Abstract

Objective

In the literature the frequency of splenic metastasis is documented very inconsistently. Only metastases of ovarial cancer are recommended for a surgical therapy. We examined the frequency of splenic metastasis in our hospital.

Method

The data of the Tumorboard Schwerin has been analyzed for splenic metastases. Based on hospital documents and contact via telephone the clinical course of the patients was also examined.

Results

A total of 6,137 of 29,364 patients with malignant tumors developed metastases (20.9%). We found 59 of these patients with splenic metastases (0.96%; 0.002% of all patients with malignant tumors). Men were more frequently concerned then women. The median age of the patients was 62 (26–88) years. There are only a few primary tumors metastasized in more than 1% into the spleen. A total of 47% of these metastases were synchronous, 53% metachronous. Only three patients had isolated splenic metastasis. Two further patients also had lymph node metastasis in the splenic hilus. Two other patients developed liver metastases after splenectomy. We performed four splenectomies because of splenic metastasis. The survival of splenic metastasis was median 3 (0–61) months.

Discussion

The published studies of the frequency of the splenic metastasis are autopsy studies, which are not usable for epidemiological statements because of selection bias. We show that splenic metastases arise in less than 1% of all metastases. A splenectomy in case of splenic metastases makes sense, if the metastases are isolated. It is also meaningful as a debulking procedure that would be followed by a chemotherapy, e.g. in case of an ovarial carcinoma. As a result the survival is increased for patients undergoing splenectomy (median survival 19.5 vs. 3 months).

Keywords: Malignoma, Metastasis, Spleen, Epidemiology, Survival, Therapy, Surgery

Introduction

In the literature the frequency of splenic metastases is documented inconsistently. The amount reaches from 0 to 34% (Harman and Dacorso 1948; Hirst and Bullock 1952; Warren and Davis 1934; Berge 1974). This data in the literature mainly originates from autopsy studies between 1920 and 1965.

During this time the focus was more on metastases of the spleen, in order to find a reason for the alleged lower frequency of metastasis in there. There were different hypotheses, which described the rarity of the splenic metastases to metastases of other organs. The preferred thoughts were the differences between the lymph system and the vessels of the spleen and the rest of the body. Next hypothesis was an immune authority of the spleen. Watson et al. (1947) even spoke about a resistance against metastases. Shaw Dunn (1955) claimed that that there are no fewer metastases in the spleen. The reason of minor number of metastases could be that the spleen was examined only selectively during the autopsy. Coman et al. said that the distribution of the metastases is less dependent from a different local immune authority. The frequency is based mainly on the flow conditions in the blood vessel system (Coman et al. 1951).

In the following autopsy studies it became clear that the non-gastrointestinal-originating tumors metastasize just as often into the spleen, than in other organs. If there is a generalized tumor growth, then the spleen is one of the three most frequent metastasizing places (Harman and Dacorso 1948). Resistances of the spleen against metastases has not been detected (Hirst and Bullock 1952).

Autopsy studies have the advantage of precise accuracy in the definition of the diagnosis. But the clinical course can often not be clarified and thus the meaning of the findings remains in the dark. So the autopsy study is not comparable with a clinical study at all.

There had not been many reports about splenectomies in cause of metastasis before 1980. Mainly there had been case reports (Brunschwieg and Morton 1946; McClure and Park 1975; Teears et al. 1976).

Altogether the clinical meaning and the frequency of metastasis in the spleen is not clarified. The frequency and the clinical course of splenic metastasis are shown by us. We used the data of the cancer-registry Schwerin (Germany, Mecklenburg).

Method

The data of the Tumorboard Schwerin and the cancer-registry of the western part of Mecklenburg–Vorpommern were used for the determination of the frequency and the clinical course. For this, the data bank has been searched for metastases and entity of carcinoma, melanoma and sarcoma, to identify the individual cases. We found more than a half of the cases with fully documented clinical course in the data bank. In the other cases the missing data were added through telephone contact with patient or family doctor or a comparison with certain clinic data. The cancer-registry Mecklenburg–Vorpommern receives the malignoma-cases from the reports of the local doctors, the clinic-doctors of the treating departments and the federal pathologists. The cases are checked in the regional resident’s registration office so that they can be proven. The data of the cancer-registry Mecklenburg are 98% complete.

Statistical analysis was done with WINSTAT and EXCEL. We used the Kaplan–Maier Function and a Chi-Quadrat test for the verification of significance.

Results

A total of 29,364 patients had been seized with malignant tumors til 31 December 2006.

A total of 6,137 of these patients developed metastases (20.9%). Fifty-nine patients had metastases in the spleen (0.96%). These 59 patients consist of 16 women and 43 men. In the beginning of the illness the median age of the patients was 62 (26–88) years. Table 1 shows the frequency of metastases in the different entities of malignoma.

Table 1.

Frequency of metastases and splenic metastases and localization of primary (6,137 patients with metastases)

| Primary tumor localization | n | Metastases | Splenic metastases | Synchronous (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |||

| Carcinoma of the parotid gland | 48 | 15 | 31 | 1 | 2.1 | 0 |

| Anal carcinoma | 60 | 6 | 10 | 1 | 1.7 | 100 |

| Pancreatic carcinoma | 429 | 238 | 55 | 6 | 1.4 | 50 |

| Esophageal carcinoma | 287 | 93 | 32 | 2 | 0.7 | 50 |

| Ovarial carcinoma | 431 | 69 | 16 | 3 | 0.7 | 33 |

| Bronchial carcinoma | 3,131 | 1,783 | 57 | 18 | 0.6 | 72 |

| Melanoma | 785 | 128 | 16 | 5 | 0.6 | 20 |

| Carcinoma of unknown primary | 468 | 127 | 27 | 3 | 0.6 | 33 |

| Sarcoma | 239 | 50 | 21 | 1 | 0.4 | 10 |

| Gastral carcinoma | 1,415 | 391 | 28 | 4 | 0.3 | 50 |

| Pharyngeal carcinoma | 291 | 57 | 20 | 1 | 0.3 | 0 |

| Endometrial carcinoma | 789 | 75 | 10 | 2 | 0.2 | 0 |

| Colorectal carcinoma | 3,111 | 957 | 31 | 7 | 0.2 | 57 |

| Renal carcinoma | 1,155 | 332 | 29 | 1 | 0.1 | 0 |

| Bladder carcinoma | 1,328 | 104 | 8 | 1 | 0.1 | 0 |

| Prostate carcinoma | 2,667 | 275 | 10 | 1 | 0.0 | 0 |

| Mammarial carcinoma | 5,069 | 909 | 18 | 2 | 0.0 | 0 |

Only a few entities of carcinoma have more then 1% of metastases in the spleen. There were median 4 (1–7) metastases per patient. A total of 47% of the metastases were discovered synchronously to the primary tumor. The other 53% of the metastases turned up metachrone (more than 2 months after the primary tumor diagnosis).

Only three patients had isolated metastases in the spleen. The isolated metastases had been found synchronously at patients with primary bronchial carcinoma, esophageal carcinoma and pancreatic carcinoma. Because the metastases were seen as a systematic illness of these carcinomas, there was no surgery for primary or secondary tumor done. Instead a chemotherapy or symptomatic therapy was performed. Two further patients had lymph-node metastases in the hilum of the spleen additional to the splenic metastases.

Four splenectomies had been performed because of metastases in the spleen (Table 2). Two patients had new metastases especially in the liver even after their spleen has been removed. Patients that had their spleen removed lived longer (19.5 vs. 3 months) then the patients that did not undergo surgical therapy (Fig. 1).

Table 2.

Splenectomies in case of splenic metastases

| Primary tumor | Metastasizing time | Other metastases | Cause of splenectomy | Survival in months |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CUP | Synchronous | Lung, adrenal gland, prostate, bone | Diagnosis | 4 |

| Gastral carcinoma | Synchronous | Lymph nodes in the splenic hilum | Solitary metastases, gastrectomy | 10 |

| Colon carcinoma | Metachronous | Lymph nodes in the splenic hilum | Obstruction | 29 |

| Ovarial carcinoma | Metachronous | Liver, peritoneum | Debulking | 30 |

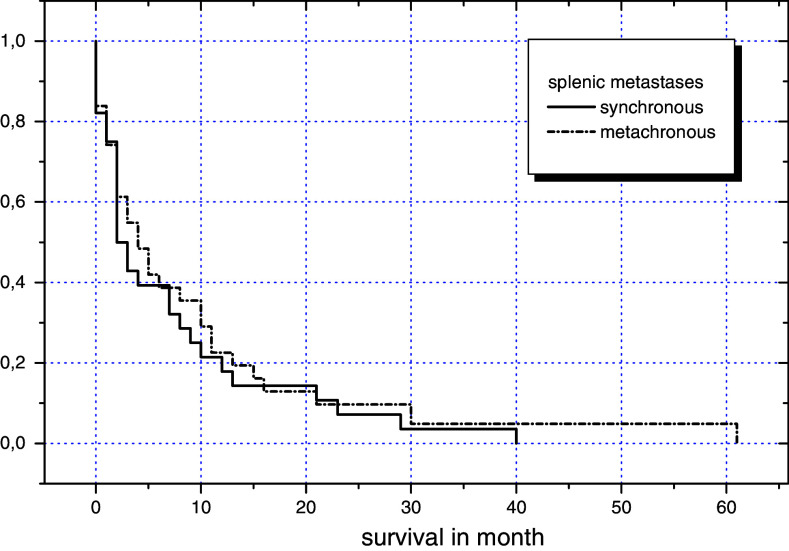

Fig 1.

Survival of splenic metastasis in dependency of therapy (P = 0.18)

From the diagnosis of a malignoma until the diagnosis of a metastasis in the spleen median 5 (0–149) months passed. It took median 30 (4–149) months with the patients who had metachrone metastases in the spleen. The patients with metastases in the spleen had been survived the occurrence of the primary in median 12 (0–187) months (Fig. 2). Patients have survived the occurrence of splenic metastasis 3 (0–61) months in median. The length of the overall survival depends from the time of the detection of the metastasis (Fig. 3).

Fig 2.

Survival of splenic metastasis (P = 0.55)

Fig 3.

Survival of primary tumor in dependency of occurence of splenic metastases (P = 0.000001)

Discussion

So far the appearance of metastases of a malignant tumor in the spleen has not been seized quantitative. The only published and usable studies about the frequency of metastases in the spleen are mainly autopsy studies (Harman and Dacorso 1948; Hirst and Bullock 1952; Warren and Davis 1934; Berge 1974). These studies are not usable for epidemiological statements because of the selection (on malignant tumors of deceased people). The strong differencing frequencies (0–32% spleen-metastases by patients with metastasis) in the studies illustrate the insufficient statement strength. During the years, when the larger studies developed, celiac processes were only discovered with large space demands or severe symptoms and therefore could malignomas be more frequently expanded metastasized, before the malignoma was discovered. This explains the often-found metastasis of the spleen in the autopsy studies that concentrated on people who have deceased because of a malignoma.

Metastases in the spleen were found on living patients especially when there was an intraabdominal bleeding because of “spontaneous spleen-rupture”. This results in a small frequency of clinical studies or cross-sectional autopsy studies.

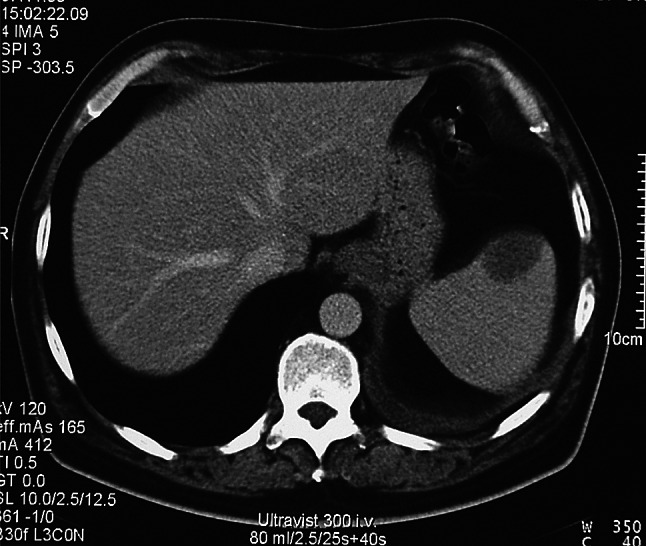

Today metastases in the spleen are mainly found in context of staging or restaging through imaging. Solitary (Fig. 4) and multiple metastases (Fig. 5) can be diagnosed in the computer tomography or magnetic resonance tomography.

Fig 4.

Solitary splenic metastasis of a bronchial carcinoma (computer tomography with contrast agent—venous phase)

Fig 5.

Multiple splenic and hepatic metastases of a bronchial carcinoma (computer tomography with contrast agent—arterial phase)

With the help of modern diagnostic capabilities primary-tumors are located earlier so that metastases in the spleen and other metastases are left out. Also metastases in the spleen can be detected that usually would not have been detected at all. The cancer-registry Schwerin that represents the western part of the cancer-registry of hole state Mecklenburg–Vorpommern and that documents momently over 30,000 patients with malignant diseases, shows that metastases in the spleen are less than 1% of all metastases and less than 0.2% of all carcinomas, melanomas and sarcomas.

A total of 98% of the patients with malignomas in Mecklenburg–Vorpommern are registered by the cancer-registry so that the data shows the right incidence of malignomas. But the statement about the frequency of metastases has to stay a current statement because the diagnostic and therapeutic possibilities are in flow and the frequency changes in time. There already had been changes since the published cross-sectional autopsy study in 1974 of the inhabitants of Malmö (Berge 1974). The frequency of all metastases has gone down from 62 (Berge 1974) to 21% in our data. Also the frequency of metastases in the spleen has gone down from 7 to 1%. Assuming that autopsy studies discover more metastases than the clinical course, there is still a reduced frequency of metastases. Important are not the statements about the frequency of metastases but the statement about the possible influence of the illness.

A splenectomy because of metastases of a carcinoma is meaningful if there are isolated metastases or when there is a carcinoma at which the tumor reduction has to be performed before chemotherapy (Lee et al. 2000; Nicklin et al. 1995). In the largest published series of splenectomies because of metastases 74% of the primary tumors were ovarial carcinomas (Lee et al. 2000). Also in our data is a female patient with an ovarial carcinoma and splenic and peritoneal metastases that underwent a debulking therapy with a splenectomy and a following chemotherapy. This patient has survived the appearance of splenic metastases for 30 months. Figure 2 shows the survival-chance in dependency of a splenectomy. It shows the survival-advantage for patients that underwent a splenectomy (median survival 19.5 vs. 3 months after the appearance of metastases, not significant). The number of patients who underwent splenectomy is very little, this limits the statement-strength. In addition, does the selection of the patient play a big role? It remains, that a resection of metastases makes sense in some cases and compared to the average it results in a longer survival rate. That the time of the appearance of metastases has an effect on the survival after diagnose of the tumor is obvious (Fig. 3).

It remains that malignoma metastases in the spleen are rare and that only in a small percentage an operational procedure appears possible. If, however, total tumor-freedom can be achieved, a splenectomy should be done in particular with metachrone metastases. Also a debulking with a following chemotherapy of a metastasized ovarial carcinoma can make a splenectomy necessary and meaningful.

References

- Berge T (1974) Splenic metastasis. Frequencies and patterns. Acta Path Microbiol Scand 82:499–506 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunschwieg A, Morton DR (1946) Resection of abdominal carcinomas involving the liver and spleen secondarily. Ann Surg 124:746–754 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coman DR, DeLong RP, McCutcheon M (1951) Studies on the mechanism of metastasis; the distribution of tumors in various organs in relation to the distribution of arteria emboli. Cancer Res 11:648–651 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harman JW, Dacorso P (1948) Spread of carcinoma to the spleen. Arch Pathol 45:179–186 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirst AE, Bullock WK (1952) Metastatic carcinoma of the spleen. Am J Med Sci 223:414–417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SS, Morgenstern L, Phillips EH, Hiatt JR, Margulies DR (2000) Splenectomy for splenic metastases: a changing clinical spectrum. Am Surg 66:837–840 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClure JN, Park YH (1975) Solitary metastatic carcinoma of the spleen. South Med J 68:101–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicklin JL, Copeland LJ, O’Toole RV, Lewandowski GS, Vaccarello L, Havenar LP (1995) Splenectomy as part of cytoreductive surgery for ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol 58:244–247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw Dunn RI (1955) Cancer metastasis in the spleen. Glasg Med J 36:43–49 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teears RJ, Batsakis JG, Weatherbee L (1976) Unusual metastasis from an anaplastic carcinoma in the parotid gland. J Oral Surg 34:551–552 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren S, Davis AH (1934) Studies on tumor metastasis: the metastases of carcinoma to the spleen. Am J Cancer 21:517–533 [Google Scholar]

- Watson GF, Diller IC, Ludwick NW (1947) Spleen extract and tumor growth. Science 106:348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]