Abstract

We present a genome assembly from an individual Crambe crambe (Porifera; Demospongiae; Poecilosclerida; Crambeidae). The host genome sequence is 143.20 megabases in span. Most of the assembly is scaffolded into 18 chromosomal pseudomolecules. The mitochondrial genome has also been assembled and is 19.53 kilobases in length. Several symbiotic prokaryotic genomes were assembled as MAGs, including two relevant sponge symbionts, the Candidatus Beroebacter blanensis/ AqS2 clade (Tethybacterales, Gammaproteobacteria) of LMA sponges, and the widely distributed archaeal Nitrosopumilus sp. clade.

Keywords: Crambe crambe, marine sponge, genome sequence, chromosomal, Poecilosclerida

Species taxonomy

Eukaryota; Opisthokonta; Metazoa; Porifera; Demospongiae; Heteroscleromorpha; Poecilosclerida; Crambeidae; Crambe (in: sponges) Crambe; Crambe crambe Vosmaer, 1880 (NCBI:txid3722).

Background

Crambe crambe ( Schmidt, 1862) is probably the most abundant sponge species in the sublittoral rocky bottoms of the Atlantic-Mediterranean region. It is a bright red encrusting sponge that grows at both well-lit and poorly lit sites, forming patches of up to 0.5 m 2 ( Pansini & Pronzato, 1990; Turon et al., 1998). As additional macroscopic clues for species identification, oscula and their radially converging excurrent channels are often visible on the sponge surface, which is slippery to the touch. The sponge grows not only on rocks, but also on barnacles and on the shells of the red oyster Spondylus gaederopus.

Due to its abundance, the species is ecologically important in many ways. For instance, its skeletal growth represents a substantial silicon sink for the sublittoral system ( Maldonado et al., 2005). The sponge also provides food and habitat for a variety of marine organisms, including recruitment habitat for juvenile ophiuroids ( Turon et al., 2000) and small benthic fish. C. crambe produces various bioactive compounds that interact chemically with many community members ( Becerro et al., 1994; Becerro et al., 1997), some of which have potential pharmaceutical applications derived from their antibacterial, antifungal, and anti-tumour properties, among others ( El-Demerdash et al., 2018). Given its biotechnological potential, attempts have been made to farm the species ( Padiglia et al., 2018). Despite its abundance and ecological versatility (or perhaps because of it), the species is thought to be a surviving relict of the Jurassic oceans. This hypothesis is supported by the observation that the formation of all four spicule types is only possible at a silicate concentration ≥100 µM – concentrations which are likely to have occurred in Jurassic seas before the ecological expansion of diatoms ( Maldonado et al., 1999). Secondly, the biogeographic distribution of the genus Crambe shows a clear Tethyan pattern ( Maldonado et al., 2001).

Regarding the microbiome, the sponge is a species with low microbial abundance. While most of the few microbes occur in low abundance extracellularly in the mesohyl and around the skeletal spongin fibres, some of the microbes have been documented by electron microscopy to be contained within vesicles in the cytoplasm of bacteriocytes that appear to contain a single microbial species per cell ( Carrier et al., 2022; Maldonado, 2007). Gammaproteobacteria, ammonia-oxidising Nitrosopumilus sp. (Archaea) and a single taxon, Candidatus Beroebacter blanensis, dominate the microbial community . This latter symbiont clade appears to be vertically transmitted ( Turon et al., 2024). It was originally classified as Betaproteobacteria ( Croué et al., 2013), but was later identified as Ca. Beroebacter blanensis, belonging to a novel bacterial order, Candidatus ( Ca.) Tethybacterales within the Gammaproteobacteria and consisting mainly of sponge symbionts ( Taylor et al., 2021). The well characterized symbiont “AqS2” of Amphimedon queenslandica is the nearest phylogenetic relative of the B. blanensis clade, which displays genome reduction and limited metabolic capabilities, likely reflecting an adaptation to a symbiotic lifestyle within the sponge host ( Gauthier et al., 2016).

The sexual condition of the species is hermaphroditism. It is worth noting that its spermatozoa are highly atypical within the phylum. They are very elongated and V-shaped, with the flagellum inserted in an antero-lateral position next to a true acrosome ( Riesgo & Maldonado, 2009; Tripepi et al., 1984). This general organisation of the spermatozoon, which closely resembles that of Phoronida spermatozoa, appears to be common in the order Poecilosclerida but not in other sponges. Fertilisation is internal, and embryos are incubated for several months, until they develop into bright red, non-tufted parenchymella larvae ( Maldonado & Bergquist, 2002; Uriz et al., 2001). In western Mediterranean populations, larval release extends from mid-July to mid-August, and larval production can be as high as 76 embryos per cm 2 of sponge tissue ( Uriz et al., 1998), which would explain the abundance of adults.

The sequencing of the whole-chromosome genome of C. crambe will facilitate in-depth understanding of the genomic basis of this species biology, as well as its ecology and evolution. This genome will be particularly useful for investigating the evolution of sexual strategies in Demospongiae, as well as for clarifying between-family relationships within the order Poecilosclerida. Together with the genome sequences of C. crambe microbial symbionts presented here, the novel data will enable targeted examination of the molecular basis of sponge silicate metabolism and skeleton formation, alkaloid metabolism, and sponge-microbe interactions in the role of carbon cycling, among other key questions in sponge symbiosis.

Genome sequence report

The genome was sequenced from an adult Crambe crambe ( Figure 1) collected from Blanes, Girona, Spain. A total of 459-fold coverage in Pacific Biosciences single-molecule HiFi long reads was generated. Primary assembly contigs were scaffolded with chromosome conformation Hi-C data. Manual assembly curation corrected 62 missing joins or mis-joins and removed 18 haplotypic duplications, reducing the assembly length by 2.19% and the scaffold number by 29.78%, also decreasing the scaffold N50 by 0.31%.

Figure 1. Photograph of the Crambe crambe (odCraCram1) specimen used for genome sequencing.

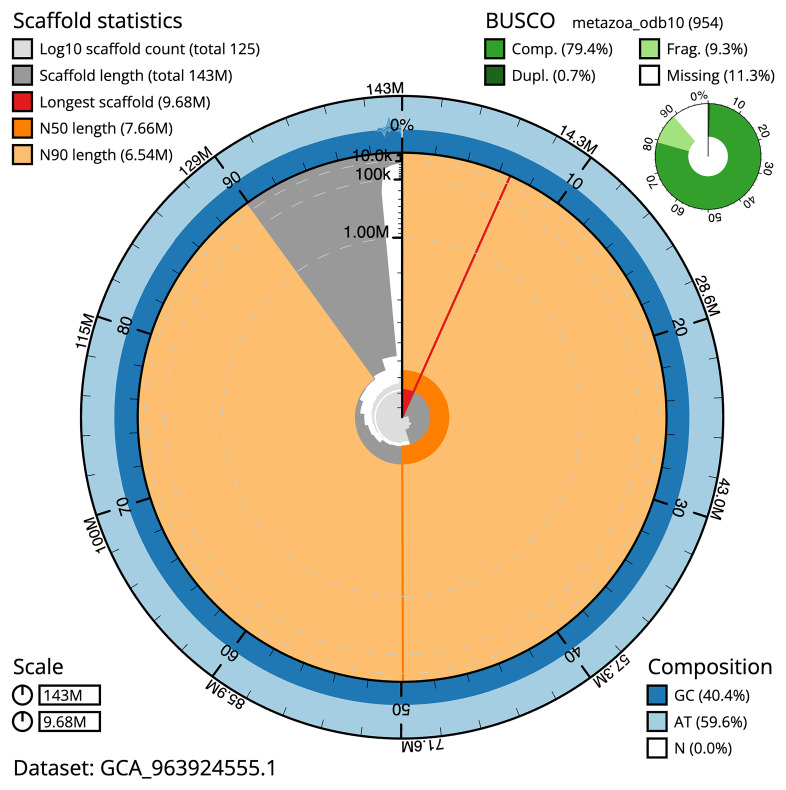

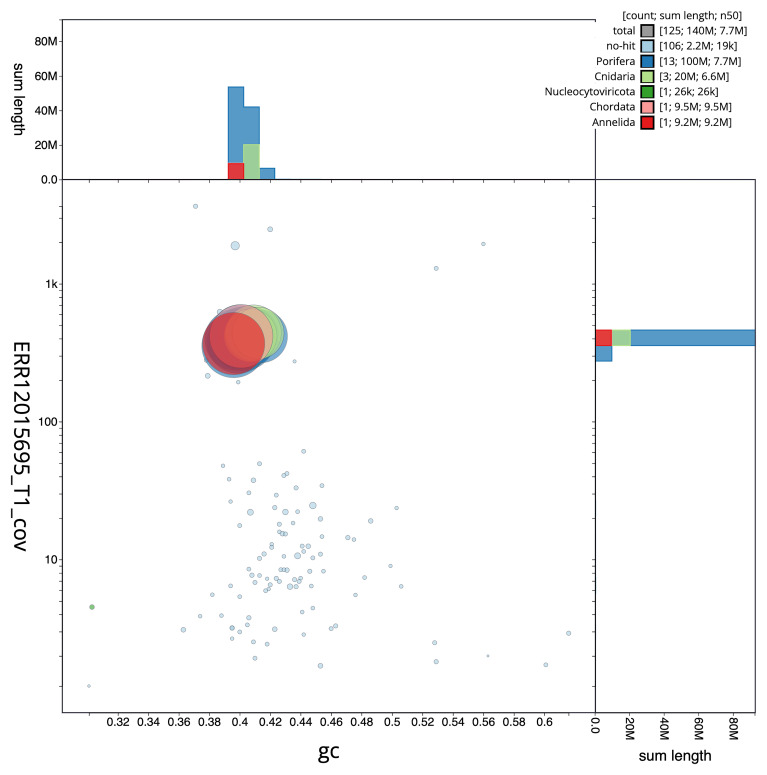

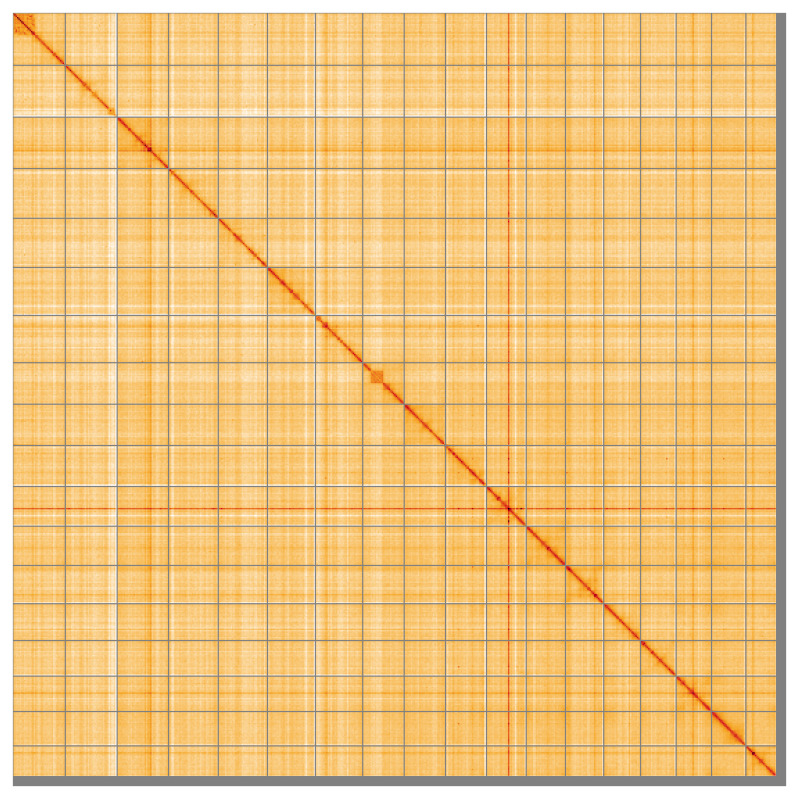

The final assembly has a total length of 143.20 Mb in 124 sequence scaffolds with a scaffold N50 of 7.7 Mb ( Table 1). The snail plot in Figure 2 provides a summary of the assembly statistics, while the distribution of assembly scaffolds on GC proportion and coverage is shown in Figure 3. The cumulative assembly plot in Figure 4 shows curves for subsets of scaffolds assigned to different phyla. Most (98.69%) of the assembly sequence was assigned to 18 chromosomal-level scaffolds. Chromosome-scale scaffolds confirmed by the Hi-C data are named in order of size ( Figure 5; Table 2). While not fully phased, the assembly deposited is of one haplotype. Contigs corresponding to the second haplotype have also been deposited. The mitochondrial genome was also assembled and can be found as a contig within the multifasta file of the genome submission.

Figure 2. Genome assembly of Crambe crambe, odCraCram1.1: metrics.

The BlobToolKit Snailplot shows N50 metrics and BUSCO gene completeness. The main plot is divided into 1,000 size-ordered bins around the circumference with each bin representing 0.1% of the 143,197,480 bp assembly. The distribution of scaffold lengths is shown in dark grey with the plot radius scaled to the longest scaffold present in the assembly (9,683,886 bp, shown in red). Orange and pale-orange arcs show the N50 and N90 scaffold lengths (7,656,483 and 6,535,638 bp), respectively. The pale grey spiral shows the cumulative scaffold count on a log scale with white scale lines showing successive orders of magnitude. The blue and pale-blue area around the outside of the plot shows the distribution of GC, AT and N percentages in the same bins as the inner plot. A summary of complete, fragmented, duplicated and missing BUSCO genes in the metazoa_odb10 set is shown in the top right. An interactive version of this figure is available at https://blobtoolkit.genomehubs.org/view/Crambe_crambe/dataset/GCA_963924555.1/snail.

Figure 3. Genome assembly of Crambe crambe, odCraCram1.1: BlobToolKit GC-coverage plot.

Scaffolds are coloured by phylum. Circles are sized in proportion to scaffold length. Histograms show the distribution of scaffold length sum along each axis. An interactive version of this figure is available at https://blobtoolkit.genomehubs.org/view/Crambe_crambe/dataset/GCA_963924555.1/blob.

Figure 4. Genome assembly of Crambe crambe, odCraCram1.1: BlobToolKit cumulative sequence plot.

The grey line shows cumulative length for all scaffolds. Coloured lines show cumulative lengths of scaffolds assigned to each phylum using the buscogenes taxrule. An interactive version of this figure is available at https://blobtoolkit.genomehubs.org/view/Crambe_crambe/dataset/GCA_963924555.1/cumulative.

Figure 5. Genome assembly of Crambe crambe, odCraCram1.1: Hi-C contact map of the odCraCram1.1 assembly, visualised using HiGlass.

Chromosomes are shown in order of size from left to right and top to bottom. An interactive version of this figure may be viewed at https://genome-note-higlass.tol.sanger.ac.uk/l/?d=IeGb4iyXTOqWeiUVkpdMrA.

Table 1. Genome data for Crambe crambe, odCraCram1.1.

| Project accession data | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Assembly identifier | odCraCram1.1 | ||

| Species | Crambe crambe | ||

| Specimen | odCraCram1 | ||

| NCBI taxonomy ID | 3722 | ||

| BioProject | PRJEB65618 | ||

| BioSample ID | Genome sequencing: SAMEA9361910

Hi-C scaffolding: SAMEA9361908 |

||

| Isolate information | odCraCram1: (genome and Hi-C sequencing) | ||

| Assembly metrics | |||

| Consensus quality (QV) | 58.1 | ||

| BUSCO * | C:78.8%[S:78.0%,D:0.8%],F:9.4%,M:11.8%,n:954 | ||

| Percentage of assembly mapped

to chromosomes |

98.69% | ||

| Organelles | Mitochondrial genome: 19.53 kb | ||

| Sequencing information | |||

| Platform | Run accession | Read count | Base count (Gb) |

| Hi-C Illumina NovaSeq 6000 | ERR12512721 | 1.13e+09 | 170.77 |

| PacBio Revio | ERR12015695 | 9.82e+06 | 67.94 |

| Genome assembly | |||

| Assembly accession | GCA_963924555.1 | ||

| Accession of alternate haplotype | GCA_963924525.1 | ||

| Span (Mb) | 143.20 | ||

| Number of contigs | 178 | ||

| Contig N50 length (Mb) | 3.5 | ||

| Number of scaffolds | 124 | ||

| Scaffold N50 length (Mb) | 7.7 | ||

| Longest scaffold (Mb) | 9.77 | ||

* BUSCO scores based on the metazoa_odb10 BUSCO set using version 5.4.3. C = complete [S = single copy, D = duplicated], F = fragmented, M = missing, n = number of orthologues in comparison. A full set of BUSCO scores is available at https://blobtoolkit.genomehubs.org/view/Crambe_crambe/dataset/GCA_963924555.1/busco.

Table 2. Chromosomal pseudomolecules in the genome assembly of Crambe crambe, odCraCram1.

| INSDC

accession |

Name | Length

(Mb) |

GC% |

|---|---|---|---|

| OZ004581.1 | 1 | 9.57 | 39.5 |

| OZ004582.1 | 2 | 9.68 | 40.0 |

| OZ004583.1 | 3 | 9.49 | 40.0 |

| OZ004584.1 | 4 | 9.08 | 40.0 |

| OZ004585.1 | 5 | 9.18 | 39.5 |

| OZ004586.1 | 6 | 8.84 | 40.0 |

| OZ004587.1 | 7 | 8.73 | 39.5 |

| OZ004588.1 | 8 | 7.66 | 40.0 |

| OZ004589.1 | 9 | 7.63 | 40.5 |

| OZ004590.1 | 10 | 7.57 | 40.5 |

| OZ004591.1 | 11 | 7.33 | 40.5 |

| OZ004592.1 | 12 | 7.24 | 41.0 |

| OZ004593.1 | 13 | 7.06 | 40.5 |

| OZ004594.1 | 14 | 6.8 | 40.5 |

| OZ004595.1 | 15 | 6.57 | 40.5 |

| OZ004596.1 | 16 | 6.54 | 41.5 |

| OZ004597.1 | 17 | 6.34 | 41.0 |

| OZ004598.1 | 18 | 5.67 | 40.5 |

| OZ004599.1 | MT | 0.02 | 37.0 |

The estimated Quality Value (QV) of the final assembly is 58.1. The assembly has a BUSCO v5.4.3 completeness of 78.8% (single = 78.0%, duplicated = 0.8%), using the metazoa_odb10 reference set ( n = 954).

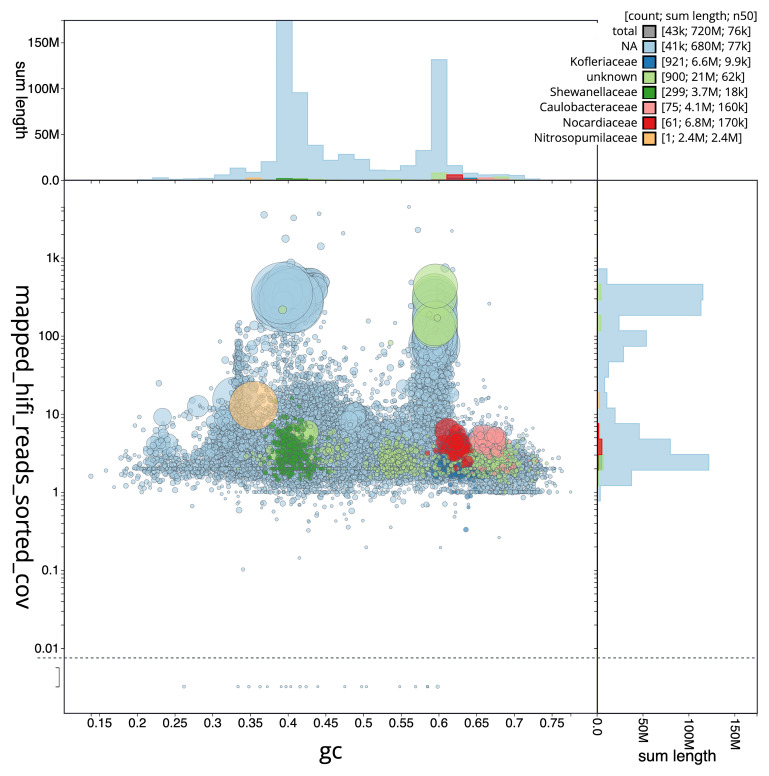

Metagenome report

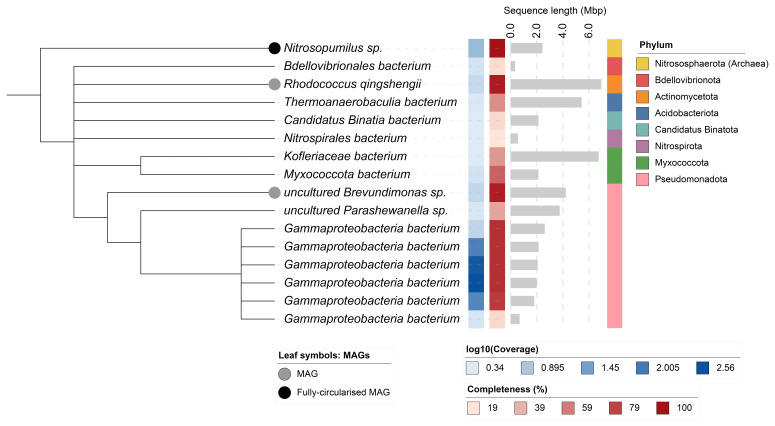

Sixteen binned genomes were generated from the metagenome assembly ( Figure 6), of which three were classified as high-quality metagenome assembled genomes (MAGs) (see methods). The completeness values for these assemblies range from approximately 20% to 100% with contamination below 7%. A cladogram of the binned metagenomes is shown in Figure 7. For details on binned genomes see Table 3.

Figure 6. Blob plot of base coverage in mapped against GC proportion for sequences in the metagenome of Crambe crambe.

Binned metagenomes are coloured by family. Circles are sized in proportion to sequence length on a square root scale, ranging from 501 to 4,126,685. Histograms show the distribution of sequence length sum along each axis An interactive version of this figure may be viewed here.

Figure 7. Cladogram showing the taxonomic placement of metagenome bins, constructed using NCBI taxonomic identifiers with taxonomizr and annotated in iTOL.

Colours indicate phylum-level taxonomy. Additional tracks show sequencing coverage (log₁₀), estimated genome size (Mbp), and completeness. Bins that meet the criteria for MAGs are marked with a grey circle; the single fully circularised MAG is marked in black.

Table 3. Quality metrics and taxonomic assignments of the binned metagenomes.

| NCBI taxon | Taxid | GTDB taxonomy | Quality | Size (bp) | Contigs | Circular | Mean

coverage |

Completeness

(%) |

Contamination

(%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nitrosopumilus sp. | 2024843 | g__Nitrosopumilus | High | 2,406,465 | 1 | Yes | 11.72 | 100.00 | 0.00 |

| uncultured

Brevundimonas sp. |

213418 | g__Brevundimonas | High | 4,185,465 | 75 | Partial | 4.39 | 95.06 | 4.27 |

| Rhodococcus qingshengii | 334542 | s__Rhodococcus

qingshengii |

High | 6,934,702 | 61 | No | 4.2 | 95.58 | 0.00 |

| Gammaproteobacteria

bacterium |

1913989 | f__AqS2 | Medium | 1,777,560 | 2 | No | 61.05 | 83.22 | 1.22 |

| Gammaproteobacteria

bacterium |

1913989 | f__AqS2 | Medium | 1,964,849 | 1 | Yes | 364.77 | 87.49 | 0.61 |

| Gammaproteobacteria

bacterium |

1913989 | f__AqS2 | Medium | 2,039,060 | 1 | Yes | 278.56 | 87.49 | 0.61 |

| Myxococcota bacterium | 2818507 | f__UBA6930 | Medium | 2,090,974 | 133 | No | 3.11 | 69.12 | 6.72 |

| Gammaproteobacteria

bacterium |

1913989 | f__AqS2 | Medium | 2,109,981 | 4 | No | 74.99 | 87.49 | 1.83 |

| Gammaproteobacteria

bacterium |

1913989 | g__UBA1858 | Medium | 2,576,596 | 26 | No | 4.79 | 87.52 | 1.97 |

| Thermoanaerobaculia

bacterium |

2651171 | f__UBA5704 | Medium | 5,408,624 | 319 | No | 2.54 | 52.97 | 1.44 |

| Bdellovibrionales

bacterium |

2053517 | g__JACOND01 | Low | 314,367 | 16 | No | 2.89 | 23.10 | 0.00 |

| Nitrospirales bacterium | 2358460 | g__Bin75 | Low | 524,459 | 58 | No | 2.22 | 19.47 | 0.00 |

| Gammaproteobacteria

bacterium |

1913989 | g__UBA1858 | Low | 655,358 | 63 | No | 2.67 | 24.99% | 1.77% |

| Candidatus Binatia

bacterium |

2838779 | g__JAAXHF01 | Low | 2,103,514 | 277 | No | 2.23 | 24.60% | 0.00% |

| uncultured

Parashewanella sp. |

2547967 | g__Parashewanella | Low | 3,728,522 | 299 | Partial | 2.61 | 43.78% | 5.25% |

| Kofleriaceae bacterium | 2212474 | f__Haliangiaceae | Low | 6,724,497 | 921 | Partial | 2.17 | 48.48% | 5.11% |

Methods

Sample acquisition

A specimen of Crambe crambe (specimen ID GHC0000181, ToLID odCraCram1) was collected from Blanes, Girona, Spain (latitude 41.67, longitude 2.80) on 2021-02-01 by SCUBA diving. The specimen was collected and identified by Manuel Maldonado (CEAB-CSIC) and preserved by snap-freezing.

Nucleic acid extraction

The workflow for high molecular weight (HMW) DNA extraction at the Wellcome Sanger Institute (WSI) Tree of Life Core Laboratory includes a sequence of core procedures: sample preparation; sample homogenisation, DNA extraction, fragmentation, and clean-up. Protocols are available on protocols.io ( Denton et al., 2023). In sample preparation, the odCraCram1 sample was weighed and dissected on dry ice ( Jay et al., 2023). Prior to DNA extraction, the sponge sample was bathed in “L buffer” (10 mM Tris, pH 7.6, 100 mM EDTA, 20 mM NaCl), minced into small pieces using a scalpel and the cellular interior separated from the mesohyl using forceps ( Lopez, 2022). HMW DNA was extracted using the Manual MagAttract v1 protocol ( Strickland et al., 2023b). DNA was sheared into an average fragment size of 12–20 kb in a Megaruptor 3 system ( Todorovic et al., 2023). Sheared DNA was purified by solid-phase reversible immobilisation ( Strickland et al., 2023a), using AMPure PB beads to eliminate shorter fragments and concentrate the DNA. The concentration of the sheared and purified DNA was assessed using a Nanodrop spectrophotometer, Qubit Fluorometer and Qubit dsDNA High Sensitivity Assay kit. Fragment size distribution was evaluated by running the sample on the FemtoPulse system.

Sequencing

Pacific Biosciences HiFi circular consensus DNA sequencing libraries were constructed according to the manufacturers’ instructions. DNA sequencing was performed by the Scientific Operations core at the WSI on a Pacific Biosciences Revio instrument. Hi-C data were also generated from tissue of odCraCram1 using the Arima2 kit and sequenced on the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 instrument.

Host genome assembly and curation

Assembly was carried out with Hifiasm ( Cheng et al., 2021) and haplotypic duplication was identified and removed with purge_dups ( Guan et al., 2020). The assembly was then scaffolded with Hi-C data ( Rao et al., 2014) using YaHS ( Zhou et al., 2023). The mitochondrial genome was assembled using MitoHiFi ( Uliano-Silva et al., 2023), which runs MitoFinder ( Allio et al., 2020) and uses these annotations to select the final mitochondrial contig and to ensure the general quality of the sequence. Table 4 contains a list of relevant software tool versions and sources.

Table 4. Software tools: versions and sources.

The assembly was checked for contamination and corrected using the TreeVal pipeline ( Pointon et al., 2023). Manual curation was primarily conducted using PretextView ( Harry, 2022), with additional insights provided by JBrowse2 ( Diesh et al., 2023) and HiGlass ( Kerpedjiev et al., 2018). Any identified contamination, missed joins, and mis-joins were corrected, and duplicate sequences were tagged and removed. The curation process is documented at https://gitlab.com/wtsi-grit/rapid-curation.

Taxonomic verification

Molecular markers obtained from the assembly were used to reconstruct the phylogenetic position of the sample. In an alignment using MAFFT v7.450 ( Katoh & Standley, 2013), the COI barcoding fragment (“Folmer” fragment) of the sample was found to be identical to haplotype 1 from a dedicated study on Crambe crambe ( Duran et al., 2004, AF526297), besides samples from other studies on this species as published in NCBI Genbank.

Host assembly quality assessment

The Merqury.FK tool ( Rhie et al., 2020), run in a Singularity container ( Kurtzer et al., 2017), was used to evaluate k-mer completeness and assembly quality for the primary and alternate haplotypes using the k-mer databases ( k = 31) that were computed prior to genome assembly. The analysis outputs included assembly QV scores and completeness statistics.

A Hi-C contact map was produced for the final version of the assembly. The Hi-C reads were aligned using bwa-mem2 ( Vasimuddin et al., 2019) and the alignment files were combined using SAMtools ( Danecek et al., 2021). The Hi-C alignments were converted into a contact map using BEDTools ( Quinlan & Hall, 2010) and the Cooler tool suite ( Abdennur & Mirny, 2020). The contact map is visualised in HiGlass ( Kerpedjiev et al., 2018).

The blobtoolkit pipeline is a Nextflow port of the previous Snakemake Blobtoolkit pipeline ( Challis et al., 2020). It aligns the PacBio reads in SAMtools and minimap2 ( Li, 2018) and generates coverage tracks for regions of fixed size. In parallel, it queries the GoaT database ( Challis et al., 2023) to identify all matching BUSCO lineages to run BUSCO ( Manni et al., 2021). For the three domain-level BUSCO lineages, the pipeline aligns the BUSCO genes to the UniProt Reference Proteomes database ( Bateman et al., 2023) with DIAMOND blastp ( Buchfink et al., 2021). The genome is also divided into chunks according to the density of the BUSCO genes from the closest taxonomic lineage, and each chunk is aligned to the UniProt Reference Proteomes database using DIAMOND blastx. Genome sequences without a hit are chunked using seqtk and aligned to the NT database with blastn ( Altschul et al., 1990). The blobtools suite combines all these outputs into a blobdir for visualisation.

The blobtoolkit pipeline was developed using nf-core tooling ( Ewels et al., 2020) and MultiQC ( Ewels et al., 2016), relying on the Conda package manager, the Bioconda initiative ( Grüning et al., 2018), the Biocontainers infrastructure ( da Veiga Leprevost et al., 2017), as well as the Docker ( Merkel, 2014) and Singularity ( Kurtzer et al., 2017) containerisation solutions.

Metagenome assembly

The metagenome assembly was generated using metaMDBG ( Benoit et al., 2024) and binned using MetaBAT2 ( Kang et al., 2019), MaxBin ( Wu et al., 2014), bin3C ( DeMaere & Darling, 2019), and MetaTOR. The resulting bin sets of each binning algorithm were optimised and refined using DAS Tool ( Sieber et al., 2018). PROKKA ( Seemann, 2014) was used to identify tRNAs and rRNAs in each bin, CheckM ( Parks et al., 2015) (checkM_DB release 2015-01-16) was used to assess bin completeness/contamination, and GTDB-TK ( Chaumeil et al., 2022) (GTDB release 214) was used to taxonomically classify bins. Taxonomic replicate bins were identified using dRep ( Olm et al., 2017), with default settings (95% ANI threshold). The final bin set was filtered for bacteria and archaea. All bins were assessed for quality and categorised as metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) if they met the following criteria: contamination ≤ 5%, presence of 5S, 16S, and 23S rRNA genes, at least 18 unique tRNAs, and either ≥ 90% completeness or ≥ 50% completeness with fully circularised chromosomes. Bins that did not meet these thresholds, or were identified as taxonomic replicates of MAGs, were retained as ‘binned metagenomes’ provided they had ≥ 50% completeness and ≤ 10% contamination. A cladogram based on NCBI taxonomic assignments was generated using the ‘taxonomizr’ package in R. The tree was visualised and annotated using iTOL ( Letunic & Bork, 2024). Software tool versions and sources are given in Table 4.

Wellcome Sanger Institute – Legal and Governance

The materials that have contributed to this genome note have been supplied by a Tree of Life collaborator. The Wellcome Sanger Institute employs a process whereby due diligence is carried out proportionate to the nature of the materials themselves, and the circumstances under which they have been/are to be collected and provided for use. The purpose of this is to address and mitigate any potential legal and/or ethical implications of receipt and use of the materials as part of the research project, and to ensure that in doing so we align with best practice wherever possible. The overarching areas of consideration are:

• Ethical review of provenance and sourcing of the material

• Legality of collection, transfer and use (national and international)

Each transfer of samples is undertaken according to a Research Collaboration Agreement or Material Transfer Agreement entered into by the Tree of Life collaborator, Genome Research Limited (operating as the Wellcome Sanger Institute) and in some circumstances other Tree of Life collaborators.

Funding Statement

This work was funded by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation through a grant (GBMF8897) to the Wellcome Sanger Institute to support the Aquatic Symbiosis Genomics Project, and by Wellcome through core funding to the Wellcome Sanger Institute (220540). Collection and preservation were funded by a grant of the Spanish Government (PID2019-108627RB-I00) to MM.

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

[version 1; peer review: 2 approved, 1 approved with reservations]

Data availability

European Nucleotide Archive: Crambe crambe. Accession number PRJEB65618; https://identifiers.org/ena.embl/PRJEB65618. The genome sequence is released openly for reuse. The Crambe crambe genome sequencing initiative is part of the Aquatic Symbiosis Genomics (ASG) project ( https://www.ebi.ac.uk/ena/browser/view/PRJEB43743). All raw sequence data and the assembly have been deposited in INSDC databases. The genome will be annotated using available RNA-Seq data and presented through the Ensembl pipeline at the European Bioinformatics Institute. Raw data and assembly accession identifiers are reported in Table 1 and Table 2.

Author information

Members of the Wellcome Sanger Institute Tree of Life Management, Samples and Laboratory Team are listed here: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10066175.

Members of the Wellcome Sanger Institute Scientific Operations: Sequencing Operations are listed here: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10043364.

Members of the Wellcome Sanger Institute Tree of Life Core Informatics team are listed here: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10066637.

Members of the European Bioinformatics Institute ASG Data Portal team are listed here: https://doi.org//10.5281/zenodo.10076466.

Members of the Wellcome Sanger Institute/Aquatic Symbiosis Genomics Project Leadership are listed here: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10184833.

References

- Abdennur N, Mirny LA: Cooler: scalable storage for Hi-C data and other genomically labeled arrays. Bioinformatics. 2020;36(1):311–316. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btz540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allio R, Schomaker-Bastos A, Romiguier J, et al. : MitoFinder: efficient automated large-scale extraction of mitogenomic data in target enrichment phylogenomics. Mol Ecol Resour. 2020;20(4):892–905. 10.1111/1755-0998.13160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, et al. : Basic Local Alignment Search Tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215(3):403–410. 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bateman A, Martin MJ, Orchard S, et al. : UniProt: the universal protein knowledgebase in 2023. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023;51(D1):D523–D531. 10.1093/nar/gkac1052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becerro MA, Uriz MJ, Turón X: Trends in space occupation by the encrusting sponge Crambe crambe: variation in shape as a function of size and environment. Mar Biol. 1994;121:301–307. 10.1007/BF00346738 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Becerro MA, Uriz MJ, Turon X: Chemically-mediated interactions in benthic organisms: the chemical ecology of Crambe crambe (Porifera, Poecilosclerida). Hydrobiologia. 1997;355(1–3):77–89. 10.1023/A:1003019221354 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Benoit G, Raguideau S, James R, et al. : High-quality metagenome assembly from long accurate reads with metaMDBG. Nat Biotechnol. 2024;42(9):1378–1383. 10.1038/s41587-023-01983-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchfink B, Reuter K, Drost HG: Sensitive protein alignments at Tree-of-Life scale using DIAMOND. Nat Methods. 2021;18(4):366–368. 10.1038/s41592-021-01101-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrier TJ, Maldonado M, Schmittmann L, et al. : Symbiont transmission in marine sponges: reproduction, development, and metamorphosis. BMC Biol. 2022;20(1): 100. 10.1186/s12915-022-01291-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Challis R, Kumar S, Sotero-Caio C, et al. : Genomes on a Tree (GoaT): a versatile, scalable search engine for genomic and sequencing project metadata across the eukaryotic Tree of Life [version 1; peer review: 2 approved]. Wellcome Open Res. 2023;8:24. 10.12688/wellcomeopenres.18658.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Challis R, Richards E, Rajan J, et al. : BlobToolKit – interactive quality assessment of genome assemblies. G3 (Bethesda). 2020;10(4):1361–1374. 10.1534/g3.119.400908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaumeil PA, Mussig AJ, Hugenholtz P, et al. : GTDB-Tk v2: memory friendly classification with the genome taxonomy database. Bioinformatics. 2022;38(23):5315–5316. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btac672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng H, Concepcion GT, Feng X, et al. : Haplotype-resolved de novo assembly using phased assembly graphs with hifiasm. Nat Methods. 2021;18(2):170–175. 10.1038/s41592-020-01056-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croué J, West NJ, Escande ML, et al. : A single betaproteobacterium dominates the microbial community of the crambescidine-containing sponge Crambe crambe. Sci Rep. 2013;3: 2583. 10.1038/srep02583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Veiga Leprevost F, Grüning BA, Alves Aflitos S, et al. : BioContainers: an open-source and community-driven framework for software standardization. Bioinformatics. 2017;33(16):2580–2582. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btx192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danecek P, Bonfield JK, Liddle J, et al. : Twelve years of SAMtools and BCFtools. GigaScience. 2021;10(2): giab008. 10.1093/gigascience/giab008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeMaere MZ, Darling AE: bin3C: exploiting Hi-C sequencing data to accurately resolve metagenome-assembled genomes. Genome Biol. 2019;20(1): 46. 10.1186/s13059-019-1643-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denton A, Yatsenko H, Jay J, et al. : Sanger Tree of Life wet laboratory protocol collection V.1. protocols.io. 2023. 10.17504/protocols.io.8epv5xxy6g1b/v1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Diesh C, Stevens GJ, Xie P, et al. : JBrowse 2: a modular genome browser with views of synteny and structural variation. Genome Biol. 2023;24(1): 74. 10.1186/s13059-023-02914-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duran S, Pascual M, Turon X: Low levels of genetic variation in mtDNA sequences over the western Mediterranean and Atlantic range of the sponge Crambe crambe (Poecilosclerida). Mar Biol. 2004;144(1):31–35. 10.1007/s00227-003-1178-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- El-Demerdash A, Atanasov AG, Bishayee A, et al. : Batzella, Crambe and Monanchora: highly prolific marine sponge genera yielding compounds with potential applications for cancer and other therapeutic areas. Nutrients. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute,2018;10(1):33. 10.3390/nu10010033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewels P, Magnusson M, Lundin S, et al. : MultiQC: summarize analysis results for multiple tools and samples in a single report. Bioinformatics. 2016;32(19):3047–3048. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btw354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewels PA, Peltzer A, Fillinger S, et al. : The nf-core framework for community-curated bioinformatics pipelines. Nat Biotechnol. 2020;38(3):276–278. 10.1038/s41587-020-0439-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gauthier MEA, Watson JR, Degnan SM: Draft genomes shed light on the dual bacterial symbiosis that dominates the microbiome of the coral reef sponge Amphimedon queenslandica. Front Mar Sci. 2016;3: 196. 10.3389/fmars.2016.00196 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grüning B, Dale R, Sjödin A, et al. : Bioconda: sustainable and comprehensive software distribution for the life sciences. Nat Methods. 2018;15(7):475–476. 10.1038/s41592-018-0046-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan D, McCarthy SA, Wood J, et al. : Identifying and removing haplotypic duplication in primary genome assemblies. Bioinformatics. 2020;36(9):2896–2898. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btaa025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harry E: PretextView (Paired REad TEXTure Viewer): a desktop application for viewing pretext contact maps.2022. Reference Source

- Jay J, Yatsenko H, Narváez-Gómez JP, et al. : Sanger Tree of Life sample preparation: triage and dissection. protocols.io. 2023. 10.17504/protocols.io.x54v9prmqg3e/v1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kang DD, Li F, Kirton E, et al. : MetaBAT 2: an adaptive binning algorithm for robust and efficient genome reconstruction from metagenome assemblies. PeerJ. 2019;7: e7359. 10.7717/peerj.7359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katoh K, Standley DM: MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol Biol Evol. 2013;30(4):772–80. 10.1093/molbev/mst010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerpedjiev P, Abdennur N, Lekschas F, et al. : HiGlass: web-based visual exploration and analysis of genome interaction maps. Genome Biol. 2018;19(1): 125. 10.1186/s13059-018-1486-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurtzer GM, Sochat V, Bauer MW: Singularity: scientific containers for mobility of compute. PLoS One. 2017;12(5): e0177459. 10.1371/journal.pone.0177459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letunic I, Bork P: Interactive Tree of Life (iTOL) v6: recent updates to the phylogenetic tree display and annotation tool. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024;52(W1):W78–W82. 10.1093/nar/gkae268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H: Minimap2: pairwise alignment for nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics. 2018;34(18):3094–3100. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez J: Squeeze-enrichment of intact cells (eukaryotic and prokaryotic) from marine sponge tissues prior to routine DNA extraction. protocols.io. 2022. 10.17504/protocols.io.n92ldzj4ov5b/v1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maldonado M: Intergenerational transmission of symbiotic bacteria in oviparous and viviparous demosponges, with emphasis on intracytoplasmically-compartmented bacterial types. J Mar Biol Assoc UK. 2007;87(6):1701–1713. 10.1017/S0025315407058080 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maldonado M, Bergquist PR: Phylum porifera. In: Young, C. M., Sewell, M. A., and Rice, M. E. (eds.) Atlas of marine invertebrate larvae. San Diego: Academic Press,2002;21–50. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- Maldonado M, Carmona MC, Uriz MJ, et al. : Decline in Mesozoic reef-building sponges explained by silicon limitation. Nature. 1999;401(6755):785–788. 10.1038/44560 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maldonado M, Carmona MC, Van Soest RWM, et al. : First record of the sponge genera Crambe and Discorhabdella for the eastern Pacific, with description of three new species. J Nat Hist. 2001;35(9):1261–1276. 10.1080/002229301750384293 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maldonado M, Carmona MC, Velásquez Z, et al. : Siliceous sponges as a silicon sink: an overlooked aspect of benthopelagic coupling in the marine silicon cycle. Limnol Oceanogr. 2005;50(3):799–809. 10.4319/lo.2005.50.3.0799 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Manni M, Berkeley MR, Seppey M, et al. : BUSCO update: novel and streamlined workflows along with broader and deeper phylogenetic coverage for scoring of eukaryotic, prokaryotic, and viral genomes. Mol Biol Evol. 2021;38(10):4647–4654. 10.1093/molbev/msab199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merkel D: Docker: lightweight Linux containers for consistent development and deployment. Linux J. 2014;2014(239):2, [Accessed 2 April 2024]. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- Olm MR, Brown CT, Brooks B, et al. : dRep: a tool for fast and accurate genomic comparisons that enables improved genome recovery from metagenomes through de-replication. ISME J. 2017;11(12):2864–2868. 10.1038/ismej.2017.126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padiglia A, Ledda FD, Padedda BM, et al. : Long-term experimental in situ farming of Crambe crambe (Demospongiae: Poecilosclerida). PeerJ. 2018;6: e4964. 10.7717/peerj.4964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pansini M, Pronzato R: Observations on the dynamics of a Mediterranean sponge community.In: Rützler, K. (ed.) New perspectives in sponge biology. Washington, DC. London: Smithsonian Institution Press,1990;404–415. [Google Scholar]

- Parks DH, Imelfort M, Skennerton CT, et al. : CheckM: assessing the quality of microbial genomes recovered from isolates, single cells, and metagenomes. Genome Res. 2015;25(7):1043–55. 10.1101/gr.186072.114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pointon DL, Eagles W, Sims Y, et al. : sanger-tol/treeval v1.0.0 – Ancient Atlantis.2023. 10.5281/zenodo.10047654 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Quinlan AR, Hall IM: BEDTools: a flexible suite of utilities for comparing genomic features. Bioinformatics. 2010;26(6):841–842. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao SSP, Huntley MH, Durand NC, et al. : A 3D map of the human genome at kilobase resolution reveals principles of chromatin looping. Cell. 2014;159(7):1665–1680. 10.1016/j.cell.2014.11.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhie A, Walenz BP, Koren S, et al. : Merqury: reference-free quality, completeness, and phasing assessment for genome assemblies. Genome Biol. 2020;21(1): 245. 10.1186/s13059-020-02134-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riesgo A, Maldonado M: An unexpectedly sophisticated, V-shaped spermatozoon in Demospongiae (Porifera): reproductive and evolutionary implications. Biol J Linn Soc. 2009;97(2):413–426. 10.1111/j.1095-8312.2009.01214.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt O: Die Spongien des Adriatischen Meeres. Engelmann, W. (ed.) . Leipzig,1862. [Google Scholar]

- Seemann T: Prokka: rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics. 2014;30(14):2068–2069. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sieber CMK, Probst AJ, Sharrar A, et al. : Recovery of genomes from metagenomes via a dereplication, aggregation and scoring strategy. Nat Microbiol. 2018;3(7):836–843. 10.1038/s41564-018-0171-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strickland M, Cornwell C, Howard C: Sanger Tree of Life fragmented DNA clean up: manual SPRI. protocols.io. 2023a. 10.17504/protocols.io.kxygx3y1dg8j/v1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Strickland M, Moll R, Cornwell C, et al. : Sanger Tree of Life HMW DNA extraction: manual MagAttract. protocols.io. 2023b. 10.17504/protocols.io.6qpvr33novmk/v1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor JA, Palladino G, Wemheuer B, et al. : Phylogeny resolved, metabolism revealed: functional radiation within a widespread and divergent clade of sponge symbionts. ISME J. 2021;15(2):503–519. 10.1038/s41396-020-00791-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todorovic M, Sampaio F, Howard C: Sanger Tree of Life HMW DNA fragmentation: diagenode Megaruptor ®3 for PacBio HiFi. protocols.io. 2023. 10.17504/protocols.io.8epv5x2zjg1b/v1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tripepi S, Longo O, La Camera R: A new pattern of spermiogenesis in the sponge Crambe crambe: preliminary observations.In: Csanády, A., Röhlich, P., and Szabó, D. (eds.) Eighth European congress on electron microscopy. Budapest: Programme Committee,1984;2073–2074. [Google Scholar]

- Turon M, Ford M, Maldonado M, et al. : Microbiome changes through the ontogeny of the marine sponge Crambe crambe. Environ Microbiome. 2024;19(1): 15. 10.1186/s40793-024-00556-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turon X, Codina M, Tarjuelo I, et al. : Mass recruitment of Ophiothrix fragilis (Ophiuroidea) on sponges: settlement patterns and post-settlement dynamics. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 2000;200:201–212. 10.3354/meps200201 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Turon X, Tarjuelo I, Uriz MJ: Growth dynamics and mortality of the encrusting sponge Crambe crambe (Poecilosclerida) in contrasting habitats: correlation with population structure and investment in defence. Funct Ecol. 1998;12(4):631–639. 10.1046/j.1365-2435.1998.00225.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Uliano-Silva M, Ferreira JGRN, Krasheninnikova K, et al. : MitoHiFi: a python pipeline for mitochondrial genome assembly from PacBio high fidelity reads. BMC Bioinformatics. 2023;24(1): 288. 10.1186/s12859-023-05385-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uriz MJ, Maldonado M, Turon X, et al. : How do reproductive output, larval behaviour, and recruitment contribute to adult spatial patterns in Mediterranean encrusting sponges? Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 1998;167:137–148. 10.3354/meps167137 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Uriz MJ, Turon X, Becerro MA: Morphology and ultrastructure of the swimming larvae of Crambe crambe (Demospongiae, Poecilosclerida). Invertebr Biol. 2001;120(4):295–307. 10.1111/j.1744-7410.2001.tb00039.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vasimuddin M, Misra S, Li H, et al. : Efficient architecture-aware acceleration of BWA-MEM for multicore systems.In: 2019 IEEE International Parallel and Distributed Processing Symposium (IPDPS).IEEE,2019;314–324. 10.1109/IPDPS.2019.00041 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu YW, Tang YH, Tringe SG, et al. : MaxBin: an automated binning method to recover individual genomes from metagenomes using an expectation-maximization algorithm. Microbiome. 2014;2(1): 26. 10.1186/2049-2618-2-26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou C, McCarthy SA, Durbin R: YaHS: yet another Hi-C scaffolding tool. Bioinformatics. 2023;39(1): btac808. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btac808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]