Abstract

Purpose

This study was conducted to evaluate the prognostic significance of CD44v5 and CD44v6 in resectable colorectal cancer.

Materials and methods

Membranous CD44v5 and CD44v6 levels were measured by an immunoenzymatic assay in tumors and surrounding mucosal samples obtained from 105 patients with resectable colorectal carcinomas.

Results

There were no significant differences of CD44v5 levels between tumors [median: 3.2 (range: 0.9–83.5) ng/mg protein) and surrounding mucosal samples (3 (3–146.2) ng/mg protein]. However, tumor samples showed significantly higher CD44v6 levels [19.5 (2.2–562.9) ng/mg protein] than mucosal samples [5 (5–230) ng/mg protein] (P=0.0001). Patients with higher CD44v5 or CD44v6 content in tumor samples had a considerably shorter relapse-free survival (P<0.05, for both). Patients with a higher CD44v6 content also had a shorter relapse-free and overall survival in the multivariate analysis (P<0.05).

Conclusion

The results of this study suggest a role of CD44v5 and CD44v6 in colorectal cancer progression. Membranous CD44v levels in primary tumors, measured by immunoenzymatic assay, may contribute to a more precise prognostic estimation in patients with resectable colorectal cancer.

Keywords: Cell adhesion, CD44, Colorectal cancer, Immunoenzymatic assay

Introduction

CD44 is one of the most important cell-surface adhesion molecules known to date. It consists of a transmembrane glycoprotein expressed in many normal tissues by cells of epithelial, mesenchymal and hematopoietic origin. CD44 is involved in a number of physiological processes such as cell-cell and cell-matrix adhesion, hematopoiesis, lymphocyte homing and activation, and tumor metastasis (Naot et al. 1997; Screaton et al. 1992). CD44 participates in a large number of related molecular processes, involving specific adhesion to hyaluronic acid, collagen, fibronectin and sulphated proteoglycans, cell migration, and signal transduction. There are two types of CD44: a standard isoform (CD44 s) and a variant isoform (CD44v). The CD44 family of molecules is encoded by a complex gene, located on chromosome 11p13, that contains 20 exons. Ten of them are constitutively expressed on almost all cell types to produce a heavily glycosylated 85–90 kD isoform known as the standard form (CD44 s). Exons 6–15 can be alternatively spliced to produce various isoforms, called CD44 variants (v1–v10) (Naot et al. 1997; Screaton et al. 1992). CD44s, the constant portion of CD44, is expressed by most epithelial and non-epithelial tissues, whereas the expression of the variant forms is far more restricted.

Although in humans the specific functions of CD44v remain unclear, it has been shown that it may act as a metastasis-related molecule with multiple functions, such as cell-cell and cell-extracellular matrix adhesion, cell migration, and presentation of growth factors and cytokines (Herrlich et al. 1993; Naot et al. 1997; Sneath and Mangham 1998). In addition, clinicopathological studies have revealed that the expression of individual exon variants is altered in several malignancies. Thus, for example, the expression of CD44v9 in gastric cancer (Mayer et al. 1993), and CD44v6 in non-Hodgkin lymphoma (Stauder et al. 1995), gastric cancer (Yamaguchi et al. 2002), breast cancer (Kaufmann et al. 1995) or laryngeal epidermoid carcinoma (Guler et al. 2002) has been associated with a shorter survival.

CD44 glycoproteins are overexpressed in colorectal cancer (Heider et al. 1993; Mulder et al. 1994; Ropponen et al. 1998; Wielenga et al. 2000a; Yamaguchi et al. 1996). It has been demonstrated that this overexpression is an early event in the colorectal adenoma-carcinoma sequence (Kim et al. 1994; Wielenga et al. 1993). However, the prognostic role of CD44 variants in colorectal cancer has been subject to conflicting viewpoints. Several immunohistochemical studies have shown that CD44 expression could be of clinical value in colorectal cancer to predict the risk of recurrence and metastasis. In these studies, antibodies recognizing different CD44v isoforms, i.e., CD44v3 (Kuniyasu et al. 2001; Ropponen et al. 1998; Wielenga et al. 2000b), CD44v6 (Mulder et al. 1994; Ropponen et al. 1998; Wielenga et al. 1998), and CD44v8–10 (Yamaguchi et al. 1996), all gave similar results. Nevertheless, also using immunohistochemical assays (Coppola et al. 1998; Gotley et al. 1996; Koretz et al. 1995), reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction, or Southern blotting methods (Jungling et al. 2002; Morrin and Delaney 2002), no correlation has been found between CD44v6 expression and prognosis. In addition, it has been suggested that distant metastases show downregulation of the CD44v6 expression in comparison with primary tumors (Finke et al. 1995; Nanashima et al. 2001).

In the present work, using an immunoenzymatic assay, we examine the membranous levels of CD44v5 and CD44v6 in a series of primary tumors and in surrounding non-neoplastic mucosal samples of patients with resectable colorectal cancer, their possible relationship with clinicopathological tumoral parameters, and their potential prognostic significance.

Material and methods

Patients and tissue specimen handling

Samples of colorectal carcinoma and surrounding mucosa were obtained from 105 consecutive patients with resectable colorectal cancer (R0, according to recommendations from the Union International Contra la Cancrum) (Hermaneck and Sobin 2002). Clinical-pathological and biological features of the tumors are listed in Table 1. Tumors were staged according to Dukes’ (Dukes 1932) and Broders’ (Broders 1925) classifications. The mean follow-up period was 15 months (range, 5–61 months). Adjuvant therapy with 5-fluorouracil and levamisole was given to patients with Dukes’ C tumors, and locoregional radiotherapy was given to those with rectal tumors. Thirty of 105 patients developed tumor recurrence (21 as distant metastases, nine as local recurrence, and both in16 patients), of whom 20 died from causes directly related to it.

Table 1.

CD44v5 content in surrounding mucosa and tumor from 105 resectable colorectal carcinomas: correlation with clinicopathological parameters (n.s. not significant)

| Patients and tumors characteristics | No. | CD44v5 surrounding mucosa contenta | CD44v5 tumor contentb | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (ng/mg prot) | (ng/mg prot) | ||||||||

| Median | Mean | Range | P | Median | Mean | Range | P | ||

| Total | 105 | 3.0 | 13.0 | 3.0–146.2 | 3.2 | 10.8 | 0.9–83.5 | ||

| Age (years) | n.s. | n.s. | |||||||

| ≤65 | 23 | 3.0 | 12.1 | 3.0–60.6 | 3.0 | 7.2 | 1.4–24.2 | ||

| >65 | 82 | 3.0 | 13.3 | 3.0–146.2 | 3.7 | 11.7 | 0.9–83.5 | ||

| Sex | n.s. | n.s. | |||||||

| Female | 65 | 3.0 | 11.7 | 3.0–146.2 | 3.0 | 10.6 | 0.9–83.5 | ||

| Male | 40 | 3.0 | 15.3 | 3.0–89.0 | 3.8 | 11.0 | 1.3–57.5 | ||

| Tumor location | n.s. | 0.017 | |||||||

| Right colon | 38 | 3.0 | 6.3 | 3.0–46.5 | 3.0 | 7.3 | 0.9–68.9 | ||

| Left colon | 35 | 3.0 | 15.8 | 3.0–146.2 | 3.7 | 9.8 | 2.8–39.5 | ||

| Rectum | 32 | 3.0 | 16.1 | 3.0–89.0 | 8.2 | 15.0 | 2.9–83.5 | ||

| Histological grade | n.s. | n.s. | |||||||

| Well diff. | 26 | 3.0 | 8.9 | 3.0–60.6 | 5.5 | 9.8 | 3.0–39.5 | ||

| Mod. diff. | 72 | 3.0 | 13.8 | 3.0–146.2 | 3.0 | 10.4 | 1.3–83.5 | ||

| Poorly diff. | 7 | 3.0 | 20.6 | 3.0–64.5 | 11.1 | 17.8 | 0.9–57.5 | ||

| Dukes stage | n.s. | n.s. | |||||||

| A | 14 | 3.0 | 6.5 | 3.0–33.5 | 3.0 | 8.6 | 3.0–39.5 | ||

| B | 56 | 3.0 | 11.5 | 3.0–67.3 | 3.5 | 10.5 | 1.3–83.5 | ||

| C | 28 | 3.0 | 19.9 | 3.0–146.2 | 3.0 | 11.5 | 0.9–68.9 | ||

| D | 7 | 3.0 | 11.6 | 3.0–38.4 | 6.8 | 14.5 | 3.0–33.8 | ||

| DNA ploidy status | n.s. | n.s. | |||||||

| Diploid | 35 | 3.0 | 13.5 | 3.0–146.2 | 3.0 | 10.6 | 0.9–68.9 | ||

| Aneuploid | 35 | 3.0 | 11.9 | 3.0–66.0 | 8.1 | 11.2 | 2.8–83.5 | ||

| Unknown | 35 | ||||||||

| S-phase fraction | n.s. | n.s. | |||||||

| Low (≤14%) | 38 | 3.0 | 12.3 | 3.0–146.2 | 3.0 | 9.9 | 0.9–57.5 | ||

| High (>14%) | 37 | 3.0 | 14.3 | 3.0–89.0 | 4.1 | 12.4 | 2.8–83.5 | ||

| Unknown | 30 | 3.0 | |||||||

aMedian value of CD44v5 content in surrounding mucosa

bMedian value of tumor CD44v5 content

Samples were removed from the tumors, avoiding grossly necrotic tissues, and from a region of surrounding mucosa at least 2 cm away. The surrounding mucosa was found to be macroscopically and microscopically free from neoplastic growth. Immediately after surgical resection, samples were processed for pathological examination while the remainder tissue was washed with a cold saline solution, divided into aliquots, rapidly transported on ice to the laboratory, and stored at −70 °C pending biochemical and cytochemical studies.

Flow cytometric DNA analysis

DNA content was evaluated in 70 tumors by flow cytometry (Becton Dickinson, San José, Calif., USA) on nuclei obtained from tissues and stained with propidium iodide. DNA ploidy was expressed as the DNA Index. Proliferative activity was expressed as the fraction of cells in the S-phase of the cell cycle and calculated according to recommendations of the DNA Cytometry Consensus Conference (Hedley et al. 1993), with the CellFit software program (Becton Dickinson). Median S-phase fraction value was used as the cut-off point. Tumors were divided into those with a high or a low S-phase fraction.

Tissue processing and CD44v5 and CD44v6 assay

Specimens from neoplastic and normal surrounding tissues were processed at the same time. They were pulverized with a microdismembrator (Braun, Melsungen, Germany) at −70 °C and homogenized with a glass-Teflon (E.I. du Pont de Nemours, Wilmington, USA) potter in TRIS-HCL buffer (TRIS 10 mM, ethylenediamine tetra-acetic acid 1.5 mM, 10% glycerol, 0.1% monothioglycerol) at pH 7.4. Homogenates were centrifuged at 800 g for 10 min at 4 °C, and the supernatant was ultracentrifuged at 100,000 g for 60 min at 4 °C. We obtained a supernatant containing the cytosol and a precipitate with the membranes, which were tested for CD44v5 and CD44v6. Both glycoproteins were assayed on cell surfaces by ELISAs from Bender MedSystems (Vienna, Austria), using the monoclonal antibodies VFF8 and VFF7 for CD44v5 and CD44v6, respectively. The manufacturer indicates a sensitivity of 0.22 ng/ml and 0.09 ng/ml, an overall intra-assay coefficient of 3.6% and 3.0%, and an inter-assay coefficient of 5.8% and 4.2% for the CD44v5 and CD44v6, respectively. The protein content was quantified with the Bradford method (Bradford 1976). Results are expressed as nanograms of CD44v5/CD44v6 per milligram of protein.

Statistical analysis

After analyzing the distribution of membranous CD44v5/CD44v6 values by the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, non-parametric rank methods were used. CD44v5/CD44v6 content was expressed as mean, median, and range. Differences between tumor tissues and paired normal mucosa samples were compared using Wilcoxon’s signed rank test. Patients were subdivided into groups based on different clinical or pathological parameters. Comparison of the CD44v5/CD44v6 levels between groups was made with the Mann Whitney and Kruskal-Wallis test. The differences in percentages were examined by using the χ2 test with Yates’ correction when necessary. Probabilities of relapse-free and overall survival were calculated with the Kaplan-Meier method (Kaplan and Meier 1958). Differences between curves were evaluated with the log-rank test (Mantel and Myers 1971). Cox regression model was also used to examine several combinations and interactions of prognostic factors in a multivariate analysis. Prognostic effects were expressed as relative risk supplemented with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Differences were considered significant at P<0.05.

Results

There was a wide variability of CD44v5 levels in surrounding mucosal samples (3.0–146.2 ng/mg protein) and in tumors (0.9–83.5 ng/mg protein). Likewise, CD44v6 levels ranged widely in non-neoplastic mucosal samples (5–230 ng/mg protein) as well as in tumors (2.2–562.9 ng/mg protein). There were no significant variations of CD44v5 levels between tumors and surrounding mucosal samples (median: 3.2 vs 3 ng/mg protein). However, tumor samples showed significantly higher CD44v6 levels than mucosal samples (median: 19.5 vs 5 ng/mg protein; P<0.001). On the other hand, there was a weak but significantly positive correlation between CD44v5 (r sub S=0.363; P=0.0001) and CD44v6 (r sub S=0.247; P=0.011) levels in surrounding mucosal samples and in the corresponding tumors.

Table 1 shows the distribution of CD44v5 levels in non-neoplastic mucosal samples and in tumors, in relation to patient and tumor characteristics including age, sex, tumor location, Dukes’ stage, histological grade, DNA ploidy, and S-phase fraction. Our results did not show any significant correlation between CD44v5 levels in surrounding mucosa and any of those parameters. In tumors, CD44v5 levels only correlated appreciably with the anatomical site, with higher levels found in distal colon and rectum than in proximal colon (P=0.017).

Table 2 shows the distribution of CD44v6 levels in non-neoplastic mucosal samples and in tumors. As can be seen in these tables, in both types of tissue samples CD44v6 levels did not correlate with any of the clinicopathological characteristics studied.

Table 2.

CD44v6 content in surrounding mucosa and tumor from 105 resectable colorectal carcinomas: correlation with clinicopathological parameters (n.s. not significant)

| Patients and tumors characteristics | No. | CD44v6 surrounding mucosa contenta | CD44v6 tumor contentb | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (ng/mg prot) | (ng/mg prot) | ||||||||

| Median | Mean | Range | P | Median | Mean | Range | P | ||

| Total | 105 | 5.0 | 10.4 | 5.0–230.0 | 19.5 | 37.2 | 2.2–562.9 | ||

| Age (years) | n.s. | n.s. | |||||||

| ≤65 | 23 | 5.0 | 15.6 | 5.0–230.0 | 13.9 | 29.2 | 4.6–137.0 | ||

| >65 | 82 | 5.0 | 8.5 | 5.0–134.7 | 22.4 | 39.5 | 2.2–562.9 | ||

| Sex | |||||||||

| Female | 65 | 5.0 | 8.3 | 5.0–230.0 | 14.2 | 34.1 | 2.2–562.9 | ||

| Male | 40 | 5.0 | 12.8 | 5.0–134.7 | 24.6 | 42.3 | 5.0–196.8 | ||

| Tumor location | n.s. | n.s. | |||||||

| Right colon | 38 | 5.0 | 7.6 | 5.0–230.0 | 12.7 | 23.8 | 2.2–137.0 | ||

| Left colon | 35 | 5.0 | 8.7 | 5.0–134.7 | 15.0 | 41.4 | 5.0–562.9 | ||

| Rectum | 32 | 5.0 | 14.6 | 5.0–230.0 | 29.2 | 47.7 | 5.00–196.8 | ||

| Histological grade | n.s. | n.s. | |||||||

| Well diff. | 26 | 5.0 | 7.6 | 5.0–72.8 | 23.2 | 54.1 | 5.0–562.9 | ||

| Mod. diff. | 72 | 5.0 | 11.2 | 5.0–230.0 | 14.6 | 30.8 | 4.6–196.8 | ||

| Poorly diff. | 7 | 5.0 | 7.8 | 5.0–24.6 | 19.5 | 40.3 | 2.2–173.3 | ||

| Dukes stage | n.s. | n.s. | |||||||

| A | 14 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0–5.0 | 16.4 | 33.2 | 5.0–134.0 | ||

| B | 56 | 5.0 | 12.9 | 5.0–230.0 | 23.9 | 44.9 | 5.0–562.9 | ||

| C | 28 | 5.0 | 7.4 | 5.0–72.8 | 6.9 | 26.7 | 2.2–173.3 | ||

| D | 7 | 5.0 | 7.8 | 5.0–24.6 | 27.8 | 25.8 | 5.0–51.8 | ||

| DNA ploidy status | n.s. | n.s. | |||||||

| Diploid | 35 | 5.0 | 9.1 | 5.0–134.7 | 21.1 | 41.1 | 2.2–562.9 | ||

| Aneuploid | 35 | 5.0 | 11.9 | 5.0–230.0 | 14.9 | 29.5 | 5.0–133.3 | ||

| Unknown | 35 | ||||||||

| S-phase fraction | n.s. | n.s. | |||||||

| Low (≤14%) | 38 | 5.0 | 7.6 | 5.0–72.8 | 18.9 | 40.9 | 2.2–562.9 | ||

| High (>14%) | 37 | 5.0 | 14.6 | 5.0–230.0 | 22.2 | 30.4 | 5.0–133.3 | ||

| Unknown | 30 | ||||||||

aMedian value of CD44v6 content in surrounding mucosa

bMedian value of tumor CD44v6 content

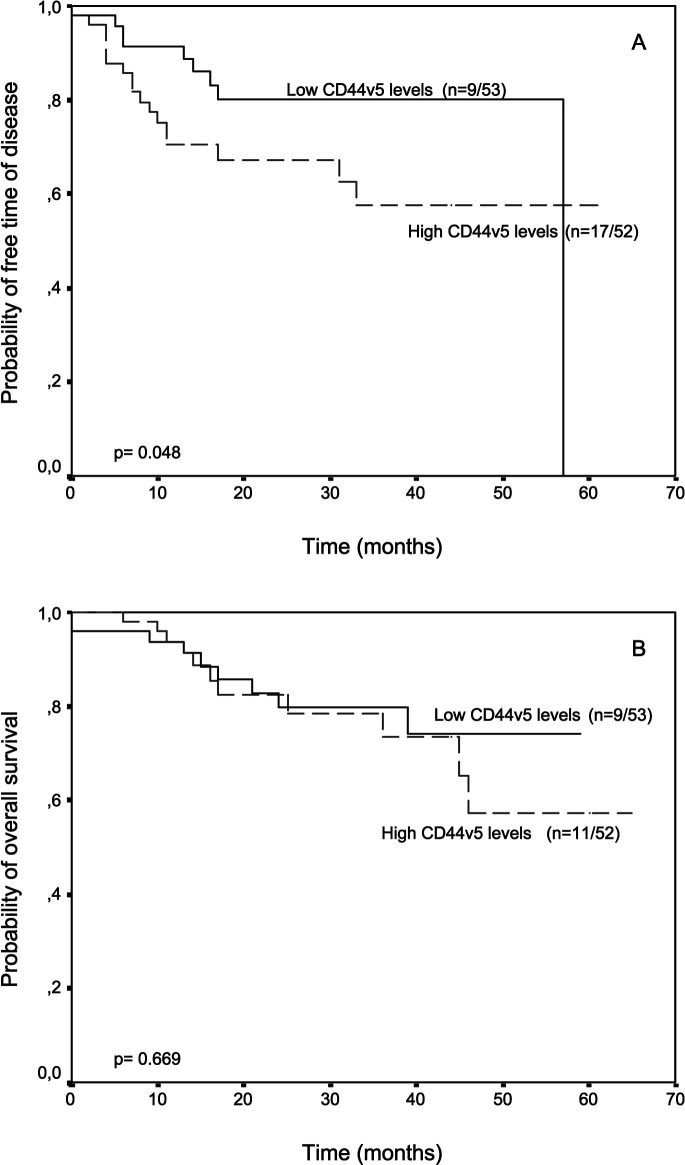

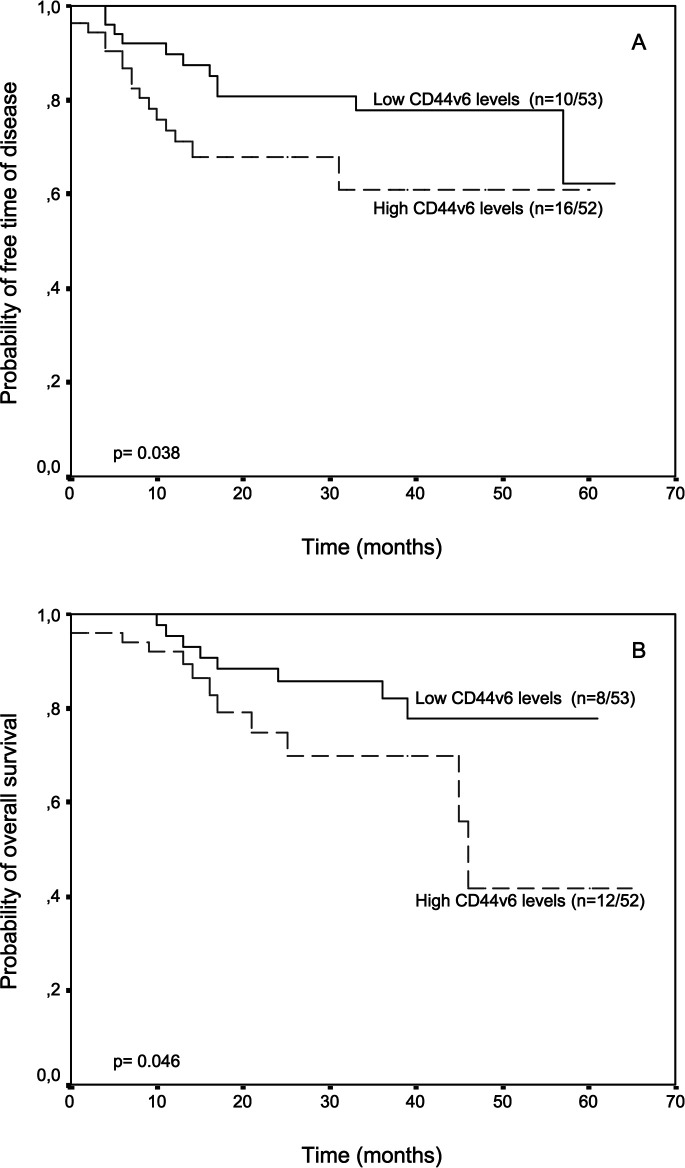

The potential association between CD44v5 or CD44v6 levels in tumors and relapse-free and overall survival was evaluated in the patients included in the present investigation. Patients were divided into two groups according to the corresponding median CD44v levels. We did not find any relationship between CD44v levels in surrounding mucosal samples and patients’ outcome (data not shown). However, there was a significant correlation between CD44v levels in tumor samples and patients outcome. Thus, patients with higher CD44v5 levels in tumors had a significantly shorter relapse-free survival than patients with lower CD44v5 levels (P=0.048) (Fig. 1), whereas patients with higher CD44v6 content in tumors had both significantly shorter relapse-free and overall survival than patients with lower CD44v6 levels (P=0.038 and P=0.046, respectively) (Fig. 2). Multivariate analysis according to Cox’s model confirmed that CD44v6 was significantly associated with both relapse-free and overall survival (Table 3)

Fig. 1A,B.

Probability of A relapse free and B overall survival as a function of tumor CD44v5 levels in 105 patients with resectable colorectal carcinomas

Fig. 2A,B.

Probability of A relapse free and B overall survival as a function of tumor CD44v6 levels in 105 patients with resectable colorectal carcinomas

Table 3.

Relapse-free survival and overall survival, according to multivariate analysis (Cox’s proportional hazards model) of prognostic covariates (RR relative risk, CI confidence interval)

| Tumor characteristics | Relapse-free survival | Overall survival | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RR | CI (95%) | P | RR | CI (95%) | P | |

| Age (years) | 0.006 | 0.006 | ||||

| <65 | 1 | 1 | - | |||

| >65 | 5.3 | 1.2–23.8 | 8.3 | 1–65 | ||

| Dukes stage | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | ||||

| A | 1 | - | 1 | - | ||

| B | 3.3 | 0.4–27.3 | 2.7 | 0.3–22.6 | ||

| C | 16.0 | 2.0–128.0 | 15 | 1.8–123.7 | ||

| D | 27.3 | 2.9–257.3 | 28.5 | 2.7–299.1 | ||

| CD44v6 | ||||||

| Negative | 1 | - | 0.03 | 1 | - | 0.02 |

| Positive | 2.4 | 1.2–5.7 | 2.9 | 1.1–7.9 | ||

Discussion

This is, to the best of our knowledge, the first study designed to investigate the value of membranous CD44v levels in tumors, measured by immunoenzymatic assay, to predict outcome in patients with colorectal cancer. Our results show that higher CD44v5 or CD44v6 are associated with poor patient outcome.

Our results demonstrate significantly higher CD44v6 levels in tumors than in surrounding mucosal samples. This is in accordance with previous reports (Llaneza et al. 2000), and seems to indicate a possible role of CD44v6 in the progression of colorectal carcinomas. Likewise, it has been reported that CD44v6 expression progressively increases following the normal mucosa-adenoma-carcinoma sequence (Heider et al. 1993; Kim et al. 1994; Neumayer et al. 1999). However, in the present study, membranous CD44v5 levels did not change significantly between tumors and non-neoplastic mucosal samples, which is in accordance with one of our preliminary reports using also immunoenzymatic assay (Llaneza et al. 2000). On the other hand, our results show that CD44v5 levels were significantly lower in tumors from proximal colon, for which we do not have a reasonable explanation at the present time.

In this study, both high CD44v5 and CD44v6 levels in tumors were significantly associated with a shorter relapse-free survival. In addition, CD44v6 levels correlated significantly with both relapse-free and overall survival in the multivariate analysis in our patients with resectable colorectal cancer. These findings are in accordance with previous experimental data supporting the association between CD44v and tumor progression. Accordingly, it has been reported that transfection of DNA (CD44v6) into a non-metastasizing pancreatic rat carcinoma cell line conferred it with metastasizing properties (Gunthert et al. 1991). Likewise, antibodies specific for this CD44 variant were capable of inhibiting the formation of secondary neoplastic foci when injected into tumor cells. On the other hand, there are other data supporting a wider role of CD44v in tumor progression. Thus, by analogy with other families of adhesion receptors, CD44 may also have signal transduction functions in tumor cells following receptor-mediated adhesion to extracellular matrix proteins, and activate pathways in response to binding discrete ligands (Koopman et al. 1990). Thus, it has been shown that CD44v6 in two different colon carcinoma cell lines could trigger distinct pathways leading to the development of chemotherapeutic resistance, suggesting that it may have important biological implications for the understanding of both drug resistance in tumors and the selective advantages conferred to cells expressing this receptor (Bates et al. 2001). In addition, considering that CD44 functions as a major receptor for hyaluronic acid, CD44 expression may allow tumor cells to adhere more firmly to hyaluronan, which is probably an essential stimulus in the migration process of tumor cells through the extracellular matrix (Rudzki and Jothy 1997). Accordingly, it has been recently reported that the collaboration between CD44v6 and ß-catenin in patients with T1 colorectal carcinoma may contribute to tumor aggressiveness through the formation of budding cells (Masaki et al. 2001). Tumor budding is a histological feature showing small nests of tumor cells with poor differentiation at the invasive margin of the tumor. Thus, this latter finding suggests that the expression of CD44v6 may promote the dissociation of tumor cells from the invasive margin and the invasion of scattered tumor cells into the stroma in colorectal carcinomas. Nevertheless, it has also been proven that distant metastasis show downregulation of the CD44v6 expression in comparison with the primary tumor (Finke et al. 1995; Nanashima et al. 2001), suggesting that the role of the various CD44v isoforms may differ along the diverse phases of tumor progression in colorectal cancer.

Despite all of these experimental data pointing to a role of CD44 variants in tumor progression, the clinical significance of their overexpression in colorectal carcinoma is currently a matter of ongoing debate (Bhatavdekar et al. 1998; Coppola et al. 1998; Finke et al. 1995; Koretz et al. 1995; Kuniyasu et al. 2001; Mulder et al. 1994; Nanashima et al. 2001; Ropponen et al. 1998; Wielenga et al. 2000a; Yamaguchi et al. 1996). Two previous immunohistochemical studies did not demonstrate any significant relationship between CD44v5 expression and prognosis in colorectal cancer patients (Gotley et al. 1996; Wielenga et al. 1998). In some immunohistochemical studies, high intratumoral CD44v6 levels were appreciably associated with a shorter overall patient survival (Mulder et al. 1994; Ropponen et al. 1998; Wielenga et al. 1998). However, other authors, also using immunohistochemical methods, have not found any significant association between the expression of CD44v6 and prognosis (Gotley et al. 1996; Jungling et al. 2002; Morrin and Delaney 2002). These discordant results may be due to different methodological aspects related to the staining techniques (Gilcrease et al. 1999). Therefore, we consider that the immunoenzymatic assay used in the present study may permit a more objective measurement of CD44v tumor levels than immunohistochemical studies, and may represent a useful alternative method for assessing CD44v status in colorectal cancer.

Overall, the results of the present work suggest that both membranous CD44v5 and CD44v6 levels in primary tumors, measured by immunoenzymatic assay, in combination with specific clinicopathological parameters, may contribute to a more precise prognostic estimation in patients with resectable colorectal cancer. Further investigations are necessary to assess the precise biological role of the CD44v isoforms in colorectal cancer, as well as to evaluate their possible value as novel therapeutic targets.

Footnotes

Supported by grants from ISCIII Red de Centros de Cancer RTICCC (C03/10) and Obra Social Cajastur

References

- Bates RC, Edwards NS, Burns GF, Fisher DE (2001) A CD44 survival pathway triggers chemoresistance via lyn kinase and phosphoinositide 3-kinase/Akt in colon carcinoma cells. Cancer Res 61:5275–5283 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatavdekar JM, Patel DD, Chikhlikar PR, Trivedi TI, Gosalia NM, Ghosh N, Shah NG, Vora HH, Suthar TP (1998) Overexpression of CD44: a useful independent predictor of prognosis in patients with colorectal carcinomas. Ann Surg Oncol 5:495–501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford MM (1976) A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem 72:248–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broders A (1925) The grading of carcinoma. Minn Med 8:726 [Google Scholar]

- Coppola D, Hyacinthe M, Fu L, Cantor AB, Karl R, Marcet J, Cooper DL, Nicosia SV, Cooper HS (1998) CD44V6 expression in human colorectal carcinoma. Hum Pathol 29:627–635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dukes C (1932) The classification of cancer of the rectum. J Pathol Bacteriol 35:323–332 [Google Scholar]

- Finke LH, Terpe HJ, Zorb C, Haensch W, Schlag PM (1995) Colorectal cancer prognosis and expression of exon-v6-containing CD44 proteins. Lancet 345:583 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilcrease MZ, Guzman-Paz M, Niehans G, Cherwitz D, McCarthy JB, Albores-Saavedra J (1999) Correlation of CD44S expression in renal clear cell carcinomas with subsequent tumor progression or recurrence. Cancer 86:2320–2326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotley DC, Fawcett J, Walsh MD, Reeder JA, Simmons DL, Antalis TM (1996) Alternatively spliced variants of the cell adhesion molecule CD44 and tumor progression in colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer 74:342–351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guler G, Sarac S, Uner A, Karabulut E, Ayhan A, Hiroshi O (2002) Prognostic value of CD44 variant 6 in laryngeal epidermoid carcinomas. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 128:393–397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunthert U, Hofmann M, Rudy W, Reber S, Zoller M, Haussmann I, Matzku S, Wenzel A, Ponta H, Herrlich P (1991) A new variant of glycoprotein CD44 confers metastatic potential to rat carcinoma cells. Cell 65:13–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedley DW, Shankey TV, Wheeless LL (1993) DNA cytometry consensus conference. Cytometry 14:471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heider KH, Hofmann M, Hors E, van den Berg F, Ponta H, Herrlich P, Pals ST (1993) A human homologue of the rat metastasis-associated variant of CD44 is expressed in colorectal carcinomas and adenomatous polyps. J Cell Biol 120:227–233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermaneck P, Sobin L (2002) UICC TNM classification of malignant tumors. Springer, Berlin Heidelberg New York

- Herrlich P, Zoller M, Pals ST, Ponta H (1993) CD44 splice variants: metastases meet lymphocytes. Immunol Today 14:395–399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jungling B, Menges M, Goebel R, Wittig BM, Weg-Remers S, Pistorius G, Schilling M, Bauer M, Konig J, Zeitz M et al (2002) Expression of CD44v6 has no prognostic value in patients with colorectal cancer. Z Gastroenterol 40:229–233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan E, Meier P (1958) Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc 53:457–481 [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann M, Heider KH, Sinn HP, von Minckwitz G, Ponta H, Herrlich P (1995) CD44 isoforms in prognosis of breast cancer. Lancet 346:502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H, Yang XL, Rosada C, Hamilton SR, August JT (1994) CD44 expression in colorectal adenomas is an early event occurring prior to K-ras and p53 gene mutation. Arch Biochem Biophys 310:504–507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koopman G, van Kooyk Y, de Graaff M, Meyer CJ, Figdor CG, Pals ST (1990) Triggering of the CD44 antigen on T lymphocytes promotes T cell adhesion through the LFA-1 pathway. J Immunol 145:3589–3593 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koretz K, Moller P, Lehnert T, Hinz U, Otto HF, Herfarth C (1995) Effect of CD44v6 on survival in colorectal carcinoma. Lancet 345:327–328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuniyasu H, Oue N, Tsutsumi M, Tahara E, Yasui W (2001) Heparan sulfate enhances invasion by human colon carcinoma cell lines through expression of CD44 variant exon 3. Clin Cancer Res 7:4067–4072 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llaneza A, Vizoso F, Rodriguez JC, Raigoso P, Garcia-Muniz JL, Allende MT, Garcia-Moran M (2000) Hyaluronic acid as prognostic marker in resectable colorectal cancer. Br J Surg 87:1690–1696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantel N, Myers M (1971) Problems of convergence of maximum likehood iterative procedures in multiparameter situations. J Am Stat Assoc 66:484–491 [Google Scholar]

- Masaki T, Goto A, Sugiyama M, Matsuoka H, Abe N, Sakamoto A, Atomi Y (2001) Possible contribution of CD44 variant 6 and nuclear beta-catenin expression to the formation of budding tumor cells in patients with T1 colorectal carcinoma. Cancer 92:2539–2546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer B, Jauch KW, Gunthert U, Figdor CG, Schildberg FW, Funke I, Johnson JP (1993) De-novo expression of CD44 and survival in gastric cancer. Lancet 342:1019–1022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrin M, Delaney PV (2002) CD44v6 is not relevant in colorectal tumor progression. Int J Colorectal Dis 17:30–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulder JW, Kruyt PM, Sewnath M, Oosting J, Seldenrijk CA, Weidema WF, Offerhaus GJ, Pals ST (1994) Colorectal cancer prognosis and expression of exon-v6-containing CD44 proteins. Lancet 344:1470–1472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nanashima A, Yamaguchi H, Sawai T, Yamaguchi E, Kidogawa H, Matsuo S, Yasutake T, Tsuji T, Jibiki M, Nakagoe T, et al (2001) Prognostic factors in hepatic metastases of colorectal carcinoma: immunohistochemical analysis of tumor biological factors. Dig Dis Sci 46:1623–1628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naot D, Sionov RV, Ish-Shalom D (1997) CD44: structure, function, and association with the malignant process. Adv Cancer Res 71:241–319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumayer R, Rosen HR, Reiner A, Sebesta C, Schmid A, Tuchler H, Schiessel R (1999) CD44 expression in benign and malignant colorectal polyps. Dis Colon Rectum 42:50–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ropponen KM, Eskelinen MJ, Lipponen PK, Alhava E, Kosma VM (1998) Expression of CD44 and variant proteins in human colorectal cancer and its relevance for prognosis. Scand J Gastroenterol 33:301–309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudzki Z, Jothy S (1997) CD44 and the adhesion of neoplastic cells. Mol Pathol 50:57–71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Screaton GR, Bell MV, Jackson DG, Cornelis FB, Gerth U, Bell JI (1992) Genomic structure of DNA encoding the lymphocyte homing receptor CD44 reveals at least 12 alternatively spliced exons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 89:12160–12164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sneath RJ, Mangham DC (1998) The normal structure and function of CD44 and its role in neoplasia. Mol Pathol 51:191–200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stauder R, Eisterer W, Thaler J, Gunthert U (1995) CD44 variant isoforms in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: a new independent prognostic factor. Blood 85:2885–2899 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wielenga VJ, Heider KH, Offerhaus GJ, Adolf GR, van den Berg FM, Ponta H, Herrlich P, Pals ST (1993) Expression of CD44 variant proteins in human colorectal cancer is related to tumor progression. Cancer Res 53:4754–4756 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wielenga VJ, van der Voort R, Mulder JW, Kruyt PM, Weidema WF, Oosting J, Seldenrijk CA, van Krimpen C, Offerhaus GJ, Pals ST (1998) CD44 splice variants as prognostic markers in colorectal cancer. Scand J Gastroenterol 33:82–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wielenga VJ, van der Neut R, Offerhaus GJ, Pals ST (2000a) CD44 glycoproteins in colorectal cancer: expression, function, and prognostic value. Adv Cancer Res 77:169–187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wielenga VJ, van der Voort R, Taher TE, Smit L, Beuling EA, van Krimpen C, Spaargaren M, Pals ST (2000b) Expression of c-Met and heparan-sulfate proteoglycan forms of CD44 in colorectal cancer. Am J Pathol 157:1563–1573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi A, Urano T, Goi T, Saito M, Takeuchi K, Hirose K, Nakagawara G, Shiku H, Furukawa K (1996) Expression of a CD44 variant containing exons 8 to 10 is a useful independent factor for the prediction of prognosis in colorectal cancer patients. J Clin Oncol 14:1122–1127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi A, Goi T, Yu J, Hirono Y, Ishida M, Iida A, Kimura T, Takeuchi K, Katayama K, Hirose K (2002) Expression of CD44v6 in advanced gastric cancer and its relationship to hematogenous metastasis and long-term prognosis. J Surg Oncol 79:230–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]