Abstract

Purpose and methods

Loss of heterozygosity (LOH) in a chromosomal location indicates the presence of an inactivated tumor suppressor gene (TSG). Inactivation of TSG has a functional role in the tumorigenesis of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC). Based on the recent evidences of a putative TSG on chromosome 14, we examined LOH on chromosome 14q using eight polymorphic microsatellite markers in 50 cases of HNSCCs.

Results

Three regions were detected to have a high LOH rate which included 14q21.2-22.3 (42.5%), 14q31 (55%), and 14q32.1 (37%). The correlation between LOH and clinicopathological findings was investigated through statistical analyses. A strong correlation was observed between the highest LOH marker and the overall and disease-free survival.

Conclusions

The results suggest that the distal part of chromosome 14 may host a TSG that may lead to the development and/or progression of HNSCCs. Several genes such as CHES1, BMP4, SAV, and PNN have arisen as candidate tumor suppressors in the region.

Keywords: Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, Loss of heterozygosity, 14q, Microsatellite marker, Survival, D14S995, D14S67

Introduction

Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) is one of the most frequent cancers that lead to death, making it a major health problem in the world. HNSCC includes oral, oro/nasopharyngeal and laryngeal cancers and accounts for more than 644,000 new cases worldwide, with a mortality of 0.53 and a male predominance of 3:1 (Parkin et al. 2005). Despite advanced technology in the detection and treatment of HNSCC, it continues to pose a great threat for human life. Most patients suffering from this malignancy are at an advanced stage upon diagnosis in which 51% present regional metastasis and 10% with distant metastasis. The 5-year relative survival rate with regional metastasis is about 51% and with distant metastases is 28% (Jemal et al. 2006).

Loss of heterozygosity (LOH) is considered an indication of the presence of a tumor suppressor gene (TSG), where inactivation contributes to the development and/or progression of tumor (Croce 1991). Detailed LOH analysis of polymorphic loci distributed along a chromosome can reveal a common minimal deleted region where putative TSGs may reside.

LOH in HNSCC have shown frequent allelic losses on chromosome 2q, 3p, 8p, 9p, 12q, 7q, 13q, 17p, and 22q and these regions correlated with the prognosis of cancer (Li et al. 1994; Lydiatt et al. 1998; Ransom et al. 1998; Gunduz et al. 2000, 2002, 2005; Cengiz et al. 2007). We previously performed a comprehensive genome-wide LOH analysis in HNSCC using about 200 polymorphic microsatellite markers. Aside from the hot spots (3p, 9p, 13q, 15q, 17p), high LOH was detected on chromosome 14 (Beder et al. 2003). Moreover, various cancer types including neuroblastoma, meningioma, renal cell carcinoma, hepatocellular carcinoma, and colorectal carcinoma showed high LOH on chromosome 14 (14q11-12, 14q23 and 14q31-32) (Simon et al. 1995; Herbers et al. 1997; Piao et al. 1998; Bando et al. 1999). Thus, in the present study, we aimed to analyze in detail the LOH status in frequently deleted regions on chromosome 14 to determine novel putative TSG of this region in HNSCC. Furthermore, LOH status was correlated with the clinicopathological findings.

Materials and methods

Patients and samples

Samples obtained from 1994 to 2005 at the Department of Otolaryngology, Okayama University Hospital, were included in the study after acquisition of informed consent from each patient. Fifty pairs of normal and primary HNSCC samples were used. All tissues were frozen in liquid nitrogen immediately after surgery and stored at −80°C until the extraction of DNA. Histopathological examinations were performed at the Department of Pathology and all tumors were diagnosed as squamous cell carcinoma. The institutional review board approved the study.

DNA extraction

Genomic DNAs were isolated from frozen tissues by SDS/proteinase K treatment, phenol–chloroform extraction, and ethanol precipitation as previously described (Gunduz et al. 2000, 2002).

Microsatellite analysis

DNAs from matched pairs of normal and tumor samples were analyzed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based deletion mapping using eight polymorphic markers in the long arm of chromosome 14 (Table 1). PCR was carried out in 20 μl of reaction mixture with 20 pmol of each primer, 100 ng of genomic DNA, 10× PCR buffer, 200 mM of each deoxynucleotide triphosphate, and 0.5 unit of rTaq DNA polymerase (Takara, Kyoto, Japan). Initial denaturation step at 94°C for 3 min was followed by 25 cycles of denaturation step at 94°C for 30 s, an annealing step at 56°C (D14S980), 58°C (D14S67, D14S1046, D14S990), 60°C (D14S65, D14S1142) and 63°C (D14S995, D14S1048) for 30 s, and an extension step at 72°C for 1 min. A final extension step at 72°C for 7 min was added. The size of each PCR product was first confirmed in agarose gel electrophoresis. Wherever the PCR failed or was doubtful, the reaction was repeated. After amplification, 2–4 μl of the reaction mixture was mixed with 8 μl loading dye (95% formamide, 20 mM EDTA, 0.05% bromophenol blue, and 0.05% xylene cyanole), heat denatured, chilled on ice, and then electrophoresed in 8% polyacrylamide gel containing 8 M urea. Then, DNA bands were visualized by silver nitrate staining as previously described (Gunduz et al. 2000, 2002).

Table 1.

Microsatellite markers used in LOH analysis

| Microsatellite | Chromosomal location | Maximum heterozygosity |

|---|---|---|

| D14S990 | 14q11.2 | 0.85 |

| D14S1048 | 14q13.3 | 0.88 |

| D14S980 | 14q21.2-22.3 | 0.87 |

| D14S1046 | 14q23.3 | 0.89 |

| D14S67 | 14q24.3-q31 | 0.9 |

| D14S995 | 14q31 | 0.8 |

| D14S1142 | 14q32.13 | 0.9 |

| D14S65 | 14q32.1 | 0.8 |

LOH was scored by direct visualization if one of the heterozygous alleles showed at least 50% density reduction of tumor band compared to the corresponding normal DNA band as previously described (Gunduz et al. 2000, 2002). However, for equivocal cases, the bands were quantified with computer-based software (Quantity One, Toyobo, Japan). Total LOH frequency was obtained by dividing the number of LOH cases with the total number of informative cases. A frequency of more than 30% was considered for determining high LOH frequency.

Statistical analysis

Pearson’s Chi-square test and Student’s t tests were used to evaluate the correlation between status of allelic loss and clinicopathological characteristics of the patients. Survival curves were calculated according to Kaplan–Meier. For comparison of survival between LOH (+) and LOH (−) cases for the indicated markers, the log-rank test was used. Overall survival in months was calculated from the day after surgery to the last follow-up examination or death. Survival periods of the patients who were still alive were noted along with the date of the most recent follow-up appointment. The duration of disease-free survival (DFS) was determined from the day after surgery to the initial recurrence of the surgically resected cancer, evaluated by clinical examination. For multivariate analyses, we used the Cox proportional hazards model. All statistical manipulations were done using the SPSS version 10 for the Windows software system (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL) and a significant difference was identified when the probability was less than 0.05.

Results

LOH frequency of chromosome 14

We examined LOH of chromosome 14q11-32 region (spanning about 80 Mbp of genomic region) using eight microsatellite markers in 50 matched normal and HNSCC tissues and identified multiple targeted areas. Overall, LOH was detected at least in one informative location in 44 of 50 (88%) tumor tissues in the long arm of chromosome 14. LOH frequency ranged from 13 to 55% (Fig. 1).

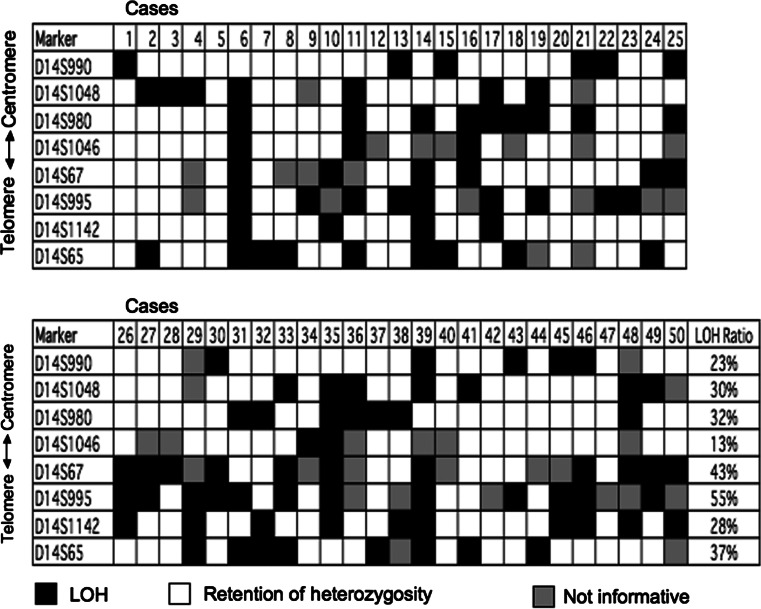

Fig. 1.

A schematic representation of LOH distribution in HNSCC using eight microsatellite markers for chromosome 14q in HNSCC. Case numbers are shown at the top. Microsatellite markers used are shown to the left. Filled box LOH, open box retention of heterozygosity, shaded box not informative (homozygous)

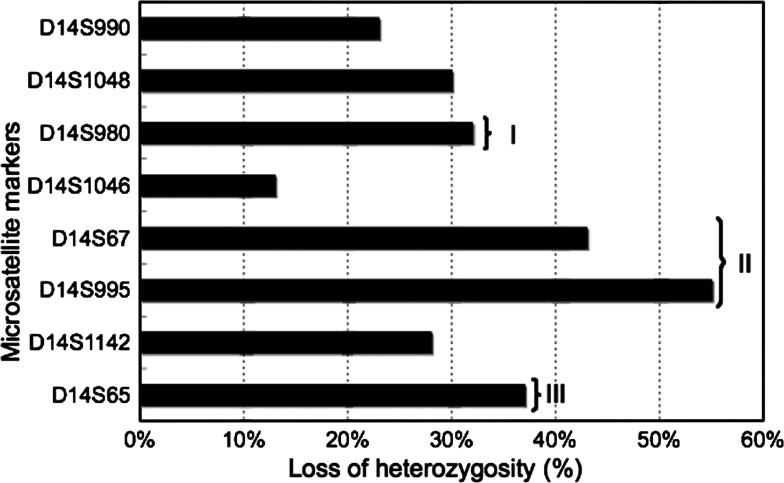

Nine tumor samples (6, 11, 14, 21, 29, 35, 36, 39, and 48) showed large deletion in most of the polymorphic markers tested. In the other 41 samples, partial deletion was detected, providing information about the areas of preferential loss. Considering the physical distances between each marker, three different locations showed high frequency of LOH on chromosome 14q11-32 region. These hotspot regions included the chromosomal areas around the marker D14S65 (14q32.1), D14S995-D14S67 (14q31), and D14S980 (14q21.2-22.3) (Fig. 2). The highest frequency of LOH was observed with D14S995 marker (55%) followed by D14S67 marker (42.5%), which is very close to each other with a distance of 3 Mbp. The markers D14S65 and D14S980 showed 37 and 32% of LOH, respectively.

Fig. 2.

Graphical representation of LOH distribution. I–III shows frequently deleted regions

Interestingly, six cases (13, 19, 22, 23, 31, and 43) revealed LOH only with the marker D14S995 with the retention of flanking markers in both centromere and telomere directions, suggesting distinctive allelic loss of this narrow area and existence of a strong tumor-suppressor candidate. Some other cases (30, 33, and 49) displayed LOH of the markers D14S67 and D14S995 with retention of flanking markers. Considering the close localization of these two markers, the result suggests localization of putative TSG between these microsatellites. Representative samples of informative cases and those with LOH are shown in Fig. 3.

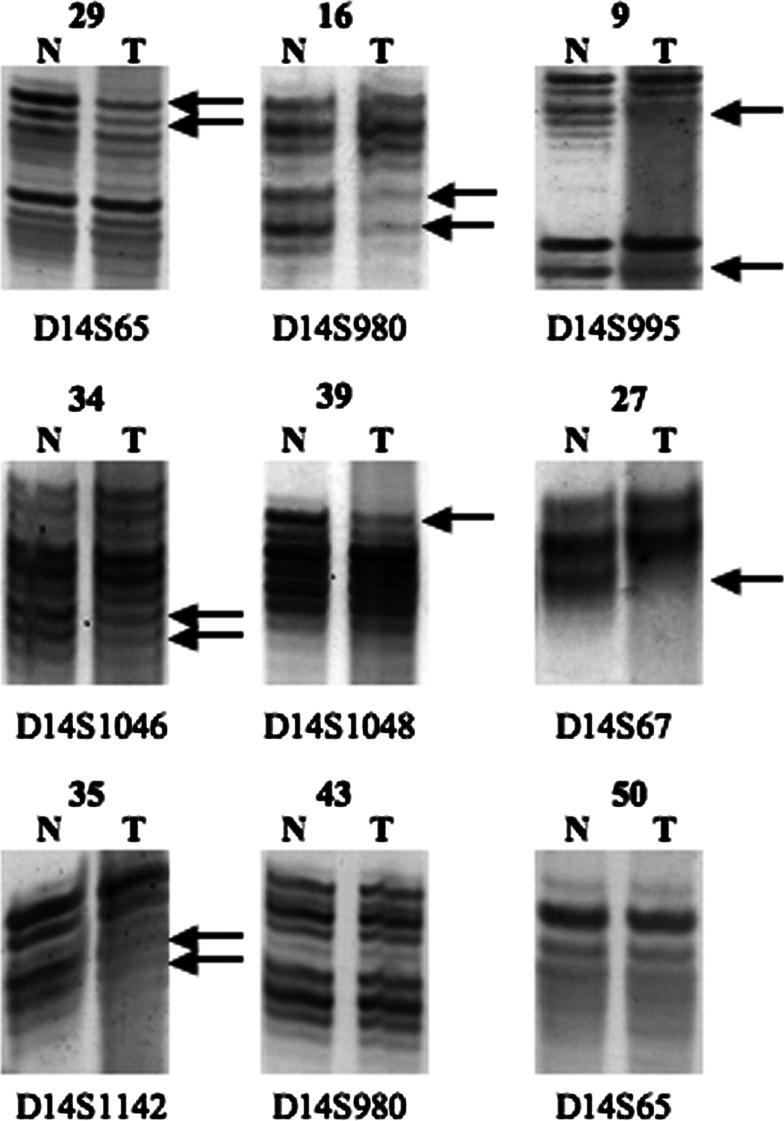

Fig. 3.

Representative results of microsatellite analysis. DNAs of normal (N) and corresponding tumor (T) are shown with microsatellite markers. Deleted alleles in samples with LOH are marked with arrows

The distances between the markers D14S980 and D14S67-D14S995, and D14S67-D14S995 and D14S65 are about 35 Mbp and 7–10 Mbp, respectively [contiguous sequence NT_026437 and Human Genome Resources (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome/guide/human)]. Briefly, high LOH percentage of each hot spot followed by a decreased allelic loss of flanking areas and distinctive deletion of these markers with retention of flanking telomeric and centromeric markers suggested that each of the three frequently deleted areas is a separate hot locus and consists of different candidate TSGs.

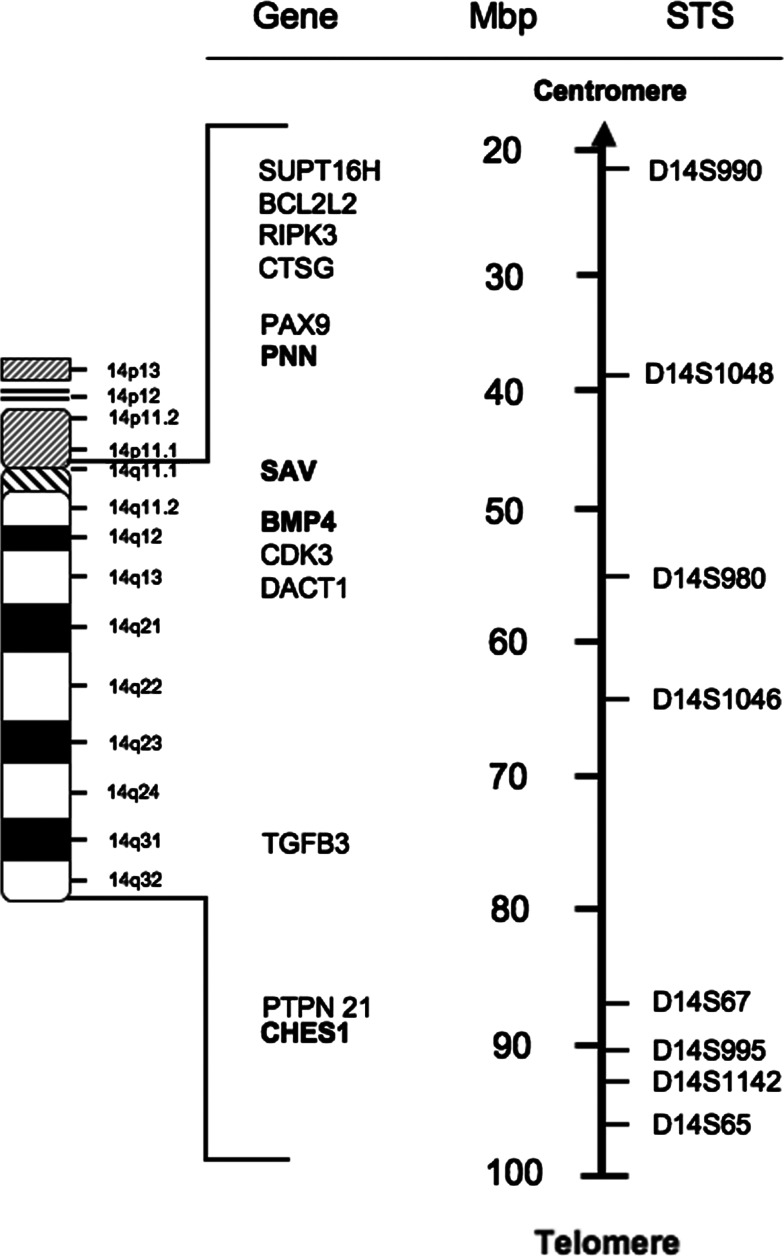

We redefined the map of chromosomal 14q11-32 region according to the recent genome data for location of each marker and gene (http://www.gdb.org, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome/guide/human/) (Fig. 4). The region spanned about 80 Mbp distance between the markers D14S990 and D14S65 and three preferential lost areas were detected.

Fig. 4.

A physical map showing the genomic interval from D14S990 to D14S65 markers based on the latest mapping information from the National Genome Research Institute (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome/guide/human)

Clinicopathological correlation

We examined the relationship between status of allelic loss and clinicopathological characteristics for the markers with highest LOH frequency (Table 2). For statistical evaluation, tumor (T) stages and TNM stages were classified as early (T1 and T2; stage I and II) and late (T3 and T4; stage III and IV), while nodal (N) stages were classified as N0 (without metastasis) and N (+) (with metastasis). A tendency of more regional metastasis was shown in LOH-positive cases of D14S67 and D14S995 as compared to LOH-negative cases for these markers. Half of the cases with LOH demonstrated regional metastasis, while it was about 23% in LOH-negative cases although no statistical significance was obtained. A similar relationship was demonstrated for D14S995 in terms of neck lymph node metastasis. A total of 67% of the cases with deletion at D14S995 showed positive neck lymph node, whereas 36% of the cases without LOH were related with neck lymph node metastasis. The difference was almost significant with a P value of 0.07. On the other hand, a statistically significant difference was obtained between LOH at D14S65 and mean age. No other significant difference was obtained between each variable and each marker.

Table 2.

Relationship between LOH markers and clinicopathological characteristics

| D14S67 | D14S995 | D14S65 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LOH (−) (%) n = 23 (57.5) | LOH (+) (%) n = 17 (42.5) | P | LOH (−) (%) n = 17 (44.7) | LOH (+) (%) n = 21 (55.3) | P | LOH (−) (%) n = 28 (62.2) | LOH (+) (%) n = 15 (37.8) | P | |

| Predictors | |||||||||

| Gender | |||||||||

| Male | 18 (78.3) | 14 (82.4) | 1.00d | 14 (82.4) | 17 (81.0) | 1.00d | 24 (85.7) | 14 (82.4) | 1.00d |

| Female | 5 (21.7) | 3 (17.6) | 3 (17.6) | 4 (19.0) | 4 (14.3) | 3 (17.6) | |||

| Age | |||||||||

| Mean ± SD (years) | 64.6 ± 8.9 | 62.2 ± 10.3 | 0.45c | 63.1 ± 8.5 | 65.6 ± 10.5 | 0.46c | 66.7 ± 9.2 | 60.3 ± 8.8 | 0.03 c |

| Smokinge | |||||||||

| Yes | 5 (25.0) | 3 (17.6) | 0.70d | 2 (14.3) | 4 (19.0) | 1.00d | 4 (16.0) | 2 (11.8) | 1.00d |

| No | 15 (75.0) | 14 (82.4) | 12 (85.7) | 17 881.0) | 16 (84.0) | 15 (88.2) | |||

| Alcohol intakee | |||||||||

| Yes | 8 (42.1) | 5 (33.3) | 0.60b | 4 (28.6) | 8 (40.0) | 0.72d | 7 (31.8) | 6 (35.3) | 0.82b |

| No | 11 (57.9) | 10 (66.7) | 10 (71.4) | 12 (60.0) | 15 (68.2) | 11 (64.7) | |||

| TNM stagea, e | |||||||||

| Early stage (I–II) | 5 (23.8) | 5 (29.4) | 0.73d | 4 (28.6) | 4 (19.0) | 0.68d | 6 (23.1) | 5 (31.3) | 0.72d |

| Late stage (III–IV) | 16 (76.2) | 12 (70.6) | 10 (71.4) | 17 (81.0) | 20 (76.9) | 11 (68.7) | |||

| Tumor stagee | |||||||||

| Early T (T1–T2) | 7 (33.3) | 7 (41.2) | 0.62d | 7 (50.0) | 5 (23.8) | 0.15d | 9 (34.6) | 6 (37.5) | 0.85b |

| Late T (T3–T4) | 14 (66.7) | 10 (58.8) | 7 (50.0) | 16 (76.2) | 17 (65.4) | 10 (62.5) | |||

| Nodal stagee | |||||||||

| N (0) | 11 (52.4) | 9 (52.9) | 0.97b | 9 (64.3) | 7 (33.3) | 0.07b | 11 (42.3) | 10 (62.5) | 0.20b |

| N (+) | 10 (47.6) | 8 (47.1) | 5 (35.7) | 14 (66.7) | 15 (57.7) | 6 (37.5) | |||

| Differentiatione | |||||||||

| Well | 4 (16.0) | 7 (43.8) | 0.16d | 4 (28.6) | 8 (38.1) | 0.72d | 8 (32.0) | 6 (37.5) | 0.72b |

| Moderate–poor | 16 (80.0) | 9 (56.3) | 10 (71.4) | 13 (61.9) | 17 (68.0) | 10 (62.5) | |||

| Previous cancere | |||||||||

| With history | 1 (5.6) | 1 (6.3) | 1.00d | 1 (7.7) | 2 (10.0) | 1.00d | 2 (8.7) | 2 (12.5) | 1.00d |

| No history | 17 (94.4) | 15 (93.8) | 12 (92.3) | 18 (90.0) | 21 (91.3) | 14 (87.5) | |||

| Secondary cancer | |||||||||

| With history | 1 (5.6) | 2 (12.5) | 0.59d | 1 (7.7) | 4 (20.0) | 0.62d | 4 (17.4) | 1 (6.3) | 0.63d |

| No history | 17 (94.4) | 14 (87.5) | 12 (92.3) | 16 (80.0) | 19 (82.6) | 15 (93.7) | |||

| Family cancere | |||||||||

| With history | 6 (33.3) | 8 (50.0) | 0.32b | 6 (46.2) | 8 (40.0) | 0.73b | 12 (52.2) | 5 (31.3) | 0.19b |

| No history | 12 (67.7) | 8 (50.0) | 7 (53.8) | 12 (60.0) | 11 (47.8) | 11 (68.7) | |||

| Local recurrencee | |||||||||

| Positive | 3 (23.1) | 6 (30.0) | 1.00d | 3 (23.1) | 6 (30.0) | 1.00d | 6 (26.1) | 5 (31.3) | 0.73d |

| Negative | 10 (76.9) | 14 (70.0) | 10 (76.9) | 14 (70.0) | 17 (73.9) | 11 (68.8) | |||

| Local metastasise | |||||||||

| Positive | 3 (23.1) | 10 (50.0) | 0.12c | 3 (23.1) | 10 (50.0) | 0.12b | 9 (39.1) | 7 (43.8) | 0.77d |

| Negative | 10 (76.9) | 10 (50.0) | 10 (76.9) | 10 (50.0) | 14 (60.9) | 9 (56.3) | |||

| Distant metastasise | |||||||||

| Positive | 2 (15.4) | 7 (35.0) | 0.26d | 2 (15.4) | 7 (35.0) | 0.26d | 8 (34.8) | 2 (12.5) | 0.15d |

| Negative | 11 (84.6) | 13 (65.0) | 11 (84.6) | 13 (65.0) | 15 (65.2) | 14 (87.5) | |||

Bold indicates statistically significant P values

aAccording to the International Union Against Cancer 1997 TNM classification system

bChi-square test

cStudent’s t test

dFisher exact probability test

eCases with unknown history or record of smoking (three), alcohol consumption (three), TNM stage (three), recurrence (six), differentiation (four), previous cancer history (six), and family cancer history (six) were not included in the evaluation

LOH and survival analysis

Both overall survival (OS) and (DFS) were determined for the frequently deleted markers D14S995 and D14S67. All patients were enrolled in a follow-up program. The follow-up time was between 2 and 129 months. Valid follow-up data was available in 90% of the cases (45/50). Disease relapses (locoregional recurrence and/or distant metastases) occurred in 29 patients (64%) and death was confirmed in 28 patients (62%). The median OS was 30 months (2–129 months), and the median DFS time was 13 months (2–114 months). The mean duration of DFS and OS was 29.8 and 46.9 months, respectively. Five-year DFS and OS were 28.9 and 38.2%, respectively.

The correlation of LOH with each marker (D14S995 and D14S67) and the patients’ overall and disease-free survivals was analyzed using Univariate Kaplan–Meier method. In a 5-year follow-up period, about 70% of the patients without LOH at D14S995 survived, while it was 30% in patients with LOH at the same location (P = 0.04, Fig. 5a). Similarly, about 62% of the patients without LOH at D14S67 survived, whereas it was 35% in the patients with LOH at the same locus (P = 0.05, Fig. 6a). As shown in Fig. 5a, the mean OS in LOH-positive group at D14S995 was 45 ± 9 months (95% CI 27–62 months) and in the LOH-negative group at D14S995 was 95 ± 14 months (95% CI 67–123 months). Log rank test showed that patients with deletion at D14S995 had a significantly shorter OS than those without LOH at D14S995 (P = 0.04, Fig. 5a). As shown in Fig. 5b, the mean DFS in the group with LOH at D14S995 was 26 ± 6 months (95% CI 13–38 months), while that in the group without LOH at D14S995 was 67 ± 14 months (95% CI 40–95 months), with a significant difference between the groups (P = 0.03, log-rank test). Similarly, in Fig. 6a, the mean OS in the group with LOH at D14S67 was 48 ± 11 months (95% CI 27–69 months), and that in the group without LOH at D14S67 was 88 ± 13 months (95% CI 61–114 months). Log-rank test showed that patients with deletion at D14S67 had a borderline significantly shorter OS than those without LOH at D14S67 (P = 0.05, Fig. 6a). On the other hand, in Fig. 6b, the mean DFS in the group with LOH at D14S67 was 25 ± 8 months (95% CI 10–40 months), while that in the group without LOH at D14S67 was 47 ± 11 months (95% CI 26–67 months), with a near significant difference between the groups (P = 0.07, log-rank test). These data suggest that LOH at the markers D14S995 and D14S67 resulted in a shorter overall and disease-free survival in HNSCC patients.

Fig. 5.

Overall (a) and disease-free (b) survivals in the groups of HNSCC patients with LOH and without LOH at location D14S995of the marker

Fig. 6.

Overall (a) and disease-free (b) survivals in the groups of HNSCC patients with LOH and without LOH at location D14S67 of the marker

We also used a multivariate analysis to test the independent value of each parameter predicting OS and DFS. Only LOH status of D14S995 was found to be a prognostic factor related with DFS in multivariate analysis (Table 3). On the other hand, LOH at D14S995 locus, histological differentiation, and radiation therapy (RT) status were independent prognostic factors for poor OS (Table 3).

Table 3.

Cox proportional hazard model for survival analysis

| Variables | Disease-free survival | Overall survival | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P value | 95.0% CI | P value | 95.0% CI | |||||

| RR | Lower | Upper | RR | Lower | Upper | |||

| Age | 0.18 | 25.40 | 0.23 | 2,795.04 | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 1.48 |

| Gender | 0.20 | 92.77 | 0.09 | 980.04 | 0.94 | 0.79 | 0.00 | 335.79 |

| Smoking | 0.15 | 176.14 | 0.15 | 2,029.48 | 0.23 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 6.05 |

| Alcohol | 0.71 | 0.35 | 0.00 | 94.95 | 0.06 | 88.01 | 0.80 | 9,720.55 |

| T stage | 0.17 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 31.01 | 0.29 | 19.71 | 0.08 | 4,829.85 |

| N stage | 0.15 | 2,148.01 | 0.06 | 7,502.41 | 0.41 | 3.31 | 0.20 | 55.38 |

| TNM stage | 0.26 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 11.60 | 0.66 | 6.42 | 0.00 | 23,596.23 |

| Cancer history | 0.12 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 4.26 | 0.28 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 15.88 |

| Family cancer history | 0.16 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 23.41 | 0.29 | 4.77 | 0.26 | 87.55 |

| Differentiation | 0.98 | 1.04 | 0.04 | 27.08 | 0.01 | 3,200.11 | 11.35 | 9,147.52 |

| RT | 0.98 | 0.95 | 0.05 | 19.86 | 0.01 | 281.90 | 4.55 | 17,458.53 |

| CT | 0.15 | 357.78 | 0.12 | 1,051.25 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 1.33 |

| D14S67 | 0.13 | 174.08 | 0.20 | 1,482.85 | 0.24 | 0.09 | 0.00 | 4.95 |

| D14S995 | 0.01 | 117.71 | 3.20 | 4,336.75 | 0.03 | 695.43 | 1.87 | 2,216.98 |

P value with bold indicators shows statistically significant value

95.0% CI confidence interval, RR risk ratio

Discussion

The functional loss of tumor suppressor genes is closely related to the initiation and/or progression of human cancer. Our previous genome-wide LOH analysis using few widely located microsatellite markers in a limited number of HNSCC cases revealed frequently deleted hot spots on the long arm of chromosome 14. Moreover, a high frequency of LOH in this chromosome has been reported in various cancers (Bando et al. 1999; De Rienzo et al. 2000; El-Rifai et al. 2000; Hoshi et al. 2000; Mitsumori et al. 2002). However, it has not been examined in detail in HNSCC. Thus, in the current study, we examined in detail these hot spot regions of allelic loss in a large number of samples by using eight microsatellite markers. Furthermore, we evaluated the correlation between LOH frequency and clinicopathological characteristics.

Our data demonstrated a very high overall allelic loss on chromosome 14q and revealed three different regions, where a possible TSG can reside. Only few papers examined the status of allelic deletion of chromosome 14q in HNSCC. To the best of our knowledge, only three articles (two of them in nasopharynx cancers) reported allelic loss in cancer of the head and neck area (Lee et al. 1997; Lung et al. 2001; Yan et al. 2005). In one of these articles, regions of 14q13-21 and 14q31-32.1 were indicated to be possibly harboring TSG (Lee et al. 1997). The other two reports related with nasopharyngeal cancer from China included only a few markers for analysis (Lung et al. 2001; Yan et al. 2005). Now we have a more precise mapping of each marker and gene and more accurate results for allelic deletion analysis. Thus, our study is likely to contribute to the identification of TSG from this region in HNSCC.

Although there are many genes located on 14q, in search for candidate TSG between D14S67 and D14S995, two possible candidate TSGs including protein tyrosine phosphatase gene (PTPN21 gene, non-receptor 21) and Check point suppressor 1 (CHES1), localized in this frequently deleted area. Protein-tyrosine phosphatases (PTPs) are known to be signaling molecules that regulate a variety of cellular processes including cell growth, differentiation, mitotic cycle, and oncogenic transformation. PTPs, considered as negative regulators of proliferative cellular processes, reverse the action of protein-tyrosine kinases (PTKs). Abnormalities in tyrosyl phosphorylation can result in various human diseases, including cancer. In fact, PTEN, one of the PTPs, was known as a well-known TSG in various cancers including HNSCC. However, most others are also known as oncogenic properties (Tiganis and Bennett 2007). PTPN21 contains an N-terminal domain, similar to cytoskeletal-associated proteins including band 4.1, ezrin, merlin, and radixin. This PTP was shown to specially interact with BMX/ETK, a member of Tec tyrosine kinase family characterized by multimodular structures including PH, SH3, and SH2 domains. The interaction of this PTP with BMX kinase was found to increase the activation of STAT3, but not STAT2 kinase. Studies of a similar gene in mice suggested the possible roles of this PTP in liver regeneration and spermatogenesis (Jui et al. 2000). Regarding PTPN21, no article has yet been published supporting PTPN21’s function as a TSG. Rather, it has recently been demonstrated that PTPN21 (also called PTPD1) plays as an oncogene by activating src tyrosine kinase and increasing EGFR signaling (Cardone et al. 2004). On the other hand, CHES1 (checkpoint suppressor 1; FOXN3) was identified as a human cDNA encoding a member of the forkhead/winged helix family of transcription factors, which can function as a high-copy suppressor of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae G2/M checkpoint mutants rad9, mec1, rad24, rad53, and dun1. Specifically, Ches1 was reported to confer increased survival after exposure to UV irradiation, ionizing irradiation, and methylmethane sulfonate (MMS). Moreover, Ches1 was also reported to be able to reconstitute a DNA damage-induced G2/M arrest absent in checkpoint-deficient strains, even in a mec1 mutant strain, which is normally nonviable (Scott and Plon 2003). Furthermore, CHES1 has been recently reported to upregulate in parallel to overexpression of a putative tumor suppressor, KLF4, in colon cancer (Whitney et al. 2006). CHES1 was shown to be downregulated in oral cancer (Chang et al. 2005). CHES1 was also recently demonstrated to repress genes important for tumorigenesis (Scott and Plon 2005). Considering these reports, CHES1 is the possible TSG for HNSCC in our study.

Although only 30% LOH frequency was obtained at the marker D14S1048, a candidate gene, PNN (also called PININ, DRS) is located very close to this marker. PNN was shown to be a cell adhesion-related molecule and might act as a TSG in certain types of cancer (Shi et al. 2000). SAV and BMP4 located around the frequently deleted marker D14S980 were reported to function as a TSG and to promote apoptosis, respectively (Harvey and Tapon 2007; Nishanian et al. 2004).

The association between LOH and poor prognosis in HNSCC has been reported in various studies (Lydiatt et al. 1998; Ransom et al. 1998). Ransom et al. (1998) showed the association between LOH on the distal portion of chromosome 2 and poor prognosis in HNSCC, and that LOH on chromosome 2q was possibly a predictor of local recurrence and death (Ransom et al. 1998). Lydiatt et al. (1998) found another locus on 9p and showed the association between aggressive behavior of HNSCC and LOH. Regarding the relationship of LOH at 14q and clinicopathological variables in HNSCC, Lee et al. (1997) performed correlation of overall LOH at 14q and poor survival. In that study, although high LOH frequency barely correlated with clinicopathological features, a strong correlation was observed between LOH and OS.

In the current study, we examined the relationship between LOH at the frequently deleted markers of D14S67, D14S995 and D14S65 and clinicopathological variables, and no significant difference was detected. However, survival analysis showed significantly poor prognosis in the cases with LOH of the markers D14S995 and D14S67 as compared to the cases without LOH. Thus, our results suggest that each of these microsatellites can be used as an independent prognostic marker in HNSCCs. The regions in which we detected high LOH is consistent with our previous study except the 14q11-12 region due to usage of only one marker at this area. Thus, we focused on the telomere side of chromosome 14 and used just one marker (D14S990) to analyze the centromere region due to lack of highly polymorphic markers in the proximal region.

In conclusion, the current research revealed three preferentially deleted regions on chromosome 14, which may host TSGs that have a role in development and/or progression of HNSCC. We also showed the prognostic usage of several markers in 14q for HNSCCs. Various candidate TSGs including CHES1, BMP4, SAV, and PNN have arisen as candidate TSG in HNSCC. Future functional studies should be carried out to clarify the role of these genes in HNSCC tumorigenesis.

Acknowledgments

This work was partially supported by grants-in-aid for scientific research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology [19592109 (to HN), 18-06262 (to EG), 17406027 (to NN)], Seed Innovation Research from Japan Science and Technology Agency (to MG), from Sumitomo Trust Haraguchi Memorial Cancer Research Promotion (to MG) and Astrazeneca Research Grant (to MG).

Conflict of interest statement

None of the authors has any potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Davut Pehlivan and Esra Gunduz contributed equally to this work.

References

- Bando T, Kato Y, Ihara Y, Yamagishi F, Tsukada K, Isobe M (1999) Loss of heterozygosity of 14q32 in colorectal carcinoma. Cancer Genet Cytogenet 111:161–165. doi:10.1016/S0165-4608(98)00242-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beder LB, Gunduz M, Ouchida M, Fukushima K, Gunduz E, Ito S et al (2003) Genome-wide analyses on loss of heterozygosity in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. Lab Invest 83:99–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardone L, Carlucci A, Affaitati A, Livigni A, DeCristofaro T, Garbi C et al (2004) Mitochondrial AKAP121 binds and targets protein tyrosine phosphatase D1, a novel positive regulator of src signaling. Mol Cell Biol 24:4613–4626. doi:10.1128/MCB.24.11.4613-4626.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cengiz B, Gunduz M, Nagatsuka H, Beder L, Gunduz E, Tamamura R et al (2007) Fine deletion mapping of chromosome 2q21-37 shows three preferentially deleted regions in oral cancer. Oral Oncol 43:241–247. doi:10.1016/j.oraloncology.2006.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang JT, Wang HM, Chang KW, Chen WH, Wen MC, Hsu YM et al (2005) Identification of differentially expressed genes in oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC): overexpression of NPM, CDK1 and NDRG1 and underexpression of CHES1. Int J Cancer 114:942–949. doi:10.1002/ijc.20663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croce CM (1991) Genetic approaches to the study of the molecular basis of human cancer. Cancer Res 51:5015s–5018s [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Rienzo A, Jhanwar SC, Testa JR (2000) Loss of heterozygosity analysis of 13q and 14q in human malignant mesothelioma. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 28:337–341. doi:10.1002/1098-2264(200007)28:3<337::AID-GCC12>3.0.CO;2-B [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Rifai W, Sarlomo-Rikala M, Andersson LC, Miettinen M, Knuutila S (2000) High-resolution deletion mapping of chromosome 14 in stromal tumors of the gastrointestinal tract suggests two distinct tumor suppressor loci. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 27:387–391. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-2264(200004)27:4<387::AID-GCC8>3.0.CO;2-C [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunduz M, Ouchida M, Fukushima K, Hanafusa H, Etani T, Nishioka S et al (2000) Genomic structure of the human ING1 gene and tumor-specific mutations detected in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. Cancer Res 60:3143–3146 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunduz M, Ouchida M, Fukushima K, Ito S, Jitsumori Y, Nakashima T et al (2002) Allelic loss and reduced expression of the ING3, a candidate tumor suppressor gene at 7q31, in human head and neck cancers. Oncogene 21:4462–4470. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1205540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunduz M, Nagatsuka H, Demircan K, Gunduz E, Cengiz B, Ouchida M et al (2005) Frequent deletion and down-regulation of ING4, a candidate tumor suppressor gene at 12p13, in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. Gene 356:109–117. doi:10.1016/j.gene.2005.02.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey K, Tapon N (2007) The Salvador–Warts–Hippo pathway––an emerging tumour-suppressor network. Nat Rev Cancer 7:182–191. doi:10.1038/nrc2070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbers J, Schullerus D, Muller H, Kenck C, Chudek J, Weimer J et al (1997) Significance of chromosome arm 14q loss in nonpapillary renal cell carcinomas. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 19:29–35. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-2264(199705)19:1<29::AID-GCC5>3.0.CO;2-2 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoshi M, Otagiri N, Shiwaku HO, Asakawa S, Shimizu N, Kaneko Y et al (2000) Detailed deletion mapping of chromosome band 14q32 in human neuroblastoma defines a 1.1-Mb region of common allelic loss. Br J Cancer 82:1801–1807. doi:10.1054/bjoc.2000.1108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Murray T, Xu J, Smigal C et al (2006) Cancer statistics, 2006. CA Cancer J Clin 56:106–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jui HY, Tseng RJ, Wen X, Fang HI, Huang LM, Chen KY et al (2000) Protein-tyrosine phosphatase D1, a potential regulator and effector for Tec family kinases. J Biol Chem 275:41124–41132. doi:10.1074/jbc.M007772200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee DJ, Koch WM, Yoo G, Lango M, Reed A, Califano J et al (1997) Impact of chromosome 14q loss on survival in primary head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 3:501–505 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Lee NK, Ye YW, Waber PG, Schweitzer C, Cheng QC et al (1994) Allelic loss at chromosomes 3p, 8p, 13q, and 17p associated with poor prognosis in head and neck cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 86:1524–1529. doi:10.1093/jnci/86.20.1524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lung ML, Choi CV, Kong H, Yuen PW, Kwong D, Sham J et al (2001) Microsatellite allelotyping of chinese nasopharyngeal carcinomas. Anticancer Res 21:3081–3084 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lydiatt WM, Davidson BJ, Schantz SP, Caruana S, Chaganti RS (1998) 9p21 deletion correlates with recurrence in head and neck cancer. Head Neck 20:113–118. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0347(199803)20:2<113::AID-HED3>3.0.CO;2-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitsumori K, Kittleson JM, Itoh N, Delahunt B, Heathcott RW, Stewart JH et al (2002) Chromosome 14q LOH in localized clear cell renal cell carcinoma. J Pathol 198:110–114. doi:10.1002/path.1165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishanian TG, Kim JS, Foxworth A, Waldman T (2004) Suppression of tumorigenesis and activation of Wnt signaling by bone morphogenetic protein 4 in human cancer cells. Cancer Biol Ther 3:667–675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P (2005) Global cancer statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J Clin 55:74–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piao Z, Park C, Park JH, Kim H (1998) Allelotype analysis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Cancer 75:29–33. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19980105)75:1<29::AID-IJC5>3.0.CO;2-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ransom DT, Barnett TC, Bot J, de Boer B, Metcalf C, Davidson JA et al (1998) Loss of heterozygosity on chromosome 2q: possibly a poor prognostic factor in head and neck cancer. Head Neck 20:404–410. doi:10.1002/(SICI) 1097-0347(199808) 20:5<404::AID-HED8>3.0.CO;2-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott KL, Plon SE (2003) Loss of Sin3/Rpd3 histone deacetylase restores the DNA damage response in checkpoint-deficient strains of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol 23:4522–4531. doi:10.1128/MCB.23.13.4522-4531.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott KL, Plon SE (2005) CHES1/FOXN3 interacts with Ski-interacting protein and acts as a transcriptional repressor. Gene 359:119–126. doi:10.1016/j.gene.2005.06.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y, Ouyang P, Sugrue SP (2000) Characterization of the gene encoding pinin/DRS/memA and evidence for its potential tumor suppressor function. Oncogene 19:289–297. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1203328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon M, von Deimling A, Larson JJ, Wellenreuther R, Kaskel P, Waha A et al (1995) Allelic losses on chromosomes 14, 10 and 1 in atypical and malignant meningiomas: a genetic model of meningioma progression. Cancer Res 55:4696–4701 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiganis T, Bennett AM (2007) Protein tyrosine phosphatase function: the substrate perspective. Biochem J 402:1–15. doi:10.1042/BJ20061548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitney EM, Ghaleb AM, Chen X, Yang VW (2006) Transcriptional profiling of the cell cycle checkpoint gene krüppel-like factor 4 reveals a global inhibitory function in macromolecular biosynthesis. Gene Expr 13:85–96. doi:10.3727/000000006783991908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan W, Song L, Wei W, Li A, Liu J, Fang Y (2005) Chromosomal abnormalities associated with neck nodal metastasis in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Tumour Biol 26:306–312. doi:10.1159/000089289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]