Abstract

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a psychiatric disorder caused by traumatic past experiences, rooted in the neurocircuits of fear memory formation. Memory processes include encoding, storing, and recalling to forgetting, suggesting the potential to erase fear memories through timely interventions. Conventional strategies such as medications or electroconvulsive therapy often fail to provide permanent relief and come with significant side-effects. This review explores how fear memory may be erased, particularly focusing on the mnemonic phases of reconsolidation and extinction. Reconsolidation strengthens memory, while extinction weakens it. Interfering with memory reconsolidation could diminish the fear response. Alternatively, the extinction of acquired memory could reduce the fear memory response. This review summarizes experimental animal models of PTSD, examines the nature and epidemiology of reconsolidation to extinction, and discusses current behavioral therapy aimed at transforming fear memories to treat PTSD. In sum, understanding how fear memory updates holds significant promise for PTSD treatment.

Keywords: Post-traumatic stress disorder, Fear memory, Reconsolidation, Extinction, Engram

A Synopsis of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

PTSD

PTSD is a psychiatric condition characterized by intense fear and memories stemming from past traumatic experiences. It affects ~3.9% of the global population over their lifetime, with rates rising to 5.6% among trauma victims [1] and exceeding 15% among global pandemic survivors [2]. Women are twice as susceptible as men [3]. The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has exacerbated PTSD symptoms worldwide [4, 5], highlighting significant challenges for existing mental health systems [6, 7]. Exposure therapy (ET) is a first-line treatment that facilitates fear memory extinction by safely exposing individuals to traumatic memories [8, 9]. However, this psychotherapy fails to expel fear memories permanently, leading to recurrence and treatment non-completion [10–13]. Given the substantial increase in its prevalence following the COVID-19 pandemic [4, 5], effective management of PTSD, which requires extensive time and professional management, poses significant challenges [11]. Thus, developing more efficient therapeutic strategies urgently requires a deeper understanding of fear memory mechanisms and effective interventions to alleviate the symptoms of PTSD.

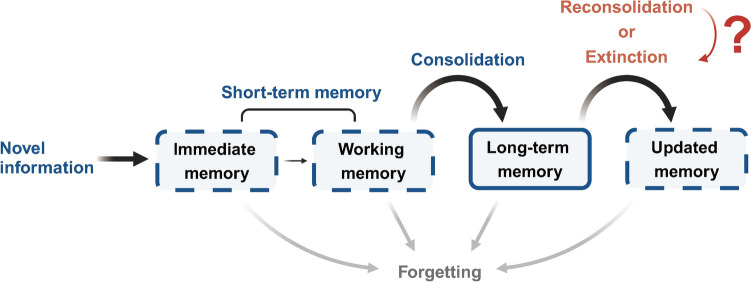

Memory is a dynamic neurophysiological process that retrieves learned information through associative mechanisms [14, 15]. It is widely accepted to involve several stages: encoding, storing, recalling, and forgetting [15] (Fig. 1). Initially, newly-acquired information is encoded rapidly, with immediate memory fading quickly without rehearsal. Reviewing this information helps stabilize memory temporarily against external interference. Short-term memory, crucial for establishing long-term memory, lasts minutes to hours and encompasses immediate and working memory [16]. The process by which newly-encoded memories stabilize over time is termed “consolidation” [17]. As memory consolidates, it becomes resistant to disruption, transforming into long-term memory, which can persist for months [18, 19]. It was broadly agreed that memory consolidation followed a linear progression [20–22] until Prof. Nader introduced the concept of “reconsolidation”, where memories can be reactivated and updated without re-exposure to the original learning environment [23]. Re-exposure to a conditioned stimulus (CS) can either reinforce fear memory retention or facilitate extinction, where a previously unsafe context no longer provokes a fear response [24, 25]. Ideally, memories should be preserved at a level that retains knowledge of threats without negatively affecting mental well-being [26, 27]. Failure to achieve this balance may lead to anxiety and other psychiatric disorders, including PTSD [28, 29]. Current psychotherapies of PTSD often focus on deactivating or impairing strong emotional memories, such as traumatic memories [30, 31]. Recent research on fear memory extinction within the reconsolidation window, known as the “retrieval-extinction protocol”, shows promise in rapidly eliminating fear memories [32, 33]. However, mixed results highlight challenges in achieving consistent outcomes [34–37]. The balance between reconsolidation and extinction processes during memory retrieval is unpredictable [38].

Fig. 1.

A schematic overview of memory simply includes short-term memory (STM), long-term memory (LTM), and updated memory. When new information is learned, it initially forms immediate memory, which lasts for a few minutes and can be extended through review, turning into working memory. Both immediate- and working-memory are termed STM since they are transient. LTM is established through consolidation, making memories more resistant to alterations. Processes like reconsolidation or extinction can update LTM by modifying original memories with new associations. Memories eventually fade if not reinforced. Unstable forms of memories are presented with dashed lines

In this review, we discuss the fundamental aspects of memory reconsolidation and extinction, focusing on the retrieval-extinction protocol and its potential clinical applications. We highlight its relevance for understanding memory modification and its implications for targeting maladaptive memories, particularly those associated with fear and trauma-related disorders [39, 40].

Experimental Models of Fear Conditioning

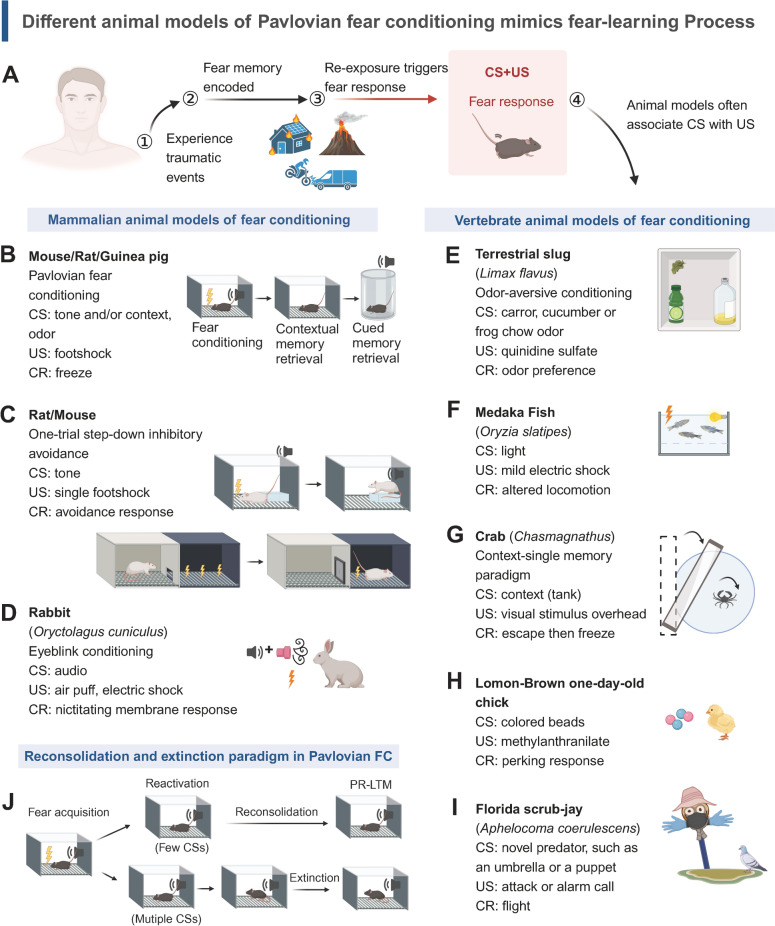

To understand the mechanisms of memory reconsolidation and extinction, we study them in experimental paradigms. Scientists have developed classical paradigms to study learning and memory, the classical conditioning pioneered by Ivan Pavlov being foundational [16, 41] (Fig. 2). Pavlov paired a neutral stimulus (CS), like a bell, with an unconditioned stimulus (US), such as food, to elicit a conditioned response (CR), like salivation. This laid the groundwork for studying neuronal mechanisms linking two events, predicting CS outcomes based on the US in specific contexts.

Fig. 2.

Diagrams of experimental animal models for Pavlovian fear conditioning. A Traumatic memories, such as experiencing a fire, a volcano erupting, or a car accident, are stored and retrieved upon re-exposure, forming associative learning processes studied in animal models. These experiments combine CS and US to induce fear responses in various mammalian and vertebrate subjects. B-I Different animal models of fear conditioning. J An overview of memory reconsolidation and extinction paradigms in the Pavlovian FC paradigm. After the fear acquisition, rodents are re-exposed to CSs in the training context to initiate either memory reconsolidation or extinction retrieval. They are then tested for memory retention in post-reactivation long-term tests (often performed 24 h after reactivation)

Classical fear conditioning, also known as Pavlovian fear conditioning (FC), pairs a CS (e.g., tone, odor, context) with a US (e.g., electric shock), to elicit a fear response [42]. In rodents, fear is shown through freezing in response to unexpected shocks, and memory is assessed by freezing duration during conditioning trials (Fig. 2B). Auditory or contextual fear conditioning (CFC) uses tone or context as the CS paired with the US to study different fear memory forms [43–47]. The one-trial step-down inhibitory avoidance (IA) paradigm measures fear-motivated learning by having rodents avoid electric shocks on a grid floor, with step-down latencies indicating IA memory retention [48–50]. Another paradigm, step-through avoidance (Fig. 2C), tests fear memory by measuring the latency to enter a dark box after experiencing shocks [51]. In the context-single memory (CSM) paradigm, crabs are put in a training context and exposed to an overhead visual danger stimulus (VDS), driving them to escape from the visual cue (Fig. 2G). With repeated VDS presentations, crabs develop a strong freezing response instead of escaping [52]. Successful training paradigms enable subjects to associate cues with aversive events, assessed by the degree of freezing, startle reflex, or locomotor activity [53, 54]. Classical fear conditioning has been widely studied across species, from mammals to birds and invertebrates (Fig. 2B-I) [55–61].

In studies of memory reconsolidation and extinction, researchers apply various manipulations during memory retrieval to induce different memory outcomes (Fig. 2J). In Pavlovian FC, the number of CSs presented during retrieval determines whether memory reconsolidation or extinction occurs [62–65]. CFC involves reactivating fear memories in the original or novel context to elicit reconsolidation or extinction, respectively [66, 67]. Some studies reintroduce animals into a novel context for a short duration each day, but this exposure lasts for several consecutive days [68, 69]. Other experiments also vary the number of CSs during retrieval to define reconsolidation or extinction [64–70]. Similarly, in the IA paradigm, subjects are exposed to the training chamber for distinct lengths of time to define two memory forms [71].

Introduction of Reconsolidation and Extinction

This review aims to discuss the retrieval-extinction protocol as an alternative therapy for PTSD treatment. To begin with, we explore the origins and mechanisms underlying memory reconsolidation and extinction, with a focus on their neuronal and molecular profiles. Examining the interplay between these processes provides insights into how memories are modified and regulated over time. Specifically, we explore the neuronal and molecular mechanisms involved in reconsolidation and extinction, integrating experimental evidence from animal models and human fMRI. In this aspect, we seek to contribute to a deeper understanding of memory dynamics and their implications for therapeutic interventions.

Memory Reconsolidation: Origins, Mechanisms, and fMRI Insights

Over a century ago, Müller introduced the term “Konsolidierung” to describe the phase when memories become resistant to interference [17]. They found that interventions following training could impair memory recall, while subsequent recall improved retrieval. Later, Misanin’s research discovered that delivering an electroconvulsive shock (ECS) to fear-conditioned rats after CS exposure induces amnesia [20]. His findings revealed the concept of “reconsolidation”. Reconsolidation, unlike consolidation, is a dynamic process that updates retrieved memories with new protein synthesis. Studies have shown that reconsolidation occurs more quickly and is more susceptible to amnesia than consolidation [72], emphasizing its role in memory modification and maintenance.

Reconsolidation challenges the traditional view of memories as static and unchangeable, suggesting that they are dynamic and can be modified. It occurs during memory retrieval, stabilizing recalled memories in a time-sensitive manner, which is crucial for interventions aimed at reducing fear of memories. Research shows that amnesic agents can disrupt reactivated memories when administered 6 h post-retrieval [73], while treatments before or up to 4 h after retrieval leave fear responses intact [18, 74]. This highlights a reconsolidation window, typically between 0.5 and 6 h post-retrieval, during which memories are more susceptible to modification [75]. Moreover, interventions applied strategically during reconsolidation have been shown to improve retention performance [76, 77]. These findings are key for developing PTSD therapies that target existing memories during this malleable phase.

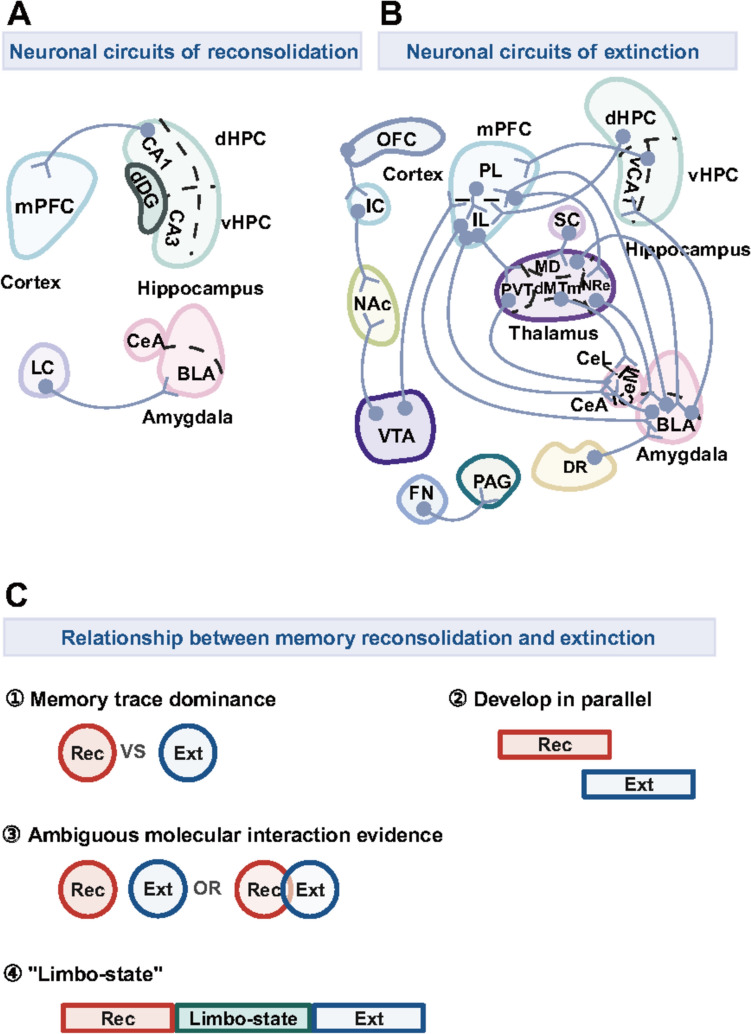

Understanding how different brain areas interact during memory reconsolidation is crucial for developing therapeutic approaches to disorders like PTSD, where eliminating the fear of memories is key. Several brain regions, particularly the amygdala and hippocampus, play central roles in memory updating and reconsolidation by reorganizing neuronal circuits [78], as shown in Table 1. The amygdala has been extensively studied for its role in the encoding, expression, extinction, and updating of fear memories. Its central region (CeA) plays a key role in encoding salient-specific valence [79]. In addition, the basolateral nucleus of the amygdala (BLA) is responsible not only for processing both positive and negative stimuli [80] but also for storing memory [81]. Despite extensive investigations using lesion and pharmacological approaches, the neuronal mechanisms underlying the amygdala’s involvement in reconsolidation remain inadequately understood. To illustrate, pharmacological inhibition of Thy1-expressing neurons in the BLA [51], or disrupting noradrenergic projections from the locus coeruleus to the BLA can block fear memory reconsolidation [82]. Correspondingly, the hippocampus, crucial for episodic memory and emotional behaviors [83–85], also plays a significant role in reconsolidation [86]. Memory destabilization reduces neuronal activity in regions like CA1, and CA3, and optogenetic inhibition of CA1 during retrieval can cause memory failure [87]. Blocking the projection from the dorsal hippocampus to prelimbic regions of the medial prefrontal cortex (dHPC-mPFC) before retrieval also prevents reconsolidation [88]. Interestingly, identical neuronal populations across distinct brain regions can produce opposing effects. Optogenetic activation of the dorsal dentate gyrus (dDG) during recall blocks memory reconsolidation [66], whereas pharmacological inhibition of the lateral neocortex before re-exposure to the CS achieves a similar result [89]. This discrepancy suggests that diverse populations of neurons, such as CaMKII+ neurons (Ca2+-calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II-positive neurons), play various roles in CFC. However, research on neuronal circuits and the roles of specific neuron types during reconsolidation remains limited (Fig. 3A). Thus, there is a critical need for further studies to prioritize and explore this area.

Table 1.

Molecular mechanisms of memory reconsolidation

| Paradigm | Species | Brain areas | Drug administration | Effect | References | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Target | Classification | Drug | Time | Within-session recon. | Recon. retention | ||||

| Pavlovian FC | Sprague-Dawley rat | Systemic | Protein synthesis | Inhibitor | ANI | Post-retrieval | ↓ | ↓ | [193] |

| Wistar rat | CXM | ↓ | ↓ | [194] | |||||

| Sprague-Dawley rat | ACC | Protein synthesis | Inhibitor | ANI | Post-retrieval | ↓ | ↓ | [195] | |

| LA | CXM | – | ↓ | [196] | |||||

| Lister rat | Systemic | β-adrenergic receptor | Antagonist | Propranolol | Post-retrieval | – | ↓ | [197] | |

| Amygdala | – | ↓ | |||||||

| Sprague-Dawley rat | Systemic | NMDA-R | Partial agonist | DCS | Post-retrieval | – | ↓ | [198] | |

| Amygdala | – | ↑ | |||||||

| Systemic | Noncompetitive receptor antagonist | MK-801 | Pre-retrieval | – | ↑ | ||||

| Wistar rat | Systemic | Glucocorticoid receptor | Antagonist | RU38486 | Post-retrieval | No effect | ↓ | [199] | |

| Sprague-Dawley rat | BLA | RU486 | – | ↓ | [74] | ||||

| 6 h post-retrieval | – | No effect | |||||||

| LA | AMPA-R | Blocker | NASPM | Post-retrieval | – | ↓ | [200] | ||

| ERK-MARK signaling pathway | Inhibitor | U0126 | Post-retrieval | – | ↓ | [196] | |||

| C57BL/6 mouse | Systemic | MEK signaling pathway | Inhibitor | SL327 | Post-retrieval | – | ↓ | [201] | |

| ERK1 mutant mouse | |||||||||

| BLA | Protein kinase A | Activator | 6-BNZ-cAMP | Post-retrieval | – | ↑ | [202] | ||

| Inhibitor | Rp-cAMPS | – | ↓ | ||||||

| C57BL/6 mouse | Systemic | mTOR | Selective inhibitor of mTOR kinase | Rapamycin | Post-retrieval | ↓ | ↓ | [203] | |

| 12 h post-retrieval | ↓ | – | |||||||

| 24 h post-retrieval | No effect | – | |||||||

| Sprague-Dawley rat | BLA | NF-κB signaling pathway | Direct inhibitor of NF-κB DNA-binding complex | SN50 | Pre-retrieval | No effect | ↓ | [204] | |

| IKK inhibitor | SSZ | Post-retrieval | No effect | ↓ | |||||

| CeA | IKK inhibitor | SSZ | No effect | No effect | |||||

| BLA | Rac | Inhibitor | NSC23766 | Post-retrieval | ↓ | – | [205] | ||

| CeA | No effect | – | |||||||

| CA1 | No effect | – | |||||||

| C57BL/6 mouse | Systemic | HDAC | Inhibitor | VPA | 90 s pre-retrieval | No effect | ↑ | [76] | |

| Sprague-Dawley rat | LA | HDAC | Inhibitor | TSA | 1 h post-retrieval | ↑ | – | [77] | |

| DNMT | Inhibitor | 5-AZA | ↓ | – | |||||

| RG108 | ↓ | – | |||||||

| mRNA synthesis | Inhibitor | α-Amanitin | Post-retrieval | No effect | ↓ | [206] | |||

| Arc/Arg3.1 early gene | Antisense | ODNs | 1 d post-conditioning | No effect | ↓ | [207] | |||

| C57BL/6 mouse | BLA | Actin filament | Arrest | Phalloidin | 0.5 h post-retrieval | ↓ | – | [75] | |

| 6 h post-retrieval | ↓ | – | |||||||

| 24 h post-retrieval | No effect | – | |||||||

| CFC | C57BL/6 mouse | Systemic | Protein synthesis | Inhibitor | ANI | Post-retrieval | ↓ | – | [208] |

| dHPC | ↓ | – | |||||||

| ACC | – | – | |||||||

| Wistar rat | CA1 | – | ↓ | [209] | |||||

| Long-Evans rat | Amygdala | Protein synthesis | Inhibitor | ANI | Post-retrieval | – | ↓ | [210] | |

| Wistar/ST rat | Systemic | NMDA-R | Partial agonist | DCS | Post-retrieval | – | ↑ | [211] | |

| C57BL/6 mouse | Systemic | Noncompetitive receptor antagonist | MK-801 | Post-retrieval | – | ↓ | [212] | ||

| Lister rat | dHPC | Antagonist | D-AP5 | Post-retrieval | ↓ | ↓ | [213] | ||

| C57BL/6 mouse | Systemic | AMPA-R | Potentiator | PEPA | Pre-retrieval | No effect | No effect | [214] | |

| BLA | |||||||||

| Wistar rat | NR | N2A-containing receptor | Antagonist | TCN-201 | Post-retrieval | – | ↓ | [215] | |

| Systemic | CB1/2 receptor | Inhibitor | WIN55,212-2 | Post-retrieval | No effect | – | [209] | ||

| Amygdala | CB1 receptor | Antagonist | AM251 | Post-retrieval | – | ↓ | [216] | ||

| CA1 | ↑ | ↑ | [217] | ||||||

| CB1 receptor | Antagonist | AEA | ↓ | – | |||||

| Systemic | GABAA receptor | Agonist | MDZ | Post-retrieval | – | ↓ | [218] | ||

| Sprague-Dawley rat | Systemic | GABAA receptor | Partial agonist | Flumazenil | Post-retrieval | – | ↓ | [219] | |

| Wistar rat | NR | GABAA receptor | Agonist | Muscimol | Post-retrieval | – | ↓ | [215] | |

| C57BL/6 mouse | Systemic | H3 receptor | Inverse agonist | Thioperamide | Post-retrieval | – | No effect | [212] | |

| Female C57BL/6 mouse | Pitolisant | Post-retrieval | No effect | – | [220] | ||||

| Wistar rat | Amygdala | H3 receptor | Antagonist | Thioperamide | Post-retrieval | – | – | [216] | |

| CA1 | 5-HT5A receptor | Antagonist | SB-699551 | Post-retrieval | – | No effect | [209] | ||

| 3 h post-retrieval | – | ↓ | |||||||

| 5-HT6 receptor | Antagonist | SB-271046 | Post-retrieval | – | No effect | ||||

| 3 h post-retrieval | – | No effect | |||||||

| Agonist | WAY-208466 | Post-retrieval | – | No effect | |||||

| 3 h post-retrieval | – | ↓ | |||||||

| 5-HT7 receptor | Antagonist | SB-269970 | Post-retrieval | – | No effect | ||||

| 3 h post-retrieval | – | ↑ | |||||||

| Agonist | AS-19 | Post-retrieval | – | No effect | |||||

| 3 h post-retrieval | – | No effect | |||||||

| Amygdala | Muscarinic receptor | Antagonist | Scopolamine | Post-retrieval | – | – | [216] | ||

| Sprague-Dawley rat | Systemic | NF-κB signaling pathway | Inhibitor | DDTC | Post-retrieval | ↓ | ↓ | [221] | |

| Lister rat | dHPC | MEK-ERK cascade pathway | Inhibitor | SSZ | Pre-retrieval | ↓ | ↓ | [213] | |

| IKK-NF-κB signaling pathway | Inhibitor | U0126 | No effect | No effect | |||||

| CA1 | IL-1 receptor signaling pathway | Endogenous IL-1 antagonist | IL-1ra | Post-retrieval | ↓ | ↓ | [222] | ||

| Long-Evans rat | Amygdala | CaMKII signaling pathway | Inhibitor | Myr-AIP | Post-retrieval | No effect | ↑ | [95] | |

| C57BL/6 mouse | dHPC | AMPAR endocytosis | Blocker | TAT-GluA23Y | 1 h pre-retrieval | ↑ | - | [223] | |

| 15 min post-retrieval | ↑ | – | |||||||

| 1 d post-retrieval | ↑ | – | |||||||

| Wistar rat | PL | Protein kinase C activity | Estrogen receptor modulator | Tamoxifen | Post-retrieval | ↓ | ↓ | [67] | |

| 6 h post-retrieval | No effect | ↓ | |||||||

| ACC | Post-retrieval | No effect | ↓ | ||||||

| 6 h post-retrieval | No effect | ↓ | |||||||

| PL | PKMζ inhibition | Inhibitor | Chelerythrine | Post-retrieval | ↓ | ↓ | [224] | ||

| ZIP | 1 h post-retrieval | ↓ | ↓ | ||||||

| Sprague-Dawley rat | BLA | Rac | Inhibitor | NSC23766 | Post-retrieval | No effect | – | [205] | |

| CeA | No effect | – | |||||||

| CA1 | ↓ | – | |||||||

| Long-Evans rat | Amygdala | mRNA | Inhibitor | ACT-D | Post-retrieval | No effect | No effect | [210] | |

| C57BL/6 mouse | Systemic | mTOR | Selective inhibitor of mTOR kinase | Rapamycin | Post-retrieval | ↓ | ↓ | [225] | |

| BLA | Actin filament | Arrest | Phalloidin | 0.5 h post-retrieval | ↓ | – | [75] | ||

| 6 h post-retrieval | No effect | – | |||||||

| 24 h post-retrieval | No effect | – | |||||||

| Wistar rat | BLA | Sodium channel | Blocker | TTX | Post-retrieval | – | ↓ | [216] | |

| 96 h post-retrieval | ↓ | – | [226] | ||||||

| NBM | No effect | – | |||||||

| ENT | ↓ | ↓ | [227] | ||||||

| Systemic | Ca2+ signaling pathway | Inhibitor | PD150606 | Post-retrieval | – | ↓ | [228] | ||

| C57BL/6 mouse | dHPC | Inhibitor | ALLN | Post-retrieval | – | ↓ | [229] | ||

| Lister rat | dHPC | Zif268 | ASO | Zif268-ODN | Pre-retrieval | ↓ | ↓ | [222] | |

| BDNF | BDNF-ODN | 1.5 h pre-training | ↓ | ↓ | |||||

| Sequential FC | C57BL/6 mouse | Systemic | β1-adrenergic receptor | Antagonist | Propranolol | Post-US retrieval | No effect | ↓ | [96] |

| Betaxolol | – | ↓ | |||||||

| NMDA | Antagonist | APV | Post-US retrieval | – | ↑ | ||||

| IA | Wistar rat | Systemic | Glucocorticoid receptor | Antagonist | RU38486 | Post-retrieval | ↓ | ↓ | [199] |

| Hippocampus | ↓ | ↓ | |||||||

| Sprague-Dawley rat | Systemic | mTOR | Inhibitor | Rapamycin | Post-retrieval | – | ↓ | [230] | |

| PL | – | ↓ | |||||||

| IL | – | ↑ | |||||||

Recon, reconsolidation; ACC, anterior cingulate cortex; IL, infralimbic region of medial prefrontal cortex; LA, lateral amygdala; CeA, central amygdala; CA1, a subregion of hippocampus; NR, nucleus reuniens; NBM, nucleus basalis magnocellularis; ENT, entorhinal cortex; NMDA-R, N-methyl-D-aspartic acid receptor; AMPA-R, α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid receptor; BDNF, brain-derived neurotrophic factor; ERK-MAPK signaling pathway, extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK)—mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathway; MEK signaling pathway, mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway, mTOR, mechanistic target of rapamycin signaling pathway; NF-κB signaling pathway, nuclear factor kappa-B signaling pathway; IKK-NF-κB signaling pathway, IκB kinase-nuclear factor kappa-B signaling pathway; IL-1, interleukin-1; CaMKII, Ca2+-calmodulin (CaM)-dependent protein kinase II; PKMζ, protein kinase M zeta; ASO, antisense oligonucleotides; ACT-D, actinomycin-D; AEA, anandamide; ALLN, N-Acetyl-Leu-Leu-norleucinal; AM251, N-(piperidin-1-yl)-5-(4-iodophenyl)-1-(2, 4-dichlorophenyl)-4-methyl-1H-pyrazole-3-carboxamide; ANI, anisomycin; APV, aminophosphonovaleric acid; CXM, cycloheximide; D-AP5, D-2-Amino-5-phosphovaleric acid; DCS, D-Cycloserine; DDTC, diethyldithiocarbamate; DRB, 5,6-dichloro-1-b-d-ribofuranosylbenzimidazole; MDZ, midazolam; MK-801, dizocilpine; myr-AIP, myristoylated autocamtide-2 related inhibitory peptide; NASPM, 1-naphthylacetylsperimine; ODNs, antisense oligodeoxynucleotides; PEPA, 4-[2-(phenylsulfonylamino)ethylthio]-2,6-difluorophenoxyacetamide; Rac, Ras-related C3 botulinum toxin substrate; Rp-cAMPS, Rp-adenosine 3’,5’-cyclic monophosphorothioate; RG108, N-Phthalyl-L-Tryptophan; SSZ, sulfasalazine; TAT-GluA23Y, HIV TAT-fused GluA2-derived C-terminal peptide; TCN-201, fluoro-N-[4-[[2-(phenylcarbonyl)hydrazino]carbonyl]benzyl]benzenesulphonamide; TSA, trichostatin A; TTX, tetrodotoxin; VPA, valproic acid; ZIP, zeta inhibitory peptide; 5-AZA, 5-AZA-2’-deoxycytidine; 5-HT, serotonin; 6-BNZ-cAMP, N6-benzoyladenosine-3’,5’-cyclic monophosphate

Fig. 3.

Conceptual diagrams of the neuronal circuits of reconsolidation and extinction, as well as their relationship. A Neuronal circuits of reconsolidation mainly involve the cortex, amygdala, and hippocampus. B Neuronal circuits of extinction form a cooperative network across the brain. C (1). Memory trace dominance theory implies a competitive mechanism between reconsolidation and extinction. (2). Nader et al. and Pérez-Cuesta et al. indicate that extinction does not prevent reconsolidation, suggesting dual memory periods may develop in a counterbalanced manner. (3). Molecular evidence regarding reconsolidation and extinction remains unclear from previous studies. (4). The linear memory assumption posits a distinct and resilient period between reconsolidation and extinction of memories. (Rec, Reconsolidation; Ext, Extinction.)

When fear memories are retrieved, increased expression of immediate-early genes like Zif268, Arc, and c-Fos is evident in key brain regions, such as the hippocampus, the amygdala, and the nucleus accumbens (NAc) [90–93]. Genetic studies have shown that serum- and glucocorticoid-induced kinase 3 expression is elevated following retrieval and phosphorylation of GluA1 at Ser831 and Ser845 in the amygdala, hippocampus, and mPFC [94]. Activation markers of proteasome-dependent protein degradation, such as the Lys48-linked poly-ubiquitin chain, also increase following fear memory retrieval [50]. Reactivated fear memories also induce the phosphorylation of CREB and Rpt6-S120, and upregulate proteasome activity in the amygdala and hippocampus [91, 95, 96]. Research on memory reconsolidation often applies pharmacological manipulation targeting diverse receptors or signaling pathways by specific inhibitors or agonists to disrupt the reactivated memory phase. It possesses unique molecular profiles across brain regions, such as CREB-mediated transcription, intracellular signaling pathways, neurotransmitters, or some second messengers (Table 1). For further details, refer to high-profile reviews in the field [97].

Consistent with evidence from rodents, functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) in both healthy subjects and traumatized patients establishes that reconsolidation also requires the cooperation of multiple cerebral areas, notably the amygdala and hippocampus (Table 2). Increasing amygdaloid activity during fear memory retrieval suggests that it predicts fear expression and the activation of fear-related circuits [39]. The hippocampus is responsible for the modification of fear memories during re-exposure, particularly responding to unpredicted reminders associated with the original fear learning context [98]. In declarative tasks, hippocampal activity significantly increases when subjects encounter unpredictable syllable cues, aligning with patterns found during memory reactivation. fMRI studies also highlight a coactivated network involving the midline anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), insular cortex (IC), or amygdala-hippocampus circuit, when addressing dysfunctional fear memories [39]. Enhanced activity in regions like the IC, thalamus, parahippocampal gyrus, and mid-frontal gyri potentially contribute to alleviating the overwhelming stress in traumatized patients following treatments that impair reconsolidation, such as propranolol-induced interventions [99].

Table 2.

Human fMRI evidence of memory reconsolidation

| Paradigm | Subjects | Anatomical structure | Hemisphere | Test memory period | Activity | Function | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fear conditioning | Healthy subjects | Basolateral amygdala | Bilateral | 1 d post 10 min post-Rec. +Ext. | > | Predict the return of fear | [39] |

| 1 d post 6 h post-Rec. +Ext. | < | ||||||

| dACC | Bilateral | During react. | < | [128] | |||

| vmPFC | < | ||||||

| vmPFC-amygdala | < | Erase fear memory | |||||

| dlPFC | Bilateral | Post-react. | > | Reduce fear | [40] | ||

| Declarative task | Healthy subjects | Hippocampus | Bilateral | Early retrieval post-rec. | < | – | [231] |

| Late retrieval post-rec. | < | ||||||

| Parahippocampus | Early retrieval post-rec. | < | |||||

| Late retrieval post-rec. | < | ||||||

| Prefrontal cortex | Early retrieval post-rec. | < | |||||

| Late retrieval post-rec. | < | ||||||

| Parietal lobe | Early retrieval post-rec. | < | |||||

| Late retrieval post-rec. | < | ||||||

| Temporal lobe | Early retrieval post-rec. | < | |||||

| Late retrieval post-rec. | < | ||||||

| Posterior cingulate cortex | Early retrieval post-rec. | > | |||||

| Late retrieval post-rec. | < | ||||||

| Anterior cingulate cortex | Early retrieval post-rec. | > | |||||

| Late retrieval post-rec. | < | ||||||

| Hippocampus | Left | During React. | < | Detect incongruence and update memory | [98] | ||

| Over faces task | PTSD patients | Thalamus | Right | Propranolol-induced reconsolidation impairment | > | – | [99] |

| ACC | Right | < | Decrease PTSD symptom | ||||

| Mid-frontal gyri | Bilateral | < | |||||

| Mid-cingulate | Bilateral | < | |||||

| Face-location association learning paradigm | Healthy subjects | Hippocampus | Left | After new learning-induced during Rec. | < | Process declarative memories | [232] |

| Amygdala | Right | < | |||||

| Two-day exposure protocol | Arachnophobia subjects | Amygdala | Bilateral | 10 min exposure prior to reactions. | > | Predict fear | [167] |

| Three-day retrieval extinction protocol | Healthy subjects | IT | Bilateral | Post-retrieval extinction | > | Prediction error | [137] |

| dlPFC | > | ||||||

| dlPFC-ACC | > | ||||||

| Autobiographical memory procedure | Healthy subjects | Hippocampus | Bilateral | During react. | < | Positive information update | [233] |

| Ventral striatum | < |

Rec, Reconsolidation; Ext., Extinction; React., Reactivation; <, increased activity; >, decreased activity; ACC, anterior cingulate cortex; dACC, dorsal anterior cingulate; vmPFC, ventromedial prefrontal cortex; dlPFC, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex; IT, inferior temporal cortex

Memory Extinction: Origins, Mechanisms, and fMRI Insights

The study of extinction tracks back to Pavlov’s classic experiment where he recorded the gradual disappearance of a dog’s salivary response to food cues when those cues were presented without food [41, 100]. This process, known as “extinction”, refers to the gradual weakening of a CR [101]. Unlike forgetting, extinction involves the formation of a new memory that associates a CS with the absence of a US, requiring new protein synthesis for memory maintenance [102, 103]. Experimental approaches to extinction involve repeated exposure to a CS alone or prolonged exposure in a conditioning context to reduce CRs. The prediction error (PE) between expected and actual outcomes destabilizes the original memory, facilitating the formation of a new CS-no US memory that competes with the original CS-US memory. Extinction encompasses acquisition, retrieval, and retention periods, but over time, vulnerabilities like spontaneous recovery can lead to the return of the original fear memory [104]. Context renewal occurs when a CR reappears outside the extinction context, and reinstatement refers to the return of fear responses if the US unexpectedly reappears, reinstating the CS-US association [105].

The cortex, amygdala, and hippocampus collaborate in fear extinction memory, reflecting an emerging interest in their role in whole-brain networks [28]. Since the neuronal circuits of extinction memory have been well documented [106], in this review we outline neuronal circuits involving diverse subpopulations, summarizing various manipulation techniques such as pharmacological interventions, optogenetics, Tetanus toxin light chain, and optogenetically-induced long-term potentiation across extinction stages (Fig. 3B and Table 3).

Table 3.

Summary of neuronal circuits of extinction memory in fear conditioning

| Paradigm | Extinction period | Neuronal circuits | Neuronal type | Manipulation | Effect on memory | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pavlovian FC | Fear conditioning | OFC-IC-NAc | – | Optogenetic activation | ↑ ext. retrieval | [69] |

| Fear conditioning+ Ext. acquisition | IC-NAc | – | TetTox inactivation | ↓ ext. retrieval | ||

| Pre-ext. acquisition | VTA-AcbSh | Dopamine | Pharmacological activation | ↑ext. acquisition | [234] | |

| mPFC-RE | – | Pharmacological inhibition | ↓ext. | [158] | ||

| BLA-mPFC | CaMKII | Optogenetically induced-LTD | ↑ext. | [114] | ||

| Ext. acquisition | PL-IL | Pyramidal | Optogenetic activation | ↑ext. acquisition | [111] | |

| IL-BLA | CaMKII | Optogenetic activation | ↑ext. | [110] | ||

| VTA-NAc mShell | Dopamine | Optogenetic inhibition | ↓ext. consolidation | [235] | ||

| VTA-vmPFC | Dopamine | ↓ext. acquisition | ||||

| DR-BA | 5-HT | Optogenetic activation/inhibition | ↓/↑ ext. | [236] | ||

| FN-vlPAG | Glu→Glu+GABA | Optogenetic activation | ↑ext. | [237] | ||

| SC-MD | GABA→CaMKII | Optogenetic inhibition | ↑ext. | [238] | ||

| MD-BLA | CaMKII-pyramidal | Optogenetic activation | ↓ext. | |||

| dMTm-CeA | CaMKII | Optogenetic inhibition | ↑ext. | [239] | ||

| BLA-vCA1 | Glutamatergic | Optogenetic inhibition | ↓ext. | [119] | ||

| Pre-test | BLA-CeL | Glutamatergic | Pharmacological inhibition | ↓ext. | [68] | |

| Pre-ext. retrieval | IL-PVT | Glutamatergic | Pharmacological inhibition | ↓ext. retrieval | [240] | |

| PVT-CeL | ||||||

| Ext. retrieval | dHPC-IL | CaMKII | Optogenetic activation/inhibition | ↑/↓ext. retrieval | [118] | |

| BLA-mPFC | – | Optogenetic modulation | ↑ext. retrieval | [115] | ||

| vHPC-mPFC | ||||||

| Ext. renewal | vHPC-PL | Glu→GABA | Pharmacological inhibition | ↑ext. | [117] | |

| CFC | Ext. acquisition | PL-amygdala | Pyramidal | Optogenetic activation | ↓ext. | [109] |

| Ext. retrieval | NRe-BLA | – | Optogenetic activation/inhibition | ↑/↓remote ext. | [112] |

Ext., extinction; AcbSh, nucleus accumbens shell; BA, basal amygdala; CeL, central amygdala; dMTm, dorsal midline thalamus; DR, dorsal raphe nucleus; FN, fastigial nucleus; MD, mediodorsal thalamus; NAc mShell, medial shell of nucleus accumbens; NRe, thalamic nucleus reuniens; RE, thalamic nucleus reuniens; OFC, orbitofrontal cortex; PVT, paraventricular nucleus of the thalamus; SC, superior colliculus; vlPAG, ventrolateral periaqueductal gray; vmPFC, ventromedial prefrontal cortex; VTA, ventral tegmental area; GABA, gamma-aminobutyric acid; Glu, glutamate

The PFC plays a key role in the formation and retrieval of extinction memory [107, 108]. Pyramidal projections from the prelimbic cortex (PL) to the amygdala regulate fear expression [109], while infralimbic cortex (IL)-BLA connections facilitate extinction acquisition [110]. The PL also sends excitatory afferents to the IL, which promotes extinction learning, particularly during early acquisition [111]. However, these conclusions lack verification of the tripartite neural circuit projections (PL-IL-BLA) regulating extinction learning. Pharmacological inhibition of the excitatory afferents from the PL to the paraventricular thalamus (PVT) or the PVT to the central lateral amygdala (CeL) before retrieval impairs extinction memory. Monosynaptic retrolabeling can be used to establish the role of the PL-PVT-CeL circuit in fear extinction. Interestingly, the thalamic nucleus reuniens (NRe) works as a hub for IL-BLA projections during remote extinction memory, as indicated by significant c-Fos+ activated cells in the IL-NRe and NRe-BLA projections. The anatomical circuit, verified by the retrograde virus method, suggests that a cortical-thalamic-amygdalar circuit plays a pivotal role in remote memory extinction [112]. Another brain structure that deserves further attention is the IC, a gateway to fear or extinction memory through projections to the CeA or NAc, respectively. The orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) exerts top-down control over this circuit; the OFC-IC-NAc pathway promotes extinction learning and expression [69].

The amygdala plays an essential role in memory extinction. Optogenetic activation of the Thy1-expressing subpopulation of glutamatergic BLA neurons during the extinction acquisition period promotes new learning and consolidation of extinction memory [113]. Similarly, optogenetic modulation of BLA-mPFC afferents improves extinction learning and retrieval both in the Pavlovian and contextual FC paradigms [114, 115]. This effect may be due to optogenetically-induced long-term depression, which reduces presynaptic excitability and fear responses during the extinction retention period. Fear conditioning alters corticotropin-releasing factor-expressing (CRF+) neurons in the CeA to non-CRF+ and somatostatin-expressing neurons in the BLA, while extinction learning reverses this transformation [68]. This dynamic remodeling highlights the inevitable role of excitatory CRF+ neurons in fear activity, as their excitation facilitates extinction learning and their inhibition reinforces fear memory. Intriguingly, inhibitory clusters of intercalated (ITC) neurons located between the basolateral and central region of the amygdala also influence the fear state [64]. The dorsal (ITCdm) and ventral (ITCvm) clusters respond to fear- and extinction-state, respectively. Further, stimulation of ITCvm neurons evokes postsynaptic responses in the medial CeA (CeM), which projects densely to the ventrolateral periaqueductal grey (vlPAG), suggesting that ITCvm neurons reduce the fear response by inhibiting the CeM-vlPAG pathway. Conversely, the ITCdm-BLA-mPFC pathway inhibits extinction learning by suppressing ITCvm neurons. These conclusions require further validation in experimental rodents.

Extinction memory is context-dependent, regulated by hippocampal activity, which is indispensable to spatial representation and fear memory, including extinction learning and fear relapse [116]. Pharmacological inactivation of the ventral hippocampus (vHPC) to the IL pathway facilitates fear extinction [117]. Ex vivo whole-cell recordings have revealed that local parvalbumin-expressing interneurons from the BLA mediate fear renewal by feed-forward inhibition. Likewise, optogenetic activation of the pathway from the dorsal hippocampus (dHPC) to the IL enhances fear extinction memory, but this effect is abolished by conditional deletion of extracellular signal-regulated kinase 2 in the IL [118]. The neighboring hippocampal subregions, dHPC and vHPC, contribute differently to fear extinction memory. Yet, there is a controversy over the role of the BLA in vHPC projections in CS-evoked activity during extinction memory [119]. Optogenetic silencing of this circuit during extinction learning significantly impairs extinction memory by degrading local theta-oscillations and weakening the spatial encoding capacity of the vHPC in a glutamatergic transmission-dependent manner.

Various neurotransmitters are important in fear extinction memory [120, 121]. Classical neurotransmitters (for example, γ-aminobutyric acid, glutamate, dopamine, cannabinoids, glucocorticoids, and norepinephrine) play critical roles in fear extinction memory encoding, recall, and retention. Moreover, intracellular signaling pathways such as L-type voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (LVGCCs) and second messengers are essential for extinction memory storage. These mechanisms are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Molecular mechanisms of extinction memory

| Paradigm | Species | Brain areas | Drug administration | Effect | References | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Target | Classification | Drug | Time | Within-session ext. | Ext. retention | ||||

| Pavlovian FC | Lister rat | Systemic | NMDA-R | Partial agonist | DCS | Pre-Ext. acquisition | – | – | [198] |

| BLA | – | ↑ | |||||||

| Systemic | NMDA-R | Noncompetitive NMDA-R antagonist | MK-801 | – | ↓ | ||||

| Sprague-Dawley rat | Systemic | Noradrenergic β-receptor | Blocker | Propranolol | Post-conditioning | ↑ | No effect | [241] | |

| C57BL/6 mouse | Systemic | HDAC | Inhibitor | VPA | Pre-Ext. acquisition | ↑ | ↑ | [76] | |

| KCTD8/12 KO mice | Systemic | GABAB | Agonist | Baclofen | Pre-Ext. acquisition | No effect | No effect | [242] | |

| CFC | Lister rat | Systemic | LVGCCs | Blocker | Nimodipine | Pre-Ext. acquisition | ↑ | – | [243] |

| Wistar rat | CA1 | CB1-R | Antagonist | AM251 | Post-Ext. acquisition | No effect | ↓ | [217] | |

| NBM | Sodium channel | Blocker | TTX | 96 h post-conditioning | No effect | – | [244] | ||

| SN | No effect | – | |||||||

| BLA | No effect | – | |||||||

| NBM | 2 h post-Ext. acquisition | – | No effect | ||||||

| SN | – | No effect | |||||||

| BLA | – | ↓ | |||||||

| ENT | Post-Ext. acquisition | ↑ | ↑ | [227] | |||||

| C57BL/6 mouse | Systemic | NMDA-R | Partial agonist | DCS | Pre-Ext. acquisition | ↑ | ↑ | [214] | |

| AMPA-R | Potentiator | PEPA | Pre-ext. acquisition | ||||||

| mTOR | Inhibitor | Rapamycin | Post-Ext. acquisition | ↑ | ↑ | [225] | |||

| dHPC | Ca2+ signaling pathway | Inhibitor | ALLN | Post-Ext. acquisition | – | ↓ | [229] | ||

| IA | Sprague-Dawley rat | Systemic | mTOR | Inhibitor | Rapamycin | Post-Ext. acquisition | ↑ | ↑ | [230] |

| PL | No effect | – | |||||||

| IL | No effect | – | |||||||

| Wistar rat | Systemic | GABA | Topiramate | Ext. acquisition | ↑ | – | [245] | ||

Ext., extinction; IA, inhibitory avoidance; KCTD,K+ channel tetramerization domain; BLA, basolateral nucleus of amygdala; CA1,, a subregion of hippocampus; NBM, nucleus basalis magnocellularis; SN, substantia nigra; ENT, entorhinal cortex; dHPC, dorsal hippocampus; PL, prelimbic region of medial prefrontal cortex; IL, infralimbic region of medial prefrontal cortex; NMDA-R, N-methyl-D-aspartic acid receptor; DCS, D-Cycloserine; MK-801, dizocilpine; myr-AIP, myristoylated autocamtide-2 related inhibitory peptide; HDAC, histone deacetylase; GABAB, gamma-aminobutyric acid type B receptor; LVGCCs, L-type voltage-gated Ca2+ channels; VPA, valproic acid; CB1-R, cannabinoid type-1receptor; AM251, N-(piperidin-1-yl)-5-(4-iodophenyl)-1-(2, 4-dichlorophenyl)-4-methyl-1H-pyrazole-3-carboxamide; TTX, tetrodotoxin; PEPA, 4-[2-(phenylsulfonylamino)ethylthio]-2,6-difluorophenoxyacetamide; mTOR, mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling pathway; ALLN, N-Acetyl-Leu-Leu-norleucinal; GABA, gamma-aminobutyric acid

The temporal dynamics of extinction memory in the human brain are characterized by connectivity between key structures, including the amygdala, hippocampus, and cortex [122–125]. Researchers have focused on hyperactivated or hypoactivated areas during fear acquisition, extinction training, and extinction recall (Table 5). Healthy volunteers exposed to the Pavlovian FC paradigm show strong activation of the amygdala and its connectivity with cortical areas or the anterior hippocampus [126–129]. Even in focal and bilateral vmPFC-lesioned patients, amygdala connectivity remains elevated with aversive stimuli [130], highlighting the vmPFC-amygdala circuit’s role in predicting fear, supported by the finding that proximal threats by visual reality facilitate learned fear memory via suppressing the amygdala-cortical circuit during fear acquisition and extinction [131, 132]. During extinction training, hippocampus-amygdala connectivity increases [129], as the hippocampus distinguishes in the absence of stimuli [133], and the amygdala facilitates novel associations when information changes [126]. The IC and dACC are also active during extinction memory [134, 135], with hyperactivity reported in PTSD patients and healthy participants during extinction conditioning, acquisition, or recall [136]. The dACC activity is governed by the dorsolateral PFC (dlPFC) as seen in studies where healthy volunteers undergoing Pavlovian FC show inactive states in the inferior temporal cortex (IT) and dlPFC, along with suppressed IT-dlPFC and dlPFC-ACC connections during extinction retrieval [137]. As extinction progresses, the auditory association cortex remains active, even when the activity of the vmPFC and amygdala decreases [138]. Unpredicted outcomes in changing contexts activate the posterolateral cerebellum and frontopolar OFC [125, 139]. Fear acquisition inactivates the cerebellum, which shows reduced activity during extinction retrieval [125, 132].

Table 5.

Human fMRI evidence of memory extinction

| Paradigm | Subjects | Anatomical structure | Hemisphere | Test memory period | Activity | Function | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fear conditioning and extinction paradigm | Healthy subjects | Amygdala | Bilateral | Fear acquisition | < | Fear acquisition and extinction. | [123] |

| Ext. acquisition | < | ||||||

| Healthy right-handed subjects | Amygdala | Right | Ext. acquisition | < | Establish new associations | [126] | |

| Left | > | Encode fear memories | |||||

| Hippocampus | Left | Ext. acquisition | > | ||||

| Fear acquisition | < | – | |||||

| Healthy subjects | vmPFC | Bilateral | Fear acquisition | > | – | [133] | |

| Late ext. | < | Mediate extinction recall | |||||

| Ext. recall | < | ||||||

| Hippocampus | Ext. recall | < | |||||

| Amygdala | Fear acquisition | < | – | ||||

| Late ext. | < | – | |||||

| Healthy subjects | Amygdala | Left | Fear acquisition | < | Involved in the function of the auditory cortex | [138] | |

| Early ext. | < | ||||||

| Late ext. | < | ||||||

| vmPFC | Bilateral | Fear acquisition | > | Recall auditory fear information | |||

| Ext. acquisition | < | ||||||

| dACC | Fear acquisition | < | Maintain fear expression | ||||

| Ext. acquisition | < | – | |||||

| Auditory thalamus | Fear acquisition | < | Maintain durable associations | ||||

| Ext. acquisition | > | ||||||

| Primary auditory cortex | Fear acquisition | < | – | ||||

| Ext. acquisition | < | – | |||||

| Healthy female subjects | Anterior insular | Bilateral | Fear acquisition | < | Predict intrusive memories | [135] | |

| Ext. acquisition | < | ||||||

| dACC | Fear acquisition | < | |||||

| Ext. acquisition | < | ||||||

| Ext. recall | > | ||||||

| PTSD patients | Anterior hippocampus-amygdala regions | Bilateral | Fear acquisition | < | – | [129] | |

| mPFC | – | ||||||

| Anterior hippocampus-amygdala regions | Ext. acquisition | < | Exaggerate threat response | ||||

| Ext. recall | < | ||||||

| Medial prefrontal areas | Ext. recall | < | Regulation deficiency | ||||

| Thalamus | Fear acquisition | > | Regulate arousal and awareness. | ||||

| Ext. acquisition | |||||||

| Ext. recall | |||||||

| PTSD patients | dACC | Bilateral | Fear acquisition | < | Response to cue-elicited fear | [136] | |

| Early ext. acquisition | < | ||||||

| Early ext. recall | < | ||||||

| vmPFC | Late ext. acquisition | < | |||||

| Early ext. recall | < | ||||||

| Two-day Virtual Reality Fear Extinction Experiment | Trauma-exposed children | dACC | Bilateral | Ext. recall | < | Developmental disabilities in extinction neural circuity | [246] |

| Anterior insula | Left | < | |||||

| Fear conditioning-extinction with 3D virtual reality stimuli | Healthy right-handed subjects | Cerebellum lobule VI | Right | Fear acquisition | < | Proximal threats extinction and predict fear reinstatement | [132] |

| Ext. acquisition | |||||||

| Fear reinstatement | |||||||

| Amygdala-mPFC | Late ext. | < | – | ||||

| Fear conditioning-reconsolidation- extinction paradigm | Healthy right-handed subjects | Amygdala | Bilateral | Late ext. | << | Extinction learning | [131] |

| vmPFC-amygdala | Early ext. | > | – | ||||

| Late ext. | < | – | |||||

| Three-day retrieval-extinction protocol | Healthy subjects | IT | Right | Ext. recall | > | – | [137] |

| dlPFC | Right | – | |||||

| dlPFC-ACC | Bilateral | – | |||||

| IT-dlPFC | – | ||||||

| vmPFC | Early ext. | > | – | ||||

| Late ext. | > | – | |||||

| Fear conditioning with cognitive emotion regulation instructions | Healthy right-handed subjects | dlPFC | Left | Ext. acquisition | < | Regulate fear | [127] |

| Middle frontal gyrus | – | ||||||

| vmPFC | – | ||||||

| Posterior insular cortex | > | – | |||||

| Amygdala | – | ||||||

| Cingulate regions | – | ||||||

| dmPFC | – | ||||||

| Cognitive associative learning paradigm | Healthy subjects | Cerebellar cortex lobule VI | Right | Fear acquisition | < | Fear expression | [247] |

| Ext. acquisition | < | ||||||

| Novelty-facilitated extinction paradigm | Healthy subjects | vmPFC | Bilateral | Ext. acquisition | < | Enhance ext. learning | [124] |

| Ext. retention | < | – | |||||

| Thalamus | Ext. acquisition | > | – | ||||

| Ext. retention | – | ||||||

| Insula | Left | Ext. acquisition | > | – | |||

| Ext. retention | – | ||||||

| dACC | Bilateral | Ext. acquisition | < | – | |||

| Superior frontal gyrus | Left | Ext. acquisition | < | – |

<, increased activity; >, decreased activity; Ext, Extinction; vmPFC, ventromedial prefrontal cortex; dmPFC, dorsomedial prefrontal cortex; dlPFC, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex; dACC, dorsal anterior cingulate; IT, inferior temporal cortex

Understanding Their Relationship and Mechanisms

Historical Opinions on Their Relationship

Based on the above evidence, there appear to be competing mechanisms between reconsolidation and extinction [140]. These discrepancies suggest that methodological variables influence fear memory retrieval outcomes. Earlier, Nader et al. found that intra-amygdala infusion of anisomycin (ANI) has an amnesic effect on consolidated memory during the reactivation period in the fear conditioning paradigm [18]. Nevertheless, some findings generated contrasting opinions regarding the effect of ANI on memory retrieval. One group used a one-trial IA task to examine the role of protein synthesis in the hippocampus during extinction memory. As extinction training progresses, the CR of rats gradually diminishes, while a bilateral infusion of ANI into the CA1 region before the extinction retention test completely blocks extinction memory [141]. Furthermore, though infusing ANI into the hippocampus before the first memory retention test impairs memory retrieval at 24 h, it is resistant in the following test sessions, suggesting that the protein inhibitor impairs extinction without affecting consolidated fear memory. The literature contains several inconsistencies, which arise from differences in experimental paradigms, targeted brain areas, and investigators. It is arguable that other studies using similar paradigms in either the amygdala or hippocampus reach the same conclusion as the study of Nader et al. [93], while others suggest that amnesic agents only affect extinction [142].

To reconcile the conflicting findings, several studies have established that reconsolidation and extinction are dissociable on the dominant memory trace (Fig. 3C). The Chasmagnathus model of contextual memory has been used to examine CSM with various contextual exposures, ranging from 5 to 120 min [58]. CSM retention tests showed detectable memory for exposure durations < 60 min, regardless of the contextual environment. For exposure durations > 60 min, CSM is significant in the novel context, but not in the training context, suggesting well-established extinction memory. In addition, they used the protein synthesis inhibitor cycloheximide (CHX) and revealed that after exposure, CHX impaired either reconsolidation or extinction in the 5- or 60-min context exposure groups. These results suggest that reminder duration acts as a switch in determining the outcome of memory retrieval and that reconsolidation and extinction are not mutually exclusive but depend on trace dominance.

Later discoveries refined these findings by showing that non-reinforcement and CS offset are necessary for reconsolidation and extinction [103]. One-trial VDS during re-exposure, with CHX given either 2 h later or immediately after re-exposure, failed to affect reconsolidation. However, re-exposure without one-trial VDS did affect reconsolidation, implying that a US before the CS strengthens reconsolidation, preventing amnesic effects even within the effective time window of CHX. Similar experiments on extinction memory confirmed that non-reinforcement significantly impacts memory retrieval outcomes. These findings contribute to an ineluctable interpretation that it is the non-occurrence of the expected reinforcement, terminated by non-reinforcement, that switches reconsolidation to extinction. Pérez-Cuesta et al.’s research modified the CSM retention paradigm by re-exposing rodents in a training context for 15 mins plus an additional 2 h. They tested reconsolidation before the end of the long exposure and assessed extinction memory afterward. Both reconsolidation and extinction were detectable, indicating that CS-offset initiates extinction even when reconsolidation can be tested during long exposures [143].

Nader et al. pointed out that extinction cannot prevent reconsolidation [144], as inhibiting protein synthesis in the BLA of rodents impairs both recently reactivated and extinguished fear memories. Reconsolidation and extinction memory develop in parallel and can overlap, depending on the number of CS presentations [145]. Pérez-Cuesta et al.’s further experiments [143] showed that pre-exposure administration of CHX and varying re-exposure conditions to CS or CS-US confirmed that reconsolidation initiates earlier than extinction memory, with partial overlap (Fig. 3C). This aligns with Nader et al.’s findings [144], emphasizing that reconsolidation cannot be attenuated to facilitate extinction [146]. There are amnesic effects on context-shift procedures if ANI is given after reactivation. However, the results demonstrated no fear of memory renewal in either the same or a different context, indicating that post-reactivation administration of ANI takes effect on the memory storage trace rather than extinction memory, which does not support this hypothesis that reconsolidation can be attenuated to facilitate extinction.

From a molecular perspective, evidence is mixed regarding the distinctiveness of reconsolidation and extinction pathways. Some studies suggest that these processes have separable biochemical signaling pathways. For instance, pharmacologically inhibiting CB1-R and LVGCCs affects extinction but not reconsolidation in CFC. Conversely, factors such as protein synthesis and N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors (NMDARs), which impact reconsolidation, also impair extinction [147]. Supporting this, the expression of the immediate-early genes Zif268 and Arc is dependent on reconsolidation. Conditional knockdown of these genes combined with protein inhibition results in a blockade of reconsolidation while altering their expression prevents extinction. The above evidence demonstrates that reconsolidation and extinction have distinct molecular signatures.

Some reports have demonstrated that reconsolidation and extinction share predominantly identical molecular characteristics (Fig. 3C). For instance, disruption of CREB-mediated transcription blocks both reconsolidation and extinction in CFC [93]. Immunohistochemical analysis of the transcription factor CREB and the expression of Arc have revealed significant Arc expression in the amygdala and hippocampus during reconsolidation, and in the amygdala and PFC during extinction. Therefore, both processes engage new gene expression in various brain regions, indicating potential interaction between reconsolidation and extinction under certain conditions. Another biomarker in the BLA is calcineurin, which increases during extinction [148]. Its expression pattern remains unchanged even with an NMDA-type glutamate receptor agonist or antagonist, suggesting an insensitive state, termed the “limbo state” where neither process is engaged.

To clarify the concept of the “limbo state” between reconsolidation and extinction, researchers investigated the ERK1/2 signaling pathway in the CFC paradigm. Memory retrieval sessions were divided into four groups based on the number of non-reinforcement sessions (1, 4, 7, and 10) [149]. Minimal CS stimuli (1) represented reconsolidation, and maximal stimuli (10) represented extinction, with intermediate states at 4 and 7 CS stimuli. Intra-BLA administration of the ERK1/2 pathway inhibitor U0126 did not affect memory retrieval during 4/7 CS stimuli, but it did during 1/10 CS stimuli. In addition, manipulating the ERK1/2 pathways with the NMDAR partial agonist D-cycloserine supports the existence of a “limbo state” [62]. This state is a linear progression between reconsolidation and extinction, differing from Pérez-Cuesta et al.’s idea of overlapping reconsolidation and extinction (Fig. 3C). Similar results were found in the IA paradigm, where the ERK signaling pathway was specifically activated during extinction, and CREB expression was anticipated in both reconsolidation and extinction [71]. Since the ERK pathway is upstream of CREB, its activation facilitates extinction while preventing reconsolidated memory, further establishing the “limbo state”. Moreover, a previous study identified “fear neurons” during non-reinforcement reactivation and “extinction neurons” during extinguished memory in the amygdala [150], raising a question about the diversity of neuronal populations involved in fear memory retrieval. Further identification of different neural types responsible for distinct memory stages is necessary.

In summary, reconsolidation and extinction share similar biochemical signatures, but the exact mechanism of how reconsolidation turns into extinction remains largely unknown.

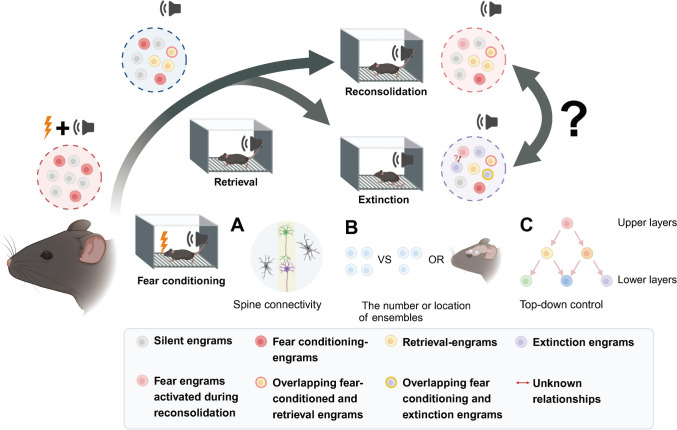

Engram Cells in Memory Reconsolidation and Extinction

Reconsolidation and extinction are both memory-updated processes triggered by the presence of the CS [146], involving new protein synthesis. In addition, these two mnemonic processes share partially-overlapping molecular and neuronal profiles. Questions arise: What proteins are synthesized? Where is the updated memory stored? Are there two phenotypically distinct populations that regulate reconsolidation and extinction separately? Richard Semon’s Engram Theory may help explain these discrepancies. Proposed over a century ago [151], it was not until the turn of the millennium that the “engram cells” theory gained significant attention in the study of memory owing to the technical restrictions of that era [152]. The term “engram” refers to an organic substance that stores memories with three features: (1) activation by a learning experience; (2) modification by an artificial learning experience; and (3) reactivation by subsequent retrieval, often involving non-engram, silent, and active engram cells [151, 153].

The relationship between memory consolidation and engrams remained unexplored until researchers found that protein synthesis inhibitors can induce amnesia, which can be reversed by artificially activating the engram cells labelled during fear training. This phenomenon can also occur when amnesic treatments are administered during the reconsolidation period [154]. During CS retrieval, hippocampal engram cells activated by backward conditioning (US-CS) are labeled, showing that CS retrieval can significantly increase the overlapping proportion of the fear conditioning engram and retrieval-induced engram cells, indicating a reactivation of the fear conditioning engram. This indirect retrieval procedure also underlies the reconsolidation phase, since amnesic treatment into the hippocampus during a post-reactivation period can interfere with the original fear memory [155]. Further, optogenetic activation of c-Fos-tagged dDG ensembles impairs conditioned fear responses during post-reactivation [66], regardless of the valence of the engram. Nevertheless, this freezing decline phenomenon can be replicated if a sufficient proportion of dDG neurons are activated, indicating that the reconsolidation process is not linked to engrams of a specific valence. Furthermore, the reconsolidation process involves different engram cells for fear conditioning and reinstatement, with minimal overlap, implying that reconsolidation re-engagement of fear conditioning engram ensembles may generate new engrams. The verification can be expanded in the amygdala where c-Fos-LacZ transgenic rats in the auditory FC paradigm [156] showed that high neuronal activation leads to the expression of c-Fos and LacZ mRNA, followed by β-galactosidase (β-gal) protein expression. Infusion of Daun02, which disrupts neuronal function when converted to Daunorubicin by β-gal, significantly decreased freezing levels after reactivation, demonstrating that reconsolidation reactivates original fear conditioning engrams rather than creating new engram ensembles. Thus, manipulating reconsolidation engram cells may be less effective, as reconsolidation primarily reactivates existing fear conditioning engrams.

Extensive evidence has shown the widespread existence of extinction engram cells throughout the brain [115, 119, 157–161]. Fear extinction engrams, identified by engram cell labelling technology in transgenic rodents, facilitate the labelling and manipulation of activated neurons across different mnemonic periods. Extinction activates engram ensembles in the dDG, which can be artificially disrupted during extinction retrieval [159]. Moreover, the genetical signature of the amygdaloid extinction engram ensembles has been identified in Ppp1r1b+ BLA neurons [160]. Building upon the “prediction error” theory, it is tempting to speculate that exposing engram cells to a gradually decreasing frequency of non-reinforced stimuli could encode diverse information. Attempts to reverse memory valence can be made by reactivating original engrams while applying conditioning of opposite valence [162], potentially converting related information from negative to positive. Interestingly, in both contextual fear and reward conditioning, engram cells in the dDG encode bidirectional valence with a switch in functional connectivity due to progressively growing synaptic strength [154]. Also, the reward-responsive neurons exhibit functional equivalence with the extinction engrams. This implies that extinction learning represents a positive rewarding experience for fear-conditioned subjects [66]. The engram cell theory provides a cornerstone for explaining memory malleability.

Several studies have revealed that fear acquisition engrams can be suppressed by extinction engram cells, highlighting distinct neuronal ensembles governing fear memory [115, 158, 159]. During the memory updating process initiated by non-reinforced stimulus-initiated fear engrams increasingly overlap with extinction engram cells in the PL [161]. These findings suggest that as extinction learning progresses, some fear engrams may switch into extinction ensembles (Fig. 4). Despite evidence that activated engram cells often inhibit the recruitment of non-activated ones [163, 164], whether a competitive mechanism among engram cells is triggered by the PE remains elusive. Following this question, scientists have demonstrated that it is the “collocation window” between events that establishes competition among engram cells in the lateral amygdala, regulated by parvalbumin interneurons that release GABA [165]. When rodents receive two distinct fear conditioning events within 6 h, engram cells integrate collaborative memories. However, for events >1 day apart, engram cells represent them as independent events. This discovery is consistent with the concept of the “reconsolidation window” [33], which delineates the effective timeframe for rewriting memory. In this context, if the non-reinforcing stimulus is presented during the reactivation period, the already-formed associations in the fear engram cells are overwritten in the absence of the US. If non-reinforcing stimuli are presented during reactivation, the existing associations in fear engram cells may be overwritten in the absence of the US [161]. Fear-related learning mechanisms form strong connections among fear engrams, but concerted efforts are required to degrade these neural associations. Engrams encoding different memories can be reflected in their morphological changes through spine connectivity or vector distance within the population [154, 161]. Caution is warranted regarding the potential of silent engram cells. Emerging evidence supports the hypothesis that it is the silent-state, rather than the latent state, of engram cells in a silent-state, not a latent-state, that makes them inaccessible under natural conditions. However, artificial regulation may facilitate access to these cells, thereby reducing the likelihood of repeated CS exposures activating the dormant engrams [157, 159, 166].

Fig. 4.

A possible role for engram cells pertaining to memory reconsolidation and extinction. This review proposes the existence of distinct engram ensembles during mnemonic stages, such as reconsolidation and extinction. During fear conditioning, a cohort of silent engram cells (grey, silent engrams) encode new information and become conditioning-activated engram cells (scarlet, fear conditioning engrams). Upon memory retrieval, other engram ensembles are activated by the CS (yellow, retrieval engrams). Some conditioned- and retrieval-engrams may overlap (yellow with red border, overlapping fear-conditioned and retrieval engrams). Memory retrieval triggers two opposing stages, namely reconsolidation and extinction. The former process reactivates original fear conditioning engrams (red, fear engrams activated during reconsolidation), and the latter process generates new engram ensembles (violet, extinction engrams). As extinction learning progresses, some fear engrams may switch into extinction ensembles (violet with yellow border, overlapping fear conditioning, and extinction engrams). However, the intrinsic switch mechanism between reconsolidation- and extinction-engrams is not well understood (black question mark). Potential factors govern the competition between reconsolidation and extinction engram cells including spine connectivity (A), the number or location of engram ensembles (B), or projections from upper brain structures (C). The hypothetical mutual interaction between reconsolidation- and extinction-engram cells requires further exploration (tiny red question mark, unknown relationships)

Behavioral Therapy Based on Reconsolidation

Currently, ET aims at weakening traumatic memory associations by inducing reconsolidation and has emerged as a promising alternative to the standard ET strategy. This approach updates memory by decreasing amygdaloid activity [167, 168], thereby reducing the emotional impact of traumatic memories. By presenting unreinforced CSs within this labile, retrieval-induced period, memory is updated so that the CS, once predictive of danger, is now associated with the absence of the US. This shift can potentially lead to the permanent erasure of fear memories without the use of medications [32]. Known as the “retrieval-extinction” the “post-retrieval extinction” (PRE) protocol, or the “reconsolidation of traumatic memories” (RTM) protocol [169–171], this method has advantages over traditional extinction therapy, such as cost-effectiveness and high adherence rates; it is gaining popularity among ET alternative [172, 173]. For limitations of ET, refer to Table 6.

Table 6.

Limitations of exposure therapy among PTSD patients

| Type of exposure therapy | Subjects | Evaluation standard | Course of treatment (weeks/m) | Follow-up sessions | Treatment dropout (%) | Therapeutic outcomes | Limitations | Possible reasons | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CPT | 94 active service duty members with a diagnosis of PTSD and MDD |

a. MADRS b. CAPS-5 c. PHQ-9 d. PCL-5 |

20 | 3 weeks | 15 | No comparable significant difference. | The use of BA may not be necessary over CPT alone. | Treatment options may be decided by patient preference and shared decision-making | [248] |

| CPT+BA | 21 | ||||||||

| D-CPT | Adolescent PTSD patients (aged 14-21 years, n=38) |

a. Self-developed TAS b. Self-developed TCS c. HAQ d. CAPS-CA |

16-20 | 3 weeks | 13.63 | Therapeutic alliance is positively correlated with reduced PTSD symptom | Therapeutic adherence and competence are negatively correlated to the treatment outcome | Lack of therapist adherence and competence | [249] |

| GBCT |

PTSD veterans (n=98) |

a. CAPS-5 b. BDI-II and BAI c. SCID-IV-TR d. TLEQ e. SF-36 f. CERQ-Short |

16 | – | 38.4 | – | Treatment noncompletion | Reported lifetime trauma exposure, higher depression symptoms. | [250] |

| GPCT |

PTSD veterans (n=100) |

20.2 | 2.389 times more likely to compete for treatment than GBCT groups | – | A group therapy strategy is preferred | ||||

| PE delivered via video teleconferencing | Rural veterans (n=27) |

a. PDS b. BDI c. BAI d. CAPS |

12 | 1 month | 70 in the iPhone group | Decrease PTSD symptom | Significant high attrition | Poor technical support | [251] |

| PE | PTSD male combat veterans (age=65 years, n=87) |

a. CAPS b. SCID-IV-TR c. PCL-S d. PHQ-9 |

12 | 6 weeks | 27 | PTSD symptomology has improved | Hard to maintain therapeutic outcomes | Remote traumatic memories are resistant to interference | [252] |

| RT | |||||||||

| MT |

PTSD veterans (n=370) |

a. PSS-I b. PCL-S |

2 | 6 weeks | 13.6 | No extinguished treatment found | Trauma-focused treatment may not be suggested for improving PTSD symptoms in active-duty military personnel. | Alternative treatments may be needed to investigate better clinical outcomes. | [253] |

| ST | 8 | 24.8 | |||||||

| PCT | 8 | 12.1 | |||||||

| PE with AE (imaginal exposure) | Active duty United States service members (n=125) |

a. PCL-S b. PSS-I c. BDI-II d. BAI e. STAXI-2 f. ADUIT g. SSI |

8–12 | 1 and 6 months | 52.8 | Not as ideal as delivered PET alone | AE intervention fidelity is not systemically assessed post-treatment | Personalized psychotherapy is recommended | [254] |

| 3MDR | Treatment-resistant PTSD veterans (n=43) |

a. CAPS-5 b. PCL-5 c. PABQ |

6 | 12 and 16 weeks | 7 | 45% of patients improved clinically | No statistical variations of PTSD symptom severity between groups | A larger sample size and wider clinical application are needed | [9] |

| VRE | Active duty soldiers with PTSD (n=108) |

a. SUDS b. CAPS |

26 | 3 and 6 months | 44 | A greater decrease in CAPS scores without group difference | Poor emotional engagement | Substantial emotional and stress evaluation should be established | [255] |

| PE | 41 | - | |||||||

| VRET | Active duty soldiers with PTSD (n=153) | a. CAPS | 9 | 3 months | 16.2 | CAPS-score improved 31% | High dropout occurred only in the VRET group | A common phenomenon that is consistent with other reports | [256] |

| CRET | 0 | CAPS-score improved 37% | – | – | |||||

| TMT | Veterans and active duty personnel with PTSD (n=112) |

a. CAPS b. PCL-M c. SCID I and II d. SF-36 e. BRIEF-A f. TRGI g. CGI h. HAMD |

17 | 3 and 6 months | 2 | High-level and satisfactory treatments | Not a randomized controlled trial | Latent variables should be constructed | [257] |

| Web-PE | 40 military personnel with PTSD |

a. CEQ b. CAPS-5 c. PCL-5 d. PHQ-9 e. VR-12 |

8 | 3 and 6 months | 52.6 | Reduced PTSD symptom | High dropout rate | Achieve better therapeutic outcomes in open trial participants. | [258] |

| PCT | 23.8 | No comparable difference, but PCT achieved clinically significant change. | |||||||

| NET | Patients with comorbid BPD and PTSD (n=11) |

a. SCID-I and II b. CTQ |

10 | 12 months | 9.1 | NET is feasible and safe in an inpatient program | Lack of outpatient use | This type of inpatient setting is common in Germany | [259] |

| DET | PTSD patients (n=141) |

a. IDCL b. IES-R c. PDS d. BSI e. PTCI f. IIP-C g. Global Severity Index |

Not mentioned | 6 months | 12.2 | CPT performed significantly better than DET | Unreliable remission rates | Incomplete diagnostic criteria for PTSD symptoms | [260] |

| CPT | 14.9 |

3MDR, virtual reality and motion-assisted exposure therapy; AE, aerobic exercise; AUDIT, Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test; BA, behavioral activation; BAI, Beck Anxiety Inventory total score; BDI-II and BAI, the Beck Depression Inventory-II and Beck Anxiety Inventory; BPD, Borderline Personality Disorder; BRIEF-A, the Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function-Adult Version; BSI, Brief Symptom Inventory; CAPS-5, the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5; CAPS-CA, the German version of the Clinician-administered PTSD Scale for Children and Adolescents; CEQ, Credibility/Expectancy Questionnaire; CERQ-Short, the Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire-Short Form CPT, cognitive processing therapy; CGI, Clinical Global Impressions Scale; CHANGE, a coding system designed to capture processes of therapeutic change, including both facilitators and inhibitors of change; CPT, cognitive processing therapy; CRET, control exposure therapy; CTQ, Childhood Trauma Questionnaire; D-CPT, developmentally adapted cognitive processing therapy; DET, dialogical exposure therapy; GBCT, group cognitive behavioral treatment; GPCT, group present-centered treatment; HAQ, the German version of the Helping Alliance Questionnaire; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; HAMD, Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression; IDCL, the German version of the International Diagnostic Checklist for DSM-IV and ICD; IES-R, Impact of Event Skala-revidierte Version; IIP-C, the Inventory of Interpersonal Problems-Circumplex Version; MADRS, Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale; MDD, major depression disorder; MT, massed therapy includes prolonged exposure therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy involving exposure to trauma memories/ reminders are administered altogether; NET, Narrative exposure therapy; PABQ, Posttraumatic Avoidance Behaviour Questionnaire; PCL-5, PTSD Checklist for DSM-5; PCL-M, PTSD Checklist-Military Version; PCL-S, PTSD Checklist-Stressor-Specific Version; PCT, present-centered therapy; PDS, a self-report instrument which can be used for determining PTSD diagnostic status according to DSM-IV criteria and symptom severity; PE/PET, prolonged exposure therapy; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire-9; PSS-I, PTSD Symptom Scale-Interview; PTCI, Posttraumatic Cognitions Inventory; SCID I and II, the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV to assess other Axis I and II disorders; SCID-IV-TR, the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders-Patient Edition with Psychotic Screen; SF, the Physical Role Functioning subscale of the Medical Outcomes Study Short-Form Health Survey; SF-36, Health-Related Functioning: Medical Outcome Study Short Form-36 Health Survey; SSI, Scale for Suicidal Ideation; ST, spaced prolonged exposure therapy; STAXI-2, State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory; SUDS, subject units of discomfort; TAS, therapeutic adherence scale; TCS: therapeutic competence scale; TRGI, Trauma-Related Guilt Inventory; TLEQ, the Traumatic Life Events Questionnaire; TMT, trauma management therapy; VR-12, the Veterans RAND 12-Item Health Survey; VRE/VRET, visual reality exposure therapy; Web-PE, a web version of Prolonged Exposure Therapy

Several factors contribute to the efficacy of reconsolidation-based protocols. Firstly, it is the timing that matters. The success of this intervention relies heavily on the time window during which memories are temporarily destabilized and susceptible to modification. In humans, reactivating fear memories 10 min, but not 6 h, before extinction produces a durable reduction in fear that can last at least a year [33]. Secondly, a degree of PE is essential for destabilizing memories. Multiple PEs weaken original fear memories more effectively and prevent fear from returning during reinstatement compared to a single-PE strategy [174]. This protocol leverages PE to create a discrepancy between the original learning context and the reactivated context [175]. Moreover, an uncertain number of PEs, rather than a PE alone, may more effectively prevent fear return under a laboratory paradigm [176]. The above evidence suggests that the degree of violation during the memory-updating process facilitates fear attenuation and extinction learning. Thirdly, the unpredictability of interval length is also vital. In a PRE training paradigm, researchers found that distributing random inter-trial intervals (ITIs) during the reactivation, rather than fixed ITIs, leads to a greater erasure of fear memory [177]. Greater variability in ITIs results in a more significant erasure of reconsolidated memory [178]. Finally, PTSD patients harbor persistent fear memories that limit the effectiveness of standard ET. Thus, preventing the recurrence of old fear memories is an important measure of PRE therapy’s robustness. Human studies have shown that PRE can effectively eliminate both recent (1-day-old) and remote (7- and 14-day-old) fear memories [179, 180]. A modified PRE protocol, in which the US is presented before extinction, prevents fear relapse for at least 6 months [179]. Encouragingly, this approach has also shown success in treating naturally-occurring phobias, like arachnophobia [167, 181], and offers promise for those with severe, prolonged trauma exposure [171, 172, 182]. As females are more susceptible than males [183], reconsolidation-based protocols have shown promising results in female patients as well [182]. In sum, these studies provide compelling evidence that reconsolidation-based protocols are not only effective in PTSD, but also offer long-lasting prevention against the return of fear.