Abstract

Silymarin is a polyphenolic flavonoid that has a strong antioxidant activity and exhibits anti-carcinogenic, anti-inflammatory, and cytoprotective effects. Although its hepatoprotective effect has been well documented, the effect of silymarin on T cells is largely unknown. The purpose of this study was to analyze the effects of the silymarin on the proliferation and cell cycle progression of Jurkat cells, a human peripheral blood leukemia T cell line. Cells were incubated with various concentrations of silymarin for 24–72 h and examined for cell growth and proliferation using 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) and DNA 5-bromo 2′-deoxyuridine (BrdU) colorimetric assays. Cell cycle analysis by flow cytometry was also performed using propidium iodide staining. Results of the study revealed that silymarin increased proliferation of Jurkat cells at 50–400 μM concentrations with 24 h exposure, confirmed by both MTT and BrdU assays. However, Jurkat incubation with silymarin at higher concentrations of 400 μM for 48 h and 200–400 μM for 72 h caused inhibition of DNA synthesis, cell cycle arrest at the G2/M phase and significant cell death. Results of the present study also revealed a similarity of cell growth patterns between Jurkat, U937 and RPMI 8866 cells. In conclusion, this study demonstrated an in vitro growth stimulatory effect of silymarin on leukemia cells with monocyte, T and B cell origin that has not been previously reported for either solid tumors or other leukemia cells, suggesting a possible specific stimulatory effect of silymarin on the key cells of the immune system.

Keywords: Silymarin, Cell cycle, Leukemia cell line

Introduction

Flavonoids are a group of naturally occurring compounds that are commonly found in most plants. These polyphenolic compounds display a remarkable spectrum of biochemical activities affecting basic cell functions such as proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis (Middleton et al. 2000). In addition, they have been recognized as a dietary chemopreventive agent that may block neoplastic inception or delay tumor progression (Kanadaswami et al. 2005; HemaIswarya and Doble 2006; Singh and Agarwal 2006a; Sarkar and Li 2006).

Among the flavonoids, Silymarin is a unique flavonoid complex, containing silybin, silydianin, and silychrisin, derived from the milk thistle (Silybum marianum (L.) Gaertn). These unique phytochemicals have been the subject of decades of research into their beneficial properties. Silymarin and one of its structural components, Silybin, are well known for their anti-inflammatory, hepatoprotective, and anti-carcinogenic effects (Kren and Walterova 2005; Valenzuela and Garrido 1994). Various studies indicate that silymarin exhibits strong anti-oxidant activity, increases cellular glutathione content, and induces superoxide dismutase. By inhibiting lipid peroxidation, silymarin protects against hepatic toxicity induced by a wide variety of agents (Crocenzi and Roma 2006; Wellington and Jarvis 2001). Besides its hepatoprotective properties, silymarin is a potent chemopreventive agent (McCarty and Block 2006; Agarwal and Shishodia 2006). It provides substantial protection against various stages of UVB-induced carcinogenesis and blocks phorbol ester-induced tumor promotion. Moreover, the anti-carcinogenic effect of silymarin in human prostate and breast carcinoma cell lines as well as in different skin tumor animal models have been previously documented (Singh and Agarwal 2005, 2006; Davis-Searles et al. 2005; Tyagi et al. 2004; Singh et al. 2006).

Several studies have also reported immunomodulatory actions of silymarin. It increases lymphocyte proliferation, interferon gamma, interleukin (IL)-4 and IL-10 secretions by stimulated lymphocytes in a dose-dependent manner (Wilasrusmee et al. 2002). It has been shown that in vitro treatment of peripheral blood mononuclear cells with silymarin causes restoration of the thiol status and increases in T cell proliferation and activation (Alidoost et al. 2006; Dietzmann et al. 2002). The stimulatory effect of silymarin on the response of human peripheral blood lymphocytes to mitogens has been reported in patients with alcoholic cirrhosis following daily oral administration of 280 mg Legalon® (Lang et al. 1988, 1990). Strikingly, in the mouse model of concanavalin A (Con A)-induced T cell-dependent hepatitis, silibinin was proven to suppress T cell-dependent liver injury, inhibiting intrahepatic expression of tumor necrosis factor, interferon-gamma, IL-4, IL-2, and iNOS (Schumann et al. 2003). It has been also reported that silybin inhibits in vitro lymphocyte blastogenesis induced by stimulation via anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody or lectins such as phytohaemagglutinin, Con A and pokeweed (Meroni et al. 1988). Accordingly, silymarin is a potent immune-response modulator, with both immunostimulatory and immunosuppressive activities, which may be dependent on its concentration and/or treatment procedure. Despite the studies described above highlighting immunomodulatory activities of silymarin in normal lymphocytes and considering the inhibitory effect of this agent on various tumor cells, the effect of silymarin on T cell leukemia remains to be investigated. In the present study, the in vitro effect of silymarin on the spontaneous proliferation, cell cycle progression and apoptosis of human peripheral blood leukemia T cells was investigated. To compare the immunomodulatory activity of silymarin on different types of leukemia cells, its effect on the proliferation and viability of U937 and RPMI 8866 cell lines were further studied. Regarding hepatopritective activity of silymarin, human hepatocellular liver carcinoma cell line (HepG2) was used as a control cell line with a different origin of leukemia cells.

Materials and methods

Cell lines and reagents

Jurkat E6.1 (human peripheral blood leukemia T cell line), U937 (human leukemic monocyte lymphoma cell line), RPMI 8866 (human peripheral blood leukemia B cell line), and HepG2 (human hepatocellular liver carcinoma cell line) were supplied from the bank of the Pastor Institute (Iran). RPMI 1640, fetal bovine serum (FBS) and trypsin were obtained from GIBCO-BRL (Germany). Silymarin, 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) dye, propidium iodide (PI), and RNase were purchased from Sigma (USA). All other chemicals were of analytical grade and purchased locally.

Cell culture and drug treatment

Cells were maintained in complete RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FBS, penicillin (100 U/ml) and streptomycin (100 μg/ml) under standard culture conditions (37°C, 95% humidified atmosphere with and 5% CO2). Culture media were changed every 2–3 days. Silymarin was dissolved in 100% DMSO to obtain a 100 mM stock solution. The aliquots were stored at −20°C for no longer than 30 days. All subsequent dilutions were made in RPMI medium. Jurkat cells were treated with Silymarin at 50–400 μM concentrations for varying lengths of time. Negative control cells were treated with DMSO and RPMI. The final concentration of DMSO in control wells was equal to test wells.

MTT assay

A colorimetric assay using (MTT) was performed. Briefly, cells were seeded at 2.5 × 104 cells/well in flat-bottom 96-well culture plates and treated with 50, 100, 200 or 400 μM of silymarin for either 24, 48 or 72 h. About 10 μl of 5 mg/ml MTT solution was added to each well, and the cultures further incubated for 4 h at 37°C. Cells were then resuspended in 100 μl of 0.04 M HCl/isopropanol solution and incubation was continued for 2 h to solubilize formazan violet crystals in the cells. The absorbance of each well was determined by spectrophotometry at the dual wavelengths of 570 and 630 nm on a microplate reader (Pharmacia, Sweden). For adherent HepG2 cells, media were removed and formazan violet crystals were dissolved in 200 μl of DMSO. After incubating the plate in 37°C for 5 min, absorbance of each well was determined at 550 nm. Taking into consideration that the MTT tetrazolium assay may lead to false-positive results when testing natural compounds with intrinsic reductive potential (Bruggisser et al. 2002), the direct reductive potential of silymarin was observed in a cell-free system. The absorbance of these control wells was then subtracted from the absorbance of wells containing both silymarin and cells. Viability percentage was calculated according to the following formula: (OD of treated cells/OD of corresponding control) × 100.

PI staining for cytotoxicity

Cytotoxicity of silymarin was evaluated by PI staining. Jurkat cells (2.5 × 105 per ml) were cultured in 24-well culture plates and treated with various concentrations of silymarin for different incubation times. Cells were then harvested and washed with PBS and re-suspended in 500 μl PBS containing 1 μl PI stock solution (1 mg/ml). Samples were kept in PI staining solution at 4°C protected from light until analysis on the flow cytometer (FACSCalibur, Becton Dickinson, USA). Cytotoxicity index was calculated according to this formula: (Percentage of PI positive treated cells/corresponding control) × 100.

DNA 5-bromo 2′-deoxyuridine (BrdU) incorporation assay

The effect of silymarin on the proliferation of Jurkat cells was assessed by BrdU incorporation into the nucleus using a colorimetric ELISA kit (Roche, Germany). In brief, cells (1 × 105) were cultured in flat-bottom 96-well plates for 1–3 days in the presence or the absence of various concentrations of silymarin. Subsequent to labeling with 10 μM of BrdU (for the final 18 h of the incubation period), DNA was then denatured and cells were incubated with anti-BrdU monoclonal antibody, prior to the addition of substrate. The reaction product was quantified by measuring absorbance at 450 nm.

Flow cytometric analysis for apoptosis and cell cycle

Cells were treated with either DMSO alone or various doses of silymarin. After 24, 48 and 72 h of treatment, cells were aspirated and quickly washed with cold PBS. Approximately 1 × 106 cells were suspended in 0.5 ml cold hypotonic solution containing 50 μg/ml PI, 0.1% Triton X-100, 0.1% sodium citrate solution and 100 μg/ml RNase. Tubes were placed in the dark at 4°C. Analysis by flow cytometry was performed after minimum 20 min incubation time, within 2 h of hypotonic treatment. Flow cytometric data were analyzed using WinMDI version 2.8. Cell cycle analysis of DNA histograms was performed in Cylchred program.

Statistical analysis

Results are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation. Statistical differences were assessed with the analysis of variances followed by Dunnett’s (2-sided) comparison test. The significance level was set at 0.05.

Results

Effect of silymarin on the viability and membrane integrity of Jurkat cell line

The cellular growth index of Jurkat cells was determined using a standard MTT colorimetric assay, where reduction of yellow MTT substrate to purple formazan is directly related to activity of mitochondrial reductase enzymes and therefore the number of viable cells. Initially, at lower doses of silymarin (50–100 μM) and during shorter treatment times (24 h) an increase in MTT reduction was observed, indicating an increase in cellular proliferation in Jurkat cells (Fig. 1). Interestingly, a decrease in MTT reduction was observed at higher doses of silymarin, even more so with extended treatment, such that the growth index dropped below that of controls. Together these data indicate that silymarin elicits both immunostimulatory and immunosuppressive effects on Jurkat cells.

Fig. 1.

Effect of silymarin on the viability of Jurkat cells measured by MTT assay. Results are expressed as the mean of Jurkat cell viability ± standard deviation compared to the control. Control for 50 and 100 μM silymarin: untreated cells, and for higher concentrations: DMSO at a final concentration equal to test wells. At the concentrations of less than 200 μM, silymarin significantly increased the OD of all the test wells in comparison with the controls, but at higher doses viability was decreased in a dose- and time-dependent manner. Asterisks represent statistical significance (P < 0.05)

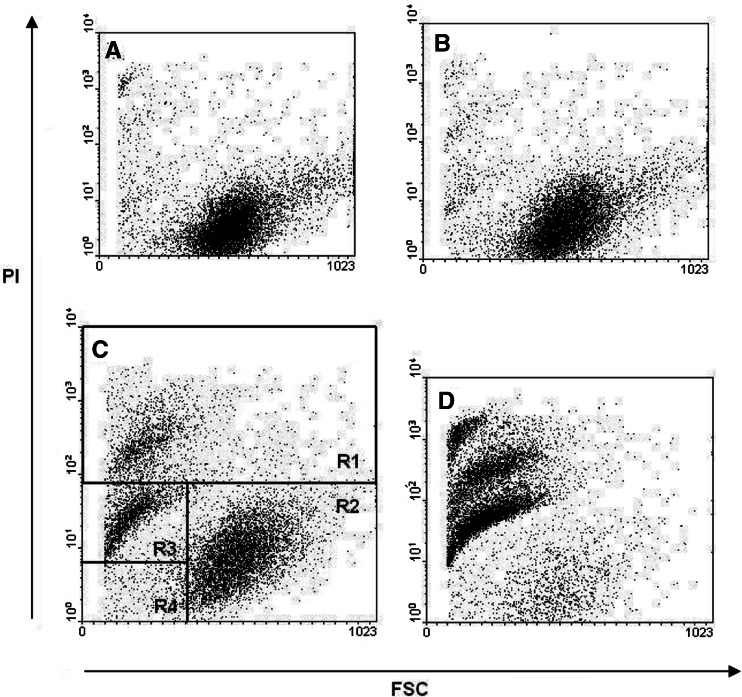

To examine whether this decreased MTT reduction was the result of a reduced number of viable cells or due to a decrease in cell proliferation, PI exclusion was used to distinguish dead cells with respect to loss of cell membrane integrity. At lower doses of silymarin (50–100 μM) cell viability was not compromised, regardless of the duration of treatment, however, at higher doses cell cytotoxicity significantly increased in a dose- and time-dependent manner (Fig. 2). This analysis demonstrated the presence of several different cell populations based on their forward scatter (FSC) and PI staining profile (Fig. 3). Three distinct cell populations were detected in samples exposed to higher concentrations of silymarin. The FSC-low and PI-positive population represents dead/dying cells small in size and partially permeable to PI but still relatively intact (region R3 in Fig. 3c). Similarly, cells with a small FSC profile with high PI staining represent dead cells, with little or no membrane integrity (region R1 in Fig. 3c). Live cells were FCS-high and PI-negative (region R2 in Fig. 3c).

Fig. 2.

Determination of silymarin cytotoxicity on Jurkat cells by PI staining and flow cytometric analysis. The percentage of PI-positive cells after treatment with different concentrations of silymarin was expressed as the cytotoxicity index. Control for 50 and 100 μM silymarin: untreated cells, and for higher concentrations: DMSO in the final concentration equal to test wells. The values are presented as mean of four different experiments. Asterisks represent statistical significance (P < 0.05)

Fig. 3.

Discrimination of live and dead cells by PI staining. At least 10,000 events were collected using a FACS Calibur. Data were analyzed by gating cell populations according to forward scatter (FSC, x-axis) vs. PI log fluorescence (y-axis). Dot plots from A to D represent 50, 100, 200 and 400 μM silymarin treatment respectively after 48 h incubation. Region R1 dead cells with high PI fluorescence; region R2 live cells with low PI fluorescence; region R3 dying/apoptotic cells with dim PI fluorescence; and region R4 cell debris

Effect of silymarin on the proliferation of Jurkat cell line

Proliferation of Jurkat cells exposed to the increasing concentrations of silymarin for 24–72 h was examined by a BrdU incorporation assay. As shown in Fig. 4, silymarin stimulated DNA synthesis at a concentration of 50–400 μM, with 24–48 h exposure. In fact, a maximum stimulation of 166% was obtained with 200 μM silymarin and 24 h of treatment. This stimulatory effect associated with low concentrations of silymarin diminished and was gradually replaced by an inhibitory effect on DNA synthesis when treatment time increased up to 72 h with 400 μM silymarin. These results were consistent with the results of the MTT assay.

Fig. 4.

Effect of silymarin on cell proliferation determined by DNA (BrdU) incorporation assay. Growth index was calculated as described for MTT assay. All treatment conditions at concentrations less than 400 μM exhibited a significant increase in proliferation when treated with silymarin in comparison with controls. However, extended treatment with silymarin reduced the proliferation observed compared with both shorter treatment periods and controls. Asterisks represent statistical significance (P < 0.05)

Effect of silymarin on the apoptosis and cell cycle distribution of Jurkat cell line

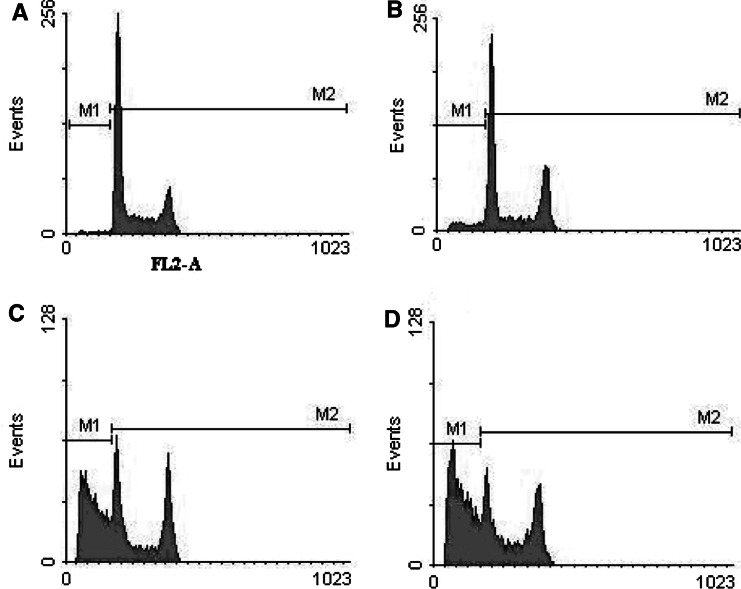

Following the observation of the apparently opposing immunomodulatory effects of silymarin, the cellular DNA content was analyzed to evaluate whether the immunoinhibitory effect was related to apoptosis. To determine at which phase the cells were arrested, cell cycle analysis was conducted by flow cytometry. Cells with sub-G1 DNA content were quantified and classified as apoptotic cells. Results displayed in Fig. 5 are representative histograms showing that silymarin induces apoptosis of Jurkat cells in a dose-dependent manner following 72 h of stimulation. In addition, it was observed that apoptosis increased in a time-dependent manner from 24 to 72 h (Table 1). The ratio of apoptotic cells significantly increases after the administration of 200 and 400 μM silymarin for 48 and 72 h incubation periods. Table 1 describes the cell cycle results for each concentration and time point variable. After 24 h of treatment with silymarin, no significant change in cell cycle phase was detected at all concentrations; however, a significant accumulation of cells in G2 M was observed with the treatment of silymarin at a concentration of 400 μM for 48 h and S/G2 M at 200–400 μM after 72 h. Also, the proportion of G1 phase cells was markedly decreased in 400 μM treated cells for 48 and 72 h incubations. These results indicate that silymarin treatment caused S/G2 M arrest in Jurkat cells. The percentage of apoptotic cells also increased significantly 48 and 72 h after treatment, suggesting that silymarin promotes S/G2 M arrest followed by apoptosis in Jurkat cells. Furthermore, it was observed that in the presence of DMSO, Jurkat cells experienced G1 arrest, whereas the cells grown in silymarin accumulated in the S and G2/M phases, with a decrease in the G1 phase after 2–3 days of silymarin treatment, demonstrating the different modes of action of these two agents (Table 1).

Fig. 5.

Effect of silymarin on apoptosis and cell cycle of Jurkat cells. Propidium iodide (PI) florescent intensity was measured by flow cytometry. Histograms A–D indicate apoptosis and cell cycle patterns of Jurkat cells treated 72 h with 50, 100, 200, and 400 μM silymarin, respectively. The ratio of cells with sub-G1 DNA content (M1 fraction) significantly increases after administration of 200 and 400 μM silymarin for 48 and 72 h incubation

Table 1.

Apoptosis and cell cycle of Jurkat cells treated with different silymarin concentrations for different incubation times

| Cycle phase | Incubation time | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sub G1 | 24 | 48 | 72 | |

| DMSO | 0 | 0.9 ± 0.11 | 0.93 ± 0.15 | 1.47 ± 0.17 |

| 200 | 2.11 ± 0.25 | 1.58 ± 0.21 | 2.0 ± 0.02 | |

| 400 | 7.94 ± 1.2* | 6.99 ± 0.58* | 15.1 ± 3.36* | |

| Silymarin (μM) | 50 | 1.18 ± 0.7 | 1.58 ± 0.23 | 2.08 ± 0.56 |

| 100 | 1.67 ± 0.5 | 4.84 ± 1.34 | 6.0 ± 2.4 | |

| 200 | 2.94 ± 0.15 | 8.76 ± 1.06* | 25.5 ± 5.4* | |

| 400 | 13 ± 3.83 | 18.40 ± 2.62* | 43.55 ± 6.25* | |

| G1 | 24 | 48 | 72 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DMSO | 0 | 41.7 ± 0.34 | 43 ± 0.2 | 42.4 ± 0.4 |

| 200 | 42.9 ± 2.0 | 51.3 ± 1.2 | 46.4 ± 2.4 | |

| 400 | 43.9 ± 4.0 | 79.5 ± 5.5* | 69.7 ± 3.9* | |

| Silymarin (μM) | 50 | 44.4 ± 2.1 | 47.4 ± 4.3 | 50.4 ± 1.6 |

| 100 | 43.8 ± 2.6 | 46.4 ± 2.7 | 45.6 ± 0.1 | |

| 200 | 47.0 ± 1.1 | 47.4 ± 8.5 | 38.2 ± 2.2 | |

| 400 | 40.4 ± 1.5 | 23.1 ± 8.2* | 31.1 ± 5.9* | |

| S | 24 | 48 | 72 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DMSO | 0 | 46.1 ± 1.2 | 45.6 ± 1.5 | 48.5 ± 0.7 |

| 200 | 42.5 ± 3.1 | 41.0 ± 2.6 | 47.8 ± 3.1 | |

| 400 | 41.7 ± 1.4 | 12.7 ± 2.6* | 20.8 ± 4.5* | |

| Silymarin (μM) | 50 | 44.4 ± 2.1 | 44.7 ± 1.2 | 34.6 ± 1.8 |

| 100 | 43.8 ± 2.7 | 45.5 ± 2.7 | 40.6 ± 4.4 | |

| 200 | 47.0 ± 3.1 | 35.3 ± 3.5 | 35.9 ± 2.9 | |

| 400 | 40.4 ± 3.2 | 49.3 ± 2.2* | 45.9 ± 3.1* | |

| G2/M | 24 | 48 | 72 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DMSO | 0 | 12.6 ± 1.2 | 11 ± 1.5 | 9.1 ± 0.4 |

| 200 | 14.1 ± 1.5 | 7.7 ± 2.6 | 5.7 ± 0.7* | |

| 400 | 14.9 ± 0.7 | 8.8 ± 2.6 | 9.4 ± 1.9* | |

| Silymarin (μM) | 50 | 11.5 ± 1.1 | 5.4 ± 1.2 | 13.9 ± 1.4 |

| 100 | 10.6 ± 2.2 | 9.9 ± 2.7 | 14 ± 1.4 | |

| 200 | 13.3 ± 2.1 | 11.8 ± 3.5 | 24.3 ± 2.0* | |

| 400 | 19.5 ± 0.7 | 22.3 ± 2.2* | 27.2 ± 6.8* | |

Data present the percentage of cells in each phase of the cell cycle. Asterisks represent statistical significance when compared with corresponding control (P < 0.05). Controls for 50–100 μM silymarin samples were untreated cells and 200–400 μM silymarin controls were treated with 200–400 μM DMSO to give a final concentration of DMSO (silymarin diluent) equal to test wells

Effects of silymarin on the proliferation and viability of U937, RPMI 8866, and HepG2 cells lines

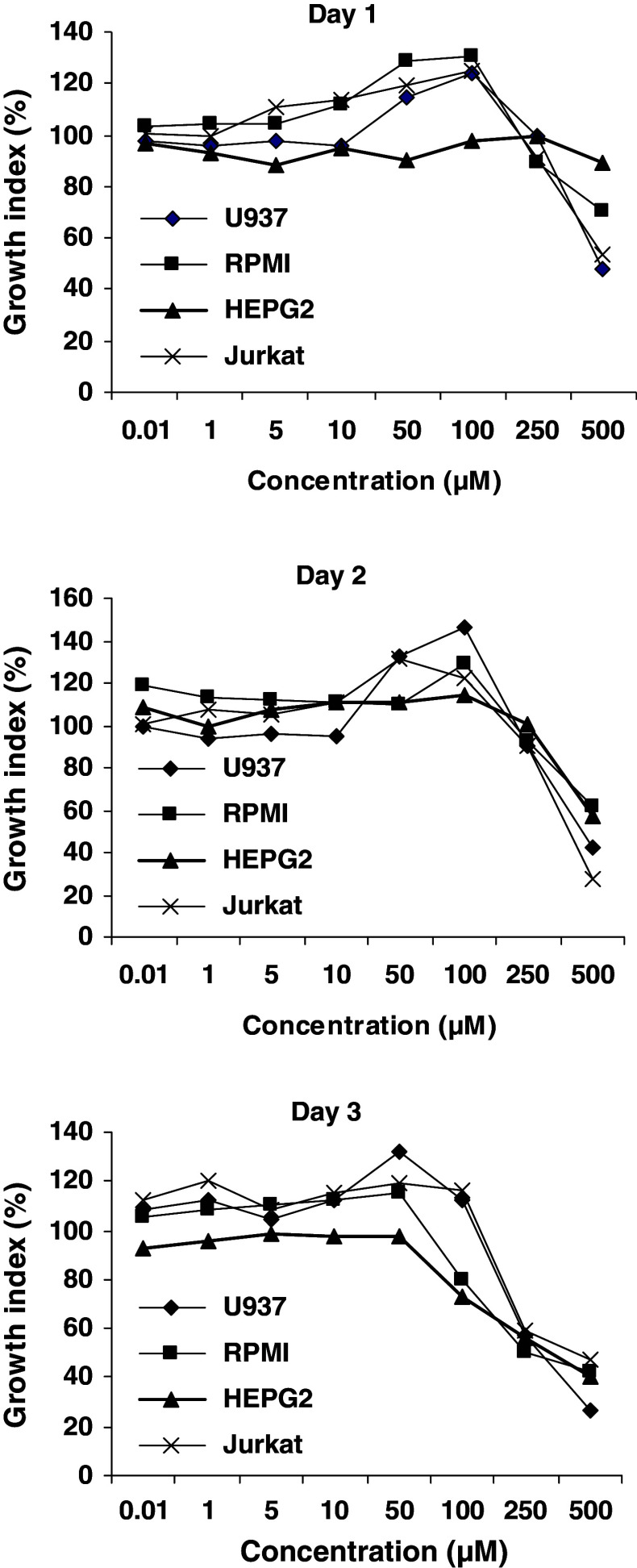

The growth of cells exposed to increasing concentrations of silymarin for 1–3 days was examined by MTT assay. As shown in Fig. 6, the profile of cell growth stimulation by silymarin in U937 and RPMI 8866 cell lines was similar to Jurkat cells at all concentrations and incubation periods. At the concentrations of 50 μM or lower, no stimulatory effect of silymarin was detected; however, its stimulatory effect was gradually observed from 50 to 100 μM. The cytotoxic effects on cells appeared when silymarin concentrations were higher than 200 μM.

Fig. 6.

Comparison of silymarin effect on the viability and growth of Jurkat, U937, RPMI 8866, and HepG2 cells, determined by MTT assay. Result was expressed as the mean of viability of cells compared to the control. DMSO in the final concentration was equal to test wells. In concentrations 50–100 μM, silymarin increased growth and viability of all cell lines except HepG2

In contrast, silymarin treatment did not increase the growth of HepG2 cells. However, the inhibitory effect on HepG2 growth was observed after 3 days treatment with 100 μM of silymarin (Fig. 6).

Discussion

Recently, silibinin and silymarin have received attention regarding their anti-proliferative and anti-carcinogenic effects with respect to prostate, breast, and skin neoplasia in both short-term cell culture models and long-term in vivo protocols (Singh et al. 2006). In vitro treatment of cancer cells with silymarin or silibinin at pharmacologically achievable and nontoxic doses (≤100 μM) resulted in a moderate to very strong growth inhibition, largely due to a G0/G1 arrest in cell cycle progression. Molecular studies have demonstrated that silibinin toxicity to cancer cells involves the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor, and nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) pathways (Singh and Agarwal 2006b; Singh et al. 2005, 2006; Qi et al. 2003; Hannay and Yu 2003). In this instance, addition of silibinin was shown to inhibit EGFR activation. Molecular modeling of silibinin revealed that it interacts with erbB1, thereby interfering with the EGF-erbB1 interaction and resulting in inhibition of downstream cytoplasmic signaling and Shc activation. These effects cause G1 arrest in cell cycle progression followed by cell growth inhibition (Singh and Agarwal 2006b; Singh et al. 2005, 2006; Qi et al. 2003; Hannay and Yu 2003).

The present study demonstrated that silymarin induced significant apoptosis in Jurkat cells at higher doses with longer treatment times. It is known that EGFR is expressed in epithelial, mesenchymal, and neuronal tissues and its expression is highly increased in lung, colon, breast, prostate, gastric, ovarian, and head and neck tumors (Bazley and Gullick 2005; Sundaresan et al. 1998). Regarding the anti-carcinogenic mechanism of silymarin summarized above, it is reasonable to speculate that lack of EGFR expression on Jurkat cells could be a reason for cell resistance to growth inhibitory effect of silymarin. Conversely, a recently published study has reported the apoptotic effect of silymarin in K562 leukemia cells through induction of caspases and inactivation of Akt pathway (Zhong et al. 2006), suggesting another possible pathway to induce cancer cell toxicity by silymarin. Besides K562 cells, which were highly susceptible to apoptosis induced by 100 μg/ml silymarin, treatment of the promyelocytic leukemia HL-60 cells with 50 μg/ml of silibinin significantly inhibited cell proliferation (Kang et al. 2001). In contrast with these previous findings in leukemia cells, the present study showed no apoptotic and anti-proliferative activities for silymarin on Jurkat cells at the same culture condition. A similar result was also obtained for two other leukemia cell lines including U937 and RPMI 8866. These observations indicate that the different reaction of leukemia cells to silymarin treatment probably depends on cell type and stage of differentiation.

Cell cycle analysis demonstrated that silymarin caused G2/M arrest in Jurkat cells at higher doses and with longer incubation time. In view of the fact that the G2/M checkpoint blocks the entry of cells into mitosis when DNA is damaged (Shapiro and Harper 1999), silymarin possibly induced cell toxicity via DNA damage at higher doses.

Results of the present study also revealed that silymarin increased proliferation of Jurkat cells at lower concentrations and over shorter incubation periods, confirmed by both MTT and BrdU assays. This finding could be considered as a further evidence to demonstrate the immunostimulatory effect of silymarin and is in consistent with the previously reported capability of silymarin to stimulate cell growth in normal liver, kidney, and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (Valenzuela and Garrido 1994; Alidoost et al. 2006; Sonnenbichler et al. 1999).

Several studies have investigated the molecular mechanisms of the stimulatory and cytoprotective actions of silymarin. Three levels of action have been proposed for silymarin in experimental animal models: (I) as an anti-oxidant, by scavenging pro-oxidant free radicals and by increasing the intracellular concentration of the glutathione; (II) a regulatory action of the cellular membrane permeability and increase in its stability against xenobiotic injury; and (III) via nuclear expression, by increasing the synthesis of ribosomal RNA and exerting a steroid-like regulatory action on DNA transcription. The enzymatic activity of DNA-dependent RNA-polymerase I is stimulated by silymarin, which subsequently accelerates the synthesis of 28S, 18S, and 5.8S ribosomal RNAs and also promotes the formation of complete ribosomes. Thus, protein biosynthesis is indirectly intensified (Valenzuela and Garrido 1994; Alidoost et al. 2006, Sonnenbichler et al. 1986; Sonnenbichler and Zetl 1986). Although, in view of this biochemical mechanism, similar action of silymarin on the peripheral blood mononuclear cells and Jurkat cells that are considered to be similar to resting T cells is justified, a common cell growth pattern detected between Jurkat, U937 and RPMI 8866 cells, indicates that silmarin could act as a promoter of cell growth of certain leukemia cells.

In conclusion, despite the fact that silymarin has been shown to induce cell death in various cancer cells, it was well tolerated by Jurkat, U937, and RPMI 8866 cell lines. Cell growth augmentation detected in these leukemia cells suggests that depending on the cell type, silymarin acts differently; stimulating the growth of some normal and leukemia cells, while inhibiting the growth of other malignant cells.

This study provokes an interest in understanding the molecular mechanism of the immunomodulatory effects of silymarin on lymphocytes and monocytes. Characterizing the molecular mechanism of such immunomodulatory effects may have a great potential in future practical applications for immunopharmacology and cancer therapy.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grant 1929 from Shiraz University of Medical Sciences. The authors wish to acknowledge Dr. Katherine Pilkington from Detmold Family Imaging Suite, Institute of Medical and Veterinary Science, Adelaide, South Australia, for critical editing of the manuscript and invaluable comments.

References

- Agarwal BB, Shishodia S (2006) Molecular targets of dietary agents for prevention and therapy of cancer. Biochem Pharmacol 71:1397–1421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alidoost F, Gharagozloo M, Bagherpour B, Jafarian A, Sajjadi SE, Hourfar H, Moayedi B (2006) Effects of silymarin on the proliferation and glutathione levels of peripheral blood mononuclear cells from beta-thalassemia major patients. Int Immunopharmacol 6:1305–1310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazley LA, Gullick WJ (2005) The epidermal growth factor receptor family. Endocr Relat Cancer 12:S17–S27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruggisser R, von Daeniken K, Jundt G, Schaffner W, Tullberg-Reinert H (2002) Interference of plant extracts, phytoestrogens and antioxidants with the MTT tetrazolium assay. Planta Med 68:445–448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crocenzi FA, Roma MG (2006) Silymarin as a new hepatoprotective agent in experimental cholestasis: new possibilities for an ancient medication. Curr Med Chem 13:1055–1074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis-Searles PR, Nakanishi Y, Kim NC, Graf TN, Oberlies NH, Wani MC, Wall ME, Agarwal R, Kroll DJ. (2005) Milk thistle and prostate cancer: differential effects of pure flavonolignans from Silybum marianum on antiproliferative end points in human prostate carcinoma cells. Cancer Res 65:4448–4457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietzmann J, Thiel U, Ansorge S, Neumann KH, Tager M (2002) Thiol-inducing and immunoregulatory effects of flavonoids in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from patients with end-stage diabetic nephropathy. Free Radic Biol Med 33:1347–1354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannay JA, Yu D (2003) Silibinin: a thorny therapeutic for EGF-R expressing tumors? Cancer Biol Ther 2:532–533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HemaIswarya S, Doble M (2006) Potential synergism of natural products in the treatment of cancer. Phytother Res 20:239–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanadaswami C, Lee LT, Lee PP, Hwang JJ, Ke FC, Huang YT, Lee MT (2005) The antitumor activities of flavonoids. In Vivo 19:895–909 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang SN, Lee MH, Kim KM, Cho D, Kim TS (2001) Induction of human promyelocytic leukemia HL-60 cell differentiation into monocytes by silibinin: involvement of protein kinase C. Biochem Pharmacol 61:1487–1495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kren V, Walterova D (2005) Silybin and silymarin: new effects and applications. Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub 149:29–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang I, Deak G, Nekam K, Muzes G, Gonzalez-Cabello R, Gergely P, Feher J (1988) Hepatoprotective and immunomodulatory effects of antioxidant therapy. Acta Med Hung 45:287–295 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang I, Nekam K, Deak G, Muzes G, Gonzales-Cabello R, Gergely P, Cisomos G, Feher J (1990) Immunomodulatory and hepatoprotective effects of in vivo treatment with free radical scavengers. Ital J Gastroenterol 22:283–287 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarty MF, Block KI (2006) Toward a core nutraceutical program for cancer management. Integr Cancer Ther 5:150–171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meroni PL, Barcellini W, Borghi MO, Vismara A, Ferraro G, Ciani D, Zanussi C (1988) Silybin inhibition of human T-lymphocyte activation. Int J Tissue React 10:177–181 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middleton EJ, Kandaswami C, Theoharides TC (2000) The effects of plant flavonoids on mammalian cells: implications for inflammation, heart disease, and cancer. Pharmacol Rev 52:673–751 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi L, Singh RP, Lu Y, Agarwal R, Harrison GS, Franzusoff A, Glode LM (2003) Epidermal growth factor receptor mediates silibinin-induced cytotoxicity in a rat glioma cell line. Cancer Biol Ther 2:526–531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar FH, Li Y (2006) Using chemopreventive agents to enhance the efficacy of cancer therapy. Cancer Res 66:3347–3350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumann J, Prockl J, Kiemer AK, Vollmar AM, Bang R, Tiegs G (2003) Silibinin protects mice from T cell-dependent liver injury. J Hepatol 39:333–340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro GI, Harper JW (1999) Anticancer drug targets: cell cycle and checkpoint control. J Clin Invest 104:1645–1653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh RP, Agarwal R (2005). Mechanisms and preclinical efficacy of silibinin in preventing skin cancer. Eur J Cancer 41:1969–1979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh RP, Agarwal R (2006a) Natural flavonoids targeting deregulated cell cycle progression in cancer cells. Curr Drug Targets 7:345–354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh RP, Agarwal R (2006b) Prostate cancer chemoprevention by silibinin: bench to bedside. Mol Carcinog 45:436–442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh RP, Dhanalakshmi S, Agarwal C, Agarwal R (2005) Silibinin strongly inhibits growth and survival of human endothelial cells via cell cycle arrest and downregulation of survivin, Akt and NF-kappaB: implications for angioprevention and antiangiogenic therapy. Oncogene 24:1188–1202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh RP, Dhanalakshmi S, Mohan S, Agarwal C, Agarwal R (2006) Silibinin inhibits UVB- and epidermal growth factor-induced mitogenic and cell survival signaling involving activator protein-1 and nuclear factor-kappaB in mouse epidermal JB6 cells. Mol Cancer Ther 5:1145–1153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonnenbichler J, Zetl I (1986) Biochemical effects of the flavonolignane silibinin on RNA, protein and DNA synthesis in rat livers. Prog Clin Biol Res 213:319–331 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonnenbichler J, Goldberg M, Hane L, Madubunyi I, Vogl S, Zetl I (1986) Stimulatory effect of Silibinin on the DNA synthesis in partially hepatectomized rat livers: non-response in hepatoma and other malign cell lines. Biochem Pharmacol 35:538–541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonnenbichler J, Scalera F, Sonnenbichler I, Weyhenmeyer R (1999) Stimulatory effects of silibinin and silicristin from the milk thistle Silybum marianum on kidney cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 290:1375–1383 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundaresan S, Roberts PE, King KL, Sliwkowski MX, Mather JP (1998) Biological response to ErbB ligands in nontransformed cell lines correlates with a specific pattern of receptor expression. Endocrinology 139:4756–4764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyagi AK, Agarwal C, Chan DC, Agarwal R (2004) Synergistic anti-cancer effects of silibinin with conventional cytotoxic agents doxorubicin, cisplatin and carboplatin against human breast carcinoma MCF-7 and MDA-MB468 cells. Oncol Rep 11:493–499 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valenzuela A, Garrido A (1994) Biochemical bases of the pharmacological action of the flavonoid silymarin and of its structural isomer silibinin. Biol Res 27:105–112 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wellington K, Jarvis B (2001) Silymarin: a review of its clinical properties in the management of hepatic disorders. Biodrugs 15:465–489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilasrusmee C, Kittur S, Shah G, Siddiqui J, Bruch D, Wilasrusmee S, Kittur DS (2002) Immunostimulatory effect of Silybum marianum (milk thistle) extract. Med Sci Monit 8:BR439–BR443 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong X, Zhu Y, Lu Q, Zhang J, Ge Z, Zheng S (2006) Silymarin causes caspases activation and apoptosis in K562 leukemia cells through inactivation of Akt pathway. Toxicology 227:211–216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]