Abstract

Identification of the mechanisms leading to malignant transformation of respiratory cells may prove useful in the prevention and treatment of tobacco-related lung cancer. Nitrosamines 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone (NNK) and N′-nitrosonornicotine (NNN) can induce tumors both locally and systemically. In addition to the genotoxic effect, they have been shown to affect lung cells due to ligating the nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) expressed on the plasma membrane. In this study, we sought to establish the role for nAChRs in malignant transformation caused by NNK and NNN. We used the BEP2D cells that represent a suitable model for studying the various stages of human bronchial carcinogenesis. We found that these cells express α1, α3, α5, α7, α9, α10, β1, β2, and β4 nAChR subunits that can form high-affinity binding sites for NNK and NNN. Exposure of BEP2D cells to either NNK or NNN in both cases increased their proliferative potential which could be abolished in the presence of nAChR antagonists α-bungarotoxin, which worked most effectively against NNK, or mecamylamine, which was most efficient against NNN. The BEP2D cells stimulated with the nitrosamines showed multifold increases of the transcription of the PCNA and Bcl-2 genes by both real-time polymerase chain reaction and in-cell western assays. To gain a mechanistic insight into NNK- and NNN-initiated signaling, we investigated the expression of genes encoding the signal transduction effectors GATA-3, nuclear factor-κB, and STAT-1. Experimental results indicated that stimulation of nAChRs with NNK led to activation of all three signal transduction effectors under consideration, whereas NNN predominantly activated GATA-3 and STAT-1. The GATA-3 protein-binding activity induced by NNK and NNN correlated with elevated gene expression. The obtained results support the novel concept of receptor-mediated action of NNK and NNN placing cellular nAChRs in the center of the pathophysiologic loop, and suggest that an nAChR antagonist may serve as a chemopreventive agent.

Keywords: 4-(Methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone, N′-Nitrosonornicotine, Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors, BEP2D cells, Gene expression, GATA-3 activity, Apoptosis

Introduction

Identification of the mechanisms leading to malignant transformation of respiratory cells may prove useful in the prevention and treatment of lung cancer. The complex process of tobacco-induced tumorigenesis includes both carcinogenic and tumor-promoting effects of tobacco products (Niphadkar et al. 1994). Tobacco carcinogens and their DNA adducts are central to cancer induction by tobacco smoke (Wogan et al. 2004). The nitrosamines 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone (NNK) and N′-nitrosonornicotine (NNN) are strong carcinogens (Hecht 1998). They are formed from nicotine and related tobacco alkaloids by nitrosation during the processing of tobacco in the mammalian organism (Hecht and Hoffmann 1988). NNK and NNN are believed to be involved in cancers of the lung, esophagus, oral cavity, and pancreas (Hecht et al. 1993). The organ specificity of NNK for the lung is particularly noteworthy (Hecht and Hoffmann 1988). The pathobiologic effects of NNK and NNN were documented in cultures of normal human epithelial cells (Murrah et al. 1993). The cells exposed to the nitrosamines continued to divide, and displayed focal growth and morphologic changes suggestive of early stages in cell transformation. The BEP2D cell line—the papillomavirus-immortalized human bronchial epithelial cells (BEC) (Willey et al. 1991)—has been used to investigate the oncogenic potential of NNK (Zhou et al. 2003). Already after 24-h incubation, NNK induced the phenotypic changes consistent with oncogenic transformation including alteration in growth kinetics, increase in saturation density, resistance to serum-induced terminal differentiation, and anchorage-independent growth. Upon inoculation into nude mice, NNK-transformed cells produced tumors from which primary cell lines could be established.

Recent research has established a novel concept of carcinogenic action of NNK and NNN via the cholinergic receptors expressed in BEC, in addition to their well-known genotoxic effect (Minna 2003). The potential role of cholinergic activation in the development and growth of lung cancer has been intensely studied in recent years (reviewed in Racke and Matthiesen 2004). It has been demonstrated that acetylcholine (ACh) acts as an autocrine growth factor for lung cancers. Lung cancer cells synthesize and secrete ACh (Song et al. 2003a, b) and respond to ACh via the nicotinic and muscarinic classes of cholinergic receptors (Song et al. 2003a; Tarroni et al. 1992; Cunningham et al. 1985; Schuller et al. 2000; Schuller and Orloff 1998). Activation of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) stimulates the growth of lung cancer cells and suppresses apoptosis (Song et al. 2003a; West et al. 2003; Quik et al. 1994; Maneckjee and Minna 1990, 1994; Schuller et al. 1990, 2003; Cattaneo et al. 1997). There is growing evidence that in addition to the agonist nicotine, nAChRs also can be stimulated by NNK and NNN. Although the concentration of NNK in the mainstream smoke of cigarettes is on average 5,000–10,000 times smaller than that of nicotine (Hecht and Hoffmann 1988), the nitrosamines ligate nAChRs with a higher than nicotine affinity, and evoke an agonistic response upregulating the growth of pulmonary cells (Schuller et al. 2000, 2003; Schuller and Orloff 1998; Jull et al. 2001).

The nAChRs are classic representatives of the superfamily of ligand-gated ion channel proteins, or ionotropic receptors, mediating the influx of Na+ and Ca2+ and efflux of K+ (Steinbach 1990). Each of α7, α8, and α9 subunits is capable of forming homomeric nAChR channels. The heteromeric channels can be composed of α2, α3, α4, α5, α6, β2, β3, and β4 subunits, e.g., α3(β2/β4) ± α5, and α9 can form a heteromeric channel with α10 (Elgoyhen et al. 2001). Activation of nAChRs with nicotine stimulates MAPK activity in a concentration- and time-dependent manner via a Ca2+-dependent mechanism (Cattaneo et al. 1997) and also causes a marked upregulation and activation of Raf-1 while suppressing the growth inhibitory effect of trans-retinoic acid (Chen et al. 2002). The tumor-promoting effect of nAChRs involves activation of Bcl-2 (Mai et al. 2003). The growth-stimulatory effects of nAChRs are apparently balanced by muscarinic receptors, since muscarinic stimulation produces an inhibitory effect on lung cancer cell growth and cell cycle progression (Williams 2003; Williams and Lennon 1991). Selective stimulation of nAChRs may therefore skew a balance of the physiologic cell control through cholinergic pathways.

In this study, we sought to establish the role for nAChRs expressed BEP2D cells in their malignant transformation caused by the pharmacologic doses of tobacco-derived carcinogenic nitrosamines. We tested the hypothesis that functional inactivation of nAChRs can abolish the tumorigenic effects of NNK and NNN. We found that inhibition of binding of NNK and NNN to nAChRs in BEP2D cells abolished acquisition of the anchorage-independent growth ability of these cells, and growth-promoting effects of nitrosamines that involved activation of transcription factors. Competition with NNK and NNN at nAChRs also abrogated alterations in the gene expression in the exposed cells. The obtained results provide crucial information for identifying the role of specific nAChR subtypes in tobacco-related carcinogenesis and lung cancer chemoprevention.

Materials and methods

Nitrosamine exposure experiments

The BEP2D cells represent a suitable model for studying the various stages of human bronchial carcinogenesis. This cell line is an established clonal population of HPV-18-immortalized human BEC (Willey et al. 1991). The cells have an epithelial morphology in culture, near diploid karyotype, and relatively stable genotype. They are anchorage-dependent and do not form tumors in immunosuppressed host animals. The cell line used in this study was a generous gift from Dr Harris (NCI, NIH). Prior to use in experiments, the BEP2D cells were propagated in the Cambrex brand bronchial cell medium without retinoic acid (Cambrex Bio Sciences, Walkersville, MD, USA). At ∼80% confluence, the BEP2D cells were exposed for 24 h to 1 μM of NNK (Toronto Research Chemicals, North York, ON, Canada) or NNN (Eagle Picher Technologies, Lenexa, KS, USA) either given alone or in combination with one of the nicotinic antagonists, 1 μM α-bungarotoxin (αBtx)—the specific inhibitor of the central subtype of the neuronal nAChRs, such as α7 (Conti-Tronconi et al. 1994), or 50 μM mecamylamine (Mec)—a preferential blocker of the ganglionic nAChR subtypes, such as α3- or α4-made nAChRs (Grando et al. 1995). Both antagonists were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Corporation (St Louis, MO, USA). The control cultures were left untreated. For cell culture experiments, the stock solutions of NNK and NNN (100 mg/ml in dimethyl sulfoxide) were diluted in the culture medium. After incubation, the cells were washed thrice with prewarmed PBS, and: (1) subcultured for additional four passages with subsequent evaluation of the cell state and growth kinetics studies; (2) replated into soft agar plates for the studies of anchorage-independent growth; (3) used for RNA extraction and real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) experiments; or (4) used for nuclear extraction and gel mobility shift assay (see below).

Characterization of nAChRs expressed in BEP2D cells

The profile of nAChR subunits expressed in BRP2D cells was determined in a standard reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) assay using primer sets for human α1–α7, α9, α10, and β1–β4 nAChR subunits and amplification conditions shown in Table 1. Normal human muscle and brain PCR ready first strand cDNA were purchased from BioChain Institute Inc. (Hayward, CA, USA) for testing all primers (data not shown). The BEP2D cell lysate was used to probe at the protein level the presence of the nAChR subunits detected by RT-PCR. The standard immunoblotting assay used in this study was detailed elsewhere (Nguyen et al. 2000a). The antibodies to α1 (dilution 1:10,000) and β1 (1:15,000) subunits were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Corporation (St Louis, MO, USA); the antibodies to α3 (1:800), α5 (1:800), α7 (1:800), β2 (1:400), and β4 (1:400) were from Research and Diagnostic Antibodies (Las Vegas, NV, USA); and the antibodies to α9 (1:200) and α10 (1:400) were raised and characterized in our previous studies (Nguyen et al. 2000b; Arredondo et al. 2002).

Table 1.

Primers used for RT-PCR analysis of nAChR expression in BEP2D cells

| Target mRNA | Forward/reverse primers | Product size, bpa | Anneal temperature | Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| α1 | CGT TCT GGT GGC AAA GCT / CCG CTC TCC ATG AAG TT | 580/505b | 55 | Maus et al. (1998) |

| α2 | GGA GCT CTG CCA CCC CCT AC / AAC ATA CTT CCA GTCC TC | 327 | 64 | Kurzen et al. (2004) |

| α3 | AGG CCA ACA AGC AAC GAG / TTG CAG AAA CAA TCC TGC TG | 419 | 64 | Kurzen et al. (2004) |

| α4 | GCT TCT CCC TGG ACT CTG TG / AGG GGA GAG CTG GAC TTA GC | 218 | 60 | Kurzen et al. (2004) |

| α5 | TCA ACA CAT AAT GCC ATG GC / CCT CAC GGA CAT CAT TTT CC | 219 | 64 | Kurzen et al. (2004) |

| α6 | AGG CTC TGA TGC AGT GCC CA / AAT TAT AAA TAC CCA AAGA | 324 | 64 | Kurzen et al. (2004) |

| α7 | CTT CAC CAT CAT CTG CAC CAT C / GGT ACG GAT GTG CCA AGG ATA T | 308 | 55 | Kurzen et al. (2004) |

| α9 | ATC CTG AAA TAC ATG TCC AGG G / AAT CGG TCT ATG ACT TTC GCC | 352 | 64 | Kurzen et al. (2004) |

| α10 | CTC TCA AGC TGT TCC GTG ACC / AAG GCT GCT ACA TCC ACG C | 394 | 64 | Sgard et al. (2002) |

| β1 | CTA CGA CAG CTC GGA GGT CA / GCA GGT TGA GAA CCA CGA CA | 479 | 58 | Carlisle et al. (2004) |

| β2 | GCT CTT CAT GCA GCA GCC ACG CC / TCA CTC ACG CTC TGG TCA TC | 308 | 64 | Kurzen et al. (2004) |

| β3 | ATG TGG ATC GCT ACT ACT C / GAT GTC AGG TCT AAG GTG TA | 367 | 64 | Kurzen et al. (2004) |

| β4 | TGT GAG CAT TGG CCA TCA AC / AAT GCC AAG CCT CTG AGC TG | 313 | 55 | Kurzen et al. (2004) |

| PDHc | GGT ATG GAT GAG GAG CTG GA / CTT CCA CAG CCC TCG ACT AA | 101/200 | 55 | Kurzen et al. (2004) |

aAll products were sequenced by the designers of the PCR primer used in this study

bα1 Primers yield two products due to the presence of two α1 isoforms in adult human muscle (adapted from Beeson et al. 1990)

cPDH (pyruvate dehydrogenase; GeneBank accession number XM_113395) primers yield fragments of 101 bp in the presence of cDNA and fragments of 200 bp in the presence of genomic DNA

Cell state and growth kinetics assays

Cell number was computed using a hemocytometer, and the percentage of dead cells was determined based on trypan blue dye (TBD) positivity. To induce programmed cell death, we used an established model of reactive oxygen species-mediated apoptosis, which in BEC involves H2O2-dependent activation of the Fas–FasL pathway (Fujita et al. 2002). The nitrosamine-treated and control BEP2D monolayers were preincubated with 100 μM H2O2 in culture medium for 12 h. The BEP2D cells undergoing apoptosis were visualized using the DeadEnd™ Fluorometric TUNEL (i.e., the terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP-biotin nick end-labeling) System purchased from Promega (Madison, WI, USA). The enzymatic activity of pro-apoptotic caspase 3 was determined using the fluorometric assay kit (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA, USA) and following a protocol provided by the manufacturer.

Assay of anchorage-independent growth

Anchorage-independent growth was studied using a soft agar assay, as described elsewhere (Grando et al. 1996). Briefly, a 5% solution of Difco brand agar noble (BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) was diluted 1/10 in culture medium, poured into a 35-mm Petri dish, and allowed to solidify (base layer). BEP2D cells were trypsinized, suspended in 0.5% agar in culture medium (3×103 cells/ml), laid over the surface of the solidified base, and cultured in a humid 5% CO2 incubator. After 6 weeks, colonies with more than 50 cells were scored with the aid of an inverted microscope.

Real-time PCR

Total RNA was extracted from BEP2D cells at the end of exposure experiments using the guanidinium thiocyanate–phenol–chloroform extraction procedure and used in the real-time PCR experiments, as detailed elsewhere (Arredondo et al. 2005a). The following forward/reverse primers for the genes encoding human PCNA (i.e., proliferating cell nuclear antigen), Bcl-2, and the transcription factors nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB), GATA-3, STAT-1, and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) were designed with the assistance of the Primer Express software version 2.0 computer program (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) and the service Assays-on-Design provided by Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA, USA): 5-GTCACAGACAAGTAATGTCGA-3/5-GTTGAAGAGAGTGGAGTGGC-3 for PCNA (product size 125 bp), 5-TTTTTCTCCTTCGGCGGG-3/5-GGTGGTCATTCAGGTAAGTGGC-3 for Bcl-2 (105 bp), 5-TCCGTTATGTATGTGAAGGC-3/5-TTTGCTGGTCCCACATAGTTGC-3 for NF-κB (111 bp), 5-GGGCTCTATCACAAAATGAACG-3/5-TTGTGGTGGTCTGACAGTTCGC-3 for GATA-3 (111 bp), 5-GAACCCAGGAATCTGTCC-3/5-TCCACATTGAGACCTCTTTTGG-3 for STAT-1 (112 bp), and 5-TTTGGCTACAGCAACAGGGTGG-3/5-TCTCTTCCTCTTGTGCTCTTGC-3 for GAPDH (100 bp). All PCR reactions were performed using an ABI Prism 7500 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) and the SYBR® Green PCR Core Reagents kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) in accordance to the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, 22.5 μl of diluted cDNA sample produced from 1 μg of total RNA was added to 25 μl of the PCR master-mix and 2.5 μl 20× Assays-on-Demand Gene Expression Mix. The data from triplicate samples were analyzed with sequence detector software (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) and expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) of mRNA in question relative to that of GAPDH.

In-cell western

The effects on NNK and NNN on gene expression at the protein level were also determined using the LI-COR’s in-cell western assay (LI-COR, Lincoln, NE, USA), as described in detail elsewhere (Arredondo et al. 2005b). Briefly, the BEP2D were seeded in the 96 well plates at a cell density of 5×105/well, incubated overnight to allow adherence to the dish bottom, and exposed to the nitrosamines ± antagonists as described above. After exposure, the cells were fixed, washed, permeabilized with Triton solution, incubated with the LI-COR Odyssey Blocking Buffer (Lincoln, NE, USA), and exposed for 2 h to a primary antibody to PCNA (Oncogene Research products, Boston, MA, USA), Bcl-2 (Oncogene Research products, Boston, MA, USA), NF-κB (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA), GATA-3 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA), or STAT-1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA). After that, the cells were washed, stained with a secondary goat anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor®680 (1:10,000 dilution; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA) and/or goat anti-mouse IRDye™ 800CW (1:10,000 dilution; Rockland Immunochemicals, Gilbertsville, PA, USA) antibody. The protein expression was then quantitated using the Odyssey Imaging System (LI-COR, Lincoln, NE, USA).

Gel mobility shift assay

In accordance with established protocol (Abravaya et al. 1992), the nuclear extract was obtained from treated and control BEP2D cells grown in 6 well plates. The cells were released from the dish bottom by trypsinization, resuspended in cold (4°C) TBS (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA), pelleted by centrifugation, and lyzed with 10% NP-40/400 μl buffer A [10 mM Na-HEPES (pH 7.9), 10 mM KCl, 0.1 mM EDTA (pH 8.0), 0.1 mM EGTA (pH 8.0), 1 mM DTT, and 0.5 mM PMSF]. The nuclei were pelleted by centrifugation, and resuspended in buffer B [20 mM Na-HEPES (pH 7.9), 400 mM KCl, 1 mM EDTA (pH 8.0), 1 mM EGTA (pH 8.0), 1 mM DTT, 0.5 mM PMSF, and 10% glycerol]. The gel mobility shift assay was performed as described in detail elsewhere (Sistonen et al. 1994). Briefly, the oligonucleotide 5′-CACTTGATAACAGAAAGTGATAACTCT-3 (for GATA-3) supplied by the Operon (Alameda, CA, USA) was labeled with Digoxigenin and its complement. The gel shift reaction buffer consisted of 10 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 1 mM EDTA, and 5% glycerol. Nuclear extracts containing 10 μg of protein were incubated with 0.5 ng of Digoxigenin-labeled GATA-3 oligonucleotide and 1 μg poly dI-dC for 20 min at room temperature in gel shift reaction buffer. The DNA–protein complexes were resolved by electrophoresis through a 5% polyacrylamide gel containing 0.5× Tris, boric acid, EDTA and blotted overnight at 4°C in 1× sodium chloride/sodium citrate buffer onto the Positive Charge Nylon Membranes, followed by UV cross linking, and Digoxigenin detection with anti-Digoxigenin-AP monoclonal antibody and NBT/BCIP Nitro blue tetrazolium/5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate toluidine salt as a substrate (all from Roche, Indianapolis, IN, USA).

Radioligand binding inhibition assay

Binding of NNK and NNN to nAChRs expressed in BEP2D cells was investigated in radioligand binding inhibition experiments. The cells were seeded into 24-well culture plates (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) at a density of 1×105 cells per well, incubated overnight in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37°C to allow the cells to settle and attach to the dish bottom. All experiments were performed in a 200-μl final volume as detailed elsewhere (Grando 2003). Briefly, triplicate monolayers were incubated for 1 h at 4°C in the presence of a saturating concentration of either radioligand (—)[N-methyl-3H]nicotine (specific activity 84.0 Ci/mmol) or [3H]epibatidine (54.0 Ci/mmol; both from Amersham Pharmacia Biotech Inc.) plus log dilutions of NNK or NNN. After incubation, the monolayers were washed with ice-cold phosphate buffered saline and solubilized with 1% SDS. The radioactivity was counted in a liquid scintillation counter. The results were normalized by the non-specific binding obtained in the presence of excess of “cold” nicotine or epibatidine.

Statistical analysis

All experiments were performed in triplicates, or quadruplicates, and the results were expressed as mean ± SD. Statistical significance was determined using Student’s t-test. Differences were deemed significant if the calculated P value was <0.05.

Results

The nAChR subunits expressed in BEP2D cells

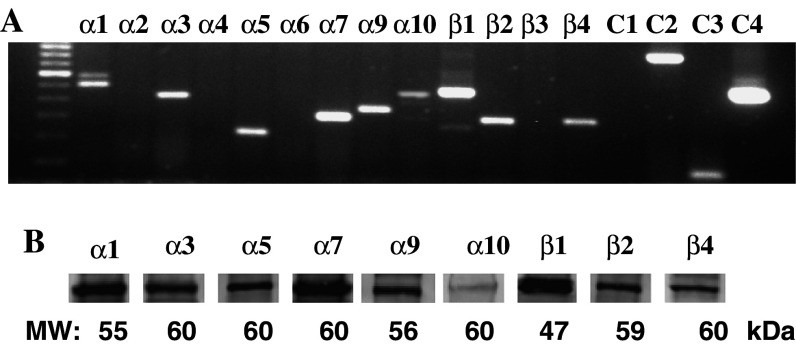

The RT-PCR experiments using previously characterized human nAChR subunit gene-specific primers and the BEP2D cells grown to ∼80% confluence revealed the expression of α1, α3, α5, α7, α9, α10, β1, β2, and β4 nAChR subunits (Fig. 1). The products were not amplified from putative contaminating DNA. Therefore, in addition to the muscle-type nAChR subunits α1 and β1 previously demonstrated in BEC lines (Carlisle et al. 2004), the heteromeric nAChR channels in BEP2D cells can be comprised by α3, α5, β2, and β4 subunits, i.e., α3(β2/β4) ± α5, or α9α10, and the homomeric channels can be composed of several α7 or α9 subunits.

Fig. 1.

RT-PCR analysis of nAChR subunit expression in BEP2D cells. The cells were grown to ∼80% confluence and used for total RNA extraction. The RT-PCR was performed as described in Sect. ”Materials and methods” using primer pairs and annealing temperature indicated in Table 1. Left lane is a 100-bp molecular weight ladder. C1 is negative control (no cDNA). C2 is β-actin used as a positive control for RNA integrity. The 838-bp product was visualized using primers purchased from BioChain Institute Inc. (Hayward, CA, USA). Amplification of PDH (C3) yielded only a single band of 101 bp, confirming the absence of genomic DNA. C4 is a 500-bp product obtained with control primers provided within First-Strand cDNA Synthesis System (Invitrogen Corporation, Carlsbad, CA, USA) to verify performance of first-strand synthesis

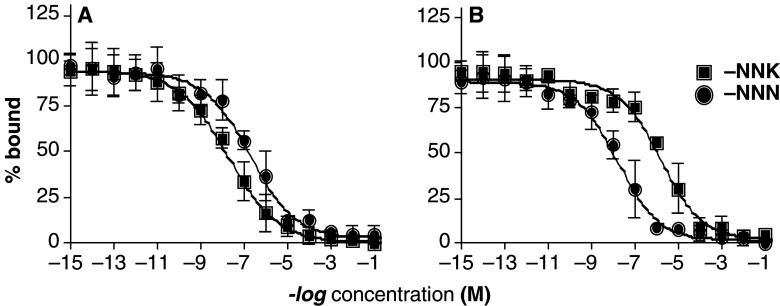

Competitive binding of NNK and NNN to BEP2D cells

To investigate a possibility that NNK and NNN can specifically bind to the nAChRs expressed on the plasma membrane of BEP2D cells, we performed the radioligand binding inhibition experiments using the nicotinic radioligands [3H]nicotine and [3H]epibatidine, and BEP2D monolayers in 24 well plates. Both NNK and NNN competed with the nicotinic radioligands. NNK showed a higher than NNN affinity to the [3H]nicotine-labeled binding sites, with the EC50 values of 23.1 and 230 nM, respectively (Fig. 2a). In contrast, compared to NNK, NNN had a higher affinity to the [3H]epibatidine-sensitive nAChRs, as judged from the EC50 values of 1.9 μM and 19.4 nM, respectively (Fig. 2b). These results clearly demonstrated the presence in BEP2D cells of the high-affinity binding sites for NNK, and NNN. Since nicotine can ligate both the “ganglionic” (i.e., α2-, α3-, or α4-made) and the “central” (i.e., α7-made) nAChRs, while epibatidine is selective for the ganglionic nAChRs subtypes (Cauley et al. 1996; Zhao et al. 2003; Lindstrom et al. 1995; Gerzanich et al. 1995), the obtained results indicated that in BEP2D cells NNK preferentially binds to the α7, whereas NNN—to the α3 nAChRs.

Fig. 2.

Displacement curves of NNK and NNN with [3H]nicotine (a) and [3H]epibatidine (b). The numbers on the ordinate indicate the log molarity of the NNK, and NNN solutions used in the radioligand binding inhibition assays with the monolayers of BEP2D cells, as described in the Sect. ”Materials and methods”. The EC50 values reported in the Sect. ”Results” were determined from the displacement curves

Endpoint effects of exposures of BEP2D cell cultures to nitrosamines

Exposure of BEP2D cells to either NNK or NNN in both cases increased their proliferative potential (Table 2). An increase in cell numbers was abolished if the cells were exposed to nitrosamines in the presence of nAChR antagonists. αBtx worked most efficiently against NNK and Mec—against NNN, which is in keeping with a supposition that NNK acts preferentially through α7 nAChR and NNN through non-α7 nAChR(s). Both NNK and NNN produced an anti-apoptotic effect, which was alleviated by antagonists. The antagonists, however, did not decrease the number of TBD+ cells elevated due to incubation with the nitrosamines.

Table 2.

Functional analysis of the endpoint effects of NNK and NNN on BEP2D cells

| Parameters | Experimental conditions | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Untreated controls | NNK | NNK + αBtx | NNK + Mec | NNN | NNN + αBtx | NNN + Mec | |

| Cell number (1×104) | 37.8±5.9 | 133.9±4.2* | 40±3.3# | 91.1±7.5*# | 109.4±6.7* | 78.9±13.4*# | 33.9±10.1# |

| Percent of TBD+ cells | 4.5±0.7 | 5.0±1.0 | 5.1±1.9 | 4.6±0.2 | 4.9±1.2 | 4.7±0.8 | 5.3±1.7 |

| Number of TUNEL+ cells | 5.3±0.9 | 3.9±0.4 | 5.8±0.5# | 4.8±1.4 | 3.9±0.8 | 4.2±0.5 | 6.0±0.6# |

| Caspase 3 activity (RFU) | 698±112 | 614±110 | 645±145 | 689±205 | 564±145 | 619±35 | 690±42 |

| Colonies in soft agar | 0 | 16.3±3.2 | 2.7±1.2# | 11±2.2 | 9.6±2.8 | 7.8±1.8 | 2.4±1.2# |

*P<0.05, the rest are P>0.05, compared to untreated controls

# P<0.05 compared to the same nitrosamine given alone

Effects on anchorage-independent growth of BEP2D cells

Plating into soft agar of single cell suspensions of non-treated BEP2D cells did not produce any colonies containing >50 cells after 6 weeks of incubation, which is consistent with a previous report by Zhou et al. (2003). In marked contrast, treatment with either NNK or NNN led to formation of expanding cell colonies producing cell clumps, or plaques. From 7 to 21 colonies were found in each dish (Table 2). Pharmacologic blockade of nAChRs with either αBtx or Mec in both cases diminished the number of colonies, with αBtx being particularly efficient in abolishing the effect of NNK and Mec—that of NNN (Table 2). These observations suggested that the oncogenic potential of tobacco-derived nitrosamines can be alleviated by blocking cellular nAChR subtypes.

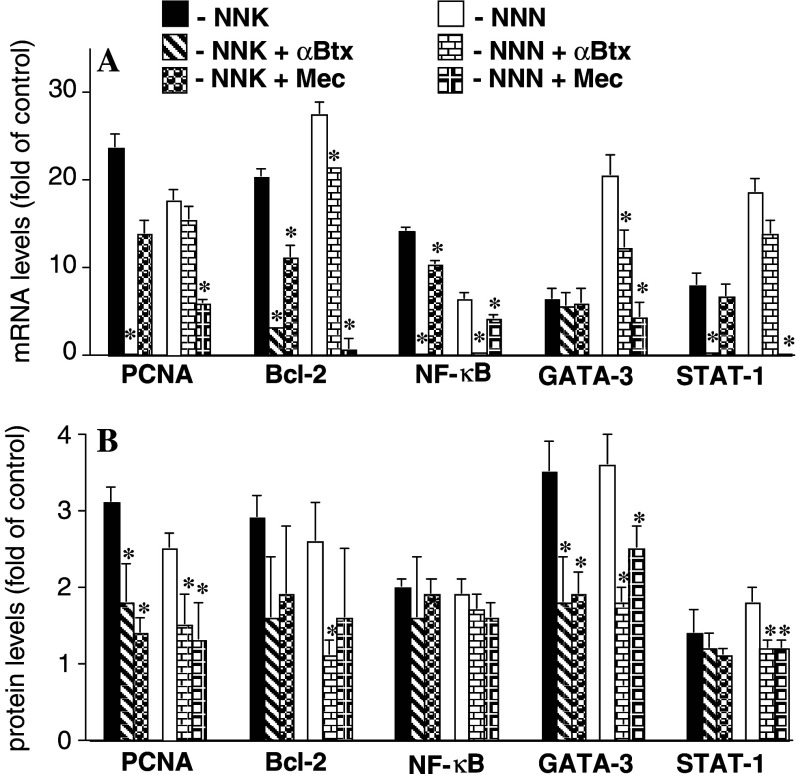

Alterations in the expression of cell state marker genes

To elucidate the biologic mechanism involved in the receptor-mediated action of NNK and NNN on BEP2D cells, we studied transcription of the genes encoding the cell cycle and apoptosis genes in exposed vs. control, unexposed cell cultures using real-time PCR, and in-cell western assays. Both assays brought similar results (Fig. 3). The BEP2D cells stimulated with either NNK or NNN showed multifold increases of the transcription of the PCNA and Bcl-2 genes. The effect of NNK was chiefly blocked by αBtx and that of NNN by Mec. Thus, in addition to stimulated proliferation, an increase in numbers of nitrosamine-treated cells (Table 2) may also reflect an anti-apoptotic effect, which would be consistent with previous reports that activation of α7 produces anti-apoptotic action (Garrido et al. 2001) and that nicotinic regulation of apoptosis involves upregulation of Bcl-2 (Sun et al. 2004).

Fig. 3.

Quantitative analysis of the effects of NNK and NNN on gene expression in BEP2D cells. BEP2D cells were incubated for 24 h in culture medium without any additions (control) or in the presence of 1 μM of NNK or NNN with or without the antagonists αBtx, 1 μM, or Mec, 50 μM. The alterations in gene expression are presented relative to the rates of expression of corresponding genes in control samples, taken as 1. *P<0.05 compared to the same nitrosamine given alone. a. Real-time PCR analysis. b In-cell western analysis

Elevation of transcription factors

To gain a mechanistic insight into NNK- and NNN-initiated signaling in BEP2D cells, we investigated the expression of genes encoding the signal transduction effectors GATA-3, NF-κB, and STAT-1. We selected these genes based on the results showing their high sensitivity to cell exposures to tobacco products (Arredondo et al. 2005a). Both nitrosamines elevated the gene expression of the transcription factors in BEP2D cells, which could be abolished by αBtx and Mec with different efficacies (Fig. 3). The use of antagonists suggested that stimulation of nAChRs with NNK led to activation of all three signal transduction effectors under consideration, whereas NNN predominantly activated GATA-3 and STAT-1 (Fig. 3). This is in keeping with the facts that, on the one hand, NNK binding to α7 activates Raf-1 (Schuller and Orloff 1998) and that the Ras/Raf-1/ERK pathway mediates NF-κB activation in human bronchial cells (Chen et al. 2004), on the other.

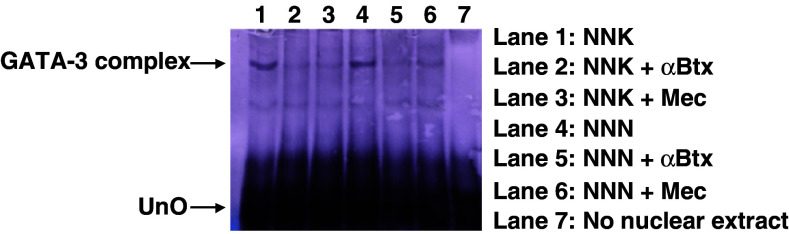

Upregulation of GATA-3 activity

To determine whether the NNK and NNK-induced alterations in gene expression were correlated with an increased activity of the transcriptional factors, we selected GATA-3 for the gel mobility shift assay (Fig. 4). This assay identifies the interaction of proteins with DNA, which is central to the control of many cellular processes including DNA replication, recombination, and transcription. We found that the GATA-3 protein-binding activity induced by NNK and NNN correlated with the transcriptional induction observed in the quantitative assays (Fig. 3), and could be abolished by nAChR antagonists (Fig. 4). Thus, stimulation of GATA-3 could be mediated via an intracellular signaling downstream from both α7 and non-α7 nAChR, such as α3β2 (Arredondo et al. 2005a), activated by tobacco-derived nitrosamines.

Fig. 4.

Assessment of nitrosamine effects on GATA-3 activity using electrophoretic mobility shift assay. The GATA-3 DNA–protein complex (marked GATA-3 complex) was detected by gel mobility shift assay with nuclear extracts prepared from BEP2D cells that were either untreated, or treated with NNK or NNN in the presence or absence of antagonists as described in the legend to Fig. 3. UnO denotes unbound oligonucleotide

Discussion

The results of this study demonstrated that (1) BEP2D cells respond to NNK and NNN predominantly through the α7 and non-α7 nAChR subtypes, respectively; (2) at their pharmacologic doses, both NNK and NNN can stimulate proliferation, inhibit apoptosis, and induce anchorage-independent growth of BEP2D cells; and (3) changes in the cell state and gene expression induced by both nitrosamines correlate with activation of transcription effectors, such as GATA-3 and STAT-1, whereas NNN also upregulates NF-κB. These findings suggest that the nAChR-mediated mechanisms of nitrosamine action play an important role in tobacco-related malignant transformation of pulmonary cells.

The existence of a cholinergic autocrine loop in lung cells provides a basis for understanding the carcinogenic effects of nicotine and its derivatives, and identification of new targets for potential therapeutic intervention. The respiratory epithelium expresses the cholinergic enzymes that regulate levels of free ACh in lung tissue as well as the vesicular ACh transporter and the choline high-affinity transporter (Proskocil et al. 2004; Taisne et al. 1997; Koga et al. 1992; Ohrui et al. 1991). We first demonstrated that normal human BEC express α3, α4, α5, and α7 subunits that form channels modulating Ca2+ metabolism and regulating cell adhesion and motility (Zia et al. 1997). These findings were confirmed in other laboratories. Maus et al. (1998) showed the presence of mRNA transcripts for α3, α5, β2, and β4 and the ability of nicotinic antagonists blocking α3 nAChR to cause reversible changes of cell shape in cultures of human BEC. Wang et al. (2001) confirmed the presence α7 subunit through RT-PCR and in situ hybridization, and demonstrated by patch-clamping that this subunit forms functional nAChRs. Proskocil et al. (2004) provided evidence for the presence of α4 nAChR in BEC. Saturable nicotinic binding sites in BEC were also reported by Shriver et al. (2000). Recently, West et al. (2003) reported that BEC derived from large airways, which are the precursor cells for squamous cell carcinomas, and small airway epithelial cells (SAEC), which are the precursor cells for adenocarcinomas, have slightly different repertoires of nAChRs. BEC selectively express α3 and α5 subunits, whereas SAEC selectively express α2 and α4 subunits, and both cell types express α7–α10, β2, and β4 subunits (West et al. 2003). Most recently, Carlisle et al. (2004) demonstrated the muscle-type nAChR subunits in several BEC lines. The results obtained in the present study indicate that in addition to the muscle-type nAChR, both α7 and non-α7 nAChRs, such as α3(β2/β4) ± α5, α9, and α9α10 channels, can mediate pathobiologic effects of nicotine derivatives on BEP2D cells. These findings are consistent, in the most part, with the results of other studies with human or rodents BEC. Minor discrepancies, such as lack of α2 and α4 in BEP2D cells, may be secondary to alterations in the gene expression due to immortalization and/or the specific culture conditions used.

Our findings indicate that acting via nAChRs, nitrosamines stimulated proliferation and inhibited apoptosis of BEP2D cells, which is in keeping with observations reported by Schuller and Orloff (1998). When alterations of gene expression in lung of mice exposed to environmental tobacco smoke were studied using DNA microarray, the exposure produced significant changes in 24 genes, including the cell receptor, signal transduction, cell cycle regulation, apoptosis, stress response, oxidative stress, xenobiotic metabolism, and protein repair, removal and folding genes (Izzotti et al. 2004). When we (Arredondo et al. 2001, 2003, 2005a) and others (Dunckley and Lukas 2003) studied the effects of nAChR inactivation by antagonists or gene silencing on tobacco smoke- and/or nicotine-dependent modulation of gene expression, most alterations could be abolished due to inactivation of specific nAChR subtypes. Likewise, the effects of both nitrosamines on the BEP2D cells state and growth kinetics could be abolished by αBtx and Mec with various efficacies. In contrast, the cytotoxic effect of NNK and NNN manifested by an increase of TBD positive cells, which did not involve the apoptotic pathways, was not mediated by nAChRs. A process of cell death distinct from apoptosis, such as oncosis, could lead to the cell membrane disruption manifested by TBD positivity (Trump et al. 1997; Majno and Joris 1995). Thus, results of this study indicate that pulmonary nAChRs may provide a novel molecular target to prevent, reverse, or retard oncogenic transformation of lung cells using receptor antagonists.

Stimulation of nAChRs expressed in BEP2D cells activated the transcription factor GATA-3 that correlated with altered gene expression. The signaling mechanism(s) mediating nitrosamine effects downstream of nAChR are not yet fully understood. We have recently demonstrated that Ras/Raf-1/MEK1/ERK signaling pathway coupled by α7 nAChR mediates some pathobiologic effects of nicotine and tobacco products (Arredondo et al. 2006) as well as cholinergic regulation of integrin expression and chemotaxis in keratinocytes (Chernyavsky et al. 2005). NNK binding to α7 can activate Akt, resulting in the phosphorylation of several downstream substrates (West et al. 2003). This is associated with appearance of the transformed cellular phenotype manifested as loss of contact inhibition, loss of dependence on exogenous growth factors, and attenuated apoptosis induced by various pro-apoptotic stimuli. Akt activation was documented in NNK-treated A/J mice and in human lung cancers from smokers (West et al. 2003). Additionally, NNK promotes functional cooperation of Bcl-2 and c-myc through phosphorylation (Jin et al. 2004).

The differences in relative changes of the mRNA and protein levels of the same molecule may be attributed to known differences in their half-lives, stability, etc. (Sonenberg et al. 2000). Some genes may transcribe low levels of mRNA and translate high levels of protein. The gene expression is not necessarily an automatic process once it has begun. It could be modified at any one of several sequential steps (Ptashne 1988; Brown 1984).

In conclusion, the results of this study further support the novel concept of receptor-mediated action of NNK and NNN placing cellular nAChRs in the center of the pathophysiologic loop. Our findings help elucidate the receptor-mediated mechanism of the initiation and progression of NNK- and NNN-induced lung cancers, which could guide further studies on the molecular mechanisms of action of nitrosamine carcinogenesis. Future in vivo studies should establish contribution of specific nAChR subtypes to mediating the oncogenic action of tobacco-derived nitrosamines and also identify the receptor antagonist that can serve as a chemopreventive agent.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the NIH grants CA117327 and DE14173, and a research grant from Flight Attendant Medical Research Institute to S.A.G.

Abbreviations

- ACh

Acetylcholine

- BEC

Bronchial epithelial cells

- αBtx

α-Bungarotoxin

- GAPDH

Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- Mec

Mecamylamine

- nAChRs

Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors

- NNK

4-(Methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone

- NNN

N′-Nitrosonornicotine

- RT-PCR

Reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction

- SAEC

Small airway epithelial cells

- TBD

Trypan blue dye

Footnotes

Juan Arredondo and Alex I. Chernyavsky contributed to this paper equally. Their names are listed in alphabetical order.

References

- Abravaya K, Myers MP, Murphy SP, Morimoto RI (1992) The human heat shock protein hsp70 interacts with HSF, the transcription factor that regulates heat shock gene expression. Genes Dev 6:1153–1164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arredondo J, Nguyen VT, Chernyavsky AI, Jolkovsky DL, Pinkerton KE, Grando SA (2001) A receptor-mediated mechanism of nicotine toxicity in oral keratinocytes. Lab Invest 81:1653–1668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arredondo J, Nguyen VT, Chernyavsky AI, Bercovich D, Orr-Urtreger A, Kummer W, Lips K, Vetter DE, Grando SA (2002) Central role of α7 nicotinic receptor in differentiation of the stratified squamous epithelium. J Cell Biol 159:325–336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arredondo J, Hall LH, Ndoye A, Nguyen VT, Chernyavsky AI, Bercovich D, Orr-Urtreger A, Beaudet AL, Grando SA (2003) Central role of fibroblast α3 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor in mediating cutaneous effects of nicotine. Lab Invest 83:207–225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arredondo J, Chernyavsky AI, Marubio LM, Beaudet AL, Jolkovsky DL, Pinkerton KE, Grando SA (2005a) Receptor-mediated tobacco toxicity: regulation of gene expression through α3β2 nicotinic receptor in oral epithelial cells. Am J Pathol 166:597–613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arredondo J, Chernyavsky AI, Webber RJ, Grando SA (2005b) Biological effects of SLURP-1 on human keratinocytes. J Invest Dermatol 125:1236–1241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arredondo J, Chernyavsky AI, Pinkerton KE, Jolkovsky DL, Grando SA (2006) Receptor-mediated tobacco toxicity: cooperation of the Ras/Raf-1/MEK1/ERK and JAK-2/STAT-3 pathways downstream of α7 nicotinic receptor in oral keratinocytes. FASEB J (in press) [DOI] [PubMed]

- Beeson D, Morris A, Vincent A, Newsom-Davis J (1990) The human muscle nicotinic acetylcholine receptor alpha-subunit exist as two isoforms: a novel exon. EMBO J 9:2101–2106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown DD (1984) The role of stable complexes that repress and activate eukaryotic genes. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 307:297–299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlisle DL, Hopkins TM, Gaither-Davis A, Silhanek MJ, Luketich JD, Christie NA, Siegfried JM (2004) Nicotine signals through muscle-type and neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in both human bronchial epithelial cells and airway fibroblasts. Respir Res 5:27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cattaneo MG, D’Atri F, Vicentini LM (1997) Mechanisms of mitogen-activated protein kinase activation by nicotine in small-cell lung carcinoma cells. Biochem J 328(Pt 2):499–503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cauley K, Marks M, Gahring LC, Rogers SW (1996) Nicotinic receptor subunits α3, α4, and β2 and high affinity nicotine binding sites are expressed by P19 embryonal cells. J Neurobiol 30:303–314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen GQ, Lin B, Dawson MI, Zhang XK (2002) Nicotine modulates the effects of retinoids on growth inhibition and RAR beta expression in lung cancer cells. Int J Cancer 99:171–178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen BC, Yu CC, Lei HC, Chang MS, Hsu MJ, Huang CL, Chen MC, Sheu JR, Chen TF, Chen TL, Inoue H, Lin CH (2004) Bradykinin B2 receptor mediates NF-kappaB activation and cyclooxygenase-2 expression via the Ras/Raf-1/ERK pathway in human airway epithelial cells. J Immunol 173:5219–5228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chernyavsky AI, Arredondo J, Karlsson E, Wessler I, Grando SA (2005) The Ras/Raf-1/MEK1/ERK signaling pathway coupled to integrin expression mediates cholinergic regulation of keratinocyte directional migration. J Biol Chem 280:39220–39228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conti-Tronconi BM, McLane KE, Raftery MA, Grando SA, Protti MP (1994) The nicotinic acetylcholine receptor: structure and autoimmune pathology. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol 29:69–123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham JM, Lennon VA, Lambert EH, Scheithauer B (1985) Acetylcholine receptors in small cell carcinomas. J Neurochem 45:159–167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunckley T, Lukas RJ (2003) Nicotine modulates the expression of a diverse set of genes in the neuronal SH-SY5Y cell line. J Biol Chem 278:15633–15640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elgoyhen AB, Vetter DE, Katz E, Rothlin CV, Heinemann SF, Boulter J (2001) α10: a determinant of nicotinic cholinergic receptor function in mammalian vestibular and cochlear mechanosensory hair cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98:3501–3506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita T, Maruyama M, Araya J, Sassa K, Kawagishi Y, Hayashi R, Matsui S, Kashii T, Yamashita N, Sugiyama E, Kobayashi M (2002) Hydrogen peroxide induces upregulation of Fas in human airway epithelial cells via the activation of PARP-p53 pathway. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 27:542–552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrido R, Mattson MP, Hennig B, Toborek M (2001) Nicotine protects against arachidonic-acid-induced caspase activation, cytochrome c release and apoptosis of cultured spinal cord neurons. J Neurochem 76:1395–1403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerzanich V, Peng X, Wang F, Wells G, Anand R, Fletcher S, Lindstrom J (1995) Comparative pharmacology of epibatidine: a potent agonist for neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Mol Pharmacol 48:774–782 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grando SA (2003) Mucocutaneous cholinergic system is targeted in mustard-induced vesication. Life Sci 72:2135–2144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grando SA, Horton RM, Pereira EFR, Diethelm-Okita BM, George PM, Albuquerque EX, Conti-Fine BM (1995) A nicotinic acetylcholine receptor regulating cell adhesion and motility is expressed in human keratinocytes. J Invest Dermatol 105:774–781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grando SA, Schofield OMV, Skubitz APN, Kist DA, Zelickson BD, Zachary CB (1996) Nodular basal cell carcinoma in vivo vs in vitro: establishment of pure cell cultures, cytomorphologic characteristics, ultrastructure, immunophenotype, biosynthetic activities, and generation of antisera. Arch Dermatol 132:1185–1193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hecht SS (1998) Biochemistry, biology, and carcinogenicity of tobacco-specific N-nitrosamines. Chem Res Toxicol 11:559–603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hecht SS, Hoffmann D (1988) Tobacco-specific nitrosamines, an important group of carcinogens in tobacco and tobacco smoke. Carcinogenesis 9:875–884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hecht SS, Carmella SG, Foiles PG, Murphy SE, Peterson LA (1993) Tobacco-specific nitrosamine adducts: studies in laboratory animals and humans. Environ Health Perspect 99:57–63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izzotti A, Cartiglia C, Longobardi M, Balansky RM, D’Agostini F, Lubet RA, De Flora S (2004) Alterations of gene expression in skin and lung of mice exposed to light and cigarette smoke. FASEB J 18:1559–1561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin Z, Gao F, Flagg T, Deng X (2004) Tobacco-specific nitrosamine 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone promotes functional cooperation of Bcl2 and c-Myc through phosphorylation in regulating cell survival and proliferation. J Biol Chem 279:40209–40219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jull BA, Plummer HK 3rd, Schuller HM (2001) Nicotinic receptor-mediated activation by the tobacco-specific nitrosamine NNK of a Raf-1/MAP kinase pathway, resulting in phosphorylation of c-myc in human small cell lung carcinoma cells and pulmonary neuroendocrine cells. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 127:707–717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koga Y, Satoh S, Sodeyama N, Hashimoto Y, Yanagisawa T, Hirshman CA (1992) Role of acetylcholinesterase in airway epithelium-mediated inhibition of acetylcholine-induced contraction of guinea-pig isolated trachea. Eur J Pharmacol 220:141–146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurzen H, Berger H, Jager C, Hartschuh W, Naher H, Gratchev A, Goerdt S, Deichmann M (2004) Phenotypical and molecular profiling of the extraneuronal cholinergic system of the skin. J Invest Dermatol 123:937–949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindstrom J, Peng AR, Gerzanich V (1995) Neuronal nicotinic receptor structure and function. In: Clarke PBS, Quik M, Adlkofer F, Thurau K (eds) Effects of nicotine on biological systems. Birkhäuser, Basel, pp 45–50 [Google Scholar]

- Mai H, May WS, Gao F, Jin Z, Deng X (2003) A functional role for nicotine in Bcl2 phosphorylation and suppression of apoptosis. J Biol Chem 278:1886–1891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majno G, Joris I (1995) Apoptosis, oncosis, and necrosis: an overview of cell death. Am J Pathol 146:3–15 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maneckjee R, Minna JD (1990) Opioid and nicotine receptors affect growth regulation of human lung cancer cell lines. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 87:3294–3298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maneckjee R, Minna JD (1994) Opioids induce while nicotine suppresses apoptosis in human lung cancer cells. Cell Growth Diff 5:1033–1040 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maus ADJ, Pereira EFR, Karachunski PI, Horton RM, Navaneetham D, Macklin K, Cortes WS, Albuquerque EX, Conti-Fine BM (1998) Human and rodent bronchial epithelial cells express functional nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Mol Pharmacol 54:779–788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minna JD (2003) Nicotine exposure and bronchial epithelial cell nicotinic acetylcholine receptor expression in the pathogenesis of lung cancer. J Clin Invest 111:31–33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murrah VA, Gilchrist EP, Moyer MP (1993) Morphologic and growth effects of tobacco-associated chemical carcinogens and smokeless tobacco extracts on human oral epithelial cells in culture. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 75:323–332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen VT, Hall LL, Gallacher G, Ndoye A, Jolkovsky DL, Webber RJ, Buchli R, Grando SA (2000a) Choline acetyltransferase, acetylcholinesterase, and nicotinic acetylcholine receptors of human gingival and esophageal epithelia. J Dent Res 79:939–949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen VT, Ndoye A, Grando SA (2000b) Novel human α9 acetylcholine receptor regulating keratinocyte adhesion is targeted by pemphigus vulgaris autoimmunity. Am J Pathol 157:1377–1391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niphadkar MP, Contractor QQ, Bhisey RA (1994) Mutagenic activity of gastric fluid from chewers of tobacco with lime. Carcinogenesis 15:927–931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohrui T, Sekizawa K, Yamauchi K, Ohkawara Y, Nakazawa H, Aikawa T, Sasaki H, Takishima T (1991) Chemical oxidant potentiates electrically and acetylcholine-induced contraction in rat trachea: possible involvement of cholinesterase inhibition. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 259:371–376 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proskocil BJ, Sekhon HS, Jia Y, Savchenko V, Blakely RD, Lindstrom J, Spindel ER (2004) Acetylcholine is an autocrine or paracrine hormone synthesized and secreted by airway bronchial epithelial cells. Endocrinology 145:2498–2506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ptashne M (1988) How eukaryotic transcriptional activators work. Nature 335:683–689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quik M, Chan J, Patrick J (1994) α-Bungarotoxin blocks the nicotinic receptor mediated increase in cell number in a neuroendocrine cell line. Brain Res 655:161–167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Racke K, Matthiesen S (2004) The airway cholinergic system: physiology and pharmacology. Pulm Pharmacol Ther 17:181–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuller HM, Orloff M (1998) Tobacco-specific carcinogenic nitrosamines. Ligands for nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in human lung cancer cells. Biochem Pharmacol 55:1377–1384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuller HM, Nylen E, Park P, Becker KL (1990) Nicotine, acetylcholine and bombesin are trophic growth factors in neuroendocrine cell lines derived from experimental hamster lung tumors. Life Sci 47:571–578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuller HM, Jull BA, Sheppard BJ, Plummer HK (2000) Interaction of tobacco-specific toxicants with the neuronal α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor and its associated mitogenic signal transduction pathway: potential role in lung carcinogenesis and pediatric lung disorders. Eur J Pharmacol 393:265–277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuller HM, Plummer HK 3rd, Jull BA (2003) Receptor-mediated effects of nicotine and its nitrosated derivative NNK on pulmonary neuroendocrine cells. Anat Rec 270A:51–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sgard F, Charpantier E, Bertrand S, Walker N, Caput D, Graham D, Bertrand D, Besnard F (2002) A novel human nicotinic receptor subunit, α10, that confers functionality to the α9-subunit. Mol Pharmacol 61:150–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shriver SP, Bourdeau HA, Gubish CT, Tirpak DL, Davis AL, Luketich JD, Siegfried JM (2000) Sex-specific expression of gastrin-releasing peptide receptor: relationship to smoking history and risk of lung cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 92:24–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sistonen L, Sarge KD, Morimoto RI (1994) Human heat shock factors 1 and 2 are differentially activated and can synergistically induce hsp70 gene transcription. Mol Cell Biol 14:2087–2099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonenberg N, Hershey JWB, Mathews MB (2000) Translational control of gene expression, 2nd edn. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, New York [Google Scholar]

- Song P, Sekhon HS, Jia Y, Keller JA, Blusztajn JK, Mark GP, Spindel ER (2003a) Acetylcholine is synthesized by and acts as an autocrine growth factor for small cell lung carcinoma. Cancer Res 63:214–221 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song P, Sekhon HS, Proskocil B, Blusztajn JK, Mark GP, Spindel ER (2003b) Synthesis of acetylcholine by lung cancer. Life Sci 72:2159–2168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinbach JH (1990) Mechanism of action of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. In: Bock G, Marsh J (eds) The biology of nicotine dependence. Meeting, London, England, UK, 7–9 November 1989. Wiley, New York, pp 53–61

- Sun X, Liu Y, Hu G, Wang H (2004) Protective effects of nicotine against glutamate-induced neurotoxicity in PC12 cells. Cell Mol Biol Lett 9:409–422 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taisne C, Norel X, Walch L, Labat C, Verriest C, Mazmanian GM, Brink C (1997) Cholinesterase activity in pig airways and epithelial cells. Fundam Clin Pharmacol 11:201–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarroni P, Rubboli F, Chini B, Zwart R, Oortgiesen M, Sher E, Clementi F (1992) Neuronal-type nicotinic receptors in human neuroblastoma and small-cell lung carcinoma cell lines. FEBS Lett 312:66–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trump BF, Berezesky IK, Chang SH, Phelps PC (1997) The pathways of cell death: oncosis, apoptosis, and necrosis. Toxicol Pathol 25:82–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Pereira EF, Maus AD, Ostlie NS, Navaneetham D, Lei S, Albuquerque EX, Conti-Fine BM (2001) Human bronchial epithelial and endothelial cells express alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Mol Pharmacol 60:1201–1209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West KA, Brognard J, Clark AS, Linnoila IR, Yang X, Swain SM, Harris C, Belinsky S, Dennis PA (2003) Rapid Akt activation by nicotine and a tobacco carcinogen modulates the phenotype of normal human airway epithelial cells. J Clin Invest 111:81–90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willey JC, Broussoud A, Sleemi A, Bennett WP, Cerutti P, Harris CC (1991) Immortalization of normal human bronchial epithelial cells by human papillomaviruses 16 or 18. Cancer Res 51:5370–5377 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams CL (2003) Muscarinic signaling in carcinoma cells. Life Sci 72:2173–2182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams CL, Lennon VA (1991) Activation of muscarinic acetylcholine receptors inhibits cell cycle progression of small cell lung carcinoma. Cell Regul 2:373–382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wogan GN, Hecht SS, Felton JS, Conney AH, Loeb LA (2004) Environmental and chemical carcinogenesis. Semin Cancer Biol 14:473–486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao L, Kuo YP, George AA, Peng JH, Purandare MS, Schroeder KM, Lukas RJ, Wu J (2003) Functional properties of homomeric, human alpha 7-nicotinic acetylcholine receptors heterologously expressed in the SH-EP1 human epithelial cell line. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 305:1132–1141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou H, Calaf GM, Hei TK (2003) Malignant transformation of human bronchial epithelial cells with the tobacco-specific nitrosamine, 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone. Int J Cancer 106:821–826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zia S, Ndoye A, Nguyen VT, Grando SA (1997) Nicotine enhances expression of the α3, α4, α5, and α7 nicotinic receptors modulating calcium metabolism and regulating adhesion and motility of respiratory epithelial cells. Res Commun Mol Pathol Pharmacol 97:243–262 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]