Abstract

On 22 March 2023, the Geroscience Translational Research & International Conference on Frailty and Sarcopenia Research (ICFSR) Task Force met in Toulouse, France to discuss avenues to foster the development of intrinsic capacity and frailty clinical trials under a geroscience perspective. A synthesis of these discussions and a set of recommendations are presented in this Meeting Report.

The concepts of intrinsic capacity and frailty are central to understanding human aging. Intrinsic capacity is the ensemble of all physical and mental attributes (for example, locomotion, cognition, psychology, vitality, hearing and vision) that are internal to an individual and are important for optimal function1,2. Frailty is a state of increased vulnerability, loss of resilience and high risk of adverse health events3. Therapeutic interventions to optimize intrinsic capacity and counter frailty have the potential to prevent dependence in activities of daily living (the functional end point to be avoided), promote healthy aging and extend human healthspan. Consistent with the geroscience hypothesis, interventions that target the fundamental biology of aging may both prevent the onset and reduce the severity of multiple chronic conditions and thus contribute to healthy aging. However, although the International Classification of Diseases 11th Revision (ICD-11) code ‘MG2A Ageing associated decline in intrinsic capacity’ has recently been accepted and encompasses both intrinsic capacity and frailty, there are no approved drugs for these indications.

On 22 March 2023, the ICFSR Task Force met to discuss potential bridges of geroscience with intrinsic capacity and frailty research. The main topics discussed during this meeting, and reported here, involve biological aging mechanisms and biomarkers, potential molecules that target frailty, the design of geroscience clinical trials for frailty and intrinsic capacity, and the role of resilience in this context.

Resilience may have a crucial role in linking geroscience to intrinsic capacity and frailty

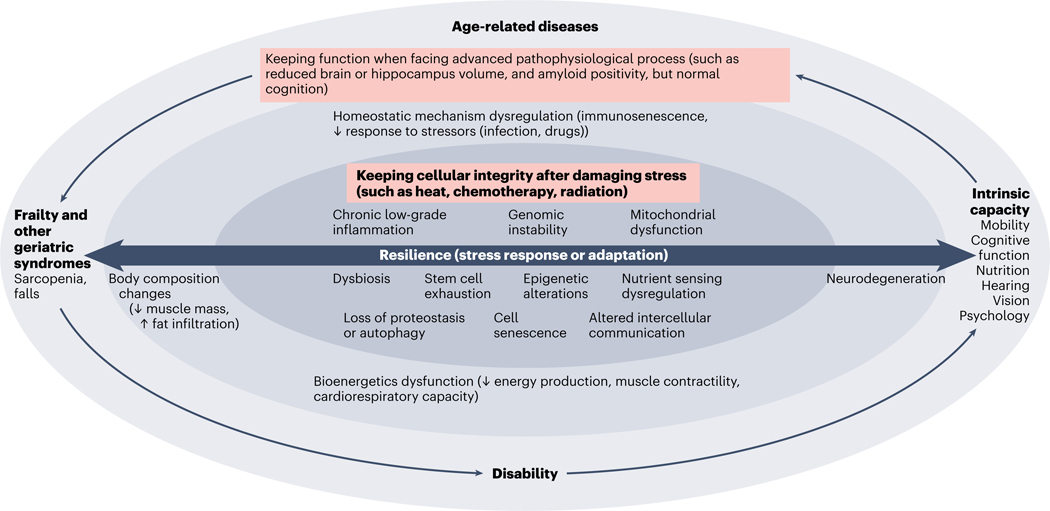

Intrinsic capacity and frailty interact with chronic diseases during aging. The shift from a disease-focused to a function-centered approach echoes a current shift that is happening in clinical practice (for example, the Integrated Care for Older People (ICOPE) program from the World Health Organization (WHO))4. In this context, the concept of resilience (that is, the capacity of the body to respond or adapt to stress) is attracting attention, as resilience can be assessed from cellular and molecular levels to the whole-body level, and from basic and translational science through to clinical research and public health. The loss of resilience (which is the result of impairments in the main biological drivers of aging) leads to declines in intrinsic capacity and to frailty, and also to chronic diseases (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 |. Role of resilience in aging studies, from molecular or cellular mechanisms to overt clinical conditions.

Resilience is of central importance for organism homeostasis during aging. Resilience crosses several layers, from the cellular level to physiology and then to overt clinical phenotypes. At the molecular or cellular level, resilience represents the capacity to maintain the integrity of cellular functions during or after high-level damaging stress (such as heat, radiation or chemotherapy). At the physiological and phenotypic levels, resilience represents the capacity to maintain optimal function even in the presence of advanced pathophysiological processes (such as keeping normal cognition even in the presence of brain atrophy and amyloid positivity). Impairment in the resilience capacity determined by molecular or cellular alterations accelerates biological aging and ultimately leads to the onset and increased severity of interrelated clinical conditions such as diseases, functional decline and geriatric syndromes, and dependency.

Despite its central role in the geroscience hypothesis, measuring resilience and its effect on health remains challenging; this is a major obstacle to progress in this field. Some of the open questions relate to how resilience should be measured at the cellular, molecular and physiological levels; how cellular or molecular resilience determines physiological resilience; and how all of these resilience layers determine health events during aging. Another major challenge is to identify the candidate biomarkers of resilience.

Solving the challenges faced by studies on resilience is crucial both to increase our understanding of the role of resilience in determining the pace of aging and to derive biomarkers for clinical applications. The importance of resilience in aging is currently attracting attention and funding opportunities for researchers.

Targeting frailty pharmacologically

Senotherapeutic agents.

The balance between scientific design and feasibility of trials is a major challenge for the field of geroscience, as is exemplified through trials of senotherapeutic agents. Senotherapeutics are a group of drugs that target a biological driver of aging — cellular senescence — through senolytic (‘cell killing’) or senomorphic (changing cell behavior) mechanisms of action. At least 24 trials of senotherapeutics have been undertaken to date; among these are three active or recently completed trials for frailty using the natural products quercetin and fisetin5. Growing attention on senotherapeutics from the scientific community has only recently attracted the attention of pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies, which may be due to challenges in defining pathways for regulatory approval in the context of geroscience versus individual diseases (for example, end points). Other challenges for translation from bench to bedside include how to identify persons who will most benefit from such interventions, and what biomarkers are accessible and reflect senescent cell burden, target engagement and treatment effect.

Choices must be made regarding the eligibility criteria for participants: selecting only people with elevated levels of cell senescence is likely to reduce heterogeneity, sample size and costs. On the other hand, selecting everybody (as every single person has started the process of cell senescence to some degree) increases sample size and costs, but also increases the generalizability of findings. Stratifying recruitment according to senescent cell levels offers an intermediate compromise. An additional complication is the identification of the best measure of cell senescence to use. In this context, plasma- or serum-based biomarkers (especially markers related to the senescence-associated secretory phenotype) constitute good candidates as they are not very invasive or expensive as compared to other measures of cell senescence (for example, those based on tissue biopsies). In addition to serving as inclusion criteria, cell senescence markers can also be used as surrogate efficacy end points — in particular for pilot clinical trials developed to inform future phase III randomized controlled trials.

Regarding clinical outcomes, one can focus on individuals with a specific age-related disease or target multiple chronic conditions at a time. The first approach has the advantages of being easier to control (a less complex study design), reducing the heterogeneity of the study population and, probably, increasing the chances of a treatment being approved by regulatory drug agencies (as it is based on the traditional model of a given medicine receiving an indication to treat a specific disease). However, targeting multiple conditions at once (not only diseases, but also geriatric syndromes (such as frailty) and declines in body functions (such as intrinsic capacity domains)) — which is the main foundation of the geroscience field — would have a much higher impact at both individual and societal levels if the tested drug proved its efficacy. Although this latter approach is seductive, targeting the acceleration of the aging process requires a new era of collaborative work between scientists (from both the public and private sectors) and regulatory agencies to conduct well-designed and adequately powered clinical trials with the potential to achieve drug approval and release in the market.

Beyond senotherapeutics.

Several other novel approaches have emerged with the potential to optimize intrinsic capacity and target frailty. Apelin, which is an exerkine (exercise-induced myokine) that is associated with muscle cell regeneration and mitochondrial function6, has important implications for the metabolism of glucose, lipids and water. Animal experiments have shown that an apelin agonist improved tissue regeneration in the muscle of old mice. Preliminary data that have been publicly announced by BioAge, from a phase Ib double-blinded, randomized placebo-controlled trial (n = 21 people aged ≥65 years old), suggest that the apelin agonist can benefit muscle mass and quality after 10 days of bed rest, as well as improving protein synthesis rates. Because muscle mass strongly determines mobility performance and disability7, this may suggest that apelin agonists might be good pharmacological candidates to treat acute muscle mass loss and frailty.

Other molecules that may have potential applications for frailty through a geroscience approach involve ketone esters and monoterpene D-limonene. Indeed, ketogenic diets have been shown to extend longevity and healthspan in mice8. Caloric restriction or fasting — an intervention that has proven benefits for lifespan and healthspan — leads to an increase in ketone bodies (small metabolites that work as a source of energy, but that also generate signaling effects as they have protein-binding properties)9. Based on the hypothesis that ketone bodies may improve the immunometabolic profile during aging, an ongoing pilot randomized control trial (n = 30 independently living people aged ≥65 years old, NCT05585762) is being conducted by the Buck Institute to examine the tolerability and safety of 25 g per day of ketone ester supplementation. Regarding monoterpene D-limonene, this small molecule has anti-inflammatory properties that are relevant to cell senescence and dysbiosis (especially owing to the restoration of the gut barrier, which benefits the gut–brain axis) and leads to decreased levels of inflammatory markers10 even in small dosages.

Several other molecules that were not discussed by the task force also have the potential to benefit frailty and intrinsic capacity through a geroscience mechanism of action (acting on one or several cellular or molecular drivers of aging). Table 1 provides a nonexhaustive list of drugs and other interventions (some of them with potential gerotherapeutic properties) investigated in the field of frailty and registered in the database of ClinicalTrials.gov (search performed on 14 June 2023).

Table 1 |.

List of agents investigated in the fields of frailty and registered at ClinicalTrials.gov

| Agent | Registration number | Completion datea | n |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phase I | |||

| Allogeneic MSCs | NCT02065245 | October 2020 | 65 |

| Allogenic MSCs (umbilical cord) | NCT05018767 | November 2025 | 20 |

| Allogenic MSCs (umbilical cord) | NCT04919135 | November 2023 | 44 |

| Cord blood | NCT02418013 | August 2017 | 64 |

| Fecal microbial transplantationb | NCT05598112 | December 2027 | 210 |

| G-CSF-mobilized fresh-frozen plasma | NCT03458429 | February 2023 | 30 |

| Ghrelin | NCT00520884 | December 2008 | 10 |

| Leucine | NCT03831399 | October 2019 | 59 |

| MSCs (umbilical cord) | NCT04314011 | March 2022 | 30 |

| MSCs (UMC119–06-05) | NCT04914403 | July 2025 | 6 |

| Therapeutic plasma exchangeb | NCT05054894 | May 2025 | 100 |

| Phase II | |||

| Allogenic MSCs (umbilical cord) | NCT04919135 | November 2023 | 44 |

| Clazakizumab | NCT05727384 | April 2025 | 60 |

| CoQ10 and nicotinamide riboside | NCT03579693 | April 2021 | 26 |

| Dasatinib and quercetin | NCT02848131 | April 2025 | 30 |

| Dasatinib and quercetin, or fisetin alone | NCT04733534 | July 2024 | 60 |

| Epigallocatechin-3-gallate and vitamin C | NCT04553666 | December 2023 | 40 |

| Fisetin | NCT05595499 | May 2025 | 88 |

| Fisetin | NCT03675724 | June 2024 | 40 |

| Fisetin | NCT03430037 | June 2024 | 40 |

| Ghrelin | NCT01898611 | August 2016 | 16 |

| Ghrelin | NCT01833078 | June 2013 | 5 |

| Ghrelin | NCT01605435 | December 2012 | 5 |

| G-CSF-mobilized fresh-frozen plasma | NCT03458429 | February 2023 | 30 |

| L-Carnitine | NCT03180424 | September 2017 | 60 |

| Losartan | NCT01989793 | October 2016 | 37 |

| Metformin | NCT03451006 | December 2021 | 7 |

| Metformin | NCT02570672 | October 2024 | 125 |

| MSCs | NCT03169231 | September 2021 | 150 |

| MSCs | NCT02065245 | October 2020 | 65 |

| MSCs (umbilical cord) | NCT04314011 | March 2022 | 30 |

| MYMD1 | NCT05283486 | June 2023 | 40 |

| Sodium nitrite | NCT04405180 | December 2024 | 70 |

| Testosterone and recombinant GH | NCT00183040 | February 2007 | 108 |

| Phase III | |||

| Clazakizumab | NCT05727384 | April 2025 | 60 |

| CoQ10 | NCT05422534 | October 2027 | 156 |

| L-Carnitine | NCT03180424 | September 2017 | 60 |

| Metformin | NCT04221750 | September 2026 | 114 |

| Metformin | NCT02325245 | March 2017 | 150 |

| Testosterone | NCT02938923 | August 2023 | 129 |

| Testosterone | NCT02367105 | December 2019 | 83 |

| Testosterone | NCT00345969 | August 2009 | 25 |

| Vitamin D (cholecalciferol) | NCT04847947 | December 2021 | 120 |

| Phase IV | |||

| DHEAS | NCT00664053 | October 2006 | 99 |

| Empagliflozin | NCT03560375 | November 2020 | 120 |

| Omega 3 (DHA and EPA) and calcium | NCT00634686 | June 2009 | 150 |

| Superoxide dismutase enzyme | NCT02753582 | April 2017 | 150 |

| Testosterone | NCT00240981 | December 2009 | 209 |

| Testosterone | NCT00190060 | December 2008 | 262 |

| Testosterone | NCT00182871 | July 2007 | 140 |

| Phase not indicated | |||

| Autologous stem and stromal cells | NCT03514537 | January 2024 | 200 |

| Bifidobacterium longum (probiotics) | NCT04911556 | December 2022 | 120 |

| Curcuma longa, curcuminoids, Zingiber officinale, Ocimum sanctum (=tenuiflorum) and milk (200 ml) | NCT03365310 | July 2018 | 50 |

| Flavonoids | NCT03585868 | December 2017 | 30 |

| Galacto-oligosacchride | NCT03077529 | September 2018 | 44 |

| Hirsutella sinensis | NCT05284149 | February 2024 | 100 |

| Inulin | NCT03995342 | December 2020 | 300 |

| Leucine | NCT01922167 | December 2018 | 19 |

| Nicotinamide riboside | NCT04691986 | June 2025 | 144 |

| Probiotic | NCT04297111 | December 2021 | 12 |

| Vitamin D | NCT05877846 | June 2024 | 25 |

| Vitamin D and calcium | NCT04956705 | April 2022 | 109 |

| β-Hydroxymethyl butyrate | NCT05877846 | June 2024 | 25 |

DHA, docosahexaenoic acid; DHEAS, dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate; EPA, eicosapentaenoic acid; GC-SF, granulocyte-colony stimulating factor; MSCs, mesenchymal stem cells.

Estimated completion dates for studies in ‘Phase not indicated’.

Early phase I.

Designing geroscience clinical trials for frailty and intrinsic-capacity decline

The Task Force members recognize the importance of advancing the field of promoting healthy aging (that is, improving intrinsic capacity and preventing and/or reducing the severity of frailty) by targeting biological aging mechanisms, but also recognize the major challenges that researchers will be facing. Some of the challenges previously mentioned here for senotherapeutics are worth discussing further, including questions as to the optimal indication and efficacy end points for running therapeutic trials within the geroscience framework (disease, function, resilience or frailty, or all of these) and how to synergize efforts with regulators to increase the chances of drug approval, if a gerotherapeutic agent proves to be clinically effective.

It is possible that a treatment will benefit some of the dimensions of intrinsic capacity or frailty but not others, either hindering true effects or inflating them according to the phenotypic composition of the study population. Therefore, careful attention must be paid to the eligibility criteria of participants. Recruiting either fit older adults or individuals with medical conditions that are unlikely to be reversible should be avoided, as the chances for these populations to benefit from the treatment are low. Safety can be an issue because drug–drug interactions are frequent in older adults who are already taking multiple drugs. People with prefrailty and early-stage frailty probably constitute an ideal target population, as they have an increased risk of functional decline but their resilience mechanisms are still potentially strong and can be acted upon. Using an intrinsic capacity composite score that varies from 0 to 100 (ref. 11) from the MAPT trial12 (participants aged ≥70 years old), individuals who were classified as either being prefrail or early-stage frail (two or three of the five Fried criteria, respectively) have lower intrinsic capacity scores (almost 8 and 12 points lower, respectively) than robust participants — differences that can be considered clinically relevant (P.d.S.B. & B.V., unpublished data).

Defining a primary end point is probably the most critical challenge for a gerotherapeutics trial searching for an approvable drug indication. A key question is whether trialists should choose an adverse health event such as a disease (outcomes that are more appreciated by regulatory drug agencies, as illustrated by the fact that the design of the TAME trial — in which the primary end point is a composite of cardiovascular events, cancer, dementia and mortality — has been developed in consultation with the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)13) or look at improving function (outcomes that are more appreciated by geriatricians and other healthcare professionals who deal with older people, and that are of more direct relevance to the lives of older people themselves). Importantly, having an outcome that is important for participants, easy to measure clinically and recognized by clinicians can facilitate the translation from research to clinical practice — particularly if the use of such an outcome is promoted by health authorities. In this context, the domains of intrinsic capacity (that is, locomotion, cognition, psychology, hearing, vision and vitality (nutrition)), as operationalized in the ICOPE program of the WHO, can be considered appropriate outcomes as they are valued by geriatricians and gerontologists, important for patients, and potentially easy to assess in clinical care (as exemplified by the current experience in the French healthcare system14, in which healthcare professionals implementing the ICOPE program are reimbursed). Establishing a composite outcome measure of the main functions that determine healthy aging is particularly suitable for geroscience trials because such an outcome is multidimensional and relies on different physiological systems, all of which are linked to molecular or cellular drivers of aging. The ICD-11 code ‘MG2A Ageing associated decline in intrinsic capacity’ offers a framework for the use of an intrinsic-capacity composite outcome for drug development and potential subsequent approval for targeting healthy longevity. Furthermore, the intrinsic capacity domains assessed in ICOPE can be reproduced in animal models for mechanistic explorations, as exemplified through assessments performed in the INSPIRE animal cohort15.

Final considerations and perspectives

The field of geroscience is rapidly growing, along with the challenges and obstacles that need to be overcome. The geroscience approach elevates the study of frailty and intrinsic capacity to clinical translation by considering that health at the molecular and cellular level translates into healthy longevity for individuals and public health, promoting a function-centered — rather than a disease-centered — approach.

To foster geroscience trials in the field of frailty and intrinsic capacity, Task Force members have proposed a list of recommendations (Box 1). The Task Force members agree that a set of easy-to-measure and inexpensive biomarkers at both mechanism-specific (for example, cell senescence) and overall biological aging (represented by several of the main molecular and cellular drivers of aging) levels should be defined to push geroscience trial development. Focusing on markers of stress response or resilience might be a good start. These markers are more sensitive to change than hard clinical outcomes and could be used as efficacy end points in early trial phases (for example, phase IIa) and constitute preplanned secondary end points in definitive phase III trials. In this context, blood-based markers as well as subclinical functional alterations (for example, small but true changes in mobility and cognition that are not due to normal measurement variation) must compose such a set of biomarkers. For phase III trials, a composite functional measure that considers all of the intrinsic capacity domains illustrated in the WHO ICOPE program constitutes a good alternative to traditionally used disease outcomes. Although it has the potential shortcomings of any composite measure (such as true-positive effects on one of the intrinsic capacity domains being hindered by null or negative effects in other intrinsic capacity domains), such a composite intrinsic-capacity measure has the advantage of being in phase with both the multidimensionality of outcomes that is inherent to the geroscience approach and the current paradigm shift in clinical practice towards function-centered care.

Box 1. Recommendations for fostering geroscience clinical trial development in frailty and intrinsic capacity research.

Recommendation 1

Principal investigators of geroscience trials are encouraged to present their study design and the primary outcome to the FDA and/or EMA to obtain advice.

Recommendation 2

Individuals with late-stage prefrailty or early-stage frailty constitute a good target population as they are at risk of declines in intrinsic capacity, but are resilient enough to respond to interventions. Using the frailty phenotype approach, these individuals can be identified as those who met two or three out of five frailty criteria.

Recommendation 3

It is advisable to use a composite score of intrinsic capacity as a primary end point in clinical trials. Such an end point aligns the field of geroscience with the shift in the clinical-care paradigm towards a function-centered vision of aging. It is important to highlight the intrinsic capacity has an ICD-11 code (‘MG2A Ageing associated decline in intrinsic capacity’), which may facilitate its acceptance as a valid end point by regulatory drug agencies.

Recommendation 4

Research on the biomarkers of resilience, the stress response and adaptation should be further developed and incorporated in clinical trials

Recommendation 5

A set of key biomarkers of aging and resilience should constitute a preplanned end point (primary or secondary, according to the trial phase) in any geroscience clinical trial.

Task Force members recognize the importance of collaborating with regulatory agencies to forge a path forward for geroscience trials. It is crucial that trialists involve representatives of FDA and/or the European Medicines Agency (EMA) in the design of any phase III trial. Ideally, representatives of EMA and FDA must be consulted even in the earliest phases of clinical trials.

By focusing efforts on establishing a set of biomarkers that are representative of the aging process and by working closely with drug agencies, gerotherapeutic trials can pave the way for geriatric medicine of the future that is personalized and preventive.

Acknowledgements

This task force was developed in the context of the Inspire program, a research platform that is supported by grants from the Region Occitanie/Pyrénées-Méditerranée (reference number 1901175) and the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) (project number MP0022856). R.A.F. is partially supported by the US Department of Agriculture (USDA), under agreement no. 58–8050-9–004, by NIH Boston Claude D. Pepper Center (Older Americans Independence Centers; 1P30AG031679). Any opinions, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the view of the USDA. We thank all task force members: S. Andrieu (Toulouse, France), D. Angioni (Toulouse, France), M. Aubertin Leheudre (Montreal, Canada); N. Barcons (Esplugues de Llobregat, Barcelona, Spain), A. Baruch (South San Francisco, USA), M. Camprubi-Robles (Granada, Spain), M. Canevelli (Rome, Italy), M. Cesari (Milan, Italy), L. Chen (Richmond, USA), A. Cherubini (Ancona, Italy), R. Correa-de-Araujo (Bethesda, USA), P. D’Alessio (Evry, France), C. Delannoy (Vevey, Switzerland), W. Dioh (Paris, France), C. Dray (Toulouse, France), W. Evans (Durham, USA), R. Hughes (Richmond, USA), S. Hüttner (Heusden-Zolder, Belgium), J. Justice (Winston-Salem, USA), A. Khachaturian (Rockville, USA), S. Kritchevsky (Winston-Salem, USA), S. LaHue (San Francisco, USA), J. Mariani (Paris, France), M. McCormick (Albuquerque, USA), R. Merchant (Singapore, Singapore), A. Neale (Richmond, USA), J. Newman (Novato, USA), S. Pereira (Columbus, USA), E. Quann (Vevey, Switzerland), J. Yves Reginster (Clarens, Switzerland), L. Rodriguez Manas (Getafe, Spain), M. Rossulek (Cambridge, USA), S. Sourdet (Toulouse, France), B. Stubbs (Novato, USA), J. Touchon (Montpellier, France), C. Tourette (Paris, France) and J. Walston (Baltimore, USA).

Footnotes

Competing interests

P.d.S.B. declares consultancy fees from Pfizer. R.A.F. reports grants, personal fees and stock options from Axcella Health, other from Juvicell, other from Inside Tracker, grants and personal fees from Biophytis, personal fees from Amazentis, personal fees from Nestle, personal fees from Rejuvenate Biomed, personal fees from Pfizer and personal fees from Embion outside the submitted work. B.V. is an investigator in clinical trials at Toulouse University Hospital (IHU HealthAge, Inspire Geroscience Program). He has served as a scientific advisory board (SAB) member for Biogen, Alzheon, Green Valey, Norvo Nordisk and Longeveron, but received no personal compensation. He has served as consultant and/or SAB member for Roche, Lilly, Eisai and TauX with personal compensation. His family members have equity ownership interest in Serd publisher. He is member of the editorial board of the Journal of Prevention of Alzheimer’s Disease with no personal compensation. All of the remaining authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Cesari M. et al. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci 73, 1653–1660 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beard JR et al. Lancet 387, 2145–2154 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dent E. et al. Lancet Lond Engl. 394, 1376–1386 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.WHO. Integrated care for older people (ICOPE): guidance for person-centred assessment and pathways in primary care. who.int, https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-FWC-ALC-19.1 (2019) [Google Scholar]

- 5.Raffaele M. & Vinciguerra M. Lancet Healthy Longev. 3, e67–e77 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vinel C. et al. Nat. Med 24, 1360–1371 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cawthon PM et al. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci 76, 123–130 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roberts MN et al. Cell Metab. 26, 539–546.e5 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim DH et al. Aging 11, 1283–1304 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ostan R. et al. Clin. Nutr 35, 812–818 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lu WH et al. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 14, 930–939 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Andrieu S. et al. Lancet Neurol. 16, 377–389 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barzilai N, Crandall JP, Kritchevsky SB & Espeland MA Cell Metab. 23, 1060–1065 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tavassoli N. et al. Lancet Healthy Longev. 3, e394–e404 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Santin Y. et al. J. Frailty Aging 10, 121–131 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]