Abstract

The main obstacles to the clinical application of the CRISPR/Cas9 system are off-target effects and low delivery efficiency. There is an urgent need to develop new delivery strategies and technologies. Three types of in situ injectable hydrogels with different electrical properties were created to find the most secure and efficient sustained-release drug delivery system. After in vitro and in vivo comparisons, we found that the positively charged hydrogels had higher cellular uptake, stronger gene editing efficiency, greater cytotoxicity, longer tumor accumulation, and better anti-tumor efficacy than negatively charged and neutral hydrogels. We designed single guide RNA targeting the Y-box binding protein 1 (YB-1) gene and then used it to create a ribonucleoprotein complex with Cas9 protein. Doxorubicin was co-encapsulated into this positively charged hydrogel to create a co-delivery system. By knocking down YB-1, the expression of YB-1 was reduced, inhibiting the growth and migration of melanoma cells. The strategy of combining YB-1 gene editing and intratumoral injection enhanced the therapeutic effect of doxorubicin while reducing side effects.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12951-025-03523-7.

Keywords: CRISPR/Cas9, Hydrogel, Polyamines, Intratumoral injection, YB-1

Introduction

Gene therapy represents an advanced technological approach that entails precise modifications of the genome sequence, enabling the induction of insertions, deletions, or base substitutions within the genetic material. This methodology employs nucleic acids, specifically DNA or RNA, for the purpose of treating, curing, or preventing human disorders [1]. Among the most prevalent third-generation gene-editing tools, clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR) associated with protein 9 (CRISPR/Cas9) holds a prominent position [2]. In contrast to Zinc-finger nucleases (ZFNs) and Transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALENs), the CRISPR/Cas9 system leverages short, complementary RNA strands termed single guide RNA (sgRNA) [3]. These sgRNA molecules recognize and bind to specific DNA sequences through Watson-Crick base pairing mechanisms [4], thereby guiding the Cas9 nuclease to execute site-specific DNA cleavage. This cleavage process is facilitated by two nickase domains within Cas9, namely RuvC and HNH [5]. A notable advantage of CRISPR/Cas9 over ZFNs and TALENs lies in its capacity for ‘multiplexing’, allowing for the simultaneous targeting of multiple DNA sites with more than one sgRNA [6]. This feature enhances the efficiency of gene editing and broadens the scope of applicability for gene-editing technologies [7]. However, a significant challenge associated with CRISPR/Cas9 is its propensity for cleaving regions of the genome that are similar to the intended target site, a phenomenon referred to as ‘off-target editing’ [8]. Off-target editing can result in DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) and indel mutations within critical genomic regions, potentially leading to detrimental alterations in gene function and even the development of tumors [9]. The resolution of the off-target issue holds the promise of establishing CRISPR/Cas9 as a potent therapeutic tool in the battle against cancer [10].

Recently, local drug delivery strategies have been studied by an increasing number of researchers, because local therapies can deliver 100% of the drug to the target site, improving therapeutic efficacy while reducing the off-target effects of therapeutic drugs [11]. Unlike systemic drug delivery, local drug delivery minimizes the side effects of drugs on normal organs while dramatically increasing drug concentration at the target site, such as tumors [12]. Traditional local drug delivery systems include microcapsules [13], microspheres [14], nanoparticles [15], liposomes [16], implants [17], and hydrogels [18]. The sustained-release system, an in situ injectable hydrogel, has the following advantages: (a) it is biocompatible and biodegradable, (b) it allows long-lasting drug accumulation at the tumor site, (c) it reduces the frequency of administration and improves patient compliance, (d) it exhibits low systemic toxicity [19].

Hydrogel is an ideal carrier for chemotherapy drugs. Qin reported a doxorubicin (DOX)-loaded self-healing hydrogel prepared with oxidised carboxymethyl cellulose, and the results showed that this hydrogel exhibited superior anti-tumor effects and reduced drug toxicity [20]. However, the utilization and mechanism of hydrogels for gene therapeutic agents delivery have not been thoroughly studied. The conventional approaches for delivering CRISPR/Cas9 systems are commonly classified into three categories: physical methods (such as electroporation and microinjection), viral vectors (including lentiviral, adenoviral, and adeno-associated virus (AAV) vectors), and non-viral techniques (encompassing plasmids, liposomes, polymeric nanoparticles, and extracellular vesicles) [21–23]. While viral vectors inherently possess the capacity to introduce genetic material into host cells, they are associated with immunogenicity and potential pathogenicity [24]. Liposomes, on the other hand, generally exhibit a safer profile compared to viral vectors but tend to be less efficient in terms of delivery [25]. Alternatively, hydrogels offer a promising delivery platform by facilitating the controlled release of CRISPR/Cas9 to the target site in a manner that is safer, more stable, and sustained, thereby enhancing the overall efficacy of the gene-editing system [26]. The transfection ability of different liposomes differs, and it has been reported that positively charged liposomes mediate more efficient gene therapy [27]. Therefore, we are intrigued by the effect of electrical properties on the transfection ability of hydrogels. To explore this correlation, we first chose Poloxamer 188 (P188) and Poloxamer 407 (P407) to prepare neutral hydrogels (Nuh) [28]. P188 and P407 are widely used to prepare thermosensitive hydrogels that encapsulate drugs at 0 °C and undergo gelation at 37 °C [29]. Negatively (Ngh) and positively charged hydrogels (Psh) were prepared by adding hyaluronic acid (HA) and polyamines (synthesized by us) to Nuh, respectively. In our research, we have demonstrated that Psh exhibit higher encapsulation ability and slower release behavior for CRISPR/Cas9 and DOX compared to Nuh and Ngh in vitro. We also constructed a melanoma mouse model to further validate the delivery effect of Psh and the editing ability of the CRISPR/Cas9 system in vivo.

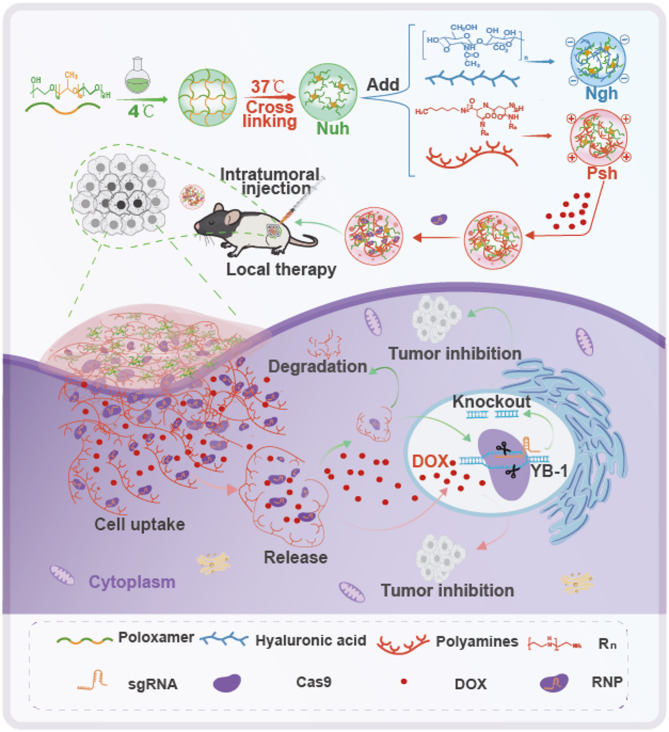

Malignant melanoma is an aggressive skin tumor with a high mortality rate and a high level of metastasis [30]. The recommended treatment for melanoma is surgical resection [31]. However, this approach has the drawbacks of partial and incomplete metastasis, especially as surgical resection becomes ineffective for metastatic melanoma [32]. Developments in immunotherapy and targeted molecular therapy have enabled novel approaches to treating melanoma [33, 34]. In situ hydrogels carrying injectable gene therapeutic agents are particularly well-suited for treating metastatic melanoma [35]. The CRISPR/Cas9 technology exhibits remarkable precision and permanence in targeting mutated genes [36], and it has been identified by Deng et al. as a gene therapy instrument for the treatment of melanoma. Their study introduced an efficient CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing framework, which utilized cationic copolymer aPBAE for delivery, to decrease programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression on tumor cells through the specific knockout of the Cyclin-dependent kinase 5 (Cdk5) gene in vivo. The findings demonstrated that the ablation of Cdk5 significantly diminished PD-L1 expression on melanoma cells, resulting in substantial inhibition of tumor growth in mouse models [37]. Additionally, Y-box binding protein 1 (YB-1) has been implicated as a pivotal factor in the growth, differentiation, and oncogenic transformation of melanoma cells [38]. Knocking down the YB-1 gene may inhibit the proliferation and differentiation of melanomas [39]. SgRNA is the key guide for Cas9 to achieve targeted cleavage of YB-1 [40]. Therefore, we designed three different sgRNAs for the YB-1 gene to explore the feasibility of YB-1 as a therapeutic target for melanoma. We investigated the most efficient sgRNA and the optimal molar ratio of sgRNA to Cas9 ribonucleoprotein complex (RNP). Cellular uptake, gene editing, and cytotoxicity of RNP-loaded hydrogels were compared to find the best formulation for gene therapy. The tumor accumulation, gene editing efficiency, and off-target side effects of the three types of hydrogels were studied in a melanoma mouse model through intratumoral injection. In addition, DOX [41], a traditional chemotherapeutic agent, was co-loaded into the hydrogels to enhance the therapeutic effect of the CRISPR/Cas9 system (Fig. 1). This work introduces a novel thermosensitive hydrogel for the simultaneous co-delivery of the CRISPR/Cas9 system and DOX, enabling both gene editing and synergistic chemotherapy. This combination offers a novel approach to treating recurrent and metastatic melanoma.

Fig. 1.

Schematic of the preparation, delivery, and intracellular fate of Psh@DOX@RNP

Methods and materials

Synthesis of polyamines

First, we add L-aspartic acid-4-N-carboxycyclic anhydride (NCA) (3.28 g, 13.2 mmol) and N, N-Dimethylformamide (DMF) (30 mL) to a round-bottomed flask equipped with a magnetic stirrer. The solution was stirred for 10 min at room temperature until NCA is completely dissolved. After adding hexylamine (17.4 µL, 0.132 mmol) dropwise, the reaction was carried out at room temperature for 48 h under the condition of nitrogen protection. Then, the reaction mixture was slowly poured into ultrapure water to precipitate poly (β-benzyl-L-aspartate) (PBLD). The filtered PBLD was washed, and freeze-dried to obtain pure white powder. Second, PBLD powder was added to the cold pentaethylenehexamine, and N-methylpyrrolidone (NMP) solution with stirring to dissolve it fully. Pentaethylenehexamine (50 equivalents) diluted with cold NMP was added to PBLD NMP solution dropwise at 0 °C and reacted for 2 h. The pH was adjusted to 1 by adding cold 6 N hydrogen chloride (HCl). The reaction solution was dialyzed in a regenerated cellulose membrane bag (Spectrum Laboratories, 1 kDa MWCO) with 0.01 N HCl and ultrapure water to obtain polyamine. Polyamine solution was freeze-dried to obtain pure white powder. The product of each step was confirmed by 1H-nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectra in dimethyl sulfoxide-d6 (DMSO-d6) using a AVANCE NEO 400 NMR spectrometer at 25 °C (Bruker, GER).

Preparation and characterization of hydrogels

To prepare Nuh, different amounts of P407 (20%, 20.8% and 24%, w/w) and P188 (1.2%, 2.5%, 5%, 3.46% and 5%, w/w) were weight to ultrapure water and place in a refrigerator at 4 °C to fully dissolve for 24 h. To prepare Psh, 0.1% polyamine was added into the Nuh. To prepare Ngh, we added 0.15% HA into Nuh. Measurements of zeta potential, gelation time, gelation temperature, injectability, and scanning electron microscope imaging were used to determine the appropriate hydrogel ratio. Agarose gel blocking was used to test the encapsulation ability of RNP by hydrogels with different electrical properties.

Cas9 protein and sgRNA were incubated at 37 °C for 10 min to prepare RNP. RNP and DOX were added to hydrogels at 4 °C and placed in the refrigerator at 4 °C for 2 h to obtain drug loaded hydrogels.

In vitro drug release kinetics

To track the protein drug-loaded hydrogel, we replaced RNP with fluorescein isothiocyanate labled bovine serum albumin (FITC-BSA). DOX loaded hydrogels with different electrical properties (Psh@DOX, Ngh@DOX, and Nuh@DOX), and FITC-BSA loaded hydrogels (Psh@FITC-BSA, Ngh@FITC-BSA, and Nuh@FITC-BSA) were prepared to investigate the kinetics of drug release from the hydrogel. DOX-loaded hydrogels were placed in dialysis bags (1000 Da), and FITC-BSA loaded hydrogel was gelatinized and packaged in gauze. Dialysis and gauze bags were put into brown jars containing 20 mL phosphate buffered saline (PBS). The in vitro release experiment was carried out in a shaker at 37 °C and 100 r/min. Two milliliters medium were took out at different time points (1 h, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 24, 36, and 48 h). Two milliliters fresh PBS were supplemented in to the medium. The concentrations of DOX and FITC-BSA dissolved in the samples at different time intervals were determined by the standard curve method. All steps were performed under light-protected conditions to prevent photodegradation of FITC-BSA and DOX. The Cumulative release rate (%) of each liposome sample was calculated according to Equation:

|

1 |

Note Cn: Drug concentration at time point n; Ci: Drug concentration of the sample i; A: The total amount of drug in the hydrogel.

Uptake efficiency in vitro

To visualize the distribution of drugs in cells under confocal microscopy, we replaced RNP with FITC-BSA and used red fluorescent dye cell membrane far-infrared fluorescent probe (DiD) instead of DOX. B16F10 were seeded to 6-well plates at the amount of 1 × 105 cells/well. When reached 70-80% confluent, cells were washed twice with PBS and added with 1 mL of Aq@DiD@FITC-BSA, Nuh@DiD@FITC-BSA, Ngh@DiD@FITC-BSA, or Psh@DiD@FITC-BSA respectively, at an equivalent concentration of 0.5 µg/mL DiD and 5µg/mL FITC-BSA. The gelled hydrogel was added to the plate, and 1 mL of serum-free DMEM cell culture medium (DMEM) was replenished to the cells. Commercial transfection reagent Lip2000® (Thermofisher, USA) was used as positive controls at its optimal conditions. After incubation for 6 h, cells were observed by LSM 980 with Airyscan 2 (ZEISS, GER) and flow cytometry (Becton, NJ, USA).

Cytotoxicity assay

The cytotoxicity of blank hydrogels, drug-loaded hydrogels toward B16F10 and 293T cells was evaluated using the 3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay. Specifically, B16F10 or 293T cells were seeded in 48-well plates at a density of 2 × 104 cells/well. After 24 h, 500 µL gel preparations (Psh, Aq@DOX@RNP, Psh@DOX, Psh@RNP, Psh@DOX@RNP) were added to the cells (dose of DOX, 0.1, 0.5, 1, 5, 10, 30, 50, 100 µg/mL. Cas9/sgRNA, 1:1, 1:2, 1:3, 1:4, 1:5.), and incubated at 37 °C for 10 min. Then, another 500 µL of medium was replenished. After incubation for 24 h, 20 µL of MTT solution was added to the medium followed by incubation for another 4 h. Finally, the medium was replaced with 150 µL of DMSO in each well to dissolve the formazan crystals (blue-violet). OD value of each sample was measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader with the blank culture medium as control. The cell inhibition rate (%) of each hydrogel sample was calculated according to Equation:

|

2 |

Note

ODs: Optical density (OD) of sample; ODc: OD of control; ODn: OD of normal.

GFP knockdown assay

293T cells with stable expression of green fluorescent protein (293T-GFP) were seeded at the amount of 1 × 105 cells/well in 6-well plates. When reached 70-80% confluent, cells were washed twice with PBS and add with 1 mL of Cas9 protein and sgGFP (sgRNA targeting GFP gene) ribonucleoprotein [RNP(GFP)] loaded Nuh [Nuh@RNP(GFP)], RNP(GFP) loaded Ngh [Ngh@RNP(GFP)], RNP(GFP) loaded Psh [Psh@RNP(GFP)], or RNP(GFP) loaded Lip2000 [Lip2000@RNP(GFP)] in a molar ratio of 1:3 for Cas9/sgGFP. The hydrogels were added to the plate, and 1 mL of serum-free DMEM was replenished to the wells. After incubation for 6 h, the drug containing DMEM was changed to fresh DMEM containing 2% fetal bovine serum (FBS). Cells were observed at the beginning, and 6, 12, 24 and 72 h after incubation by fluorescent inverted microscope. The exposure time of GFP (488 nm laser, 15% intensity) was set to 200 ms.

Wound-healing assay

The wound healing assay was used to study the effect of Psh@DOX@RNP on cell migration. B16F10 cells were seeded into 6-well plates at a density of 2 × 105 per well and incubated for 24 h. A 200 µL pipet tip was used to scratch across the wells with the tip kept vertical. The cells were washed with PBS and photographed before and after drug treating. Cells were incubated with blank Psh, Aq@DOX@RNP, Psh@DOX, Psh@RNP, Psh@DOX@RNP (dose of DOX, 2 µg/mL; Cas9, 6 µg/mL. Molar ratio of Cas9/sgRNA is 1:3) for 6 h, followed by DMEM (containing 2% FBS) culture. Different wells were photographed at 6, 24 and 72 h by fluorescent inverted microscope.

Apoptosis assay

Apoptosis assays were performed in B16F10 cells to confirm the efficiency of Psh@DOX@RNP by decreasing YB-1 protein expression. Briefly, cells were seeded in 6-well plates (2 × 105 cells/well). When the cells reached 70-80% confluent, we added 1 mL Aq@DOX@RNP, Psh@DOX, Psh@DOX@RNP (dose of DOX, 2 µg/mL; Cas9, 6 µg/mL. Molar ratio of Cas9/sgRNA is 1:3) to the 6-well plates. After incubating at 37 °C for 10 min, drug solution was substituted by 1mL of DEME containing 10% FBS, and cells were cultured for next 48 h. The cells were stained using the Annexin V-Fitc/PI Apoptosis Detection Kit and AM/PI Apoptosis Detection Kit, and analyzed by flow cytometry and fluorescent inverted microscope respectively.

Establishment of animal models

6–8 weeks old healthy male C57BL/6 mice were obtained from Hubei Provincial Center for Disease Control and Prevention (Wuhan, China). All animal protocols complied with institutional and local ethical regulations and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Hubei University (No. 20240012). This study complies with the ARRIVE guidelines. Melanoma mouse models were established by subcutaneous tumor implantation. First, we shaved the back of C57BL/6 male mice (6–8 weeks old), and 1 × 107 B16F10 cells were injected subcutaneously into the back of the right hind limb. Five days after injection, a black tumor with a diameter of 5 mm can be clearly observed under the skin of mice, which is considered as successful modeling.

Tumor targeting ability

To study the targeting and accumulation efficiency of hydrogels for chemotherapeutics and biomacromolecule in tumor, we prepared three kinds of hydrogels with different electrical properties that carry fluorescent substances. Therein, DOX was substituted by red fluorescent dye DiD, and Cas9 RNP was substituted by FITC-BSA. DiD and FITC-BSA solution (Aq@DiD@FITC-BSA) was set as control. Melanoma mouse models, with a tumor volume of ~ 100 mm3, were randomly divided into four groups to receive Aq@DiD@FITC-BSA, Nuh@DiD@FITC-BSA, Ngh@DiD@FITC-BSA, or Psh@DiD@FITC-BSA respectively via intratumoral injection (dose of DiD, 1 mg/kg; FITC-BSA, 2 mg/kg). Fluorescence intensity at the injection site on the dorsal skin of mice was measured using the Lumina III imaging system (PerkinElmer, MA, USA) at 0.5 h, 2 h, 6 h, 12 h, 4 days, and 8 days post-injection. Mice injected for 2 h and 24 h were euthanized by cervical dislocation and dissected to evaluate fluorescence intensity in organs (heart, liver, spleen, lung, kidney, skin). Subsequently, tumor tissues were fixed, frozen, sectioned, and stained with 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). Fluorescence distribution in tumor cells was observed using an inverted fluorescence microscope.

In vivo antitumor effects

B16F10 tumor-bearing C57BL/6 mice was established as described above for pharmacodynamic analysis. On day 8, mice were randomly divided into four groups and intratumoral injected three times with Aq@DOX@RNP, Psh@DOX and Psh@DOX@RNP (dose of sgRNA, 2 mg/kg; DOX, 5 mg/kg) every 5 days. Mice treated with PBS was used as control. Tumor dimensions and body mass were assessed on alternate days throughout the experiment. Subsequently, five days post the termination of the injection series, the mice underwent euthanasia, and blood samples were procured for standard hematological assessments. Primary organs were excised and preserved in a 4% formaldehyde solution to facilitate histological evaluations. For immunological assessments, monoclonal antibodies specific to Cas9, YB-1, P53, and Ki-67 (diluted to a ratio of 1:1000, sourced from ABclonal, Wuhan, China) were employed to detect the expression levels of these proteins, respectively. Additionally, the in vivo toxicity of the hydrogels was evaluated through hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining procedures. Genomic DNA and RNA were isolated from the tumor tissues. Following PCR amplification, the efficacy of Psh-mediated RNP delivery was further validated through T7 Endonuclease I (T7EI) assays and quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) experiments.

Statistical analysis

Difference between two groups was calculated by using student’s t-test. When the comparison was performed among three or more groups, one-way analysis of variance was performed. GraphPad Prism (Version5, GraphPad software, Inc.) was used. The p value was denoted by * for p < 0.05, ** for p < 0.01, *** for p < 0.001 and **** for p < 0.0001.

Results

Preparation of hydrogels with different electrical properties

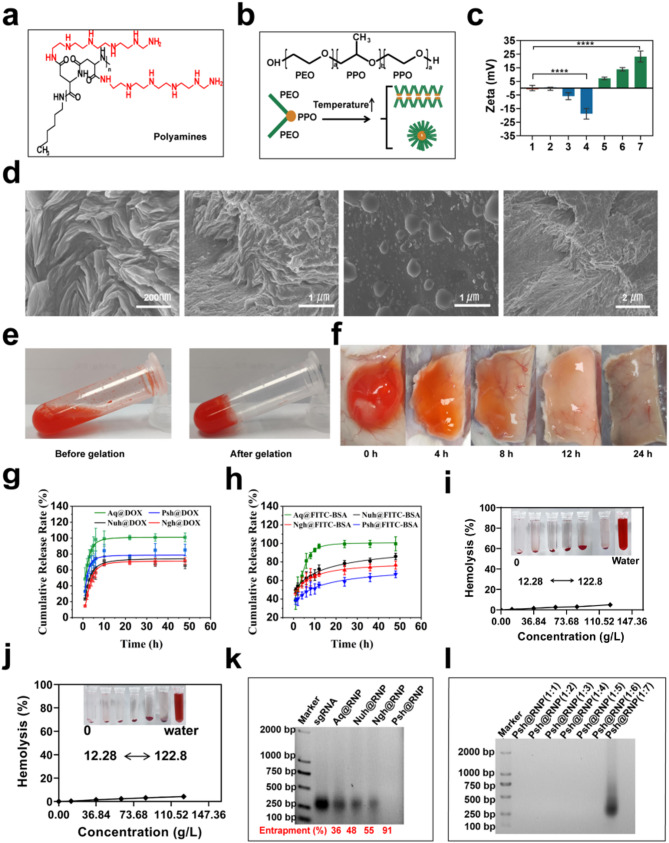

Polyamines (Fig. 2a) were synthesized using N-carboxyanhydride polymerization of L-benzyl aspartate (Fig. S1a), followed by amination of the side chain with N-amine substituents bearing pentaethylenehexamine repeats, as we described in methodology (Fig. S2a). Polyamines were characterized using 1H-NMR (Fig. S1b & S2b). P407 and P188 with a triblock structure (PE0-PPO-PEO) were used as the basic materials (Fig. 2b). Hydrogels with different ratios of P407 and P188 were prepared using the cold-solution method. Characterization of gelation time, gelation temperature and injectability of hydrogels of different hydrogels by syringe injection methods (Fig. S3). We found that aqueous solution with 20.81% of P407 and 3.46% of P188 was injectable and has the most suitable gelation time (40 s) at 37 °C to make Nuh (Table. S3) with a neutral zeta potential. Psh were prepared by adding 0.1% polyamines into Nuh to gain a positive zeta potential, and Ngh were prepared by adding 0.15% HA into Nuh to gain a negtive zeta potential (Fig. 2c). We also prepared drug-loaded hydrogels, including Psh@RNP, Psh@DOX, Psh@DOX@RNP, Nuh@RNP, Nuh@DOX, Nuh@DOX@RNP, Ngh@RNP, Ngh@DOX, and Ngh@DOX@RNP, to do the following experiments. The morphology of Psh was observed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM, Apreo 2, OPTON, Beijing). Typically, materials are ready for observation by the use of freeze-drying. Drying method is employed to prepare samples since this hydrogel must gelling at 37 °C. This leads to the loss of water molecules from the hydrogel, resulting in the collapse of its voids. Microscopic observations at various magnifications reveal that the dried hydrogel’s truncated surface exhibits abundant folds, suggesting that the hydrogel originally possessed a dense void structure before dehydration and that drug loading was achieved through pore adsorption. (Fig. 2d). When the temperature changed from 4 °C to 37 °C, Psh@DOX gelled from a fluid state into a solid state, shrinking to compress its pores and expel the encapsulated drug(Fig. 2e). We subcutaneously injected 100 µL Psh@DOX solution into mice, it was observed that the hydrogel gelled into a subspherical semisolid within 10 min under the skin of mice. Over time, the subcutaneous Psh@DOX gradually disappeared to the point where it was not observed (Fig. 2f). After we studied the in vitro release behavior of Psh@DOX and Psh@FITC-BSA (Fig. S4). Compared with DOX solution (Aq@DOX), DOX in Psh@DOX, Nuh@DOX, and Ngh@DOX released much slower and the release curves of the three groups were similar. Differently, 66.7% of FITC-BSA released from Psh@FITC-BSA after 48 h, while it was 85.9% for Nuh@DOX and 76.6% for Ngh@DOX (Fig. 2g&h). This phenomenon shows that Psh is suitable for the sustained release of protein drugs. Next, we performed hemolysis assay to study the toxicity of hydrogels. The result showed that the hemolysis of Psh, Nuh and Ngh was neglectable. Even at 122.85 g/L, the hemolysis of Psh is less than 5%, indicating that Psh was safe and can be used for subcutaneous injection (Fig. 2i&j & Fig. S5).

Fig. 2.

Preparation, characterization and comparison of three hydrogels. (a) Structures of polyamines utilized in the study. (b) Schematic representation of micelle formation by Poloxamer at elevated temperatures. (c) Zeta potential of different hydrogels. Column 1, Nuh; Column 2–4, Nuh@0.05%HA, Nuh@0.1%HA, Nuh@0.15%HA; Column 5–7, Nuh@0.05%PA, Nuh@0.1%PA, Nuh@0.15%PA. (d) SEM photographs of the Psh. (e) Psh@DOX is a fluxible liquid at 4 °C and a gel state at 37 °C. (f) Subcutaneous status of Psh@DOX at different time points. (g) In vitro release of Psh@DOX. (h) In vitro release of Psh@FITC-BSA. (i) Evaluation of haemolysis at different concentrations of Nuh. (j) Evaluation of haemolysis at different concentrations of Psh. (k) 2% agarose gel image of RNP-loaded hydrogel preparations. sgRNA was used to determine the encapsulation rate of RNP in hydrogels. (l) 2% agarose gel image of Psh@RNP. Data are presented as the mean ± s.d. (n = 3 biological replicates per group)

We synthesized Cas9 protein and sgRNA in our lab. First, we designed primers to construct pET-28a-Cas9-2NLS-6His recombinant plasmid (Table S1 & Fig. S6). The plasmid were transformed to E.coli BL21 (DE3) competent cells for Cas9 expression and purification (Fig. S7). Second, we designed three sgRNA targeting the YB-1 gene. Primers for the sgRNA sequences were shown in Supplementary Table 2. Three sgRNA sequences with the T7 promoter were obtained by RT-PCR and transcription (Table S2 & Fig. S8). Cas9 protein and sgRNA were incubated at 37 °C for 15 min to obtain RNP. The loading capacity of the three hydrogels was then investigated using gel retardation assay. Using free sgRNA as a reference, Fig. 2k demonstrates that Psh (91%) had the highest RNP loading capacity, which was 1.7 times higher than that of Ngh (55%), and 1.9 times higher than that of Nuh (48%). We further verified the effect of different molar ratios of RNP on the loading performance of Psh, and Fig. 2l showed that Psh can encapsulate RNP with molar ratios 1:1 to 1:6 (Cas9: sgRNA).

Cellular uptake efficiency and in vitro anti-tumor efficacy

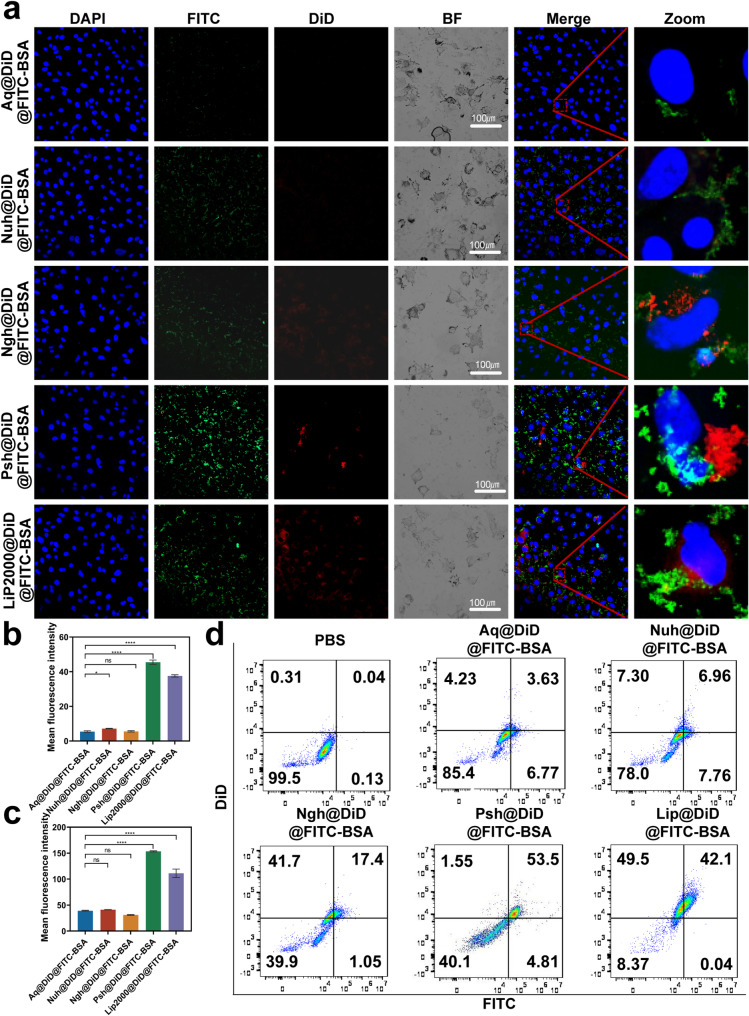

To examine the effect of the developed hydrogel on the cellular uptake of chemotherapeutics and macromolecular drugs, we prepared Aq@DiD@FITC-BSA, Nuh@DiD@FITC-BSA, Ngh@DiD@FITC-BSA, Psh@DiD@FITC-BSA and Lip2000@DiD@FITC-BSA and administrated to B16F10 cells. For visualization purposes, we used DiD instead of DOX and FITC-BSA instead of Cas9. The result of confocal microscopy (Fig. 3a-c) showed that the fluorescence intensity of cells treated with Psh@DiD@FITC-BSA was stronger than that of Aq@DiD@FITC-BSA, Nuh@DiD@FITC-BSA, and Ngh@DiD@FITC-BSA. The difference of fluorescence intensity between Psh@DiD@FITC-BSA and Lip2000@DiD@FITC-BSA was not significant. After 6 h incubation, the percentage of DiD and FITC-BSA positive cells in Psh@DiD@FITC-BSA treated group was 53.5% detected by flow cytometry, whereas it was 3.63% for Aq@DiD@FITC-BSA, 6.96% for Nuh@DiD@FITC-BSA, and 17.4% for Ngh@DiD@FITC-BSA (Fig. 3d). These results proved that Psh mediated high cellular uptake efficiency, and it was suitable as carriers for both DOX and RNP.

Fig. 3.

Cellular uptake of DiD and FITC mediated by three types of hydrogels. (a) Confocal microscope images of B16F10 cells after 6 h incubation with Aq@DiD@FITC-BSA, Nuh@DiD@FITC-BSA, Ngh@DiD@FITC-BSA, Psh@DiD@FITC-BSA and Lip2000@DiD@FITC-BSA. Cell nucleus was counterstained with 4,6-diamino-2-phenyl indole (DAPI) (blue). Quantitative analysis of (b) DiD and (c) FITC in B16F10 cells. (d) Endocytosis of Aq@DiD@FITC-BSA, Nuh@DiD@FITC-BSA, Ngh@DiD@FITC-BSA, Psh@DiD@FITC-BSA or Lip2000@DiD@FITC-BSA by B16F10 cells, detected by flow cytometry

The cytotoxicity of hydrogels was measured in B16F10 and 293T cells by MTT assay. B16F10 and 293T cells were incubated in Nuh, Ngh, and Psh. Cell viability remained stable (~ 85%) even after 72 h of incubation, demonstrating that the blank hydrogel carriers were non-toxic to B16F10 cells and exhibited high biocompatibility. (Fig. 4a&b). Using MTT tests, we further examined how drug-loaded hydrogels inhibited B16F10 cells. Results show that the Psh@DOX displayed much higher cytotoxicity against B16F10 cells with the lowest IC50 value (7.049 µM), which was 0.18-fold lower than that of Ngh@DOX (8.552 µM) and lower than Aq@DOX (10.63 µM) (Fig. 4c&d). To verify the optimal ratios of Cas9/sgRNA, Psh loaded with different molar ratios of RNP were prepared. It was demonstrated by MTT experiments that the inhibition rate of B16F10 increased gradually with the increase of the molar ratio of Cas9/sgRNA until the ratio reached 1:3. When the ratio reaches 1:4, the viability of the cell is instead enhanced, indicating that too high a proportion of sgRNA is instead detrimental to gene editing (Fig. 4e). Thus, we chose 1:3 to do the next experiments. The inhibition rates of blank Psh, Psh@DOX, Psh@Cas9, Psh@RNP, Aq@DOX@RNP, Psh@DOX@RNP(GFP), and Psh@DOX@RNP on B16F10 cells were compared. As shown in Fig. 4f, the cells incubated with Psh@DOX and Psh@RNP exhibited significant lower viability (53.87% and 65.92%) than incubated with blank Psh and Psh@Cas9 (89.92% and 87.72%), suggesting the antiproliferative capacity of Psh@DOX and Psh@RNP. Comparable to the Psh@DOX group (53.87%), the cell survival rate in the Psh@DOX@RNP(GFP) group (60.92%) was higher than that of the Psh@DOX@RNP group (33.28%). It indicated that RNP(GFP) had no evident B16F10 cells cytotoxicity compared to RNP. Psh@RNP suppressed YB-1 gene and prevented cell proliferation. Subsequently, the live-dead cell assay was performed to prove the high therapeutic efficacy of Psh@DOX@RNP (Fig. 4g). After 72 h treatment, the percentage of live B16F10 cells treated with Psh@DOX@RNP was 20.3%, prominently lower than those of PBS (96.8%), Aq@DOX@RNP (39.6%), and Psh@DOX (35.6%) (Fig. 4h).

Fig. 4.

Pharmaceutical effect of Psh@DOX@RNP on tumor cell B16F10 and non-tumor cell 293T. (a) The toxicity of Psh, Ngh and Nuh on 293T cells at different incubation time. (b) The toxicity of Psh, Ngh and Nuh on B16F10 cells at different incubation time. The viability of B16F10 cells after being treated by (c) free DOX; (d) Ngh@DOX, Nuh@DOX, Psh@DOX; (e) Psh, Psh@Cas9, Psh@RNP (Cas9/sgRNA at molar mass ratio of 1:1, 1:2, 1:3, 1:4, 1:5) and (f) Psh, Psh@DOX, Psh@Cas9, Psh@RNP, Aq@DOX@RNP, Psh@DOX@RNP(GFP), Psh@DOX@RNP. (g) Fluorescence microscopy images of PI (red) and calcein AM (green) cells after different treatments. (h) Apoptosis induced by various treatments to B16F10 cells using flow cytometry. Data are presented as the mean ± s.d. (n = 3 biological replicates per group)

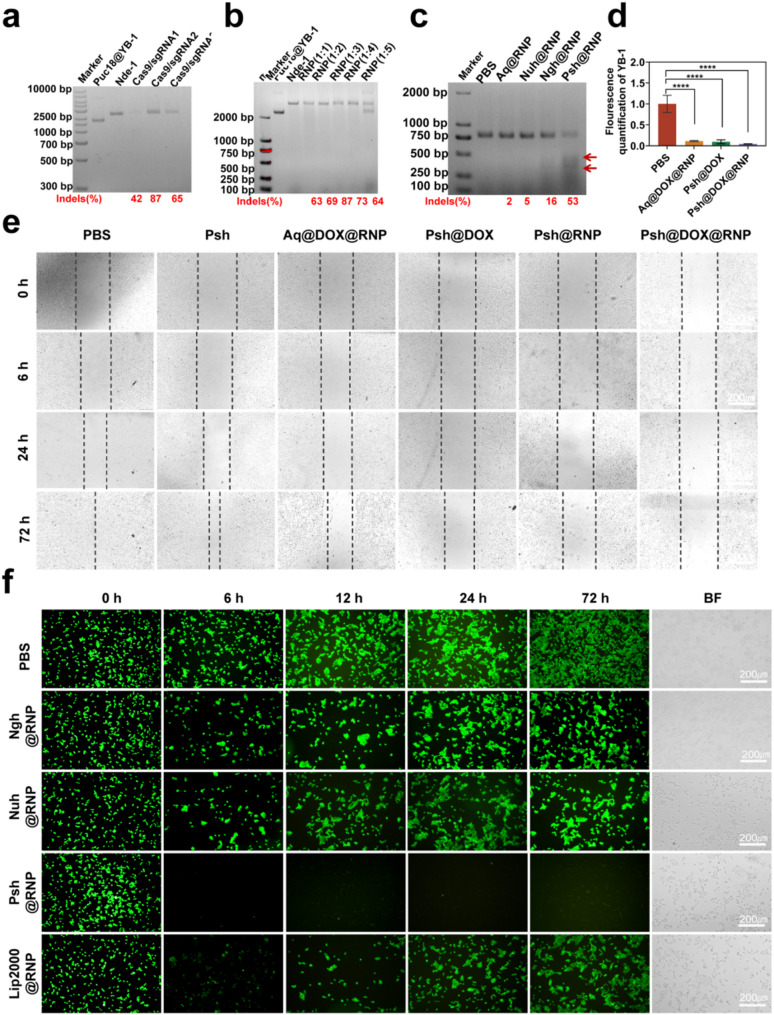

Effective genome editing by Psh@RNP

We constructed the PUC18-YB-1 plasmid by design correspondent primers (Table S1&Fig. S9), and the ability of RNP to cleave targeting genes in PUC18-YB-1 plasmid was verified in vitro to screen an optimal sgRNA sequence. As shown in Fig. 5a and Supplementary Fig. S10, all the three sgRNA had a certain endonuclease activity and targetedly edited the YB-1 gene. We chose sgRNA-2 to do the next experiments for its highest endonuclease activity. We also performed double-stranded nucleic acid cleavage assays and verified that Cas9/sgRNA of 1:3 was the optimal molar ratio (Fig. 5b). Following this, an assay utilizing T7EI was conducted to ascertain the efficacy of Psh@RNP-induced genomic insertions or deletions (indels). This endonuclease, which possesses the capability to identify and cleave mismatched DNA sequences, served as a tool to quantify the mutation frequency at the target locus. Specifically, after a 48-hour incubation period, Psh@RNP was observed to elicit double-strand breaks at predetermined genomic loci within B16F10 cells. Following Psh@RNP treatment, a 53% indels frequency could be reached in the targeted locus of YB-1, according to the cleavage bands and quantitative measurement of the intensity of the 2% agarose gel electrophoresis bands using imagej, while almost no mutation frequency could be seen in other groups (Fig. 5c). Q-PCR also proved the knockdown of the YB-1 gene (Fig. 5d).

Fig. 5.

In vitro gene editing efficiency of Psh@DOX@RNP. (a) Endonuclease activity of RNPs (composed of different sgRNAs) on PUC18@YB-1 plasmid in vitro. (b) Endonuclease activity of RNP (Cas9/sgRNA at molar mass ratio of 1:1, 1:2, 1:3, 1:4, 1:5) on PUC18@YB-1 plasmid in vitro. (c) T7EI assay of B16F10 cells treated with PBS, Aq@RNP, Nuh@RNP, Ngh@RNP and Psh@RNP. (d) The mRNA level of YB-1 was analysed by qRT-PCR. Data are presented as the mean ± s.d. (e) Representative images of the wound healing assays in B16F10 cells from 0 h to 72 h. (f) Fluorescence images of 293T-GFP cells treated with different preparations [PBS, Ngh@RNP(GFP), Nuh@RNP(GFP), Psh@RNP(GFP), Lip2000@RNP(GFP)]. (n = 3 biological replicates per group)

MT1-MMP gene promotes cancer cell metastasis, and relevant studies have shown that knockdown of the YB-1 gene is accompanied by a decrease in MTI-MMP expression, thereby inhibiting cancer cell migration. Here, we assessed the inhibitory effect of Psh@DOX@RNP by measuring the migration of B16F10 cell in vitro using the wound-healing assay. After 72 h incubation, PBS treated cells repopulated the injured area, and Psh, Aq@DOX@RNP, Psh@DOX, Psh@RNP, Psh@DOX@RNP treated cells were inhibited by about 20%, 50%, 70%, 80%, and 90% respectively (Fig. 5e). The Psh@DOX@RNP had strongest migratory inhibitory effect on B16F10 cells. This result further demonstrates that the YB-1 gene may have been knocked out.

Next, we determined the gene editing efficiency at the GFP gene locus of GFP-293T cell line containing a single copy of the reporter gene GFP and persistently expressing GFP protein. GFP-293T cell line was constructed, and the RNP system targeting the GFP gene was synthesized (Table S2). Gene editing efficiency was qualified using confocal microscopy and quantified using ImageJ software (Fig. 5f). Treatment with Psh@RNP(GFP) converted 67% of the GFP-positive cells to GFP-negative cells, while it was 14% for Ngh@RNP(GFP), 12% for Nuh@RNP(GFP), and 32% for Lipo2000@RNP(GFP), indicating high tumor cell uptake and efficient GFP knocked down by Psh. Collectively, the Psh@RNP could deliver both RNP(YB-1) and RNP(GFP) into B16F10 cells and GFP-293T cells with effective intracellular endo/lysosomal escaping and RNP unpacking, and finally achieved efficient gene editing in vitro.

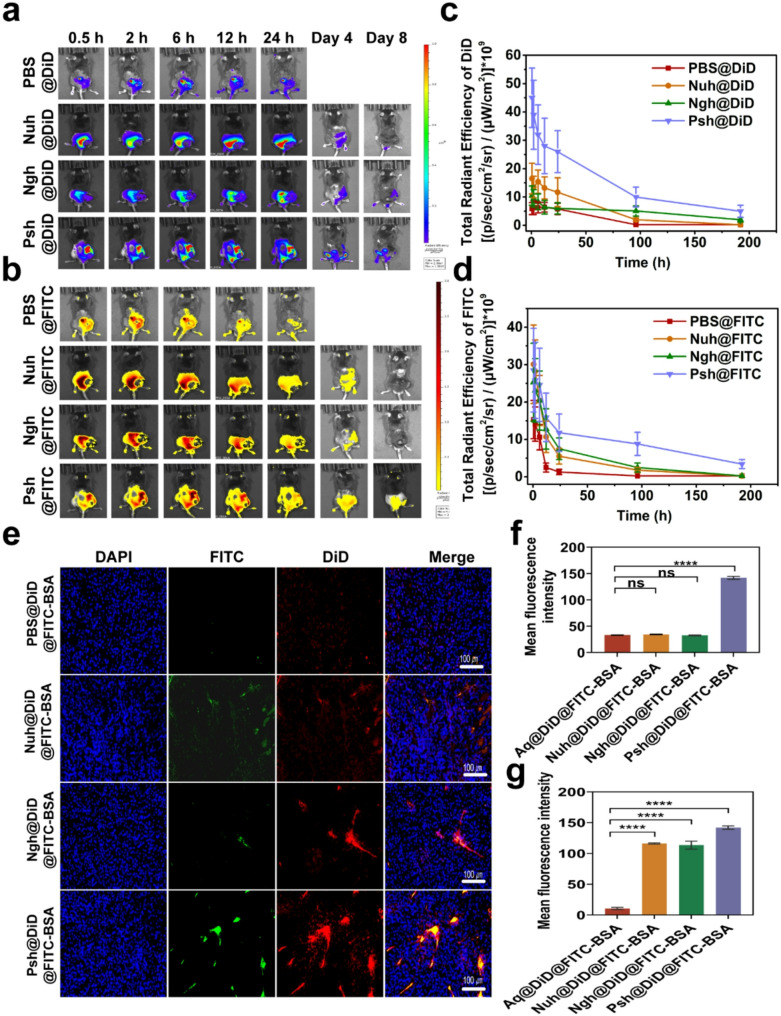

In vivo targeting ability

Hydrogels were loaded with near-infrared dye DiD and FITC-BSA to investigate the distribution of different hydrogels in melanoma-bearing mice. The DiD fluorescence were obtained by IVIS spectrum at different time points. As exhibited in Fig. 6a&b, after hydrogels were intratumorally administrated to mice, the fluorescence of DiD was found to be localized in the tumor area invariably. At 24 h post-injection, three hydrogel groups showed a stronger fluorescence intensity at the tumor site than a solution of free DiD and FITC-BSA, suggesting that hydrogels greatly facilitate the accumulation and slow release of biomolecules. DiD and FITC-BSA accumulation of three types of hydrogels in tumors remained high for 4 days. Eight days post administration, the fluorescence intensity decreased in hydrogel groups (Psh@DiD@FITC-BSA, Ngh@DiD@FITC-BSA, and Nuh@DiD@FITC-BSA) due to metabolism. However, the residual fluorescence intensity of the Psh@DiD@FITC-BSA group remained higher than that of Ngh@DiD@FITC-BSA and Nuh@DiD@FITC-BSA. Mice in the PBS group died after the fourth day of administration, thus no data are presented in Fig. 6c&d. After the IVIS spectrum observation, the mice were dissected and the tumor tissues were made into sections. As shown in Fig. 6e, much more DiD and FITC-BSA fluorescence signal existed in Psh@DiD@FITC-BSA treated group compared with that of Ngh@DiD@FITC-BSA, and Nuh@DiD@FITC-BSA, which further implied polyamides modification helped hydrogels to accumulate in tumor. DiD and FITC-BSA fluorescence intensity of sections was quantified by ImageJ (NIH, USA). As the statistics shown in Fig. 6f&g, DiD and FITC-BSA fluorescence intensity and proportion in Psh@DiD@FITC-BSA treated tumor were 4.3 times and 1.3 times higher than Ngh@DiD@FITC-BSA, 4.1 times and 1.2 times higher than Nuh@DiD@FITC-BSA, indicating that polyamides modification could help protein drug and small molecule drugs to accumulate in tumor. Since genome editing happened in DNA level, the permanent change would be brought once the editing was successful. So, local delivery of CRISPR/Cas9 RNP to tumor tissue is favorable. To investigate the in vivo distribution and safety of the hydrogel, IVIS spectral imaging was performed to capture the biodistribution of DiD and FITC-BSA in mouse organs at 2 h and 24 h post-injection (Fig. S11). Notably, no detectable fluorescence signals were observed in the organs, further confirming the biosafety of the hydrogel.

Fig. 6.

Sustained release and accumulation of RNP and DOX delivered by Psh in melanoma mouse models. In vivo fluorescence imaging of (a) DiD and (b) FITC in mice at different time points after intratumoral injection of PBS@DiD@FITC-BSA, Nuh@DiD@FITC-BSA, Ngh@DiD@FITC-BSA, or Psh@DiD@FITC-BSA. Quantification of (c) DiD and (d) FITC in mice by in vivo fluorescence imaging. (e) In vivo fluorescence images of isolated tumors from mice after 8 days injection. Cell nucleus was counterstained with DAPI (blue). (f, g) Quantitative analysis of drug accumulation in tumors. Data are presented as the mean ± s.d. (n = 3 biological replicates per group)

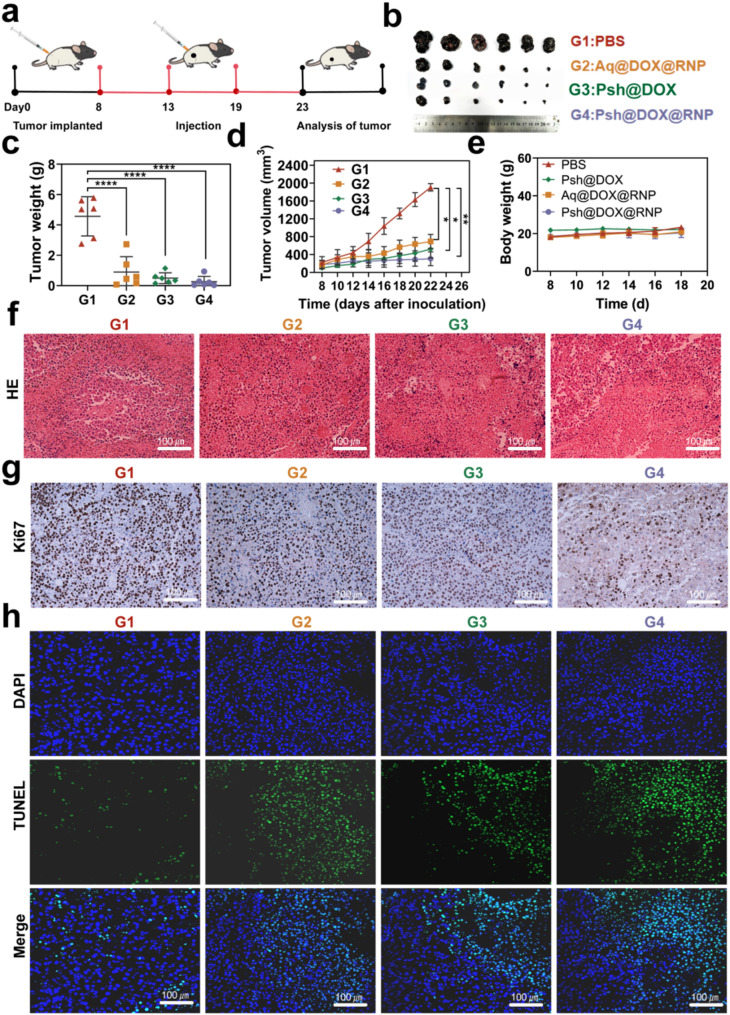

In vivo anti-tumor analysis

To evaluate in vivo anti-tumor effects, C57BL/6 melanoma model was established as described above, and tumor bearing mice were randomly divided into four groups. PBS, Psh@DOX@RNP, Aq@DOX@RNP, or Psh@DOX was intratumorally injected into B16F10 tumor bearing mice every 5 days, respectively. The treatment scheme was presented in Fig. 7a. Tumor was measured with vernier calipers to monitor tumor growth. As shown in Fig. 7b, the volume of mice treated with Psh@DOX@RNP, Aq@DOX@RNP, Psh@DOX were significantly smaller than PBS group, and the smallest average tumor in the Psh@DOX@RNP group. As shown in Fig. 7c&d, the group treated with Psh@DOX exhibited a rising pattern of tumor progression, attributable to the absence of in vivo YB-1 disruption. It is noteworthy that Psh@DOX@RNP demonstrated a substantial capacity to inhibit tumor deterioration in comparison to the PBS control. Specifically, the tumor growth inhibition rate achieved was approximately 98.4%. Furthermore, Psh@DOX@RNP exhibited superior tumor alleviation compared to Aq@DOX@RNP, owing to its higher accumulation and cellular internalization of DOX and RNP. This enhanced efficacy was facilitated by Psh, which contributed to improved nuclear targeting and accelerated formation of the genome editing complex. During the treatment period, body weight changes were also monitored. The body weight of tumor-bearing mice tended to be stable (Fig. 7e). This phenomenon suggested that it did not elicit systemic toxicity. The H&E staining of isolated tumors after 18 days treatment was shown in Fig. 7f. Obviously, comparing the Psh@DOX@RNP therapy group to the other groups, it is evident that their tumor necrosis area is significantly larger and exhibits the most nuclear shrinkage, fragmentation, and absence. The results confirmed that disrupting YB-1 significantly inhibited tumor proliferation. Notably, upon treatment with Psh@DOX@RNP, the fewest Ki67-positive tumor cells (stained brown) were observed in the tumor tissues, as compared to other groups (Fig. 7g). Additionally, the terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase - mediated deoxyuridine triphosphate nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay revealed that Psh@DOX@RNP treatment induced the most potent apoptotic effect in tumor tissues when compared to the other groups (Fig. 7h&Fig. S12). Collectively, these findings underscore the synergistic impact of DOX, RNP, and Psh on melanoma.

Fig. 7.

In vivo anti-tumor efficiency of Psh@DOX@RNP. (a) Treatment scheme. (b) Photographs of tumor dissected from C57BL/6 mice treated with PBS, Aq@DOX@RNP, Psh@DOX, or Psh@DOX@RNP. (c) Tumor weight of the mice. (d) Tumor growth curve of the mice after different treatments. (e) Body weight of C57BL/6 mice after treatment. (f) H&E stained sections and (g) Ki67 Immunohistochemical staining of isolated tumors. (h) TUNEL analysis in tumor sections after different treatments. Data are presented as the mean ± s.d. (n = 6 biological replicates per group)

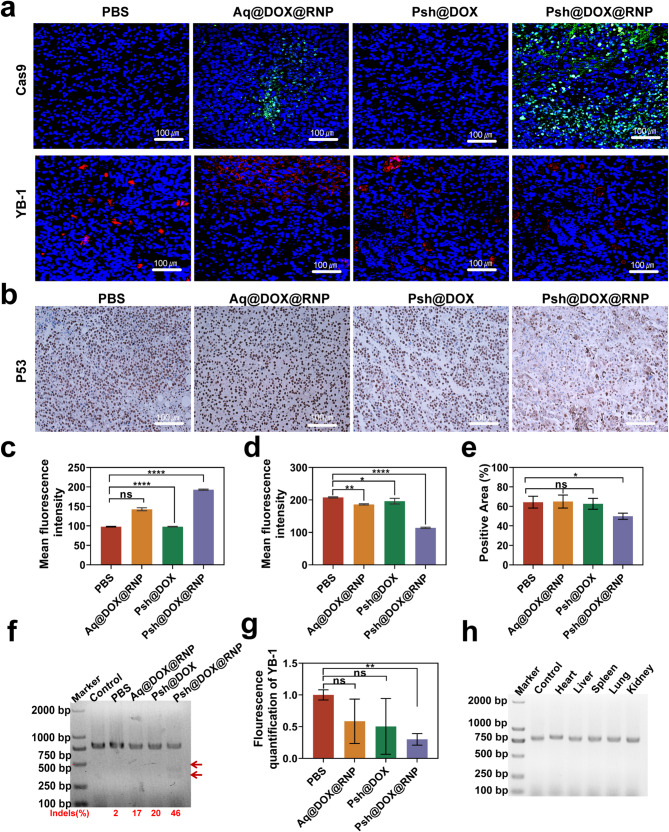

In vivo gene disruption analysis

We analyzed the tumor tissue by immunofluorescence and immunohistochemistry at the end of the treatment (Fig. 8a&b). The Cas9 accumulation in tumor tissues treated with Psh@DOX@RNP were about 1.4-fold higher than that of Aq@DOX@RNP (Fig. 8c). As shown in Fig. 8d, the YB-1 fluorescence intensity in the Psh@DOX@RNP group was 45% of the PBS group, indicating that Psh@DOX@RNP successfully delivered RNP into tumor cell and the YB-1 gene were knocked down by Psh@DOX@RNP. While losing its tumor-suppressive function, mutant p53 protein gains novel oncogenic activities through gain-of-function (GOF) mechanisms [42]. Therefore, we investigated the expression of P53 in tumor tissues using immunohistochemical analysis. We found that the Psh@DOX@RNP group had less P53 expression compared to the other three groups (Fig. 8e), which further demonstrated the potential of YB-1 as a therapeutic target for melanoma.

Fig. 8.

In vivo gene editing efficiency of Psh@DOX@RNP. (a) Immunofluorescence analysis of Cas9 (green), YB-1(red) expression. (b) Immunohistochemical analysis of P53 expression in tumor tissue sections. Quantitative analysis of (c) Cas9 protein and (d) YB-1 expression. (e) Quantitative analysis of the number of P53-positive cells. (f) T7EI assay of the isolated tumor tissue. (g) The mRNA of YB-1 in tumor tissues quantified by qRT-PCR. (h) T7EI assay of the isolated heart, liver, spleen, lung and kidney. Data are presented as the mean ± s.d. (n = 6 biological replicates per group)

To delve deeper into the mechanism underlying the potent tumor inhibitory capabilities of Psh@DOX@RNP, the in vivo efficacy of YB-1 gene disruption was further validated through the application of the T7EI assay. Consistent with the in vitro results, Psh@DOX@RNP treatment resulted in evident cleavage of YB-1 gene in the tumor tissue with a high gene mutation frequency of 46% (indels%), which was not observed in PBS, Aq@DOX@RNP, and Psh@DOX group (Fig. 8f). Q-PCR of tumor tissue further validated the down-regulation of YB-1 gene expression (Fig. 8g). The assessment of off-targeting editing, immunogenicity, and safety is paramount in CRISPR/Cas9 delivery systems, as these factors can potentially lead to vector clearance and therapeutic failure. Following the administration of Psh@DOX@RNP to mice, a T7EI assay was conducted on potential off-target sites in major organs, namely the heart, liver, spleen, lung, and kidney. As illustrated in Fig. 8h, no discernible cleavage bands were observed, suggesting that Psh@DOX@RNP did not elicit genome editing in these normal organs, thereby mitigating the risk of undesired off-target effects.

In vivo safety evaluation

As previously mentioned, the T7EI assay results on off-target locations in vital organs such the heart, liver, spleen, lung, and kidney of treated mice showed that the Psh@DOX@RNP therapy method was safe for biological systems (Fig. 8h). Moreover, a complete blood count (CBC) was performed on treated mice to investigate the safety of different treatments. As shown in Fig. S13, the administration of hydrogels had negligible effect on the number of blood cells. The H&E staining of isolated heart, liver, spleen, lung and kidney after 18 days treatment were shown in Fig. S14. No significant cellular infiltration was observed, demonstrating that this treatment modality has no significant toxic side effects on major organs. Considering the little off-target effect, high safety and low immunogenicity, Psh@DOX@RNP was suitable for in vivo application.

Discussion

Gene therapies represent promising avenues for inhibiting deregulated gene expression and hold considerable potential in overcoming severe human diseases [43]. Recently, the CRISPR/Cas9 system, a versatile, highly precise, potent, and straightforward genome editing tool, has emerged as an efficacious strategy for cancer treatment through the knockout of nuclear oncogenes [44]. However, the viral vectors typically employed in the CRISPR/Cas9 system are constrained by their limited packaging capacity, induction of unintended genetic mutations, immunogenicity, and oncogenic potential [45]. Consequently, non-viral vectors, particularly those based on nanoparticle delivery systems, have attracted substantial attention owing to their safety profile, fewer constraints in delivering substantial protein/gene/drug cargos, and their applicability in vivo [46]. It has been reported that positively charged liposomes are low in toxicity and capable of encapsulating the CRISPR/Cas9 system [47]. However, their targeting capability still requires improvement, and their accumulation at tumor sites is insufficient to achieve significant therapeutic efficacy. Polymer micelles have also been utilized to deliver hydrophobic drugs, but their poor stability and short release duration limit their applicability for long-term treatments. Both systems suffer from issues such as drug leakage and short local retention time [48]. In contrast, the cross-linked structure of hydrogels endows them with excellent physical stability, enabling them to maintain therapeutic concentrations over time, thus reducing dosing frequency and minimizing off-target effects. In this study, we developed a new thermosensitive hydrogel and compared the safety and efficacy of hydrogels with different electrical properties when delivering RNP. When the temperature changed from 4 °C to 37 °C, Psh, Nuh, and Ngh transformed from a fluid state to a solid state. The hemolysis of Psh, Nuh, and Ngh was negligible. By investigating the in vitro release behavior of Psh, Nuh, and Ngh, we found that, compared with DOX solution, DOX in the three types of hydrogels released much slower. The loading capacity of Psh was much higher than Nuh and Ngh. From the results of cellular uptake, we can see that the fluorescence intensity of cells treated with Psh@DiD@FITC-BSA was stronger than that of cells treated with Nuh@DiD@FITC-BSA and Ngh@DiD@FITC-BSA. The cytotoxicity and live-dead cell assay of the hydrogels was measured in B16F10 and 293T cells. As a result, the Psh@DOX@RNP displayed much higher cytotoxicity against B16F10 cells. These results proved that Psh mediated high cellular uptake efficiency, and it was suitable as carriers for both DOX and RNP.

Melanoma arises from melanocytes located in the skin, mucosa, and pigmented epithelia [49]. This malignancy is characterized by its high degree of aggressiveness, substantial mortality rates, unfavorable prognosis, and a propensity for metastasis [50]. Currently, surgical intervention remains the primary clinical approach for managing melanoma. However, these treatments are invasive, result in prolonged postoperative recovery, and exhibit a high recurrence rate in cases of metastatic melanoma. Beyond surgical excision, traditional modalities encompass radiotherapy [51] and chemotherapy [52], alongside emerging biological therapies [53], immunotherapy, and targeted therapies. Chemotherapy and radiotherapy face challenges in overcoming melanoma’s drug and radiation resistance, leading to poor patient survival rates. Furthermore, novel biotherapies and immunotherapies are associated with adverse events and limited therapeutic efficacy. Hence, there is a pressing need for additional therapeutic strategies for melanoma. For skin cancer, intratumoral drug delivery offers enhanced efficacy and specificity in targeting melanoma [54], optimizing therapeutic outcomes while minimizing adverse effects on patients. The integration of gene therapy into combination therapies has the potential to augment the effectiveness of conventional treatments [55]. Consequently, the implementation of combined gene therapy via intratumoral drug delivery emerges as a plausible strategy for the clinical management of melanoma. Direct injection of the RNP into the tumor maximizes its concentration at the tumor site and increases the effectiveness of gene editing while minimizing systemic responses and off-target consequences [41]. We observed the drug distribution in model mice using IVIS spectroscopy. The results showed that much more DiD and FITC-BSA fluorescence signals existed in the Psh@DiD@FITC-BSA treated group compared to the Ngh@DiD@FITC-BSA and Nuh@DiD@FITC-BSA groups, underscore the critical role of polyamine-induced positive surface charge. The positively charged surface of the hydrogel is easy to combine with the negatively charged tumor tissue, which improves the retention time of the drug in the lesion site and promotes clathrin-dependent endocytosis for intracellular drug accumulation. Furthermore, the delayed release of medications within Psh may extend the therapeutic effect. The T7EI assay was also conducted on normal organs, and there were no visible cleavage bands, indicating that Psh@DOX@RNP did not induce genome editing in normal major organs, thereby avoiding unwanted off-target effects. Furthermore, the administration of Psh@DOX@RNP had negligible effects on the number of blood cells. Given its minimal off-target effect, high safety, and low immunogenicity, the strategy of combining gene therapy with intratumoral injection holds great potential for clinical application in the treatment of metastatic melanoma.

Chemotherapy plays an important role in the clinical treatment of melanoma. Although the efficacy of chemotherapy is significant, the problem of drug resistance and the inability to eradicate tumors cannot be ignored. Gene therapy has the potential to completely cure diseases with genetic mutations, and its applications for diseases associated with single gene mutations have entered clinical trials [56]. However, the occurrence of tumors is accompanied by complex gene mutations, and gene therapy strategies targeting individual oncogenes may not guarantee anti-cancer effects [57]. For example, melanoma development is often associated with mutations in the YB-1 gene [58], the BRAF gene [59], and the NRAS gene [60]. YB-1 has been described as promoting metastasis in various cancer systems. It is involved in the malignant transformation of melanocytes and contributes to the stimulation of proliferation, tumor invasion, survival, and chemoresistance [38]. Thus, YB-1 is a promising molecular target in melanoma therapy. Recently, researchers have proposed a strategy of combining chemotherapy with gene therapy [61]. For example, Kang [62] developed an effective nanoplatform that can efficiently co-encapsulate DOX and nucleic acids (chol-miR21i) for cancer therapy. Overall, the effect of cancer treatment needs to be further improved. Based on the above considerations, we combined DOX-mediated chemotherapy with targeted YB-1 gene therapy to ensure the effectiveness of melanoma treatment. We synthesized Cas9 protein and sgRNA in our lab. We compared the efficiency of targeted cleavage of plasmid DNA containing the YB-1 gene and found the best sequences of sgRNA. T7EI, qPCR, immunohistochemistry, and immunofluorescence assays demonstrated that the combination of DOX and Cas9 RNP can efficiently accumulate in the tumor site, play a role in gene editing in model mice, and achieve knockdown of the YB-1 gene. The results of cytotoxicity examination, apoptosis, wound-healing and therapeutic effect showed that this combination was safe and had few side effects. We have further shown the potential of the triple combination of gene therapy, chemotherapy, and Psh in tumor suppression through this work.

Intratumoral injection utilizing Psh facilitated tumor-specific gene editing through the release of cytoplasmic Cas9/sgRNA complexes, yielding highly proficient gene editing outcomes. By editing the YB-1 gene, the sensitivity of tumors to DOX-induced cytotoxic therapy was significantly enhanced. Theoretically, the strategy incorporating Psh, chemotherapeutics, and Cas9 RNP complexes holds potential for application in combinatorial therapies targeting other diseases. Collectively, this multifunctional Psh exhibits several superior attributes compared to established vectors and shows promising potential for use in topical antitumor therapies. However, to advance further research and facilitate successful translation from laboratory to clinical practice, several limitations in this study need to be addressed. Firstly, the safety of gene editing requires further investigation. Secondly, to enhance clinical relevance, therapeutic efficacy should be validated in human melanoma cells, orthotopic or metastatic melanoma models in subsequent experiments. In summary, we have four conclusions from this study: (1) we showed that Psh was more effective at encapsulating and delivering CRISPR/Cas9 RNP; (2) we designed and synthesized single guide RNA targeting the YB-1 gene, and validated that the YB-1 gene was a preferred target for cancer therapy; (3) we combined chemotherapy, gene therapy, and thermo-sensitive hydrogel and proved the strategy’s potential for tumor suppression; (4) we utilized intratumoral injection to reduce the off-target effects of gene therapy while increasing the enrichment of therapeutic drugs in tumor tissue. Our gel formulation and delivery strategy show significant benefits in blocking melanoma and could offer novel approaches for other surface tumors of the body.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we formulated three thermosensitive, injectable hydrogels possessing distinct electrical properties. Both in vivo and in vitro experimental findings revealed that the Psh exhibited superior transfection efficiency and therapeutic efficacy against melanoma. Specifically, we employed Psh to deliver a YB-1-targeted CRISPR/Cas9 system along with doxorubicin (DOX), denoted as Psh@DOX@RNP, for effective gene editing and synergistic melanoma treatment. The Cas9 ribonucleoprotein (RNP) and DOX could be efficiently triggered for controlled release from Psh@DOX@RNP in a sustained manner. Notably, in vitro and in vivo studies demonstrated robust disruption of YB-1 following treatment with Psh@DOX@RNP, leading to significant suppression of YB-1 protein expression. Consequently, substantial inhibition of melanoma cell proliferation and remarkable attenuation of subcutaneous xenograft tumor growth were achieved. The thermosensitive hydrogel introduced in this study not only emerges as a promising non-viral vector for CRISPR/Cas9 system delivery but also expands the horizon for combining gene therapy and chemotherapy in cancer treatment strategies.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contributions

Meng Li: Writing - original draft, Visualization, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Songli Zhou: Writing - original draft, Investigation, Data curation. Suqin Zhang: Visualization, Formal analysis. Xingyu Xie: Investigation, Formal analysis. Junqi Nie: Resources. Qi Wang: Investigation. Lixin Ma: Writing - review & editing, Funding acquisition, Supervision. Yibin Cheng: Writing - review & editing, Supervision, Methodology. Jingwen Luo: Writing - review & editing, Supervision, Resources, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization.

Funding

This work was supported by the Hubei Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (2025AFB729), the Project of Technological Innovation Plan in Hubei Province (2024BCA001), and the Natural Science Foundation of Wuhan City (2024040701010046).

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All animal protocols adhered to institutional and local ethical regulations and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Hubei University (No.20240012, Hubei, China).

Consent for publication

All authors agree for publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Meng Li, Songli Zhou and Suqin Zhang contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Lixin Ma, Email: malixing@hubu.edu.cn.

Yibin Cheng, Email: chengyibin@hubu.edu.cn.

Jingwen Luo, Email: jwluo0227@163.com.

References

- 1.Brody H. Gene therapy. Nature. 2018;564:S5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kozovska Z, Rajcaniova S, Munteanu P, Dzacovska S, Demkova L. CRISPR: history and perspectives to the future. Biomed Pharmacother. 2021;141:111917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chuang CK, Lin WM. Points of view on the tools for genome/gene editing. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.van der Oost J, Patinios C. The genome editing revolution. Trends Biotechnol. 2023;41:396–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang J, Arantes PR, Ahsan M, Sinha S, Kyro GW, Maschietto F, Allen B, Skeens E, Lisi GP, Batista VS, Palermo G. Twisting and swiveling domain motions in Cas9 to recognize target DNA duplexes, make double-strand breaks, and release cleaved duplexes. Front Mol Biosci. 2022;9:1072733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lin M, Wang X. Natural Biopolymer-Based delivery of CRISPR/Cas9 for Cancer treatment. Pharmaceutics. 2023;16:62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ramadan M, Alariqi M, Ma Y, Li Y, Liu Z, Zhang R, Jin S, Min L, Zhang X. Efficient CRISPR/Cas9 mediated Pooled-sgRNAs assembly accelerates targeting multiple genes related to male sterility in cotton. Plant Methods. 2021;17:16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guo C, Ma X, Gao F, Guo Y. Off-target effects in CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2023;11:1143157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guo N, Liu JB, Li W, Ma YS, Fu D. The power and the promise of CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing for clinical application with gene therapy. J Adv Res. 2022;40:135–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen M, Mao A, Xu M, Weng Q, Mao J, Ji J. CRISPR-Cas9 for cancer therapy: opportunities and challenges. Cancer Lett. 2019;447:48–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ghaemi A, Bagheri E, Abnous K, Taghdisi SM, Ramezani M, Alibolandi M. CRISPR-cas9 genome editing delivery systems for targeted cancer therapy. Life Sci. 2021;267:118969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Antimisiaris SG, Marazioti A, Kannavou M, Natsaridis E, Gkartziou F, Kogkos G, Mourtas S. Overcoming barriers by local drug delivery with liposomes. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2021;174:53–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang J, Huang W, Chen Y, Zhang YS, Zhong J, Li Y, Zhou J. Eccentric magnetic microcapsules for MRI-guided local administration and pH-regulated drug release. RSC Adv. 2018;8:41956–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ji X, Shao H, Li X, Ullah MW, Luo G, Xu Z, Ma L, He X, Lei Z, Li Q, et al. Injectable immunomodulation-based porous Chitosan microspheres/hpch hydrogel composites as a controlled drug delivery system for osteochondral regeneration. Biomaterials. 2022;285:121530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim J, Seo BB, Hong KH, Kim SE, Kim YM, Song SC. Long-term anti-inflammatory effects of injectable celecoxib nanoparticle hydrogels for Achilles tendon regeneration. Acta Biomater. 2022;144:183–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shtenberg Y, Goldfeder M, Prinz H, Shainsky J, Ghantous Y, Abu El-Naaj I, Schroeder A, Bianco-Peled H. Mucoadhesive alginate pastes with embedded liposomes for local oral drug delivery. Int J Biol Macromol. 2018;111:62–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhao X, Deng M, Wang J, Liu B, Dong Y, Li Z. Miniaturized neural implants for localized and controllable drug delivery in the brain. J Mater Chem B. 2023;11:6249–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang Z, Ai S, Yang Z, Li X. Peptide-based supramolecular hydrogels for local drug delivery. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2021;174:482–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li G, Liu S, Chen Y, Zhao J, Xu H, Weng J, Yu F, Xiong A, Udduttula A, Wang D, et al. An injectable liposome-anchored teriparatide incorporated Gallic acid-grafted gelatin hydrogel for osteoarthritis treatment. Nat Commun. 2023;14:3159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yin L, Zhang K, Sun W, Zhang Y, Wang Y, Qin J. Carboxymethylcellulose based self-healing hydrogel with coupled DOX as camptothecin loading carrier for synergetic colon cancer treatment. Int J Biol Macromol. 2023;249:126012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ban W, Sun M, Huang H, Huang W, Pan S, Liu P, Li B, Cheng Z, He Z, Liu F, Sun J. Engineered bacterial outer membrane vesicles encapsulating oncolytic adenoviruses enhance the efficacy of cancer virotherapy by augmenting tumor cell autophagy. Nat Commun. 2023;14:2933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang X, Han T, Jiang X, Lin S, Lou X, Shi X, Cheng Z, He Z, Sun H, Liu F, Sun J, Sun M. Bimetallic nanodot-adenovirus chimera for cancer theranostics via cooperativity of autophagy and ferroptosis. Cell Rep Phys Sci. 2024;5:102221. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tan S, Yuan C, Zhu Y, Chang S, Li Q, Ding J, Gao X, Tian R, Han Z, Hu Z. Glutathione hybrid Poly (beta-amino ester)-plasmid nanoparticles for enhancing gene delivery and biosafety. J Adv Res. 2024;S2090–1232:00321–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rouatbi N, McGlynn T, Al-Jamal KT. Pre-clinical non-viral vectors exploited for in vivo CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing: an overview. Biomater Sci. 2022;10:3410–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rosenblum D, Gutkin A, Kedmi R, Ramishetti S, Veiga N, Jacobi AM, Schubert MS, Friedmann-Morvinski D, Cohen ZR, Behlke MA, et al. CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing using targeted lipid nanoparticles for cancer therapy. Sci Adv. 2020;6:eabc9450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cao H, Duan L, Zhang Y, Cao J, Zhang K. Current hydrogel advances in physicochemical and biological response-driven biomedical application diversity. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2021;6:426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Debele TA, Chen CK, Yu LY, Lo CL. Lipopolyplex-Mediated Co-Delivery of doxorubicin and FAK SiRNA to enhance therapeutic efficiency of treating colorectal Cancer. Pharmaceutics. 2023;15:596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Su R, Li P, Zhang Y, Lv Y, Wen F, Su W. Polydopamine/tannic acid/chitosan/poloxamer 407/188 thermosensitive hydrogel for antibacterial and wound healing. Carbohydr Polym. 2023;302:120349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hirun N, Kraisit P, Tantishaiyakul V. Thermosensitive polymer blend composed of poloxamer 407, poloxamer 188 and polycarbophil for the use as mucoadhesive in situ gel. Polym (Basel) 2022, 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Long GV, Swetter SM, Menzies AM, Gershenwald JE, Scolyer RA. Cutaneous melanoma. Lancet. 2023;402:485–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ahmed B, Qadir MI, Ghafoor S. Malignant melanoma: skin Cancer-Diagnosis, prevention, and treatment. Crit Rev Eukaryot Gene Expr. 2020;30:291–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Anguita R, Makuloluwa A, Bhalla M, Katta M, Sagoo MS, Charteris DG. Rhegmatogenous retinal detachment in choroidal melanoma: clinical features and surgical outcomes. Eye (Lond). 2024;38:494–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Catena X, Contreras-Alcalde M, Juan-Larrea N, Cerezo-Wallis D, Calvo TG, Mucientes C, Olmeda D, Suárez J, Oterino-Sogo S, Martínez L, Megías D, Sancho D, Tejedo C, Frago S, Dudziak D, Seretis A, Stoitzner P, Soengas MS. Systemic rewiring of dendritic cells by melanoma-secreted midkine impairs immune surveillance and response to immune checkpoint Blockade. Nat Cancer. 2025;6:682–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lou X, Chen Z, He Z, Sun M, Sun J. Bacteria-Mediated synergistic Cancer therapy: small Microbiome has a big hope. Nano-Micro Lett 2021 ,13:279–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Shukla A, Singh AP, Maiti P. Injectable hydrogels of newly designed brush biopolymers as sustained drug-delivery vehicle for melanoma treatment. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2021;6:63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Balon K, Sheriff A, Jacków J, Łaczmański Ł. Targeting Cancer with CRISPR/Cas9-Based therapy. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Deng H, Tan S, Gao X, Zou C, Xu C, Tu K, Song Q, Fan F, Huang W, Zhang Z. Cdk5 knocking out mediated by CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing for PD-L1 Attenuation and enhanced antitumor immunity. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2020;10:358–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tang L, Wei D, Xu X, Mao X, Mo D, Yan L, Xu W, Yan F. Long non-coding RNA MIR200CHG promotes breast cancer proliferation, invasion, and drug resistance by interacting with and stabilizing YB-1. NPJ Breast Cancer. 2021;7:94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lettau K, Khozooei S, Kosnopfel C, Zips D, Schittek B, Toulany M. Targeting the Y-box binding Protein-1 Axis to overcome radiochemotherapy resistance in solid tumors. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2021;111:1072–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dong C, Gou Y, Lian J. SgRNA engineering for improved genome editing and expanded functional assays. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2022;75:102697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang L, Pan H, Li Y, Li F, Huang X. Constructing Cu(7)S(4)@SiO(2)/DOX multifunctional nanoplatforms for synergistic Photothermal-Chemotherapy on melanoma tumors. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2020;8:579439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nakayama M, Hong CP, Oshima H, Sakai E, Kim SJ, Oshima M. Loss of wild-type p53 promotes mutant p53-driven metastasis through acquisition of survival and tumor-initiating properties. Nat Commun. 2020;11:2333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gene therapies should be for all. Nat Med 2021, 27:1311. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Wang SW, Gao C, Zheng YM, Yi L, Lu JC, Huang XY, Cai JB, Zhang PF, Cui YH, Ke AW. Current applications and future perspective of CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing in cancer. Mol Cancer. 2022;21:57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ahmadi SE, Soleymani M, Shahriyary F, Amirzargar MR, Ofoghi M, Fattahi MD, Safa M. Viral vectors and extracellular vesicles: innate delivery systems utilized in CRISPR/Cas-mediated cancer therapy. Cancer Gene Ther. 2023;30:936–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lin YQ, Feng KK, Lu JY, Le JQ, Li WL, Zhang BC, Li CL, Song XH, Tong LW, Shao JW. CRISPR/Cas9-based application for cancer therapy: challenges and solutions for non-viral delivery. J Control Release. 2023;361:727–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Syama K, Jakubek ZJ, Chen S, Zaifman J, Tam YYC, Zou S. Development of lipid nanoparticles and liposomes reference materials (II): cytotoxic profiles. Sci Rep. 2022;12:18071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Amreddy N, Babu A, Muralidharan R, Panneerselvam J, Srivastava A, Ahmed R, Mehta M, Munshi A, Ramesh R. Recent advances in Nanoparticle-Based Cancer drug and gene delivery. Adv Cancer Res. 2018;137:115–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Guo W, Wang H, Li C. Signal pathways of melanoma and targeted therapy. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2021;6:424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ugurel S, Gutzmer R. Melanom. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2023;21:343–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Thompson JF, Williams GJ, Hong AM. Radiation therapy for melanoma brain metastases: a systematic review. Radiol Oncol. 2022;56:267–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tasdogan A, Sullivan RJ, Katalinic A, et al. Cutaneous melanoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2025;23:11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Papież MA, Krzyściak W. Biological therapies in the treatment of Cancer-Update and new directions. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 54.Marques AC, Costa PJ, Velho S, Amaral MH. Stimuli-responsive hydrogels for intratumoral drug delivery. Drug Discov Today. 2021;26:2397–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Plana D, Palmer AC, Sorger PK. Independent drug action in combination therapy: implications for precision oncology. Cancer Discov. 2022;12:606–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nelson CE, Wu Y, Gemberling MP, Oliver ML, Waller MA, Bohning JD, Robinson-Hamm JN, Bulaklak K, Castellanos Rivera RM, Collier JH, Asokan A, Gersbach CA. Long-term evaluation of AAV-CRISPR genome editing for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Nat Med. 2019;25:427–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gao X, Dong D, Zhang C, Deng Y, Ding J, Niu S, Tan S, Sun L. Chitosan-Functionalized Poly(β-Amino Ester) hybrid system for gene delivery in vaginal mucosal epithelial cells. Pharmaceutics. 2024;16:154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kosnopfel C, Sinnberg T, Sauer B, Niessner H, Muenchow A, Fehrenbacher B, Schaller M, Mertens PR, Garbe C, Thakur BK, Schittek B. Tumour progression Stage-Dependent secretion of YB-1 stimulates melanoma cell migration and invasion. Cancers (Basel) 2020, 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 59.Killock D. DREAMseq of therapy for BRAF-mutant melanoma. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2023;20:1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Randic T, Kozar I, Margue C, Utikal J, Kreis S. NRAS mutant melanoma: towards better therapies. Cancer Treat Rev. 2021;99:102238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zou W, Huo B, Tu Y, Zhu Y, Hu Y, Li Q, Yu X, Liu B, Tang W, Tan S, Xiao H. Metabolic reprogramming by chemo-gene co-delivery nanoparticles for chemo-immunotherapy in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Acta Biomater. 2025;S1742–7061:00272–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhan Q, Yi K, Qi H, Li S, Li X, Wang Q, Wang Y, Liu C, Qiu M, Yuan X, et al. Engineering blood exosomes for tumor-targeting efficient gene/chemo combination therapy. Theranostics. 2020;10:7889–905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.