive analyses can rapidly be achieved with new and established ionization methods

2. Implementation of Imaging MS using Transmission Geometry Laser Ablation and Unexpected Observation of Multiply Charged Ions

Our research broadly relates to developing technology for molecular characterization of surfaces to provide spatially resolved chemical information of biological and synthetic materials using MS. While surface chemistry is economically extremely important, molecular methods of surface characterization, including the molecular structures of organic and inorganic compounds in surface layers, healthy versus diseased tissue, etc. lag behind materials characterization in solution. Lack of methods with high mass and spatial resolution, as well as sensitivity capable of characterizing complex surfaces and surface reactions are limiting developments in surface characterization, clinical chemistry, and ultra-fast analyses, as examples.

Looking back, the start of the exciting ionization inventions was a relatively trivial idea to improve tissue imaging.16,17 The hypothesis was that high resolution and fast imaging MS directly from AP could be improved using TG-MALDI. Solvent-free sample preparation was used to minimize alteration to the tissue and maximize the chemical information as well as minimize the time of analysis to better study and understand complex organs such as brain function, in collaboration with Michael Walker (Indiana University, Psychology and Brain Sciences), and precise and human error independent assessment of cancer boundaries. TG using LD and MALDI had been performed previously at vacuum and AP.18,19 A “field-free TG-AP-MALDI” proposal by Trimpin eliminated the voltages applied to extract the ions to overcome so-called “rim losses”20,21 as well as offering simplicity to the set-up and experimental execution (Figure S2).16,17 Unlike previous TG-MALDI results, initial voltage-free experiments produced reasonably abundant analyte ions almost immediately from small molecules such as drugs and lipids using the MALDI matrix 2,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid (2,5-DHB).16,17 Elimination of voltage was achieved by placing the point of ion production close (1-5 mm) to the inlet of the mass spectrometer in which the ablated material is flow entrapped into the sub-AP of the mass spectrometer vacuum through the restricted inlet. Unexpectedly for a MALDI-like setup, multiply charged ions of peptides and even proteins were obtained.16,22–25 Only in the presence of high voltages were singly charged ions observed, additionally to the multiply charged peptide ions (Figure S3). Dr. John Callahan (Navel Research Labs) and collaborators used voltage with AP-MALDI and observed only singly charged ions, as expected.19 In our experiments, undesired metal cation and matrix attachments to the singly charged ions, and an increase in chemical background, were observed using higher voltages (Figure S3). The use of solvent-free matrix preparation led to ease in sample preparation and potential improvements in imaging experiments16,17 but also the observation of only singly charged ions.22 This was the first indication of the importance of the solvent, especially the protic solution component, and possibly many other ionization processes relative to the formation of multiply charged ions.

The implementation of MS imaging was a success26–28 for singly and even for the surprising case of multiply charged ions using Thermo mass spectrometers.29 Fast single-shot-one-mass spectrum output16,17 along with multiply charged ions22,23 nearly identical to electrospray ionization (ESI) from a MALDI-like experiment were initially observed using the MALDI matrix, 2,5-DHB, and a ~250 °C Thermo inlet tube. Spatial resolution of ca. 20 μm was achieved.3,17,26,27,30 In brief, an automated X,Y,Z-stage was used to manipulate tissue sections3,28,29 on a glass slide relative to the inlet aperture of the mass spectrometer and laser beam to obtain a series of mass spectra from which an image can be constructed for any mass-to-charge (m/z) value. Different sizes (including lengths, diameters, and shapes) and materials (various metals and glass) inlet apertures, commercial or homebuilt, were studied relative to ion abundance in collaboration with Drs. Jeff Brown (Waters), David Clemmer (Indiana University), Donald Hunt (University of Virginia), Barbara Larsen (DuPont), Alexander Makarov (Thermo), Alan Marshall (Florida State University), Charles McEwen (University of the Sciences, now Saint Joseph’s University, SJU), Paul Stemmer (WSU Institute of Environmental Health Sciences), Steffen Weidner (Bundesanstalt für Materialforschung und –prüfung, BAM, Germany). Even a 1-m long extended stainless steel inlet tube provided gaseous ions of the analytes.4 The quality of imaging results, and the spatial resolution, are typically limited by sensitivity. An increase in sensitivity is known to be associated with vacuum MALDI,31,32 although the ionization efficiency of MALDI is substantially lower than with ESI.33,34

Initial fundamental research with a laser on an API mass spectrometer demonstrated the importance of inlet temperature,22,23,35,36 as well as collisions with surfaces such as gases and obstructions in the production of ions,36–40 and subsequently to the term “laser (as in MALDI) spray (as in ESI) ionization” or LSI.23 Because of the production of multiply charged ions originating from a solid surface, both CID and ETD from mass-selected gaseous analyte ions were demonstrated.23,30,40,41 As one example, multiply charged myelin basic protein (MBP) peptide ions from mouse brain tissue were gas-phase sequenced for the first time by a LSI-ETD approach.30

Lesson 2:

Fast imaging from AP with good spatial resolution using MS was achieved, but this outcome while useful is not transformative

The breakthrough was that ESI-like ions are observed from MALDI-like experiments

The mechanism is an important unknown

“If at first the idea is not absurd, then there is no hope for it.” Albert Einstein42

3. Discovery of a New ‘Ion Source’: The Heated Inlet Tube

Mass spectrometers and IMS-MS instruments that operate without a heated inlet tube were initially difficult to use with the new ionization processes providing only poor analyte ion abundance, even with retrofitted homebuilt inlet tubes.24–26,28,38,40,43–46 An improvement in the ion abundance was accomplished using a 90° bent inlet tube, possibly forcing the material to collide with the surface,43 however, the restricted airflow prohibited long term use for, e.g., imaging applications (Figure S4). Key factors in obtaining analytically useful results early on were a heated inlet tube, collisions (Figure S5), and the matrix used.23–30,35–40,43–47 For example, using the MALDI matrix 2,5-DHB, and especially with the less volatile α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid (CHCA)48 and sinapinic acid (SA) matrixes, a matrix dependent inlet tube temperature between 200 and >400 °C was necessary to initiate efficient ionization.40,45 Switching from 2,5-DHB,22,23,43 a MALDI matrix,49 to the more volatile 2,5-DHAP, also a MALDI matrix50 (Scheme S1), allowed ionization with lower inlet tube temperature including observation of ESI-like multiply charged ions.51 Nevertheless, reliable ion formation, especially for imaging applications, remained a difficult task on certain mass spectrometers equipped with skimmer cone inlets, even with the 2,5-DHAP matrix.44

At the time, we assumed the laser was responsible for the ionization,35 and thus a number of experiments did not make sense. The undergraduate student, Christopher Lietz (WSU), for example, reported that when he accidentally touched the inlet tube with the matrix:analyte applied to a glass plate, better analyte ion abundance was obtained as compared to using solely the laser. The graduate student, Beixi Wang (WSU), accumulated results with a neodymium-doped yttrium aluminium garnet (Nd:YAG) laser provided by Dr. Arthur Suits (WSU). The laser used at 1064 nm, did not work well with the known MALDI conditions e.g., glycerol, but when she used 2,5-DHAP (Figure S6) matrix instead, which absorbs in the ultraviolet (UV), significantly better results were obtained. Essentially the same ion abundance, charge states, and drift times were observed at 1064, 532, and 355 nm using the same UV matrix with standards and mouse brain tissues provided by Dr. Ken Mackie’s laboratory (Indiana University, Psychology and Brain Sciences).40,47

Directly after a conversation between Trimpin and McEwen discussing these and other seemingly “odd” results from the McEwen lab, such as the ionization continuing after the laser was off, it seemed that the laser may not be responsible for ionization to occur. McEwen then went to his laboratory and tapped a glass plate, with the matrix 2,5-DHB and a peptide analyte sample applied, against the heated inlet tube of a Thermo Exactive mass spectrometer without the use of a laser. He immediately called back with the news that the laser was, in fact, not necessary. A flurry of experiments were initiated by both laboratories to introduce the analyte in a variety of new ways to the inlet of the mass spectrometer (through space by vibrations, acoustic, a punch device, as well as directly by tapping, etc.)10,52–54 and to better define mechanistic aspects, some of which have been covered in previous papers.3–9,40,55–58 In one example, the graduate student, Vincent Pagnotti (SJU), substituted the laser and glass microscope slide with a ‘BB gun’ and metal sample plate as a visual demonstration that almost identical mass spectra were obtained by either the BB or laser approaches.52,55 The successful outcome of forming highly abundant multiply charged analyte ions, unequivocally demonstrated that the laser wavelength has no influence on the experimental results other than delivering the matrix:analyte sample into the inlet tube of the mass spectrometer, and thus, explaining the previously “odd” results. Other examples of experiments to better define this new ionization method include gas pressure (above and below AP) and gas type (Figure S7) with and without the laser, in the positive and negative modes as a means to improve the experimental outcome.38,40,45 These experiments in sum proved successful in increasing the analyte ion abundance, but none provided the desired breakthrough for analytical utility with mass spectrometers not already equipped with a heated inlet tube ‘source’.40,43–46 Consequently, a heated inlet tube used with some API mass spectrometers is an effective ion source, but the path forward,24–27,41,53–59 has not always been straightforward. It was our understanding at that time that mass spectrometers with skimmer cone inlets were not as analytically useful using inlet ionization as mass spectrometers with heated inlet tubes.

The evolvement of the TG alignment for being possibly associated or responsible for the unusual observations of multiply charged ions was eliminated by using a MassTech AP-MALDI source in collaboration with Larsen, which uses the laser alignment in RG.51 Other experimental designs were tested to improve our understanding and the utility of the formation of multiply charged ions directly from surfaces. In 2013 McEwen’s group demonstrated the use of LSI to simultaneously image lipids, peptides, small proteins and drugs.60 The same year Dr. Rainer Cramer (University of Reading, UK) and Dr. Klaus Dreisewerd (University of Münster, Germany) reported the use of liquid matrixes for AP-MALDI using a heated ion transfer tube on a AB SCIEX Q-Star Pulsar instrument and obtaining multiply charged ions of peptides and proteins.61 In 2018, a miniature ion trap mass spectrometer was coupled with LSI by Dr. Wei Xu’s group (Beijing Institute of Technology) for the direct detection of peptides, proteins, and drugs in complex samples such as blood and urine, and lipids from tissues.62 The same group, then adapted this setup to a 2-dimensional (2D) moving platform for high throughput analysis. Drugs, vitamin B, and peptides were analyzed in diluted blood demonstrating a speed of 10 seconds per sample.63 Direct bacterial analysis was demonstrated with this system; 21 bacteria were differentiated at both the genus and species classification utilizing orthogonal partial least squares (OPLS).64

Lesson 3:

Confirmation that the laser is not responsible for analyte ionization (therefore not “MALDI” but MAI)

LSI is MAI with use of a laser to transfer matrix:analyte into the ionization region with high spatial resolution

Confirmation that gas flow, collisions, and heat matter

The research goal is to make LSI and MAI analytically useful and mass spectrometer vendor independent

4. Expanding our Fundamental Knowledge of the New Ionization Processes Leading to Unique New Ionization Methods With and Without a Laser from Solids and Liquids

Studies that form key pillars in the path of these innovative technology developments were made essentially at the same time. Both developments grew, at least in part, out of the success of the more volatile matrix 2,5-DHAP, relative to 2,5-DHB (for more detailed information about matrixes see Scheme S1), that gave good results on the AP-MALDI source used under LSI conditions.51 First, we describe developments of vLSI in Trimpin’s laboratory,65 and second, solvent-assisted ionization (SAI) in McEwen’s laboratory,56 and from each, we briefly expand on some of the current uses and further developments by the community.

Using the commercial intermediate pressure (vacuum) MALDI source of a Waters SYNAPT G2 mass spectrometer and 2,5-DHAP as matrix gave exceptionally clean and highly abundant multiply charged ions upon laser ablation.40,65–67 Hence, no inlet tube is necessary when using the ‘right’ matrix in what again seems like a MALDI experiment. Because of the formation of multiply charged ions, the mass range is extended and because of the fundamentals that were already established from AP, we used the term vLSI.65 Our hypothesis is that an important difference between LSI and MALDI in forming ESI-like multiply charged ions is the volatility of the matrix. This was shown by us, and others.40,51–54,58,68–70 During these studies an even better performing matrix, 2-nitrophloroglucinol (2-NPG), was discovered66 and successfully used for the first imaging applications of several multiply charged MBP peptide ions from a mouse brain tissue using an intermediate pressure MALDI source and the laser in RG alignment.71 The applied laser fluences and voltages were kept low to increase the relative ion abundance of the multiply charged ions.40,45,51,65,68,71 Because of the relatively high volatility of 2-NPG, but the good ion abundance of multiply charged ions, we decided to use a mixture of matrixes, adding 90% of 2,5-DHAP and 10% of 2-NPG, thereby reducing the volatility of the matrix composition and allowing molecular imaging of tissue samples that intrinsically require longer acquisition times.71 IMS-MS was fundamental to enhance the separation of lipids, peptides, and proteins directly from the tissue.65,67,71 These results were encouraging, but still with the limitation of the unintentional matrix sublimation of 2-NPG in a vacuum source.

We, and others, have shown the utility of the new ionization processes for surface analyses and imaging in the positive and negative mode, in RG and TG modes, and from AP and intermediate pressure for lipids, polymers, peptides, and small proteins. As an example, using vLSI, we developed methods to detect and image gadolinium-containing complexes synthesized in the laboratory of our collaborator, Dr. Matthew Allen (WSU). These complexes are developed for potential use as contrast agents for magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).72,73 Traditional MALDI-time of flight (TOF) mass spectrometers were limited in analyzing these compounds. Using the commercial intermediate pressure MALDI-SYNAPT G2 with MALDI matrixes either failed, or produced significant background, fragment ions, and less resolved ions as compared to the 2-NPG matrix in terms of mass resolution (e.g., MALDI 25,312 and LSI 35,711, Figure S8), stressing the importance and broader applicability of 2-NPG as a new matrix. A variety of complexes with different side chain functionalities were analyzed. In some cases, gadolinium complexes associated with matrix ions. The interpretation of the formation of an ion consisting of matrix adduction to analyte was verified by MS/MS (Figure S9). It is hypothesized that the nitro group of the matrix interacts as an additional ligand to the metal center.74 Further studies will be required to understand the fundamentals as it may reveal important mechanistic information of the synthesized structures as well as the ionization mechanism using this and other matrixes in MS.

Using an MS imaging approach, we analyzed mouse brain tissue sections in which a synthesized gadolinium(II) texaphyrin was applied to the tissue surface after sacrificing the animal. According to previous studies in which a multiple imaging approaches were used to visualize the location where the compound resides/accumulates.75 The 2-NPG/2,5-DHAP binary matrix was spray-coated71 onto the tissue section and the image acquired using laserspray conditions. The obtained MS images reflect the isotopic distribution of gadolinium with m/z’s ranging from 917 to 925 (Figure S10) by both the relative ion abundances of the isotopic distributions and the ion intensities of the images. This is contrary to e.g., the typical lipids composition, in a similar m/z range. This relationship between isotopic versus image intensities serve as additional verification that this is indeed the synthesized gadolinium-containing product signal without the necessity of performing MS/MS for confirmation. No other gadolinium-containing isotopic distributions were obvious suggesting initial biological stability of the potential MRI contrast agent in biological applications. The location of this chemical within the mouse brain tissue section matched well with that of the myelin areas of the brain obtained using other imaging approaches.75

The matrix 2-NPG is, to date, one of the most valuable vacuum ionization matrixes in conjunction with the use of a laser. With this matrix, high vacuum MALDI-TOF mass spectrometers were used to ionize and detect the highest charge states so far reported under high vacuum conditions, and even in the reflectron detection mode.45,58,66,68 Such results were highly sought after since the 1990s.76–78 In 2014, Dr. Lingjun Li’s group (University of Wisconsin-Madison) reported on the use of LSI using 2-NPG on an LTQ-Orbitrap XL mass spectrometer with an intermediate pressure MALDI source and CID as well as high-energy collision dissociation (HCD) for in-situ protein identification, visualization and characterization.79 The 2-NPG matrix reinforced our hypothesis that multiply charged ions require more volatile matrixes being capable of rapidly subliming or evaporating from multiply charged gas-phase matrix particles containing analyte as discussed in a 2012 mechanism paper.40

The need for volatility to obtain multiply charged ions and the need for stability for long imaging experiments are counter to each other. Binary matrix combinations have somewhat been able to improve the stability without interfering too much with abundances of multiply charged ions. However, the key to successful imaging with more volatile matrixes is to align the laser in TG for shortening the overall acquisition time (single-shot-one-mass spectrum to give a pixel). Initial imaging successes have been reported by several groups using 2,5-DHAP and 2-NPG, respectively, with vacuum MALDI instruments (Orbitrap; TOF).79–81 As examples, Dr. Richard Caprioli’s group (Vanderbilt University) demonstrated the utility of the use of TG-MALDI and 2,5-DHAP matrix achieving protein images with 1 μm resolution.82 Dr. Kermit Murray’s group (Louisiana State University) included the use of two component matrix using 2-NPG and silica nanoparticles, producing multiply charged ions from tissue on a high vacuum MALDI-TOF.83 In a more recent study by Dr. Jeongkwon Kim’s group (Chungnam National University),84 2-NPG compared with other MALDI matrixes, demonstrated the ability to generate multiply charged ions of proteins such as bovine serum albumin (BSA +4 charge states) and immunoglobulin G (IgG +6 charge states). The addition of hydrochloric acid (HCl) enhanced the absolute protein peak intensities producing more abundant charge states,84 as previously reported for new matrixes in MS.40,45,59,85 In the IgG study using linear detection mode, the typical wide unresolved molecular ion peaks (width ca. 10000 in m/z) associated with metastable ions and matrix and metal cation adductions, typical for a MALDI process,86–89 were observed. In contrast, intact protein ions, e.g. BSA, were also detected highly charged (+14) in the reflectron mode, and the peak width (+9 charge state) had a more analytically useful signal width of ca. 600 in m/z.68 The success is attributed to the softness associated with these new matrixes leading to intact and not metastable molecular ions or fragment ions typically observed with MALDI. MALDI is therefore a harder ionization method than LSI. These matrices, especially those without hydroxyl functionalities, show a general trend of not attaching matrix and metal cations.1,10,14,29,40,45,66,68,71,90

Another key pillar was the discovery of SAI in McEwen’s laboratory.56 Vincent Pagnotti employed solvents used to dissolve analyte(s) as the matrix. Considering how often ESI is used in conjunction with a heated inlet tube, it is amazing this was the first reported example in which a solvent was introduced into an inlet tube to a mass spectrometer, preferably heated, to cause ionization of the analyte contained in the solvent without application of voltage (as in ESI91) or high gas flow (as in sonic spray92).52,56,93 In retrospect, this is a variation of MAI, in that a matrix is used but is in the form of a solvent instead of a solid phase compound. In an early example, the solvent with the sample was introduced using a silica capillary into the inlet tube showing ESI-like multiply charged ions.52,53,56,93–97 It has been shown that it is unnecessary to have e.g., a fused silica tube “inside” of the inlet tube (the source). Flush or “through space” configurations of sample delivery is sufficient, although typically less sensitive.59 There is also no need to add a solid or liquid matrix as was shown by ionizing small and large molecules “neat”.40 Adding matrix, however, greatly increases the sensitivity of the experiment. A variety of methods to introduce the samples follow, and a few are summarized with photos (Figure S4 and S11) including, e.g., lasers and liquid junctions.3,4,7,9,46,52,53,94,96 Coupling SAI to liquid chromatography (LC)/MS was demonstrated, separating and ionizing components from a tryptic digestion of BSA, as well as analysis of steroids with improved sensitivity relative to ESI.94–100 High (ca. 100 μL) to low (ca. 0.2 μL) flow rates were shown to be applicable.52,56,95,98–104 An alternative to voltage-free SAI is application of voltage to the solution being introduced into to the heated inlet tube through fused silica tubing. The sensitivity and breadth of compounds ionized/analyzed was improved relative to SAI or ESI by the voltage (V)SAI method.52,93,95,101–104 VSAI (or ESII) appears to operate through both the SAI and ESI mechanisms.102 Surface analysis without the need of a matrix was demonstrated by capturing material laser ablated from a surface in a solvent flowing directly into a heated inlet tube. The laser provides spatial resolution and without addition of a matrix, solid or solvent, directly to, e.g., a tissue surface, maintaining the spatial location of compounds;3,9,94,103 Dr. Shubhashis Chakrabarty (USDA Bioscience Research Center) in this Biemann Special Issue reported on the use of electrospray ionization inlet, termed VSAI in this perspective, for the quantitative analysis of veterinary drugs (LOQ for zilpaterol, 100 pg/g) and PFOS/PFHxS (LOQ 0.4 – 50 ng/mL) in animal tissue and fluids without chromatographic separation using MS/MS. The quantitative results for LC/ESI-MS and ESII-MS/MS for the drugs ranged from 0.993 – 0.999 for the tested tissues and urine.104

An automated X,Y,Z-stage was used not only in imaging tissue sections,3,28,29 but also, e.g., in the automated analysis of well plates using the SAI approach.59,94 A motion-controlled arm was used to sequentially move an array of pipet tips containing the respective samples which were obtained from a well plate just prior to MS analysis. This approach readily detected the different sample solutions, and their relative concentrations were displayed using an ion intensity map (image of an m/z value of interest in a targeted or nontargeted approach). The gas flow and sub-AP draws the liquid from the pipet tips into the inlet through space. This mist typically leads to ‘splashing’ and therefore undesired deposition on the outside of the inlet leading to carryover, unless, e.g., the use of pipet tips containing wash solvent are applied between acquisitions.

The use of solvents as matrixes is the basis of ESI and SAI. Solvents expand the range of matrixes available to inlet ionization. McEwen’s laboratory early on demonstrated a variety of unique introduction methods e.g., the eye of a sewing needle was used to sample an analyte solution,52,53 as is demonstrated using the liquid matrix glycerol without voltages or a laser on an LTQ Velos with an inlet tube at relatively high temperature (Figure S12A and Table S1). Likely the easiest manner to ionize single samples has been use of pipet tips, as is shown for the date rape drug gamma-hydroxybutyric acid (GHB) in collaboration with Samantha Leach (Department of Forensic Sciences, Washington, DC). Data was acquired in the negative mode on an LTQ Velos at 50 °C inlet temperature using the solution as supplied (Figure S12B). In most of the cases, though not surprising, the diverse variations of SAI have been accomplished using Thermo mass spectrometers that are already equipped with a heated inlet tube. At the ASMS Conference in 2011, McEwen’s group introduced a liquid bridge SAI-surface sampling methods to analyze two and three-dimensional objects using a flow of solvent delivered to a sample under ambient conditions and then introducing the solvent/sample directly to the mass spectrometer inlet (Figure S13).52,53 The following year at ASMS, Wang presented this concept analyzing a drug-treated mouse brain tissue using continuous and discontinuous (discreet) flow.94,105 An improved system using the manual Ionique platform, a syringe pump, and a gutted ballpoint pen was presented by our group in collaboration with MSTM in Trimpin’s ASMS talk from 2016 (Figure 3).106 The pen, constructed by Sara Madarshahian (SJU), held two fused silica capillaries together so that one delivered solvent and the other transferred the solvent to the inlet of the mass spectrometer where ionization occurs. Simply touching a surface of a sample (e.g., tissue) and then collecting dissolved compounds using a liquid junction approach,9 or by sequential transfer of defined extraction droplets to the inlet of the mass spectrometer allowed surface analysis of extracted compounds,3,9,106 similar to earlier work, just more stable and therefore easier and effective. For instruments without a heated inlet tube, it was effective to construct an inlet tube to ionize nonvolatile compounds even from 100% aqueous solution.37,46,52,53,56,59,93,94,98,101 Eventually we learned to analyze samples by SAI on Waters mass spectrometers, e.g., a Waters SYNAPT and Xevo mass spectrometers.7,9,46,93,98,95,107,108 Inlet tubes (not extensions) varied in length from ca. 1 mm to over 1 m with materials ranging from stainless steel, copper, and glass.3,4,9,41,43,93,98,107,109 In one example, a homebuilt heated inlet capillary (3” x 20 gauge) coupled to a Waters Xevo-TQ-S was used, and with this modification peptides and proteins were acquired,9 and with high ion abundance for 50 fmol of lysozyme using 0.1% formic acid (charge states +7 to +9) and 1% proprionic acid, (charge states +7 to +14), respectively (Figure S14). Addition of super-saturated gases into the sample solution,110 increased ion abundances. The addition of solid co-matrixes (e.g., 3-NBN) to the solvent matrix have been shown to lower the temperature requirements and, in turn, improve the quality of the mass spectral results. Likewise, volatile organic solvents reduce the inlet temperature required with SAI. McEwen’s group studied the softness of the new ionization processes relative to ESI on the same mass spectrometer; SAI was softer than ESI and MAI when the inlet tube was heated.94

Figure 3.

Analysis of surfaces with solvent-assisted ionization using the MSTM Pen. The mass spectrum shows in red the pesticide thiabendazole m/z 202.04; the highest abundance of the pesticide was found in the stem area of the apple. Inset: photograph of the setup: (1) manual MSTM platform with (2) fused silica capillary from the (3) MSTM Pen sampling of the (4) surface of an apple. Data were acquired on Thermo Orbitrap Exactive mass spectrometer. See a more detailed description of the MSTM Pen in Figure S1C inset, Movie-S04 and compare with Figure S13.

Different means to ionize and introduce liquid samples into the inlet of the mass spectrometer have been described by others. Interested in the chemistry in aerosol droplets in the atmosphere, Dr. Murray Johnston’s group (University of Delaware) demonstrated the influence of an inlet tube heated to 950 °C by customizing the inlet cone of a SYNAPT G2S.111 Their system uses an atomizer to generate droplets that later are introduced into the modified heated inlet tube where the ionization process occurs; this method is called droplet-assisted ionization inlet (DAII).111 Fundamental details were also provided.112 Another approach, a voltage-free ionization method presented by Drs. Stephen Valentine and Peng Li (West Virginia University), called “vibrating sharp-edge spray ionization” (VSSI), uses a piezoelectric transducer to generate an aerosol from the sample placed on a glass slide and placed close to the inlet tube of the mass spectrometer.113 The transducer is operated at low voltage input (12.7 to 30.6 V, peak to peak) and low power consumption (~150 mW) compared with other ultrasonic114 and surface nebulization methods.115 In the VSSI approach, the high-frequency vibration at the sharp-edge is proposed to cause the detachment of small liquid droplets from the bulk fluid, resulting in a continuous spray.113 This group optimized VSSI to be used as an interface to LC or other continuous flow-based applications by attaching a piece of fused silica capillary on the VSSI, called cVSSI,116 resulting in the ionization of metabolites, peptides, and proteins comparable with LC-ESI-MS. cVSSI was later improved to be a useful method for native MS in negative mode, delivering the liquid sample and providing a good signal with a minimal amount of sample at flow rates of 0.2 to 1 μL min−1.117 The group is working to elucidate the ionization mechanisms involved and obtain a direct comparison with ESI using water and methanol as solvents, as is described in this Biemann Special issue.118 The surface acoustic waves (SAW) processes have been used in the electronic industry119 and more recently have been adopted in MS.120–122 Kostiainen’s group (University of Helsinki) presented the ambient method solvent jet desorption capillary photoionization (DCPI) which combines two processes to analyze polar and non-polar compounds.123 A solvent jet is directed onto a sample surface, and the extracted ions are ejected and directed into a heated extended inlet tube on an Agilent 6330 ion trap mass spectrometer where photoionization by vacuum UV (VUV) photons takes place. Testing different molecular weight compounds, the group concluded that there are two ionization processes occurring, for small molecules via photoionization and for larger molecules ionization is by SAI.

Other groups are now working with inlet ionization methods for use as, e.g., surface analyses tools, specifically with the help of a heated inlet tube. The advantage of this approach is the easy manipulation of samples (liquid or solid) outside the mass spectrometer. One example with important clinical applications is the MasSpec Pen by Dr. Livia Eberlin’s group (The University of Texas at Austin).124,125 A liquid junction was used in combination with SAI to detect cancerous tissue on a Q-Exactive Hybrid Quadrupole-Orbitrap mass spectrometer. Using a stop flow of water to sample the surface of the tissue, then taking advantage of the pressure differential, the sample/solvent is drawn into the inlet tube of the mass spectrometer.124 A modified MasSpec Pen has been integrated into the da Vinci surgical system125 and is sold to Genio Technologies, Inc.126 Dr. Akira Motoyama’s laboratory (Shiseido Co., Ltd.) attributed the ionization mechanism of zero volt paper spray to SAI.127

The methods developed for introducing samples directly into the AP inlet aperture are attractive for their simplicity, but in practice, there could be issues of instrument contamination and carryover between successive samples, similar to other solvent-based API methods used in MS.

Lesson 4:

A matrix can be a solid or solvent or combinations

Volatility of the matrix is important, especially for producing multiply charged ions, even from vacuum

The new ionization processes allow truly different ion sources such as simply an inlet tube which can be extremely short or surprisingly long

SAI developments have seen the greatest expansion, but progress in MAI may change that

5. Fundamentally-Driven Arguments Leading to the Surprising Discovery of Ionization Seemingly Not Possible

In this section we first describe the discovery of the “unthinkable”, at the time, using intermediate pressure (vacuum ionization conditions) on an intermediate pressure MALDI source.1,2 The concept was later transferred to AP (inlet ionization) using an API source.128 We follow briefly with simplifications and showcase initial applications. These applied examples were critical in our path forward.

The discovery of LSI was based on considerations of ESI and MALDI mechanistic aspects because of similarities to both: one in terms of charge states (ESI), and the other, in terms of the matrix (MALDI). The use of a laser in TG without voltages gives good results, minimizing the background noise and providing little or no metal cation or matrix adductions, and working from AP decreases fragmentation. The problem-solving principle described by “Occam’s razor” or “law of parsimony” offers the insight that the right answer will be found if one pursues the path that “entities should not be multiplied without necessity”.129 In other words, limit your assumptions to a bare minimum. Following this guiding strategy, we looked at what is truly known about ESI and MALDI and used that to explain LSI, and, with subsequent inventions, MAI, and SAI with the least assumptions.40 An important difference between MALDI and ESI is the production of singly charged ions by MALDI which limits the analysis of larger molecules with most mass analyzers, versus ESI that provides multiply charged ions. Because we were observing ESI-like charge states with MALDI-like “tools”, the most straightforward explanation is that they are made from charged droplet (molten matrix) or particles and like ESI requires removal of the matrix, which in part was published in the Special Issue honoring John Fenn.35 The heated inlet tube and collisions with a surface would be means to aid desolvation of the charged gas-phase matrix particles. The use of collision surfaces or obstructions are well-known to enhance desolvation of charged droplets in ESI.130–135 We noted that higher melting and presumably less volatile matrixes required higher inlet temperature.35

Trimpin hypothesized that if some matrixes require high inlet tube temperature to produce ions (e.g., CHCA >300 °C) and others lower temperature (e.g., 2,5-DHAP <50 °C)3,4,8,10,40,45,51 that more volatile matrix compounds might further lower the temperature requirement (Scheme S1). This hypothesis guided us in pursuing studies on potential new solid matrixes with increased volatility, initially leading us to the discovery of vLSI (note, on the contrary, MALDI matrixes were optimized for decades for stability under vacuum). A screening study discovered new matrixes with improved analytical utility, expansion to different mass spectrometers, and importantly, to obtain a better understanding of the mechanism.

• Vacuum ionization conditions

Nearly at the end of this lengthy “matrix” study, in which it was found that most compounds when introduced into a hot enough inlet tube produce ions but few at a low inlet temperature, a backordered chemical was finally tested for its potential as a matrix for MAI on a Thermo LTQ Velos and vacuum LSI on a Waters SYNAPT G2. Trimpin and the graduate student, Ellen Inutan (WSU), discovered the pinnacle of the astonishing ionization processes. That is, with the matrix 3-NBN, analyte ions were observed in high abundance and multiply charged at room temperature without initiating the laser on an intermediate pressure MALDI source of a SYNAPT G2 (Figure S15)!1,2 Proteins were spontaneously converted to gas-phase ions and readily detected, from less than pmol amounts, from uncleaned samples (e.g., whole blood),136 and, astonishingly, even the BSA protein (66 kDa) produced mass spectra with high charge states.2 Because of the multiply charging, the mass range of the intermediate pressure Q-TOF (SYNAPT G2) was extended. Many other matrixes followed this initial discovery (Scheme S1), especially after we learned from the literature that the 3-NBN compound has strong triboluminescence behavior137 and began also targeting molecules known to have this feature. With this breakthrough discovery, analytical useful ionization and a broad range of applications followed and finally vendor independent. A few examples are briefly detailed below.

Using the 3-NBN matrix, reaction products were monitored in positive and negative modes. One of these studies, in collaboration with Dr. Mary Kay Pflum (WSU), provided evidence of the utility of vMAI (Figure S16), where ESI or MALDI were not successful, at least not in such a simple straightforward manner.10 One strength is that no acid is required in vMAI70 avoiding undesired hydrolysis hampering some ESI and MALDI applications when standard operation of acid addition is used to improve ionization.138 Other labile post-translational modifications (PTM’s) have been successfully analyzed because no laser is necessary nor is the addition of acids.40,108 Another example is the differentiation of bacterial samples. The ability to differentiate between strains of the bacteria Escherichia coli,9,10,139,140 simply by placing the samples containing the 3-NBN matrix in the intermediate pressure MALDI source without engaging the laser was demonstrated (Figure S17) and provided important proof-of-principle results for subsequent ion source developments by MSTM, detailed below. vMAI using the commercial intermediate pressure MALDI source identified for the first time the unknown antimicrobial peptide (16-mer oncocin) in collaboration with Dr. Christine Chow’s laboratory (WSU).141 Several other types of samples and surfaces have been directly analyzed, including tissues, without the use of a laser,2,6–10,105,136,142 demonstrating that vMAI is not only simple but also highly sensitive and applicable to a variety of analytical challenges.

A simple method to characterize a specific spatially resolved area of a surface is to place a matrix solution on the area of interest, briefly dry, and insert the sample into the vacuum of the mass spectrometer. Only the area where the matrix is applied produces ions.2,8,10,105,136 The ion duration can be several minutes depending on various criteria (pressure, temperature, and source geometry, matrix, sample preparation, and importantly how much matrix is used in the analysis).1,2,10,70 Because of the sensitivity of this approach, we expect that even smaller depositions of the matrix solution will improve spatial resolution measurements from surfaces without the use of a laser.

Because 3-NBN sublimes10,70,143 when in an intermediate pressure source, typically for several minutes, in principle, one has this time to acquire several samples on a plate with a single plate introduction to vacuum (ca. 2 min with the Waters intermediate pressure MALDI source). No carryover between two samples was observed for thin layer chromatography plates because only if the specific sample is located directly in front of the entrance aperture to the hexapole ion guide do the gaseous ions transmit to the mass analyzer and become detected (Figure S18) as long as the two spots were sufficiently separated. Using improved sample preparation protocols, 24 samples applied to a metal plate as 6 different analytes in 4 repeats produced excellent mass spectra of all components in 4 min, not including the 2 min sample loading.8,10,144 Introducing a sample directly into vacuum, similar to vacuum MALDI but without the use of a laser,1,2 provides sensitivity and robustness to carryover and instrument contamination at least comparable to MALDI.145 The typical mass spectrometer capabilities (IMS, MS/MS) can be readily used without employing the laser.1,2,136 Initial experiments demonstrated that the generation of MS images using this ionization method is possible using the vacuum MALDI plate and interface (Figure S19). A very limited number of mass spectrometer vendors currently provide such vacuum MALDI capabilities on API mass spectrometers, but they still exist.

Dr. Malcolm Clench’s group (Sheffield Hallam University) in 2019 implemented vMAI on a modified Q-TOF mass spectrometer fitted with an orthogonal intermediate pressure MALDI source and generated initial results for the generation of images of lipids on brain tissue adding 5% chloroform to the 3-NBN matrix solution.146 Others have also used the vacuum source without engaging the laser. In 2014, Dr. Charles Wilkins’ group (University of Arkansas) studied vMAI on a Bruker Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance (FTICR) mass spectrometer. This was the first time that 3-NBN was used in relatively high vacuum (hence, colder conditions caused by evaporative cooling), and the ionization event took about 30 min.147 Using the laser (355 nm) to ablate the 3-NBN matrix with absorption at around 266 nm,68 produced essentially the same mass spectrometric results with the exception of speeding up the sample consumption to ca. 2 min. This group showed the utility of vMAI and 3-NBN to ionize lipids, demonstrating the potential of vMAI-FTMS to differentiate edible oils by their profile of non-polar and polar lipids and its utility for taxonomic identification of bacteria using crude bacteria extracts.148 Meanwhile, Li’s group used vMAI149 to analyze peptides with PTM’s, as well as the characterization by CID and HCD on an adapted intermediate pressure MALDI-LTQ-Orbitrap XL.

• Inlet ionization conditions

vMAI was first discovered using the intermediate pressure MALDI source on a SYNAPT G2 mass spectrometer. With volatile matrixes which sublime when exposed to sub-AP conditions, the 2 minutes to load the sample can be problematic, thus, a faster and more convenient sample introduction to vacuum was sought. The easiest means was the introduction into the inlet aperture of an API mass spectrometer using e.g., glass plates or pipet tips as sample substrates (Figure S20).128,145,150 This approach provided exceptional simplicity and good sensitivity, without any optimization or application of significant heat (ca. 30 °C). Analytically useful results were obtained, e.g., (Figure S21 to S25).128,145,150–152 Multiply charged ions are produced similar to ESI so that any mass spectrometer designed for ESI can be used with MAI because the only requirement is the access to the sub-AP of the mass spectrometer and an inexpensive matrix such as 3-NBN. With this matrix, an inlet tube is unnecessary and, in fact, added heat typically hampers analyte ion abundance (note, with room temperature liquid matrices, cooling to solid state made them perform as a MAI matrix).70,150 The condition required for ionization to occur is that the matrix must sublime/evaporate.1,4,40 The vMAI matrixes are so volatile that many of them disappear from a glass plate held at room temperature over a 3 to 24 h period, as was monitored by microscopy.70

The 3-NBN matrix is selective in that many common contaminants observed with ESI are not efficiently ionized with 3-NBN, partly because 3-NBN discriminates strongly against ionization by metal cation addition.1,2,4,7,70,107,136,145 Of course, this is often an advantage, specifically for biological MS as is shown in Figure S21 of proteins in collaboration with Mackie and Dr. Young-Hoon Ahn (WSU). The N-lysine methyltransferase (SMYD2) protein, with an expected molecular weight of 49,668 Da (experimental determined 49,844 Da) and EBOV VP40, a recombinant Ebola virus VP40 matrix protein, with a molecular weight of “ca. 35 kDa” (experimentally determined 35127 Da), were readily ionized from buffer solutions diluted 4:1 with water and mixed with 3-NBN. The cone temperature of the SYNAPT G2 was set to 30 °C. For the deconvolution we used MagTran,153 a Freeware deconvolution software for ESI mass spectral data. The protein:matrix (3-NBN) samples were crystallized preferably on the outside of a pipet tip so that the entire sample enters the sub-AP of the mass spectrometer inlet. Using this approach most proteins (Table S2) were readily detected up to ~50 kDa,145,150 while, previously, for BSA and bacteriorhodopsin (~27 kDa), a membrane protein, optimization was required using less volatile matrices or the intermediate pressure source and the 3-NBN matrix.2,107,136 However, Ebola EBOV VP40 matrix protein was readily detected in buffer without cleanup.154 Using the pipet tip approach,9,145,150 there is some of a concern for contamination just like with any other direct injection method used in MS.18,19,31–34 While 3-NBN discriminates against metal adduction, other MAI matrixes ionize analyte by metal cation adduction, in particularly with less basic compounds.155,156 The selectivity as well as ionization is matrix dependent.6–10,14,40,45,70,155,156

Sensitivity equivalent to nanoESI is achieved using the 3-NBN matrix and the MSTM Ionique manual platform to insert a few nanoliters of the matrix:analyte sample dried on the tip of a syringe needle directly into the inlet of an API mass spectrometer.157 As an example, in collaboration with Chow, a synthesized heptapeptide on TentaGel® resin beads of 75 μm size was photo-cleaved and promptly analyzed using MAI-MS and MS/MS and considerations such as charge states as well as CID and ETD on two different mass spectrometers. The collected peptide material was used for the measurements shown in Figure S22. A slight preference for peptide sequencing using ETD and ProSight Lite158 for data interpretation is observed.

The most commonly used matrixes in MS to date are depicted in Scheme S1. Binary matrixes have been discovered which provide increased sensitivity and may provide tunable selectivity and desirable synergistic properties.7,9,14,15,40,45,159 This area of research is in its infancy but holds considerable promise for further improving the MAI and vMAI processes. A large number of compounds are found to act as matrixes, including solvents.1,6,14,23,45,51,55,56,70,155 These solid and liquid matrixes and matrix combinations can be used with or without employing a laser, high or low voltages, at various temperatures (above and below room temperature), and gas flow, but they are typically not necessary and can hamper the production of ions.4,6,7,9,10,40,70,150 While a laser is not required for ionization,1,2,41,52–59,94,105,107,128,139–142,144–157 lasers have been used to achieve high spatial resolution, as in LSI and laser ablation (LA) SAI/MAI.3,9,16,17,26–30,69,94,103,160

A variety of different matrixes showed improvements for different analyte types. Synthetic carbohydrate-lipid conjugates were successfully ionized in the negative ion mode using 2-bromo-2-nitropropane-1,3-diol (bronopol) matrix (Scheme S1). The ionization occurs in the negative ion mode through deprotonation (Figure S23).155 Importantly, using traditional ESI or MALDI analyses failed. Dr. Zhongwu Guo’s group (WSU), for the first time, was able to obtain molecular ions of what they synthesized,161 and seized the opportunity for improving their synthetic and clean up procedures.

The MAI matrix 1,2-dicyanobenzene (1,2-DCB) (Scheme S1) improves the negative mode detection of gangliosides and cardiolipins. The analysis of gangliosides directly from tissue sections in the negative ion mode was developed by undergraduate Corinne Lutomski (WSU) on the Z-spray source of a Waters SYNAPT G2 using a glass plate containing 10 μm thick mouse brain tissue, provided by Mackie’s group and coated with 1,2-DCB. IMS separation was used to help further separate and identify gangliosides and cardiolipins by inclusion of drift times and the concept of nested dataset (Figure S24).162 Cardiolipins are abundant in mitochondria.163 The acquisition conditions were also applicable for the analysis of mitochondrial membrane extracts (refer to data in SI). The experimental setup consisted of the direct extraction of these compounds from the liver, brain, and heart of rats. The MAI analyses were performed with a pipet tip by bringing the tip holding the matrix:analyte sample close enough to the inlet, or touching against the inlet of an ESI source, typically held at 50 °C, on a Waters SYNAPT G2 instrument. These studies were conducted by a visiting graduate student from the WSU school of medicine laboratory of Drs. Thomas H. Sanderson and Karin Przyklenk, and suggests potential use for medical applications (Figure S25). The developed conditions were subsequently used by the Greenberg laboratory (WSU Biology) for the analyses of lipids. Halverson’s group (University of Oslo, Norway), expert in blood spot analyses, demonstrated an initial, but promising utility of MAI-MS of proteomic applications using 3-NBN as matrix.164 In this Special Biemann issue this group employs vMAI-IMS-MS of intact proteins as a potential means to differentiate protein isoforms.165 The capability of analyzing small sample volumes is important across all disciplines. Other positive attributes of the new ionization processes are the simplicity and ease of use as well as their usefulness in many disciplines including human health settings, e.g., clinical use in the Detroit Medical Center (DMC) hospital laboratory, headed by Dr. Srinivas Narayan.142,142,152,150,166,167

In order to automate MAI analyses, sequential samples held at AP using an array of pipet tips were demonstrated on two different mass spectrometers; a linear ion trap LTQ Velos and on a Waters SYNAPT G2. A programmable X,Y,Z-stage was used to align and move samples on pipet tips at AP to the vacuum orifice entrance. Eight samples consisting of small and large compounds were analyzed in 1.22 min.150 The same two instruments and MAI were subjected to a reproducibility study, using six drugs, two matrixes, and on different days. The reproducibility is improved with improvements in matrix:analyte sample introduction into sub-AP of the mass spectrometer and quantification was demonstrated to be comparable with ESI and MALDI using internal standards.152 In collaboration with Narayan’s DMC hospital laboratory, the urine of a newborn was identified to have been exposed to drugs from the mother during pregnancy at levels similar to those determined by ESI.152 With MAI, one can manipulate the cross-contamination issues using different approaches such as choosing a more volatile matrix, taking advantage of the airflow between samples, or by increasing the inlet temperature.6,70,150,168,169

The AP approach of MAI using one of the self-ionizing matrices appears applicable on a wide variety of instruments, as has been shown in proof-of-principle applications through the years, e.g., various Thermo, Waters, Advion, Bruker, SCIEX, Agilent, and homebuilt IMS-MS instruments (Figure S26).10,13,15,17,28,41,43,46,55,145,147,164,166,170 In Movie S-02 we show that the Advion Nanomate can be retrofitted to perfrom MAI eliminating the expensive ESI plate and pipet tips used with the Nanomate. Early work also showed the applicability of “dissolved MAI” (depending on the viewers eye, a “solid containing SAI” or “matrix enhanced SAI” or “liquid enhanced MAI” etc. approach) where a solvent is introduced to the inlet containing a MAI matrix (Figure S27).45 This led to another approach that we used in the Trimpin laboratory in which a premixed matrix:analyte solution is continuously infused into the inlet of the mass spectrometer prolonging the ion abundance and decreasing the inlet temperature requirements as well as cleaning up mass spectra.45,46,107,108 This idea originated from undergraduate students Alicia Richards and Chris Lietz (WSU) who worked on tissue analyses, including improving spatial resolution in imaging. The first laser and matrix enhanced SAI studies were also developed in which the laser ablated tissue plume was captured by the solvent (Figure S11) and subsequently solid matrices added to the solvent and not to the tissue (refer to data in SI).3,9,69,94 The rational was that the matrices would assist in ionization that is more specific and/or in higher ion abundance which we knew at that time to occur inside the inlet tube of the mass spectrometer and the laser will provide ablation from pristine surfaces that stay pristine. With the various surface approaches, other than LSI where even proteins were detected and peptides gas-phase sequenced,23,24,26,30,40 we noticed that preferably small molecules and intrinsically singly charged ions were detected,52,53,94,96,105 however very effectively! The new ionization methods, of course, are limited by the extraction method used, which with a regular solvent matrix is quite ineffective. The good news is that SAI works from 100% water. A relative comprehensive study on surface analyses details the different surface analyses approaches and provides comparisons to the different matrixes used including the 3-NBN matrix.94,96,105 For the direct analysis of tissue sections (Figure S28) provided by Mackie’s laboratory we demonstrated considerable improvement using a laser and a binary matrix combination consisting of 97% 3-NBN and 3% 2,5-DHAP that allows enough stability on the tissue, enough absorption at the laser wavelength (337 nm, N2 laser) and sufficient volatility in the gas phase, at least in parts associated with sufficient airflow using a slightly modified skimmer inlet160 on a SYNAPT G2. A protein with an average molecular weight of 14,135 Da was detected, along with lipids. Operating from AP, 3-NBN, which has absorption at 266 nm,68 can be used with a laser and a variety of different laser wavelengths, as is the case with other MAI matrixes.147,160 However, the volatile matrix (or matrix component) will sublime spontaneously and continuously, as has been observed at vacuum.1,2,71,136

The idea of mixing solution with the best performing matrix (3-NBN) was also shown by, e.g., Drs. Marcos Eberlin and Damilla de Morais (University of Campinas) in 2015 who reported 3-NBN as a solvent dopant to increase the sensitivity in the method called easy ambient sonic-spray ionization (EASI-MS) and desorption ESI (DESI),171 as did others using liquid/solid binary matrixes.172 Other research groups have modified the MAI approach including the composition of the matrix. Murray’s laboratory developed a variation of MAI using an electrically actuated pulse valve to deliver the matrix:sample into the inlet of the mass spectrometer. This group discussed possible applications for imaging using the pulse valve to provide spatial resolution.173 This group also presented another modification of MAI174 using a piezoelectric cantilever with a needle tip attached that was used to strike the surface of 25-μm thick aluminum foil holding the matrix:analyte. The use of silica nanoparticles and the 2-NPG matrix with laser ablation was also demonstrated by this group83 This binary matrix was added on the top of frozen mouse brain tissue and resulted in enhanced detection of multiply charged proteins. In a study by Li’s group, three ionization methods, MALDI, LSI, and MAI,175 were compared using an AP-MALDI source (MassTech) with the laser aligned in RG coupled to a Q-Exactive HF Hybrid Quadrupole-Orbitrap mass spectrometer and compared to an intermediate pressure MALDI-LTQ-Orbitrap XL. This study concluded that LSI and MAI expand the m/z range and improve the intentional fragmentation efficiency using ETD because it provides the beneficial multiply charged ions in comparison with the singly charged ions from MALDI. In another recent report the tip of a wire containing crystallized matrix:analyte was introduced through the interface capillary of the mass spectrometer into the sub-AP of an ion funnel.176 In this vacuum region, the matrix containing the analyte is removed by sublimation from the wire and the formed gaseous charged clusters and ions are collected by the ion funnel and transferred to the mass analyzer. The objective of this work was to study the photophysical properties and photochemical activity of fullerene-dyad to generate reactive oxygen species (ROS).

IMS-MS has now become ‘mainstream’ technology for gas-phase separation and structural characterization offering unique opportunities to enhance molecular analyses and imaging where LC cannot be applied.177 Combining vMAI surface analysis with high resolution MS, IMS, and MS/MS provides exceptionally powerful tools common with API but not high vacuum TOF mass spectrometers. Clinical and medical relevant studies were discussed above. Here, we discuss different compound classes making up, e.g., industrially important materials and/or increased molecular weight. Together with Dr. Barbara Larsen (DuPont), we demonstrated the utility of the ‘pictorial snapshot’178 using vMAI-IMS-MS as a means of observing small changes in complex polymer systems that only differ in shape, as described in this Biemann Special issue.179 We hypothesize that this approach can also be valuable in detecting small differences in the chemical composition of surfaces. Polymers (e.g., fiber from a new car interior) and additives were differentiated by an IMS-MS approach developed by undergraduate Tarick El-Baba (WSU).180 In another example, the ability of vMAI in combination with IMS-MS to detect even small changes in the conformations of the protein lysozyme under reducing conditions was demonstrated (Figure S29).181 More unfolding studies were performed using a MAI-IMS-MS approach. For example, using 2-dimensional IMS-MS plots, unfolding processes can be rapidly monitored (Figure S30A) and, unlike ESI, without concerns for capillary clogging.182,183 We used the Orbitrap Fusion in Stemmer’s laboratory to decipher the differences of two mass units as a result of cleavage of 4 disulfide bridges in lysozyme (Figure S30B). Structural similarities and differences have been reported using the well-studied model system of ubiquitin on commercial and homebuilt IMS-MS mass spectrometers based on MAI, SAI, and ESI methods.46 As an interesting note, on the homebuilt IMS-MS instrument in Clemmer’s laboratory,46 the ion abundance was noticeably improved by adding the matrix containing protein solution directly into the inlet of the mass spectrometer instead of introducing the dried matrix:analyte crystals. A burst of analyte ions was recorded after ca. 15 to 20 seconds after introduction to the vacuum. We hypothesize that the sample solution ‘collects’ on the ‘jet disrupter’ and that, after the solvent evaporates from the matrix and analyte and conditions become “right”, the ubiquitin ions are “explosively” produced under sub-AP conditions. Such an explosive process can sometimes be observed when removing 3-NBN crystals from the original bottle on a spatula. More details on aspects of “sublimation boiling” are discussed in ref. 14. The drift times of the different charge states were the same and others different using the well-established IMS-MS instrument in collaboration with Clemmer’s group.46 For some drift time distribution, sharper forms were observed suggesting improvements in IMS resolution. In the area of IMS using the new ionization processes there is much work to be accomplished in the future.