Graphical abstract

Keywords: Depression, Vitamin D, 25-hydroxyvitamin D, Diabetes, Prediabetes, UK Biobank

Abstract

Objective

Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D] is known to be associated with depression. However, the evidence concerning the association between vitamin D status and depressive episodes in population with prediabetes and diabetes remains limited. This study seeks to investigate the potential relationship between vitamin D levels and depression in this population.

Methods

This cohort study comprised 55,252 individuals with prediabetes and 17,369 patients with diabetes, who exhibited no signs of depression at baseline. Baseline 25(OH)D concentrations were assessed. Cox proportional hazard models were employed to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% CIs for depression, with adjustments made for potential confounding variables.

Results

Over a mean follow-up period of 11.7 years, a total of 2,409 depression events were documented in participants with diabetes; and 6,078 depression events were recorded in the prediabetic participants, during a mean follow-up of 12.3 years. Vitamin D sufficiency (≥75 nmol/L) was observed in only 12.5% of individuals with prediabetes and 11.3% of those with diabetes. After multivariate adjustment, an inverse and dose-dependent relationship was identified between serum 25(OH)D concentrations and the risk of depression in prediabetic and diabetic participants (P trend <0.05). Compared with the lowest 25(OH)D level (<25 nmol/L), the highest level (≥75 nmol/L) exhibited a 17% reduction in the risk of depressive events (HR 0.83; 95% CI 0.75−0.93) among individuals with prediabetes and a 25% reduction (HR 0.75; 95% CI 0.61−0.90) among those with diabetes。

Conclusion

The findings of this study highlight the critical importance of prioritizing serum 25(OH)D levels in the management of depression in patients with diabetes and prediabetes.

1. Introduction

Diabetes is rapidly emerging as a significant global health crisis, presenting substantial public health challenge. According to the most recent data, the estimated global prevalence of diabetes was 537 million adults (aged 20–79 years), with prediabetes affecting approximately 464 million individuals as of 2021.The global prevalence of diabetes will rise to 784 million, while prediabetes is expected to increase to 638 million by 2045 [1,2]. Consequently, it is imperative to enhance efforts in the prevention and management of prediabetes and diabetes.

Impaired glucose metabolism contributes to a multitude of disease burdens [3,4]. While global epidemiological data indicate a reduction in overall mortality and cardiovascular disease (CVD) mortality among individuals with diabetes, emerging trends suggest that mortality from non-vascular causes, such as depression, may become increasingly significant in the future [5]. Studies have demonstrated a notable rise in the risk of depression among individuals with prediabetes and diabetes, accompanied by an escalating burden [3]. Therefore, it is imperative to prioritize depression prevention strategies in these patients.

Recent studies have also underscored the importance of maintaining higher serum 25(OH)D levels in individuals with prediabetes and diabetes, as these levels are associated with a reduced risk of cardiovascular disease [6,7], cancer and mortality [[8], [9], [10]]. This correlation is attributed to the frequent deficiency of 25(OH)D observed in such patient [11,12]. However, current research examining the impact of vitamin D levels on depression in patients with abnormal blood glucose is predominantly focused on those with diabetes, and the evidence for patients with prediabetes is limited. Additionally, there are several notable limitations in previous studies, including inconsistent definitions of vitamin D levels, small sample sizes, low quality of study designs, and inadequate adjustments for confounding factors. To address these knowledge gaps, we investigated the association between serum 25(OH)D concentrations and the risk of depression in 17,369 patients with diabetes and 55,252 patients with prediabetes, utilizing data from the UK Biobank. This research aims to enhance awareness regarding the prevention and treatment of depression.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study population

The UK Biobank is a large, population-based, prospective cohort study that recruited more than 500,000 participants aged between 40 and 69 years from 2006 to 2010 at 22 assessment centers in England, Scotland, and Wales. Socio-demographic, lifestyle factors, dietary and medical information was collected through touch screen questionnaires and verbal interviews, and various physical measurements were taken. Blood, urine and saliva samples were also collected for biomarker analysis [13].

In this study, we excluded 54,137 participants who lacked complete data on serum 25(OH)D concentrations at baseline, 1,860 participants with incomplete data on blood glucose or glycated hemoglobin, and 3,610 participants who were potentially excluded due to disease states that could affect study outcomes, including those with systemic inflammatory response syndrome, pregnancy, or various organ failures (such as respiratory failure, heart failure, renal failure, and liver failure). Additionally, 444,443 participants who did not meet the diagnostic criteria for diabetes and prediabetes according to the American Diabetes Association (ADA) 2021 Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes were excluded. Since the outcome event was depression, we further excluded 8,932 participants who had depression at baseline. Ultimately, 72,621 participants were included in our analysis, consisting of 55,252 individuals with prediabetes and 17,369 individuals with diabetes.The flowchart of this study is detailed in Supplementary Fig. S1.

UK BioBank has received Research Tissue Bank (RTB) approval from the North West Multicenter Research Ethics Committee (MREC). All participants signed written informed consent. The study protocol is available online (http://www.ukbiobank.ac.uk/).

2.2. Measurement of serum 25(OH)D concentration

Blood samples were collected from all participants at baseline for biomarker measurement. Serum 25(OH)D concentration was determined using a chemiluminescent immunoassay direct competition method (DiaSorin Liaison XL). The coefficient of variation for serum 25(OH)D determined by this assay ranged from 5.04% to 6.14%, with an external quality assurance result of 100%; the analytical range was 10–375 nmol/L. Information on all blood measurements can be found on the UK Biobank website (https://biobank.ndph.ox.ac.uk/showcase/showcase/docs/serum_biochemistry.pdf).

2.3. Outcome determined

The principal outcome of this study was the incidence of depression, identified through algorithms supplied by the UK Biobank database. Hospitalization records were acquired by tegrating health event statistics, patient case databases, Welsh Patient Hospitalization Record data, and Scottish Disease Records. Health outcome data were available up to November 30, 2020 at the time of analysis. The occurrence of depression events was defined using ICD-10 codes (F32、F33). In addition, we incorporated medical history information for depression-specific prescriptions including fluoxetine, sertraline, amitriptyline, paroxetine, and citalopram to identify existing cases of depression at baseline. For participants who experienced depressive events, the follow-up duration was defined as the period from the time of enrollment to the time of the first diagnosis of depression; otherwise, the follow-up duration extended until the end of the study or the time of loss to follow-up (or death).

2.4. Definitions of diabetes and prediabetes

According to the 2021 American Diabetes Association (ADA) Standards of Care for Diabetes Mellitus [14], prediabetes was defined as a baseline HbA1c level between 5.7% and 6.4% (39–47 mmol/mol), while diabetes was defined based on any of the following criteria: (1) HbA1c ≥ 6.5% (48 mmol/mol) or random plasma glucose ≥11.1 mmol/L; (2) identification of incident diabetes events using hospitalization and diagnostic data, indicated by ICD-10 codes E10.0–E14.9.

2.5. Assessment of covariates

The baseline questionnaire collected data on sociodemographic factors (gender, age, ethnicity, and household income), lifestyle habits (alcohol consumption, sleep, and smoking status), and physical measures (height, weight, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, and body mass index (BMI)). Vitamin D assessment seasons were categorized by the month in which participants underwent evaluation: spring (March, April, or May), summer (June, July, or August), fall (September, October, or November), and winter (December, January, or February). Information regarding medication usage history (antihypertensive medications, lipid regulators, hypoglycemic medications, insulin, and vitamin D supplements) was gathered through participant interviews. Blood tests, such as low-density lipoprotein (LDL), high-density lipoprotein (HDL), cholesterol (TC), triglycerides (TG), glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c), and blood glucose (Glu) were also performed on participants at baseline.

2.6. Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were pressented as mean ± standard deviation or median (interquartile range), and categorical variables were expressed as numbers (percentages). To address missing data on covariates, we employed 20 iterations of chained equations multiple interpolation multiple interpolation (chained equations) to fill in the data.

Based on the Endocrine Society's clinical practice guidelines, participants were categorized into four groups based on baseline serum 25(OH)D concentrations: severely deficient (<25.0 nmol/L), moderately deficient (25.0 to 50.0 nmol/L), deficient (50.0 to 75.0 nmol/L), and adequate (≥75.0 nmol/L). We then compared the distribution of baseline characteristics across these serum 25(OH)D concentrations.

At baseline, distinct cross-sectional studies were conducted within prediabetic and diabetic cohorts. To further investigate the relationship between serum 25(OH)D concentrations and the onset of depression, we initially performed a longitudinal analysis of hazard ratios (HR) and their corresponding 95% confidence intervals utilizing Cox proportional hazards models. Subsequently, multivariate models were evaluated: Model 1 was unadjusted, Model 2 was adjusted for age and gender at the time of recruitment, and Model 3 was further adjusted for educational level (university or equivalent, A/AS level or equivalent or O level/general certificate of secondary education [GCSE] or equivalent or national vocational qualification or National Diploma in Higher Education or National Certificate in Higher Education or equivalent or other professional qualification, none of the above), season of vitamin D blood sample collection (December-February, March- May, June-August, September-November), and summer sun exposure time in one step from model 2. In Model 4, we further adjusted for household income (<£18,000, £18,000–30,999, £31,000−51,999, >£52,000), ethnicity (White, Asian, Black, Chinese, Mixed), sleep duration (≤6 hours/day, 7−8 hours/day, and ≥9 hours/day) as well as intake of vitamin D supplements, blood pressure lowering medications and lipid-modulating drugs.

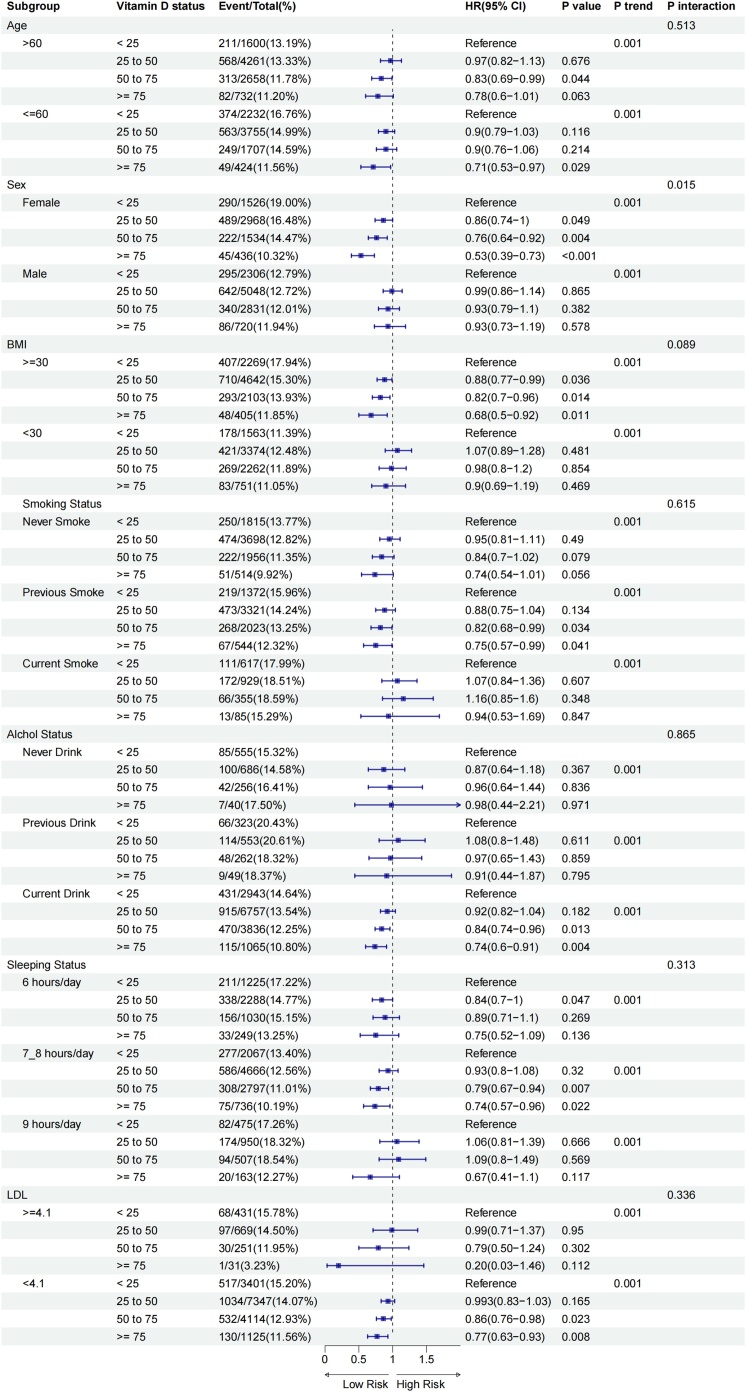

Secondly, we stratified the analysis based on sex (male, female), age (≤60, >60 years), BMI (≤30, >30 kg/m2), smoking status (never smoker, previous smoker, current smoker), alcohol consumption status (never drank, previous drinker, current drinker), sleep duration (≤6 hours/day, 7−8 hours/day, ≥9 hours/day), and LDL levels (≤4.1 mmol/L, >4.1mmol/L). Additionally, stratification was performed according to serum 25(OH)D concentration levels within each subgroup. To investigate whether the association between serum 25(OH)D concentration and depression varied according to these stratification variables, we employed an interaction model to evaluate the potential modifying effect of these factors on the relationship between serum vitamin D status and depression risk.

Additionally, to ensure the reliability of the study findings, we conducted several sensitivity analyses. First, to minimize the possibility of reverse causality in the observed associations, we excluded participants with less than 2 years of follow-up. Second, since certain psychiatric conditions may influence vitamin D metabolism or the risk of depression, we further excluded individuals with severe mental illnesses at baseline, such as anxiety, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia. Third, considering that antidepressant medications such as fluoxetine, sertraline, amitriptyline, paroxetine, and citalopram may lack specificity for depression and could lead to overdiagnosis, we excluded individuals diagnosed with depression based solely on medication use. Fourth, to enhance the identification of more cases of depression, we incorporated PHQ-9 questionnaire [15] data from the UK Biobank (field IDs: 20510, 20514, 20519, 20511, 20513, 20508, 20517) to assist in the diagnosis of depression. Fifth, since blood glucose levels and oral hypoglycemic agents in diabetes participants may affect vitamin D metabolism or absorption, thereby interfering with the association between 25(OH)D and depression, we additionally adjusted for HbA1c and hypoglycemic medications in Model 4 for diabetes participants.

In this study, a two-sided p < 0.05 was considered a sign of statistical significance, and p < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance of the interaction. All analyses were performed using R 4.3.3.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the participants

Among the 55,252 participants with prediabetes (N = 28,542, 51.7% female), the mean (SD) age was 59.63 (7.05) years; among the 17,369 participants with diabetes, the mean (SD) age was 59.55 (7.18) years, with 6,464 (37.2%) being female. During a mean follow-up period of 11.7 years, 2,409 depression events were recorded among participants with diabetes, while 6,078 depressive events were recorded among participants with prediabetes over a mean follow-up period of 12.3 years. The baseline distribution characteristics of the study population according to serum 25(OH)D level categories are detailed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics between diabetes and prediabetes.

| Serum 25(OH)D concentration(nmol/L) |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diabetes | Prediabetes | |||||||||||

| Variable | Total | <25 | 25to50 | 50to75 | ≥75 | p | Total | <25 | 25to50 | 50to75 | ≥75 | p |

| N of patients | 17369 | 3832 | 8016 | 4365 | 1156 | 55252 | 8713 | 24230 | 17076 | 5233 | ||

| Age | 59.55 (7.18) | 57.69 (7.54) | 59.53 (7.17) | 60.84(6.67) | 61.01(6.49) | <0.001 | 59.63 (7.05) | 57.33 (7.72) | 59.43 (7.06) | 60.63 (6.55) | 61.09 (6.33) | <0.001 |

| Sex, % | ||||||||||||

| Male | 10905 (62.8) | 2306 (60.2) | 5048 (63.0) | 2831 (64.9) | 720 (62.3) | <0.001 | 26710 (48.3) | 4331 (49.7) | 11656 (48.1) | 8146 (47.7) | 2577 (49.2) | <0.001 |

| Female | 6464 (37.2) | 1526 (39.8) | 2968 (37.0) | 1534 (35.1) | 436 (37.7) | 28542 (51.7) | 4382 (50.3) | 12574 (51.9) | 8930 (52.3) | 2656 (50.8) | ||

| Education*,% | ||||||||||||

| 1 | 4109 (23.7) | 987 (25.8) | 1951 (24.3) | 921 (21.1) | 250 (21.6) | <0.001 | 14681 (26.6) | 2501 (28.7) | 6656 (27.5) | 4267 (25.0) | 1257 (24.0) | <0.001 |

| 2 | 5822 (33.5) | 1278 (33.4) | 2674 (33.4) | 1462 (33.5) | 408 (35.3) | 19353 (35.0) | 2870 (32.9) | 8363 (34.5) | 6188 (36.2) | 1932 (36.9) | ||

| 3 | 2501 (14.4) | 525 (13.7) | 1165 (14.5) | 637 (14.6) | 174 (15.1) | 7517 (13.6) | 1150 (13.2) | 3283 (13.5) | 2363 (13.8) | 721 (13.8) | ||

| 4 | 4937 (28.4) | 1042 (26.2) | 2226 (27.8) | 1345 (30.8) | 324 (28.1) | 13696 (24.8) | 2192 (25.2) | 5928 (24.4) | 4258 (24.9) | 1323 (25.3) | ||

| Ethnicity, % | ||||||||||||

| White | 15060 (86.7) | 2838 (74.1) | 6977 (87.0) | 4119 (94.4) | 1126 (97.4) | <0.001 | 49797 (90.1) | 6513 (74.8) | 21781 (89.9) | 16380 (95.9) | 5123 (97.9) | <0.001 |

| Asian | 1068 (6.1) | 601 (15.7) | 383 (4.8) | 74 (1.7) | 10 (0.9) | 1877 (3.4) | 1034 (11.9) | 684 (2.8) | 137 (0.8) | 22 (0.4) | ||

| Black | 650 (3.7) | 192 (5.0) | 361 (4.5) | 88 (2.0) | 9 (0.8) | 1776 (3.2) | 620 (7.1) | 879 (3.6) | 240 (1.4) | 37 (0.7) | ||

| Chinese | 62 (0.4) | 18 (0.5) | 29 (0.4) | 14 (0.3) | 1 (0.1) | 333 (0.6) | 87 (1.0) | 196 (0.8) | 47 (0.3) | 3 (0.1) | ||

| Mixed | 113 (0.7) | 33 (0.9) | 58 (0.7) | 18 (0.4) | 4 (0.3) | 406 (0.7) | 114 (1.3) | 178 (0.7) | 98 (0.6) | 16 (0.3) | ||

| Other | 416 (2.4) | 150 (3.9) | 208 (2.6) | 52 (1.2) | 6 (0.5) | 1063 (1.9) | 345 (4.0) | 512 (2.1) | 174 (1.0) | 32 (0.6) | ||

| Household income £, % | ||||||||||||

| <18,000 | 5150 (29.7) | 1299 (33.9) | 2329 (29.1) | 1225 (28.1) | 297 (25.7) | <0.001 | 13614 (24.6) | 2592 (29.7) | 5999 (24.8) | 3846 (22.5) | 1177 (22.5) | <0.001 |

| 18,000−30,999 | 4145 (23.9) | 830 (21.7) | 1881 (23.5) | 1126 (25.8) | 308 (26.6) | 13249 (24.0) | 1872 (21.5) | 5773 (23.8) | 4308 (25.2) | 1296 (24.8) | ||

| 31,000−51,999 | 2952 (17.0) | 620 (16.2) | 1364 (17.0) | 751 (17.2) | 217 (18.8) | 10774 (19.5) | 1571 (18.0) | 4826 (19.9) | 3346 (19.6) | 1031 (19.7) | ||

| >52,000 | 2151 (12.4) | 412 (10.8) | 1060 (13.2) | 532 (12.2) | 147 (12.7) | 8217 (14.9) | 1191 (13.7) | 3592 (14.8) | 2618 (15.3) | 816 (15.6) | ||

| Other | 2971 (17.1) | 671 (17.5) | 1382 (17.2) | 731 (16.7) | 187 (16.2) | 9398 (17.0) | 1487 (17.1) | 4040 (16.7) | 2958 (17.3) | 913 (17.4) | ||

| BMI, kg/m2 | 31.37 (5.84) | 32.35 (6.66) | 31.78 (5.70) | 30.43 (5.24) | 28.85 (4.82) | 28.96 (5.24) | 30.21 (5.96) | 29.43 (5.34) | 28.24 (4.67) | 27.05 (4.40) | <0.001 | |

| Smoking status, % | ||||||||||||

| Never | 7983 (46.0) | 1815 (47.4) | 3698 (46.1) | 1956 (44.8) | 514 (44.5) | <0.001 | 26947 (48.8) | 4159 (47.7) | 11920 (49.2) | 8430 (49.4) | 2438 (46.6) | <0.001 |

| Previous | 7260 (41.8) | 1372 (35.8) | 3321 (41.4) | 2023 (46.3) | 544 (47.1) | 19957 (36.1) | 2599 (29.8) | 8615 (35.6) | 6564 (38.4) | 2179 (41.6) | ||

| Current | 1986 (11.4) | 617 (16.1) | 929 (11.6) | 355 (8.1) | 85 (7.4) | 8066 (14.6) | 1889 (21.7) | 3584 (14.8) | 1998 (11.7) | 595 (11.4) | ||

| Missing | 140 (0.8) | 28 (0.7) | 68 (0.8) | 31 (0.7) | 13 (1.1) | 282 (0.5) | 66 (0.8) | 111 (0.5) | 84 (0.5) | 21 (0.4) | ||

| Drinking status, % | ||||||||||||

| Never | 1537 (8.8) | 555 (14.5) | 686 (8.6) | 256 (5.9) | 40 (3.5) | <0.001 | 3463 (6.3) | 1063 (12.2) | 1481 (6.1) | 744 (4.4) | 175 (3.3) | <0.001 |

| Previous | 1187 (6.8) | 323 (8.4) | 553 (6.9) | 262 (6.0) | 49 (4.2) | 2361 (4.3) | 493 (5.7) | 1074 (4.4) | 619 (3.6) | 175 (3.3) | ||

| Current | 14601 (84.1) | 2943 (76.8) | 6757 (84.3) | 3836 (87.9) | 1065 (92.1) | 49319 (89.3) | 7117 (81.7) | 21632 (89.3) | 15694 (91.9) | 4876 (93.2) | ||

| Missing | 44 (0.3) | 11 (0.3) | 20 (0.2) | 11 (0.3) | 2 (0.2) | 109 (0.2) | 40 (0.5) | 43 (0.2) | 19 (0.1) | 7 (0.1) | ||

| Sleeping duration, hours/day, % | ||||||||||||

| ≤6 | 4792 (27.6) | 1225 (32.0) | 2288 (28.5) | 1030 (23.6) | 249 (21.5) | <0.001 | 14868 ( 26.9) | 2764 (31.7) | 6676 ( 27.6) | 4225 ( 24.7) | 1203 ( 23.0) | <0.001 |

| 7−8 | 10266 (59.1) | 2067 (53.9) | 4666 (58.2) | 2797 (64.1) | 736 (63.7) | 35296 ( 63.9) | 5087 ( 58.4) | 15393 ( 63.5) | 11273 ( 66.0) | 3543 ( 67.7) | ||

| ≥9 | 2095 (12.1) | 475 (12.4) | 950 (11.9) | 507 (11.6) | 163 (14.1) | 4601 (8.3) | 720 ( 8.3) | 1942 ( 8.0) | 1476 ( 8.6) | 463 ( 8.8) | ||

| Missing | 216 (1.2) | 65 (1.7) | 112 (1.4) | 31 (0.7) | 8 (0.7) | 487 (0.9) | 142 (1.6) | 219 ( 0.9) | 102 ( 0.6) | 24 (0.5) | ||

| Season of vitamin assessment, % | ||||||||||||

| Spring | 5206 (30.0) | 1121 (29.3) | 2392 (29.8) | 1372 (31.4) | 321 (27.8) | 0.246 | 16529 ( 29.9) | 2579 ( 29.6) | 7331 ( 30.3) | 5055 ( 29.6) | 1564 ( 29.9) | 0.089 |

| Summer | 5111 (29.4) | 1151 (30.0) | 2360 (29.4) | 1237 (28.3) | 363 (31.4) | 16292 ( 29.5) | 2491 ( 28.6) | 7166 ( 29.6) | 5103 ( 29.9) | 1532 ( 29.3) | ||

| Autumn | 3141 (18.1) | 677 (17.7) | 1479 (18.5) | 779 (17.8) | 206 (17.8) | 9838 ( 17.8) | 1614 ( 18.5) | 4186 ( 17.3) | 3097 ( 18.1) | 941 ( 18.0) | ||

| Winter | 3911 (22.5) | 883 (23.0) | 1785 (22.3) | 977 (22.4) | 266 (23.0) | 12593 ( 22.8) | 2029 ( 23.3) | 5547 ( 22.9) | 3821 ( 22.4) | 1196 ( 22.9) | ||

| Vitamin supplement intake, % | 587 (3.4) | 65 (1.7) | 245 (3.1) | 212 (4.9) | 65 (5.6) | <0.001 | 2279 (4.1) | 158 (1.8) | 760 (3.1) | 965 (5.7) | 396 (7.6) | <0.001 |

| Antihypertensive drug use, % | 6440 (37.1) | 1388 (36.2) | 3016 (37.6) | 1595 (36.5) | 441 (38.1) | 0.342 | 9796 (17.7) | 1585 (18.2) | 4310 (17.8) | 2961 (17.3) | 940 (18.0) | 0.348 |

| Lipid-regulating drug use, % | 11240 (64.7) | 2294 (59.9) | 5173 (64.5) | 2913 (66.7) | 860 (74.4) | <0.001 | 15315(27.7) | 2297 (26.4) | 6500 (26.8) | 4780 (28.0) | 1738 (33.2) | <0.001 |

| History of Parathyroid disease, % | 143 (0.8) | 32 (0.8) | 72 (0.9) | 30 (0.7) | 9 (0.8) | 0.665 | 294 (0.5) | 53 (0.6) | 148 (0.6) | 74 (0.4) | 19 (0.4) | 0.021 |

| History of hypertensive disease, % | 11794 (67.9) | 2645 (69.0) | 5500 (68.6) | 2896 (66.3) | 753 (65.1) | 0.005 | 32112 (58.1) | 5153 (59.1) | 14290 (59.0) | 9762 (57.2) | 2907 (55.6) | <0.001 |

| TC, mmol/l | 4.62 (1.07) | 4.82 (1.13) | 4.65 (1.06) | 4.51 (1.02) | 4.22 (0.91) | <0.001 | 5.55 (1.09) | 5.60 (1.07) | 5.59 (1.08) | 5.56 (1.08) | 5.28 (1.09) | <0.001 |

| TG, mmol/l | 2.20 (1.30) | 2.49 (1.52) | 2.26 (1.30) | 1.99 (1.07) | 1.60 (0.84) | <0.001 | 1.94 (1.05) | 2.16 (1.23) | 2.02 (1.09) | 1.84 (0.92) | 1.55 (0.74) | <0.001 |

| HDL-C, mmol/l | 1.20 (0.33) | 1.17 (0.33) | 1.18 (0.32) | 1.23 (0.34) | 1.27 (0.37) | <0.001 | 1.36 (0.35) | 1.30 (0.34) | 1.35 (0.35) | 1.40 (0.36) | 1.42 (0.37) | <0.001 |

| LDL-C, mmol/l | 2.80 (0.80) | 2.94 (0.85) | 2.82 (0.80) | 2.71 (0.77) | 2.47 (0.67) | <0.001 | 3.48 (0.83) | 3.54 (0.82) | 3.52 (0.83) | 3.47 (0.82) | 3.26 (0.83) | <0.001 |

| HbA1c, % | 7.35 (1.29) | 7.56 (1.44) | 7.37 (1.29) | 7.21 (1.19) | 7.10 (1.01) | <0.001 | 5.91 (0.19) | 5.93 (0.20) | 5.91 (0.19) | 5.89 (0.18) | 5.88 (0.17) | <0.001 |

| Glucose, mmol/l | 8.21 (3.70) | 8.62 (4.02) | 8.24 (3.70) | 7.95 (3.47) | 7.65 (3.27) | <0.001 | 5.27 (0.87) | 5.28 (0.91) | 5.28 (0.89) | 5.26 (0.85) | 5.22 (0.82) | <0.001 |

| Follow_time | 11.7(3.8) | 11.3 (4.0) | 11.7 (3.8) | 11.9 (3.7) | 11.8 (3.7) | <0.001 | 12.3 (3.4) | 12.0 (3.6) | 12.3 (3.4) | 12.4 (3.3) | 12.3 (3.4) | <0.001 |

Education*: 1. College or university degree; 2. A/AS levels or equivalent or Olevels/GCSE or CSE or equivalent; 3. NVQ or HND or HNC or equivalent or other professional qualifications; 4. None of the above.

Overall, the mean (SD) serum 25(OH)D concentrations were 46.50 (20.66) nmol/L and 42.03 (20.04) nmol/L in participants with prediabetes and diabetes, respectively. Among participants with prediabetes and diabetes, 15.8% and 22.1% had severe vitamin D deficiency (<20 nmol/L), while 43.9% and 46.2% had moderate vitamin D deficiency (25 to <50 nmol/L). A total of 17,076 participants with prediabetes and 4,365 participants with diabetes had serum 25(OH)D levels ≥50 nmol/L, with only 9.5% (5,233) of prediabetes participants and 6.7% (1,156) of diabetes participants having sufficient vitamin D levels (≥75 nmol/L).

Participants with higher serum 25(OH)D levels in both prediabetes and diabetes groups were more likely to be older (>60 years), White, highly educated, never or previous smokers, and alcohol consumers. They were also more likely to sleep 7−8 hours/day, have a lower body mass index (BMI), and a lower likelihood of hypertension and thyroid disorders. Additionally, they exhibited lower circulating levels of total cholesterol (TC), triglycerides (TG), and low-density lipoprotein (LDL), along with higher levels of high-density lipoprotein (HDL). Compared to participants with lower serum 25(OH)D levels, those with higher levels in the prediabetes group were more likely to be female (51.7%), while in the diabetes group, they were more likely to be male (62.8%).

3.2. Serum 25(OH)D concentrations and risk of depression in the prediabetic population

Over a mean follow-up period of 12.3 years, a total of 6,078 incidents of depression were documented among 55,252 participants with prediabetes. Table 2 illustrates the correlation between serum 25(OH)D concentration categories and the associated outcomes. In Model 1, which was unadjusted, compared to the group with the lowest serum 25(OH)D concentration, the risk of depression was reduced by 13% (HR 0.87; 95% CI 0.81–0.94) in the 25(OH)D-deficient group and by 21% (HR 0.79; 95% CI 0.71–0.88) in the 25(OH)D-sufficient group. In Model 2, after adjusting for age and sex, serum 25(OH)D levels continued to exhibit a dose-response inverse association with depression risk, with a 7% reduction in depression risk for every 1 SD increase in serum 25(OH)D concentration. In Model 3, after further adjustments for ethnicity, education level, household income, summer outdoor time, and vitamin D supplementation, these associations remained statistically significant (all P-values < 0.05). The moderately deficient, deficient, insufficient, and sufficient groups showed reductions in depression risk by 11%, 16%, and 18%, respectively. In Model 4, which additionally adjusted for sleep duration, antihypertensive medication, and lipid-lowering medication, a statistically significant association was observed between the sufficient serum 25(OH)D concentration group (≥75 nmol/L) and depression risk (p = 0.001), with an HR of 0.83 (95% CI 0.75–0.93).

Table 2.

Hazard ratios (95% confidence intervals) for Depression according to serum 25-(OH)D concentrations among patients with prediabetes and diabetes.

| Serum25-(OH)D concentration, nmol/L |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <25 | 25 to 50 | P | 50 to 75 | P | >75 | P | P Trend | Per SD | |

| Prediabetes(n = 55252) | |||||||||

| n/N of events | 1087/8713 | 2687/24230 | 1777/17076 | 527/5233 | 6078/55252 | ||||

| Model 1 | 1 (Reference) | 0.87 (0.81−0.94) | <0.001 | 0.81 (0.75−0.88) | <0.001 | 0.79 (0.71−0.88) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.92 (0.90−0.95) |

| Model 2 | 1 (Reference) | 0.87 (0.81−0.94) | <0.001 | 0.82 (0.76−0.88) | <0.001 | 0.80 (0.72−0.89) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.93 (0.90−0.95) |

| Model 3 | 1 (Reference) | 0.89 (0.83−0.96) | 0.002 | 0.84 (0.77−0.90) | <0.001 | 0.82 (0.73−0.91) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.93 (0.91−0.96) |

| Model 4 | 1 (Reference) | 0.90 (0.84−0.97) | 0.006 | 0.85 (0.79−0.92) | <0.001 | 0.83 (0.75−0.93) | 0.001 | <0.001 | 0.94 (0.91−0.96) |

| Diabetes(n = 17369) | |||||||||

| n/N of events | 585/3832 | 1131/8016 | 562/4365 | 131/1156 | 2409/17369 | ||||

| Model 1 | 1 (Reference) | 0.90 (0.81−0.99) | 0.037 | 0.81 (0.72−0.91) | <0.001 | 0.72 (0.59−0.87) | 0.001 | <0.001 | 0.91 (0.88−0.95) |

| Model 2 | 1 (Reference) | 0.92 (0.83−1.02) | 0.107 | 0.84 (0.75−0.95) | 0.005 | 0.74 (0.61−0.90) | 0.002 | <0.001 | 0.93 (0.89−0.96) |

| Model 3 | 1 (Reference) | 0.92 (0.83−1.02) | 0.132 | 0.83 (0.74−0.94) | 0.003 | 0.74 (0.61−0.90) | 0.003 | <0.001 | 0.92 (0.88−0.96) |

| Model 4 | 1 (Reference) | 0.93 (0.84−1.03) | 0.143 | 0.85 (0.76−0.96) | 0.01 | 0.75 (0.61−0.90) | 0.003 | <0.001 | 0.93 (0.89−0.97) |

Model 1: Without adjustment.

Model 2: Adjusted for age and sex.

Model 3: Adjusted for Model 2+ Ethnicity (White, Black, Asian, Chinese, Mixed, or Other), education (college or university degree, A/AS levels or equivalent or O levels/General Certificate of Secondary Education or Certificate of Secondary Education or equivalent, National Vocational Qualification or Higher National Diploma or Higher National Certificate or equivalent or other professional qualifications, none of the above),household income (£18,000, £18,000–30,999, £31,000−51,999, > £52,000), vitamin supplementation(include medicine and food), and sun exposure time(hours/day).

Model 4: Adjusted for Model 3 + Sleep duration (6 hours/day, 7–8 hours/day, 9 hours/day), season of vitamin assessment, antihypertensive drug use (yes or no), lipid-lowering medication (yes or no), and prevalent parathyroid disease (yes or no).

3.3. Serum 25(OH)D concentration and risk of depression in diabetic population

Over a mean follow-up duration of 11.7 years, 2,409 incidents of depression were documented among 17,369 individuals with diabetes. As illustrated in Table 2, serum 25(OH)D concentration was inversely correlated with the risk of depression across all models in a dose-dependent manner (P trend <0.05). When compared to the group with the lowest serum 25(OH)D concentration, the risk of depression in those with moderate serum 25(OH)D deficiency (25–50 nmol/L) was not significantly different in any of the four models (p > 0.05). In model 1, compared with the group with the lowest serum 25(OH)D concentration, the risk of depression in the highest category of 25(OH)D levels (≥75 nmol/L) was reduced by 28% (HR 0.72; 95% CI 0.59−0.87). After adjusting for multivariate factors (model4), serum 25(OH)D concentrations in the insufficient as well as sufficient groups reduced the risk of depression by 15% (HR 0.85;95% CI 0.76−0.96) and 25%(HR 0.75;95% CI 0.61−0.90), respectively.

3.4. Stratified analysis

Stratified analyses were conducted based on age (>60 years, ≤60 years), sex (male, female), BMI (≤30 kg/m², >30 kg/m²), LDL levels (≥4.1 mmol/L, <4.1 mmol/L), smoking status (current smoker, non-smoker), and alcohol consumption status (current drinker, non-drinker). Notably, in the prediabetes population, Fig. 1 reveals that the association between serum 25(OH)D concentration and depression risk showed statistically significant differences across sex, BMI, smoking status, alcohol consumption status, and sleeping status ( p <0.05). This suggests that the relationship between serum 25(OH)D concentration and depression risk in prediabetes individuals may be influenced by these factors. Specifically, among prediabetes participants, higher vitamin D levels were significantly associated with a reduced risk of depression, particularly in younger and middle-aged individuals (age ≤60 years), those with obesity (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m²), and female participants. Additionally, the beneficial effect of higher vitamin D levels on reducing depression risk was more pronounced in previous smokers, with a maximum reduction in depression risk of 25% (HR 0.75; 95% CI 0.63–0.89), while no significant trend was observed in never-smokers and current smokers. Among current drinkers and participants with sufficient sleep (7-8 hours/day), higher vitamin D levels were associated with a reduced risk of depression. Participants with the highest serum 25(OH)D levels (≥75 nmol/L) had a 21% (HR 0.79; 95% CI 0.70-0.88) and 20% (HR 0.80; 95% CI 0.69-0.92) lower risk of depressive events, respectively, compared to those in the lowest category (<25 nmol/L). Similar patterns were observed in the diabetes population (Fig. 2, Supplemental Table S1).

Fig. 1.

Subgroup analysis of serum 25(OH)D concentration and depression risk based on age, sex, body mass index (BMI), low-density lipoprotein (LDL), smoking status, sleeping status and alchol status in prediabetes.*

*Adjusted for age, sex (male, female), education (college or university degree, A/AS levels or equivalent or O levels/GCSEs, NVQ or HND or HNC or equivalent or other professional qualifications, none of the above), house income(£18,000, £18,000–30,999, £31,000−51,999, >£52,000), ethnicity (White, Mixed, Asian, Black, China and other), blood collection season (Dec-Feb, Mar-May, Jun-Aug, Sep-Nov), sun-exposure time in summer (continuous, hours/day), sleep duration (≤6 hours/day, 7−8 hours/day, ≥9 hours/day), vitamin supplementation(yes or no), medication for hypertension and cholesterol (yes, no), and antidiabetic drug or insulin treatment (yes or no). The strata variable was not included in the model when stratifying by itself.

Fig. 2.

Subgroup analysis of serum 25(OH)D concentration and depression risk based on age, sex, body mass index (BMI), low-density lipoprotein (LDL), smoking status, sleeping status and alchol status in diabetes.*

*Adjusted for age, sex (male, female), education (college or university degree, A/AS levels or equivalent or O levels/GCSEs, NVQ or HND or HNC or equivalent or other professional qualifications, none of the above), house income(£18,000, £18,000–30,999, £31,000−51,999, > £52,000), ethnicity (White, Mixed, Asian, Black, China and other), blood collection season (Dec-Feb, Mar-May, Jun-Aug, Sep-Nov), sun-exposure time in summer (continuous, hours/day), sleep duration (≤6 hours/day, 7−8 hours/day, ≥9 hours/day), vitamin supplementation(yes or no), medication for hypertension and cholesterol (yes, no), and antidiabetic drug or insulin treatment (yes or no). The strata variable was not included in the model when stratifying by itself.

Although the association between serum 25(OH)D concentration and depression risk did not reach statistical significance in some subgroups, this may be due to insufficient sample size or reduced statistical power. However, the overall results suggest that maintaining higher vitamin D levels may have potential benefits in reducing depression risk in specific subgroups of prediabetes and diabetes populations, particularly among females, individuals aged ≤60 years, those with BMI ≥ 30 kg/m², sufficient sleep (7-8 hours/day), previous-smokers, and current drinkers. These findings underscore the importance of considering individual characteristics when evaluating the relationship between vitamin D status and mental health outcomes. Future research could further explore differences among these subgroups to better understand the potential role of vitamin D in depression prevention.

3.5. Sensitivity analyses

To more robustly elucidate the association between serum 25(OH)D concentrations and depression risk in individuals with prediabetes and diabetes, we conducted several sensitivity analyses. Consistent with prior findings, across all models, higher categories of serum 25(OH)D levels were associated with a reduced risk of depression events in both prediabetes and diabetes participants compared to the lowest category (<25 nmol/L), demonstrating a dose-dependent relationship (p < 0.05) (Supplementary Table S2).

4. Discussion

This large-scale prospective cohort study reveals the association between serum 25(OH)D concentration and the risk of depression in individuals with diabetes and prediabetes. The study found that higher serum 25(OH)D levels are associated with a reduced risk of depression, and this association is somewhat influenced by different genders and lifestyles, particularly among female participants aged ≤ 60 years, previousnon-smokers, with a BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2, sufficient sleep (7-8 hours/day), and current alcohol consumption.

Numerous meta-analyses and prospective cohort studies have reported on the relationship between serum 25(OH)D concentration and depression [[16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21]]. A cohort study involving 100 healthy individuals and 100 depressed patients found that the depressed population generally had lower levels of vitamin D compared to healthy individuals [22]. A study of 2,786 type 2 diabetes patients from the China Diabetes Registry observed a significant negative correlation between serum 25(OH)D levels and depression in Chinese type 2 diabetes patients [23]. Similarly, a Dutch study of 2,839 elderly individuals found that lower levels of serum 25(OH)D were associated with higher depression symptom scores [24]. The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) investigated the serum 25(OH)D concentration in 8,417 adult depressed patients and found that those with higher serum 25(OH)D levels had lower all-cause mortality and cancer-specific mortality [25]. This is consistent with the findings of this study. The reason may be that patients with abnormal blood glucose often have reduced serum 25(OH)D concentrations [6,[26], [27], [28]]. Animal studies have shown that serum 25(OH)D can stimulate pancreatic β-cells to secrete insulin [29]. Additionally, active vitamin D metabolites may regulate the growth and differentiation of β-cells. Vitamin D deficiency can lead to secondary hyperparathyroidism, and high concentrations of parathyroid hormone (PTH) may result in reduced glucose tolerance [30]. Vitamin D deficiency is associated with increased inflammatory markers, and the relationship between insulin resistance and vitamin D deficiency may be mediated through inflammation [31].

Our study highlights a differential impact of serum 25(OH)D concentration on depression risk among prediabetic and diabetic patients across genders, with a more pronounced effect observed in females. After fully adjusting for potential confounding factors, we observed that female patients with sufficient serum 25(OH)D levels had a HR and 95% CI for depression events of 0.81 (0.7−0.93), while this phenomenon was not significant in male patients. In the diabetic population, this gender difference was even more pronounced (HR 0.53; 95% CI 0.39–0.73). This aligns with previous reports [32,33]. A systematic review summarized the potential causes of gender differences in depression, including hormonal levels, socio-psychological factors, and genetic factors [34]. This may be due to the fact that vitamin D deficiency is more common in women than in men, and vitamin D can regulate the production of the neurotransmitter serotonin (5-HT). A study by Nishizawa showed that the rate of serotonin synthesis in the brains of women is only half that of men [35].Beyond gender, the association between serum 25(OH)D concentration and depression events also varies across different age groups, particularly in diabetic patients. Higher serum 25(OH)D levels were linked to a reduced risk of depression in patients aged 60 years or younger, with this association being particularly significant among those with prediabetes. A meta-analysis showed that the proportion of individuals with serum 25(OH)D levels <30 nmol/L is more pronounced among those aged 19–44 years. It is speculated that this is related to lower vitamin D supplementation among these individuals [36].A study in England on diabetes and its associated chronic diseases revealed that depression and severe mental illness are major burdens among adolescents [3]. A study in the United States indicates that due to the significant fluctuations in hormone levels during puberty, the incidence of mental health events in females is also significantly higher than in males [37].

The mechanisms underlying depression in individuals with vitamin D deficiency warrant further investigation. Current hypotheses suggest several possible explanations for this association. Depression may result from an imbalance between excitatory and inhibitory neurons, potentially induced by elevated glutamate levels. Calcium ions (Ca2+) play a crucial role in this process, and vitamin D is capable of regulating the production of these above neurotransmitters. Furthermore, depression is linked to chronic inflammation, and vitamin D has been shown to reduce the levels of C-reactive protein (CRP), serum lipoprotein A and interleukin-6 (IL-6) [38]. Additionally, vitamin D enhances natural killer (NK) cell activity [39], inhibits macrophage migration and boosts immunity in diabetic patients [40]. Multiple randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and meta-analyses have shown that vitamin D supplementation can reduce depression symptom scores [[41], [42], [43], [44], [45], [46]]. An observational study demonstrated that vitamin D supplementation improved depression scores, particularly in individuals with baseline 25(OH)D levels below 50 nmol/L [47]. Studies have shown that vitamin D supplementation significantly improves mood in obese women with mild to moderate depressive symptoms [48]. The potential beneficial effects of vitamin D supplementation on depression risk may even extend to patients with type 2 diabetes [43,49]. For patients with diabetic peripheral neuropathy or perinatal depression, vitamin D supplementation may alleviate symptoms by modulating inflammatory factors such as IL-1β and TNF-α [50]. As an adjunct to antidepressant medications, vitamin D supplementation may enhance treatment efficacy, although further research is needed to confirm this [46]. Our findings provide a basis for vitamin D supplementation strategies in diabetic and prediabetic populations with depression, offering valuable insights for future treatment and prevention of depression in these groups.

Our study has several notable strengths. Firstly, the UK Biobank represents an extensive population-based baseline prospective cohort study characterized by a substantial sample size and an extended follow-up duration, thereby offering a wealth of case data. Secondly, comprehensive data collection was undertaken, encompassing sociodemographic and lifestyle factors, dietary and medical information, viatouch-screen questionnaires and verbal interviews. Additionally, a variety of physical measurements were conducted, and biological samples, including blood, urine, and saliva, were collected for biomarker analysis. This rigorous data collection methodology enhances reliability of our study by allowing for comprehensive adjustment for potential confounders. Finally, the rigorous and reliable measurement method of serum 25(OH)D concentration in UK Biobank also provided reliable data for the dose-response relationship in this study.

This study is subject to several potential limitations. Firstly, the diagnosis of depression was based solely on ICD-10 codes and medication records, potentially excluding cases identified through psychological assessment scales and ICD-9 criteria. Secondly, while the UK Biobank provided extensive phenotypic and genotypic data, this research did not sufficiently account for the influence of genetic risk factors for depression among participants with diabetes and prediabetes, which may have introduced bias. However, previous studies have shown that type 2 diabetes increases the risk of depression by 40–60 % [51]. In addition, due to the lack of serum 25(OH)D concentration in some participants at baseline, we were unable to analyze the effect of serum 25(OH)D concentration on the presence of this population. Moreover, our study relied solely on baseline vitamin D levels and did not account for potential fluctuations in vitamin D concentrations during the follow-up period. Future studies should incorporate serial measurements of vitamin D to more accurately capture long-term exposure. Fourth, given that prediabetes represents a dynamic metabolic state, defining prediabetic individuals based solely on baseline HbA1c levels without considering changes in HbA1c over time may result in misclassification. This could potentially compromise the accuracy of our findings. Future research should include repeated HbA1c measurements to better characterize the metabolic profile of prediabetic individuals and its association with depression risk. Addressing these limitations in future studies will enhance the robustness and generalizability of the findings.

In conclusion, our study identified a significant inverse association between elevated serum 25(OH)D levels and the risk of depression in adults. Particularly among women aged ≤60 years, previous-smokers, with a BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2, sufficient sleep (7-8 hours/day) and current alcohol consumption. The results of this study may inform vitamin D supplementation programs for depressed patients in individuals with diabetes and prediabetes, and suggest the importance of correcting vitamin D deficiency.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Ling Gao developed the study protocol. Yiping Cheng participated in the development of the analysis plan. Huaxue Li and Guodong Liu contributed to the data analysis and wrote the first draft of the article. Yicheng Ma, Yingli Lu, Yingzhou Shi, Junming Han, Shengyu Tian, Peipei Wang, Qiang Wang and Hang Dong revised the manuscript to form the final version. Yiping Cheng contributed to the design of the study protocol and reviewed the manuscript. Guodong Liu contributed to the data analysis.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

UK BioBank has received Research Tissue Bank (RTB) approval from the North West Multicenter Research Ethics Committee (MREC). All participants signed written informed consent. The study protocol is available online (http://www.ukbiobank.ac.uk/).

Funding

This work was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (2021YFA0805100), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82400927), the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2023TQ0202 and 2023M742158), the Shandong Postdoctoral Science Foundation (SDBX2023035) and Shandong Natural Science Foundation (ZR2024QH324).

Availability of data and materials

This study used data from the UK Biobank (application number 89483). For details, please contact access@ukbiobank.ac.uk. All other data reported in this paper will be shared by the lead contact upon request.

This paper does not report original code.

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this work paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

Declaration of competing interest

No potential conflicts of interest related to this article are reported.

Acknowledgments

We thank all those involved in the UK Biobank project and those involved in establishing the UK Biobank research. Thanks for the icons provided by PowerPoint.

Footnotes

Supplementary material related to this article can be found, in the online version, at doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnha.2025.100556.

Contributor Information

Qiang Wang, Email: 15106954321@163.com.

Ling Gao, Email: linggao@sdu.edu.cn.

Yiping Cheng, Email: chengyiping93@163.com.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Rooney M.R., Fang M., Ogurtsova K., et al. Global prevalence of prediabetes. Diabetes Care. 2023;46(7):1388–1394. doi: 10.2337/dc22-2376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sun H., Saeedi P., Karuranga S., et al. IDF Diabetes Atlas: Global, regional and country-level Diabetes prevalence estimates for 2021 and projections for 2045. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2022;183 doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2021.109119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gregg E.W., Pratt A., Owens A., et al. The burden of diabetes-associated multiple long-term conditions on years of life spent and lost. Nat Med. 2024 doi: 10.1038/s41591-024-03123-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nathan D.M. Long-term complications of diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 1993;328(23):1676–1685. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199306103282306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harding J.L., Pavkov M.E., Magliano D.J., et al. Global trends in diabetes complications: a review of current evidence. Diabetologia. 2019;62(1):3–16. doi: 10.1007/s00125-018-4711-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wan Z., Guo J., Pan A., et al. Association of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations with all-cause and cause-specific mortality among individuals with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2021;44(2):350–357. doi: 10.2337/dc20-1485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fan X., Wang J., Song M., et al. Vitamin D status and risk of all-cause and cause-specific mortality in a large cohort: results from the UK biobank. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2020;105(10) doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgaa432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang P., Guo D., Xu B., et al. Association of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D with cardiovascular outcomes and all-cause mortality in individuals with prediabetes and diabetes: results from the UK biobank prospective cohort study. Diabetes Care. 2022;45(5):1219–1229. doi: 10.2337/dc21-2193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Geng T., Lu Q., Wan Z., et al. Association of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations with risk of dementia among individuals with type 2 diabetes: a cohort study in the UK Biobank. PLoS Med. 2022;19(1) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Md I.Z., Amsah N., Ahmad N. The impact of vitamin D deficiency and insufficiency on the outcome of type 2 diabetes mellitus patients: a systematic review. Nutrients. 2023;15(10) doi: 10.3390/nu15102310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Isaia G., Giorgino R., Adami S. High prevalence of hypovitaminosis D in female type 2 diabetic population. Diabetes Care. 2001;24(8):1496. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.8.1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Al A.T., Ashfaq A., Saheb S.N., et al. Investigating the association between diabetic neuropathy and vitamin D in emirati patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cells. 2023;12(1) doi: 10.3390/cells12010198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Allen N.E., Lacey B., Lawlor D.A., et al. Prospective study design and data analysis in UK Biobank. Sci Transl Med. 2024;16(729) doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.adf4428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Addendum 2. Classification and Diagnosis of Diabetes: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2021. Diabetes Care. 2021;44(Suppl. 1):S15–S33. Diabetes Care, 2021,44(9):2182. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Levis B., Benedetti A., Thombs B.D. Accuracy of Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) for screening to detect major depression: individual participant data meta-analysis. BMJ. 2019;365 doi: 10.1136/bmj.l1476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhu D.M., Zhao W., Zhang B., et al. The relationship between serum concentration of vitamin D, Total intracranial volume, and severity of depressive symptoms in patients with major depressive disorder. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10:322. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Panza F., Solfrizzi V., Barulli M.R., et al. Cognitive frailty: a systematic review of epidemiological and neurobiological evidence of an age-related clinical condition. Rejuvenation Res. 2015;18(5):389–412. doi: 10.1089/rej.2014.1637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Annweiler C., Montero-Odasso M., Llewellyn D.J., et al. Meta-analysis of memory and executive dysfunctions in relation to vitamin D. J Alzheimers Dis. 2013;37(1):147–171. doi: 10.3233/JAD-130452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anderson R.J., Freedland K.E., Clouse R.E., et al. The prevalence of comorbid depression in adults with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2001;24(6):1069–1078. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.6.1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fujikawa L.S., Salahuddin S.Z., Ablashi D., et al. Human T-cell leukemia/lymphotropic virus type III in the conjunctival epithelium of a patient with AIDS. Am J Ophthalmol. 1985;100(4):507–509. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(85)90671-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Milaneschi Y., Hoogendijk W., Lips P., et al. The association between low vitamin D and depressive disorders. Mol Psychiatry. 2014;19(4):444–451. doi: 10.1038/mp.2013.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khan B., Shafiq H., Abbas S., et al. Vitamin D status and its correlation to depression. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2022;21(1):32. doi: 10.1186/s12991-022-00406-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang Y., Yang H., Meng P., et al. Association between low serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D and depression in a large sample of Chinese patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Affect Disord. 2017;224:56–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.10.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brouwer-Brolsma E.M., Dhonukshe-Rutten R.A., van Wijngaarden J.P., et al. Low vitamin D status is associated with more depressive symptoms in Dutch older adults. Eur J Nutr. 2016;55(4):1525–1534. doi: 10.1007/s00394-015-0970-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mao Y., Li X., Li Y., et al. Association of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin d concentrations with all-cause and cause-specific mortality among individuals with depression: a cohort study. J Affect Disord. 2024;352:10–18. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2024.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aljack H.A., Abdalla M.K., Idris O.F., et al. Vitamin D deficiency increases risk of nephropathy and cardiovascular diseases in Type 2 diabetes mellitus patients. J Res Med Sci. 2019;24:47. doi: 10.4103/jrms.JRMS_303_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sacerdote A., Dave P., Lokshin V., et al. Type 2 diabetes mellitus, insulin resistance, and vitamin D. Curr Diab Rep. 2019;19(10):101. doi: 10.1007/s11892-019-1201-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lips P., Eekhoff M., van Schoor N., et al. Vitamin D and type 2 diabetes. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2017;173:280–285. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2016.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bouillon R., Carmeliet G., Verlinden L., et al. Vitamin D and human health: lessons from vitamin D receptor null mice. Endocr Rev. 2008;29(6):726–776. doi: 10.1210/er.2008-0004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mitri J., Pittas A.G. Vitamin D and diabetes. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2014;43(1):205–232. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2013.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liefaard M.C., Ligthart S., Vitezova A., et al. Vitamin D and C-reactive protein: a mendelian randomization study. PLoS One. 2015;10(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0131740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Basiri R., Seidu B., Rudich M. Exploring the interrelationships between diabetes, nutrition, anxiety, and depression: implications for treatment and prevention strategies. Nutrients. 2023;15(19) doi: 10.3390/nu15194226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huang C.J., Wang S.Y., Lee M.H., et al. Prevalence and incidence of mental illness in diabetes: a national population-based cohort study. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2011;93(1):106–114. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2011.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kuehner C. Gender differences in unipolar depression: an update of epidemiological findings and possible explanations. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2003;108(3):163–174. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2003.00204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nishizawa S., Benkelfat C., Young S.N., et al. Differences between males and females in rates of serotonin synthesis in human brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94(10):5308–5313. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.10.5308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cui A., Zhang T., Xiao P., et al. Global and regional prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in population-based studies from 2000 to 2022: a pooled analysis of 7.9 million participants. Front Nutr. 2023;10 doi: 10.3389/fnut.2023.1070808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Goldstein B.I., Blanco C., He J.P., et al. Correlates of overweight and obesity among adolescents with bipolar disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey-Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A) J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2016;55(12):1020–1026. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2016.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shab-Bidar S., Neyestani T.R., Djazayery A., et al. Improvement of vitamin D status resulted in amelioration of biomarkers of systemic inflammation in the subjects with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2012;28(5):424–430. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.2290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Martens P.J., Gysemans C., Verstuyf A., et al. Vitamin D’s effect on immune function. Nutrients. 2020;12(5) doi: 10.3390/nu12051248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Park C.Y., Shin S., Han S.N. Multifaceted roles of vitamin D for diabetes: from immunomodulatory functions to metabolic regulations. Nutrients. 2024;16(18) doi: 10.3390/nu16183185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.van den Berg K.S., Marijnissen R.M., van den Brink R.H., et al. Vitamin D deficiency, Depression course and mortality: longitudinal results from the Netherlands Study on Depression in Older persons (NESDO) J Psychosom Res. 2016;83:50–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2016.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kjaergaard M., Waterloo K., Wang C.E., et al. Effect of vitamin D supplement on depression scores in people with low levels of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D: nested case-control study and randomised clinical trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2012;201(5):360–368. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.111.104349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shaffer J.A., Edmondson D., Wasson L.T., et al. Vitamin D supplementation for depressive symptoms: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Psychosom Med. 2014;76(3):190–196. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xie F., Huang T., Lou D., et al. Effect of vitamin D supplementation on the incidence and prognosis of depression: an updated meta-analysis based on randomized controlled trials. Front Public Health. 2022;10 doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.903547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Saji P.N., Krishna P.V., Gupta A., et al. Depression and vitamin D: a peculiar relationship. Cureus. 2022;14(4) doi: 10.7759/cureus.24363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mikola T., Marx W., Lane M.M., et al. The effect of vitamin D supplementation on depressive symptoms in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2023;63(33):11784–11801. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2022.2096560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang R., Xu F., Xia X., et al. The effect of vitamin D supplementation on primary depression: a meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2024;344:653–661. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2023.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Abiri B., Sarbakhsh P., Vafa M. Randomized study of the effects of vitamin D and/or magnesium supplementation on mood, serum levels of BDNF, inflammation, and SIRT1 in obese women with mild to moderate depressive symptoms. Nutr Neurosci. 2022;25(10):2123–2135. doi: 10.1080/1028415X.2021.1945859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Husemoen L.L., Skaaby T., Thuesen B.H., et al. Serum 25(OH)D and incident type 2 diabetes: a cohort study. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2012;66(12):1309–1314. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2012.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhou J., Li D., Wang Y. Vitamin D Deficiency participates in depression of patients with diabetic peripheral neuropathy by regulating the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2024;20:389–397. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S442654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Maina J.G., Balkhiyarova Z., Nouwen A., et al. Bidirectional mendelian randomization and multiphenotype GWAS show causality and shared pathophysiology between depression and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2023;46(9):1707–1714. doi: 10.2337/dc22-2373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

This study used data from the UK Biobank (application number 89483). For details, please contact access@ukbiobank.ac.uk. All other data reported in this paper will be shared by the lead contact upon request.

This paper does not report original code.

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this work paper is available from the lead contact upon request.