Abstract

Purpose

Frizzled motif associated with bone development (FRZB) was a member of secreted frizzled related proteins (sFRPs) family. Previous evidences showed that FRZB played role in embryogenesis and diseases such as osteoarthritis and prostate cancer. The purpose of our study is to clarify the role of FRZB in gastric cancer cell proliferation and differentiation.

Methods

The expression of FRZB in gastric cancer tissues were detected by immunohistochemistry. The expression of FRZB in eight gastric cancer cell lines and one immortal gastric epithelial cell GES-1 were detected by western blotting and real-time quantitative PCR. To investigate the role of over-expressed FRZB in gastric cancer cells, FRZB/pcDNA3.1 plasmid was constructed and transfected into gastric cancer cell line SGC7901. The changes of biological features in these stable transfectants were examined.

Results

FRZB was highly expressed in gastric cancer (90%), intestinal metaplasia (100%) and gastric dysplasia (90%), but no or just weakly (3/40) expressed in normal gastric mucosa. FRZB staining was stronger in intestinal-type gastric cancer tissues than that in diffuse-type ones and was positive correlated with differentiation grade. The expression of FRZB in eight gastric cancer cell lines was higher than in GES-1. Over-expressed FRZB inhibited cell proliferation in vitro and in vivo which was first caused by prolonged cell division progression in G2/M phase, and second by higher sensitivity to apoptotic inducing factors and spontaneous apoptosis. Our findings gave evidences that FRZB suppressed gastric cancer cell proliferation and modulated the balance between proliferation and differentiation in gastric cancer.

Keywords: FRZB, Gastric cancer, Tumorigenicity, Differentiation, Cell division cycle, Apoptosis

Introduction

Gastric cancer is one of the most common malignancies throughout the world, especially in East Asian countries such as China, Japan, and Korea (Alberts et al. 2003; Roder 2002). Worldwide, gastric cancer is the second largest cause of cancer-related death (The World Health Report 1997). Precise mechanisms that underlie gastric cancer carcinogenesis are not yet fully understood. According to Lauren classification, gastric cancer can be divided into two histological types, intestinal and diffused types. Intestinal-type carcinomas are thought to develop through well-characterized sequential stages—chronic gastritis, atrophy, intestinal metaplasia and dysplasia (Correa 1992; Correa and Chen 1994). On the other hand, the diffuse type develops through a shorter, less well-characterized sequence of events from gastric epithelial cells. These two types have different epidemiology, etiology, pathogenesis and biological behavior. The two different types of gastric cancer may differ in biological aggressiveness, prognostic associations and response to therapy. It’s important to find some markers to discriminate these two types for better therapy and improve survival rate.

Whether tumors arise from dedifferentiation of mature cells or from maturation arrest of immature stem cells is not fully clarified. However, evidence showed that differentiation and malignancy were inversely correlated. Much has been learned recently about the transcriptional control of gut differentiation. Although the genetic events responsible for aberrations in differentiation have not been well clarified, several candidate genes, most of which are involved in gut development, have been found to be associated with intestinal metaplasia in humans and mice (Suh and Traber 1996). Inappropriate activation of the intestine-specific transcription factor CDX2 is one of the most likely contributing factors in the induction of intestinal metaplasia of the stomach (Suh and Traber 1996) and so are APC (Lee et al. 2002; Suzuki et al. 1999) and TP53 (Kim et al. 1991; Tamura et al. 1991). And recently, some tumor suppressors of gastric cancer were identified, such as, RunX3 (Wei et al. 2005a), and KLK4 (Wei et al. 2005b). However, the mechanisms that underlie most cases of this type of cancer remain to be determined.

Wnt proteins are secreted signaling factors that play multiple roles during development (Sokol 2000; Kelleher et al. 2006) and modulate proliferation, differentiation and apoptosis in many adult organs and tissues, such as the gut. Each of the WNT signaling components are involved in patterning of the gut (Lickert et al. 2001; McBride et al. 2003). Previous studies found that abnormally activated WNT signaling was associated with gastric cancer tumorigenesis and progression (Seidensticker 2000; Katoh 2005; Cheng et al. 2005; Koppert et al. 2004; Saitoh and Katoh 2002). sFRPs are antagonists of WNT signaling. Recently, down-regulated sFRPs were reported in many cancers including colon cancer (Suzuki et al. 2004), mesothelioma (Lee et al. 2004), bladder cancer (Marsit et al. 2005) and prostate cancer (Zi et al. 2005). FRZB/sFRP3 is a member of sFRPs, contains a 24-amino acid putative transmembrane segment (Hoang et al. 1996), a cysteine-rich domain (CRD) which is similar to the putative Wnt-binding region of the frizzled family of transmembrane receptors, a netrin-like domain (NTR) which is homologous with tissue inhibitors of metalloproteases (TIMPs) (Banyai and Patthy 1999). FRZB was first purified as a chondrogenic factor in mammalian skeleton morphogenesis (Hoang et al. 1996; Wada et al. 1999). Secreted FRZB antagonized the effects of Xwnt-8 (Wang et al. 1997; Leyns et al. 1997), Wnt-1 (Leyns et al. 1997) and Wnt-1-induced accumulation of β-catenin (Lin et al. 1997). FRZB was antagonist of Wnt-9a and inhibit WNT/Canonical pathway through decreasing β-catenin accumulation (Person et al. 2005). Recent studies discovered a haplotype in the FRZB gene, which was related to primary osteoarthritis of the hip in females (Loughlin et al. 2004).

It was reported that FRZB suppressed cell growth and was involved in EMT in prostate cancer (Zi et al. 2005). The different expression pattern of FRZB in cancer might be due to different roles and different cancers being involved. But the expression and function of FRZB in gastric cancer has not been clarified. In this study, we investigated whether and how FRZB contributed to the malignant phenotype of gastric cancer.

Materials and methods

Cell lines, culture condition and tissue collection

Gastric cancer cell lines NCI-N87 (ATCC: CRL-5822), SNU-1 (ATCC: CRL-5971), SNU-16 (ATCC: CRL-5974), AGS (ATCC: CRL-1739), and KATOIII (ATCC: HTB-103) were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA). Another three gastric cancer cell lines MKN45, MKN28 and SGC7901 were preserved in our institute. Immortalized gastric mucosal epithelial cell line GES-1 was a gift from Prof. Feng Bi (Institute of Digestive Disease, Xi’jing Hospital, the Fourth Military Medical University). All cell lines were maintained in RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and antibiotics. For serum starvation, the medium was changed into serum free RMPI-1640 medium when cells were subconfluent and then cultured for 72 h. Cisplatin (Nihon Kayaku Co., Tokyo, Japan) was freshly prepared before each experiment with saline solution. The conditioned medium (serum free RMPI-1640 medium) was concentrated by Centricon (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA) and loaded onto SDS-PAGE gel for western blotting analysis.

A total of 90 primary gastric cancers, 40 adjacent normal tissues, 10 intestinal metaplasia and 10 gastric dysplasia were archived from surgically treated gastric cancer diagnosed at the Department of Surgery, Ruijin Hospital, School of Medicine, Shanghai Jiao Tong University from 2001 to 2003. All gastric cancer cases were clinically and pathologically proved. The pathological tumor staging was determined according to the UICC TNM classification (Wittekind and Sobin 2002).

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

IHC assay was performed on 5 μm, formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue sections using the streptavidin-biotin supersensitive method. Briefly, 5 μm-thick tissue slides were deparaffinized in xylene and rehydrated serially with alcohol and water. Endogenous peroxidase was blocked with 3% hydrogen peroxide for 10 min, followed by microwave antigen retrieval in 10 mM citrate buffer (pH 6.0). The slides were blocked with 2% BSA in PBS for 30 min and incubated overnight with specified diluted rabbit anti-FRZB polyclonal antibody (1:50 dilution; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) overnight at 4°C. The experimental procedure was according to the manufacturer’s instructions of LSAB+ kit (Dako, Carpinteria, CA, USA). Normal rabbit purified IgG serum was used instead of first antibody as negative control.

FRZB expression was determined in three categories (negative, weak positive and strong positive) by assessing the percentage and intensity of stained tumor cells as described previously (Jiang et al. 2004): the percentage of positive cells was classified according to five grades (percentage scores): <10% (grade 0), 10–25% (grade 1), >25–50% (grade 2), >50–75% (grade 3), and >75% (grade 4). The staining intensity was classified according to four grades (intensity scores): no staining (grade 0), light brown staining (grade 1), brown staining (grade 2), and dark brown staining (grade 3). FRZB staining positivity was determined with the formula: overall score = percentage score + intensity score. An overall score of ≤3, >3 to ≤6, and >6 was defined as negative, weak positive, and strong positive, respectively.

Plasmid construction and stable transfection

FRZB full-length cDNA was using primers 5′ -ATC TCG AGA GCT CCC AGA TCC TTG TGT C- 3′ (F), 5′ -ATG GAT CCC TTT TTG TAT TTC GGG ATT TAG TT- 3′ (R) and subcloned into pcDNA3.1 vector to generate the pcDNA3.1/FRZB construct. SGC7901 cells were transfected at 60–70% confluence with pcDNA3.1 and FRZB/pcDNA3.1 plasmid using DOTAP (Roche, Indianapolis, IN, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Cells were cultured in medium supplemented with G418 (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) at 1 mg/ml for 4 weeks and then maintained in medium containing 350 μg/ml G418. Stably transfected clones were picked and all of the stable transfectants were pooled to avoid cloning artifacts. Stably transfected pcDNA3.1 clones used as control cells in this study.

Quantitative RT-PCR (QRT-PCR)

Total RNA was extracted from 1 × 105 cells by Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). One microgram of RNA was converted into cDNA using the Reverse Transcription System (Promega) with oligo dT. QRT-PCR was carried out with a set of primers for FRZB were 5′-GAG GAG CTG CCA GTG TAC GAC-3′ (F), 5′-GAA AAT CAG CTC CGT CCG C-3′ (R), GAPDH were 5′-GGA CCT GAC CTG CCG TCT AG-3′ (F), 5′-GTA GCC CAG GAT GCC CTT GA-3′ (R) respectively. QRT- PCR for quantitation of the mRNA levels of FRZB was done on an ABI Prism 7000 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) using SYBR Green (Applied Biosystems, Warrington, UK). Data were analyzed by using the comparative Ct method. Specificity of resulting PCR products was confirmed by melting curves.

Western blotting

Protein extraction was done by mammalian protein extraction reagent (M-PER) (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA) supplemented with protease inhibitors cocktail (Sigma Chemical, St Louis, MO, USA) and protein quantification was performed by BCA Protein Assay kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA). Equal amounts of proteins (50 μg) were loaded onto the 12% SDS-polyacrylamide gel and separated by SDS-PAGE, the resolved proteins were transfered onto PVDF membrane (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). After blocking with 5% nonfat milk in TBST (20 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% Tween 20) for 2 h at room temperature, the membrane was hybridized with polyclonal rabbit anti-FRZB (1:750; Santa Cruz), polyclonal rabbit anti-capase-3 (1:1000; BD Transduction Laboratories, Lexington, KY), monoclonal mouse anti-GAPDH (1:1000, Santa Cruz), monoclonal mouse anti-cyclin B1 (1:5000; Abcam, Cambridge, UK) and visualized by an enhanced chemiluminescence detection system (Amersham Bioscience, Piscataway, NJ, USA) doing as the manufacturer’s protocol.

Cell cycle synchronization and cell cycle analysis by flow cytometry

Cells were arrested in G1/S phase using a double thymidine block or in mitosis with a thymidine-nocodazole block essentially as described previously (Whitfield et al. 2002). Briefly, cells were cultured for 16 h in medium with 2 mM thymidine (Sigma), released to fresh medium for 8 h, and arrested for another 16 h in medium with 2 mM thymidine (Sigma). Cells were released and collected, every 2 to 3 h, depending on the experiments. For thymidine-nocodazole block, cells were arrested in 2 mM thymidine for 16 h, released for 4 h and blocked in 100 ng/ml nocodazole for 12 h. The floating mitotic cells were collected as control. Single cells were fixed in 70% ice-cold ethanol at 4°C overnight, washed with PBS, incubated with 100 μg/ml RNase at 37°C for 20 min. After staining with propidium iodide (50 μg/ml), the cells were subjected to fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS) on a FACScan (Beckman Instruments, Fullerton, CA, USA). The cells with sub-G1 DNA content were considered as apoptotic cells.

Cell growth assay

The parental (SGC7901), pcDNA3.1 transfactected (SGC7901/pcDNA3.1) and stably FRZB full-length cDNA transfected cells (SGC7901/FRZB) (1 × 103) were seeded into 96-well plates in triplicate. The number of viable cells was determined daily by an MTS (3-[4, 5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl-5]-[3-carboxymethoxyphenyl]-2-[4-sulfophenyl]-2H tetrazolium) non-radioactive cell proliferation assay (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). Briefly, 25 μl of freshly prepared MTS mixture was added, absorbance at 490 nm was measured after 1 h incubation.

Soft agar colony formation assay

A soft agar colony formation assay was done using six-well plates. Cells (3 × 103) were trypsinized to single-cell suspension, mixed in 2 ml of 0.3% (w/v) and 0.6% (w/v) agar in complete medium as the top and bottom layer in triplicate, respectively. After 16 days culture, the number of colonies was determined with an inverted phase-contrast microscope at ×100 magnification; a group of >50 cells was counted as a colony. The data are means ± SD of counting ten random fields of vision.

Tumor xenograft model and tumorigenicity assay

Male BALB/c nu/nu nude mice, six-week-old (Institute of Zoology Chinese Academy of Sciences), were housed at a specific pathogen-free environment in the Animal Laboratory Unit, School of Medicine, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, China. SGC7901, SGC7901/pcDNA3.1 and SGC7901/FRZB cells were harvested, washed and re-suspended in PBS, respectively, then, 1 × 106 cells in 0.1 ml PBS were injected subcutaneously into the right flank regions. Mice were checked every 3 days for tumor appearance and tumor sizes were determined by measuring two diameters with a caliper as described previously (Tu et al. 2003). Tumor volume (V) was estimated by using the equation V = 4/3π × L/2 × (W/2)2, where L is the mid-axis length, and W is the mid-axis width. Four mice were included in each group in all experiments, and each experiment was performed twice. Animals were sacrificed 27 days after tumor cell implantation. Tumor specimens were collected, fixed in formalin, and embedded in paraffin, and subjected to H&E staining,and IHC.

TUNEL analysis

The TUNEL assay was performed using FragEL™ DNA Fragmentation Detection kit (Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA, USA) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. The negative control was generated by substituting H2O for the TdT in the reaction mixture during the labeling step. The positive control was generated by covering the entire specimen with 1 μg/μl DNase I in 1 × TBS/1 mM MgSO4 following proteinase K treatment for 20 min. All other steps were performed as described.

Statistical analysis

Results were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical analyses were performed using SAS 6.12 software package (School of Medicine, Shanghai Jiao Tong University). The χ2 test and Fisher exact test were used to test significance of the difference in frequency of FRZB between normal and tumor samples. The correlation between FRZB expression in the tumors and clinicopathological parameters was calculated with the Kruskal–Wallis rank test and the Mann–Whitney U test. P < 0.05 was selected as the statistically significant value.

Results

FRZB expression in gastric cancer tissues and cell lines

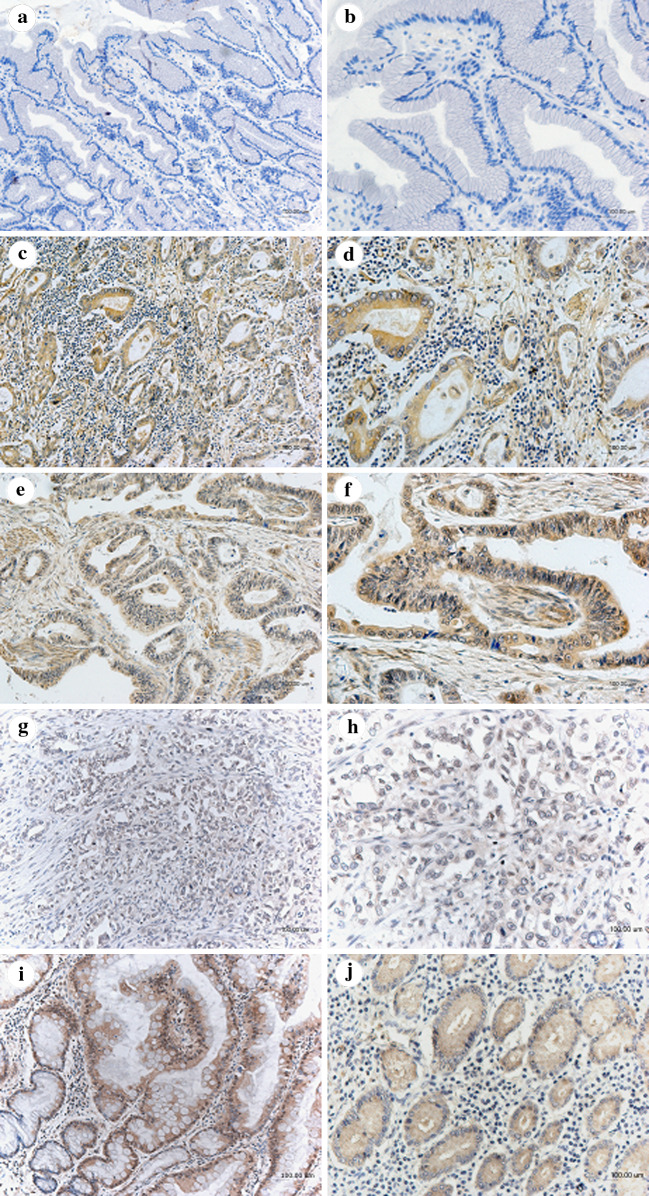

To evaluate the FRZB expression in gastric cancer, FRZB immunostaining in 90 primary gastric cancer tissues and 40 adjacent normal gastric mucosae were examined. The normal gastric mucosae showed no FRZB staining (37/40) (Fig. 1a, b) or very weak staining (3/40), while significantly higher levels of FRZB expression in the cytoplasm were observed in the gastric cancer tissues (Fig. 1c–h) with a frequency of 90% (83/90). The intestinal metaplasia (10/10) and gastric dysplasia (9/10) showed both strong and moderate staining of FRZB, respectively (Fig. 1i, j). The correlation of high expression of FRZB with the clinicopathological features was shown in Table 1. FRZB expresssion was higher in differentiated tumors (well- and moderate adnocarcinomas) than that in undifferentiated ones (poorly differentiated adenocarcinomas, signet ring cell carcinomas and mucinous carcinomas) (Kuniyasu et al. 1998) (p = 0.022). Meanwhile, the degree of FRZB staining was in correlation with Lauren classification (p < 0.001), which was higher expressed in intestinal type than in diffuse type and mixed type ones. There were no significant differences in tumor FRZB expression according to the other clinicopathological features such as age, gender, tumor size, TNM stage and tumor metastasis.

Fig. 1.

Expression of FRZB in gastric cancer and normal gastric mucosa was detected by IHC staining. a, b Normal gastric mucosa showed negative staining. c, d Well-differentiated gastric cancer showed strong positive staining. e, f Moderate-differentiated gastric cancer showed medium positive staining. g, h Poor-differentiated gastric cancer showed weak positive staining. i Intestinal-metaplasia showed strong staining of FRZB. j Dysplasia showed moderate staining of FRZB. Original magnifications: ×200 (a, c, e, g, i, j); ×400 (b, d, f, h )

Table 1.

Clinicopathological associations of FRZB expression in gastric cancer

| Number of cases | FRZB immunostaining | P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative (-) | Weak (+) | Strong (++) | |||

| Gender | 0.3145 | ||||

| Male | 58 | 3 | 36 | 19 | |

| Female | 32 | 4 | 12 | 16 | |

| Tumor size | 0.6656 | ||||

| ≤5cm | 52 | 2 | 30 | 20 | |

| >5cm | 38 | 5 | 18 | 15 | |

| Differentiation | 0.0220 | ||||

| Well | 9 | 1 | 2 | 6 | |

| Moderate | 31 | 1 | 14 | 16 | |

| Poor | 50 | 5 | 18 | 7 | |

| Lauren classification | <0.001 | ||||

| Intestinal | 32 | 0 | 10 | 22 | |

| Diffuse | 20 | 3 | 15 | 2 | |

| Mixed | 38 | 4 | 23 | 11 | |

| Lymph node metastasis | 0.464 | ||||

| N0 | 20 | 0 | 11 | 9 | |

| N1 | 44 | 3 | 24 | 17 | |

| N2/N3 | 26 | 4 | 13 | 9 | |

| T stage | 0.1125 | ||||

| T2 | 33 | 1 | 17 | 15 | |

| T3 | 38 | 3 | 19 | 16 | |

| T4 | 19 | 3 | 12 | 4 | |

| TNM stage | 0.569 | ||||

| I + II | 32 | 4 | 16 | 12 | |

| III + IV | 58 | 3 | 32 | 23 | |

| Distance metastasis | 0.2294 | ||||

| With | 48 | 3 | 30 | 15 | |

| Without | 42 | 4 | 18 | 20 | |

Note. Interpretation of FRZB immunostaining was described in Materials and methods

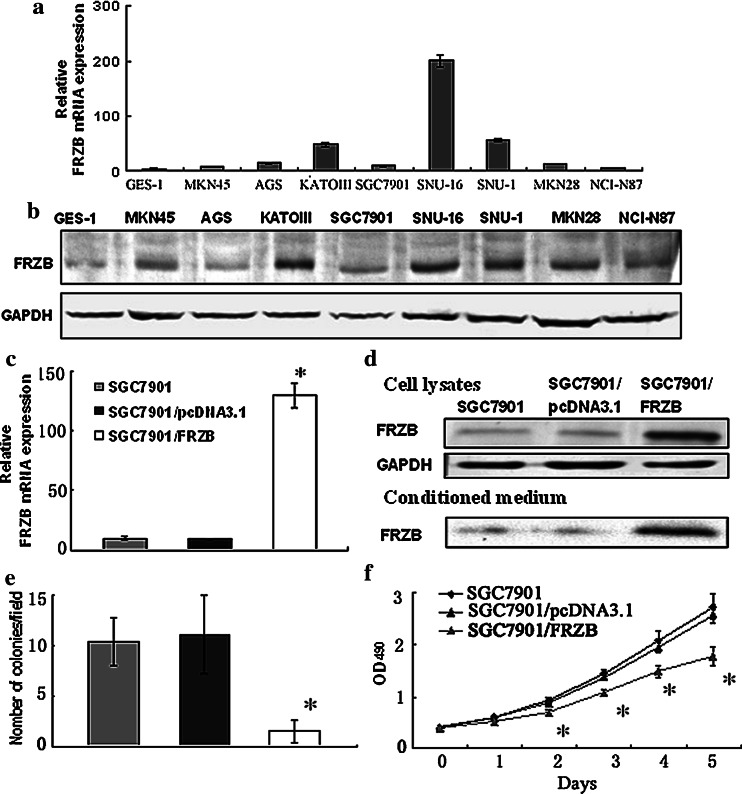

The expression of FRZB was higher both in mRNA (Fig. 2a) and protein level (Fig. 2b) in eight gastric cancer cell lines as compared with immortalized gastric mucosa cell line GES-1. Among these eight gastric cancer cell lines, AGS and SGC7901 cell expressed relatively lower FRZB.

Fig. 2.

Over-expression of FRZB in SGC7901 cells decreased cell growth and colony formation. a QRT-PCR analysis of FRZB mRNA in eight gastric cancer cell lines and GES-1. b Western blotting analysis of FRZB protein in eight gastric cancer cell lines and GES-1. The 37kD band was detected by anti-FRZB antibody (upper line) and 42kD band was detected by anti-GAPDH antibody (lower line) as loading control. c QRT-PCR analysis of FRZB mRNA in SGC7901, pcDNA3.1 and pcDNA3.1/FRZB stable transfectants. d Western blotting analysis of FRZB protein in whole cell lysates and conditioned medium using anti-FRZB, anti-GAPDH antibody. e Quantitative analysis of soft agar colony formation of parental SGC7901, pcDNA3.1 and pcDNA3.1/FRZB stable transfectants. f Over-expression of FRZB suppressed SGC7901 cell growth. Monolayer growth rates of cells were determined by MTS assay. Values represent the mean ± SD from at least three separate experiments, each conducted in triplicate. *, P < 0.001 compared with parental cells and pcDNA3.1 transfectants

Over-expression of FRZB inhibited SGC7901 cell proliferation and colony formation

To elucidate the role of FRZB in gastric carcinogenesis, a FRZB expression plasmid was constructed and transfected into SGC7901. To confirm the FRZB expression in stable transfectans, we examined the expression of FRZB by QRT-PCR and western blotting. The expression of FRZB was up-regulated in SGC7901/FRZB cells both in cell lysates and conditioned medium (Fig. 2d) which paralleled with QRT-PCR result (Fig. 2c).

In vitro cell proliferation tests showed that SGC7901/FRZB cells grew significantly slower than SGC7901 and SGC7901/pcDNA3.1 cells (Fig. 2f) and the colony formation rate was (10.4 ± 2.4) %, (11.1 ± 3.9) % and (1.5 ± 1.1) % in SGC7901, SGC7901/pcDNA3.1 and SGC7901/FRZB cells, respectively, (Fig. 2e). The size of colonies formed by SGC7901/FRZB cells was much smaller than that of two control cells, and there were no significant differences between SGC7901 and SGC7901/pcDNA3.1 cells colonies both in number and size.

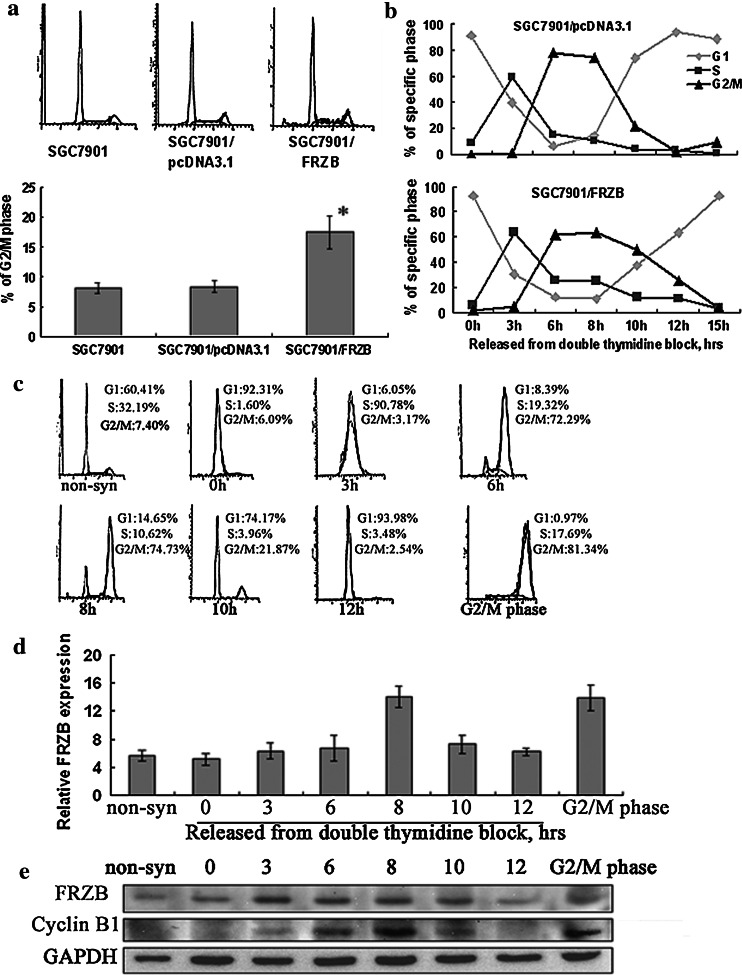

FRZB periodically expressed in cell division progression and over-expression of FRZB-induced prolonged cell cycle progression in G2/M

In asynchronous three groups of cells, we revealed that the population of cells in G2/M phase increased in SGC7901/FRZB (16.71%) than in SGC7901 (7.40%) and SGC7901/pcDNA3.1 (8.07%) cells (Fig. 3a). Cell cycle arrest is a common feature of cells undergoing defective proliferation (Philipson 1998). We then dealt cells with double thymidine synchronization and collected at 0 h (released time), 3, 6, 8, 10, 12 and 15 h after released. Cell cycle division time prolonged in SGC7901/FRZB cells (15 h) than in SGC7901 and SGC7901/pcDNA3.1 cells (12 h) (Fig. 3b, as there is no significant difference between SGC7901 and SGC7901/pcDNA3.1 cells, our figure only showed SGC7901/pcDNA3.1 and SGC7901/FRZB cells as representation). We noticed that FRZB/pcDNA3.1 transfectants stayed in G2/M phase 3 h longer than the control cells. This explained why the percentage of G2/M phase cells in FRZB transfectants was higher than that in the control groups.

Fig. 3.

FRZB periodically expressed in cell division progression and induced G2/M arrest in SGC7901. a FCM analysis of cell cycle distribution under normal condition culture. b Cell cycle distribution as determined by FCM. Relative proportions of pcDNA3.1 and pcDNA3.1/FRZB transfectants in G1-, S-, G2/M phase were shown in dependence upon time interval after released from G1/S block. c FCM analysis of DNA content of SGC7901 cells at different cell division progression. Non-syn represented asynchronous cells. G2/M phase cells were obtained by thymidine-nocodazole double block. d QRT-PCR analysis of mRNA expression profile of FRZB at different cell division point. e Western blotting analysis of protein expression profile of FRZB at different cell division point. Whole cell lysates were subjected to western blotting using anti-FRZB, anti-cyclin B1 and anti-GAPDH antibody. These results were repeated in three independent experiments. *, P < 0.001 compared with parental cells and pcDNA3.1 transfectants

We collected cells that mostly in G1 phase (0 and 12 h), S phase (3 h), G2/M phase (6 and 8 h), M to G1 phase (10 h), and collected cells 3 h after released from thymidine-nocodazole block as G2/M phase control. The distribution and percentage of cells in specific cell division phase was confirmed (Fig. 3c). FRZB mRNA reached its peak at 8 h after released from double thymdine block, which represented cells in mitotic phase (Fig. 3d). FRZB protein expressed higher in S and G2/M phase than G1 phase, increased slightly ahead of cyclin B1 which reached its peak at G2/M phase (Fig. 3e). These results indicated that over-expressed FRZB might enhance the influence of endogenous FRZB at G2/M phase and inducing cell cycle progression delay.

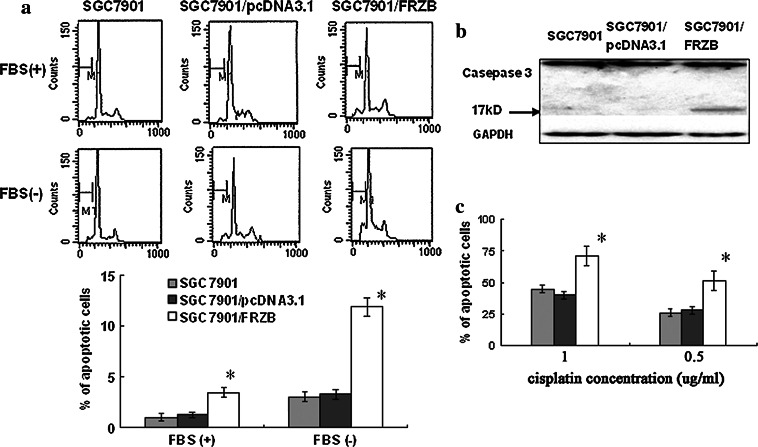

Over-expression of FRZB promoted SGC7901 cells to apoptosis in vitro

The spontaneous apoptosis rates were (0.99 ± 0.35%), (1.21 ± 0.41%) and (3.45 ± 0.53%) (Fig. 4a, top) in SGC7901, SGC7901/pcDNA3.1 and SGC7901/FRZB cells, respectively. Under serum deprivation condition, the apoptotic rate in SGC7901, SGC7901/pcDNA3.1 and SGC7901/FRZB cells was (3.04 ± 0.24%), (3.28 ± 0.45%), (11.86 ± 0.87%) (Fig. 4a, bottom), respectively. The SGC7901/FRZB cells were more susceptible to the apoptotic stimuli than SGC7901 and SGC7901/pcDNA3.1 cells. To confirm these data, we measured the apoptotic rate induced by cisplatin, which is known as a cell cycle-independent drug in treatment of different types of cancer including gastric cancer and is also known to induce cell apoptosis (Shi et al. 2004). The drug concentration 1.0 μg/ml that triggered apoptosis in SGC7901 cells was adjusted according to previous (Shi et al. 2004) which caused approximate 50% cell death. The drug concentration inducing 50% cell death in FRZB over-expressed cells was 0.5 μg/ml, which in control cells was 1.0 μg/ml (Fig. 4c). The activated caspase-3 was also clearly seen in SGC7901/FRZB cells comparative to SGC7901 and SGC7901/pcDNA3.1 cells (Fig. 4b). These results suggested that the over-expressed FRZB induced caspase-dependent apoptosis in gastric cancer cells.

Fig. 4.

Over-expression of FRZB enhanced spontaneous apoptotic rate and sensitivity to apoptotic inducing factors. a Over-expression of FRZB enhanced spontaneous and sensitivity to serum starvation apoptotic rate. The upper and lower layer showed the apoptotic rate of with and without serum cultured cells, respectively. M1 represented sub-G1 DNA. The columns showed the percentage of spontaneous and starvation inducing apoptotic cells. b The activated caspase-3 in parental SGC7901, pcDNA3.1 and pcDNA3.1/FRZB stable transfectants was determined by western blotting. c SGC7901, SGC7901/pcDNA3.1 and SGC7901/FRZB cells were treated with cisplatin in 1 and 0.5 μg/ml for 72 h, and then measured by MTS assay to determine the drug inducing apoptotic cells. These results represent the mean ± SD of three independent experiments. *, P < 0.001 compared with parental cells and pcDNA3.1 transfectants

Over-expression of FRZB inhibited tumorigenicity of SGC7901 s and induced apoptosis in vivo

We then examined the in vivo effect of over-expressed FRZB by injecting SGC7901, SGC7901/pcDNA3.1 and SGC7901/FRZB cells subcutaneously into the right flank regions of nude mice. The xenograft tumor growth rates in different groups were compared. Xenograft tumors appeared in all of the animals in two control groups (SGC7901 and SGC7901/pcDNA3.1) at day 6 and exhibited rapid tumor growth over time. However, only five of the eight mice which were injected with SGC7901/FRZB cells appeared with the tumor on day 10 which kept growing very slowly over the next 18 days. The other three mice remained with no tumor formation until sacrificed on day 27 (Fig. 5a). The histology of xenograft tumors were confirmed by H&E staining (Fig. 5b). Over-expressed FRZB in tumor tissues derived from SGC7901/FRZB cells was detected both in IHC staining (Fig. 5c) and western blotting (Fig. 5a). In TUNEL assay, the apoptotic cells in tumors derived from SGC7901, SGC7901/pcDNA3.1 and SGC7901/FRZB cells were (6.38 ± 1.92), (7.11 ± 2.11) and (20.75 ± 3.58) per field, respectively (Fig. 5d, 5e). There were more positive staining tumor cells in SGC7901/FRZB group than that in control groups (P < 0.001). These results suggested that inhibition of tumor growth was partly attributable to increased spontaneous apoptosis in vivo.

Fig. 5.

Over-expression of FRZB suppressed tumorigenesis and increased apoptosis in vivo. a Progression of tumor in nude mice. Tumor volumes were measured every 4 days. Each point means tumor volume (each group four mice), data represent mean ± SD. Western blotting analyzing FRZB expression in tumor extracts (loading amount 50 μg). b H&E staining showed cell morphology of tumors. Tumors from different groups were collected at day 27, fixed and embedded, 5 μm sections were used in H&E staining. c IHC and western blotting assay analysis of FRZB expression in tumors. In compare with SGC7901 and pcDNA 3.1 transfected cells, pcDNA3.1/FRZB transfectants showed higher FRZB expression. d TUNEL assay analysis apoptotic cells in tumor sections. Arrow showed deep brown staining represented apoptotic cells. e The percentage of apoptotic cells was counted. Number 1, 2, 3 represented tumor tissues derived from SGC7901, SGC7901/pcDNA3.1 and SGC7901/FRZB cells, respectively. *, P < 0.001 compared with SGC7901 cells and pcDNA3.1 transfectants. (Original magnification: ×200)

Discussion

FRZB, also known as sFRP3, was a member of the secreted frizzled related protein family. The studies about FRZB focused on embryonic development for many years, showed that it acted as a modulator in development. The role FRZB in embryos including caudal paraxial mesoderm (Schneider and Mercola 2001), skeleton morphogenesis (Wada et al. 1999; Borello et al 1999), and cardiogenesis (Borello et al 1999) was reported yet. Until recently, more and more genes which were previously considered to be participating in embryonic development, now have been found to be important in tumorigenesis. Our immunohistochemical analysis revealed that FRZB was expressed in at least 90% gastric cancers and was present in premalignant lesions (IM and dysplasia). On the contrary, the gastric mucosa did not appear to exhibit FRZB expression or exhibit very faint expression, although other groups had demonstrated that FRZB mRNA did not express in gastric cancer (Byun et al. 2005). This might be caused by different samples (patients, Chinese vs. American) and different detected objects (mRNA vs. protein). In addition, intestinal-type and well/moderate-differentiated gastric cancer appeared to exhibit much higher FRZB expression than diffuse-type and poor-differentiated gastric cancers. To date, multiple molecular alterations which were present in the gastric carcinogenesis had been reported, including IM and dysplasia. Gastric dysplasia was defined as precancerous lesion which was difficult to differentiate accurately and usually appeared as immature phenotypes. IM, another type of precancerous lesions, was often associated with intestinal-type gastric cancer. Our data supported the hypothesis that FRZB might be an early event in the process of gastric carcinogenesis and was in correlation with intestinal-type gastric cancer genesis and differentiation. We supposed that if malignant transformed cells expressed a high level of FRZB, they became intestinal-type gastric cancer and when cancer cells increased their expression of FRZB, the histology of the cancer became well differentiated. Another hypothesis we proposed was that FRZB expression might be an event during normal gastric epithelial cell differentiation and closed in mature mucosa. As the outcome of patients with well- and moderate-differentiated gastric cancer was much better than those with poor-differentiated tumors (Rohatgi et al. 2006), the expression of FRZB might be a predict marker for gastric cancer patients.

To further investigate how FRZB contributes to the biological behavior changes in gastric cancer, we up-regulated the FRZB expression in gastric cancer cell SGC7901. The colony formation and cell growth rate and in vivo tumorgenesity decreased in FRZB over-expressing cells which gave evidences that over-expression of FRZB gastric cancer cell proliferation. Meanwhile, cells in G2/M period were found more in FRZB/pcDNA3.1 tansfectants than the other two groups of control cells. We further analyzed the endogenous FRZB expression pattern in cell cycle division cycle in SGC7901 cells. The expression of FRZB changed periodically in different cell cycle phase both in mRNA and protein level which up-regulated at S phase, peaked in the G2/M phase and was lowest in G1 phase in accordance with the previous study (Whitfield et al. 2002). This result gave us some information about how over-expressed FRZB inhibited cell proliferation. As prolonged G2/M phase might be caused by G2/M phase delay or mitosis exit abnormity, it suggested that FRZB might have a role in cell mitosis or mitosis exit and the over-expressed FRZB might enhance this role in suppressing cell proliferation.

Cell proliferation is essential in normal cell life and turnover. However, when it is excessive, it may lead to a neoplasia. Apoptosis, on the other hand, plays an opposite role in human cell populations. Alteration of the balance between proliferation and apoptosis results in a disturbance of tissue homeostasis and is associated with cancer. Apoptosis is a fundamental cellular activity to maintain the physiological balance of the organism and plays a necessary role as a protective mechanism against carcinogenesis by eliminating damaged cells or cells that proliferate excessively (Hengartner 2000). Evaluation of apoptosis is a potentially useful measure of a tumor cell kinetics and biologic behavior. We found higher spontaneous apoptotic rate, higher sensitivity to apoptotic inducing factors in SGC7901/FRZB cells with caspase-3 activation. By TUNEL assay, the similar result was obtained. These results suggested that FRZB candidates in inducing apoptosis in gastric cancer in caspase-dependant pathway. Furthermore, high apoptotic rate in FRZB over-expressing cells might contribute to cell proliferation suppression.

In summary, IHC analysis indicated that the expression of FRZB was an early event in intestinal-type gastric carcinogenesis and was a differentiation related marker in gastric cancer. Cytological analysis demonstrated that the up-regulated expression of FRZB suppressed gastric cancer formation by arresting cell division in G2/M phase and highlighted apoptotic sensitivity. The above results demonstrated that FRZB played dual roles in gastric normal mucosa and malignant tissues. On the one hand, FRZB expression was closed in normal gastric mucosa, but on the other hand, was opened at cells with malignant transformation-transformed into premature phenotype. FRZB might function as a modulator of cell proliferation and cell differentiation in intestinal-type gastric cancer - inhibiting proliferation and inducing differentiation.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by The National Key Fundamental Research (973 Project of China 2002CB713700) and The National High Technology Research and Development Program of China (863 Program 2002BA711A06).

References

- Alberts SR, Cervantes A, van de Velde CJ (2003) Gastric cancer: epidemiology, pathology and treatment. Ann Oncol 14(Suppl 2):ii31–ii36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borello U, Coletta M, Tajbakhsh S, Leyns L, De Robertis EM, Buckingham M, Cossu G (1999) Transplacental delivery of the Wnt antagonist Frzb1 inhibits development of caudal paraxial mesoderm and skeletal myogenesis in mouse embryos. Development 126:4247–4255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banyai L, Patthy L (1999) The NTR module. Domains of netrins, secreted frizzled related proteins, and type I procollagen C-proteinase enhancer protein are homologous with tissue inhibitors of metalloproteases. Protein Sci 8:1636–1642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byun T, Karimi M, Marsh JL, Milovanovic T, Lin F, Holcombe RF (2005) Expression of secreted Wnt antagonists in gastrointestinal tissues: potential role in stem cell homeostasis. J Clin Pathol 58:515–519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng XX, Wang ZC, Chen XY, Sun Y, Kong QY, Liu J, Li H (2005) Correlation of Wnt-2 expression and beta-catenin intracellular accumulation in Chinese gastric cancers: relevance with tumour dissemination. Cancer Lett 223:339–347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Correa P (1992) Human gastric carcinogenesis: a multistep and multifactorial process—First American Cancer Society Award Lecture on Cancer Epidemiology and Prevention. Cancer Res 52:6735–6740 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Correa P, Chen VW (1994) Gastric cancer. Cancer Surv 19–20:55–76 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hengartner MO (2000) The biochemistry of apoptosis. Nature 407:770–776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoang B, Moos M Jr, Vukicevic S, Luyten FP (1996) Primary structure and tissue distribution of FRZB, a novel protein related to Drosophila frizzled, suggest a role in skeletal morphogenesis. J Biol Chem 271:26131–26137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y, Wang L, Gong W, Wei D, Le X, Yao J, Ajani J, Abbruzzese JL, Huang S, Xie K (2004) A high expression level of insulin-like growth factor I receptor is associated with increased expression of transcription factor Sp1 and regional lymph node metastasis of human gastric cancer. Clin Exp Metastasis 21:755–764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katoh M (2005) WNT/PCP signaling pathway and human cancer (review). Oncol Rep 14:1583–1588 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelleher FC, Fennelly D, Rafferty M (2006) Common critical pathways in embryogenesis and cancer. Acta Oncol 45:375–388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JH, Takahashi T, Chiba I, Park JG, Birrer MJ, Roh JK, De Lee H, Kim JP, Minna JD, Gazdar AF (1991) Occurrence of p53 gene abnormalities in gastric carcinoma tumors and cell lines. J Natl Cancer Inst 83:938–943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koppert LB, van der Velden AW, van de Wetering M, Abbou M, van den Ouweland AM, Tilanus HW, Wijnhoven BP, Dinjens WN (2004) Frequent loss of the AXIN1 locus but absence of AXIN1 gene mutations in adenocarcinomas of the gastro-oesophageal junction with nuclear beta-catenin expression. Br J Cancer 90:892–899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuniyasu T, Nakamura T, Tabuchi Y, Kuroda Y (1998) Immunohistochemical evaluation of thymidylate synthase in gastric carcinoma using a new polyclonal antibody: the clinical role of thymidylate synthase as a prognostic indicator and its therapeutic usefulness. Cancer 83:1300–1306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JH, Abraham SC, Kim HS, Nam JH, Choi C, Lee MC, Park CS, Juhng SW, Rashid A, Hamilton SR, Wu TT (2002) Inverse relationship between APC gene mutation in gastric adenomas and development of adenocarcinoma. Am J Pathol 161:611–618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee AY, He B, You L, Dadfarmay S, Xu Z, Mazieres J, Mikami I, McCormick F, Jablons DM (2004) Expression of the secreted frizzled-related protein gene family is downregulated in human mesothelioma. Oncogene 23:6672–6676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leyns L, Wang S, Krinks M, Moos M Jr (1997) Frzb-1, an antagonist of Wnt-1 and Wnt-8, does not block signaling by Wnts -3A, -5A, or -11. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 236:502–504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lickert H, Kispert A, Kutsch S, Kemler R (2001) Expression patterns of Wnt genes in mouse gut development. Mech Dev 105:181–184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin K, Wang S, Julius MA, Kitajewski J, Moos M Jr, Luyten FP (1997) The cysteine-rich frizzled domain of Frzb-1 is required and sufficient for modulation of Wnt signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94:11196–11200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loughlin J, Dowling B, Chapman K, Marcelline L, Mustafa Z, Southam L, Ferreira A, Ciesielski C, Carson DA, Corr M (2004) Functional variants within the secreted frizzled-related protein 3 gene are associated with hip osteoarthritis in females. Proc Nat Acad Sci 101:9757–9762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsit CJ, Karagas MR, Andrew A, Liu M, Danaee H, Schned AR, Nelson HH, Kelsey KT (2005) Epigenetic inactivation of SFRP genes and TP53 alteration act jointly as markers of invasive bladder cancer. Cancer Res 65:7081–7085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBride HJ, Fatke B, Fraser SE (2003) Wnt signaling components in the chicken intestinal tract. Dev Biol 256:18–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Person AD, Garriock RJ, Krieg PA, Runyan RB, Klewer SE (2005) Frzb modulates Wnt-9a-mediated beta-catenin signaling during avian atrioventricular cardiac cushion development. Dev Biol 278:35–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philipson L (1998) Cell cycle exit: growth arrest, apoptosis, and tumor suppression revisited. Mol Med 4:205–213 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roder DM (2002) The epidemiology of gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer 5(Suppl 1):5–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohatgi PR, Yao JC, Hess K, Schnirer I, Rashid A, Mansfield PF (2006) Outcome of gastric cancer patients after successful gastrectomy: influence of the type of recurrence and histology on survival. Cancer 107:2576–2580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitoh T, Katoh M (2002) Expression and regulation of WNT5A and WNT5B in human cancer: up-regulation of WNT5A by TNFalpha in MKN45 cells and up-regulation of WNT5B by beta-estradiol in MCF-7 cells. Int J Mol Med 10:345–349 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider VA, Mercola M (2001) Wnt antagonism initiates cardiogenesis in Xenopus laevis. Genes Dev 15:304–315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidensticker MJ, (2000) Biochemical interactions in the wnt pathway. Biochim Biophys Acta 1495:168–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y, Zhai H, Wang X, Han Z, Liu C, Lan M, Du J, Guo C, Zhang Y, Wu K, Fan D (2004) Ribosomal proteins S13 and L23 promote multidrug resistance in gastric cancer cells by suppressing drug-induced apoptosis. Exp cell Res 296:337–346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokol S (2000) A role for Wnts in morpho-genesis and tissue polarity. Nat Cell Biol 2:E124–E125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suh E, Traber PG (1996) An intestine-specific homeobox gene regulates proliferation and differentiation. Mol Cell Biol 16:619–625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki H, Itoh F, Toyota M, Kikuchi T, Kakiuchi H, Hinoda Y, Imai K (1999) Distinct methylation pattern and microsatellite instability in sporadic gastric cancer. Int J Cancer 83:309–313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki H, Watkins DN, Jair KW, Schuebel KE, Markowitz SD, Chen WD, Pretlow TP, Yang B, Akiyama Y, Van Engeland M, Toyota M, Tokino T, Hinoda Y, Imai K, Herman JG, Baylin SB (2004) Epigenetic inactivation of SFRP genes allows constitutive WNT signaling in colorectal cancer. Nat Genet 36:417–422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura G, Kihana T, Nomura K, Terada M, Sugimura T, Hirohashi S (1991) Detection of frequent p53 gene mutations in primary gastric cancer by cell sorting and polymerase chain reaction single-strand conformation polymorphism analysis. Cancer Res 51:3056–3058 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The World Health Report (1997) Conquering suffering enriching humanity. World Health Organization, Geneva [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu SP, Jiang XH, Lin MC, Cui JT, Yang Y, Lum CT, Zou B, Zhu YB, Jiang SH, Wong WM, Chan AO, Yuen MF, Lam SK, Kung HF, Wong BC (2003) Suppression of survivin expression inhibits in vivo tumorigenicity and angiogenesis in gastric cancer. Cancer Res 63:7724–7732 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wada N, Kawakami Y, Ladher R, Francis-West PH, Nohno T (1999) Involvement of Frzb-1 in mesenchymal condensation and cartilage differentiation in the chick limb bud. Int J Dev Biol 43:495–500 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Krinks M, Lin K, Luyten FP, Moos M Jr (1997) Frzb, a secreted protein expressed in the Spemann organizer, binds and inhibits Wnt-8. Cell 88:757–766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei D, Gong W, Kanai M, Schlunk C, Wang L, Yao JC, Wu TT, Huang S, Xie K (2005a) Drastic down-regulation of Kruppel-like factor 4 expression is critical in human gastric cancer development and progression. Cancer Res 65:2746–2754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei D, Gong W, Oh SC, Li Q, Kim WD, Wang L, Le X, Yao J, Wu TT, Huang S, Xie K (2005b) Loss of RUNX3 expression significantly affects the clinical outcome of gastric cancer patients and its restoration causes drastic suppression of tumor growth and metastasis. Cancer Res 65:4809–4816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitfield ML, Sherlock G, Saldanha AJ, Murray JI, Ball CA, Alexander KE, Matese JC, Perou CM, Hurt MM, Brown PO, Botstein D (2002) Identification of genes periodically expressed in the human cell cycle and their expression in tumors. Mol Biol Cell 13:1977–2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittekind Ch, Sobin LH (2002) TNM classification of malignant tumours, 6th edn. Wiley-Liss, New York [Google Scholar]

- Zi X, Guo Y, Simoneau AR, Hope C, Xie J, Holcombe RF, Hoang BH (2005) Expression of Frzb/secreted Frizzled-related protein 3, a secreted Wnt antagonist, in human androgen-independent prostate cancer PC-3 cells suppresses tumor growth and cellular invasiveness. Cancer Res 65:9762–9770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]