Abstract

Purpose

Breast-conserving therapy (BCT) was developed to improve quality of life (QOL) in early stage breast cancer patients. Except for differences in body image, literature comparing the psychosocial sequelae of BCT with mastectomy is ambiguous and shows a lack of substantial benefits. However, knowledge regarding long term effects of treatment on QOL in breast cancer is very limited as most of the pertinent studies have been performed in the early post-operative period. Therefore we compared QOL in women with breast cancer undergoing BCT versus women undergoing mastectomy over a 5-year period following primary surgery.

Methods

QOL was assessed at 1, 3, and 5 years after diagnosis in a population based cohort of 315 women with early stage breast cancer (UICC stage I-II) from Saarland (Germany) using the EORTC QLQ-C30 questionnaire and the breast cancer specific module BR23.

Results

Breast-conserving therapy was performed in 226 women (72%). After control for potential confounding, women with BCT reported better physical and role functioning, were sexually more active and more satisfied with their body image already at 1 year after diagnosis (all P values < 0.05). Differences in overall QOL and social functioning were gradually increasing over time and became statistically significant only at 5 years.

Conclusions

Whereas some, very specific benefits of BCT, such as a better body image, are already visible very timely after completion of therapy, benefits in broader measures such as psychosocial well-being and overall quality of life gradually increase over time and become fully apparent only in the long run.

Keywords: Breast cancer, Breast-conserving therapy, Cohort study, Epidemiology, Mastectomy, Quality of life

Introduction

Breast-conserving therapy (BCT) is now considered as the standard surgery in early stage breast cancer for which it has been shown to be equivalent to mastectomy with regard to survival (Veronesi et al. 2002). One major reason for developing breast-conserving surgical techniques was to improve quality of life (QOL) in breast cancer patients. However, the expected results of better QOL in BCT patients could not be confirmed yet (Ohsumi et al. 2007; Rowland et al. 2000; Moyer 1997; de Haes et al. 2003; Janz et al. 2005). Except for differences in body image, the literature comparing the psychosocial sequelae of BCT with mastectomy is ambiguous and shows a lack of substantial benefits (de Haes et al. 2003, 1986; McCready et al. 2005; Curran et al. 1998; Poulsen et al. 1997; Schain et al. 1983, 1994; de Haes and Welvaart 1985; Fallowfield et al. 1986; Lasry et al. 1987; Aaronson et al. 1988; Kemeny et al. 1988; Levy et al. 1989; Ganz et al. 1992; Lee et al. 1992).

Hitherto most studies have been performed in the early post-operative period with follow-up periods of less than 2 years. Thus, our knowledge regarding the long term effects on treatment on quality of life is very limited and timing may be an important factor (Ohsumi et al. 2007). Given that meanwhile over 80% women with breast cancer survive 5 and more years (Brenner et al. 2007; Gondos et al. 2007), it is essential to have more information regarding the long term consequences of breast cancer surgery. Therefore, we set up a population-based cohort study to compare quality of life in breast cancer patients undergoing breast-conserving therapy versus women undergoing mastectomy over a 5-year period following primary surgery.

Methods

Study design

This analysis is based on a population-based state-wide cohort of women with breast cancer diagnosed between October 1996 and February 1998 who were residents in the state of Saarland, Germany. Study participants were identified by their clinicians during first hospitalization due to breast cancer treatment. With the exception of two hospitals that did not offer inpatient cancer treatment, all the other 34 hospitals from the study region participated in the recruitment. Further eligibility criteria for recruitment included histologically confirmed invasive breast cancer, age 18–80 years, and sufficient knowledge of the German language. The study protocol was approved by the responsible local and regional ethics committees.

Overall, 458 patients were deemed suitable for participation by their treating physicians and were reported to the study center after they had given written informed consent. Fifty-four women did not meet the inclusion criteria for the following reasons: noninvasive tumor (n = 14), recurrent tumor (n = 13), age over 80 years (n = 7), duplicate report (n = 2), date of diagnosis outside study period (n = 14), or living outside study region (n = 4). Three women died before the interview, and 14 eligible women with breast cancer withdrew their consent to participate in study. In total, 387 women with breast cancer could be recruited briefly after diagnosis, of whom 321 were diagnosed with early stage cancers (UICC stages I-II). Information regarding type of surgery (details see below) was missing in 6 cases leaving 315 women with early stage breast cancer for final analysis and representing approximately 50% of all new incident cases during the recruitment period according to projections by the Saarland Cancer Registry. The study participants did not substantially differ from the source population in terms of stage distribution and basic socio-demographic characteristics with the exception of a slightly higher proportion of younger patients.

Follow-up

Three rounds of active follow-up were conducted during the first 5 years past diagnosis of breast cancer. A first follow-up was initiated 1 year after diagnosis, and we sent a QOL questionnaire (details see below) to each patient. Two years later, that is, 3 years after the cancer diagnosis, the same QOL questionnaire was sent to all respondents of the first follow-up. A third follow-up took place another 2 years later, that is, 5 years after diagnosis. In the 5-year follow-up, the QOL questionnaire was sent to all members of the baseline cohort known to be alive including those who did not participate in the earlier follow-up rounds but did not explicitly rule out any further contacts. Vital status was obtained beforehand from the residents’ registration office to avoid mailings to patients who had died during the follow-up. In all three rounds of follow-up non-respondents were mailed up to two reminders, and contacted by phone if they did not respond after three mailings.

Data collection

Baseline data including patient’s age, education level, marital status, other concurrent chronic medical conditions as well as date of diagnosis were obtained by structured face-to-face interviews. The interviews were conducted in most cases during first hospitalization due to breast cancer. The list of concurrent chronic conditions comprised myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, peripheral vascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, dementia, chronic pulmonary disease, musculoskeletal disorders, arthrosis, connective tissue disease, ulcer disease, liver disease, diabetes, stroke, renal disease, other malign tumor, AIDS as well as visual and hearing impairment (Charlson et al. 1987; Linn et al. 1968). Information regarding tumor stage at time of diagnosis and initial therapy was abstracted from hospital records and from hospital discharge letters.

Quality of life during follow-up was assessed with the Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30 Items (QLQ-C30) of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) (Aaronson et al. 1993) and the breast cancer specific module BR23 also developed by the EORTC (Sprangers et al. 1996). The QLQ-C30 is a validated, brief, self-reporting, cancer-specific measure of quality of life and composed of five multi-item functional scales that evaluate physical, role, emotional, cognitive and social function and one global health status/quality of life scale. Three multi-item symptom scales measure fatigue, pain and nausea/vomiting and six single items assess further symptoms (dyspnea, insomnia, appetite loss, constipation, diarrhea) and financial difficulties. The BR23 module incorporates multi-item scales to assess systemic therapy side effects, arm and breast symptoms, body image, sexual functioning and single items to assess sexual enjoyment, hair loss and future perspective.

In both instruments high functional scores represent better functioning/QOL, whereas a high symptom score indicates more/severe symptoms. The time frame for all scales in the questionnaire was the last week except for items related to sexual activity where a 4-week time frame was applied. In addition to the two established QOL instruments, we specifically asked the women in the context of the 5 year follow-up about their fear of recurrence.

Information regarding prevalence of other concurrent chronic diseases, recurrence of disease as well as subsequent therapeutic procedures such as secondary ablation or breast reconstruction was obtained directly from the patient in the context of the active follow-up. In case of patients lost to follow-up, additional information regarding recurrence of disease was provided by the Saarland Cancer Registry.

Statistical methods

Type of surgery

Type of surgery was classified as either breast-conserving therapy or mastectomy. Breast-conserving therapy included primary breast-conserving surgery as well as breast reconstruction as these two techniques have been reported to yield comparable results with respect to QOL (Cocquyt et al. 2003; Dian et al. 2007; Nano et al. 2005).

Overall and disease free survival

Overall and disease free survival for patients with breast-conserving therapy versus mastectomy was assessed with a multivariate Cox’s proportional hazards model with date of surgery as start of follow-up. The proportional hazards assumption was checked with log-log curves. Baseline variables considered as potential confounders included age, tumor stage, histology, comorbidity, and adjuvant therapy (chemo- and hormonal therapy). Radiation was not included as a covariate as it may be considered a consequence of BCT and thus should not be considered as a confounder.

Quality of life

The scoring of the EORTC QLQ-C30 items was performed according to the EORTC scoring manual (Fayers et al. 1999). All scores were linearly transformed to a 0–100 points scale. In case of missing items, multi-item scores were calculated as the mean of non-missing items if at least half of the items from the corresponding scale had been completed. Analysis of variance was used to test whether QOL differed between women undergoing breast-conserving therapy versus women after mastectomy at 1, 3, and 5 years past diagnosis.

Most symptom scales of the QLQ-C30 and the BR23 refer to systematic treatment effects (such as fatigue, nausea/vomiting, appetite loss, diarrhea, hair loss), thus we restricted the analysis to the function scales (i.e., physical, role, emotional, cognitive, social functioning, body image, sexual activity, future perspectives) and global health/quality of life. Given the sample size of 226 women with BCT and 89 women with mastectomy the study had a power of 88% to detect a difference of 10 points, which is considered to be clinically meaningful (Osoba et al. 1998). Covariates in multivariate analysis included age, tumor stage, histology, comorbidity at time of follow-up, chemo-, and hormonal therapy.

As no baseline QOL data were available, we used the age and gender specific QLQ-C30 data for the German general population published by Schwarz and Hinz (Schwarz and Hinz 2001) to see whether QOL of our study members is within the normal range after the 5-year study period or whether specific limitations, previously described still persist (Arndt et al. 2005). Age standardized reference QOL scores were calculated by weighting the age- and gender-specific mean scores from the reference population according to the age-structure of the breast cancer patients at 5 years after diagnosis within each treatment group.

To assess the potential impact of different non-random missing data mechanisms (Pauler et al. 2003), we reran the analysis in various subsets of the original study population according to participation status, survival status, and recurrence of disease. Repeated measures ANOVA was employed to assess the independent role of treatment, time and their interaction. All analyses were performed with the SAS software (Version 8.2).

Results

Description of the study population

A total of 315 women with early stage breast cancer (UICC I-II) were included in the analysis. Information regarding participation and vital status within each survey is given in Table 1. Among those who survived, QOL data were available in 85% at the end of the 5 year follow-up. In general, responders had initially reported less comorbidity but did not differ from non responders with respect to education, tumor stage, nor type of surgery (data not shown). Women who died during the follow-up tended to be older but among those who survived, no significant age difference was seen with respect to responder status.

Table 1.

Follow-up participation at 1, 3, and 5-year past diagnosis

| Follow-up | Vital status | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alive | Deceased | ||||

| Contacted | Not contacteda | ||||

| Total | Responder | ||||

| Yes | No | ||||

| Year 1 | 311 | 264 | 47 | 0 | 4 |

| Year 3 | 245 | 216 | 29 | 39 | 31 |

| Year 5 | 252 | 219 | 33 | 5 | 58 |

aIn the context of the 3-year follow-up, 39 women who did not participate in the first follow-up were not contacted. Five women, who explicitly declined any further active follow-up, were not contacted at 5 years after diagnosis

Breast-conserving therapy was performed in 226 women (70%) whereas 89 women (30%) underwent mastectomy. Breast-conserving therapy included primary breast-conserving surgery (n = 197) as well as breast reconstruction techniques (n = 29). Breast reconstruction was performed in 27 cases within the first year and in two cases within the second year past diagnosis. The mastectomy group comprised 81 women after primary ablation without reconstruction of the breast as well as eight women undergoing secondary mastectomy after initial BCT. All secondary mastectomies occurred within the first year after diagnosis, that is, before the first round of QOL assessment.

Characteristics of the study population are shown in Table 2. Women undergoing breast-conserving therapy were on average 6 years younger than women undergoing mastectomy at baseline (mean age 56.0 vs. 62.1 years). In addition, the proportion of localized tumors smaller than 2 cm (UICC I) as well as the proportion of ductal carcinoma was higher in the BCT group than in the mastectomy group. The two treatment groups did not significantly differ with respect to education, employment status, marital status, comorbidity, tumor grading, expression of hormone receptors, chemo- and hormonal therapy.

Table 2.

Description of study population by type of surgery according to age, education, social class, marital status, tumor stage, histology, adjuvant therapy

| Characteristic | Mastectomy (n = 89) | Breast-conserving (n = 226) | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||||

| 18–49 | 12 | 13% | 75 | 33% | <0.0001 |

| 50–59 | 22 | 25% | 57 | 25% | |

| 60–69 | 26 | 29% | 61 | 27% | |

| 70+ | 29 | 33% | 33 | 15% | |

| Education (years) | |||||

| 9 | 70 | 79% | 166 | 73% | 0.49a |

| 10 | 10 | 11% | 38 | 17% | |

| 12+ | 8 | 9% | 22 | 10% | |

| Employment status | |||||

| Active job | 17 | 19% | 81 | 36% | 0.44a |

| Unemployed | 5 | 6% | 10 | 4% | |

| Housewife | 48 | 54% | 98 | 43% | |

| Retired | 17 | 19% | 37 | 16% | |

| Marital status | |||||

| With spouse | 46 | 52% | 149 | 66% | 0.35a |

| Without spouse | 43 | 48% | 77 | 34% | |

| Number of concurrent chronic conditionsb | |||||

| 0 | 18 | 20% | 41 | 18% | 0.24a |

| 1 | 20 | 23% | 72 | 32% | |

| 2+ | 51 | 57% | 113 | 50% | |

| UICC stage | |||||

| I | 29 | 33% | 87 | 39% | 0.04a |

| IIA | 28 | 32% | 89 | 39% | |

| IIB | 32 | 36% | 50 | 22% | |

| Grading | |||||

| GI/GII | 53 | 60% | 127 | 56% | 0.94a |

| GIII/GIV | 35 | 40% | 97 | 43% | |

| Histology | |||||

| Lobular | 20 | 23% | 21 | 9% | 0.01a |

| Ductal | 63 | 71% | 182 | 81% | |

| Other | 6 | 7% | 23 | 10% | |

| Receptors | |||||

| Oestrogen | 64 | 72% | 157 | 69% | 0.95a |

| Progesteron | 64 | 72% | 140 | 62% | 0.15a |

| Adjuvant Therapy | |||||

| Chemotherapy | 31 | 35% | 106 | 47% | 0.87a |

| Radiation | 29 | 33% | 195 | 86% | <0.0001a |

| Hormonal | 63 | 71% | 141 | 62% | 0.44a |

aadjusted for age

bMyocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, peripheral vascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, dementia, chronic pulmonary disease, musculoskeletal disorders, arthrosis, connective tissue disease, ulcer disease, liver disease, diabetes, stroke, renal disease, other malign tumor, AIDS, visual and hearing impairment

Overall and disease free survival

Overall, 58 women died during the 5-year follow-up. In crude analysis, women undergoing BCT experienced a 43% lower mortality than women after mastectomy (Table 3). However, this difference in prognosis fully disappeared after controlling for age, tumor stage, histology, comorbidity, and adjuvant therapy. With respect to disease free survival, women after BCT and women after mastectomy again experienced almost identical prognosis once potential confounding was controlled for.

Table 3.

Overall and disease free survival in women with breast cancer over 5 years by type of surgery

| Mastectomy (n = 89) | Breast-conserving (n = 226) | |

|---|---|---|

| Overall survival | ||

| Number of deaths | 23 | 35 |

| Person years | 503 | 1,341 |

| Crude mortality rate (per 100 person years) | 4.57 | 2.61 |

| Relative mortality | ||

| Crude | 1.0 (ref) | 0.57 (0.34–0.97) |

| Adjusteda | 1.0 (ref) | 1.00 (0.47–2.13) |

| Disease free survival | ||

| Number of events | 30 | 52 |

| Person years | 485 | 1316 |

| Crude event rate (per 100 person years) | 6.18 | 3.95 |

| Relative hazard | ||

| Crude | 1.0 (ref) | 0.64 (0.41–1.01) |

| Adjusted§ | 1.0 (ref) | 0.91 (0.48–1.76) |

aadjusted for tumor stage, histology, age, comorbidity, chemotherapy, and hormonal therapy

Quality of life

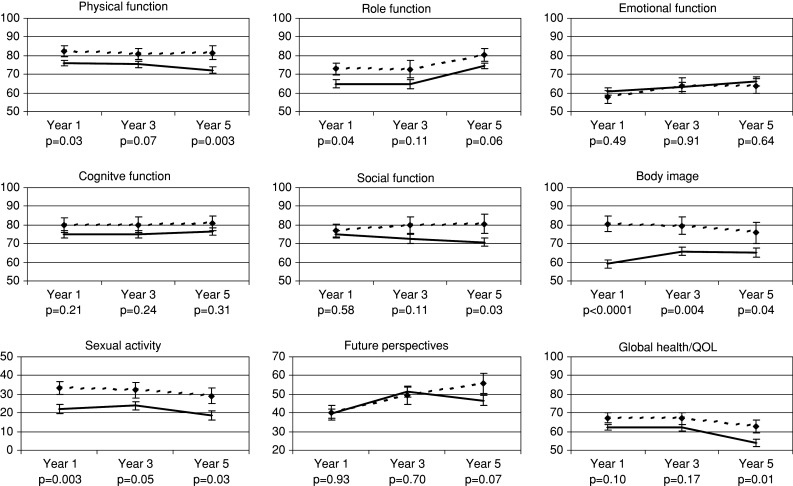

Figure 1 shows the temporal development by type of surgery within the selected dimensions of quality of life. In general, women undergoing breast-conserving therapy tended to report better physical and role functioning, for example, pursuing work, leisure and other daily activities, were sexually more active and more satisfied with their body image. The most striking result is that differences in global health/QOL and social functioning gradually increased over time and became statistically significant only at 5 years after diagnosis. Whereas women after mastectomy and women after breast-conserving therapy reported similar levels of social function at Year 1, social function declined for the mastectomy group and improved for the BCT group over the study period. In contrast, differences in body image were largest at Year 1 but this difference decreased over time. Physical functioning and global health/QOL decreased in both groups, but this decline was greater in the mastectomy group. The temporal development of the item “future perspectives” appeared to be more favorable for the breast conserving group, but the difference did not reach statistical significance. No major differences between the two treatment groups were observed for emotional and cognitive function. Also, women with breast-conserving therapy and women after mastectomy expressed similar levels of concerns regarding fear of recurrence of breast cancer at the end of 5-year follow-up (P = 0.53).

Fig. 1.

Quality of life in women with breast cancer after breast conserving therapy (dotted line) versus mastectomy (solid line) after 1, 3, and 5 years (mean value and standard error; P value adjusted for tumor stage, age, comorbidity, chemotherapy, hormonal therapy)

Further in-depth analysis (data not shown), in which we subsequently restricted the study sample to those who survived and to those who participated in all surveys, did not change the finding that most benefits of breast-conserving therapy over mastectomy increased over time and became fully apparent only after 5 years of follow-up. Similarly, the pattern did not change when we excluded the 29 women after breast reconstruction from analysis and reran the analysis comparing primary breast-conserving surgery versus mastectomy nor when we stratified the study sample according to age.

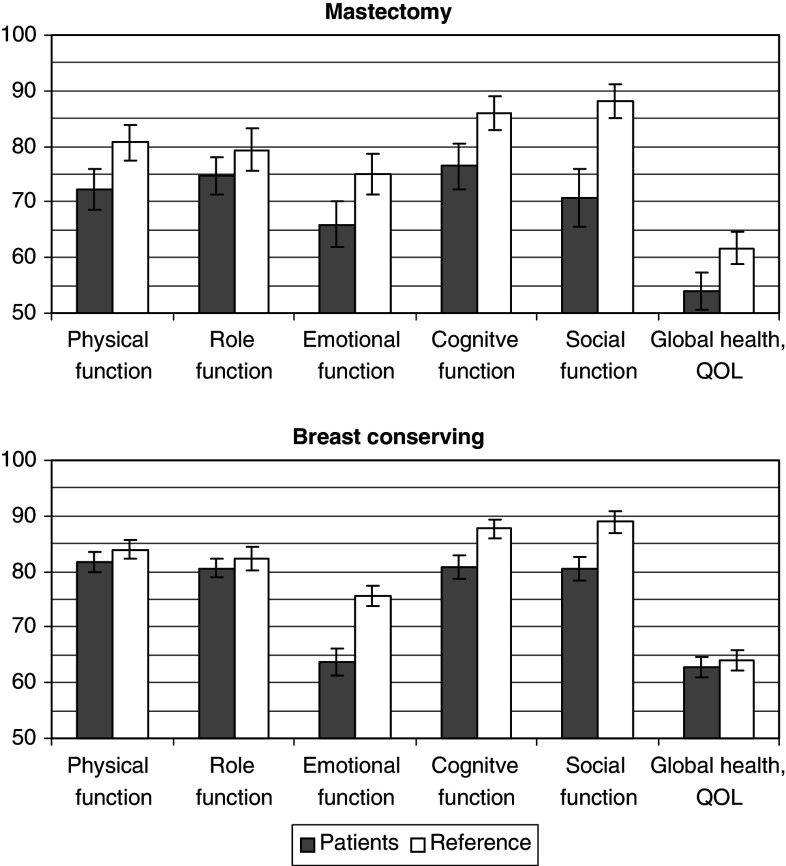

Five years after diagnosis women after breast-conserving therapy and age-matched women from the general population reported virtually identical mean scores of global health/QOL, as well as physical and role function, whereas women after mastectomy tended to reported poorer on almost all function scales of the QOL-C30 than their age-matched peers from the referent population (Fig. 2). Functional deficits irrespective of type of surgery were found for emotional and cognitive function.

Fig. 2.

Quality of life in women with breast cancer 5 years after diagnoses versus age-adjusted reference values derived from women from the general population (Schwarz and Hinz 2001) by type of surgery (means and standard errors)

The better performance of breast-conserving therapy over mastectomy with respect to physical (P = 0.01), role (P = 0.002), and social function (P = 0.001) as well as overall quality of life (P = 0.006), and body image (P < 0.001) could also be observed when we performed a repeated measures analysis where we simultaneously assessed the role of treatment, time and their interaction. Although most items remained fairly constant over time, significant improvements during the 5-years period could be observed with respect to role functioning (P = 0.005) and future perspective (p=0.002). In contrast, overall quality of life declined over time (P = 0.009).

Discussion

The results of this population-based study provide further insight into the long-term development of quality of life in women with early breast cancer according to type of surgery. In particular, our analysis reveals that some, very specific benefits of BCT, such as a better body image, are already visible very timely after completion of therapy whereas benefits in broader measures such as psychosocial well-being and overall quality of life gradually increase over time and become fully apparent only in the long run.

Although the effects of type of surgery on quality of life in women with breast cancer have been widely studied, our knowledge about QOL in the long run is still very limited as most studies either have followed their cohorts for 2 years or less or, in case of longer follow-up, usually have not controlled for wide variations in elapsed time since surgery within studied groups. It is possible that better adjustment after BCT might only become apparent when adaptation to the cancer diagnosis and the burden of adjuvant therapy are long past (Dorval et al. 1998). There are only a few, more recent studies with long term results.

In the study by Engel et al. (2004), mastectomy patients not only had lower body image scores throughout the 5-year study period, but also their role functioning was more limited, they were less sexually active, felt insecure, avoided contact with people, and their daily habits were affected to a greater extent. In addition, improvements over time in QOL were stronger in women undergoing BCT than in women after mastectomy supporting our main finding that the full advantages with respect to QOL in patients receiving BCT may become apparent only after a period of several years. Further support for our results comes from another study from Germany, in which BCT was associated with better physical and social functioning after a mean follow-up period of over 4 years (Härtl et al. 2003).

The longitudinal analysis in our study showed that, irrespective of type of breast surgery, role function and future perspective improved over time whereas overall quality of life declined. While the positive development with respect to role function and future perspective is likely to reflect a gradual recovery from the trauma of cancer diagnosis and a growing future perspective, the decline of overall QOL over time is more likely to be seen in the context of ageing related loss of autonomy and poorer health as suggested by reference data derived from the general population (Schwarz and Hinz 2001). However, functional deficits seem to persist in breast cancer survivors with respect to emotional and cognitive function. This is in line with previous findings that breast cancer survivors report being overly stressed and worried about the future, and having little control over the world (Bloom et al. 2004; Tomich and Helgeson 2002).

Breast-conserving therapy was performed in over 70% of all women with early breast cancer in our study. Thus, the vast majority of all women with early stage breast cancer had been offered tissue sparing surgery in the study region. The small number of women undergoing mastectomy was limiting further subgroup specific analysis, such as age specific differences. The study findings are further limited by the observational study design and lack of baseline QOL assessment prior to the breast cancer diagnosis. However, our survival analysis indicates that we successfully removed potential confounding due to the non- randomized study design. Similarly, we controlled for differences in health status and comorbidity in all analyses. Whereas it is almost impossible to derive valid QOL baseline data from cancer patients in retrospect, the comparison with age matched reference data as employed is considered as an appropriate proxy (Fayers 2001). Further strengths of our study include the high overall response proportions, the state-wide recruitment of patients from a wide range of hospitals and the application of a well established instrument to assess health-related quality of life including breast cancer specific issues.

In summary, the findings from this study may have important implications for clinical practice as it challenges former conclusions that mastectomy and BCT are essentially equivalent choices in terms of QOL (Rowland et al. 2000; Janz et al. 2005). Although our study included follow-up of breast cancer patients over longer time periods than the most previous studies, studies with even longer-term follow-up might be needed to fully depict the potential benefits of breast-conserving therapy over mastectomy in early stage breast cancer.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by two grants of the German Cancer Foundation (Deutsche Krebshilfe), Project Nos. 70-1816, 70-2413. The funding agency had no involvement in the study design; nor in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; nor in the writing of the manuscript; and nor the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

References

- Aaronson NK, Bartelink H, van Dongen JA, van Dam FS (1988) Evaluation of breast conserving therapy: clinical, methodological and psychosocial perspectives. Eur J Surg Oncol 14:133–140 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, Bullinger M, Cull A, Duez NJ, Filiberti A, Flechtner H, Fleishman SB, de Haes JCJM, Kaasa S, Klee M, Osoba D, Razavi D, Rofe PB, Schraub S, Sneeuw K, Sullivan M, Takeda F (1993) The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst 85:365–376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arndt V, Merx H, Stegmaier C, Ziegler H, Brenner H (2005) Persistence of restrictions in quality of life from the first to the third year after diagnosis in women with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 23:4945–4953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloom JR, Stewart SL, Chang S, Banks PJ (2004) Then and now: quality of life of young breast cancer survivors. Psychooncology 13:147–160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner H, Gondos A, Arndt V (2007) Recent major progress in long-term cancer patient survival disclosed by modeled period analysis. J Clin Oncol 25:3274–3280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR (1987) A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 40:373–383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cocquyt VF, Blondeel PN, Depypere HT, Van De Sijpe KA, Daems KK, Monstrey SJ, Van Belle SJ (2003) Better cosmetic results and comparable quality of life after skin-sparing mastectomy and immediate autologous breast reconstruction compared to breast conservative treatment. Br J Plast Surg 56:462–470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran D, van Dongen JP, Aaronson NK, Kiebert G, Fentiman IS, Mignolet F, Bartelink H (1998) Quality of life of early-stage breast cancer patients treated with radical mastectomy or breast-conserving procedures: results of EORTC Trial 10801. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC), Breast Cancer Co-operative Group (BCCG). Eur J Cancer 34:307–314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dian D, Schwenn K, Mylonas I, Janni W, Friese K, Jaenicke F (2007) Quality of life among breast cancer patients undergoing autologous breast reconstruction versus breast conserving therapy. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 133:247–252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorval M, Maunsell E, Deschenes L, Brisson J (1998) Type of mastectomy and quality of life for long term breast carcinoma survivors. Cancer 83:2130–2138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel J, Kerr J, Schlesinger-Raab A, Sauer H, Hölzel D (2004) Quality of life following breast-conserving therapy or mastectomy: results of a 5-year prospective study. Breast J 10:223–231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fallowfield LJ, Baum M, Maguire GP (1986) Effects of breast conservation on psychological morbidity associated with diagnosis and treatment of early breast cancer. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 293:1331–1334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fayers PM (2001) Interpreting quality of life data: population-based reference data for the EORTC QLQ-C30. Eur J Cancer 37:1331–1334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fayers PM, Aaronson N, Bjordal K, Curran D, Groenvold M (1999) The EORTC QLQ-C30 Scoring Manual, 2 edn. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, Brussels [Google Scholar]

- Ganz PA, Schag AC, Lee JJ, Polinsky ML, Tan SJ (1992) Breast conservation versus mastectomy. Is there a difference in psychological adjustment or quality of life in the year after surgery? Cancer 69:1729–1738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gondos A, Arndt V, Holleczek B, Stegmaier C, Ziegler H, Brenner H (2007) Cancer survival in Germany and the United States at the beginning of the 21st century: an up-to-date comparison by period analysis. Int J Cancer 121:395–400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Haes JC, Welvaart K (1985) Quality of life after breast cancer surgery. J Surg Oncol 28:123–125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Haes JC, van Oostrom MA, Welvaart K (1986) The effect of radical and conserving surgery on the quality of life of early breast cancer patients. Eur J Surg Oncol 12:337–342 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Haes JC, Curran D, Aaronson NK, Fentiman IS (2003) Quality of life in breast cancer patients aged over 70 years, participating in the EORTC 10850 randomised clinical trial. Eur J Cancer 39:945–951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Härtl K, Janni W, Kästner R, Sommer H, Strobl B, Rack B, Stauber M (2003) Impact of medical and demographic factors on long-term quality of life and body image of breast cancer patients. Ann Oncol 14:1064–1071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janz NK, Mujahid M, Lantz PM, Fagerlin A, Salem B, Morrow M, Deapen D, Katz SJ (2005) Population-based study of the relationship of treatment and sociodemographics on quality of life for early stage breast cancer. Qual Life Res 14:1467–1479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemeny MM, Wellisch DK, Schain WS (1988) Psychosocial outcome in a randomized surgical trial for treatment of primary breast cancer. Cancer 62:1231–1237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasry JC, Margolese RG, Poisson R, Shibata H, Fleischer D, Lafleur D, Legault S, Taillefer S (1987) Depression and body image following mastectomy and lumpectomy. J Chronic Dis 40:529–534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MS, Love SB, Mitchell JB, Parker EM, Rubens RD, Watson JP, Fentiman IS, Hayward JL (1992) Mastectomy or conservation for early breast cancer: psychological morbidity. Eur J Cancer 28A:1340–1344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy SM, Herberman RB, Lee JK, Lippman ME, d’Angelo T (1989) Breast conservation versus mastectomy: distress sequelae as a function of choice. J Clin Oncol 7:367–375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linn BS, Linn MW, Gurel L (1968) Cumulative illness rating scale. J Am Geriatr Soc 16:622–626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCready D, Holloway C, Shelley W, Down N, Robinson P, Sinclair S, Mirsky D (2005) Surgical management of early stage invasive breast cancer: a practice guideline. Can J Surg 48:185–194 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyer A (1997) Psychosocial outcomes of breast-conserving surgery versus mastectomy: a meta-analytic review. Health Psychol 16:284–298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nano MT, Gill PG, Kollias J, Bochner MA, Malycha P, Winefield HR (2005) Psychological impact and cosmetic outcome of surgical breast cancer strategies. ANZ J Surg 75:940–947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohsumi S, Shimozuma K, Kuroi K, Ono M, Imai H (2007) Quality of life of breast cancer patients and types of surgery for breast cancer—current status and unresolved issues. Breast Cancer 14:66–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osoba D, Rodrigues G, Myles J, Zee B, Pater J (1998) Interpreting the significance of changes in health-related quality-of-life scores. J Clin Oncol 16:139–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pauler DK, McCoy S, Moinpour C (2003) Pattern mixture models for longitudinal quality of life studies in advanced stage disease. Stat Med 22:795–809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulsen B, Graversen HP, Beckmann J, Blichert-Toft M (1997) A comparative study of post-operative psychosocial function in women with primary operable breast cancer randomized to breast conservation therapy or mastectomy. Eur J Surg Oncol 23:327–334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowland JH, Desmond KA, Meyerowitz BE, Belin TR, Wyatt GE, Ganz PA (2000) Role of breast reconstructive surgery in physical and emotional outcomes among breast cancer survivors. J Natl Cancer Inst 92:1422–1429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schain WS, d’Angelo TM, Dunn ME, Lichter AS, Pierce LJ (1994) Mastectomy versus conservative surgery and radiation therapy. Psychosocial consequences. Cancer 73:1221–1228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schain W, Edwards BK, Gorrell CR, de Moss EV, Lippman ME, Gerber LH, Lichter AS (1983) Psychosocial and physical outcomes of primary breast cancer therapy: mastectomy vs. excisional biopsy and irradiation. Breast Cancer Res Treat 3:377–382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz R, Hinz A (2001) Reference data for the quality of life questionnaire EORTC QLQ-C30 in the general German population. Eur J Cancer 37:1345–1351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprangers MA, Groenvold M, Arraras JI, Franklin J, te Velde A, Muller M, Franzini L, Williams A, de Haes HC, Hopwood P, Cull A, Aaronson NK (1996) The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer breast cancer-specific quality-of-life questionnaire module: first results from a three-country field study. J Clin Oncol 14:2756–2768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomich PL, Helgeson VS (2002) Five years later: a cross-sectional comparison of breast cancer survivors with healthy women. Psychooncology 11:154–169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veronesi U, Cascinelli N, Mariani L, Greco M, Saccozzi R, Luini A, Aguilar M, Marubini E (2002) Twenty-year follow-up of a randomized study comparing breast-conserving surgery with radical mastectomy for early breast cancer. N Engl J Med 347:1227–1232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]