Abstract

Functional connectivity (FC) patterns in the human brain form a reproducible, individual-specific “fingerprint” that allows reliable identification of the same participant across scans acquired over different sessions. While brain fingerprinting is robust across healthy individuals and neuroimaging modalities, little is known about whether the fingerprinting principle extends beyond the brain. Here, we used multiple spinal functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) datasets acquired at different sites to examine whether a fingerprint can be revealed from FCs of the cervical region of the human spinal cord.

Our results demonstrate that the functional organisation of the cervical spinal cord also exhibits individual-specific properties, suggesting the potential existence of a spine-print within the same acquisition session.

This study provides the first evidence of a spinal cord connectivity fingerprint, underscoring the importance of considering a more comprehensive view of the entire central nervous system. Eventually, these spine-specific signatures could contribute to identifying individualized biomarkers of neuronal connectivity, with potential clinical applications in neurology and neurosurgery.

Keywords: fMRI, functional connectivity, brain fingerprinting, spinal cord imaging, inter-subject variability

1. Introduction

Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) provides a non-invasive tool for capturing the spatiotemporal features of brain activity across individuals (McGonigle et al. 2000; Dubois and Adolphs 2016). For resting state, pairwise correlations between regionally-averaged time series define a functional connectivity (FC) profile that characterizes statistical dependencies between activity in different brain regions (Sporns, Tononi, and Kötter 2005; Fornito, Zalesky, and Bullmore 2016). While most of the early studies in neuroimaging have analyzed FC patterns at the group level to identify robust population trends (Margulies et al. 2016; Snyder and Raichle 2012), such approaches might overlook meaningful inter-individual differences. In the human brain, FC profiles have been shown to act as distinctive neural “fingerprints”. The pivotal study of (Finn et al. 2015) demonstrated that each individual’s FC pattern remains consistent across multiple sessions and conditions, allowing to reach up to 95% identification accuracy across 126 subjects at rest. In this context, the frontoparietal network emerged as being particularly distinctive, hence enabling accurate identification of individualized FC patterns, underscoring their potential for personalized neuroimaging applications. Over the past decade, a growing body of work has shown that the accuracy of brain fingerprinting depends on multiple factors, including scan length, the inter-scan interval (Amico and Goñi, 2018; Horien et al., 2019), and the presence of different clinical (Sorrentino et al. 2021; Stampacchia et al. 2022, 2021) or cognitive conditions (Luppi et al. 2023,2025; Tolle et al. 2024). Methodological advances have also improved performance. For instance, (Amico and Goñi 2018) examined approaches to enhance the distinctiveness of individual functional connectomes using dimensionality reduction based on principal component analysis (PCA). They quantified how consistently an individual’s FC profile could be recognized across different sessions, achieving near-perfect classification when only the most informative connections were retained.

Similarly, (Li, Wisner, and Atluri 2021) investigated optimal strategies for feature extraction in brain fingerprinting, by selecting the most relevant edges rather than the whole brain connections. In terms of the dynamic and temporal features of brain fingerprints, (Van De Ville et al. 2021) showed that identification is possible even at short time scales (i.e. in less than 30 seconds of fMRI activity), but that the strength fluctuates significantly over time. In a more recent study, (Ghaffari et al. 2025) demonstrated that the subcortical-cerebellum network had a substantial contribution in the static case, while playing a less prominent role in any of the dynamic fingerprints. Other studies have also investigated an individualized approach using Connectome Fingerprint (Tobyne et al. 2018), which is more focused on the prediction of individualized task activation. Building on this work, (Tripathi and Somers 2023) found that using a subject’s own FC generally resulted in higher prediction accuracy for their task activations compared to using connectivity from other individuals. In particular, FC patterns between the cerebral cortex and cerebellum carried crucial information for these predictions. A minor involvement of the cerebellum for the fingerprint accuracy was also found (Mantwill et al. 2022). Beyond fMRI, brain fingerprinting extends across various neuroimaging modalities, including electroencephalography (EEG) (Fraschini et al. 2016; W. Kong et al. 2019; Demuru and Fraschini 2020), functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) (de Souza Rodrigues et al. 2019), and magnetoencephalography (MEG) (da Silva Castanheira et al. 2021; Sareen et al. 2021), highlighting the robustness of individual-specific connectivity patterns across different measurement techniques.

While brain functional connectivity has been widely studied, the same cannot be said for the spinal cord, despite its pivotal role in sensory and motor functions (for reviews Landelle et al. 2021, Kinany et al. 2022). However, the spinal cord is more than a pathway for relaying sensory and motor signals between the brain and the effectors. A large body of literature demonstrates that the spinal cord is also involved in a range of integrative and plastic processes, including learning (Grau 2014; Vahdat et al. 2015; Khatibi et al. 2022; Wolpaw 2007), pain modulation, and modulation of descending signal from supraspinal structures (Ossipov, Morimura, and Porreca 2014; Martucci and Mackey 2018; Nim et al. 2021). Furthermore, a series of pioneering studies (Khatibi et al. 2022; N. Kinany et al. 2023; Vahdat et al. 2015) investigating motor sequence learning with simultaneous human brain and spinal cord fMRI have provided in vivo evidence supporting learning-related plasticity within the spinal cord. Complementing this, more recent findings suggest that the human spinal cord is also involved in predictive processing, with prior knowledge influencing spinal responses to sensory stimuli as early as 13–16 milliseconds after stimulation (Stenner et al. 2025). These insights are further supported by neurophysiological evidence pointing to a complexity in spinal function beyond its classical sensorimotor role, including contributions to affective dimensions. For example, observing others in pain can evoke spinal responses similar to those triggered by first hand pain (Tinnermann, Büchel, and Haaker 2021). Moreover, local interneuronal circuits appear to support task learning, and computational models suggest that these circuits may self-organize through Hebbian learning (Enander, Loeb, and Jörntell 2022). Altogether, these processes may give rise to nuanced, individual-specific connectivity patterns in the spinal cord. Supporting this idea, test-retest experiments have shown that functional connectivity profiles remain stable across sessions, suggesting consistent and potentially unique signatures at the individual level—a prerequisite to probe the existence of a “spinal cord fingerprint”, or “spine-print” (Barry et al. 2016; Kaptan et al. 2023; Kowalczyk et al. 2024).

Inspired by brain fingerprinting and the spinal-cord reliability studies, herein we provide the first direct evidence supporting the existence of a spinal cord fingerprint, for which we coin the term “spine-print”. We investigate whether individual FC patterns could be reliably identified in the cervical spinal cord, akin to those observed in the brain. To test this, we computed identifiability scores from cervical spinal cord FC profiles using three independent datasets, one of which included simultaneous brain and spinal cord acquisitions. Following (Amico and Goñi 2018), we implemented a pipeline to extract identifiability metrics and assess the reliability of specific spinal connections, and successfully confirmed the existence of spine-prints including which functional connections were most distinctive across individuals. In addition to assessing spinal cord identifiability in isolation, we established the individual fingerprints of the brain, the spinal cord, and their interaction. These findings contribute to a growing body of work suggesting that the spinal cord, far from being a mere relay, may play a dynamic and individual-specific role in the human central nervous system.

2. Methods

2.1. Datasets

This study examines three distinct datasets: Dataset 1 (partially published data from Vanderbilt University), which originally comprised 20 healthy volunteers (10 female, mean age years). However, two female participants were excluded—one due to missing physiological recordings and the other because of a higher slice placement along the spinal cord, which complicated normalization to the template and reduced consistency in spinal level overlap across participants; Dataset 2 from the Max Planck Institute in Leipzig, Germany that consists of 43 participants selected from a pool of 48 subjects in the publicly available OpenNeuro data (Kaptan et al. 2023): five participants were excluded (four due to missing physiological data and one due to a different number of acquired volumes); Dataset 3 (unpublished data with similar acquisition protocol to (Landelle et al. 2024)) includes 15 participants (7 female, years old).

Participants in Dataset 1 provided written informed consent under a protocol approved by the Vanderbilt University Institutional Review Board. These data were then analyzed under a protocol approved by the Mass General Brigham Institutional Review Board. Dataset 2 was already published (Kaptan et al. 2023), having therefore ethical approval. Dataset 3 study was approved by the ethic committee of the Institut universitaire de gériatrie de Montréal (#CERVN 17-18-20), which follows the policies of the Canadian Tri-Council Research Ethics Policy Statement and the principles expressed in the Declaration of Helsinki.

2.2. Data acquisition

Dataset 1

These data were acquired by R. Barry while at the Vanderbilt University Institute of Imaging Science. Experiments were performed on a Philips Achieva 3T scanner (Best, The Netherlands) with a dual-channel transmit body coil and the vendor’s 16-channel neurovascular coil (6 head, 4 neck, and 6 upper chest channels). Each scanning session began with a sagittal localizer to identify the general anatomy and location of the C3/C4 intervertebral disc. The imaging stack was then centered at this level, ensuring that all slices were perpendicular to the cord. The imaging stack covered vertebral levels C2-C5, roughly corresponding to the spinal nerve root levels C3-C6. High-resolution axial anatomical images were acquired using an averaged multi-echo gradient echo (mFFE) T2*-weighted sequence with the following parameters: field of view , acquired , interpolated , 12 slices, first TE = 7.20 ms, 4 additional echoes where (5 echoes in total), repetition time (TR) = 700 ms, flip angle = 28°, sensitivity encoding (SENSE) = 2.0 (left-right), and number of acquisitions averaged = 2. Total acquisition time for the anatomical scan was 5 mins and 26 s. A saturation band was positioned anterior to the spinal cord to suppress signal from the mouth and throat. These anatomical data were presented in a previous publication measuring T2* in spinal cord gray matter (Barry and Smith 2019). Resting state fMRI data were acquired with identical slice placement using a 3D multi-shot gradient-echo sequence: volume acquisition time (VAT) = 2080 ms, TR/TE = 34/8 ms, flip angle = 8°, slices. The two separate 10-min (288 volumes each) were separated by a ~2-min period to give the subject a chance to rest. Respiratory and cardiac cycles throughout both runs were externally monitored and continuously recorded using a respiratory bellows and a pulse oximeter. These fMRI data were previously analyzed and presented in a conference abstract (Rangaprakash Deshpande & Barry Robert 2021).

Dataset 2

The second dataset, described in detail in (Kaptan et al. 2023), was acquired using a 3T Siemens Prisma MRI system equipped with a whole-body RF coil, a 64-channel head-and-neck coil, and a 32-channel spine-array coil. Participants were instructed to remain still, breathe normally, and avoid excessive swallowing. The dataset is part of a larger methodological project, focusing on two functional MRI acquisitions and one structural acquisition.

Functional MRI runs included 250 single-shot gradient-echo EPI volumes (VAT = TR × number of shots (1) = 2312 ms, 9.63 min of duration), covering the spinal cord from C2 to T1 with 24 slices (5 mm thickness) and a cross-section resolution of . The acquisitions used z-shimming to counteract signal loss due to magnetic field inhomogeneities, with two runs differing in manual vs. automatic z-shim selection.

A high-resolution T2-weighted 3D sagittal SPACE sequence was acquired for registration. Peripheral physiological signals (respiration via a breathing belt and cardiac activity via ECG electrodes) were also recorded for physiological noise modeling.

Dataset 3

The last dataset was acquired by J. Doyon’s group. It is characterized by 2 functional runs back-to-back, also intervalled by a few minutes following similar acquisition parameters as Landelle et al. 2024. Data were acquired on a 3T MRI Scanner (Magnetom-Prisma, Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) with a 64 channel head and neck coil. The blood-oxygen-level-dependant (BOLD) images were acquired using a gradient-echo echo-planar imaging (EPI) sequence with the following parameters: VAT = TR = 1550 ms, TE = 23 ms, in-plane ; slice thickness = 4 mm, FOV = 120 mm × 120 mm, flip angle = 70°; iPAT acceleration factor PE = 2, iPAT acceleration factor slice = 3. A total of 69 axial slices were acquired from the top head to C7/T1 vertebrae. Each resting-state run lasted 10 minutes and 35 seconds (230 volumes). Physiological recordings were acquired using a pulse sensor and a respiration belt (Siemens Physiology Monitoring Unit).

Brain/spinal cord structural images were acquired using a high-resolution T1-weighted anatomical image in the sagittal direction (MPRAGE sequence: TR/TE = 2300/3.3 ms, , flip angle = 9°). In total, 288 slices were acquired, covering the top of the head to the upper thoracic regions T2-weighted images were acquired, spanning from the top of the cerebellum to the upper thoracic region (approximately at T1), thereby encompassing the entirety of the cervical spinal cord. These images were collected in the transverse orientation with the following parameters: TR = 33 ms; TE = 14 ms; FOV = 211 mm × 249 mm; flip angle = 5°; in-plane voxel resolution = 0.35 mm × 0.35 mm, slice thickness = 2 mm.

2.3. Data preprocessing

We applied an in-house preprocessing pipeline for the first two spinal cord datasets publicly available on github (https://github.com/MIPLabCH/SC-Preprocessing.git), while the third brain/spinal cord dataset was preprocessed using (Landelle et al. 2024) preprocessing pipeline. The two pipelines include comparable preprocessing steps for the spinal cord; see (Landelle et al. 2024; Ricchi, Kinany, and Van De Ville 2024) for reference, no spatial smoothing was applied.

2.3.1. Preprocessing of Datasets 1 & 2

The spinal cord functional and structural images were pre-processed using Python (version 3.9.19), with the nilearn library (version 0.9.1) falling under the umbrella of scikit-learn (version 0.24.2), FMRIB Software Library (FSL; version 5.0), and Spinal Cord Toolbox (SCT; version 5.3.0; (De Leener et al. 2017)). The following preprocessing steps were performed: i) slice-timing correction (FSL, ‘slicetimer’), ii) motion correction using slice-wise realignment and spine interpolation (with SCT, ‘sct_fmri_moco’), iii) segmentation of functional and structural images (with ‘sct_deepseg’, followed by manual correction), iv) time series denoising (see details in the next paragraph), v) registration of functional images to anatomical images, and finally vi) coregistration of functional images to anatomical images, and then, to the PAM50 template (with SCT, ‘sct_register’ multimodal and ‘sct_register_to_template’ with nearest neighbor interpolation). Additionally, we assessed the data quality of the three datasets by obtaining voxelwise tSNR values with the SCT’s function ‘sct_fmri_compute_tsnr’ (De Leener et al. 2017), which computes each voxel’s temporal mean and divides it by its standard deviation.

2.3.2. Time series denoising of Datasets 1 & 2

The time denoising series denoising follows the same procedure as previous spinal fMRI (Kinany et al. 2024; Landelle et al. 2024; Ricchi, Kinany, and Van De Ville 2024; Landelle et al. 2023) relying on the ‘clean_img’ function from the nilearn library, This approach enable the removal of the noise confounds orthogonally to the temporal filter. Specifically, confounds and the band-pass temporal filter (cut-off frequencies: 0.01 Hz and 0.13 Hz) were projected onto the same orthogonal space, following the methodology outlined in (Lindquist et al. 2019), instead of being applied sequentially.

Physiological noise correction was performed using a model-based approach inspired by RETROICOR (RETROspective Image CORrection; (Glover, Li, and Ress 2000)), which models physiological signals as quasi-periodic and maps their phases onto each image volume using a Fourier series expansion. To implement this, we used FSL’s Physiological Noise Modeling (PNM) tool to generate nuisance regressors from cardiac, respiratory, and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) signals. Cardiac peaks were identified using the ‘scipy.signal.find_peaks’ function (Virtanen et al. 2020), followed by manual verification to ensure detection accuracy.

We followed established guidelines for physiological noise correction in spinal cord fMRI (Y. Kong et al. 2012). Both cardiac and respiratory regressors were modeled with an order of 4, including the fundamental frequency and the first three harmonics. Their interaction was modeled up to second order, producing a total of 32 regressors on a slice-by-slice basis. Additionally, a CSF regressor was derived by averaging the signal from the 10% most variable CSF voxels. Each of these regressors was applied independently per slice using the ‘clean_img’ function to account for the anatomical and physiological specificity of spinal cord data.

2.3.3. Preprocessing and denoising of Dataset 3

As this dataset includes simultaneous brain and spinal cord acquisition, we adapted the previously described approach accordingly. For each participant, all the functional and structural images were pre-processed separately for the brain and the spinal cord using the Spinal Cord Toolbox (SCT; version 5.6), FSL, SPM, and in-house Python and MATLAB programs. First, T1w images were cropped to separate the brain and spinal cord. Spinal cord segmentation was carried out using SCT (sct_propseg) and manually corrected when necessary. The brain structural images were segmented using Cat-12 toolbox (SPM) into gray matter (GM), white matter (WM), and CSF.

The spinal cord volumes of each functional run were averaged, and the centerline of the cord was automatically extracted from the mean image (or drawn manually when needed). A cylindrical coarse mask with a diameter of 15 mm along this centerline was drawn and further used to exclude regions outside the spinal cord from the motion correction procedure, as those regions may move independently from the cord.

Motion correction was performed using the first volume as the target image and resulted in the motion corrected time series (‘sct_fmri_moco’ from SCT). Moco was carried out using slice-wise translations in the axial plane with spline registration. The resulting mean image of the motion corrected images was used for segmentation of the cord using propseg (manual correction was done when necessary). The mean moco image was warped into the PAM50 space using the concatenated warping field obtained at the anat step (i.e., from T1w to T2w to PAM50 space) to initialize the registration (with SCT, ‘sct_register_multimodal’).

As for the brain volumes, they undergo a standard preprocessing (Power et al. 2014, 2012) using FSL ‘bet’ function for estimating the masks, FSL ‘mcflirt’ to apply motion correction, and coregistering the functional images to T1w and the MNI template using SPM12.

For each participant, the nuisance regressors were modeled to account for physiological noise (Tapas PhysiO toolbox, an SP extension (Kasper et al. 2017)). Peripheral physiological recordings (heart rate and respiration) using the RETROspective Image CORrection (RETROICOR) procedure (Glover et al. 2000). Specifically, four respiratory, three cardiac harmonics were modelled, and one multiplicative term for the interaction between the two (18 regressors in total, (Kinany et al. 2024; Landelle et al. 2024)). CompCor approach (Behzadi et al. 2007) was used to identify non-neural fluctuations in the unsmoothed brain or CSF signal by extracting the first 12 principal components for the brain and the first 5 for the spinal cord. These nuisance regressors were complemented with the two spinal cord motion parameters (x and y), the six brain motion parameters and motion outliers.

Similar to dataset 1 and 2 the removal of the noise confounds was based on a projection onto the orthogonal of the fMRI time-series space and was applied orthogonally to the band-pass temporal filter (0.01–0.13 Hz) using the Nilearn toolbox (‘clean_img’ function (Lindquist et al. 2019)).

2.3.4. Parcelled time series

Spinal cord

We defined a parcellation scheme consisting of 14 spinal cord regions in the cross-section characterized by 6 bilateral regions of the gray matter (intermediate zone (iz), ventral (vh) and dorsal horns (dh)) and 8 bilateral white matter regions (spinal lemniscus (SL), cortico-spinal tract (cst), fasciculus cuneatus (fc) and gracilis (fg)). These anatomical regions were delineated according to the atlas of the Spinal Cord Toolbox (De Leener et al. 2017). The number of spinal levels included is determined by the acquisition coverage (Figure 1) and the overlap among participants. Levels at the extremities were cropped in some participants; thus, to maintain consistency, only levels fully overlapping across all participants are considered. Specifically, Dataset 1 included 3 spinal levels (C4–C6), resulting in a parcellation of 42 regions of interest (ROIs); Dataset 2 comprised 5 fully overlapping spinal levels (C4–C8), yielding a dimensionality of 70 parcelled time series; and Dataset 3 spanned spinal levels C2–C8, covering a total of 7 spinal levels and resulting in 98 ROIs.

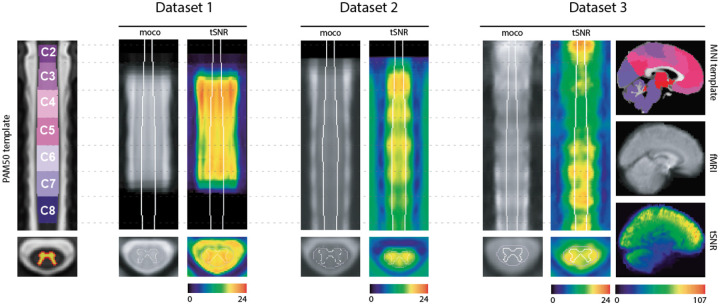

Figure 1. Datasets overview.

Left panel: coronal view of the PAM50 template (y=70) with spinal level annotations (C2-C8) and the gray matter probability mask on the axial view. The three datasets are shown sequentially with the mean motion-corrected fMRI and the tSNR maps. Dataset 3 additionally includes whole-brain coverage, with the brain data shown alongside the MNI template of 2mm resolution in the sagittal plane (x=45).

The voxel time series from the registered, denoised functional images were averaged using a robust mean, considering only time points between the 5th and 95th percentiles. In the paper we will refer to the number of spinal cord ROIs with .

Brain

For Dataset 3, we also extracted parcelled brain time series following the same procedure: computing the robust mean across voxels within each of the 100 ROIs defined by the Schaefer’s atlas (Schaefer et al. 2018) and complemented by 19 subcortical areas (Seitzman et al. 2020), resulting with a parcellation of .

2.4. Fingerprinting

2.4.1. Methodology

We follow the steps proposed in earlier work at the brain level (Amico and Goñi 2018). Let us assume participants for which denotes the FC matrix of run for participant . Each matrix has a dimensionality of , where indicates the number of ROIs (which can be or , depending on whether spinal cord or brain regions are considered). The concept of fingerprinting centers on the ability to identify individuals based on these FC patterns; i.e., by comparing an individual’s FC matrix from one run against those from all participants, including another run from the same subject (Finn et al. 2015; Amico and Goñi 2018). In this framework, two runs are available per subject (test-retest). To enable comparison, the upper triangular part of each is unfolded to a vector of dimension , to which Pearson correlation is applied. This results in the so-called identifiability matrix , of size , which is asymmetric. The diagonal elements reflect self-similarity between the two runs of the same participant, while the off-diagonal elements (with ) capture between-participant similarities. Let be the average of the diagonal elements, and the average of the cross-individuals similarities. We can now define a fingerprinting performance metric (‘Idiff’) as the difference between these values . Moreover, following also (Amico and Goñi 2018), we explored the PCA of the FC profiles to maximize Idiff by applying dimensionality reduction (see supplementary material for details).

To further quantify the strength of the fingerprinting effect, we calculated Cohen’s D (Cohen 1992) as a standardized measure of the difference between two means ( and in particular), reflecting how large this difference is relative to the variability within the data. Let be the variance of the self-similarities and the variance of the off-diagonal elements, then the effect size is defined as follow:

| (1) |

A higher Cohen’s D value indicates a greater separation (in standard deviation units) between individuals, thus stronger identifiability.

Following (Finn et al. 2015), we also calculated the success rate as the number of participants that could be identified. A participant was considered correctly identified if the highest correlation in their row of the identifiability matrix appeared on the diagonal. This indicates that their FC profile from the first run was more similar to their own profile than to that of any other participant from the second run. We also propose a more lenient measure by computing the participants’ identification accuracy based on whether the correct participant was within the top 2, 3, 4, or 5 highest correlation values.

To assess which FC patterns contributed most reliably to individual identifiability, we used the one-way random model for the intraclass correlation coefficient that is known as ICC(1,1) (McGraw and Wong, 1996). Specifically, this metric measures the absolute agreement of repeated measurements for each connection across individuals:

| (2) |

where (number of runs), is the mean square between individuals, and is the within-participant (error) variance. This computation was repeated independently for each edge, yielding a vector of ICC values, which were then mapped back to the space to obtain the full ICC matrix. This method provides a fine-grained identifiability map of which FC edges are most stable across runs, reflecting their test-retest reliability. To have an overall overview of these reliable edges in the context of the spinal cord, we averaged the ICC matrices across datasets and all levels. For the cervical spinal cord, we recall that the number of ROIs is 14 in the cross-section (i.e., bilaterally for gray matter: dh, vh, iz; and for white matter: cst, fc, fg, sl). Moreover, we examined the ICC matrices after thresholding at the 95th percentile to retain only the most reliable edges. To shift the focus from the connections to region-based reliability, we computed the nodal strength of this filtered matrix by summing the values across one axis, providing a measure of reliability for each ROIs rather than for specific connections.

2.4.2. Investigating brain and spinal cord time courses

To further explore Dataset 3, we applied the fingerprinting pipeline to the full FOV including brain and cervical spinal cord, and looked at three FC profiles: brain-only, spine-only, and brain-spine interaction. In addition, we examined the relationship between brain and spinal time series using a simple linear regression framework (equation 3) in two directions: (i) modeling spinal cord activity (denoted as ) using brain signals as predictors, and (ii) modeling brain activity using spinal cord signals predictors.

Since the imaging was acquired simultaneously, the time axis is shared between the dependent and independent variable . Both matrices have dimensions , where corresponds to the number of ROIs − either for spinal cord or for brain − and is the number of time points. As a result, the regression coefficients have also different dimensionality depending on the direction of modeling. We denote the brain-to-spine model coefficients as (of size ), and the reverse model as (of size ).

The linear regression is defined as:

| (3) |

where are the predicted values and represents the residuals. In the first, model the residuals capture the portion of the spinal signal not explained by the brain activity and dimensionality . In the second model, the residuals represent the portion of the brain signal not explained by the spine and have dimensionality of . We then used these residuals to compute new FC profiles that reflect variance not accounted for by the other region.

Results

3.1. Data quality and overview

In Figure 1, we present an overview of the three datasets analyzed in this study together with the template spaces that were employed: PAM50 for spinal cord data (left) and MNI for brain data (right, shown alongside Dataset 3, which covers the brain). The ROIs in the brain were defined using the Schaefer-100, complemented by 19 subcortical areas, and are visualized on the MNI template. For the spinal cord, only spinal levels C2-C8 are shown on the PAM50 template, reflecting the coverage range of the spinal cord acquisitions across datasets. Mean fMRI images and tSNR maps of the first run are also provided for each dataset. In the spinal cord, tSNR values reach a maximum mean value of 22.6 in Dataset 3, followed by 21.3 for Datasets 1, while in Dataset 2, the maximum value is 19 (within the cord mask). By comparison, brain tSNR values are substantially higher, reaching up to 107.

3.2. Fingerprint of the central nervous system

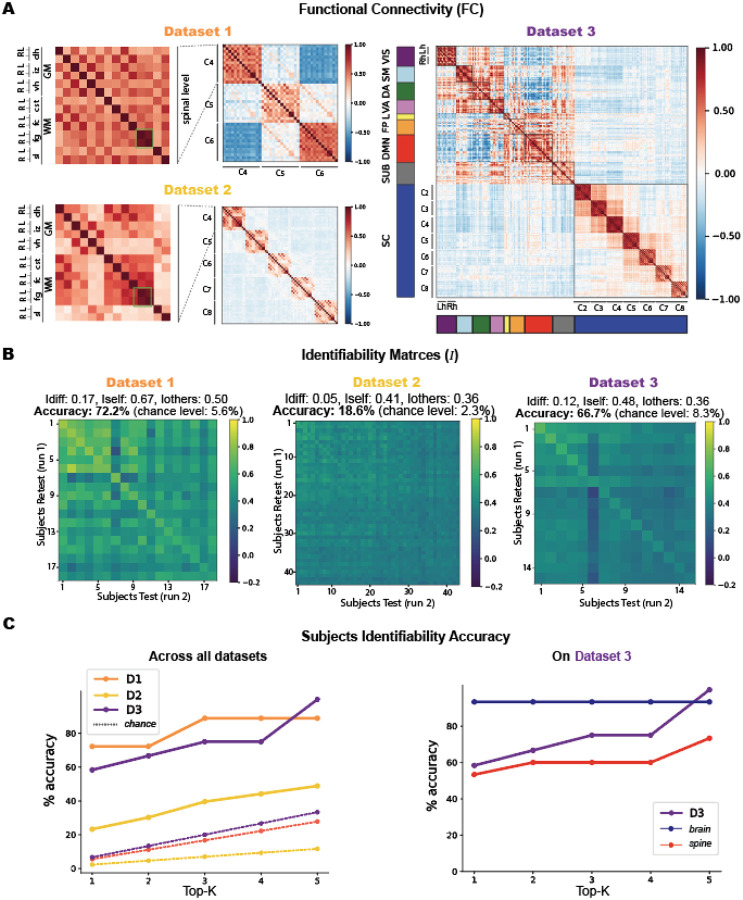

In Figure 2, we display the FC (A) and identifiability matrices (B) derived from the three datasets. The zoomed-in panels in (A) highlight the anatomical organization of the ROIs in the spinal cord, with gray and white matter regions alternating from left to right—a sorting scheme that remains consistent throughout the paper whenever spinal levels are referenced. Brain regions, on the other hand, are sorted according to the Yeo functional networks (Yeo et al. 2011), concatenating left and right hemispheres (Lh, Rh) within each network.

Figure 2.

Overview of functional connectivity (FC) matrices and identifiability results for the three datasets. A. FC matrices of the first run from each dataset. The most-left matrix is a zoomed-in view of the spinal level C4 for both Dataset 1 and 2 to show the labeling and sorting of the spinal cord ROIs used for all the spinal levels in all matrices. On the right Dataset 3 FC displays the brain ROIs with Yeo’s sorting of the 7 functional networks (VIS, SM, DA, VA, L, FP, DMN), followed by the subcortical regions (SUB) and the 7 spinal levels. The brain functional networks have the left hemisphere first (Lh) and the right (Rh) after. B. The second row shows the corresponding identifiability matrices for each dataset, along with the reached scores and accuracies. C. On the left, a plot illustrates participants identifiability accuracy as a function of the top-K (from 1 to 5) highest correlation values across the three datasets. On the right, a detailed plot for Dataset 3 shows identifiability accuracy as a function of top-K values, with separate curves for brain-only and spine-only data.

Across all datasets, spinal cord connectivity reveals a strong bilateral (left-right) correlation, within the gray matter. The most prominent connectivity involves the intermediate zone (iz), which exhibits strong correlations with the ventral horns (vh), followed by weaker but consistent connections with the dorsal horns (dh). Beyond the GM, we also observe bilateral connectivity patterns in the white matter. Among these, the fasciculus gracilis (fg) stands out as the only ROI that consistently exhibits a distinct and highly bilateral connectivity pattern across all spinal levels and datasets, as highlighted in the green boxes of Figure 2A, and the fasciculus cuneatus (fc) connectivity with some gray regions.

In Dataset 1, the highest correlation is observed in the bilateral fg, reaching 0.69. This is followed by the iz-vh connectivity, with values of 0.50 on the right and 0.49 on the left side. The fc-dh also exhibits strong connectivity, with 0.47 on the left and 0.46 on the right. The IZ connects with the fasciculus cuneatus (fc) at 0.43 on the right and 0.41 on the left side. Fg and fc show bilateral correlations of 0.40. Within the gray matter, the dh-iz connection reaches 0.38 on the right and 0.34 on the left, while dh-iz connectivity is slightly lower, at 0.27 (right) and 0.24 (left). Finally, bilateral connectivity within the ventral horns (VL–VR) is 0.23, and within the dorsal horns (DL–DR) it is 0.14.

Dataset 2 shows a similar profile. Bilateral fg connectivity remains the strongest, with a correlation of 0.66. This is followed by dh–fc connectivity, with 0.47 on the left and 0.45 on the right. The iz-vh connections show values of 0.42 (left) and 0.41 (right), while fg-fc correlations are consistent at 0.39 on both sides. Dh-iz connections are slightly lower, at 0.28 (right) and 0.27 (left). Interestingly, VL–VR and DL–DR correlations are 0.13 and 0.12, respectively, slightly exceeding the horn-to-horn connectivity observed elsewhere, which typically remains below 0.1.

In Dataset 3, similar trends persist, but with overall stronger correlations. Bilateral fg connectivity reaches its highest value at 0.83. The iz-vh and dh-fc connections also show very strong bilateral correlations, both around 0.80. The fg-fc correlation remains high at 0.75 bilaterally. In this dataset, the corticospinal tract (cst) also displays strong connectivity with the dorsal horns, reaching 0.69 on the right and 0.68 on the left side. Gray matter connections follow with dh-iz at 0.61 and dh-vh at 0.49 on both sides. Finally, the ventral horn bilateral correlation (VL–VR) reaches 0.33, and the dorsal horns (DL–DR) show a correlation of 0.27.

To assess the consistency of these subject-averaged correlations, we computed the identifiability matrix (I), which quantifies the extent to which each participant’s FC profile is distinct within the dataset across two runs (Figure 2B). We recall that is an matrix, where is the number of participants in a dataset. These matrices exhibit a clear diagonal pattern, indicating that each participant’s FC profile is more similar to their own than to anyone else’s. The maximum correlation values observed on are 0.85 for Dataset 1, 0.6 for Dataset 2, and 0.68 for Dataset 3. Dataset 1 reaches an with a subject identification accuracy of 72.2% (13 participants were correctly identified over 18, chance level = 5.6%). Dataset 2 reaches an , accuracy = 18.6% (8 participants correctly identified over 43, chance level = 2.3%). Dataset 3 , accuracy = 66.7% (10/15 correctly identified, chance level = 8.3%). Cohen’s D effect sizes of Iself and Iothers provide a measure of the magnitude of their difference. That is, Datasets 1 and 3 exhibit very large effect sizes with 1.40 and 1.43, respectively. While Cohen’s D values of the brain-only were 1.87, of the spine only 0.96, and their interaction (brain-spine) 0.93. Despite the relatively low Idiff values and accuracy in Dataset 2, it still shows a medium effect size (Cohen’s D = 0.7). Typically, effect sizes are considered small between 0.2–0.4, medium between 0.5–0.8, and large above 0.8.

The accuracies across the three datasets display an upward trend (Figure 2C, left column) when considering whether each participant was among the top 1 to 5 highest correlation values. In Dataset 3, when analyzing brain and spine data separately, the accuracy stays constant for the brain, while it shows an increase for the spine.

3.3. Reliability of the fingerprint

The intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) was used to evaluate the reliability of FC patterns across the two runs. To summarize spinal cord ROI reliability, we computed the mean ICC values across cervical levels for the three datasets (Figure 3B). According to standard guidelines (Hallgren 2012; Cicchetti and Sparrow 1981), ICC values are interpreted as: poor (<0.4), fair (0.4–0.59), good (0.6–0.74), and excellent (≥0.75).

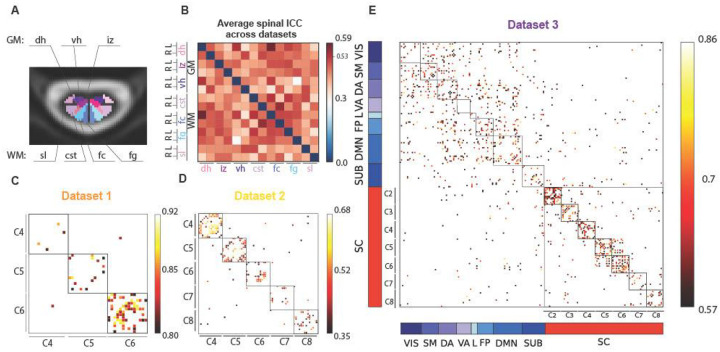

Figure 3. ICC results.

(A) Spinal cord ROIs displayed in a cross section of the spinal cord (gray matter (GM) regions: dh = dorsal horns, iz = intermediate zone, vh = ventral horns, white matter (WM) regions: sl = spinal lemniscus, cst = cortico-spinal tract, fc = fasciculus cuneatus, fg = fasciculus gracilis). (B) Average ICC matrix across all spinal levels and datasets, indicating the 95th percentile in the colorbar (0.526). (C-D-E), namely, Datasets 1,2, and 3. (E) For Dataset 3, brain ROIs are sorted according to the Yeo functional networks (Yeo et al. 2011) (VIS = visual, SM = somatomotor, DA = dorsal attention, VA = ventral attention, L = limbic, FP = fronto-parietal, DMN = default mode network, SUB = subcortical). The color bar values are adjusted according to the distribution of the values, reporting the 95th percentiles of each dataset’s ICC as minimum to show a filtered ICC matrix.

Across all datasets, the most reliable connection in the spinal cord—above the 95th percentile threshold (ICC = 0.526)—was observed between the left dorsal GM horn and the left fasciculus cuneatus (ICC = 0.586), followed by cst-fc right connection (ICC = 0.56), and the left connections of the ventral GM horns and dorsal GM horns (ICC = 0.54), both falling within the “fair” reliability range.

Looking at each dataset individually: (i) Dataset 1 showed excellent ICC values, particularly at the C6 level. When averaging ICC values across the three spinal levels to obtain nodal strength per ROI, the left fc-dh connectivity had the highest average ICC (0.81), followed by the bilateral fc with 0.78, (Figure 3C). Dataset 2 exhibited overall lower ICC values, with the 95th percentile at 0.41 and a maximum ICC of 0.45 (interpreted as “fair”). Here too, nodal strength was highest for the left fc-dh connectivity (0.45), followed by the fg-dh on the left side, and lowest for the bilateral cst-fc (0.41) (Figure 3D). Dataset 3 had higher reliability overall, with ICC values above 0.57 (95th percentile), and a maximum ICC of 0.86 (Figure 3E). In the brain, the most reliable connection (0.86) was the left salient ventral attention (VA) with the left DMN prefrontal cortex 5 (DMN) and the lowest ICC reached 0.63 with the left visual network 9 (VIS) and the right somatomotor 8. In the spinal cord, the most reliable connection was right fc with right spinal lemniscus (sl) with a good ICC of 0.6 and the lowest (0.57) was between fc and vh right.

Considering the nodal strength as mean values across the ICC matrix along one axis, in the brain, the values were relatively consistent across regions, averaging around 0.68, with the visual network and subcortical regions showing the lowest value (0.64), and default mode network (DMN) and limbic network (L) with 0.7. Interestingly in all three datasets, the spinal cord exhibit the strongest nodal strength for fasciculus cuneatus (fc), followed by fasciculus gracilis (fg) and dorsal horns (dh), while the lowest values differ in the three datasets: Dataset 1 smallest nodal strength was found in the ventral horns, in Dataset 2 it was the intermediate zone, and the cst for Dataset 3.

3.4. Brain and spine

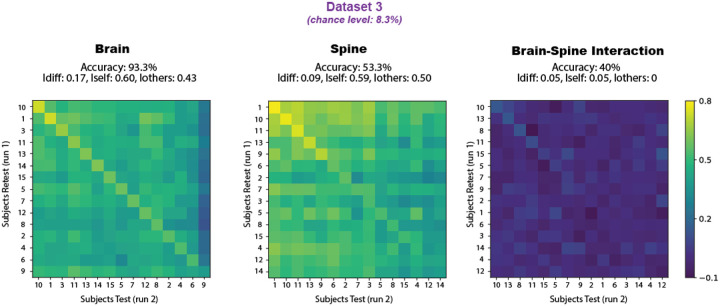

We conducted a more in-depth analysis of Dataset 3, focusing on functional connections within the brain, the spinal cord, and between the two. In Figure 4, the identifiability matrices for each of these components are shown, along with their corresponding accuracy and identifiability scores. The brain-only matrix achieved the highest accuracy at 93.3%, with 14 out of 15 participants correctly identified. The spinal cord followed with 53.3% accuracy (8 correctly identified out of 15), while the brain-spine interaction block yielded an accuracy of 40% (6 out of 15).

Figure 4.

Dataset 3 fingerprinting using brain-only, spine-only, and brain–spine interaction as inputs. The identifiability matrices reflect the correlations across the participants’ runs, with participants’ IDs sorted by highest correlation in each case, leading to differing axis labels across matrices. Identification accuracies (chance level = 8.3%) are 93.3% for brain-only, 53.3% for spine-only, and 40% for the interaction.

Participants IDs in the matrices were sorted by decreasing correlation values within each component (brain-only, spine-only, and brain–spine), and, therefore, do not align across the three matrices. Nevertheless, certain individuals with high identifiability in the brain also performed well in the spine and brain–spine matrices; e.g., participants 1, 10, and 11. All three matrices exhibit a visible diagonal trend in the identifiability pattern, which is most pronounced in the brain matrix. For further details, the reader is addressed to Supplementary material.

We examined the residual correlations from linear regression models to assess their impact on subject identifiability. In the first model, where spinal cord time series served as the dependent variable and brain time series as the predictor , the residuals—representing spinal cord activity not linearly explained by brain activity—yielded an Idiff score of 0.07, with only 2 out of 15 participants correctly identified (accuracy = 13.3%). Conversely, in the inverse model, with brain time series as and spinal cord time series as , the residuals—indicating brain activity unexplained by spinal cord signals—produced a higher Idiff of 0.12 and improved identification, correctly identifying 8 out of 15 individuals (accuracy = 53.3%).

3. Discussion

Our findings demonstrate that a reliable and individually distinctive FC pattern from the (cervical) spinal cord – termed “spine-print” – can be identified across individuals in three different datasets. Despite differences in acquisition protocols and slight variations in preprocessing, participants’ identification remains well above chance, highlighting the feasibility and robustness of the spine-print. This suggests that, much like the brain, the spinal cord exhibits participant-specific FC that is reliably detectable.

A closer inspection of the spine-prints and the regions with the highest reliability reveals that the most consistent areas—those with the highest nodal strength—were the sensory regions, rather than the ventral regions where motor neurons reside. This could suggest that the sensory functions processed by the cord might be more subject-specific, while motor functions at rest are more uniform across individuals. In Dataset 3, we also assessed the identifiability scores of the sensory-motor (SM) network alone in relation to the spinal cord, allowing for a fair comparison between the two. Interestingly, when the SM network and spinal cord regions were combined, the identifiability scores increased notably (see Supplementary Material, Fig. S4).

In terms of correlations, the bilateral connection of the fasciculus gracilis (fg) emerged as the strongest across all three datasets. The fg carries fine touch, vibration, and proprioceptive afferents from the lower limbs and trunk through heavily myelinated axons. Sensory input from bilaterally symmetric body regions may lead to similar fluctuation patterns in both the left and right fasciculi, particularly during rest. However, it is important to acknowledge that many of the strong bilateral correlations observed across the datasets could be largely influenced by partial volume effects, given the small size and close proximity of these regions. Additionally, the findings in the dorsal areas could also be affected by the presence of the dorsal vein, potentially confounding the interpretation of BOLD signals in these regions. While the interpretation of BOLD signals in the white matter remains debated, there is growing evidence that white matter has sufficient vascularization to support hemodynamic changes. Several studies have investigated the reliability of functional information captured in the cerebral white matter (Wu et al. 2017; Peer et al. 2017; Huang et al. 2020; Ding et al. 2018; Gawryluk, Mazerolle, and D’Arcy 2014; Gore et al. 2019). White matter is largely composed of glial cells, which regulate homeostasis and support myelinated axons, and their metabolic processes can influence local blood flow and presumably influence the oxygenation demand of the WM. These non-neuronal fluctuations may explain the distinct slower dynamics of BOLD signals in white matter compared to gray matter. Recognizing these factors is essential for accurate interpretation of spinal cord fMRI results (Sengupta et al. 2024; Paquette, Piché, and Leblond 2021). In line with this, dynamic functional connectivity approaches have revealed functional components in the spinal cord white matter during rest, as shown by (Kinany et al. 2020).

Importantly, an individual-specific signature could be primarily shaped by anatomical features. Prior studies have shown that spinal cord functional patterns are closely aligned with its structural organization (Kinany et al. 2020; Sengupta et al. 2021; Ricchi, Kinany, and Van De Ville 2024), supporting the notion that inter-individual anatomical variability may give rise to detectable functional differences.

However, while this spine-print exists, its distinctiveness is notably weaker compared to that of the brain. This difference raises important questions about the factors influencing the strength of individual signatures in different parts of the central nervous system, which we discuss next.

One such factor could be the relative granularity of the parcellation used to define ROIs. Notably, the number of ROIs in Dataset 3 was kept relatively comparable between the brain and the spinal cord: the brain was divided into 119 ROIs, while the spinal cord included 98, derived from 14 cross-sectional regions across 7 spinal levels. Yet, despite this similarity in dimensionality, the physical sizes of these structures differ drastically (Parent and Carpenter 1996; Sherman, Nassaux, and Citrin 1990). Their volumes are and about , respectively, considering 8–10 cm of length for C1-C7 and a cross-section area of . This results in a volume ratio of ~118. The ROIs from the atlases used for each are on average ~227 times smaller for the spine than for the brain. As a result, regional signal averages in the spinal cord are expected to be inherently noisier, especially given the lower tSNR typically observed in spinal fMRI. These factors together help explain the comparatively lower fingerprinting performance observed in the spinal cord relative to the brain.

Beyond size and signal quality, brain and spine also have different functional roles. For brain fingerprinting, the regions that are most specific for an individual are those serving higher-order cognitive functions, while sensory regions provide less unique information (Amico and Goñi 2018; Finn et al. 2015; Lu et al. 2024; Griffa et al. 2022; Jo et al. 2021). The latter are evolutionarily more preserved, and, given that the spinal cord is an even more ancient structure, it might therefore be presumed to exhibit limited individual variability and, consequently, a diminished capacity for supporting a distinct “spine-print”. Yet, despite these expectations, our results reveal a measurable degree of individual specificity in spinal cord FC. While this spine-print may partly reflect intrinsic functional properties of the spinal cord, it may also be shaped by brain activity. This is supported by our regression analyses assessing the dependency between brain and spinal cord time courses. When brain activity was regressed out of the spinal cord signals—yielding residuals used for fingerprinting—the identifiability scores dropped substantially. In contrast, removing spinal cord activity from the brain signals had little effect: the identifiability score (Idiff) remained high at 0.12, identical to the original Idiff obtained from the full dataset. Notably, using only the brain time series resulted in an even higher Idiff score of 0.17. These findings suggest that the brain may act as the primary driver of spinal cord activity patterns relevant for fingerprinting, and that the spine-print may, in part, reflect an echo of brain-derived individuality.

4. Conclusion and outlook

In this study, we demonstrate the feasibility of identifying an individual-specific functional signature in the spinal cord—a “spine-print”—across two runs within the same scanning session. This finding supports the notion that participant-level identifiability is not exclusive to the brain and can extend to spinal cord activity. Interestingly, brain regions involved in sensorimotor functions—those more directly related to spinal cord activity—tend to exhibit lower identifiability scores compared to higher-order cognitive regions such as the prefrontal and frontoparietal cortex (Amico and Goñi 2018; Finn et al. 2015). This parallel may indicate that the reduced spine-print identifiability, relative to brain fingerprinting, reflects functional characteristics of sensorimotor systems more generally.

Future work should aim to explore the stability of this spine-print across sessions to determine whether it reflects a short-term phenomenon or a more persistent individual trait. However, this remains technically challenging. The spinal cord’s curvature is highly influenced by participant positioning and can vary significantly across sessions, posing challenges for accurate between-session image co-registration. To address this, an informative next step would involve scanning the same individual in two consecutive sessions with only a brief pause in between, during which the participant is temporarily removed from the scanner but remains positioned on the table—compared to a condition where the participant is repositioned entirely. This approach would allow for a more controlled assessment of acquisition-related variability, disentangled from repositioning effects.

Additionally, our findings highlight the potential role of the brain in shaping spinal cord activity. Given the observed interactions, future research should further investigate the dependency and directionality of brain–spine functional connectivity, which may yield new insights into hierarchical control mechanisms within the central nervous system.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Data acquisition for Dataset 1 was primarily supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants K99EB016689 and R21NS081437. Data processing was supported by NIH grants R00EB016689, R01EB027779 and R21EB031211. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Since January 2024, Dr. Barry has been employed by the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering at the NIH. This article was co-authored by Robert Barry in his personal capacity. The opinions expressed in the article are his own and do not necessarily reflect the views of the NIH, the Department of Health and Human Services, or the United States government.

This work was supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF), Project No. 205321_207493.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

- FC

functional connectivity

- ROI

region of interest

- ICC

inter cluster coefficient

- Idiff

identifiability score

- dh

dorsal horns

- Iz

intermediate zone

- vh

ventral horns

- cst

cortico-spinal tract

- fc

fasciculus cuneatus

- fg

fasciculus gracilis

- sl

spinal lemniscus

- VIS

visual network

- SM

somatomotor network

- DA

dorsal-attention network

- VA

ventral-attention network

- L

limbic network

- FP

fronto-parietal network

- DMN

default-mode network

- GM

gray matter

- WM

white matter

Data and Code Availability

Dataset 2 is publicly available, while Dataset 1 and 3 are available upon reasonable request to Dr. Robert Barry and Prof. Julien Doyon, respectively.

Code is publically available on the GitHub repository: https://github.com/MIPLabCH/SpinePrint.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Amico Enrico, and Goñi Joaquín. 2018. “The Quest for Identifiability in Human Functional Connectomes.” Scientific Reports 8 (1): 8254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry Robert L., Rogers Baxter P., Conrad Benjamin N., Smith Seth A., and Gore John C.. 2016. “Reproducibility of Resting State Spinal Cord Networks in Healthy Volunteers at 7 Tesla.” NeuroImage 133 (June):31–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry Robert L., and Smith Seth A.. 2019. “Measurement of T2* in the Human Spinal Cord at 3T.” Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 82 (2): 743–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behzadi Yashar, Restom Khaled, Liau Joy, and Liu Thomas T.. 2007. “A Component Based Noise Correction Method (CompCor) for BOLD and Perfusion Based fMRI.” NeuroImage 37 (1): 90–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D. V., and Sparrow S. A.. 1981. “Developing Criteria for Establishing Interrater Reliability of Specific Items: Applications to Assessment of Adaptive Behavior.” American Journal of Mental Deficiency 86 (2): 127–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen Jacob. 1992. “Statistical Power Analysis.” Current Directions in Psychological Science 1 (3): 98–101. [Google Scholar]

- Leener De, Benjamin Simon Lévy, Dupont Sara M., Fonov Vladimir S., Stikov Nikola, Collins D. Louis, Callot Virginie, and Cohen-Adad Julien. 2017. “SCT: Spinal Cord Toolbox, an Open-Source Software for Processing Spinal Cord MRI Data.” Neurolmage 145 (January):24–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demuru Matteo, and Fraschini Matteo. 2020. “EEG Fingerprinting: Subject-Specific Signature Based on the Aperiodic Component of Power Spectrum.” Computers in Biology and Medicine 120 (103748): 103748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding Zhaohua, Huang Yali, Bailey Stephen K., Gao Yurui, Cutting Laurie E., Rogers Baxter P., Newton Allen T., and Gore John C.. 2018. “Detection of Synchronous Brain Activity in White Matter Tracts at Rest and under Functional Loading.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 115 (3): 595–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubois Julien, and Adolphs Ralph. 2016. “Building a Science of Individual Differences from fMRI.” Trends in Cognitive Sciences 20 (6): 425–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enander Jonas M. D., Loeb Gerald E., and Jörntell Henrik. 2022. “A Model for Self-Organization of Sensorimotor Function: Spinal Interneuronal Integration.” Journal of Neurophysiology 127 (6): 1478–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finn Emily S., Shen Xilin, Scheinost Dustin, Rosenberg Monica D., Huang Jessica, Chun Marvin M., Papademetris Xenophon, and Constable R. Todd. 2015. “Functional Connectome Fingerprinting: Identifying Individuals Using Patterns of Brain Connectivity.” Nature Neuroscience 18 (11): 1664–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fornito Alex, Zalesky Andrew, and Bullmore Edward. 2016. Fundamentals of Brain Network Analysis. San Diego, CA: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fraschini Matteo, Demuru Matteo, Crobe Alessandra, Marrosu Francesco, Stam Cornelis J., and Hillebrand Arjan. 2016. “The Effect of Epoch Length on Estimated EEG Functional Connectivity and Brain Network Organisation.” Journal of Neural Engineering 13 (3): 036015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gawryluk Jodie R., Mazerolle Erin L., and D’Arcy Ryan C. N.. 2014. “Does Functional MRI Detect Activation in White Matter? A Review of Emerging Evidence, Issues, and Future Directions.” Frontiers in Neuroscience 8 (August):239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghaffari Amin, Zhao Yufei, Chen Xu, Langley Jason, and Hu Xiaoping. 2025. “Dynamic Fingerprinting of the Human Functional Connectome.” Neuroscience. bioRxiv. https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2025.02.20.637919v1.full. [Google Scholar]

- Glover G. H., Li T. Q., and Ress D.. 2000. “Image-Based Method for Retrospective Correction of Physiological Motion Effects in fMRI: RETROICOR.” Magnetic Resonance in Medicine: Official Journal of the Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine / Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 44 (1): 162–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gore John C., Li Muwei, Gao Yurui, Wu Tung-Lin, Schilling Kurt G., Huang Yali, Mishra Arabinda, et al. 2019. “Functional MRI and Resting State Connectivity in White Matter - a Mini-Review.” Magnetic Resonance Imaging 63 (November):1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grau James W. 2014. “Learning from the Spinal Cord: How the Study of Spinal Cord Plasticity Informs Our View of Learning.” Neurobiology of Learning and Memory 108 (February):155–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffa Alessandra, Amico Enrico, Liégeois Raphaël, Van De Ville Dimitri, and Preti Maria Giulia. 2022. “Brain Structure-Function Coupling Provides Signatures for Task Decoding and Individual Fingerprinting.” NeuroImage 250 (118970): 118970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallgren Kevin A. 2012. “Computing Inter-Rater Reliability for Observational Data: An Overview and Tutorial.” Tutorials in Quantitative Methods for Psychology 8 (1): 23–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Yali, Yang Yang, Hao Lei, Hu Xuefang, Wang Peiguang, Ding Zhaohua, Gao Jia-Hong, and Gore John C.. 2020. “Detection of Functional Networks within White Matter Using Independent Component Analysis.” NeuroImage 222 (117278): 117278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo Youngheun, Faskowitz Joshua, Esfahlani Farnaz Zamani, Sporns Olaf, and Betzel Richard F.. 2021. “Subject Identification Using Edge-Centric Functional Connectivity.” NeuroImage 238 (118204): 118204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaptan Merve, Horn Ulrike, Vannesjo S. Johanna, Mildner Toralf, Weiskopf Nikolaus, Finsterbusch Jürgen, Brooks Jonathan C. W., and Eippert Falk. 2023. “Reliability of Resting-State Functional Connectivity in the Human Spinal Cord: Assessing the Impact of Distinct Noise Sources.” NeuroImage 275 (120152): 120152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khatibi Ali, Vahdat Shahabeddin, Lungu Ovidiu, Finsterbusch Jurgen, Büchel Christian, Cohen-Adad Julien, Marchand-Pauvert Veronique, and Doyon Julien. 2022. “Brain-Spinal Cord Interaction in Long-Term Motor Sequence Learning in Human: An fMRI Study.” NeuroImage 253 (119111): 119111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinany Nawal, Landelle Caroline, De Leener Benjamin, Lungu Ovidiu, Doyon Julien, and Van De Ville Dimitri. 2024. “In Vivo Parcellation of the Human Spinal Cord Functional Architecture.” Imaging Neuroscience 2 (January):1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinany Nawal, Pirondini Elvira, Micera Silvestro, and Van De Ville Dimitri. 2020. “Dynamic Functional Connectivity of Resting-State Spinal Cord fMRI Reveals Fine-Grained Intrinsic Architecture.” Neuron 108 (3): 424–35.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinany N., Khatibi A., Lungu O., Finsterbusch J., Büchel C., Marchand-Pauvert V., Van De Ville D., Vahdat S., and Doyon J.. 2023. “Decoding Cerebro-Spinal Signatures of Human Behavior: Application to Motor Sequence Learning.” NeuroImage 275 (120174): 120174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong Wanzeng, Wang Luyun, Xu Sijia, Babiloni Fabio, and Chen Hang. 2019. “EEG Fingerprints: Phase Synchronization of EEG Signals as Biomarker for Subject Identification.” IEEE Access: Practical Innovations, Open Solutions 7:121165–73. [Google Scholar]

- Kong Yazhuo, Jenkinson Mark, Andersson Jesper, Tracey Irene, and Brooks Jonathan C. W.. 2012. “Assessment of Physiological Noise Modelling Methods for Functional Imaging of the Spinal Cord.” NeuroImage 60 (2): 1538–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowalczyk Olivia S., Medina Sonia, Tsivaka Dimitra, McMahon Stephen B., Williams Steven C. R., Brooks Jonathan C. W., Lythgoe David J., and Howard Matthew A.. 2024. “Spinal fMRI Demonstrates Segmental Organisation of Functionally Connected Networks in the Cervical Spinal Cord: A Test-Retest Reliability Study.” Human Brain Mapping 45 (2): e26600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landelle Caroline, Dahlberg Linda Solstrand, Lungu Ovidiu, Misic Bratislav, De Leener Benjamin, and Doyon Julien. 2023. “Altered Spinal Cord Functional Connectivity Associated with Parkinson’s Disease Progression.” Movement Disorders: Official Journal of the Movement Disorder Society 38 (4): 636–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landelle Caroline, Kinany Nawal, De Leener Benjamin, Murphy Nicholas D., Lungu Ovidiu, Marchand-Pauvert Véronique, Van De Ville Dimitri, and Doyon Julien. 2024. “Cerebro-Spinal Somatotopic Organization Uncovered through Functional Connectivity Mapping.” Imaging Neuroscience 2 (September):1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Kendrick, Wisner Krista, and Atluri Gowtham. 2021. “Feature Selection Framework for Functional Connectome Fingerprinting.” Human Brain Mapping 42 (12): 3717–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindquist Martin A., Geuter Stephan, Wager Tor D., and Caffo Brian S.. 2019. “Modular Preprocessing Pipelines Can Reintroduce Artifacts into fMRI Data.” Human Brain Mapping 40 (8): 2358–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Jiayu, Yan Tianyi, Yang Lan, Zhang Xi, Li Jiaxin, Li Dandan, Xiang Jie, and Wang Bin. 2024. “Brain Fingerprinting and Cognitive Behavior Predicting Using Functional Connectome of High Inter-Subject Variability.” NeuroImage 295 (120651): 120651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantwill Maron, Gell Martin, Krohn Stephan, and Finke Carsten. 2022. “Brain Connectivity Fingerprinting and Behavioural Prediction Rest on Distinct Functional Systems of the Human Connectome.” Communications Biology 5 (1): 261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margulies Daniel S., Ghosh Satrajit S., Goulas Alexandros, Falkiewicz Marcel, Huntenburg Julia M., Langs Georg, Bezgin Gleb, et al. 2016. “Situating the Default-Mode Network along a Principal Gradient of Macroscale Cortical Organization.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 113 (44): 12574–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martucci Katherine T., and Mackey Sean C.. 2018. “Neuroimaging of Pain: Human Evidence and Clinical Relevance of Central Nervous System Processes and Modulation.” Anesthesiology 128 (6): 1241–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGonigle D. J., Howseman A. M., Athwal B. S., Friston K. J., Frackowiak R. S., and Holmes A. P.. 2000. “Variability in fMRI: An Examination of Intersession Differences.” NeuroImage 11 (6 Pt 1): 708–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nim Casper Glissmann, Weber Kenneth Arnold, Kawchuk Gregory Neill, and O’Neill Søren. 2021. “Spinal Manipulation and Modulation of Pain Sensitivity in Persistent Low Back Pain: A Secondary Cluster Analysis of a Randomized Trial.” Chiropractic & Manual Therapies 29 (1): 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ossipov Michael H., Morimura Kozo, and Porreca Frank. 2014. “Descending Pain Modulation and Chronification of Pain.” Current Opinion in Supportive and Palliative Care 8 (2): 143–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paquette Thierry, Piché Mathieu, and Leblond Hugues. 2021. “Contribution of Astrocytes to Neurovascular Coupling in the Spinal Cord of the Rat.” The Journal of Physiological Sciences: JPS 71 (1): 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parent André, and Carpenter Malcolm B.. 1996. Carpenter’s Human Neuroanatomy. 9th ed. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins. https://search.worldcat.org/it/title/Carpenter’s-human-neuroanatomy/oclc/605177808. [Google Scholar]

- Peer Michael, Nitzan Mor, Bick Atira S., Levin Netta, and Arzy Shahar. 2017. “Evidence for Functional Networks within the Human Brain’s White Matter.” The Journal of Neuroscience: The Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience 37 (27): 6394–6407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Power Jonathan D., Barnes Kelly A., Snyder Abraham Z., Schlaggar Bradley L., and Petersen Steven E.. 2012. “Spurious but Systematic Correlations in Functional Connectivity MRI Networks Arise from Subject Motion.” NeuroImage 59 (3): 2142–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Power Jonathan D., Mitra Anish, Laumann Timothy O., Snyder Abraham Z., Schlaggar Bradley L., and Petersen Steven E.. 2014. “Methods to Detect, Characterize, and Remove Motion Artifact in Resting State fMRI.” NeuroImage 84 (January):320–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deshpande Rangaprakash & Barry Robert L.. 2021. “Variability of the Hemodynamic Response Function in the Healthy Human Cervical Spinal Cord at 3 Tesla.” In, 654. 29. Proceedings of the International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. [Google Scholar]

- Ricchi Ilaria, Kinany Nawal, and Van De Ville Dimitri. 2024. “Lumbosacral Spinal Cord Functional Connectivity at Rest: From Feasibility to Reliability.” Imaging Neuroscience 2 (September):1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sareen Ekansh, Zahar Sélima, Van De Ville Dimitri, Gupta Anubha, Griffa Alessandra, and Amico Enrico. 2021. “Exploring MEG Brain Fingerprints: Evaluation, Pitfalls, and Interpretations.” NeuroImage 240 (118331): 118331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer Alexander, Kong Ru, Gordon Evan M., Laumann Timothy O., Zuo Xi-Nian, Holmes Avram J., Eickhoff Simon B., and Yeo B. T. Thomas. 2018. “Local-Global Parcellation of the Human Cerebral Cortex from Intrinsic Functional Connectivity MRI.” Cerebral Cortex (New York, N.Y.: 1991) 28 (9): 3095–3114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seitzman Benjamin A., Gratton Caterina, Marek Scott, Raut Ryan V., Dosenbach Nico U. F., Schlaggar Bradley L., Petersen Steven E., and Greene Deanna J.. 2020. “A Set of Functionally-Defined Brain Regions with Improved Representation of the Subcortex and Cerebellum.” NeuroImage 206 (116290): 116290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sengupta Anirban, Mishra Arabinda, Wang Feng, Chen Li Min, and Gore John C.. 2024. “Characteristic BOLD Signals Are Detectable in White Matter of the Spinal Cord at Rest and after a Stimulus.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 121 (22): e2316117121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sengupta Anirban, Mishra Arabinda, Wang Feng, Li Muwei, Yang Pai-Feng, Chen Li Min, and Gore John C.. 2021. “Functional Networks in Non-Human Primate Spinal Cord and the Effects of Injury.” Neurolmage 240 (118391): 118391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman J. L., Nassaux P. Y., and Citrin C. M.. 1990. “Measurements of the Normal Cervical Spinal Cord on MR Imaging.” AJNR. American Journal of Neuroradiology 11 (2): 369–72. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castanheira Silva, da Jason, Orozco Perez Hector Domingo, Misic Bratislav, and Baillet Sylvain. 2021. “Brief Segments of Neurophysiological Activity Enable Individual Differentiation.” Nature Communications 12 (1): 5713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder Abraham Z., and Raichle Marcus E.. 2012. “A Brief History of the Resting State: The Washington University Perspective.” NeuroImage 62 (2): 902–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues Souza, de Júlia, Ribeiro Fernanda Lenita, Sato João Ricardo, Mesquita Rickson Coelho, and Júnior Claudinei Eduardo Biazoli. 2019. “Identifying Individuals Using fNIRS-Based Cortical Connectomes.” Biomedical Optics Express 10 (6): 2889–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sporns Olaf, Tononi Giulio, and Kötter Rolf. 2005. “The Human Connectome: A Structural Description of the Human Brain.” PLoS Computational Biology 1 (4): e42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenner Max-Philipp, Nossa Cindy Márquez, Zaehle Tino, Azañón Elena, Heinze Hans-Jochen, Deliano Matthias, and Büntjen Lars. 2025. “Prior Knowledge Changes Initial Sensory Processing in the Human Spinal Cord.” Science Advances 11 (3): eadl5602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tinnermann Alexandra, Büchel Christian, and Haaker Jan. 2021. “Observation of Others’ Painful Heat Stimulation Involves Responses in the Spinal Cord.” Science Advances 7 (14): eabe8444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobyne Sean M., Somers David C., Brissenden James A., Michalka Samantha W., Noyce Abigail L., and Osher David E.. 2018. “Prediction of Individualized Task Activation in Sensory Modality-Selective Frontal Cortex with ‘Connectome Fingerprinting.’“ NeuroImage 183 (December):173–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tripathi Vaibhav, and Somers David C.. 2023. “Predicting an Individual’s Cerebellar Activity from Functional Connectivity Fingerprints.” NeuroImage 281 (120360): 120360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vahdat Shahabeddin, Lungu Ovidiu, Cohen-Adad Julien, Marchand-Pauvert Veronique, Benali Habib, and Doyon Julien. 2015. “Simultaneous Brain-Cervical Cord fMRI Reveals Intrinsic Spinal Cord Plasticity during Motor Sequence Learning.” PLoS Biology 13 (6): e1002186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van De Ville Dimitri, Farouj Younes, Preti Maria Giulia, Liégeois Raphaël, and Amico Enrico. 2021. “When Makes You Unique: Temporality of the Human Brain Fingerprint.” Science Advances 7 (42): eabj0751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Virtanen Pauli, Gommers Ralf, Oliphant Travis E., Haberland Matt, Reddy Tyler, Cournapeau David, Burovski Evgeni, et al. 2020. “SciPy 1.0: Fundamental Algorithms for Scientific Computing in Python.” Nature Methods 17 (3): 261–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolpaw J. R. 2007. “Spinal Cord Plasticity in Acquisition and Maintenance of Motor Skills.” Acta Physiologica (Oxford, England) 189 (2): 155–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Zhao-Min, Bralten Janita, Cao Qing-Jiu, Hoogman Martine, Zwiers Marcel P., An Li, Sun Li, et al. 2017. “White Matter Microstructural Alterations in Children with ADHD: Categorical and Dimensional Perspectives.” Neuropsychopharmacology: Official Publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology 42 (2): 572–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeo B. T. Thomas, Krienen Fenna M., Sepulcre Jorge, Sabuncu Mert R., Lashkari Danial, Hollinshead Marisa, Roffman Joshua L., et al. 2011. “The Organization of the Human Cerebral Cortex Estimated by Intrinsic Functional Connectivity.” Journal of Neurophysiology 106 (3): 1125–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Dataset 2 is publicly available, while Dataset 1 and 3 are available upon reasonable request to Dr. Robert Barry and Prof. Julien Doyon, respectively.

Code is publically available on the GitHub repository: https://github.com/MIPLabCH/SpinePrint.