Abstract

Purpose

The primary goal of the study was to determine if resilience influences fatigue in a consecutive sample of cancer patients treated with radiotherapy (RT) at the beginning and at the end of the treatment.

Methods

Out of an initial sample of 250 patients, 239 could be assessed at the beginning of their RT. Two hundred and eight patients were reassessed at the end of RT 4–8 weeks later. Measures comprised the Resilience Scale (RS), the Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory (MFI), and the SF-12 as a measure of health related Quality of Life (QoL). Medical data were continuously registered.

Results

As hypothesized, the sample revealed higher scores in the MFI and lower scores in the SF-12 than normative samples. Resilience scores were higher than in the norm population. Fatigue increased during RT. Using multiple regression analyses, fatigue scores at the beginning of treatment were shown to be higher in inpatients and patients undergoing palliative treatment. Initial fatigue was best predicted by the patients’ initial resilience scores. Changes of fatigue scores during RT depended on initial scores, decrease in Hb and the patients’ experience with RT. Resilience could not be determined as a predictor of changes in fatigue during RT.

Conclusions

The study confirmed that fatigue is an important problem among RT patients. Resilience turned out to powerfully predict the patients’ fatigue at least early in RT. This result is in line with other studies, showing resilience to be an important psychological predictor of QoL and coping in cancer patients. On the other hand, resilience seems to have little influence on treatment related fatigue during RT.

Keywords: Fatigue, Resilience, Radiation therapy, Quality of life

Introduction

Among the psychological and physical symptoms, fatigue is a common side effect in cancer patients with and without radiation therapy (RT; NIH State-of-the-Science Panel 2003). Although estimations of the prevalence of cancer-related fatigue are inconsistent, several reviews conclude that up to 80% of the patients undergoing RT suffer from this side effect (e.g., Hickok et al. 1996; AHRQ 2002; Jereczek-Fossa et al. 2002).

The etiology of this common symptom is still poorly understood. It is assumed that specific tumor related factors (e.g., site of the tumor, circulatory and metabolic disorders) explain the symptom (Ream and Richardson 1997; Stasi et al. 2003; Glaus et al. 1996) as well as secondary sequelae of the cancer (immobility, sleep disturbances, pain). Additionally, several authors have discussed the importance of psychological mechanisms underlying fatigue including depression, personality factors, and coping responses (Visser and Smets 1998; Weis and Bartsch 2000).

A variety of systemic side effects, including fatigue, have been described for patients undergoing RT. Cancer related fatigue has been reported to increase during RT (Jereczek-Fossa et al. 2002; Stone et al. 1998; Smets et al. 1998a, b). It has been argued that specific RT-related factors might influence the prevalence of the symptom, among these localization and dosage of radiation and the extent of other adverse effects (Stone et al. 1998).

Since fatigue dramatically affects the quality of life (QoL) and the patients’ general well being (Weis and Bartsch 2000), it is important to develop treatment methods to manage this adverse effect. Recent reviews reveal that the results of studies evaluating such methods are inconsistent. The AHRQ (2002) reports that only a limited number of controlled clinical trials for the treatment of cancer-related fatigue have been published. Evidence for the use of epoetin alfa in patients with anemia due to chemotherapy is the only intervention that has been strongly supported. In addition, there is some evidence for the positive effects of physical exercise programs, and, less clearly, psychosocial interventions. Newell et al. (2002) concluded: “The overall results ... suggest that no intervention strategy could be recommended for reducing patients’ fatigue.” “Tentative recommendations” could only be made for “... interventions involving group therapy and cognitive behavioural therapy” (p. 577).

Two major reasons for the inconsistency of research results related to the psychological management of fatigue might be considered, (a) the quality of the studies (small sample sizes, diminished statistical power), (b) the fact that mechanisms underlying fatigue as a specific target symptom of psychological interventions are still unexplained.

In order to contribute to the clarification of psychological factors influencing the occurrence of fatigue in patients undergoing RT, this study aimed to investigate the relationship of resilience, a personality related construct, to patients’ fatigue early and at the end of their radio-oncological treatment in a larger sample.

Resilience is a psychological construct that has gained increasing attention during the past years. Originally, resilience was defined within developmental psychology as a variety of psychological resources providing power of resistance when a person faces critical life situations or demands (e.g., Rutter 1987; Staudinger and Freund 1998; Staudinger et al. 1996a, b). The construct then has been used as a variable to predict coping with illness and life threats and has shown to be influential in determining active coping and adaptation (Bender and Lösel 1997; Farber et al. 2000). The concept has been related to other “salutogenetic” factors such as the sense of coherence (Surtess et al. 2004). Within psychooncology, some authors have studied resilience related variables to describe cancer survivors (Gotay et al. 2003; Parry 2003; Wenzel et al. 2002; Stewart et al. 2001) and mostly found that these patients were characterized by higher resilience levels than controls. Other studies dealing with cancer patients have shown that resilience is positively related to QoL (Bull et al. 1999; Antoni and Goodkin 1988) and that it differs from optimism (Bowen et al. 2003). Since resilience was primarily studied in developmental research related to children and adolescents, some authors have tried to integrate the concept into programs for the management of cancer in children and adolescent populations (Woodgate 1999a, b; Haase et al. 1999; Nelson et al. 2004).

Based upon the assumption, that resilience might be an important factor determining the psychological and physical QoL in radio-oncologically treated cancer patients that could influence fatigue in these patients, the present study tried to measure this construct and, focusing on the patients’ fatigue, to determine the variance explained by resilience early in and at the end of treatment in comparison to other, illness and treatment related predictors.

Patients and methods

Patient sample

The initial sample of this study consisted of 250 consecutive patients who were contacted during their initial assessment within the radiation oncology department of the University Hospital Jena. Since it was intended to study a sample representative for a radio-oncology unit, only patients with tumors of the brain were excluded. Of the 250 patients, 239 were willing to participate in the initial assessment, 208 patients could be repeatedly assessed at the end of their treatment. The remaining 31 patients dropped out due to organizational reasons (e.g., not reachable at the end of RT, problems with time). These 31 patients did not differ significantly from the remaining sample with respect to medical, treatment related and pre-treatment psychological variables. The initial sample comprised 77 males and 162 females with a median age of 61.5 years (Range = 25–85 years, SD 12.9). The median age was 62.8 among the male, and 59.9 among the female patients.

About 59% of the patients already were retired, 16% were living alone. About 30% of the sample were treated as inpatients, 81% underwent their first RT. In 83%, RT was planned as curative treatment (vs. 17% palliative). Fourty three of the 239 patients (18%) received simultaneously given radiation/chemotherapy. Most of the patients underwent RT following either surgery and/or previous chemotherapy (92%).

The vast majority of the sample consisted of women with breast cancer (45%), followed by patients with other gynecological tumors (11%), prostate cancer (10%), and gastrointestinal and lung cancers (10% vs. 9%).

Table 1 summarizes relevant medical/radiological characteristics of the sample. Table 2 reflects classifications of RT acute toxicity early/late during RT using the Common Toxicity Criteria (CTC, Seegenschmidt et al. 1996).

Table 1.

Summary of medical/radiological parameters

| Stage of cancer | |

|---|---|

| Local | 43% (n = 62) |

| Regional | 26% (n = 37) |

| Distant | 31% (n = 45) |

| Karnofsky index (B a) | |

| 90–100% | 72% (n = 168) |

| 70–80% | 23% (n = 54) |

| <60% | 5% (n = 11) |

| Total radiation dose | |

| <42 Gy | 19% (n = 44) |

| 42–59 Gy | 52% (n = 124) |

| >60 Gy | 29% (n = 68) |

| Volumina irradiated with more than 50% of the total dose (excluding breast cancer) | |

| <500 ml | 0% (n = 0) |

| 501–2,000 ml | 0% (n = 0) |

| >2,000 ml | 100% (n = 122) |

| Target volumina (breast cancer) | |

| <1,500 ml | 22% (n = 22) |

| >1,500 ml | 78% (n = 77) |

| Fractionation | |

| ≤2 Gy | 95% (n = 225) |

| >2 Gy | 5% (n = 11) |

| Radiated region | |

| Breast | 43% (n = 102) |

| Pelvis | 22% (n = 53) |

| Thorax | 12% (n = 29) |

| Head/neck | 11% (n = 25) |

| Others | 12% (n = 27) |

| Hb [norm 7.6–9.5 mmol/l (female), 8.7–10.9 mmol/l (male)] | |

| <Norm | 43% (n = 83) |

| In norm | 56% (n = 107) |

| >Norm | 1% (n = 1) |

aB is beginning of RT

Table 2.

CTC status early/late in treatment (%)

| CTC (grades 3 or 4) | Early | Latea |

|---|---|---|

| CTC skin side effects | 0 | 15.7 |

| CTC mucous membrane side effects | 1 | 6.3 |

| CTC blood parameter | 10.7 | 13.6 |

| CTC general status | 3.4 | 6.3 |

| CTC general symptoms (appetite and weight loss) | 2.2 | 6.8 |

| CTC other side effects | 3.4 | 3.7 |

| CTC supportive care (intensive/invasive) | 2.2 | 5.8 |

| CTC compliance (inadequate) | 8.6 | 10.5 |

a4–8 weeks after the beginning of RT

Assessments

In addition to a physical examination, all patients were assessed psychologically after informed consent during the first 3 days of their RT. The psychological assessment consisted of a semi-structured interview focusing on the patients’ life situation.

Following the interview, the patients filled out three questionnaires: The Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory (MFI, Smets et al. 1995) as a standardized measure to assess fatigue comprises 20 items covering general fatigue, physical fatigue, mental fatigue, reduced activity, and reduced motivation. The total score of the MFI was used as indicator of fatigue (Cronbach’s α = 0.91). The MFI has shown to be a reliable and valid measure of fatigue (Smets et al. 1995, 1996). Schwarz et al. (2003) have collected data in a sample representative for the population of Germany. The data from this study could be related to this normative sample.

The Resilience Scale (RS, Wagnild and Young 1993) is a 25-item instrument assessing resilience as a personality characteristic that is supposed to moderate negative effects of stress and to promote adaptation. The scale covers aspects of personal competence and the acceptance of self and life. The German version (Leppert and Strauss 2002) has been validated in a variety of clinical and non-clinical samples, and has been tested in a representative sample (Schumacher et al. 2005). Sample items of the RS are: “I feel that I can handle many things at a time.” “I can usually find something to laugh about.” “I usually manage one way or another.”

The SF-12 is a short version of the SF-36, an internationally well-established instrument to assess psychological and physical aspects of health related QoL (Ware Jr 1993). High scores in the SF-12 reflect better QoL. The instrument was analyzed using an algorithm (Bullinger and Kirchberger 1998) revealing aggregated scores for physical as well as psychological QoL. Normative data of a representative German sample were available.

Parameters related to the tumor, data describing radiation therapy (dosage, fractionation, irradiated volume, hemoglobin), its adverse effects (CTC), and the patients’ general medical status were registered systematically during treatment.

About 208 patients could be reached for a second assessment at the end of the RT (lasting between 4 and 8 weeks). The second assessment consisted of the MFI, the SF-12 and another brief interview covering the patients’ experiences.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed using the SPSS-12.0 and SAS-8.2-software (SPSS 2004; SAS Institute 2001). Descriptive statistics and group comparisons based upon ANOVAs and t-tests (including the calculations of the effect size, d) were used to analyze the data. To determine the relative influence of different predictors of fatigue, multiple regression analyses were performed. As a criterion for the inclusion of a predictor into the model, variables revealing effect sizes of d > 0.2 in the univariate analyses were selected. To select variables as predictors of the dependent variable, the minimized C p-value was used. Furthermore, the adjusted R 2-statistic was used to optimize the selection of the predictors. To estimate collinearity of the predictors, variance-inflation-factors were determined.

Results

Fatigue, resilience, and quality of life

Table 3 shows mean/SD of the psychological measures at the beginning and the end of RT and contrasts these to the normative samples using effect sizes. It can be seen that the mean total score of the MFI was considerably higher among the patients reflecting higher fatigue in the clinical sample t(189) = 8.61, P < 0.001. In contrast to the normative sample of healthy subjects, no significant differences within the clinical samples were observed between age groups (d = 0.05, NS) and between males and females (d = 0.04, NS).

Table 3.

Mean and SD of the psychological self-reports at the beginning (1) and end (2) of RT compared to age-corrected normative data

| Mean | SD | Mean norm sample | Effect size | t | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fatigue 1 | 51.4 | 16.6 | 41.0 | 0.63 | 8.61 |

| Fatigue 2 | 53.5 | 18.4 | 41.0 | 0.75 | 9.34 |

| Resilience 1 | 148.2 | 16.7 | 134.1 | 0.84 | 12.68 |

| QoL-physical (SF-12) 1 | 39.3 | 10.2 | 49.0 | 0.95 | −12.29 |

| QoL-psychological (SF-12) 1 | 49.1 | 10.5 | 52.2 | 0.30 | −3.85 |

| QoL-physical (SF-12) 2 | 39.9 | 9.7 | 49.0 | 0.95 | −12.24 |

| QoL-psychological (SF-12) 2 | 48.3 | 10.7 | 52.2 | 0.37 | −4.77 |

At the end of the radiation therapy, the total fatigue scores even were increased. The effect for the pre–post change in fatigue related to the entire sample was tested with the confidence interval (0.46–4.53) and turned out to be significant (overall mean at the beginning: 51.4, SD 16.4; at the end: 53.9, SD 18.5; increase in fatigue during RT: d = 0.14, t(189) = −2.06, P = 0.040). The correlation of the pre and post scores was 0.69 (Spearman’s Rho; P < 0.001).

With respect to the medical parameters it could be shown that palliatively treated patients revealed higher fatigue scores early in treatment than curatively treated patients [t(184) = 2.18, d = 0.45, P < 0.05]. Patients showing lower Karnofsky-Indices and more general symptoms according to the CTC at the beginning and at the end of RT also reported higher fatigue scores (Jonckheere–Terpstra test, P < 0.05). Other medical parameters obtained within this study (e.g., tumor localization, inpatient versus outpatient treatment, stage of cancer, pre-treatment, combined treatment) were not correlated with the MFI-scores.

Pre–post changes in fatigue scores from the beginning to the end of treatment were related to the treatment status (increase among patients with first RT, d = 0.46, P < 0.05, t(184) = 2.65; curatively treated, d = 0.54, P < 0.05, t(184) = −2.68, combination of RT and chemotherapy (increased scores, d = 0.49, P < 0.05, t(181) = −2.28), and the initial Karnofsky status (increase in patients with lower Karnofsky status, t(179) = −0.94, NS). Among the RT-related parameters, CTCs were not related to an increase in fatigue nor were the volume irradiated and radiation dosage. Whereas, there was no correlation between initial Hb-values and fatigue, a decrease of Hb during RT was clearly related to the intensity of fatigue at the end of RT (d = 0.47, P < 0.01 t(93) = −0.285).

With respect to the RS, the patients in total indicated a higher resilience than the norm population. Both samples did not reveal any significant gender or age differences (d < 0.09). The patients’ scores in the RS were not significantly related to diagnosis, treatment (curative versus palliative), pre-treatment, and treatment setting (inpatient versus outpatient; t < 1.24, d < 0.23, NS).

The patients physical subscore of the QoL measure (SF-12) turned out to be significantly lower than in the norm population, both at the beginning (39.3 vs. 49.0, d = 0.95 t(169) = −12.29, P < 0.001) and at the end of RT (39.9 vs. 49.0, d = 0.91, t(169) = −12.24, P < 0.001). The subscore related to psychological aspects of QoL was only slightly reduced (49.1 vs. 52.2, t(169) = −3.85, P < 0.001; 48.3 vs. 52.2, t(169) = −4.77, P < 0.001).

Changes in QoL during treatment were minimal (d < 0.17, NS). Early physical QoL was less impaired in outpatients, patients undergoing primary RT, and those who were treated curatively (d > 0.49, t(166) = −0.517, NS). Diagnosis and treatment variables were not related to the initial QoL measure. QoL changes appeared to be related to treatment status (increase in palliatively treated patients, patients treated repeatedly). In addition, patients with pre-treatments (chemotherapy/surgery) showed a decrease in the QoL scores. Other medical parameters where not significantly related to QoL.

As expected, the data in this sample revealed high negative correlations between the indices of QoL and patients’ fatigue, both, at the beginning and at the end of RT. The physical subscale of the SF-12 showed correlations of r = −0.62 and r = −0.69 (P < 0.001) with the MFI-total score, the psychological subscale was also negatively correlated with fatigue scores at the beginning (r = −0.46) and the end of the treatment (r = −0.59, P < 0.001). Using the psychological and the physical subscales of the SF-12, it could be shown that the patients’ resilience was not correlated with the physical QoL at the beginning (r = 0.08) and the end of RT (r = 0.08). In contrast, resilience scores were positively correlated with the patients’ psychological QoL at both times (r = 0.39, P < 0.001; r = 0.27, P < 0.001).

Predictors of fatigue

Within the total sample, the total resilience and fatigue scores were significantly and negatively correlated, both at the beginning (r = −0.35, P < 0.001) and at the end of RT (r = −0.22, P < 0.01). The correlations of resilience and the subscales of the MFI pointed into a similar direction (−0.16 < r < −0.41 at the beginning; −0.13 < r < −0.30 at the end). In contrast, the pre–post-difference of the fatigue scores was not significantly related to the patients resilience (r = 0.10, NS).

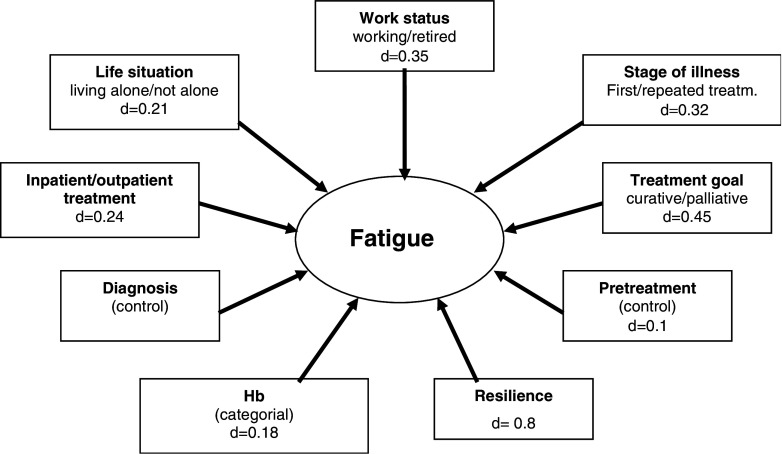

To determine the relative importance of resilience as a predictor of fatigue within the first days of RT, a variety of variables were tested within multiple regression equations according to the criteria described above, i.e., age, sex, life situation (living alone), employment, diagnosis, stage of illness, inpatient versus outpatient treatment, curative versus palliative treatment, pre-treatment, Hb, and resilience (cf. Fig. 1). A priori, resilience revealed the highest effect size among all potential predictors (d = 0.80). Table 4 reflects the final regression model with four remaining significant predictors in the regression equation. The final model explains 21% of the total variance. The values of the variance-inflation factors (VIF) did not exceed 1.11 (no collinearity). Resilience turned out to have the strongest impact on the total fatigue score at the beginning of treatment. Inpatients indicated higher fatigue than outpatients, so did patients under palliative versus curative treatment.

Fig. 1.

Variables of potential influence on the patients’ initial fatigue ratings entering the regression model (determined on the basis of univariate analyses, including effect size d)

Table 4.

Final regression model for the prediction of fatigue scores at the beginning of RT

| Variables in the model | Coefficient | Confidence intervals | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 131.0 | 110.0–152.0 | <0.001 |

| Work status (not working versus working) | −4.04 | −8.16–0.08 | 0.055 |

| Treatment (inpatient versus outpatient) | −5.36 | −9.86 to −0.86 | 0.020 |

| Treatment goal (curative versus palliative) | 6.40 | 11.90–0.90 | 0.023 |

| Resilience-score | −0.38 | −0.50 to −0.26 | <0.001 |

The table summarizes those variables selected on the basis of univariate comparisons (cf. Fig. 1) that remained in the regression model

In a second regression analysis, the pre–post change in fatigue between the two phases of treatment was used as a criterion. In addition to the variables mentioned above, early fatigue scores, changes in Hb-status, irradiated volume and total radiation dosage were included as potential predictors. The final model (cf. Table 5) revealed fatigue scores at the beginning of RT to be the strongest predictor of changes of fatigue during RT (low early fatigue predicts higher fatigue at the end). In addition, Hb-decrease during RT appeared to significantly influence fatigue change scores. Patients treated with RT for the first time showed a decrease in fatigue compared to patients in repeated RT. The significant predictors explain a total of 13.6% of the variance. Again, VIFs between 1.02 and 1.10 indicate no collinearity.

Table 5.

Final regression model for the prediction of pre–post changes in fatigue

| Variables in the model | Coefficient | Confidence intervals | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 19.3 | 10.8–27.8 | <0.001 |

| Stage of illness (basis first treatment) | −5.24 | −10.27 to −0.20 | 0.042 |

| Hb-decrease | 6.37 | 1.39–11.35 | 0.013 |

| Hb-increase | 0.20 | −4.65–5.05 | 0.935 |

| Fatigue (initial) | −0.23 | −0.35 to −0.11 | <0.001 |

Discussion

Although this study did not attempt to determine prevalence rates of fatigue, it clearly shows that fatigue is a salient problem in patients undergoing radio-oncology treatment. Levels of fatigue, measured with the MFI (Smets et al. 1996), appeared to be significantly higher in a sample of cancer patients undergoing RT compared to a normative sample (Schwarz et al. 2003), both, at the beginning and at the end of treatment. This result underlines the findings of other researchers, indicating that fatigue prominently contributes to suffering among cancer patients (AHRQ 2002). This is also confirmed by high negative correlations of fatigue symptoms and physical as well as psychological aspects of QoL (Weis and Bartsch 2000).

In total, the patients investigated in this study showed higher scores in the RS than a normative sample, which might be surprising on a first glance. On the other hand, it can be assumed that patients suffering from cancer are more sensitized to those aspects of their selves that are expressed by the RS, i.e., “personal competence,” “acceptance of self and life.” This sensitization or awareness and the mobilization of personal resources may explain the higher self-ratings of resilience.

As one could expect from developmental studies, resilience appeared to be largely independent from demographic, illness- and treatment-related variables.

As hypothesized, the concept turned out to be important as a correlate of fatigue ratings within this sample. Showing effect sizes between d = 0.4 and 0.6, resilience was clearly related to the patients’ fatigue at both phases of RT, but it did not predict changes in fatigue scores during treatment.

Although fatigue was additionally related to other factors such as the stage of illness, treatment goal of RT and the patients Hb-status (cf. Glaus and Müller 2000), multivariate data analysis clearly revealed resilience to be the strongest predictor of fatigue early in treatment. This suggests that fatigue is determined to some extent by the psychological capacity to deal with patterns of stress related to threat and illness at least at this time of RT. This result is in line with existing evidence that has shown resilience to be a predictor of QoL, coping, optimism, and even survival among cancer. On the other hand, the study indicates that resilience has little to do with treatment related fatigue, since the change scores could not be predicted on the basis of this psychological variable. Instead, (low) initial fatigue scores and a decrease of Hb during treatment turned out to be the best predictors of changes in fatigue from the beginning to the end of treatment. The influence of the Hb-status has already been described in the literature (e.g., Glaus and Müller 2000). One can assume that, since the treatment generally seems to affect the patients’ fatigue, those patients with lower initial symptoms have a greater risk to experience an increase of the symptoms during the course of RT.

The results that the initial fatigue clearly is related to the patients’ resilience might be of clinical relevance as far as psychological support is concerned: It has been mentioned that the results related to psychosocial interventions among cancer patients still are inconsistent. Apart from some contributions related to children and adolescents, the resilience concept has hardly been considered in the formulation of psychosocial interventions. It might be promising to increasingly focus on this construct and to provide strategies that improve resilience in patients who have to undergo stressful treatments like RT.

This study was related to a sample of 239 RT patients who where recruited consecutively in a radio-oncology unit of an university hospital. It is an open question if the sample really is representative. There are some indications showing the sample to be somewhat less impaired (cf. the CTC-related data) than radio-oncology patients usually are, probably due to the high proportion of patients treated with curative intent. It will be helpful to replicate this study in other units to clarify the question of representativeness and to further confirm resilience as a predictor of RT related complaints.

Since the study was conceptualized as a naturalistic study focusing most patients of the radio-oncological hospital, study participants were heterogeneous with regard to diagnosis, disease stage, inpatient versus outpatient status and other medical characteristics. Although these variables were controlled statistically, it cannot be excluded that the heterogeneity of the sample might have influenced the results, and that resilience may work different among patients with different cancers. A further limitation of the study is the lack of a true pre-treatment baseline measure. Due to organizational reasons, the patients could be first contacted during the first 3 days of their RT and not before treatment started.

Finally, no measure of depression was used within this study. Future studies should include measures of depression to rule out the possibility that depression could drive the association between resilience and fatigue.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the Wilhelm-Sander-Foundation (FKZ 2002.071.1).

References

- AHRQ (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality) (2002) Management of cancer symptoms: pain, depression, and fatigue. Evidence Report Number 61, US Department of Health and Human Services, Washington

- Antoni MH, Goodkin K (1988) Host moderator variables in the promotion of cervical neoplasia—personality facets. J Psychosom Res 32:327–338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bender D, Lösel F (1997) Risiko- und Schutzfaktoren in der Genese und der Bewältigung von Misshandlung und Vernachlässigung. In: Egle U, Hoffmann SO, Joraschky P (eds) Sexueller Missbrauch, Misshandlung, Vernachlässigung. Erkennung und Behandlung psychischer und Psychosomatischer Folgen früher Traumatisierungen, Schattauer, Stuttgart, pp 35–53 [Google Scholar]

- Bowen DJ, Morasca AA, Meischke H, et al (2003) Measures and correlates of resilience. Women Health 38:65–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bull AA, Meyerowitz BE, Hart S, et al (1999) Quality of life in women with recurrent breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 54:47–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullinger M, Kirchberger I (1998) SF-36 Fragebogen zum Gesundheitszustand. Handanweisung, Hogrefe, Göttingen [Google Scholar]

- Farber E, Schwartz A, Schaper P, et al (2000) Resilience factors associated with adaptation to HIV disease. Psychosomatics 41(2):140–146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaus A, Crow A, Hammond S (1996) A qualitative study to explore the concept of fatigue/tiredness in cancer patients and in healthy individuals. Support Care Cancer 4(2):82–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaus A, Müller S (2000) Hämoglobin und Müdigkeit bei Tumorpatienten: Untrennbare Zwillinge? Schweiz Med Wochenschr 130:471–477 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotay CC, Isaacs P, Pagano I (2003) Quality of life in patients who survive a dire prognosis compared to control cancer survivors. Psychooncology 13:882–892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haase JE, Heiney SP, Ruccione KS, et al (1999) Research triangulation to derive meaning-based quality of life theory: adolescent resilience model and instrument development. Int J Cancer 12(S):125–131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickok JT, Morrow GR, Mc Donald S, et al (1996) Frequency and correlates of fatigue in lung cancer patients receiving radiation therapy: implications for management. J Pain Symptom Manage 11(6):370–377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jereczek-Fossa BA, Marsiglia HR, Orecchia R (2002) Radiotherapy related fatigue. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 41:317–325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leppert K, Strauss B (2002) Resilienzskala. In: Brähler E, Schumacher J, Strauss B (eds) Psychodiagnostische Verfahren in der Psychotherapie. Hogrefe, Göttingen

- National Institute of Health State of the Science Panel (2003) Symptom management in cancer: pain, depression, and fatigue. J Natl Cancer Inst 95(15):1110–1117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson AE, Haase J, Kupst MJ, et al (2004) Consensus statements: interventions to enhance resilience and quality of life in adolescents with cancer. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs 21:305–307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newell S, Sanson-Fisher RW, Savolainen NJ (2002) Systematic review of psychological therapies for cancer patients: overview and recommendations for future research. J Natl Cancer Inst 94:558–584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parry C (2003) Embracing uncertainty: an exploration of the experiences of childhood cancer survivors. Qual Health Res 13:227–246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ream E, Richardson A (1997) Fatigue in patients with cancer and chronic obstructive airways disease: a phenomenological enquiry. Int J Nurs Stud 34(1):44–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M (1987) Psychosocial resilience and protective mechanisms. Am J Orthopsychiatry 57(3):316–331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute I (2001) SAS/STAT User’s Guide. Version 8.2. SAS Institute, Cary, NC

- Schumacher J, Leppert K, Gunzelmann T, et al (2005) Die Resilienzskala—Ein Fragebogen zur Erfassung der psychischen Widerstandsfähigkeit als Personmerkmal. Z Klin Psychol Psychiatr Psychother 53:16–39 [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz R, Krauss O, Hinz A (2003) Fatigue in the general population. Onkologie 26:140–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seegenschmidt MH, Haase W, Schnabel K, et al (1996) Leitlinien zur Dokumentation von Nebenwirkungen in der Radioonkologie. Strahlenther Onkol 172S:9–12 [Google Scholar]

- Smets E, Garssen B, Bonke B, et al (1995) The multidimensional fatigue inventory (MFI) psychometric qualities of an instrument to assess fatigue. J Psychosom Res 39(3):315–325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smets E, Garssen B, Cull A, et al (1996) Application of the multidimensional fatigue inventory (MFI-20) in cancer patients receiving radiotherapy. Br J Cancer 73:241–245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smets E, Visser M, Willems-Groot A, et al (1998a) Fatigue and radiotherapy: (A) experience in patients undergoing treatment. Br J Cancer 78(7):899–906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smets E, Visser M, Willems-Groot A, et al (1998b) Fatigue and radiotherapy: (B) experience in patients 9 months following treatment. Br J Cancer 78(7):907–912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SPSS Inc. (2004) SPSS Base 12.0 User’s Guide. SPSS, Chicago

- Stasi R, Abriani L, Beccaglia P, et al (2003) Cancer-related fatigue: evolving concepts in evaluation and treatment. Cancer 98(9):1786–1801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staudinger M, Marsiske M, Baltes P (1996b) Resilience and levels of reserve capacity in later adulthood: perspectives from life-span-theory. Dev Psychopathol 5:541–566 [Google Scholar]

- Staudinger U, Freund A (1998) Krank und “arm” im hohen Alter und trotzdem guten Mutes? Z Klin Psychol 27(2):78–85 [Google Scholar]

- Staudinger U, Freund A, Linden M, et al (1996a) Selbst, Persönlichkeit und Lebensgestaltung im Alter: Psychologische Widerstandsfähigkeit und Vulnerabilität. In: Mayer KU, Baltes PB (eds) Die berliner altersstudie. Akademie-Verlag, Berlin, pp 321–350 [Google Scholar]

- Stewart DE, Wong F, Duff S, et al (2001) “What doesn’t kill you makes you stronger”: an ovarian cancer study. Gynecol Oncol 83:537–543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone P, Richards M, Hardy J (1998) Review: fatigue in patients with cancer. Eur J Cancer 34(11):1670–1676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surtess P, Wainwright N, Luben R, et al (2004) Sense of coherence and mortality in men and women in the EPIC-Norfol UK prospective cohort study. Am J Epidemiol 159:1202–1203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visser M, Smets E (1998) Fatigue, depression and quality of life in cancer patients: how are they related? Support Care Cancer 6:101–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagnild GM, Young HM (1993) Development and psychometric evaluation of the resilience scale. J Nurs Meas 1:165–178 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware JE Jr (1993) SF-36 health survey: manual and interpretation guide. The Health Institute, New England Medical Center, Boston, MA [Google Scholar]

- Weis J, Bartsch HH (2000) Fatigue nach Krebs: eine neue Herausforderung für Therapie und Rehabilitation. Karger, Basel [Google Scholar]

- Wenzel LB, Donnelly JP, Fowler JM, et al (2002) Resilience, reflection, and residual stress in ovarian cancer survivorship. Psychooncology 11:142–153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodgate RL (1999a) Conceptual understanding of resilience in the adolescent with cancer Part I. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs 16:35–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodgate RL (1999b) Conceptual understanding of resilience in the adolescent with cancer Part II. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs 16:78–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]