Abstract

The overexpression and amplification of HER2 occurs in breast cancer. However, the mechanism of HER2 action in tumor has not yet been elucidated. HER2 can be degraded by the UPS system, and several HER2-associated E3s have been identified, but the DUB for HER2 has not yet been uncovered. Targeted therapy against HER2 has achieved impressive efficacy in patients with HER2-positive breast cancer. Herein, using MTS, Western blot, Co-IP, colony formation, RT‒qPCR, EdU, flow cytometry, immunofluorescence assays and xenograft model, we elucidated that USP7 deletion inhibited the growth of HER2-positive breast cancer cell by decreasing HER2 protein abundance. We found that USP7 was highly expressed in HER2-positive breast cancer and the expression of USP7 and HER2 was positively correlated. USP7 overexpression accelerated cell cycle progression. Mechanistically, USP7 interacted with HER2 and decreased HER2 ubiquitination to stabilize its expression. Moreover, USP7 knockdown inhibited tumor growth in vivo and in vitro. In addition, HER2 overexpression partially reversed cell growth inhibition induced by USP7 inhibition. Analyses of clinical samples revealed that USP7 overexpression was associated with poor prognosis in patients with HER2+ breast cancer. Thus, this study revealed that USP7, as a DUB of HER2, may be a potential therapeutic target for patient with HER2+ breast cancer.

Keywords: USP7, HER2 Positive breast cancer, Ubiquitination, Growth

Introduction

Female breast cancer is one of the most prevalent cancers in the world and has one of the highest morbidity and mortality rates [1]. Breast cancer can be divided into four categories according to molecular type: HER2-positive (HER2+), luminal A, luminal B, and basal-like [2]. Approximately 25-30 % of breast cancers exhibit HER2 protein overexpression, either through gene amplification or through transcriptional dysregulation, resulting in worse biological behavior and a poorer prognosis. However, in recent years, with advances in HER2-targeted therapies [3], the overall survival rates of patients diagnosed with HER2-positive breast cancer have increased [4,5].

HER2, a proto-oncogene located on chromosome 17 and encoded by ERBB2, is a member of the EGFR family, which comprises four distinct members: HER1 (EGFR), HER2, HER3, and HER4 [6]. Studies have provided insight into the mechanisms of tumorigenesis and development that are dependent on abnormalities in various ERBB signaling pathways [7]. Through interactions with growth factors, HER2 is phosphorylated, activating downstream kinases. HER2 comprises four plasma membrane-bound receptor tyrosine kinases and participates in intracellular signaling pathways that are involved in cell proliferation, survival, migration and polarization. Mechanism of HER2-induced tumor formation include hyperactivation and overexpression of HER2. Numerous studies have identified the inhibition of tumor development through HER2 degradation as an effective therapeutic strategy. HER2 can be regulated by ubiquitin-mediated degradation through the ubiquitin‒proteasome system (UPS) and plays an important role in tumorigenesis and development [[8], [9], [10]]. Although several E3s have been shown to regulate HER2 stability, the role of deubiquitinating enzyme (DUB) remains unknown.

The UPS is one of the major pathways of protein degradation in cells [11,12]. Deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) play crucial role by catalyzing the reversal of the ubiquitination process [[13], [14], [15]]. Ubiquitin-specific protease 7 (USP7), initially identified as a herpes simplex virus-interacting protein, is alternatively referred to as herpesvirus-associated ubiquitin-specific protease (HAUSP). USP7 has been shown to deubiquitinate to enhance the stability of numerous proteins implicated in various oncogenic pathways. Numerous tumor proteins cooperate with USP7 to drive malignant tumor development. USP7 has been shown to be a tumor promoter and therapeutic target for tumor [[16], [17], [18]].

In this study, we found that USP7, a DUB of HER2, induced HER2-positive cancer cell proliferation via the inhibition of HER2 ubiquitination. Furthermore, USP7 was overexpressed in breast cancer tissues, indicating that USP7 may be a critical therapeutic target in patients with HER2-positive breast cancer.

Materials and methods

Breast cancer tissue samples

Fresh tissue samples, including para-cancerous and tumor tissues, were collected from breast cancer patients. All procedures were performed with the approval of the Medical Ethics Committee of Guangzhou Institute of Cancer Research, the Affiliated Cancer Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University (2021-SZ31). The samples were embedded in paraffin and sectioned using a slicer and analyzed by HE staining and immunohistochemical staining.

Cell culture and reagents

The following cell lines were purchased from ATCC: SK-BR3, BT474, and HEK293T. HEK293T cell was cultured in DMEM containing 10 % fetal bovine serum. BT474 cell was grown in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10 % fetal bovine serum. SK-BR3 cell was cultured in McCoy’s 5A medium supplemented with 10 % fetal bovine serum. All the cells were cultured at 37°C with 5 % CO2.

Antibodies and reagents

P5091 (S7132), MG132 (S2619) and cycloheximide (CHX) (S7418) were obtained from Selleck (TX, USA). The following antibodies were purchased from CST (Beverly, MA): anti-HER2 (2165), anti-HAUSP (USP7, 4833), anti-K48-linkage-specific polyubiquitin (8081), anti-DYKDDDDK tag (14793), anti-HA tag (3724), anti-MYC tag (9402), anti-PARP (9542), anti-p27 (3686), anti-CDK4 (12790), anti-GAPDH (2118), anti-Cyclin D1 (2922). Control siRNA and USP7 siRNA were obtained from Gemma (Jiangsu, China). An MTS kit was obtained from Promega (Peking, China).

Western blot and Co-IP

The protocols used for protein blotting and immunoprecipitation are detailed in our previous publications [16,19,20]. Protein blotting assays were performed according to standard procedures. Similar amounts of total protein in cell lysate samples were separated on a 12 % SDS‒PAGE gel and transferred to a PVDF membrane. The PVDF membrane was blocked with 5 % skim milk for one hour, followed by incubation with the appropriate primary and secondary antibodies. X-ray film was subsequently used to obtain images of the fluorescence produced by the interaction between the ECL reagent and the secondary antibody. Co-IP experiments were carried out following the protocol provided with the immunoprecipitation kit. Firstly, the magnetic beads were incubated with the antibody overnight on a rotary shaker to ensure that the antibody was completely absorbed by the beads. Next, excess free antibody was removed, and the antibody-prepared magnetic beads were co-incubated with cell lysates for 2 h. The magnetic beads were rinsed with PBST to eliminate any surplus free lysate, after which the interacting proteins were dissociated in a 70°C water bath and isolated using high-speed centrifugation (13,250 rpm).

Transfection of plasmids and siRNAs

Transfection methods were performed according to our previous reports [21]. Breast cancer cells were digested and subsequently cultured in 6-well plates or Petri dishes. Following cell adhesion, transfection was carried out using a plasmid concentration ranging from 0.5 to 1 µg/ml. Transfection mixtures contained 500 µl of Opti-MEM + 2.5 µl of P 3000 + 2.5 µl of Lipofectamine 3000 + 2.5 µg of plasmid. The mixtures were allowed to rest for 15 min, after which 2 ml of complete medium was added. The mixture was then added to cells and then replaced after 6‒8 h; the cells were then incubated for another 48 h. The transfection efficiency was assessed prior to subsequent experiments. For the experiment in which the expression levels of target genes were downregulated by siRNA interference, breast cancer cells were also seeded in a Petri dish for 24 h, and the transfection mixture was prepared with 500 µl of RPMI Opti-MEM + 5 µl of Lipofectamine RNAiMAX + 10 µl of siRNA and incubated for 15 min. Then, the mixture was added to the cells, and the cells were cultured for 48‒72 h. siRNAs were purchased from Suzhou Gemma (Jiangsu, China).

Cell proliferation assay

Cell proliferation assays included a cell viability assay, a cell cloning assay and an EdU staining assay. To determine cell viability, cells were seeded into 96-well plates for 24 h and then treated with drugs or siRNAs for 48, 72, or 96 h, and cell viability was measured using MTS. EdU experiments were performed according to the instructions provided with the EdU reagent (RiboBio, Guangzhou, China) and our previously reported procedure [22]. The cells were digested and seeded on slides in small chambers. After the cells were treated, proliferation was assessed using a kit. The above experiments were repeated three times.

Clonogenic assay

Cell cloning assays are frequently utilized to evaluate the extended proliferation potential of cells. Initially, breast cancer cells were seeded in 6-well plates and treated with P5091, siRNA, or a virus after adhering, and after 24-48 h of treatment, the cells were digested and seeded in new 6-well plates, ensuring that the same number of cells were present in each well. After the formation of colonies, the cells were fixed with paraformaldehyde and stained with crystal violet.

Flow cytometry

Cell cycle and apoptosis analyses were performed via flow cytometry, as described previously [19]. After the cells were subjected to treatment with P5091 or siRNA, trypsin digestion was performed, followed by centrifugation at 1000 rpm. The collected cells were then fixed using 75 % ethanol. Subsequently, a single wash with PBS was carried out, and the cells were processed with the cell cycle detection kit. Subsequently, flow cytometry analysis was employed for assessment.

For the collection of samples intended for apoptosis analysis, the procedure was similar to that of the cell cycle assay sample collection. However, the key distinction was that after collection, the cell pellet was processed with an apoptosis detection kit. After 15 minute incubation period, the stained cells were analyzed by means of flow cytometry.

Immunofluorescence assay

Treated cells were fixed with 4 % paraformaldehyde for 30 min, permeabilized with 0.5 % Triton X-100 (nonionic surfactant) for 10 min, blocked with 5 % bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 30 min, and incubated with a primary antibody for 4 h overnight. The following day, after 3 washes with PBS, a fluorescent secondary antibody was added, and the samples were incubated for 1 h in the dark. After washing with PBS, the cells were left to dry at room temperature for 5 min, and DAPI was added. The cells were observed via confocal microscopy.

Real-time RT‒qPCR

This experiment was performed according to the procedure we previously reported [10]. Total RNA from breast cancer cells was extracted using RNA TRIzol according to our previous reports, after which RNA purity and concentration were determined at 260/280 nm. Extracted RNA samples brought to a uniform concentration with nuclease-free water, and first-strand cDNA was synthesized via reverse transcription with 1000 ng of RNA using the Prime Script RT Master Mix Kit. The mRNA levels of HER2, USP7, and GAPDH were analyzed via real-time quantitative PCR using the SYBR Premix Ex Taq Kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Animal model

BAL B/c nude female mice (5–6 weeks of age and 18–20 g) were selected for the animal experiments. All the animals were kept at a constant temperature of 22 degrees Celsius, a relative humidity of 50 %, and a light/dark cycle of 12/12 h. All animal experiments were approved by the institutional animal care and use committees of Guangzhou Medical University(GY2021-025). We constructed an SK-BR3-HER2-OE (overexpression) stabled cell line. After the overexpression efficiency was verified, the SK-BR3-Mock cell line and SK-BR3-HER2-OE cell line were inoculated subcutaneously into mice at a concentration of 3 × 106/100 µl of PBS. At approximately 5–7 days, when the tumor size was approximately 50 mm, mice inoculated with both SK-BR3-Mock and SK-BR3-HER2-OE cells were respectively divided into 2 groups, one of which was randomly selected for the administration of P5091 (20 mg/kg/d) for 15 consecutive days. Tumor growth was assessed regularly.

Immunohistochemical staining

Xenografts were fixed and embedded in paraffin according to our previously reported procedure and then sectioned [21]. A MaxVision Kit (Maixin Biol) was used to process the tumor sections, which were then incubated with HER2 and Ki67 antibodies for immunohistochemical staining. Fifty microliters of MaxVisionTM reagent was applied, followed by staining with 0.05 % diaminobenzidine and 0.03 % H2O2 in 50 mM Tris-HCl. The presence of the primary antibody was visualized with DAB.

Statistical analysis

The data are presented as means and standard deviations (SDs) of three independent replicates. Paired/unpaired Student's t test or one-way ANOVA was performed to determine statistical probabilities. Survival curves were statistically analyzed via the Kaplan‒Meier method using SPSS 16.0 and GraphPad Prism 8.0, with p values less than 0.05 considered significant.

Results

USP7 overexpression in HER2+ breast cancer is associated with poor prognosis

The stability of the HER2 protein is controlled by the UPS. Several E3s, such as SMURF1, SMURF2, STUB1, PTPN18, and Cbl, have been reported to be involved in the ubiquitination-mediated degradation of HER2 [9,[23], [24], [25], [26], [27]]. However, the DUB of HER2 has not been identified. To identify the HER2 DUB, we analyzed a published dataset [28] and found that the mRNA level of USP7 was significantly greater in breast cancer tissue than in normal tissue (Fig. 1A). Next, we analyzed the effect of high expression of USP7 on the overall survival of patients. High expression of USP7 shortened the overall survival of patients with HER2-positive breast cancer and breast cancer with lymph node metastasis. (Fig. 1B, C) [29]. The immunohistochemistry results were consistent with the mRNA results, and the immunohistochemistry results revealed that HER2 and USP7 were highly expressed in cancer tissues (Fig. 1D-F) and that they were positively correlated (Fig. 1G). And, we evaluated the expression level of USP7 upon HER2 expression level (HER2 low-expression and HER2 high-expression). It can be seen that USP7 was also increased in breast cancer patients with high HER2 expression (Fig. 1H). These findings suggested that USP7 is overexpressed in HER2+ cancer tissues and may be a DUB for HER2. upregulation of USP7 expression is closely associated with HER2+ breast carcinogenesis and influences HER2+ tumor development.

Fig. 1.

USP7 overexpression in HER2+ breast cancer is associated with poor prognosis. (A)The mRNA expression of USP7 was examined in human clinical samples sourced from a publicly available microarray dataset. (https://docs.gdc.cancer.gov/Data/Bioinformatics_Pipelines/Expression_mRNA_Pipeline). (B, C) Overall survival curves of USP7 low and high expression in patients with different types of breast cancer. (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) and (https://ega-archive.org/). (D) Images displaying the expression of USP7 and HER2 in human breast cancer tissues and adjacent tissues from clinical samples are presented. (E, F) Quantification of HER2 and USP7. Data were analyzed by unpaired t-test. (G) To analyze the correlation between HER2 and USP7 protein levels. (H) Quantification of USP7 upon HER2 expression.

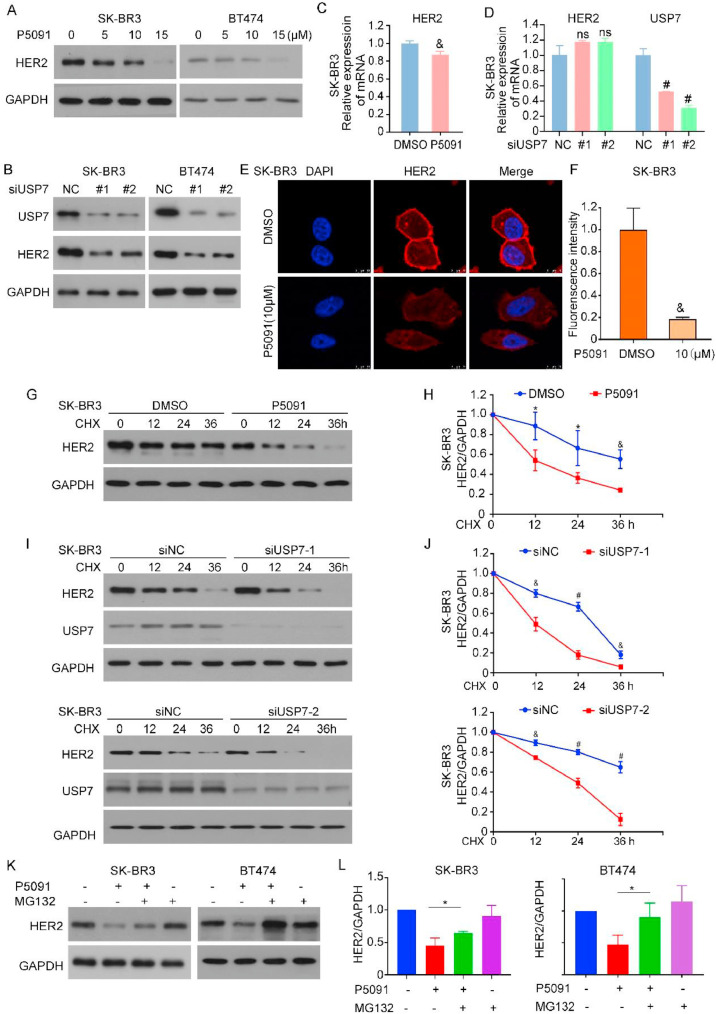

USP7 deletion promotes HER2 protein degradation

To further investigate the relationship between USP7 and HER2, we examined the effect of USP7 on HER2 expression levels. We used a USP7 inhibitor and two different knockdown tools to inhibit USP7 expression in HER2-positive breast cancer cells (SK-BR3 and BT474). The inhibition and knockdown of USP7 led to a reduction in HER2 protein levels (Fig. 2A, B). Both the synthesis of proteins through transcription and the degradation of proteins influences protein levels. We first performed a RT‒qPCR experiment to analyze the transcription level of HER2. After USP7 knockdown, the effect on the transcription level of HER2 was little and unstable (Fig. 2C, D). Immunofluorescence results using confocal microscopy showed a decrease in HER2 expression after USP7 inhibition. We then speculated that USP7 might regulate the level of HER2 through the protein degradation pathway (Fig. 2E, F). Next, we treated the cells with CHX, a protein synthesis inhibitor, to determine the half-life of the HER2 protein. In the presence of protein synthesis inhibition, treatment with P5091 (Fig. 2G, H) or the direct knockdown of USP7 shortened the half-life of HER2 (Fig. 2I, J). We hypothesized that USP7 facilitates the degradation of HER2 through proteasome-mediated protein degradation. The use of the proteasome inhibitor MG132 rescued the decrease in HER2 protein levels caused by USP7 deletion, suggesting that HER2 degradation may occur upon USP7 loss (Fig. 2 K, L). These results suggested that the level of USP7 plays an important role in regulating HER2 degradation.

Fig. 2.

USP7 deletion promotes the degradation of HER2 protein. (A) Cells were exposed to the USP7 inhibitor for a duration of 24 hours. Western bolt assay to analyze HER2 and GAPDH protein changes in cells. (B) Cells were treated with USP7 siRNA for 72 h for HER2, USP7 and GAPDH proteins. (C, D) Total RNA was extracted and HER2 expression was analyzed by RT-qPCR (&P<0.01, #P<0.001). (E) Immunofluorescence images were taken using a confocal microscope. (F) Fluorescence intensity of the images was quantified using Image J (&P<0.01). (G, I) Cells were treated with USP7 inhibitor/siRNA and CHX (50 μg/ml), and protein lysates from cells treated for 0 h, 12 h, 24 h and 36 h were collected. (H, J) The grey values of the western blot bands were analyzed using Image J (*P<0.05, &P<0.01, #P<0.001). (K) Cells were treated with P5091 and MG132. HER2 protein levels were detected using Western Blot. (L) The HER2 bands of the (K) were analyzed for grey values using Image J (*P<0.05).

USP7 regulates HER2 stability by removing K48 ubiquitin

Given that USP7 is involved in regulating HER2 protein degradation and stability, to investigate the specific regulatory mechanisms of USP7 and HER2 and how they interact, we performed Co-IP experiments using HER2 and USP7 antibodies, and the results revealed that USP7 interacted with HER2 in HER2-positive breast cancer (Fig. 3A, B). Moreover, the fluorescence colocalization experiments with breast cancer samples confirmed this finding. Immunofluorescence experiments revealed that endogenous HER2 and HA-labeled exogenous USP7 colocalized at the cell membrane and in the cytoplasm (Fig. 3C). We hypothesized that USP7 stabilized the level of HER2 through deubiquitination. To test this, we evaluated the level of HER2 ubiquitination by Co-IP after treating cells with P5091 and siRNA. The inhibition or knockdown of USP7 resulted in a significant increase in the level of K48-linked polyubiquitination (Fig. 3D, E). To further explore the structural basis for the interaction between the two proteins, we constructed a FLAG-tagged HER2 truncation mutant (Fig. 3F). Co-IP and Western blot results revealed that HA-tagged USP7 bound to both the N-terminus and C-terminus of the HER2 protein (Fig. 3G). Similarly, full-length FLAG-HER2 can bind to different truncations of USP7 (Fig. S3B). These results indicated that the decrease in HER2 expression induced by USP7 deletion resulted from the ubiquitination-mediated degradation of HER2. These findings suggested that USP7 acts as a DUB to mediate HER2 deubiquitination and stabilization in HER2-positive tumor cells.

Fig. 3.

USP7 regulates HER2 stability by removing K48 ubiquitin. (A, B) Protein lysates were isolated, followed by a Co-IP assay that utilized protein lysates to investigate the relationship between USP7 and HER2. (C) SK-BR3 cells were transfected with USP7 plasmid with HA tag, and confocal microscopy was used to locate the position of HER2 and USP7. (D) Cells were treated with P5091 for 24 hours and MG132 for 6 hours. Protein lysates were collected and K48 expression levels. (E) Cells treated with USP7 siRNA, and immunoprecipitation experiments for HER2 were performed to examine changes in the expression levels of K48. (F) Schematic diagram of FLAG (HER2) full-length plasmids and truncated mutant plasmids. (G) Co-IP experiments were performed using HA antibodies. Western blot assay was performed to analyze the changes of FLAG, HA and GAPDH proteins.

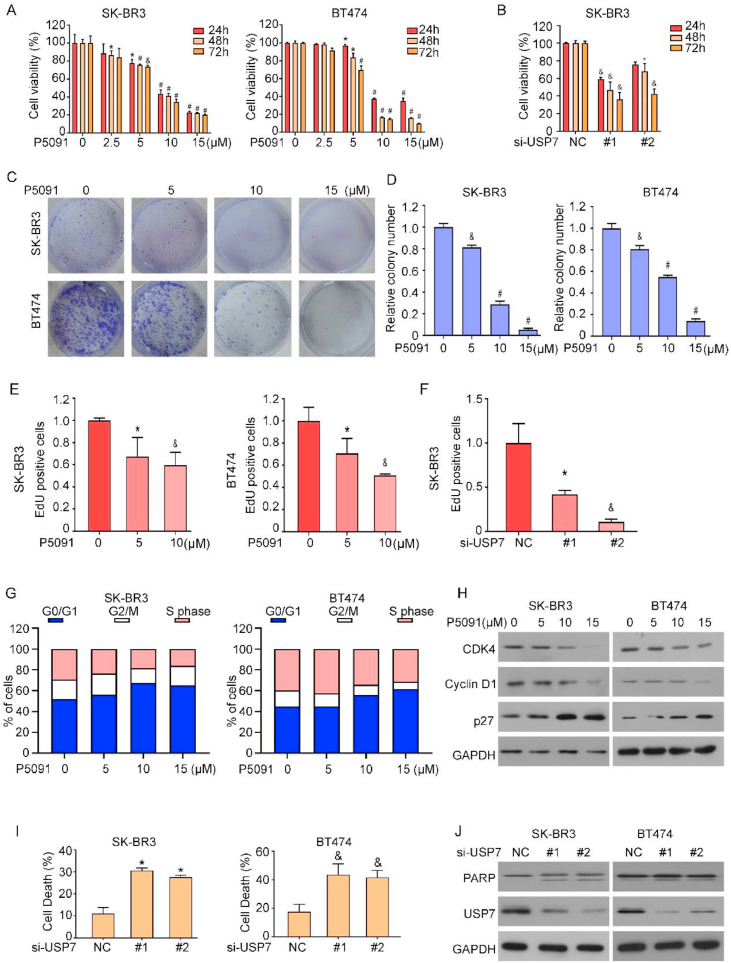

USP7 deficiency leads to cancer growth inhibition

After confirming that USP7 can regulate the level of HER2, we explored the effect of USP7 on cancer cell growth. We measured and evaluated the viability and proliferation ability of tumor cells using MTS, colony formation and EdU assays. The viability of the cells was significantly suppressed when the level of USP7 was decreased by treatment with siRNA or inhibitors (Fig. 4A-F, Fig.S2A, B), suggesting that high USP7 expression promoted HER2-positive tumor growth. To explore the mechanism of USP7-mediated HER2-positive tumor growth, we used flow cytometry assay. The results of cell cycle experiments revealed that USP7 inhibition increased the number of cells in the G0/G1 phase (Fig. 4G, Fig.S1A). To verify this conclusion, we analyzed the relevant cell cycle proteins via Western blot (Fig. 4H), which revealed that the expression of the Cyclin D1 and CDK4 proteins was decreased and the expression of p27 was increased with increasing drug concentration. Next, we explored the association between USP7 deletion and the occurrence of apoptosis. Flow cytometry analysis revealed that the inhibition of USP7 led to an increase in the cellular apoptosis rate (Fig. 4I, Fig.S1B). We examined the protein expression levels of PARP, which are widely recognized as apoptosis markers (Fig. 4J). The above results showed that the growth inhibition caused by USP7 deletion.

Fig. 4.

USP7 deficiency leads to cancer growth inhibition. (A) Cell viability was assessed using the MTS assay. Comparisons were made with each vector control (*P<0.05, &P<0.01, #P<0.001). (B) Cells were treated with USP7 siRNA and cell viability was determined by applying MTS assay (*P<0.05, &P<0.01, #P<0.001). (C) SK-BR3 and BT474 were treated with different doses of P5091 and cell clone formation assay was performed. (D) The results of the cell cloning assay were counted *P<0.05, &P<0.01, #P<0.001. (E) The SK-BR3 cells underwent treatment with P5091 followed by staining with Edu, and the ensuing experimental outcomes were subjected to statistical analysis (*P<0.05, &P<0.01, #P<0.001). (F) After transfection of SK-BR3 cells with USP7 siRNA, EDU staining was performed and the results were statistically processed (*P<0.05, &P<0.01, #P<0.001). (G) Flow cytometry was applied to detect the cell cycle. (H) Western blotting was performed to detect changes in cell cycle-related proteins. (I) Apoptosis was detected by flow cytometry and Western blotting of protein lysates. Comparisons were made with each vector control (n=3, *P<0.05, &P<0.01, #P<0.001). (J) Western blotting for apoptosis-related proteins.

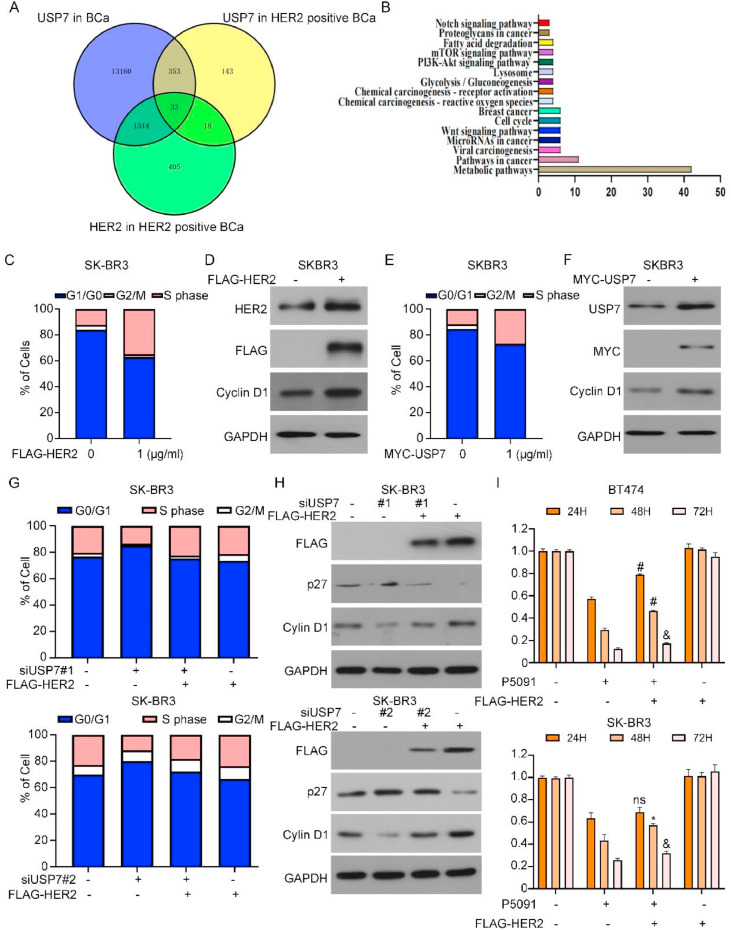

USP7 mediates HER2-associated cell cycle regulation

To further explore the role of USP7 in HER2-positive breast cancer, we conducted an analysis utilizing multi-omics to investigate the signaling pathways associated with HER2 and USP7. Our findings revealed 33 genes that could serve as promising targets of USP7 in HER2-positive breast cancer. Subsequent pathway enrichment analyses revealed that these 33 genes were involved in a range of pathways (Fig. 5A, B). Cell cycle dysregulation leads to uncontrolled tumor growth, especially when the cellular G1/S-phase transition is dysregulated. Changes in the level of HER2 affect two downstream cell cycle regulators, Cyclin D1 and p27 [30,31]. Thus, after the introduction of FLAG-HER2 overexpression plasmids into breast cancer cells, flow cytometry analysis revealed a reduction in the G1 phase cell population and an increase in S-phase cells (Fig. 5C). The Western blot results also revealed that the level of the cyclin D1 was increased (Fig. 5D and S3C). After transfecting cells with the wild-type MYC-USP7 plasmid, we obtained the same result: there was an increase in the G1/S phase transition in tumor cells (Fig. 5E, F). These results suggested that USP7 may influence the cell cycle through HER2. To test this hypothesis, we transfected FLAG-HER2 into cells with suppressed USP7 expression, and the results revealed that HER2 overexpression reversed the cell cycle arrest caused by USP7 deletion and induced cell proliferation (Fig. 5G, H, Fig.S1C). We employed MTS assay to examine alterations in cell viability following simultaneous treatment of cells with P5091 and FLAG-HER2. Overexpression of HER2 partially reversed the reduced cell viability induced by USP7 inhibition (Fig. 5I). Overall, we concluded that USP7-mediated tumorigenesis development is closely related to the level of HER2.

Fig. 5.

USP7 mediates HER2-associated cell cycle regulation. Signaling pathways associated with HER2 and USP7 were examined by multi-omics analysis (B) Pathway enrichment analysis showed that these 33 genes were involved in a series of pathways. (C) HER2 plasmids with FLAG tags were transfected intoSK-BR3 and flow cytometry analysis was performed to detect the cell cycle. (D) Analyzed for cell cycle-associated proteins using Western blotting. (E) Flow cytometry analysis was performed to detect cell cycle. (F) Analyzed for cell cycle-associated proteins by Western blotting. (G) SK-BR3 cells co-treated with USP7 siRNA and FLAG-HER2 were collected and analyzed for cell cycle by flow cytometry. (H) Cell cycle-related protein changes were detected using Western blot assays. (I) Detection of breast cancer cell viability using the MTS method (P5091vs. P5091+FLAG-HER2, *P<0.05, &P<0.01, #P<0.001).

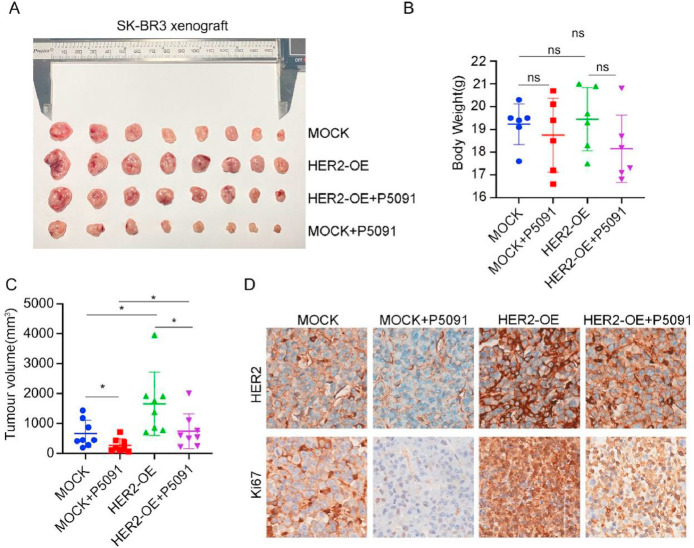

USP7 depletion inhibits tumor growth in vivo

After finding that USP7 deletion inhibits tumor cell growth in vitro, we investigated whether USP7 inhibits cell growth in vivo. For this purpose, we observed tumor growth via xenograft model. Moreover, to investigate the role of HER2 in tumor growth, we constructed SK-BR3-Mock and SK-BR3-HER2-overexpressing stably transfected cell lines using the breast cancer cell line SK-BR3. Compared with the control, the USP7 inhibitor P5091 effectively inhibited tumor growth, while cells overexpressing HER2 promoted tumor growth and reversed the inhibitory effect of P5091 on tumor growth (Fig. 6A-C). The immunohistochemistry results revealed that the expression of Ki67, which is associated with tissue proliferation, was increased after the overexpression of HER2, but was decreased after treatment with P5091 (Fig. 6D). These results demonstrated that USP7 inhibition induced tumor growth in vivo.

Fig. 6.

USP7 depletion inhibits tumor growth in vivo. (A) Tumor images of breast cancer stable transition cells SK-BR3-Mock and SK-BR3 HER2-Overexpression (HER2-OE) after subcutaneous tumor formation and treatment with P5091 (20 mg/kg/d). (B) Weight of mice after tumor formation. (n=8, *P<0.05, &P<0.01, #P<0.001). (C) Comparison of tumor volumes of SK-BR3 cell-forming tumors. (n=8, *P<0.05, &P<0.01, #P<0.001). (D) IHC of paraffin-embedded tumor tissue using Ki67 and HER2 antibodies. Representative images are 40 × .

Discussion

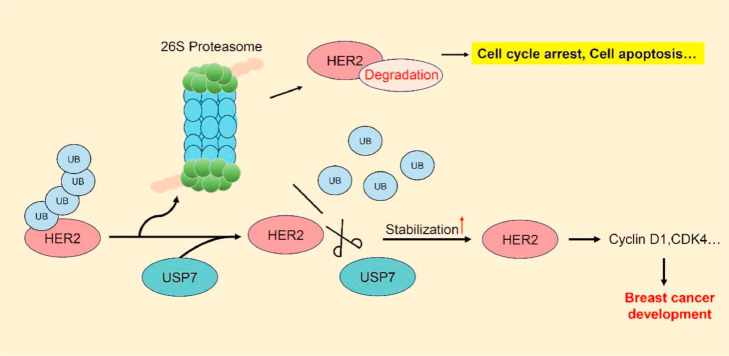

As the number of breast cancer patients increases annually, breast cancer has become one of the three major cancers in the world, seriously threatening the health of women worldwide [32]. HER2-positive breast cancer accounts for approximately 25∼30 % of total cases, and the clinical treatment of breast cancer is HER2-targeted therapy [33]. HER2 has been shown to be an effective target for the treatment of breast cancer. The deubiquitinating enzyme USP7, a key component of the UPS [34,35], has been identified as a critical regulator of HER2, impacting the progression of HER2-positive tumors beyond its traditional role as a therapeutic target for HER2-positive breast cancer (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Mechanistic simulation of USP7 regulation of HER2 ubiquitination modification. The ubiquitin protein is activated and linked to the substrate protein HER2 through a cascade reaction of ubiquitination. The UB-tagged substrate protein HER2 is recognized and degraded by the 26S proteasome. USP7 is an important member of the UPS system. USP7 enters into the process of ubiquitination of HER2 and removes the UB that is linked to HER2. HER2 that is not tagged by UB is not recognized and degraded by the 26S proteasome, and the stability of HER2 in tumor cells is increased, which promotes cell cycle progression, facilitates tumorigenesis, and maintains tumor progression.

USP proteins are the largest component of the DUB family. Therefore, we examined the expression of USP proteins via public databases and analyzed them on the basis of existing datasets and found that the mRNA level of USP7 was increased in breast cancer tissues. USP7 was positively correlated with HER2 levels, with elevated USP7 expression being linked to adverse patient outcomes. Notably, both USP7 and HER2 levels were increased in breast cancer tumor tissues and were positively correlated. All of the above findings indicate that there is a close relationship between HER2 and USP7.

Whether there is a correlation between USP7 and HER2 in tumors, both of which are highly expressed, what kind of regulatory relationship exists between them, We explored the molecular mechanism involving USP7 and HER2. We first treated cells with a USP7 inhibitor or knocked down USP7 to observe HER2 expression. When USP7 was downregulated, HER2 expression tended to be low. However, the effect of USP7 knockdown on HER2 transcription was not stable. After treating cells with a CHX protein synthesis inhibitor, USP7 deletion promoted HER2 degradation. The HER2 degradation caused by USP7 inhibition was blocked by MG132, a proteasome inhibitor, suggesting that USP7 degrades HER2 through the proteasome system and plays an important role in maintaining HER2 protein stability.

Overall, we can tentatively infer that USP7 may be a deubiquitinating enzyme. We performed Co-IP experiments and confirmed a strong interaction between endogenous HER2 and USP7. Intriguingly, USP7 is capable of interacting with every structural domain of HER2. We hypothesize that this interaction may be associated with the nuclear localization of a fraction of HER2 [[36], [37], [38], [39], [40], [41], [42]]. HER2 is known to translocate into the nucleus via nuclear localization signals (NLS), entering in its full-length conformation [[42], [43], [44]]. It is plausible that USP7 not only specifically binds to transmembrane HER2 at the cell membrane but also engages with nuclear HER2. This dual-binding capacity may account for the observed interaction of USP7 with both the intracellular and extracellular domains of HER2. Similarly, HER2 can bind to both the N-terminal and C-terminal ends of USP7. The TRAF-like structural domain at the N-terminal end of the USP7 protein is the main site of substrate binding, and P53 was the first substrate found in this domain [45,46]. The C-terminal structural domain of USP7 is a tandem of Ubl structural domains [47]. As research progressed, more and more substrates were found to be recognized and specifically bound to the C-terminal UBL, such as P53, which is recognized by the UBL domain of USP7 [48]. HER2, perhaps like P53, can be recognized and bound by both the N-terminal and C-terminal domains of USP7. The degree of ubiquitination of HER2 increased after USP7 knockdown, and USP7 removed the K48 ubiquitin from HER2. We confirmed that USP7 is the deubiquitinating enzyme of HER2 and that USP7 can inhibit proteasome system-mediated HER2 degradation, stabilize the level of HER2 and maintain the growth of tumor cells. We then assessed whether USP7 affects the biological function of HER2-positive breast cancer. Our experimental results revealed that the USP7 inhibitor P5091 significantly inhibited tumor cell activity in a concentration-dependent manner, and the same results were obtained when cells were transfected with siUSP7 to knockdown USP7. Moreover, USP7 inhibitor significantly suppressed the growth of HER2-positive breast cancer cells in vivo. High expression of USP7 and HER2 promoted the progression of the tumor cell cycle, suggesting that the effect of USP7 may depend on HER2 expression. To test this hypothesis, we designed a set of reversal experiments. The results revealed that HER2 overexpression reversed the cell cycle arrest caused by USP7 inhibition.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our results suggest that USP7 regulates the ubiquitination of HER2 by removing the ubiquitin on HER2, thereby contributing to stabilizing the expression level of HER2 in tumor cells. USP7 might serve as a new target for the treatment of HER2-positive breast cancer.

Abbreviations

| BCa | Breast cancer |

| CDK4 | Cyclin-dependent kinase 4 |

| CHX | Cycloheximide |

| DUBs | Deubiquitinases |

| E3s | E3 Ubiquitin Ligases |

| GAPDH | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase |

| HAUSP | herpesvirus-associated ubiquitin-specific protease |

| HER2 | Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 |

| HER2-OE | HER2 overexpression |

| PTM | Post-translational modifications |

| RT‒qPCR | Quantitative Real-time PCR |

| shRNA | Short hairpin RNA |

| siRNA | Small interfering RNA |

| UPS | Ubiquitin proteasome system |

| USP7 | Ubiquitin-specific protease 7 |

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82373327, 82403028, 82373450, 82172648), the Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (2021A1515110868, 2023A1515010209), Innovation team of general Universities in Guangdong Province (2022KCXTD021), the Science and Technology Program of Guangzhou(2023A03J0427, 2024A03J0552), the Guangzhou clinical high-tech program (2024C-GX18).

Availability of data and materials

Data will be made available on request.

Ethics statement and consent to participate

This research was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Guangzhou Institute of Cancer Research, the Affiliated Cancer Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University (2021-SZ31) and were performed with the full informed consent of the subjects. All animal experiments were approved by the institutional animal care and use committees of Guangzhou Medical University(GY2021-025).

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Xiaoyue He: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Conceptualization. Xiaohong Xia: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Conceptualization. Ziying Lei: Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Conceptualization. Mengfan Tang: Methodology, Data curation. Jiangyu Zhang: Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Conceptualization. Yuning Liao: Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Conceptualization. Hongbiao Huang: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Conceptualization.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors do not have competing interests to declare.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.neo.2025.101192.

Contributor Information

Jiangyu Zhang, Email: Superchina2000@foxmail.com.

Yuning Liao, Email: 2019990003@gzhmu.edu.cn.

Hongbiao Huang, Email: huanghongbiao@gzhmu.edu.cn.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Sung H., Ferlay J., Siegel R.L., Laversanne M., Soerjomataram I., Jemal A., et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: Cancer J. Clin. 2021;71(3):209–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carey L.A., Perou C.M., Livasy C.A., Dressler L.G., Cowan D., Conway K., et al. Race, breast cancer subtypes, and survival in the Carolina breast cancer study. JAMa. 2006;295(21):2492–2502. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.21.2492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dekker TJA. HER2-Targeted therapies in HER2-low-expressing breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020;38(28):3350–3351. doi: 10.1200/JCO.20.00657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pernas S., Tolaney SM. Clinical trial data and emerging strategies: HER2-positive breast cancer. Breast. Cancer Res. Treat. 2022;193(2):281–291. doi: 10.1007/s10549-022-06575-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marra A., Chandarlapaty S., Modi S. Management of patients with advanced-stage HER2-positive breast cancer: current evidence and future perspectives. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2024;21(3):185–202. doi: 10.1038/s41571-023-00849-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moasser MM. The oncogene HER2: its signaling and transforming functions and its role in human cancer pathogenesis. Oncogene. 2007;26(45):6469–6487. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arteaga C.L., Engelman JA. ERBB receptors: from oncogene discovery to basic science to mechanism-based cancer therapeutics. Cancer Cell. 2014;25(3):282–303. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.02.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu J., Zhu T., Zhao R., Ren W., Zhao F., Liu J. Elucidating molecular mechanisms and therapeutic synergy: irreversible HER2-TKI plus T-dxd for enhanced anti-HER2 treatment of gastric cancer. Off. J. Int. Gastric Cancer Assoc. Jpn. Gastric Cancer Assoc. 2024 doi: 10.1007/s10120-024-01478-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang Y., Sun Q., Deng Z., Shi W., Cheng H. Cbl induced ubiquitination of HER2 mediate immune escape from HER2-targeted CAR-T. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 2023;37(10) doi: 10.1002/jbt.23446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xia X., Hu T., He X., Liu Y., Yu C., Kong W., et al. Neddylation of HER2 inhibits its protein degradation and promotes breast cancer progression. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2023;19(2):377–392. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.75852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yau R., Rape M. The increasing complexity of the ubiquitin code. Nat. Cell Biol. 2016;18(6):579–586. doi: 10.1038/ncb3358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Swatek K.N., Komander D. Ubiquitin modifications. Cell Res. 2016;26(4):399–422. doi: 10.1038/cr.2016.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Keijzer N., Priyanka A., Stijf-Bultsma Y., Fish A., Gersch M., Sixma TK. Variety in the USP deubiquitinase catalytic mechanism. Life Sci. Alliance. 2024;7(4) doi: 10.26508/lsa.202302533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Estavoyer B., Messmer C., Echbicheb M., Rudd C.E., Milot E., Affar EB. Mechanisms orchestrating the enzymatic activity and cellular functions of deubiquitinases. J. Biol. Chem. 2022;298(8) doi: 10.1016/j.jbc.2022.102198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dewson G., Eichhorn P.J.A., Komander D. Deubiquitinases in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2023;23(12):842–862. doi: 10.1038/s41568-023-00633-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xia X., Liao Y., Huang C., Liu Y., He J., Shao Z., et al. Deubiquitination and stabilization of estrogen receptor α by ubiquitin-specific protease 7 promotes breast tumorigenesis. Cancer Lett. 2019;465:118–128. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2019.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li M., Chen D., Shiloh A., Luo J., Nikolaev A.Y., Qin J., et al. Deubiquitination of p53 by HAUSP is an important pathway for p53 stabilization. Nature. 2002;416(6881):648–653. doi: 10.1038/nature737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Javaid S., Zadi S., Awais M., Wahab A.T., Zafar H., Maslennikov I., et al. Identification of new leads against ubiquitin specific protease-7 (USP7): a step towards the potential treatment of cancers. RSC Adv. 2024;14(45):33080–33093. doi: 10.1039/d4ra06813k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liao Y., Liu Y., Xia X., Shao Z., Huang C., He J., et al. Targeting GRP78-dependent AR-V7 protein degradation overcomes castration-resistance in prostate cancer therapy. Theranostics. 2020;10(8):3366–3381. doi: 10.7150/thno.41849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu Y., Yu C., Shao Z., Xia X., Hu T., Kong W., et al. Selective degradation of AR-V7 to overcome castration resistance of prostate cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2021;12(10):857. doi: 10.1038/s41419-021-04162-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liao Y., Liu Y., Yu C., Lei Q., Cheng J., Kong W., et al. HSP90β Impedes STUB1-induced ubiquitination of YTHDF2 to drive sorafenib resistance in hepatocellular carcinoma. Adv. Sci. (Weinh) 2023;10(27) doi: 10.1002/advs.202302025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu Y., Kong W.Y., Yu C.F., Shao Z.L., Lei Q.C., Deng Y.F., et al. SNS-023 sensitizes hepatocellular carcinoma to sorafenib by inducing degradation of cancer drivers SIX1 and RPS16. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2023;44(4):853–864. doi: 10.1038/s41401-022-01003-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Luan H., Bailey T.A., Clubb R.J., Mohapatra B.C., Bhat A.M., Chakraborty S., et al. CHIP/STUB1 ubiquitin ligase functions as a negative regulator of ErbB2 by promoting its early post-biosynthesis degradation. Cancers. (Basel) 2021;13(16) doi: 10.3390/cancers13163936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gu Y., Gao H., Zhang H., John A., Zhu X., Shivaram S., et al. TRAF4 hyperactivates HER2 signaling and contributes to trastuzumab resistance in HER2-positive breast cancer. Oncogene. 2022;41(35):4119–4129. doi: 10.1038/s41388-022-02415-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xu W., Marcu M., Yuan X., Mimnaugh E., Patterson C., Neckers L. Chaperone-dependent E3 ubiquitin ligase CHIP mediates a degradative pathway for c-ErbB2/neu. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2002;99(20):12847–12852. doi: 10.1073/pnas.202365899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ren Y., Chen D., Zhai Z., Chen J., Li A., Liang Y., et al. JAC1 suppresses proliferation of breast cancer through the JWA/p38/SMURF1/HER2 signaling. Cell Death. Discov. 2021;7(1):85. doi: 10.1038/s41420-021-00426-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jia Y., Kodumudi K.N., Ramamoorthi G., Basu A., Snyder C., Wiener D., et al. Th1 cytokine interferon gamma improves response in HER2 breast cancer by modulating the ubiquitin proteasomal pathway. Mol. Ther. 2021;29(4):1541–1556. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2020.12.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jézéquel P., Gouraud W., Ben Azzouz F., Guérin-Charbonnel C., Juin P.P., Lasla H., et al. bc-GenExMiner 4.5: new mining module computes breast cancer differential gene expression analyses. Database (Oxf.) 2021:2021. doi: 10.1093/database/baab007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Győrffy B. Survival analysis across the entire transcriptome identifies biomarkers with the highest prognostic power in breast cancer. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2021;19:4101–4109. doi: 10.1016/j.csbj.2021.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Timms J.F., White S.L., O'Hare M.J., Waterfield M.D. Effects of ErbB-2 overexpression on mitogenic signalling and cell cycle progression in human breast luminal epithelial cells. Oncogene. 2002;21(43):6573–6586. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reddy H.K., Mettus R.V., Rane S.G., Graña X., Litvin J., Reddy EP. Cyclin-dependent kinase 4 expression is essential for neu-induced breast tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 2005;65(22):10174–10178. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Veronesi U., Boyle P., Goldhirsch A., Orecchia R., Viale G. Breast cancer. Lancet. 2005;365(9472):1727–1741. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66546-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maughan K.L., Lutterbie M.A., Ham PS. Treatment of breast cancer. Am. Fam. Physician. 2010;81(11):1339–1346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Clague M.J., Urbé S., Komander D. Breaking the chains: deubiquitylating enzyme specificity begets function. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2019;20(6):338–352. doi: 10.1038/s41580-019-0099-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Harrigan J.A., Jacq X., Martin N.M., Jackson SP. Deubiquitylating enzymes and drug discovery: emerging opportunities. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2018;17(1):57–78. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2017.152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cordo Russo R.I., Béguelin W., Díaz Flaqué M.C., Proietti C.J., Venturutti L., Galigniana N., et al. Targeting ErbB-2 nuclear localization and function inhibits breast cancer growth and overcomes trastuzumab resistance. Oncogene. 2015;34(26):3413–3428. doi: 10.1038/onc.2014.272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hwang S.Y., Choi S.K., Seo S.H., Jo H., Shin J.H., Na Y., et al. Specific roles of HSP27 S15 phosphorylation augmenting the nuclear function of HER2 to promote trastuzumab resistance. Cancers. 2020;12(6) doi: 10.3390/cancers12061540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Elizalde P.V., Cordo Russo R.I., Chervo M.F., Schillaci R. ErbB-2 nuclear function in breast cancer growth, metastasis and resistance to therapy. Endocr.-Relat. Cancer. 2016;23(12):T243–Tt57. doi: 10.1530/ERC-16-0360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Venturutti L., Romero L.V., Urtreger A.J., Chervo M.F., Cordo Russo R.I., Mercogliano M.F., et al. Stat3 regulates ErbB-2 expression and co-opts ErbB-2 nuclear function to induce miR-21 expression, PDCD4 downregulation and breast cancer metastasis. Oncogene. 2016;35(17):2208–2222. doi: 10.1038/onc.2015.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schillaci R., Guzmán P., Cayrol F., Beguelin W., Díaz Flaqué M.C., Proietti C.J., et al. Clinical relevance of ErbB-2/HER2 nuclear expression in breast cancer. BMC. Cancer. 2012;12:74. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-12-74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhao X., Li Y., Zhang H., Cai Y., Wang X., Liu Y., et al. PAK5 promotes the trastuzumab resistance by increasing HER2 nuclear accumulation in HER2-positive breast cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2025;16(1):323. doi: 10.1038/s41419-025-07657-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang S.C., Lien H.C., Xia W., Chen I.F., Lo H.W., Wang Z., et al. Binding at and transactivation of the COX-2 promoter by nuclear tyrosine kinase receptor ErbB-2. Cancer Cell. 2004;6(3):251–261. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Madera S., Izzo F., Chervo M.F., Dupont A., Chiauzzi V.A., Bruni S., et al. Halting ErbB-2 isoforms retrograde transport to the nucleus as a new theragnostic approach for triple-negative breast cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2022;13(5):447. doi: 10.1038/s41419-022-04855-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen Q.Q., Chen X.Y., Jiang Y.Y., Liu J. Identification of novel nuclear localization signal within the ErbB-2 protein. Cell Res. 2005;15(7):504–510. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7290320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Al-Eidan A., Wang Y., Skipp P., Ewing RM. The USP7 protein interaction network and its roles in tumorigenesis. Genes Dis. 2022;9(1):41–50. doi: 10.1016/j.gendis.2020.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pei Y., Fu J., Shi Y., Zhang M., Luo G., Luo X., et al. Discovery of a potent and selective degrader for USP7. Angew. Chem. (Int. Engl.) 2022;61(33) doi: 10.1002/anie.202204395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nininahazwe L., Liu B., He C., Zhang H., Chen ZS. The emerging nature of ubiquitin-specific protease 7 (USP7): a new target in cancer therapy. Drug Discov. Today. 2021;26(2):490–502. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2020.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gao L., Zhu D., Wang Q., Bao Z., Yin S., Qiang H., et al. Corrigendum: proteome analysis of USP7 substrates revealed its role in melanoma through PI3K/Akt/FOXO and AMPK pathways. Front. Oncol. 2021;11 doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.736438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.