Abstract

Diabetic retinopathy (DR) is characterized by pathological angiogenesis, inflammation, and retinal neurodegeneration, leading to vision loss. Current therapies, such as anti-VEGF agents, face challenges of low bioavailability and frequent invasive injections. Connexin43 (Cx43), a gap junction protein, plays a key role in DR progression through its modulation of inflammation and vascular dysfunction. A thermosensitive hydrogel composite was developed to encapsulate siRNA targeting Cx43 (si-Cx43) nanoparticles (NPs) and anti-VEGF (Avastin). The hydrogel was characterized for gelation, injectability, and degradation. In vitro studies evaluated the cytotoxicity, anti-angiogenic effects, and permeability regulation in hyperglycemic retinal cells under hyperglycemic conditions. In vivo therapeutic efficacy was assessed in a diabetic retinopathy rat model. si-Cx43-NPs demonstrated high siRNA encapsulation efficiency and stability, effectively silencing Cx43 expression in retinal endothelial cells. The hydrogel exhibited excellent injectability, temperature-sensitive gelation, and controlled degradation. In vitro, si-Cx43-NPs@Avastin-hydrogel significantly suppressed VEGF expression, reduced angiogenesis, and restored cell permeability under hyperglycemic conditions. In vivo, the hydrogel composite reduced neovascularization, inflammation, and apoptosis, restoring retinal structure and function more effectively than either single-agent treatment alone. Biocompatibility studies confirmed minimal toxicity and favorable degradation. The si-Cx43-NPs@Avastin-hydrogel provides a synergistic and minimally invasive therapeutic strategy for DR by targeting angiogenesis, inflammation, and neuroprotection with sustained drug delivery.

Keywords: Diabetic retinopathy, si-Cx43 nanoparticles, Anti-VEGF, Thermosensitive hydrogel, Angiogenesis, Inflammation

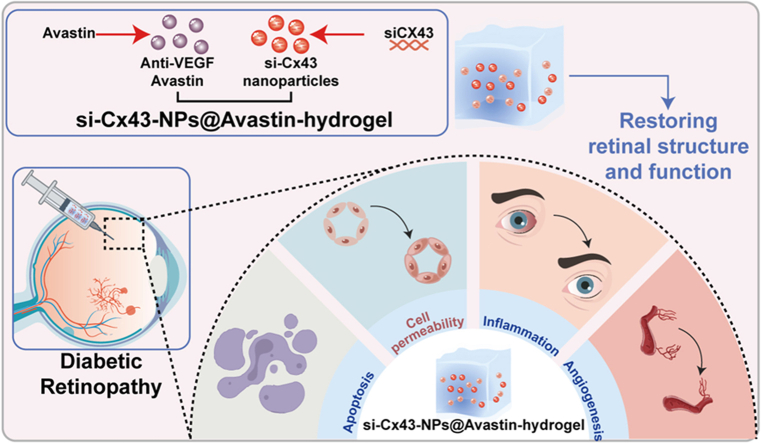

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Diabetic retinopathy (DR) is the most prevalent microvascular complication of diabetes and a major cause of vision loss within adults worldwide [1,2]. Clinically, DR is defined by a spectrum of retinal microvascular lesions, including neovascularization, fibrovascular membranes, and retinal capillary impairment, which lead to secondary visual loss [3]. Despite advances in understanding the multifactorial pathogenesis of DR, the complex molecular mechanisms remain unclear.

The pathological hallmarks of DR include retinal microvascular damage, inflammation, and abnormal angiogenesis, driven by chronic hyperglycemia [4,5]. Among the key mediators of DR, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) crucially enhances retinal neovascularization and vascular permeability [6]. Elevated VEGF levels correlate with disease progression and are critical targets for therapeutic intervention [4,7]. Current treatments for DR, such as intravitreal administrations of anti-VEGF agents (e.g., bevacizumab), have shown clinical efficacy in reducing neovascularization and vascular leakage [8,9]. These findings have led to considerable developments in DR treatment using anti-VEGF therapy over the past several years [10]. Furthermore, connexin43 (Cx43), a major gap junction protein, is associated with DR pathogenesis through its effect on inflammation and vascular dysfunction [11]. Given the participation of Cx43 hemichannel-mediated communication in tissue impairment during secondary complications of diabetes [[12], [13], [14]], drugs targeting Cx43 hemichannels have been identified as potential anti-inflammatory therapies [15,16]. In our previous study, Cx43 overexpression amplified the alteration caused by high glucose within human retinal endothelial cells (hRECs), whereas Cx43 knockdown significantly improved retinal structure and decreased TNF-α, IL-1β, VEGFA, and ICAM-1 mRNA expression within a DR mouse model [17]. However, existing ocular drug delivery carriers are limited by the low bioavailability of drug formulations and the need for repeated invasive intravitreal injections, which complicate drug regimens and increase the risk of systemic adverse effects [[18], [19], [20], [21], [22]]. Therefore, ocular barriers and the risk of drug degradation hinder the efficient and sustained administration of therapeutic medicines targeting both VEGF and Cx43.

Thermosensitive hydrogels, which undergo phase transitions at physiological temperatures, provide an injectable and minimally invasive platform for localized drug delivery in ocular diseases [23,24]. They attract increasing attention because of their ease of application, high biocompatibility, and tailorable characteristics. Over the last decade, thermogels have been regarded as appropriate materials for treating diabetic ocular disorders [25]. Their ability to act as drug delivery depots, provide sustained therapeutic viability, and be designed as mechanically durable and non-toxic implants makes them suitable for replicating ocular tissue characteristics. Therefore, to overcome the challenges of anti-VEGF and targeting Cx43, we propose the development of a thermosensitive hydrogel composite system loaded with siRNA nanoparticles targeting Cx43 (si-Cx43) and anti-VEGF drugs. By encapsulating si-Cx43 nanoparticles and anti-VEGF drugs, the composite hydrogel can achieve synergistic therapeutic effects, improving treatment efficacy while reducing the frequency of administration.

In this study, the si-Cx43 nanoparticle-anti-VEGF hydrogel composite system was prepared to effectively inhibit inflammation and angiogenesis in DR and characterized, its biocompatibility and degradation were evaluated, and its therapeutic effects were tested in vitro and in vivo using DR models. Therefore, the aim of this study was to explore the potential of this new drug delivery system for DR treatment.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Synthesis of lipid-polymer-siRNA complex (LPP)

Lipid-polymer-siRNA complexes (LPPs) were synthesized by combining cationic polymers with lipid nanoparticles and siRNA. Polyethyleneimine (PEI, P434399-250 mg, CAS 9002-98-6, Aladdin, Shanghai, China) was mixed with dichlorocyan (DICY) and reacted at 100 °C for 24 h to form PolyMet. PolyMet was then purified using ultrafiltration and lyophilized for subsequent use. PolyMet and siRNA (hsa-si-Cx43 sense: 5′-GGGUCCUGCAGAUCAUAUUTT-3′ anti-sense 5′-AAU AUG AUC UGC AGG ACC CTT-3′, rno-si-Cx43 sense: 5′-GGG UCC UUC AGA UCA UAU UTT-3′, anti-sense: 5′-AAU AUG AUC UGA AGG ACC CTT-3′ General Bio, Chuzhou, China) were incubated according to different N/P ratios (N/P = 10 20 30), and the optimal ratio was determined through Gel retardation assay.

Liposomes were prepared using a combination of lipids, 1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DPPC, D990047-100 mg, Macklin, Shanghai, China), 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine (DOPE, D869719-50 mg, Macklin), hydrogenated soy phosphatidylcholine (HSPC, H498541-25 mg, Aladdin), cholesterol (C8667-500 MG, Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA), and DSPE-mPEG2000 (LP-R4-039, Sigma), at 10:5:33:26:6 M ratio dissolved in chloroform. A lipid thin film was created using a rotary evaporator (Shanghai Eyela, RE-201D) under vacuum at 40 °C, and liposomes were formed by hydrating the film with distilled water at 55 °C for 1 h. The PolyMet-siRNA complex was combined with liposomes at a 7:1 mass ratio to prepare LPPs, followed by vortex mixing and incubation at 37 °C for 1 h.

2.2. Gel retardation assay

A gel retardation assay was used to analyze the complexation of siRNA with PEI and LPP formation. Naked siRNA (20 pmol) was subjected to 30-min incubation at room temperature (RT) with PEI at N/P ratios of 10, 20, and 30. The specimens were loaded on a 1 % agarose gel prepared in Tris-acetate-EDTA (TAE) buffer added with GelRed™ nucleic acid stain (41003, Biotium, Fremont, CA, USA). Electrophoresis was conducted at 120 V for 20 min using a gel electrophoresis apparatus (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). A gel documentation system (Bio-Rad) was used to perform gel imaging. Reduced electrophoretic mobility indicated successful complexation of siRNA with PEI, with complete retardation observed at N/P ratios ≥20.

2.3. RNase A protection assay

LPPs-siRNA complexes (20 pmol siRNA) were subjected to 30-min incubation at 37 °C with RNase A (1 U/μg, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) to assess the protective ability of LPPs against RNase A digestion. 0.5 μL RNase OUT (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was employed to terminate the reaction, followed by 15-min treatment at RT with Triton X-100 (Sigma) and heparin (10 IU, Sigma). The agarose gel electrophoresis was utilized to evaluate the integrity of siRNA.

2.4. siRNA encapsulation efficiency

The encapsulation efficiency of siRNA into LPPs was determined using StarGreen safe nucleic acid dye (Sigma). Specimens were subjected to 5-min centrifugation at 1000 rpm to isolate free siRNA in the supernatant from encapsulated siRNA in the pellet. Each fraction (100 μL) was incubated with 0.01 μL of StarGreen dye for 30 min in the dark. A microplate reader (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used to measure fluorescence intensity at emission wavelengths of 510 nm. The following formula was applied to calculate encapsulation efficiency:

2.5. siRNA release in competitive heparin conditions

LPPs-siRNA complexes (20 pmol siRNA) were subjected to 30-min incubation at 37 °C with varying concentrations of heparin (0.25–2 IU) to analyze the production of siRNA from LPPs with heparin. Subsequently, the specimens were supplemented with StarGreen dye, and a microplate reader (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) was employed to measure fluorescence intensity at emission wavelengths of 510 nm. The following formula was used to calculate the relative release of siRNA:

2.6. Particle size, polydispersity index (PDI), and zeta potential measurement

A Zetasizer Nano ZS-90 (Malvern Panalytical, Worcestershire, UK) was utilized to analyze the particle size, PDI, and zeta potential of LPPs. After being diluted 100-fold in sterile 1 % DEPC-treated water, samples were analyzed at 25 °C. The instrument parameters were set as per the protocols of the manufacturer, and assessments were carried out three times.

2.7. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

The LPP morphology was evaluated using TEM (JEM-F200, JEOL, Tokyo, Japan). Samples were prepared by diluting LPPs to 0.05–0.08 % solid content and mixing with 2 % phosphotungstic acid (pH 6–7) for negative staining. A drop of the stained specimen was placed upon a carbon-coated copper grid and dried under UV light. TEM images were captured at appropriate magnifications.

2.8. Cell line and cell cultivation

Human retinal endothelial cells (hRECs; Catalog #6530) were procured from ScienCell (Carlsbad, CA, USA) and cultured in Endothelial Cell Medium (ECM, Cat. #1001, ScienCell) containing 5 % FBS (Cat. #0025, ScienCell). The cells were cultured at 37 °C in a 5 % CO2 atmosphere. For experiments, cells were planted onto appropriate culture plates (1 × 105 cells/mL), followed by 24-h adhesion. Medium was replaced every 2 days, with cells reaching 70–80 % confluency used for further treatments. Cell detachment was performed using 0.25 % trypsin-EDTA solution (25200056, Thermo Fisher Scientific).

2.9. Cellular uptake and intracellular distribution of LPP

Cellular uptake and intracellular distribution of siRNA LPPs were determined in hRECs. Cells were treated with siRNA LPPs labeled with 6-FAM (100 pmol) for 4 h and fixed with 4 % paraformaldehyde, followed by staining with DAPI (Sigma). A fluorescence microscope (Olympus, Japan) was applied to image samples.

2.10. qRT-PCR

The mRNA level of Cx43 in hRECs treated with si-Cx43 nanoparticles (si-Cx43-NPs) or negative control was analyzed using quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR). TRIzol™ reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was employed as per the instructions of the manufacturer to extract total RNA from cells. A NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was utilized to determine RNA concentration and purity. A cDNA synthesis kit (A3500, Promega, Madison, WI, USA) was used to perform reverse transcription. SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (4367659, Thermo Fisher Scientific) on a StepOnePlus™ Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, MA, USA) was used to perform qRT-PCR. Specific primers for Cx43 and β-actin were used, with β-actin serving as the internal reference. The sequences of primers are detailed in Table S1. The 2−ΔΔCt method was applied to calculate relative mRNA expression levels. Each reaction was repeated three times.

2.11. Immunoblotting

RIPA buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) containing a protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma) was used to extract total protein. A BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was utilized to determine protein concentration. Following electrophoresis by 10 % SDS-PAGE, the separated proteins were electroblotted from the gel onto PVDF membranes (IPVH00010, Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA). Membranes were subjected to blocking with 5 % skim milk in TBST, followed by an overnight incubation with primary antibodies against Cx43 (#3512, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA), VEGF (19003-1-AP, Proteintech, Wuhan, China), Snail1 (13099-1-AP, Proteintech), occludin (27260-1-AP, Protientech), E-cadherin (20874-1-AP), N-cadherin (22018-1-AP, Proteintech), vimentin (60330-1-Ig, Protientech), and β-actin (A5316, Sigma), and then with HRP-labeled secondary antibodies. Super Enhanced Chemiluminescence (ECL) Detection Reagent (Beyotime) was employed to visualize, and ImageJ software was applied to quantify protein bands.

2.12. Synthesis of si-Cx43-NPs@Avastin-hydrogel

Thermosensitive hydrogel composites were synthesized by modifying hyaluronic acid (HA) to introduce methacrylate groups. HA (S24592-25g, Yuanye Bio, Shanghai, China) was dissolved within deionized water, and methacrylic anhydride (MA, 276685-100 ML, Sigma) was supplemented dropwise under constant stirring at 4 °C. 5 M NaOH was utilized to adjust the pH to 8–9. The reaction proceeded for 24 h, and the modified HA (HA-MA) was purified using dialysis membranes (8000–10000, SP131273-0.5m, Yuanye Bio) against deionized water for 4 days, followed by lyophilization. The thermosensitive hydrogel was formed by polymerization of HA-MA (0.2 g solved in 180 mL ddH2O) in the presence of N,N,N′,N′-tetramethylethylenediamine (TEMED, 8087420250, Sigma) (7 mL 4 v/v%), ethyl methacrylate (8005790100, Sigma) (7 mL 10 m/v%) and potassium peroxydisulfate (60489-250G-F, Sigma) (7 mL 10 m/v%) at 20 °C for 24 h purged with nitrogen, followed by lyophilization. si-Cx43 LPPs (1 mg/mL) and Avastin (VEGFA antibody, HY-P9906, MedChemExpress, Monmouth Junction, NJ, USA) (25 mg/mL) were incorporated into the 3 % thermosensitive hydrogel (diluted by ddH2O) to create si-Cx43-NPs@Avastin-hydrogel.

The gelation process was observed at 25 °C and 37 °C to assess temperature-sensitive behavior. si-Cx43-NPs@Avastin-hydrogel was prepared and stored in glass vials to observe liquid-to-gel transitions visually at different temperatures. The injectability of si-Cx43-NPs@Avastin-hydrogel was evaluated by loading the hydrogel into a 1 mL syringe equipped with a 26-gauge needle. After extruding the hydrogel through the needle, and the smoothness of injection was recorded at RT.

2.13. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

The hydrogel microstructure was examined using SEM (TESCAN MIRA LMS, Czech Republic). Hydrogel specimens were prepared via freeze-fracturing in liquid nitrogen and mounting on SEM stubs with conductive adhesive, followed by sputter-coating using a thin layer of gold under vacuum. Images were captured at magnifications of 1000 × , 2000 × , 5000 × , and 10,000 × to analyze the internal porous structure.

2.14. Rheological analysis

A rheometer (Haake Mars 40, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) was utilized to analyze the viscoelastic properties of the hydrogel. Storage modulus (G′) and loss modulus (G″) were determined under temperature sweep conditions of 0–80 °C. A fixed strain and frequency were applied to ensure the linear viscoelastic range. The phase transition temperature was identified based on the intersection of G′ and G″ curves, suggesting a transition from liquid to gel state.

2.15. Degradation study

The degradation profile of the hydrogels was evaluated in artificial tears (0.9 % NaCl, 0.15 % NaHCO3, 0.02 % boric acid, 0.5 % mannitol, and 0.1 % sodium hyaluronate) and citrate-phosphate buffer (pH 5.5). Pre-weighed hydrogel samples were subjected to incubation in 37 °C solutions. At specified intervals, the samples were discarded, dried at 60 °C for 6 h, and reweighed to calculate mass loss. The following formula was applied to calculate the degradation rate:

2.16. Chorioallantoic membrane (CAM) assay

The CAM assay was employed to assess the antiangiogenic activity of the hydrogel formulations. Fertilized chicken eggs were subjected to 3-day incubation in a atmosphere of 37 °C and 60–70 % humidity. After creating a 1 cm2 window in the eggshell, the inner shell membrane was removed to expose the CAM. On day 7, 50 μL of hydrogel, Avastin, or sterile PBS was applied to the CAM. After 48 h of incubation, images of the CAM were captured to quantify the number of secondary and tertiary blood vessels using ImageJ software. The compatibility of hydrogels with ocular tissues was evaluated using a HET-CAM test. Hydrogels were applied to the CAM, and irritation responses (e.g., bleeding, vessel lysis, or coagulation) were recorded over 5 min.

2.17. CCK-8 cytotoxicity assay

A CCK-8 assay was utilized to evaluate the cytotoxicity of LPPs and hydrogels. Human retinal endothelial cells (hREC) were planted onto a transwell lower chamber of 24-well plates (2 × 104 cells per well), followed by culture within endothelial cell medium (ECM, 1001, ScienCell, Carlsbad, CA, USA) containing 5 % FBS (ScienCell, Carlsbad, CA, USA). After 24 h, the upper chamber was added with various formulations, including si-Cx43 NPs, Avastin, blank hydrogel, Avastin-hydrogel, si-Cx43-NPs@Avastin-hydrogel, and cisplatin as a positive control (P4394, Sigma). Untreated cells were used as the negative control. After 48 h of incubation, each well was supplemented with 10 % CCK-8 reagent (CK04, Dojindo, Kumamoto, Japan), followed by 2-h incubation at 37 °C. A microplate reader (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) was used to measure the optical density (OD) at a wavelength of 450 nm.

2.18. Immunofluorescence staining (IF staining)

hRECs were plated in the lower chamber of 24-well transwell for 24h and then the culture medium was replaced to high glucose (HG, 30 mM) [26,27] culture medium. HRECs were incubated with si-Cx43 NPs, Avastin, blank hydrogel, Avastin-hydrogel, si-Cx43-NPs@Avastin-hydrogel in the upper chamber, respectively. 48 h later, cells were subjected to 10-min fixation with 4 % paraformaldehyde (P6148, Sigma), 5-min permeabilization with 0.1 % Triton X-100 (T9284, Sigma), and 1-h blocking at RT with 5 % bovine serum albumin (BSA, Sigma). Cells were subjected to an overnight incubation at 4 °C with antibodies against Ki-67 (ab15580, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), occludin (27260-1-AP, Protientech), E-cadherin (20874-1-AP), vimentin (60330-1-Ig, Protientech), GFAP (ab7260, Abcam), VEGF (19003-1-AP, Proteintech), and then an 1-h incubation at RT with an Alexa Fluor 594-labeled or Alexa Fluor 488-labeled secondary antibody (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Nuclei were subjected to staining with DAPI (Sigma). A fluorescence microscope (Olympus) was utilized to capture fluorescence images integrated density of fluorescence was measured by Image J software (NIH).

2.19. Tube formation assay

A tube formation assay was used to assess the anti-angiogenic effects of the LPPs and hydrogels. hRECs culture was performed as above mentioned, then collected for tube formation assay. Matrigel (Corning, New York, NY, USA) was coated onto pre-chilled 96-well plates (50 μL per well), followed by 30-min polymerization at 37 °C. hRECs were planted on the Matrigel-coated wells (1 × 104 cells per well). After 6-h incubation at 37 °C, an inverted microscope (Olympus IX71, Tokyo, Japan) was applied to image tube formation. ImageJ software was employed to quantify the total tube length and the number of branching points.

2.20. Transwell migration assay

The migration of hRECs treated with different formulations was evaluated using a Transwell migration assay. hRECs were collected and were planted into the top chamber of Transwell inserts (8 μm pore size, CLS3422, Corning) at a density of 2 × 104 cells per well within serum-free media. The media added with 10 % FBS and different treatments included high glucose (HG), HG + si-Cx43 nanoparticles, HG + Avastin, HG + Avastin-hydrogel, and HG + si-Cx43-NPs@Avastin-hydrogel. Following 24-h incubation at 37 °C, a cotton swab was utilized to remove the cells that did not migrate upon the top surface of the membrane. Migrated cells upon the bottom surface were subjected to fixation with 4 % paraformaldehyde and staining with 0.1 % crystal violet (Sigma), and then a light microscope (Olympus) was applied to image cells. ImageJ software was applied to quantify the migrated cell number.

2.21. ELISA

The TNF-α, IFN-γ, and IL-1β protein contents within hRECs homogenates or VEGF levels in retinal tissues were measured using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA). Homogenates were prepared by lysing hRECs and rat retinal tissues in RIPA buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) supplemented with protease inhibitors (P8340, Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA), which were then subjected to 10-min centrifugation at 12,000 g at 4 °C to obtain the supernatant. TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL-1β in hRECs homogenates, and VEGF levels in rat retinal tissue homogenates were quantified using ELISA kits (TNF-α: E-EL-H019 BMS228 for human, E-EL-R2856 for rat, Elabscience, Wuhan, China; IFN-γ: E-EL-H0108, E-EL-R0009; Elabscience; IL-1β: E-EL-H0149, E-EL-R0009; VEGFA: ml002862 for rat, Mlbio, Shanghai, China) as per the protocols of the manufacturer. A microplate reader (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) was used to measure the absorbance at 450 nm. The standard curves were utilized to calculate the protein concentrations.

2.22. Animal model of DR

A diabetic rat model was constructed by repeated intraperitoneal (i.p.) injections of streptozotocin (STZ, S0130, Sigma) at a dose of 60 mg/kg for five consecutive days. A glucometer (Accu-Chek, Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland) was utilized to monitor blood glucose levels weekly, and rats with blood glucose levels higher than 16.7 mmol/L were considered diabetic and the time was set as week 0. Treatments were administered via intravitreal injections at week 0 and week 4 as previously described [28]. Groups included: (1) normal control (no STZ injection and no intravitreal injection), (2) sham surgery (DR modeling with empty syringe intravitreal injection), (3) si-Cx43 nanoparticles (DR modeling with 5 μL intravitreal injection), (4) Avastin group (DR modeling with 5 μL, 25 mg/mL), (5) Avastin-hydrogel (DR modeling with 5 μL), and (6) si-Cx43-NPs@Avastin-hydrogel (DR modeling with 5 μL). Rats were sacrificed at 8 weeks for analysis. The targeted rat si-Cx43 was purchased from General Bio and si-Cx43-NPs and si-Cx43-NPs@Avastin-hydrogel were synthesized as mentioned above. All the procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, Second Xiangya Hospital, Central South University (No.20230333).

Regarding the validation of the model, blood glucose levels were monitored weekly and only rats with consistently high glucose levels (>16.7 mmol/L) were included in our study. Secondly, retinal changes were assessed using optical coherence tomography (OCT), allowing visualization and quantification of retinal thickness and structural abnormalities associated with DR, such as neovascularization. Finally, histological analysis (H&E staining) and immunofluorescence staining were performed for VEGFA in retinal tissues to examine pathological changes at the cellular level.

2.23. Optical coherence tomography (OCT)

Retinal structure and neovascularization were evaluated using OCT (Heidelberg Spectralis, Heidelberg Engineering, Heidelberg, Germany). Ketamine (50 mg/kg, Sigma) and xylazine (10 mg/kg, Sigma) were employed to anesthetize rats, and pupils were dilated using tropicamide (Alcon, Geneva, Switzerland). OCT imaging was performed to analyze retinal thickness and structural abnormalities, with a focus on regions exhibiting neovascularization.

2.24. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining and IF staining of retinal tissues

H&E staining was used to perform histopathological analysis of retinal microstructures. The collected retinal tissues were subjected to 24-h fixation within 4 % paraformaldehyde, and paraffin-embedded. The 5-μm thick slices were deparaffinized and rehydrated, followed by 5-min staining with hematoxylin and 2-min staining with eosin. Slices were dehydrated, cleared, and mounted using DPX mounting medium (Sigma). A light microscope (Olympus) was applied to capture images. Retinal layer thickness and basement membrane morphology were evaluated to assess pathological changes such as edema, vascular congestion, and increased tortuosity. Major organ sections were analyzed for signs of drug toxicity, including inflammation, cellular necrosis, and other pathological abnormalities. A light microscope (Olympus) was applied to capture images at 400 × magnification.

After deparaffinized and blocked, the retinal tissue sections were further incubated with primary antibodies against GFAP, VEGF and occludin (Proteintech) at 4 °C overnight. After washing with PBS three times, Slices were rinsed in PBS thrice, followed by incubation for 1 h at room temperature with Alex Fluor 594-labeled secondary antibody (Invitrogen). Then, slices were washed in PBS, followed by incubation for 5 min in DAPI (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) and fluorescence microscopy (Olympus) was applied to analyze the fluorescent density.

2.25. Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferased UTP nick-end labeling (TUNEL) assay

A TUNEL assay was employed to assess retinal cell apoptosis. Retinal sections were prepared as described for H&E staining. Apoptotic cells were labeled using a Colorimetric TUNEL Apoptosis Assay kit (Beyotime) as per the instructions of the manufacturer. Slices were deparaffinized and rehydrated, followed by incubation with a TUNEL reaction mixture containing terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase and Biotin-labeled dUTP at 37 °C at dark. After washing, slices were subjected to counterstaining with streptavidin-HRP solution and DAB solution. A light microscope was employed to visualize apoptotic cells (brown nucleus), and the apoptotic index was computed as the TUNEL-positive cell percentage divided by the total cell number.

2.26. In vivo degradation and biocompatibility of hydrogel

The degradation and biocompatibility of the hydrogel were evaluated in a time-dependent manner. Hydrogels were subcutaneously injected into rats, and their degradation was monitored on days 1, 3, 5, 9, and 12. Photographs of the hydrogel at the injection site were taken, and tissue sections surrounding the hydrogel were prepared as described for H&E staining. Histological evaluation of dermal and muscle tissues was performed to assess inflammation and other pathological changes.

2.27. Statistical analysis

All data are expressed as the mean ± standard error (SD). GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA) was employed to perform Student's t-test for two-group comparisons or one-way ANOVA with Tukey's post-hoc test for multiple comparisons. The significance level was set at P < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Preparation and characterization of si-Cx43 nanoparticles (LPP-siRNA)

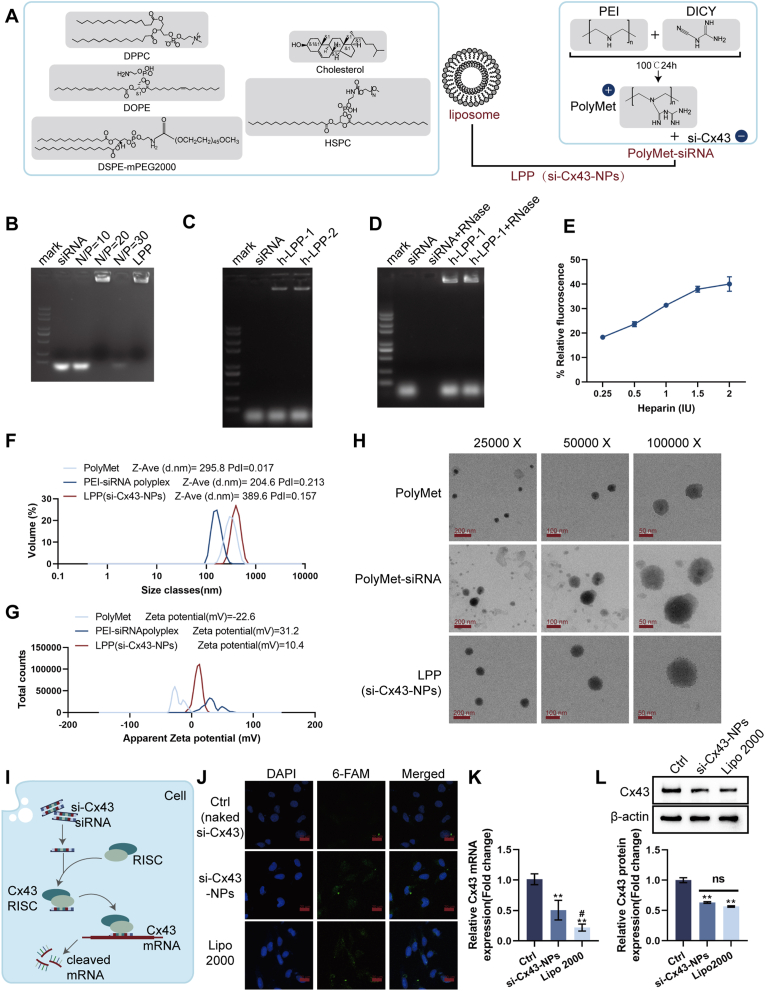

First, siRNA was utilized to formulate a cationic polymer (polyethylenimide (PEI)) and a lipid nanoparticle (liposome), thereby forming a lipid polycomplex (LPP) for the delivery of Cx43-siRNA; the physicochemical characteristics of the complex were examined under controlled experimental conditions (Fig. 1A). In the gel retardation assay, siRNA and PEI were combined at varying N/P ratios. Compared to the siRNA-only group, PEI-siRNA complexes at N/P ≥ 20 significantly delayed the migration of siRNA, demonstrating efficient complexation of siRNA with PEI and subsequent incorporation into LPP (Fig. 1B). Serum stability was assessed by incubating LPP-siRNA with FBS. Compared to the siRNA-only group, the LPP-siRNA group demonstrated significantly enhanced protection against degradation in the presence of serum (Fig. 1C). In the RNase protection assay, compared to siRNA treated with RNase, LPP-siRNA complexes maintained siRNA integrity, confirming their protective effects (Fig. 1D). The siRNA encapsulation efficiency of LPP was determined as 57.81 % using fluorescence analysis (Fig. 1E). Competitive ligand (heparin)-induced siRNA release demonstrated 40.06 ± 2.96 % siRNA release from LPP, indicating the stability of the nanoparticles (Fig. 1E). DLS analysis revealed that LPP had a larger particle size (389.6 nm) but a more favorable zeta potential (10.4 mV) compared to PEI-siRNA polyplex (204.6 nm, 31.2 mV) (Fig. 1F and G). TEM imaging confirmed uniform spherical morphology of LPP (Fig. 1H).

Fig. 1.

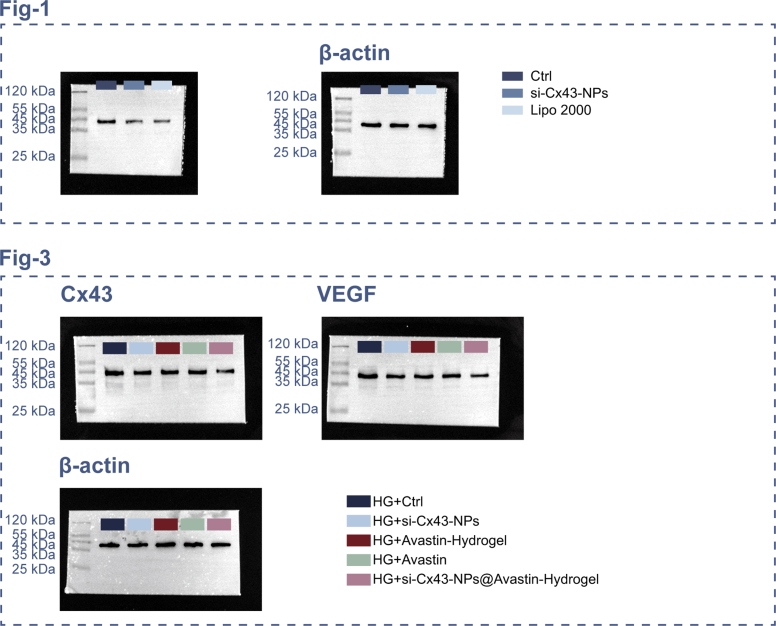

Preparation and characterization of si-Cx43 nanoparticles (LPP-siRNA) (A) Schematic illustration of the synthesis of LPP-siRNA using cationic polymer (PEI) and lipid nanoparticles. (B) Gel retardation assay showing the optimal N/P ratio for the complexation of siRNA with PEI and subsequent formation of LPP-siRNA. (C) Serum stability assay evaluating the protection of siRNA by LPP in the presence or absence of fetal bovine serum. (D) RNase A protection assay assessing the integrity of siRNA in LPP after RNase A treatment. (E) siRNA release assay under competitive ligand conditions (heparin). (F) Dynamic light scattering (DLS) analysis for size distribution, polydispersity index (PDI), and zeta potential of LPP-siRNA. (G) Zeta potential measurements of various formulations. (H) TEM images of LPP-siRNA nanoparticles. (I) Schematic representation of the cellular transfection of si-Cx43 and its subsequent inhibition of Cx43 expression. (J) Confocal microscopy images showing the internalization and endosomal escape of si-Cx43-NPs in REC cells. (K) qRT-PCR analysis of Cx43 mRNA levels after treatment with si-Cx43-NPs, naked si-Cx43 or si-Cx43 with Lipo2000 transfection. (L) Immunoblotting for Cx43 expression levels in REC cells treated with si-Cx43-NPs, naked si-Cx43 or si-Cx43 with Lipo2000 transfection. ∗∗p < 0.01, vs control; #p < 0.05 vs si-Cx43-NPs.

Next, Fig. 1I shows that si-Cx43 was transfected and Cx43 expression was inhibited within hRECs. Cellular uptake and endosomal escape efficiency were assessed in hRECs. Compared to the naked si-Cx43 group, 6-FAM-labeled si-Cx43-NPs demonstrated enhanced NP internalization rate, resulting in higher uptake efficiency of si-Cx43-NPs into the target cells (Fig. 1J). mRNA silencing efficiency was determined via qRT-PCR in hRECs. In comparison with control (naked si-Cx43), Cx43 mRNA levels were significantly reduced by si-Cx43-NPs treatment and regular transfection si-Cx43 mediated by Lipo 2000 (Fig. 1K). Notably, si-Cx43-NPs reduced mRNA levels as effectively as the Lipo2000-treated group (Fig. 1K). Consistently, in comparison with normal controls, Cx43 protein contents were remarkably downregulated within si-Cx43-NPs-treated and regularly transfected cells, with comparable reductions observed between si-Cx43-NPs treatment and regular transfection groups (Fig. 1L).

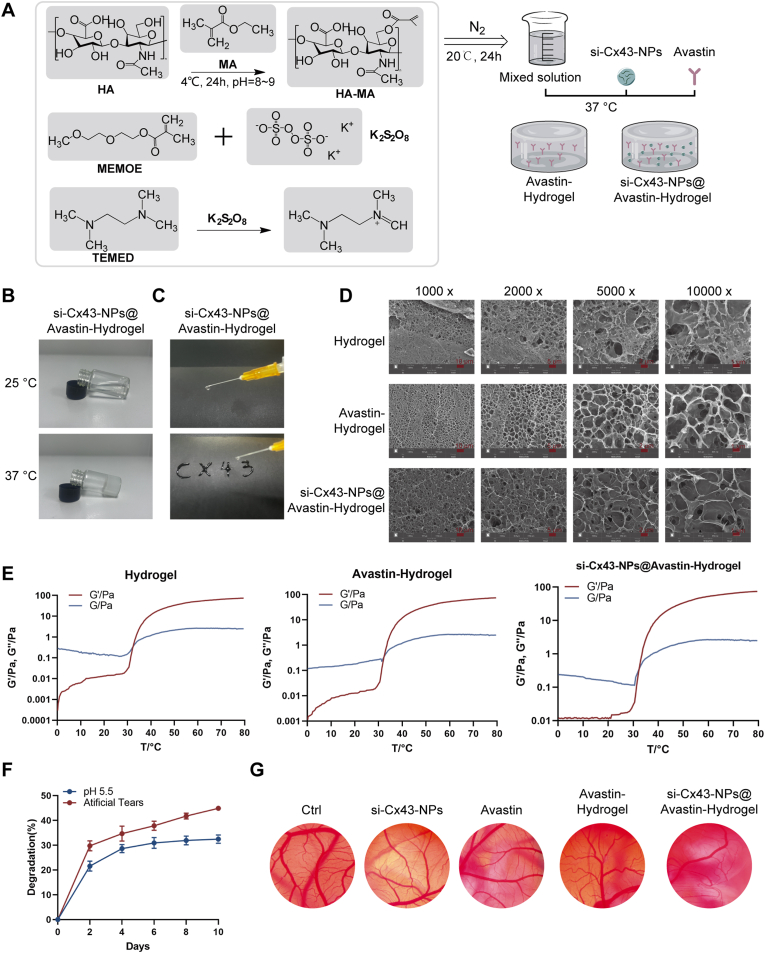

3.2. Preparation and characterization of si-Cx43-NPs@Avastin-hydrogel

Next, thermosensitive hydrogels loaded with single Avastin or si-Cx43-NPs and Avastin were prepared and characterized (Fig. 2A). The hydrogel demonstrated temperature-sensitive gelation, transitioning from a liquid at 25 °C into a gel at 37 °C (Fig. 2B). Injectability of the hydrogel was assessed to ensure the formulation's suitability for minimally invasive administration. Fig. 2C shows that si-Cx43-NPs@Avastin-hydrogel demonstrated excellent injectability through a standard syringe at room temperature without clogging or phase separation. Additionally, the hydrogel retained its stability during injection, as evidenced by its ability to maintain uniform flow, allowing for smooth and continuous extrusion. The hydrogel structure could also be maintained post-injection. SEM imaging revealed distinct porous structures, with si-Cx43-NPs@Avastin-hydrogel showing more homogeneous morphology compared to blank hydrogels (Fig. 2D). Rheological analysis showed that G' (storage modulus) and G'' (loss modulus) increased with temperature, with gelation occurring at approximately 35 °C (Fig. 2E). Degradation studies in artificial tears and citrate buffer (pH 5.5) indicated a gradual mass loss over time, demonstrating controlled degradation of the hydrogel (Fig. 2F). In the CAM assay, compared to the blank hydrogel group, si-Cx43-NPs@Avastin-hydrogel significantly reduced second- and third-order blood vessels, indicating superior anti-angiogenic activity (Fig. 2G). Compatibility with the ocular surface was also evaluated using the CAM assay; all hydrogel formulations were deemed non-irritating as they did not induce bleeding, vascular lysis, or CAM vessel coagulation within 5 min of application (Fig. 2G).

Fig. 2.

Preparation and characterization of si-Cx43-NPs@Avastin-hydrogel (A) Schematic illustration of hydrogel synthesis (Avastin-hydrogel and si-Cx43-NPs@Avastin-hydrogel). (B) Images showing hydrogel gelation at room temperature and 37 °C. (C) Evaluation of hydrogel injectability. (D) SEM images of hydrogel surface morphology. (E) Rheological analysis measuring storage modulus (G′) and loss modulus (G″) of hydrogels across a temperature gradient. (F) Degradation properties of hydrogels in artificial tear fluid and citrate buffer (pH 5.5). (G) CAM assay evaluating anti-angiogenic activity of si-Cx43-NPs, single Avastin, and hydrogels.

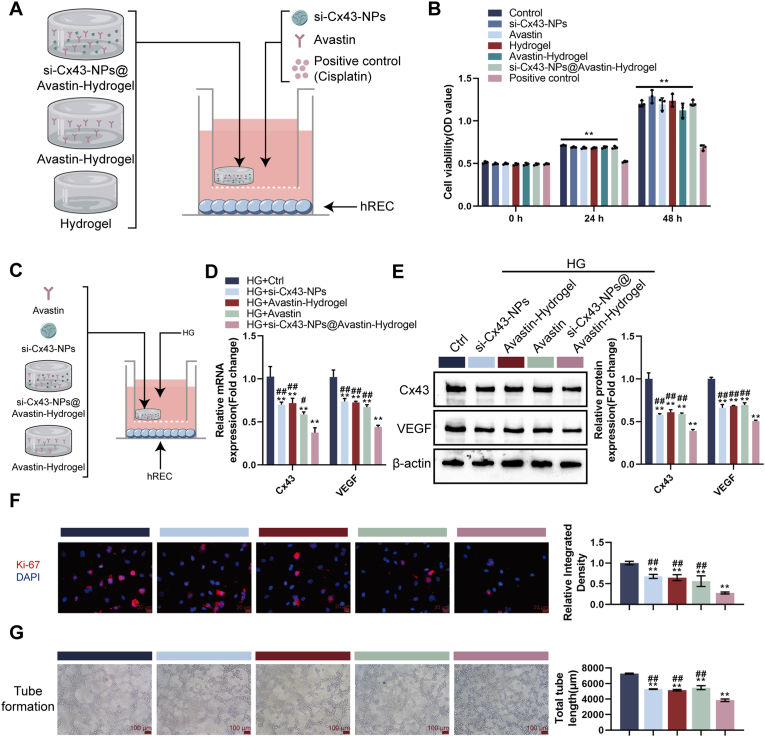

3.3. Cytotoxicity and anti-angiogenic effects of si-Cx43-NPs@Avastin-hydrogel in vitro

To evaluate the anti-angiogenic potential of the developed hydrogel system, we conducted both the chorioallantoic membrane (CAM) assay and the in vitro tube formation assay. The CAM assay allows for the assessment of the hydrogel's effects on blood vessel development in a complex biological environment [29,30], while the tube formation assay directly examines its impact on the behavior of retinal endothelial cells [31,32], which are key players in angiogenesis. To evaluate cytotoxicity of hydrogels, human RECs (hRECs) were first treated with single si-Cx43, single Avastin, non-loaded hydrogel, Avastin-hydrogel, si-Cx43-NPs@Avastin-hydrogel, or cisplatin (as positive control) (Fig. 3A). In the CCK-8 assay, compared to the control group, single si-Cx43-NPs, single Avastin, non-loaded hydrogel, Avastin-hydrogel, and si-Cx43-NPs@Avastin-hydrogel did not significantly reduce cell viability, indicating low cytotoxicity, whereas cisplatin significantly suppressed cell viability (Fig. 3B). To evaluate anti-angiogenic effects of hydrogels, hRECs were treated with single si-Cx43-NPs, single Avastin, or hydrogels under hyperglycemic (high glucose, HG) conditions (Fig. 3C). Under HG condition, single si-Cx43-NPs, single Avastin, Avastin-hydrogel, and si-Cx43-NPs@Avastin-hydrogel significantly decreased the expression of Cx43 and VEGF mRNA (Fig. 3D) and protein contents (Fig. 3E) in comparison with untreated hRECs, with si-Cx43-NPs@Avastin-hydrogel showing more profound effects compared to single si-Cx43-NPs, single Avastin, and Avastin-hydrogel groups (Fig. 3D and E). Regarding proliferation, single si-Cx43-NPs, single Avastin, Avastin-hydrogel, and si-Cx43-NPs@Avastin-hydrogel significantly decreased Ki67 levels in HG-stimulated hRECs compared to the control group, with si-Cx43-NPs@Avastin-hydrogel decreasing Ki67 more compared to single si-Cx43-NPs, single Avastin, and Avastin-hydrogel groups (Fig. 3F). Consistently, tube formation assays confirmed that single si-Cx43-NPs, single Avastin, Avastin-hydrogel, and si-Cx43-NPs@Avastin-hydrogel significantly inhibited angiogenesis compared to the untreated group, with si-Cx43-NPs@Avastin-hydrogel showing the most profound inhibitory effects compared to single si-Cx43-NPs, single Avastin, and Avastin-hydrogel groups (Fig. 3G).

Fig. 3.

Evaluation of si-Cx43-NPs@Avastin-hydrogel in hREC cells and its anti-angiogenic effects in vitro (A) Schematic illustration of cell experiments. (B) CCK-8 assay assessing cell viability after treatment with nanoparticles and hydrogels. (C) Schematic illustration of cell experiments under HG conditions. (D) qRT-PCR analysis of Cx43 and VEGF mRNA levels in hREC cells treated with nanoparticles or hydrogels under HG conditions. (E) Immunoblotting for Cx43 and VEGF protein levels in treated hREC cells. (F) Immunofluorescent staining (IF staining) detectsing Ki67 for cell proliferation. (G) Tube formation assay evaluating the anti-angiogenic effects of hydrogels in vitro. ∗∗p < 0.01, vs control; ##p < 0.01 vs si-Cx43-NPs@Avastin-hydrogel.

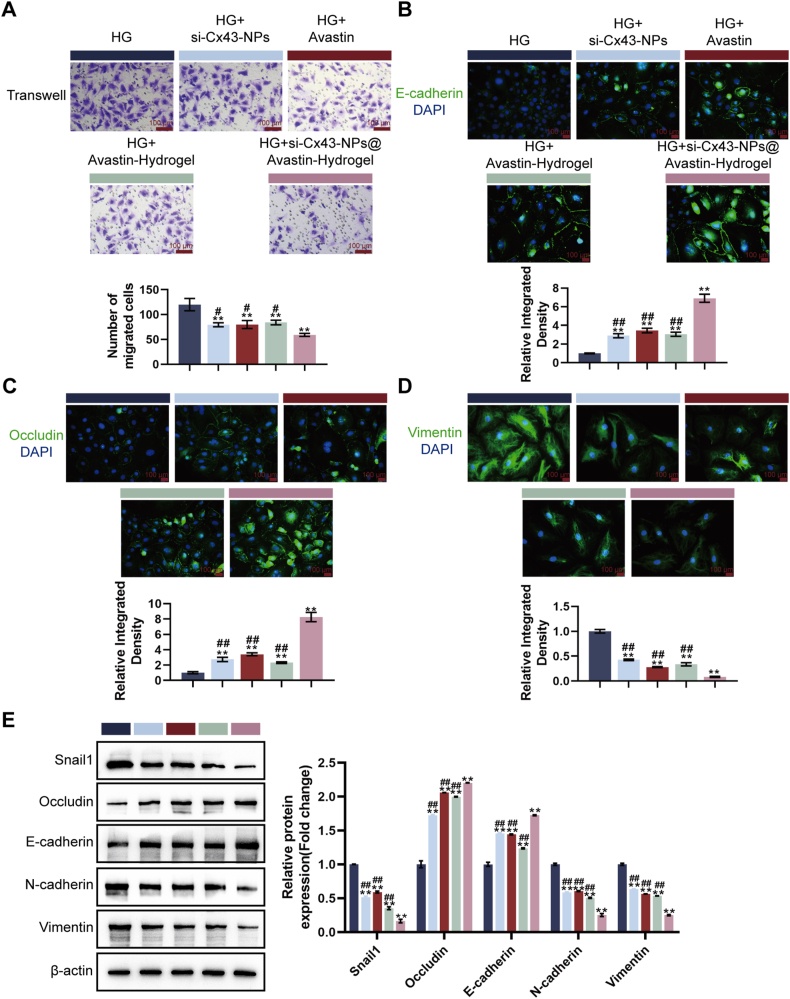

3.4. Regulation of cell permeability and migration by si-Cx43-NPs@Avastin-hydrogel in vitro

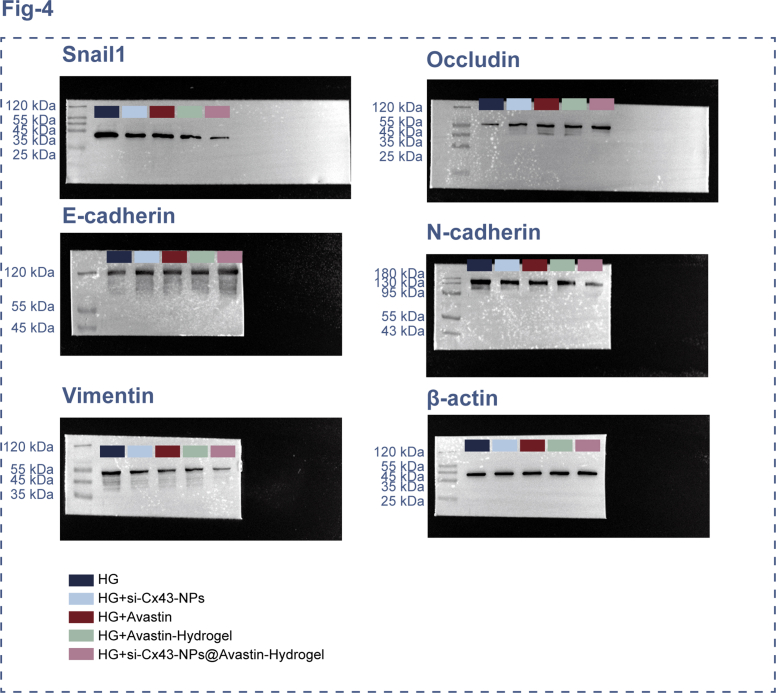

Next, the effects of hydrogels on hREC permeability and migration were examined under the same experimental conditions. A Transwell assay was employed to assess cell migration. Compared to the HG group, treatment with single si-Cx43-NPs, single Avastin, Avastin-hydrogel, and si-Cx43-NPs@Avastin-hydrogel significantly reduced the number of migrated cells, with si-Cx43-NPs@Avastin-hydrogel showing the greatest inhibitory effect compared to single si-Cx43-NPs, single Avastin, and Avastin-hydrogel groups (Fig. 4A). E-cadherin levels, representing cell-cell adhesion, were analyzed via IF staining. Compared to the HG group, treatment with single si-Cx43-NPs, single Avastin, Avastin-hydrogel, and si-Cx43-NPs@Avastin-hydrogel significantly increased E-cadherin levels, with si-Cx43-NPs@Avastin-hydrogel elevating E-cadherin levels more compared to the other treatments (Fig. 4B). Occludin levels, representing tight junction integrity, were also analyzed. Compared to the HG group, treatment with single si-Cx43-NPs, single Avastin, Avastin-hydrogel, and si-Cx43-NPs@Avastin-hydrogel significantly increased Occludin expression, with si-Cx43-NPs@Avastin-hydrogel showing higher levels compared to single si-Cx43-NPs, single Avastin, and Avastin-hydrogel groups (Fig. 4C). Vimentin levels, a marker of endothelial-mesenchymal transition (EndoMT), were analyzed by IF staining as well. Compared to the HG group, single si-Cx43-NPs, single Avastin, Avastin-hydrogel, and si-Cx43-NPs@Avastin-hydrogel significantly decreased Vimentin levels, with si-Cx43-NPs@Avastin-hydrogel showing the most profound decrease compared to single si-Cx43-NPs, single Avastin, and Avastin-hydrogel groups (Fig. 4D). Immunoblotting was employed to further analyze the protein contents of EndoMT markers. Compared to the HG group, single si-Cx43-NPs, single Avastin, Avastin-hydrogel, and si-Cx43-NPs@Avastin-hydrogel significantly decreased Snail1, N-cadherin, and Vimentin levels whereas elevating Occludin and E-cadherin levels, with si-Cx43-NPs@Avastin-hydrogel showing the greatest regulatory effects on all markers compared to single si-Cx43-NPs, single Avastin, and Avastin-hydrogel groups (Fig. 4E). These results demonstrate the superior ability of si-Cx43-NPs@Avastin-hydrogel to regulate cell permeability and suppress migration under hyperglycemic conditions.

Fig. 4.

Effect of hydrogels on HG-stimulated cell permeability and migration in vitro (A) Transwell assay for cell migration. (B–D) IF staining for E-cadherin, occludin, and vimentin levels in treated cells. (E) Immunoblotting for Snail1, occludin, E-cadherin, N-cadherin, and vimentin protein levels in treated cells. ∗∗p < 0.01, vs HG; ##p < 0.01 vs si-Cx43-NPs@Avastin-hydrogel.

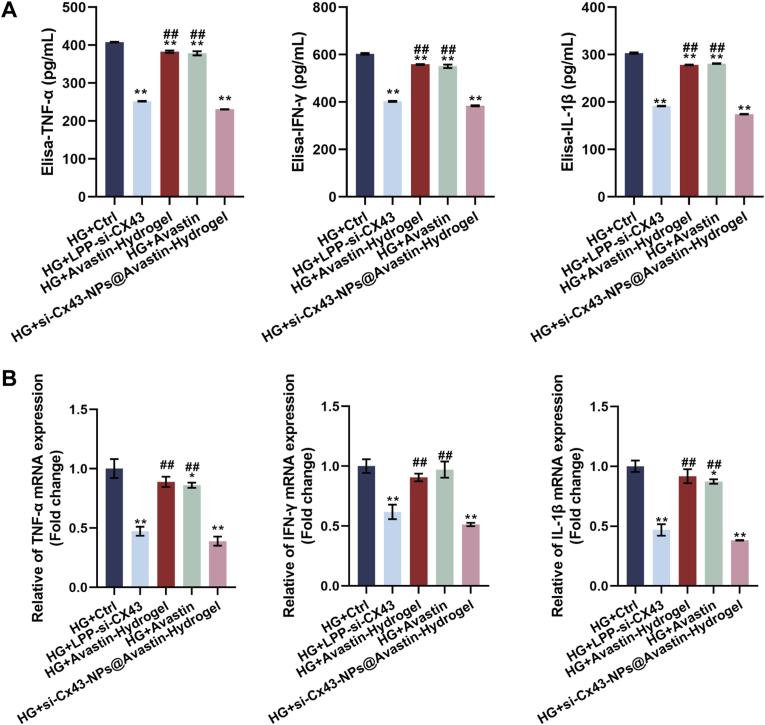

3.5. Anti-inflammatory effects of si-Cx43-NPs@Avastin-hydrogel in hRECs under hyperglycemic conditions

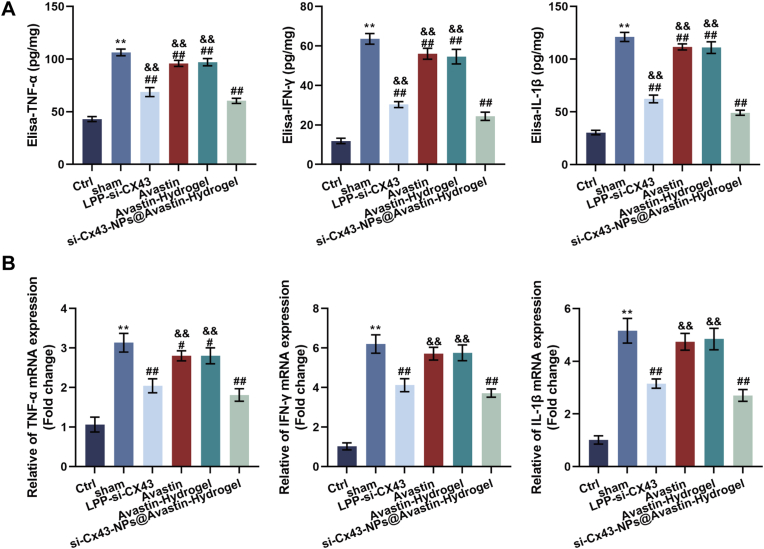

To evaluate the anti-inflammatory effects of si-Cx43-NPs@Avastin-hydrogel, the levels of inflammatory cytokines were measured in HG-treated hRECs lysates using ELISA. Compared to the HG group, single si-Cx43-NPs and si-Cx43-NPs@Avastin-hydrogel dramatically decreased TNF-α, IFN-γ, and IL-1β levels, whereas single Avastin and Avastin-hydrogel caused no obvious alterations in cytokine levels. Among these treatments, si-Cx43-NPs@Avastin-hydrogel exhibited the most pronounced reduction in cytokine levels compared to single si-Cx43-NPs, single Avastin, and Avastin-hydrogel groups (Fig. 5A). Consistently, qRT-PCR was employed to measure relative mRNA expression levels of inflammatory cytokines. Similar to the protein results, single si-Cx43-NPs and si-Cx43-NPs@Avastin-hydrogel significantly reduced TNF-α, IFN-γ, and IL-1β mRNA levels compared to the HG group, whereas single Avastin and Avastin-hydrogel did not change the mRNA expression of cytokines. si-Cx43-NPs@Avastin-hydrogel demonstrated the greatest inhibitory effect on cytokine mRNA levels compared to other treatments (Fig. 5B). These findings suggest that si-Cx43-NPs@Avastin-hydrogel effectively alleviates the inflammatory response in hRECs under hyperglycemic conditions, outperforming single si-Cx43-NPs.

Fig. 5.

Anti-inflammatory effects of si-Cx43-NPs@Avastin-hydrogel on REC cells (A) ELISA for TNF-α, IFN-γ, and IL-1β protein levels in REC cell homogenates. (B) qRT-PCR analysis of TNF-α, IFN-γ, and IL-1β mRNA levels in retinal homogenates. ∗∗p < 0.01, vs HG + control; ##p < 0.01 vs si-Cx43-NPs@Avastin-hydrogel.

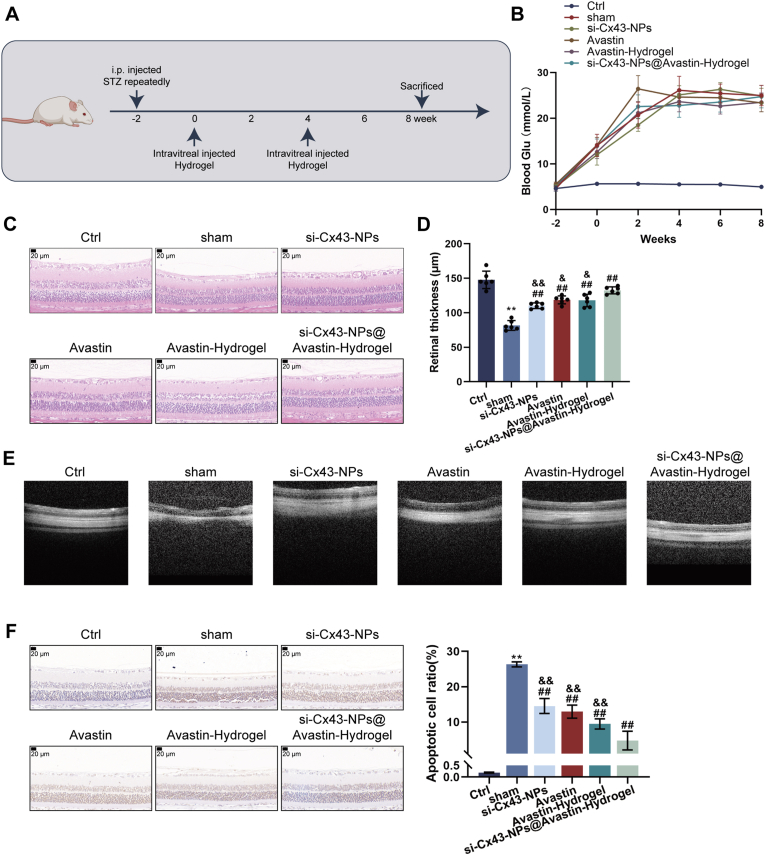

3.6. Effects of si-Cx43-NPs@Avastin-hydrogel on DR in vivo

After confirming the in vitro effects of hydrogels, a DR rat model was constructed and the therapeutic effects of single si-Cx43-NPs, single Avastin, Avastin-hydrogel, and si-Cx43-NPs@Avastin-hydrogel were evaluated over eight weeks (Fig. 6A). At the beginning of the first hydrogel injection and other treatments, the blood sugar values of rats in all modeling groups reached above 16.7, suggesting the successful establishment of the DR model. Besides, all treatments caused no significant alterations in rats’ blood sugar (Fig. 6B). Compared to the control group, retinal thickness and basement membrane thickness of model rats were drastically decreased in DR rats who received empty injection (sham group); compared to the sham group, single si-Cx43-NPs, single Avastin, Avastin-hydrogel, and si-Cx43-NPs@Avastin-hydrogel significantly increased retinal thickness and basement membrane thickness, with si-Cx43-NPs@Avastin-hydrogel showing the most profound effects, as revealed by H&E staining (Fig. 6C and D). OCT imaging demonstrated facilitated neovascularization and structural restoration within the sham group in comparison with normal controls; all treatment groups suppressed neovascularization compared to the sham group (DR), with si-Cx43-NPs@Avastin-hydrogel showing the best improvement compared to other treatment groups (Fig. 6E). As shown by TUNEL staining, cell apoptosis was significantly elevated within the sham DR rats in comparison with normal controls; all treatment groups significantly inhibited apoptosis, with si-Cx43-NPs@Avastin-hydrogel showing the most profound inhibitory effects on apoptosis in rats compared to other treatment groups (Fig. 6F).

Fig. 6.

Evaluation of si-Cx43-NPs@Avastin-hydrogel in a diabetic retinopathy (DR) rat model (A) Schematic illustration of the DR rat modeling and corresponding treatments. (B) Blood glucose levels of rats in different groups at weeks −2, 0, 2, 4, 6, 8 of the first intravitreal injection of hydrogels. (C) H&E staining of retinal tissue sections showing structural changes at the end of week 8. (D) Morphometric analysis of retinal and basement membrane thickness according to H&E staining. (E) Optical coherence tomography (OCT) images of retinal structure and neovascularization. (F) TUNEL staining for apoptosis in retinal tissues and quantitative analysis based on staining results. ∗∗p < 0.01, vs control; ##p < 0.01, vs sham, && p < 0.01 vs si-Cx43-NPs@Avastin-hydrogel.

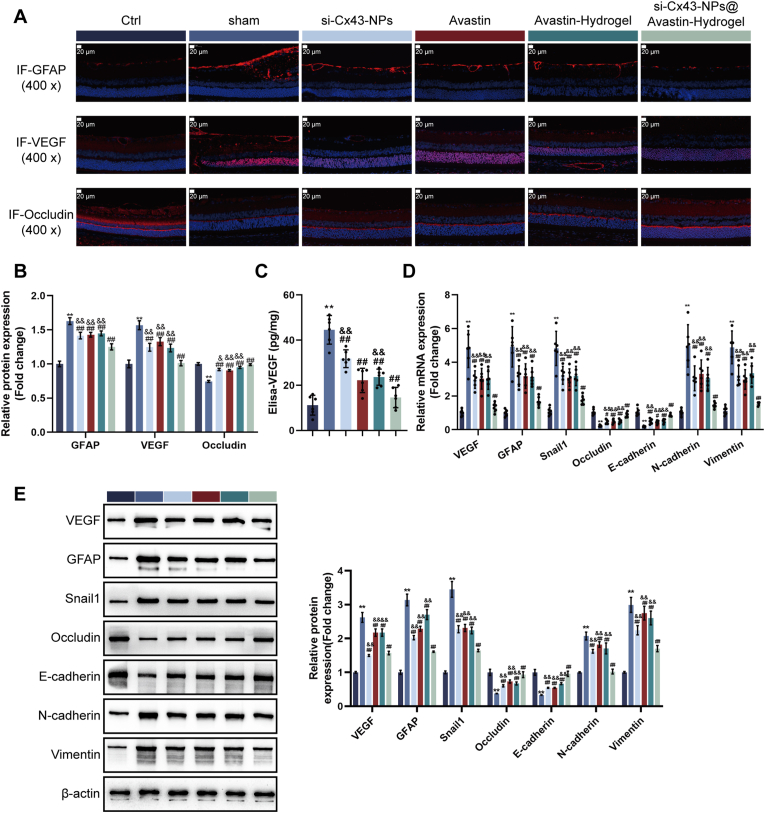

3.7. In vivo inhibition of angiogenesis and neuroprotection in the retina by si-Cx43-NPs@Avastin-hydrogel

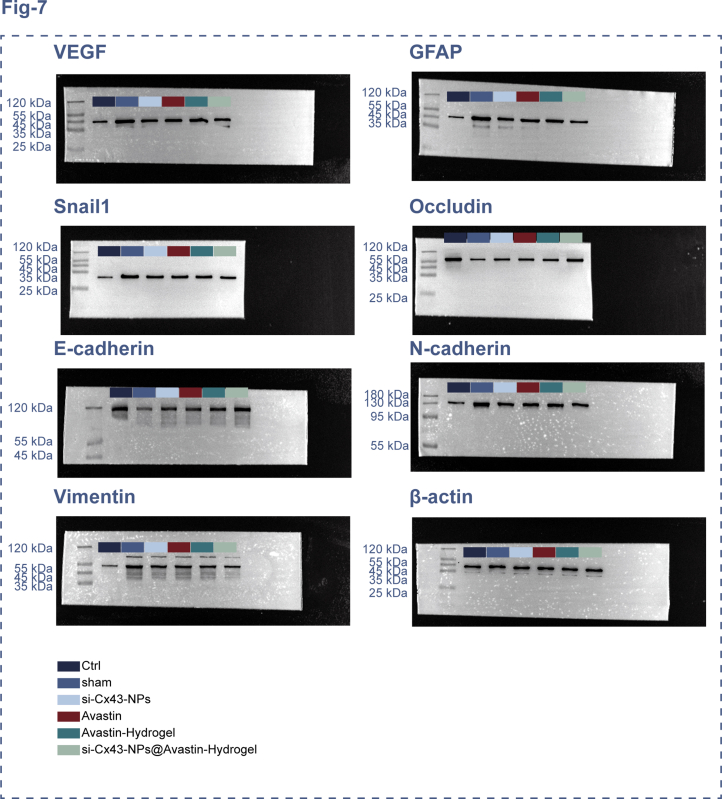

Next, the therapeutic effects of single si-Cx43-NPs, single Avastin, Avastin-hydrogel, and si-Cx43-NPs@Avastin-hydrogel on angiogenesis and neuroprotection were evaluated in DR rats. IF staining was conducted to assess GFAP, VEGF, and Occludin expression within retinal tissues. Compared to normal controls, DR rats in the sham group exhibited increased GFAP and VEGF levels and reduced Occludin levels, indicating neuroinflammation and vascular leakage. Treatment with single si-Cx43-NPs, single Avastin, Avastin-hydrogel, and si-Cx43-NPs@Avastin-hydrogel significantly reduced GFAP and VEGF levels and restored Occludin expression, with si-Cx43-NPs@Avastin-hydrogel showing the most profound effects compared to the other treatments (Fig. 7A and B). ELISA analysis of VEGF levels in retinal homogenates revealed significantly increased levels of VEGF within the sham rats in comparison with normal controls, consistent with neovascularization in DR. All treatment groups significantly reduced VEGF concentrations, with si-Cx43-NPs@Avastin-hydrogel demonstrating the most substantial reduction compared to single si-Cx43-NPs, single Avastin, and Avastin-hydrogel groups (Fig. 7C). As demonstrated by qRT-PCR, in comparison with normal controls, DR rats in the sham group exhibited upregulated VEGF, GFAP, Snail1, N-cadherin, and Vimentin mRNA levels, as well as downregulated Occludin and E-cadherin mRNA levels. All treatments reversed these changes, with si-Cx43-NPs@Avastin-hydrogel showing the most pronounced regulation compared to single si-Cx43-NPs, single Avastin, and Avastin-hydrogel groups (Fig. 7D). Protein expression analysis through Immunoblotting confirmed the qRT-PCR findings. Compared to the sham group, all treatment groups significantly decreased VEGF, GFAP, Snail1, N-cadherin, and Vimentin protein contents and increased Occludin and E-cadherin protein contents, with si-Cx43-NPs@Avastin-hydrogel demonstrating the strongest regulatory effects compared to the other groups (Fig. 7E). These findings highlight the ability of si-Cx43-NPs@Avastin-hydrogel to inhibit angiogenesis, reduce neuroinflammation, and protect retinal integrity, outperforming single si-Cx43-NPs, single Avastin, and Avastin-hydrogel in the DR rat model.

Fig. 7.

In vivo inhibition of angiogenesis and neuroprotection in the retina by si-Cx43-NPs@Avastin-hydrogel (A–B) IF staining for GFAP, VEGF, and occludin levels in rats' retinal sections. (C) ELISA for VEGF levels in rats' retinal tissues. (D) qRT-PCR analysis of VEGF, GFAP, occludin, Snail1, E-cadherin, N-cadherin, and vimentin mRNA levels in rats' retinal tissues. (E) Immunoblotting for VEGF, GFAP, occludin, Snail1, E-cadherin, N-cadherin, and vimentin protein levels in rats' retinal tissues. ∗∗p < 0.01, vs control; ##p < 0.01, vs sham, && p < 0.01 vs si-Cx43-NPs@Avastin-hydrogel.

3.8. Anti-inflammatory effects of si-Cx43-NPs@Avastin-hydrogel in vivo

Next, the anti-inflammatory effects of hydrogels were investigated in vivo. ELISA was employed to measure the protein contents of proinflammatory mediators within retinal lysates. In comparison with normal controls, the sham rats demonstrated dramatically elevated TNF-α, IFN-γ, and IL-1β levels, indicative of heightened inflammation. Single si-Cx43-NPs and si-Cx43-NPs@Avastin-hydrogel significantly reduced these cytokine levels, with si-Cx43-NPs@Avastin-hydrogel showing more profound effects compared to single si-Cx43-NPs. In contrast, single Avastin and Avastin-hydrogel treatments did not result in significant reductions in inflammatory cytokine levels compared to the sham group (Fig. 8A). Consistently, the sham DR group demonstrated remarkably elevated TNF-α, IFN-γ, and IL-1β mRNA expression compared to the control group. Single si-Cx43-NPs and si-Cx43-NPs@Avastin-hydrogel significantly downregulated the mRNA levels of these cytokines, with si-Cx43-NPs@Avastin-hydrogel showing a stronger reduction. Single Avastin and Avastin-hydrogel treatments exhibited minimal effects on cytokine mRNA expression in comparison with the sham group (Fig. 8B). In summary, si-Cx43-NPs@Avastin-hydrogel effectively reduces inflammation in the DR model, outperforming single si-Cx43-NPs.

Fig. 8.

Reduction of retinal inflammation by si-Cx43-NPs@Avastin-hydrogel in the DR rat model (A) ELISA for TNF-α, IFN-γ, and IL-1β levels in rats' retinal lysates. (B) qRT-PCR analysis of TNF-α, IFN-γ, and IL-1β mRNA levels in rats' retinal tissues. ∗∗p < 0.01, vs control; ##p < 0.01, vs sham, && p < 0.01 vs si-Cx43-NPs@Avastin-hydrogel.

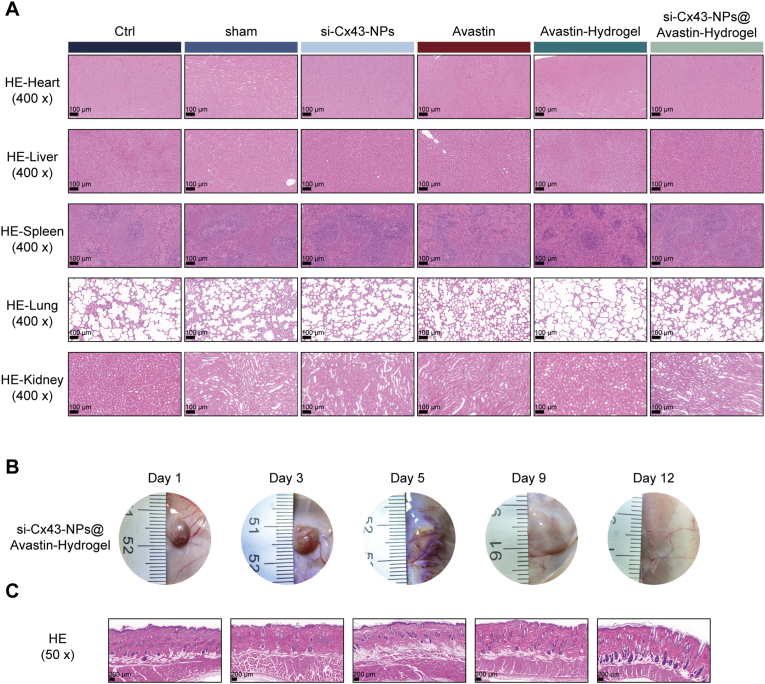

3.9. Biocompatibility and degradation of si-Cx43-NPs@Avastin-hydrogel

To assess biocompatibility, H&E staining was employed to analyze the main organs, such as heart, liver, spleen, lung, and kidney, at the end of in vivo experiments. In comparison with normal controls, no remarkable pathological alterations or toxicity were found in rats treated with single si-Cx43-NPs, single Avastin, Avastin-hydrogel, and si-Cx43-NPs@Avastin-hydrogel (Fig. 9A). Subcutaneously implanted hydrogels demonstrated gradual degradation, with extensive degradation of the hydrogel matrix observed on day 9 after injection and almost complete degradation on day 12 (Fig. 9B). No significant inflammation was observed in muscle tissues surrounding the injection points (Fig. 9C).

Fig. 9.

In vivo degradation and biocompatibility of hydrogels (A) H&E staining of rats' major organs: heart, liver, spleen, lungs, kidneys, for toxicity assessment at the end of the in vivo experiments. (B) Time-dependent degradation of hydrogels subcutaneously implanted in rats, with histopathological evaluation of dermal and muscle tissues. (C) Assessment of local inflammation and tissue compatibility in the surrounding muscle tissue by H&E staining.

4. Discussion

DR acts as a major cause of vision impairment, driven by pathological angiogenesis, inflammation, and retinal neurodegeneration, necessitating innovative treatment strategies to address these complex mechanisms. This study validated the hypothesis that si-Cx43-NPs@Avastin-hydrogel, a thermosensitive composite system, could effectively target these pathological processes through multimodal actions, including angiogenesis inhibition, inflammation suppression, and neuroprotection. The si-Cx43-NPs@Avastin-hydrogel demonstrated enhanced siRNA encapsulation, stability, and cellular uptake, effectively silencing Cx43 expression in hRECs. The hydrogel formulation provided excellent injectability, temperature-responsive gelation, and controlled degradation, outperforming single si-Cx43-NPs and Avastin in vitro by regulating cell permeability, suppressing migration, and inhibiting angiogenesis under hyperglycemic conditions. In vivo, si-Cx43-NPs@Avastin-hydrogel significantly reduced neovascularization, inflammation, and apoptosis while improving retinal morphology and neuroprotection in DR rats. Additionally, it exhibited excellent biocompatibility, with no significant toxicity or adverse effects in major organs, demonstrating its potential as a safe and effective therapeutic strategy for DR.

The delivery efficiency of ocular drugs is determined by the barriers and the clearance via the choroidal, conjunctival blood/lymphatic vessels. NPs have been developed to address the barriers, improve the penetration of drugs at the target area and extend the drug levels through several drug administration intervals in smaller dosages with no toxicity in comparison with the standard eye drops [33,34]. DNA NPs could enhance gene therapy transfection efficiency by providing high selectivity and multifunctionality [35]. For instance, US and/or MBs have been demonstrated to safely promote the NPs loading siRNA delivery into rat RPE cells [36]. In this study, si-Cx43 LPP (si-Cx43 NPs) demonstrated efficient siRNA encapsulation and stability against serum and RNase degradation, ensuring the preservation of functional siRNA for therapeutic action. Compared to regular transfection systems, LPP-siRNA exhibited enhanced comparable inhibition of Cx43 mRNA expression and protein levels, indicating ideal cellular uptake and effective Cx43 silencing in hRECs.

Building on these results, the study incorporated si-Cx43-NPs into a thermosensitive hydrogel loaded with Avastin to develop a synergistic delivery system. During the past decades, thermosensitive hydrogels have been regarded as persistent drug delivery carriers, biocompatible and non-toxic vitreous alternatives, shape-conformable implants and long-acting medicines compared to traditional therapies employed for treating diabetic eye disorders [25]. The thermosensitive hydrogel in this study was characterized for injectability, temperature-responsive gelation, and controlled degradation. These properties are critical for ocular applications, enabling minimally invasive administration and sustained drug release [[37], [38], [39]]. The porous structure of the hydrogel enhanced drug retention and stability, as evidenced by superior anti-angiogenic activity in the CAM assay compared to conventional systems. These properties enable the suitability of the thermosensitive hydrogel system for localized and sustained drug delivery, addressing limitations associated with frequent intravitreal injections in current DR therapies.

To evaluate therapeutic efficacy, in vitro studies assessed cytotoxicity to confirm biosecurity, as well as anti-angiogenic effects and inflammation regulation under hyperglycemic conditions, replicating the DR microenvironment. In cytotoxicity validation, si-Cx43-NPs, blank hydrogel, Avastin-hydrogel, and si-Cx43-NPs@Avastin-hydrogel demonstrated minimal cytotoxicity, confirming sufficient biosecurity towards hRECs. Upon hyperglycemia, platelets release pMVs, which results in angiogenesis, vascular impairment, inflammation and coagulation within the retina, contributing to DR progression [40]. As aforementioned, intravitreal administrations of anti-VEGF agents (e.g., bevacizumab) have shown clinical efficacy in reducing neovascularization and vascular leakage [8,9], whereas drugs targeting Cx43 hemichannels were proven to be underlying anti-inflammatory therapies [15,16]. In this study, all treatments significantly inhibited Cx43 and VEGF expression in HG-treated hRECs, with si-Cx43-NPs@Avastin-hydrogel showing the most profound inhibitory effects. In our previous study, Cx43 overexpression amplified the alteration caused by high glucose in hRECs, whereas Cx43 knockdown significantly improved retinal structure and decreased TNF-α, IL-1β, VEGFA, and ICAM-1 mRNA expression within a DR mouse model [17]. Herein, si-Cx43-NPs@Avastin-hydrogel significantly inhibited hREC proliferation and tube formation under HG conditions, consistent with the anti-angiogenic functions of Cx43 knockdown within DR mouse model.

Additionally, regulation of cell permeability and suppression of EndoMT markers, such as E-cadherin and Vimentin, highlighted its role in restoring retinal barrier integrity. REC cell EndoMT contributes to multiple retinal disorders, such as DR [41]. Within proliferative DR, high glucose could trigger REC cell EndoMT, resulting in neovascularization and fibrovascular membranes formation [42]. In this study, si-Cx43-NPs@Avastin-hydrogel exerted the most profound effects on these markers, suggesting the potential of si-Cx43-NPs@Avastin-hydrogel in improving HG-induced REC dysfunctions. EndoMT could be elicited via several mediators, such as transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) and TNF-α [43], which are frequently utilized to explore EndoMT in vitro. Beyond its role in vascular dysfunction and angiogenesis, Cx43 is increasingly recognized for its significant involvement in inflammatory processes, particularly in the context of diabetic complications [12]. Cx43 hemichannels, when open, can facilitate the release of inflammatory mediators such as ATP and prostaglandins, as well as the uptake of molecules that trigger inflammatory cascades [13,44]. Furthermore, Cx43 expression and activity have been linked to key inflammatory signaling pathways, including the TNF-α/NF-κB pathway, which plays a central role in the transcription of pro-inflammatory genes [45]. Silencing Cx43 with siRNA is thought to mitigate inflammation by reducing the activity of these hemichannels and potentially modulating downstream signaling events, thereby decreasing the production and release of pro-inflammatory cytokines like TNF-α, IFN-γ, and IL-1β [46], as observed in our study. Indeed, in HG-treated hREC, the observed anti-inflammatory effects, characterized by reduced TNF-α, IFN-γ, and IL-1β levels, further emphasized that the thermosensitive hydrogel system reinforces the effects of anti-VEGF and targeting Cx43 on hRECs by enhancing its anti-inflammatory and antiangiogenic activities.

Extending the findings to in vivo models, si-Cx43-NPs@Avastin-hydrogel exhibited robust therapeutic effects in DR rats. In DR, retinal structural damage can be caused by neovascularization, inflammation, and apoptosis, which collectively disrupt the retinal microarchitecture and compromise its functional integrity [47,48]. Here, retinal morphology alterations were restored by all treatments, especially si-Cx43-NPs@Avastin-hydrogel, suggesting that this formulation effectively mitigates structural damage and promotes tissue repair by simultaneously targeting pathological angiogenesis, inflammation, and apoptosis. Indeed, si-Cx43-NPs@Avastin-hydrogel showed the most profound effects on inhibiting neovascularization and reducing apoptosis, validating the hydrogel's efficacy in addressing structural and functional impairments in DR. Increased GFAP serves as a sensitive, nonspecific indicator of retinal stress or damage [49] within the retinas of diabetic rats [50,51]. Elevated GFAP suggests reactive gliosis and may be induced by hyperglycemia, oxidative stress, hypoxic conditions, or inflammatory response within diabetic retinas [52,53]. In DR rat models, si-Cx43-NPs@Avastin-hydrogel-induced inhibition of VEGF and GFAP expression, along with the restoration of occludin levels, further confirmed its angiogenic and neuroprotective effects. Further regulation of EndoMT markers, such as Snail1, E-cadherin, N-cadherin, and Vimentin, aligned with the hydrogel's impact on retinal barrier integrity and vascular health. These findings support the hypothesis that the combined targeting of VEGF and Cx43 confers superior therapeutic efficacy compared to existing treatments.

To ensure clinical translatability, the study assessed the biocompatibility and degradation of the hydrogels. No systemic toxicity or local inflammatory responses were observed, and the hydrogel exhibited gradual degradation over 12 days. Similarly, another HA-based hydrogel also exhibited similar in vivo degradation times [54]. Notably, our hydrogel avoided the localized inflammatory reactions commonly associated with similar thermogelling systems [55]. Compared to other hydrogel systems, si-Cx43-NPs@Avastin-hydrogel demonstrated comparable or superior safety and compatibility, further reinforcing its applicability in treating DR. The development of injectable and thermosensitive hydrogel systems has gained significant attention for localized drug delivery in various biomedical applications, offering advantages such as minimally invasive administration and sustained release profiles. Our findings align with other studies that have successfully utilized hydrogel platforms for diverse therapeutic purposes. For instance, injectable alginate-poloxamer/silk fibroin (ALG-POL/SF) dual network hydrogels, akin to the matrix used in our study, have been explored for controlled delivery of Insulin-like Growth Factor-1 (IGF-1) from incorporated bioactive glass nanoparticles for bone tissue engineering applications. This demonstrates the versatility of the ALG-POL/SF system in encapsulating and delivering different therapeutic molecules and nanoparticles [56]. Similarly, dual network ALG-POL/SF hydrogels incorporating hyaluronic acid complex nanoparticles loaded with Bone Morphogenic Protein-7 (BMP-7) have shown promise in inducing chondrogenic differentiation of stem cells for cartilage repair [57]. These studies, like ours, highlight the benefit of combining the properties of a thermosensitive hydrogel matrix with nanoparticle-based drug encapsulation to achieve controlled release kinetics and targeted therapeutic effects in tissue engineering contexts. Furthermore, the broader concept of utilizing injectable hydrogels as in-situ drug delivery platforms is well-established in other fields, such as the treatment of malignant tumors, where they enable increased drug concentration at the target site and reduced systemic side effects [58]. Our work extends the application of this versatile hydrogel platform and the strategy of nanoparticle incorporation to address the specific challenges of diabetic retinopathy treatment, leveraging the combined benefits for synergistic therapeutic outcomes targeting angiogenesis, inflammation, and neuroprotection.

Collectively, this study highlights si-Cx43-NPs@Avastin-hydrogel as a promising therapeutic system for DR, addressing angiogenesis, inflammation, and neuroprotection with minimal toxicity. The thorough evaluation of its stability, therapeutic efficacy, and biocompatibility provides a solid experimental basis for future optimization and clinical translation. Further studies should explore long-term therapeutic outcomes, dose optimization, and the integration of additional synergistic components to enhance efficacy. For successful clinical translation, evaluating the long-term storage stability and determining the shelf-life of the si-Cx43-NPs@Avastin-hydrogel formulation will be the crucial next steps. While not assessed in this initial study, these factors are critical for ensuring the quality and efficacy of the product over time and will be a focus of our future research.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Lihui Wen: Writing – original draft, Validation, Supervision, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Mengxin Gan: Validation, Resources, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation. Siying Xiong: Visualization, Resources, Methodology, Data curation. Li Dai: Resources, Methodology, Formal analysis. Wen Chen: Software, Resources, Methodology. Wen Shi: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Validation, Project administration, Methodology, Funding acquisition, Data curation, Conceptualization.

Ethics and consent to participate declarations

All the procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, Second Xiangya Hospital, Central South University (No.20230333).

Funding

This study was supported by the Health Research Project of Hunan Provincial Health Commission of China (No.20230806).

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgment

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mtbio.2025.101917.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

figs1.

figs2.

figs3.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- 1.Avogaro A., Fadini G.P. Microvascular complications in diabetes: a growing concern for cardiologists. Int. J. Cardiol. 2019;291:29–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2019.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bourne R.R.A., Jonas J.B., Bron A.M., Cicinelli M.V., Das A., Flaxman S.R., Friedman D.S., Keeffe J.E., Kempen J.H., Leasher J., Limburg H., Naidoo K., Pesudovs K., Peto T., Saadine J., Silvester A.J., Tahhan N., Taylor H.R., Varma R., Wong T.Y., Resnikoff S. Vision loss expert group of the global burden of disease S. Prevalence and causes of vision loss in high-income countries and in Eastern and central Europe in 2015: magnitude, temporal trends and projections. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2018;102:575–585. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2017-311258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miller D.J., Cascio M.A., Rosca M.G. Diabetic retinopathy: the role of mitochondria in the neural retina and microvascular disease. Antioxidants. 2020;9 doi: 10.3390/antiox9100905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gomulka K., Ruta M. The role of inflammation and therapeutic concepts in diabetic retinopathy-A short review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023;24 doi: 10.3390/ijms24021024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li Y., Liu Y., Liu S., Gao M., Wang W., Chen K., Huang L., Liu Y. Diabetic vascular diseases: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic strategies. Signal Transduct. Targeted Ther. 2023;8:152. doi: 10.1038/s41392-023-01400-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Antonetti D.A., Silva P.S., Stitt A.W. Current understanding of the molecular and cellular pathology of diabetic retinopathy. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2021;17:195–206. doi: 10.1038/s41574-020-00451-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lopes-Coelho F., Martins F., Pereira S.A., Serpa J. Anti-angiogenic therapy: current challenges and future perspectives. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021;22 doi: 10.3390/ijms22073765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ventrice P., Leporini C., Aloe J.F., Greco E., Leuzzi G., Marrazzo G., Scorcia G.B., Bruzzichesi D., Nicola V., Scorcia V. Anti-vascular endothelial growth factor drugs safety and efficacy in ophthalmic diseases. J. Pharmacol. Pharmacother. 2013;4:S38–S42. doi: 10.4103/0976-500X.120947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fogli S., Del Re M., Rofi E., Posarelli C., Figus M., Danesi R. Clinical pharmacology of intravitreal anti-VEGF drugs. Eye (Lond). 2018;32:1010–1020. doi: 10.1038/s41433-018-0021-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aiello L.P., Avery R.L., Arrigg P.G., Keyt B.A., Jampel H.D., Shah S.T., Pasquale L.R., Thieme H., Iwamoto M.A., Park J.E., et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor in ocular fluid of patients with diabetic retinopathy and other retinal disorders. N. Engl. J. Med. 1994;331:1480–1487. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199412013312203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cliff C.L., Williams B.M., Chadjichristos C.E., Mouritzen U., Squires P.E., Hills C.E. Connexin 43: a target for the treatment of inflammation in secondary complications of the kidney and eye in diabetes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022;23:600. doi: 10.3390/ijms23020600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roy S., Jiang J.X., Li A.F., Kim D. Connexin channel and its role in diabetic retinopathy. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2017;61:35–59. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2017.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van Campenhout R., Gomes A.R., De Groof T.W.M., Muyldermans S., Devoogdt N., Vinken M. Mechanisms underlying connexin hemichannel activation in disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021;22 doi: 10.3390/ijms22073503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Price G.W., Chadjichristos C.E., Kavvadas P., Tang S.C.W., Yiu W.H., Green C.R., Potter J.A., Siamantouras E., Squires P.E., Hills C.E. Blocking Connexin-43 mediated hemichannel activity protects against early tubular injury in experimental chronic kidney disease. Cell Commun. Signal. 2020;18:79. doi: 10.1186/s12964-020-00558-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Laird D.W., Lampe P.D. Therapeutic strategies targeting connexins. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2018;17:905–921. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2018.138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rhett J.M., Yeh E.S. The potential for connexin hemichannels to drive breast cancer progression through regulation of the inflammatory response. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018;19 doi: 10.3390/ijms19041043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shi W., Meng Z., Luo J. Connexin 43 (Cx43) regulates high-glucose-induced retinal endothelial cell angiogenesis and retinal neovascularization. Front. Endocrinol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fendo.2022.909207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rasier R., Artunay O., Yuzbasioglu E., Sengul A., Bahcecioglu H. The effect of intravitreal bevacizumab (avastin) administration on systemic hypertension. Eye (Lond). 2009;23:1714–1718. doi: 10.1038/eye.2008.360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sengul A., Rasier R., Ciftci C., Artunay O., Kockar A., Bahcecioglu H., Yuzbasioglu E. Short-term effects of intravitreal ranibizumab and bevacizumab administration on 24-h ambulatory blood pressure monitoring recordings in normotensive patients with age-related macular degeneration. Eye (Lond). 2017;31:677–683. doi: 10.1038/eye.2016.305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Farkouh A., Frigo P., Czejka M. Systemic side effects of eye drops: a pharmacokinetic perspective. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2016;10:2433–2441. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S118409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Falavarjani K.G., Nguyen Q.D. Adverse events and complications associated with intravitreal injection of anti-VEGF agents: a review of literature. Eye (Lond). 2013;27:787–794. doi: 10.1038/eye.2013.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang K., Han Z. Injectable hydrogels for ophthalmic applications. J. Contr. Release. 2017;268:212–224. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2017.10.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kang Derwent J.J., Mieler W.F. Thermoresponsive hydrogels as a new ocular drug delivery platform to the posterior segment of the eye. Trans. Am. Ophthalmol. Soc. 2008;106:206–213. ; discussion 13-4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gaudana R., Ananthula H.K., Parenky A., Mitra A.K. Ocular drug delivery. AAPS J. 2010;12:348–360. doi: 10.1208/s12248-010-9183-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ong N., Sim B., Chang J., Wong J., Loh X.J., Goh R. Recent advances in thermogels for the management of diabetic ocular complications. RSC Applied Polymers. 2023;1:204–228. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jeon H.Y., Moon C.H., Kim E.B., Sayyed N.D., Lee A.J., Ha K.S. Simultaneous attenuation of hyperglycemic memory-induced retinal, pulmonary, and glomerular dysfunctions by proinsulin C-peptide in diabetes. BMC Med. 2023;21:49. doi: 10.1186/s12916-023-02760-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li Q., Pang L., Shi H., Yang W., Liu X., Su G., Dong Y. High glucose concentration induces retinal endothelial cell apoptosis by activating p53 signaling pathway. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2018;11:2401–2407. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhou Y., Zhao C., Shi Z., Heger Z., Jing H., Shi Z., Dou Y., Wang S., Qiu Z., Li N. A glucose-responsive hydrogel inhibits primary and secondary BRB injury for retinal microenvironment remodeling in diabetic retinopathy. Adv. Sci. 2024;11 doi: 10.1002/advs.202402368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Duan N., Mei L., Hu L., Yin X., Wei X., Li Y., Li Q., Zhao G., Zhou Q., Du Z. Biomimetic, injectable, and self-healing hydrogels with sustained release of ranibizumab to treat retinal neovascularization. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2023;15:6371–6384. doi: 10.1021/acsami.2c17626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baek J.Y., Kwak J.E., Ahn M.R. Eriocitrin inhibits angiogenesis by targeting VEGFR2-mediated PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathways. Nutrients. 2024;16:1091. doi: 10.3390/nu16071091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim S.J., Lim J.S., Park J.H., Lee J. Molecular, cellular, and functional heterogeneity of retinal and choroidal endothelial cells. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2023;64:35. doi: 10.1167/iovs.64.10.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moon C.H., Lee A.J., Jeon H.Y., Kim E.B., Ha K.S. Therapeutic effect of ultra-long-lasting human C-peptide delivery against hyperglycemia-induced neovascularization in diabetic retinopathy. Theranostics. 2023;13:2424–2438. doi: 10.7150/thno.81714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhou H.Y., Hao J.L., Wang S., Zheng Y., Zhang W.S. Nanoparticles in the ocular drug delivery. Int. J. Ophthalmol. 2013;6:390–396. doi: 10.3980/j.issn.2222-3959.2013.03.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li S., Chen L., Fu Y. Nanotechnology-based ocular drug delivery systems: recent advances and future prospects. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2023;21:232. doi: 10.1186/s12951-023-01992-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tamboli V., Mishra G.P., Mitrat A.K. Polymeric vectors for ocular gene delivery. Ther. Deliv. 2011;2:523–536. doi: 10.4155/tde.11.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Du J., Shi Q.S., Sun Y., Liu P.F., Zhu M.J., Du L.F., Duan Y.R. Enhanced delivery of monomethoxypoly(ethylene glycol)-poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid)-poly l-lysine nanoparticles loading platelet-derived growth factor BB small interfering RNA by ultrasound and/or microbubbles to rat retinal pigment epithelium cells. J. Gene Med. 2011;13:312–323. doi: 10.1002/jgm.1574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Omar J., Ponsford D., Dreiss C.A., Lee T.C., Loh X.J. Supramolecular hydrogels: design strategies and contemporary biomedical applications. Chem. Asian J. 2022;17 doi: 10.1002/asia.202200081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Du X., Zhou J., Shi J., Xu B. Supramolecular hydrogelators and hydrogels: from soft matter to molecular biomaterials. Chem. Rev. 2015;115:13165–13307. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dreiss C.A. Hydrogel design strategies for drug delivery. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 2020;48:1–17. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang W., Chen S., Liu M.L. Pathogenic roles of microvesicles in diabetic retinopathy. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2018;39:1–11. doi: 10.1038/aps.2017.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nijim W., Moustafa M., Humble J., Al-Shabrawey M. Endothelial to mesenchymal cell transition in diabetic retinopathy: targets and therapeutics. Frontiers in ophthalmology. 2023;3 doi: 10.3389/fopht.2023.1230581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zou G., Que L., Liu Y., Lu Q. Interplay of endothelial-mesenchymal transition, inflammation, and autophagy in proliferative diabetic retinopathy pathogenesis. Heliyon. 2024;10 doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e25166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yoshimatsu Y., Kimuro S., Pauty J., Takagaki K., Nomiyama S., Inagawa A., Maeda K., Podyma-Inoue K.A., Kajiya K., Matsunaga Y.T., Watabe T. TGF-beta and TNF-alpha cooperatively induce mesenchymal transition of lymphatic endothelial cells via activation of Activin signals. PLoS One. 2020;15 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0232356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.De Vuyst E., Wang N., Decrock E., De Bock M., Vinken M., Van Moorhem M., Lai C., Culot M., Rogiers V., Cecchelli R., Naus C.C., Evans W.H., Leybaert L. Ca(2+) regulation of connexin 43 hemichannels in C6 glioma and glial cells. Cell Calcium. 2009;46:176–187. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2009.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Xu C.Y., Zhang W.S., Zhang H., Cao Y., Zhou H.Y. The role of connexin-43 in the inflammatory process: a new potential therapy to influence keratitis. J Ophthalmol. 2019;2019 doi: 10.1155/2019/9312827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Saez J.C., Contreras-Duarte S., Gomez G.I., Labra V.C., Santibanez C.A., Gajardo-Gomez R., Avendano B.C., Diaz E.F., Montero T.D., Velarde V., Orellana J.A. Connexin 43 hemichannel activity promoted by pro-inflammatory cytokines and high glucose alters endothelial cell function. Front. Immunol. 2018;9:1899. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Homme R.P., Singh M., Majumder A., George A.K., Nair K., Sandhu H.S., Tyagi N., Lominadze D., Tyagi S.C. Remodeling of retinal architecture in diabetic retinopathy: disruption of ocular physiology and visual functions by inflammatory gene products and pyroptosis. Front. Physiol. 2018;9:1268. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2018.01268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhou J., Chen B. Retinal cell damage in diabetic retinopathy. Cells. 2023;12:1342. doi: 10.3390/cells12091342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bringmann A., Wiedemann P. Muller glial cells in retinal disease. Ophthalmologica. 2012;227:1–19. doi: 10.1159/000328979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jung K.I., Kim J.H., Park H.Y., Park C.K. Neuroprotective effects of cilostazol on retinal ganglion cell damage in diabetic rats. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Therapeut. 2013;345:457–463. doi: 10.1124/jpet.113.203067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jung K.I., Woo J.E., Park C.K. Intraocular pressure fluctuation and neurodegeneration in the diabetic rat retina. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2020;177:3046–3059. doi: 10.1111/bph.15033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nian S., Lo A.C.Y., Mi Y., Ren K., Yang D. Neurovascular unit in diabetic retinopathy: pathophysiological roles and potential therapeutical targets. Eye Vis (Lond). 2021;8:15. doi: 10.1186/s40662-021-00239-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yang S., Zhang J., Chen L. The cells involved in the pathological process of diabetic retinopathy. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020;132 doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2020.110818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Galarraga J.H., Dhand A.P., Enzmann B.P., 3rd, Burdick J.A. Synthesis, characterization, and digital light processing of a hydrolytically degradable hyaluronic acid hydrogel. Biomacromolecules. 2023;24:413–425. doi: 10.1021/acs.biomac.2c01218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mazumder M.J., Fitzpatrick S.D., Muirhead B., Sheardown H. Cell‐adhesive thermogelling PNIPAAm/hyaluronic acid cell delivery hydrogels for potential application as minimally invasive retinal therapeutics. J. Biomed. Mater. Res., Part A. 2012;100:1877–1887. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.34021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]