Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a neurodegenerative disorder characterized by amyloid plaques, neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs), and neuroinflammation. Recent research has revealed that pyroptosis, an inflammatory programmed cell death (PCD), plays a crucial role in AD pathology. The pyroptosis signaling cascade triggered by β-amyloid (Aβ) and hyperphosphorylated tau protein leads to the release of proinflammatory cytokines, forming a “neuroinflammation-neurodegeneration” vicious cycle. Therapeutic strategies targeting the pyroptosis signaling pathway show promise, with evidence suggesting that inhibition of inflammasomes, caspase-1, or gasdermin D (GSDMD) can alleviate AD-related pathological features. However, the specificity of the existing inhibitors is insufficient, and research on non-classical pyroptosis pathway remains in its early stages. More mechanisms and therapeutic strategies targeting pyroptosis-related pathway need to be explored to enhance the therapeutic efficacy. Targeting the pyroptosis pathway provides a novel direction for AD treatment. Exploring and summarizing its mechanisms along with the clinical translational applications of targeted inhibitors will offer fresh perspectives for moving beyond traditional “symptom control” therapies and achieving “pathology-modifying” interventions, holding significant scientific and clinical importance.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, Pyroptosis, Inflammasome, Gasdermin, Caspase

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD), a progressive neurodegenerative disorder, initially manifests as impairments in language and learning abilities and progresses to cognitive dysfunctions such as behavioral abnormalities and memory loss (Rostagno 2022). AD characterized by an insidious onset and a prolonged course, frequently progressing to severe stages before patients and their families become aware of the symptoms, making its treatment highly challenging (Better 2023). With the accelerating global aging trend, AD and related dementias exert a heavy burden on both individual and society. The pathogenesis of AD remains unknown, with its core pathological hallmarks including abnormal accumulation of β-amyloid (Aβ), tangle of hyperphosphorylated tau protein, and neuroinflammation. Abnormally activated cell death pathways exhibit cumulative effects, driving inflammatory cascades, while neuronal death and brain atrophy represent the terminal outcomes of AD pathology (Huang et al. 2024). Pyroptosis, a newly identified inflammatory form of programmed cell death (PCD), is a key driver of neuronal demise (Moujalled et al. 2021). This progress amplifies inflammation through caspase action, gasdermin D (GSDMD)-dependent signaling, and proinflammatory cytokine release (Pandey et al. 2025). Studies have shown that systemic knockout of inflammasome proteins significantly improves AD pathology in the APP/PS1 model (Heneka et al. 2013), suggesting critical roles for microglia inflammasome activation and neuronal GSDMD cleavage in AD-related neurodegeneration (Moonen et al. 2023). This article reviews recent advances in pyroptosis within AD, highlighting the clinical translational value of targeting pyroptosis inhibitors, thereby providing novel therapeutic targets for AD treatment.

Pyroptosis

The phenomenon of pyroptosis was first described in 1992. Research discovered that infection of mouse macrophages by Shigella flexneri could trigger caspase-1 activation and induce cell death (Yuan et al. 1993). In 2001, studies distinguished this cell death phenomenon induced by Shigella flexneri and Salmonella from apoptosis and formally proposed the term “pyroptosis” (Cookson and Brennan 2001; Boise and Collins 2001). During their investigation of the GSDMD protein, Shao Feng’s team uncovered the underlying mechanism by which caspase activates and recognizes GSDMD in pyroptosis. This discovery revised previous knowledge and indicated that caspase cleaves the GSDMD protein to form membrane pores, which release inflammatory mediators. GSDMD is regarded as the key executor of pyroptosis (Shi et al. 2014; Shi et al. 2015). Pyroptosis is a programmed cell death process that shares features of both necrosis and apoptosis. Pathogen signals stimulate the inflammasome complex, leading to caspase cleavage and activation of the GSDMD signaling pathway, which in turn triggers pyroptosis. Its main characteristics include cell swelling, membrane pore formation, nuclear condensation, and chromatin fragmentation. As cells swell and rupture, their contents (including proinflammatory cytokines) are released, inducing an innate immune response and ultimately resulting in loss of cell membrane integrity (Kovacs and Miao 2017; Imre 2024).

Molecular Mechanism of Pyroptosis

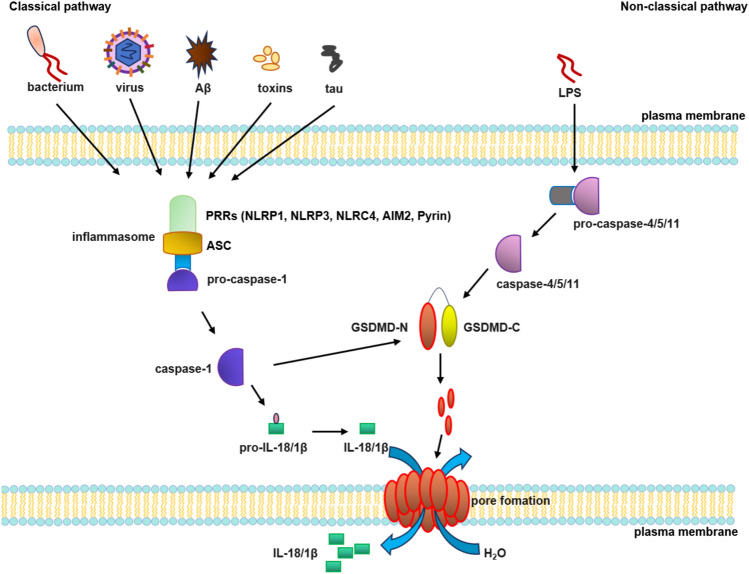

Pyroptosis is classified into classical and non-classical pathways. The classical pathway is triggered by extracellular stimulus signal, which activate innate immunity through pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) that detect pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) or damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs). These signals recruit apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a CARD (ASC) and pro-caspase-1 to assemble the inflammasome complex, ultimately activating caspase-1. On one hand, this promotes gasdermin (GSDMD) cleavage, releasing the N-terminal fragment, which forms 10–21 nm membrane pores, disrupting the cell osmotic pressure, followed by cell swelling and lysis (Zhang et al. 2018; Fang et al. 2020; Wang and Kanneganti 2021). On the other hand, caspase-1 promotes the maturation and release of IL-18 and IL-1β into the extracellular space, further triggering inflammatory responses (Yu et al. 2021). The non-classical pyroptosis pathway is induced by lipopolysaccharide (LPS), where human caspase-4/5 or murine caspase-11 recognizes and binds to LPS, subsequently cleaving GSDMD to release its N-terminal fragments (GSDMD-NT), which triggers plasma membrane pore formation. Whether caspase-4/5 can directly cleave pro-IL-1β/IL-18 remains controversial, whereas it has been demonstrated that caspase-11 lacks the ability to directly process these pro-forms. In the caspase-11-mediated non-classical pyroptosis pathway, membrane rupture induces K+ efflux, which activates the NLRP3 and caspase-1. This cascade ultimately drives the maturation and release of IL-18 and IL-1β (Man et al. 2017; Rao et al. 2022; Rühl and Broz 2015; Aglietti et al. 2016). During pyroptosis, proteins or complexes such as inflammasomes, caspases, and GSDMD play a critical role (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Molecular mechanism of pyroptosis. The classical pathway, activated by PAMPs/DAMPs, assembles ASC and pro-caspase-1 into inflammasomes. Active caspase-1 cleaves GSDMD to form membrane pores and triggers IL-18/IL-1β release. The non-classical pathway involves LPS-induced activation of pro-caspase-4/-5/-11, which cleave GSDMD to generate membrane pores, thereby promoting the release of IL-18 and IL-1β

Inflammasomes

Inflammasomes serve as critical components in innate immunity and are central to the signaling pathways that regulate pyroptosis (Wu et al. 2024). Different inflammasomes vary in their structures, mechanisms of action, and targets. PRRs participate in the formation of inflammasome complexes and are divided into two main groups according to their cellular location: membrane-bound types such as Toll-like receptors (TLRs) and C-type lectin receptors (CLRs); and intracellular types including RIG-I-like receptors (RLRs), absent in melanoma 2 (AIM2), and nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain (NOD)-like receptors (NLRs). When PRRs detect PAMPs or DAMPs, they oligomerize and recruit ASC and pro-caspase-1 to assemble inflammasomes (Kodi et al. 2024; White et al. 2017; Freeman and Ting 2016). Common inflammasomes include AIM2 inflammasome and NLR family inflammasome, with NLRP3 being the most extensively studied (Singh et al. 2023). Mechanistically, PAMP/DAMP stimulation triggers NLRP3 oligomerization, enabling ASC binding and pro-caspase-1 recruitment to form the NLRP3 inflammasome complex. This cascade controls the maturation and secretion of cytokines such as IL-18 and IL-1β, highlighting their essential role in promoting inflammatory disease processes (Dadkhah and Sharifi 2025).

Caspases

In 1993, the caspase protein related to apoptosis was first identified (Yuan et al. 1993), which initiated in-depth research on the caspase protease family. As endopeptidases, caspases act as molecular scissors, regulating biological processes by cleaving substrates. They are categorized into apoptosis-related caspases (e.g., caspase-3, -6 -7), which orchestrate programmed cell death by degrading senescent or damaged cells, and inflammatory-related caspases (e.g., caspase-1, -4 -5, -11), which mediate cytokine-driven inflammatory responses (Ramirez and Salvesen 2018; Svandova et al. 2024; Lu et al. 2020). Emerging studies further link caspases to pyroptosis, with caspase-1 activating proinflammatory cytokines IL-1β and IL-18 post-infection to directly induce lytic cell death (Vande Walle et al. 2016).

Gasdermin D

GSDMD is a member of a protein family with membrane-puncturing ability and highly homologous sequences. In 2015, Shao Feng’ team revealed that caspase-4/11 can directly recognize and cleave GSDMD, thereby triggering pyroptosis. The discovery represented the identification of a further critical substrate of inflammatory caspases following IL-1β and IL-18(Shi et al. 2015). Structurally, GSDMD comprises two functional domains: an N-terminal pore-forming domain (p30 fragment) and a C-terminal autoinhibitory domain (p20 fragment). In its inactive state, the C-terminal domain suppresses the pore-forming activity of the N-terminal domain. Caspase-mediated cleavage releases this autoinhibition, generating two fragments: GSDMD-N (p30) and GSDMD-C (p20). The liberated GSDMD-N domain binds to membrane lipids through its hydrophobic motifs, forming transmembrane pores that disrupt membrane integrity. This permeabilization event triggers osmotic imbalance, culminating in cell rupture and pyroptotic death (Aglietti et al. 2016; Chen et al. 2016; Sborgi et al. 2016; Liu et al. 2016).

Pyroptosis in Alzheimer’s Disease

Neuroinflammation, as a complex and crucial factor in the AD pathological process, is closely associated with the activation of pyroptosis and neuronal death. There is an inseparable connection between pyroptosis and AD, as evidenced by related research reports (Heneka et al. 2013; Anderson et al. 2023; Huang et al. 2022). Moreover, Aβ and hyperphosphorylated tau protein, as the main pathological markers of AD, have also been found to participate in the activation of pyroptosis (Shen et al. 2021; Saresella et al. 2016; Tan et al. 2014). Therefore, exploring the regulatory mechanism of pyroptosis in AD is conducive to clarifying the novel pathological pathways of the disease and also provides an innovative research direction for developing targeted therapeutic strategies.

Neuroinflammation and Pyroptosis

In the central nervous system (CNS), inflammatory responses to injury or infection are typically accompanied by the aggregation of glial cells. NLRP1 is predominantly expressed in neurons, while NLRP3 is mainly localized to microglia (de Rivero Vaccari et al. 2014; Kummer et al. 2007). Notably, elevated inflammasome expression observed in neurons and microglia of AD patients suggests that classical pyroptosis pathways may drive AD-related neuropathological changes (Vontell et al. 2023; Qiu et al. 2023; Cai et al. 2025). NLRP1, the first identified NOD-like receptor, forms a complex with ASC and pro-caspase-1, facilitating caspase-1 activation to promote pyroptosis and downstream inflammation (Zhang et al. 2024a). Postmortem neuropathological analyses of AD patients reveal that NLRP1 expression directly linked to the abundance of NFTs, establishing a connection between neuroinflammation and neurofibrillary pathology (Španić et al. 2022). Tan et al. demonstrated significant upregulation of NLRP1 protein levels in the hippocampal formations of APP/PS1 transgenic mice. Targeted suppression of the NLRP1/caspase-1 axis in AD mice models attenuates neuronal pyroptosis and proinflammatory cytokine release (Tan et al. 2014). Furthermore, suppressing NLRP1 and caspase-1 expression can ameliorate cognitive deficits and exerts neuroprotection (Flores et al. 2022b; Jia et al. 2024; Li et al. 2023b). Mechanistically, chronic glucocorticoid and Aβ stimulation in rat primary neurons exacerbate NLRP1-mediated neuronal damage (Yang et al. 2022). The activation or inhibition of NLRP1 has a crucial impact on cell survival and inflammatory responses, potentially participating in the regulation of AD pathological progression, making it as a potential target for AD therapy.

In APP/PS1 mice with LPS-dependent systemic inflammation, NLRP3 inflammasome activation enhances microglial phagocytic capacity to clear amyloid (Tejera et al. 2019). Furthermore, Aβ deposition is closely associated with the development of inflammasome-dependent ASCs in microglia (Friker et al. 2020). NLRP3 activation induces the production of canonical effector cytokines IL-1β and IL-18. Compared to healthy controls, the levels of proinflammatory cytokines or GSDMD in the cerebrospinal fluid, brain parenchyma, and peripheral blood of AD patients were increased (Shen et al. 2021; McManus 2022; Zhang et al. 2020; Blum-Degen et al. 1995; De Luigi et al. 2001; Torres et al. 2014; Villarreal et al. 2016; Chen et al. 2014), suggesting that NLRP3 might be involved in the pyroptosis process of AD neurons. Under physiological conditions of 4-month-old mice, NLRP3 genetic knockout can lead to impaired synaptic transmission, cognitive impairments, and anxiety-related behaviors (Komleva et al. 2021). In AD mouse models with NLRP3 or caspase-1 knockout, IL-1β secretion decreased, and AD-related symptoms were mitigated (Heneka et al. 2013; Ren et al. 2019). The drug Baicalin (BAI) can suppress NLRP3 activation, thereby mitigating microglial-mediated neuroinflammatory responses (Jin et al. 2019). A pronounced upregulation was observed in both NLRP3 and its downstream effectors IL-18/IL-1β within AD model mice. However, the use of Salidroside (Sal) can suppress the aforementioned phenomenon, thereby inhibiting pyroptosis and relieving neuroinflammation (Cai et al. 2021). These findings indicate that targeting NLRP3 can reduce the release of proinflammatory cytokines, inhibit pyroptosis, and alleviate AD neuropathy (Han et al. 2023). Both upstream inflammasome components and downstream proinflammatory mediators in the pyroptosis pathway are involved in neuroinflammatory responses in AD, and the role of pyroptosis in neuroinflammation cannot be overlooked (Xu et al. 2025).

Aβ and Pyroptosis

The “β-amyloid cascade hypothesis” establishes cerebral amyloid plaque accumulation as a central pathogenic driver in AD, triggering neurotoxic cascades through Aβ oligomerization. These plaques activate microglia, leading to neuroinflammation, synaptic loss, and even neuronal death (Paroni et al. 2019; Webers et al. 2020). Studies have shown that Aβ oligomers/fibrils bind to and activate the NLRP3 inflammasome (Nakanishi et al. 2018), which is essential for Aβ-induced caspase-1 activation and proinflammatory cytokine/chemokine secretion (Halle et al. 2008). Aβ peptide induces pyroptosis of cortical neurons via the NLRP3/caspase-1/GSDMD signaling pathway, resulting in an increase in IL-1β/IL-18. In APP/PS1 mouse models with caspase-1 or GSDMD inhibition, the Aβ-induced pyroptosis phenomenon is attenuated, and proinflammatory cytokines secretion is correspondingly reduced (Han et al. 2020b). Heneka et al. confirmed that Aβ serves as NLRP3 inflammasome primer in microglia and induces cells to transform into an inflammatory M1 phenotype, leading to increased secretion of proinflammatory cytokines and ultimately Aβ deposition and cognitive dysfunction in the hippocampus of mice. Conversely, in APP/PS1/NLRP3−/− mice, the deficiency of NLRP3 or caspase-1 causes microglia to shift to an M2 phenotype, enhancing Aβ clearance and tissue remodeling. These changes correlate with mitigated spatial memory impairment and dampened neuroinflammation (Heneka et al. 2013).

In APP/PS1 transgenic mice, the expression of NLRP1 is significantly upregulated. In vitro, Aβ can also increase NLRP1 levels in primary cortical neurons, promoting neuronal pyroptosis and proinflammatory cytokines release via the NLRP1/caspase-1 axis. Conversely, genetic ablation of NLRP1 or caspase-1 effectively suppresses neuronal pyroptosis and mitigate cognitive deficits (Tan et al. 2014). The final effector protein of pyroptosis is a member of the gasdermin family. Aβ42-induced pyroptosis depends on the NLRP3/caspase-11/GSDMD/GSDME signaling pathway, where GSDMD knockout inhibits pyroptosis and reduce Aβ deposition (Hong et al. 2023; Jha et al. 2024). Collectively, these findings indicate that Aβ potently induces pyroptosis to exacerbate AD, and molecules related to the pyroptosis pathway may serve as novel therapeutic targets for AD.

Tau and Pyroptosis

Tau is a naturally occurring unfolded microtubule-associated protein that facilitates microtubule assembly and stability. However, hyperphosphorylated tau loses its microtubule-binding capacity, triggering microtubule depolymerization. This leads to subsequent tau misfolding, aggregation into NFTs, and intraneuronal deposition, ultimately resulting in neuroinflammation, neurodegeneration, and cognitive decline (Ossenkoppele et al. 2022; Klyucherev et al. 2022; Monteiro et al. 2023). Blocking NLRP1-dependent pyroptosis reduces the activity of glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK-3β) agonists or the effects of streptozotocin (STZ), leading to a decrease in hyperphosphorylated tau (Liu et al. 2022). Panda et al. discovered that fibrillar aggregates of tau-derived PHF6 peptide (VQIVYK) upregulate NLRP3 expression in human microglia and promote the secretion of IL-1β and IL-18 (Panda et al. 2021). Murine models with tau overexpression exhibit NLRP3 activation coupled with upregulated ASC, caspase-1, and IL-1β expression (Zhao et al. 2021). Furthermore, NLRP3 inhibition enhances pericyte viability, improves cerebrovascular function, and ameliorates AD-related pathological changes in tau transgenic murine brain (Quan et al. 2024). The NLRP3 inflammasome can be activated by aggregated tau in primary microglia, accompanied by elevated IL-1β secretion that drives pyroptosis progression. Tau transgenic mice deficient in ASC or NLRP3 exhibited significant reduction in tau pathology and microglial activation (Stancu et al. 2019). These studies suggest that tau might be part of the upstream signal of NLRP3 and participate in the activation of the pyroptosis process. Supporting this paradigm, expressing human frontotemporal dementia (FTD)-mutant tau exhibits NLRP3 hyperactivation and increased ASC speck release. However, NLRP3 suppression diminishes tau hyperphosphorylation and aggregation by regulating tau kinases and phosphatases. After injecting brain homogenates containing Aβ into the hippocampus of tau22 mice, tau hyperphosphorylated, while tau22 mice with ASC or NLRP3 knockout showed significant improvement (Ising et al. 2019). This study demonstrated that amyloid deposition participates in the tau pathology procession and identifies NLRP3 inflammasome activation as a causal upstream regulator of tau-related neuropathological changes.

The interaction between tau and NLRP3 is complex. On one hand, tau protein aggregates activate NLRP3, promoting ASC formation and inflammatory cytokines expression, and exacerbating neuroinflammation in AD. On the other hand, NLRP3 activation promotes tau hyperphosphorylation and aggregation, thereby accelerating tau pathology progression (Paesmans et al. 2024). Additionally, in mice with simulated tau hyperphosphorylation in the brain, caspase-1 inhibition attenuates tau-induced neuronal damage and rescues cognitive deficits (Li et al. 2020b). Cell-based studies reveal that pyroptosis inhibition mediated by specific blocking agents in neural systems significantly alleviates tau pathology development (Baraka and ElGhotny 2010). Although the association between tau and pyroptosis has been confirmed, the specific mechanism still requires further investigation.

Therapeutic Strategies Targeting Pyroptosis for Alzheimer’s Disease

There is currently no medication that can effectively reverse the progression of AD. Given this, clinical management primarily aimed at delaying disease progression and alleviating symptoms. Targeted therapies, which intervene by addressing specific pathological mechanisms of AD, hold promise for mitigating or even preventing further disease progression. With the expanding understanding of pyroptosis-mediated regulatory networks in AD neuropathology, explorations into drug targets and their applications for pyroptosis-targeted AD treatments have been increasingly reported. Based on the assembly and activity of inflammasomes, the use of specific compounds to block their activation or interact with ASC and pro-caspase opens novel therapeutic avenues for AD intervention. Furthermore, depending on classical or non-classical pyroptosis pathways, targeted inhibition of the activation and secretion of downstream caspase, GSDMD, and inflammatory factors in the inflammasome pathway may also be an effective way to alleviate neuroinflammation in AD. In the following sections, we summarized some inhibitors and their mechanisms of action (Table 1, Fig. 2).

Table 1.

Inhibitors that target pyroptosis for AD

| Inhibitor | Class of drug | Mechanism | Significance | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NLRP3 Inhibitor | ||||

| Glyburide (GLB) | sulfonylureas | inhibition of ATP-sensitive K+ channels and NLRP3/caspase-1 signaling pathway | reducing Aβ and NFTs deposition, and alleviating neuroinflammation | (Malik et al. 2023; Ju et al. 2020) |

| JC124 | sulfonylureas | inhibition of NACHT domain of NLRP3 | reducing Aβ-induced AD pathological phenomenon | (Kuwar et al. 2019; Yin et al. 2018) |

| MCC950 | molecule compound | inhibition of ASC aggregation | alleviating pyroptosis and AD pathological phenomenon | (Dempsey et al. 2017; Li et al. 2020a; Zeng et al. 2021) |

| OLT1177 | β-sulfonyl nitrile compound | inhibition of NLRP3 and ATPase | reducing Aβ deposition and alleviating neuroinflammation | (Marchetti et al. 2018a; Marchetti et al. 2018b; Lonnemann et al. 2020) |

| Edaravone | substituted 2‐pyrazolin‐5‐ones | inhibition of NLRP3-mediated IL-1β secretion | alleviating Aβ-treated inflammation | (Wang et al. 2017) |

| CSB6B | pigment | inhibition of NLRP3 and NF-κB signal pathway | inhibiting Aβ aggregation and Aβ-induced cognitive impairments | (Yan et al. 2020) |

| Oridonin | natural products | inhibition of the cysteine 279 of NLRP3 to block the interaction between NLRP3 and NEK7 | attenuating Aβ1–42-induced synaptic loss and cognitive deficits | (Wang et al. 2016; He et al. 2018) |

| Salidroside | natural products | inhibition of TLR4/NF-κB signaling pathway or TXNIP | depressing Aβ, hyperphosphorylated tau, and alleviating the cognitive disorder | (Cai et al. 2021) |

| Caspase Inhibitor | ||||

| VX-765 | molecule compound | inhibition of caspase-1 | reducing Aβ and NFTs, and alleviating cognitive impairment | (Flores et al. 2018; Flores et al. 2020) |

| L7 | N-salicyloyl tryptamine derivatives | inhibition of NLRP3/caspase-1 signaling pathway | depressing the expression of GSDMD and protecting neuro cell | (Bai et al. 2021) |

| DJ-1 | a gene | inhibition of NLRP3/caspase-1 signaling pathway | depressing the expression of Aβ and alleviating the cognitive disorder | (Liu et al. 2017; Cheng and Zhang 2021) |

| Z-DEVD-FMK | molecule compound | inhibition of NLRP3/caspase-1 signaling pathway | reducing Alzheimer-like phenotypes | (D’Amelio et al. 2011) |

| GSDMD Inhibitor | ||||

| mafenide (MAF) | sulfonamide | inhibition of GSDMD | inhibiting neuroinflammation | (Han et al. 2020c; Han et al. 2021) |

| Necrosulfonamide (NSA) | molecule compound | inhibition of GSDMD | inhibiting Aβ1‐42‐induced pyroptosis and alleviating behavioral disorder | (Han et al. 2020b; Sun et al. 2012) |

| Disulfiram (DSF) | tetraethylthiuram disulfide | inhibition of GSDMD | reducing the production of sAPP-α and accumulation of Aβ | (Reinhardt et al. 2018; Libeu et al. 2012; Hu et al. 2020) |

| miRNA-22 | microRNA | inhibition of GSDMD | depressing the expression of Aβ and hyperphosphorylated tau, and alleviating the cognitive disorder | (Han et al. 2020a; Zhai et al. 2021) |

Fig. 2.

The mechanism of therapeutic strategies targeting pyroptosis for AD. Glyburide binds to KATP channels, MCC950 inhibits ASC oligomerization, OLT1177 suppresses the ATPase activity of NLRP3, CSB6B inhibits the NF-κB signaling pathway, Salidroside inhibits the TLR4/NF-κB pathway or TXNIP expression, and Oridonin binds with the cysteine 279 of NLRP3 in NACHT domain. All these inhibitors ultimately suppress NLRP3 expression or activation. VX-765, Z-DEVD-FMK, DJ-1, and L7 inhibit caspase-1. MAF, NecrosulfonamideDJ-1, Disulfiram, and miRNA-22 inhibit GSDMD cleavage

Therapeutic Strategies Targeting the NLRP3 Inflammasome

Glyburide

Glyburide (GLB), a sulfonylurea compound developed for type 2 diabetes treatment, was primarily characterized by its inhibitory effects on adenosine triphosphatase (ATP)-sensitive K+ (KATP) channels in pancreatic β-cells (Thévenod et al. 1992; Hardin and Jacobs 2025; Teramoto et al. 2004). Further research has shown that GLB acts upstream of cryopyrin and downstream of the P2X7 receptor, resulting in specific inhibition of NLRP3 activation pathways (Lamkanfi et al. 2009). Sadia et al. used various biophysical techniques, computational methods, and imaging tools to discover that GLB has significant potential in inhibiting amyloid plaque formation (Meeuwsen et al. 2005). In AD rat models, GLB alleviates behavioral abnormalities induced by Aβ and reduces the activity of the HPA axis (Esmaeili et al. 2018). In addition, GLB also inhibits the hyperphosphorylation of tau in the hippocampus of AD mice (Baraka and ElGhotny 2010). Ju et al. reported that GLB reduces Aβ deposition in APP/PS1 mouse hippocampus, suppresses microglial activation, and reduces IL-1β cytokine release (Ju et al. 2020). While these findings highlight GLB’s multifaceted roles, the mechanistic basis of its involvement in AD pathogenesis remains incompletely understood, particularly its effects on neuroinflammation and pyroptosis-related pathways, necessitating further exploration.

JC124

JC124 is a novel small-molecule compound discovered by Marchetti et al., which serves as an intermediate in the synthesis of GLB. This compound selectively inhibits NLRP3 formation and pro-caspase-1 activation, consequently reducing IL-1β production (Marchetti et al. 2015). In a rat model of traumatic brain injury, treatment with JC124 during the acute phase post-injury significantly suppresses injury-induced NLRP3 activation, mitigates neuronal damage, attenuates cerebral inflammatory cell activation, and inhibits the expression of proinflammatory cytokines (Kuwar et al. 2019). For TgCRND8 mice that have clearly shown AD pathological phenomena, JC124 suppresses NLRP3 inflammasome assembly and activation, downregulates Aβ1-42 expression and amyloid deposition, and also effectively inhibits microglia activation and exert neuroprotective effects (Yin et al. 2018). Research on AD prevention demonstrates that administering JC124 to APP/PS1 mice prior to AD pathology onset inhibits NLRP3, improves cognitive performance, reduces cerebral amyloid deposition, and alleviates cellular inflammatory responses (Kuwar et al. 2021). These findings highlight JC124’s therapeutic potential in AD prevention and treatment through modulation of the NLRP3-pyroptosis pathway, underscoring the need for further in-depth exploration.

MCC950

MCC950 (CRID3) is a small-molecule compound initially identified as a cytokine release inhibitor, which suppresses IL-1β maturation and secretion (Perregaux et al. 2001). Further research shows that MCC950 specifically inhibits ASC oligomerization induced by NLRP3, thereby inhibiting NLRP3 activation and IL-1β secretion (Coll et al. 2015). MCC950 is currently utilized in therapeutic strategies for multiple inflammation-related disorders, including AD (Zeng et al. 2021; Bakhshi and Shamsi 2022). In AD mouse models, MCC950 intervenes in the NLRP3/caspase-1/GSDMD pathway, effectively enhancing spatial memory and reducing amyloid deposits in the mouse brain (Li et al. 2020a). MCC950 blocks NLRP3 activation and IL-1β secretion in microglia, reduces CNS immune activity, enhances microglial clearance of Aβ, and prevents excessive tau phosphorylation in neurons (Li et al. 2023a; Dempsey et al. 2017; Lučiūnaitė et al. 2020). In neonatal rats, MCC950 mitigates ketamine-induced cognitive and behavioral deficits by suppressing the NLRP3/caspase-1 signaling pathway (Zhang et al. 2021). Additionally, MCC950 selectively prevents synaptic dysfunction in a mouse amyloidosis model by targeting NLRP3 inhibition (Qi et al. 2018). These findings collectively suggest that MCC950 holds significant potential in the treatment of AD, although its safety profile and neuroprotective effects require further validation through clinical trials.

OLT1177

The β-sulfonyl nitrile compound OLT1177 specifically targets NLRP3, potently blocking its ATPase activity, thereby blocking the activation of the classical NLRP3 pathway (Marchetti et al. 2018a). OLT1177 is highly specific to NLRP3 and has been applied in the treatment of various diseases, such as cardiovascular diseases and arthritis (Toldo et al. 2019; Marchetti et al. 2018b). Studies in AD mouse models demonstrate that oral administration of OLT1177 significantly reduces microglial activation, inhibits cortical amyloid deposition, and ameliorates cognitive dysfunction. Additionally, it inhibits the inflammatory response triggered by LPS in microglial (Lonnemann et al. 2020). In the microglial of aged rats, OLT1177 suppresses NLRP3 expression and reduces intracellular levels of IL-1β and CD68 (Anton et al. 2024). Currently, a phase 2 clinical trial for OLT1177 in treating gout is actively underway (Klück et al. 2020), and its safety has been demonstrated in phase 1 trials for cardiovascular disease patients (Wohlford et al. 2020). Although research on OLT1177’s role in AD is still limited, its therapeutic potential is noteworthy, warranting further exploration for future clinical applications.

Therapeutic Strategies Targeting Caspase-1

VX-765

VX-765 exhibits high bioavailability, strong blood–brain barrier permeability, and non-toxicity. The oral VX-765 drug for treating epilepsy has entered phase 2 clinical trials (Bialer et al. 2013). In the research on AD, VX-765 has been observed to reverse spatial and episodic memory deficits in J20 mouse models in a dose-dependent manner. Moreover, VX-765 effectively prevents Aβ deposition and reverses neuroinflammatory responses (Flores et al. 2018). In early therapeutic interventions for AD, VX-765 delays the onset of spatial and episodic memory deficits in J20 mouse models during the pre-symptomatic stage. However, while VX-765 mitigates neuroinflammation, it does not significantly affect Aβ levels (Flores et al. 2020). Furthermore, VX-765 alleviates cognitive impairment and tau pathology in mice induced by ketamine, sevoflurane, or propofol by inhibiting the NLRP3/caspase-1 pathway (Zhang et al. 2021; Tian et al. 2021; Zhang et al. 2024b). Focal cortical infarction can lead to Aβ accumulation in the ipsilateral thalamus and further cause secondary damage and inflammatory responses. VX-765 intervention significantly inhibits pyroptosis in the ipsilateral thalamus, reduces proinflammatory cytokines expression, decreases Aβ deposition, and improves post-cerebral infarction cognitive dysfunction (Liang et al. 2025). These results all reveal the important role of VX-765 in modulating pyroptosis and combating AD pathology. Nevertheless, controversies persist regarding its effects on amyloid deposition and neuroinflammation. Flores et al. noted that while caspase-1 inhibition improves spatial and episodic memory deficits in AD mice, it does not significantly ameliorate amyloid deposition or inflammation levels (Flores et al. 2022a). Based on current evidence, VX-765 may alleviate cognitive impairment and AD pathology by inhibiting pyroptosis. Moreover, as a relatively safe drug, VX-765 may have potential application value in the prevention and treatment of AD.

Therapeutic Strategies Targeting GSDMD

Sulfonamide Drugs

Mafenide (MAF), a sulfonamide antibiotic, exhibits broad-spectrum efficacy against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacterial strains (Fernández et al. 1992). In microglia undergoing LPS-induced pyroptosis, MAF blocks GSDMD cleavage by directly targeting the GSDMD-asp275 site, lowers p30-GSDMD levels, and decreases proinflammatory cytokine release. MAF also reduces proinflammatory cytokine levels in the cerebrospinal fluid and peripheral blood of APP/PS1 mice and inhibits microglial activation (Han et al. 2020c). MAF derivatives Sulfa-4 and Sulfa-22 exhibit superior efficacy compared to MAF, significantly inhibiting p30-GSDMD production, NLRP3 and caspase-1 expression, and reducing microglial activation and proinflammatory cytokines expression (Han et al. 2021). Although research on MAF in neurodegenerative diseases is limited, its potential therapeutic value in AD treatment cannot be overlooked, warranting further investigation.

microRNA-22

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are endogenous non-coding single-stranded RNA molecules approximately 18–25 nucleotides in length, which participate in diverse biological processes through the regulation of gene expression. MiRNAs directly target specific genes to modulate molecular expression. Han et al. demonstrated that AD patients show decreased peripheral blood miRNA-22 expression compared to healthy controls, and proinflammatory cytokines expression are negatively correlated with miRNA-22. Subsequent research demonstrated that miRNA-22 modulates neuroglial pyroptosis by directly suppressing GSDMD expression, which reduces proinflammatory cytokine secretion and alleviates cognitive deficits in AD murine models (Han et al. 2020a). Exosomes containing miRNA-22 (Exo-miRNA-22) secreted by adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells (ADMSC) were shown to effectively suppress GSDMD and p30-GSDMD expression, reduce NLRP3/caspase-1/GSDMD pathway components, and attenuate microglial pyroptosis along with cognitive and memory deficits in AD mouse models (Zhai et al. 2021). The targeted treatment of miRNA is closely related to neuroprotection and anti-neuroinflammation, and the discovery of miRNA-22 offers a novel potential approach for AD treatment, deserving further in-depth research.

Translational Relevance of Targeting Pyroptosis in Alzheimer’s Disease

Research on the mechanisms of pyroptosis has revealed its central role in AD. The activation and interaction of Aβ and tau pathology with pyroptosis pathways provide novel insights for AD treatment, making the identification of pyroptosis-targeted strategies and their clinical translation critically important. Small-molecule inhibitors, owing to their ease of administration, low production costs, and high optimization potential, have become a core focus in drug development. NLRP3 inhibitors such as MCC950 have demonstrated therapeutic efficacy in various preclinical models, including atherosclerosis (Zeng et al. 2021), diabetes (Yin et al. 2018), steatohepatitis (Mridha et al. 2017), and AD (Dempsey et al. 2017). Although MCC950 effectively inhibits the NLRP3-pyroptosis pathway, its Phase II clinical trial for rheumatoid arthritis was suspended due to hepatotoxicity (Mangan et al. 2018). OLT1177, currently in clinical trials for gout and cardiovascular diseases, exhibits significant potential in suppressing pyroptosis and alleviating AD pathology. Its specific inhibition of NLRP3 reduces off-target risks, enabling progression to preclinical studies. GLB, used in type 2 diabetes, targets the NLRP3 inflammasome in vitro to improve AD pathology (Malik et al. 2023), but its clinical translation remains challenging due to high-dose requirements in vivo and unclear mechanisms. Additionally, Telmisartan, an FDA-approved anti-hypertensive drug, mitigates AD neuroinflammation by inhibiting the microglial PPARγ/NLRP3 pathway (Fu et al. 2023), but its clinical value still needs to be further studied.

The oral drug VX-765, in Phase II trials for epilepsy (Bialer et al. 2013), shows neuroprotective effects in AD animal models by blocking caspase-1-mediated pyroptosis pathway. However, symptom recurrence upon withdrawal necessitates long-term administration, and its hepatotoxicity complicates clinical application (MacKenzie et al. 2010). While miRNA therapies have not yet entered AD clinical trials, intranasal delivery of miR-146a agomir rescues pathological and cognitive deficits in AD mouse models, providing a novel translational avenue. Despite the clear preclinical efficacy of pyroptosis-targeting compounds, their clinical translation faces challenges such as sustained efficacy, safety validation, and patient stratification (Mai et al. 2019). Future efforts require integrating precision medicine strategies and multidisciplinary collaboration to advance these therapies for AD treatment, offering new interventions for neurodegenerative diseases.

Discussion and Conclusion

This review systematically elaborates on the mechanisms of pyroptosis in the pathogenesis of AD and targeted therapeutic strategies against pyroptosis. It highlights the clinical translational value of molecular agents in AD treatment, offering novel therapeutic targets and pathology-modifying strategies for AD therapy. During the pathological process of AD, the persistent activation of neuroinflammation is closely related to pyroptosis, and the abnormal aggregation of Aβ and tau can directly trigger the pyroptosis signaling pathway by activating inflammasomes (such as NLRP3), forming a vicious cycle of “inflammation-neurodegeneration.” By inhibiting pyroptosis and the subsequent inflammatory responses, it is expected to prevent and alleviate the pathological phenomena related to AD. In the pathological progression of AD, multiple pyroptosis pathways may be concurrently activated. A systematic investigation and synthesis of the mechanisms and effects of pyroptosis pathways in AD could help elucidate the complex impacts of their crosstalk, thereby highlighting the critical need for this comprehensive review.

During the drug development process, some researchers focused on targeting downstream proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β of pyroptosis (Dubois et al. 2011; Kitazawa et al. 2011; Batista et al. 2021; Klein et al. 2020; Ridker et al. 2017). With the progressive elucidation of pyroptotic mechanisms, therapeutic approaches suppressing cytokine production at the source through upstream pathway modulation demonstrate improved therapeutic precision. However, interventions targeting the NLRP3/caspase-1/GSDMD axis may still incur off-target effects, highlighting the need for advanced molecular engineering to optimize pyroptosis inhibitor specificity. Notably, studies on targeting non-classical pyroptosis pathway are still in its infancy. Mohamed found that Palonosetron/methyllycaconitine inhibits the progression of sporadic AD by downregulating ASC expression and suppressing the activation of caspase-11 and caspase-1 (Mohamed et al. 2021). However, in Han’s study, Aβ1-42 induces upregulation of p30-GSDMD and caspase-1 levels in mouse neurons, but exhibits no significant effect on caspase-11 expression (Han et al. 2020b). These controversies underscore the necessity for parallel in-depth investigations into non-classical pyroptosis pathways to identify novel therapeutic targets. In addition, pyroptosis may have cross-regulation with the pathological mechanism of AD, which suggests the feasibility of combination therapies. For instance, synergistic strategies combining pyroptosis inhibitors with anti-Aβ biologics like lecanemab warrant exploration for enhanced therapeutic efficacy (Vitek et al. 2023; van Dyck et al. 2023). In summary, pyroptosis not only acts as a core driver of AD pathogenesis but also offers a novel perspective for moving beyond traditional “symptom control” approaches toward achieving “pathological modification.” Targeting pyroptosis as an emerging therapeutic strategy holds promise for unraveling the mysteries of AD pathogenesis and delivering more effective treatments for patients.

Author Contribution

Only T wrote and reviewed this manuscript.

Funding

There is no funding.

Data Availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

The manuscript does not contain clinical studies or patient data.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Aglietti RA, Estevez A, Gupta A, Ramirez MG, Liu PS, Kayagaki N, Ciferri C, Dixit VM, Dueber EC (2016) GsdmD p30 elicited by caspase-11 during pyroptosis forms pores in membranes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 113(28):7858–7863. 10.1073/pnas.1607769113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson FL, Biggs KE, Rankin BE, Havrda MC (2023) NLRP3 inflammasome in neurodegenerative disease. Translat Res J Lab Clin Med 252:21–33. 10.1016/j.trsl.2022.08.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anton PE, Nagpal P, Moreno J, Burchill MA, Chatterjee A, Busquet N, Mesches M, Kovacs EJ, McCullough RL (2024) NF-κB/NLRP3 Translational inhibition by nanoligomer therapy mitigates ethanol and advanced age-related neuroinflammation. bioRxiv : the preprint server for biology. 10.1101/2024.02.26.582114

- Bai Y, Liu D, Zhang H, Wang Y, Wang D, Cai H, Wen H, Yuan G, An H, Wang Y, Shi T, Wang Z (2021) N-salicyloyl tryptamine derivatives as potential therapeutic agents for Alzheimer’s disease with neuroprotective effects. Bioorg Chem 115:105255. 10.1016/j.bioorg.2021.105255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakhshi S, Shamsi S (2022) MCC950 in the treatment of NLRP3-mediated inflammatory diseases: latest evidence and therapeutic outcomes. Int Immunopharmacol 106:108595. 10.1016/j.intimp.2022.108595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baraka A, ElGhotny S (2010) Study of the effect of inhibiting galanin in Alzheimer’s disease induced in rats. Eur J Pharmacol 641(2–3):123–127. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2010.05.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batista AF, Rody T, Forny-Germano L, Cerdeiro S, Bellio M, Ferreira ST, Munoz DP, De Felice FG (2021) Interleukin-1β mediates alterations in mitochondrial fusion/fission proteins and memory impairment induced by amyloid-β oligomers. J Neuroinflammation 18(1):54. 10.1186/s12974-021-02099-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Better MA (2023) Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement 19(4):1598–1695. 10.1002/alz.13016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bialer M, Johannessen SI, Levy RH, Perucca E, Tomson T, White HS (2013) Progress report on new antiepileptic drugs: a summary of the eleventh eilat conference (EILAT XI). Epilepsy Res 103(1):2–30. 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2012.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blum-Degen D, Müller T, Kuhn W, Gerlach M, Przuntek H, Riederer P (1995) Interleukin-1 beta and interleukin-6 are elevated in the cerebrospinal fluid of Alzheimer’s and de novo Parkinson’s disease patients. Neurosci Lett 202(1–2):17–20. 10.1016/0304-3940(95)12192-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boise LH, Collins CM (2001) Salmonella-induced cell death: apoptosis, necrosis or programmed cell death? Trends Microbiol 9(2):64–67. 10.1016/s0966-842x(00)01937-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai Y, Chai Y, Fu Y, Wang Y, Zhang Y, Zhang X, Zhu L, Miao M, Yan T (2021) Salidroside ameliorates Alzheimer’s disease by targeting NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated pyroptosis. Front Aging Neurosci 13:809433. 10.3389/fnagi.2021.809433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai L, Fan Q, Pang R, Chen C, Zhang Y, Xie H, Huang J, Wang Y, Li P, Huang D, Jin X, Zhou Y, Li Y (2025) Microglia programmed cell death in neurodegenerative diseases and CNS injury. Apoptosis: an Int J Program Cell Death 30(1–2):446–465. 10.1007/s10495-024-02041-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JM, Jiang GX, Li QW, Zhou ZM, Cheng Q (2014) Increased serum levels of interleukin-18, -23 and -17 in Chinese patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 38(5–6):321–329. 10.1159/000360606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, He WT, Hu L, Li J, Fang Y, Wang X, Xu X, Wang Z, Huang K, Han J (2016) Pyroptosis is driven by non-selective gasdermin-D pore and its morphology is different from MLKL channel-mediated necroptosis. Cell Res 26(9):1007–1020. 10.1038/cr.2016.100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng L, Zhang W (2021) DJ-1 affects oxidative stress and pyroptosis in hippocampal neurons of Alzheimer’s disease mouse model by regulating the Nrf2 pathway. Exp Ther Med 21(6):557. 10.3892/etm.2021.9989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coll RC, Robertson AA, Chae JJ, Higgins SC, Muñoz-Planillo R, Inserra MC, Vetter I, Dungan LS, Monks BG, Stutz A, Croker DE, Butler MS, Haneklaus M, Sutton CE, Núñez G, Latz E, Kastner DL, Mills KH, Masters SL, Schroder K, Cooper MA, O’Neill LA (2015) A small-molecule inhibitor of the NLRP3 inflammasome for the treatment of inflammatory diseases. Nat Med 21(3):248–255. 10.1038/nm.3806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cookson BT, Brennan MA (2001) Pro-inflammatory programmed cell death. Trends Microbiol 9(3):113–114. 10.1016/s0966-842x(00)01936-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Amelio M, Cavallucci V, Middei S, Marchetti C, Pacioni S, Ferri A, Diamantini A, De Zio D, Carrara P, Battistini L, Moreno S, Bacci A, Ammassari-Teule M, Marie H, Cecconi F (2011) Caspase-3 triggers early synaptic dysfunction in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Neurosci 14(1):69–76. 10.1038/nn.2709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dadkhah M, Sharifi M (2025) The NLRP3 inflammasome: mechanisms of activation, regulation, and role in diseases. Int Rev Immunol 44(2):98–111. 10.1080/08830185.2024.2415688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Luigi A, Fragiacomo C, Lucca U, Quadri P, Tettamanti M, Grazia De Simoni M (2001) Inflammatory markers in Alzheimer’s disease and multi-infarct dementia. Mech Ageing Dev 122(16):1985–1995. 10.1016/s0047-6374(01)00313-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Rivero Vaccari JP, Dietrich WD, Keane RW (2014) Activation and regulation of cellular inflammasomes: gaps in our knowledge for central nervous system injury. J Cereb Blood Flow Metabol: off J Int Soc Cereb Blood Flow Metab 34(3):369–375. 10.1038/jcbfm.2013.227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dempsey C, Rubio Araiz A, Bryson KJ, Finucane O, Larkin C, Mills EL, Robertson AAB, Cooper MA, O’Neill LAJ, Lynch MA (2017) Inhibiting the NLRP3 inflammasome with MCC950 promotes non-phlogistic clearance of amyloid-β and cognitive function in APP/PS1 mice. Brain Behav Immun 61:306–316. 10.1016/j.bbi.2016.12.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubois EA, Rissmann R, Cohen AF (2011) Rilonacept and canakinumab. Br J Clin Pharmacol 71(5):639–641. 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2011.03958.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esmaeili MH, Bahari B, Salari AA (2018) ATP-sensitive potassium-channel inhibitor glibenclamide attenuates HPA axis hyperactivity, depression- and anxiety-related symptoms in a rat model of Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Res Bull 137:265–276. 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2018.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang Y, Tian S, Pan Y, Li W, Wang Q, Tang Y, Yu T, Wu X, Shi Y, Ma P, Shu Y (2020) Pyroptosis: a new frontier in cancer. Biomed Pharmacother 121:109595. 10.1016/j.biopha.2019.109595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández JC, Gamboa P, Jáuregui I, González G, Antépara I (1992) Concomitant sensitization to enoxolone and mafenide in a topical medicament. Contact Dermatitis 27(4):262. 10.1111/j.1600-0536.1992.tb03263.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores J, Noël A, Foveau B, Lynham J, Lecrux C, LeBlanc AC (2018) Caspase-1 inhibition alleviates cognitive impairment and neuropathology in an Alzheimer’s disease mouse model. Nat Commun 9(1):3916. 10.1038/s41467-018-06449-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores J, Noël A, Foveau B, Beauchet O, LeBlanc AC (2020) Pre-symptomatic caspase-1 inhibitor delays cognitive decline in a mouse model of Alzheimer disease and aging. Nat Commun 11(1):4571. 10.1038/s41467-020-18405-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores J, Fillion ML, LeBlanc AC (2022a) Caspase-1 inhibition improves cognition without significantly altering amyloid and inflammation in aged Alzheimer disease mice. Cell Death Dis 13(10):864. 10.1038/s41419-022-05290-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores J, Noël A, Fillion ML, LeBlanc AC (2022b) Therapeutic potential of Nlrp1 inflammasome, Caspase-1, or Caspase-6 against Alzheimer disease cognitive impairment. Cell Death Differ 29(3):657–669. 10.1038/s41418-021-00881-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman LC, Ting JP (2016) The pathogenic role of the inflammasome in neurodegenerative diseases. J Neurochem 136(Suppl 1):29–38. 10.1111/jnc.13217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friker LL, Scheiblich H, Hochheiser IV, Brinkschulte R, Riedel D, Latz E, Geyer M, Heneka MT (2020) β-Amyloid Clustering around ASC fibrils boosts its toxicity in microglia. Cell Rep 30(11):3743-3754.e3746. 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.02.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu XX, Wei B, Cao HM, Duan R, Deng Y, Lian HW, Zhang YD, Jiang T (2023) Telmisartan alleviates Alzheimer’s disease-related neuropathologies and cognitive impairments. J Alzheimer’s Dis: JAD 94(3):919–933. 10.3233/jad-230133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halle A, Hornung V, Petzold GC, Stewart CR, Monks BG, Reinheckel T, Fitzgerald KA, Latz E, Moore KJ, Golenbock DT (2008) The NALP3 inflammasome is involved in the innate immune response to amyloid-beta. Nat Immunol 9(8):857–865. 10.1038/ni.1636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han C, Guo L, Yang Y, Guan Q, Shen H, Sheng Y, Jiao Q (2020a) Mechanism of microRNA-22 in regulating neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Behavior 10(6):e01627. 10.1002/brb3.1627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han C, Yang Y, Guan Q, Zhang X, Shen H, Sheng Y, Wang J, Zhou X, Li W, Guo L, Jiao Q (2020b) New mechanism of nerve injury in Alzheimer’s disease: β-amyloid-induced neuronal pyroptosis. J Cell Mol Med 24(14):8078–8090. 10.1111/jcmm.15439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han C, Yang Y, Yu A, Guo L, Guan Q, Shen H, Jiao Q (2020c) Investigation on the mechanism of mafenide in inhibiting pyroptosis and the release of inflammatory factors. Eur J Pharmaceut Sci: off J Eur Feder Pharmaceut Sci 147:105303. 10.1016/j.ejps.2020.105303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han C, Hu Q, Yu A, Jiao Q, Yang Y (2021) Mafenide derivatives inhibit neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease by regulating pyroptosis. J Cell Mol Med 25(22):10534–10542. 10.1111/jcmm.16984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han YH, Liu XD, Jin MH, Sun HN, Kwon T (2023) Role of NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated neuronal pyroptosis and neuroinflammation in neurodegenerative diseases. Inflammat Res: off J Eur Histam Res Soc 72(9):1839–1859. 10.1007/s00011-023-01790-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardin MD, Jacobs TF (2025) Glyburide. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing Copyright © 2025, StatPearls publishing LLC., Treasure Island (FL) ineligible companies. Disclosure: Tibb Jacobs declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies

- He H, Jiang H, Chen Y, Ye J, Wang A, Wang C, Liu Q, Liang G, Deng X, Jiang W, Zhou R (2018) Oridonin is a covalent NLRP3 inhibitor with strong anti-inflammasome activity. Nat Commun 9(1):2550. 10.1038/s41467-018-04947-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heneka MT, Kummer MP, Stutz A, Delekate A, Schwartz S, Vieira-Saecker A, Griep A, Axt D, Remus A, Tzeng TC, Gelpi E, Halle A, Korte M, Latz E, Golenbock DT (2013) NLRP3 is activated in Alzheimer’s disease and contributes to pathology in APP/PS1 mice. Nature 493(7434):674–678. 10.1038/nature11729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong W, Hu C, Wang C, Zhu B, Tian M, Qin H (2023) Effects of amyloid β (Aβ)42 and Gasdermin D on the progression of Alzheimer’s disease in vitro and in vivo through the regulation of astrocyte pyroptosis. Aging (Albany NY) 15(21):12209–12224. 10.18632/aging.205174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu JJ, Liu X, Xia S, Zhang Z, Zhang Y, Zhao J, Ruan J, Luo X, Lou X, Bai Y, Wang J, Hollingsworth LR, Magupalli VG, Zhao L, Luo HR, Kim J, Lieberman J, Wu H (2020) FDA-approved disulfiram inhibits pyroptosis by blocking gasdermin D pore formation. Nat Immunol 21(7):736–745. 10.1038/s41590-020-0669-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y, Li X, Luo G, Wang J, Li R, Zhou C, Wan T, Yang F (2022) Pyroptosis as a candidate therapeutic target for Alzheimer’s disease. Front Aging Neurosci 14:996646. 10.3389/fnagi.2022.996646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang YY, Gan YH, Yang L, Cheng W, Yu JT (2024) Depression in Alzheimer’s disease: epidemiology, mechanisms, and treatment. Biol Psychiat 95(11):992–1005. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2023.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imre G (2024) Pyroptosis in health and disease. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 326(3):C784-c794. 10.1152/ajpcell.00503.2023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ising C, Venegas C, Zhang S, Scheiblich H, Schmidt SV, Vieira-Saecker A, Schwartz S, Albasset S, McManus RM, Tejera D, Griep A, Santarelli F, Brosseron F, Opitz S, Stunden J, Merten M, Kayed R, Golenbock DT, Blum D, Latz E, Buée L, Heneka MT (2019) NLRP3 inflammasome activation drives tau pathology. Nature 575(7784):669–673. 10.1038/s41586-019-1769-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jha D, Bakker E, Kumar R (2024) Mechanistic and therapeutic role of NLRP3 inflammasome in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurochem 168(10):3574–3598. 10.1111/jnc.15788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia J, Liu H, Sun L, Xu Y, Zeng X (2024) Thioredoxin-1 protects neurons through inhibiting NLRP1-mediated neuronal pyroptosis in models of Alzheimer’s disease. Mol Neurobiol 61(11):9723–9734. 10.1007/s12035-024-04341-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin X, Liu MY, Zhang DF, Zhong X, Du K, Qian P, Yao WF, Gao H, Wei MJ (2019) Baicalin mitigates cognitive impairment and protects neurons from microglia-mediated neuroinflammation via suppressing NLRP3 inflammasomes and TLR4/NF-κB signaling pathway. CNS Neurosci Ther 25(5):575–590. 10.1111/cns.13086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ju YJ, Kim N, Gee MS, Jeon SH, Lee D, Do J, Ryu JS, Lee JK (2020) Glibenclamide modulates microglial function and attenuates Aβ deposition in 5XFAD mice. Eur J Pharmacol 884:173416. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2020.173416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitazawa M, Cheng D, Tsukamoto MR, Koike MA, Wes PD, Vasilevko V, Cribbs DH, LaFerla FM (2011) Blocking IL-1 signaling rescues cognition, attenuates tau pathology, and restores neuronal β-catenin pathway function in an Alzheimer’s disease model. J Immunol 187(12):6539–6549. 10.4049/jimmunol.1100620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein AL, Imazio M, Brucato A, Cremer P, LeWinter M, Abbate A, Lin D, Martini A, Beutler A, Chang S, Fang F, Gervais A, Perrin R, Paolini JF (2020) RHAPSODY: rationale for and design of a pivotal phase 3 trial to assess efficacy and safety of rilonacept, an interleukin-1α and interleukin-1β trap, in patients with recurrent pericarditis. Am Heart J 228:81–90. 10.1016/j.ahj.2020.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klück V, Jansen T, Janssen M, Comarniceanu A, Efdé M, Tengesdal IW, Schraa K, Cleophas MCP, Scribner CL, Skouras DB, Marchetti C, Dinarello CA, Joosten LAB (2020) Dapansutrile, an oral selective NLRP3 inflammasome inhibitor, for treatment of gout flares: an open-label, dose-adaptive, proof-of-concept, phase 2a trial. Lancet Rheumatol 2(5):e270–e280. 10.1016/s2665-9913(20)30065-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klyucherev TO, Olszewski P, Shalimova AA, Chubarev VN, Tarasov VV, Attwood MM, Syvänen S, Schiöth HB (2022) Advances in the development of new biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease. Translat Neurodegen 11(1):25. 10.1186/s40035-022-00296-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kodi T, Sankhe R, Gopinathan A, Nandakumar K, Kishore A (2024) New insights on NLRP3 inflammasome: mechanisms of activation, inhibition, and epigenetic regulation. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol: off J S NeuroImmune Pharmacol 19(1):7. 10.1007/s11481-024-10101-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komleva YK, Lopatina OL, Gorina IV, Shuvaev AN, Chernykh A, Potapenko IV, Salmina AB (2021) NLRP3 deficiency-induced hippocampal dysfunction and anxiety-like behavior in mice. Brain Res 1752:147220. 10.1016/j.brainres.2020.147220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs SB, Miao EA (2017) Gasdermins: effectors of pyroptosis. Trends Cell Biol 27(9):673–684. 10.1016/j.tcb.2017.05.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kummer JA, Broekhuizen R, Everett H, Agostini L, Kuijk L, Martinon F, van Bruggen R, Tschopp J (2007) Inflammasome components NALP 1 and 3 show distinct but separate expression profiles in human tissues suggesting a site-specific role in the inflammatory response. J Histochem Cytochem: off J Histochem Soc 55(5):443–452. 10.1369/jhc.6A7101.2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuwar R, Rolfe A, Di L, Xu H, He L, Jiang Y, Zhang S, Sun D (2019) A novel small molecular NLRP3 inflammasome inhibitor alleviates neuroinflammatory response following traumatic brain injury. J Neuroinflam 16(1):81. 10.1186/s12974-019-1471-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuwar R, Rolfe A, Di L, Blevins H, Xu Y, Sun X, Bloom GS, Zhang S, Sun D (2021) A novel inhibitor targeting NLRP3 inflammasome reduces neuropathology and improves cognitive function in Alzheimer’s disease transgenic mice. J Alzheimer’s Dis: JAD 82(4):1769–1783. 10.3233/jad-210400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamkanfi M, Mueller JL, Vitari AC, Misaghi S, Fedorova A, Deshayes K, Lee WP, Hoffman HM, Dixit VM (2009) Glyburide inhibits the Cryopyrin/Nalp3 inflammasome. J Cell Biol 187(1):61–70. 10.1083/jcb.200903124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Zhuang L, Luo X, Liang J, Sun E, He Y (2020a) Protection of MCC950 against Alzheimer’s disease via inhibiting neuronal pyroptosis in SAMP8 mice. Exp Brain Res 238(11):2603–2614. 10.1007/s00221-020-05916-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Xu P, Shan J, Sun W, Ji X, Chi T, Liu P, Zou L (2020b) Interaction between hyperphosphorylated tau and pyroptosis in forskolin and streptozotocin induced AD models. Biomed Pharmacother 121:109618. 10.1016/j.biopha.2019.109618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li JM, Hu T, Zhou XN, Zhang T, Guo JH, Wang MY, Wu YL, Su WJ, Jiang CL (2023a) The involvement of NLRP3 inflammasome in CUMS-induced AD-like pathological changes and related cognitive decline in mice. J Neuroinflam 20(1):112. 10.1186/s12974-023-02791-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Zhang H, Yang L, Dong X, Han Y, Su Y, Li W, Li W (2023b) Inhibition of NLRP1 inflammasome improves autophagy dysfunction and Aβ disposition in APP/PS1 mice. Behavioral Brain Funct: BBF 19(1):7. 10.1186/s12993-023-00209-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang YB, Luo RX, Lu Z, Mao Y, Song PP, Li QW, Peng ZQ, Zhang YS (2025) VX-765 attenuates secondary damage and β-amyloid accumulation in ipsilateral thalamus after experimental stroke in rats. Exp Neurol 385:115097. 10.1016/j.expneurol.2024.115097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Libeu CA, Descamps O, Zhang Q, John V, Bredesen DE (2012) Altering APP proteolysis: increasing sAPPalpha production by targeting dimerization of the APP ectodomain. PLoS ONE 7(6):e40027. 10.1371/journal.pone.0040027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Zhang Z, Ruan J, Pan Y, Magupalli VG, Wu H, Lieberman J (2016) Inflammasome-activated gasdermin D causes pyroptosis by forming membrane pores. Nature 535(7610):153–158. 10.1038/nature18629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Zhang X, Ding Y, Zhou W, Tao L, Lu P, Wang Y, Hu R (2017) Nuclear factor E2-related factor-2 negatively regulates NLRP3 inflammasome activity by inhibiting reactive oxygen species-induced NLRP3 priming. Antioxid Redox Signal 26(1):28–43. 10.1089/ars.2015.6615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Song W, Yu Y, Su J, Shi X, Yang X, Wang H, Liu P, Zou L (2022) Inhibition of NLRP1-dependent pyroptosis prevents glycogen synthase kinase-3β overactivation-induced hyperphosphorylated Tau in rats. Neurotox Res 40(5):1163–1173. 10.1007/s12640-022-00554-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lonnemann N, Hosseini S, Marchetti C, Skouras DB, Stefanoni D, D’Alessandro A, Dinarello CA, Korte M (2020) The NLRP3 inflammasome inhibitor OLT1177 rescues cognitive impairment in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 117(50):32145–32154. 10.1073/pnas.2009680117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu F, Lan Z, Xin Z, He C, Guo Z, Xia X, Hu T (2020) Emerging insights into molecular mechanisms underlying pyroptosis and functions of inflammasomes in diseases. J Cell Physiol 235(4):3207–3221. 10.1002/jcp.29268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lučiūnaitė A, McManus RM, Jankunec M, Rácz I, Dansokho C, Dalgėdienė I, Schwartz S, Brosseron F, Heneka MT (2020) Soluble Aβ oligomers and protofibrils induce NLRP3 inflammasome activation in microglia. J Neurochem 155(6):650–661. 10.1111/jnc.14945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKenzie SH, Schipper JL, Clark AC (2010) The potential for caspases in drug discovery. Curr Opin Drug Discov Devel 13(5):568–576 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mai H, Fan W, Wang Y, Cai Y, Li X, Chen F, Chen X, Yang J, Tang P, Chen H, Zou T, Hong T, Wan C, Zhao B, Cui L (2019) Intranasal administration of miR-146a agomir rescued the pathological process and cognitive impairment in an AD mouse model. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids 18:681–695. 10.1016/j.omtn.2019.10.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malik S, Siddiqi MK, Naseem N, Nabi F, Masroor A, Majid N, Hashmi A, Khan RH (2023) Biophysical insight into the anti-fibrillation potential of Glyburide for its possible implication in therapeutic intervention of amyloid associated diseases. Biochimie 211:110–121. 10.1016/j.biochi.2023.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Man SM, Karki R, Kanneganti TD (2017) Molecular mechanisms and functions of pyroptosis, inflammatory caspases and inflammasomes in infectious diseases. Immunol Rev 277(1):61–75. 10.1111/imr.12534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangan MSJ, Olhava EJ, Roush WR, Seidel HM, Glick GD, Latz E (2018) Targeting the NLRP3 inflammasome in inflammatory diseases. Nat Rev Drug Discovery 17(8):588–606. 10.1038/nrd.2018.97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchetti C, Toldo S, Chojnacki J, Mezzaroma E, Liu K, Salloum FN, Nordio A, Carbone S, Mauro AG, Das A, Zalavadia AA, Halquist MS, Federici M, Van Tassell BW, Zhang S, Abbate A (2015) Pharmacologic inhibition of the NLRP3 inflammasome preserves cardiac function after ischemic and nonischemic injury in the mouse. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 66(1):1–8. 10.1097/fjc.0000000000000247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchetti C, Swartzwelter B, Gamboni F, Neff CP, Richter K, Azam T, Carta S, Tengesdal I, Nemkov T, D’Alessandro A, Henry C, Jones GS, Goodrich SA, St Laurent JP, Jones TM, Scribner CL, Barrow RB, Altman RD, Skouras DB, Gattorno M, Grau V, Janciauskiene S, Rubartelli A, Joosten LAB, Dinarello CA (2018a) OLT1177, a β-sulfonyl nitrile compound, safe in humans, inhibits the NLRP3 inflammasome and reverses the metabolic cost of inflammation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 115(7):E1530-e1539. 10.1073/pnas.1716095115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchetti C, Swartzwelter B, Koenders MI, Azam T, Tengesdal IW, Powers N, de Graaf DM, Dinarello CA, Joosten LAB (2018b) NLRP3 inflammasome inhibitor OLT1177 suppresses joint inflammation in murine models of acute arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther 20(1):169. 10.1186/s13075-018-1664-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McManus RM (2022) The role of immunity in Alzheimer’s disease. Adv Biol 6(5):e2101166. 10.1002/adbi.202101166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meeuwsen S, Persoon-Deen C, Bsibsi M, Bajramovic JJ, Ravid R, De Bolle L, van Noort JM (2005) Modulation of the cytokine network in human adult astrocytes by human herpesvirus-6A. J Neuroimmunol 164(1–2):37–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed RA, Abdallah DM, El-Brairy AI, Ahmed KA, El-Abhar HS (2021) Palonosetron/Methyllycaconitine deactivate hippocampal microglia 1, inflammasome assembly and pyroptosis to enhance cognition in a novel model of neuroinflammation. Molecules 26(16):5068. 10.3390/molecules26165068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro AR, Barbosa DJ, Remião F, Silva R (2023) Alzheimer’s disease: insights and new prospects in disease pathophysiology, biomarkers and disease-modifying drugs. Biochem Pharmacol 211:115522. 10.1016/j.bcp.2023.115522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moonen S, Koper MJ, Van Schoor E, Schaeverbeke JM, Vandenberghe R, von Arnim CAF, Tousseyn T, De Strooper B, Thal DR (2023) Pyroptosis in Alzheimer’s disease: cell type-specific activation in microglia, astrocytes and neurons. Acta Neuropathol 145(2):175–195. 10.1007/s00401-022-02528-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moujalled D, Strasser A, Liddell JR (2021) Molecular mechanisms of cell death in neurological diseases. Cell Death Differ 28(7):2029–2044. 10.1038/s41418-021-00814-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mridha AR, Wree A, Robertson AAB, Yeh MM, Johnson CD, Van Rooyen DM, Haczeyni F, Teoh NC, Savard C, Ioannou GN, Masters SL, Schroder K, Cooper MA, Feldstein AE, Farrell GC (2017) NLRP3 inflammasome blockade reduces liver inflammation and fibrosis in experimental NASH in mice. J Hepatol 66(5):1037–1046. 10.1016/j.jhep.2017.01.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakanishi A, Kaneko N, Takeda H, Sawasaki T, Morikawa S, Zhou W, Kurata M, Yamamoto T, Akbar SMF, Zako T, Masumoto J (2018) Amyloid β directly interacts with NLRP3 to initiate inflammasome activation: identification of an intrinsic NLRP3 ligand in a cell-free system. Inflamm Regen 38:27. 10.1186/s41232-018-0085-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ossenkoppele R, van der Kant R, Hansson O (2022) Tau biomarkers in Alzheimer’s disease: towards implementation in clinical practice and trials. Lancet Neurol 21(8):726–734. 10.1016/s1474-4422(22)00168-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paesmans I, Van Kolen K, Vandermeeren M, Shih PY, Wuyts D, Boone F, Garcia Sanchez S, Grauwen K, Van Hauwermeiren F, Van Opdenbosch N, Lamkanfi M, van Loo G, Bottelbergs A (2024) NLRP3 inflammasome activation and pyroptosis are dispensable for tau pathology. Front Aging Neurosci 16:1459134. 10.3389/fnagi.2024.1459134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panda C, Voelz C, Habib P, Mevissen C, Pufe T, Beyer C, Gupta S, Slowik A (2021) Aggregated Tau-PHF6 (VQIVYK) potentiates NLRP3 inflammasome expression and autophagy in human microglial cells. Cells 10(7):1652. 10.3390/cells10071652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey A, Li Z, Gautam M, Ghosh A, Man SM (2025) Molecular mechanisms of emerging inflammasome complexes and their activation and signaling in inflammation and pyroptosis. Immunol Rev 329(1):e13406. 10.1111/imr.13406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paroni G, Bisceglia P, Seripa D (2019) Understanding the amyloid hypothesis in alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimer’s Dis: JAD 68(2):493–510. 10.3233/JAD-180802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perregaux DG, McNiff P, Laliberte R, Hawryluk N, Peurano H, Stam E, Eggler J, Griffiths R, Dombroski MA, Gabel CA (2001) Identification and characterization of a novel class of interleukin-1 post-translational processing inhibitors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 299(1):187–197 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi Y, Klyubin I, Cuello AC, Rowan MJ (2018) NLRP3-dependent synaptic plasticity deficit in an Alzheimer’s disease amyloidosis model in vivo. Neurobiol Dis 114:24–30. 10.1016/j.nbd.2018.02.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu Z, Zhang H, Xia M, Gu J, Guo K, Wang H, Miao C (2023) Programmed death of microglia in Alzheimer’s disease: autophagy, ferroptosis, and pyroptosis. J Prevent Alzheimer’s Dis 10(1):95–103. 10.14283/jpad.2023.3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quan W, Decker Y, Luo Q, Chemla A, Chang HF, Li D, Fassbender K, Liu Y (2024) Deficiency of NLRP3 protects cerebral pericytes and attenuates Alzheimer’s pathology in tau-transgenic mice. Front Cell Neurosci 18:1471005. 10.3389/fncel.2024.1471005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez MLG, Salvesen GS (2018) A primer on caspase mechanisms. Semin Cell Dev Biol 82:79–85. 10.1016/j.semcdb.2018.01.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao Z, Zhu Y, Yang P, Chen Z, Xia Y, Qiao C, Liu W, Deng H, Li J, Ning P, Wang Z (2022) Pyroptosis in inflammatory diseases and cancer. Theranostics 12(9):4310–4329. 10.7150/thno.71086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinhardt S, Stoye N, Luderer M, Kiefer F, Schmitt U, Lieb K, Endres K (2018) Identification of disulfiram as a secretase-modulating compound with beneficial effects on Alzheimer’s disease hallmarks. Sci Rep 8(1):1329. 10.1038/s41598-018-19577-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren QG, Gong WG, Zhou H, Shu H, Wang YJ, Zhang ZJ (2019) Spatial training ameliorates long-term Alzheimer’s disease-like pathological deficits by reducing NLRP3 inflammasomes in PR5 Mice. Neurotherapeut J Am Soc Experiment NeuroTherapeut 16(2):450–464. 10.1007/s13311-018-00698-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridker PM, Everett BM, Thuren T, MacFadyen JG, Chang WH, Ballantyne C, Fonseca F, Nicolau J, Koenig W, Anker SD, Kastelein JJP, Cornel JH, Pais P, Pella D, Genest J, Cifkova R, Lorenzatti A, Forster T, Kobalava Z, Vida-Simiti L, Flather M, Shimokawa H, Ogawa H, Dellborg M, Rossi PRF, Troquay RPT, Libby P, Glynn RJ (2017) Antiinflammatory therapy with canakinumab for atherosclerotic disease. N Engl J Med 377(12):1119–1131. 10.1056/NEJMoa1707914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rostagno AA (2022) Pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Mol Sci. 10.3390/ijms24010107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rühl S, Broz P (2015) Caspase-11 activates a canonical NLRP3 inflammasome by promoting K(+) efflux. Eur J Immunol 45(10):2927–2936. 10.1002/eji.201545772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saresella M, La Rosa F, Piancone F, Zoppis M, Marventano I, Calabrese E, Rainone V, Nemni R, Mancuso R, Clerici M (2016) The NLRP3 and NLRP1 inflammasomes are activated in Alzheimer’s disease. Mol Neurodegener 11:23. 10.1186/s13024-016-0088-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sborgi L, Rühl S, Mulvihill E, Pipercevic J, Heilig R, Stahlberg H, Farady CJ, Müller DJ, Broz P, Hiller S (2016) GSDMD membrane pore formation constitutes the mechanism of pyroptotic cell death. EMBO J 35(16):1766–1778. 10.15252/embj.201694696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen H, Han C, Yang Y, Guo L, Sheng Y, Wang J, Li W, Zhai L, Wang G, Guan Q (2021) Pyroptosis executive protein GSDMD as a biomarker for diagnosis and identification of Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Behavior 11(4):e02063. 10.1002/brb3.2063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi J, Zhao Y, Wang Y, Gao W, Ding J, Li P, Hu L, Shao F (2014) Inflammatory caspases are innate immune receptors for intracellular LPS. Nature 514(7521):187–192. 10.1038/nature13683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi J, Zhao Y, Wang K, Shi X, Wang Y, Huang H, Zhuang Y, Cai T, Wang F, Shao F (2015) Cleavage of GSDMD by inflammatory caspases determines pyroptotic cell death. Nature 526(7575):660–665. 10.1038/nature15514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh J, Habean ML, Panicker N (2023) Inflammasome assembly in neurodegenerative diseases. Trends Neurosci 46(10):814–831. 10.1016/j.tins.2023.07.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Španić E, Langer Horvat L, Ilić K, Hof PR, Šimić G (2022) NLRP1 inflammasome activation in the hippocampal formation in Alzheimer’s disease: correlation with neuropathological changes and unbiasedly estimated neuronal loss. Cells. 10.3390/cells11142223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stancu IC, Cremers N, Vanrusselt H, Couturier J, Vanoosthuyse A, Kessels S, Lodder C, Brône B, Huaux F, Octave JN, Terwel D, Dewachter I (2019) Aggregated Tau activates NLRP3-ASC inflammasome exacerbating exogenously seeded and non-exogenously seeded Tau pathology in vivo. Acta Neuropathol 137(4):599–617. 10.1007/s00401-018-01957-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun L, Wang H, Wang Z, He S, Chen S, Liao D, Wang L, Yan J, Liu W, Lei X, Wang X (2012) Mixed lineage kinase domain-like protein mediates necrosis signaling downstream of RIP3 kinase. Cell 148(1–2):213–227. 10.1016/j.cell.2011.11.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svandova E, Vesela B, Janeckova E, Chai Y, Matalova E (2024) Exploring caspase functions in mouse models. Apoptosis: an Int J Program Cell Death 29(7–8):938–966. 10.1007/s10495-024-01976-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan MS, Tan L, Jiang T, Zhu XC, Wang HF, Jia CD, Yu JT (2014) Amyloid-β induces NLRP1-dependent neuronal pyroptosis in models of Alzheimer’s disease. Cell Death Dis 5(8):e1382. 10.1038/cddis.2014.348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tejera D, Mercan D, Sanchez-Caro JM, Hanan M, Greenberg D, Soreq H, Latz E, Golenbock D, Heneka MT (2019) Systemic inflammation impairs microglial Aβ clearance through NLRP3 inflammasome. EMBO J 38(17):e101064. 10.15252/embj.2018101064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teramoto N, Zhu HL, Ito Y (2004) Blocking actions of glibenclamide on ATP-sensitive K+ channels in pig urethral myocytes. J Pharm Pharmacol 56(3):395–399. 10.1211/0022357022755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thévenod F, Chathadi KV, Jiang B, Hopfer U (1992) ATP-sensitive K+ conductance in pancreatic zymogen granules: block by glyburide and activation by diazoxide. J Membr Biol 129(3):253–266. 10.1007/bf00232907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian D, Xing Y, Gao W, Zhang H, Song Y, Tian Y, Dai Z (2021) Sevoflurane aggravates the progress of Alzheimer’s disease through NLRP3/Caspase-1/Gasdermin D pathway. Front Cell Development Biol 9:801422. 10.3389/fcell.2021.801422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toldo S, Mauro AG, Cutter Z, Van Tassell BW, Mezzaroma E, Del Buono MG, Prestamburgo A, Potere N, Abbate A (2019) The NLRP3 inflammasome inhibitor, OLT1177 (Dapansutrile), reduces infarct size and preserves contractile function after ischemia reperfusion injury in the mouse. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 73(4):215–222. 10.1097/fjc.0000000000000658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres KC, Lima GS, Fiamoncini CM, Rezende VB, Pereira PA, Bicalho MA, Moraes EN, Romano-Silva MA (2014) Increased frequency of cluster of differentiation 14 (CD14+) monocytes expressing interleukin 1 beta (IL-1β) in Alzheimer’s disease patients and intermediate levels in late-onset depression patients. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 29(2):137–143. 10.1002/gps.3973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Dyck CH, Swanson CJ, Aisen P, Bateman RJ, Chen C, Gee M, Kanekiyo M, Li D, Reyderman L, Cohen S, Froelich L, Katayama S, Sabbagh M, Vellas B, Watson D, Dhadda S, Irizarry M, Kramer LD, Iwatsubo T (2023) Lecanemab in early Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med 388(1):9–21. 10.1056/NEJMoa2212948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vande Walle L, Jiménez Fernández D, Demon D, Van Laethem N, Van Hauwermeiren F, Van Gorp H, Van Opdenbosch N, Kayagaki N, Lamkanfi M (2016) Does caspase-12 suppress inflammasome activation? Nature 534(7605):E1-4. 10.1038/nature17649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villarreal AE, O’Bryant SE, Edwards M, Grajales S, Britton GB (2016) Serum-based protein profiles of Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment in elderly Hispanics. Neurodegenerat Dis Manag 6(3):203–213. 10.2217/nmt-2015-0009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitek GE, Decourt B, Sabbagh MN (2023) Lecanemab (BAN2401): an anti-beta-amyloid monoclonal antibody for the treatment of Alzheimer disease. Expert Opin Investig Drugs 32(2):89–94. 10.1080/13543784.2023.2178414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vontell RT, de Rivero Vaccari JP, Sun X, Gultekin SH, Bramlett HM, Dietrich WD, Keane RW (2023) Identification of inflammasome signaling proteins in neurons and microglia in early and intermediate stages of Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Pathol 33(4):e13142. 10.1111/bpa.13142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Kanneganti TD (2021) From pyroptosis, apoptosis and necroptosis to PANoptosis: a mechanistic compendium of programmed cell death pathways. Comput Struct Biotechnol J 19:4641–4657. 10.1016/j.csbj.2021.07.038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Yu L, Yang H, Li C, Hui Z, Xu Y, Zhu X (2016) Oridonin attenuates synaptic loss and cognitive deficits in an Aβ1-42-induced mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. PLoS ONE 11(3):e0151397. 10.1371/journal.pone.0151397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]