Abstract

Purpose

To explore the appropriate method of mediastinal lymph node dissection for selected clinical stage IA (cIA) non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC).

Methods

From 1998 through 2002, the curative-intent surgery was performed to 105 patients with cIA NSCLC who had been postoperatively identified as pathologic-stage T1. According to the method of intraoperative medistinal lymph node dissection, they were divided into radical systematic mediastinal lymphadenectomy (LA) group (n = 42) and mediastinal lymph-node sampling (LS) group (n = 63). The effects of LS and LA on morbidity, N staging, overall survival (OS) and disease-free survival (DFS) were investigated. Also, associations between clinicopathological parameters and survival were analyzed.

Results

The mean numbers of dissected lymph nodes per patient in the LA group was significantly greater than that in the LS group (15.59 ± 3.08 vs. 6.46 ± 2.21, P < 0.001), and the postoperative overall morbidity rate was higher in the LA group than that in the LS group (26.2 vs. 11.1%, P = 0.045). There were no significant difference in migration of N staging, OS and DFS between two groups. However, for patients with lesions between 2 and 3 cm, the 5-year OS in LA group was significantly higher than that in LS group (81.6 vs. 55.8%, P = 0.041), and the 5-year DFS was also higher (77.9 vs. 52.5%, P = 0.038). For patients with lesions of 2 cm or less, 5-year OS and DFS were similar in both groups. Multivariate analysis showed that lymph node metastasis was the unique unfavorable prognostic factor (P < 0.001).

Conclusions

After being intraoperatively identified as stage T1, patients with lesions between 2 and 3 cm in cIA NSCLC should be performed with LA to get a potentially better survival, and patients with lesions of 2 cm or less should be performed with LS to decrease invasion.

Keywords: Non-small cell lung cancer, Clinical stage IA, Mediastinal lymph node dissection, Prognosis

Introduction

The preferred treatment with a chance of cure of patients with localized non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is lobectomy with mediastinal lymph node dissection. There has been broad consensus on lobectomy, whereas the method of radical systematic mediastinal lymphadenectomy or lymph node sampling is still controversial on such issues as a better survival or a more accurate staging for LA in comparison with LS. Up to now, although there have been several prospective controlled studies published (Keller et al. 2000; Izbicki et al. 1998; Sugi et al. 1998; Wu et al. 2002), they had never reached a consensus.

Lung cancer remains a major health problem in the world, with an estimated overall 5-year survival of 16% (Jemal et al. 2007). Although patients with clinical stage IA (cIA) non-small cell lung cancer fare significantly better than those with more advanced disease, the overall 5-year survival is just 61 or 70% (Moutain 1997; Naruke et al. 2001), and a significant fraction of the patients with cIA NSCLC have disease recurrence and die after a curative resection. Could LA or LS lead to a different result on patients with cIA NSCLC? Very few data on this issue are available except for Sugi and his colleagues’ study (Sugi et al. 1998) with respect to clinically diagnosed peripheral NSCLC less than 2 cm in diameter, which shows a similar 5-year survival in the LA group and the LS group. To investigate more thoroughly the issue of potentially rational method of lymph node dissection in patients with cIA NSCLC, we undertook a retrospective two-institute review.

Patients and methods

Patients

Informed consent was obtained from the patients or surrogates. One hundred and twenty-four patients with potential clinical stage IA NSCLC (36 of them had not achieved histological diagnosis until fast pathological technique was performed intraoperatively), who underwent curative-intent surgery from January 1998 to January 2002, were identified from Beijing Friendship Hospital (89 patients) and Qingdao Municipal Hospital (35 patients). Tumors were classified according to the staging classification suggested by the International Union for the Control of Cancer in 1997 (Moutain 1997).

Preoperative evaluation included a history, physical examination, chemical profile, plain chest radiography, sputum examination, bronchoscopy, CT of the chest, head and upper abdomen, bone scan and cardiopulmonary function. Some patients were performed percutaneous biospy under CT guidance (71 patients). Patients with intrathoracic lymph node >1 cm according to CT were excluded from this study for the possibility of metastasis.

Among them, 19 patients were excluded postoperatively from this study because of being negative for evidence of malignancy (6 patients), not meeting the pathologic stage T1 (7 patients), or being not sampled at surgery (4 patients) and having two primary tumors (2 patients). The remaining 105 patients with pathologic stage T1N0–2M0 were enrolled into this study, and none of them underwent preoperative chemoradiotherapy. All patients with involvement of any lymph node received chemotherapy including cisplantin postoperatively. The characteristics of 105 patients listed in Table 1, which showed that the baseline features in both groups were balanced.

Table 1.

The characteristics of 105 patients with clinical-stage IA NSCLC

| Variables | LA (n = 42) (%) | LS (n = 63) (%) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.746 | ||

| <60 years | 24 (57.1) | 38 (60.3) | |

| ≥60 years | 18 (42.9) | 25 (39.7) | |

| Sex | 0.745 | ||

| Male | 26 (61.9) | 37 (58.7) | |

| Female | 16 (38.1) | 26 (41.3) | |

| Histology | 0.987 | ||

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 12 (28.6) | 18 (28.6) | |

| Adenocarcinoma | 27 (64.3) | 41 (65.1) | |

| Other types | 3 (7.1) | 4 (6.3) | |

| Tumor size | 0.865 | ||

| ≤2 cm | 14 (33.3) | 20 (31.7) | |

| >2 cm | 28 (66.7) | 43 (68.3) | |

| Tumor location | 0.612 | ||

| Peripheral | 33 (78.6) | 52 (82.5) | |

| Central | 9 (21.4) | 11 (17.5) | |

LA radical systematic mediastinal lymphadenectomy, LS mediastinal lymph node sampling

Surgical methods

One hundred and five patients with cIA NSCLC underwent lobectomy including primary lung tumor together with hilar and mediastinal lymph node dissection. The mediastinal stations were defined as described in the AJCC cancer staging manual (Greene et al. 2002). All 105 patients were divided into a radical systematic mediastinal lymphadenectomy (LA) group and a mediastinal lymph node sampling (LS) group. According to descriptions of Naruke, Martini, Izbicki and their colleagues (Naruke et al. 1976; Martini and Flehinger 1987; Izbicki et al. 1994), the methods of LA were modified slightly (in left-side cancers, lymph nodes of level 2 and 3 are not resected). LA was defined as removal of levels 2–4, 7–9 and 10–12 during a right thoracotomy and levels 4–9 and 10–12 during a left thoracotomy. In the LS group, the methods of mediastinal sampling were similar to the definitions used by the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group in the ECOG 3590 trial (Keller et al. 2000). Thus, at least one lymph node at levels 4 and 7 for right-side tumors and at levels 5 or 6 and 7 for left-side tumors were removed. In addition, palpable or visual lymph node suspected of being malignant and levels 10–12 were required.

Follow-up

The expiration of follow-up was in March 2007. The median follow-up time was 70 months, and 91.3% of the patients had been followed. Patients were followed up at 3- or 6-month intervals. The routine examinations included physical examination, plain chest X-ray or CT, abdominal ultrasound and yearly brain CT or MRI, bone scan, and bronchoscopy with biopsy if warranted.

Recurrence was evaluated on the basis of clinical findings and images at the follow-up visit. Local recurrence was defined as any recurrence within the ipsilateral chest cavity, and all other recurrences were classified as distant metastases.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 13.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The data was expressed as the mean ± SD. Differences between means were evaluated with Student’s t test. Comparisons between proportions were made by Pearson’s χ2 test or Continuity Correction χ2 test or Fisher exact probability test. Distribution of overall survival and disease-free survival was estimated with the Kaplan-Meier method and compared with the log-rank test. Forward stepwise Cox regression was used to evaluate the prognostic factor. P values < 0.05 were regarded as statistically significant.

Disease-free survival was defined as the time from surgery to first locoregional or distant recurrence. The overall survival was calculated from the date of surgery. An observation was censored at the last follow-up if the patient was alive or if the patient had died from a cause other than the original NSCLC or if the patient was lost.

Results

Early surgery-related parameters and morbidity

There was a significantly longer mean duration of surgery and a higher drain secretion in the LA group compared with that in the LS group, whereas blood loss, blood transfusions and duration of drainage were similar in both groups (Table 2). No surgery-related death occurred and the majority of early complications were arrhythmia, pneumonia or atelectasis in both groups. In contrast with the LS group, the overall morbidity rate was significantly higher in the LA group (LA vs. LS = 26.2 vs. 11.1%, P = 0.045). Also, stratification was performed according tumour size, and Table 3 shows the morbidity of postoperative complication, respectively. There was a trend, although not statistically significant, for the LA group to obtain a higher morbidity than that in the LS group.

Table 2.

Surgery-related parameters in LA and LS groups of 105 cIA NSCLCs

| Parameters | LA | LS | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Duration of surgery (min) | 217.85 ± 39.36 | 180.48 ± 25.44 | <0.001** |

| Blood bloss (ml) | 565.48 ± 263.30 | 487.30 ± 260.42 | 0.137 |

| Blood transfusion (units) | 0.88 ± 1.68 | 0.62 ± 1.46 | 0.400 |

| Drain secretion (ml) | 1280.95 ± 467.60 | 1120.63 ± 200.93 | 0.018* |

| Duration of drainage (days) | 5.05 ± 1.43 | 4.73 ± 1.02 | 0.187 |

LA radical systematic mediastinal lymphadenectomy, LS lymph node sampling

* P < 0.05, ** P < 0.001

Table 3.

Complications in patients with different tumor size and method of lymphadenectomy

| Variables | ≤2 cm | P value | >2 cm | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LA (n = 14) | LS (n = 20) | LA (n = 28) | LS (n = 43) | |||

| Arrhythmia | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | ||

| Pneumonia or atelectasis | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | ||

| Prolonged air leak (>7 days) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | ||

| Recurrent laryngeal nerve leision | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Chylothorax | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | ||

| Myocardial infarction | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | ||

| Total | 4 (28.6%) | 2 (10.0%) | 0.202 | 7 (25.0%) | 5 (11.6%) | 0.252 |

LA radical systematic mediastinal lymphadenectomy, LS lymph node sampling

Staging

The mean numbers of dissected lymph nodes was 15.59 ± 3.08 per patient in the LA group and 6.46 ± 2.21 in the LS group, and difference was significant (P < 0.001). Postoperatively pathologic stage showed, among 105 patients, 82 patients had T1N0M0 disease, 7 patients had T1N1M0 disease and 16 patients had T1N2M0 disease. In another word, 23 patients (21.9%) were identified as upstaging of N stage. There were nine patients with lymph node metastases in the LA group (9/42, 21.4%): two patients had N1 disease (4.8%), and seven patients had N2 disease (16.7%) including two patients with multiple levels N2 disease (4.8%). There were 14 patients with lymph node metastases in the LS group (14/63, 22.2%): 5 patients had N1 disease (7.9%), and 9 patients had N2 disease (14.3%) including 2 patients with multiple levels N2 disease (3.2%). The percentage of patients with N1 or N2 or multiple levels N2 disease was similar in both groups. Also, no different percentage of patients with N1 or N2 disease was found in either method of lymph node dissection in stratification according to tumor size (>2 cm and ≤2 cm in diameter, data not shown).

Survival

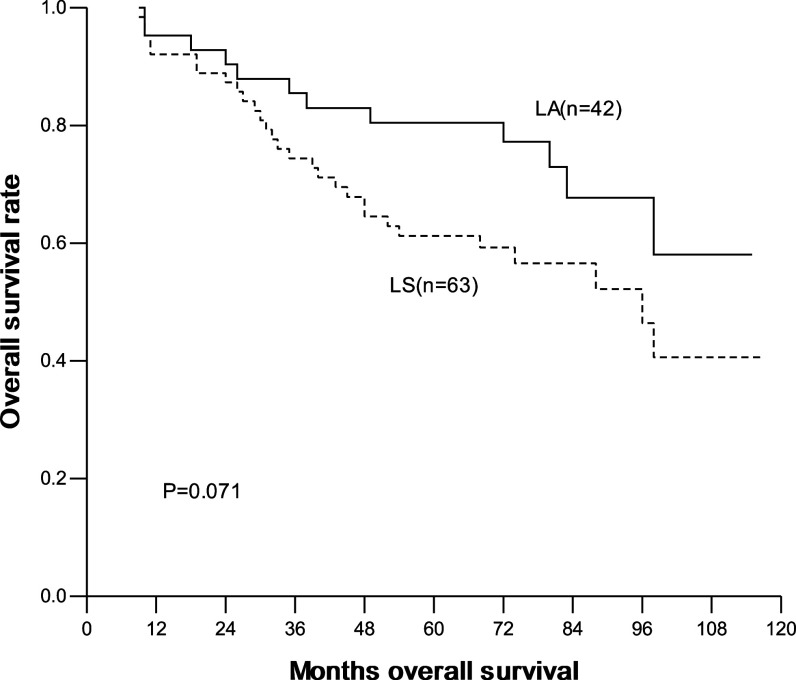

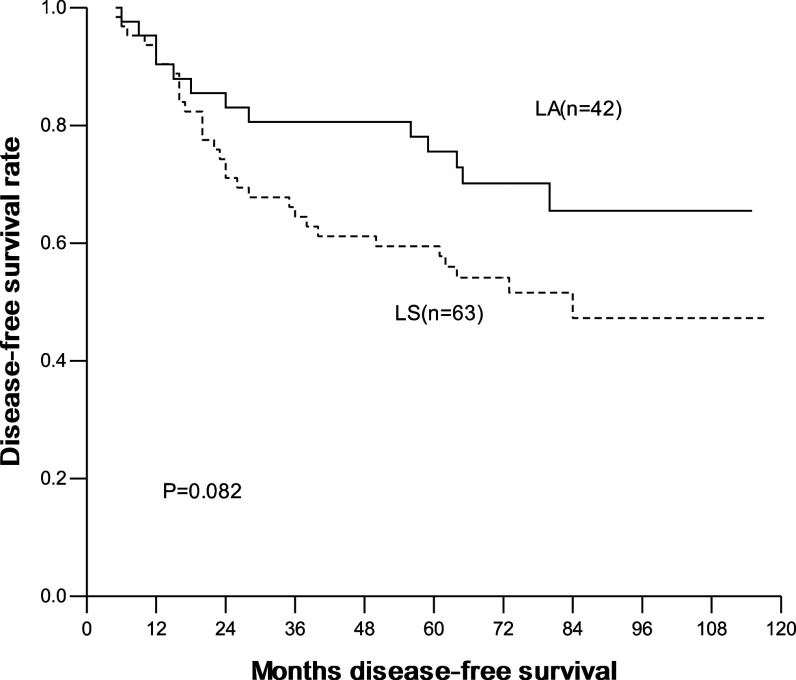

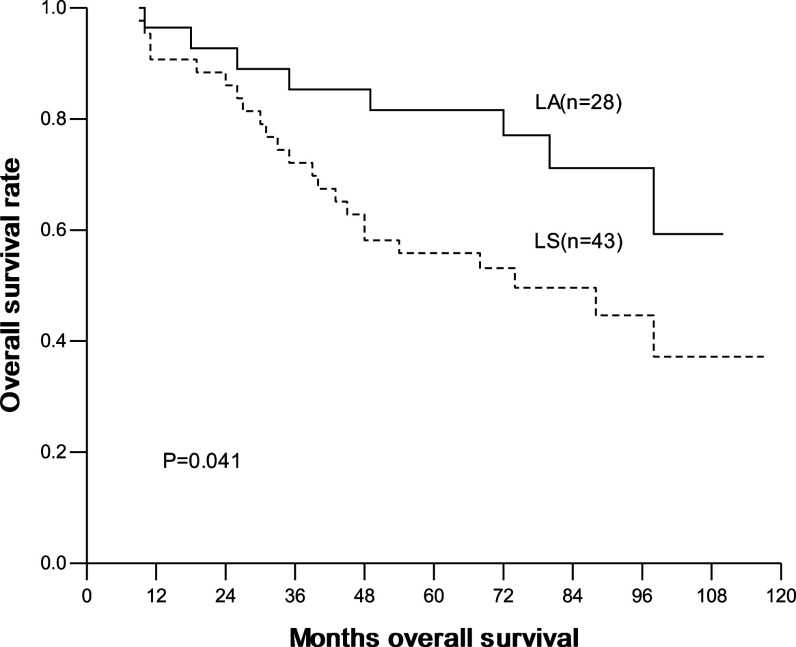

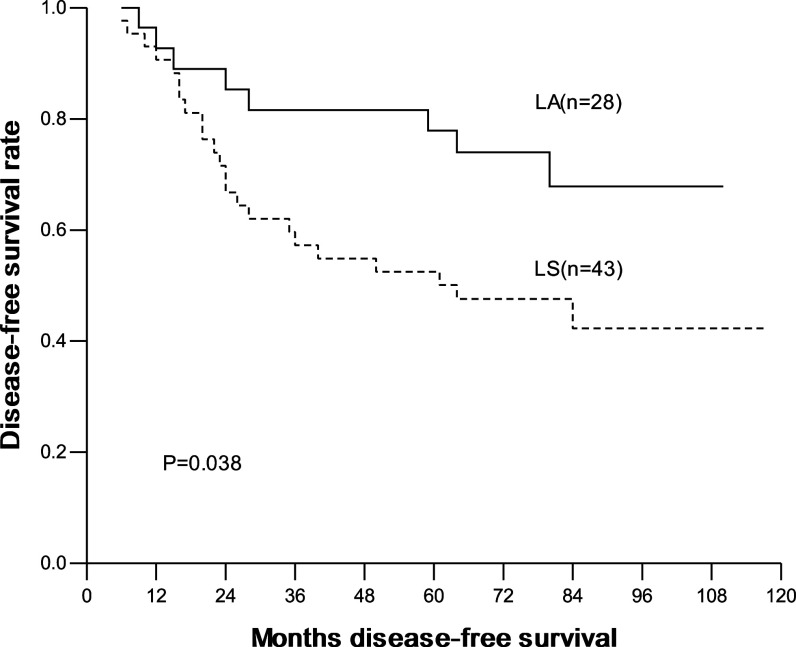

The overall and disease-free 1-, 3-, 5-year survival were 93.3, 78.8, 68.9% and 90.4, 70.9, 65.9%, respectively. In the LA group, they were 95.2, 85.5, 80.4% and 90.4, 80.6, 75.5%, respectively; and in the LS group, they were 92.1, 74.4, 61.2% and 90.4, 64.5, 59.5%, respectively. No significant difference in overall and disease-free survival was seen between two groups (Figs. 1, 2). Interestingly, for patients with ≤2 cm lesions, the overall and disease-free survival was similar between patients with LA and with LS. In contrast, for patients with 2–3 cm lesions, the overall and disease-free survival was significantly higher in patients with LA than with LS (Table 4; Figs. 3, 4).

Fig. 1.

Overall survival curves with method of mediastinal lympadenectomy, LA versus LS (LA radical systematic mediastinal lymphadenectomy, LS lymph node sampling)

Fig. 2.

Disease-free survival curves with method of mediastinal lympadenectomy, LA versus LS (LA radical systematic mediastinal lymphadenectomy, LS lymph node sampling)

Table 4.

OS and DFS in patients with different tumor size and method of lymphadenectomy

| Tumor size | Methods of lymphadenectomy | Cases (n) | OS (%) | P value | DFS (%) | P value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 year | 3 year | 5 year | 1 year | 3 year | 5 year | |||||

| >2 cm | LA | 28 | 96.4 | 85.3 | 81.6 | 0.041 | 92.7 | 81.6 | 77.9 | 0.038 |

| LS | 43 | 90.7 | 72.1 | 55.8 | 90.6 | 57.2 | 52.5 | |||

| ≤2 cm | LA | 14 | 92.9 | 85.7 | 77.9 | 0.977 | 85.7 | 78.6 | 70.7 | 0.992 |

| LS | 20 | 95.0 | 79.4 | 73.7 | 90.0 | 80.0 | 74.7 | |||

OS overall survival, DFS disease-free survival, LA radical systematic mediastinal lymphadenectomy, LS lymph node sampling

Fig. 3.

Overall survival curves according to LA and LS in patients with lesions between 2 and 3 cm (LA radical systematic mediastinal lymphadenectomy, LS lymph node sampling)

Fig. 4.

Disease-free survival curves according to LA and LS in patients with lesions between 2 and 3 cm (LA radical systematic mediastinal lymphadenectomy, LS lymph node sampling)

Associations between clinical-pathological parameters and survival

Associations between clinical–pathological parameters and survival were analyzed in this study. Patients with large cell carcinoma and adenosquamous carcinoma were associated with significantly poorer 5-year OS, and patients with lymph node metastases were associated with poorer 5-year OS as well as 5-year DFS (Table 5).

Table 5.

Associations between clinical-pathological parameters and 5-year OS and DFS

| Clinical–pathological parameters | 5-year OS (%) | P value | 5-year DFS (%) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year) | 0.581 | 0.752 | ||

| ≥60 | 64.3 | 61.6 | ||

| <60 | 71.9 | 68.8 | ||

| Sex | 0.984 | 0.287 | ||

| Male | 69.1 | 70.3 | ||

| Female | 68.5 | 59.5 | ||

| Histology | 0.024* | 0.254 | ||

| AD | 72.9 | 68.6 | ||

| SQ | 69.3 | 66.3 | ||

| Other | 28.6 | 33.3 | ||

| Tumor location | 0.450 | 0.310 | ||

| Central | 70.0 | 70.0 | ||

| Peripheral | 68.6 | 64.8 | ||

| Tumor size | 0.357 | 0.527 | ||

| >2 cm | 65.8 | 62.4 | ||

| ≤2 cm | 75.7 | 72.9 | ||

| Lymphadenectomy | 0.071 | 0.082 | ||

| LA | 80.4 | 75.5 | ||

| LS | 61.2 | 59.5 | ||

| Node metastases | <0.001** | 0.001** | ||

| Yes | 32.3 | 32.3 | ||

| No | 78.8 | 75.0 |

OS overall survival, DFS disease-free surviva, AD adenocarcinoma, SQ Squamous cell carcinoma, LA radical systematic mediastinal lymphadenectomy, LS lymph node sampling

* P < 0.05, **P < 0.001

In the multivariate analysis, forward stepwise Cox regression was used to determine simultaneously the associations between survival and the following potentially prognostic variables: age, sex, histological type, size and location of tumor, lymph node status and method of lymph node dissection. It showed that lymph node metastasis was the unique unfavorable prognostic factor which conferred a relative risk of 4.52 for recurrence and 4.35 for death (P < 0.001).

Discussion

Clinical staging in patients with NSCLC was based on radiologic, bronchoscopic and other preoperative findings, and overstaging or understaging may occur compared to the final surgical-pathologic evaluation (Cetinkaya et al. 2002; Yamazaki et al. 2007). In this study, no patient with pathologic stage M was found, and only patients with T1 were recruited so that we could exclude the interference to prognosis for the migrations of T stage and focus on N status and methods of mediastinal lymph node dissection.

It is not universally held that LA could improve the accuracy of staging. Oda et al. (1998) and Bollen et al. (1993) reported that systemic mediastinal lymph node dissection improved the accuracy of tumor staging. But there was no control group set in the former study, and there was very few lymph nodes dissected in the control group in the latter study. On the contrary, some authors found that LA was of no effect in the accuracy of N stage. For instance, Keller et al. (2000) reported that regardless of the type of lymph node dissection (LA and sampling) performed, the percentage of patients with pathologic N1 or N2 disease was very similar in both groups. In contrast, the number of patients with N2 lymph node involvement at multiple levels was significantly increased in the LA group than that in the sampling group. Izbicki et al. (1995) gave the similar results in a randomized controlled trial. Because the patients with N2 disease at multiple levels had a worse prognosis, LA seems to be essential for identifying these subgroup patients at risk by resecting a sufficient number of lymph nodes. Therefore, these patients can be admitted postoperatively to an adjuvant therapy in time, which is of prognostic significance. In our study, the number of lymph nodes dissected per patient was significantly greater in the LA group than that in the LS group, but there was no difference in improving the accuracy of N staging. This result was consistent with the study by Keller et al. (2000) and Izbicki et al. (1995). But we did not find the difference in the number of patients with multiple levels N2 disease between the LA and the LS groups. One possible reason is that more patients with early stage were enrolled in our study.

The major controversy on the extent of lymph node dissection in early stage NSCLC is whether it could improve the prognosis of patients or not. A Chinese southern lung cancer research center leaded by Dr. Wu (2002) reported their prospective controlled study on different methods of lymph node dissection. Compared with sampling, LA significantly improved the survival rate and reduced the local recurrence and distant metastasis in patients with stage I NSCLC. This study indicated that the earlier stage the patients were at, the more urgent they were required for systemic dissection. In our study, the 5-year overall survival and disease-free survival were 80.4 and 75.5% in the LA group, 61.2 and 59.5% in the LS group. Although LA seems to result in survival benefit, there was no statistically significant difference. Thereby, in the present study, the different methods of mediastinal lymph node dissection did not influence survival. Other studies also support our results. In a recent study by Okada et al. (2006), there was no significant difference in disease-free survival or overall survival between the selective mediastinal dissection group and the complete lymphadenectomy group. Moreover, the postoperative morbidity in the LA group was significantly higher than that in the selective dissection group. This study showed that selective mediastinal dissection was effective and sufficient to patients with clinic stage I NSCLC. Funatsu et al. (1994) reported that radical lymph node dissection resulted in significantly lower 5-year survival than nonradical dissection in patients with T1N0M0 NSCLC and considered that the outcome was associated with immunologic functional changes of lymph nodes.

In our study, LA brought survival benefit to patients with lesions between 2 cm and 3 cm. For patients with lesions between 2 and 3 cm, the 5-year OS was 81.6% with LA and 55.8% with LS, and the 5-year DFS was 77.9% with LA and 52.5% with LS. Both of the difference was significant. In contrast, for patients with lesions of 2 cm or less, both the 5-year OS and DFS were similar. A question to be answered: does LA prevent local recurrence and distant metastasis by dissecting more metastatic lymph nodes? By the subgroup analysis, we found that the number of lymph nodes dissected in patients with lesions between 2 and 3 cm had no significant difference by either LA or LS. Another possible reason was the existence of occult lymph node micrometastasis, which was verified by immunohistochemistrical (Nicholson et al. 1997) and RT-PCR (Salerno et al. 1998) method but sometimes was negative by histopathologic examination. Passlick et al. (1996) had ever pointed out that occult lymph nodes metastasis was the cause of local recurrence in primary local NSCLC, and those patients with occult lymph nodes metastasis had poor prognosis. Ishida et al. (1990) found that the possibility of lymph nodes metastasis strikingly increased as the primary lesion expanded. Based on these studies, we presumed that larger-size lesions could lead to more occult lymph nodes metastasis. So, LA could remove occult metastatic lymph nodes more thoroughly than LS, and consequently prolong the survival of part of patients. Noticeably, our study is of clinical significance for intraoperative decision-making: for patients with clinical stage IA NSCLC, we can precisely measure the tumor size and can use fast pathological technique to determine the T stage from dissected lung tissues during the operation (in this study, 21 patients had fast pathologic diagnosis of T stage, and 20 of them got the consistent diagnosis after operation). For those pathologically verified T1 disease, we can select suitable mode of mediastinal lymph node dissection according to the tumor size.

In our study, there were other interesting findings. Patients with large cell carcinoma and adenosquamous carcinoma had a lower 5-year OS than patients with either adenocarcinoma or squamous carcinoma, which may suggest the feasibility of some adjunctive treatments to them. Many studies indicate that lymph node metastasis meant a bad prognosis to patients with NSCLC (Vansteenkiste et al. 1998; Friedel et al. 2004), and we draw the similar conclusion as well. In multivariate analysis, lymph node metastasis was defined as the only unfavorable prognostic factor by forward stepwise Cox regression.

With the development of surgery techniques, more and more surgeons became interested in a minimally invasive approach to treat patients with early stage NSCLC. This trend might result from the frequency of complications influenced by the extent of dissection. Our study also showed that LS had advantages such as shortening the duration of the operation, reducing the drain secretion and postoperative complications comparing with LA. The results of our study were consistent with those of other studies (Sugi et al. 1998; Okada et al. 2006). LS might be considered as an alternative for curative surgery in the era of minimally invasive surgery. In this study, we also divided the postoperative complications of the LA and LS group into patients with lesion of 2 cm or less and patients with lesion between 2 and 3 cm, there was a trend, although not statistically significant, for the LS group to obtain a lower morbidity than that in the LA group. Therefore, we thought that LS seems a better choice in the treatment for patients with lesions of 2 cm or less intraoperatively pathologically determined T1 diseases who were preoperatively diagnosed as cIA NSCLC.

In conclusion, the most important meaning of the present study was helpful to do clinical decision-making during the operation for cIA NSCLC. According to the tumor size, we can select suitable mediastinal lymph node dissection mode (LA or LS). LS should be performed to patients who had ≤2 cm lesions in T1 diseases for the minimally invasive purpose. When patients had 2–3 cm lesions, LA should be performed for potential better survival. Because of the nonrandomized and retroprospective nature of this study, the value of current study should be reevaluated through prospective randomized multi-center trials.

Abbreviation

- cIA

Clinical stage IA

- DFS

Disease-free survival

- LA

Radical systematic mediastinal lymphadenectomy

- LS

Mediastinal lymph-node sampling

- NSCLC

Non-small cell lung cancer

- OS

Overall survival

References

- Bollen EC, van Duin CJ, Theunissen PH, vt Hof-Grootenboer BE, Blijham GH (1993) Mediastinal lymph node dissection in resected lung cancer: morbidity and accuracy of staging. Ann Thorac Surg 55:961–966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cetinkaya E, Turna A, Yildiz P, Dodurgali R, Bedirhan MA, Gürses A, Yilmaz V (2002) Comparison of clinical and surgical-pathologic staging of the patients with non-small cell lung carcinoma. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 22:1000–1005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedel G, Steger V, Kyriss T, Zoller J, Toomes H (2004) Prognosis in N2 NSCLC. Lung Cancer 45:S45–S53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funatsu T, Matsubara Y, Ikeda S, Hatakenaka R, Hanawa T, Ishida H (1994) Preoperative mediastinoscopic assessment of N factors and the need for mediastinal lymphnode dissection in T1 lung cancer. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 108:321–328 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene FL, Page DL, Fleming ID, Fritz A, Balch CM, Haller DG, Morrow M (2002) AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, 6th edn. Springer, New York [Google Scholar]

- Ishida T, Yano T, Madea K (1990) Strategy for lymphadenectomy in lung cancer 3 cm or less in diameter. Ann Thorac Surg 50:708–713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izbicki JR, Thetter O, Habekost M, Karg O, Passlick B, Kubuschok B, Busch C, Haeussinger K, Knoefel WT, Pantel K et al (1994) Radical systematic mediastinal lymphadenectomy in non-small cell lung cancer: a randomized controlled trial. Br J Surg 81:229–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izbicki JR, Passlick B, Karg O, Bloechle C, Pantel K, Knoefel WT, Thetter O (1995) Impact of radical systemic mediastinal lymphadenectomy on tumor staging in lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg 59:209–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izbicki JR, Passlick B, Pantel K, Pichlmeier U, Hosch SB, Karg O, Thetter O (1998) Effectiveness of radical systematic mediastinal lymphadenectomy in patients with resectable non-small cell lung cancer, results of a prospective randomized trial. Ann Surg 227:138–144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Murray T, Xu J, Thun MJ (2007) Cancer Statistics, 2007. CA Cancer J Clin 57:43–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller SM, Adak S, Wagner H, Johnson DH (2000) Mediastinal lymph node dissection improves survival in patients with stages II and IIIa non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg 70:358–366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martini N, Flehinger BJ (1987) The role of surgery in N2 lung cancer. Surg Clin North Am 67:1037–1049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moutain CF (1997) Revisions in the international system for staging lung cancer. Chest 111:1710–1717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naruke T, Suemasu K, Ishikawa S (1976) Surgical treatment for lung cancer with metastases to mediastinal lymph nodes. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 71:279–285 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naruke T, Tsuchiya R, Kondo H, Asamura H (2001) Prognosis and survival after resection for bronchogenic carcinoma based on the 1997 TNM-staging classification: the Japanese experience. Ann Thorac Surg 71:1759–1764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson AG, Graham AN, Pezzella F, Agneta G, Goldstraw P, Pastorino U (1997) Does the use of immunohistochemistry to identify micrometastasis provide useful information in the staging of node -negative non-small cell lung carcinomas? Lung Cancer 18:231–240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oda M, Watanabe Y, Shimizu J, Murakami S, Ohta Y, Sekido N, Watanabe S, Ishikawa N, Nonomura A (1998) Extent of mediastinal node metastasis in clinical stageI non-small cell lung cancer: the role of systematic nodal dissection. Lung Cancer 22:23–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada M, Sakamoto T, Yuki T, Mimura T, Miyoshi K, Tsubota N (2006) Selective mediastinal lymphadenectomy for clinico-surgical stage I non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg 81:1028–1032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passlick B, Izbicki JR, Kubuschok B, Thetter O, Pantel K (1996) Detection of disseminated lung cancer cells in lymph nodes: impact on staging and prognosis. Ann Thorac Surg 61:177–183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salerno CT, Frizelle S, Niehans GA, Ho SB, Jakkula M, Kratzke RA, Maddaus MA (1998) Detection of occult micrometastases in non-small cell lung carcinoma by reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction. Chest 113:1526–1532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugi K, Nawata K, Fujita N, Ueda K, Tanaka T, Matsuoka T, Kaneda Y, Esato K (1998) Systematic lymph node dissection for clinically diagnosed non-small cell lung cancer less than 2 cm in diameter. World J Surg 22:290–295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vansteenkiste JF, De Leyn PR, Deneffe GJ, Lerut TE, Demedts MG (1998) Clinical prognostic factor in surgically treated stage IIIA-N2 non-small cell lung cancer: analysis of the literature. Lung Cancer 19:3–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y, Huang ZF, Wang SY, Yang XN, Ou W (2002) A randomized trial of systematic nodal dissection in resectable non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer 36:1–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamazaki K, Yoshino I, Yohena T, Kameyama T, Tagawa T, Kawano D, Oba T, Koso H, Maehara Y (2007) Clinically predictive factors of pathologic upstaging in patients with peripherally located clinical stage IA non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer 55:365–369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]