ABSTRACT

The expansion of hematopoietic cell clones, carrying alterations in genes frequently mutated in hematologic malignancies, in the absence of altered hematopoietic cell counts or otherwise defined disease criteria, is termed clonal hematopoiesis (CH). CH is frequently detectable in aged individuals and associates with numerous detrimental health impacts. These impacts are highly dependent on the type of mutations and the cellular context in which they manifest. Mutations in the hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell (HSPC) compartment as well as in self‐renewing more mature cells associate with increased risks of malignant disease, while mutations penetrating via hematopoiesis in non‐self‐renewing, mature cells associate with altered immune functions and consequent systemic effects, which can initiate or aggravate multiple non‐malignant diseases. Here we review the definitions of CH, major genetic drivers and lineage penetrance, and we highlight how CH impacts on hematological and non‐hematological conditions.

Keywords: clonal hematopoiesis, health outcomes, leukemia

1. Introduction

The hematopoietic system is responsible for a constant supply of mature hemato‐immune cells that maintain essential organismal functions. To ensure the needed high cellular output, the hematopoietic system is hierarchically organized and sustained by rare hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), which differentiate in highly proliferative hematopoietic progenitor cells (HPCs), which subsequently give rise to mature hemato‐lymphoid cells. HSCs are localized is specialized bone marrow niches and can maintain their cellular pool size via self‐renewing divisions, while they also give rise to HPCs, which progressively differentiate into mature effector cells. The HSC pool directly contributing to unperturbed hematopoiesis is considered highly polyclonal, with recent estimates of 20,000–200,000 HSCs participating about evenly in leukocyte production in humans below 65 years of age. In contrast, in individuals aged over 75 years, clonal diversity of the hematopoietic system is substantially decreased, with 30%–60% of hematopoiesis accounted for by 12–18 independent HSC clones [1, 2]. This is attributed to both, a loss and suppression of blood production from HSCs due to age‐associated dysfunctions [3] and to the continuous selection and expansion of HSC clones carrying driver‐mutations, rendering them fitter relatively to their non‐mutant counterparts [4]. The result of this life‐long ongoing clonal dynamics is the frequent onset of clonal hematopoiesis (CH, also termed age‐associated clonal hematopoiesis—ARCH), particularly in the aging population. CH associates with increased health risks, predominantly progression into hematological neoplasia (myeloid and lymphoid) but also non‐hematopoietic dysfunctions (cardiovascular, lung, renal, liver, rheumatological diseases), suggesting not only a pre‐leukemic role for CH but also a broader impact in the normal function of the hemato‐immune system [5]. Here we review the fundamental aspects of CH, highlighting its contribution to hematological and non‐hematological neoplasm development, its impact on non‐malignant diseases and implications in current immune‐therapeutic approaches.

2. Clonal Hematopoiesis (CH): Definition, Incidence and Drivers

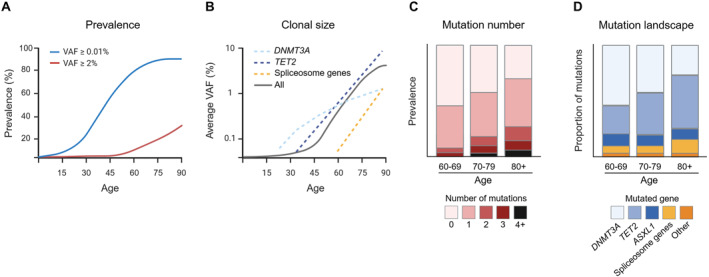

According to the World Health Organization (WHO) classification, clonal hematopoiesis (CH) refers to the presence of a population of cells derived from a mutated hematopoietic multipotent stem/progenitor cell harboring a selective growth advantage in the absence of unexplained cytopenias, hematological cancers, or other clonal disorders [6]. CH encompasses a complex group of entities that are defined based on the knowledge of the identity of the driver gene, the variant allele fraction (VAF) of the driver gene, the type of gene mutated and the presence or not of mosaic chromosomal alterations (mCAs) [5]. We here focus on the most frequent form of CH: clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential (CHIP), defined by the presence of one or more somatic mutations in known myeloid leukemia driver genes, detected in the blood or bone marrow cells at a VAF equal or > 2% (or over 4% for X‐linked gene mutation in males) in individuals lacking diagnostic criteria for defined hematological disorder or unexplained cytopenia [6]. Recent estimates suggest that incidence of CHIP in the general adult population (40–70‐year‐old) is around 5% and increases to 10%–20% in individuals over 70 years (Figure 1A). The majority (∼90%) of CHIP carriers have a single mutation, with mutations in one of three genes involved in epigenetic regulation: DNMT3A, TET2, and ASXL1 (DTA), accounting for two‐thirds of recurrent mutations, with the remaining one third including mutations in additional known myeloid neoplasia driver genes such as JAK2, TP53, GNAS, PPM1D, BCORL1, and SF3B1 [9, 10, 11]. Importantly, not only incidence increases with age, but also mutant clonal size and complexity (defined by the presence of more than one mutation) (Figure 1B,C). Interestingly, and contrasting with the definition of CH, CHIP cases that display one or more persistent unexplained cytopenias (and therefore a non‐normal health state) are classified by the WHO as clonal cytopenia of undetermined significance (CCUS) [6]. Compared with CHIP, CCUS has an overlapping mutational landscape, an approximate 10‐fold lower incidence, higher clonal size and clonal complexity and an increased risk of progression to myeloid neoplasia (MN—encompassing acute myeloid leukemia, myelodysplastic syndromes and myeloproliferative neoplasms) compared to CHIP [12, 13, 14], suggesting that CCUS likely represents a developmental intermediate state between CHIP and MN. We here use CH as an umbrella term for both CHIP and CCUS, as those two states are not always clearly separated in prior studies we relate to in this review.

FIGURE 1.

Age associates with key properties of clonal hematopoiesis (CH). (A) The estimated prevalence of CH as a function of age varies according to the variant allele frequency (VAF) used as a threshold for CH definition, which in turn depends on the sequencing method used. (B) Representative depiction of the average clonal size as a function of age (solid gray line), indicating increased clonal sizes in advanced ages. Mutation‐specific clonal expansions are indicated (dashed lines), with DNMT3A‐mutant clones showing higher expansion rates in earlier stages, TET2‐mutant clones showing a later onset and then a constant life‐long expansion rate, and spliceosome gene‐mutated clones showing a late onset and the highest expansion rates [7]. The category of spliceosome mutations includes SF3B1, SRSF2 and U2AF1. (C) Representative depiction of the prevalence of mutational number per individual according to age category, indicating increased mutational number in advanced ages (graph adapted from published data [8]). (D) Representative depiction of the proportion of mutations in different driver genes among all mutations detected per age category, indicating reduced relative frequency of DNMT3A mutations and increases in TET2 and ASLX1 mutations in advanced age. The category of spliceosome mutations includes SF3B1, SRSF2 and U2AF1 (graph adapted from published data [8]).

3. Lineage‐Specific Mutational Landscape of CHIP

CHIP was initially predominantly perceived as a myeloid form of clonal hematopoiesis. This is attributed to the fact that per definition the mutations first looked for and identified in CHIP carriers are frequently found in myeloid malignancies, and to the subsequent confirming observation that most CHIP carriers have an increased risk of developing myeloid but not lymphoid neoplasms [15]. In agreement, when looking for the penetrance of mutations in mature hematopoietic populations in CHIP carriers, it has been shown that mutant VAFs are higher in monocytes, granulocytes, and NK‐cells compared to B‐ or T‐cells. Moreover, when looking into bone marrow samples, CHIP mutations can be found in Lin−CD34+CD38− HSPCs with subsequent expansion to myeloid primed progenitors, strongly suggesting that CHIP derives from mutated HSPCs and then propagates preferentially into the myeloid branch, with lower penetration into and/or expansion within the lymphoid compartment. This might be due to a reduced permissiveness of some CHIP mutations for the complex process of B‐ and T‐cell development, as well as the overall reduced B‐ and T‐cell development in adult life, where some of the respective homeostasis is driven by mature B‐ and T‐cells [16, 17]. Interestingly, CH has also been recently proposed to precede the onset of lymphoid malignancies [15]. This entity is substantially less frequent than myeloid CHIP and will be discussed briefly at the end of this review.

4. CH and Progression to Hematological Neoplasm

CH is perceived as a pre‐malignant state of the hematopoietic system, as the somatic mutations detected in CH are frequently the founding mutations in hematologic malignancies. Indeed, CHIP and CCUS are both associated with an approximate 10–12 fold increased risk of MN development (the risk is slightly higher for CCUS) [18], with an overall rate of transformation of 0.5%–1% per year. However, this risk is highly dependent on specific characteristics. These include: (1) mutated gene—single mutation in DNMT3A has the lowest risk, while mutations in splicing factor genes (SF3B1, SRSF2), TP53, IDH1, IDH2, and RUNX1 have the highest risk; (2) number of mutations within a clone—higher mutational number (> 2 mutations) poses a higher risk; (3) mutant clone size—higher clonal sizes (VAFs ≥ 20%) pose a higher risk; (4) red cell characteristic—red cell distribution width (RDW) of 15% or more and mean corpuscular volume (MCV) of 100 fL or more associate with increased risk; (5) The onset of one or more persistent cytopenias—individuals with CCUS have higher risk than individuals with CHIP; and (6) age—individuals over 65 have increased risk [15]. Interestingly a recent study further highlights that mutational landscapes in CHIP carriers associate with increased propensity to develop specific myeloid malignancies, in detail, SF3B1 and SRSF2/TET2 co‐mutated cases associate with higher risk of MDS, and SRSF2/IDH2 co‐mutated cases are more likely to develop AML. Also, DNMT3A‐R882 mutations are specifically associated with AML [19]. Overall, ongoing efforts combining different CH parameters to establish myeloid neoplasia transformation risk scores are essential to understand not only the biology of the transition between pre‐ and full‐blown malignancy, but also hold the potential for a more precise staging and clinical management of CH carriers.

5. CHIP and Non‐Malignant Disease

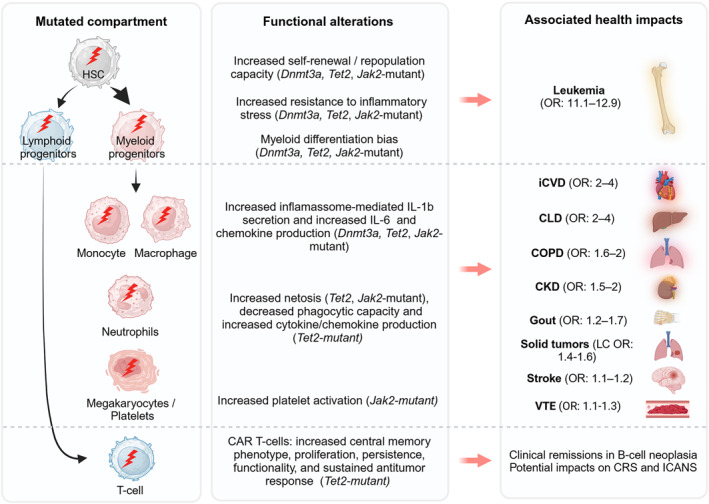

A growing body of evidence indicates that CHIP mutation‐specific effects in the mature hematopoietic compartment can lead to immune cell dysfunction and associated increased risk of nonmalignant disorders and overall mortality [20]. Indeed, multiple age‐related inflammatory pathologies have been positively associated with CHIP and likely act as a disease‐modifying factor. These include cardiovascular disease [21], chronic liver disease [22], chronic kidney disease (CKD) [23], chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) [24], gout [25], osteoporosis [26], stroke [27], and venous thromboembolism (VTE) [28] (Figure 2). Interestingly, CHIP has only been shown to be protective of one disease, Alzheimer's dementia, however the underlying mechanism thus far remains elusive [29].

FIGURE 2.

Health impacts of CHIP. Schematic depiction of the cellular compartment affected by CHIP‐associated mutations (left), the reported functional cellular alterations that associate with cell‐type specific CHIP mutations (middle) and the reported health impacts associated with CHIP (right). Red arrows between middle and right box indicate association but not causality. CAR, chimeric antigen receptor; CKD, chronic kidney disease; CLD, chronic liver disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CRS, cytokine release syndrome; HSC, hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell; ICANS, immune effector cell‐associated neurotoxicity syndrome; iCDV, ischemic cardiovascular disease; LC, lung cancer; OR, odds ratio; VTE, venous thromboembolism.

After leukemic transformation, ischemic cardiovascular disease (iCVD) is the pathology with higher risk in CHIP carriers, with an estimated 2‐fold increased risk of coronary heart disease and a 4‐fold increased risk of myocardial infarction in CHIP carriers compared to non‐carriers, with the strongest associations observed for TET2‐ and JAK2‐mutant cases. Importantly, and as observed for the risk of myeloid malignancy progression, clone size is also prognostic of iCVD outcomes in CHIP, with individuals with a VAF ≥ 10% showing higher iCVD risk than those with smaller clones [21]. Mechanistically, studies in mouse models attribute this effect to increased pro‐inflammatory cytokine production (IL‐1β, IL‐6, and chemokines) by Dnmt3a/Tet2‐mutant myeloid cells, particularly in the context of atherosclerotic plaque formation [30, 31]. Consistent with this finding, exploratory analysis of the IL‐1β inhibitor “canankinumab anti‐inflammatory thrombosis outcomes study” (CANTOS) showed reduced cardiovascular events, particularly among individuals with TET2‐mutant CHIP [32]. Liver disease is also highly impacted by CHIP, with VAF ≥ 10% doubling the risk of chronic liver disease (CLD), nonalcoholic hepatic steatosis, and cirrhosis in CHIP carriers. Also, this association is highly dependent on the type of CHIP mutations, with increased risk for CLD of 17.6‐fold for JAK2‐mutant CHIP, 5.4‐fold increase for TET2‐mutant CH, and a low risk for DNMT3A mutations. Mouse models of Tet2‐mutant CHIP studies further implicate liver resident macrophage‐derived inflammasome‐dependent inflammation (IL‐6, CXCL1, CCL22, and CCL17) in this outcome [22]. The impact of CHIP on the incidence of (chronic kidney disease (CKD), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), gout, osteoporosis, stroke and venous thromboembolism (VTE) are more moderate. For CKD, CHIP leads to 2.2‐fold risk of kidney failure over 5 years of follow‐up and increased risk of complications related to CKD, including kidney disease in context of anemia [33]. For COPD, individuals with CHIP show risks of moderate‐to‐severe, severe, or very severe COPD that were 1.6 and 2.2 times greater than those of noncarriers. Mouse Tet2‐mutant CHIP models with COPD further show that Tet2 loss in hematopoietic cells enhances pulmonary inflammation, increases IFN signaling, decreases TGF‐β signaling, and accelerates the development of emphysema [24]. In the case of gout, CHIP with a VAF ≥ 10% was associated with 1.3 times the risk of incident compared with no CHIP after adjusting for common gout risk factors. This risk was particularly higher in TET2‐mutant CHIP. In vivo mechanistic studies further revealed that Tet2‐knockout mice have increased monosodium urate‐induced inflammation in an NLRP inflammasome–dependent manner due to the greater production of IL1β by macrophages. As for osteoporosis, the risk of incident in individuals with CHIP is 1.4 times that of non‐CHIP. Moreover, larger CHIP clones, especially in DNMT3A, with VAF ≥ 10% were significantly correlated with lower estimated bone mineral density, consistent with accelerated bone loss. Mechanistically, this was associated with proinflammatory cytokines, including Irf3‐NF‐κB–mediated IL‐20 expression from Dnmt3a‐mutant macrophages [26]. Overall, the CHIP‐associated and age‐associated inflammatory diseases align with findings in mice, in which particularly Tet2‐ and Dnmt3a‐mutated compartments contribute to enhanced inflammatory settings [34, 35, 36, 37, 38].

6. CHIP and Solid Tumors

The associations between CHIP and solid tumors were initially revealed in cohorts of patients under treatment for solid malignancies. Accordingly, an initial study in a cohort of 8810 patients treated at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, identified CHIP in 25% of analyzed patients. Moreover, CHIP carriers with higher clonal sizes (VAF > 10%) had a reduced overall survival with the most common cause of death being progression of the primary tumor [39]. These associations have been generally confirmed in subsequent studies [40]. However, such analysis on patients undergoing therapy poses a high confounding risk, as (chemo)therapies can be direct drivers of CHIP (particularly in mutations in DNA damage response pathway genes [41]) or give further advantage to the mutated clones, and due to the existence of shared CHIP and cancer risk factors (e.g., age, smoking), which limit the ability of these studies to make casual conclusions about the risk associations between CHIP and cancer. These limitations have been reduced in larger, non‐cancer specific longitudinal studies. An analysis of 200,453 individuals from the UK Biobank found that CHIP, especially with mutation VAF > 10%, associates with lung cancer, kidney cancer, lymphoma, and sarcoma incidence. Interestingly, DNMT3A‐mutant CHIP also associated with incidence of stomach and bladder cancer, while mutations in splicing factors SF3B1 and SRSF2 were additionally associated with higher rates of colorectal and head/neck cancers [42]. A similar analysis using 628,388 individuals found relationships between CHIP and incident risk of lung, skin, prostate and breast cancer [43]. Indeed, lung cancer seems to be the solid tumor type mostly influenced by the presence of CHIP. CHIP (particularly in DNMT3A, TET2, and ASXL1 genes, with VAFs > 10%) associates with a 36% risk increase for lung cancer across several cohorts, even when controlling for other confounders [44]. Mechanistically, it is likely that mutant cells contribute directly to a dysfunctional tumor microenvironment (TME), as different studies have identified mutant immune cells in the TME in human solid tumor samples [45, 46]. Concerning the effects of hematopoietic Tet2 loss of function in tumor progression the reports are mixed. One such study, using a full Tet2 KO mouse model, suggests a pro‐tumorigenic effect of Tet2 deletion via an IL‐6‐mediated immunosuppressive effect, which promotes tumor growth in models of hepatocellular carcinoma and breast cancer [47]. Also, models of hematopoietic Tet2 deletion suggests that Tet2‐mutant myeloid cells produce higher levels of S100a8/S100a9, which enhance vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGF‐A) production by cancer cells, leading to increased tumor vasculature and growth in subcutaneously transplanted lung cancer [48]. Interestingly, in melanoma Tet2‐mutant CHIP effects seem to act contrary, resulting in reduced tumor burden via a Tet2‐loss mediated onset of proinflammatory tumor‐associated macrophage phenotype that promotes T‐cell infiltration [49]. Clearly, the full scope of how different CHIP drivers impact on tumor biology in different contexts needs more granular resolution (Dnmt3a [50], Asxl1 [51], and p53 [52]).

7. CHIP and Immunotherapy/Blood Cancer Therapy

Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) is currently either applied in an autologous (autologous‐HSCT) or in an allogeneic setting from sufficiently HLA‐compatible donors (allo(geneic)‐HSCT). Autologous‐HSCT is generally used to bridge hematopoietic failure after cancer treatment with aggressive chemotherapy, while allo‐HSCT is used to treat congenital or acquired marrow failure, and, in most cases, to exploit the graft versus tumor effect of donor allogeneic cells against recipient hematologic malignancies. CHIP is frequently observed in patients undergoing HSCT (reviewed in [53]). CHIP incidence in autologous‐HSCT is reported in the range of 10%–30% post transplantation (with older patients carrying higher CHIP incidence) and associates with enrichment of mutations in DNA‐damage response genes (mostly in TP53 and PPM1D) [54, 55, 56, 57]. This is likely a consequence of autologous‐HSCT patients being exposed to chemotherapy previously to graft collection, which selects for pre‐existing mutations conferring DNA‐damage resistance, and a consequence of subsequent proliferative advantage in a reduced hematopoietic compartment. Notably, the presence of pretransplant CHIP in autologous‐HSCT patients associates with increased risk for development of so called “therapy‐related” myeloid neoplasms (t‐MNs) and inferior overall survival, driven by t‐MNs and by non‐relapse‐associated adverse events [58]. CHIP incidence in allo‐HSCT donors ranges from 16% to 24% and the mutational spectrum overlaps with CHIP in the general population. Donor CHIP mutations are frequently found in recipients, where they show consistent but modest expansions [59, 60, 61]. Indeed, two models of HCT‐specific selection have been proposed, with pruning selection referring to cases when cell divisions occur mostly in the donor pre‐transplantation and consequent clonal dominances are maintained in the recipient. While in growth selection, which is more frequent in clones with multiple driver mutations, cell divisions and consequent clonal dominances occur in the recipient after engraftment [62]. Importantly, while donor derived leukemia can occur at low rates, typically from donor CHIP with TP53 or splicing factor mutations or from donors carrying germline DDX41 mutations [61], donor‐engrafted CHIP after allo‐HSCT associates with decreased risk of disease relapse but does not affect overall survival, progression‐free survival or non‐relapse mortality [58]. Strikingly, specifically donor DNMT3A‐CHIP (at VAF > 1%) associates with improved recipient survival due to reduced relapse risk and concomitant increased risk for chronic graft‐vs‐host disease which associates with an increased inflammatory milieu (mostly IL‐12) in recipients [61]. A similar phenomenon is observed in the context of CAR T‐cell therapies, where the disruption of the CHIP‐associated genes TET2, DNMT3A, and CBL in CAR T‐cells have been associated with clinical remissions. In these cases, CAR T‐cells carrying these alterations showed higher central memory phenotype, resulting in higher T‐cell proliferation, long‐term persistence, increased functionality, and sustained antitumor response [63, 64, 65]. On the other hand, the impact of CAR T‐cell therapies on cancer patients that carry CHIP seems to be more heterogenous and probably disease dependent, with studies suggesting no impact [66], increased rates of complete response and cytokine release syndrome (CRS) severity in patients younger than age 60 years [67], or increased risk of immune effector cell‐associated neurotoxicity syndrome (ICANS), CRS severity, and higher cumulative incidence of therapy‐related myeloid neoplasms after CAR T‐cell therapy [68]. Overall, these studies indicate that further investigation into the mechanisms and interventions to guide CAR T‐cell therapy in the context of CH are warranted.

8. Lymphoid Clonal Hematopoiesis and Lymphoid Neoplasia

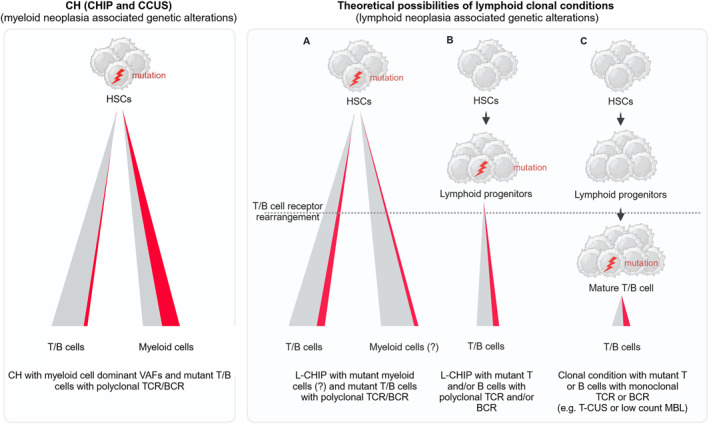

CH was originally defined by sensitive genetic testing for the presence of known myeloid neoplasia driver genes in hematopoietic healthy appearing populations [9, 10, 11]. Taking a similar approach, but focusing on sensitive testing for the presence of known recurrent lymphoid neoplasia driving genes as well as on mosaic chromosomal alterations (mCA), Niroula et al. recently subdivided CH in myeloid CHIP (M‐CHIP) and lymphoid CHIP (L‐CHIP), as well as myeloid mosaic chromosomal alterations (M‐mCAs) and lymphoid mosaic chromosomal alterations (L‐mCA) [15]. Both L‐CHIP and L‐mCA are defined by a 2% VAF in blood leukocytes without meeting diagnostic criteria of a lymphoid malignancy. Like CHIP and CCUS, the prevalence of L‐CHIP increases with age, but is less common than its myeloid counterpart with a predicted incidence of approximately 1% in the adult population (40–70 years old), that is in the elderly population about a log less prevalent than M‐CHIP. The mutational landscape of L‐CHIP includes genes most frequently implicated in lymphoid malignancy, and contrarily to M‐CHIP, there is an even distribution of genotypes without a clear set of dominant mutations. Interestingly, while L‐CHIP associates with increased incidence of lymphoid malignancy (mostly chronic lymphocytic leukemia and small lymphocytic lymphoma) there is no association with coronary artery disease or overall mortality, as observed for M‐CHIP [15]. Concerning the clonal population driving L‐CHIP, it is expected that the mutation occurs in HSCs and lymphoid progenitors, however formal proof of this is still lacking. Importantly L‐CHIP should be distinguished from other mature lymphoid cell clonal conditions. Indeed, the long‐term persistence of mature T‐ and B‐cells (with uniquely rearranged T‐ or B‐cell receptors), coupled with their proliferative capacity and programmed mutagenesis upon antigen recognition (in B‐cells) creates additional opportunities for these populations to acquire L‐CHIP mutations. Thus, caution in classification of these cases as L‐CHIP is recommended, as they might represent conditions such as (very) low count monoclonal B lymphocytosis (MBL) or T‐cell clones of uncertain significance (T‐CUS) [69] (Figure 3). Moreover, mutations occurring at the stem and progenitor level and their fixation in the lymphoid system might depend on the fitness gains they provide to specific cellular states along the hematopoietic tree, and possibly secondary mutations occurring at more mature, self‐renewing cell states. Concerning L‐CHIP, the full scope of clonal metrics predisposing for transformation are still undetermined. However clonal size and higher mutational numbers associate with increased risk of malignancy, particularly in individuals with elevated lymphocyte counts [15]. L‐CHIP connects to subsequent educational presentations on clonal T‐cell, B‐cell and plasma cell precursor states.

FIGURE 3.

Cell of origin in clonal conditions of the hematopoietic system. Schematic depiction of the implications of the cell of origin in hematopoietic clonal conditions. In CH (CHIP and CCUS) (left panel), the mutations are thought to occur at the HSC level leading to higher variant allele frequency detection in the mature myeloid compartment, with minor presence of the mutation in the lymphoid compartment. In lymphoid clonal conditions (right panel), the mutations can occur in one of three scenarios: (A) Mutation occurrence in the HSC compartment with transmission to lymphoid (and presumably to myeloid) progeny, which will then undergo receptor rearrangement to form a T/B cell receptor‐diverse mutant clone. How L‐CHIP mutations propagate in the myeloid lineage is currently largely unknown (depicted with question mark). (B) Mutation occurrence in the lymphoid progenitor compartment before receptor rearrangement, leading to a T/B cell receptor‐diverse mutant clone. (C) Mutation occurrence at lymphocyte developmental stages, which have already undergone T‐ or B‐cell receptor rearrangement, which upon expansion form a monoclonal T‐ or B‐cell receptor mutant clone. The distribution of mutations in other lineages (e.g., natural killer cells) has been omitted for simplicity. MBL, monoclonal B lymphocytosis; T‐CUS, T‐cell clones of uncertain significance; VAF, variant allele frequency.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Peer Review

The peer review history for this article is available at https://www.webofscience.com/api/gateway/wos/peer-review/10.1002/hon.70075.

Acknowledgments

We thank Steffen Böttcher for critical input on the manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by Swiss National Science Foundation 320030_219676/1 to M.G.M.

Data Availability Statement

The authors have nothing to report.

References

- 1. Lee‐Six H., Øbro N. F., Shepherd M. S., et al., “Population Dynamics of Normal Human Blood Inferred From Somatic Mutations,” Nature 561, no. 7724 (2018): 473–478, 10.1038/s41586-018-0497-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mitchell E., Spencer Chapman M., Williams N., et al., “Clonal Dynamics of Haematopoiesis Across the Human Lifespan,” Nature 606, no. 7913 (2022): 343–350, 10.1038/s41586-022-04786-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kovtonyuk L. V., Fritsch K., Feng X., Manz M. G., and Takizawa H., “Inflamm‐Aging of Hematopoiesis, Hematopoietic Stem Cells, and the Bone Marrow Microenvironment,” Frontiers in Immunology 7 (2016): 502, 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Jaiswal S. and Ebert B. L., “Clonal Hematopoiesis in Human Aging and Disease,” Science 366, no. 6465 (2019): eaan4673, 10.1126/science.aan4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Weeks L. D. and Ebert B. L., “Causes and Consequences of Clonal Hematopoiesis,” Blood 142, no. 26 (2023): 2235–2246, 10.1182/blood.2023022222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Khoury J. D., Solary E., Abla O., et al., “The 5th Edition of the World Health Organization Classification of Haematolymphoid Tumours: Myeloid and Histiocytic/Dendritic Neoplasms,” Leukemia 36, no. 7 (2022): 1703–1719, 10.1038/s41375-022-01613-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fabre M. A., de Almeida J. G., Fiorillo E., et al., “The Longitudinal Dynamics and Natural History of Clonal Haematopoiesis,” Nature 606, no. 7913 (2022): 335–342, 10.1038/s41586-022-04785-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. van Zeventer I. A., de Graaf A. O., Salzbrunn J. B., et al., “Evolutionary Landscape of Clonal Hematopoiesis in 3,359 Individuals From the General Population,” Cancer Cell 41, no. 6 (2023): 1017–1031.e4, 10.1016/j.ccell.2023.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Genovese G., Kähler A. K., Handsaker R. E., et al., “Clonal Hematopoiesis and Blood‐Cancer Risk Inferred From Blood DNA Sequence,” New England Journal of Medicine 371, no. 26 (2014): 2477–2487, 10.1056/nejmoa1409405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jaiswal S., Fontanillas P., Flannick J., et al., “Age‐Related Clonal Hematopoiesis Associated With Adverse Outcomes,” New England Journal of Medicine 371, no. 26 (2014): 2488–2498, 10.1056/nejmoa1408617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Xie M., Lu C., Wang J., et al., “Age‐Related Mutations Associated With Clonal Hematopoietic Expansion and Malignancies,” Nature Medicine 20, no. 12 (2014): 1472–1478, 10.1038/nm.3733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Weeks L. D., Niroula A., Neuberg D., et al., “Prediction of Risk for Myeloid Malignancy in Clonal Hematopoiesis,” NEJM Evidence 2, no. 5 (2023): EVIDoa2200310, 10.1056/evidoa2200310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cargo C., Bernard E., Beinortas T., et al., “Predicting Cytopenias, Progression, and Survival in Patients With Clonal Cytopenia of Undetermined Significance: A Prospective Cohort Study,” Lancet Haematology 11, no. 1 (2024): e51–e61, 10.1016/s2352-3026(23)00340-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gallì A., Todisco G., Catamo E., et al., “Relationship Between Clone Metrics and Clinical Outcome in Clonal Cytopenia,” Blood 138, no. 11 (2021): 965–976, 10.1182/blood.2021011323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Niroula A., Sekar A., Murakami M. A., et al., “Distinction of Lymphoid and Myeloid Clonal Hematopoiesis,” Nature Medicine 27, no. 11 (2021): 1921–1927, 10.1038/s41591-021-01521-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Arends C. M., Galan‐Sousa J., Hoyer K., et al., “Hematopoietic Lineage Distribution and Evolutionary Dynamics of Clonal Hematopoiesis,” Leukemia 32, no. 9 (2018): 1908–1919, 10.1038/s41375-018-0047-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Young A. L., Challen G. A., Birmann B. M., and Druley T. E., “Clonal Haematopoiesis Harbouring AML‐Associated Mutations Is Ubiquitous in Healthy Adults,” Nature Communications 7, no. 1 (2016): 12484, 10.1038/ncomms12484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chien K. S., Ong F., Kim K., et al., “Cancer Patients With Clonal Hematopoiesis Die From Primary Malignancy or Comorbidities Despite Higher Rates of Transformation to Myeloid Neoplasms,” Cancer Medicine 13, no. 5 (2024): e7093, 10.1002/cam4.7093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gu M., Kovilakam S. C., Dunn W. G., et al., “Multiparameter Prediction of Myeloid Neoplasia Risk,” Nature Genetics 55, no. 9 (2023): 1523–1530, 10.1038/s41588-023-01472-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Belizaire R., Wong W. J., Robinette M. L., and Ebert B. L., “Clonal Haematopoiesis and Dysregulation of the Immune System,” Nature Reviews Immunology 23, no. 9 (2023): 595–610, 10.1038/s41577-023-00843-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jaiswal S., Natarajan P., Silver A. J., et al., “Clonal Hematopoiesis and Risk of Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease,” New England Journal of Medicine 377, no. 2 (2017): 111–121, 10.1056/nejmoa1701719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wong W. J., Emdin C., Bick A. G., et al., “Clonal Haematopoiesis and Risk of Chronic Liver Disease,” Nature 616, no. 7958 (2023): 747–754, 10.1038/s41586-023-05857-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Dawoud A. A. Z., Gilbert R. D., Tapper W. J., and Cross N. C. P., “Clonal Myelopoiesis Promotes Adverse Outcomes in Chronic Kidney Disease,” Leukemia 36, no. 2 (2022): 507–515, 10.1038/s41375-021-01382-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Miller P. G., Qiao D., Rojas‐Quintero J., et al., “Association of Clonal Hematopoiesis With Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease,” Blood 139, no. 3 (2022): 357–368, 10.1182/blood.2021013531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Agrawal M., Niroula A., Cunin P., et al., “TET2‐Mutant Clonal Hematopoiesis and Risk of Gout,” Blood 140, no. 10 (2022): 1094–1103, 10.1182/blood.2022015384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kim P. G., Niroula A., Shkolnik V., et al., “Dnmt3a‐Mutated Clonal Hematopoiesis Promotes Osteoporosis,” Journal of Experimental Medicine 218, no. 12 (2021): e20211872, 10.1084/jem.20211872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bhattacharya R., Zekavat S. M., Haessler J., et al., “Clonal Hematopoiesis Is Associated With Higher Risk of Stroke,” Stroke 53, no. 3 (2022): 788–797, 10.1161/strokeaha.121.037388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zon R. L., Sekar A., Clapham K., et al., “JAK2‐Mutant Clonal Hematopoiesis Is Associated With Venous Thromboembolism,” Blood 144, no. 20 (2024): 2149–2154, 10.1182/blood.2024024187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bouzid H., Belk J. A., Jan M., et al., “Clonal Hematopoiesis Is Associated With Protection From Alzheimer's Disease,” Nature Medicine 29, no. 7 (2023): 1662–1670, 10.1038/s41591-023-02397-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Fuster J. J., MacLauchlan S., Zuriaga M. A., et al., “Clonal Hematopoiesis Associated With TET2 Deficiency Accelerates Atherosclerosis Development in Mice,” Science 355, no. 6327 (2017): 842–847, 10.1126/science.aag1381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rauch P. J., Gopakumar J., Silver A. J., et al., “Loss‐of‐Function Mutations in Dnmt3a and Tet2 Lead to Accelerated Atherosclerosis and Concordant Macrophage Phenotypes,” Nature Cardiovascular Research 2, no. 9 (2023): 805–818, 10.1038/s44161-023-00326-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Svensson E. C., Madar A., Campbell C. D., et al., “TET2‐Driven Clonal Hematopoiesis and Response to Canakinumab: An Exploratory Analysis of the CANTOS Randomized Clinical Trial,” JAMA Cardiology 7, no. 5 (2022): 521–528, 10.1001/jamacardio.2022.0386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Vlasschaert C., McNaughton A. J., Chong M., et al., “Association of Clonal Hematopoiesis of Indeterminate Potential With Worse Kidney Function and Anemia in Two Cohorts of Patients With Advanced Chronic Kidney Disease,” Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 33, no. 5 (2022): 985–995, 10.1681/asn.2021060774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Cai Z., Kotzin J. J., Ramdas B., et al., “Inhibition of Inflammatory Signaling in Tet2 Mutant Preleukemic Cells Mitigates Stress‐Induced Abnormalities and Clonal Hematopoiesis,” Cell Stem Cell 23, no. 6 (2018): 833–849.e5, 10.1016/j.stem.2018.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Caiado F., Kovtonyuk L. V., Gonullu N. G., Fullin J., Boettcher S., and Manz M. G., “Aging Drives Tet2+/‐ Clonal Hematopoiesis via IL‐1 Signaling,” Blood 141, no. 8 (2023): 886–903, 10.1182/blood.2022016835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Caiado F. and Manz M. G., “IL‐1 in Aging and Pathologies of Hematopoietic Stem Cells,” Blood 144, no. 4 (2024): 368–377, 10.1182/blood.2023023105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Cull A. H., Snetsinger B., Buckstein R., Wells R. A., and Rauh M. J., “Tet2 Restrains Inflammatory Gene Expression in Macrophages,” Experimental Hematology 55 (2017): 56–70.e13, 10.1016/j.exphem.2017.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hormaechea‐Agulla D., Matatall K. A., Le D. T., et al., “Chronic Infection Drives Dnmt3a‐Loss‐of‐Function Clonal Hematopoiesis via IFNγ Signaling,” Cell Stem Cell 28, no. 8 (2021): 1428–1442.e6, 10.1016/j.stem.2021.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Coombs C. C., Zehir A., Devlin S. M., et al., “Therapy‐Related Clonal Hematopoiesis in Patients With Non‐Hematologic Cancers Is Common and Associated With Adverse Clinical Outcomes,” Cell Stem Cell 21, no. 3 (2017): 374–382.e4, 10.1016/j.stem.2017.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Pich O., Reyes‐Salazar I., Gonzalez‐Perez A., and Lopez‐Bigas N., “Discovering the Drivers of Clonal Hematopoiesis,” Nature Communications 13, no. 1 (2022): 4267, 10.1038/s41467-022-31878-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bolton K. L., Ptashkin R. N., Gao T., et al., “Cancer Therapy Shapes the Fitness Landscape of Clonal Hematopoiesis,” Nature Genetics 52, no. 11 (2020): 1219–1226, 10.1038/s41588-020-00710-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kar S. P., Quiros P. M., Gu M., et al., “Genome‐Wide Analyses of 200,453 Individuals Yield New Insights Into the Causes and Consequences of Clonal Hematopoiesis,” Nature Genetics 54, no. 8 (2022): 1155–1166, 10.1038/s41588-022-01121-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kessler M. D., Damask A., O’Keeffe S., et al., “Common and Rare Variant Associations With Clonal Haematopoiesis Phenotypes,” Nature 612, no. 7939 (2022): 301–309, 10.1038/s41586-022-05448-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Tian R., Wiley B., Liu J., et al., “Clonal Hematopoiesis and Risk of Incident Lung Cancer,” Journal of Clinical Oncology 41, no. 7 (2023): 1423–1433, 10.1200/jco.22.00857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kleppe M., Comen E., Wen H. Y., et al., “Somatic Mutations in Leukocytes Infiltrating Primary Breast Cancers,” NPJ Breast Cancer 1 (2015): 15005, 10.1038/npjbcancer.2015.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Severson E. A., Riedlinger G. M., Connelly C. F., et al., “Detection of Clonal Hematopoiesis of Indeterminate Potential in Clinical Sequencing of Solid Tumor Specimens,” Blood 131, no. 22 (2018): 2501–2505, 10.1182/blood-2018-03-840629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Li S., Feng J., Wu F., et al., “TET2 Promotes Anti‐Tumor Immunity by Governing G‐MDSCs and CD8(+) T‐Cell Numbers,” EMBO Reports 21, no. 10 (2020): e49425, 10.15252/embr.201949425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Nguyen Y. T. M., Fujisawa M., Nguyen T. B., et al., “Tet2 Deficiency in Immune Cells Exacerbates Tumor Progression by Increasing Angiogenesis in a Lung Cancer Model,” Cancer Science 112, no. 12 (2021): 4931–4943, 10.1111/cas.15165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Pan W., Zhu S., Qu K., et al., “The DNA Methylcytosine Dioxygenase Tet2 Sustains Immunosuppressive Function of Tumor‐Infiltrating Myeloid Cells to Promote Melanoma Progression,” Immunity 47, no. 2 (2017): 284–297.e5, 10.1016/j.immuni.2017.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Feng Y., Yuan Q., Newsome R. C., et al., “Hematopoietic‐Specific Heterozygous Loss of Dnmt3a Exacerbates Colitis‐Associated Colon Cancer,” Journal of Experimental Medicine 220, no. 11 (2023): e20230011, 10.1084/jem.20230011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Liu X., Sato N., Shimosato Y., et al., “CHIP‐Associated Mutant ASXL1 in Blood Cells Promotes Solid Tumor Progression,” Cancer Science 113, no. 4 (2022): 1182–1194, 10.1111/cas.15294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. He X. Y., Xiang C., Zhang C. X., et al., “p53 in the Myeloid Lineage Modulates an Inflammatory Microenvironment Limiting Initiation and Invasion of Intestinal Tumors,” Cell Reports 13, no. 5 (2015): 888–897, 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.09.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Wilk C. M., Manz M. G., and Boettcher S., “Clonal Hematopoiesis in Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation,” Current Opinion in Hematology 28, no. 2 (2021): 94–100, 10.1097/moh.0000000000000631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Gibson C. J., Lindsley R. C., Tchekmedyian V., et al., “Clonal Hematopoiesis Associated With Adverse Outcomes After Autologous Stem‐Cell Transplantation for Lymphoma,” Journal of Clinical Oncology 35, no. 14 (2017): 1598–1605, 10.1200/jco.2016.71.6712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Husby S., Favero F., Nielsen C., et al., “Clinical Impact of Clonal Hematopoiesis in Patients With Lymphoma Undergoing ASCT: A National Population‐Based Cohort Study,” Leukemia 34, no. 12 (2020): 3256–3268, 10.1038/s41375-020-0795-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Mouhieddine T. H., Sperling A. S., Redd R., et al., “Clonal Hematopoiesis Is Associated With Adverse Outcomes in Multiple Myeloma Patients Undergoing Transplant,” Nature Communications 11, no. 1 (2020): 2996, 10.1038/s41467-020-16805-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Ortmann C. A., Dorsheimer L., Abou‐El‐Ardat K., et al., “Functional Dominance of CHIP‐Mutated Hematopoietic Stem Cells in Patients Undergoing Autologous Transplantation,” Cell Reports 27, no. 7 (2019): 2022–2028.e3, 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.04.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Xie Y., Kazakova V., Weeks L. D., et al., “Effects of Donor‐Engrafted Clonal Hematopoiesis in Allogeneic and Autologous Stem Cell Transplantation: A Systematic Review and Meta‐Analysis,” Bone Marrow Transplantation 59, no. 11 (2024): 1585–1593, 10.1038/s41409-024-02403-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Boettcher S., Wilk C. M., Singer J., et al., “Clonal Hematopoiesis in Donors and Long‐Term Survivors of Related Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation,” Blood 135, no. 18 (2020): 1548–1559, 10.1182/blood.2019003079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Frick M., Chan W., Arends C. M., et al., “Role of Donor Clonal Hematopoiesis in Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem‐Cell Transplantation,” Journal of Clinical Oncology 37, no. 5 (2019): 375–385, 10.1200/jco.2018.79.2184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Gibson C. J., Kim H. T., Zhao L., et al., “Donor Clonal Hematopoiesis and Recipient Outcomes After Transplantation,” Journal of Clinical Oncology 40, no. 2 (2022): 189–201, 10.1200/jco.21.02286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Spencer Chapman M., Wilk C. M., Boettcher S., et al., “Clonal Dynamics After Allogeneic Haematopoietic Cell Transplantation,” Nature 635, no. 8040 (2024): 926–934, 10.1038/s41586-024-08128-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Fraietta J. A., Nobles C. L., Sammons M. A., et al., “Disruption of TET2 Promotes the Therapeutic Efficacy of CD19‐Targeted T Cells,” Nature 558, no. 7709 (2018): 307–312, 10.1038/s41586-018-0178-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Prinzing B., Zebley C. C., Petersen C. T., et al., “Deleting DNMT3A in CAR T Cells Prevents Exhaustion and Enhances Antitumor Activity,” Science Translational Medicine 13, no. 620 (2021): eabh0272, 10.1126/scitranslmed.abh0272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Shah N. N., Qin H., Yates B., et al., “Clonal Expansion of CAR T Cells Harboring Lentivector Integration in the CBL Gene Following Anti‐CD22 CAR T‐Cell Therapy,” Blood Advances 3, no. 15 (2019): 2317–2322, 10.1182/bloodadvances.2019000219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Panagiota V., Kerschbaum J. F., Penack O., et al., “Clinical Implications and Dynamics of Clonal Hematopoiesis in Anti‐CD19 CAR T‐Cell Treated Patients,” HemaSphere 7, no. 10 (2023): e957, 10.1097/hs9.0000000000000957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Miller P. G., Sperling A. S., Brea E. J., et al., “Clonal Hematopoiesis in Patients Receiving Chimeric Antigen Receptor T‐Cell Therapy,” Blood Advances 5, no. 15 (2021): 2982–2986, 10.1182/bloodadvances.2021004554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Saini N. Y., Swoboda D. M., Greenbaum U., et al., “Clonal Hematopoiesis Is Associated With Increased Risk of Severe Neurotoxicity in Axicabtagene Ciloleucel Therapy of Large B‐Cell Lymphoma,” Blood Cancer Discovery 3, no. 5 (2022): 385–393, 10.1158/2643-3230.bcd-21-0177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. von Beck K., von Beck T., Ferrell P. B. Jr, Bick A. G., and Kishtagari A., “Lymphoid Clonal Hematopoiesis: Implications for Malignancy, Immunity, and Treatment,” Blood Cancer Journal 13, no. 1 (2023): 5, 10.1038/s41408-022-00773-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The authors have nothing to report.