Abstract

Background

Limited information is available regarding the usefulness of third-line chemotherapy for recurrent ovarian, fallopian tube, and primary peritoneal cancer treated with platinum-taxane regimens as first-line therapy.

Patients and methods

We retrospectively reviewed the medical records of women with ovarian, fallopian tube, and primary peritoneal cancer who were treated at the National Cancer Center Hospital between 1999 and 2005 to investigate the relations of clinicopathological factors to important clinical endpoints such as the response rate (RR), time to progression (TTP) and overall survival (OS) after third-line chemotherapy.

Results

A total of 172 patients received first-line platinum/taxane regimens during the study period, among whom 111 had disease progression after first-line chemotherapy. Eighty-one of these 111 patients received second-line chemotherapy, and 73 had disease progression. Fifty-four of the 73 patients with disease progression received third-line chemotherapy. The RR to third-line chemotherapy was 40.7% (95% CI, 27.6–53.8%). The median TTP was 4.4 months (range 0–19.5 months), and the median OS was 10.4 months (range 1.5–44.3 months). Performance status (PS) and primary drug-free interval (DFI) were independent predictive factors for the RR to third-line chemotherapy (P = 0.04 and P = 0.009). PS and primary DFI were also independent predictive factors for TTP and OS on multivariate analysis (P = 0.006, P = 0.005 and P = 0.01, P = 0.004, respectively).

Conclusions

PS and primary DFI are useful predictors of the response to third-line chemotherapy in women with recurrent ovarian, fallopian tube, and primary peritoneal cancer. In this setting, however, both of these variables are subject to several well-established potential biases and limitations; further prospective studies are thus needed.

Keywords: Third-line chemotherapy, Recurrent ovarian, Fallopian tube, Primary peritoneal cancer

Introduction

Ovarian cancer remains the leading cause of death from gynecological neoplasms in the Western world (Greenlee et al. 2001). Most cases are diagnosed when the disease is advanced, resulting in poor survival (Heintz et al. 2001; Engel et al. 2002; Jemal et al. 2003). Despite high rates of objective responses to surgery and primary chemotherapy, relapse rates remain high. Recurrent disease is treated either with the same regimen as that used for first-line chemotherapy (i.e., reinduction therapy) or with second- or third-line regimens. The aim of treatment after relapse is mainly palliative, designed to control disease symptoms, maintain patients’ quality of life, and prolong survival. New chemotherapeutic drugs have yielded objective response rates (RR) of 10–30% in recurrent ovarian cancer, depending on the anticancer activity of the drug(s) used, cross-resistance with previously administered drugs, and the response of the primary tumor to platinum compounds. In general, primary platinum sensitivity is defined as a documented response to the initial platinum-based therapy for at least 6 months after the end of treatment. RR of 30% to >50% have been obtained in patients with longer treatment-free intervals or with platinum-sensitive primary tumors (primary platinum sensitivity) as compared with only <20% in patients with shorter treatment-free intervals (platinum resistance of the primary tumor) or refractory ovarian cancer (no remission in response to first-line therapy) (Blackledge et al. 1989; Markman et al. 1991; Thigpen et al. 1994). Most previous studies have focused on the overall tumor response and time to treatment failure for specific drugs rather than attempting to evaluate the overall response to second-, third-, or fourth-line chemotherapy. The aim of this retrospective study was to investigate the relations of clinicopathological factors to important clinical endpoints such as the RR, time to progression (TTP), and overall survival (OS) in response to third-line chemotherapy in women with recurrent ovarian, fallopian tube, and primary peritoneal cancer who received platinum/taxane regimens as first-line therapy.

Patients and methods

Patients

We retrospectively reviewed the medical records of patients with ovarian, fallopian tube, and primary peritoneal cancer treated at the National Cancer Center Hospital between 1999 and 2005. All the patients had received platinum/taxane regimens as first-line therapy. Treatment decisions were usually made by the attending clinician. Patients in whom the tumor was considered possibly platinum-sensitive usually received a platinum agent, a taxane, or both. In general, combination chemotherapy was not administered as salvage treatment for recurrent disease, and most patients with recurrent disease received a single chemotherapeutic agent. Drug-free interval (DFI) was measured from the date of the last dose of chemotherapy until disease progression. Primary DFI was measured from the date of last dose of first-line chemotherapy until disease progression, and secondary DFI was measured from the date of the last dose of second-line chemotherapy until disease progression. Patients participated in clinical trials if they were eligible. The imaging criteria for treatment response were based on two-dimensional measurements of the lesions. Serum CA125 levels were not used as a primary measure of the response, but were referred to in the evaluation of response. Complete response was defined as no evidence of disease on physical examination or imaging studies, with normalization of the serum CA125 level. Partial response was defined as a >50% reduction in tumor size. Stable disease was defined as a 25–50% decrease or increase, or as no change in tumor size. Patients with an increase in the serum CA125 level were not evaluated to have had a partial response or stable disease. Progressive disease was defined as a >25% increase in tumor size. The Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) criteria were not used because most patients received treatment before this system was adopted by our hospital.

Statistical analysis

The main outcome measures for drug efficacy were RR, TTP, and OS. TTP was defined as the interval from the first day of third-line chemotherapy to the day of documented disease progression. For patients who were alive at the end of the study, the TTP data were right-censored to the time of the last evaluation or the time of the last contact at which the patient was progression-free. OS was defined as the interval from the first day of third-line chemotherapy to the day of death. For patients who were alive at the end of the study, the OS data were right-censored to the time of the last evaluation or contact. Data were analyzed by parametric and nonparametric statistics using SAS, version 9.1.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). Descriptive statistics were used for demographic data; such data are presented as mean with standard deviations or as medians with ranges. Survival was estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method, and differences between survival curves were evaluated with the log-rank test. A multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to determine predictive factors of the response to chemotherapy. A Cox regression analysis was performed to determine factors influencing TTP and OS.

Results

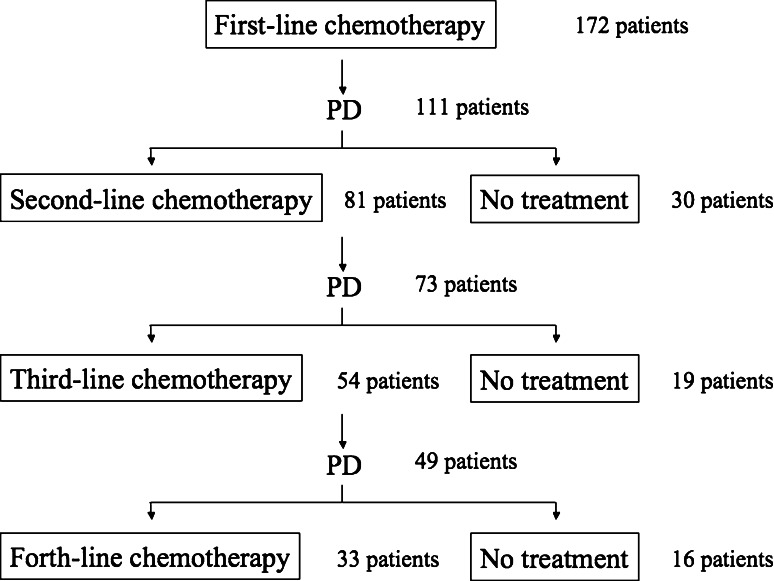

A total of 172 patients received first-line platinum/taxane regimens during the study period, of whom 111 had disease progression after first-line chemotherapy. Eighty-one of these 111 patients received second-line chemotherapy, among whom 73 had disease progression. Fifty-four of these 73 patients received third-line chemotherapy (Fig. 1). Mean age at the time of diagnosis of the primary cancer was 54 years (26–75 years), and mean age at the start of second- and third-line chemotherapy was 55 (28–76 years) and 55 (31–77 years) years, respectively. There were 46 cases (85.1%) of ovarian carcinoma, 7 (13.1%) of primary peritoneal carcinoma, and 1 (1.8%) of fallopian tube carcinoma. The patients’ characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Fig. 1.

Schema of treatment

Table 1.

Patient characteristics (n = 54)

| Age (year) | Median (range) |

| At primary diagnosis | 54 (26–76) |

| At second-line chemotherapy | 55 (28–77) |

| At third-line chemotherapy | 55 (31–78) |

| Performance status | |

| 0 | 6 |

| 1 | 22 |

| 2 | 24 |

| 3 | 2 |

| Stage | |

| I | 4 |

| II | 5 |

| III | 30 |

| IV | 15 |

| Organ | |

| Ovarian carcinoma | 46 |

| Primary peritoneal carcinoma | 7 |

| Fallopian tube carcinoma | 1 |

| Pathology | |

| Serous adenocarcinoma | 40 |

| Endometrioid adenocarcinoma | 2 |

| Mucinous adenocarcinoma | 1 |

| Clear cell carcinoma | 5 |

| Undifferentiated carcinoma | 6 |

| No. of target lesions | |

| 1 | 38 |

| 2 | 10 |

| 3 | 6 |

| Drug free-interval (month) | |

| Primary | 8.2 (0.9–39.3) |

| Secondary | 8.3 (0.1–21.5) |

| 3rd-line regimens | |

| Platinum/taxane-containing regimens | 36 |

| Other regimens | 18 |

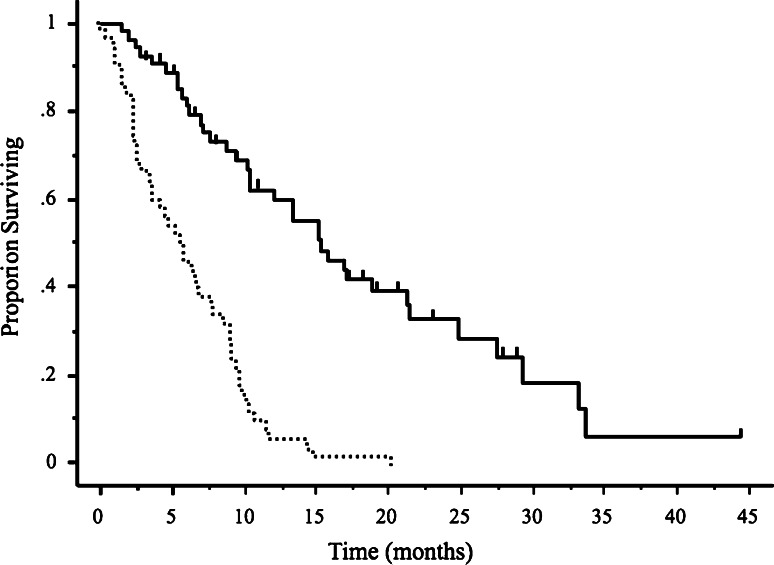

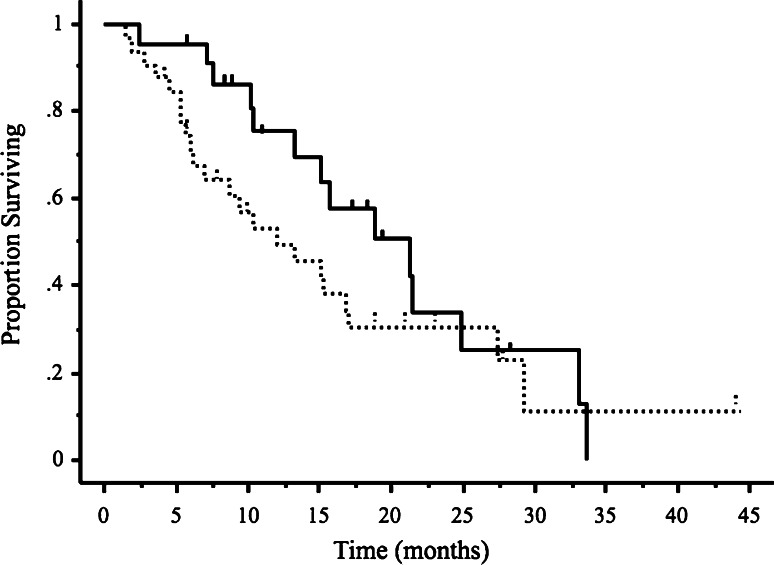

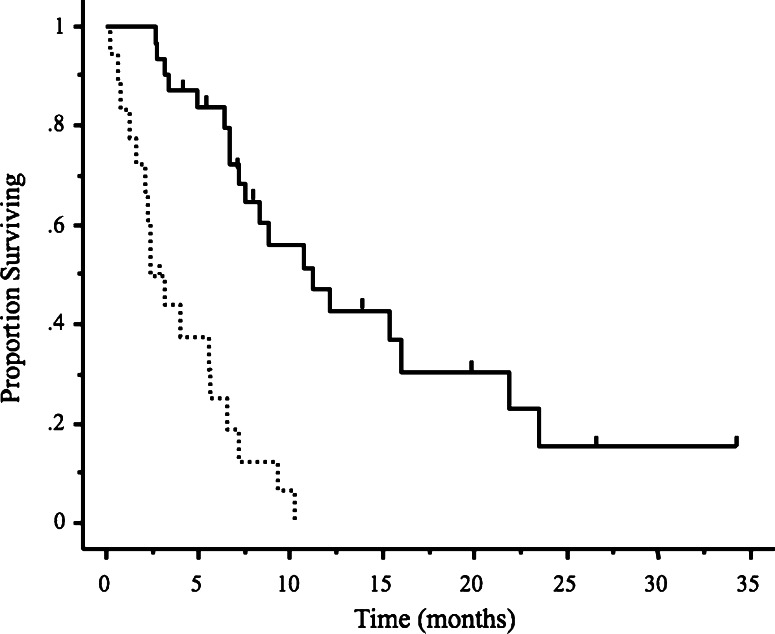

At the time of initial recurrence, 37 patients (69%) had primary platinum sensitivity, and 17 (31%) had primary platinum resistance. All patients treated with second-line drugs had either stable or progressive disease and received third-line treatment within 1–2 months after the last cycle of second-line treatment. The most commonly used regimen was weekly paclitaxel/carboplatin for second-line treatment and carboplatin for third-line treatment. The numbers of patients and chemotherapeutic drugs used in each setting are listed in Table 2. The median number of cycles of third-line treatment was 6 (range 1–18 cycles). The median TTP was 4.4 months (range 0–19.5 months), and the median OS was 10.4 months (range 1.5–44.3 months) (Fig. 2). The RR to third-line chemotherapy was 40.7% (95% CI; 27.6–53.8%). Five patients (9.2%) had complete responses and 17 (31.5%) had partial responses. Disease remained stable in 18 patients (33.3%) and progressed in 12 (22.2%). Two patients discontinued treatment because of hypersensitivity reactions to carboplatin. Overall, 49 patients had disease progression and 33 subsequently received fourth-line chemotherapy. The RR to fourth-line chemotherapy was 36.3% (95% CI, 19.9–52.7%); 2 patients had complete responses, 7 had partial responses, 9 had stable disease, and 12 had progressive disease. At the time of data analysis, 38 of the 54 patients (70.3%) had died. We studied the relations between the response to third-line drug therapy and clinical factors such as age, performance status (PS), histopathological type of cancer, number of target lesions, primary and secondary DFI, response to second-line chemotherapy, and the use of platinum/taxane regimens. The RR to third-line treatment was found to be significantly better in patients with a good PS (0 or 1) and a primary DFI of >6 months (P = 0.04 and P = 0.009, respectively, Table 3). Patients with a good PS and a primary DFI of >6 months also had a longer TTP and better OS (P = 0.006, P = 0.005 and P = 0.01, P = 0.004, respectively, Table 4). Median OS was slightly but not significantly better in the patients who responded to third-line chemotherapy (15.1 months; range 2.4–33.7 months) than in those who did not (9.4 months; range 1.5–44.3 months) (P = 0.054, Fig. 3). Median OS was significantly longer in the patients who received fourth-line chemotherapy (8.2 months; range 2.1–25.2 months) than in those who did not receive chemotherapy (2.4 months; range 0.2–16.2 months) (P < 0.0001, Fig. 4).

Table 2.

First-, second- and third- line chemotherapeutic regimens used

| First-line | Second-line | Third-line | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paclitaxel/carboplatin | 35 | Weekly paclitaxel/carboplatin | 28 | Carboplatin | 14 |

| Docetaxel/carboplatin | 12 | Docetaxel/carboplatin | 12 | Weekly paclitaxel/carboplatin | 10 |

| Paclitaxel/cisplatin | 7 | Irinotecan | 5 | Irinotecan | 8 |

| Topotecan | 2 | Irinotecan/etoposide | 4 | ||

| Carboplatin | 2 | Docetaxel | 4 | ||

| Liposomal doxorubicin | 1 | Liposomal doxorubicin | 4 | ||

| Paclitaxel/carboplatin | 1 | Docetaxel/carboplatin | 3 | ||

| Irinotecan/carboplatin | 1 | Cisplatin | 2 | ||

| Irinotecan/etoposide | 1 | Paclitaxel/carboplatin | 1 | ||

| Docetaxel | 1 | Paclitaxel/cisplatin | 1 | ||

| Irinotecan/mitomycin | 1 | ||||

| Paclitaxel | 1 | ||||

| Etoposide | 1 | ||||

Fig. 2.

Kaplan–Meier analysis of time to progression (solid line) and overall survival (dotted line) following third-line chemotherapy. Vertical bars indicate censored cases

Table 3.

Multivariate analysis of response rates to third-line chemotherapy

| Clinical factors | No. of patients | Response rate (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| <60 | 35 | 52.6% (30.1–75.0%) | 0.50 |

| ≥60 | 19 | 44.0% (23.7–56.2%) | |

| PS | |||

| 0.1 | 28 | 57.1% (38.8–75.4%) | 0.04 |

| 2.3 | 26 | 30.7% (13.0–48.5%) | |

| Pathology | |||

| Mucinous/clear cell | 6 | 33.3% (4.3–71.0%) | 0.22 |

| Non-mucinous/clear cell | 48 | 45.8% (31.7–59.9%) | |

| No. of target lesions | |||

| 1 | 40 | 45.0% (29.5–60.4%) | 0.37 |

| 2.3 | 14 | 42.8% (16.9–68.7%) | |

| Primary DFI | |||

| <6 months | 17 | 17.6% (0.4–35.7%) | 0.009 |

| ≥6 months | 37 | 51.3% (35.2–67.4%) | |

| Secondary DFI | |||

| <6 months | 33 | 42.4% (25.5–59.2%) | 0.70 |

| ≥6 months | 21 | 47.6% (26.2–68.9%) | |

| Response to second-line therapy | |||

| Responders | 35 | 45.7% (29.2–62.2%) | 0.09 |

| Non-responders | 19 | 31.5% (10.6–52.4%) | |

| PT regimens | |||

| PT regimens | 36 | 38.8% (22.9–54.8%) | 0.75 |

| Non-PT regimens | 18 | 44.4% (21.4–67.4%) | |

PT Platinum/taxane

Table 4.

Multivariate analysis of TTP and OS following third-line chemotherapy

| Clinical factors | TTP P value | OS P value |

|---|---|---|

| Age (<60 vs. ≥60) | 0.59 | 0.76 |

| PS (0.1 vs. 2.3) | 0.006 | 0.005 |

| Pathology (mucinous/clear cell vs. non-mucinous/clear cell) | 0.34 | 0.29 |

| No. of target lesions (1 vs. 2.3) | 0.85 | 0.79 |

| Primary DFI (<6 months vs. ≥6 months) | 0.01 | 0.004 |

| Secondary DFI (<6 months vs. ≥ 6 months) | 0.61 | 0.34 |

| Response to second-line therapy (responder vs. non-responder) | 0.43 | 0.17 |

| PT regimens (PT regimens vs. non-PT regimens) | 0.84 | 0.36 |

DFI Drug free-interval, PT Platinum/taxane

Fig. 3.

Kaplan–Meier analysis of overall survival (bottom) following third-line chemotherapy. The difference between third-line responders (solid line) and third-line non-responders (dotted line) was not statistically significant (P = 0.054). Vertical bars indicate censored cases

Fig. 4.

Kaplan–Meier analysis of overall survival following fourth-line chemotherapy. The chemotherapy group (solid line) had significantly better survival (P < 0.0001) than the non-chemotherapy group (dotted line). Vertical bars indicate censored cases

Discussion

In women with ovarian cancer, treatment goals after failure to respond to first-line therapy are (1) the control or prevention of disease-related symptoms, (2) the maintenance of a good quality of life, and (3) the prolongation of progression-free survival. The aims of salvage treatment have long been a matter of debate. The possibility of achieving an OS benefit in these patients is very limited. RRs are generally similar to or poorer than those with previous treatments are. Moreover, the increased risk of toxicity in patients with a history of previous treatment(s) and of negatively affecting performance status makes some physicians reluctant to continue drug treatment.

Patients who have good performance status without clinically significant comorbidity may wish to continue treatment (Doyle et al. 2001). Donovan et al. (2002) evaluated the treatment preferences of women with recurrent ovarian cancer and reported that most patients (86%) initially prefer subsequent therapy, with 25% never considering the withdrawal of chemotherapy, even when the expected median survival was <1 week. Physicians must therefore take into account patients’ wishes along with other clinical data when planning treatment.

Most studies of salvage therapy have focused on the response to a particular single- or combined-drug regimen. Without well-designed controlled studies, however, it is difficult to determine outcomes that would be obtained if a drug were used earlier or later in the course of salvage treatment.

In our study, the RR to third-line chemotherapy was 40.7% (95% CI; 27.6–53.8%). To date, only a few authors have distinguished between second- and third-line treatments when evaluating drug response and survival rates. In a study by Villa et al. (1999), 49 patients with recurrent ovarian cancer received third-line drugs after complete or partial responses to second-line chemotherapy. The overall RR was 48%, and median survival was 6 months. The 1-year survival rate differed significantly between patients who responded and those who did not respond to second-line treatment (82 vs. 39%, P < 0.05).

We obtained good RRs to third-line treatment in patients with a good PS and those with a primary DFI of >6 months. The response to third-line chemotherapy is influenced by the response to second-line chemotherapy. However, third-line chemotherapy has only a modest RR with a marginal prolongation of progression-free interval, but no obvious effect on survival in patients with ovarian cancer (Tangjitgamol et al. 2004).

In our study, there was no significant difference in the survival rate between patients responded to third-line chemotherapy and those who did not. In terms of cost-effectiveness, best supportive care is the only cost-effective strategy, followed perhaps by second-line monotherapy, given currently available chemotherapeutic options (Rocconi et al. 2006).

Patients with recurrent disease are often retreated with the same primary drug(s), most often platinum agents, but might also receive other drugs (Markman et al. 1991; Thigpen et al. 1993; Bookman 2003; Fung et al. 2002). One of the most important considerations in selecting second-line therapy is platinum sensitivity status, as defined by the response of the primary disease to a platinum drug and the progression-free interval after the completion of treatment (Blackledge et al. 1989; Thigpen et al. 1993; Thigpen et al. 1994). Some researchers have argued that there is no definite treatment-free interval, which can reliably distinguish platinum sensitivity from platinum resistance (Markman 1998; Markman et al. 1998). Nonetheless, it is generally accepted that the longer the treatment-free interval, the better is the expected response to retreatment (Markman et al. 1991; Thigpen et al. 1994). One study reported that women with recurrent ovarian cancer who had a treatment-free interval of between 5 and 12 months showed a RR of only 27% to second-line platinum-based therapy, as compared with 59% in those with a treatment-free interval of longer than 24 months (Markman et al. 1991). However, the duration of secondary response to platinum therapy is less well documented; in particular, the relation between the duration of secondary response and that of the initial response is poorly understood.

Our results showed that PS and primary DFI were useful predictors of the response to third-line chemotherapy. Eisenhauer et al. (1997) conducted a multivariate analysis to determine predictors of clinical response to subsequent chemotherapy in 704 patients with platinum-pretreated ovarian cancer. Their initial univariate analysis revealed that response was significantly associated with many factors, including the drug used, time since diagnosis, tumor size, histology, and the presence or absence of liver metastasis. In contrast, their multivariate analysis showed that only serous histologic type, number of disease sites ≤2, and maximum size of the largest lesion <5 cm were associated with a favorable response. They concluded that drug activity might not be the only determinant of response, and that tumor characteristics are also important factors.

In our study, two patients had hypersensitivity reactions to carboplatin. Patients who receive multiple courses of carboplatin have increased rates of hypersensitivity reactions (Zanotti et al. 2001). The incidence of such reactions is 27% in patients receiving 7 or more cycles of carboplatin, with more moderate to severe symptoms developing in more than 50% of these patients (Markman et al. 1999).

The time to treatment failure (4.4 months) and the OS (10.4 months) in our study were consistent with those reported by other studies assessing individual drugs (Villa et al. 1999; Heintz et al. 2001; Tangjitgamol et al. 2004; Rocconi et al. 2006). The survival of patients given fourth-line and subsequent treatment was significantly longer than that of patients who received no further therapy after third-line treatment (8.3 months vs. 2.4 months, respectively; P < 0.0001). Administration of fourth-line chemotherapy to patients who might tolerate such treatment may also improve OS; however, the analysis of OS in this setting has its limitations and is prone to potential bias. One study reported that giving additional lines of chemotherapy may not improve OS and that the inclusion of paclitaxel in treatment regimens may have a significant effect on survival (Findley et al. 2005).

In conclusion, our study suggested that PS and primary DFI may be useful predictors of the response to third-line chemotherapy in women with recurrent ovarian, fallopian tube, and primary peritoneal cancer. Our findings will hopefully help physicians make treatment recommendations and inform patients about expected benefits and risks, outcomes, and survival rates in this setting. Finally, the decision whether to use third-line chemotherapy should be based on a comprehensive assessment of patients’ wishes, drug efficacy and toxicity, and treatment expertise of the clinician.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by The Supporting Fund of Obstetrics and Gynecology Kurume University.

References

- Blackledge G, Lawton F, Redman C, Kelly K (1989) Response of patients in phase II studies of chemotherapy in ovarian cancer: implications for patient treatment and the design of phase II trials. Br J Cancer 59:650–653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bookman MA (2003) Developmental chemotherapy and management of recurrent ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol 21:149s–167s [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan KA, Greene PG, Shuster JL, Partridge EE, Tucker DC (2002) Treatment preferences in recurrent ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol 86:200–211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle C, Crump M, Pintilie M, Oza AM (2001) Does palliative chemotherapy palliate? Evaluation of expectations, outcomes, and costs in women receiving chemotherapy for advanced ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol 19:1266–1274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhauer EA, Vermorken JB, van Glabbeke M (1997) Predictors of response to subsequent chemotherapy in platinum pretreated ovarian cancer: a multivariate analysis of 704 patients. Ann Oncol 8:963–968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel J, Eckel R, Schubert-Fritschle G, Kerr J, Kuhn W, Diebold J, Kimmig R, Rehbock J, Holzel D (2002) Moderate progress for ovarian cancer in the last 20 years: prolongation of survival, but no improvement in the cure rate. Eur J Cancer 38:2435–2445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Findley MK, Lee H, Seiden MV, Shah MA, Fuller AF, Goodman A, Penson RT (2005) Do more lines of chemotherapy make you live longer? Treatment for ovarian cancer comparing cohorts of patients 1989-90 with 1995-6 in multivariate analysis of survival. J Clin Oncol 23(Suppl):16S [Google Scholar]

- Fung MF, Johnston ME, Eisenhauer EA, Elit L, Hirte HW, Rosen B (2002) Chemotherapy for recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer previously treated with platinum—a systematic review of the evidence from randomized trials. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol 23:104–110 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenlee RT, Hill-Harmon MB, Murray T, Thun M (2001) Cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin 51:15–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heintz AP, Odicino F, Maisonneuve P, Beller U, Benedet JL, Creasman WT, Ngan HY, Sideri M, Pecorelli S (2001) Carcinoma of the ovary. J Epidemiol Biostat 6:107–138 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jemal A, Murray T, Samuels A, Ghafoor A, Ward E, Thun MJ (2003) Cancer statistics 2003. CA Cancer J Clin 53:5–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markman M (1998) ‘‘Recurrence within 6 months of platinum- therapy’’: an adequate definition of ‘‘platinum-refractory’’ ovarian cancer? Gynecol Oncol 69:91–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markman M, Rothman R, Hakes T, Reichman B, Hoskins W, Rubin S, Jones W, Almadrones L, Lewis JL Jr (1991) Second-line platinum therapy in patients with ovarian cancer previously treated with cisplatin. J Clin Oncol 9:389–393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markman M, Kennedy A, Webster K, Kulp B, Peterson G, Belinson J (1998) Evidence that a ‘‘treatment-free interval of less than 6 months’’ does not equate with clinically defined platinum resistance in ovarian cancer or primary peritoneal carcinoma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 124:326–328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markman M, Kennedy A, Webster K, Elson P, Peterson G, Kulp B, Belinson J (1999) Clinical features of hypersensitivity reactions to carboplatin. J Clin Oncol 17:1141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocconi RP, Case AS, Staughn JM Jr, Estes JM, Partridge EE (2006) Role of chemotherapy for patients with recurrent platinum-resistant advanced epithelial ovarian cancer: a cost-effective analysis. Cancer 107:536–543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tangjitgamol S, See HT, Manusirvithaya S, Levenback CF, Gershenson DM, Kavanagh JJ (2004) Third-line chemotherapy in platinum-and paclitaxel-resistant ovarian, fallopian tube, and primary peritoneal carcinoma patients. Int J Gynecol Cancer 12:804–814 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thigpen JT, Vance RB, Khansur T (1993) Second-line chemotherapy for recurrent carcinoma of the ovary. Cancer 71:1559–1564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thigpen JT, Blessing JA, Ball H, Hummel SJ, Barrett RJ (1994) Phase II trial of paclitaxel in patients with progressive ovarian carcinoma after platinum-based chemotherapy: a Gynecologic Oncology Group Study. J Clin Oncol 12:1748–1753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villa A, Parazzini F, Scarfone G, Guarnerio P, Bolis G (1999) Survival and determinants of response to third-line chemotherapy in sensitive recurrent ovarian cancer patients. Br J Cancer 79:373–374 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanotti KM, Rybicki LA, Kennedy AW, Belinson JL, Webster KD, Kulp B, Peterson G, Markman M (2001) Carboplatin skin testing: a skin-testing protocol for predicting hypersensitivity to carboplatin chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 19:3126–3129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]