Abstract

We describe a case of a 57-year-old Caribbean-Black male with a medical history of concealed human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome who presented with cardiac tamponade (CT) secondary to disseminated histoplasmosis. The patient underwent emergent pericardiocentesis with immediate normalization of his hemodynamic status and resolution of obstructive shock. The clinician should consider atypical etiologies of CT, such as opportunistic infections in patients with HIV/AIDS.

Keywords: cardiac tamponade (CT), pericardial effusion, disseminated histoplasmosis (DH), pericardiocentesis, human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS)

Introduction

Histoplasmosis is a systemic fungal infection caused by Histoplasma capsulatum, a dimorphic fungus endemic to regions with high bird or bat guano concentrations, such as Trinidad and Tobago.1-3 Most exposed individuals experience mild, self-limiting respiratory infections.4,5 However, in immunocompromised patients or those with underlying pulmonary comorbidities, H. capsulatum can disseminate (disseminated histoplasmosis, DH) and progress to a more fulminant severity, with potentially lethal complications.6,7

DH can present with a diverse spectrum of clinical manifestations. These varied presentations, coupled with the potential for co-infection with other pathogens, can obfuscate the diagnostic process. 8 One of the most life-threatening complications of DH is cardiac involvement, often presenting as endocarditis, pericarditis, and pericardial effusion. In severe cases, these can progress to cardiac tamponade (CT).9-11

Given the paucity of data on the cardiac manifestations of DH, particularly within the Caribbean diaspora, we describe a case of a 57-year-old Caribbean-Black male with a medical history of human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS) who presented with CT secondary to DH. The patient underwent emergent pericardiocentesis with immediate normalization of his hemodynamic status and resolution of obstructive shock. His diagnostic profile was highly suggestive of DH.

Case Presentation

The patient is a 57-year-old Caribbean-Black male with a concealed medical history of HIV/AIDS for the past decade, nonadherent to antiretroviral therapy (ART), and unknown recent CD4 and HIV ribonucleic acid (RNA) levels (this was only revealed later during his ensuing hospitalization) who presented to the emergency department with the symptom-complex of progressive exertional dyspnea, 2-pillow orthopnea, and generalized fatigue over the preceding week. He did not report any medical, illicit, or recreational drug use. His family history was not significant. He did not experience any antecedent infection, nor did he have any pet or travel history. His coronavirus disease 2019 and influenza screening panels were both negative.

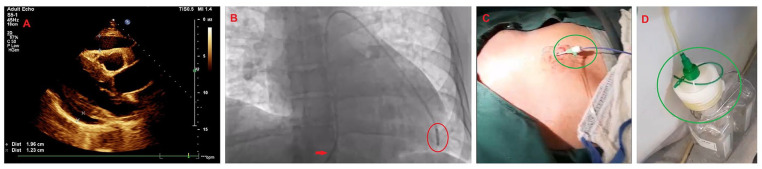

Upon physical examination, his vital signs included a blood pressure of 100/87 mm of mercury, a heart rate of 122 beats per minute, a respiratory rate of 26 breaths per minute, and a peripheral oxygen saturation of 92% on room air and afebrile. The patient was somnolent but had no overt focal neurodeficits. The cardiovascular examination revealed muffled heart sounds (S1 and S2) with an elevated jugular venous pulse to the mandibular angle (12 cm of water). His apical impulse was not displaced; however, had a dyskinetic character. The respiratory examination revealed decreased air entry with mild, scattered crackles throughout. The abdominal examination was unremarkable, with normal bowel sounds. There was no anasarca or peripheral edema. A quick, bedside, 2-dimensional transthoracic echocardiogram was performed, which revealed tamponade with a large circumferential pericardial effusion and both right atrial and ventricular collapse (Figure 1A).12,13

Figure 1.

The patient’s bedside transthoracic echocardiogram and practical aspects of the emergent pericardiocentesis. (A) The parasternal long-axis echocardiographic view demonstrating a large circumferential pericardial effusion with tamponade physiology, demarcated by the asterisks. (B) Emergent pericardiocentesis was performed under fluoroscopy in the cardiac catheterization laboratory. The red arrow indicates a 6 French femoral Prelude® sheath (Merit Medical Systems Inc., South Jordan, UT, USA) with a 6 French Expo™ pigtail catheter (Boston Scientific, Marlborough, MA, USA) encircled in red. (C) The sub-xiphoid approach to pericardiocentesis was performed under fluoroscopic and ultrasound-guidance. The green circle indicates the implanted 6 French femoral Prelude sheath (Merit Medical Systems Inc.) attached to a 6 French Expo pigtail catheter (Boston Scientific, Marlborough, MA, USA). (D) Our technique involved connecting the pigtail catheter to a negative suction container encircled in green, which rapidly relieved the tamponade physiology and normalized the patient’s obstructive shock. This strategy removed voluminous pericardial fluid quickly (~460 mL within 5-10 minutes).

An emergent fluoroscopic- and ultrasound-guided sub-xiphoid pericardiocentesis was performed in the cardiac catheterization laboratory using a 6 French femoral Prelude® sheath (Merit Medical Systems Inc.) with a 6 French Expo™ pigtail catheter (Boston Scientific) connected to negative suction.14,15 Approximately 460 mL of straw-colored fluid was aspirated (Figure 1B-D).16,17 Subsequently, the patient’s hemodynamic status drastically improved with near-normalization, and the residual pericardial effusion significantly decreased with absent tamponade physiology. Routine laboratory investigations revealed pancytopenia with mildly deranged electrolytes and transaminitis. Inflammatory markers were elevated, and HIV parameters returned markedly abnormal. His tuberculosis screening test was normal. Pericardial fluid gram stain, acid-fast bacillus stain, fungal stain, bacterial culture, fungal culture, and cytology were negative (Table 1).

Table 1.

The Patient’s Diagnostic Investigations.

| Tests performed | Result | Reference range |

|---|---|---|

| Complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel | ||

| WCC | 2.8 × 109/L | 4.5-11.0 × 109/L |

| Hb | 9.1 g/dL | 14.0-17.5 g/dL |

| Platelet count | 110 × 103/µL | 156-373 × 103/µL |

| Serum potassium | 4.4 mmol/L | 3.5-5.1 mmol/L |

| Serum sodium | 134 mmol/L | 135-145 mmol/L |

| Serum Cr | 1.1 mg/dL | 0.5-1.2 mg/dL |

| BUN | 18 mg/dL | 3-20 mg/dL |

| Fasting blood sugar | 90 mg/dL | 60-120 mg/dL |

| ALT | 64 IU/L | 20-60 IU/L |

| AST | 48 IU/L | 5-40 IU/L |

| Total bilirubin | 1.3 mg/dL | 0.2-1.2 mg/dL |

| ALP | 112 U/L | 40-129 IU/L |

| Albumin | 3.5 g/dL | 3.5-5.5 g/dL |

| Albumin-corrected calcium | 10.1 mg/dL | 9.6-11.2 mg/dL |

| TSH | 2.4 uIU/mL | 0.35-4.954 uIU/mL |

| Vitamin B12 | 1360 pg/mL | 187-883 pg/mL |

| Folate | 8.1 ng/mL | 3.1-20.5 ng/mL |

| Ferritin | 618 ng/mL | 21.81-274.66 ng/mL |

| TIBC | 259 ug/dL | 134-415 ug/dL |

| Transferrin saturation | 29% | 14.2-58.4 % |

| Infectious diseases panel | ||

| ESR | 132 mm/h | 0-22 mm/h |

| CRP | 98 mg/dL | 0.0-1.0 mg/dL |

| Blood cultures | Negative | Positive or negative |

| Urine culture | Negative | Positive or negative |

| VDRL test | Non-reactive | Non-reactive or reactive |

| QuantiFERON-TB GOLD® (Cellestis Limited, Carnegie, Victoria, Australia) | Negative | Positive, negative or indeterminate |

| Hepatitis B surface antigen | Negative | Positive or negative |

| Hepatitis C virus antibody | Negative | Positive or negative |

| Mycoplasma IgM antibodies | Negative | Positive, low positive or negative |

| Mycoplasma IgG antibodies | Negative | Positive, equivocal or negative |

| Legionella pneumophilia antibodies (Types 1-6) Ig G, M, and A | Negative | Positive, equivocal or negative |

| Urine Legionella antigen | Negative | Negative |

| Toxoplasma gondii IgM antibodies | Not detected | Detected, indeterminate, not detected |

| Toxoplasma gondii IgG antibodies | Not detected | Detected, indeterminate, not detected |

| Cytomegalovirus antibody, IgG antibody | Not detected | Detected, indeterminate, not detected |

| Cytomegalovirus antibody, IgM antibody | Not detected | Detected, indeterminate, not detected |

| Histoplasma antigen quantitative EIA, urine | Detected (above the limit of quantification) | <0.2 ng/mL (quantification from 0.2-20 ng/mL) |

| Histoplasma galactomannan antigen quantitative EIA, serum | Detected (above the limit of quantification) | < 0.19 ng/mL (quantification from 0.19-60 ng/mL) |

| Cryptococcal antigen, serum | Negative | Negative |

| count | 82 cells/mm3 | 500-1500 cells/mm3 |

| HIV RNA | 288, 403 copies/µL | < 20 copies/µL |

| Immunologic and rheumatologic panel | ||

| ANA factor | Negative | Positive or negative |

| Anti-ds-DNA antibodies | < 30.0 U/mL | < 30.0 U/mL (negative) |

| C3 | 180 mg/dL | 83-193 mg/dL |

| C4 | 60 mg/dL | 15-75 mg/dL |

| Anti-CCP antibodies | < 20.0 U/mL | < 20.0 U (negative) |

| Rheumatoid factor | Negative | Positive or negative |

| Pericardial fluid analysis | ||

| White blood cells | 9.4 × 109/L (65% lymphocytes) | |

| Red blood cells | 4.1 × 109/L | |

| Lactate dehydrogenase | 1,185 U/L | |

| Glucose | 35 mg/dL | |

| Protein | 6.5 g/dL | |

| Gram stain | Negative | |

| Acid-fast bacilli stain | Negative | |

| Fungal stain and culture | Negative | |

| Bacterial culture | Negative | |

| Cytology | Negative | |

Abbreviations: ALP, alkaline phosphatase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; ANA, antinuclear; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; CCP, cyclic citrullinated peptide; CD4, cluster of differentiation 4; Cr, creatinine; CRP, C-reactive protein; DNA, deoxyribonucleic acid; DNA, deoxyribonucleic acid; EIA, enzyme immunoassay; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; Hb, hemoglobin; HIV RNA, human immunodeficiency virus ribonucleic acid; IgG, immunoglobulin G; IgM, immunoglobulin M; TIBC, total iron binding capacity; TSH, thyroid stimulating hormone; VDRL, Venereal Disease Research Laboratory; WCC, white cell count.

The patient was then transferred to the cardiac care unit postpericardiocentesis for the next 24 hours, where the pigtail catheter drainage gradually subsided (<10 mm/h) for a total drainage of 660 mL. He was de-escalated to the medical ward, where he underwent further extensive investigations, including a computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis, which revealed widespread cervical, supraclavicular, mediastinal, and abdominal lymphadenopathy suggestive of lymphoproliferative disease. The serum and urine Histoplasma antigen assay was positive, implying the diagnosis of DH (Table 1). The patient was initiated on guideline-directed medical therapy, including intravenous amphotericin B, followed by oral itraconazole for the treatment of DH by the infectious diseases (ID) team.19,20 Additionally, ART was commenced with raltegravir 400 mg twice daily and emtricitabine/tenofovir 200/300 mg once daily. The patient’s clinical course gradually improved, and repeat echocardiography revealed no interval accumulation of pericardial effusion. He was eventually discharged with scheduled appointments at the ID and cardiology outpatient clinics. The patient, at both his 3- and 6-month follow-up visits, reported feeling generally well with stringent adherence to his ART and no demonstrable pericardial effusion on his bedside, point-of-care echocardiography in the clinic.

Discussion

CT is a pericardial syndrome characterized by the compression of the heart chambers attributed to excessive fluid accumulation within the pericardial sac.18,19 This diastolic impairment attenuates cardiac output, often resulting in features of circulatory collapse with obstructive shock if not urgently addressed. 20 The predominant causes include percutaneous cardiac interventions, neoplasia, infectious or inflammatory diseases, mechanical complications of acute coronary syndromes, and aortic dissection. 21 The classical presentation often exhibits Beck’s triad, comprised of hypotension, jugular venous distension, and muffled heart sounds. 18 Additionally, patients may also present with dyspnea, angina and syncope. 22

The prevalence of histoplasmosis has been extensively reported in the Caribbean region, where it has been steadily increasing, especially among the immunocompromised subgroup.23-25 Cardiac histoplasmosis is an exceedingly rare condition that can be easily overlooked. 26 The pathophysiology involves the dispersion of Histoplasma organisms from the primary nidus, often the lungs, to the pericardium, where these pathogens incite an intense and complex inflammatory milieu, resulting in pericardial effusion. 27 Interleukin-1 (IL-1), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) play pivotal roles in amplifying inflammation and promoting granuloma formation. Interleukin-12 (IL-12) and interleukin-18 (IL-18) are critical for facilitating fungal clearance, primarily through the induction of interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) along with reactive oxygen and nitrogen species. 28 Chemokines such as CCL2 (MCP-1), CCL3 (MIP-1α), and CCL4 (MIP-1β) also augment the cellular immune response. 29 Conversely, interleukin-10 (IL-10) and transforming growth factor-beta modulate the inflammatory response to mitigate tissue necrosis. The formation of granulomas, a hallmark of the immune response to Histoplasma, is contingent on a multifaceted interplay among TNF-α, IFN-γ, and IL-12. 30 In some cases, the effusion progresses and exerts a profound hemodynamic effect, ultimately leading to CT. 31 Transthoracic echocardiography is the pivotal imaging modality for diagnosing and assessing tamponade physiology. Its capability to directly visualize the pericardial effusion, estimate its volume, and assess any impact on cardiac function provides critical clinical information. 13 Conversely, the definitive diagnosis of DH requires the identification of H. capsulatum organisms within the affected specimen, which is typically achieved through complementary microbiological and histopathological techniques. 32

A literature review revealed that DH presenting as CT is relatively rare, with fewer than 50 cases reported worldwide, and the preponderance of cases occurs in patients with compromised immunity or on immunosuppressant therapy.33-35 The prognosis for patients with DH presenting as CT is dependent on several factors, such as index time to diagnosis and intervention, the extent of dissemination, and the patient’s immune status. 36 Management of DH with CT requires a dual approach: emergent pericardiocentesis and targeted antifungal therapy. Amphotericin B is the therapy of choice for fulminant cases due to its broad spectrum of activity and fungicidal properties. 37 Following initial stabilization, patients are usually transitioned to oral itraconazole for at least 12 months for continued suppression and to prevent relapse.38,39

This case was interesting in several aspects. The patient and his family initially concealed his HIV/AIDS status for the first week of index presentation until his condition was confirmed with HIV RNA testing, after which they eventually acquiesced. This inevitably led to a brief delay in initiating his DH and HIV/AIDS antifungal and ART. The concealment of HIV status remains a burdensome public health challenge.40,41 This underscores the importance of maintaining a high index of suspicion for opportunistic infections in patients, especially those with HIV. 42 The patient also received guideline-directed therapies, both procedural and antifungal, with ART, for his DH-CT. Our unique practical modification was connecting the embedded pigtail catheter to a ground-level negative suction container, which permitted swift removal of the pericardial effusion (~460 mL within 5-10 minutes). This prevailing differential was clinched by his serum and urine Histoplasma antigen, which returned positive, as our local laboratory lacked the capability of testing on the pericardial aspirate, which we expected to be inflammatory in nature. Although definitive, no pericardial biopsy was performed to confirm the presence of Histoplasma or granuloma formation histologically, and thus, we relied on antigen testing in the clinical scenario.

The diagnosis of proven DH would rely on the recovery by culture of the fungus from specimens from the affected site, blood, histopathology, or direct microscopy of the specimens from an affected site. 43 Probable DH is supported by evidence of geographical or occupational exposure to fungus and compatible clinical illness, as well as Histoplasma antigen in urine, serum, or body fluid. 43 Our patient fulfilled the criteria for the latter, given the geographical reports of histoplasmosis in our region and the positive urine and serum Histoplasma antigens. He refused a bone marrow biopsy, and no pericardial biopsy was taken. Although culture remains a gold standard for diagnosis, it can take up to as long as 6 weeks to grow, and factors such as the burden of disease and specimen type can affect sensitivity.44-46 Although Arango-Bustamante et al found serological assays to be useful for the diagnosis of histoplasmosis in HIV/AIDS patients, they are not reported in the consensus definitions of DH disease by Donnelly et al. Our local laboratory lacked the capability of testing the pericardial fluid aspirate for Histoplasma; however, we expected the fluid to be inflammatory based on previous reports in the literature. 9 Secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) triggered by histoplasmosis is an uncommon disorder that is highly lethal in immunocompromised hosts such as patients with HIV/AIDS. 47 Elevated ferritin, cytopenias, and splenomegaly should prompt physicians to consider evaluation for HLH. Infection or sepsis, multiorgan dysfunction syndrome and liver disease are some conditions that can mimic these abnormalities, and HLH-2024 criteria can be used to establish the diagnosis of HLH. 48 Our patient’s ferritin was elevated, though not markedly elevated above 2000 ng/mL, but he did not have fever, splenomegaly, or cytopenia values in keeping with HLH criteria. His triglyceride levels were normal, but no fibrinogen levels were available. Clinicians can also use an H score to look at the probability of HLH. 49 Based on the parameters that were available for our patient, he had a low likelihood of HLH.

Conclusion

We describe a 57-year-old Caribbean-Black patient with a concealed medical history of HIV/AIDS who presented with CT secondary to disseminated histoplasmosis (DH). His management required a dual approach: emergent pericardiocentesis with targeted antifungal and ART. This case underscores the importance of maintaining a high index of suspicion for opportunistic infections in patients, especially those with HIV/AIDS.

Acknowledgments

None.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: All authors contributed equally to writing the manuscript, and all authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Data Sharing Statement: All available data can be obtained by contacting the corresponding author.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethics Approval: Our institution does not require ethical approval for reporting individual cases or case series.

Informed Consent: Written informed consent was obtained from the patient(s) for their anonymized information to be published in this article.

ORCID iDs: Arun Katwaroo  https://orcid.org/0009-0008-0401-1918

https://orcid.org/0009-0008-0401-1918

Naveen Seecheran  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7779-0181

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7779-0181

References

- 1. Edwards RJ, Boyce G, Alastruey-Izquierdo A, et al. Updated estimated incidence and prevalence of serious fungal infections in Trinidad and Tobago. IJID Reg. 2021;1:34-40. doi: 10.1016/j.ijregi.2021.09.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Denning DW, Gugnani HC. Burden of serious fungal infections in Trinidad and Tobago. Mycoses. 2015;58 Suppl 5:80-84. doi: 10.1111/myc.12394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dao A, Kim HY, Halliday CL, et al. Histoplasmosis: a systematic review to inform the World Health Organization of a fungal priority pathogens list. Med Mycol. 2024;62:myae039. doi: 10.1093/mmy/myae039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Araúz AB, Papineni P. Histoplasmosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2021;35:471-491. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2021.03.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Azar MM, Malo J, Hage CA. Endemic fungi presenting as community-acquired pneumonia: a review. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;41:522-537. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1702194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tobón AM, Gómez BL. Pulmonary histoplasmosis. Mycopathologia. 2021;186: 697-705. doi: 10.1007/s11046-021-00588-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ramos-Ospina N, Carolina Lambertinez-Álvarez I, Johanna Hurtado-Bermúdez L, et al. Management of disseminated histoplasmosis in a high-complexity clinic in Cali, Colombia. Med Mycol. 2024;62:myae058. doi: 10.1093/mmy/myae058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Toscanini MA, Nusblat AD, Cuestas ML. Diagnosis of histoplasmosis: current status and perspectives. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2021;105:1837-1859. doi: 10.1007/s00253-021-11170-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yeates AC, Quimby DS. Histoplasmosis causing overt inflammation presenting as pericarditis: a case report. Cureus. 2024;16:e59512. doi: 10.7759/cureus.59512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sansom S, Shah A, Hussain S, et al. Histoplasma capsulatum: an unusual case of pericardial effusion and coarctation of the aorta. J Clin Med Res. 2016;8:254-256. doi: 10.14740/jocmr2455w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jawahar AP, Thattaliyath B, Badheka A, et al. Histoplasma associated pericarditis with pericardial tamponade in a child. BMJ Case Rep. 2023;16:e256265. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2023-256265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Alerhand S, Carter JM. What echocardiographic findings suggest that a pericardial effusion is causing tamponade? Am J Emerg Med. 2019;37:321-326. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2018.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kearns MJ, Walley KR. Tamponade: hemodynamic and echocardiographic diagnosis. Chest. 2018;153:1266-1275. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2017.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Luis SA, Kane GC, Luis CR, et al. Overview of optimal techniques for pericardiocentesis in contemporary practice. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2020;22:60. doi: 10.1007/s11886-020-01324-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sinnaeve PR, Adriaenssens T. A contemporary look at pericardiocentesis. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2019;29:375-383. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2018.10.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Willner DA, Grossman SA. Pericardiocentesis. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2025. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. De Carlini CC, Maggiolini S. Pericardiocentesis in cardiac tamponade: indications and practical aspects https://www.escardio.org/Journals/E-Journal-of-Cardiology-Practice/Volume-15/Pericardiocentesis-in-cardiac-tamponade-indications-and-practical-aspects (2017, accessed 3 February 2025).

- 18. Adler Y, Ristić AD, Imazio M, et al. Cardiac tamponade. Nat Rev Dis Primer. 2023;9:36. doi: 10.1038/s41572-023-00446-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Al-Ogaili A, Ayoub A, Fugar S, et al. Cardiac Tamponade incidence, demographics and in-hospital outcomes: analysis of the National Inpatient Sample Database. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71:A1155. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(18)31696-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Yuriditsky E, Horowitz JM. The physiology of cardiac tamponade and implications for patient management. J Crit Care. 2024;80:154512. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2023.154512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Imazio M, De Ferrari GM. Cardiac tamponade: an educational review. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2021;10:102-109. doi: 10.1177/2048872620939341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hoit BD. Pericardial effusion and cardiac tamponade in the New Millennium. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2017;19:57. doi: 10.1007/s11886-017-0867-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rodrigues AM, Beale MA, Hagen F, et al. The global epidemiology of emerging Histoplasma species in recent years. Stud Mycol. 2020;97:100095. doi: 10.1016/j.simyco.2020.02.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gousy N, Adithya Sateesh B, Denning DW, et al. Fungal infections in the Caribbean: a review of the literature to date. J Fungi Basel Switz. 2023;9:1177. doi: 10.3390/jof9121177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Falci DR, Pasqualotto AC. Clinical mycology in Latin America and the Caribbean: a snapshot of diagnostic and therapeutic capabilities. Mycoses. 2019;62:368-373. doi: 10.1111/myc.12890 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Shaker N, Amadi CC, Ganapathi AM, et al. Pulmonary histoplasmosis complicated by nonvalvular right ventricular wall histoplasma capsulatum endocarditis. Int J Surg Pathol. 2024;32:565-569. doi: 10.1177/10668969231185079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Soriano PK, Iqbal M, Kandaswamy S, Akram S, Kulkarni A, Hudali T. H. capsulatum: a Not-so-benign cause of pericarditis. Case Rep Cardiol. 2017;2017:3626917. doi: 10.1155/2017/3626917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lin J-S, Wu-Hsieh BA. Functional T cells in primary immune response to histoplasmosis. Int Immunol. 2004;16(11):1663-1673. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxh168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Horwath MC, Fecher RA, Deepe GS. Histoplasma capsulatum, lung infection and immunity. Future Microbiol. 2015;10:967-975. doi: 10.2217/fmb.15.25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mittal J, Ponce MG, Gendlina I, Nosanchuk JD. Histoplasma capsulatum: mechanisms for pathogenesis. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2019;422:157-191. doi: 10.1007/82_2018_114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kalian K, Gastelum AA, Marquez-Lavenant W, et al. A case of histoplasma pericarditis with Tamponade. Chest. 2020;158:A486. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.08.466 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pan American Health Organization. Guidelines for Diagnosing and Managing Disseminated Histoplasmosis Among People Living With HIV. Pan American Health Organization; 2020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lind A, Reinsch N, Neuhaus K, et al. Pericardial effusion of HIV-infected patients ? Results of a prospective multicenter cohort study in the era of antiretroviral therapy. Eur J Med Res. 2011;16:480-483. doi: 10.1186/2047-783x-16-11-480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kumar P, Arendt C, Martin S, et al. Multimodality imaging in HIV-associated cardiovascular complications: a comprehensive review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20:2201. doi: 10.3390/ijerph20032201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sud K, Argulian E. Echocardiography in patients with HIV infection. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2020;22:100. doi: 10.1007/s11886-020-01347-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. McKinsey DS. Treatment and prevention of histoplasmosis in adults living with HIV. J Fungi. 2021;7:429. doi: 10.3390/jof7060429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sekiguchi WK, de Oliveira VF, Cavassin FB, et al. A multicentre study of amphotericin B treatment for histoplasmosis: assessing mortality rates and adverse events. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2024;79:2598-2606. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkae264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wheat LJ, Freifeld AG, Kleiman MB, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of patients with histoplasmosis: 2007 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis Off Publ Infect Dis Soc Am. 2007;45:807-825. doi: 10.1086/521259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mazi PB, Arnold SR, Baddley JW, et al. Management of histoplasmosis by infectious disease physicians. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2022;9:ofac313. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofac313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Smith R, Rossetto K, Peterson BL. A meta-analysis of disclosure of one’s HIV-positive status, stigma and social support. AIDS Care. 2008;20:1266-1275. doi: 10.1080/09540120801926977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Katz IT, Ryu AE, Onuegbu AG, et al. Impact of HIV-related stigma on treatment adherence: systematic review and meta-synthesis. J Int AIDS Soc. 2013;16:18640. doi: 10.7448/IAS.16.3.18640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Myint T, Leedy N, Villacorta Cari E, et al. HIV-associated histoplasmosis: current perspectives. HIVAIDS Auckl NZ. 2020;12:113-125. doi: 10.2147/HIV.S185631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Donnelly JP, Chen SC, Kauffman CA, et al. Revision and update of the consensus definitions of invasive fungal disease from the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer and the Mycoses Study Group Education and Research Consortium. Clin Infect Dis Off Publ Infect Dis Soc Am. 2020;71:1367-1376. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciz1008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Couppié P, Aznar C, Carme B, Nacher M. American histoplasmosis in developing countries with a special focus on patients with HIV: diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2006;19:443-449. doi: 10.1097/01.qco.0000244049.15888.b9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Baddley JW, Sankara IR, Rodriquez JM, Pappas PG, Many Jr., WJ. Histoplasmosis in HIV-infected patients in a southern regional medical center: poor prognosis in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2008;62:151-156. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2008.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Arango-Bustamante K, Restrepo A, Cano LE, de Bedout C, Tobón AM, González A. Diagnostic value of culture and serological tests in the diagnosis of histoplasmosis in HIV and non-HIV Colombian patients. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2013;89:937-942. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.13-0117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Townsend JL, Shanbhag S, Hancock J, Bowman K, Nijhawan AE. Histoplasmosis-induced Hemophagocytic Syndrome: a case series and review of the literature. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2015;2:ofv055. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofv055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Henter J-I. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. N Engl J Med. 2025;392:584-598. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra2314005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Fardet L, Galicier L, Lambotte O, et al. Development and validation of the HScore, a score for the diagnosis of reactive hemophagocytic syndrome. Arthritis Rheumatol 2014;66:2613-2620. doi: 10.1002/art.38690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]