Abstract

Background

Chondrosarcoma, a rare and heterogeneous malignant bone tumor, presents significant clinical challenges due to its complex molecular underpinnings and limited treatment options. In this study, we employ single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) and bioinformatics analyses to delineate cell subtypes, decipher signaling networks, and identify gene expression patterns, thereby providing novel insights into potential therapeutic targets and their implications in cancer biology.

Methods

scRNA-seq was performed on both clinical and experimental chondrosarcoma samples. Dimensionality reduction techniques (UMAP/t-SNE) were used to cluster cell subtypes, followed by Gene Ontology (GO) and pathway analyses to elucidate their biological functions. Cell–cell interaction networks, including the MIF signaling network, were reconstructed to map intercellular communications. Pseudotime analysis charted differentiation trajectories, while machine learning models evaluated the classification accuracy of gene expression patterns. GSEA was conducted to identify state-specific differential expression profiles.

Results

Over ten distinct cell subtypes were identified, including endothelial cells, fibroblasts, and epithelial cells. Key signaling pathways, such as TGF-beta signaling, focal adhesion, and actin cytoskeleton regulation, were found to mediate intercellular interactions. The MIF signaling network underscored the critical roles of immune cells within the tumor microenvironment. Pseudotime analysis revealed dynamic differentiation states, while state-specific gene expression patterns emerged from GSEA. Machine learning models demonstrated robust classification performance across training and external validation datasets.

Conclusions

This comprehensive analysis uncovers the cellular heterogeneity and complex intercellular networks in chondrosarcoma, elucidating critical molecular pathways and identifying novel therapeutic targets. By integrating gene expression, signaling networks, and advanced computational methods, this study contributes to the broader understanding of cancer biology and highlights the potential for precision medicine strategies in treating chondrosarcoma.

Keywords: Chondrosarcoma, Single-cell RNA sequencing, TGF-beta signaling, Cell subtypes, Bioinformatics analysis

Introduction

Chondrosarcoma is a rare type of bone cancer and quite aggressive that most times mainly happen in adults. Due to the outside chemotherapy and radiation projection, surgical resection is the mainstay of treatment [1–3]. The landscape of genes altered in chondrosarcoma is complex and this complexity presents a major barrier to the development of effective therapeutic strategies. Developing suitable therapeutic precautions must require the knowledge of cellular heterogeneity concerning tumor and its connecting signaling points.

Single-cell RNA sequencing has recently allowed for unparalleled dissection of tumors. Using this technology, unique cellular subtypes within a tumor can be resolved, contributing to the characterization of the microenvironment of tumors during cancer progression [4–6]. Single-cell transcriptomics provides recrudescent information about cell types and states whereby possible therapeutic targets could be determined.

Here we utilize single-cell RNA sequencing to investigate the cellular heterogeneity of chondrosarcoma. We cluster various cell subtypes and employ Gene Ontology (GO) and pathway analyses to understand their biological functions using advanced bioinformatics methods including UMAP, t-SNE for dimensionality reduction. We focus on key signaling pathways, with attention to the TGF-beta pathway that plays important roles in cell proliferation, differentiation and tumorigenesis.

We also discuss cell-cell interaction networks to explore the interactions between different types of cells present in the tumor. Here, you showcase the MIF signaling network and its quantifying capability of linked immune responses that coordinates in the tumor microenvironment. Pseudotime analysis is used to backtrack the differentiation trajectories of cells; hence, it reflects the temporal dynamics during tumor evolution. Utilizing multiple machine learning modelto characterize classification of different pattern of gene expression and therefore defining molecular mechanisms behind chondrosarcoma. Such an integrated strategy illuminates the complex intercellular networks and pinpoint their aberrant components as potential therapeutic targets, shedding new light on precision medicine of chondrosarcoma. In so doing, we hope this study will add to the growing body of knowledge on chondrosarcoma and lead to more effective targeted therapies that ultimately improve patient outcomes as well as establish a basis for further research in this field.

Methods

Data resource and preparation

The Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) datasets related to Chondrosarcoma were obtained from the NCBI [7] and Gene Cards (https://www.genecards.org) [8].

Differential expression gene analysis (DEG identification)

Comprehensive RNA sequencing data were accessed through the Genomic Data Commons (GDC) Data Portal of The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA). The analytical cohort comprised 161 experimental chondrosarcoma (EC) specimens and 11 non-malignant control (HC) samples. Gene identifier conversion was performed using the org.Hs.eg.db annotation package within the R environment, yielding expression measurements for 35,635 distinct gene symbols. The limma statistical framework was employed for data normalization via the voom transformation, followed by comparative differential expression assessment between EC and HC groups. Genes demonstrating statistically significant expression alterations (adjusted p-value < 0.05) with substantial magnitude changes (absolute log2FoldChange exceeding 1) were classified as differentially expressed genes (DEGs). The distribution of these expression changes was visualized using volcano plot methodology implemented through the ggplot2 visualization library, with statistical significance (− log10 of adjusted p-values) plotted against effect size (log2FoldChange) [9–11].

Protein–protein interaction (PPI) network construction

To characterize the functional relationships among differentially expressed genes, the identified DEGs were submitted to the Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes/Proteins (STRING) database for interactome mapping. Network construction employed a stringent confidence threshold (interaction score ≥ 0.7) to prioritize high-confidence molecular associations. Topological analysis of the resultant protein-protein interaction (PPI) network was conducted using the CytoHubba plugin within the Cytoscape network visualization platform. The Maximal Clique Centrality (MCC) algorithm was applied to identify and prioritize hub genes representing central regulatory nodes within the interaction network [12–14].

Multi-omics data analysis establishment of a prognosis prediction model

As a result, we further compared the gene expression(GSE24369 and GSE22855) by using p-value < 0.05 and |log2FC| > 1 as significance threshold. The actual disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS) time were used to evaluate the prognosis of lung adenocarcinoma patients. We then built a prognostic prediction model by integrating multi-omics data, as shown in Fig. 1. These omics datasets include gene expression (RNA and miRNA), somatic mutations (WES) and methylations. Prognostic model was developed by first univariate Cox proportional hazard regression analysis of overall survival (using “survival” package in R) based on individual differential gene expression, mutations, or methylation. Secondly, lasso regression was conducted for the selected features (p-value < 0.05) using package “glmnet” to remove less informative variables. The next step was the using of multivariable Cox proportional hazard regression with a stepwise algorithm for identifying some variables to construct a prognosis signature and calculating risk scores for all samples based on this model. The patients with occurrence probabilities above the median risk score were divided into high-risk, while those below the median were low-risk group, and their outcomes about overall survival was compared [15–17].

Fig. 1.

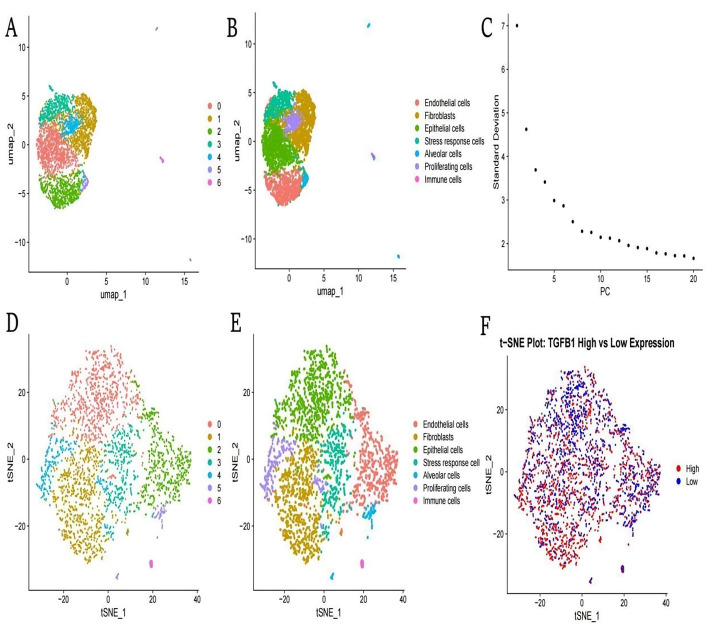

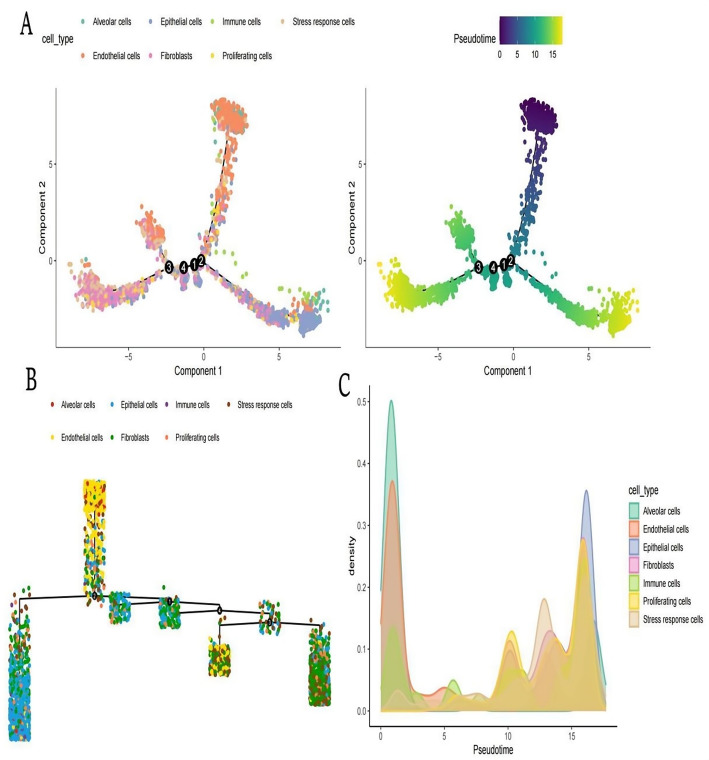

Various analyses of cell populations using dimensionality reduction techniques. A and B: UMAP visualization separates tumor cells into distinct clusters (endothelial, fibroblasts, epithelial, stress response, alveolar, proliferating, and immune cells). C: PCA scree plot showing variance contribution of principal components. D and E: t-SNE projections providing alternative visualization of cell subtype distribution. F: t-SNE map highlighting TGFB1 expression patterns, with red indicating high expression and blue showing low expression across different cell populations

Single-cell level validation

The analysis of single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) data from accession GSM5578183 was performed using the Seurat computational framework implemented in the R programming environment. Rigorous quality control parameters were applied to ensure data integrity, excluding low-quality cells with feature detection below 200 genes and those exhibiting mitochondrial transcript contamination exceeding 20%. To minimize technical variability across experimental batches, a comprehensive integration strategy was implemented to harmonize data from multiple samples while preserving underlying biological heterogeneity. Transcript abundance values were subjected to logarithmic normalization prior to unsupervised hierarchical clustering. Dimensionality reduction was accomplished through complementary approaches, including principal component analysis (PCA) for initial variance decomposition, followed by t-Distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (t-SNE) for non-linear projection and visualization of cellular relationships in two-dimensional space [18–20]. We identified 2000 highly variable genes using the ‘vst’ method to capture genes exhibiting high cell-to-cell variation, which likely represent biologically meaningful heterogeneity. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was performed on these variable features, with the first 30 principal components selected for downstream analyses based on elbow plot examination and permutation-based significance testing (p < 0.001).For integration of data from multiple samples, we employed Seurat’s canonical correlation analysis (CCA) approach to identify anchors between datasets, followed by batch effect correction using the ‘IntegrateData’ function. This integration strategy preserved biological variability while removing technical artifacts associated with different experimental batches.Unsupervised graph-based clustering was implemented using the Louvain algorithm with a resolution parameter of 0.8, optimized through silhouette width analysis to achieve balanced cluster granularity. For visualization, both t-Distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (t-SNE) and Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) dimensionality reduction techniques were applied to embed cells in two-dimensional space, using the previously identified principal components as input features. The ‘SingleR’ package (v1.8.1) facilitated automated cell type annotation by leveraging reference transcriptomic profiles from the Human Primary Cell Atlas and Blueprint/ENCODE datasets. This reference-based annotation approach was complemented by manual curation using established lineage-specific markers. For identification of cluster-specific marker genes, we utilized the ‘FindAllMarkers’ function with the following parameters: minimum percentage of cells expressing the gene within a cluster (min.pct = 0.25), minimum log fold-change threshold (logfc.threshold = 0.25), and Wilcoxon rank-sum test with Bonferroni correction for multiple testing (p_adj < 0.05). Top markers for each cluster were visualized using violin plots, feature plots, and heatmaps to validate cell type assignments and characterize cluster-specific expression patterns.

Results

Various analyses of cell populations using dimensionality reduction techniques

Figure 1A and B display the clustering of different cell types using the UMAP (Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection) method. Cells are grouped into distinct clusters, each representing a different cell type, such as endothelial cells, fibroblasts, epithelial cells, stress response cells, alveolar cells, proliferating cells, and immune cells. Figure 1C shows the standard deviation across the principal components (PCs), indicating the variance explained by each component. The graph helps identify the most significant components, with the first few PCs explaining the majority of the variance. Figure 1D and E use t-SNE to visualize the distribution of cell types in a lower-dimensional space. Similar to the UMAP plots, cells are color-coded by type, showing a different perspective on the clustering and relationships between cell types. Figure 1F highlights the expression levels of TGFB1 across the cell populations. Cells with high TGFB1 expression are marked in red, while those with low expression are in blue, demonstrating the variability in expression levels among different cells.

Gene ontology (GO) and pathway analysis

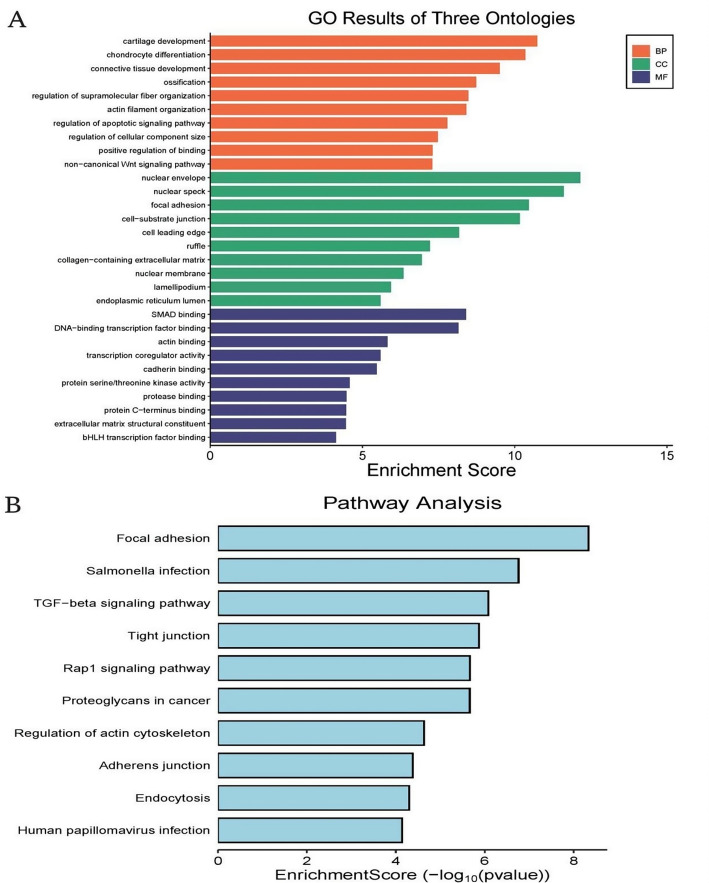

BP (Biological Process): This category includes processes such as cartilage development, chondrocyte differentiation, and connective tissue development, indicating involvement in tissue formation and organization. CC (Cellular Component): Enriched terms include nuclear envelope, nuclear speck, and focal adhesion, pointing to cellular structures involved in signaling and structural integrity.MF (Molecular Function): Terms like DNA-binding transcription factor binding, actin binding, and cadherin binding suggest roles in gene regulation and cell adhesion (Fig. 2A).The analysis identifies key pathways such as focal adhesion, TGF-beta signaling, and regulation of the actin cytoskeleton, which are crucial for cell communication, structural dynamics, and signaling processes.Other pathways like Salmonella infection and human papillomavirus infection highlight potential interactions with pathogens. The enrichment score (− log10(p-value)) indicates the statistical significance of each pathway, with higher values representing more significant enrichment (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

Gene ontology (GO) and pathway analysis. A: Gene Ontology classification reveals enriched biological processes centered on cartilaginous tissue formation and chondrocyte maturation; cellular components predominantly associated with nuclear architecture and cell-matrix contact points; and molecular functions primarily involving SMAD-mediated transcriptional regulation and cytoskeletal protein interactions. B: KEGG pathway analysis identifies significant enrichment of cellular mechanisms governing cell-matrix interactions, TGF-beta-mediated signal transduction, and intercellular junction integrity

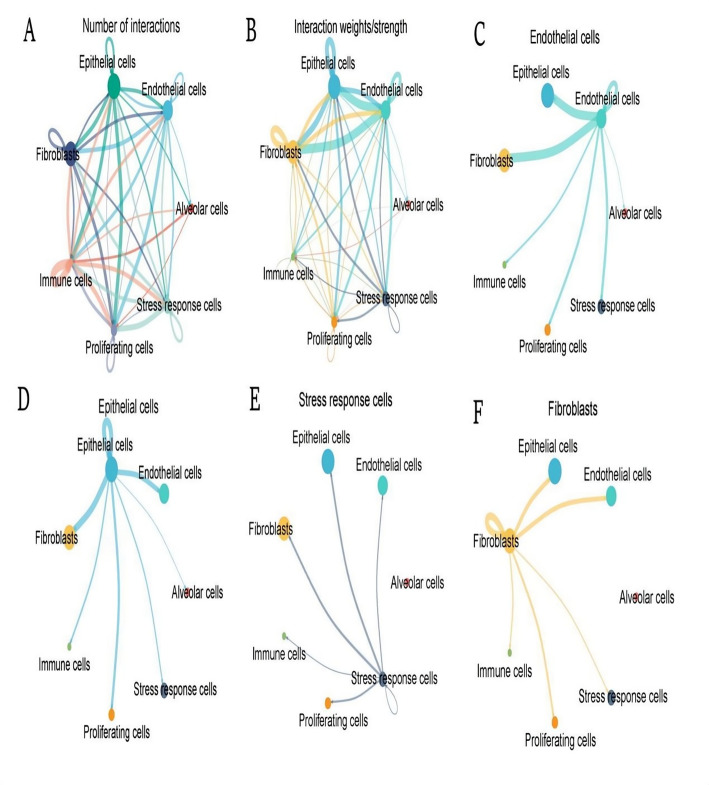

Cell–cell interaction networks among different cell types

This network shows the overall number of interactions between different cell types, with thicker lines indicating more interactions. Epithelial cells, endothelial cells, and fibroblasts appear to have numerous connections with other cell types, suggesting a central role in cell communication (Fig. 3A).The thickness of the lines represents the strength of interactions, with thicker lines indicating stronger interactions. Endothelial and epithelial cells have strong interactions with multiple cell types, emphasizing their importance in maintaining tissue integrity and function (Fig. 3B).This network focuses on endothelial cells and their interactions. Endothelial cells have significant interactions with epithelial cells and fibroblasts, indicating their role in supporting vascular and tissue structures (Fig. 3C). Epithelial cells are shown to interact primarily with endothelial cells and fibroblasts. These interactions are crucial for barrier functions and tissue organization (Fig. 3D).Stress response cells interact with various cell types, including endothelial and epithelial cells. These interactions may be involved in cellular responses to stress and injury (Fig. 3E). Fibroblasts show interactions with several cell types, particularly epithelial and endothelial cells. This highlights their role in extracellular matrix production and tissue repair (Fig. 3F).

Fig. 3.

Cell–cell interaction networks among different cell types. A: Network diagram quantifying the frequency of intercellular interactions, with connection thickness representing communication abundance between distinct cellular populations. B: Weighted interaction map illustrating the relative strength and significance of cell-cell communications, with edge intensity proportional to interaction magnitude. C–F: Cell type-specific interaction networks highlighting the unique communication patterns of endothelial cells (C), epithelial cells (D), stress response cells (E), and fibroblasts (F), demonstrating their differential connectivity within the tumor ecosystem

MIF signaling pathway network

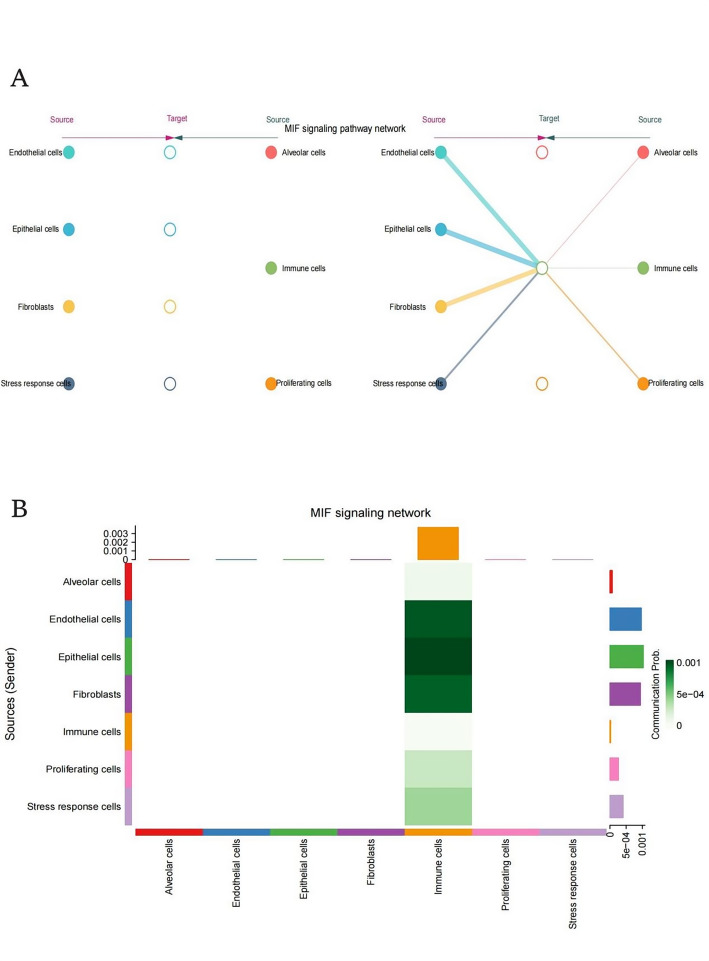

This diagram shows the directional interactions within the MIF signaling network. Lines connect various cell types, indicating pathways where MIF signaling is active. Key interactions are highlighted between Endothelial cells and epithelial cells, fibroblasts and immune cells, stress response cells and proliferating cells. The thickness and color of the lines may represent the strength or significance of these interactions (Fig. 4A).

Fig. 4.

MIF signaling pathway network. A: Directional network visualization depicting the MIF-mediated signaling architecture, illustrating the complex interplay and information flow between diverse cellular constituents within the tumor microenvironment. B: Heatmap representation of intercellular communication probabilities within the MIF signaling axis, with color intensity corresponding to interaction likelihood and highlighting the central role of immune cell populations in orchestrating this signaling cascade

This bar graph represents the communication probability between different cell types within the MIF signaling network. The y-axis lists the source (sender) cell types, such as alveolar cells, endothelial cells, etc. The x-axis represents the target cell types.The color intensity corresponds to the probability of communication, with darker shades indicating higher probabilities.Notably, immune cells show significant communication with various other cell types, suggesting a central role in the MIF signaling network (Fig. 4B).

Analysis of cell differentiation and progression using pseudotime

Pseudotime trajectory plots Shows cell types distributed in a reduced dimensional space using components 1 and 2. Different colors represent various cell types, such as alveolar cells, epithelial cells, immune cells, etc. Right plot displays the same cells colored by pseudotime, a measure indicating the progression of cells along a differentiation path. The color gradient from yellow to purple represents the progression from early to late pseudotime (Fig. 5A).This visualization depicts a branching structure, representing the progression paths of cells.Each branch indicates a potential differentiation path, with different cell types positioned along these paths. The connections between branches suggest transitions or relationships between different cell states (Fig. 5B).This plot shows the density distribution of different cell types across pseudotime. Peaks indicate where certain cell types are more prevalent along the pseudotime trajectory. The distribution helps identify stages in the differentiation process where specific cell types are more dominant (Fig. 5C).

Fig. 5.

Analysis of cell differentiation and progression using pseudotime. A: Dual representation of cellular states showing spatial distribution of identified cell types (left) and their developmental progression along inferred pseudotime continuum (right), with color gradient reflecting temporal advancement. B: Branching trajectory map revealing the multidirectional differentiation pathways and developmental decision points governing cellular fate determination within the tumor. C: Density distribution analysis displaying the relative abundance of distinct cellular populations across the pseudotemporal continuum, highlighting stage-specific enrichment patterns throughout differentiation progression

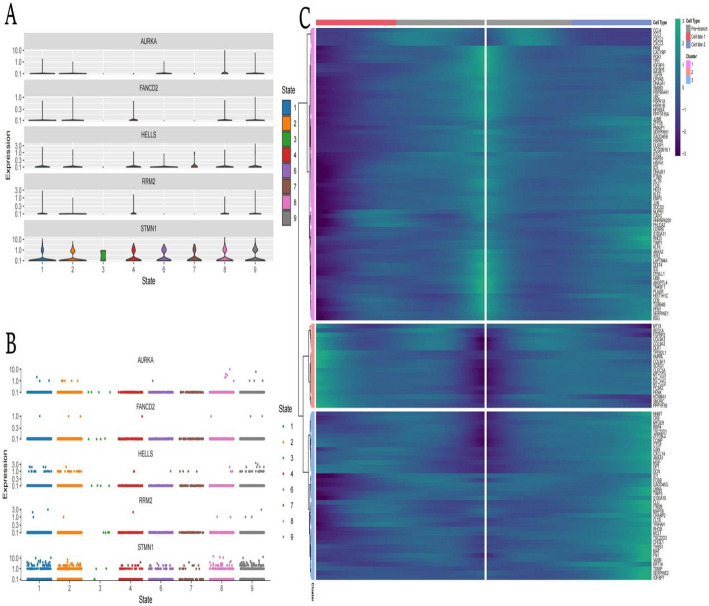

Gene expression analysis across different cell States

Violin plots of gene expression displays the expression levels of genes (AURKA, FANCD2, HELLS, RRM2, STMN1) across various cell states.Each violin plot shows the distribution and density of gene expression, with wider sections indicating higher frequency of cells expressing at those levels. Different colors represent distinct cell states, illustrating how expression varies across states (Fig. 6A). Dot plots of gene expression shows individual gene expression levels as dots for each cell state. Each dot represents a cell, with its position indicating the expression level of a specific gene. This plot provides a granular view of how expression varies within and between cell states (Fig. 6B). Heatmap of gene expression visualizes the expression of a large set of genes across different cell types and clusters. Rows represent genes, and columns represent cell types or clusters. The color intensity indicates expression levels, with brighter colors representing higher expression. The heatmap is divided into clusters, suggesting groups of genes with similar expression patterns across cell types (Fig. 6C).

Fig. 6.

Gene expression analysis across different cell states. A: Violin plot visualization capturing the distribution and variability of key regulatory genes (AURKA, FANCD2, and others) across distinct cellular states, with width indicating expression frequency at each intensity level. B: Scatter plot representation detailing the cell-by-cell expression patterns of signature genes across different cellular states, revealing both population-level trends and single-cell heterogeneity. C: Hierarchical clustering heatmap illustrating comprehensive gene expression patterns across cellular states and phenotypic categories, with color intensity reflecting relative expression levels and revealing coordinated transcriptional programs characteristic of each cell population

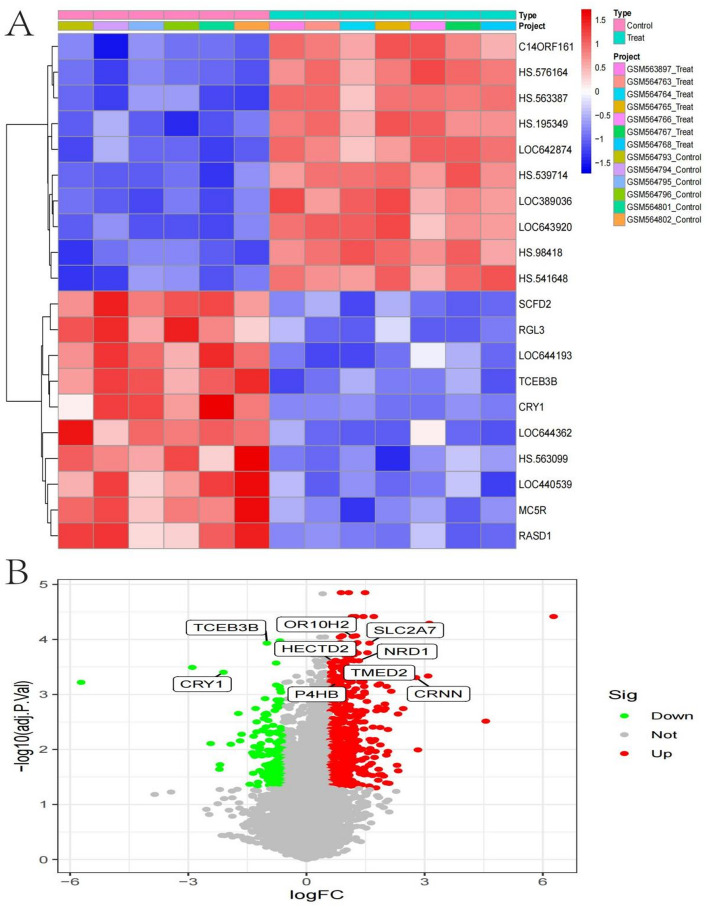

Differences between treated and control groups

Heatmap of gene expression displays the expression levels of various genes across samples. Rows represent genes, and columns represent individual samples, categorized into “Control” and “Treat” groups. Color intensity indicates expression levels, with red representing higher expression and blue indicating lower expression. The clustering on the left groups genes with similar expression patterns, showing distinct expression profiles between treated and control samples (Fig. 7A). Volcano plot illustrates the differential expression of genes between treated and control groups.The x-axis represents the log fold change (logFC) in expression, with positive values indicating upregulation and negative values indicating downregulation in the treated group.The y-axis represents the negative log10 of the adjusted p-value, indicating statistical significance. Red dots represent significantly upregulated genes, green dots represent significantly downregulated genes, and gray dots represent non-significant changes. Labeled genes, such as TCEB3B, CRY1, and P4HB, are those with notable changes in expression and significance, indicating potential key players in the treatment response (Fig. 7B).

Fig. 7.

Differences between treated and control groups. A: Hierarchically clustered heatmap visualization comparing transcriptional profiles between experimental conditions, with columns representing individual samples (control versus treated) and rows depicting gene expression patterns, where color intensity corresponds to relative expression levels. B: Statistical visualization of gene expression alterations following treatment, plotting fold change against significance level, with significantly upregulated transcripts highlighted in red and downregulated genes in green, revealing key molecular targets responsive to intervention

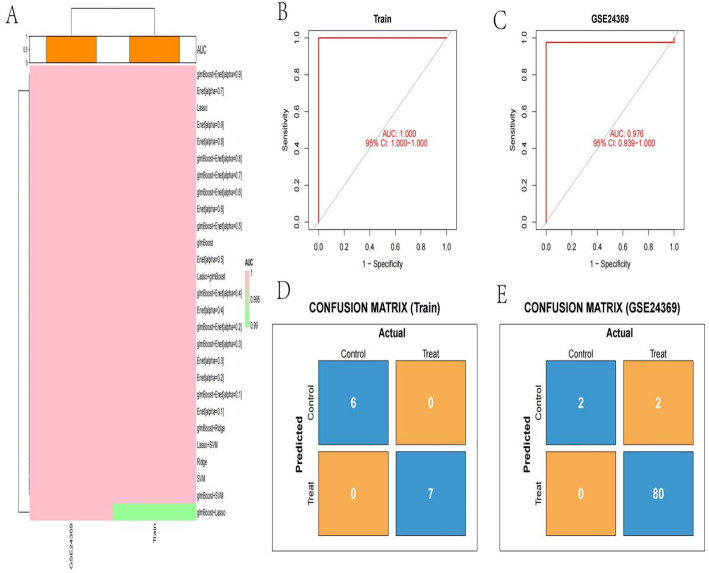

Analysis of model performance using different datasets

Heatmap of model performance displays the Area Under the Curve (AUC) values for various models across different datasets.Rows represent different models, while columns represent datasets (Train and GSE24369). The color intensity indicates AUC values, with pink showing high performance and green showing lower performance (Fig. 8A). Models with higher AUC values are more effective at distinguishing between classes. ROC curve for training set shows the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve for the training dataset. The curve plots sensitivity (true positive rate) against 1-specificity (false positive rate). An AUC of 1.000 indicates perfect classification performance, with the curve hugging the top-left corner (Fig. 8B). ROC curve for GSE24369 dataset is similar to the training set, this ROC curve evaluates the model on the GSE24369 dataset. An AUC of 0.976 indicates high classification accuracy, with a slight drop compared to the training set. The 95% confidence interval (CI) suggests the reliability of this performance measure (Fig. 8C). Confusion matrix for rraining set displays the predicted vs. actual classifications for the training data. The matrix shows perfect classification, with all control and treat samples correctly identified (6 control, 7 treat) (Fig. 8D). Confusion matrix for GSE24369 dataset shows the predicted vs. actual classifications for the GSE24369 dataset. The model correctly identifies most treat samples (80), with slight misclassification in control samples (2 misclassified as treat) (Fig. 8E).

Fig. 8.

Analysis of model performance using different datasets. A: Color-coded heatmap representation comparing area under the curve (AUC) metrics across various modeling approaches and datasets, with intensity reflecting classification performance. B: Receiver operating characteristic curve for the training dataset demonstrating optimal discrimination capability with perfect AUC (1.000), indicating complete separation between classes. C: External validation performance on the GSE24369 dataset showing robust generalizability with near-perfect discrimination (AUC: 0.976). D: Binary classification outcome matrix for the training cohort showing flawless categorization of all samples into their respective experimental groups. E: Validation cohort classification matrix revealing high predictive accuracy with minimal misassignments, confirming model reliability across independent datasets

Comprehensive analysis of gene expression and pathway enrichment

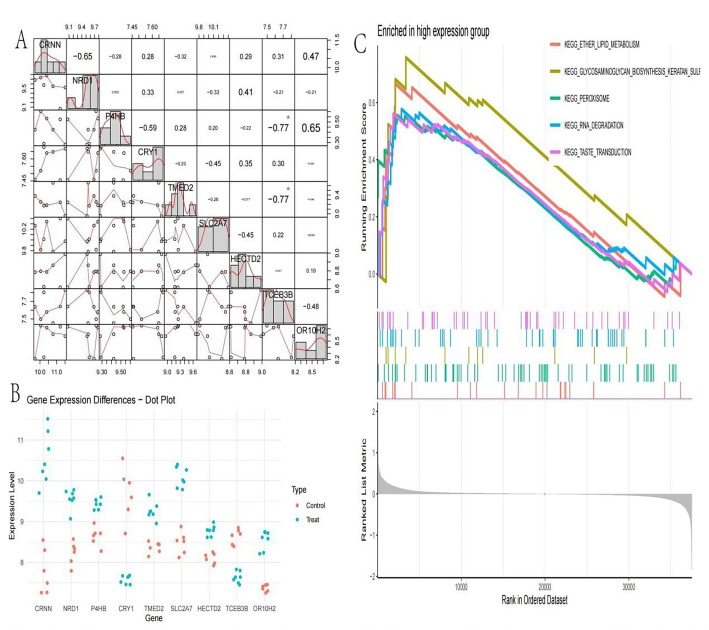

Pairwise correlation matrix displays correlations between the expression levels of various genes. Each cell shows the correlation coefficient between two genes, with positive values indicating direct correlation and negative values indicating inverse correlation. Scatter plots within the cells visualize the relationships, with lines indicating the trend. Notable correlations include strong positive or negative relationships, such as between P4HB and CRY1 (Fig. 9A). Gene expression differences illustrates the expression levels of specific genes in control and treated groups.Each dot represents a sample, with red for control and blue for treated. Differences in expression levels between groups can be observed, indicating potential treatment effects on genes like CRNN and TCEB3B (Fig. 9B). Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) shows enrichment of pathways in the high expression group. The running enrichment score indicates the degree of overrepresentation of gene sets as you move down the ranked list of genes. Pathways such as KEGG_ETHER_LIPID_METABOLISM and KEGG_PEROXISOME are enriched, suggesting biological processes influenced by high expression levels. The bottom plot shows the ranked list metric, highlighting where genes contributing to the enrichment are located (Fig. 9C).

Fig. 9.

Comprehensive analysis of gene expression and pathway enrichment. A: Pairwise correlation matrix integrating scatter plots and coefficient values to visualize the strength and directionality of relationships between expression profiles of key regulatory genes. B: Comparative dot plot illustration contrasting gene expression distributions between experimental conditions, with individual data points representing sample-specific measurements and color coding distinguishing control from treatment groups. C: Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) plot demonstrating systematic enrichment of specific KEGG pathways associated with high expression phenotypes, with the enrichment score profile (top) reflecting cumulative enrichment and the ranked gene list metric (bottom) indicating the distribution of pathway members across the expression spectrum

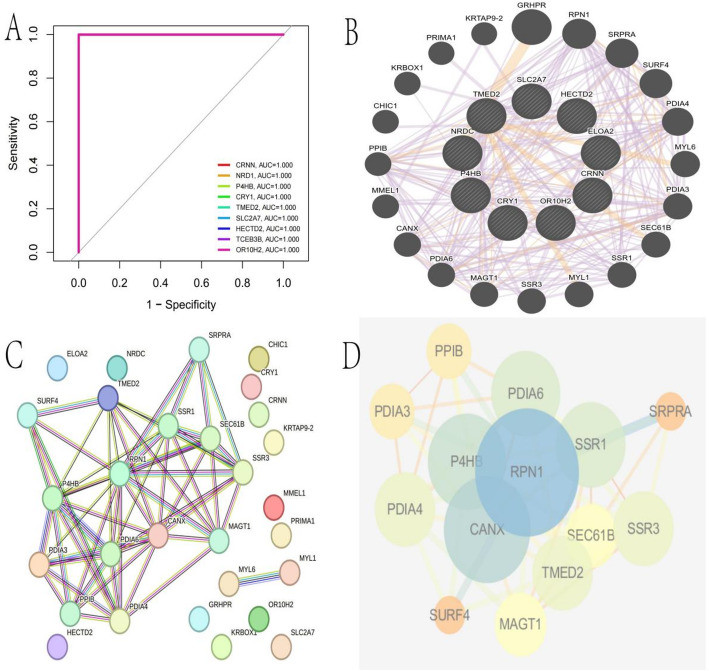

Analysis of gene interactions and model performance

ROC curve displays the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves for multiple genes. The curves show perfect classification performance with an Area Under the Curve (AUC) of 1.000 for all listed genes, indicating high sensitivity and specificity (Fig. 10A). Gene interaction network illustrates interactions between various genes, represented as nodes.Edges (lines) between nodes indicate interactions, with thicker lines suggesting stronger or more significant connections. Central genes like TMED2, SLC2A7, and HECTD2 have numerous connections, indicating their potential importance in the network (Fig. 10B). Protein-protein interaction network shows a detailed view of protein interactions, with nodes representing proteins and edges indicating interactions. The network highlights clusters of proteins, suggesting functional groups or complexes. Key proteins like RPN1, P4HB, and CANX are central, possibly playing crucial roles in cellular processes (Fig. 10C). Clustered network visualization provides a simplified view of the interaction network, highlighting major clusters or modules. Larger nodes represent more connected or influential proteins within the network. This visualization helps identify core components and their interactions within the biological system.

Fig. 10.

Analysis of gene interactions and model performance. A: ROC curves showing perfect classification capability (AUC = 1.000) for all candidate biomarker genes. B: Gene interaction network illustrating functional relationships between differentially expressed genes. C: Protein-protein interaction map visualizing physical associations between key proteins identified in the study. D: Clustered network representation highlighting functional modules within the larger interaction network

Discussion

Widespread chondrosarcoma single cell RNA sequencing has revealed the tumor’s cellular and molecular complexities. Ongoing single-cell resolution analysis of chondrosarcoma will reveal further the complex biology as would be anticipated and we emphasize here that the information provided can supersede and capture substantial heterogeneity within this important tumour. This heterogeneity is significant, as it affects tumor behavior, treatment response and prognosis for the patient. Perhaps the most compelling discovery is signalling through the TGF-beta pathway. TGF-beta is a multifunctional cytokine that plays different roles in cancer depending on the context, functioning as a tumor suppressor in normal cells and one of the promotes tumor progression at cancerous cells [21–24]. Chondrosarcoma data indicate that TGF-beta promotes connectivity between different cellular compartments which might aid in tumorigenesis and spread. Disruption of these interactions can be achieved by targeting this pathway, making it a clear and appropriate therapeutic target. Inhibitors of TGF-beta signaling may be evaluated in future studies for their potential therapeutic use in decreasing tumor burden and metastasis.

The analysis of MIF signaling network highlights the important function of immune cells within chondrosarcoma microenvironment. Therefore, immune cells including macrophages and T-cells play a key role in the conversation of tumor influencing its development and response to treatment [25–27]. This discovery is consistent with the increasing interest around immunotherapy as a therapeutic option for many different cancers. It could be potentially beneficial to modulate immune response by complementary approaches with the aim of improving current treatments or establishing new immunotherapeutics for chondrosarcoma.

A pseudo-time analysis has offered an alternative dynamic view into the differentiation state of a cell and its progression within the tumor [28]. The mapping of these trajectories in tumor cells provides us information on how cancer cells develop and adapt over time. Knowing this is important for recognizing key points of intervention, at which therapeutic approaches might be optimally effective. One of the other things that studying these pathways gives you is a better understanding of how this will progress or, potentially, how to provide treatment plans specific to an individual patient.

Our integration of machine learning models within this study has provided a valuable approach to validate gene expression patterns and increase our molecular understanding of the etiology of chondrosarcoma. The remarkable classification accuracy obtained by these models shows their importance in enhancing cancer diagnosis and individualizing treatment strategies. Furthermore, machine learning can be employed to make predictive models on patient outcomes from gene expression profiles which might help in the design of precision medicine approaches. While our comprehensive bioinformatic analysis has significantly advanced the understanding of chondrosarcoma heterogeneity, several crucial steps remain before clinical translation becomes feasible. The molecular targets we’ve identified through single-cell sequencing and computational approaches require rigorous validation through prospective clinical investigations. Such validation studies would need to systematically evaluate the therapeutic potential of modulating the TGF-beta signaling pathway and other key networks highlighted in our analysis.

Limitation

A critical limitation of our current work is the relatively homogeneous patient cohort examined. Expanding our analytical framework to encompass a more diverse patient population including variations in age, gender, ethnicity, tumor grade, and anatomical location would likely reveal additional dimensions of molecular heterogeneity with important therapeutic implications. Such expanded analysis could potentially identify distinct molecular subtypes of chondrosarcoma that might respond differentially to targeted interventions.

Our integrated multi-omics approach has nonetheless provided unprecedented insights into the molecular architecture of chondrosarcoma, particularly regarding the complex interplay between various cell populations within the tumor microenvironment. By delineating the aberrant signaling networks and proliferative mechanisms that drive tumor progression, we have established a foundation for developing innovative therapeutic strategies that specifically target the molecular vulnerabilities of chondrosarcoma cells. The convergence of computational biology, machine learning algorithms, and protein-centric analyses presented in this study represents a significant step toward precision oncology approaches for this challenging malignancy, potentially offering new avenues for improving clinical outcomes in patients who currently have limited treatment options.

Conclusions

This comprehensive analysis uncovers the cellular heterogeneity and complex intercellular networks in chondrosarcoma, elucidating critical molecular pathways and identifying novel therapeutic targets. By integrating gene expression, signaling networks, and advanced computational methods, this study contributes to the broader understanding of cancer biology and highlights the potential for precision medicine strategies in treating chondrosarcoma.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all colleagues from the Department of Spine Surgery, The Third Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University, for their assistance and support during this research.

Author contributions

Hui Xie conceptualized the study and provided overall supervision and guidance. Shengke Li and Junteng Chen performed the bioinformatics analyses and drafted the initial manuscript. Fuping He and Maosheng Wang contributed to the data acquisition, statistical analysis, and interpretation. Jun Liu assisted in refining the research methodology and critical revision of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82104887) and the Major Science and Technology Project of Traditional Chinese Medicine in Guangzhou (No. 2025CX002).

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study did not involve any human participants or animal subjects, and therefore ethical approval is not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Al-Mourgi M, Shams A. A rare entity of the anterior chest cage rib chondrosarcoma: a case report and review of literature. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2024. 10.1053/j.semtcvs.2024.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gao Z, Dai Z, Ouyang Z, Li D, Tang S, Li P, et al. Radiomics analysis in differentiating osteosarcoma and chondrosarcoma based on T2-weighted imaging and contrast-enhanced T1-weighted imaging. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):26594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Musser ML, Meritet D, Viall AK, Choi E, Willcox JL, Mathews KG. Prognostic impact of a histologic grading scheme in dogs diagnosed with rib chondrosarcoma. Vet Comp Oncol. 2024. 10.1111/vco.13025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li J, Bai Y, Zhang H, Chen T, Shang G. Single-cell RNA sequencing reveals the communications between tumor microenvironment components and tumor metastasis in osteosarcoma. Front Immunol. 2024;15:1445555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu WN, Harden SL, Tan SLW, Tan RJR, Fong SY, Tan SY, et al. Single-cell RNA sequencing reveals anti-tumor potency of CD56(+) NK cells and CD8(+) T cells in humanized mice via PD-1 and TIGIT co-targeting. Mol Ther. 2024;32:3895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang Y, Zhang Y, Pan C, Wang W, Yu Y. HPV-driven heterogeneity in cervical cancer: study on the role of epithelial cells and myofibroblasts in the tumor progression based on single-cell RNA sequencing analysis. PeerJ. 2024;12:e18158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clough E, Barrett T. The gene expression omnibus database. Stat Genomics: Methods Protocols. 2016;1418:93–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jabari M, Izci D, Ekinci S, Bajaj M, Zaitsev I. Performance analysis of DC-DC Buck converter with innovative multi-stage PIDn(1 + PD) controller using GEO algorithm. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):25612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davis BE, Gauvreau GM. The ABCs and DEGs (Differentially expressed Genes) of airway hyperresponsiveness. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2023;207(12):1545–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Farhadi A, Tang S, Huang M, Yu Q, Xu C, Li E. Identification of key overlapping DEGs and molecular pathways under multiple stressors in the liver of nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Comp Biochem Physiol Part D Genomics Proteom. 2023;48:101152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jia X, Wu J, Chen X, Hou S, Li Y, Zhao L, et al. Cell atlas of trabecular meshwork in glaucomatous non-human primates and DEGs related to tissue contract based on single-cell transcriptomics. iScience. 2023;26(11):108024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ariawan D, Thananthirige KPM, El-Omar A, van der Hoven J, Genoud S, Stefen H, et al. Design of peptide therapeutics as protein-protein interaction inhibitors to treat neurodegenerative diseases. RSC Adv. 2024;14(47):34637–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Germany E, Shiota T. Analysis of protein-protein interaction of the mitochondrial translocase at work by using technically effective BPA photo-crosslinking method. Methods Enzymol. 2024;707:237–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sreenithya KH, Sugumar S. Protein-protein interaction network study of metallo-beta-lactamase-L1 present in Stenotrophomonas maltophilia and identification of potential drug targets. Silico Pharmacol. 2024;12(2):94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen H, Xu J, Zhang Q, Chen P, Liu Q, Guo L, et al. Machine learning-based prediction of 5-year survival in elderly NSCLC patients using oxidative stress markers. Front Oncol. 2024;14:1482374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dev I, Mehmood S, Pleshko N, Obeid I, Querido W. Assessment of submicron bone tissue composition in plastic-embedded samples using optical photothermal infrared (O-PTIR) spectral imaging and machine learning. J Struct Biol X. 2024;10:100111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Poupard M, Best P, Morgan JP, Pavan G, Glotin H. A first vocal repertoire characterization of long-finned pilot whales (Globicephala melas) in the mediterranean sea: a machine learning approach. R Soc Open Sci. 2024;11(11):231973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen Y. Dissecting L-glutamine metabolism in acute myeloid leukemia: single-cell insights and therapeutic implications. J Transl Med. 2024;22(1):1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang X, Li D, Zhu B, Hua Z. Single-cell transcriptome analysis identifies a novel tumor-associated macrophage subtype predicting better prognosis in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2024;12:1466767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Watanabe H, Rana M, Son M, Chiu PY, Fei-Bloom Y, Choi K, et al. Single cell RNA-seq reveals cellular and transcriptional heterogeneity in the Splenic CD11b(+)Ly6C(high) monocyte population expanded in sepsis-surviving mice. Mol Med. 2024;30(1):202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seok Han B, Ko S, Seok Park M, Ji Lee Y, Eun Kim S, Lee P, et al. Lidocaine combined with general anesthetics impedes metastasis of breast cancer cells via inhibition of TGF-beta/Smad-mediated EMT signaling by reprogramming tumor-associated macrophages. Int Immunopharmacol. 2024;142:113207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wyatt MM, Paulos CM. A paradigm shift in tumor immunology: Th17 cells and TGF-beta in intestinal cancer initiation. Cancer Res. 2024. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-24-3361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yi M, Li T, Niu M, Wu Y, Zhao B, Shen Z, et al. Blockade of CCR5(+) T cell accumulation in the tumor microenvironment optimizes anti-TGF-beta/PD-L1 bispecific antibody. Adv Sci (Weinh). 2024;11:e2408598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhou Q, Breitkopf-Heinlein K, Gaitantzi H, Birgin E, Reissfelder C, Rahbari NN. PDCD10 promotes the tumor-supporting functions of TGF-beta in pancreatic cancer. Clin Sci (Lond). 2024;138(18):1111–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Piersiala K, Hjalmarsson E, Lagebro V, Farrajota Neves da Silva P, Bark R, Elliot A, et al. Prognostic value of T regulatory cells and immune checkpoints expression in tumor-draining lymph nodes for oral squamous cell carcinoma. Front Immunol. 2024;15:1455426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tagawa T, Mahesh G, Ziegelbauer JM. Analysis of tumor infiltrating immune cells in Kaposi sarcoma lesions discovers shifts in macrophage populations. Glob Health Med. 2024;6(5):310–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wei GH, Wei XY, Fan LY, Zhou WZ, Sun M, Zhu CD. Comprehensive assessment of the association between tumor-infiltrating immune cells and the prognosis of renal cell carcinoma. World J Clin Oncol. 2024;15(10):1280–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sun J, Zhang S, Liu Y, Liu K, Gu X. Exploring tumor endothelial cells heterogeneity in hepatocellular carcinoma: insights from single-cell sequencing and pseudotime analysis. PeerJ. 2024;12:e18362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.