Abstract

Silk glands are modified labial glands that produce silk which has immense commercial importance. Silk is extruded out in liquid form after which the glands undergo autophagy and apoptosis during larval to pupal transition. Biogenic amines, specially spermidine and γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) are known to play an important role in autophagy. Yet, GABA is not identified in the silk glands till now and therefore its role in autophagy remains unknown. Current study aimed to evaluate role of biogenic amines in the autophagy of silk glands. Fifth instar silkworms were fed with control and spermidine supplemented mulberry leaves under controlled conditions. Qualitative and quantitative analysis of biogenic amines were analyzed in silk glands of control and spermidine fed groups at the end of feeding stage, spinning and pre-pupal stages. Biogenic amines were significantly decreased in the silk glands from feeding stage to non-feeding prepupal stages. Elevated levels of biogenic amines; putrescine, spermidine, and spermine were observed in silk glands at pre-pupal stage in the spermidine fed group. The unknown biogenic amine whose levels were significantly elevated during silk gland degeneration in both control and spermidine fed groups was identified as GABA by spectroscopic techniques. This is the first report of the identification of GABA in the silk glands of Bombyx mori which increased significantly following spermidine supplementation, resulting in elevated levels of calcium deposits, contributing to the early degeneration of the silk glands.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00726-025-03462-5.

Keywords: Autophagy, Biogenic amines, Bombyx mori, Calcium, GABA, Silk glands, Spermidine

Introduction

Autophagy and apoptosis of the cells in several organs are crucial events in the growth and development of the silkworm (Bombyx mori) (Franzetti et al. 2012). The silk glands (SGs) of B. mori undergo autophagy via an intracellular degradation process involving the recycling of components to maintain cellular homeostasis. SGs undergo autophagy during the spinning and prepupal stages (Days 9–11) and later undergo apoptosis during the pupal stage (Days 12–13) (Montali et al. 2017). Hormonal changes contribute to tissue degradation during metamorphosis. Studies have reported that programmed cell death in the anterior SGs is triggered by 20-hydroxyecdysone (20E), ecdysone receptor expression, Br–C, E75A, BmE74A, BHR3, and ßftz (Sekimoto et al. 2006).

Biogenic amines (BAs) such as putrescine (Put), spermidine (Spd), and spermine (Spm) play vital roles in the growth of organisms. In particular, Spd and γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) were shown to play important roles in the induction of autophagy in the brains, cardiomyocytes, and livers of Rattus, Mus musculus, Saccharomyces, Caenorhabditis elegans, Trypanosoma cruzi and Drosophila model organisms (Eisenberg et al. 2009; Filfan et al. 2020; Hui and Tanaka 2019; Madeo et al. 2010; Vanrell et al. 2013). Additionally, Spd supplementation enhanced autophagy flux in old human B cells as well as in the head and abdomen of honey bees ( Kojić et al. 2024; Zhang et al. 2019). A recent study reported the involvement of Spd in fasting-mediated autophagy in Saccharomyces, Drosophila, and human serum (Hofer et al. 2024). A decrease in polyamine levels has been observed in aging Drosophila brains, which was overcome following supplementation with Spd (Gupta et al. 2013). Notably, BA concentrations are tightly regulated by biosynthetic pathways and degradation mechanisms (Đorđievski et al. 2023; Kojić et al. 2024). The Spd degradation pathway through Put leads to GABA synthesis and reactive oxygen species production with the help of acetyl transferases, aldehyde dehydrogenase, and oxidases in rat intestinal mucosa, which contribute to cell death (Seiler 2004; Testore et al. 1999). GABA supplementation resulted in an increased antioxidant potential and enhanced expression of longevity-related genes in B. mori larvae (Tu et al. 2022). Additionally, calcium (Ca2+) is essential for autophagolysosomal maturation (Tian et al. 2015; Yamamoto et al. 1998). In B. mori, GABA regulates Ca2+ levels, which is vital for protein secretion, SG function, and fiber formation (Gu et al. 2024; Liu et al. 2023).

Polyamine, Spd was earlier shown by our lab to promote growth, economic parameters and help in alleviating oxidative stress of SGs in B. mori (Aparna et al. 2016; Kasa et al. 2023; Lattala et al. 2014). However, its role in SG degeneration is not investigated. In this study, we aimed to explore the effect of Spd supplementation on SG autophagy in B. mori. Supplementation with Spd was performed from day 1 until the end of the 5th instar stage, and the status of SG degradation was recorded on the last day of the feeding (F), spinning (S), and prepupal (PP) stages. The results showed increased GABA levels during SG degeneration, which was accelerated in the Spd-fed group.

Materials and methods

Rearing of the silkworm larvae and experimental design

We procured B. mori (CSR2 × CSR4) crossbred larvae at the 4th instar stage from Andhra Pradesh State Government Sericulture Centre, Chebrolu, East Godavari District, Andhra Pradesh, India. The larvae were reared under a standard rearing temperature of 28 ± 2 °C and relative humidity of 80–85% until the end of complete cocoon formation. A total of 150 larvae were maintained during each rearing period. On day 1 of the 5th instar stage, B. mori larvae were divided into two groups, with 75 larvae per group. Control group (Con) larvae were fed with mulberry leaves (V1 variety), and treatment group larvae were fed 50 µM Spd supplemented mulberry leaves (RM 5438; HiMedia Laboratories, India). The Spd concentration was determined based on earlier results obtained in the laboratory (Lattala et al. 2014). Rearing was repeated five times. The F, S, and PP stages correspond to days 7, 9, and 11 of larval–pupal development, respectively. Ten cocoons from the Con and Spd groups were randomly selected from each replicate and cut open to determine the status of pupal metamorphosis (n = 10). At the F, S, and PP stages, the SGs were dissected, and washed in phosphate buffer solution (PBS) prior to examining stored at −20 °C for further use.

Quantitative and qualitative analysis of BAs from SGs of Con and Spd groups

The BAs in the SGs of the Con and Spd-treated groups during the F, S, and PP stages (n = 6) were derivatized using dansyl chloride and quantified according to the published protocol (Lima et al. 2023; Rajan et al. 2022). The extracted dansylated amines were estimated using a fluorescence spectrophotometer (Cary WinFLR, Cary Eclipse Fluorescence spectrometer, Agilent, USA) at an excitation wavelength of 350 nm and an emission wavelength of 495 nm. Commercially available Spd was dansylated and used as the standard.

Qualitative analysis was performed using thin-layer chromatography (TLC) plates (n = 3) coated with silica (60 F254; Merck Millipore, Burlington, Massachusetts, USA). Ethyl acetate and n-hexane (3:4 v/v ratio) were used to generate a chromatogram. Imaging and densitometric analyses were performed using Image Lab software (version 6.0; Bio-Rad Gel Doc XR+). The unknown band was eluted from the TLC plates and processed for HPLC, LC–MS, and NMR analyses.

HPLC analysis of the dansylated unknown band and known dansylated GABA was performed as previously described (Slocum et al. 1989). The unknown band was eluted in ethyl acetate as previously described (Lima et al. 2023). The sample and standard dansylated GABA were chromatographed at 25 °C using a C18 column (4.6 × 250 mm) with a 5 µm particle size using Agilent Eclipse Plus. Dansylated amines were eluted at a flow rate of 1 mL min−1 using Milli-Q water as solvent A and methanol as solvent B. The chromatogram obtained from the unknown band was compared with that from the standard GABA based on the retention time (RT) and intensity (volts) (OpenLab software, Agilent 1260 Infinity, USA).

Structural analysis of unknown band through liquid chromatography—mass spectroscopy, multiple reactions monitoring (MRM), and 1H NMR

LC–MS/MS analysis was performed to identify the mass of the unknown band. The selected band was processed as described in a previous study (Lima et al. 2023; Samarra et al. 2019) by MRM and analyzed using SCIEX QTRAP (Analyst software 1.7.3). The spectrum obtained from the unknown band was compared with that of standard dansylated GABA based on the m/z ratios of the precursor and product ions. Furthermore, 1H NMR analyses was conducted using an NMR spectrometer at 400 MHz for the identification of hydrogen atoms.

Biochemical estimation of GABA in SGs

Quantification of GABA levels in SGs of Con and Spd groups on F, S and PP stages (n = 5) was performed based on the published protocol with slight modifications (Yuwa-Amornpitak et al. 2020). The SG homogenates prepared in phosphate buffer were added to borate buffer, 6% phenol, and 0.6% sodium hypochlorite, and the reaction mixture was boiled for 10 min and then cooled. Absorbance was recorded at 630 nm. Commercially available GABA (RM444; HiMedia, India) was used as a standard to calculate the GABA concentration.

Quantification of total Ca2+ levels in SGs

Ca2+ analysis was performed according to a previously published protocol (Liu et al. 2023; Subramanyam and Sarangi 1989), with slight modifications. The SGs were weighed and homogenized in deionized water (10% w/v). The collected supernatant of the SGs was diluted to an equal volume at a 1:1 ratio with 3.5% PCA. The mixture was then filtered (n = 5) and used for estimation with the help of a flame atomic absorption spectrometer (240 FS/GTA 120 AA system; Agilent, USA).

Alizarin Red staining of SG sections

The isolated PSGs from F, S, and PP stages were fixed in 4% formaldehyde and stored at 4 °C for 24 h. The PSGs were washed in 1X PBS, fixed in formalin and embedded in paraffin blocks. Cross–sections of 3 µm were prepared using microtome and stained with alizarin red (50 µg) (TC255; HiMedia) as described earlier (Waku and Sumimoto 1971). The stained cross sections were observed under confocal microscopy (Olympus FV 4000) to assess the calcium deposits.

Statistical analysis of the data

BA, GABA and Ca2+ quantification data were presented as mean ± SEM. Graphs were plotted using GraphPad Prism 10.1 software. Statistical analysis of the data was performed using Student’s t-test, assuming equal variance, in Microsoft excel. *** indicates significance p < 0.001, ** indicates significance p < 0.01, and * indicates significance p < 0.05. Comparison of different days in the same groups and between groups was color coded.

Results

Endogenous BA levels show significant decrease in SGs during larval – PP transition in both Con and Spd groups

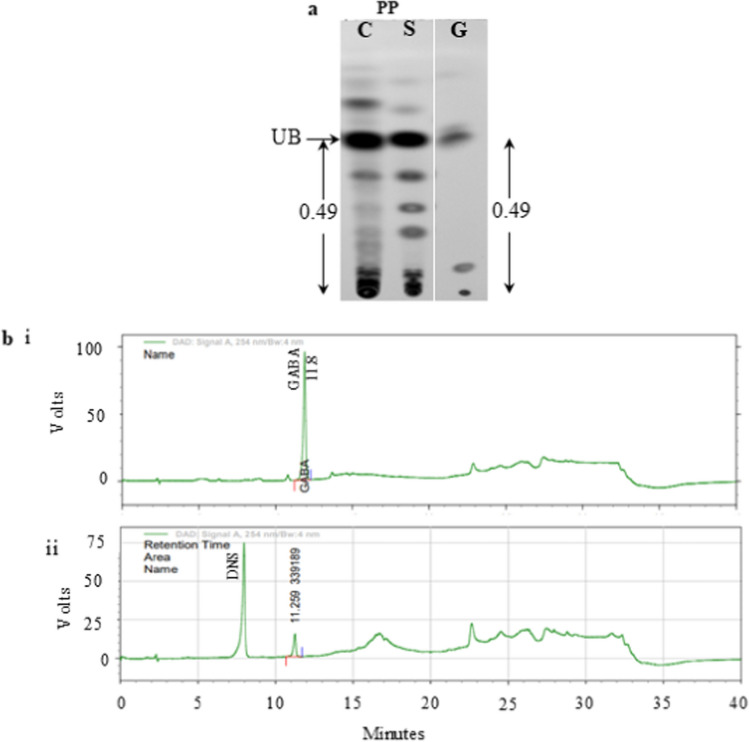

SGs were checked for degeneration from F to PP stage in the Con and Spd fed groups. Morphologically, SGs in the Spd group showed enhanced degeneration (Fig. 1a). BAs extracted from the SGs were quantified on F, S and PP stages to assess their changes during degeneration from larval to PP stage. The results showed significant decrease in BAs levels from F to PP stage in both Con and Spd groups (p < 0.001, p < 0.05), respectively. Significantly elevated levels of BAs were observed in Spd group on PP stage compared to the Con group (Fig. 1b). Qualitative analysis of dansylated BAs from SGs at the F, S, and PP stages by TLC showed bands corresponding to standard Spm, Spd, and Put, as well as a highly intense unknown band (Fig. 1c). The Spd group exhibited elevated Put, Spd, and Spm levels during the PP stage (Fig. 1d). The Rf value of the unknown band corresponded to the Rf value of the standard GABA of 0.49 (Fig. 2a). Subsequent HPLC analysis showed the RT of the unknown dansylated band at 11.2 min and that of dansylated GABA at 11.8 (Fig. 2b). Thus, BA levels decreased significantly during SG degeneration in Con groups which were recovered partially upon Spd supplementation.

Fig. 1.

Effect of Spd on BAs during feeding (F), spinning (S) and pre pupal (PP) stages. a Representative picture showing morphological changes in the SGs of Con and Spd groups stained with methylene blue. b Quantitative analysis of BA (n = 6). c Qualitative analysis of BA by silica TLC along with marker of known PA mix (M). Unknown band (UB) observed in the samples is shown by an arrow. d Densitometric analysis of Put, Spd and Spm band from TLC plate on PP stage (n = 3). C and S indicate Con and Spd groups respectively. ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, and *p < 0.05 are indicative of statistically significant differences

Fig. 2.

TLC and HPLC analyses of unknown BA observed in the SG samples on PP stage. a Qualitative analysis of unknown BA by silica TLC on PP stage of Con and Spd treated group along with standard GABA (G). b(i) HPLC analysis of dansylated GABA standard b(ii) HPLC analysis of unknown BA eluted from TLC plate. DNS represents dansyl chloride

Spectroscopic analysis confirmed the highly intense unknown band in SGs as GABA

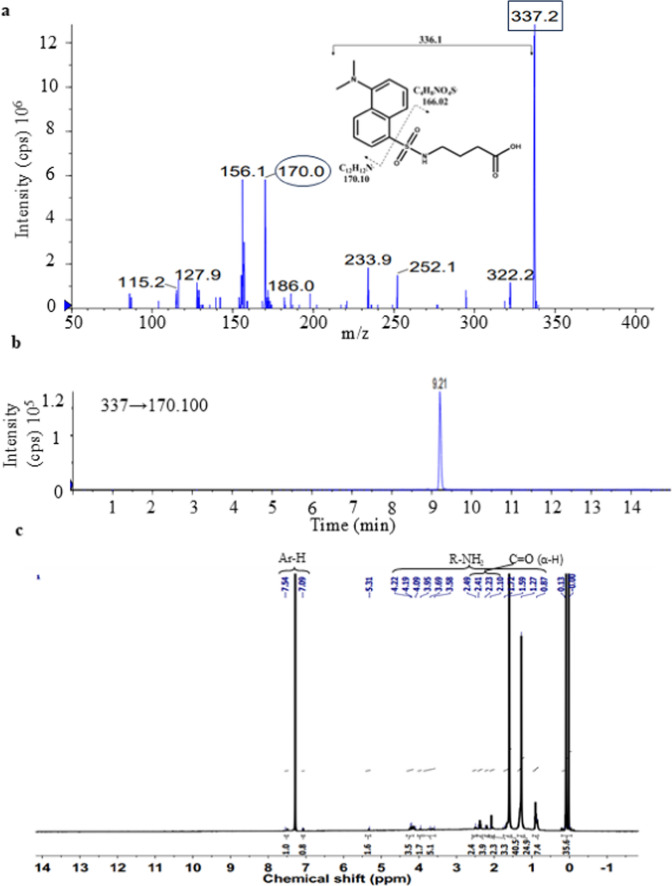

To identify the unknown BA, it was eluted through TLC using ethyl acetate, dissolved in methanol, and processed. Further analysis was performed using a triple quadrupole tandem mass spectrometer with an enhanced product ion in the positive ion mode. Fragmentation of the unknown band was performed by applying a collision energy of 25 eV, which showed a precursor ion peak at m/z 337.2 (Fig. 3a). This matched the standard GABA peak at 337.0 (Fig. S1). The product ion obtained through cleavage of the sulfonyl moiety of dansyl chloride was at m/z 170, corresponding to the dansyl group. MRM data confirmed the fragmentation of the precursor ion (m/z 337.2) to the daughter ion (m/z 170) at 9.21 min (Fig. 3b). Its molecular nature was determined through 1H NMR (Fig. 3c). The 1H NMR analysis of unknown BA showed resonance at 1.27 ppm that were attributed to methylene protons in the ß position to the nitrogen. Resonance peaks observed between 2.1 and 2.49 ppm were attributed to methylene protons in the α position to the carbonyl group. Further, resonance peaks between 7 and 8 ppm were due to the protons in the aromatic ring of the dansyl chloride. Thus, structural analysis confirmed that the unknown band was dansylated GABA.

Fig. 3.

Structural analysis of unknown dansylated BA. a LC–MS spectrum showing fragmentation of unknown BA. b MRM scan of the unknown BA showing transition of m/z 337 → m/z 170.1. c 1H NMR of the unknown band showing hydrogens of different groups

Elevated levels of GABA corresponded with early degradation of SGs in the Spd group

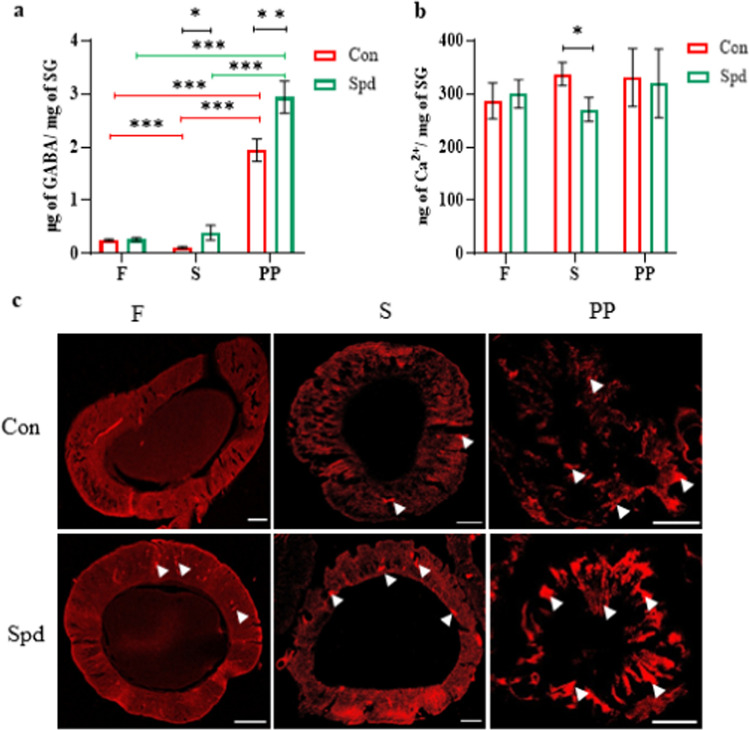

Based on the identification of the unknown band as GABA, biochemical quantification of GABA in the SGs of the Con and Spd-treated groups from the F to PP stages was performed. Significantly elevated levels of GABA were found in both groups (p < 0.001). The Spd-treated group showed a significant increase in GABA levels compared with those of the Con group during the S and PP stages (p < 0.05, p < 0.001, respectively) (Fig. 4a). Therefore, polyamine degradation during SG degeneration could have led to increased GABA levels.

Fig. 4.

Biochemical estimations showing changes in the SGs during F, S, and PP stages. a Quantification of GABA and b Ca2+ levels in the SGs of Con and Spd groups. (n = 5). c Alizarin red staining of PSG sections showing Ca2+ deposition (white arrowsheads) in the Con and Spd groups. Scale bar represents 50 µM. ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01 *p < 0.05

Elevated Ca2+ deposits were found in the SGs of Spd treated group

GABA regulates Ca2+ influx to maintain cellular homeostasis. Thus, quantification of total Ca2+ was performed during the larval–PP transition. No significant change in total Ca2+ levels were observed on different days in Con and Spd groups. Compared with the Con group, the Spd-treated group showed a significant decrease in Ca2+ levels at the S stage (p < 0.05) (Fig. 4b). Alizarin red staining of the PSG sections was performed to detect Ca2+ deposits. An increase in intracellular Ca2+ deposits in the epithelium of SGs was observed from the F to PP stages in both groups. The Spd-fed PSG sections at the PP stage showed higher Ca2+ deposition than those in the Con group (Fig. 4c). Thus, the increase in GABA levels could have promoted intracellular Ca2+ deposits.

Discussion

BAs play crucial roles in tissue development and autophagy. Spd, Spm, Glutamine, and GABA are particularly important for the development of B. mori (Fathy et al. 2024; Lattala et al. 2014; Tu et al. 2022; Yerra and Mamillapalli 2016). Notably, B. mori larvae feed until the end of the 5th instar and progress toward the non-feeding S, PP, and pupal stages. Silk is secreted by SGs during the F stage and released during the S stage (Perdrix-Gillot 1979). Subsequently, SGs undergo degradation involving autophagy (end of PP stage) and apoptosis (pupal stage) during the non-feeding stages (Goncu and Parlak 2008; Montali et al. 2017). In this study, we aimed to determine the role of BAs during SG degradation from the F to PP stages. We supplemented Spd during the 5th instar stage and monitored the SGs for morphological and BA changes from the F to PP stages.

Decreased levels of polyamines were found during aging and individuals who live longer than 100 years show elevated levels (Pucciarelli et al. 2012). Increased BA levels have been shown to promote starvation-induced autophagy of tissues and cells (Eisenberg et al. 2009; Hofer et al. 2024; Vanrell et al. 2013). The promotion of longevity after supplementation of Spd was proposed to be due to the induction of autophagy. The results of the present study showed a similar trend where the total BAs from the SGs of the Spd and Con groups showed a significant decrease in their levels from the F to PP stages and increased intracellular levels of polyamines with Spd supplementation. Moreover, qualitative analysis of BAs from the SGs of Spd fed group showed increased levels of Spd, Spm and Put. Similar trend was observed in yeast cells, which showed decreasing levels of polyamines with age, which reversed upon Spd supplementation (Eisenberg et al. 2009). This could be due to the interconversion among the polyamines, Put, Spd, and Spm. A highly intense band that increased in concentration from the F to PP stages was observed in the Con and Spd SGs. Structural analysis of the unknown band using HPLC, LC–MS, and MRM techniques confirmed that the unknown band was dansylated GABA. To our knowledge, this is the first report of endogenous GABA in the SGs of B. mori. Biochemical quantification showed highly significant increased GABA levels from the F to PP stages in both the Con and Spd groups. Acetylation and oxidation of PAs inhibit its biosynthesis and promotes their breakdown (Erwin and Pegg 1986). GABA is a catabolic product of PAs (Seiler 2004) that regulates autophagy (Hui and Tanaka 2019). Therefore, catabolism of the PAs in the SGs during the non-feeding stage could have resulted in the increased amounts of GABA in SGs of Con and Spd groups. Ca2+ is essential for silk secretion, formation, and gland function. Its level in SGs decreases after the release of silk at the end of the S stage (Liu et al. 2023). Cytosolic Ca2+ induces autophagy by activating Ca2+-dependent kinases involved in autophagy (Bootman et al. 2018). Differences in Ca2+ levels are linked to the maintenance and release of different forms of silk. It is reported that total Ca2+ levels showed a significant decrease during the S stage and an increase during the PP stage (Liu et al. 2023). Similar to the published results in the current study, intracellular Ca2+ levels showed elevated levels in the SGs of the Con and Spd group during degeneration. Alizarin red staining confirmed the accumulation of intracellular Ca2+ in the Spd group. The intracellular Ca2+ levels increased in the Spd group similar to the results obtained from GABA supplementation in rice (Jan et al. 2024). Significant increase in GABA levels could be responsible for SG degeneration during larval—Pupal transition in B. mori. The decreased levels of BAs and increased GABA levels in Spd group could be responsible for early degeneration of SGs upon Spd supplementation (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Schematic representation showing the mechanism of spermidine induced silk gland degeneration in B. mori. DAO represents diamine oxidase, and ALDH represents aldehyde dehydrogenase. Green arrows represent increased levels and red arrow indicates decreased levels

Conclusion

In conclusion, the decrease in BAs facilitated SG degeneration during larval—pupal transition. GABA is identified for the first time in SGs of B. mori, whose levels are elevated in the Spd group. Increased GABA levels promoted Ca2+ deposits in Spd supplemented SGs, which could have facilitated silk excretion and autophagy of SGs. Therefore, the study shows that BAs, especially GABA, play an important role in SGs degeneration.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Andhra Pradesh State Government Sericulture Centre, Chebrolu, for providing silkworms; Department of Chemistry, GSS, GITAM for HPLC analysis through DST-FIST funding (SR/FST/ETI-373/2016), GITAM/MURTI-SAIF facility for NMR, Mass analysis and Confocal microscope facility. BGLD acknowledges University Grant Commission, Ministry of Education, Government of India for Ph.D. scholarship (UGCES-22-GE-AND-F-SJSGC-15816).

Author contributions

B.G.L.D. performed rearing and maintenance of the silkworms, polyamine analysis, biochemical, cell biology experiments and analyzed the data and prepared the first draft. A.M. conceptualized the idea and supervised the experiments.

Funding

No funding.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Aparna Y, Surekha C, Satyavathi VV, Anitha M (2016) Spermidine alleviates oxidative stress in silk glands of Bombyx mori. J Asia-Pac Entomol 19:1197–1202 [Google Scholar]

- Bootman MD, Chehab T, Bultynck G, Parys JB, Rietdorf K (2018) The regulation of autophagy by calcium signals: Do we have a consensus? Cell Calcium 70:32–46. 10.1016/j.ceca.2017.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Đorđievski S, Vukašinović EL, Čelić TV, Pihler I, Kebert M, Kojić D, Purać J (2023) Spermidine dietary supplementation and polyamines level in reference to survival and lifespan of honey bees. Sci Rep 13:4329. 10.1038/s41598-023-31456-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg T, Knauer H, Schauer A, Büttner S, Ruckenstuhl C, Carmona-Gutierrez D, Ring J, Schroeder S, Magnes C, Antonacci L, Fussi H, Deszcz L, Hartl R, Schraml E, Criollo A, Megalou E, Weiskopf D, Laun P, Heeren G, Breitenbach M, Grubeck-Loebenstein B, Herker E, Fahrenkrog B, Fröhlich K-U, Sinner F, Tavernarakis N, Minois N, Kroemer G, Madeo F (2009) Induction of autophagy by spermidine promotes longevity. Nat Cell Biol 11:1305–1314. 10.1038/ncb1975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erwin BG, Pegg AE (1986) Regulation of spermidine/spermine N1-acetyltransferase in L6 cells by polyamines and related compounds. Biochem J 238:581–587. 10.1042/bj2380581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fathy DM, El-Kady HA, Ata TE, El-Kady NAM (2024) Impact of glutamine addition on biological and economical characteristics of the silkworm larvae B. mori L. J Plant Prot Pathol 15:363–367. 10.21608/jppp.2024.323980.1268 [Google Scholar]

- Filfan M, Olaru A, Udristoiu I, Margaritescu C, Petcu E, Hermann DM, Popa-Wagner A (2020) Long-term treatment with spermidine increases health span of middle-aged Sprague-Dawley male rats. GeroScience 42:937–949. 10.1007/s11357-020-00173-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franzetti E, Huang Z-J, Shi Y-X, Xie K, Deng X-J, Li J-P, Li Q-R, Yang W-Y, Zeng W-N, Casartelli M, Deng H-M, Cappellozza S, Grimaldi A, Xia Q, Tettamanti G, Cao Y, Feng Q (2012) Autophagy precedes apoptosis during the remodeling of silkworm larval midgut. Apoptosis 17:305–324. 10.1007/s10495-011-0675-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goncu E, Parlak O (2008) Some autophagic and apoptotic features of programmed cell death in the anterior silk glands of the silkworm, Bombyx mori. Autophagy 4:1069–1072. 10.4161/auto.6953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu H, Zou H, Cheng J, Liu X, Jiang Z, Peng P, Li F, Li B (2024) Mechanism of programmed cell death in the posterior silk gland of the silkworm, Bombyx mori, during pupation based on Ca homeostasis. Insect Mol Biol 33:551–559. 10.1111/imb.12911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta VK, Scheunemann L, Eisenberg T, Mertel S, Bhukel A, Koemans TS, Kramer JM, Liu KSY, Schroeder S, Stunnenberg HG, Sinner F, Magnes C, Pieber TR, Dipt S, Fiala A, Schenck A, Schwaerzel M, Madeo F, Sigrist SJ (2013) Restoring polyamines protects from age-induced memory impairment in an autophagy-dependent manner. Nat Neurosci 16:1453–1460. 10.1038/nn.3512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofer SJ, Daskalaki I, Bergmann M, Friščić J, Zimmermann A, Mueller MI, Abdellatif M, Nicastro R, Masser S, Durand S, Nartey A, Waltenstorfer M, Enzenhofer S, Faimann I, Gschiel V, Bajaj T, Niemeyer C, Gkikas I, Pein L, Cerrato G, Pan H, Liang Y, Tadic J, Jerkovic A, Aprahamian F, Robbins CE, Nirmalathasan N, Habisch H, Annerer E, Dethloff F, Stumpe M, Grundler F, Wilhelmi de Toledo F, Heinz DE, Koppold DA, Rajput Khokhar A, Michalsen A, Tripolt NJ, Sourij H, Pieber TR, de Cabo R, McCormick MA, Magnes C, Kepp O, Dengjel J, Sigrist SJ, Gassen NC, Sedej S, Madl T, De Virgilio C, Stelzl U, Hoffmann MH, Eisenberg T, Tavernarakis N, Kroemer G, Madeo F (2024) Spermidine is essential for fasting-mediated autophagy and longevity. Nat Cell Biol 26:1571–1584. 10.1038/s41556-024-01468-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hui KK, Tanaka M (2019) Autophagy links MTOR and GABA signaling in the brain. Autophagy 15:1848–1849. 10.1080/15548627.2019.1637643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jan R, Asaf S, Lubna, Farooq M, Asif S, Khan Z, Park J-R, Kim E-G, Jang Y-H, Kim K-M (2024) Augmenting rice defenses: exogenous calcium elevates GABA levels against WBPH infestation. Antioxidants 13:1321. 10.3390/antiox13111321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasa M, Jolapuram S, Lima A, Didugu BGL, Poosapati JR, Mamillapalli A (2023) Bivoltine cocoon color sex-limited breeds of Bombyx mori (Lepidoptera: Bombycidae) show enhanced economic performance and fecundity following spermidine supplementation. J Econ Entomol 116:1679–1688. 10.1093/jee/toad126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kojić D, Spremo J, Đorđievski S, Čelić T, Vukašinović E, Pihler I, Purać J (2024) Spermidine supplementation in honey bees: autophagy and epigenetic modifications. PLoS ONE 19:e0306430. 10.1371/journal.pone.0306430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lattala GM, Kandukuru K, Gangupantula S, Mamillapalli A (2014) Spermidine enhances the silk production by mulberry silkworm. J Insect Sci 14:207. 10.1093/jisesa/ieu069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lima A, Didugu BGL, Chunduri AR, Rajan R, Jha A, Mamillapalli A (2023) Thermal tolerance role of novel polyamine, caldopentamine, identified in fifth instar Bombyx mori. Amino Acids 55:287–298. 10.1007/s00726-022-03226-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q, Wang X, Zhou Y, Tan X, Xie X, Li Y, Dong H, Tang Z, Zhao P, Xia Q (2023) Dynamic changes and characterization of the metal ions in the silk glands and silk fibers of silkworm. Int J Mol Sci 24:6556. 10.3390/ijms24076556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madeo F, Eisenberg T, Büttner S, Ruckenstuhl C, Kroemer G (2010) Spermidine: a novel autophagy inducer and longevity elixir. Autophagy 6:160–162. 10.4161/auto.6.1.10600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montali A, Romanelli D, Cappellozza S, Grimaldi A, de Eguileor M, Tettamanti G (2017) Timing of autophagy and apoptosis during posterior silk gland degeneration in Bombyx mori. Arthropod Struct Dev 46:518–528. 10.1016/j.asd.2017.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perdrix-Gillot S (1979) DNA synthesis and endomitoses in the giant nuclci of the silkgland of Bombyx mori. Biochimie 61:171–204. 10.1016/S0300-9084(79)80066-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pucciarelli S, Moreschini B, Micozzi D, De Fronzo GS, Carpi FM, Polzonetti V, Vincenzetti S, Mignini F, Napolioni V (2012) Spermidine and spermine are enriched in whole blood of nona/centenarians. Rejuvenation Res 15:590–595. 10.1089/rej.2012.1349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajan R, Chunduri AR, Siripurapu P, Satti A, Kottakota S, Marupilla B, Kallare A, Mamillapalli A (2022) DFMO feeding lowers polyamine levels and causes developmental defects in the silkworm Bombyx mori. J Asia-Pac Entomol 25:101835. 10.1016/j.aspen.2021.10.011 [Google Scholar]

- Samarra I, Ramos-Molina B, Queipo-Ortuño MI, Tinahones FJ, Arola L, Delpino-Rius A, Herrero P, Canela N (2019) Gender-related differences on polyamine metabolome in liquid biopsies by a simple and sensitive two-step liquid-liquid extraction and LC-MS/MS. Biomolecules 9:779. 10.3390/biom9120779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seiler N (2004) Catabolism of polyamines. Amino Acids 26(3):217–233. 10.1007/s00726-004-0070-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekimoto T, Iwami M, Sakurai S (2006) Coordinate responses of transcription factors to ecdysone during programmed cell death in the anterior silk gland of the silkworm. Bombyx Mori Insect Mol Biol 15:281–292. 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2006.00641.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slocum RD, Flores HE, Galston AW, Weinstein LH (1989) Improved method for HPLC analysis of polyamines, agmatine and aromatic monoamines in plant tissue. Plant Physiol 89:512–517. 10.1104/pp.89.2.512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramanyam MVV, Sarangi SK (1989) Sodium coupled nutrient transport in the midgut tissue of the silkworm, Bombyx mori L. Proc Anim Sci 98:121–125. 10.1007/BF03179636 [Google Scholar]

- Testore G, Cravanzola C, Bedino S (1999) Aldehyde dehydrogenase from rat intestinal mucosa: purification and characterization of an isozyme with high affinity for γ-aminobutyraldehyde. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 31:777–786. 10.1016/S1357-2725(99)00026-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian X, Gala U, Zhang Y, Shang W, Jaiswal SN, di Ronza A, Jaiswal M, Yamamoto S, Sandoval H, Duraine L, Sardiello M, Sillitoe RV, Venkatachalam K, Fan H, Bellen HJ, Tong C (2015) A voltage-gated calcium channel regulates lysosomal fusion with endosomes and autophagosomes and is required for neuronal homeostasis. PLOS Biol 13:e1002103. 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu J, Jin Y, Zhuo J, Cao X, Liu G, Du H, Liu L, Wang J, Xiao H (2022) Exogenous GABA improves the antioxidant and anti-aging ability of silkworm (Bombyx mori). Food Chem 383:132400. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2022.132400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanrell MC, Cueto JA, Barclay JJ, Carrillo C, Colombo MI, Gottlieb RA, Romano PS (2013) Polyamine depletion inhibits the autophagic response modulating Trypanosoma cruzi infectivity. Autophagy 9:1080–1093. 10.4161/auto.24709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waku Y, Sumimoto K-I (1971) Metamorphosis of midgut epithelial cells in the silkworm (Bombyx Mori L.) with special regard to the calcium salt deposits in the cytoplasm. I. Light Microsc Tissue Cell 3:127–136. 10.1016/S0040-8166(71)80035-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto A, Tagawa Y, Yoshimori T, Moriyama Y, Masaki R, Tashiro Y (1998) Bafilomycin A1 prevents maturation of autophagic vacuoles by inhibiting fusion between autophagosomes and lysosomes in rat hepatoma cell line, H-4-II-E cells. Cell Struct Funct 23:33–42. 10.1247/csf.23.33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yerra A, Mamillapalli A (2016) Effect of polyamines on parental and hybrid strains of Bombyx mori. J Appl Biol Biotechnol 4:027–031. 10.7324/JABB.2016.40605 [Google Scholar]

- Yuwa-Amornpitak T, Butkhup L, Yeunyaw P-N (2020) Amino acids and antioxidant activities of extracts from wild edible mushrooms from a community forest in the Nasrinual District, Maha Sarakham, Thailand. Food Sci Technol 40:712–720. 10.1590/fst.18519 [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Alsaleh G, Feltham J, Sun Y, Napolitano G, Riffelmacher T, Charles P, Frau L, Hublitz P, Yu Z, Mohammed S, Ballabio A, Balabanov S, Mellor J, Simon AK (2019) Polyamines control eIF5A hypusination, TFEB translation, and autophagy to reverse B cell senescence. Mol Cell 76:110-125.e9. 10.1016/j.molcel.2019.08.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.