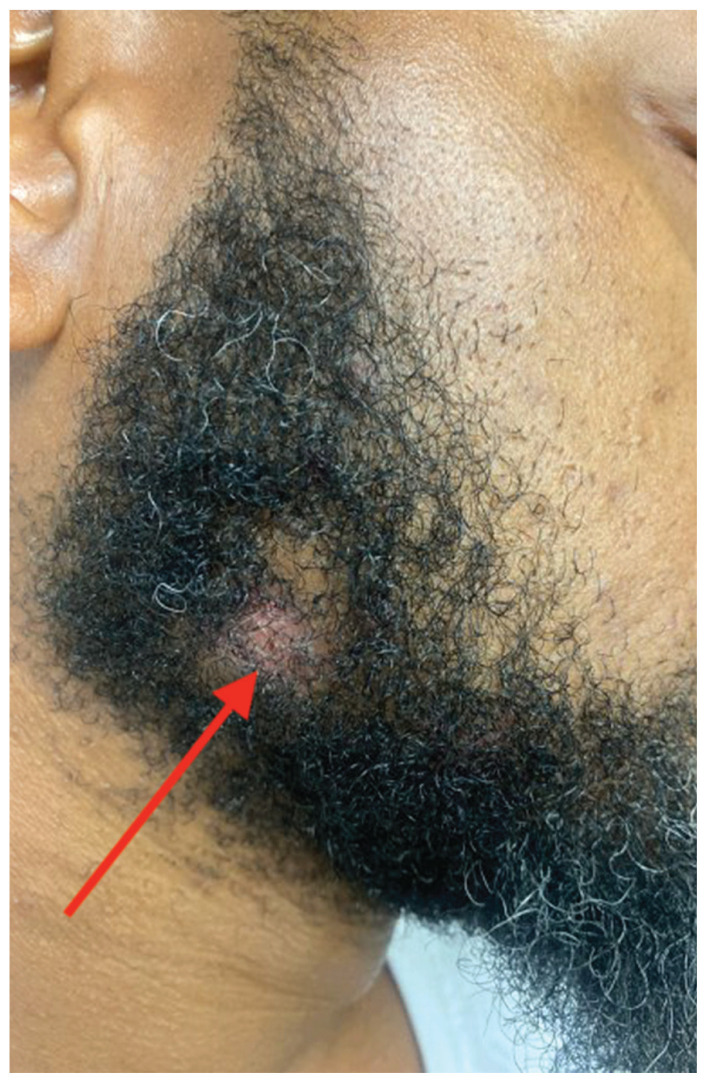

A 40-year-old man with no significant medical history or comorbidities presented with a violaceous papule involving his nasal tip and scaly, violaceous plaques with associated alopecia involving his beard (Figure). Skin biopsy confirmed granulomatous dermatitis. Additional workup was notable for hypercalcemia (10.5 mg/dL; reference range, 8.4–10.2 mg/dL), elevated chitotriosidase (317 nmol/h/mL; reference range, < 150 nmol/h/mL), and bibasilar opacities with left perihilar consolidation on chest X-ray. The patient had a prolonged PR interval (207 ms; reference range, 120–200 ms) on electrocardiogram. A cardiac positron emission tomography revealed low level fluorodeoxyglucose uptake in the left ventricle. No ocular involvement was noted on evaluation by ophthalmology. The patient’s pharmacotherapy included prednisone 10 mg daily, methotrexate 7.5 mg weekly, and hydroxychloroquine 200 mg daily.

What is your diagnosis?

Langerhans cell histiocytosis

Lupus pernio

Discoid lupus erythematosus

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis

Granuloma annulare

DISCUSSION

The patient’s violaceous papule on the nose with an apple jelly appearance is consistent with lupus pernio—a cutaneous form of sarcoidosis associated with respiratory involvement. Lupus pernio disproportionately affects African Americans, which further supports this diagnosis.1 Lupus pernio is characterized by violaceous, indurated plaques predominantly on the face. It has a strong association with systemic sarcoidosis and often involves the lungs and other organs, as seen in this case. The laboratory results support this diagnosis. Hypercalcemia is a common systemic manifestation of sarcoidosis due to increased production of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D by activated macrophages with granulomas.2 Elevated chitotriosidase, an enzyme produced by macrophages, is another biomarker of sarcoidosis reflecting granuloma burden.3

The differential diagnoses included Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH), discoid lupus erythematosus, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, and granuloma annulare. However, these diagnoses did not fully align with the entirety of the patient’s clinical presentation and laboratory findings. LCH is a rare neoplastic disorder characterized by the abnormal proliferation and accumulation of Langerhans cells, a type of dendritic cell involved in immune response, in various tissues such as the skin and bone. Dermatologic findings in LCH include brown/purple papules and an erythematous papular rash rather than the violaceous plaques/papules in lupus pernio. LCH can have lung involvement; it typically presents with nodular or cystic changes in the upper lobes as opposed to the bibasilar opacities seen in this case.

Discoid lupus erythematosus presents with characteristic round, erythematous, scaly plaques on the cheeks, scalp, and ears. This is different from the apple jelly appearance seen in this case and does not present with systemic granulomatous involvement.

Typical manifestations of granulomatosis with polyangiitis, formerly known as Wegener’s granulomatosis, include renal disease, upper and lower respiratory tract involvement, or necrotizing vasculitis. Cutaneous manifestions of granulomatosis with polyangiitis typically include purpura or ulcers rather than the violaceous plaques seen in lupus pernio. Patients with granulomatosis with polyangiitis would also present with nonspecific systemic symptoms such as fever, weight loss, and malaise, which are not depicted in this case.4

Granuloma annulare is a benign condition that often presents with annular plaques that are skin-colored rather than violaceous. These plaques are often found on the hands and feet rather than the face. This condition also lacks the systemic manifestations seen in this case.

In primary care, encountering violaceous papule and plaques on the face, especially on the nasal alae or ear, should be concerning for possible lupus pernio, particularly in high-risk populations such as young African Americans. These lesions generally have a more indurated “deep” and “doughy” appearance and can result in scarring, distinguishing them from other types of cutaneous sarcoidosis. An apple jelly appearance seen on diascopy with a glass slide can further support the diagnosis. While the lesions are typically asymptomatic, patients may be concerned about potential cosmetic disfigurement. Given the potential for scarring and the association with systemic sarcoidosis, a dermatology referral is recommended for further evaluation and management.

A detailed patient history, physical examination, and laboratory exams are essential to accurately diagnose lupus pernio. Biopsy of a skin lesion, serum markers, and imaging studies were utilized to help assess systemic involvement and further confirm diagnosis in this patient. Following the diagnosis, the patient was started on his current regimen of prednisone, methotrexate, and hydroxychloroquine, which are standard therapies for managing both cutaneous and systemic sarcoidosis.

This case shows the importance of recognizing lupus pernio, a distinct form of cutaneous sarcoidosis, in patients presenting with characteristic skin lesions and systemic involvement. It is essential to differentiate it from other granulomatous and inflammatory skin conditions to ensure appropriate management and prevent complications.

Federal Practitioner thanks the Association of Military Dermatologists (militaryderm.org) for their assistance in developing the Image Challenge. Submissions based on photographs, radiography, or any other visual medium are welcomed.

Footnotes

Author disclosures: The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the US Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review the complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administeringpharmacologic therapy to patients.

Ethics and consent: The patient provided informed consent to the authors.

References

- 1.Lai J, Almazan E, Le T, Taylor MT, Alhariri J, Kwatra SG. Demographics, cutaneous manifestations, and comorbidities associated with progressive cutaneous sarcoidosis: a retrospective cohort study. Medicines (Basel) 2023;10(10):57. doi: 10.3390/medicines10100057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burke RR, Rybicki BA, Rao DS. Calcium and vitamin D in sarcoidosis: how to assess and manage. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;31(4):474–484. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1262215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bargagli E, Maggiorelli C, Rottoli P. Human chitotriosidase: a potential new marker of sarcoidosis severity. Respiration. 2008;76(2):234–238. doi: 10.1159/000134009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kubaisi B, Abu Samra K, Foster CS. Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener’s disease): An updated review of ocular disease manifestations. Intractable Rare Dis Res. 2016;5(2):61–69. doi: 10.5582/irdr.2016.01014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]