Abstract

Purpose

Mucosal iodine staining has improved the detection of precancerous lesions of the esophagus. However, this method is unable to exactly evaluate the risk status of the lesions. In the present study, we conducted a molecular analysis combining the iodine staining in esophageal squamous cell carcinomas (ESCC) and different premalignant lesions of the esophagus in order to improve the early diagnosis of ESCC.

Methods

Tumorous and precancerous lesions were procured as iodine-unstained areas in the resected specimens of ESCC patients by means of Lugol’s iodine staining. Loss of heterozygosity (LOH) was detected with 35 microsatellite markers frequently reported to be deleted in ESCC. The markers with high frequency of LOH in tumorous and precancerous lesions of the same patient were subjected to further detection in iodine-unstained biopsy samples from the population screening in ESCC high-incidence region.

Results

Common alterations were observed at D3S3644, D3S1768, D3S3040, D3S4542, RPL14, D9S169, D13S171 and D13S263 in both cancer tissues and precancerous lesions around tumors. Interestingly, D3S3644, D3S1768, D3S3040, D3S4542, RPL14 and D13S263 were also found with high frequency of LOH in iodine-staining abnormal lesions from the population screening. Most importantly, LOH frequency increased with histological severity.

Conclusion

Our data suggest that detection of these six markers in combination with iodine staining might contribute to the prediction for the risk of ESCC development and for the diagnosis of patients in preclinical and preneoplastic phase of the disease.

Keywords: Biomarker, Esophageal cancer, Iodine-staining, Prediction, Loss of heterozygosity

Introduction

Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) exhibits some of the most malignant characteristics among gastrointestinal tumors. The prognosis of patients with ESCC remains unsatisfactory, but the cases with early ESCC present the 5-year survival rate of 56.7–84.1% (Holscher et al. 1995; Natsugoe et al. 1999; Sugimachi et al. 1989; Wang 2001). The detection of early ESCC, especially the identification of the risk of ESCC in patients with dysplastic lesions, seems the most promising way to combat the relatively poor survival rates.

The progression of ESCC correlates with a phenotypic spectrum including esophagitis, basal cell hyperplasia (BCH), squamous dysplasia, cancer in situ, invasive cancer and metastatic cancer. Histologically proven squamous dysplasia could be considered as premalignant lesions of esophageal cancer. Dysplasia with higher grades was associated with a significantly increased risk of developing esophageal cancer. It has been reported that 24% of patients with mild dysplasia, 50% with moderate dysplasia and 74% with severe dysplasia developed ESCC during 13.5 years (Wang et al. 2005). The current evaluation of the risk of ESCC in dysplastic patients is based on the histopathological grade of lesions, and patients with mild and moderate dysplasia could be given a 5- or 3-year follow up (Dong et al. 2002), that will probably lead some patients to miss the best chance for therapy. It is important to find accurate methods to estimate the possibility of developing cancer from dysplastic lesions.

Dysplastic lesions can be detected in resected samples of esophageal cancer especially if esophageal mucosa is sprayed with iodine (Nakanishi et al. 1998). However, the method of iodine staining presents some false positive results and not all the dysplastic lesions progress to cancer. The criterion for judging the malignant potential of lesions is based mainly on the degree of dysplasia. Histopathological stage assignment alone does not exactly predict malignant potential, especially in mild dysplasia. More reliable predictive tests need to be developed.

A central dogma of carcinogenesis is that alteration to critical control genes underlies malignant transformation. Changes of some tumor suppressor genes (TSGs) may play a role in the development of ESCC. A number of studies have been undertaken to identify altered TSGs by using microsatellite analysis for loss of heterozygosity (LOH) in the ESCC. Frequent LOH has been detected at some chromosomal locations including 2q, 3p, 4p, 4q, 5q, 6q, 8p, 9p, 9q, 11p, 13q, 14q, 15q and 17p (Hu et al. 2000; Huang et al. 2002; Li et al. 2004). If these changes also appeared in dysplasia, they could be used for early detection of ESCC.

We detected LOH of 35 different microsatellite markers on 3p, 5p, 9p and 13q chromosomal locations in six different categories of esophageal lesions: hyperplasia without atypia, esophagitis, mild dysplasia, moderate dysplasia, severe dysplasia/CIS and invasive tumor from esophagectomy specimens of 36 ESCC patients. Markers with a high frequency of LOH in invasive cancer and dysplastic lesions were further assessed in iodine-unstained esophageal epithelia from population screening in ESCC high-incidence regions.

Materials and methods

Specimen collection and processing

Thirty-six patients (25 males and 11 females) who underwent esophagectomy for ESCC were selected in the study from the Linzhou Cancer Hospital, HeNan Province, China from October to December 2003. A 3-ml sample of venous blood was drawn from each patient before surgery, stored in EDTA-K2 tubes and kept at −20°C until use. The resected specimen obtained during surgery was stained for two minutes with 1.25% Lugol’s iodine containing 6.25 g iodine and 12.5 g potassium iodine in 500 ml solution. Normal-stained esophageal epithelia, small areas unstained by Lugol’s iodine and tumor tissues were taken, respectively. For population screening in ESCC high-incidence regions, iodine staining for esophageal mucous membrane was used in all subjects (Nakanishi et al. 1998). From unstained foci, multiple biopsies were sampled, and normal epithelia were taken as control (Fig. 1). Forty-seven biopsy specimens from population screening by chromoendoscopy were enrolled. A part of each specimen was alcohol-fixed and paraffin-embedded for histopathological diagnosis by the criteria described previously (Dawsey et al. 1994a, b) All the patients received no therapy before surgery or screening, and signed informed consent forms for sampling. Data were recorded concerning the clinical/pathological parameters of tumors.

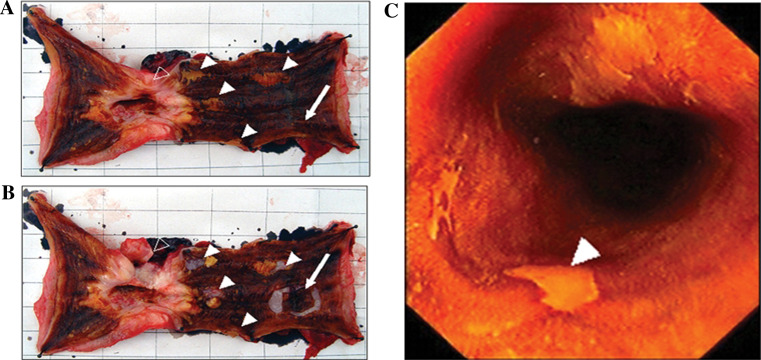

Fig. 1.

a Iodine-unstained areas before taking samples from resected specimen. b Iodine-unstained areas after taking samples from resected specimen. c Position of biopsy under the endoscope from population screening in the ESCC high-incidence region. open arrows tumor tissues; filled arrows iodine-unstained areas; arrows normally iodine-stained areas

DNA extraction

The tissues were digested with 50 mg/ml proteinase K in 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate for 14 h at 50°C, and extracted twice with phenol/chloroform. DNA was precipitated with 1/10 volumes of 3 M sodium acetate and two volumes of cold ethanol. Control DNA was extracted from venous blood and subjected to purification as described above. To ensure the DNA integrity, all samples were analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis.

Microsatellite markers and analysis

Thirty-five microsatellite markers, which had been reported with a high frequency LOH in previous ESCC studies (Hu et al. 2000; Huang et al. 2002; Li et al. 2004), were selected in this study. The information about marker position, heterozygosity rate and primers of PCR are shown in Table 1. Forty ng DNA was used as template in 20 μl of PCR reactions. Amplifications were performed in a GeneAmp PCR system 2400 thermal cycler (Perkin-Elmer). In each PCR reaction, after 94°C for 5 min, the mixtures were subjected to 35 cycles; each cycle consisted of 94°C for 30 s, 58–61°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s. There was a single final extension at 72°C for 5 min. An aliquot of 2-μl PCR product was mixed with equal volume of loading buffer (98% formamide, 20 mM EDTA, 0.05% bromophenol blue, and 0.05% xylene cyanol), denatured for 10 min at 95°C, and chilled on ice until loaded onto a denaturing 7% urea–polyacrylamide–formamide gel containing 64% formamide, 7 M urea. Samples were electrophoresed at constant 60 W, 1,500 V, 80 mA for 1–3 h. The results were visualized by silver staining.

Table 1.

Characteristics of microsatellite markers

| Marker | tHet | Ta (°C) | Size range (bp) | Site | Position (Kb) | CA strand primer | GT strand primer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAGR1 | – | 59 | 125 | 13q13 | 30037 | AAGCACCTGGTACTAAGGGTA | TCGCGGCGGTGATCTTTTTTG |

| D13S260 | 0.77 | 59 | 158–173 | 13q12.3 | 30234 | AGATATTGTCTCCGTTCCATGA | CCCAGATATAAGGACCTGGCTA |

| D13S1493 | – | 60 | 223–248 | 13q12.3 | 31806 | ACCTGTTGTATGGCAGCAGT | GGTTGACTCTTTCCCCAACT |

| D13S267 | 0.68 | 52 | 148–162 | 13q12.3 | 32062 | GGCCTGAAAGGTATCCTC | TCCCACCATAAGCACAAG |

| D13S171 | 0.73 | 54 | 227–241 | 13q14 | 32152 | CCTACCATTGACACTCTCAG | TAGGGCCATCCATTCT |

| D13S220 | 0.67 | 52 | 191–203 | 13q12.3-q13 | 32967 | CCAACATCGGGAACTG | TGCATTCTTTAAGTCCATGTC |

| D13S219 | 0.64 | 57 | 117–127 | 13q12.3-q13 | 34956 | AAGCAAATATGCAAAATTGC | TCCTTCTGTTTCTTGACTTAACA |

| D13S894 | 0.7 | 56 | 180–200 | 13q12.3-q14.2 | 36536 | GGTGCTTGCTGTAAATATAATTG | CACTACAGCAGATTGCACCA |

| D13S263 | 0.84 | 60 | 145–165 | 13q14.1 | 40979 | CCTGGCCTGTTAGTTTTTATTGTTA | CCCAGTCTTGGGTATGTTTTTA |

| D13S126 | 0.67 | 55 | 100 | 13q14.3 | 45108 | TCACCAGTAAAATGCTATTGG | GTGATTTTCAAATTTGCTCTG |

| D13S168 | 0.77 | 53 | 173–197 | 13q14.3 | 45609 | GCCTAGCCCAGTGGTG | TGCTTGTGCCTATGTTCTTG |

| D13S153 | 0.82 | 58 | 212–236 | 13q14.1-q14.3 | 46688 | AGCATTGTTTCATGTTGGTG | CAGCAGTGAAGGTCTAAGCC |

| D13S272 | 0.66 | 60 | 131–143 | 13q14.3 | 48504 | ATACAGACTTCCCAGTGGCT | AGCTATTAAAGTTCCCTGGATAAAT |

| D13S152 | 0.78 | 58 | 133–143 | 13q21.3-q22 | 71232 | CACATAGGCAACATAGGCAC | TCTGTATTCGCTTTCCCTG |

| D13S770 | – | 57 | 234–258 | 13q32-13q32 | 97329 | GCTGTGACTTTTAGGCCAAA | TGTGATGTCTACAACTCCAGG |

| D13S248 | 0.833 | 50 | 214 | 13q32-13q34 | 105318 | ACTTAAATGTCCATCAATAAAT | TGATTGGCTTTTTTTACTTAC |

| D3S1285 | 0.736 | 62 | 173−215 | 3p14.2-3p14.1 | 24163 | ATTTAGAAAACCCATACAGCATGGC | TCTGTTCATCACAGGGGTAGCATC |

| MICA | 0.75 | 55 | 179–196 | 3p21.3 | 31484 | CCTTTTTTTAGGGAAAGTGC | CCTTACCATCTCCAGAAACTGC |

| D3S2432 | 0.774 | 59 | 118–170 | 3p24.2-3p22 | 31534 | GGCAGGCAGGTAGATAGACA | ACACTAAACA |

| D3S1768 | 0.740 | 53 | 186–206 | 3p23 | 34599 | GGTTGCTGCCAAAGATTAGA | CACTGTGATTTGCTGTTGGA |

| D3S1611 | 0.857 | 58 | 252–268 | 3p22.3 | 37044 | CCCCAAGGCTGCACTT | AGCTGAGACTACAGGCATTTG |

| RPL14 | – | 59 | 140 | 3p22-p21.2 | 40473 | AAGCACCTGGTACTAAGGGTA | TCGCGGCGGTGATCTTTTTTG |

| D3S2452 | 0.642 | 58 | 150–166 | 3p21.1-3p14.2 | 58067 | GCTTGCAGATAGCAGATCGT | TATAAGATTAGTCAGGGCTCGC |

| D3S1766 | 0.727 | 55 | 208–232 | 3p21.1-3p14.2 | 58350 | ACCACATGAGCCAATTCTGT | ACCCAATTATGGTGTTGTTACC |

| D3S3040 | 0.607 | 57 | 212–213 | 3p14.3 | 58957 | AAGGCCTTCAGACTCAACCT | TTAATCTGGGCTCTCCAGAG |

| D3S4542 | 0.684 | 53 | 236–260 | 3p14.1-3p14.2 | 63895 | TCCAGAGAAACAGAACCGAC | TGCAGATTTTGGACTTGTCA |

| D3S3571 | 0.92 | 57 | 216–275 | 3pter-3qter | 64340 | CTGAGGCTCTGCAATGTTTAG | CAGGCAAGGTTATCTGGG |

| D3S3644 | 0.644 | 60 | 164–176 | 3p14.1-3p14.2 | 64731 | ATGGGGGCTCTATGGCTTATCA | GCTCAAATGCTCAAAAAGTAGCACC |

| D3S2329 | 0.86 | 53 | 399 | 3p14.2-p14.1 | 64981 | AGCTGAAGAGTATTCCATAG | GTCTATCAATGGATAATTGGA |

| D5S1384 | 0.75 | 61 | 145 | 5pter-5qter | 118906 | CTAAACAGAAAAGAGCTAAGCCTA | TACCTACCTATATGCTCCCAATC |

| D5S592 | 0.86 | 56 | 145–175 | 5pter-5qter | 119177 | AGACAGACAGAGAGATTAGA | AGTAAAGTGAGTGGAGAGC |

| D9S157 | 0.849 | 64 | 133–149 | 9p22.1 | 17867 | AGCAAGGCAAGCCACATTTC | TGGGGATGCCCAGATAACTATATC |

| D9S169 | 0.838 | 63 | 259–275 | 9p21.2 | 27229 | AGAGACAGATCCAGATCCCA | TAACAACTCACTGATTATTTAAGGC |

| D9S161 | 0.782 | 61 | 119–135 | 9p13.3 | 27801 | TGCTGCATAACAAATTACCAC | CATGCCTAGACTCCTGATCC |

| D9S165 | 0.76 | 60 | 238 | 9p21-9q21 | 33163 | GACTTTGGCTGCTAGATGTG | CAGAGGAGTTACAAATATAGACAGG |

tHet theoretical heterozygosity, Ta temperature of annealing, – no information available

The cases with control samples showing two alleles in the gel were defined as informative. As compared with the corresponding allele in the matching control DNA, LOH was inferred when the intensity of one allele was decreased by at least 50%. Microsatellite instability (MSI) was defined as alteration of length of an allele or presence of extra allele in the DNA sample from esophageal lesion. Two reviewers independently read the results. All positives identified by either of the two initial readers were confirmed by a third reader.

The frequency of LOH was calculated as the number of cases with LOH divided by the number of informative cases at the same locus. For the esophagectomy patients, if several iodine-unstained loci of esophageal mucosa were diagnosed as the same kind of lesions and one or more of them showed LOH in one specimen, the case was counted as LOH of this kind of lesion. In a clinical view, mild and moderate dysplastic lesions were always given a follow-up process, and severe dysplastic lesions were always given an ablative treatment. In this study, we classified mild and moderate dysplastic lesions into the low-grade dysplasia and severe dysplastic lesions into the high-grade dysplasia. The frequency of LOH was compared in different lesions by The χ2 or Fisher’s exact test.

Results

Summary of histological diagnoses

From 36 patients with esophagectomy, 122 iodine-unstained areas were found, including 56 normal esophageal epithelia, 14 esophagitis, 12 basal cell hyperplasia (BCH), 15 mild dysplasia, 12 moderate dysplasia and 13 severe dysplasia in addition to tumors and normally iodine-stained tissues (Table 2).

Table 2.

Histopathology diagnosis of samples in the resected specimens of ESCC patients

| Cases | Sex | Age | Iodine-stained | Iodine-unstained | Tumor | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | N* | ES | BCH | mD | MD | SD | ||||

| S1 | M | 63 | 1 | 3 | 1 | |||||

| S2 | M | 48 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| S3 | M | 70 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| S4 | M | 63 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| S5 | F | 47 | 1 | 3 | 1 | |||||

| S6 | F | 54 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| S7 | M | 70 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 1 | ||||

| S8 | M | 73 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| S9 | M | 49 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 1 | ||||

| S10 | M | 53 | 1 | 2 | 1 | |||||

| S11 | M | 53 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| S12 | M | 66 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | |||

| S13 | F | 59 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| S14 | M | 46 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| S15 | M | 48 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| S16 | F | 65 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| S17 | M | 52 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | ||

| S18 | F | 63 | 1 | 4 | 1 | |||||

| S19 | M | 62 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| S20 | M | 59 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| S21 | F | 69 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| S22 | F | 59 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | |||

| S23 | M | 78 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| S24 | M | 60 | 1 | 4 | 1 | |||||

| S25 | F | 52 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | ||||

| S26 | F | 61 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 1 | |||

| S27 | M | 54 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| S28 | M | 55 | 1 | 3 | 1 | |||||

| S29 | M | 51 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| S30 | M | 62 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | |||

| S31 | F | 63 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| S32 | M | 49 | 1 | 2 | 1 | |||||

| S33 | M | 53 | 1 | 2 | 1 | |||||

| S34 | M | 54 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | |||

| S35 | F | 55 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | ||||

| S36 | M | 51 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Total | 36 | 56 | 14 | 12 | 15 | 12 | 13 | 36 | ||

N iodine-stained normal esophageal mucosa, N* histopathologically normal esophageal mucosa unstained by iodine, ES esophagitis, BCH basal cell hyperplasia, mD mild dysplasia, MD moderate dysplasia, SD severe dysplasia, EC esophageal cancer

Forty-seven biopsy tissues from the iodine-unstained foci of patients in endoscopy examination in ESCC high-incidence region were diagnosed as 16 normal esophageal epithelia, 3 esophagitis, 2 basal cell hyperplasia (BCH), 8 mild dysplasia, 11 moderate dysplasia and 7 severe dysplasia (Table 3).

Table 3.

Histopathology diagnosis of samples from the high-risk region of ESCC

| Cases | Sex | Age | Diagnoses | Cases | Sex | Age | Diagnoses |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B1 | M | 41 | N* | B25 | F | 52 | ES |

| B2 | M | 37 | mD | B26 | F | 65 | SD |

| B3 | F | 61 | N* | B27 | M | 56 | N* |

| B4 | F | 47 | MD | B28 | F | 60 | MD |

| B5 | M | 61 | mD | B29 | M | 63 | N* |

| B6 | F | 53 | N* | B30 | M | 66 | BCH |

| B7 | F | 62 | N* | B31 | M | 41 | N* |

| B8 | F | 46 | N* | B32 | F | 56 | N* |

| B9 | M | 57 | mD | B33 | M | 51 | SD |

| B10 | M | 56 | N* | B34 | M | 53 | MD |

| B11 | F | 45 | N* | B35 | M | 61 | SD |

| B12 | M | 53 | mD | B36 | F | 47 | MD |

| B13 | M | 78 | N* | B37 | M | 51 | MD |

| B14 | F | 73 | mD | B38 | M | 48 | mD |

| B15 | F | 51 | ES | B39 | M | 59 | SD |

| B16 | F | 50 | mD | B40 | M | 57 | MD |

| B17 | M | 69 | N* | B41 | M | 43 | MD |

| B18 | F | 55 | MD | B42 | F | 59 | BCH |

| B19 | M | 59 | ES | B43 | F | 60 | SD |

| B20 | F | 56 | N* | B44 | M | 48 | MD |

| B21 | M | 50 | MD | B45 | M | 54 | MD |

| B22 | F | 47 | SD | B46 | M | 66 | mD |

| B23 | M | 70 | N* | B47 | M | 48 | SD |

| B24 | M | 63 | N* |

N* histopathologically normal esophageal mucosa unstained by iodine, ES esophagitis, BCH basal cell hyperplasia, mD mild dysplasia, MD moderate dysplasia, SD severe dysplasia, EC esophageal cancer

Frequency of LOH in esophagectomy specimens

In the 35 markers tested, D3S1768, D3S3040, D3S3644, D3S4542, RPL14, D9S169, D13S171 and D13S263 presented high frequency of LOH in tumor tissues (Fig. 2). LOH at one or more of the eight loci was detected in 28/36 (78%) tumors, 7/8 (87.5%) high-grade dysplasia (HGD) and 8/19 (42%) low-grade dysplasia (LGD). Frequency of LOH increased from low-grade dysplasia to ESCC: 25% in LGD, 57% in HGD, and 64% in ESCC (Table 4). The difference between LGD and HGD was statistically significant (χ2 test, P < 0.05).

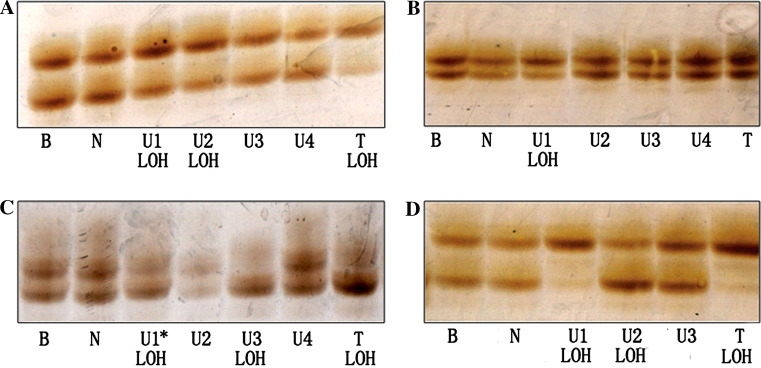

Fig. 2.

Cases with different LOH patterns. a LOH of D3S3040 in case S25, loss of the lower allele in U1, U2 and T. b LOH of D3S3040 in case S30, loss of the lower allele in U1. c LOH of D3S3040 in case S21, showing loss of the lower allele in U1, U3 and T. Note, U1 is histopathologically normal iodine-unstained tissue. d LOH of D3S3040 in case S29, D3S3040 showing loss of the lower allele in U1 and T, whereas U2 with loss of the upper allele. B blood DNA; N normally iodine-stained mucosa; U iodine-unstained mucosa. T tumor tissue

Table 4.

Frequency of LOH in specimens of esophagectomy

| Pathological diagnosis | USL lesions | LOH in USL (%) | EC (%) | LOH in both EC and USL (%*) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal* (%) | ES (%) | BCH (%) | mD+MD (%) | SD (%) | ||||

| RPL14 | 2/15/26 (13) | 0/2/8 (0) | 0/2/8 (0) | 4/12/19 (33) | 3/4/8 (75) | 8/22/36 (36) | 11/22/36 (50) | 6/22/36 (55) |

| D321768 | 5/23/26 (22) | 2/6/8 (33) | 0/6/8 (0) | 6/15/19 (28) | 5/5/8 (100) | 14/29/36 (48) | 21/29/36 (72) | 12/29/36 (57) |

| D3S3040 | 7/20/26 (35) | 3/5/8 (60) | 0/6/8 (0) | 3/16/19 (18.8) | 5/7/8 (71) | 13/29/36 (46) | 20/29/36 (69) | 11/29/36 (55) |

| D3S4542 | 6/22/26 (27) | 2/4/8 (50) | 0/6/8 (0) | 5/14/19 (38) | 5/6/8 (83) | 14/28/36 (50) | 19/28/36 (67) | 9/28/36 (47) |

| D3S3644 | 3/15/26 (20) | 0/3/8 (0) | 0/3/8 (0) | 3/12/19 (25) | 3/4/8 (75) | 8/21/36 (40) | 16/21/36 (76) | 7/21/36 (44) |

| D9S169 | 2/22/26 (9) | 0/4/8 (0) | 0/6/8 (0) | 2/14/19 (14.3) | 1/6/8 (17) | 5/28/36 (18) | 19/28/36 (68) | 4/28/36 (21) |

| D13S171 | 1/12/26 (8.3) | 1/4/8 (25) | 0/5/8 (0) | 2/14/19 (14.3) | 1/5/8 (20) | 5/21/36 (24) | 13/21/36 (62) | 3/21/36 (23) |

| D13S263 | 2/18/26 (11) | 1/6/8 (17) | 1/7/8 (14) | 3/13/19 (23) | 2/5/8 (40) | 7/25/36 (28) | 12/25/36 (48) | 5/25/36 (38) |

| Total | 28/147 (19) | 9/34 (26) | 1/41 (2.4) | 28/110 (25) | 24/42 (57) | 130/203 (64) | ||

Normal* histopathologically normal esophageal mucosa unstained by iodine, ES esophagitis, BCH basal cell hyperplasia, mD mild dysplasia, MD moderate dysplasia, SD severe dysplasia, EC esophageal cancer, %* = number of case of LOH in both tumor and usl/number of case of LOH in the tumor, USL unstained of logul’s iodine

All the histopathologically normal iodine-stained epithelia showed no LOH at any locus, but 10/26 (38%) histopathologically normal iodine-unstained epithelia, 5/8 (62.5%) esophagitis and 1/8 (12.5%) BCH showed LOH in at least one of the eight markers. Frequency of LOH in histopathologically normal iodine-unstained epithelia, esophagitis and BCH is 19, 26 and 2.4%, respectively. There was no statistical difference between these three types of lesions.

Frequency of LOH in the biopsy specimens of ESCC high-incidence region

We performed further investigation of six of the above eight markers in biopsy samples from the population screening. Frequency of LOH increased with disease severity of lesions (Fig. 3 and Tables 5, 6). Coexistence of LOH in several markers was observed in some cases, especially in histopathologically normal iodine-unstained areas.

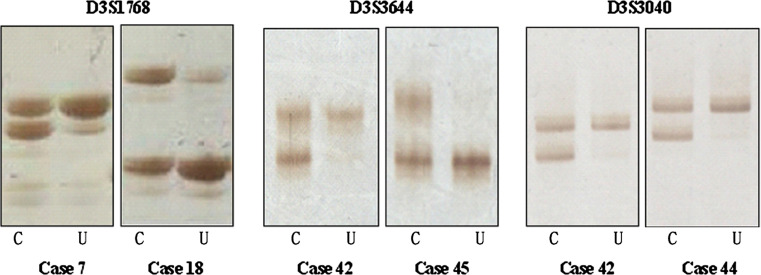

Fig. 3.

LOH in biopsy samples. C normally iodine-stained mucosa, U iodine-unstained mucosa

Table 5.

Frequency of LOH in biopsy specimens from the high-risk population screening

| Pathological diagnosis | Normal* (%) | ES (%) | BCH (%) | mD+MD (%) | SD (%) | Total (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D3S1768 | 3/14/16 (21) | 0/2/3 (0) | 1/1/1 (100) | 7/16/19 (50) | 4/6/7 (67) | 15/39/46 (38) |

| RPL14 | 3/11/15 (27) | 0/2/3 (0) | 1/1/2 (100) | 4/12/18 (43) | 2/5/7 (40) | 10/31/45 (32) |

| D3S3040 | 3/15/15 (20) | 2/3/3 (67) | 0/0/1 (0) | 4/14/19 (29) | 2/5/7 (40) | 11/37/45 (30) |

| D3S4542 | 3/12/15 (25) | 1/3/3 (33) | 1/1/2 (100) | 7/15/19 (25) | 3/7/7 (43) | 15/38/46 (39) |

| D3S3644 | 2/8/16 (25) | 2/3/3 (67) | 1/1/1 (100) | 3/11/19 (14) | 3/4/7 (75) | 11/27/46 (41) |

| D13S263 | 4/15/16 (27) | 2/2/3 (100) | 0/2/2 (0) | 4/16/19 (22) | 1/4/7 (25) | 11/39/47 (28) |

| Total | 18/75/93 (24) | 7/15/18 (47) | 4/6/9 (67) | 29/84/113 (35) | 15/31/42 (48) | 73/211/275 (35) |

N* histopathologically normal esophageal mucosa unstained by iodine, ES esophagitis, BCH basal cell hyperplasia, mD mild dysplasia, MD moderate dysplasia, SD severe dysplasia

Table 6.

LOH in different lesions of high-risk population screening

| Case | D3S1768 | RPL14 | D3S3040 | D3S4542 | D3S3644 | D13S263 | Case | D3S1768 | RPL14 | D3S3040 | D3S4542 | D3S3644 | D13S263 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B1 | × | - | • | - | × | MSI | B25 | × | × | • | • | • | • |

| B2 | ○ | ○ | ○ | × | ○ | ○ | B26 | ○ | × | ○ | ○ | × | × |

| B3 | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | B27 | • | • | • | • | × | • |

| B4 | • | × | • | × | × | ○ | B28 | • | • | × | × | × | ○ |

| B5 | • | × | • | • | • | • | B29 | × | × | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| B6 | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | × | • | B30 | - | × | - | × | - | ○ |

| B7 | • | • | ○ | • | • | ○ | B31 | ○ | ○ | - | ○ | × | × |

| B8 | ○ | ○ | ○ | × | ○ | ○ | B32 | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | × | • |

| B9 | • | ○ | ○ | • | ○ | ○ | B33 | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| B10 | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | × | ○ | B34 | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | × |

| B11 | ○ | × | ○ | ○ | × | ○ | B35 | • | • | • | • | • | × |

| B12 | ○ | • | ○ | • | × | ○ | B36 | × | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | × |

| B13 | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | B37 | × | • | • | × | × | • |

| B14 | ○ | - | ○ | ○ | × | × | B38 | ○ | ○ | × | • | • | ○ |

| B15 | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | × | B39 | • | × | × | • | × | • |

| B16 | • | ○ | • | • | × | • | B40 | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| B17 | ○ | ○ | ○ | × | ○ | ○ | B41 | • | • | × | • | ○ | • |

| B18 | • | ○ | × | • | • | ○ | B42 | • | • | × | • | • | ○ |

| B19 | ○ | ○ | • | MSI | • | • | B43 | • | ○ | • | • | • | ○ |

| B20 | ○ | × | ○ | × | ○ | ○ | B44 | ○ | × | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| B21 | ○ | × | × | ○ | × | ○ | B45 | × | × | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| B22 | • | • | × | ○ | • | × | B46 | ○ | × | ○ | ○ | × | ○ |

| B23 | ○ | × | ○ | ○ | × | ○ | B47 | × | ○ | ○ | ○ | × | ○ |

| B24 | • | • | • | • | • | • |

Open circle allelic retention, filled circle loss of heterozygosity, × noninformative, MSI microsatellite instability, N* histopathologically normal esophageal mucosa unstained by iodine, ES esophagitis, BCH basal cell hyperplasia, mD mild dysplasia, MD moderate dysplasia, SD severe dysplasia, EC esophageal cancer

Discussion

Frequent LOH on 3p, 5q, 9p and 13q has been previously observed in ESCC (Kagawa et al. 2000; Lu et al. 2003; Roth et al. 2001). ESCC may proceed through the sequence of histopathological changes in epithelia including esophagitis, BCH, mild to severe dysplasia and invasive carcinoma (Dawsey et al. 1994a, b Mandard et al. 2000). Iodine staining allowed observing various esophageal lesions. However, precancerous lesions of patients with ESCC cannot fully reflect biological behaviors of precursor lesions in the population. In the present study, we performed an analysis of 35 microsatellite markers in tumor tissues, precancerous lesions of esophagectomy specimens and biopsy samples from the population screening in ESCC high-incidence region. Our purpose is to observe consistent molecular changes in all these three types of samples in order to find candidate markers for early detection of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma.

Out of 35 microsatellite markers tested, RPL14, D3S1768, D3S3040, D3S4542, D3S3644, D9S169, D13S171 and D13S263 exhibited highly frequent LOH in tumor tissues and precancerous lesions around tumors. We did not deal with the samples by the method of microdissection as in previous studies (Lu et al. 2003; Roth et al. 2001). The samples taken from the iodine-unstained areas contained more or less normal stromal cells. Therefore, LOH frequency of these eight markers might have been underestimated. Their actual LOH frequency was probably higher than what we detected. We noted that the frequency of LOH increased with the severity of disease from low-grade dysplasia to ESCC, supporting the idea that accumulation of genetic changes is associated with the progression of normal mucosa to precancerous lesions to cancer. Although LGD presented significantly lower LOH frequency as compared with HGD, some of the LGD cases showed the same LOH pattern as that in HGD. We propose that LGD lesion with higher LOH might need to receive an ablation therapy as HGD. The management of LGD is possibly a key point for early detection of ESCC.

Further analysis was performed in iodine-unstained samples from the high-risk population screening using the markers with high LOH frequency in both tumors and precancerous lesions. We found that six markers presented frequent LOH in the iodine-unstained biopsy samples. Frequency of LOH was elevated with increasing pathological severity of lesions from histologically normal iodine-unstained epithelium to severe dysplasia, which was consistent with the observation in resected specimens.

More interestingly, the histopathologically normal iodine-stained epithelia in the resected specimens did not display genetic changes by taking the samples of venous blood as control, but LOH was observed in 19% of histopathologically normal iodine-unstained epithelia, especially in some cases LOH pattern was same as that of cancerous lesions (Fig. 2c). Furthermore, LOH was detected in 24% of histopathologically normal iodine-unstained epithelia in biopsy tissues. Some of the cases presented coexistence of LOH in at least four markers. These results suggest that combination of molecular analysis and iodine staining could contribute to early detection of precancerous lesions, especially those in normal histological phenotype.

It is worthwhile to mention that in seven resected specimens, discordant genetic alterations, i.e. changes in lost allele, were detected in different lesions from the same patient. Genetic heterogeneity has been reported in dysplasia, squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus and the oral cavity (Guo et al. 2001; Roth et al. 2001). This may be attributed to “field carcinogenesis” in the development of tumors. Lesions with different genetic changes may be on the different way of carcinogenesis and evolved into different clones. As a result of clonal divergence and selection, eventually one or more subclones develop into invasive cancer (Braakhuis et al. 2003). Detecting such subclones would probably contribute to early diagnosis of ESCC.

It has been reported that some iodine-unstained areas found in high-risk population screening were pathologically diagnosed as esophagitis, BCH and even normal squamous epithelium (Dawsey et al. 1998; Wang et al. 2003). Generally, these lesions are not counted as precancerous lesions. However, we found that some of them had LOH at more than one microsatellite locus. LOH was also reported in histologically normal epithelia of patients with lung cancer and bladder cancer. A prospective study has indicated that BCH has a similar risk of developing cancer with mild dysplasia (Wang et al. 2005). These data suggested that molecular changes have occurred in nondysplastic lesions.

In summary, some of the iodine-unstained lesions appeared normal or dysplastic under the microscope but still harbored clonal genetic changes that are necessary for cancer progression. Although the combination of iodine staining and pathological examination is a powerful method to detect cancers as well as lesions that are likely to progress to cancer, further stratification of risk with molecular markers seems reasonable for biopsy lesions. If confirmed in ongoing prospective studies, LOH analysis of the markers presented here, in combination with iodine staining, may predict the risk of ESCC development and give a diagnosis for patients in preclinical and preneoplastic phase of the disease.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by: State Key Basic Research Grant of China (2004CB518705), Specialized Research Fund of Beijing Municipal Science & Technology Commission (D0905001040331), National Natural Science Foundation (30470969, 30400207, 30328024) and Program for Changjiang Scholars and Innovative Research Team in University (IRT0416), Clinical Key subject project of Ministry of Health.

Contributor Information

Gui-Qi Wang, Phone: +86-10-87788098, FAX: +86-10-87711782, Email: wangguiq@public.bta.net.cn.

Ming-Rong Wang, Phone: +86-10-87788204, FAX: +86-10-87778651, Email: wangmr04@126.com.

References

- Braakhuis BJ, Tabor MP, Kummer JA, Leemans CR, Brakenhoff RH (2003) A genetic explanation of Slaughter’s concept of field cancerization: evidence and clinical implications. Cancer Res 63:1727–1730 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawsey SM, Lewin KJ, Liu FS, Wang GQ, Shen Q (1994a) Esophageal morphology from Linxian, China. Squamous histologic findings in 754 patients. Cancer 73:2027–2037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawsey SM, Lewin KJ, Wang GQ, Liu FS, Nieberg RK, Yu Y, Li JY, Blot WJ, Li B, Taylor PR (1994b) Squamous esophageal histology and subsequent risk of squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus. A prospective follow-up study from Linxian, China. Cancer 74:1686–1692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawsey SM, Fleischer DE, Wang GQ, Zhou B, Kidwell JA, Lu N, Lewin KJ, Roth MJ, Tio TL, Taylor PR (1998) Mucosal iodine staining improves endoscopic visualization of squamous dysplasia and squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus in Linxian, China. Cancer 83:220–231 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong Z, Tang P, Li L, Wang G (2002) The strategy for esophageal cancer control in high-risk areas of China. Jpn J Clin Oncol 32(Suppl):S10–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Z, Yamaguchi K, Sanchez-Cespedes M, Westra WH, Koch WM, Sidransky D (2001) Allelic losses in OraTest-directed biopsies of patients with prior upper aerodigestive tract malignancy. Clin Cancer Res 7:1963–1968 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holscher AH, Bollschweiler E, Schneider PM, Siewert JR (1995) Prognosis of early esophageal cancer. Comparison between adeno- and squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer 76:178–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu N, Roth MJ, Polymeropolous M, Tang ZZ, Emmert-Buck MR, Wang QH, Goldstein AM, Feng SS, Dawsey SM, Ding T, Zhuang ZP, Han XY, Ried T, Giffen C, Taylor PR (2000) Identification of novel regions of allelic loss from a genomewide scan of esophageal squamous-cell carcinoma in a high-risk chinese population. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 27:217–228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang XP, Wei F, Liu XY, Xu X, Hu H, Chen BS, Xia SH, Han YS, Han YL, Cai Y, Wu M, Wang MR (2002) Allelic loss on 13q in esophageal squamous cell carcinomas from northern China. Cancer Lett 185:87–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagawa Y, Yoshida K, Hirai T, Toge T, Yokozaki H, Yasui W, Tahara E (2000) Microsatellite instability in squamous cell carcinomas and dysplasias of the esophagus. Anticancer Res 20:213–217 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li XD, Huang XP, Zhao CX, Li QJ, Xu X, Cai Y, Han YL, Rong TH, Wang MR (2004) Identification of a minimal deletion region on chromosome 5q in Chinese esophageal squamous cell carcinomas. Cancer Lett 215:221–228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu N, Hu N, Li WJ, Roth MJ, Wang C, Su H, Wang QH, Taylor PR, Dawsey SM (2003) Microsatellite alterations in esophageal dysplasia and squamous cell carcinoma from laser capture microdissected endoscopic biopsies. Cancer Lett 189:137–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandard AM, Hainaut P, Hollstein M (2000) Genetic steps in the development of squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus. Mutat Res 462:335–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakanishi Y, Ochiai A, Yoshimura K, Kato H, Shimoda T, Yamaguchi H, Tachimori Y, Watanabe H, Hirohashi S (1998) The clinicopathologic significance of small areas unstained by Lugol’s iodine in the mucosa surrounding resected esophageal carcinoma: an analysis of 147 cases. Cancer 82:1454–1459 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natsugoe S, Baba M, Shimada M, Kijima F, Kusano C, Yoshinaka H, Mueller J, Aikou T (1999) Positive impact on surgical treatment for asymptomatic patients with esophageal carcinoma. Hepatogastroenterology 46:2854–2858 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth MJ, Hu N, Emmert-Buck MR, Wang QH, Dawsey SM, Li G, Guo WJ, Zhang YZ, Taylor PR (2001) Genetic progression and heterogeneity associated with the development of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Res 61:4098–4104 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugimachi K, Ohno S, Matsuda H, Mori M, Matsuoka H, Kuwano H (1989) Clinicopathologic study of early stage esophageal carcinoma. Surgery 105:706–710 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang GQ (2001) 30-year experiences on early detection and treatment of esophageal cancer in high risk areas. Zhongguo Yi Xue Ke Xue Yuan Xue Bao 23:69–72 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang GQ, Abnet CC, Shen Q, Lewin KJ, Sun XD, Roth MJ, Qiao YL, Mark SD, Dong ZW, Taylor PR, Dawsey SM (2005) Histological precursors of oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma: results from a 13 year prospective follow up study in a high risk population. Gut 54:187–192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang GQ, Wei WQ, Lu N, Hao CQ, Lin DM, Zhang HT, Sun YT, Qiao YL, Wang GQ, Dong ZW (2003) Significance of screening by iodine staining of endoscopic examination in the area of high incidence of esophageal carcinoma. Ai Zheng 22:175–177 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]