Abstract

Objectives:

Different ventilation devices, including double-lumen tube (DLT), video DLT (VDLT), and various bronchial blockers (BBs), were used for one-lung ventilation (OLV). This study aimed to assess the clinical characteristics of 12 OLV devices to identify the optimal ventilation strategy for different situations.

Methods:

PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, and the Cochrane Library were searched following the PICOS principle to retrieve relevant randomized controlled trials (RCTs) up to 18 November 2023. Network meta-analysis was conducted using R 4.3.2, StataSE15, and Review Manager 5.3 software to compare the clinical characteristics of these OLV devices, including the quality of lung collapse, malposition rate, time for device placement, the success of the first intubation attempt, postoperative sore throat, and hoarseness.

Results:

In summary, this study involved 33 RCTs with a total of 2177 patients to evaluate the clinical characteristics of 12 ventilation devices. Compared to the Arndt BB, DLT provided higher lung collapse quality and was less prone to malposition. According to the Ranking probabilities, the VDLT had a shorter placement time, while the Coopdech BB (CBB) had a higher success rate on the first intubation attempt. The Cohen Flex-Tip BB resulted in less hoarseness, and the CBB had a lower incidence of sore throat.

Conclusion:

DLT demonstrated reliable lung collapse quality. VDLT allowed for quicker placement and continuous airway monitoring. BBs had fewer complications and were easier to place but had a higher risk of malposition. Therefore, choosing an OLV device depends on the patient’s clinical status and surgical needs.

Keywords: airway management, Bayesian network meta-analysis, bronchial blocker, double lumen tube, one-lung ventilation, video double lumen tube

Introduction

Various ventilation devices, including the double-lumen tube (DLT), video DLT (VDLT), and bronchial blockers (BBs), are utilized for one-lung ventilation (OLV) management across different surgical procedures[1,2]. Among these, the DLT stands out as the most widely employed lung isolation technique in cardiac, pulmonary, and thoracic surgeries[3]. Under OLV conditions, one lung is collapsed to improve the surgical field. The lung isolation technique effectively separates the non-operative lung from the operative lung, thereby preventing the spread of lesions and minimizing the entry of residual tissue, blood, or purulent secretions from the operative lung into the non-operative one[4]. This helps in averting bronchial obstruction and secondary infections. However, complications such as poor lung collapse quality, placement difficulty, intraoperative malposition, and postoperative issues like sore throat and hoarseness may impact the quality of perioperative airway management[5,6].

HIGHLIGHTS

This study used Bayesian network meta-analysis to compare the clinical characteristics of 12 different one-lung ventilation (OLV) devices based on data from 33 randomized controlled trials.

Double-lumen tubes (DLTs) provided reliable lung collapse, video DLTs allowed for faster intubation and continuous intraoperative airway monitoring, while bronchial blockers were less invasive but carried a higher risk of displacement.

The selection of OLV devices should be determined by the specific surgical requirements and the patient’s clinical status.

To address the drawbacks of DLT, VDLT, and BBs have been improved in terms of convenience and safety. Recent randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have compared the convenience and safety of novel OLV devices with traditional DLT. VDLT can provide continuous airway monitoring, reducing the need for fiberoptic bronchoscopy (FOB) use, preventing tube displacement, and airway obstruction[7]. BB comes in various types and can be used with single-lumen tubes (SLT) or laryngeal mask airways (LMA) for OLV. This enhances convenience while reducing invasiveness to the airway, thereby expanding their application scope[8,9]. However, these trials are not comprehensive, as different models of BBs have their own advantages and disadvantages in clinical characteristics. VDLT was only compared with DLT and not with BBs. Differences in patient demographics, surgical sites, and procedural approaches pose varying demands on OLV. Without comprehensive comparisons, it poses a challenge to ascertain the most suitable lung isolation technique for different clinical scenarios.

Compared to traditional meta-analysis, network meta-analysis (NMA) allows for the simultaneous comparison of various clinical characteristics of different OLV devices through both direct and indirect comparisons[10,11]. Therefore, this study aims to evaluate the differences between various OLV devices through NMA, such as the quality of lung collapse, malposition rate, time for device placement, the success of the first intubation attempt, sore throat, and hoarseness. We hope to provide reliable clinical evidence for the selection of OLV devices.

Materials and methods

Study design

This NMA was conducted and reported following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) standard and Assessing the Methodological Quality of Systematic Reviews (Supplementary Tables S1 http://links.lww.com/JS9/E101 and S2 http://links.lww.com/JS9/E102)[12,13]. Additionally, the study has been registered in PROSPERO.

Search strategy

We searched for RCTs from the inception of the databases up to 18 November 2023, in PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane, and Web of Science. The selected articles were all published in English, and the search terms included: “One-Lung Ventilation,” “Single-Lung Ventilation,” “Lung Separation Technique,” “Bronchial blocker,” “Lung isolation device,” “Lung isolation technique,” “Endobronchial blocker,” “EZ-blocker,” “Fuji uniblocker,” “Coopdech blocker,” “Cohen Flex-Tip blocker,” “Arndt blocker,” “Wiruthan bronchial blockers,” “Double-Lumen tube,” “Double-lumen endobronchial tube,” “Double-lumen endotracheal tube,” “Video double-lumen tube,” “VivaSight double-Lumen tube,” “Intubation, Intratracheal,” “Endotracheal Intubation,” “Intratracheal Intubation,” “Endotracheal tube,” “Single-lumen tube,” “Single-lumen endotracheal tube,” “Laryngeal Mask,” “Laryngeal Mask Airway,” and “Supraglottic airway devices.” Medical subject headings, free-text terms, or their variations were used in the search strategy. Boolean operators “AND,” “OR,” and “NOT” were employed to connect search terms, forming the strategy expression (Supplementary Table S3, http://links.lww.com/JS9/E103).

Eligibility and inclusion criteria

Two independent researchers collected RCTs relevant to the research objectives following the PICOS principle. The characteristics of literature screening are as follows:

P (Patients): Patients requiring OLV during surgery.

I (Intervention): Different devices of OLV, including DLTs, VDLTs, BBs, and LMAs.

C (Comparison): Comparison between different devices of OLV.

O (Outcomes): Clinical characteristics of different ventilation devices, such as the quality of lung collapse (proportion of complete lung collapse), malposition rate (proportion of displacements detected by intraoperative bronchoscopy), time for device placement (time required for airway device placement (unit: seconds)), the success of the first intubation attempt (proportion of first-attempt intubation success), sore throat (proportion of postoperative sore throat occurrence), and hoarseness (proportion of postoperative hoarseness occurrence).

S (Study Design): RCTs.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Two researchers independently screened literature, extracted data, assessed the quality of the literature, and cross-checked the data. In case of discrepancies, they were resolved through discussion or consultation with a third party. The extracted data included: (1) Basic information of the included studies. (2) Baseline characteristics of the study subjects and interventions. (3) Key elements of bias risk assessment. (4) Outcome indicators of interest and measured outcome data (The time for device placement in each study was standardized to seconds and converted to the format: mean ± standard deviation)[14,15].

The risk of bias and quality assessment of RCTs were conducted using the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews, assisted by Review Manager software and the Cochrane GRADE tool. Details of the bias assessment reasons and quality assessment results can be found in Supplementary Tables S4 http://links.lww.com/JS9/E104 and S5 http://links.lww.com/JS9/E106.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis and graphical representation were performed using the R language (version 4.3.2) with packages “Gemtc” and “rjags,” Stata SE 15.0, and Review Manager 5.3 software. The specific NMA employed Bayesian models. Effect sizes for binary data (odds ratios, OR) and continuous data (mean differences, MD) were calculated, all reported with 95% confidence intervals (CI). A random-effects model was selected for data synthesis, with statistical significance set at P < 0.05. Node-splitting modeling was employed to evaluate the consistency of direct-indirect comparisons. Summary tables were produced to evaluate coherence (Supplementary Table S6, http://links.lww.com/JS9/E107).

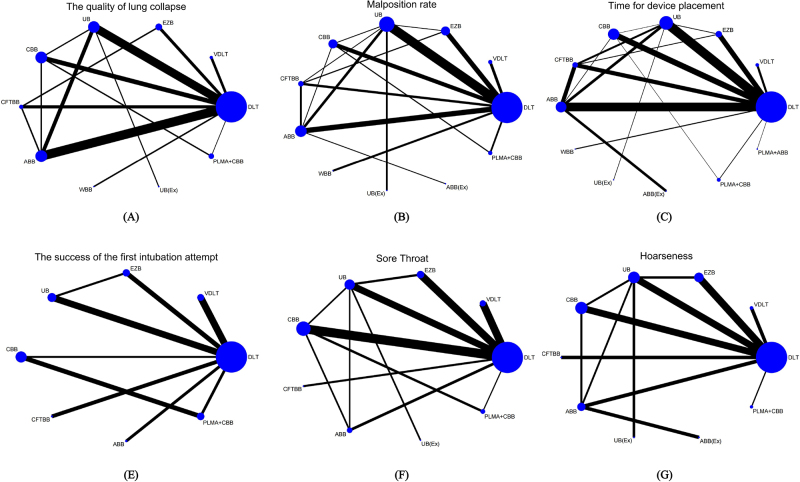

Evidence network diagrams were constructed for key outcome indicators, including the quality of lung collapse, malposition rate, time for device placement, success of the first intubation attempt, sore throat, and hoarseness. Each node in the evidence network diagram represented a specific intervention method, with node size reflecting the number of patients receiving the intervention. Nodes were connected by lines indicating direct intervention relationships, with line thickness representing the quantity of direct evidence.

Comparison-adjusted funnel plots were generated to detect publication bias. Furthermore, the results of the NMA were ranked based on the surface under the cumulative ranking (SUCRA) curve, providing insights into the efficacy of each intervention. Lower SUCRA values indicated lower probabilities of outcome indicators.

The NMA results of the six outcome indicators were grouped pairwise (Efficacy: the quality of lung collapse and malposition rate; Convenience: time for device placement and the success of the first intubation attempt; Safety: sore throat and hoarseness) to create a two-dimensional plot, aiming to analyze the most optimal ventilation devices under different clinical characteristics.

Result

Basic characteristics and risk of bias

After searching four databases, we initially found 4269 relevant articles. After deduplication, 1674 duplicate articles were removed. Following a preliminary review of titles and abstracts, 2555 articles were excluded due to apparent irrelevance to the topic. Subsequently, the remaining 40 articles underwent full-text assessment. Among these, one article focused on pediatric subjects, four articles were non-RCTs, and two articles had outcome measures that did not meet the inclusion criteria, resulting in a total of seven articles being excluded. Finally, we included 33 randomized RCTs for analysis (Table 1)[7-9,16-45]. The literature search process is illustrated in Fig. 1. Additionally, The risk of bias graph and risk of bias summary are shown in Figures S1 and S2 (http://links.lww.com/JS9/E110). Our analysis involved 2177 patients and 12 ventilation devices, which are: Double lumen tube (DLT); Video double lumen tube (VDLT); EZ blocker (EZB); Fuji Uniblocker (UB); Coopdech bronchial blocker (CBB); Cohen Flex-Tip bronchial blocker (CFTBB); Arndt bronchial blocker (ABB); Wiruthan bronchial blocker (WBB); Fuji Uniblocker-Extraluminal Placement (UB(Ex)); Arndt bronchial blocker-Extraluminal Placement (ABB(Ex)); ProSeal laryngeal mask airway + Coopdech bronchial blocker (PLMA + CBB) and ProSeal laryngeal mask airway + Arndt bronchial blocker (PLMA + ABB).

Table 1.

Study characteristics

| Study number | Author, year (country) | Research type | Type of surgery | Procedures of surgery | Sex (female/total) | Age (year) | BMI (kg/cm2) | Ventilation devices | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Shum, et al, 2023 (Canada) | A prospective, randomized clinical controlled trial | Elective thoracic surgery | Wedge | (16/30)/(16/30) vs (18/29) | (63.8 ± 10.4)/(61.4 ± 12.5) vs (62.6 ± 12.5) | (27.6 ± 5.0)/(25.7 ± 3.7) vs (27.0 ± 5.2) | (EZ blocker)/(Fuji Uniblocker) vs (Double lumen tube) | ②③④⑤⑥ |

| Lobectomy | |||||||||

| Bilobectomy | |||||||||

| Wedge + lobectomy | |||||||||

| Segmentectomy | |||||||||

| Mediastinal tumor | |||||||||

| 2 | Nakanishi, et al, 2023 (Japan) | A single-center, patient-assessor blinded, randomized controlled trial | Elective thoracic surgery | Lobectomy | (23/49) vs (24/49) | (67 ± 11) vs (64 ± 13) | (22.8 ± 6) vs (22.9 ± 5) | (ProSeal laryngeal mask airway + Coopdech bronchial blocker) vs (Double lumen tube) | ①②③④⑤⑥ |

| Segmentectomy | |||||||||

| Partial resection | |||||||||

| 3 | Risse, et al, 2022 (German) | A randomised, controlled trial | Elective thoracic surgery | - | (13/36) vs (13/38) | (65.1 ± 10.0) vs (64.4 ± 14.6) | (25.0 ± 5.5) vs (26.4 ± 4.8) | (EZ blocker) vs (Double lumen tube) | ①②③④⑤⑥ |

| 4 | Palaczynski, et al, 2022 (Poland) | A randomized, prospective study | Elective thoracic surgery | Lobectomy | (9/32) vs (18/39) | (63 ± 14) vs (60 ± 17) | (26.3 ± 6.2) vs (26.9 ± 4.6) | (Video double lumen tube) vs (Double lumen tube) | ①②③④⑤⑥ |

| Bilobectomy | |||||||||

| Wedge lung resection | |||||||||

| Other | |||||||||

| 5 | Xu et al, 2021 (China) | A single centered prospective assessor-blinded randomized controlled trial | Elective esophageal cancer surgery | Esophageal procedure | (13/30) vs (14/30) | (59.1 ± 4.7) vs (52.6 ± 12) | (23.1 ± 2.2) vs (21.6 ± 2.1) | (Fuji Uniblocker) vs (Double lumen tube) | ①②③④⑤⑥ |

| 6 | Morris, et al, 2021 (USA) | A prospective, randomized controlled trial | Elective thoracic surgery | Robotic thoracoscopic procedure | (20/41) vs (15/40) | (62.1 ± 10.5) vs (66.2 ± 12.9) | (27.8 ± 4.8) vs (28.3 ± 4.8) | (EZ blocker) vs (Double lumen tube) | ②③ |

| 7 | Zhang, et al, 2020 (China) | A single center, randomized, double-blind study | Elective esophageal cancer surgery | Video-assisted thoracoscopic laparoscopic | (8/27) vs (8/28) | (61.6 ± 8.1) vs (62.3 ± 8.2) | (22.5 ± 2.3) vs (22.3 ± 2.9) | (Coopdech bronchial blocker) vs (Double lumen tube) | ①②③⑤ |

| Left neck anastomosis | |||||||||

| 8 | Liu, et al, 2020 (China) | A randomised, controlled trial | Elective thoracic surgery | Lung surgery | (16/30) vs (13/30) | (56.5 ± 14.5) vs (55.5 ± 11.3) | (21.8 ± 2.9) vs (23.6 ± 4.2) | (Fuji Uniblocker) vs (Double lumen tube) | ②③④⑤ |

| Esophageal surgery | |||||||||

| Mediastinal mass surgery | |||||||||

| 9 | Cheng, et al, 2020 (China) | A prospective randomized, controlled trial | Elective thoracic surgery | Segmentectomy | (12/37) vs (12/38) | (53.2 ± 9.1) vs (51.1 ± 7.3) | (23.4 ± 4.3) vs (24.2 ± 3.1) | (Coopdech bronchial blocker) vs (Double lumen tube) | ①②③⑤ |

| Lobectomy | |||||||||

| 10 | Zheng, et al, 2019 (China) | A randomized controlled trail | Elective thoracic surgery | Thoracic-approach debridement combined with thoracic posterior internal fixation | (48/100) vs (50/100) | (46.3 ± 5.7) vs (45.6 ± 5.3) | - | (Coopdech bronchial blocker) vs (Double lumen tube) | ③④⑤⑥ |

| 11 | Shanban, et al, 2019 (Egypt) | A randomized comparative study | Elective thoracic surgery | Lobectomy | (8/20) vs (13/20) | (42.4 ± 8.5) vs (41.7 ± 9.3) | (27.3 ± 5.6) vs (26.7 ± 6.8) | (Cohen Flex-Tip bronchial blocker) vs (Double lumen tube) | ①③④⑤⑥ |

| Lung biopsy | |||||||||

| Segmentectomy | |||||||||

| 12 | Lu, et al, 2018 (China) | A randomized controlled trail | Elective thoracic surgery | Esophageal tumor | (6/19) vs (5/21) | (68 ± 9) vs (66 ± 6) | (22 ± 2) vs (23 ± 3) | (Coopdech bronchial blocker) vs (Double lumen tube) | ①②③⑤⑥ |

| 13 | Heir, et al, 2018 (USA) | A randomized controlled Study. | Elective thoracic surgery | Esophageal | (-/38) vs (-/42) | (-) vs (-) | - | (Video double lumen tube) vs (Double lumen tube) | ②⑤ |

| Lung | |||||||||

| Other | |||||||||

| 14 | Templeton, et al, 2017 (USA) | A prospective, randomized, controlled trial | Elective thoracic surgery | Open thoracotomy | (-/21) vs (-/20) | (61 ± 16.6) vs (64 ± 10.1) | (26.5 ± 4.3) vs (28.3 ± 3.8) | (Arndt bronchial blocker-Extraluminal Placement) vs (Arndt bronchial blocker) | ②③⑥ |

| Video assisted thoracoscopic surgery | |||||||||

| 15 | Liu, et al, 2017 (China) | A randomized controlled trail | Elective thoracic surgery | - | (8/20) vs (10/20) | (52.8 ± 12.5) vs (55.3 ± 13.6) | (24.8 ± 2.0) vs (23.7 ± 1.7) | (Fuji Uniblocker-Extraluminal Placement) vs (Fuji Uniblocker) | ①②③⑤⑥ |

| 16 | Bussieres, et al, 2016 (Canada) | A randomized controlled trial | Elective thoracic surgery | Lung resection | (10/18) vs (11/20) | (62.0 ± 8) vs (63 ± 11) | (28.3 ± 5.1) vs (27.9 ± 6.1) | (Fuji Uniblocker) vs (Double lumen tube) | ① |

| 17 | Schuepbach, et al, 2015 (Switzerland) | A randomized controlled trial | Elective thoracic surgery | Lung resection | (11/19) vs (10/20) | (57 ± 17) vs (63 ± 10) | (23 ± 4) vs (24 ± 3) | (Video double lumen tube) vs (Double lumen tube) | ①②③④⑤⑥ |

| 18 | Levy-Faber, et al, 2015 (Israel) | A prospective randomized controlled study | Elective thoracic surgery | Lung lobectomy | (14/35) vs (18/36) | (67.6 ± 10.1) vs (67.7 ± 10.8) | - | (Video double lumen tube) vs (Double lumen tube) | ③④⑤ |

| 19 | Young Yoo, et al, 2014 (Korea) | A prospective, randomized, blind trial | Elective thoracic surgery | Wedge resection | (1/34) vs (1/18) | (17.9 ± 2.3) vs (20.8 ± 7) | - | (Fuji Uniblocker) vs (Double lumen tube) | ②③ |

| 20 | Wang, et al, 2014 (China) | A prospective, randomized study | Elective thoracic surgery | Pulmonary bulla excision | (15/50) vs (14/50) | (43.2 ± 14.7) vs (45.4 ± 11.8) | - | (ProSeal laryngeal mask airway + Coopdech bronchial blocker) vs (Coopdech bronchial blocker) | ①②③④⑤ |

| Pulmonary lobectomy | |||||||||

| Biopsy | |||||||||

| Mediastinal mass excision | |||||||||

| 21 | Li, et al, 2014 (China) | A randomized controlled trial | Elective thoracic surgery | Wedge resection | (8/26) vs (12/29) | (55 ± 15) vs (57 ± 13) | (22.5 ± 4.1) vs (22.9 ± 3.7) | (ProSeal laryngeal mask airway + Arndt bronchial blocker) vs (Double lumen tube) | ③ |

| Lobectomy | |||||||||

| Segmentectomy | |||||||||

| Pneumonectomy | |||||||||

| Mediastinal mass resection | |||||||||

| Esophageal procedures | |||||||||

| 22 | Kus, et al, 2014 (Turkey) | A prospective, randomized study | Elective thoracic surgery | Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery | (7/20) vs (6/20) | (48 ± 12) vs (46 ± 14) | (24 ± 2) vs (25 ± 3) | (Cohen Flex-Tip bronchial blocker) vs (EZ blocker) | ①②③ |

| Thoracotomy | |||||||||

| 23 | Mourisse, et al, 2013 (Netherlands) | A randomized controlled trial | Elective thoracic surgery | Thoracotomy | (14/50) vs (15/48) | (61 ± 13.3) vs (59 ± 13.6) | (25.4 ± 4.7) vs (27.0 ± 4.6) | (EZ blocker) vs (Double lumen tube) | ①②⑤⑥ |

| Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery | |||||||||

| Sternotomy | |||||||||

| 24 | Campos, et al, 2012 (USA) | A randomized controlled trial | Elective thoracic surgery/elective esophageal cancer surgery | Lung biopsy | (-/25) vs (-/25) | (-) vs (-) | - | (Arndt bronchial blocker) vs (Double lumen tube) | ①②③④ |

| Wedge resection | |||||||||

| Lobectomy | |||||||||

| Pleural decortication pleurodesis | |||||||||

| Chest wall resection mediastinal surgery | |||||||||

| 25 | Ruetzler, et al, 2011 (Austria) | A randomized controlled trial | Elective thoracic surgery | Lung biopsy | (12/19) vs (8/20) | (54.4 ± 20.2) vs (61.9 ± 14.4) | (25.6 ± 5.4) vs (26.6 ± 7.4) | (EZ blocker) vs (Double lumen tube) | ①②③⑤⑥ |

| Lobectomy | |||||||||

| Segmentectomy | |||||||||

| Pleural decortication | |||||||||

| 26 | Zhong, et al, 2009 (China) | A randomized controlled trial | Elective thoracic surgery | Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery | (13/30)/(11/30)/(10/30) vs (13/30) | (61 ± 9)/(63 ± 8)/(61 ± 8) vs (64 ± 8) | (21.3 ± 3.3)/(22.6 ± 3.4)/(22.8 ± 3.3) vs (21.3 ± 3.7) | (Fuji Uniblocker)/(Arndt bronchial blocker)/(Coopdech bronchial blocker) vs (Double lumen tube) | ①②③⑤⑥ |

| 27 | Narayanaswamy, et al, 2009 (Canada) | A randomized controlled trial | Elective thoracic surgery | Lobectomy | (-/78) vs (-/26) | (-) vs (-) | (28 ± 6) vs (26.7 ± 4.2) | (Arndt bronchial blocker)/(Cohen Flex-Tip bronchial blocker)/(Fuji Uniblocker) vs (Double lumen tube) | ②③ |

| Wedge resection | |||||||||

| Pneumonectomy | |||||||||

| Esophageal surgery | |||||||||

| Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery | |||||||||

| 28 | Dumans-Nizard, et al, 2009 (France) | A prospective, randomized, controlled trial | Elective thoracic surgery | Thoracoscopy | (3/16)/(7/16) vs (5/16) | (62.09 ± 13.82)/(55.64 ± 10.57) vs (62.55 ± 11.38) | - | (Cohen Flex-Tip bronchial blocker)/(Arndt bronchial blocker) vs (Double lumen tube) | ①②③ |

| Wedge | |||||||||

| Lobectomy | |||||||||

| Pneumonectomy | |||||||||

| Pleurodesis | |||||||||

| 29 | Knoll, et al, 2006 (Germany) | A randomized controlled trial | Elective thoracic surgery | Open pulmonary resection | (12/29) vs (10/27) | (62.8 ± 8.5) vs (60.4 ± 8.5) | (26.6 ± 7.0) vs (27.7 ± 8.9) | (Arndt bronchial blocker) vs (Double lumen tube) | ①⑤⑥ |

| 30 | Grocott, et al, 2003 (USA) | A Prospective, randomized, controlled trial | Port-Access cardiac surgery | Mitral valve repair or replacement | (-/14) vs (-/14) | (62 ± 12) vs (56 ± 14) | (24.3 ± 3.7) vs (28.7 ± 5.0) | (Arndt bronchial blocker) vs (Double lumen tube) | ③ |

| Tricuspid valve repair or replacement | |||||||||

| Aortic valve replacement | |||||||||

| 31 | Campos, et al, 2003 (USA) | A randomized controlled trial | Elective thoracic surgery | Lung biopsy | (-/16)/(-/32) vs (-/16) | (-) vs (-) | - | (Fuji Uniblocker)/(Arndt bronchial blocker) vs (Double lumen tube) | ①②③ |

| Wedge resection | |||||||||

| Lobectomy | |||||||||

| Segmentectomy pneumonectomy | |||||||||

| Pleural decortication pleurodesis | |||||||||

| Resection of mediastinal mass esophageal surgery | |||||||||

| 32 | Bauer, et al, 2001 (France) | A randomized controlled trial | Elective thoracic surgery | Mechanical pleurodesis + bullae resection | (-/7) vs (-/15) | (-) vs (-) | - | (Wiruthan bronchial blocker) vs (Double lumen tube) | ①②③ |

| Talc pleurodesis pleural biopsies | |||||||||

| Mediastinal node biopsies diagnostic | |||||||||

| Hamartoma excision pericardial window | |||||||||

| 33 | Campos, et al, 1996 (USA) | A randomized controlled trial | Elective thoracic surgery/Elective esophageal cancer surgery | Lobectomy | (-/20) vs (-/20) | (-) vs (-) | - | (Fuji Uniblocker) vs (Double lumen tube) | ①②③ |

| Lung biopsy | |||||||||

| Wedge resection | |||||||||

| Pneumonectomy | |||||||||

| Bullectomy | |||||||||

| Lung reduction | |||||||||

| Pleuroscopy | |||||||||

| Resection right mediastinal mass | |||||||||

| Esophageal surgery |

Outcome: ① The quality of lung collapse: proportion of complete lung collapse; ② Malposition rate: proportion of displacements detected by intraoperative bronchoscopy; ③ time for device placement: time required for airway device placement (unit: seconds); ④ The success of the first intubation attempt: proportion of first-attempt intubation success; ⑤ Sore Throat: proportion of postoperative sore throat occurrence; ⑥ Hoarseness: proportion of postoperative hoarseness occurrence.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram showing selection of studies.

NMA of the quality of lung collapse

Twenty-two studies reported lung collapse quality associated with 10 different one-lung ventilation devices. The network diagram depicted relationships among these devices (Fig. 2A). Node-splitting modeling detected no inconsistencies; therefore, the consistency model was applied for statistical analysis. According to the results of the NMA, lung collapse quality of DLT was superior to ABB [2.78 (1.15, 9.52), OR (95% CI), P < 0.05] (Fig. 3A). UB(Ex) ranked highest in SUCRA (71.7%, Fig.4A, Table S7, http://links.lww.com/JS9/E108).

Figure 2.

Network diagram between different ventilation devices.

Figure 3.

Results of network meta-analysis [OR/MD, (95% CI)]. (*) indicates statistical significance.

Figure 4.

Results of SUCRA.

NMA of malposition rate

The analysis of malposition rates from 26 studies involving 11 different OLV devices, shown in Fig. 2B, indicates that DLT had lower malposition rates compared to ABB, UB, and CFTBB [0.29 (0.15, 0.56); 0.39 (0.22, 0.66); 0.41 (0.17, 0.96), OR (95% CI), P < 0.05] (Fig. 3B). ABB(Ex) was most likely to experience malposition, as indicated by SUCRA ranking (81.3%, Fig.4B, Table S7, http://links.lww.com/JS9/E108).

NMA of time for device placement

The network diagram illustrates the relationships among device placement times associated with 12 different OLV devices across 29 studies (Fig. 2C). VDLT shows a shorter device placement time (Fig. 3C), consistent with the SUCRA ranking (7.1%, Fig.4C, Table S7, http://links.lww.com/JS9/E108).

NMA of the success of the first intubation attempt

Twelve studies reported the first intubation success rate associated with eight different OLV devices (Fig. 2D). According to the results of the NMA, the first intubation success rate with CBB was higher (Fig. 3D), consistent with its SUCRA ranking (96.4%, Fig.4D, Table S7, http://links.lww.com/JS9/E108).

NMA of sore throat and hoarseness

Twenty studies reported sore throat, while 15 studies reported hoarseness. The network diagrams for both are shown in Fig.2E-F. According to the results of the NMA, BBs had lower occurrence rates of sore throat and hoarseness (Fig. 3E-F). In SUCRA ranking, CBB and CFTBB caused the least sore throat and hoarseness (17.3% and 9%, respectively, Fig.4E-F, Table S7, http://links.lww.com/JS9/E108).

Efficacy, convenience, and safety analysis

The results of the NMA comparing different devices to DLT are summarized and plotted as a forest plot (Fig. 5). Six outcome indicators were paired into efficacy, convenience, and safety, and two-dimensional plots were created to analyze the clinical characteristics of different ventilation devices. Overall, compared to DLT, BBs were more prone to malposition but had lower incidences of sore throat and hoarseness. VDLT had comparable efficacy and safety to DLT but required less placement time (Fig. 6).

Figure 5.

Forest plot for the results of network meta-analysis [OR/MD, (95% CI)].

Figure 6.

Two-dimensional plot of clinical characteristics.

Discussion

The lung isolation technique is a critical skill for anesthesiologists, providing surgeons with optimal conditions and enhancing patient safety during surgery. Currently, various devices are available for achieving OLV, each with unique clinical characteristics[2]. Despite numerous comparisons in RCTs, comprehensive studies on the advantages and disadvantages of OLV devices are rare. Our aim is to conduct a thorough comparison of OLV devices through NMA, offering insights for different surgical scenarios and anesthesia requirements.

DLT is commonly used for OLV, but its thick diameter and rigid body pose challenges for intubation. During DLT intubation, the rotation of the tube body may also potentially cause airway injury[16,41]. Additionally, due to the anatomical differences between the left and right main bronchi, DLT typically requires FOB assistance for accurate positioning[46]. Changes in patient positioning, surgical manipulation, and procedures such as suctioning and lung inflation can lead to intraoperative tube displacement. Some DLTs are designed with a carinal hook to assist with positioning and prevent displacement; however, prolonged pressure from the hook on the carina and bronchus may lead to airway injury, which in severe cases can result in tracheal rupture[40,47]. Post-intubation, patients may experience hemodynamic instability and higher rates of complications[48]. The advent of VDLTs and BBs has addressed these issues, expanding the options for OLV management.

Our NMA results indicate that compared to DLT, VDLT has a shorter intubation time [−117.69 (−190.24, −45.12), MD (95% CI), P < 0.05] (Fig. 5). This finding is consistent with the study by Levy-Faber[30], which compared the intubation time between the VDLT group and the traditional DLT group, revealing a significant reduction in both intubation time and visual confirmation time for tube placement with VDLT (51 s vs 264 s, P < 0.0001). The displacement rates in the VDLT and DLT groups are similar, but the real-time visualization of VDLT allows anesthesiologists to identify displacements earlier, reducing the need for FOB due to displacement. Although the frequency of using FOB is lower with VDLT, its availability remains necessary in emergencies, as VDLT cannot quickly clear secretions from the view[7,30,49]. VDLT is composed of a tube body, miniature camera, LED light, video interface, and flushing system, similar in structure to DLT, with the tube body potentially being thicker than DLT. Therefore, patients may still experience complications such as sore throat, hoarseness, and airway injury postoperatively[50]. Additionally, during airway monitoring, we may need to consider potential airway damage from prolonged LED light operation causing tube heating.

BBs can be used with SLTs, LMAs, and tracheostomy tubes. They cause minimal airway injury, allow for rapid postoperative extubation, and do not require tube replacement for ICU admission. These advantages make them suitable for difficult airways, pediatric OLV, obese patients, and tracheostomized patients[9,36,51-53]. Our NMA results indicate that compared to DLT, CFTBB has a lower incidence of postoperative sore throat [0.14 (0.01, 0.88), OR (95% CI), P < 0.05] and hoarseness [0.07 (0.002, 0.61), OR (95% CI), P < 0.05], while ABB [3.40 (1.78, 6.50), OR (95% CI), P < 0.05], UB [2.59 (1.52, 4.45), OR (95% CI), P < 0.05], and CFTBB [2.45 (1.04, 5.93), OR (95% CI), P < 0.05] have higher malposition rates, and ABB has a lower lung collapse quality [0.36 (0.11, 0.88), OR (95% CI), P < 0.05]. The time for device placement of CFTBB [105.95 (39.23,170.35), MD (95% CI), P < 0.05] and ABB [50.91 (0.76, 101.46), MD (95% CI), P < 0.05] is longer compared to DLT (Fig. 5). Due to the different designs of BBs, their clinical characteristics also vary. The tip of the ABB features a loop that can be guided into the bronchus with a FOB. The UB, CBB, and CFTBB have angled tips for easier entry, while the EZB has a Y-shaped tip that fits the carina after placement. The insertion time of BBs may vary, depending on the anesthesiologist’s proficiency and the design of the BB tip[18]. Using the same tube as the bronchoscope may also reduce the torque during BB insertion, potentially affecting positioning. ABB is not only prone to misplacement but also has poorer lung collapse quality, which may be related to its oval-shaped balloon design that fails to securely seal the airway, leading to air leakage. EZB shows significantly lower stability in right-sided surgeries, likely because its balloon struggles to fully seal the right upper lobe bronchus near the carina[18,39]. When used together, BBs and LMAs can reduce oral injuries caused by laryngoscopy, lower airway invasiveness, and lessen airway-related complications[9]. However, this combination also has drawbacks. BBs may displace during changes in patient positioning, bronchoscopy, or surgery, while LMAs may leak when airway pressure increases, compromising lung isolation[32,45]. Due to the relatively narrow lumen of BBs, they may not be as convenient as DLTs for suctioning airway secretions, lung deflation, and re-expansion, sometimes requiring surgical assistance[22]. BBs cannot provide continuous positive airway pressure in the alveoli and cannot meet the requirements of specialized airway management, thus limiting their application[40].

Lung collapse quality and displacement rate serve as indicators of efficacy, while insertion time and first insertion success rate indicate convenience, and the incidence of sore throat and hoarseness reflects safety. Based on the comprehensive results of our systematic meta-analysis, we consider DLT to remain a reliable choice for OLV, while VDLT and BBs may offer advantages under certain conditions. Given the higher cost of use, VDLT may be more suitable for complex major surgeries, as its rapid airway establishment, continuous airway monitoring, good lung collapse quality, and stable lung isolation can meet the demands of such procedures. The promotion of enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) principles requires reducing postoperative complications, accelerating patient recovery, and providing comfortable medical services[54,55]. BBs may be more suitable for shorter surgeries requiring rapid recovery or specific patient populations.

First, our study has several limitations, including the inclusion of multiple multi-arm RCTs, which may affect the heterogeneity of the NMA results. Second, differences in surgical approaches may impact outcome assessments. The studies mainly focused on elective thoracic and esophageal surgeries, excluding emergency procedures like hemothorax and empyema, and rarely involved complex surgeries related to the thoracic spine or heart. Most studies also did not report the primary diagnosis of patients, so our conclusions are more cautious. Third, variations in how raw data were reported among studies and the conversions we performed may introduce bias. Additionally, we did not analyze airway injuries caused by different devices due to inconsistent definitions in the studies. Finally, the scatter of points in the six funnel plots was generally symmetrical, suggesting a low likelihood of publication bias in the included studies, although it cannot be completely ruled out (Figure S3, http://links.lww.com/JS9/E111). Therefore, our conclusions need further validation from higher-quality clinical studies.

Conclusion

Based on the NMA results, DLT remains a reliable choice for OLV. VDLT may be more suitable for complex surgeries, while BBs may be more suitable for shorter surgeries requiring rapid recovery or specific patient populations. The selection of OLV devices should be based on the patient’s condition and surgical requirements.

Footnotes

Supplemental Digital Content is available for this article. Direct URL citations are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal’s website, www.lww.com/international-journal-of-surgery.

Published online 12 May 2025

Contributor Information

Hezhi Wang, Email: 790654388@qq.com.

Conglan Wang, Email: wangconglan516@163.com.

Yuhan Huang, Email: hyh001029@163.com.

Rui Yuan, Email: yuan-rui03@163.com.

Xiaoyi Zhao, Email: 2581045585@qq.com.

Ethical approval

This study is a meta-analysis, so ethical approval is not applicable.

Consent

This study is based on published research and does not involve the patient’s personal privacy.

Source of funding

The authors declare no sources of funding.

Author contributions

Conceptualized and designed the investigation: H.L., Y.X. Data collection: H.L., H.W., C.W., Y.H., R.Y., X.Z. Data analysis and/or interpretation: H.L., H.W., C.W., Y.H., R.Y., X.Z. Drafted and critically revised the manuscript: H.L., Y.X. Reviewed and authorized the final version of the manuscript: H.L., H.W., C.W., Y.H., R.Y., X.Z., Y.X.

Conflicts of interest disclosure

None.

Guarantor

Haisu Li and Ying Xu.

Research registration unique identifying number (UIN)

PROSPERO (CRD42024513900).

Provenance and peer review

Not commissioned, externally peer-reviewed.

Data availability statement

The raw data of this study are derived from the included studies, which are available in public. All detailed data included in the study are available upon request by contact with the corresponding author.

Assistance with the study

None.

References

- [1].Campos JH. Current techniques for perioperative lung isolation in adults. Anesthesiology 2002;97:1295–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Cohen E. Current practice issues in thoracic anesthesia. Anesth Analg 2021;133:1520–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Zani G, Stefano M, Tommaso BF, et al. How clinical experience leads anesthetists in the choice of double-lumen tube size. J Clin Anesth 2016;32:1–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Falzon D, Alston RP, Coley E, Montgomery K. Lung isolation for thoracic surgery: from inception to evidence-based. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2017;31:678–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Brassard CL, Lohser J, Donati F, Bussières JS. Step-by-step clinical management of one-lung ventilation: continuing professional development. Can J Anaesth 2014;61:1103–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Karzai W, Schwarzkopf K. Hypoxemia during one-lung ventilation: prediction, prevention, and treatment. Anesthesiology 2009;110:1402–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Palaczynski P, Misiolek H, Bialka S, et al. A randomized comparison between the VivaSight double-lumen tube and standard double-lumen tube intubation in thoracic surgery patients. J Thoracic Dis 2022;14:3903–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Shum S, Moreno Garijo J, Tomlinson G, et al. A clinical comparison of 2 bronchial blockers versus double-lumen tubes for one-lung ventilation. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2023;37:2577–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Nakanishi T, Sento Y, Kamimura Y, et al. Combined use of the ProSeal laryngeal mask airway and a bronchial blocker vs. a double-lumen endobronchial tube in thoracoscopic surgery: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Anesth 2023;88:111136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Smith AF, Carlisle J. Reviews, systematic reviews and anaesthesia. Anaesthesia 2015;70:644–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Bucher HC, Guyatt GH, Griffith LE, Walter SD. The results of direct and indirect treatment comparisons in meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Clin Epidemiol 1997;50:683–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Bmj 2021;372:n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, et al. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. Bmj 2017;358:j4008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Luo D, Wan X, Liu J, Tong T. Optimally estimating the sample mean from the sample size, median, mid-range, and/or mid-quartile range. Stat Methods Med Res 2018;27:1785–805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Wan X, Wang W, Liu J, Tong T. Estimating the sample mean and standard deviation from the sample size, median, range and/or interquartile range. BMC Med Res Methodol 2014;14:135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Risse J, Szeder K, Schubert AK, et al. Comparison of left double lumen tube and y-shaped and double-ended bronchial blocker for one lung ventilation in thoracic surgery-a randomised controlled clinical trial. BMC Anesthesiol 2022;22:92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Xu Z, Yu H, Luo Y, Ye Y, Zhou C, Liang P. A randomized trial to assess the effect of cricoid displacing maneuver on the success rate of blind placement of double-lumen tube and Univent bronchial blocker. Ann Palliat Med 2021;10:1976–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Morris BN, Fernando RJ, Garner CR, et al. A randomized comparison of positional stability: the EZ-blocker versus left-sided double-lumen endobronchial tubes in adult patients undergoing thoracic surgery. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2021;35:2319–2325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Zhang TH, Liu XQ, Cao LH, Fu JH, Lin WQ. A randomised comparison of the efficacy of a Coopdech bronchial blocker and a double-lumen endotracheal tube for minimally invasive esophagectomy. Transl Cancer Res 2020;9:4686–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Liu Z, Zhao L, Zhu Y, et al. The efficacy and adverse effects of the Uniblocker and left-side double-lumen tube for one-lung ventilation under the guidance of chest CT. Exp Ther Med 2020;19:2751–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Cheng Q, He ZY, Xue P, et al. The disconnection technique with the use of a bronchial blocker for improving nonventilated lung collapse in video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery. J Thoracic Dis 2020;12:876–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Zheng ML, Niu ZQ, Chen P, et al. Effects of bronchial blockers on one-lung ventilation in general anesthesia A randomized controlled trail. Medicine 2019;98:e17387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Shaban AAE. Efficacy and safety of Cohen Flex-Tip blocker and left double lumen tube in lung isolation for thoracic surgery: a randomized comparative study. Ain Shams J Anesth 2019;11:8. [Google Scholar]

- [24].Lu Y, Dai W, Zong ZJ, et al. Bronchial blocker versus left double-lumen endotracheal tube for one-lung ventilation in right video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2018;32:297–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Heir JS, Guo SL, Purugganan R, et al. A randomized controlled study of the use of video double-lumen endobronchial tubes versus double-lumen endobronchial tubes in thoracic. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2018;32:267–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Templeton TW, Morris BN, Goenaga-Diaz EJ, et al. A prospective comparison of intraluminal and extraluminal placement of the 9-French Arndt bronchial blocker in adult thoracic surgery patients. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2017;31:1335–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Liu Z, He W, Jia Q, Yang X, Liang S, Wang X. A comparison of extraluminal and intraluminal use of the Uniblocker in left thoracic surgery. Medicine (United States) 2017;96:e6966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Bussières JS, Somma J, Del Castillo JL, et al. Bronchial blocker versus left double-lumen endotracheal tube in video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery: a randomized-controlled trial examining time and quality of lung deflation. Can J Anaesth 2016;63:818–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Schuepbach R, Grande B, Camen G, et al. Intubation with VivaSight or conventional left-sided double-lumen tubes: a randomized trial. Can J Anaesth D Anesthesie 2015;62:762–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Levy-Faber D, Malyanker Y, Nir RR, Best LA, Barak M. Comparison of VivaSight double-lumen tube with a conventional double-lumen tube in adult patients undergoing video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery. Anaesthesia 2015;70:1259–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Young Yoo J, Hee Kim D, Choi H, Kim K, Jeong Chae Y, Yong Park S. Disconnection technique with a bronchial blocker for improving lung deflation: a comparison with a double-lumen tube and bronchial blocker without disconnection. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2014;28:916–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Wang S, Zhang J, Cheng H, Yin J, Liu X. A clinical evaluation of the ProSeal laryngeal mask airway with a Coopdech bronchial blocker for one-lung ventilation in adults. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2014;28:900–03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Li Q, Li P, Xu J, Gu H, Ma Q, Pang L. A novel combination of the Arndt endobronchial blocker and the laryngeal mask airway ProSeal provides one-lung ventilation for thoracic surgery. Exp Ther Med 2014;8:1628–1632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Kus A, Hosten T, Gurkan Y, Akgul AG, Solak M, Toker K. A comparison of the EZ-blocker with a Cohen flex-tip blocker for one-lung ventilation. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2014;28:896–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Mourisse J, Liesveld J, Verhagen A, et al. Efficiency, efficacy, and safety of EZ-blocker compared with left-sided double-lumen tube for one-lung ventilation. Anesthesiology 2013;118:550–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Campos JH, Hallam EA, Ueda K. Lung isolation in the morbidly obese patient: a comparison of a left-sided double-lumen tracheal tube with the Arndt® wire-guided blocker. Br J Anaesth 2012;109:630–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Ruetzler K, Grubhofer G, Schmid W, et al. Randomized clinical trial comparing double-lumen tube and EZ-Blocker® for single-lung ventilation. Br J Anaesth 2011;106:896–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Zhong T, Wang W, Chen J, Ran L, Story DA. Sore throat or hoarse voice with bronchial blockers or double-lumen tubes for lung isolation: a randomised, prospective trial. Anaesth Intensive Care 2009;37:441–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Narayanaswamy M, McRae K, Slinger P, et al. Choosing a lung isolation device for thoracic surgery: a randomized trial of three bronchial blockers versus double-lumen tubes. Anesthesia Analg 2009;108:1097–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Dumans-Nizard V, Liu N, Laloë PA, Fischler M. A comparison of the deflecting-tip bronchial blocker with a wire-guided blocker or left-sided double-lumen tube. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2009;23:501–05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Knoll H, Ziegeler S, Schreiber JU, et al. Airway injuries after one-lung ventilation: a comparison between double-lumen tube and endobronchial blocker – A randomized, prospective, controlled trial. Anesthesiology 2006;105:471–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Grocott HP, Darrow TR, Whiteheart DL, Glower DD, Smith MS. Lung isolation during port-access cardiac surgery: double-lumen endotracheal tube versus single-lumen endotracheal tube with a bronchial blocker. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2003;17:725–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Campos JH, Kernstine KH. A comparison of a left-sided Broncho-Cath® with the torque control blocker univent and the wire-guided blocker. Anesthesia Analg 2003;96:283–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Bauer C, Winter C, Hentz JG, Ducrocq X, Steib A, Dupeyron JP. Bronchial blocker compared to double-lumen tube for one-lung ventilation during thoracoscopy. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2001;45:250–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Campos JH, Reasoner DK, Moyers JR. Comparison of a modified double-lumen endotracheal tube with a single-lumen tube with enclosed bronchial blocker. Anesthesia Analg 1996;83:1268–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Moreault O, Couture EJ, Provencher S, et al. Double-lumen endotracheal tubes and bronchial blockers exhibit similar lung collapse physiology during lung isolation. Can J Anaesth 2021;68:791–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Liu S, Mao Y, Qiu P, Faridovich KA, Dong Y. Airway rupture caused by double-lumen tubes: a review of 187 cases. Anesth Analg 2020;131:1485–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Liu C, Zhang T, Cao L, Lin W. Comparison of esketamine versus dexmedetomidine for attenuation of cardiovascular stress response to double-lumen tracheal tube intubation: a randomized controlled trial. Front Cardiovasc Med 2023;10:1289841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Koopman EM, Barak M, Weber E, et al. Evaluation of a new double-lumen endobronchial tube with an integrated camera (VivaSight-DL(™)): a prospective multicentre observational study. Anaesthesia 2015;70:962–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Saracoglu A, Saracoglu KT. VivaSight: a new era in the evolution of tracheal tubes. J Clin Anesth 2016;33:442–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Lv J, Ding X, Zhao J, et al. A combination of supraglottic airway and bronchial blocker for one-lung ventilation in infants undergoing thoracoscopic surgery. Heliyon 2023;9:e13576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Collins SR, Titus BJ, Campos JH, Blank RS. Lung isolation in the patient with a difficult airway. Anesth Analg 2018;126:1968–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Campos JH, Musselman ED, Hanada S, Ueda K. Lung isolation techniques in patients with early-stage or long-term tracheostomy: a case series report of 70 cases and recommendations. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2019;33:433–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Jenkins K, Grady D, Wong J, Correa R, Armanious S, Chung F. Post-operative recovery: day surgery patients’ preferences. Br J Anaesth 2001;86:272–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Zou Y, Liu Z, Miao Q, Wu J. A review of intraoperative protective ventilation. Anesthesiol Perioper Sci 2024;2:10. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data of this study are derived from the included studies, which are available in public. All detailed data included in the study are available upon request by contact with the corresponding author.