Abstract

To elucidate the mechanism underlying corneal scarring, a murine model of corneal scarring was subjected to transcriptomic and proteomic analyses to explore changes in mRNA and protein levels during scar formation. A surgical model of stromal injury was established, and corneal tissue was harvested 3 weeks post-wounding and subjected to RNA sequencing and tandem mass tag proteomics. A total of 420 differentially expressed genes and 463 differentially expressed proteins were detected, of which 54 were commonly altered. Integrated Gene Ontology and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes analyses revealed the predominant involvement of the regulation of actin cytoskeleton organization, cell metabolism, and regulation of inflammatory responses in the scarring process. To further explore the identified gene and protein interactions, we constructed a protein–protein interaction network that highlighted four keratin (Krt) genes (Krt13, Krt14, Krt17, and Krt19) as potential contributors to corneal scarring. The expression levels of these four keratins increased significantly in scarred corneas, which was validated via immunostaining. In vitro experiments revealed the upregulation of fibrosis markers after the overexpression of Krt13 in corneal epithelial cells and stromal keratocytes. Altogether, this study provides insights into gene and protein expression profiles that contribute to the development of corneal scarring, which could serve as a basis for developing targeted therapeutics and clarifying its molecular mechanisms.

Keywords: Corneal scarring, Transcriptomics, Proteomics, Keratin

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

The cornea is an integral component of the refractive surfaces in the eye, accounting for approximately 75 % of the total refractive capacity for retinal imaging. It also serves as a critical protective barrier, shielding the inner ocular tissue from external damage. The corneal stroma, which is primarily composed of quiescent keratocytes and uniformly arrayed collagen fibers, plays a crucial role in maintaining corneal transparency for effective light transmission and optimal visual acuity. Severe disturbance to the normal structural integrity of the corneal stroma can result in disruption of the characteristic collagen organization, which may lead to corneal opacity [1].

Following ocular trauma or infection, a complex corneal stromal regeneration process is initiated by several corneal epithelium-derived cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors such as interleukin-1α (IL-1α), transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1) and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) [1], [2], [3]. The mechanism involves the transformation of quiescent keratocytes into activated fibroblasts or myofibroblasts, cell migration to the wound site, and remodeling of the extracellular matrix (ECM) for tissue regeneration [4], [5]. The evolution of the healing process is highly associated with the extent of the initial injury, and an overproduction of ECM components may accelerate the development of fibrosis, thereby resulting in corneal scarring and irreversible visual impairment.

Currently, the primary treatment strategy for corneal scarring is corneal transplantation. However, the availability of donor corneas is limited, and the rejection rate can be high [6]. Furthermore, clinical alternatives such as the topical application of mitomycin C or steroids, which are regularly used to prevent the development of postoperative haze after photorefractive keratectomy, may have long-term safety issues (e.g., corneal endothelial damage, increased risk of glaucoma and cataract) [7], [8]. Therefore, gaining an in-depth understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying corneal scar formation would be crucial for the development of innovative, safe, and efficient targeted therapeutic interventions for corneal scarring.

Keratins (Krt) are a family of fibrous proteins abundant in cysteine and primarily localized in the epithelium, serving as a structural component of intermediate filaments (IFs) [9]. Keratin IFs form a three-dimensional intracellular network that considerably affects the shape and biophysical properties of the cell. These filaments provide cells with mechanical stability, enabling them to resist deformation and maintain their structural integrity [10]. Keratins are vital for preserving the functional and structural integrity of the cornea, particularly with regard to maintaining the integrity of the corneal epithelium. Genetic alterations in Krt3 and Krt12 are considered a potential cause of Meesmann’s corneal dystrophy, an autosomal dominant disease that leads to degeneration of the anterior corneal epithelium [11]. Recent studies have indicated the potential utility of keratin-based films and scaffolds in ocular surface reconstruction, demonstrating improved proliferation rates of fibroblasts and excellent corneal biocompatibility within the corneal stroma [12], [13]. Therefore, a comprehensive understanding of the role of keratins in the cornea is imperative to clarify the mechanisms underlying corneal pathologies and wound healing processes.

Several studies have used transcriptomic [14], [15] or proteomic [16] techniques to investigate the mechanism of corneal scar formation. Nevertheless, the findings generated from a single omics approach can be limited due to inconsistencies between gene and protein levels [17]. Integration of transcriptome and proteome data has proved advantageous, providing a systematic mapping of the gene-protein expression, uncovering the transcriptional–translational cascade during the biological process. In the present study, we combined proteome and transcriptome analyses to explore the molecular mechanisms underlying corneal scarring. Our results provide the first proteomic and transcriptomic overview of corneal stroma wound healing, revealing its complex interplay after pathological stimuli.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Murine model of corneal scarring

All experimental procedures were approved by the Ethics Committee of Shanghai Ninth People’s Hospital (SH9H-2024-A1387–1) and conducted in strict adherence to the ARVO Experimental Animal Ethical Guidelines for Ophthalmic Use. C57BL/6 J mice aged 8 weeks were used to prepare a surgical model of stromal injury as described previously [18], [19], [20], [21]. The right eyes of the mice were subjected to injury. To standardize stromal injuries, all surgical procedures were performed by the same trained ophthalmologist (T.Z.). After anesthesia, mice were treated with 0.4 % oxybuprocaine hydrochloride eye drops (Benoxil, Santen Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd) for topical corneal anesthesia. A 1.5-mm-diameter trephine was applied to the center of the cornea and gently rotated twice to penetrate the stroma and demarcate an area. The corneal epithelium was subsequently debrided using AlgerBrush II (The Alger Company, Lago Vista, TX), and a thin segment (20–30 µm depth) of the anterior stroma was excised using a surgical blade. The entire procedure was conducted under a microscope. Immediately after the injury, the wounded eye was treated with antibiotic tobramycin ointment (Tobrex, Norvatis, East Hanover, New Jersey) twice daily for 2 days to prevent infection.

2.2. Ocular measurements

The corneal scarring was evaluated 3 weeks post-wounding. A slit-lamp microscope coupled with a digital camera (SL-D7; Topcon Inc., Tokyo, Japan) was used for image acquisition to observe the clarity of corneas. The severity of corneal opacity was evaluated based on a scale ranging from 0 to 4, where 0 indicated high clarity, 1 indicated slight blurriness with both the iris and pupils easily distinguishable, 2 represented slight opacity that permitted the detection of the iris and pupils, 3 indicated severe opacity with the iris and pupils scarcely visible, and 4 represented complete opacity with no visibility of the iris and/or pupils [22].

Anterior segment optical coherence tomography (ASOCT; Heidelberg Engineering, Germany) was used to visualize corneal layers and compare central corneal thickness (CCT) and irregularity after injury. The thickness in the central area of each cornea was then measured and subsequently analyzed. To minimize potential systemic errors of ASOCT to distort anatomic structures, we measured vertical and horizontal CCT and calculated the average central thickness from these paired measurements.

2.3. RNA extraction and sequencing

RNA extraction and sequencing were performed by Shanghai Applied Protein Technology, China. Individual corneas (n = 6 biological replicates per group) were processed separately. Total RNA was isolated from corneal tissues using TRIzol® reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and detected using NanoDrop ND-2000 (Thermo Scientific, CA, USA). The RNA integrity number (RIN) was measured using Agilent Bioanalyzer 4150 (Agilent Technologies, CA, USA). RIN ≥ 8.0 indicates high-quality intact RNA, and samples below this threshold were excluded. Paired-end libraries were constructed using ABclonal mRNA-seq Lib Prep Kit (ABclonal, China); this process involved mRNA purification, fragmentation, complementary DNA (cDNA) synthesis, adapter ligation, polymerase chain reaction (PCR), and evaluation of library quality. Next, the prepared libraries were sequenced using Illumina Novaseq 6000, generating 150-bp paired-end reads. Preprocessing procedures including the removal of adapter sequences and filtration of low-quality reads (the number of lines with a string quality value less than or equal to 25 accounts for more than 60 % of the entire reading), were designed to obtain data suitable for subsequent analytical steps.

2.4. Tandem mass tag (TMT) labeling and liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (LC–MS/MS) analysis

Proteomics analysis was conducted by Shanghai Applied Protein Technology, China. Individual corneas (n = 3 biological replicates per group) were processed separately. Proteins were extracted from lysed corneal tissues 3 weeks post-wounding, and sample quantification was performed using BCA Protein Assay Kit (Bio-Rad, USA). After protein digestion via trypsin, the resultant peptide extracts from each sample were desalted and concentrated. Next, the peptides were resuspended in 40 µL of 0.1 % (v/v) formic acid solution. TMT reagent (Thermo Scientific, CA, USA) was used to label the prepared peptide mixture obtained from each sample. After mixing and fractionation of the labeled peptides using High pH Reversed-Phase Peptide Fractionation Kit (Thermo Scientific, CA, USA), LC–MS/MS analysis was performed using a Q Exactive mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific, CA, USA) equipped with Easy nLC (Proxeon Biosystems). To mitigate potential noise readings during data acquisition and analysis, strict quality control measures were applied to remove low-abundance peptides and proteins with insufficient signal-to-noise ratios; and false discovery rate (FDR) thresholds were set to < 1 % for both peptide and protein identifications to ensure high confidence in the results, as described in recent studies [23], [24].

2.5. Identification of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) and differentially expressed proteins (DEPs)

Genes that showed significant differences in their expression were filtered using DESeq2 (http://bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/DESeq2.html). Protein identification and quantification were performed using the MASCOT engine (v 2.2; Matrix Science, London, UK) integrated within Proteome Discoverer 2.4 software. Specifically, genes or proteins with fold change (FC) > 1.2 or < 0.83 and p-value < 0.05 were classified as being significantly differentially expressed.

2.6. Functional enrichment analysis

Gene ontology (GO) analysis was conducted using the ‘clusterProfiler’ package in R (v3.18.1) [25], which comprehensively categorized gene functions across three major domains, namely, biological processes (BP), cellular components (CC), and molecular functions (MF) [26]. Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment analysis was conducted using the KOBAS database (version 13). Overrepresentation significance was determined by adjusted p-values < 0.05.

2.7. Protein-protein interaction (PPI) network analysis

To establish the PPI network, the common DEGs/DEPs were uploaded into the STRING database (v11.5; http://string-db.org/) with default parameters to predict potential protein–protein interactions [27], [28]. The predicted interactions were imported into Cytoscape (version 3.9.1) for visualization, where isolated nodes (degree ≤ 2) were systematically filtered to refine network topology [29]. Hub gene identification was conducted through CytoHubba (v1.6.1) using seven topological algorithms: Closeness, Degree, Stress, Radiality, Maximum Neighborhood Component (MNC), Maximal Clique Centrality (MCC), and Edge Percolated Component (EPC). The top 10 genes from each algorithm were consolidated into a composite flower plot to identify consensus hub genes [30].

2.8. Immunofluorescence staining

Frozen corneal sections were first permeabilized with 0.3 % Triton X-100 at room temperature for 15 min and then incubated for 1 h with 5 % donkey serum to block non-specific binding of primary and secondary antibodies. After washing, the sections were incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies against α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) (Proteintech, Wuhan, China; 1:200 dilution), collagen III (Proteintech, Wuhan, China; 1:200 dilution), Krt13 (Proteintech, Wuhan, China; 1:200 dilution), Krt14 (Bioss, Beijing, China; 1:200 dilution), Krt17 (Proteintech, Wuhan, China; 1:200 dilution), and Krt19 (Proteintech, Wuhan, China; 1:200 dilution). Secondary antibody incubation was carried out using species-matched fluorescein-conjugated antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch, PA, USA; 1:500 dilution) for 1 h at room temperature in a humidity chamber. Following 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) nuclear counterstaining (10 min), slides were mounted with anti-fade medium (ProLong Gold; Thermo Fisher Scientific, CA, USA) and observed under a fluorescence microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). Quantitative analysis of fluorescence intensity was performed using ImageJ with consistent threshold settings across all samples, as previously described [31].

2.9. Cell culture and transfection

The HCE-2 cell line (CRL-11135), a human SV40 immortalized corneal epithelial cell line, was obtained from ATCC (Manassas, VA, USA). Cells was seeded into six-well plates and cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM)/F12 supplemented with 10 % fetal bovine serum, 5 µg/mL insulin, 5 ng/mL human epidermal growth factor, and 0.5 % penicillin–streptomycin at 37°C under 95 % humidity and 5 % CO2 until the cells reached 70 %-80 % confluency. The telomerase-immortalized human corneal stromal keratocytes, HTK cell line (originally established and provided by Prof. Jester, University of California), was maintained in DMEM containing 10 % fetal bovine serum, penicillin (100 U/mL), and streptomycin (100 μg/mL). Then, the medium was replaced with serum-free medium the day before transfection to induce cell starvation. The Krt13-overexpressing plasmid and control plasmid (Genomeditech, Shanghai, China) were transfected into the cells for 6 h using Lipofectamine 3000 transfection reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. In brief, transfection was optimized using a plasmid:Lipofectamine 3000 ratio of 1:2 (w/v) - specifically, 2.5 μg Krt13 plasmid (1 μg/μL in TE buffer) complexed with 5 μL Lipofectamine 3000 in 500 μL Opti-MEM per well of 6-well plate. After 48 h, the cells were harvested to confirm the transfection efficiency through quantitative PCR (qPCR) and western blotting. The transfected cells were used for further analysis.

2.10. Real-time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was isolated using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The concentration of RNA was determined using NanoDrop 2000 software (Thermo Fisher Scientific, CA, USA). Next, 2000 ng of RNA was reverse-transcribed into cDNA using PrimeScript RT Reagent Kit (Takara Bio, Shiga, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. qPCR detection was performed using Hieff UNICON SYBR Green Master Mix (Yeasen, Shanghai, China) via a real-time PCR detection system (Applied Biosystems, Thermo Scientific, CA, USA). The relative mRNA expression level of the target gene was reported as the fold change relative to the control, normalized to the expression of the housekeeping gene glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) [32]. The specific primer sequences (Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China) are listed in Table S1.

2.11. Western blot analysis

Lysates of cell samples were prepared in RIPA lysis buffer (Beyotime, Jiangsu, China) supplemented with 1 mM PMSF (Beyotime, Jiangsu, China) and 1 × protease inhibitor cocktail (NCM biotech, Jiangsu, China). The resultant protein extract was fractionated by 10 % SDS-PAGE and transferred to polyvinyl difluoride membranes (Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA). The membranes were blocked using 5 % skim milk for 1 h at room temperature and incubated overnight with primary antibodies against Krt13 (Proteintech, Wuhan, China; 1:5000 dilution) and GAPDH (Proteintech, Wuhan, China; 1:10000 dilution) at 4°C. The primary antibodies were not directly tagged. Next, the blots were washed three times in tris-buffered saline with Tween and further incubated for 1 h at room temperature with horseradish peroxidase–conjugated secondary antibodies (Goat Anti-Rabbit / Mouse IgG-HRP, Proteintech, Wuhan, China; 1:5000 dilution). For detection, an enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) substrate (Beyotime, Jiangsu, China) was applied to the membranes, and the signal was captured using a chemiluminescence imaging system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). GAPDH was used as the internal reference, and protein bands were quantified using the ImageJ software [33].

2.12. Statistical analysis

Data processing and statistical analyses were conducted using the R software v.4.1.2 and GraphPad Prism 10.1.0. Significant differences were evaluated using the two-sample Wilcoxon test and t-test. The Benjamini–Hochberg method was used to calculate adjusted p values, and p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001).

3. Results

3.1. Establishment and evaluation of corneal scarring in a murine model

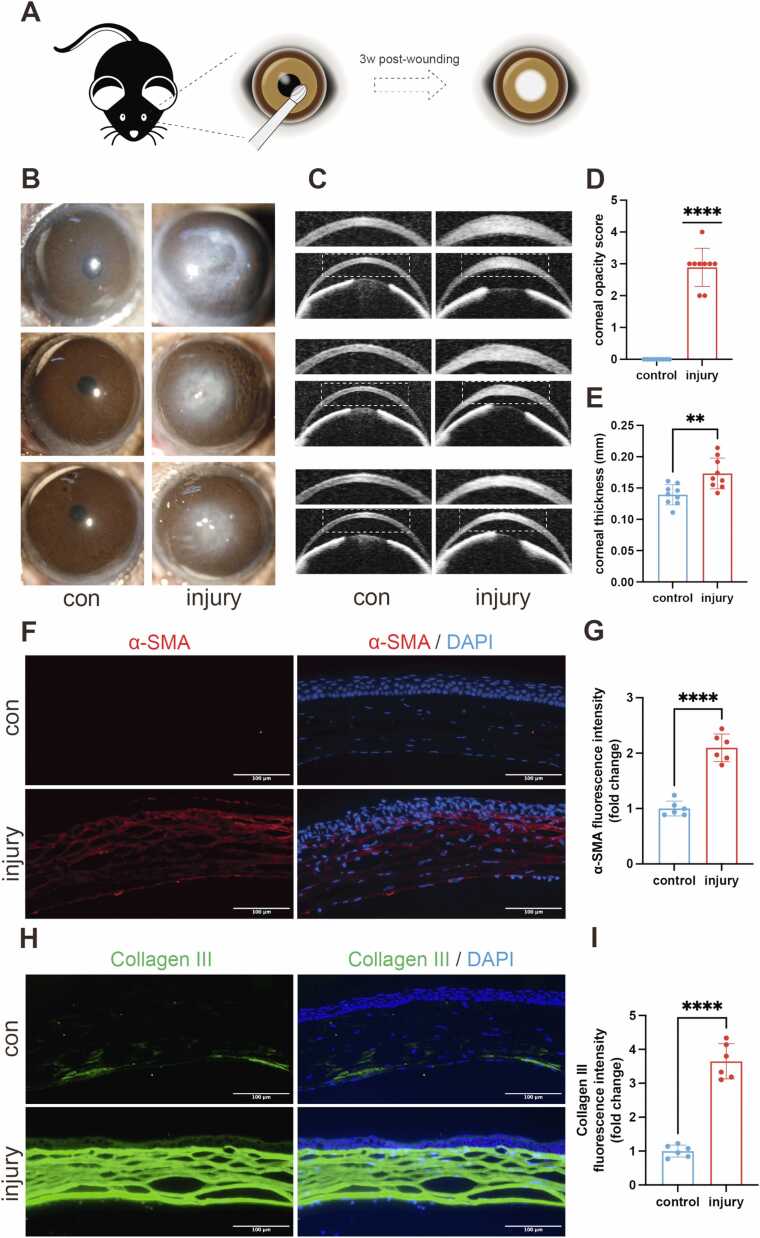

A murine model of corneal scarring was prepared using a surgical model of stromal injury (Fig. 1A), and the model was assessed with ASOCT to confirm stromal injury (Figure S1A). Corneal scarring was evaluated at 3 weeks post-wounding. Under slit-lamp microscope examination, we observed mild-to-moderate corneal opacification (grade 2–3) in most injured eyes, with one case demonstrating severe opacification (grade 4), while untreated control group maintained transparency (Fig. 1B and D, Figure S1B). ASOCT was used to visualize changes in corneal structure and measure corneal thickness. Following stromal injury, the corneal thickness significantly increased, with no sign of anterior chamber angle closure (Fig. 1C and E, Figure S1C).

Fig. 1.

Induction of a murine model of corneal scarring. (A) Schematic of the procedure. (B) Representative slit-lamp microscopy photographs of the control (con) and injured corneas. (C) Representative ASOCT photographs of the control and injured corneas. (D) Analysis of corneal opacity score (n = 9). (E) Analysis of corneal thickness in the two groups (n = 9). (F) Representative immunofluorescence images of α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) in the central corneas in the control and injury groups. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI. Scale bar, 100 μm. (G) Analysis of fluorescence intensity of α-SMA in the two groups (n = 6), presented as mean ± SD. (H) Representative immunofluorescence images of collagen type III (Col III) in the central corneas in the control and injury groups. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI. Scale bar, 100 μm. (I) Analysis of fluorescence intensity of Col III in the two groups (n = 6), presented as mean ± SD, * *p < 0.01, * ** *p < 0.0001.

The expression of α-SMA and collagen type III (Col III) in the cornea was evaluated via immunofluorescence 3 weeks post-wounding. α-SMA is a fibrotic marker, and collagen III is expressed during corneal inflammatory and wound healing processes [1]. Quantitative analysis revealed significant increases in stromal fibrosis markers, with α-SMA demonstrating a 2.10 ± 0.26-fold elevation (mean ± SD, p < 0.0001; Fig. 1F-G) and Col III showing a 3.65 ± 0.50-fold upregulation (mean ± SD, p < 0.0001; Fig. 1H-I) compared to controls, collectively confirming the successful induction of a corneal scarring model.

3.2. DEGs and DEPs in corneal scarring

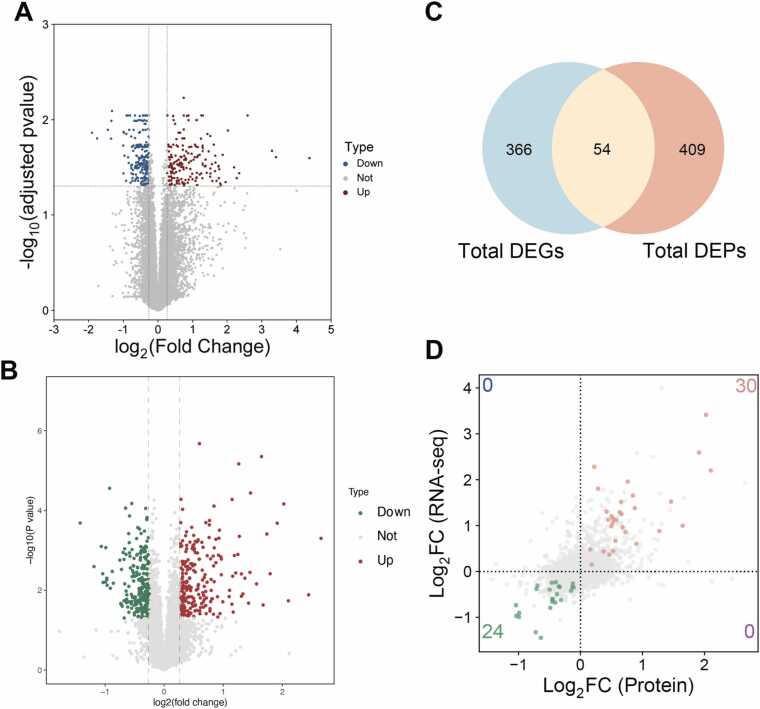

The transcriptomic cohort comprised 6 corneas with grades 2–4, whereas proteomic analysis used 3 samples with higher-grade scarring (grades 3–4) to prioritize severe fibrotic signatures. Scarred corneal tissues were subjected to RNA sequencing (n = 6 biological replicates per group) and proteomic analysis (n = 3 biological replicates per group), and the results were compared with those of the control group to identify altered genes and proteins involved in the fibrotic process. PCA (Principal Component Analysis) analysis showed good separation on expression profiles between the scarring and control groups (Figure S2A-B). Based on the differential expression analysis of transcriptomic and proteomic data, 420 DEGs and 463 DEPs were identified, respectively (Fig. 2A-B, Figure S2C-D). Venn analysis indicated that 54 factors were regulated concurrently at both gene and protein levels (Fig. 2C). The patterns of protein and mRNA expression were analyzed, which revealed a nonlinear correlation. The 54 common DEGs/DEPs demonstrated concordant expression patterns across transcriptional and translational levels, specifically showing unidirectional regulation where increased mRNA levels corresponded with elevated protein abundance (30 genes), while decreased mRNA expression paralleled reduced protein quantities (24 genes) (Fig. 2D).

Fig. 2.

Volcano plots were generated to visualize (A) differentially expressed genes (DEGs) and (B) differentially expressed proteins (DEPs). (C) The Venn diagram identified 54 common factors among the DEGs and DEPs. (D) Four-quadrant plot analysis showing gene distribution at both mRNA and protein levels. Common DEGs/DEPs are marked with different colors according to their expression patterns. Green dots indicate reduced expression at both protein and mRNA levels. Red dots represent increased expression at both protein and mRNA levels. Blue dots indicate reduced expression at the protein level and increased expression at the mRNA level. Purple dots represent increased expression at the protein level and reduced expression at the mRNA level.

3.3. Functional enrichment analysis of DEGs/DEPs

GO and KEGG enrichment analyses were performed to identify the molecular functions and pathways that were significantly enriched in DEGs/DEPs. Significantly enriched GO terms shared between DEGs and DEPs were selected, and the top 20 consensus terms (biological process (BP): 8 terms; cellular component (CC): 8 terms; molecular function (MF): 4 terms) were visualized in Fig. 3 and listed in Table S2. GO analysis revealed that the BP of the common DEGs/DEPs were primarily related to the regulation of supramolecular fiber organization, regulation of actin filament organization, regulation of actin cytoskeleton organization, actin filament organization, and regulation of actin filament-based process and wound healing. Moreover, the CC of these DEGs/DEPs were predominantly enriched in the collagen-containing ECM, apical part of the cell, apical plasma membrane, and cluster of actin-based cell projections. Regarding MF, the DEGs/DEPs were primarily involved in ECM structural constituents, actin binding, integrin binding, and cell adhesion molecule binding.

Fig. 3.

Gene Ontology (GO) analysis showing the top 20 annotated common DEGs/DEPs in scarred corneas.

KEGG analysis demonstrated that DEGs were primarily implicated in Staphylococcus aureus infection, Chagas disease, complement and coagulation cascades, Hippo signaling pathway, TNF signaling pathway, MAPK signaling pathway, cytokine–cytokine receptor interaction, osteoclast differentiation, leishmaniasis, and tight junction (Fig. 4A). Furthermore, DEPs were primarily associated with the metabolism of xenobiotics by cytochrome P450, S. aureus infection, fluid shear stress and atherosclerosis, estrogen signaling pathway, glutathione metabolism, biosynthesis of nucleotide sugars, carbon metabolism, pentose phosphate pathway, biosynthesis of amino acids, and fructose and mannose metabolism (Fig. 4B). The expression profiles of the DEGs and DEPs significantly involved in KEGG pathways are depicted in Fig. 4A and B along with their corresponding numbers. For instance, 12 genes and 11 proteins were upregulated, whereas 1 gene and 4 proteins were downregulated in the S. aureus infection pathway.

Fig. 4.

Significantly overrepresented pathways from Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) analysis of DEGs (A) and DEPs (B). Quantitative expression of DEGs and DEPs identified in enriched pathways. (C) Top KEGG pathways of common DEGs/DEPs in scarred corneas according to degree of enrichment.

An integrated two-omics KEGG analysis revealed that the 54 common factors were primarily enriched in starch and sucrose metabolism, S. aureus infection, regulation of actin skeleton, estrogen signaling pathway, complement and coagulation cascades, and leukocyte transendothelial migration (Fig. 4C, Table S3).

3.4. PPI network analysis

After the identification of the 54 common DEGs/DEPs, a PPI network was first constructed, encompassing 22 pivotal factors (Tpm1, Tpm4, Actn1, Fam169a, Arhgdib, Msn, Dkk3, Icam1, Serpinb1a, Anpep, Enpep, Ctsh, Rbp1, Aldh1a1, Krt19, Ceacam1, Krt13, Krt14, Krt15, Krt17, Dsg1a, and Krt6b) (Fig. 5A). A comprehensive screening strategy was performed to further extract pivotal genes using the seven distinct algorithms Closeness, Degree, Stress, Radiality, MNC, MCC, and EPC. Four hub genes were identified from the screening process as illustrated in the intersected Venn diagram (Fig. 5B). We next established a PPI network based on the identified four hub genes, including Krt13, Krt14, Krt17, and Krt19 (Fig. 5C).

Fig. 5.

(A) Protein–protein interaction (PPI) network of commonly altered DEGs/DEPs mapped via Cytoscape plugin CytoHubba. (B) Venn diagram showing four overlapping hub genes screened via seven algorithms. (C) PPI network of four hub keratin genes.

3.5. Expression levels of hub keratins

We compared the transcriptomic and proteomic expression levels of the four identified keratins (Krt13, Krt14, Krt17, and Krt19) in scarred corneal tissues. The results revealed a significant upregulation in their expression levels after stromal injury (Fig. 6A and B). Immunofluorescence of corneal sections revealed increased fluorescence intensities of Krt13 (Figs. 6C and 6G), Krt14 (Figs. 6D and 6H), Krt17 (Figs. 6E and 6I), and Krt19 (Figs. 6F and 6J) in the epithelium of scarred corneas. Notably, increased staining of Krt13 and Krt17 was observed in the corneal stroma after the injury.

Fig. 6.

Expression profiles of the four keratins. Transcriptomic (n = 6) (A) and proteomic (n = 3) (B) expression levels of the four keratins in the control and scarred groups, presented as mean ± SD, *p < 0.05. (C) Representative immunofluorescence images of keratin 13 (Krt13) in the central corneas in the two groups. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI. Scale bar, 100 μm. (D) Representative immunofluorescence images of keratin 14 (Krt14) in the central corneas in the two groups. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI. Scale bar, 100 μm. (E) Representative immunofluorescence images of keratin 17 (Krt17) in the central corneas in the two groups. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI. Scale bar, 100 μm. (F) Representative immunofluorescence images of keratin 19 (Krt19) in the central corneas in the two groups. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI. Scale bar, 100 μm. (G-J) Analysis of fluorescence intensities of Krt13, Krt14, Krt17, and Krt19 in the two groups (n = 6), presented as mean ± SD, * *p < 0.01.

3.6. Krt13 promoted epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) in corneal epithelial cells

In vitro experiments were conducted to validate the potential role of keratins in corneal scarring. Based on the expression profiles of the four keratins, Krt13, which was relatively highly enriched in scarred corneas, was selected as the target gene to construct the Krt13-overexpressing plasmid. After overexpressing Krt13 in corneal epithelial cells (Fig. 7A-C), the expression levels of mesenchymal cell markers, including snail, slug, vimentin, and fibronectin (FN), were significantly upregulated (Fig. 7D). Notably, parallel experiments in stromal keratocytes revealed similar profibrotic effects – Krt13 plasmid-transfected stromal cells exhibited significant FN upregulation (Figure S3). These dual epithelial-stromal effects revealed a potential involvement of keratins in corneal scarring.

Fig. 7.

Validation of Krt13 overexpression in corneal epithelial cells. (A) Representative western blot of Krt13 protein levels. GAPDH served as a loading control. (B) Densitometric quantification of Krt13 band intensity normalized to GAPDH (n = 3 biological replicates). (C) qPCR analysis of Krt13 mRNA levels (n = 6 biological replicates; ΔΔCt method normalized to GAPDH). (D) Overexpression of Krt13 in corneal epithelial cells induced the upregulation of mesenchymal cell markers (snail, slug, vimentin, and fibronectin [FN])), as determined via qPCR, presented as mean ± SD, *p < 0.05, * *p < 0.01, * ** *p < 0.0001.

4. Discussion

Restoration of corneal stromal integrity is critical for the recovery of corneal clarity after ocular trauma. This intricate process involves epithelium-derived cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors that penetrate through compromised epithelial-stromal interfaces. These mediators activate quiescent keratocytes, inducing their transformation into myofibroblasts that secrete ECM components for stromal repair. Persistent myofibroblast activity leads to pathological ECM deposition and scar formation. To further explore corneal responses to stromal injury, in vivo corneal scarring models were established, including chemical (alkali burn) and surgical models of stromal injury in mice or rabbits [20], [34], [35]. In the present study, we used a surgical model of stromal excision in mice and further explored the transcriptomic and proteomic changes after scar formation. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to integrate transcriptomics and proteomics to investigate the pathogenesis of fibrosis in the cornea.

Integrating transcriptomics and proteomics data allows us to assess the correlation between mRNA expression and protein abundance, thereby providing insights into the mechanism underlying gene regulation and protein synthesis [36]. Our results revealed a nonlinear relationship between mRNA and protein levels, which is not surprising considering the variation caused by posttranscriptional regulation and measurement noise [37]. Among 420 DEGs and 463 DEPs, 54 factors showed concordant changes in the mRNA and protein expression levels after stromal injury, including 30 upregulated targets and 24 downregulated targets.

Integrative analysis of transcriptomic and proteomic profiles enables identification of core regulatory axes, providing mechanistic insights into transcriptional and post-transcriptional control during stromal fibrosis. In this study, two-omics functional enrichment analysis indicated that the regulation of cytoskeleton, immune pathway, and cellular metabolism were generally involved in the corneal stromal repair process. The regulation of actin cytoskeleton was closely linked to fibrosis development, consistent with the characteristics of scar formation. Our KEGG pathway analysis of the DEGs identified significant enrichment in Hippo signaling pathway. This computational prediction aligns with other studies, as Hippo pathway is implicated in fibrotic pathologies through its downstream effectors—Yes-associated protein (YAP) and transcriptional coactivator with PDZ-binding motif (TAZ) [38], [39]. YAP/TAZ can be activated by multiple upstream signals, including ECM stiffness and mechanical forces [40]. Notably, a significant upregulation in YAP1 expression was detected in keratoconus stromal cells [41]. While cytokine interactions were not directly measured, KEGG analysis based on our two-omics dataset provides molecular evidence supporting immune pathways activation, such as the TNF signaling pathway and cytokine–cytokine receptor interaction. Following traumatic or pathological corneal injury, the immune response is activated, which induces the migration and proliferation of immune cells and the release of cytokines. The orchestra of different infiltrating immune cells and inflammatory reactions plays a vital role in the progression of corneal fibrosis [42]. The levels of proteins involved in key metabolic pathways, including xenobiotic metabolism by cytochrome P450, glutathione metabolism, and carbon metabolism, were downregulated, indicating potential alterations in metabolic processes during stromal wound healing.

Keratins are associated with various vital functions, including preserving epithelial integrity and modulating fibrotic response, and have long been recognized as biomarkers for the diagnosis and prognosis of tumors [43], [44]. Some types of keratins regulate EMT and interact with key signaling pathways implicated in fibrosis, including the transforming growth factor β (TGF-β)/Smad signaling pathway []45], [46]. Krt8 is implicated in promoting the accumulation of transitional epithelial cells and formation of fibrosis in the lung [47]. Previous studies have reported that epithelial Krt14 and Krt16 proteins and stromal Krt12 protein are upregulated in keratoconus corneas compared with that in normal corneas [48], [49], suggesting the role of keratins in maintaining the corneal structure.

Based on the interaction network, we extracted four key keratins (Krt13, Krt14, Krt17, and Krt19) whose expression levels were remarkably elevated at both mRNA and protein levels in scarred corneal tissues. As a stemness-related modulator of cancer progression and metastasis [50], the dysregulation of Krt13 is associated with various carcinomas, including esophageal, breast, and bladder cancers [51]. Moreover, our study suggested that Krt13 overexpression in corneal epithelial cells and stromal keratocytes resulted in elevated expression of scar-related markers. Krt14, a stem cell marker in corneal epithelial cells [52], is implicated in disseminating tumor cells during breast cancer metastasis [53]. Furthermore, Krt17 is identified as a critical regulator of cellular proliferation and growth as well as an essential mediator of inflammatory processes. The levels of Krt17 are upregulated under various stress conditions, such as injury and infection [54]. Krt19 is related to unfavorable prognosis in hepatocellular and breast cancers [55], and its expression is upregulated in liver fibrosis [56]. In the current study, we detected epithelium-derived Krt13 and Krt17 in the stroma of scarred corneas, which might be due to leakage from the compromised epithelial-stromal interfaces that epithelium can sequester in corneal stroma. While some reports suggested that stromal cells in other tissues can sometimes express keratins [57], [58], it might be possible that the expression of Krt13 and Krt17 were elevated in corneal stromal cells by injury.

This study had certain limitations. First, the single timepoint analysis (3 weeks post-injury) focused on scar maturation stage and failed to cover all dynamic repair phases. The early inflammatory responses (1-week) and late remodeling stages (8-week) have not been fully studied, which may lead to the omission of key regulatory factors. Second, candidate molecules were identified through comparative transcriptome and proteome analyses. However, it is possible that some potential biomarkers, which may exhibit alterations solely at the mRNA or protein level, were excluded in our analysis. Third, although we verified keratin dysregulation in murine mechanical injury models, whether these findings can be applied to infectious (e.g., Pseudomonas keratitis) or chemical (e.g., alkali burn) scarring causes remained uncertain. Fourth, because the differentially expressed four keratins were investigated in the murine model of corneal scarring, it would be beneficial to further validate the results in scarred human donor corneas to improve the reliability and accuracy of our findings. Finally, a definitive correlation between the identified keratins and the development of corneal scarring is yet to be established. Therefore, further studies are required to explore the potential effects of keratin overexpression or knockout on in vivo corneal scarring formation and clarify the underlying mechanism.

5. Conclusion

We used a murine model of corneal scarring for a comprehensive investigation combining transcriptomics and proteomics. This analysis identified 420 DEGs and 463 DEPs, with 54 factors being commonly altered. Based on the PPI network, we further discovered four keratins (Krt13, Krt14, Krt17, and Krt19) as potential regulators. The significantly increased expression levels of these keratins in scarred corneas were validated by immunofluorescence, and Krt13 overexpression in corneal epithelial cells and stromal keratocytes was found to increase the expression of fibrotic markers. Overall, the relationship between keratins and corneal fibrosis is complex and multifaceted, necessitating further research to fully clarify the mechanisms underlying their interactions.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Tianyi Zhou: Writing – original draft, Investigation. Yuchen Cai: Methodology, Conceptualization. Fei Fang: Formal analysis. Xueyao Cai: Software, Methodology. Yao Fu: Writing – review & editing, Supervision.

Ethical statement

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shanghai Ninth People’s Hospital (SH9H-2024-A1387–1).

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82471039, 82271041, 82070919); the Program of Shanghai Academic/Technology Research Leader (22XD1401800); the Biomaterials and Regenerative Medicine Institute Cooperative Research Project, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine (2022LHA06).

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

We would like to extend our deepest appreciation to Shanghai Newcore Biotech for their contributions to the bioinformatics analysis, to Oingdao Eye Hospital of Shandong First Medical University for their support throughout the study, and to the Department of Ophthalmology, Shanghai Ninth People’s Hospital and Shanghai Key Laboratory of Orbital Diseases and Ocular Oncology for providing the research platform.

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.csbj.2025.05.042.

Contributor Information

Xueyao Cai, Email: kevin89459@alumni.sjtu.edu.cn.

Yao Fu, Email: fuyao@sjtu.edu.cn.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

Supplementary material

Supplementary material

References

- 1.Mohan R.R., Kempuraj D., D'Souza S., Ghosh A. Corneal stromal repair and regeneration. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2022;91 doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2022.101090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilson S.E. Interleukin-1 and transforming growth factor beta: commonly opposing, but sometimes supporting, master regulators of the corneal wound healing response to injury. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2021;62(4):8. doi: 10.1167/iovs.62.4.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singh V., Santhiago M.R., Barbosa F.L., Agrawal V., Singh N., Ambati B.K., et al. Effect of TGFβ and PDGF-B blockade on corneal myofibroblast development in mice. Exp Eye Res. 2011;93(6):810–817. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2011.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilson S.E. Corneal wound healing. Exp Eye Res. 2020;197 doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2020.108089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ljubimov A.V., Saghizadeh M. Progress in corneal wound healing. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2015;49:17–45. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2015.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gain P., Jullienne R., He Z., Aldossary M., Acquart S., Cognasse F., et al. Global survey of corneal transplantation and eye banking. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2016;134(2):167–173. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2015.4776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shetty R., Kumar N.R., Subramani M., Krishna L., Murugeswari P., Matalia H., et al. Safety and efficacy of combination of suberoylamilide hydroxyamic acid and mitomycin C in reducing pro-fibrotic changes in human corneal epithelial cells. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):4392. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-83881-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moshirfar M., Wang Q., Theis J., Porter K.C., Stoakes I.M., Payne C.J., et al. Management of corneal haze after photorefractive keratectomy. Ophthalmol Ther. 2023;12(6):2841–2862. doi: 10.1007/s40123-023-00782-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jacob J.T., Coulombe P.A., Kwan R., Omary M.B. Types I and II keratin intermediate filaments. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2018;10(4) doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a018275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hsu C.-K., Lin H.-H., Harn H.I.C., Hughes M.W., Tang M.-J., Yang C.-C. Mechanical forces in skin disorders. J Dermatol Sci. 2018;90(3):232–240. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2018.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Irvine A.D., Corden L.D., Swensson O., Swensson B., Moore J.E., Frazer D.G., et al. Mutations in cornea-specific keratin K3 or K12 genes cause Meesmann's corneal dystrophy. Nat Genet. 1997;16(2):184–187. doi: 10.1038/ng0697-184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Borrelli M., Joepen N., Reichl S., Finis D., Schoppe M., Geerling G., et al. Keratin films for ocular surface reconstruction: evaluation of biocompatibility in an in-vivo model. Biomaterials. 2015;42:112–120. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.11.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reichl S., Borrelli M., Geerling G. Keratin films for ocular surface reconstruction. Biomaterials. 2011;32(13):3375–3386. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.01.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cao Z., Wu H.K., Bruce A., Wollenberg K., Panjwani N. Detection of differentially expressed genes in healing mouse corneas, using cDNA microarrays. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43(9):2897–2904. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kumar R., Tripathi R., Sinha N.R., Mohan R.R. RNA-Seq analysis unraveling novel genes and pathways influencing corneal wound healing. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2024;65(11):13. doi: 10.1167/iovs.65.11.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nishtala K., Panigrahi T., Shetty R., Kumar D., Khamar P., Mohan R.R., et al. Quantitative proteomics reveals molecular network driving stromal cell differentiation: implications for corneal wound healing. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(5) doi: 10.3390/ijms23052572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ji S., Ye L., Yuan J., Feng Q., Dai J. Integrative transcriptome and proteome analyses elucidate the mechanism of lens-induced myopia in Mice. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2023;64(13):15. doi: 10.1167/iovs.64.13.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang X., Qu M., Li J., Danielson P., Yang L., Zhou Q. Induction of fibroblast senescence during mouse corneal wound healing. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2019;60(10):3669–3679. doi: 10.1167/iovs.19-26983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cogswell D., Sun M., Greenberg E., Margo C.E., Espana E.M. Creation and grading of experimental corneal scars in mice models. Ocul Surf. 2021;19:53–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2020.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rittié L., Hutcheon A.E.K., Zieske J.D. Mouse models of corneal scarring. Methods Mol Biol. 2017;1627:117–122. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-7113-8_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Santra M., Geary M.L., Rubin E., Hsu M.Y.S., Funderburgh M.L., Chandran C., et al. Good manufacturing practice production of human corneal limbus-derived stromal stem cells and in vitro quality screening for therapeutic inhibition of corneal scarring. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2024;15(1):11. doi: 10.1186/s13287-023-03626-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gupta N., Kalaivani M., Tandon R. Comparison of prognostic value of Roper Hall and Dua classification systems in acute ocular burns. Br J Ophthalmol. 2011;95:194–198. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2009.173724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tyanova S., Temu T., Cox J. The MaxQuant computational platform for mass spectrometry-based shotgun proteomics. Nat Protoc. 2016;11(12):2301–2319. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2016.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bekker-Jensen D.B., Martínez-Val A., Steigerwald S., Rüther P., Fort K.L., Arrey T.N., et al. A compact quadrupole-orbitrap mass spectrometer with FAIMS interface improves proteome coverage in short LC gradients *. Mol Cell Proteom. 2020;19(4):716–729. doi: 10.1074/mcp.TIR119.001906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yu G., Wang L.-G., Han Y., He Q.-Y. clusterProfiler: an R package for comparing biological themes among gene clusters. OMICS. 2012;16(5):284–287. doi: 10.1089/omi.2011.0118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saxena R., Bishnoi R., Singla D. Gene Ontology: application and importance in functional annotation of the genomic data. : Singh DB, Pathak RK, Ed Bioinforma: Acad Press. 2022:145–157. Chapter 9. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Athanasios A., Charalampos V., Vasileios T., Ashraf G.M. Protein-protein interaction (PPI) network: recent advances in drug discovery. Curr Drug Metab. 2017;18(1) doi: 10.2174/138920021801170119204832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Szklarczyk D., Gable A.L., Lyon D., Junge A., Wyder S., Huerta-Cepas J., et al. STRING v11: protein-protein association networks with increased coverage, supporting functional discovery in genome-wide experimental datasets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47(D1):D607–D613. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shannon P., Markiel A., Ozier O., Baliga N.S., Wang J.T., Ramage D., et al. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 2003;13(11):2498–2504. doi: 10.1101/gr.1239303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chin C.-H., Chen S.-H., Wu H.-H., Ho C.-W., Ko M.-T., Lin C.-Y. CytoHubba: identifying hub objects and sub-networks from complex interactome. BMC Syst Biol. 2014;8((4) doi: 10.1186/1752-0509-8-S4-S11. Suppl 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jensen E.C. Quantitative analysis of histological staining and fluorescence using ImageJ. Anat Rec. 2013;296(3):378–381. doi: 10.1002/ar.22641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vandesompele J., De Preter K., Pattyn F., Poppe B., Van Roy N., De Paepe A., et al. Accurate normalization of real-time quantitative RT-PCR data by geometric averaging of multiple internal control genes. Genome Biol. 2002;3(7) doi: 10.1186/gb-2002-3-7-research0034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stael S., Miller L.P., Fernández-Fernández Á.D., Van Breusegem F. In: Methods and Protocols. Klemenčič M., Stael S., Huesgen P.F., editors. Springer US; New York, NY: 2022. Detection of Damage-Activated Metacaspase ActivityActivitiesby Western Blot in Plants; pp. 127–137. (Plant Proteases and Plant Cell Death). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang X., Qu M., Li J., Danielson P., Yang L., Zhou Q. Induction of fibroblast senescence during mouse corneal wound healing. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2019;60(10):3669–3679. doi: 10.1167/iovs.19-26983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gupta S., Rodier J.T., Sharma A., Giuliano E.A., Sinha P.R., Hesemann N.P., et al. Targeted AAV5-Smad7 gene therapy inhibits corneal scarring in vivo. PLoS One. 2017;12(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0172928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hasin Y., Seldin M., Lusis A. Multi-omics approaches to disease. Genome Biol. 2017;18(1):83. doi: 10.1186/s13059-017-1215-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vogel C., Marcotte E.M. Insights into the regulation of protein abundance from proteomic and transcriptomic analyses. Nat Rev Genet. 2012;13(4):227–232. doi: 10.1038/nrg3185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Du J., Qian T., Lu Y., Zhou W., Xu X., Zhang C., et al. SPARC-YAP/TAZ inhibition prevents the fibroblasts-myofibroblasts transformation. Exp Cell Res. 2023;429(1) doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2023.113649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ragazzini S., Scocozza F., Bernava G., Auricchio F., Colombo G.I., Barbuto M., et al. Mechanosensor YAP cooperates with TGF-β1 signaling to promote myofibroblast activation and matrix stiffening in a 3D model of human cardiac fibrosis. Acta Biomater. 2022;152:300–312. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2022.08.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dey A., Varelas X., Guan K.-L. Targeting the Hippo pathway in cancer, fibrosis, wound healing and regenerative medicine. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2020;19(7):480–494. doi: 10.1038/s41573-020-0070-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dou S., Wang Q., Zhang B., Wei C., Wang H., Liu T., et al. Single-cell atlas of keratoconus corneas revealed aberrant transcriptional signatures and implicated mechanical stretch as a trigger for keratoconus pathogenesis. Cell Discov. 2022;8(1):66. doi: 10.1038/s41421-022-00397-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stepp M.A., Menko A.S. Immune responses to injury and their links to eye disease. Transl Res. 2021;236:52–71. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2021.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Toivola D.M., Polari L., Schwerd T., Schlegel N., Strnad P. The keratin-desmosome scaffold of internal epithelia in health and disease - the plot is thickening. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2024;86 doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2023.102282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Karantza V. Keratins in health and cancer: more than mere epithelial cell markers. Oncogene. 2011;30(2):127–138. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren M., Gao Y., Chen Q., Zhao H., Zhao X., Yue W. The overexpression of keratin 23 promotes migration of ovarian cancer via epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Biomed Res Int. 2020;2020 doi: 10.1155/2020/8218735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li G., Guo J., Mou Y., Luo Q., Wang X., Xue W., et al. Keratin gene signature expression drives epithelial-mesenchymal transition through enhanced TGF-β signaling pathway activation and correlates with adverse prognosis in lung adenocarcinoma. Heliyon. 2024;10(3) doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e24549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang F., Ting C., Riemondy K.A., Douglas M., Foster K., Patel N., et al. Regulation of epithelial transitional states in murine and human pulmonary fibrosis. J Clin Invest. 2023;133(22) doi: 10.1172/JCI165612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Joseph R., Srivastava O.P., Pfister R.R. Differential epithelial and stromal protein profiles in keratoconus and normal human corneas. Exp Eye Res. 2011;92(4):282–298. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2011.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bortoletto E., Pieretti F., Brun P., Venier P., Leonardi A., Rosani U. Meta-analysis of keratoconus transcriptomic data revealed altered RNA editing levels impacting keratin genomic clusters. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2023;64(7):12. doi: 10.1167/iovs.64.7.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yin L., Li Q., Mrdenovic S., Chu G.C.-Y., Wu B.J., Bu H., et al. KRT13 promotes stemness and drives metastasis in breast cancer through a plakoglobin/c-Myc signaling pathway. Breast Cancer Res. 2022;24(1):7. doi: 10.1186/s13058-022-01502-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yu D., Chen C., Sun L., Wu S., Tang X., Mei L., et al. KRT13-expressing epithelial cell population predicts better response to chemotherapy and immunotherapy in bladder cancer: comprehensive evidences based on BCa database. Comput Biol Med. 2023;158 doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2023.106795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chen B., Mi S., Wright B., Connon C.J. Investigation of K14/K5 as a stem cell marker in the limbal region of the bovine cornea. PLoS One. 2010;5(10) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cheung K.J., Ewald A.J. A collective route to metastasis: seeding by tumor cell clusters. Science. 2016;352(6282):167–169. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf6546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yang L., Zhang S., Wang G. Keratin 17 in disease pathogenesis: from cancer to dermatoses. J Pathol. 2019;247(2):158–165. doi: 10.1002/path.5178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kawai T., Yasuchika K., Ishii T., Katayama H., Yoshitoshi E.Y., Ogiso S., et al. Keratin 19, a cancer stem cell marker in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21(13):3081–3091. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-1936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Asselah T., Bièche I., Laurendeau I., Paradis V., Vidaud D., Degott C., et al. Liver gene expression signature of mild fibrosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Gastroenterology. 2005;129(6):2064–2075. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chia Y., Thike A.A., Cheok P.Y., Yong-Zheng Chong L., Man-Kit Tse G., Tan P.H. Stromal keratin expression in phyllodes tumours of the breast: a comparison with other spindle cell breast lesions. J Clin Pathol. 2012;65(4):339–347. doi: 10.1136/jclinpath-2011-200377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Traweek S.T., Liu J., Battifora H. Keratin gene expression in non-epithelial tissues. Detection with polymerase chain reaction. Am J Pathol. 1993;142(4):1111–1118. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material

Supplementary material