Abstract

Background

The REMORA trial demonstrated efficacy and safety of lenvatinib in patients previously treated for advanced thymic carcinoma. However, more data regarding its use in clinical practice are required.

Methods

This multicenter retrospective study included consecutive patients with advanced thymic carcinoma who began lenvatinib treatment between 23 March 2021 and 31 October 2022. The primary outcome was the objective response rate in the previously treated group, with threshold and expected values based on the results of the REMORA trial and trials of other key drugs. Subgroup analyses were carried out based on REMORA trial eligibility criteria or age.

Results

Eighty-seven patients were enrolled in the previously treated group [median age, 64 years (range 38-79 years); 56 (64%) males]. Most patients [82 (94%)] had a performance status of 0 or 1; 51 (59%) met the trial eligibility criteria. The objective response rate and the disease control rate were 30% [90% confidence interval (CI) 21.3% to 39.1%] and 93% (95% CI 84.6% to 97.2%), respectively. The median progression-free survival, time to treatment failure, and overall survival were 10.2 months (95% CI 7.0-13.2 months), 11.6 months (95% CI 6.9-17.0 months), and not reached (NR; 95% CI 18.3 months-NR), respectively. Seventy-three patients (84%) required dose reduction owing to adverse events, including hypertension (22%), proteinuria (20%), and palmar–plantar erythrodysesthesia syndrome (16%). Twenty patients (23%) discontinued lenvatinib due to adverse events, including anorexia (6%), left ventricular systolic dysfunction (2%), and fatigue or malaise (2%). Two patients (2%) died of adverse events. Trial-eligible patients had significantly longer progression-free survival than that in trial-ineligible patients (14.7 months versus 7.7 months; P = 0.03). The incidence of adverse events was higher in older patients.

Conclusions

The primary endpoint was unmet; however, lenvatinib demonstrated relatively favorable efficacy and safety in patients with previously treated thymic carcinoma, even in real-world clinical practice involving diverse populations.

Key words: thymic carcinoma, lenvatinib, real-world settings, previously treated, trial eligibility, older age

Highlights

-

•

This study failed to show that the real-world efficacy of lenvatinib in pretreated TC is equivalent to the REMORA trial.

-

•

Eligibility of the REMORA trial may be associated with the efficacy of lenvatinib.

-

•

Lenvatinib was also effective against trial-ineligible or older patients.

-

•

No new safety signals were observed.

-

•

Adverse events of lenvatinib were reported more frequently in older patients.

Introduction

Thymic carcinoma (TC) is an uncommon thoracic cancer with an incidence rate of 0.03-0.29 per 100 000 person-years.1, 2, 3 More than half of TC cases are in an advanced clinical stage at diagnosis.4 Due to its rarity, however, evidence on the efficacy and safety of systemic therapy, particularly second-line therapy, is limited. Although several phase II trials have investigated the efficacy and safety of cytotoxic drugs,5, 6, 7, 8 immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs),9, 10, 11 and molecularly targeted drugs12, 13, 14 in patients with previously treated advanced TC, <50 patients were enrolled. Thus, no standard chemotherapy regimen has been established for this population.

Lenvatinib is an orally administered, molecularly targeted drug that inhibits multiple receptor tyrosine kinases, including vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) receptors, platelet-derived growth factor receptor α (PDGF-α), fibroblast growth factor receptors (FGFRs), rearranged during transfection (RET), and c-Kit. Lenvatinib monotherapy has shown efficacy against various cancer types.15,16 The REMORA trial is the only prospective trial of lenvatinib in patients with advanced TC.17 In this single-arm phase II trial, the objective response rate (ORR) was 38% (16 of 42, 90% confidence interval [CI] 25.6% to 52.0%, 95% CI 23.6% to 54.4%), disease control rate (DCR) was 95.2% (40 of 42, 95% CI 83.8% to 99.4%), median progression-free survival (PFS) was 9.3 months (95% CI 7.7-13.9 months), and median overall survival (OS) was not reached (NR; 95% CI 16.1 months-NR).17 Updated long-term follow-up data reported a median OS of 28.3 months (95% CI 17.1-34.0 months).18 These results compare favorably with those of other agents; no randomized controlled trial, however, has been conducted to establish lenvatinib as the preferred treatment. Notably, >80% of patients in REMORA experienced grade 3 or higher (grade ≥3) adverse events (AEs), and all patients required dose reductions due to AEs. Based on these findings, lenvatinib is preferred for patients with previously treated TC; however, safety concerns remain in the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guideline.19 Given the high proportion of older patients and those with comorbidities in real-world settings, it remains unclear whether lenvatinib can demonstrate efficacy and safety comparable to those observed in REMORA. Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of lenvatinib in clinical practice for patients with advanced TC.

Material and methods

Study design and participants

This retrospective, multicenter cohort study included consecutive patients with advanced or recurrent TC who received lenvatinib between 23 March 2021 and 31 October 2022 (lenvatinib was approved for advanced TC in Japan on 23 March 2021). The cut-off date for data analysis was 14 April 2023. The eligibility criteria were as follows: (i) pathologically diagnosed with TC by local investigators; (ii) aged 18 years and older (≥18 years) at the initiation of lenvatinib; and (iii) either (a) or (b) as follows: (a) clinical stage III or IV based on the Masaoka–Koga classification20 without indication of radical therapy such as surgery and radiotherapy and (b) post-operative- or radiotherapy-recurrent disease. Additionally, patients with thymic neuroendocrine neoplasms, which are distinguished from TC according to the World Health Organization classification of thymic epithelial tumors,21 were included in accordance with the Japanese guideline for thymic tumors.22

Local investigators manually collected patient data using medical records and recorded the data in electronic case report forms. Study coordinators received electronic case report forms composed of fully anonymized data and carried out data cleaning and validation before statistical analysis to control data quality, including outliers and missing value assessments.

This study complied with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki of the World Medical Association. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Chiba University Hospital. Informed consent was obtained from participants to use their medical data, using the opt-out method based on a disclosure document. The study registration number is UMIN000051645.

Definitions of subgroups

Patients who met the key eligibility criteria for REMORA were defined as the eligible group; these criteria are listed in Supplementary Table S1, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2025.105301. Missing data were predefined as meeting the relevant criteria. Older age was predefined using two cut-offs: ≥65 years and ≥75 years. The 65-year cut-off was selected based on its widespread use in previous oncologic studies, including REMORA, as a commonly accepted threshold for defining older patients and facilitating comparison across studies. The 75-year cut-off was additionally adopted to address the under-representation of patients aged ≥75 years in REMORA and in response to safety concerns associated with anti-angiogenic agents in this age group, as reported in studies of nonthymic malignancies.23, 24, 25, 26 In addition, as the long-term analysis of REMORA suggested a correlation between efficacy and relative dose intensity (RDI),18 an exploratory analysis of RDI was carried out. Patients with RDI ≥75% or = 100% at 4 or 8 weeks were defined as the high-RDI group.

Clinical endpoints

The primary outcome was ORR assessed by local investigators in the previously treated group. Secondary outcomes included DCR, PFS, time to treatment failure (TTF), OS, and safety in the previously treated group. Subgroup analyses of the differences in efficacy and safety were carried out between the eligible and ineligible groups, as well as between older and non-older patients.

Tumor response was evaluated by investigators at each participating institution according to the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) guideline version 1.1.27 Best overall response categories included complete response (CR), partial response (PR), stable disease (SD), progressive disease, and not evaluated. The ORR was defined as the proportion of patients whose best overall response was CR or PR. The DCR was defined as the proportion of patients whose best response was CR, PR, or SD. The PFS was defined as the time from the first lenvatinib dose to disease progression or death from any cause. The TTF was defined as the time from the first dose to permanent discontinuation of lenvatinib for any cause. The OS was defined as the time from the first dose to death from any cause. The AEs were assessed from medical records according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 5.0. Any grade AEs of special interest (Supplementary Table S2, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2025.105301), all grade ≥3 AEs, and all AEs leading to dose reduction, dose interruption, or treatment discontinuation were extracted.

Statistical analysis

The required sample size was estimated using a binomial test based on a threshold value of 25%, expected value of 38%, 80% power, and an α value of 0.05 (one-sided). The threshold value was determined based on the results of clinical trials of sunitinib12,13 and S-1,5,6 whereas the expected value was determined based on the results of REMORA.17 Accordingly, the planned sample size was 80. The 90% and 95% CIs for ORR and 95% CI for DCR were calculated using the Clopper–Pearson method. The best change in tumor size assessed by local investigators for each patient is shown as a waterfall plot. The Kaplan–Meier method was used to estimate PFS, TTF, and OS, with 95% CIs calculated using the Greenwood variance estimate. The log-rank test was used to compare the groups. Statistical analyses were carried out using R (version 4.5.0; The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria), RStudio (version 2024.12.1; Posit Software, Boston, MA), and EZR (version 1.68; Saitama Medical Center, Jichi Medical University, Japan).28

Results

Patient characteristics in the overall population

In total, 107 patients from 31 institutions across Japan were enrolled, of whom 87 were classified as the previously treated group. A patient flowchart following the European Society for Medical Oncology Guidance for Reporting Oncology real-World evidence (ESMO-GROW)29 is shown in Supplementary Figure S1, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2025.105301. Baseline patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The median age was 64 years (range 38-79 years), and 56 patients (64%) were males. Eighty-two patients (94%) had a performance status of 0 or 1. Squamous-cell carcinoma was the predominant histological type (71 patients, 82%). Seventeen patients (20%) had previously undergone radical surgery, and 32 patients (37%) had received thoracic radiotherapy. Seventy-four patients (85%) had previously received carboplatin combined with paclitaxel or nanoparticle albumin-bound paclitaxel, whereas only one patient (1%) had received a VEGF inhibitor-containing regimen and four (5%) had received an ICI-containing regimen. Forty-one patients (47%) initiated lenvatinib as second-line treatment. Seventy-eight patients (90%) started lenvatinib at 24 mg/day. Fifty-one patients (59%) met the key eligibility criteria for REMORA. The primary endpoint, ORR, was evaluated in 81 patients (93%) with target lesions at the initiation of lenvatinib treatment.

Table 1.

Baseline patient characteristics

| Characteristic | Patients (N = 87) |

|---|---|

| Median age, years (range) | 64 (38-79) |

| ≥65 years, n (%) | 42 (48) |

| ≥75 years, n (%) | 11 (13) |

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Male | 56 (64) |

| Female | 31 (36) |

| Smoking history, n (%) | |

| Current smoker | 9 (10) |

| Former smoker | 54 (62) |

| Never smoker | 24 (28) |

| ECOG performance status, n (%) | |

| 0 | 25 (29) |

| 1 | 57 (66) |

| 2 | 4 (5) |

| 3 | 1 (1) |

| Histological type, n (%) | |

| Squamous-cell carcinoma | 71 (82) |

| Undifferentiated carcinoma | 3 (3) |

| Lymphoepithelial carcinoma | 1 (1) |

| Adenocarcinoma | 1 (1) |

| Basaloid carcinoma | 1 (1) |

| Unknown | 2 (2) |

| Neuroendocrine neoplasma | 8 (9) |

| Stage at diagnosis (Masaoka–Koga classification), n (%) | |

| I-IIbb | 5 (6) |

| III | 16 (18) |

| IVa | 22 (25) |

| IVb | 43 (49) |

| Unknown | 1 (1) |

| Previous radical surgery (R0 resection), n (%) | 17 (20) |

| Previous thoracic radiotherapy, n (%) | 32 (37) |

| Previous systemic therapy, n (%) | |

| Combination regimens, n (%) | |

| Carboplatin + (nab-)paclitaxel | 74 (85) |

| Cisplatin + cyclophosphamide + doxorubicin ± vincristine | 12 (14) |

| Platinum and etoposide | 8 (9) |

| ICI + platinum-doublet chemotherapy | 3 (3) |

| Carboplatin + amrubicin | 2 (2) |

| Cisplatin + irinotecan | 2 (2) |

| Carboplatin + paclitaxel + bevacizumab | 1 (1) |

| Others | 2 (2) |

| Monotherapy | |

| S-1 | 25 (29) |

| Amrubicin | 15 (17) |

| Docetaxel | 9 (10) |

| Gemcitabine | 4 (5) |

| Nab-paclitaxel | 4 (5) |

| Irinotecan | 3 (3) |

| Pemetrexed | 3 (3) |

| ICI monotherapy | 2 (2) |

| Others | 2 (2) |

| Starting dose per day, n (%) | |

| 24 mg | 78 (90) |

| Other dosesc | 9 (10) |

| Treatment line of lenvatinib therapy, n (%) | |

| Second line | 41 (47) |

| Third line | 16 (18) |

| Fourth line | 15 (17) |

| Fifth or later line | 15 (17) |

| With target lesions at the start of lenvatinib, n (%) | 81 (93) |

| Metastatic sites at the start of lenvatinib, n (%) | |

| Pleural dissemination | 61 (70) |

| Malignant pleural effusion | 26 (30) |

| Pericardial dissemination or malignant pericardial effusion | 24 (28) |

| Lung | 36 (41) |

| Brain | 3 (3) |

| Bone | 28 (32) |

| Liver | 27 (31) |

| Intrathoracic lymph node | 50 (57) |

| Extrathoracic lymph node | 14 (16) |

| Other distant metastasis | 2 (2) |

| Macrovascular invasion, n (%) | |

| Arterial invasion | 4 (5) |

| Venous invasion | 9 (10) |

| Medical history of special interest, n (%) | |

| Hypertension | 27 (31) |

| Thromboembolism | 7 (8) |

| Hypothyroidism | 3 (3) |

| REMORA key eligibility criteria met, n (%) | |

| Yes | 51 (59) |

| No | 36 (41) |

| Reason for trial ineligibility, n (%) | |

| ECOG performance status 2-3 | 5 (6) |

| Unrecovered adverse events caused by previous treatment | 13 (15) |

| Organ dysfunction | |

| Platelet count <10.0 × 104/μl | 2 (2) |

| Hemoglobin <9.0 g/dl | 8 (9) |

| Increased AST and ALT | 3 (3) |

| Total bilirubin >1.8 mg/dl | 4 (5) |

| Serum creatinine >1.5 mg/dl | 4 (5) |

| PT-INR >1.5 | 3 (3) |

| Hyperproteinuria | 2 (2) |

| Pre-existing interstitial lung disease | 5 (6) |

| Histological type of neuroendocrine neoplasm | 8 (9) |

ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; (nab-)paclitaxel, (nanoparticle albumin-bound) paclitaxel; ICI, immune checkpoint inhibitor; PT-INR, prothrombin time –international normalized ratio.

Eight patients with neuroendocrine neoplasm were included: six with large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma, one with neuroendocrine carcinoma, and one with atypical carcinoid.

All cases corresponding to this stage were recurrent cases.

Two patients (one eligible and one ineligible) started lenvatinib at a dose of 20 mg, five (two eligible and three ineligible) at 14 mg, one (eligible) at 12 mg, and one (ineligible) at 4 mg.

Outcomes in the overall population

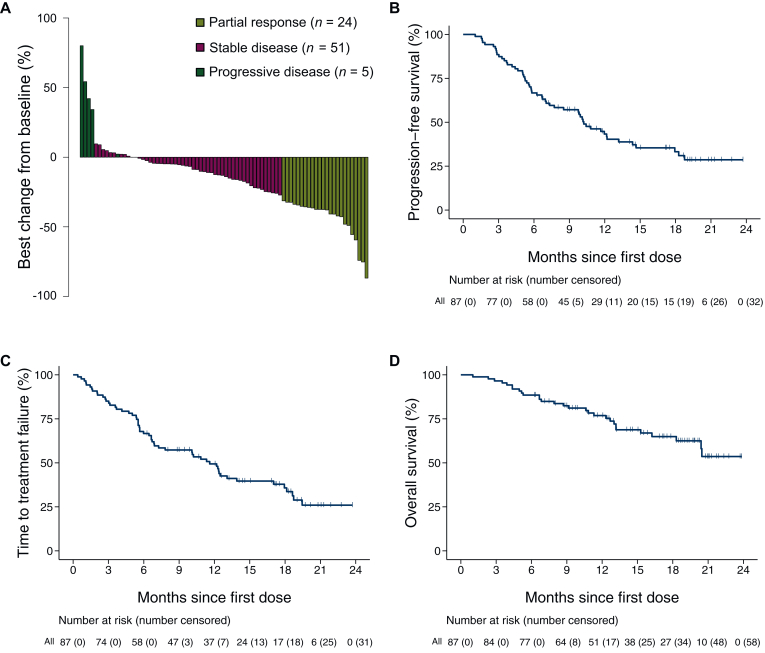

The median observation period was 13.2 months (interquartile range 8.8-18.9 months). Among 81 patients with target lesions at baseline, the ORR was 30% (90% CI 21.3% to 39.1%, 95% CI 20.0% to 40.8%). No patients achieved CR, whereas 24 achieved PR (Table 2, Figure 1A). Therefore, this study did not meet the primary endpoint. The DCR was 93% (95% CI 84.6% to 97.2%; Table 2). In the responders, the median time to response was 2.3 months (95% CI 1.2-7.9 months; Table 2), and the median duration of response was 10.3 months (95% CI 6.0 months-NR; Table 2). Among all 87 patients, 55 (63%) experienced a PFS event, 56 (64%) experienced a TTF event, and 29 (33%) experienced an OS event. The median PFS was 10.2 months (95% CI 7.0-13.2 months; Figure 1B), and the 12-month PFS rate was 43% (95% CI 32.3% to 53.8%; Table 2). The median TTF was 11.6 months (95% CI 6.9-17.0 months; Figure 1C); the 12-month TTF rate was 49% (95% CI 38.3% to 59.6%; Table 2). The median OS was NR (95% CI 18.0 months-NR; Figure 1D), and the 12-month OS rate was 77% (95% CI 66.0% to 84.6%; Table 2). Among the 56 patients who discontinued lenvatinib, 28 (50%) received at least one subsequent chemotherapy (Supplementary Table S3, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2025.105301).

Table 2.

Efficacy outcomes of lenvatinib in the overall population

| Response in patients with target lesions | Patients |

|---|---|

| (N = 81) | |

| Best overall response, n (%) | |

| Complete response | 0 |

| Partial response | 24 (30) |

| Stable disease | 51 (63) |

| Progressive disease | 5 (6) |

| Not evaluable | 1 (1) |

| Objective response rate | 30% |

| 90% CIa | 21.3% to 39.1% |

| 95% CI | 20.0% to 40.8% |

| Disease control rate (95% CI) | 93% (84.6% to 97.2%) |

| Median time to response in responders (range), months | 2.3 (1.2-7.9) |

| Median duration of response in responders (95% CI), months | 10.3 (6.0-NR) |

| Time-to-event outcomesin all patients | (N = 87) |

| Median progression-free survival (95% CI), months | 10.2 (7.0-13.2) |

| 12-month progression-free survival rate (95% CI) | 43% (32.3% to 53.8%) |

| Median time to treatment failure (95% CI), months | 11.6 (6.9-17.0) |

| 12-month time to treatment failure rate (95% CI) | 49% (38.3% to 59.6%) |

| Median overall survival (95% CI), months | NR (18.9-NR) |

| 12-month overall survival rate (95% CI) | 77% (66.0% to 84.6%) |

CI, confidence interval; NR, not reached.

Corresponding to primary analysis.

Figure 1.

Graphical summary of lenvatinib efficacy in the overall population. Waterfall plot of tumor size assessment by local investigators (A) and Kaplan–Meier curves of progression-free survival (B), time to treatment failure (C), and overall survival (D) are shown. In (A), the waterfall plot includes only patients with baseline and postbaseline target lesion measurements. In (B), (C), and (D), the tick marks indicate censored data.

Safety in the overall population

The AEs in the overall population are listed in Tables 3 and 4 and Supplementary Table S4, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2025.105301. All patients experienced at least one AE. The most frequent AEs were hypertension (75%), proteinuria (66%), and fatigue or malaise (56%). Fifty-six patients (64%) experienced at least one grade ≥3 AE. The most frequent grade ≥3 AEs were hypertension (22%), proteinuria (17%), and decreased platelet count (10%). Two patients (2%) experienced pneumonitis as an AE, one grade 2 and one grade 3. The AEs leading to dose reduction were observed in 73 patients (84%). The most common AEs were hypertension (22%), proteinuria (20%), and palmar–plantar erythrodysesthesia syndrome (16%). The AEs leading to dose interruption, defined as temporary discontinuation with resumption at the same dose, were observed in 14 patients (16%). The most common AEs were proteinuria (3%), fatigue or malaise (2%), increased aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels (2%), abdominal pain (2%), and maculopapular rash (2%). The AEs leading to treatment discontinuation were observed in 20 patients (23%). The most common AEs were anorexia (6%), left ventricular systolic dysfunction (2%), and fatigue or malaise (2%). Two patients (2%) died of AEs, one of arterial thromboembolism, and one of pleural infection.

Table 3.

Adverse events of special interest and other grade ≥3 adverse events in the overall population

| Event | This study (N = 87) |

REMORA trial (N = 42) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any grade |

Grade ≥3 |

Any grade |

Grade ≥3 |

|

| Number of patients, n (%) | ||||

| Any adverse event | 87 (100) | 56 (64) | 42 (100) | 35 (83) |

| Adverse event of special interest | ||||

| Hypertension | 65 (75) | 19 (22) | 37 (88) | 27 (64) |

| Proteinuria | 57 (66) | 15 (17) | 35 (83) | 0 |

| Fatigue or malaisea | 49 (56) | 7 (8) | 26 (62) | 0 |

| Hypoalbuminemia | 43 (49) | 1 (1) | 8 (19) | 0 |

| Platelet count decreased | 41 (47) | 9 (10) | 22 (52) | 2 (5) |

| Aspartate aminotransferase increased | 41 (47) | 5 (6) | 12 (29) | 0 |

| Anorexia | 41 (47) | 4 (5) | 18 (43) | 1 (2) |

| Palmar–plantar erythrodysesthesia syndrome | 37 (43) | 5 (6) | 29 (69) | 3 (7) |

| Diarrhea | 32 (37) | 4 (5) | 21 (50) | 2 (5) |

| Alanine aminotransferase increased | 32 (37) | 3 (3) | 11 (26) | 0 |

| Hypothyroidism | 29 (33) | 0 | 27 (64) | 0 |

| Creatinine increased | 24 (28) | 0 | 4 (10) | 0 |

| Nausea | 24 (28) | 0 | 10 (24) | 0 |

| Mucositis oral | 17 (20) | 0 | 14 (33) | 0 |

| Vomiting | 9 (10) | 0 | 9 (21) | 0 |

| Blood bilirubin increased | 8 (9) | 2 (2) | 0 | 0 |

| Headache | 7 (8) | 0 | 11 (26) | 0 |

| Pneumonitis | 2 (2) | 1 (1) | 1 (2) | 1 (2) |

| Other adverse events of grade ≥3 | Grade ≥3 | Grade ≥3 | ||

|

Number of patients, n (%) |

||||

| Left ventricular systolic dysfunction | 3 (3) | 1 (2) | ||

| Lung infection | 2 (2) | 0 | ||

| Pleural infection | 1 (1) | 0 | ||

| Abdominal pain | 1 (1) | 2 (5) | ||

| Appendicitis | 1 (1) | 0 | ||

| Small intestinal perforation | 1 (1) | 0b | ||

| Bronchopulmonary hemorrhage | 1 (1) | 0 | ||

| Thromboembolic event | 1 (1) | 0 | ||

| Arterial thromboembolism | 1 (1) | 0 | ||

| White blood cell decreased | 1 (1) | 2 (5) | ||

| Neutrophil count decreased | 1 (1) | 2 (5) | ||

| Nephrotic syndrome | 1 (1) | 0 | ||

| Hyperthyroidism | 1 (1) | 0 | ||

| Generalized muscle weakness | 1 (1) | 0 | ||

| Weight loss | 1 (1) | 1 (2) | ||

In this study, fatigue was identified with malaise because it is difficult to distinguish them based on medical records.

A similar adverse event, colonic perforation, was reported in one patient of the REMORA trial.

Table 4.

Adverse events leading to dose reduction, dose interruption, and treatment discontinuation in the overall population

| Event | This study (N = 87) |

REMORA trial (N = 42) |

|---|---|---|

| Number of patients, n (%) | ||

| Event leading to dose reduction | 73 (84) | 42 (100) |

| Event occurring in ≥2 patientsa | ||

| Proteinuria | 19 (22) | 22 (52) |

| Hypertension | 17 (20) | 10 (24) |

| Palmar–plantar erythrodysesthesia syndrome | 14 (16) | 11 (26) |

| Platelet count decreased | 13 (15) | 2 (5) |

| Fatigue or malaise | 13 (15) | 9 (21) |

| Diarrhea | 12 (14) | 5 (12) |

| Anorexia | 10 (11) | 6 (14) |

| AST or ALT increased | 5 (6) | 0 |

| Nausea | 4 (5) | 1 (2) |

| Abdominal pain | 4 (5) | 4 (10) |

| Hypothyroidism | 3 (3) | 0 |

| Weight loss | 2 (2) | 0 |

| Myalgia | 2 (2) | 0 |

| Arthralgia | 2 (2) | 3 (7) |

| Creatinine increased | 2 (2) | 0 |

| Mucositis oral | 2 (2) | 2 (5) |

| Event leading to dose interruptionb | 14 (16) | 13 (31) |

| Event occurring in ≥2 patientsa | ||

| Proteinuria | 3 (3) | 1 (2) |

| Fatigue or malaise | 2 (2) | 2 (5) |

| AST or ALT increased | 2 (2) | 0 |

| Abdominal pain | 2 (2) | 0 |

| Rash maculopapular | 2 (2) | 0 |

| Event leading to treatment discontinuation | 20 (23) | 7 (17) |

| Anorexia | 5 (6) | 0 |

| Left ventricular systolic dysfunction | 2 (2) | 1 (2) |

| Fatigue or malaise | 2 (2) | 0 |

| Pneumonitis | 1 (1) | 1 (2) |

| Small intestinal perforation | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Pleural infectionc | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Arterial thromboembolismc | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Hypertension | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Proteinuria | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Nephrotic syndrome | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Abdominal pain | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Lung infection | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Generalized muscle weakness | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Blood bilirubin increased | 1 (1) | 0 |

ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase.

Events occurring in only one patient are shown in Supplementary Table S4, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2025.105301.

‘Dose interruption’ was defined as resumption at the same dose after interruption.

These adverse events resulted in death.

Patient characteristics, outcomes, and safety according to trial eligibility

Patient characteristics according to trial eligibility are shown in Supplementary Table S5, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2025.105301. Compared with trial-eligible patients, trial-ineligible patients more often had metastases to other organs, particularly bone, and intra- and extrathoracic lymph node. A higher number of trial-ineligible patients had previously received thoracic radiotherapy. Reasons for trial ineligibility are listed in Table 1; the most common were unrecovered AEs caused by previous treatment (36%), histological type of neuroendocrine neoplasm (22%), and decreased hemoglobin (22%).

Efficacy outcomes by trial eligibility are shown in Supplementary Table S6 and Supplementary Figure S2, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2025.105301. The ORR was 28% (13 of 46; 95% CI 16.0% to 43.5%) in the eligible group and 31% (11 of 35; 95% CI 16.9% to 49.3%) in the ineligible group. The median time to response was 2.3 months in both groups (range 1.2-7.9 months in the eligible group and 1.4-5.4 months in the ineligible group). The median duration of response was NR (95% CI 6.0 months-NR) in the eligible group and 6.5 months (95% CI 2.1-10.3 months) in the ineligible group. The DCR was 96% (44 of 46; 95% CI 85.2% to 99.5%) in the eligible group and 89% (31 of 35; 95% CI 73.3% to 96.8%) in the ineligible group. The median PFS was 14.7 months (95% CI 7.0 months-NR) in the eligible group and 7.7 months (95% CI 5.6-10.8 months) in the ineligible group (P = 0.03); the 12-month PFS rates were 55% and 27%, respectively. The median TTF was 12.4 months (95% CI 6.7-18.7 months) in the eligible group and 9.0 months (95% CI 5.5-13.1 months) in the ineligible group (P = 0.20); the 12-month TTF rates were 56% and 41%, respectively. The median OS was NR in both the eligible and ineligible groups (P = 0.09), and the 12-month OS rates were 86% and 64%, respectively.

In the ineligible group, the efficacy of lenvatinib in patients with neuroendocrine neoplasms is shown in Supplementary Table S7 and Supplementary Figure S3, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2025.105301. The ORR was 13% (1 of 8; 95% CI 0.0% to 52.7%); the DCR was 75% (6 of 8; 95% CI 35.0% to 96.8%). The median PFS, TTF, and OS were 7.7 months (95% CI 1.6 months-NR), 7.4 months (95% CI 1.1 months-NR), and NR (95% CI 3.9 months-NR), respectively.

The AEs according to trial eligibility are summarized in Supplementary Table S8, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2025.105301. Compared with trial-eligible patients, trial-ineligible patients did not show a higher incidence of grade ≥3 AEs or AEs leading to dose modification or death. Although differences were observed in the incidences of some individual AEs, a consistent trend was not identified.

Patient characteristics, outcomes, and safety according to age

Patient characteristics according to age are shown in Supplementary Table S9, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2025.105301. Hypertension was more prevalent among older patients, irrespective of the cut-off age. In contrast, non-older patients more frequently exhibited metastases to other organs, particularly bone.

Efficacy outcomes according to age group (<65 years versus ≥65 years) are presented in Supplementary Table S10 and Supplementary Figure S4, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2025.105301. The ORR was 28% (11 of 39; 95% CI 15.0% to 44.9%) in older patients (patients aged ≥65 years) and 31% (13 of 42; 95% CI 17.6% to 47.1%) in non-older patients (patients aged <65 years). The median time to response was 2.1 months (range 1.2-6.8 months) in older patients and 2.6 months (range 1.3-7.9 months) in non-older patients. The median duration of response was NR (95% CI 2.3 months-NR) in older patients and 8.5 months (95% CI 5.7 months-NR) in non-older patients. The DCR was 92% (36 of 39; 95% CI 79.1% to 98.4%) in older patients and 93% (39 of 42; 95% CI 80.5% to 98.5%) in non-older patients. The median PFS was 7.3 months (95% CI 5.4 months-NR) in older patients and 11.7 months (95% CI 8.5-17.9 months) in non-older patients (P = 0.76); the 12-month PFS rates were 41% and 44%, respectively. The median TTF was 10.1 months (95% CI 5.5-18.6 months) in older patients and 12.3 months (95% CI 6.9-17.9 months) in non-older patients (P = 0.87); the 12-month TTF rates were 45% and 54%, respectively. The median OS was NR (95% CI 15.3 months-NR) in older patients and 20.5 months (95% CI 13.2 months-NR) in non-older patients (P = 0.53); the 12-month OS rates were 75% and 79%, respectively.

A similar trend was observed when applying a cut-off age of 75 years (Supplementary Table S10 and Supplementary Figure S5, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2025.105301). The ORR was 45% (5 of 11; 95% CI 16.7% to 76.6%) in older patients (patients aged ≥75 years) and 27% (19 of 70; 95% CI 17.2% to 39.1%) in non-older patients (patients aged <75 years). The median time to response was 1.8 months (range 1.4-6.1 months) in older patients and 2.5 months (range 1.2-7.9 months) in non-older patients. The median duration of response was 8.1 months (95% CI 1.9 months-NR) in older patients and 10.3 months (95% CI 6.0 months-NR) in non-older patients. The DCR was 100% (11 of 11; 95% CI 71.5% to 100%) in older patients and 91% (64 of 70; 95% CI 82.3% to 96.8%) in non-older patients. The median PFS was 5.8 months (95% CI 3.7-12.2 months) in older patients and 10.8 months (95% CI 7.3-14.7 months) in non-older patients (P = 0.19); the 12-month PFS rates were 27% and 46%, respectively. The median TTF was 10.1 months (95% CI 3.6-18.6 months) in older patients and 12.3 months (95% CI 6.7-17.9 months) in non-older patients (P = 0.32); the 12-month TTF rates were 27% and 53%, respectively. The median OS was NR in both elderly and non-elderly patients (P = 0.98); the 12-month OS rates were 64% and 79%, respectively.

The AEs according to age are listed in Supplementary Table S11, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2025.105301. Several AEs of special interest, including hypertension, proteinuria, and hypoalbuminemia, were more frequent in older patients, with greater differences observed at the 75-year cut-off. Grade ≥3 AEs showed a similar pattern. The AEs leading to treatment discontinuation were more common in older patients, especially at the 65-year cut-off.

Efficacy according to RDI

Patient characteristics and efficacy outcomes according to RDI are presented in Supplementary Tables S12-S15 and Supplementary Figures S6 and S7, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2025.105301. With a 75% RDI cut-off at 4 weeks, efficacy was generally comparable between high- and low-RDI groups. At 8 weeks, the high-RDI group showed numerically better outcomes, although the difference was not statistically significant. In contrast, with a 100% RDI cut-off at 4 or 8 weeks, the high-RDI group consistently showed numerically better outcomes. Notably, PFS was significantly longer in the high-RDI group at the 4-week 100% cut-off (17.9 months versus 7.7 months, P = 0.01).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the largest retrospective study evaluating a single treatment regimen for TC and the first to assess the efficacy and safety of lenvatinib in previously treated advanced TC in real-world settings. In the present study, the ORR was 30%, not achieving the predefined primary endpoint based on the lower bound of the 90% CI. However, PFS and OS were comparable to those reported in REMORA, and the safety profile was similar.17

The ORR was selected as the primary endpoint based on previous studies; recent evidence suggests, however, that PFS may be a more appropriate efficacy endpoint for TC. For instance, the PECATI trial, which investigated the efficacy and safety of lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab in patients with pretreated advanced thymic malignancies, showed a relatively low ORR (21%) but a high 5-month PFS rate (91%).30 These findings imply that the ORR may not fully reflect clinical benefit in TC, where pleural dissemination is common, and RECIST-based response assessment can be challenging. Further studies are required to determine optimal efficacy endpoints for this patient population.

This study included more older patients than did REMORA, with a median age difference of 9 years, and ∼40% of patients were trial-ineligible, suggesting a poorer prognosis in our cohort. Although efficacy did not differ significantly between older and non-older patients, the PFS was significantly longer in the eligible group (median difference: 7 months). Similarly, REMORA found no age-related differences in efficacy.17 The PFS in the ineligible group was shorter but comparable to that in other drug trials (Supplementary Table S16, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2025.105301). These findings support the potential clinical efficacy of lenvatinib in patients with advanced TC, including older patients or those with comorbidities.

The overall safety profile in this study was generally consistent with that of REMORA; however, some differences were observed. Frequent AEs in the overall population were similar to those in REMORA, including hypertension, proteinuria, and fatigue or malaise.17 The incidence of grade ≥3 AEs was slightly lower than that in REMORA, although the specific events differed. For instance, in the present study, grade ≥3 proteinuria, AST elevation, and ALT elevation occurred in 17%, 6%, and 3% of patients, respectively, while these events were not reported in REMORA. Additionally, AEs not observed in REMORA, such as thromboembolism and acute cholecystitis, were not unexpected based on the results of prior lenvatinib studies on other cancers.15,16,31 The incidence of AEs leading to dose reduction or interruption was slightly lower than that in REMORA; however, the higher rate of treatment discontinuation due to toxicity may reflect increased vulnerability in specific patient subgroups.

An increased susceptibility to toxicity was suggested in older patients. In our study, older patients experienced a higher incidence of AEs, especially those leading to treatment discontinuation, irrespective of the cut-off age used. A phase III trial on thyroid cancer showed higher AE rates in older individuals.32 In contrast, PFS, TTF, and OS did not differ significantly between older and non-older patients and were comparable to those in other prospective trials. Thus, avoiding lenvatinib in older patients owing to excessive concerns about AEs is not necessary.

As in REMORA, this study suggests a positive association between a higher RDI and better efficacy. Several studies on other cancers have also indicated that a high RDI is associated with a favorable prognosis in lenvatinib treatment.33, 34, 35, 36 Furthermore, a phase II trial comparing low-dose versus standard-dose initiation of lenvatinib in thyroid cancer failed to demonstrate the noninferiority of the low-dose group.37 Although the optimal duration and threshold of RDI maintenance remain uncertain, standard-dose initiation is generally recommended. Close monitoring, particularly during the early stages of treatment, is essential for minimizing dose modifications such as interruptions or reductions.

The clinical role of lenvatinib monotherapy warrants consideration in the light of recent evidence in TC, despite increasing use of ICI- or VEGF-based combination therapies in earlier lines of treatment. First-line regimens of carboplatin and paclitaxel with ramucirumab in the RELEVENT trial and with atezolizumab in the MARBLE trial showed promising outcomes.38,39 As these regimens are expected to become first-line therapies, prior exposure to ICIs or VEGF-targeted therapies will likely increase. Furthermore, considering the results of the PECATI trial,30 pembrolizumab plus lenvatinib may be a treatment option for previously treated patients. In this evolving therapeutic landscape, lenvatinib monotherapy remains clinically relevant, particularly for patients with prior ICI exposure (as monotherapy or in combination with platinum-doublet therapy) or those ineligible for immunotherapy. Findings from nonthymic malignancies suggest that VEGF-targeted therapies may show enhanced antitumor activity after ICI treatment, potentially supporting the post-ICI role of lenvatinib monotherapy in TC.40,41 Moreover, lenvatinib exerts antitumor activity through multiple pathways beyond VEGF inhibition and may retain efficacy even after prior treatment with anti-VEGF agents, such as ramucirumab. Further research is warranted to clarify the optimal timing and position of lenvatinib monotherapy in the treatment paradigm for TC.

This study has some limitations. Firstly, because of its retrospective design, tumor assessments varied in both timing and interpretation; imaging was evaluated locally without central review. Moreover, accurate attribution of the observed AEs to lenvatinib was challenging. These factors may have led to either overestimation or underestimation of efficacy and safety. However, due to the rarity of TC, conducting prospective studies with comparable numbers of patients remains difficult. Additionally, during lenvatinib treatment, trunk computed tomography scans were carried out at a median frequency of 0.45 times per month (interquartile range 0.33-0.57 times per month) until disease progression (Supplementary Table S17, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2025.105301), which appeared generally consistent with the imaging frequency specified in other clinical trials.17,39 Although retrospective in nature, we believe that our clinical data, which included a diverse patient population, offer valuable insights into real-world practice. Secondly, because this study enrolled only patients from Japan, all participants were likely of Asian descent. Therefore, the generalizability of efficacy and safety in other racial groups remains unclear. Nevertheless, the PECATI trial conducted in Europe showed favorable efficacy and manageable toxicity of lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab in patients with TC, suggesting that its antitumor activity may not be limited by race. Thirdly, the pathological diagnoses of patients were carried out independently at each institution. Variability in histological classification across institutions may have affected efficacy evaluation. However, it should be noted that no central pathological review was carried out, even in other trials.12,17

Conclusions

This observational study did not meet the primary endpoint of ORR; however, lenvatinib showed clinically meaningful efficacy in patients with previously treated advanced or recurrent TC in real-world settings. The safety profile was comparable to that of REMORA, although increased toxicity was observed in older patients. Our findings suggest that lenvatinib is a promising treatment option for patients with previously treated advanced or recurrent TC, including older patients and those with comorbidities.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

During the preparation of this work the authors used Grammarly in order to check writing. After using this tool/service, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Acknowledgments

Funding

None declared.

Disclosure

KT reported personal fees from AstraZeneca, Chugai Pharmaceutical, Taiho Pharmaceutical, and Eisai outside the submitted work. GS reported personal fees from Ono Pharmaceutical, Chugai Pharmaceutical, AstraZeneca, Novartis, Merck Sharpe & Dohme (MSD), Pfizer, Daiichi Sankyo, and Taiho Pharmaceutical outside the submitted work. HT reported personal fees from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb (BMS), Chugai Pharmaceutical, Daiichi Sankyo, Eisai, Eli Lilly Japan, Hisamitsu Pharmaceutical, Merck, MSD, Nippon Kayaku, Novartis, Ono Pharmaceutical, Phizer, Taiho Pharmaceutical, and Takeda Pharmaceutical outside the submitted work. TSh reported grant support from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chugai Pharmaceutical, MSD, and Novartis outside the submitted work, and honoraria from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, BMS, Chugai Pharmaceutical, Daiichi Sankyo, Eli Lilly Japan, MSD, Nippon Kayaku, Novartis, Ono Pharmaceutical, Pfizer, Taiho Pharmaceutical, and Takeda Pharmaceutical outside the submitted work. TSa reported personal fees from MSD, AstraZeneca, Chugai Pharmaceutical, Pfizer, Takeda Pharmaceutical, Ono Pharmaceutical, Amgen, and Eli Lilly Japan outside the submitted work. TO reported personal fees from AstraZeneca, BMS, Chugai Pharmaceutical, Daiichi Sankyo, Eli Lilly Japan, Ono Pharmaceutical, Taiho Pharmaceutical, and Takeda Pharmaceutical outside the submitted work. NM reported grants to the institution from MSD, Chugai Pharmaceutical, and Arrivent Biopharma, and personal fees from Chugai Pharmaceutical, Boehringer Ingelheim, AstraZeneca, Taiho Pharmaceutical, MSD, Ono Pharmaceutical, Novartis, and BMS. TY reported personal fees from Daiichi Sankyo and Taiho Pharmaceutical outside the submitted work. MTac reported grants and personal fees from AstraZeneca, Chugai Pharmaceutical, and Eli Lilly Japan, and personal fees from Taiho Pharmaceutical, MSD, BMS, Ono Pharmaceutical, Nippon Boehringer Ingelheim, Takeda Pharmaceutical, Pfizer, Daiichi Sankyo, Janssen Pharmaceutical, and Novartis outside the submitted work. MTam reported personal fees from Chugai Pharmaceutical, Boehringer Ingelheim, AstraZeneca, Taiho Pharmaceutical, Eli Lilly Japan, Pfizer, Ono Pharmaceutical, Amgen, MSD, BMS, and Takeda Pharmaceutical outside the submitted work. HKan reported grants to the institution from Chugai Pharmaceutical and Takeda Pharmaceutical, and honoraria from Chugai Pharmaceutical, AstraZeneca, and Daiichi Sankyo outside the submitted work. TToz reported honoraria from Chugai Pharmaceutical and AstraZeneca outside the submitted work. MF reported personal fees from AstraZeneca, Daiichi Sankyo, Chugai Pharmaceutical, and Nippon Kayaku outside the submitted work. SS reported personal fees from Takeda Pharmaceutical, AstraZeneca, and Taiho Pharmaceutical outside the submitted work. AM reported personal fees from Chugai Pharmaceutical, AstraZeneca, Ono Pharmaceutical, BMS, and Eli Lilly Japan outside the submitted work. HO reported grants and personal fees from Taiho Pharmaceutical and personal fees from Chugai Pharmaceutical, Ono Pharmaceutical, BMS, AstraZeneca, MSD, Daiichi Sankyo, and Eli Lilly Japan outside the submitted work. HKaw reported personal fees from BMS, Ono Pharmaceutical, Chugai Pharmaceutical, AstraZeneca, Taiho Pharmaceutical, Eli Lilly Japan, and MSD outside the submitted work. TN reported personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, Chugai Pharmaceutical, AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly Japan, Eisai, BMS, MSD, and Ono Pharmaceutical outside the submitted work. YN reported personal fees from Chugai Pharmaceutical and AstraZeneca outside the submitted work. KI reported personal fees from Takeda Pharmaceutical, Eli Lilly Japan, Chugai Pharmaceutical, Pfizer, Daiichi Sankyo, Nihon Kayaku, MSD, AstraZeneca, Ono Pharmaceutical, Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Novartis outside the submitted work. YTa reported honoraria from MSD, Chugai Pharmaceutical, AstraZeneca, Ono Pharmaceutical, and Boehringer Ingelheim outside the submitted work. TTok reported personal fees from Ono Pharmaceutical, Chugai Pharmaceutical, AstraZeneca, Novartis, MSD, BMS, Boehringer Ingelheim, Nippon Kayaku, and Taiho Pharmaceutical outside the submitted work. MI reported personal fees from AstraZeneca, and grants from Eli Lilly Japan outside the submitted work. HA reported personal fees from AstraZeneca, Chugai Pharmaceutical, Eli Lilly Japan, MSD, BMS, Ono Pharmaceutical, Takeda Pharmaceutical, Pfizer, Daiichi Sankyo, Merck Biopharma, and Nippon Kayaku outside the submitted work. YTs reported grants to the institution from Chugai Pharmaceutical and Eli Lilly Japan; honoraria from AstraZeneca, Taiho Pharmaceutical, Eli Lilly Japan, MSD, Eisai, Chugai Pharmaceutical, Daiichi Sankyo, BMS, and Boehringer Ingelheim; participation on an advisory board of AstraZeneca outside the submitted work. YK reported grants from MSD and personal fees from AstraZeneca, Chugai Pharmaceutical, MSD, Eli Lilly Japan, Ono Pharmaceutical, Taiho Pharmaceutical, and Takeda Pharmaceutical outside the submitted work. TM reported personal fees from Daiichi Sankyo, Taiho Pharmaceutical, Boehringer Ingelheim, Kyowa Kirin, Eli Lilly Japan, Ono Pharmaceutical, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Chugai Pharmaceutical, and AstraZeneca outside the submitted work. TSu reported personal fees from AstraZeneca and Boehringer Ingelheim outside the submitted work. All other authors report no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.jp) for English language editing.

Supplementary data

References

- 1.Koizumi T., Otsuki K., Tanaka Y., et al. National incidence and initial therapy for thymic carcinoma in Japan: based on analysis of hospital-based cancer registry data, 2009-2015. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2020;50(4):434–439. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyz203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cascone J., Ituarte B., Patel V., Mompoint A., Taylor M., Daon E. The contribution of rural/urban residence to incidence and survival in thymoma and thymic carcinoma, a retrospective cohort study of the SEER 2000-2020 database. Cancer Epidemiol. 2024;92 doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2024.102645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hsu C.-H., Chan J.K., Yin C.-H., Lee C.-C., Chern C.-U., Liao C.-I. Trends in the incidence of thymoma, thymic carcinoma, and thymic neuroendocrine tumor in the United States. PLoS One. 2019;14(12) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0227197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Girard N., Ruffini E., Marx A., Faivre-Finn C., Peters S. ESMO Guidelines Committee. Thymic epithelial tumours: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2015;26(suppl 5):v40–v55. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tsukita Y., Inoue A., Sugawara S., et al. Phase II study of S-1 in patients with previously-treated invasive thymoma and thymic carcinoma: North Japan lung cancer study group trial 1203. Lung Cancer. 2020;139:89–93. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2019.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Okuma Y., Goto Y., Ohyanagi F., et al. Phase II trial of S-1 treatment as palliative-intent chemotherapy for previously treated advanced thymic carcinoma. Cancer Med. 2020;9(20):7418–7427. doi: 10.1002/cam4.3385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gbolahan O.B., Porter R.F., Salter J.T., et al. A Phase II study of pemetrexed in patients with recurrent thymoma and thymic carcinoma. J Thorac Oncol. 2018;13(12):1940–1948. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2018.07.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hellyer J.A., Gubens M.A., Cunanan K.M., et al. Phase II trial of single agent amrubicin in patients with previously treated advanced thymic malignancies. Lung Cancer. 2019;137:71–75. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2019.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cho J., Kim H.S., Ku B.M., et al. Pembrolizumab for patients with refractory or relapsed thymic epithelial tumor: an open-label phase II trial. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(24):2162–2170. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.77.3184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Giaccone G., Kim C., Thompson J., et al. Pembrolizumab in patients with thymic carcinoma: a single-arm, single-centre, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19(3):347–355. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30062-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Katsuya Y., Horinouchi H., Seto T., et al. Single-arm, multicentre, phase II trial of nivolumab for unresectable or recurrent thymic carcinoma: PRIMER study. Eur J Cancer. 2019;113:78–86. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2019.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thomas A., Rajan A., Berman A., et al. Sunitinib in patients with chemotherapy-refractory thymoma and thymic carcinoma: an open-label phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(2):177–186. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)71181-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Proto C., Manglaviti S., Lo Russo G., et al. STYLE ( NCT03449173): a phase 2 trial of sunitinib in patients with type B3 thymoma or thymic carcinoma in second and further lines. J Thorac Oncol. 2023;18(8):1070–1081. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2023.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zucali P.A., De Pas T., Palmieri G., et al. Phase II study of everolimus in patients with thymoma and thymic carcinoma previously treated with cisplatin-based chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(4):342–349. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.74.4078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schlumberger M., Tahara M., Wirth L.J., et al. Lenvatinib versus placebo in radioiodine-refractory thyroid cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(7):621–630. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1406470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kudo M., Finn R.S., Qin S., et al. Lenvatinib versus sorafenib in first-line treatment of patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a randomised phase 3 non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2018;391(10126):1163–1173. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30207-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sato J., Satouchi M., Itoh S., et al. Lenvatinib in patients with advanced or metastatic thymic carcinoma (REMORA): a multicentre, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(6):843–850. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30162-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Niho S., Sato J., Satouchi M., et al. Long-term follow-up and exploratory analysis of lenvatinib in patients with metastatic or recurrent thymic carcinoma: results from the multicenter, phase 2 REMORA trial. Lung Cancer. 2024;191 doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2024.107557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Comprehensive Cancer Network Thymomas and Thymic Carcinomas (Version 1.2025) https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/thymic.pdf Available at. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Detterbeck F.C., Nicholson A.G., Kondo K., Van Schil P., Moran C. The Masaoka-Koga stage classification for thymic malignancies: clarification and definition of terms. J Thorac Oncol. 2011;6(7):S1710–S1716. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31821e8cff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marx A., Chan J.K.C., Chalabreysse L., et al. The 2021 WHO classification of tumors of the thymus and mediastinum: what is new in thymic epithelial, germ cell, and mesenchymal tumors? J Thorac Oncol. 2022;17(2):200–213. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2021.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.The Japan Lung Cancer Society . Kanehara & Co., Ltd.; 2024. Guidelines for Diagnosis and Treatment of Lung Cancer/Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma/Thymic Tumor 2024.https://www.haigan.gr.jp/modules/guideline/index.php?content_id=3 Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ramalingam S.S., Dahlberg S.E., Langer C.J., et al. Outcomes for elderly, advanced-stage non small-cell lung cancer patients treated with bevacizumab in combination with carboplatin and paclitaxel: analysis of Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Trial 4599. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(1):60–65. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Laskin J., Crinò L., Felip E., et al. Safety and efficacy of first-line bevacizumab plus chemotherapy in elderly patients with advanced or recurrent nonsquamous non-small cell lung cancer: safety of avastin in lung trial (MO19390) J Thorac Oncol. 2012;7(1):203–211. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3182370e02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wozniak A.J., Kosty M.P., Jahanzeb M., et al. Clinical outcomes in elderly patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer: results from ARIES, a bevacizumab observational cohort study. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2015;27(4):187–196. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2014.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Van Nguyen T., Hamdan D., Falgarone G., et al. Anti-angiogenic tyrosine kinase inhibitor-related toxicities among cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Target Oncol. 2024;19(4):533–545. doi: 10.1007/s11523-024-01067-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eisenhauer E.A., Therasse P., Bogaerts J., et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1) Eur J Cancer. 2009;45(2):228–247. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kanda Y. Investigation of the freely available easy-to-use software ‘EZR’ for medical statistics. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2013;48(3):452–458. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2012.244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Castelo-Branco L., Pellat A., Martins-Branco D., et al. ESMO Guidance for Reporting Oncology real-World evidence (GROW) Ann Oncol. 2023;34(12):1097–1112. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2023.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Remon Masip J., Bironzo P., Girard N., et al. LBA83 PECATI: a phase II trial to evaluate the efficacy and safety of lenvatinib in combination with pembrolizumab in pretreated advanced B3-thymoma and thymic carcinoma. Ann Oncol. 2024;35 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Takahashi S., Tahara M., Ito K., et al. Safety and effectiveness of lenvatinib in 594 patients with unresectable thyroid cancer in an all-case post-marketing observational study in Japan. Adv Ther. 2020;37(9):3850–3862. doi: 10.1007/s12325-020-01433-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brose M.S., Worden F.P., Newbold K.L., Guo M., Hurria A. Effect of age on the efficacy and safety of lenvatinib in radioiodine-refractory differentiated thyroid cancer in the phase III SELECT trial. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(23):2692–2699. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.71.6472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fukuda N., Toda K., Wang X., et al. Prognostic significance of 8 weeks’ relative dose intensity of lenvatinib in treatment of radioiodine-refractory differentiated thyroid cancer patients. Endocr J. 2021;68(6):639–647. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.EJ20-0754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kirino S., Tsuchiya K., Kurosaki M., et al. Relative dose intensity over the first four weeks of lenvatinib therapy is a factor of favorable response and overall survival in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. PLoS One. 2020;15(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0231828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Takahashi A., Moriguchi M., Seko Y., et al. Impact of relative dose intensity of early-phase lenvatinib treatment on therapeutic response in hepatocellular carcinoma. Anticancer Res. 2019;39(9):5149–5156. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.13710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sasaki R., Fukushima M., Haraguchi M., et al. Response to lenvatinib is associated with optimal relative dose intensity in hepatocellular carcinoma: experience in clinical settings. Cancers (Basel) 2019;11(11):1769. doi: 10.3390/cancers11111769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brose M.S., Panaseykin Y., Konda B., et al. A randomized study of lenvatinib 18 mg vs 24 mg in patients with radioiodine-refractory differentiated thyroid cancer. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2022;107(3):776–787. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgab731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Proto C., Ganzinelli M., Manglaviti S., et al. Efficacy and safety of ramucirumab plus carboplatin and paclitaxel in untreated metastatic thymic carcinoma: RELEVENT phase II trial ( NCT03921671) Ann Oncol. 2024;35(9):817–826. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2024.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shukuya T., Asao T., Goto Y., et al. Activity and safety of atezolizumab plus carboplatin and paclitaxel in patients with advanced or recurrent thymic carcinoma (MARBLE): a multicentre, single-arm, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2025;26(3):331–342. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(25)00001-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kato R., Hayashi H., Chiba Y., et al. Propensity score–weighted analysis of chemotherapy after PD-1 inhibitors versus chemotherapy alone in patients with non–small cell lung cancer (WJOG10217L) J Immunother Cancer. 2020;8(1) doi: 10.1136/jitc-2019-000350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sasaki A., Kawazoe A., Eto T., et al. Improved efficacy of taxanes and ramucirumab combination chemotherapy after exposure to anti-PD-1 therapy in advanced gastric cancer. ESMO Open. 2020;4(suppl 2) doi: 10.1136/esmoopen-2020-000775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.