Abstract

The many-body expansion (MBE) of the lattice energy enables an ab initio description of molecular solids using correlated wave function approximations. However, the practical application of MBE requires computing the large number of n-body contributions efficiently. To this end, we employ a multi-level coupled-cluster approach which adapts the approximation level based on interaction type and intermolecular distance. The high-level method, including connected triple excitations, is applied only to monomer relaxation and dimer interactions roughly within the first and second coordination shells. Long-range dimers and trimers are treated using a simplified coupled-cluster description based on the random-phase approximation (RPA). A key feature is an energy correction which mitigates the underbinding error of the base RPA. Convergence to the bulk limit is accelerated by the addition of the periodic Hartree–Fock correction. The proposed approach is validated against recent diffusion Monte Carlo reference data for the X23 data set, achieving a mean absolute error of 3.1 kJ/mol, i.e., chemical accuracy for absolute lattice energies.

1. Introduction

First-principles crystal structure prediction (CSP) of molecular solids from the structures of individual molecules is one of the grand challenges of materials science. − A reliable CSP would be a tool to predict the energy landscape of new compounds and to detect kinetically protected metastable states. , Those capabilities are relevant for computer-guided design of organic molecular materials and pharmaceuticals.

Correct energetic ordering of noncovalent systems is a key challenge in CSP. , This work focuses on the static lattice energy, E latt, which typically varies by only a few kilojoules per mole between competing polymorphs of organic molecular crystals. Slight differences in E latt arise from, e.g., interplay between intra- and intermolecular interactions and nonadditive effects. As a result, qualitative predictions of this physical quantity require sophisticated models of dynamic electron correlation.

Dispersion-corrected density functional theory (DFT), typically implemented with periodic boundary conditions (PBC), has become the standard approach for electronic-structure simulations of molecular solids. − A careful selection of the exact exchange admixture and the dispersion model can lead to chemically accurate lattice energies. However, in the cases where DFT methods disagree with each other or deviate from experiment, such as the conformational polymorphs of ortho-acetamidobenzamide and ROY, wave function methods are preferred due to their systematic convergence to the exact result.

There are two distinct ways of how correlated wave function methods are applied in solids: using PBC − or by employing the many-body expansion (MBE). , Diffusion Monte Carlo (DMC), ,, among PBC-based methods, provides most of the benchmark lattice energies available to date. , However, the high computational cost of tightly converged DMC results limits the routine applicability of this approach.

The essence of the MBE approach is to describe periodic systems with the well-established Gaussian basis-set methods designed for molecules. , Consider a molecular crystal with a single symmetry-unique reference molecule in the unit cell (denoted as ref). The lattice energy of this system can be expressed as a sum of interaction energies in n-body clusters, arranged according to the cluster size

| 1 |

The first term on the rhs is the monomer relaxation energy

| 2 |

The contributions that follow describe the noncovalent interactions between the reference molecule and its neighbors: the pairwise interaction energy

| 3 |

the three-body nonadditive interaction energy

| 4 |

and higher-order nonadditive contributions which make the expansion exactly approach the bulk limit. The computation of the high n-body terms is hard, but can be done implicitly by including a low-level periodic correction. −

An advantage of MBE is its compatibility with multi-level wave function approximations. For example, the expensive coupled-cluster method with singles, doubles, and perturbative triples, CCSD(T), , can be limited to short-distance dimers. ,−

The challenge that remains is an efficient description of the remaining long-distance dimer interactions and the thousands of nonadditive contributions. The approximations used for these contributions must be substantially cheaper than conventional coupled-cluster methods, but still capture the essential interactions in many-body molecular assemblies. To this end, second-order Møller–Plesset (MP2) theory supplemented with a dispersion correction has been the method of choice. ,,,, However, MP2 catastrophically overestimates the interactions between polarizable π-electron systems, where Møller–Plesset perturbation theory diverges. −

An alternative approach which is more universal than Møller–Plesset theory, but less expensive than established coupled-cluster methods is the random-phase approximation (RPA). ,, RPA can be thought of as a coupled-cluster approximation where the doubles amplitude equation retains only the direct ring contributions and can be solved in a closed form. The RPA interaction energy correctly reduces to the Casimir-Polder dispersion energy at long separations and accounts for n-body dispersion interactions. ,,, Those features make RPA and beyond-RPA methods , good candidates to apply in the expensive, many-body part of MBE.

This work presents a multi-level MBE for molecular crystals which combines recent advances in high- and low-level coupled-cluster methods: the local natural orbital − (LNO) approximation of CCSD(T) and RPA with coupled-cluster corrections. To account for long-range many-body polarization effects, which are unfeasible for large systems within pure MBE, the coupled-cluster description is augmented with periodic Hartree–Fock, HF(PBC). Validation against canonical CCSD(T) and DMC data, which is presented in the numerical section, enables a detailed assessment of key methodological components: the accuracy of the LNO approximation, the impact of beyond-RPA corrections, and the role of the HF(PBC) correction in converging toward accurate lattice energies.

2. Theory

2.1. Switchover between Levels of Theory

To map a molecular cluster onto an appropriate approximation level, we determine its characteristic distance, R, as follows. For a dimer, R is the shortest atom–atom separation between two molecules. For a trimer, R is the largest of the three intermolecular distances between its constituents. This definition allows us to apply different quantum-chemical approaches in different parts of the system, as shown in Figure .

1.

Partitioning of dimer, trimer, and higher-body contributions to the lattice energy into subsets treated with LNO–CCSD(T), RPA+ph, and periodic HF, based on cluster type and intermolecular distance. A transition between levels of theory occurs if any pair of molecules within a cluster is separated by more than the switchover radius.

As the high-level model of electronic structure, we employ the LNO–CCSD(T) method, − which is a local coupled-cluster approximation with proven performance for noncovalent interaction energies. The high-level approach is limited to the monomer relaxation and dimer interaction energies below the switchover distance

| 5 |

This value of R dimers is suggested for wave function approaches in ref and corresponds to, roughly, the distance of the second nearest-neighbors shell. Further extension of the high-level region has a diminishing effect on the accuracy, as we show in the results section.

The low-level description of electron correlation encompasses long-distance dimers with

| 6 |

and all nonadditive trimer energies within the cutoff radius of

| 7 |

In the data set considered in this work, the cutoffs defined in eqs and correspond to a few hundred symmetry-unique dimers and roughly ten thousand trimers, as shown in refs , . The electronic structure model applied in the low-level region is RPA with beyond-RPA corrections. Even though this approach is more efficient than conventional coupled-cluster methodology, further extension of R dimers and R trimers is prohibitively expensive.

In polar molecules, extremely long-range interactions might occur due to polarization by static multipoles, for example, as in trimers of formamide at R = 20 Å. However, the existing results for ice and methanol indicate that those poorly convergent contributions are, essentially, mean-field effects and can be effectively captured by the energy difference

| 8 |

where HF(PBC) is the periodic HF total lattice energy and HF(MBE) is a truncated MBE with monomer, dimer, and trimer contributions. Therefore, to extend the applicability of the multi-level approach to polar systems, we supplement the computational protocol with a plane-wave HF calculation of the molecular solid and include ΔHF(PBC) in the total lattice energy. This formally introduces interactions up to infinite distance and all many-body nonadditive energies beyond trimers, albeit without electron correlation.

2.2. Low-Level Correlation: RPA with Corrections

We present the essential details of the low-level coupled-cluster approach, referred to as the beyond-RPA method, based on ref and applied here with modifications related to the treatment of the antisymmetrized Coulomb interactions. The beyond-RPA approximation follows from the definition of the total electronic energy

| 9 |

where E HF is the self-consistent Hartree–Fock energy and the exact correlation energy, E c, is formulated as the coupled-cluster expectation value of the normal-ordered Hamiltonian H N

| 10 |

The correlated wave function is parametrized by the cluster excitation operator, T, acting on the Hartree–Fock state Ψ0. By the linked-cluster theorem ,

| 11 |

where the curly braces with “C” denote a sum over all fully contracted terms connected to H N.

For a given source of the amplitudes, T, a truncation of the rhs of eq defines an approximation of the correlation energy. To proceed, assume that (i) the amplitudes in eq are restricted to double excitations and originate from the direct-ring coupled-cluster doubles equation, (ii) the direct-ring terms are summed up to infinity, (iii) the remaining non-ring contributions are retained only through the terms quadratic in T. These conditions yield

| 12 |

where the terms on the rhs are, respectively, the conventional RPA correlation energy, the particle-hole (ph) corrections, and the particle–particle/hole–hole (pp/hh) corrections defined as

| 13 |

and

| 14 |

Detailed expressions for these terms are provided in Table .

1. Contributions in the Expansion of the Beyond-RPA Correlation Energy up to Terms Quadratic in the RPA Double Excitation Amplitudes T .

| ph contributions | pp/hh contributions |

|---|---|

| ERPAc = 2∑ aibj (ai|bj) T ij E c = −∑ aibj (ai|bj) T ji | E2e c = 2∑aibjkl (ij|kl) T ik T lj |

| E2b c = −4∑ aibjck (ai|bj) T ik T jk E c = 2∑ aibjck (ai|bj) T ki T jk | E2f c = −∑ aibjkl (ij|kl)T ik T jl |

| E2g c = −4∑ aibjck (ij|ab) T jk T ki E c = −4∑ aibjck (ij|ab) T kj T ik | E2k c = 2∑ aibjcd (ab|cd) T ij T ji |

| E2i c = 2∑ aibjck (ij|ab) T jk T ik | E2l c = −∑ aibjcd (ab|cd) T ij T ij |

The terms are divided into the particle-hole (ph) and particle-particle/hole–hole (pp/hh) subsets according to the type of the Coulomb integral contracted with the 2-electron reduced density matrix (2-RDM).

Let us define various approximations which can be formed by the terms on the rhs of eq . The physical content of those approximations is summarized in Figure . The base RPA energy contains only the direct-ring contribution,

| 15 |

While efficient, E c lacks proper antisymmetry and introduces the exclusion-principle violating (EPV) terms, which propagate identical single-particle states at equal times. Corrections beyond E RPA should remove those unphysical terms.

2.

Perturbation theory expansion of RPA-based models of the correlation energy. Solid color corresponds to diagrams included with the exact prefactor at a given approximation level. Dashed colored bars correspond to incomplete and non-antisymmetric contributions. The convention of ref is used: dashed lines represent antisymmetrized Coulomb integrals and solid horizontal lines are energy denominators.

The simplest approach which goes beyond RPA is the second-order screened exchange correction (SOSEX), , where the energy

| 16 |

is free from the EPVs up to the second order of perturbation theory. , Still, when applied with the self-consistent HF orbitals, RPA and RPA+SOSEX interaction energies differ only by a marginal amount.

Third-order corrections are expected to have a much stronger impact on noncovalent interactions than SOSEX. ,, Here, these corrections are introduced by E c and E c . In the most complete formulation

| 17 |

which reproduces the exact perturbation theory expansion through third order. However, a major drawback of this approximation is the high cost associated with Coulomb integrals involving four virtual indices in the E c and E c contributions from E c . Thus, we will avoid this approach except for a few numerical tests which illustrate the magnitude of the pp/hh contribution in noncovalent systems.

A more practical approach balancing accuracy and cost retains only ph-type corrections

| 18 |

As illustrated in Figure , while E RPA+ph neglects the third-order pp and hh diagrams, it accounts for the ph diagram with its exact prefactor and proper antisymmetry.

In what follows, RPA+ph will serve as the lower-level correlated electronic structure method in the multi-level approach. This choice is supported by the numerical data shown in Section 2 of Supporting Information, which illustrate that the numerical differences between the efficient variant, RPA+ph, and the full variant, RPA+ph+pp/hh, are small and do not justify the extra computational cost.

2.3. Implementation Details

Due to the need to compute thousands of nonadditive trimer interactions, the low-level correlated step is best carried out with a highly customized implementation designed to balance efficiency and numerical stabilitya fundamental challenge for MBE. Our beyond-rpa program achieves this goal by extensive use of tensor factorization techniques with tight numerical thresholds and automated estimation of the numerical error in the interaction energy.

The beyond-RPA post-SCF phase starts with evaluation of the RPA doubles amplitudes from the closed formula derived in ref . Two types of low-rank factorizations are carried out in succession. First, during the amplitude generation step, the amplitudes are computed from eq 38 of ref by assembling the eigenvectors U ai,μ and eigenvalues a μ up to the cutoff threshold εEVD

| 19 |

Computational cost is reduced since the number of significant eigenpairs scales linearly with system size for a given error tolerance.

The second type of low-rank decomposition is a modified, SVD-based variant of the pair natural orbital (PNO) factorization presented in ref . The algorithm proceeds as follows. (i) First, the occupied indices i and j are transformed to the localized basis with the Boys-Foster procedure. , (ii) The amplitude matrix, T ij , is aligned in memory as a quantity with free virtual indices a and b and fixed occupied indices i and j. (iii) The SVD rank reduction of such N virt × N virt matrix is executed up to the PNO threshold εPNO. The resulting truncated expansion is

| 20 |

where P (ij) and Q (ij) are the singular vector matrices and σ x is the xth singular value belonging to the occupied pair ij. For the systems discussed in the numerical section, we have verified that the number of significant PNOs depends weakly on the system size.

Once the PNOs are available, the ph beyond-RPA correction to the correlation energy is obtained as

| 21 |

where two kinds of reduced density-like intermediates are used: (i) G ijab gathers the contractions present in E c + E c + 2 E c

| 22 |

whereas (ii) G aibj accounts for E c + E c

| 23 |

The intermediates in eqs and are the overlap matrix between PNOs

| 24 |

and rescaled right singular vectors

| 25 |

The indices x and y traverse the PNO sets of the respective occupied pairs. The formulation given in eqs – reduces to dot products and matrix multiplications. Consequently, computing E c achieves near-perfect utilization of modern hardware, which is highly optimized for basic linear algebra operations.

A unique feature of the RPA-based formalism is that numerical errors from the low-rank decomposition of T can be estimated at a negligible cost. As we have verified, a good estimate of the numerical error in the total correlation energy is the error in the inexpensive E c component. This error estimate is determined by recomputing E c in two ways: (i) exactly, using the density response function and integration over frequencies and (ii) approximately, using T-dependent formula for E c from Table and decomposed amplitudes. The difference between these values provides an error estimate for interaction energies. The extra cost is negligible because the intermediates required for the accurate E c are already available during the computation of T.

3. Results

3.1. Computational Details

The multi-level approach involves three kinds of electronic single-point computations performed with different computer software: (i) LNO–CCSD(T) for the monomers and short-range dimers, (ii) RPA with corrections for the long-range dimers and all trimers, (iii) and HF with periodic boundary conditions for the remaining physical contributions. The LNO–CCSD(T) calculations were performed using the MRCC program, version from August 28, 2023, with the tightest available numerical settings (vvTight) unless noted otherwise. The RPA and beyond-RPA energies were evaluated using the beyond-rpa program developed as a part of this work and available at GitHub. Molecular cluster extraction from crystal supercells and input preparation for MBE calculations were performed using our customized Python script, mbe-automation, which integrates components from the open source programs ase, crystalatte, and membed.

All RPA-based correlation energy expressions were evaluated using HF orbitals and orbital energies. The HF self-consistent field calculations which precede the RPA step were accelerated by the THC decomposition of the Coulomb integrals. , THC-related numerical errors were eliminated perturbatively by a single post-SCF re-evaluation of the Fock Hamiltonian with the exact integrals. Both LNO–CCSD(T) and RPA employed Duning’s triple- and quadruple-ζ correlation-consistent basis sets augmented with diffuse functions (see details in Section 1 of Supporting Information). All dimer and trimer energies were counterpoise-corrected with ghost atoms placed within each molecular cluster. The periodic HF calculations were carried out with VASP − using the projector augmented wave method , (PAW) with “standard” data sets and the plane-wave energy cutoff at 1100 eV. We applied the Coulomb cutoff technique (HFRCUT keyword in VASP), along with a dense k-point sampling for crystals and large cell sizes for molecules to achieve converged energy values without explicit extrapolation. Further details necessary to reproduce our calculations are summarized in Section 1 of Supporting Information.

3.2. Validation on the X23 Data Set

The X23 data set contains crystal structures of small, rigid molecules that vary in their dominant interaction types and total lattice energy values ranging from −29 kJ/mol for CO2 to −156 kJ/mol for cytosine. The systems are well-characterized both experimentally and computationally, with available reference sublimation enthalpies, ,, total lattice energies, and isolated two- and three-body contributions. , The best theoretical estimates of the X23 data, that is, the DMC values of ref , are consistent with the experiment within the experimental error range.

3.2.1. Two-Body Contributions

Pairwise interactions dominate the lattice energy (Figure ), making it essential to control uncertainties in the two-body contribution: (i) errors from switching between LNO–CCSD(T) and RPA+ph, (ii) LNO approximation errors, and (iii) incomplete convergence with distance. Our goal is to keep these uncertainties below 1 kJ/mol.

3.

Overview of the MBE contributions to the crystal lattice energy in the entire X23 data set. The energies are obtained using the multi-level approach. The boxes extend from the first to the third quartile, and the whiskers extend from the minimum to the maximum energy. The HF(PBC) embedding accounts for the sum of extremely long-distance contributions and the nonadditive terms beyond trimers.

A subset of ten X23 systems was selected to compare multi-level two-body lattice energies against canonical CCSD(T) data of Sargent et al. Figure shows how errors vary with the switchover distance and the choice of low-level correlation. In the case where only the low-level method is used for all distances, conventional RPA errors range from 7 kJ/mol (ammonia) to over 30 kJ/mol (hexamine). The SOSEX correction is negligible, while the ph correction significantly improves results, reducing errors by a factor of 3. However, achieving the 1 kJ/mol target requires connected triples at short distances. The combination of canonical CCSD(T) and RPA+ph with R dimers = 7 Åthe switchover distance in our multi-level approachmeets this accuracy target.

4.

Dimer contribution to the crystal lattice energy for various choices of the switchover distance. A/B denotes a multi-level approach where method A is used for R < R dimers and B is applied for the remaining dimers at R dimers ≤ R < 30 Å. The canonical CCSD(T) energies are taken from ref .

Substituting canonical CCSD(T) for LNO–CCSD(T) introduces additional, locality-related errors (Figure ). For example, at the vTight level of accuracy settings, the numerical errors exceed 1 kJ/mol in succinic acid and trioxane. However, using the tightest available thresholds (vvTight), the approach adopted in our multi-level protocol, makes LNO–CCSD(T)/RPA+ph practically equivalent to CCSD(T)/RPA+ph.

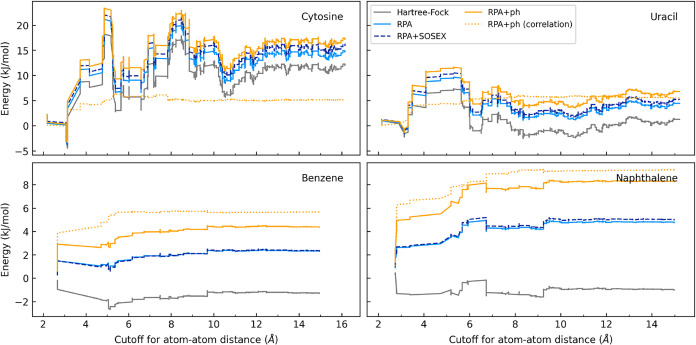

The two-body errors due to incomplete distance convergence are negligible. As shown in Figure and Section 5 of Supporting Information, the interaction energy curves plateau at 10 Å for dispersion-bonded systems and 15 Å for polar molecules, far before the R dimers = 30 Å cutoff applied in our approach.

5.

Two-body contribution to the crystal lattice energy as a function of the cutoff distance. The energies are accumulated up to a given cutoff radius, defined as the maximum atom–atom distance between molecules. The dotted line corresponds to the correlation energy component of the total RPA+ph energy.

3.2.2. Three-Body Contributions

The nonadditive three-body energy is typically an order of magnitude smaller than the two-body term (Figure ). Still, neglecting this contribution would lead to a significant error in the total energy and possibly an incorrect ordering of polymorphs. For example, in 1,4-cyclohexanedione, anthracene, cytosine, oxalic acid α, urea, and succinic acid the three-body term exceeds 10 kJ/mol at the RPA+ph level (Section 6 in Supporting Information). In oxalic acid, the three-body nonadditive energy changes sign between the α and β polymorphs, directly influencing their relative stability. In the context of the multi-level approach, this necessitates a sufficient treatment of electron correlation and tight convergence with the cutoff distance. A reasonable error tolerance is 1 kJ/mol and the correct sign in the cases with small three-body contributions.

Let us consider two systems from the X23 set for which the reference CBS-extrapolated canonical CCSD(T) data are available: benzene and acetic acid. When applied for all distances, RPA underestimates the three-body term by 1.5 kJ/mol for benzene and 0.6 kJ/mol for acetic acid (Figure ). Adding the SOSEX correction has a negligible effect. By contrast, the RPA+ph variant overestimates the three-body energies by only about 0.5 kJ/mol in both systems. This result provides a rough estimate of the three-body error in our protocol, where RPA+ph is applied for all trimers without any high-level corrections.

6.

Error in the nonadditive three-body interaction energy as a function of the switchover distance between CCSD(T) and RPA-based approximations. The CBS-extrapolated canonical CCSD(T) energies are taken from ref and . A/B denotes a multi-level approximation, where A is used below the switchover distance and B is applied for all remaining distances up to 15 Å.

An important source of three-body errors is an incomplete convergence with distance. As shown in Figure , three-body interactions in dispersion-bound systems (benzene, naphthalene) stabilize around 10 Å, whereas in polar systems (cytosine, uracil), significant fluctuations persist even at 15 Å. Capturing such long-distance contributions using MBE is computationally not feasible. However, an inspection of Figure reveals that the correlation-only three-body energy in polar systems converges fast, at a rate comparable to that of the total energy curve in nonpolar systems. Thus, the poorly convergent long-range fluctuations reside in the Hartree–Fock termsupporting the inclusion of the periodic Hartree–Fock correction, ΔHF(PBC), in the multi-level lattice energy.

7.

Nonadditive three-body contribution to the crystal lattice energy as a function of the cutoff distance. The energies are accumulated up to a given cutoff radius, defined as the maximum atom–atom distance between constituent molecules in a trimer. The dotted line corresponds to the correlation energy component of the total RPA+ph energy.

3.2.3. Total Lattice Energy

The main result of this work is demonstrated in Figure , where, upon refinement of the theoretical model, the multi-level lattice energies systematically converge toward the reference DMC values within chemical accuracy of approximately ± 4 kJ/mol. This level of agreement with the reference is achieved in consecutive steps by the inclusion of (i) the RPA correlation, (ii) beyond-RPA corrections, (iii) LNO–CCSD(T) for the monomer relaxation and short-distance dimers, and (iv) the HF(PBC) embedding, each with a visible effect on the average and/or the spread of signed errors. At the RPA correlated level, with MBE encompassing monomers, dimers, and trimers, the total lattice energy is severely underestimated (mean absolute error, MAE = 22.0 kJ/mol). Adding the SOSEX correction has a negligible influence, slightly decreasing MAE to 20.6 kJ/mol. The inclusion of the ph beyond-RPA corrections decreases the average error to 6.9 kJ/mol, mostly due to improved two-body interactions, as shown in Section . The remaining underbinding error is eliminated upon addition of connected triple excitations in the nearest dimers. In the LNO–CCSD(T)/RPA+ph multi-level approach, the errors are distributed evenly around zero with MAE = 3.5 kJ/mol and RMSE = 4.8 kJ/mol. Still, some outliers remain, such as trioxane, for which the energy is underestimated by 12.7 kJ/mol, likely due to the missing contributions from the four- and higher-body nonadditive interactions.

8.

Convergence of the crystal lattice energy toward the accurate value in a series of electronic-structure approximations. The abscissa represents the features added to the multi-level approximation at each step. The HF(PBC) embedding accounts for interactions at R ≥ R HF and n > 3-body terms. The signed errors are computed against the reference DMC energies from ref .

The final step in the multi-level protocol adds the periodic HF correction, which is an estimate of the physical contributions missing from the truncated MBE. The resulting multi-level lattice energies, presented in Table , show further improvement. The error measures for the complete protocol are MAE = 3.1 kJ/mol and RMSE = 4.2 kJ/mol. The signed errors indicate overbinding relative to the DMC reference, with two notable cases outside of the ±4 kJ/mol window: naphthalene and anthracene. Further investigation is needed to determine to what degree these errors stem from a systematic discrepancy between CCSD(T) and DMC in large π–electron systems. , Part of the error in the multi-level protocol arises from using standard PAW potentials , in the HF(PBC) contribution, likely affecting polar systems the most. , A correction, such as the one defined in eq 1 of ref , should be applied to eliminate this error.

2. Total Lattice Energies (kJ/mol) in the X23 Data Set.

| system | multi-level | DMC |

|---|---|---|

| 1,4-cyclohexanedione | –94.4 | –88.3 |

| acetic acid | –71.2 | –71.7 |

| adamantane | –66.0 | –61.0 |

| ammonia | –37.6 | –38.2 |

| anthracene | –111.4 | –100.2 |

| benzene | –51.6 | –49.8 |

| CO2 | –29.4 | –29.4 |

| cyanamide | –82.6 | –83.6 |

| cytosine | –163.1 | –156.2 |

| ethyl carbamate | –86.5 | –84.2 |

| formamide | –84.0 | –81.0 |

| imidazole | –88.4 | –88.2 |

| naphthalene | –82.5 | –75.5 |

| oxalic acid α | –103.0 | –102.6 |

| oxalic acid β | –101.6 | –102.3 |

| pyrazine | –64.3 | –61.1 |

| pyrazole | –79.3 | –77.3 |

| triazine | –60.3 | –60.5 |

| trioxane | –67.8 | –62.1 |

| uracil | –139.7 | –134.3 |

| urea | –111.0 | –108.5 |

| hexamine | –88.0 | –86.2 |

| succinic acid | –128.2 | –125.2 |

| MAE | 3.1 | |

| RMSE | 4.2 | |

| MSE | –2.8 |

4. Conclusions

We have presented a multi-level MBE approximation of the crystal lattice energy based on coupled-cluster wave function models: LNO–CCSD(T) (high level) and RPA+ph (low level). The LNO–CCSD(T) approximation is applied only for monomer relaxation and dimers at R < 7 Å, roughly within the first two coordination shells. This provides good accuracy for the dominant part of the lattice energy while limiting the expensive approach to a manageable number of subsystems. The remaining contribution from long-range dimers and trimers is treated with the RPA-based methodthe simplest correlated wave function approximation which qualitatively represents many-body dispersion interactions. Conventional RPA is refined with beyond-RPA corrections, which mitigate the underestimation of pairwise interactions. Finally, the periodic Hartree–Fock correction is included to accelerate convergence to the bulk limit. Each component of the computational protocol systematically improves the accuracy of lattice energies for the X23 set of molecular solids. The final mean absolute error, 3.1 kJ/mol, is within the chemical accuracy target. This result supports the use of the beyond-RPA approach as a low-level correlated component in multi-level schemes based on coupled-cluster theory.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research has been conducted using the infrastructure of Poznan Supercomputing and Networking Center. We gratefully acknowledge Polish high-performance computing infrastructure PLGrid (HPC Center: ACK Cyfronet AGH) for providing computer facilities and support within computational grant no. PLG/2024/017368. The authors thank Dominik Cieśliński, Jakub Lang, and Aleksandra Tucholska for fruitful discussions.

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.jctc.5c00428.

Additional plots and tables with raw numerical data; atomic coordinates, basis sets, and LNO coupled-cluster numerical settings applied in the multi-level calculations; details of the periodic Hartree-Fock calculations (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Maddox J.. Crystals from first principles. Nature. 1988;335:201. doi: 10.1038/335201a0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reilly A. M., Cooper R. I., Adjiman C. S., Bhattacharya S., Boese A. D., Brandenburg J. G., Bygrave P. J., Bylsma R., Campbell J. E., Car R., Case D. H., Chadha R., Cole J. C., Cosburn K., Cuppen H. M., Curtis F., Day G. M., DiStasio R. A. Jr, Dzyabchenko A., van Eijck B. P., Elking D. M., van den Ende J. A., Facelli J. C., Ferraro M. B., Fusti-Molnar L., Gatsiou C.-A., Gee T. S., de Gelder R., Ghiringhelli L. M., Goto H., Grimme S., Guo R., Hofmann D. W. M., Hoja J., Hylton R. K., Iuzzolino L., Jankiewicz W., de Jong D. T., Kendrick J., de Klerk N. J. J., Ko H.-Y., Kuleshova L. N., Li X., Lohani S., Leusen F. J. J., Lund A. M., Lv J., Ma Y., Marom N., Masunov A. E., McCabe P., McMahon D. P., Meekes H., Metz M. P., Misquitta A. J., Mohamed S., Monserrat B., Needs R. J., Neumann M. A., Nyman J., Obata S., Oberhofer H., Oganov A. R., Orendt A. M., Pagola G. I., Pantelides C. C., Pickard C. J., Podeszwa R., Price L. S., Price S. L., Pulido A., Read M. G., Reuter K., Schneider E., Schober C., Shields G. P., Singh P., Sugden I. J., Szalewicz K., Taylor C. R., Tkatchenko A., Tuckerman M. E., Vacarro F., Vasileiadis M., Vazquez-Mayagoitia A., Vogt L., Wang Y., Watson R. E., de Wijs G. A., Yang J., Zhu Q., Groom C. R.. Report on the sixth blind test of organic crystal structure prediction methods. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. B:Struct. Sci., Cryst. Eng. Mater. 2016;72:439–459. doi: 10.1107/S2052520616007447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunnisett L. M., Nyman J., Francia N., Abraham N. S., Adjiman C. S., Aitipamula S., Alkhidir T., Almehairbi M., Anelli A., Anstine D. M., Anthony J. E., Arnold J. E., Bahrami F., Bellucci M. A., Bhardwaj R. M., Bier I., Bis J. A., Boese A. D., Bowskill D. H., Bramley J., Brandenburg J. G., Braun D. E., Butler P. W. V., Cadden J., Carino S., Chan E. J., Chang C., Cheng B., Clarke S. M., Coles S. J., Cooper R. I., Couch R., Cuadrado R., Darden T., Day G. M., Dietrich H., Ding Y., DiPasquale A., Dhokale B., van Eijck B. P., Elsegood M. R. J., Firaha D., Fu W., Fukuzawa K., Glover J., Goto H., Greenwell C., Guo R., Harter J., Helfferich J., Hofmann D. W. M., Hoja J., Hone J., Hong R., Hutchison G., Ikabata Y., Isayev O., Ishaque O., Jain V., Jin Y., Jing A., Johnson E. R., Jones I., Jose K. V. J., Kabova E. A., Keates A., Kelly P. F., Khakimov D., Konstantinopoulos S., Kuleshova L. N., Li H., Lin X., List A., Liu C., Liu Y. M., Liu Z., Liu Z.-P., Lubach J. W., Marom N., Maryewski A. A., Matsui H., Mattei A., Mayo R. A., Melkumov J. W., Mohamed S., Momenzadeh Abardeh Z., Muddana H. S., Nakayama N., Nayal K. S., Neumann M. A., Nikhar R., Obata S., O’Connor D., Oganov A. R., Okuwaki K., Otero-de-la Roza A., Pantelides C. C., Parkin S., Pickard C. J., Pilia L., Pivina T., Podeszwa R., Price A. J. A., Price L. S., Price S. L., Probert M. R., Pulido A., Ramteke G. R., Rehman A. U., Reutzel-Edens S. M., Rogal J., Ross M. J., Rumson A. F., Sadiq G., Saeed Z. M., Salimi A., Salvalaglio M., de Almada L. S., Sasikumar K., Sekharan S., Shang C., Shankland K., Shinohara K., Shi B., Shi X., Skillman A. G., Song H., Strasser N., van de Streek J., Sugden I. J., Sun G., Szalewicz K., Tan B. I., Tan L., Tarczynski F., Taylor C. R., Tkatchenko A., Tom R., Tuckerman M. E., Utsumi Y., Vogt-Maranto L., Weatherston J., Wilkinson L. J., Willacy R. D., Wojtas L., Woollam G. R., Yang Z., Yonemochi E., Yue X., Zeng Q., Zhang Y., Zhou T., Zhou Y., Zubatyuk R., Cole J. C.. The seventh blind test of crystal structure prediction: structure generation methods. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. B:Struct. Sci., Cryst. Eng. Mater. 2024;80:517–547. doi: 10.1107/S2052520624007492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bučar D., Lancaster R. W., Bernstein J.. Disappearing polymorphs revisited. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015;54:6972–6993. doi: 10.1002/anie.201410356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann M. A., van de Streek J.. How many ritonavir cases are there still out there? Faraday Discuss. 2018;211:441–458. doi: 10.1039/C8FD00069G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Firaha D., Liu Y. M., van de Streek J., Sasikumar K., Dietrich H., Helfferich J., Aerts L., Braun D. E., Broo A., DiPasquale A. G., Lee A. Y., Le Meur S., Nilsson Lill S. O., Lunsmann W. J., Mattei A., Muglia P., Putra O. D., Raoui M., Reutzel-Edens S. M., Rome S., Sheikh A. Y., Tkatchenko A., Woollam G. R., Neumann M. A.. Predicting crystal form stability under real-world conditions. Nature. 2023;623:324. doi: 10.1038/s41586-023-06587-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyman J., Day G. M.. Static and lattice vibrational energy differences between polymorphs. CrystEngComm. 2015;17:5154–5165. doi: 10.1039/C5CE00045A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwell C., McKinley J. L., Zhang P., Zeng Q., Sun G., Li B., Wen S., Beran G. J.. Overcoming the difficulties of predicting conformational polymorph energetics in molecular crystals via correlated wavefunction methods. Chem. Sci. 2020;11:2200–2214. doi: 10.1039/C9SC05689K. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermann J., DiStasio R. A. Jr., Tkatchenko A.. First-Principles Models for van der Waals Interactions in Molecules and Materials: Concepts, Theory, and Applications. Chem. Rev. 2017;117:4714–4758. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimme S., Hansen A., Brandenburg J. G., Bannwarth C.. Dispersion-corrected mean-field electronic structure methods. Chem. Rev. 2016;116:5105–5154. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandenburg J. G., Grimme S.. Organic crystal polymorphism: a benchmark for dispersion-corrected mean-field electronic structure methods. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. B:Struct. Sci., Cryst. Eng. Mater. 2016;72:502–513. doi: 10.1107/S2052520616007885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittleton S. R., Otero-De-La-Roza A., Johnson E. R.. Exchange-hole dipole dispersion model for accurate energy ranking in molecular crystal structure prediction. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2017;13:441–450. doi: 10.1021/acs.jctc.6b00679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otero-De-La-Roza A., Johnson E. R.. A benchmark for non-covalent interactions in solids. J. Chem. Phys. 2012;137:054103. doi: 10.1063/1.4738961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reilly A. M., Tkatchenko A.. Seamless and accurate modeling of organic molecular materials. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2013;4:1028–1033. doi: 10.1021/jz400226x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reilly A. M., Tkatchenko A.. Understanding the role of vibrations, exact exchange, and many-body van der Waals interactions in the cohesive properties of molecular crystals. J. Chem. Phys. 2013;139:024705. doi: 10.1063/1.4812819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price A. J. A., Otero-de-la Roza A., Johnson E. R.. XDM-corrected hybrid DFT with numerical atomic orbitals predicts molecular crystal lattice energies with unprecedented accuracy. Chem. Sci. 2023;14:1252–1262. doi: 10.1039/D2SC05997E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J., Hu W., Usvyat D., Matthews D., Schütz M., Chan G. K.-L.. Ab initio determination of the crystalline benzene lattice energy to sub-kilojoule/mol accuracy. Science. 2014;345:640–643. doi: 10.1126/science.1254419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth G. H., Grüneis A., Kresse G., Alavi A.. Towards an exact description of electronic wavefunctions in real solids. Nature. 2013;493:365–370. doi: 10.1038/nature11770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye H.-Z., Berkelbach T. C.. Periodic Local Coupled-Cluster Theory for Insulators and Metals. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2024;20:8948–8959. doi: 10.1021/acs.jctc.4c00936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zen A., Brandenburg J. G., Klimes J., Tkatchenko A., Alfe D., Michaelides A.. Fast and accurate quantum Monte Carlo for molecular crystals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2018;115:1724–1729. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1715434115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beran G. J. O.. Modeling polymorphic molecular crystals with electronic structure theory. Chem. Rev. 2016;116:5567–5613. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman K. M., Xantheas S. S.. A formulation of the many-body expansion (MBE) for periodic systems: Application to several ice phases. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2023;14:989–999. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpclett.2c03822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hongo K., Watson M. A., Iitaka T., Aspuru-Guzik A., Maezono R.. Diffusion Monte Carlo study of para-diiodobenzene polymorphism revisited. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2015;11:907–917. doi: 10.1021/ct500401p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pia F., Zen A., Alfè D., Michaelides A.. How accurate are simulations and experiments for the lattice energies of molecular crystals? Phys. Rev. Lett. 2024;133:046401. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.133.046401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bygrave P. J., Allan N., Manby F.. The embedded many-body expansion for energetics of molecular crystals. J. Chem. Phys. 2012;137:164102. doi: 10.1063/1.4759079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Červinka C., Fulem M., Ržička K.. CCSD (T)/CBS fragment-based calculations of lattice energy of molecular crystals. J. Chem. Phys. 2016;144:064505. doi: 10.1063/1.4941055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richard R. M., Lao K. U., Herbert J. M.. Understanding the many-body expansion for large systems. I. Precision considerations. J. Chem. Phys. 2014;141:014108. doi: 10.1063/1.4885846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermann A., Schwerdtfeger P.. Ground-State Properties of Crystalline Ice from Periodic Hartree-Fock Calculations and a Coupled-Cluster-Based Many-Body Decomposition of the Correlation Energy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008;101:183005. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.101.183005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Červinka C., Beran G. J. O.. Ab initio prediction of the polymorph phase diagram for crystalline methanol. Chem. Sci. 2018;9:4622–4629. doi: 10.1039/C8SC01237G. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loboda O. A., Dolgonos G. A., Boese A. D.. Towards hybrid density functional calculations of molecular crystals via fragment-based methods. J. Chem. Phys. 2018;149:124104. doi: 10.1063/1.5046908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoja J., List A., Boese A. D.. Multimer Embedding Approach for Molecular Crystals up to Harmonic Vibrational Properties. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2024;20:357–367. doi: 10.1021/acs.jctc.3c01082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raghavachari K., Trucks G. W., Pople J. A., Head-Gordon M.. A fifth-order perturbation comparison of electron correlation theories. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1989;157:479–483. doi: 10.1016/S0009-2614(89)87395-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shavitt, I. ; Bartlett, R. J. . Many-Body Methods in Chemistry and Physics: MBPT and Coupled-Cluster Theory. In Cambridge Molecular Science; Cambridge University Press, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Tschumper G. S.. Multicentered integrated QM:QM methods for weakly bound clusters: An efficient and accurate 2-body: many-body treatment of hydrogen bonding and van der Waals interactions. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2006;427:185–191. doi: 10.1016/j.cplett.2006.06.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beran G. J. O., Nanda K.. Predicting organic crystal lattice energies with chemical accuracy. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2010;1:3480–3487. doi: 10.1021/jz101383z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sargent C. T., Metcalf D. P., Glick Z. L., Borca C. H., Sherrill C. D.. Benchmarking two-body contributions to crystal lattice energies and a range-dependent assessment of approximate methods. J. Chem. Phys. 2023;158:054112. doi: 10.1063/5.0141872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson P. M., Sherrill C. D.. Convergence of the many-body expansion with respect to distance cutoffs in crystals of polar molecules: Acetic acid, formamide, and imidazole. J. Chem. Phys. 2024;161:214105. doi: 10.1063/5.0234883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobson J. F.. Beyond pairwise additivity in London dispersion interactions. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 2014;114:1157. doi: 10.1002/qua.24635. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y., Shao Y., Beran G. J.. Accelerating MP2C dispersion corrections for dimers and molecular crystals. J. Chem. Phys. 2013;138:224112. doi: 10.1063/1.4809981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Y., Glick Z. L., Sherrill C. D.. Assessment of three-body dispersion models against coupled-cluster benchmarks for crystalline benzene, carbon dioxide, and triazine. J. Chem. Phys. 2023;158:094110. doi: 10.1063/5.0143712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen B. D., Chen G. P., Agee M. M., Burow A. M., Tang M. P., Furche F.. Divergence of many-body perturbation theory for noncovalent interactions of large molecules. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2020;16:2258–2273. doi: 10.1021/acs.jctc.9b01176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen B. D., Hernandez D. J., Flores E. V., Furche F.. Dispersion size-consistency. Electron. Struct. 2022;4:014003. doi: 10.1088/2516-1075/ac495b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liang Y. H., Ye H.-Z., Berkelbach T. C.. Can Spin-Component Scaled MP2 Achieve kJ/mol Accuracy for Cohesive Energies of Molecular Crystals? J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2023;14:10435–10441. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpclett.3c02411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobson, J. F. Fundamentals of Time-Dependent Density Functional Theory; Marques, M. A. ; Maitra, N. T. ; Nogueira, F. M. ; Gross, E. ; Rubio, A. , Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2012; pp 417–441. [Google Scholar]

- Dobson J. F., Gould T.. Calculation of dispersion energies. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter. 2012;24:073201. doi: 10.1088/0953-8984/24/7/073201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scuseria G. E., Henderson T. M., Sorensen D. C.. The ground state correlation energy of the random phase approximation from a ring coupled cluster doubles approach. J. Chem. Phys. 2008;129:231101. doi: 10.1063/1.3043729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cieśliński D., Tucholska A. M., Modrzejewski M.. Post-Kohn-Sham random-phase approximation and correction terms in the expectation-value coupled-cluster formulation. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2023;19:6619–6639. doi: 10.1021/acs.jctc.3c00496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modrzejewski M., Yourdkhani S., Śmiga S., Klimes J.. Random-phase approximation in many-body noncovalent systems: Methane in a dodecahedral water cage. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2021;17:804–817. doi: 10.1021/acs.jctc.0c00966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pham K. N., Modrzejewski M., Klimeš J.. Contributions beyond direct random-phase approximation in the binding energy of solid ethane, ethylene, and acetylene. J. Chem. Phys. 2024;160:224101. doi: 10.1063/5.0207090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagy P. R., Kállay M.. Approaching the basis set limit of CCSD(T) energies for large molecules with local natural orbital coupled-cluster methods. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2019;15:5275–5298. doi: 10.1021/acs.jctc.9b00511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagy P. R.. State-of-the-art local correlation methods enable affordable gold standard quantum chemistry for up to hundreds of atoms. Chem. Sci. 2024;15:14556–14584. doi: 10.1039/D4SC04755A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagy P. R., Gyevi-Nagy L., Lörincz B. D., Kállay M.. Pursuing the basis set limit of CCSD(T) non-covalent interaction energies for medium-sized complexes: case study on the S66 compilation. Mol. Phys. 2023;121:e2109526. doi: 10.1080/00268976.2022.2109526. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Santra G., Semidalas E., Mehta N., Karton A., Martin J. M.. S66×8 noncovalent interactions revisited: new benchmark and performance of composite localized coupled-cluster methods. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2022;24:25555–25570. doi: 10.1039/D2CP03938A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalasinski G., Szczesniak M. M.. Origins of Structure and Energetics of van der Waals Clusters from ab Initio Calculations. Chem. Rev. 1994;94:1723–1765. doi: 10.1021/cr00031a001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pal S., Prasad M. D., Mukherjee D.. On certain correspondences among various coupled-cluster theories for closed-shell systems. Pramana. 1982;18:261–270. doi: 10.1007/BF02847816. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hummel F., Gruneis A., Kresse G., Ziesche P.. Screened exchange corrections to the random phase approximation from many-body perturbation theory. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2019;15:3223–3236. doi: 10.1021/acs.jctc.8b01247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grüneis A., Marsman M., Harl J., Schimka L., Kresse G.. Making the random phase approximation to electronic correlation accurate. J. Chem. Phys. 2009;131:154115. doi: 10.1063/1.3250347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren X., Rinke P., Scuseria G. E., Scheffler M.. Renormalized second-order perturbation theory for the electron correlation energy: Concept, implementation, and benchmarks. Phys. Rev. B. 2013;88:035120. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.88.035120. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Heßelmann A.. Third-order corrections to random-phase approximation correlation energies. J. Chem. Phys. 2011;134:204107. doi: 10.1063/1.3590916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- https://github.com/modrzejewski.

- Parrish R. M., Zhao Y., Hohenstein E. G., Martínez T. J.. Rank reduced coupled cluster theory. I. Ground state energies and wavefunctions. J. Chem. Phys. 2019;150:164118. doi: 10.1063/1.5092505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J., Kurashige Y., Manby F. R., Chan G. K.. Tensor factorizations of local second-order Møller-Plesset theory. J. Chem. Phys. 2011;134:044123. doi: 10.1063/1.3528935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pipek J., Mezey P. G.. A fast intrinsic localization procedure applicable for ab initio and semiempirical linear combination of atomic orbital wave functions. J. Chem. Phys. 1989;90:4916. doi: 10.1063/1.456588. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Foster J. M., Boys S.. Canonical configurational interaction procedure. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1960;32:300. doi: 10.1103/RevModPhys.32.300. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Modrzejewski M., Yourdkhani S., Klimes J.. Random Phase Approximation Applied to Many-Body Noncovalent Systems. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2020;16:427–442. doi: 10.1021/acs.jctc.9b00979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kállay M., Nagy P. R., Mester D., Rolik Z., Samu G., Csontos J., Csóka J., Szabó P. B., Gyevi-Nagy L., Hégely B., Ladjánszki I., Szegedy L., Ladóczki B., Petrov K., Farkas M., Mezei P. D., Ganyecz. The MRCC program system: Accurate quantum chemistry from water to proteins. J. Chem. Phys. 2020;152:074107. doi: 10.1063/1.5142048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen A. H., Mortensen J. J., Blomqvist J., Castelli I. E., Christensen R., Dułak M., Friis J., Groves M. N., Hammer B., Hargus C., Hermes E. D., Jennings P. C., Jensen P. B., Kermode J., Kitchin J. R., Kolsbjerg E. L., Kubal J., Kaasbjerg K., Lysgaard S., Maronsson J. B., Maxson T., Olsen T., Pastewka L., Peterson A., Rostgaard C., Schiøtz J., Schütt O., Strange M., Thygesen K. S., Vegge T., Vilhelmsen L., Walter M., Zeng Z., Jacobsen K. W.. The atomic simulation environmenta Python library for working with atoms. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter. 2017;29:273002. doi: 10.1088/1361-648X/aa680e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borca C. H., Bakr B. W., Burns L. A., Sherrill C. D.. CrystaLattE: Automated computation of lattice energies of organic crystals exploiting the many-body expansion to achieve dual-level parallelism. J. Chem. Phys. 2019;151:144103. doi: 10.1063/1.5120520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parrish R. M., Hohenstein E. G., Martínez T. J., Sherrill C. D.. Tensor hypercontraction. II. Least-squares renormalization. J. Chem. Phys. 2012;137:224106. doi: 10.1063/1.4768233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews D. A.. Improved grid optimization and fitting in least squares tensor hypercontraction. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2020;16:1382–1385. doi: 10.1021/acs.jctc.9b01205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuchardt K. L., Didier B. T., Elsethagen T., Sun L., Gurumoorthi V., Chase J., Li J., Windus T. L.. Basis Set Exchange: A Community Database for Computational Sciences. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2007;47:1045–1052. doi: 10.1021/ci600510j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kresse G., Hafner J.. Ab initio molecular dynamics for liquid metals. Phys. Rev. B. 1993;47:558. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.47.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kresse G., Hafner J.. Ab initio molecular-dynamics simulation of the liquid-metal-amorphous-semiconductor transition in germanium. Phys. Rev. B. 1994;49:14251. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.49.14251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kresse G., Furthmüller J.. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B. 1996;54:11169. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.54.11169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blöchl P. E.. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B. 1994;50:17953. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.50.17953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kresse G., Joubert D.. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B. 1999;59:1758. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.59.1758. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rozzi C. A., Varsano D., Marini A., Gross E. K. U., Rubio A.. Exact Coulomb cutoff technique for supercell calculations. Phys. Rev. B. 2006;73:205119. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.73.205119. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hofierka J., Klimes J.. Binding energies of molecular solids from fragment and periodic approaches. Electron. Struct. 2021;3:034010. doi: 10.1088/2516-1075/ac25d6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dolgonos G. A., Hoja J., Boese A. D.. Revised values for the X23 benchmark set of molecular crystals. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2019;21:24333–24344. doi: 10.1039/C9CP04488D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borca C. H., Glick Z. L., Metcalf D. P., Burns L. A., Sherrill C. D.. Benchmark coupled-cluster lattice energy of crystalline benzene and assessment of multi-level approximations in the many-body expansion. J. Chem. Phys. 2023;158:234102. doi: 10.1063/5.0159410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Hamdani Y. S., Nagy P. R., Zen A., Barton D., Kállay M., Brandenburg J. G., Tkatchenko A.. Interactions between large molecules pose a puzzle for reference quantum mechanical methods. Nat. Commun. 2021;12:3927. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-24119-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishman V., Lesiuk M., Martin J. M. L., Boese A. D.. Another Angle on Benchmarking Noncovalent Interactions. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2025;21:2311–2324. doi: 10.1021/acs.jctc.4c01512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klimeš J.. Lattice energies of molecular solids from the random phase approximation with singles corrections. J. Chem. Phys. 2016;145:094506. doi: 10.1063/1.4962188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yourdkhani S., Klimes J.. Using Noncovalent Interactions to Test the Precision of Projector-Augmented Wave Data Sets. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2023;19:8871–8885. doi: 10.1021/acs.jctc.3c00930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.