Abstract

Aspergillosis is an uncommon fungal infection caused by Aspergillus species, predominantly affecting immunocompromised individuals. While pulmonary involvement is common, extrapulmonary manifestations such as osteomyelitis are uncommon. Aspergillus osteomyelitis of the mandible is an exceptionally rare and life-threatening condition, posing significant diagnostic and therapeutic challenges. We present the case of a 13-year-old immunocompromised patient diagnosed with this condition. The patient presented with persistent jaw pain, swelling, and radiographic evidence of extensive bone destruction. Diagnosis was confirmed through fungal cultures and histopathological examination, which identified Aspergillus species. The patient underwent surgical debridement and prolonged antifungal therapy, leading to clinical improvement. Aspergillus osteomyelitis of the mandible is exceedingly rare, with only a few cases reported in the literature. Early diagnosis is crucial to prevent further bone destruction and associated complications. This case underscores the importance of considering fungal infections in the differential diagnosis of osteomyelitis, particularly in at-risk populations. It also emphasizes the potential role of antifungal prophylaxis in reducing the severity of invasive fungal infections when they occur. Managing this condition presents significant challenges, including the need for aggressive antifungal therapy and the risk of recurrence.

Keywords: Aspergillus osteomyelitis, mandible, immunocompromised, fungal infection, bone destruction, treatment, case report

Introduction

Aspergillosis is an uncommon opportunistic fungal infection caused by species of the Aspergillus genus, primarily affecting immunocompromised individuals. It can cause significant soft tissue and bone destruction and is associated with high mortality, particularly in its invasive form, which has a crude mortality rate of 85.2%.1,2 Although typically affecting the respiratory tract, causing conditions such as rhinosinusitis and pulmonary infections, extrapulmonary manifestations such as invasive sinusitis or allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis are unfrequent. 3 Bone and joint infections has been documented as well but are less common compared to other forms with only 18% Aspergillus osteomyelitis cases involving the jaw, skull base, or paranasal sinuses. 4 The oral cavity is an exceptional site of Aspergillus osteomyelitis especially in pediatric patients, resulting from arterial invasion by fungal hyphae, leading to thrombosis and compromised blood supply to the affected bone. It primarily affects immunocompromised patients, particularly those with underlying hematological malignancies.4 -7

This report aims to present a rare case of mandibular Aspergillus osteomyelitis in a 13-year-old immunocompromised patient, highlighting the diagnostic and therapeutic challenges encountered in this challenging clinical scenario, and emphasizing the importance of a multidisciplinary approach to ensure optimal patient outcomes, supported by a review of the literature.

Case Presentation

A 13-year-old male with a history of juvenile idiopathic arthritis complicated by B-cell lymphoma was referred to the Hematology Department at Farhat Hached University Hospital for management of his malignancy. The lymphoma was staged as I according to Ann Arbor classification, with no evidence of medullary or meningeal infiltration. The patient underwent chemotherapy according to the EORTC Average Risk 2 protocol. Induction therapy, initiated 3 years prior, was complicated by probable invasive pulmonary aspergillosis, as evidenced by positive aspergillus antigenemia and chest CT findings consistent with pulmonary aspergillosis. Voriconazole (4 mg/kg twice daily) was initiated as antifungal therapy, leading to complete remission. However, during maintenance therapy, the patient experienced a bone marrow relapse characterized by 70% medullary infiltration of blasts with a phenotypic profile consistent with CD10+ B-lymphoid acute leukemia. Salvage therapy with FLAG-Daunorubicin was administered.

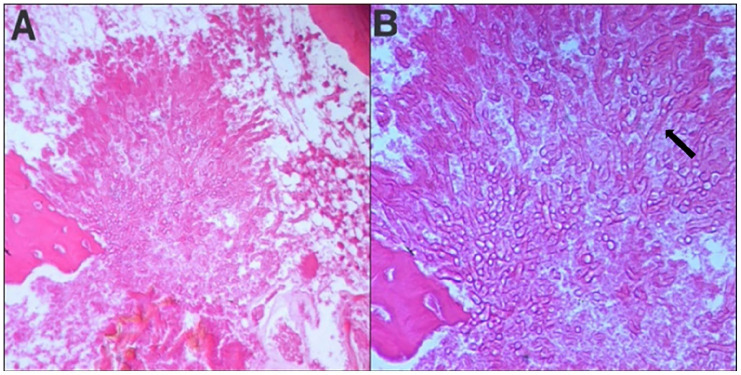

Three weeks following the salvage therapy, the patient developed febrile neutropenia accompanied by a painful, inflammatory swelling of the left mandible. This finding was further characterized by CT scan imaging (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Axial post-contrast CT (soft tissue window) revealed marked soft tissue thickening and swelling in the left mandibular region without evidence of fluid collection. Inflammatory changes extend into the adjacent subcutaneous tissues, with associated myositis of the left masseter and medial pterygoid muscles (Red asterisks). Notably, mild asymmetry and compression of the aeropharyngeal crossroads suggest a mass effect due to the inflammatory process (Yellow asterisk). These findings are consistent with left submandibular bacterial cellulitis with deep space involvement.

Due to severe neutropenia, a dental consultation was initially delayed. Empirical treatment with broad-spectrum antibiotics combined with voriconazole was initiated. Despite this, there was no significant improvement in the patient’s condition. Although the swelling partially regressed with hematologic recovery, mild cheek swelling persisted. Once the patient’s neutrophil count recovered, he was referred to the Dental Medicine Department for further evaluation of the persistent facial asymmetry. The intraoral examination revealed:

- A grayish ischemic appearance of the vestibular mucosa adjacent to tooth 37, with bone exposure in the cervical and septal regions of teeth 36 and 37.

- No evidence of active decay was found in teeth 36 and 37, and both responded positively to pulp vitality testing.

- Painful vestibular palpation around tooth 37, without any associated swelling.

- Probing around tooth 37 revealed a loose, non-detachable vestibular sequestrum (a piece of necrotic bone that has become separated from the surrounding alveolar bone) located in the vestibular region (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Intraoral examination revealing a loose, non-detachable bone sequestrum, approximately 1.5 cm in diameter, located in the vestibular region of the left mandibular body. The sequestrum exhibited a dark, necrotic appearance and was minimally mobile within the surrounding soft tissues suggesting an ongoing inflammatory process and the need for further intervention (White circle).

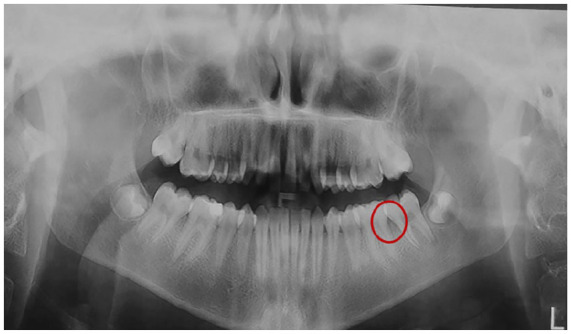

Radiographic Findings

- Retroalveolar radiograph showed widening of the periodontal ligament space around tooth 37.

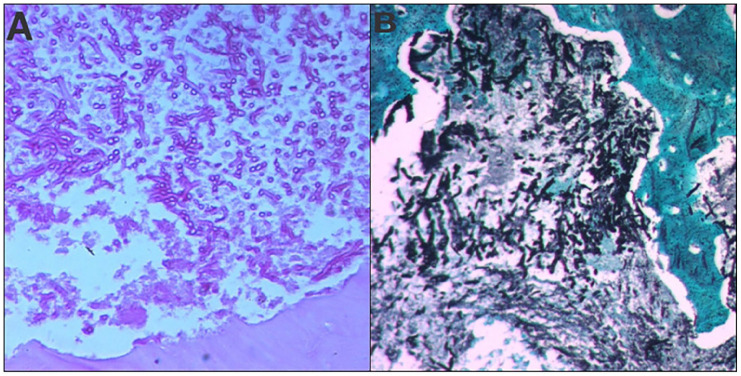

- Orthopantomogram (OPG) revealed interproximal bone loss between teeth 36 and 37 (Figure 3).

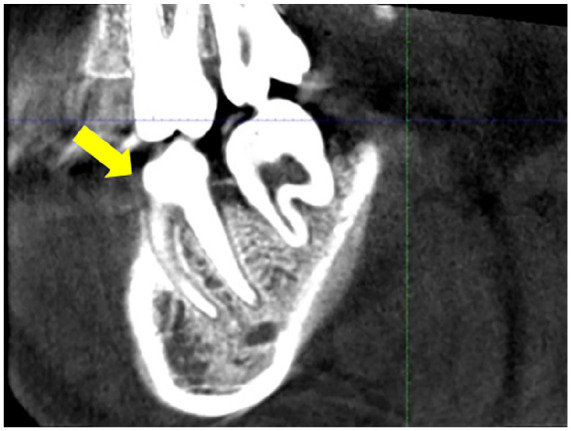

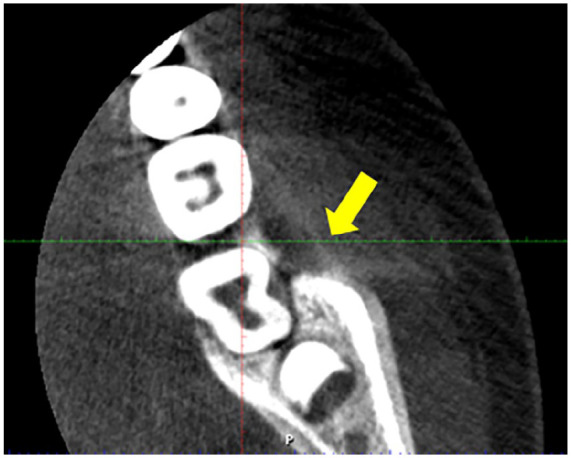

- Cone Beam Computed Tomography (CBCT): Sagittal view demonstrated cortical bone destruction around teeth 36 and 37, characterized by thinning of the buccal and lingual cortical plates with associated radiolucencies and loss of lamina dura. Furcation involvement was observed in tooth 36 (Figure 4). Axial view revealed a vestibular bone sequestrum around tooth 37 along with widening of the periodontal ligament space (Figure 5).

Figure 3.

Orthopantomogram (OPG) revealed interproximal bone loss between teeth 36 and 37 (Red circle).

Figure 4.

A sagittal CBCT image demonstrated cortical bone destruction around teeth 36 and 37, characterized by loss of lamina dura of the tooth 36 with associated radiolucencies. Furcation involvement was observed in tooth 36 (Yellow arrow).

Figure 5.

An axial CBCT image revealed cortical bone destruction around teeth 36 and 37, characterized by the presence of radiolucencies, and thin buccal sequestrum (Yellow arrow).

Based on these findings, the initial diagnostic hypotheses included:

• Neutropenic ulceration with subsequent bone exposure due to a prior episode of severe neutropenia.

• Non-specific bacterial osteomyelitis.

• Specific osteomyelitis: Potentially caused by a fungal superinfection, such as aspergillosis or mucormycosis, given the patient’s underlying immunosuppression.

Surgical Intervention

The initial surgical intervention involved meticulous debridement of the infected site, including removal of the sequestrum and surrounding inflamed granulation tissue. The surgical field revealed clean, well-defined bone margins, indicating complete removal of the necrotic debris. The resected sequestrum, measuring approximately 1.5 cm, exhibited a dark, necrotic appearance (Figures 6 and 7).

Figure 6.

Intraoperative clinical view demonstrating the surgical site following meticulous debridement. The surgical field reveals clean, well-defined bone margins after complete removal of the sequestrum and the surrounding inflamed granulation tissue. The extent of the bony defect and the thoroughness of the surgical intervention are clearly evident.

Figure 7.

Surgical removal of the movable sequestrum, measuring approximately 1.5 cm. The sequestrum exhibited a yellowish, necrotic appearance.

Postoperative Management

The patient was prescribed continued antibiotic therapy, analgesics, and chlorhexidine mouth rinse.

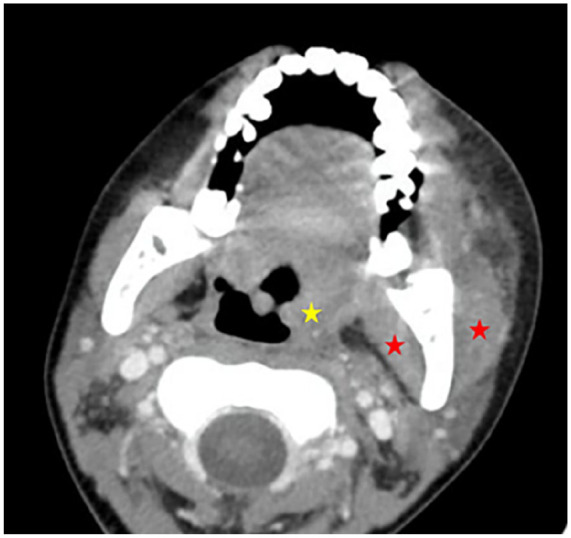

Histopathological examination of the resected tissue revealed chronic inflammatory changes, characterized by a polymorphic infiltrate and vascular neoformation. Mycelial filaments of Aspergillus were identified exclusively within the bone sequestrum, confirming the diagnosis of chronic Aspergillus osteomyelitis (Figures 8 and 9).

Figure 8.

Histopathological examination of tissue sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin revealed the presence of septate, branching hyphae consistent with Aspergillus species ((A) ×200, (B) ×400). (Black arrow).

Figure 9.

Histopathological examination of tissue sections revealed the presence of septate, branching hyphae consistent with Aspergillus species. Special stains, including Periodic Acid-Schiff (PAS) and Grocott’s methenamine silver (GMS) stains, confirmed the fungal elements ((A) PAS×200, (B) GMS×400).

The antifungal regimen was continued alongside antibiotic therapy following the diagnosis of Aspergillus osteomyelitis.

Mucosal healing was satisfactory 15 days postoperatively, demonstrating complete wound closure with minimal signs of inflammation and no evidence of dehiscence or complications that could compromise oral function (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Mucosal healing was satisfactory 15 days postoperatively, demonstrating complete wound closure with minimal signs of inflammation and no evidence of dehiscence or complications that could compromise oral function.

Discussion

Aspergillosis covers a spectrum of diseases caused by Aspergillus species, ranging from benign colonization to life-threatening invasive infections.6,8

Invasive aspergillosis predominantly affects immunocompromised individuals, with significant mortality rates, ranging from 50% to 85%.1,2 While pulmonary involvement is most common, extrapulmonary manifestations, including osteomyelitis, can occur.4,5,9

Pathogenesis and Risk Factors

Aspergillus osteomyelitis can arise through various mechanisms, including hematogenous spread from a pulmonary source, direct invasion from adjacent infected tissues, or inoculation during surgical procedures or trauma.4,7,10,11

Immunocompromised individuals, such as patients with hematological malignancies like our case subject, are at significantly increased risk of severe infections due to impaired immune defenses. Factors such as neutropenia, prolonged corticosteroid use, immunosuppressive therapy, and underlying medical conditions can further increase susceptibility to fungal infections.4 -9,12 -15 Osteomyelitis can affect any bone; however, certain anatomical regions, especially the jawbones, are more susceptible due to specific characteristics. The presence of teeth, periodontal disease, and the proximity of the maxillary sinus create a favorable environment for fungal colonization, predisposing individuals to osteomyelitis.8,10,12,13 The mandible, being more susceptible due to its reduced blood supply and increased bone density, is more frequently affected than the maxilla, which benefits from greater vascularity.6,10,16,17

Clinical Presentation

Clinically, aspergillus osteomyelitis of the jaw can manifest with gingival necrosis, swelling, pain, fistula formation, and bone sequestration.5 -7,10 Our patient presented with severe, throbbing pain and significant swelling in the left mandible. Clinical examination revealed a palpable, firm mass and a bony sequestrum approximately 1.5 cm in diameter located on the buccal aspect of the mandible, consistent with these clinical features. Oral aspergillosis progresses through 2 stages: an initial stage with violaceous gingival areas evolving into necrotic ulcers (easily mistaken for neutropenic ulcers) and a late stage characterized by extensive ulcers, alveolar bone destruction, and tissue perforation.5,6,8,9,14 Systemic involvement, such as fever or pulmonary aspergillosis, can occur.5 -7,10 Our patient exhibited both fever and a history of pulmonary aspergillosis, further supporting the diagnosis of disseminated disease. Early clinical signs, including the characteristic yellow or gray gingival discoloration in immunocompromised patients, combined with a positive response to antifungal therapy, can aid in diagnosis.5,6,8,9,12,18

This was evident in our patient, who presented with a grayish ischemic appearance of the mucosa, a finding consistent with reports from Chugh et al. 17 These clinical features, while suggestive of osteomyelitis, can also be seen in other conditions, such as bacterial osteomyelitis, malignancy, and necrotizing periodontitis. Therefore, a high index of suspicion and thorough diagnostic workup are essential for accurate diagnosis.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of Aspergillus osteomyelitis can be challenging due to its nonspecific clinical presentation and the overlap of symptoms with other conditions, including bacterial osteomyelitis, mucormycosis, tuberculosis, and malignancies.5,6,8 In our patient, the initial presentation with swelling, pain, and fever raised the suspicion of bacterial cellulitis. However, the presence of a bony sequestrum on clinical examination and the patient’s history of immunosuppression prompted further investigation. Radiographic imaging played a crucial role in diagnosis. CBCT revealed extensive bone destruction in the left mandible with a well-defined area of radiolucency and a bony sequestrum, findings highly suggestive of osteomyelitis. Histologic examination of biopsy specimens obtained from the area of most active disease is essential for definitive diagnosis. Microscopic examination revealed the presence of septate, branching hyphae consistent with Aspergillus species, confirming the diagnosis of Aspergillus osteomyelitis.

Non-invasive methods, such as the detection of circulating galactomannan, can support the diagnostic process. Furthermore, biopsy and tissue culture are essential for confirming the infection and guiding appropriate therapy.5,6,8,9,12,18 In our case, the diagnosis was primarily based on histopathological findings. This case highlights the importance of a high index of suspicion and a comprehensive diagnostic workup, including imaging studies and histopathological examination, for the accurate diagnosis of Aspergillus osteomyelitis in immunocompromised patients. Gabrielli et al reported that only 18% of aspergillus osteomyelitis cases involved the maxillofacial region, highlighting the unusual nature of such infections in the jaws. 4 Only a few cases of mandibular aspergillosis have been documented, primarily in immunocompromised patients (Table 1)

Table 1.

Review of mandibular aspergillus osteomyelitis reported in the literature.

| Author | Year | Sex | Age | Risk factors | Oral manifestation | Systemic manifestation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hovi et al 11 | 1996 | F | 5 | Leukemia | Gingival necrosis and swelling | Fever |

| Filippi et al 12 | 1997 | M | 36 | Leukemia | Gingival necrosis, bone sequestration | Pulmonary aspergillosis |

| Sandhu and Kaur 13 | 2003 | F | 35 | None | Gingival necrosis | Pulmonary aspergillosis |

| Lador et al 16 | 2006 | F | 42 | Leukemia | Gingival and alveolar mucosa necrosis | Fever |

| Chugh et al 17 | 2022 | M | 64 | Post-covid 19 | Alveolar mucosa and bone necrosis | None |

| Faustino et al 6 | 2022 | F | 57 | None | Fistula, recurrent swelling, pain, and purulent drainage | None |

| Current | 2024 | M | 13 | Leukemia | Pain, swelling, gingival and alveolar mucosa necrosis, bone sequestration | History of pulmonary aspergillosis |

Treatment and Management

The treatment of oral invasive aspergillosis requires a multidisciplinary approach necessitating hospitalization. Successful outcomes depend on a comprehensive assessment of the patient’s overall medical and hematological status, including potential systemic involvement, which are critical determinants of treatment success.6,9,12 Aspergillus osteomyelitis requires a combination of antifungal therapy and surgical intervention.

- Antifungal Therapy: Empirical antifungal therapy, initiated based on clinical suspicion even before diagnostic confirmation, and pre-emptive antifungal therapy, delayed until diagnostic confirmation, are both considered. While both approaches have comparable safety profiles, the quality of supporting evidence is limited.19,20

Amphotericin B has been traditionally used, but azoles such as itraconazole and voriconazole, are now preferred as recommended by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA). Studies have demonstrated that voriconazole offers superior efficacy compared to amphotericin B, with improved survival rates and fewer side effects.4,5,9,12

- Surgical Intervention: Surgical debridement of necrotic tissues is necessary to complement systemic antifungal therapy. However, it should be approached cautiously in neutropenic patients due to the increased risk of secondary infections. Early diagnosis is essential for improving outcomes due to the high morbidity associated with this infection and the patient’s underlying medical and hematological status, which significantly impacts treatment success.5,6,8,10,15

- Prophylaxis: Antifungal prophylaxis is crucial for high-risk patients to prevent invasive fungal infections. However, it must be carefully tailored to individual risk factors, such as the degree of immunosuppression and exposure to fungal spores. The widespread use of antifungal prophylaxis may alter the spectrum of causative fungi, potentially promoting the emergence of resistant less common species.21,22 Isavuconazole, with its broad-spectrum activity and favorable safety profile, has been proposed as a promising option for managing these infections while minimizing toxicity and resistance. However, its availability may be restricted in certain regions due to cost, presenting challenges in managing fungal infections in resource-limited settings. 23 Maintaining meticulous oral hygiene in immunocompromised patients is essential in preventing fungal infections, especially in immunocompromised individuals. In our patient, the relatively benign course of the infection can be attributed to initial antifungal prophylaxis with voriconazole (4 mg/kg twice daily). This highlights the effectiveness of this preventive protocol against invasive aspergillosis in immunocompromised patients with bone marrow aplasia. While infection may still occur, as demonstrated in this case, it appears in a less severe form. In resistant cases, species identification is essential for tailoring specific drug therapy.5,6,8,9,12,18

Outcomes: Early diagnosis and the prompt initiation of aggressive antifungal therapy and surgical debridement are crucial for favorable outcomes. This approach has demonstrated greater efficacy in eradicating infection and is associated with a lower relapse rate, aligning with current clinical guidelines and corroborating the findings of this case report. Patient outcomes are significantly influenced by underlying conditions such as immunosuppression and the extent of the infection.15,24 -27 In this specific case, the combination of antifungal therapy and aggressive surgical debridement resulted in favorable outcomes with complete clinical improvement without any clinical signs of infection.

Limitations

This case report describes the management of a single patient and may not be generalizable to all cases of Aspergillus osteomyelitis in patients with weakened immune systems. Further research is needed to better understand the epidemiology, pathogenesis, role of antifungal prophylaxis, and optimal management strategies for this challenging infection.

Conclusion

This case highlights the challenges of managing oral complications in severely immunocompromised patients, particularly those with hematological malignancies.

Notably, these complications developed despite prophylactic voriconazole therapy, underscoring the clinical complexity and calling into question the effectiveness of current preventive strategies. To our knowledge, this is one of the first reports detailing such a presentation, emphasizing the need for heightened clinical vigilance and further investigation into alternative prophylactic or therapeutic approaches for high-risk pediatric populations. The successful management of this case underscores the importance of a multidisciplinary approach, the use of antifungal prophylaxis, early diagnosis, and aggressive treatment, including a combination of antifungal therapy and surgical intervention.

Acknowledgments

Authors thank the LR12SP10 Functional and Aesthetic Rehabilitation of the Jaws Laboratory for their support.

Footnotes

ORCID iDs: Ikram Attouchi  https://orcid.org/0009-0007-8329-8445

https://orcid.org/0009-0007-8329-8445

Ghada Bouslama  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0292-5862

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0292-5862

Nour Sayda Ben Messaoud  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3226-0320

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3226-0320

Atig Amira  https://orcid.org/0009-0007-3259-1377

https://orcid.org/0009-0007-3259-1377

Souha Ben Youssef  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6568-9425

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6568-9425

Author Contributions: First author: Conceptualization, Writing—Original Draft Preparation.

Authors 2 and 3: Methodology, Writing—Review & Editing.

Authors 4, 5 and 6: Investigation, Writing—Review & Editing.

Authors 7 and 8: Formal analysis, Writing—Review & Editing.

Author 9: Investigation, Writing—Original Draft Preparation.

Consent to Participate: Written Informed Consent to participate was obtained from the legally authorized representative of the minor subject.

Consent for Publication: Written Informed Consent was obtained from the legally authorized representative of the minor subject for the publication of the case report.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. Denning DW. Global incidence and mortality of severe fungal disease. Lancet Infect Dis. 2024;24(7):e428-e438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lowes D, Al-Shair K, Newton PJ, et al. Predictors of mortality in chronic pulmonary aspergillosis. Eur Respir J. 2017; 49(2):1601062. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01062-2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. López-Cortés LE, Garcia-Vidal C, Ayats J, et al. [Invasive aspergillosis with extrapulmonary involvement: pathogenesis, clinical characteristics and prognosis]. Rev Iberoam Micol. 2012;29(3):139-143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gabrielli E, Fothergill AW, Brescini L, et al. Osteomyelitis caused by Aspergillus species: a review of 310 reported cases. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20(6):559-565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cho H, Lee KH, Colquhoun AN, Evans SA. Invasive oral aspergillosis in a patient with acute myeloid leukaemia. Aust Dent J. 2010;55(2):214-218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Faustino I, Ramos J, Mariz B, et al. A rare case of mandibular Aspergillus osteomyelitis in an immunocompetent patient. Dent J. 2022;10(11):213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Suresh A, Joshi A, Desai AK, et al. Covid-19-associated fungal osteomyelitis of jaws and sinuses: an experience-driven management protocol. Med Mycol. 2022;60(2):myab082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Myoken Y, Sugata T, Kyo TI, Fujihara M. Pathologic features of invasive oral aspergillosis in patients with hematologic malignancies. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1996;54(3):263-270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Karabulut AB, Kabakas F, Berköz Karakas Z, Kesim SN. Hard palate perforation due to invasive aspergillosis in a patient with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2005;69(10):1395-1398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Vardas E, Adamo D, Canfora F, et al. Impact of COVID-19 disease on the development of osteomyelitis of jaws: a systematic review. J Clin Med. 2024;13(15):4290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hovi L, Saarinen UM, Donner U, Lindqvist C. Opportunistic osteomyelitis in the jaws of children on immunosuppressive chemotherapy. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 1996;18(1):90-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Filippi A, Dreyer T, Bohle R, Pohl Y, Rosseau S. Sequestration of the alveolar bone by invasive aspergillosis in acute myeloid leukemia. J Oral Pathol Med. 1997;26(9):437-440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sandhu S, Kaur T. Aspergillosis: a rare case of secondary delayed mandibular involvement. Quintessence Int Berl Ger 1985. 2003;34(2):139-142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Patil PM, Bhadani P. Extensive maxillary necrosis following tooth extraction. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011;69(9):2387-2391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Datarkar A, Gadve V, Dhoble A, et al. Osteomyelitis of jaw bone due to aspergillosis in post-COVID-19 patients: an observational study. J Maxillofac Oral Surg. 2024;23(2): 308-315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lador N, Polacheck I, Gural A, Sanatski E, Garfunkel A. A trifungal infection of the mandible: case report and literature review. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2006;101(4):451-456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chugh A, Pandey AK, Goyal A, et al. Atypical presentations of fungal osteomyelitis during post COVID-19 outbreak – case series. J Oral Maxillofac Surg Med Pathol. 2022;34(5): 622-627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hodgson TA, Rachanis CC. Oral fungal and bacterial infections in HIV-infected individuals: an overview in Africa. Oral Dis. 2002;8(s2):80-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Uneno Y, Imura H, Makuuchi Y, Tochitani K, Watanabe N. Pre-emptive antifungal therapy versus empirical antifungal therapy for febrile neutropenia in people with cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2022;2022(11):CD013604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Maertens J, Lodewyck T, Donnelly JP, et al. Empiric vs preemptive antifungal strategy in high-risk neutropenic patients on fluconazole prophylaxis: a randomized trial of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer. Clin Infect Dis. 2023;76(4):674-682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wahab A, Sanborn D, Vergidis P, et al. Diagnosis and prevention of invasive fungal infections in the immunocompromised host. Chest. 2024;167(2):374-386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Yeoh DK, Haeusler GM, Slavin MA, Kotecha RS. Challenges and considerations for antifungal prophylaxis in children with acute myeloid leukemia. Expert Rev Hematol. 2024; 17(10):679-686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Thompson GR, Chen SCA, Alfouzan WA, et al. A global perspective of the changing epidemiology of invasive fungal disease and real-world experience with the use of isavuconazole. Med Mycol. 2024;62(9):myae083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Koehler P, Tacke D, Cornely OA. Aspergillosis of bones and joints – a review from 2002 until today. Mycoses. 2014; 57(6):323-335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tsantes AG, Papadopoulos DV, Markou E, et al. Aspergillus spp. Osteoarticular infections: an updated systematic review on the diagnosis, treatment and outcomes of 186 confirmed cases. Med Mycol. 2022;60(8):myac052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Neofytos D, Horn D, Anaissie E, et al. Epidemiology and outcome of invasive fungal infection in adult hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients: analysis of Multicenter Prospective Antifungal Therapy (PATH) Alliance Registry. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48(3):265-273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gamaletsou MN, Rammaert B, Bueno MA, et al. Aspergillus osteomyelitis: epidemiology, clinical manifestations, management, and outcome. J Infect. 2014;68(5):478-493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]