Abstract

Hypoxia represents a common feature within the microenvironment of various cancerous tumors, which suppresses tumor immunogenicity. Immunotherapy, particularly based on immune checkpoint inhibitors, significantly alters the prognosis of certain tumors and reveals the presence of intrinsic or acquired resistance. Presently available platforms, however, cannot efficiently recapitulate the in vivo tumor microenvironment and elucidate the mechanisms of hypoxia-induced immunotherapy resistance in tumors. In this study, a microfluidic tumor-on-chip model is employed to investigate immunotherapy resistance in gastric cancer (GC) cells within a hypoxic microenvironment. Unlike traditional methods, this chip accurately and efficiently replicates the in vivo tumor hypoxic microenvironment. This microfluidic platform demonstrates the upregulation of the forkhead box O3 (FOXO3a) under hypoxic conditions, subsequently activating downstream programmed cell death ligand-1 (PD-L1) expression, ultimately leading to immunotherapy resistance. In a syngeneic mouse model, FOXO3a deficiency restores sensitivity to immunotherapy by enhancing immune cell enrichment. In clinical samples, FOXO3a levels and the prognosis of patients with gastric cancer receiving immunotherapy are correlated. In summary, by constructing a novel microfluidic chip, the in vivo tumor microenvironment can be efficiently simulated, uncovering the pivotal role of FOXO3a in immunotherapy resistance in gastric cancer.

Keywords: Hypoxia, Microfluidic chip, Immunotherapy resistance, Gastric cancer, FOXO3a

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Gastric cancer (GC) persists as one of the principal contributors to global cancer-related mortality [1]. Despite therapeutic advancements in surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy, the prognosis for patients with advanced-stage GC remains poor [[2], [3], [4]]. Recent advances in immunotherapy, particularly immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) targeting programmed cell death-1(PD-1)/programmed cell death ligand-1 (PD-L1), have emerged as a promising therapeutic strategy, offering renewed hope for improving patient outcomes [5]. However, the benefits of immunotherapy are not universal with only 20 % of patients exhibiting objective responses to immunotherapy [6].

In this context, emerging evidence demonstrates that tumor-associated environmental stressors such as hypoxia, nutrient deprivation, and pH acidification actively suppress antitumor immunity [[7], [8], [9]]. Hypoxic regions are pervasively established within GC tissues due to rapid tumor cell proliferation and insufficient vascular oxygen supply [10]. Clinically, tumor hypoxia correlates with increased risks of invasion, metastasis, and poor prognosis in GC patients [[11], [12], [13]]. At the molecular level, hypoxia drives genetic and adaptive changes in cancer cells, enabling survival and aggressive growth in hypoxic environments [14]. Consequently, deciphering how hypoxia shapes the tumor microenvironment (TME) is critical for developing more effective immunotherapy strategies Nevertheless, conventional two-dimensional (2D) models have proven inadequate in recapitulating the spatial and biochemical complexity of solid tumor ecosystems [15].

In this context, microfluidic technologies and organ-on-a-chip models hold significant potential to recapitulate features of the TME while enabling real-time monitoring of tumor-immune cell interactions and their evolutionary dynamics [16,17]. Recent studies have reported microfluidic organ-on-chips capable of generating hypoxic environments in vitro to mimic physiological dissolved oxygen (DO) gradients observed in vivo. However, these existing models exhibit some limitations. For example, planar-cultured cells fail to replicate the authentic 3D cellular growth patterns of solid tumors [18]; oxygen concentrations within organ-on-chip chambers cannot be precisely controlled or monitored [19]; and current systems lack the capability to establish precisely controlled hypoxic conditions for investigating hypoxia-driven molecular signaling cascades and immune-tumor cell interactions [20]. These constraints underscore the urgent need for a microfluidic platform with spatiotemporally resolved oxygen control to dissect hypoxia-mediated mechanisms of immunotherapy resistance in cancer.

In this study, we developed a tumor-on-chip platform capable of precisely regulating DO concentrations within distinct 3D cell culture chambers to model GC organoids. GC cells were embedded in a 3D extracellular matrix, while endothelial cells lining the microchamber openings and perfused culture medium simulated the tumor-associated vascular system. This design enabled biomimetic replication of nutrient gradients, pH fluctuations, proliferative zones, and necrotic regions characteristic of solid tumors. Our results demonstrate that hypoxia upregulates Forkhead box class O3a (FOXO3a) expression in GC cells, induces its nuclear translocation, and subsequently activates PD-L1 expression, ultimately driving immunosuppression within the TME. We believe that the oxygen-controllable microfluidic platform provides a robust tool for investigating hypoxia-induced immune evasion mechanisms and evaluating therapeutic efficacy of hypoxia-targeted anticancer agents.

2. Results

2.1. Hypoxia is associated with immune escape in GC

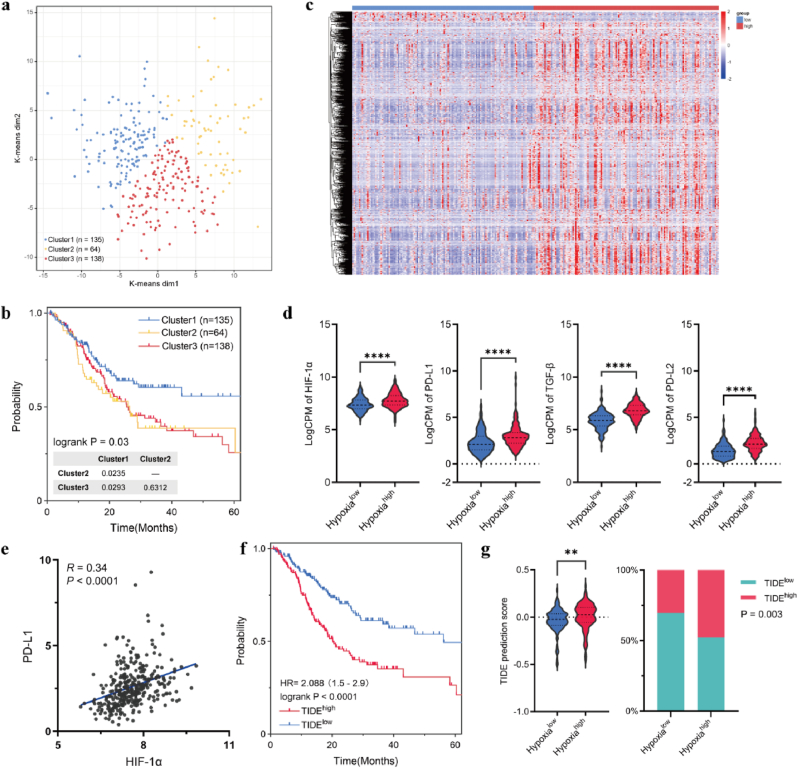

To investigate the role of hypoxia in immune regulation in GC, we initially examined the relationship between the expression of hypoxia signature genes in GC and the activity of anti-tumor immune genes. To this end, RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) data and the associated clinical data, including tumor stage and overall survival times, from The Cancer Genome Atlas stomach cancer (TCGA-STAD) dataset were analyzed. The cohort comprised 337 patients with GC, whose clinicopathological characteristics are listed in Supplementary Table S1. Analysis of a matrix of 200 hypoxia signature genes downloaded from the Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB) defined three patient clusters (Fig. 1a): Cluster 1 (n = 135 patients), Cluster 2 (n = 64 patients), and Cluster 3 (n = 138 patients). Kaplan–Meier analysis demonstrated significant differences among these three patient clusters, with patients in Cluster 3 exhibiting a poorer disease prognosis compared with those in Cluster 1 (Fig. 1b). This indicated that patients in Cluster 1 and Cluster 3 might have been in the lowest and highest hypoxic states. Accordingly, patients from Cluster 1 and Cluster 3 were categorized as the “hypoxialow” group and the “hypoxiahigh” group, respectively. The expression profiles of hypoxiahigh and hypoxialow groups were also compared, which identified 953 hypoxia-related differentially expressed genes (DEGs), 917 (96.2 %) of which exhibited increased expression in the hypoxiahigh group (Fig. 1c). As common genes in tumor immune escape, the expression levels of HIF1A, PDL1, and TGFB (encoding transforming growth factor β) were further analyzed. These three genes showed significantly higher expression in the hypoxiahigh group than in the hypoxialow group (Fig. 1d). Correlation analysis also suggested that PDL1 and HIF1A were positively correlated (Fig. 1e).

Fig. 1.

Hypoxia is associated with immune escape in GC. a Dot plot of the three clusters identified using the K-means algorithm based on 200 hypoxia signature genes. b Kaplan–Meier plot for the overall survival of the patients in the three clusters. c Heatmap of the expression profiles of hypoxia-associated DEGs from the comparison between the hypoxiahigh and hypoxialow groups. d Violin plots showing the upregulation of hypoxia and immune-related markers in GC under hypoxic microenvironment. e Pearson's correlation between the expression levels of PDL1 and HIF1A in patients with GC in the hypoxiahigh and hypoxialow groups. f Kaplan–Meier plot for the overall survival of patients in the TIDEhigh and TIDElow groups. g Violin plot displaying the difference in the TIDE scores between the hypoxiahigh and hypoxialow groups. Stacked bar chart indicating the proportion of patients with TIDEhigh and TIDElow in the hypoxiahigh and hypoxialow groups. Values represent the mean ± standard deviation (SD). ∗∗p < 0.01; ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001.

To delve deeper into the relationship between hypoxia and immunotherapy, Tumor Immune Dysfunction and Exclusion (TIDE) analysis was employed to estimate the TIDE score and the predictive potential for tumor immune escape in the gene expression profiles of tumor samples [21]. According to the analysis of survival, a high TIDE score was associated with poorer patient prognosis compared with those with lower TIDE scores (Fig. 1f). Notably, patients categorized within the hypoxialow group demonstrated lower TIDE scores in comparison to their counterparts in the hypoxiahigh group, which suggested a more promising response to immunotherapy (Fig. 1g). Together, these findings support the role of hypoxia in immune escape in GC and its association with poorer disease outcomes.

2.2. Establishment of the tumor-on-chip model

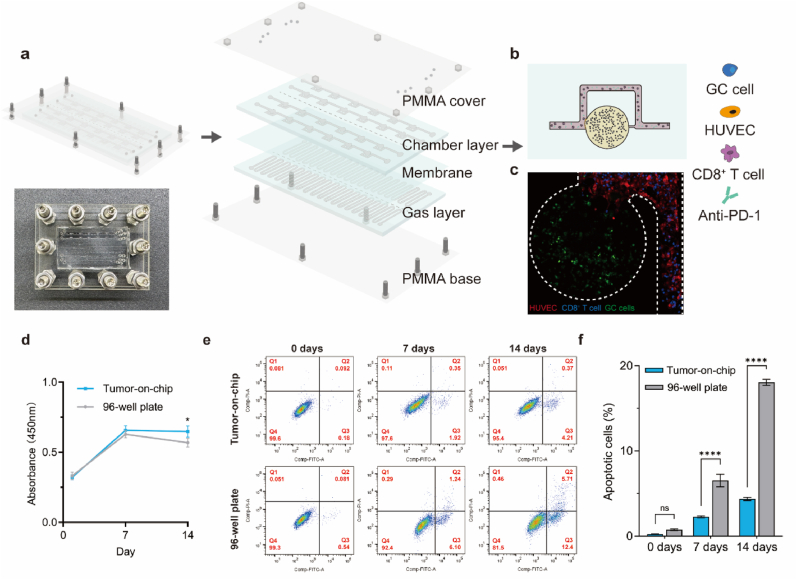

Insufficient blood supply or hypoxia represents a typical characteristic of the TME of nearly all solid tumors [22]. To evaluate the immune escape of tumor cells and their resistance to ICB therapy in a hypoxic microenvironment, a novel microfluidic tumor-on-chip model was developed (Fig. 2a). This model comprises several 3D cell culture microchambers in which GC cells were embedded within extracellular matrix gel (Fig. 2b). After polymerization of the extracellular matrix gel, human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) were lined along the inner walls of the microchannel, extending into the openings of the microchambers. Perfusion culture medium was then flowed through to substitute for vascular nourishment of the cells. In addition, the entire device was connected to the Fluigent microfluidic flow control system to monitor the fluid flow rate. Finally, gases at different oxygen levels were perfused through the gas layer channel, then diffuse through the permeability of polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) membrane, determining the oxygen levels to which the cells in the chamber layer were exposed.

Fig. 2.

Microfluidic Tumor-on-chip model. a Overall schematic diagram (top left) and physical image (bottom left)image of the microfluidic tumor-on-chip model. Layer-by-layer schematic diagrams of chip were shown right. b Schematic diagram of the chamber layer. In the the microchamber, GC cells were embedded within extracellular matrix gel while HUVECs were arranged at the opening of the microchamber. CD8+ T cells were perfused with anti-PD-1 antibody in the microchannels. c Confocal images showing the spatial distribution of the cells inside the tumor-on-chip model. AGS cells (green) were embedded within the extracellular matrix gel, while CD8+ T cells (blue) and HUVEC cells (red) were encapsulated within the microchannels. d The proliferative capacity of GC cells in the tumor-on-chip model and traditional 96-well plate at 1 day, 7 days, and 14 days, as assessed using CCK-8 assays. e and f Flow cytometry analysis of the cell apoptosis rate in GC cells grown on the tumor-on-chip model and traditional 96-well plates at 0 days, 7 days, and 14 days. Values represent the mean ± SD. ∗p < 0.05; ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001; ns, no significance. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

The PDMS meant that the DO concentration within the microchannels and microchambers inside the chamber layer will eventually equilibrate to the pO2 of the gas in the gas layer channel. To ascertain the actual DO concentration within the chip, a DO probe was used to measure the real-time DO concentration inside the corresponding microchambers (Fig. S1a). The results showed that after the gas perfusion was initiated, the DO concentration in the microchambers corresponding to the hypoxic gas layer rapidly decreased, dropping from 20.9 % to 15 % within 10 min. Subsequently, the decrease in DO concentration gradually slowed, stabilizing at 1 % after 2 h in the incubator. In contrast, the DO concentration in the microchambers corresponding to the normoxic gas layer remained stable at 21 %. We further validated oxygen levels using the fluorescent hypoxia probe BioTracker 520 Green Hypoxia Dye. In 2D-cultured cells, BioTracker signal intensity increased progressively as oxygen tension decreased, peaking under 1 % O2. These observations aligned with parallel oxygen sensor measurements, confirming that hypoxic chamber oxygen concentrations reached minimal levels within 2 h (Fig. S1b and c).

The composition of tumors is exceedingly intricate, comprising blood vessels, lymphatic vessels, extracellular matrix, fibroblasts, immune cells, and cancer cells [23]. To assess the platform's potential to in study tumor immunotherapy, CD8+ T cells, which retain their cytotoxicity in vitro and in vivo, and which have undergone extensive clinical testing, were used [24]. The CD8+ T cells were mixed within the culture medium and flowed through the microchannels coated with HUVECs, mimicking the circulation of immune cells within blood vessels (Fig. 2c). The 3D co-culture of GC cells with immune cells on the microfluidic chip with vascular functionality better represents the authentic cancer microenvironment compared with traditional 3D-cultured GC cells. To further validate the ability of the tumor-on-chip model to replicate the in vivo immune microenvironment, we compared the infiltration rate of CD8+ T cells between the tumor-on-chip model and syngeneic mouse tumor model on day 0 and day 7 (Fig. S1d). Additionally, we further examined the expression of interferon gamma (IFN-γ) and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) on CD8+ T cells (Fig. S1e). The results demonstrated that the tumor-on-chip model has a good capacity to replicate the immune microenvironment.

Ideally, the culture time should be extended to allow for the study of treatment responses that require incubation periods exceeding one week. A primary constraint observed in ex vivo culture was the finite period during which optimal proliferative capacity could be maintained. Therefore, we only cultured GC cells in the tumor-on-chip model under hypoxic conditions and extended the culture time to 14 days. In parallel, under hypoxic conditions identical to the tumor-on-chip model, GC cells were cultured in a 3D matrix gel in a traditional 96-well plate. Following 7 days of culture, the cellular proliferation rate in the tumor-on-chip model was similar to that day 1, while the cells cultured in the 96-well plate exhibited slightly slower proliferation (29.63 % vs. 33.67 %; Fig. 2d). Staining using annexin V-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)/propidium iodide (PI) indicated a slightly higher cell apoptosis rate in the 96-well plate on the 7th day compared with that in the tumor-on-chip model (6.53 % vs. 2.27 %; Fig. 2e and f). This pattern became more pronounced when the culture time was extended to 14 days, indicating that the tumor-on-chip model better preserved cell proliferation than the traditional in vitro culture system. At 14 days, the cellular proliferation rate in the tumor-on-chip model was significantly higher than in the 96-well plate (32.63 % vs. 23.53 %; Fig. 2e and f). Additionally, the apoptosis rate of cells in the traditional 96-well plate was 18.06 %, while on the tumor-on-chip platform, it was only 4.37 % (p < 0.0001). Further analysis of cell apoptosis rates demonstrated that, compared with that in the tumor-on-chip model, the traditional 96-well plate 3D culture method exhibited a notable increase in late apoptotic cells by the 7th day of culture, which was further amplified by the 14th day (Fig. S1f). In contrast, in the tumor-on-chip model, there was minimal change in the cellular proliferation rate between day 0 (32.17 %) and day 14 (32.63 %). Together, the tumor-on-chip model provides improved conditions for extended (up to 14 days) tumor cell culture compared with traditional in vitro culture systems. Even after 7 days, subtle differences might already exist between the two culture methods.

To further validate the functional role of CD8+ T cells within the microfluidic chip model, we perfused CD8+ T cells into microchannels and systematically assessed GC cell viability (Fig. S2a). CD8+ T cells retained cytotoxic activity under both normoxic and hypoxic conditions. However, tumor cell apoptosis rates were significantly reduced in hypoxic environments compared to normoxia, indicative of diminished CD8+ T cell killing capacity. Subsequent functional assays evaluating CD8+ T cell cytotoxicity and activation markers revealed broad suppression of effector functions under hypoxia (Fig. S2b). These findings collectively suggest the existence of an inhibitory pathway governing GC cell-CD8+ T cell interactions in oxygen-deprived microenvironments.

2.3. Hypoxia suppresses immune effector gene expression in GC cells

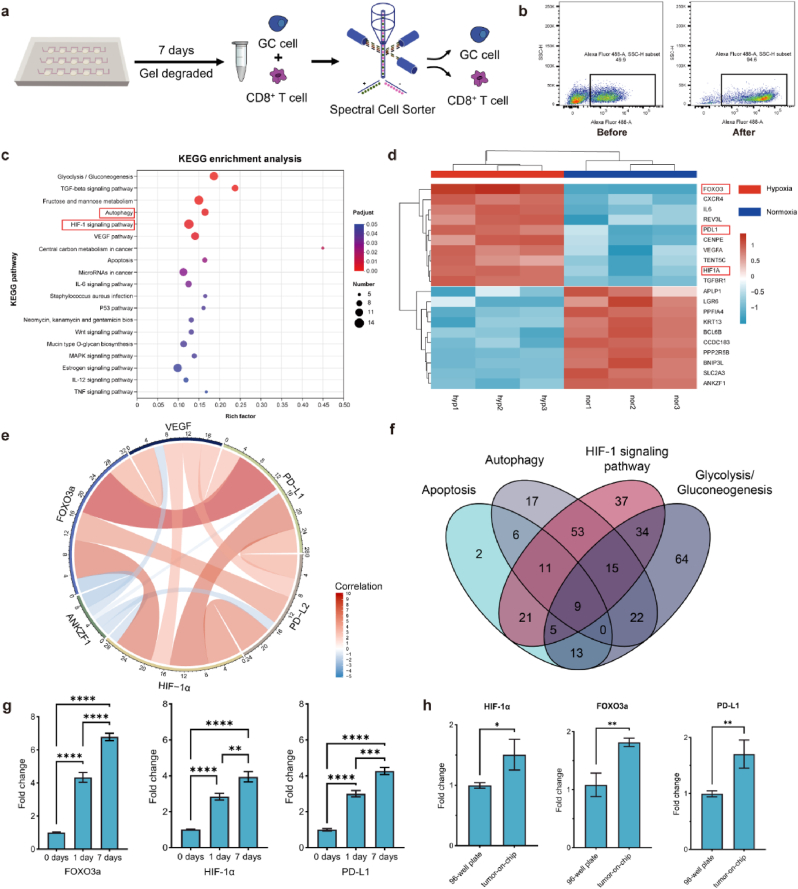

To isolate GC cells separately from the co-culture system, following culture for 7 days, the matrix gel was degraded and CD8+ T cells were selectively removed from the cell suspension, effectively isolating the GC cells (Fig. 3a and b). Subsequently, the molecular changes induced by hypoxia on AGS cells in the tumor-on-chip model were investigated using RNA-seq. According to the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway analysis, the HIF-1α, VEGF, and autophagy pathways were enriched, which are closely associated with a hypoxic TME and immune escape (Fig. 3c) [[25], [26], [27]]. Nonhierarchical clustergram analysis demonstrated a profound alteration in gene expression in GC cells after 7 days in the microfluidic chip under 1 % pO2 relative to that in the control group (Fig. 3d). In the comparison between the hypoxic group and the normoxic group 1167 DEGs were identified (799 DEGs were upregulated and 368 were downregulated according to the criteria of fold change ≥1.5 and P-value <0.05). The bioinformatic analysis results showed upregulation of several hypoxia and immune dysfunction-related genes (e.g., HIF1A and PDL1). Furthermore, the upregulated genes also included those associated with nutrient deprivation and angiogenesis (e.g., VEGF (encoding vascular endothelial growth factor)), indicating that GC cells were under stress and had activated multiple adaptive responses. In further analysis, we identified a significant upregulation of FOXO3A under hypoxic conditions. Furthermore, by analyzing the expression levels of DEGs, we observed a significant positive correlation between FOXO3A and PDL1 at the gene level (Fig. 3e). We further queried the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database, and correlation analyses in hypoxia-associated gastric cancer cohorts revealed a statistically significant positive relationship between FOXO3a and PD-L1 expression (Fig. 2c). A novel group of transferases has been identified to play roles in AGS cells within the hypoxic TME. Nine genes, including FOXO3A, were found to overlap in the HIF-1α, VEGF, autophagy and TGF-β signaling pathways (Fig. 3f). Quantitative real-time reverse transcription PCR (RT-qPCR) was used to validate several DEGs that exhibited pronounced regulation in MKN-45, HGC-27 and MGC-803 cells (Fig. 3g and Fig. S2d–f). The results indicated that FOXO3A exhibited the most significant upregulation in hypoxic GC cells, followed by HIF1A and PDL1, suggesting immune suppression within the hypoxic TME. Further investigation into different periods of hypoxic incubation revealed that these alterations in gene expression levels were manifested as early as 24 h of hypoxia, which intensified significantly after 7 days. These results indicated that the upregulation of FOXO3A expression might be associated with immune escape of GC cells.

Fig. 3.

Hypoxia induced the expression of immunosuppressive genes in GC cells. a Schematic diagram of GC cell separation. After culturing GC cells in the matrix gel for 7 days, the gel was degraded, and the separation was conducted via FACS. b Flow cytometry analysis showing two distinct clusters of GC cells and CD8+ T cells before sorting. Following sorting, only AGS cells were present. c KEGG enrichment analysis indicating the pathways enriched for DEGs in AGS cells under a hypoxic TME. d Heatmap of 799 DEGs (fold change ≥1.5 and P value <0.05 in any pairwise comparison) under hypoxia versus normoxic environments. e Correlation analysis revealing the interrelationships among various DEGs in AGS cells under a hypoxic TME. f Venn diagram illustrating the overlapping genes within the signaling pathways of AGS cells under a hypoxic TME. g Experssion level of FOXO3A, HIF1A, and PDL1 in MKN-45. h Comparison of gene expression in AGS cells cultured in traditional 96-well plate versus the tumor-on-chip model, suggesting cellular exhaustion in the traditional 96-well plate 3D culture method. Values represent the mean ± SD. ∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.01; ∗∗∗p < 0.001; ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001; ns, no significance.

Analysis of GC cell gene expression on the microfluidic chip indicated that the cells exhibited a progressive immunosuppressive phenotype, primarily regulated by FOXO3A-mediated PDL1 expression. It has been suggested that changes in gene expression might result from environmental stress or might simply represent chronic activation because of the presence of tumor cells [28]. Subsequently, AGS cells were co-cultured with CD8+ T cells in a traditional 96-well plate. 7 days later, the AGS cells were isolated and HIF1A, PDL1, and FOXO3A expression levels were determined using RT-qPCR (Fig. 3h). On day 7, tumors in the microfluidic chip exhibited higher expression levels. These results underscored the advantages of the tumor hypoxia immune microenvironment constructed by the tumor-on-chip model in simulating the in vivo TME.

2.4. Hypoxia induces immunotherapy resistance in GC cells by upregulating PD-L1 via FOXO3a

The RNA-seq results showed a significant upregulation of FOXO3A expression in the tumor-on-chip model cultured under hypoxic conditions. Moreover, correlation analysis also demonstrated a strong correlation between FOXO3A and PDL1 expression levels. To further validate the regulation of the protein expression of FOXO3a and PD-L1 in the tumor-on-chip model under hypoxic conditions, immunofluorescence (IF) was employed. After 7 days of culture in the microfluidic chip, the results showed upregulation of both FOXO3a and PD-L1 levels in the hypoxic group compared with those in the normoxic group (Fig. 4a). The protein levels of HIF-1α were also assessed to demonstrate activation of the hypoxic pathway (Fig. S3a). Next, to determine the immunomodulatory role of FOXO3a in GC cells, stable FOXO3A-knockdown GC cell lines were constructed under hypoxic conditions, and the downregulation of both the protein and RNA expression levels of FOXO3a was confirmed (Fig. S3b and c). To confirm the regulation of PD-L1 by FOXO3a in GC cells, we examined the expression levels of PD-L1 upon FOXO3A knockdown. We confirmed that PD-L1 was significantly downregulated at both the protein and RNA levels in the stable FOXO3A-knockdown cells (Fig. 4a and Fig. S3d). Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) coupled with PCR analysis demonstrated specific enrichment of FOXO3a binding at the upstream region relative to the PDL1 transcription start site (Fig. 4b). Notably, under hypoxic conditions, the binding of FOXO3a to the PDL1 promoter increased significantly (Fig. 4c). We subsequently constructed wild-type and mutant plasmids containing the PD-L1 promoter region. Dual-luciferase reporter assays revealed that FOXO3a binding to the PD-L1 promoter significantly enhanced luciferase activity, whereas mutations in the FOXO3a-binding site markedly reduced this activity (Fig. 4d). These findings further confirm that FOXO3a promotes PD-L1 transcription by directly interacting with its promoter region. Additionally, Confocal microscopy scanning showed that FOXO3a was mainly located in the nucleus in hypoxia group, while in normoxia group, FOXO3a was mainly located in the cytoplasm (Fig. 4e). However, under normal oxygen conditions, overexpression of FOXO3a did not result in an elevation of the nuclear proportion of FOXO3a (Fig. S3e). Collectively, these data support a mechanistic model wherein hypoxia triggers FOXO3a nuclear translocation in GC cells, enabling direct promoter binding and subsequent transcriptional activation of PDL1.

Fig. 4.

Hypoxia induces immunotherapy resistance in GC cells by upregulating PD-L1 via FOXO3a. a IF staining was conducted to detect the expression of FOXO3a and PD-L1 in AGS cells cultured for 7 days under hypoxia compared with normoxia. Scale bar, 50 μm. b-c ChIP analysis of FOXO3 binding to the PDL1 promoter in GC cells after hypoxic and normoxic treatments. d Luciferase reporter assay showed the luciferase activity of FOXO3a on the wildtype and mutant promoter of PD-L1. e The IF staining of FOXO3a depicted the subcellular localization of FOXO3a in GC cells cultured under hypoxic and normoxic conditions. f Calcein-AM/PI staining was used to analyze vability in microchambers at day 7. ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001.

To further validate our tumor-on-chip model and demonstrate its application in assessing the tumor response to anti-PD-1 therapy, we assessed the response of GC cells within the microfluidic chip to anti-PD-1 immunotherapy. Nivolumab, an anti-PD-1 antibody, was perfused within the microchannel with CD8+ T cells to simulate intravenous immunotherapy. Nivolumab has demonstrated excellent anti-tumor efficacy in clinical trials and is recommended as a first-line treatment for GC by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) [29]. To assess nivolumab efficacy within the microfluidic chip, we perfused CD8+ T cells with or without nivolumab-supplemented medium into the microchannels (Fig. S4a). Apoptosis analysis demonstrated that nivolumab significantly enhanced CD8+ T cell-mediated tumor cell death under normoxia, whereas hypoxia substantially attenuated T cell cytotoxicity. While nivolumab partially reversed hypoxia-driven therapeutic resistance, its efficacy remained inferior to normoxic conditions, reflecting residual PD-L1/FOXO3a-mediated immunosuppression. CFSE proliferation assays further revealed that CD8+ T cells co-cultured with GC cells exhibited robust proliferative capacity under normoxia, which was markedly suppressed under hypoxic conditions (Fig. S4b). Nivolumab perfusion partially restored hypoxia-impaired T cell proliferation, demonstrating functional reactivation of cytotoxic responses. Subsequently, live/dead staining was employed to visualize the on-chip cell death (Fig. 4f). Following 7 days of nivolumab treatment, GC cells cultured under hypoxic conditions exhibited significantly enhanced resistance to the therapy compared to their normoxic counterparts, as evidenced by differential cell viability profiles between the two groups. However, this resistance was reversed upon the knockdown of FOXO3A expression, while overexpression of FOXO3A under normoxic conditions leads to the reappearance of resistance. To further validate the role of the FOXO3a-PD-L1 pathway in immunotherapy resistance, PDL1 expression was knockdown. The results, consistent with most studies, showed a significant reduction in gastric cancer cell mortality. Collectively, we confirmed that in the tumor-on-chip model, GC cells upregulate PD-L1 expression through the key target FOXO3a, leading to the resistance to immunotherapy.

2.5. High FOXO3a expression correlates with immunotherapy resistance in vivo

To further validate the in vivo immunomodulatory role of FOXO3a a syngeneic mouse tumor model was established by subcutaneously transplanting the FOXO3A-knockdown MFC cells into immunocompetent BALB/c mice (Fig. S5a). The knockdown of FOXO3A demonstrated a significant inhibition of tumor growth in mice when compared with that in the control group (Fig. 5a–c). The transplanted FOXO3A knockdown MFC cells exhibited low levels of PD-L1, leading to a significant inhibition of tumor progression compared with the control tumors, as confirmed using immunohistochemical (IHC) staining (Fig. 5d). Furthermore, knockdown of FOXO3A in the transplanted tumors increased the infiltration rates of CD3+, CD4+, and CD8+ T cells. Analysis of resected graft tumors using flow cytometry further indicated that FOXO3A knockdown resulted in decreased expression of PD-L1, leading to increased expression of IFN-γ, TNF-α, and granzyme B in CD8+ T cells and natural killer (NK) cells within the tumor, ultimately enhancing the cytotoxic capability of immune cells (Fig. 5e and Fig. S5b and c). These findings suggested that FOXO3a, by upregulating the expression of PD-L1, inhibited the infiltration of T cells into the tumor, contributing to immune escape in the TME. Deficiency of FOXO3a in the tumor was associated with a response similar to PD-1 blockade therapy.

Fig. 5.

High expression of FOXO3a induced resistance to immunotherapy in vivo. a-c Six-week-old BALB/c mice were injected subcutaneously with MFC, sh-FOXO3a or sh-control MFC cells (1 × 107 cells). Endpoint images of syngeneic mouse tumor formed by MFC cells in BALB/c mice (a). Volumes, weights (b), and changes in volume every 2–3 days (c) were recorded (n = 6 for each group). d IHC analysis was performed to determine the density of CD3+, CD4+, and CD8+ cells, as well as PD-L1 expression in the subcutaneous syngeneic mouse tumors. Scale bar = 100 μm (left) and 50 μm (right). e Proportions of IFN + cells among tumor-infiltrating NK and CD8+ T cells, as determined using flow cytometry. Simultaneously, the prevalence of PD-L1+ and PD-L2+ cells within the TME was examined. f Expression levels of HIF-1α, PD-L1 and FOXO3a in GC patient tissues before anti-PD-1 treatment were evaluated by IF staining (n = 15 PR patients; n = 15 PD patients). Scale bar = 50 μm g The overall survival of patients with GC with high and low expression levels of FOXO3a who underwent anti-PD-1 antibody treatment was investigated. Values represent the mean ± SD. ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001.

To validate the clinical correlation between resistance to anti-PD-1 therapy and FOXO3a, FOXO3a expression was investigated in archived tissues from 112 patients with GC who underwent anti-PD-1 immunotherapy (i.e., nivolumab) at our center before the initiation of the treatment. The clinicopathological characteristics of these patients were listed in Supplementary Table S2. Subsequently, the treatment outcomes of these patients were compared. IF results showed that FOXO3a expression was higher in patients resistant to anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibody therapy (progressive disease, PD) compared to those who were sensitive to anti-PD-1 treatment (partial response, PR). Additionally, HIF-1α and PD-L1 were also widely expressed in patients resistant to anti-PD-1 treatment (Fig. 5f). Patients with high FOXO3a expression were associated with poorer disease prognosis and showed shortened survival periods compared with those with lower expression of FOXO3a (Fig. 5g). In conclusion, these results implied that high FOXO3a expression in GC tissues might contribute to resistance to anti-PD-1 therapy via modulation of PD-L1. Furthermore, patients were stratified into PD-L1high and PD-L1low subgroups based on Combined Positive Score (CPS). Survival analysis demonstrated that elevated PD-L1 expression correlated with inferior clinical outcomes in nivolumab-treated patients, indicating potential immunotherapy resistance within the PD-L1high cohort (Fig. S5e).

3. Discussion

In recent years, scientists have proposed the theory of "tumor immune editing" which relates to the interplay between tumorigenesis and immunity [30]. According to this theory, the immune system can recognize, surveil, and ultimately eliminate most malignant cells. However, malignant tumor cells can also evolve the ability to circumvent this equilibrium by altering both the tumor cells themselves and the TME, ultimately leading to immune escape [31]. This is also one of the major factors contributing to the poor prognosis of patients with advanced cancer. Nivolumab, the first drug to be approved for advanced GC immunotherapy, has significantly improved anti-tumor immune responses and the prognosis of patients [6]. However, the results of clinical trials indicated that GC can evade immune surveillance and suppress immune responses through various mechanisms [32,33]. When exploring these mechanisms, the complex nature of the TME represents a barrier to accurately and straightforwardly replicating it in vivo. Thus, the construction of novel platforms that efficiently and accurately replicate the in vivo tumor immune microenvironment might expedite the development of next-generation immunotherapies [34].

The tumor organoid chip platform has been widely utilized to simulate the TME of various tumor types and to interpret the effects of different factors on the TME. By modeling the TME using tumor chip technology, long-term, high-resolution monitoring of tumor immune cell interactions can be achieved [35]. This is crucial for understanding how tumors regulate the TME at the cellular and tissue levels to counteract anti-cancer immunity. The microfluidic chip tumor model established in this study, with its innovative design, provides a versatile and effective platform for researching the in vivo tumor immune microenvironment. In this novel microfluidic chip, we adopted a dual-layer design. The multiple parallel microchambers in the chamber layer provide several parallel controls for the experiment, while the microchannels covered with HUVECs perfectly simulate the vascular system of the in vivo tumor. The gas layer on the lower level allows for independent control of the DO concentration in the chamber layer, further minimizing the interference from external variables. Compared with traditional 3D culture models, our microfluidic chip features a biomimetic vasculature for the infusion of immune cells or drugs, allowing continuous 24-h precision perfusion of culture medium to sustain the nutrient supply and waste removal. It also facilitates the study of various mechanisms of the tumor's response to stress conditions in a precisely controlled environment. The tumor-on-chip model also demonstrated robust stability during extended cultivation periods (up to 14 days). These observations suggest that the tumor-on-chip model is representative of the in vivo TME.

Current research suggests that the microenvironment of most solid tumors is hypoxic, accompanied by the activation of a series of related signaling pathways. These pathways enable tumors to adapt to the environment, enhance their invasiveness, and develop resistance to immunotherapy, thereby reducing treatment efficacy [36,37]. Clinical research has indicated a connection between hypoxia-induced immune escape and resistance to ICB therapies. In a study on head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, higher pO2 levels in tumors correlated directly with increased CD8+ T lymphocyte infiltration and activity, and were associated with improved responses to anti-PD-1 treatment, as assessed using progression-free survival and overall survival data. [38]. Similar findings were reported for mouse models of glioma, in which increased HIF-1α levels were linked to reduced anti-PD-L1 antibody activity and, together with the hypoxia-induced dysfunction of CD8+ T lymphocytes, led to worse ICB therapy outcomes [39]. During our study of the hypoxic microenvironment in GC cells using the microfluidic tumor-on-chip model, a pathway was identified wherein elevated PD-L1 expression, regulated by FOXO3a, contributes to resistance to immunotherapy in GC cells. FOXO3a exhibits remarkable heterogeneity in its regulatory networks across diverse tumor types and microenvironmental contexts. Previous investigations in non-small cell lung cancer and ovarian cancer have established FOXO3a as a negative regulator of PD-L1 through direct promoter binding or suppression of STAT3 signaling, with its elevated expression correlating with improved immune profiles and favorable patient prognosis [40,41]. However, our integrated ChIP and luciferase reporter assays demonstrate an unexpected paradigm in GC under hypoxic conditions: FOXO3a directly binds to the PD-L1 promoter region and substantially enhances its transcriptional activation. In our previous research, we also demonstrated that hypoxia could activate FOXO3a in hepatocellular carcinoma, leading to sorafenib resistance [42]. This apparent paradox underscores the context-dependent nature of FOXO3a-mediated PD-L1 regulation, and points out the threefold paradigm-shifting implications of our study. First, we challenge the canonical tumor-suppressor dogma by revealing FOXO3a′s dual functionality in promoting immune checkpoint expression within solid tumors. Second, we delineate a novel hypoxia-mediated epigenetic reprogramming mechanism that fundamentally reshapes FOXO3a′s transcriptional regulatory properties, providing fresh molecular insights into tumor immune editing. Third, we propose the "FOXO3a-PD-L1 axis" as a potential biomarker for immunotherapy resistance in gastric cancer. Crucially, the dynamic equilibrium between FOXO3a′s pro-tumorigenic functions identified here and its classical tumor-suppressive roles warrants systematic investigation. Future studies employing conditional Foxo3a-knockout gastric organoids coupled with single-cell transcriptomic profiling could elucidate microenvironment-dependent functional switching nodes. These discoveries not only advance our understanding of spatiotemporal heterogeneity in immune evasion but also pioneer new avenues for developing microenvironment-tailored precision immunotherapies.

Our study reveals that FOXO3a and HIF-1α exhibit context-dependent roles in regulating PD-L1 expression, with FOXO3a emerging as the dominant transcriptional activator of PD-L1 under hypoxia in GC. While HIF-1α is a well-established hypoxia master regulator and driver of PD-L1 in cancers like breast cancer [43], our ChIP and luciferase assays demonstrated that FOXO3a binds the PDL1 promoter with higher affinity in GC, driving its transcription independently of HIF-1α. However, potential synergy between these factors may exist in other pathways: HIF-1α could stabilize FOXO3a by inhibiting Akt-mediated phosphorylation (which promotes FOXO3a nuclear retention), while FOXO3a may amplify HIF-1α′s pro-angiogenic effects via VEGF signaling. The universality of FOXO3a-driven PD-L1 regulation varies across tumor types. In hepatocellular carcinoma, FOXO3a similarly upregulates PD-L1 under hypoxia, correlating with sorafenib resistance [42]. Conversely, in melanoma, FOXO3a predominantly suppresses PD-L1 in normoxia but may adopt a pro-tumorigenic role under hypoxia. This plasticity suggests that FOXO3a′s function is shaped by tumor-specific genetic, epigenetic, and microenvironmental factors (e.g., oxidative stress, cytokine milieu) [44]. Clinically, targeting FOXO3a could enhance PD-1 blockade efficacy in FOXO3a-high tumors, while HIF-1α inhibitors may benefit HIF-1α-dominant malignancies. Future studies should explore FOXO3a/HIF-1α crosstalk in multi-omics datasets and validate their roles in patient-derived organoids across cancer types.

Our study advances the understanding of PD-L1 regulation in GC by identifying FOXO3a as a hypoxia-inducible transcription factor that directly binds the PDL1 promoter, driving its expression and contributing to immunotherapy resistance. This mechanism contrasts with existing strategies that primarily target post-transcriptional PD-L1 regulation, such as nanoparticle-mediated siRNA delivery or antibody-based blockade, which focus on degrading PD-L1 protein or blocking its interaction with PD-1 [45]. While these approaches demonstrate clinical versatility and tumor-targeting precision, our work uncovers a novel transcriptional axis specific to hypoxic microenvironments, offering a biomarker-driven rationale for combining FOXO3a inhibition with PD-1 blockade. The physiological relevance of our tumor-on-chip model further distinguishes this work from conventional systems. Unlike nanoparticle-based platforms like BBR@IR68-Lip, which integrates photodynamic therapy with hypoxia reversal and dual PD-L1/IDO1 inhibition, our dual-layer microfluidic chip recapitulates vascularized 3D tumor-immune interactions under chronic hypoxia, maintaining >90 % tumor cell viability for 14 days [46]. This model captures hypoxia-driven T cell dysfunction and FOXO3a/PD-L1-mediated resistance with high fidelity, enabling mechanistic studies inaccessible to static 2D cultures or nanoparticle-focused designs. However, compared to the clinically adaptable BBR@IR68-Lip or Ch-Met systems [47], which simultaneously address chemotherapy resistance, metastasis, and PD-L1 suppression.

As a versatile chip, we aimed to minimize its complexity to make the chip simple, user-friendly, and cost-effective, allowing it to be deployed in any department without requiring excessive hardware equipment. This will significantly enhance our understanding of tumor immune evasion and become an indispensable multifunctional tool for cancer modeling and tumor-immune interaction research, thereby providing predictive, diagnostic, and therapeutic value to promote cancer immunotherapy. Although the microfluidic chip in this study has shown reliable results in immune therapy, it still has some limitations. For instance, extracting cells from the microfluidic chip for further biochemical analysis is complex and indirect. The low cell count in the microfluidic chip could also be a limitation when more cells are needed for routine biochemical analysis or when quantifying secreted molecules. However, with the development of microfluidic technology, the miniaturization of microfluidic systems will be compatible with limited input samples (e.g., patient-derived biopsies), enabling parallel testing with tissue fragments or digested dispersed cells, which is on a much larger scale than current macro models [48,49]. By using high-throughput microfluidic analysis with biopsy samples, more information can be obtained, providing a clinically relevant time frame for personalized treatment and offering a feasible path to integrate human tissue-based testing into preclinical studies.

In summary, the developed microfluidic tumor-on-chip model provides a versatile and convenient tool to study the TME, bridging the gap between animal models and in vitro platforms. Our results for the immune escape of GC cells in a hypoxic TME gained using this platform will enhance our understanding of hypoxia-mediated immune responses and aid the development of alternative strategies for GC treatments. In addition, given that hypoxia is a common feature of solid tumors, we believe that the tumor-on-chip model and the identified mechanisms can be extended to the treatment of other types of solid tumors. These findings bridge mechanistic discovery with translational innovation, addressing a critical unmet need in cancer immunotherapy.

4. Methods and materials

4.1. Bioinformatics analysis

We downloaded the RNA-seq data and the corresponding clinical data, including tumor stage, and overall survival times for The TCGA-STAD dataset from the UCSC Xena project (http://xena.ucsc.edu/). We excluded patients with a survival time shorter than 30 days and those with incomplete survival data. Finally, a cohort of 337 patients with available RNA-seq data and survival time were included in our analysis. The 200 genes in the hallmark gene sets of hypoxia were downloaded from MSigDB (http://www.gsea-msigdb.org/gsea/msigdb/). The hypoxia score for each tumor was calculated using gene set variation analysis (GSVA) [50] based on the 200 hypoxia-related genes. The optimal cut-off value of the hypoxia scores based on overall survival was defined using the X-tile program [51]. Based on the optimal cut-off value, we identified three groups: “hypoxiahigh”, “hypoxiamid” and “hypoxialow” to estimate the patients' hypoxia status. The TIDE algorithm was employed to estimate the TIDE score and to predict the potential for tumor immune escape according to the gene expression profile of the tumor samples [52].

4.2. Construction of the microfluidic chip

PDMS (Sylgard 184, Dow Corning, Corning, NY, USA) was used to construct the microfluidic chip through a well-established soft lithography method. The microfluidic chip was fabricated with precise dimensional specifications: gas channels (width = 500 μm, depth = 100 μm; serpentine spacing = 200 μm) and cell culture chambers (diameter = 900 μm) interconnected by 200 μm-wide × 150 μm-high channels. These standardized parameters ensured batch-to-batch consistency. Initially, a silicon wafer was spin-coated with a negative photoresistor (SU-82050, MicroChem, Austin, TX, USA). Next, the wafer was subjected to soft baking on a heating plate, followed by cooling to room temperature. Then, the wafer was exposed to light using a photolithographic machine (URE-2000-35L, Institute of Optics and Electronics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, China) through a corresponding photomask. Following exposure, the wafer underwent baking and was then cooled to room temperature before subsequent development. Trimethylchlorosilane (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was used to fumigate the patterned silicon wafer for 10 min in a sealed box. The PDMS prepolymer and curing agent were then uniformly mixed at a 10:1 ratio, followed by degassing. The PDMS mixture was poured into the chamber layers of the prepared wafer. The entire chip was then cured for 1 h at 80 °C. The gas layer and chamber layer were separated, cut, and perforated. For membrane fabrication, PDMS was spin-coated onto 3-inch silicon wafers using a G3P-8 spin-coater (Specialty Coating Systems, Indianapolis, IN, USA) at 800 rpm for 60 s to achieve 100 μm thickness. Channel dimensions and membrane uniformity were verified using a Bruker Dektak XT profilometer (Billerica, MA, USA), with tolerances maintained within ±5 μm. The cover structure and bottom structure were clamped with PMMA and fixed with screws, creating a reassembleable chip. After 30 min of ultraviolet irradiation, as shown in Fig. S6, extracellular matrix gel (Matrigel; Corning Inc., Corning, NY, USA; 356237) mixed with single tumor cells was injected into the chip. Then, the air was pushed back into the chip, and the narrow channel on the microchamber side acted as a barrier to the gas, causing the gas to only enter the direct channel and empty the fluid in it, such that the tumor cell suspension stayed only in the microchambers. The Matrigel interface was formed in the tumor cell culture area and the wide channel on the side of microchambers. Finally, the suspension of HUVECs was added. Through upright chip and overnight treatment, HUVECs were attached to the Matrigel interface at the wide channel on one side of the microchambers. Finally, the tumor-on-chip model was connected to the Fluigent Microfluidic flow control system (Fluigent, Ile-de-France, France), flow rates were maintained at 20 μL/min. Hypoxic gradients (0.1 %–21 % O2) were generated using compressed gas mixtures regulated by glass rotameters and miniaturized gas regulators, with pressure stabilized at 4 psi via a three-way valve and digital manometer. Additionally, the DO probe (PreSens, Microx 4 trace; Regensburg, Germany) was used to measure the actual pO2 within the microchambers. At this point, a complete tumor-on-chip model had been established.

4.3. Cell lines and culture

The AGS (human gastric adenocarcinoma cells, TCH-C124), MKN-45 (human gastric adenocarcinoma cells, TCH-C397) and HUVEC cell lines were procured from Haixing Biosciences (Zhaoqing, China). MGC-803 (human gastric poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma, C6582) and HGC-27 (human gastric undifferentiated gastric carcinoma cells, C6365) were procured from Beyotime. The mouse GC cell line MFC was obtained from Procell (Wuhan, China; CL-0156). These cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA; 12491023) containing 10 % fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco, A3160902).

A Dynabeads FlowComp Human CD8 Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA; 11362D) was employed to extract highly pure human CD8+ T cells. In brief, 25 μl of anti-human CD8 antibody was added to 2 ml of pre-chilled whole blood. After incubation on ice for 10 min, 4 ml of separation buffer was added, and the mixture was centrifuged for 15 min at 350×g. The supernatant was discarded, 75 μl of re-suspended FlowComp Dynabeads were added, and the mixture was placed at room temperature for 15 min. Then, 4 ml of isolation buffer was added and the tube was placed in the magnet stand for 3 min. With the tube still in magnet stand, the supernatant was removed and discarded; this process was repeated twice. Subsequently, the pellet was resuspended in 1 ml of FlowComp Release Buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and incubated at room temperature for 10 min. The contents were mixed by Pipetting 10 times and placed in the magnet stand for 1 min. The supernatant was transferred to a new tube, placed in the magnet stand for 1 min, allowed to settle, and then the supernatant comprising bead-free cells was transferred to another new tube. Next, 2 ml of separation buffer was added, centrifuged at 350×g for 8 min, the supernatant discarded, and the cell pellet resuspended in OpTmizer CTS T-Cell Expansion SFM (Thermo Fisher Scientific, A1048501) for subsequent expansion and cultivation of CD8+ T cells.

For FOXO3A or PDL1 knockdown, lentiviral vectors harboring a short hairpin RNA (shRNA) targeting FOXO3A or PDL1 and negative control were synthetized and cloned into vector pLKO.1. Following the manufacturer's instructions, these plasmids were introduced into AGS cells using the lipofectamine iMAX method (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 13778075). Stably transfected cells were selected by treating them with 10 μg ml−1 puromycin (Thermo Fisher Scientific, A1113802) for 3 days. FOXO3a-OE AGS cells were established by lentiviral infection of AGS cells using the FOXO3a-pCDH, pMD2. G, and pSPAX2 lentiviral packaging system.

4.4. Cell staining

The localization of HUVECs, GC cells, and CD8+ T cells was monitored by staining with fluorescent markers. Specifically, HUVECs were labeled using vibrant DiO (green; Thermo Fisher Scientific, V22886), GC cells were labeled using DiI (red; Thermo Fisher Scientific, V22885), and CD8+ T cells were labeled using DiD (infra-red; Thermo Fisher Scientific, V22887). In brief, cells were enumerated and suspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at 1 million cells. ml−1. Five microliters of a vibrant labeling agent were added per milliliter of cell suspension. After incubation for 10 min, the cell suspension was centrifuged (250×g, 5 min) and rinsed twice with 1 ml of PBS to remove excess staining. The three stains could distinguish the three cell populations in the first 72 h.

4.5. Flow cytometry

The separation of CD8+ T cells and AGS cells was performed using fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS). The mixed cells (CD8+ T cells and GC cells) were washed and suspended in PBS containing 10 % FBS. The cells were then labeled separately with CD8+ T cell marker antibodies and anti-epithelial cell adhesion molecule (EpCAM) antibodies. Subsequently, CD8+ T cells and AGS cells were mixed, ensuring that cells were suspended in PBS containing 10 % FBS. A BD FACSAria Fusion Cell Sorter (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) was employed for cell sorting.

Flow cytometry analysis of intracellular proteins in tumor cells of syngeneic mouse model was determined using an Intracellular Flow Cytometry Kit (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA; 13593S). Briefly, cells isolated from the syngeneic mouse tumor were resuspended in 100 μl of 4 % formaldehyde and fixed at room temperature for 15 min. Permeabilization of the cells was achieved by gently adding ice-cold 100 % methanol in a slow, controlled manner while mildly vortexing the cells, reaching a final concentration of 90 % methanol. Subsequently, the cells were subjected to corresponding antibody staining.

4.6. RNA-seq

After a period of culture, the upper part of the microfluidic chip was removed, and the matrix gel containing GC cells was extracted. Subsequently, it was dissolved using Collagenase A (Sigma Aldrich, 10103586001) in a 37 °C incubator. After centrifugation at 160×g for 3 min, the cells were collected, and a TRIzolPlus RNA pure kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 12183555) was employed to extract the total RNA. The quality of the RNA quality was determined using a 5300 Bioanalyser (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) and quantified on an ND-2000 instrument (NanoDrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE, USA). The total RNA was constructed into sequencing libraries, which were sequenced using a NovaSeq 6000 sequencer (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA; 2 × 150 bp read length). The DEGs between two different samples were identified by comparing the expression level of each transcript, calculated using the transcripts per million reads (TPM) method. RNA-Seq by Expectation-Maximization (RSEM) [53] was employed to quantify gene abundance. DESeq2 [54] or DEGseq [55] were employed for differential expression analysis. Genes with a |log2 fold-change (FC)|≥1 and a false discovery rate (FDR) ≤ 0.05 (DESeq2) or FDR ≤0.001 (DEGseq) were considered as significant DEGs. Next, the DEGs were subjected to GO and KEGG functional-enrichment analysis using Goatools and KOBAS [56], respectively, to identify the significant association of the DEGs with GO terms and KEGG pathways according to a Bonferroni-corrected P-value ≤0.05 in comparison with the whole-transcriptome background.

4.7. Cell viability

A Calcein AM/PI cell viability and cytotoxicity assay kit (Beyotime, Shanghai, China; C2015S) was employed to assess cellular viability within the tumor-on-chip model. Specifically, according to the supplier's instructions, a detection buffer was prepared using Calcein acetoxymethyl ester (Calcein-AM; 1 μl ml−1) and propidium iodide (PI; 1 μl ml−1) in a ratio of 1:1000. To ensure uniform staining, the Matrigel was exposed by removing the upper part of the microfluidic chip. After adding the Calcein-AM/PI solution to the top, the chip was incubated at 37 °C for 30 min. Subsequently, fluorescence imaging was conducted using a confocal microscope (Leica, STELLARIS 5; Leica, Wetzlar, Germany). To assess apoptosis in GC cells under long-term culture, an Annexin V-FITC/PI Apoptosis Kit (MultiScience, AP101C) was used. Briefly, cells were collected from the tumor-on-chip model or 96-well plate, washed two times using pre-cooled PBS, and resuspended in 500 μl of 1 × Binding Buffer. Each tube was added with 5 μl of Annexin V-FITC and 10 μl of PI, and incubated for 5 min in the dark at room temperature. Subsequently, Annexin V-FITC and PI were detected using the FITC detection channel and PI detection channel, respectively, on a flow cytometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Attune CytPix). The results were analyzed using FlowJo v10.9.0 (TreeStar, Ashland, OR, USA). For the Cell counting Kit 8 (CCK-8) assay, cells were seeded at a density of 1000 cells per well in a 96-well plate or a tumor-on-chip model, and added with fresh culture medium. A CCK-8 kit (Beyotime, C0038) was used to assess cell viability on days 1, 7, and 14, following a 2-h incubation at 37 °C. A microplate reader (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Varioskan LUX) was utilized to determine the absorbance at 450 nm.

4.8. RT-qPCR

A TRIzol RNA purification kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 12183555) was employed to extract total RNA from GC cells, which was converted into cDNA employing a reverse transcription kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 4368814). The cDNA was mixed with SYBR Green Premix (Thermo Fisher Scientific, A25742) and RNase-free water to prepare a 20 μl qPCR reaction system. The qPCR reaction was carried out as follows: denaturation at 95 °C for 3 min; followed by amplification at 95 °C for 10 s, 60 °C for 10 s, and 72 °C for 30 s. The RT-qPCR primer sequences are listed in Supplementary Table 3.

4.9. Immunofluorescence

GC cells, either containing or lacking shFOXO3a, were treated under hypoxic or normoxic conditions for 7 days. Subsequently, the cells were fixed onto slides, incubated with different primary antibodies, and then subjected to secondary antibody incubation. Cell nuclei were counterstained using 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). Images were acquired using a confocal microscope (Leica, STELLARIS 5) and quantitatively analyzed using ImageJ (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA).

4.10. Western blotting

Radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (Beyotime, P0013B) with Protease Inhibitors (Beyotime, P1006) and Phosphatase Inhibitor (Beyotime, P1045) was used to extract whole-cell lysates. After separation of the protein samples using SDS-PAGE and transfer to a polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane, the proteins on the membranes were subjected to western blotting employing the specified antibodies.

4.11. Chromatin immunoprecipitation analysis

A SimpleChIP Plus Enzymatic Chromatin IP Kit (Cell Signaling Technology, #9005) was used to perform ChIP. In brief, according to the manufacturer's instructions, cells were cross-linked with 1 % formaldehyde and then homogenized in lysis buffer. The chromatin was enzymatically digested and incubated with protein G magnetic beads and ChIP-grade anti-FOXO3a antibodies (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 720128). DNA was extracted from the precipitate and analyzed using real-time PCR. Supplemental Table 1 contains the sequences of the primers amplifying the PDL1 promoter region. IgG was used as a negative control.

4.12. Dual - luciferase reporter assay

Putative binding sites were predicted using TargetScan (http://www.targetscan.org/). Custom 3′-UTR sequences were synthesized by GeneChem and cloned into reporter vectors to generate luciferase reporter plasmids. AGS cells were seeded into 96-well plates and transfected with the designated reporter plasmids using Lipofectamine 3000 reagent. Luciferase activity was assessed 48 h post-transfection with a dual-luciferase assay system (E1910, Promega) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

4.13. Animals

The animal experiments were approved by the Animal Experiment Center of Ningbo University (NBULAC-202312150). The Hangsi biology (Hangzhou, China; BALB/C) supplied eighteen female BALB/c mice (six weeks old). The left flanks of the mice were subcutaneously inoculated with 5 × 104 MFC cells (sh-control, sh-FOXO3a) suspended in 100 μl of PBS. As shown in Fig. S5a, after inoculation, the mice were injected intraperitoneally with anti-mPD-1 antibody (Bio X Cell, Lebanon, NH, USA; BE0089; 100 μl every 3 days). The anti-mPD-1 antibody was administered intraperitoneally at 100 μg per mouse (5 mg/kg) every 3 days, a regimen derived through human-to-mouse dose translation using body surface area normalization (12.3/37 conversion factor) and aligned with preclinical benchmarks (1–10 mg/kg range). This dose ensures >90 % PD-1 receptor occupancy while minimizing immune-related toxicity. Survival rates and tumor volumes for all mice were monitored. The survival rate was determined based on the days from tumor cell inoculation to euthanasia, guided by symptoms such as hemiplegia, seizures, significant weight loss (exceeding 20 %), immobility, and other severe neurological deficits. Tumor volumes were measured via caliper every 3 days (days 0, 3, 6, 9, 12) to capture dynamic treatment effects. Tumor volumes were determined using the formula: volume = length × width2/2, in which length represents the longest diameter of the tumor and width represents the shortest diameter. Statistical analysis of the results was carried out using GraphPad Prism v10.0.3 (GraphPad Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA).

4.14. IHC staining

We obtained tumor specimens from 30 patients with GC receiving anti-PD-1 or anti-PD-L1 antibody treatment at the Affiliated Lihuili Hospital of Ningbo University. In brief, tumor samples were incubated with anti-FOXO3a antibodies (Cell Signaling Technology, 12829S), followed by treatment with biotinylated secondary antibodies, and then incubated with avidin-biotin-peroxidase complexes. Images of representative regions were captured using an Aperio ImageScope (Leica). For the syngeneic mouse model, the tumors were embedded in paraffin and cut into 4 μm sections. The sections were stained using hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) or incubated with primary antibodies for immunohistochemistry.

4.15. Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism v10.0.3, and the results are presented as the mean ± SD based on a minimum of three biological replicates. The Calcein AM/PI staining was repeated five times on the tumor-on-chip model and syngeneic mouse models were repeated four times. All other experiments were repeated three times. To compare the data between two groups, we used a t-test. To compare the data among multiple groups, we used one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). The association between PD-L1 and FOXO3a expression levels was determined using Pearson correlation analysis. For all tests, statistical significance was indicated by a P-value <0.05.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Hanting Xiang: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Software, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Fangqian Chen: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Supervision, Software, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Zhebin Dong: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Supervision, Software, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Xianlei Cai: Visualization, Validation, Software, Resources, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Data curation, Conceptualization. Yuan Xu: Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Software, Resources, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Data curation. Zhengwei Chen: Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Software, Resources, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation. Sangsang Chen: Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Software, Resources, Methodology, Data curation. Tianci Chen: Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation. Jiarong Huang: Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Investigation, Data curation. Fangfang Chen: Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Formal analysis, Data curation. Yahua Zheng: Visualization, Validation, Data curation. Jingyun Ma: Visualization, Software, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Data curation, Conceptualization. Weiming Yu: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Data curation, Conceptualization. Chao Liang: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Supervision, Software, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Conceptualization.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Lihuili Hospital of Ningbo University (no.KY2023PJ400), with an exemption from informed consent. We included patients aged 20–90 years with histologically confirmed GC who met indications for neoadjuvant therapy with nivolumab combined with SOX/XELOX regimen for locally advanced TNM stage III disease, demonstrated no distant metastasis on preoperative imaging, and had complete clinical follow-up data spanning ≥36 months. However, we excluded patients with metastatic tumors of non-gastric origin; severe organ dysfunction precluding systemic therapy; history of acute cardiovascular events (unstable angina, myocardial infarction, or cerebrovascular accident) within 6 months prior to treatment; incomplete pathological material; or insufficient tumor tissue for molecular-pathological reassessment. According to the criteria above, the medical files of 112 patients who presented to our department between January 2022 and January 2024 were retrospectively reviewed. No specific consent is needed for statistical analyses of aggregated deidentified data. For this study, the raw data were first extracted from HIS, and patients’ identities, including names, screening IDs, patient IDs, and mobile phone numbers, were de-identified.

Consent for publication

The authors confirm that they have obtained written consent from each patient to publish the manuscript.

Funding sources

This study has been financially supported by Zhejiang Medical and Health Science and Technology Project (2022KY1091, 2023KY236, 2023KY1033, LBY24H200001), Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation (LTGY24B050001), Zhejiang Provincial Ten Thousand Plan to Chao Liang (2023) and Ningbo Natural Science Foundation (2021J279, 2022J252, 2022J264).

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgment

None.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mtbio.2025.101925.

Contributor Information

Jingyun Ma, Email: majingyun198401@126.com.

Weiming Yu, Email: yuweiming7601@163.com.

Chao Liang, Email: movingstar-lchao@163.com.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- 1.Sung H., Ferlay J., Siegel R.L., et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021;71(3):209–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Al-Batran S.-E., Hofheinz R.D., Pauligk C., et al. Histopathological regression after neoadjuvant docetaxel, oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin versus epirubicin, cisplatin, and fluorouracil or capecitabine in patients with resectable gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction adenocarcinoma (FLOT4-AIO): results from the phase 2 part of a multicentre, open-label, randomised phase 2/3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(12):1697–1708. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30531-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bernards N., Creemers G.J., Nieuwenhuijzen G.A.P., et al. No improvement in median survival for patients with metastatic gastric cancer despite increased use of chemotherapy. Ann. Oncol. 2013;24(12):3056–3060. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smyth E.C., Nilsson M., Grabsch H.I., et al. Gastric cancer. Lancet. 2020;396(10251):635–648. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31288-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Takei S., Kawazoe A., Shitara K. The new era of immunotherapy in gastric cancer. Cancers (Basel) 2022;14(4) doi: 10.3390/cancers14041054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Janjigian Y.Y., Shitara K., Moehler M., et al. First-line nivolumab plus chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone for advanced gastric, gastro-oesophageal junction, and oesophageal adenocarcinoma (CheckMate 649): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2021;398(10294):27–40. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00797-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wu Q., You L., Nepovimova E., et al. Hypoxia-inducible factors: master regulators of hypoxic tumor immune escape. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2022;15(1):77. doi: 10.1186/s13045-022-01292-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lin R., Zhang H., Yuan Y., et al. Fatty acid oxidation controls CD8(+) tissue-resident memory T-cell survival in gastric adenocarcinoma. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2020;8(4):479–492. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-19-0702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huber V., Camisaschi C., Berzi A., et al. Cancer acidity: an ultimate frontier of tumor immune escape and a novel target of immunomodulation. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2017;43:74–89. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2017.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Unwith S., Zhao H., Hennah L., et al. The potential role of HIF on tumour progression and dissemination. Int. J. Cancer. 2015;136(11):2491–2503. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guan D., Li C., Li Y., et al. The DpdtbA induced EMT inhibition in gastric cancer cell lines was through ferritinophagy-mediated activation of p53 and PHD2/hif-1 alpha pathway. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2021:218. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2021.111413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Piao H.-Y., Liu Y., Kang Y., et al. Hypoxia associated lncRNA HYPAL promotes proliferation of gastric cancer as ceRNA by sponging miR-431-5p to upregulate CDK14. Gastric Cancer. 2022;25(1):44–63. doi: 10.1007/s10120-021-01213-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhao J., Xiao A., Liu C., et al. The HIF-1A/miR-17-5p/PDCD4 axis contributes to the tumor growth and metastasis of gastric cancer. Signal Transduct. Targeted Ther. 2020;5(1):46. doi: 10.1038/s41392-020-0132-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taylor C.T., Colgan S.P. Regulation of immunity and inflammation by hypoxia in immunological niches. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2017;17(12):774–785. doi: 10.1038/nri.2017.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ayuso J.M., Virumbrales-Munoz M., Mcminn P.H., et al. Tumor-on-a-chip: a microfluidic model to study cell response to environmental gradients. Lab Chip. 2019;19(20):3461–3471. doi: 10.1039/c9lc00270g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang J., Tavakoli H., Ma L., et al. Immunotherapy discovery on tumor organoid-on-a-chip platforms that recapitulate the tumor microenvironment. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2022:187. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2022.114365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ayuso J.M., Virumbrates-Munoz M., Mcminn P.H., et al. Tumor-on-a-chip: a microfluidic model to study cell response to environmental gradients. Lab Chip. 2019;19(20):3461–3471. doi: 10.1039/c9lc00270g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li R., Zhang X., Lv X., et al. Microvalve controlled multi-functional microfluidic chip for divisional cell co-culture. Anal. Biochem. 2017;539:48–53. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2017.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang W., Li L., Ding M., et al. A microfluidic hydrogel chip with orthogonal dual gradients of matrix stiffness and oxygen for cytotoxicity test. Biochip Journal. 2018;12(2):93–101. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wan L., Neumann C.A., Leduc P.R. Tumor-on-a-chip for integrating a 3D tumor microenvironment: chemical and mechanical factors. Lab Chip. 2020;20(5):873–888. doi: 10.1039/c9lc00550a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jiang P., Gu S., Pan D., et al. Signatures of T cell dysfunction and exclusion predict cancer immunotherapy response. Nat. Med. 2018;24(10):1550–1558. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0136-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shao C., Yang F., Miao S., et al. vol. 17. Molecular Cancer; 2018. (Role of Hypoxia-Induced Exosomes in Tumor Biology [J]). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baghba R., Roshangar L., Jahanban-Esfahlan R., et al. Tumor microenvironment complexity and therapeutic implications at a glance. Cell Commun. Signal. 2020;18(1) doi: 10.1186/s12964-020-0530-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.St Paul M., Ohashi P.S. The roles of CD8(+) T cell subsets in antitumor immunity. Trends Cell Biol. 2020;30(9):695–704. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2020.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.You L., Wu W., Wang X., et al. The role of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 in tumor immune evasion. Med. Res. Rev. 2021;41(3):1622–1643. doi: 10.1002/med.21771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Duan Y., Tian X., Liu Q., et al. Role of autophagy on cancer immune escape. Cell Commun. Signal. 2021;19(1):91. doi: 10.1186/s12964-021-00769-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lapeyre-Prost A., Terme M., Pernot S., et al. Immunomodulatory activity of VEGF in cancer. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol. 2017;330:295–342. doi: 10.1016/bs.ircmb.2016.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tillquist N.M., Thorndyke M.P., Thomas T.A., et al. Impact of cell culture and copper dose on gene expression in bovine liver. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2022;200(5):2113–2121. doi: 10.1007/s12011-021-02829-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ajani J.A., D'Amico T.A., Bentrem D.J., et al. Gastric cancer, version 2.2022, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2022;20(2):167–192. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2022.0008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lei X., Lei Y., Li J.K., et al. Immune cells within the tumor microenvironment: biological functions and roles in cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Lett. 2020;470:126–133. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2019.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barsoum I.B., Koti M., Siemens D.R., et al. Mechanisms of hypoxia-mediated immune escape in cancer. Cancer Res. 2014;74(24):7185–7190. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-2598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu X., Cao Y., Li R., et al. Poor clinical outcomes of intratumoral dendritic cell-specific intercellular adhesion molecule 3-grabbing non-integrin-positive macrophages associated with immune evasion in gastric cancer. Eur. J. Cancer. 2020;128:27–37. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2020.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ma X., Jia S., Wang G., et al. TRIM28 promotes the escape of gastric cancer cells from immune surveillance by increasing PD-L1 abundance. Signal Transduct. Targeted Ther. 2023;8(1):246. doi: 10.1038/s41392-023-01450-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Boussommier-Calleja A., Li R., Chen M.B., et al. Microfluidics: a new tool for modeling cancer-immune interactions. Trends Cancer. 2016;2(1):6–19. doi: 10.1016/j.trecan.2015.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Paterson K., Zanivan S., Glasspool R., et al. Microfluidic technologies for immunotherapy studies on solid tumours. Lab Chip. 2021;21(12):2306–2329. doi: 10.1039/d0lc01305f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Noman M.Z., Desantis G., Janji B., et al. PD-L1 is a novel direct target of HIF-1α, and its blockade under hypoxia enhanced MDSC-mediated T cell activation. J. Exp. Med. 2014;211(5):781–790. doi: 10.1084/jem.20131916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Petrova V., Annicchiarico-Petruzzelli M., Melino G., et al. The hypoxic tumour microenvironment. Oncogenesis. 2018;7(1):10. doi: 10.1038/s41389-017-0011-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zandberg D.P., Menk A.V., Velez M., et al. Tumor hypoxia is associated with resistance to PD-1 blockade in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. J. Immunother. Cancer. 2021;9(5) doi: 10.1136/jitc-2020-002088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ding X.C., Wang L.L., Zhang X.D., et al. The relationship between expression of PD-L1 and HIF-1α in glioma cells under hypoxia. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2021;14(1):92. doi: 10.1186/s13045-021-01102-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chung Y.M., Khan P.P., Wang H., et al. Sensitizing tumors to anti-PD-1 therapy by promoting NK and CD8+ T cells via pharmacological activation of FOXO3. J. Immunother. Cancer. 2021;9(12) doi: 10.1136/jitc-2021-002772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Song S., Tang H., Quan W., et al. Estradiol initiates the immune escape of non-small cell lung cancer cells via ERβ/SIRT1/FOXO3a/PD-L1 axis. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2022;107 doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2022.108629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liang C., Dong Z., Cai X., et al. Hypoxia induces sorafenib resistance mediated by autophagy via activating FOXO3a in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cell Death Dis. 2020;11(11):1017. doi: 10.1038/s41419-020-03233-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang S., Zhang X., Chen Q., et al. FTO activates PD-L1 promotes immunosuppression in breast cancer via the m6A/YTHDF3/PDK1 axis under hypoxic conditions. J. Adv. Res. 2024 doi: 10.1016/j.jare.2024.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Barnwal A., Tamang R., Sanjeev D., et al. Ponatinib delays the growth of solid tumours by remodelling immunosuppressive tumour microenvironment through the inhibition of induced PD-L1 expression. Br. J. Cancer. 2023;129(6):1007–1021. doi: 10.1038/s41416-023-02316-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhou Z., Wang H., Li J., et al. Recent progress, perspectives, and issues of engineered PD-L1 regulation nano-system to better cure tumor: a review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024;254(Pt 2) doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.127911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zheng C., Luo W., Liu Y., et al. Killing three birds with one stone: multi-stage metabolic regulation mediated by clinically useable berberine liposome to overcome photodynamic immunotherapy resistance. Chem. Eng. J. 2023;454 [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhou Z., Liu Y., Jiang X., et al. Metformin modified chitosan as a multi-functional adjuvant to enhance cisplatin-based tumor chemotherapy efficacy. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023;224:797–809. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2022.10.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lv M., Zhou W., Tavakoli H., et al. Aptamer-functionalized metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) for biosensing. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2021;176 doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2020.112947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fu G., Hou R., Mou X., et al. Integration and quantitative visualization of 3,3',5,5'-tetramethylbenzidine-probed enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay-like signals in a photothermal bar-chart microfluidic chip for multiplexed immunosensing. Anal. Chem. 2021;93(45):15105–15114. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.1c03387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Haenzelmann S., Castelo R., Guinney J. GSVA: gene set variation analysis for microarray and RNA-Seq data. BMC Bioinf. 2013;14 doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-14-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Camp R.L., Dolled-Filhart M., Rimm D.L. X-tile: a new bio-informatics tool for biomarker assessment and outcome-based cut-point optimization. Clin. Cancer Res. 2004;10(21):7252–7259. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jiang P., Gu S., Pan D., et al. Signatures of T cell dysfunction and exclusion predict cancer immunotherapy response. Nat. Med. 2018;24(10):1550. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0136-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]