Abstract

TRPML2 activity is critical for endolysosomal integrity and chemokine secretion, and can be modulated by various ligands. Interestingly, two ML-SI3 isomers regulate TRPML2 oppositely. The molecular mechanism underlying this unique isomeric preference as well as the TRPML2 agonistic mechanism remains unknown. Here, we present six cryo-EM structures of human TRPML2 in distinct states revealing that the π-bulge of the S6 undergoes a π-α transition upon agonist binding, highlighting the remarkable role of the π-bulge in ion channel regulation. Moreover, we identify that PI(3,5)P2 allosterically affects the pose of ML2-SA1, a TRPML2 specific activator, resulting in an open channel without the π-α transition. Functional and structural studies show that mutating the S5 of TRPML1 to that of TRPML2 enables the mutated TRPML1 to be activated by (+)ML-SI3 and ML2-SA1. Thus, our work elucidates the activation mechanism of TRPML channels and paves the way for the development of selective TRPML modulators.

Subject terms: Cryoelectron microscopy, Permeation and transport, Transient receptor potential channels

TRPML2, a lysosomal TRP channel, regulates endolysosomal integrity and chemokine secretion. This work reports the cryo-EM structures of TRPML2 in multiple states bound to modulators revealing its diverse regulatory mechanisms among ion channels.

Introduction

Transient receptor potential channels (TRP channels) play diverse and important roles in eukaryotic cells and can be regulated by numerous environmental cues, endogenous ligands and synthesized small molecules1–3. TRPML channels, comprising TRPML1, TRPML2, and TRPML3, are non-selective cation channels located in endolysosomal membranes. These channels, which share high sequence homology (Fig. S1a), facilitate the transport of sodium, calcium, and other cations across their respective membranes4. TRPML1, a ubiquitously expressed lysosomal channel, is involved in many endolysosomal-dependent cellular processes, such as cholesterol accumulation, lipid trafficking, and autophagy4–6. TRPML2 expression is particularly high in lymphocytes, activated macrophages, and other immune cells, suggesting a critical role in innate immunity7,8. TRPML channels can be regulated by various small-molecule synthetic compounds and lipids, including the activators MK6-839, ML-SA18, ML-SA510, ML1-SA111, ML2-SA18, ML3-SA112, rapamycin13, the endogenous lipid PI(3,5)P214, and the inhibitors ML-SI315, the endogenous lipids PI(4,5)P2 and sphingomyelins16 (Fig. S1b). Of these inhibitors, the isomeric forms of ML-SI3 — (1 R,2 R)-ML-SI3 (hereafter referred to as (-)ML-SI3) and (1S,2S)-ML-SI3 (hereafter referred to as (+)ML-SI3) — have been shown to have varying effects on the activity of different TRPML channels17. Further development of TRPML channel modulators may directly contribute to the treatment of TRPML channel-related disorders and other diseases18,19.

TRPML2 has been shown to be expressed in early/recycling endosomes8,20, late endosomal and lysosomal (LEL) compartments21. TRPML2 follows the Arf6 pathway, mediated by clathrin-independent endocytosis, cycling between the plasma membrane and recycling endosomes22. Many pathogens take advantage of the endocytic machinery to infect humans. Importantly, TRPML2 expression is interferon-inducible and can enhance the uptake of an array of viruses, including influenza A virus, Zika virus, and yellow fever virus, through increased trafficking of endocytosed virus particles, subsequently improving viral clearance in immune cells23. TRPML2 is also activated by hypotonicity, participating in fast vesicular recycling as well as cytokine and chemokine release of the immune response8,20. Moreover, the human TRPML2K370Q variant was shown to be a loss-of-function mutant with respect to viral enhancement23,24. Thus, a better understanding of the modulators of TRPML2 may aid the development of therapeutic approaches for infectious and immune diseases.

The existing structures of mammalian TRPML channels25–31 reveal that these proteins form a classic tetrameric channel: each subunit contains six transmembrane helices (S1-S6), two pore helices (PH1 and PH2), and an ~30kD luminal/extracellular domain. The cytosolic extensions of S1-S3 (labeled as IS1-IS3), which include several basic amino acids, form a unique feature called the Mucolipin Domain that binds to either PI(3,5)P2 or PI(4,5)P2, allosterically regulating the activity of TRPML131,32. Modulator-bound structures, including TRPML1 in complex with either ML-SA1, ML-SI3, or temsirolimus (a rapamycin analog) and TRPML3 in complex with ML-SA1 have revealed distinct binding modes compared with other TRP channels26,29,31,33. In TRPML1, ML-SA1 and ML-SI3 bind to a hydrophobic pocket that is created by the S5, S6, and PH1 of one subunit and the S6 of the neighboring subunit. To date, structural information of human TRPML2 remains limited. The only available structures are from the human TRPML2 luminal domain34 and mouse TRPML2 in nanodiscs, which was captured in an inactive state30.

Here, we report six human TRPML2 structures with different modulators and four TRPML1 structures in the presence of distinct agonists (Fig. S2). These structures along with our functional analysis of two TRPML channels reveal a unique activation mechanism of TRPML2 among ion channels.

Results

Overall structure of human TRPML2

We expressed full-length human TRPML2 with an N-terminal Flag-tag by baculovirus-mediated gene transduction of mammalian cells. We attempted to purify the protein in pH 5 conditions; however, the protein was not well behaved, leading to a much lower yield at acidic pHs. This is supported by a previous finding, which demonstrated that the luminal domain was more stable at higher pHs34. The protein exhibited reasonable behavior under 0.06% (w/v) digitonin at pH 7.5 during gel filtration (Fig. S1c) and was subjected to structural determination by cryo-EM. The apo TRPML2 and the (-)ML-SI3 bound TRPML2 maps refined to 3.0 Å and 2.6 Å, respectively, with both representing a closed state. The structures of (+)ML-SI3 bound TRPML2 were determined at 2.7 Å in a pre-open conformation and at 2.6 Å in an open conformation. The structure of ML2-SA1 bound TRPML2 was determined at 2.5 Å representing a pre-open conformation and the structure of ML2-SA1/PI(3,5)P2 bound TRPML2 was determined at 2.6-Å in an open state (Fig. 1a–f, Figs. S3–6 and Table S1).

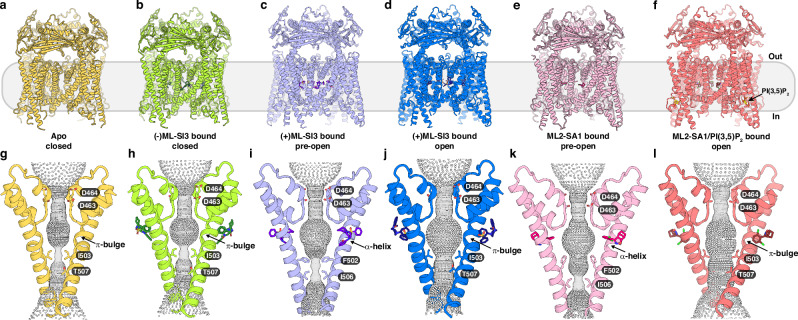

Fig. 1. Overview of TRPML2 structures bound to different compounds.

a–f Overall structures of human TRPML2 from the side of the membrane with respective substrates shown as sticks in darker respective colors: apo in yellow (a), (-)ML-SI3–bound in green with the molecule shown as sticks in dark green (b), (+)ML-SI3–bound in a pre-open state in light blue with molecule shown as sticks in purple (c), (+)ML-SI3–bound in an open state in blue with molecule shown as sticks in dark blue (d), ML2-SA1–bound in pink with molecule shown as sticks in dark pink (e), ML2-SA1/PI(3,5)P2–bound in salmon with ML2-SA1 shown as sticks in ruby (f). g–l Side view of the ion pore of each structure with the pore and the α-helix or π-bulge in S6 labeled. The lower gate residues and compounds are shown as sticks and colored as in (a–f). Gray balls indicate the path of the cation pore as calculated by HOLE.

Apo TRPML2 shares a similar topology with other TRPML channels, forming the characteristic homo-tetrameric structure with the ion channel situated at the center (Fig. 1a–f). Each subunit consists of six transmembrane helices (S1-S6), two pore helices (PH1 and PH2), and a luminal domain (Fig. S1a). Electron density maps show clear resolution for the overall structures, with the exception of a short linker in the luminal domain, and a linker between S2 and S3. The high local resolution of S4-S6 enables accurate modeling of the pore region side chains and all the ligands (Figs. S4–6). The overall structure of human apo TRPML2 is similar to that of mouse TRPML2 with an R.M.S.D. value of 1.1 Å, human TRPML1 in the apo state with an R.M.S.D. value of 1.4 Å and human TRPML3 in the apo state with an R.M.S.D. value of 1.3 Å (Fig. S7a–c). The overall architecture of human TRPML2 is also akin to that of PKD235 with an R.M.S.D. value of 8.5 Å (Fig. S7d).

Two main gates control ion selectivity and translocation through the transmembrane pore of TRPML2 (Fig. 1g–l). The first gate in the pore region is the selectivity filter, which consists of residues 461NGDD464 between PH1 and PH2. The carbonyls of residues N461 and G462 as well as the side chains of residues D463 and D464 face the pore axis. The second gate, also called the lower gate, is comprised of residues I503 and T507 that control the efflux of hydrated cations. The distance between diagonally opposed isoleucines in apo TRPML2 is 5.1 Å, which is consistent with the isoleucine distances in apo TRPML1 and TRPML3; in contrast, the diagonally opposed threonines are 7.6 Å away from each other (Fig. 1g and Fig. S3a). This distance is slightly larger than that in TRPML1 and TRPML3 (Fig. S7e). Additionally, the fact that 494DIYMI498 can form either a π-bulge or an α-helix demonstrates its crucial role in sensing the agonists of TRPML2 (Fig. 1g–l).

Structure of the (-)ML-SI3 bound TRPML2

Our previous study showed that ML-SI3 can block ML-SA1-mediated activation of TRPML1 without affecting PI(3,5)P2-mediated activation33. Interestingly, another study showed that there was a difference between the isomers of ML-SI317. It demonstrated that (-)ML-SI3 functions as an antagonist for all TRPML channels, while (+)ML-SI3 acts as an agonist for TRPML2 and TRPML3, but not for TRPML1. Structural comparison reveals that the overall structure of (-)ML-SI3 bound TRPML2 aligns well with the ML-SI3 bound TRPML1 with an R.M.S.D. value of 0.93 Å (Fig. 2a). The distances between diagonally opposed residues I503 and T507 in the lower gate are 5.8 Å and 8.3 Å, respectively (Fig. 1h and Fig. S3a, c), indicating the structure is in a closed state. Although the ML-SI3 used for the structural determination of ML-SI3-bound TRPML1 is a racemic mixture of (+)ML-SI3 and (-)ML-SI3, the binding poses of ML-SI3 in both structures are quite similar (Fig. 2b), indicating that the isomer bound to TRPML1 is the (-)ML-SI3 isomer. The residues F457 in PH1; L414, L418, C421, A424 and G425 in S5; F494 and F502 in S6; along with Y488, S492, Y496, and M497 in S6 of the neighboring subunit hydrophobically interact with (-)ML-SI3 while Y428 in S5 contacts (-)ML-SI3 via a π-π interaction (Fig. 2c).

Fig. 2. Binding and interaction details of (-)ML-SI3 and (+)ML-SI3.

a Structural comparison between ML-SI3–bound TRPML1 (7MGL) in gray and (-)ML-SI3–bound TRPML2 in green with the compounds shown in their respective colors. b Zoom-in comparison of molecule orientation between the two compounds in a, with the π-bulge indicated. c Interaction details of (-)ML-SI3–bound TRPML2 with important residues shown as sticks. Residues in gray denote a neighboring subunit. d Comparison of apo (yellow), and (+)ML-SI3–bound pre-open (light blue) TRPML2 with the α-helix indicated, and the movement of the S4-S5 linker denoted by a red arrow. e Interaction details of (+)ML-SI3–bound pre-open TRPML2 with residues shown as sticks and (+)ML-SI3 shown in purple. Residues in gray denote a neighboring subunit. f Comparison of apo (yellow), and (+)ML-SI3–bound open (blue) TRPML2 with the π-bulge indicated, and the movement of the S4-S5 linker denoted by a red arrow. g Interaction details of (+)ML-SI3–bound open TRPML2 with residues shown as sticks and (+)ML-SI3 shown in dark blue. Residues in gray denote a neighboring subunit. h Comparison of the poses of ML-SI3 in three structures and Y496 labeled as sticks.

Structures of (+)ML-SI3 bound TRPML2

Two structures of (+)ML-SI3-bound TRPML2 have been identified from one dataset (Fig. 1c, d and Fig. S5). Structural analysis shows that the lower gate of one structure is in a pre-open conformation, while the other one is in an open conformation (Fig. 1i, j and Fig. S3b, c). Compared to the structure of apo TRPML2, the S4-S5 linker in the pre-open TRPML2 shifts by 3 Å towards the cytosolic leaflet (Fig. 2d), although their S5 helices are well aligned. Notably, the π-bulge in S6 transitions to an α-helix upon interaction with (+)ML-SI3, initiating a 90° clockwise rotation of the cytosolic half of S6 starting at residue Y496, whose hydroxyl group interacts with the carbonyl group of the main chain of M410 in the S4-S5 linker (Fig. 2e). The hydrophobic contact between Y496 and L414 further stabilizes this state. Instead of residues I503 and T507, residues F502 and I506 form the lower gate, and the distances between diagonally opposed F502 and I506 in the lower gate are 6.1 Å and 5.3 Å, respectively, indicating the structure is in a pre-open state (Fig. 1i and Fig. S3a). Residues F457 and V460 in PH1; V417, C421, A424 and G425 in S5; I498 in S6; along with S492, I495 and Y496 in S6 of the neighboring subunit contribute to hydrophobically engage (+)ML-SI3 while Y428 in S5 contacts (+)ML-SI3 via a π-π interaction (Fig. 2e). The other state adopts an open conformation. The S4-S5 linker in the open TRPML2 shifts by 1.5 Å towards the cytosolic leaflet compared to that in the apo state (Fig. 2f). Residues V460 in PH1; V417, F420, C421, A424, G425, and Y428 in S5; F494, L499 and F502 in S6; along with Y488, S492 and Y496 in S6 of the neighboring subunit bind to (+)ML-SI3 and F457 in PH1 contacts (+)ML-SI3 via a π-π interaction (Fig. 2g).

The pose of (+)ML-SI3 in this state is completely different from the pre-open conformation and the π-bulge remains the same as that in the apo state (Fig. 2f). The 2-methoxyphenyl group of (+)ML-SI3 faces S6 of the neighboring subunit in the pre-open state, however, it rotates to face S5 and S6 in the open state (Fig. 2h). Compared to (-)ML-SI3, the specific conformation of (+)ML-SI3 allows it to have closer contacts with F420 in S5, L499 and F502 in S6 (Fig. 2g), leading to the opening of the lower gate with the distances between the diagonally opposed I503 and T507 in the lower gate being 8.7 Å and 9.6 Å, respectively (Fig. 1j and Fig. S3a). Such interactions were not detected in the (-)ML-SI3 bound state (Fig. 2c). Overall, TRPML2 can adopt two different conformations to engage (+)ML-SI3, either with or without the π-α transition of S6.

Structures of ML2-SA1 bound TRPML2

While many of the small molecules mentioned affect more than one TRPML channel, ML2-SA1 has been previously shown to be a TRPML2-selective agonist8. Our structural analysis shows that the ML2-SA1-bound TRPML2 is in a pre-open state (Fig. 1e, k and Fig. S3b). When ML2-SA1 binds to TRPML2, it induces a 4 Å shift of the S4-S5 linker toward the cytosolic leaflet (Fig. 3a). The π-bulge in S6 participates in the recruitment of the agonist, which subsequently transitions into an α-helix upon interaction (Fig. 3b). The norbornane ring of ML2-SA1 is positioned close to A424 in S5 while V460 in PH1 forms hydrophobic interactions with the 2,6-dichlorophenyl group. The residues C421, G425, and Y428 in S5; I498 in S6; along with I495 in the S6 of the neighboring subunit are involved in binding to ML2-SA1 (Fig. 3c). Like we observed in the (+)ML-SI3 bound TRPML2 pre-open state (Fig. 2e), M410 and L414 also interact with Y496 in the S6 of the neighboring subunit to stabilize this conformation (Fig. 3c). Interestingly, our cryo-EM map reveals two conformations of F502 in the lower gate (Fig. 3d and Fig. S6e). One conformation shows the side chain of F502 facing to the luminal leaflet, while the other conformation has F502 facing the cytosolic leaflet. This finding indicates the important role of F502 in regulating the lower gate in the presence of ML2-SA1.

Fig. 3. Interaction details of ML2-SA1 and allosteric effects of PI(3,5)P2.

a Structural comparison between apo TRPML2 (yellow) and ML2-SA1–bound TRPML2 (pink) with the molecule shown as sticks in dark pink, and the movement of the S4-S5 linker denoted by a red arrow. b Comparison of the same structures as shown in a rotated 90° with the movement of Y496 indicated by a red arrow. c Interaction details of ML2-SA1–bound TRPML2 with residues shown as sticks. d Pore distances through the ML2-SA1–bound TRPML2, with the different F502 orientations labeled (one in pink and one in sage). Right panel shows the same movement of F502 rotated 90°. e Comparison of ML-SA1/PI(3,5)P2–bound TRPML1 (7SQ9, light blue) with ML2-SA1/PI(3,5)P2–bound TRPML2 (salmon). f PI(3,5)P2 induces the conformational changes on the S4-S5 linker to prevent the rotation of S6. The salt bridges between residues and PI(3,5)P2 are indicated by dashed lines. g Interaction details of ML2-SA1/PI(3,5)P2–bound TRPML2 with residues shown as sticks. Residues in gray denote a neighboring subunit.

To further capture the active state of TRPML2, we added phosphatidylinositol 3,5-bisphosphate (PI(3,5)P2), an endogenous lipid that regulates endolysosomal operations and activates TRPML channels14, into the protein sample at a final concentration of 0.2 mM in the presence of ML2-SA1. The 2.6 Å structure reveals a completely open conformation of TRPML2 without the π-α transition of S6, which is akin to (+)ML-SI3-bound TRPML2 (Fig. 1j, l and Fig. S3a, b). Owing to the limited local resolution, only the polar head of PI(3,5)P2 can be defined in the map, with the pose of PI(3,5)P2 being similar to that in TRPML131 (Fig. 3e).

Interestingly, in the presence of PI(3,5)P2, the π-bulge in S6 does not change to an α-helix. Structural analysis indicates that the 3′ phosphate group of PI(3,5)P2 binds to Y347 in S3 and R395 in S4. These interactions allosterically trigger the conformational change of the S4-S5 linker, causing S413 to move towards S6 of the neighboring subunit to prevent its rotation (Fig. 3f). The resulting conformation reveals that ML2-SA1 binds in a different pose in the binding pocket to open the lower gate. The residues F457 and V460 in PH1; C421, A424, G425, and Y428 in S5; F494, I498, L499 and F502 in S6; along with Y496 in the S6 of the neighboring subunit are involved in the recruitment of ML2-SA1 (Fig. 3g). In this state, ML2-SA1 has much more extensive contacts with S6 than in the absence of PI(3,5)P2, and as a result, the lower gate is in a completely open state (Fig. 1l and Fig. S3b). It is most likely that the engagement of PI(3,5)P2 confines the conformation of S6 resulting in a different ML2-SA1 mediated activation mode. This finding is distinct from the previous discovery on TRPML1, where PI(3,5)P2 binding does not alter the pose of ML-SA1 in TRPML1 during activation31,32.

Electrophysiology Validation

To verify our findings, we generated two individual mutants on the agonist-binding sites: L414A in S5, F457A in PH1 and Y496A in S6. HEK293 cells were transiently transfected with the respective TRPML2 mutant constructs. Although TRPML2L414A and TRPML2F457A do not express in lysosomes, both variants express on the cell surface, similar to TRPML2WT (Fig. S8a, b). We performed patch clamp experiments in an inside-out configuration (Fig. 4a, b). Consistent with our structural findings, L414A and F457A reduced the channel activity in the presence of either (+)ML-SI3 or ML2-SA1 compared to wild-type (WT), while TRPML2L414A, but not TRPML2F457A, could be activated by PI(3,5)P2 (Fig. S8c). F457 contributes to hydrophobic contacts with Y488 and I491 in S6, so it is possible that the F457A mutation may abolish the dynamics of the TRPML2 pore, explaining the lack of PI(3,5)P2 activation.

Fig. 4. Electrophysiological characterization of TRPML2 mutants.

a Representative current density-voltage (I/Cm-V) relation of transiently expressed and localized in plasma membrane human TRPML2-eYFP variants, WT (left) or L414A mutant (right). b Representative current density-voltage (I/Cm-V) relation of transiently expressed and localized in plasma membrane human TRPML2-eYFP variants, WT (left) or F457A mutant (right). c Representative current density-voltage (I/Cm-V) relation of transiently expressed and endolysosomal localized human TRPML2-eYFP variants, WT (left) and Y496A mutant (right). For each panel (a–c), basal levels are shown in black. Channels were activated by application of (+)ML-SI3 (10 µM, blue, top) or ML2-SA1 (10 µM, pink, bottom). Statistical analysis of experiments is shown in bar graphs (far right), with each dot representing mean of biological replicate measurements withdrawn at −100 mV, with the exact n indicated above each bar, and the precise p value shown (mean ± SEM, one-way ANOVA, Tukey’s post hoc test using GraphPad Prism 10.2.3, ****p < 0.0001, **p < 0.01).

We also performed lysosomal patch-clamp electrophysiology experiments using endolysosomal vesicles isolated from cells expressing TRPML2Y496A (Fig. 4c and Fig. S8d). Our data showed that Y496A abolished the channel activity in the presence of either (+)ML-SI3 or ML2-SA1 compared to wild-type (WT) (Fig. 4c). The results of TRPML2L414A support the important role of L414 being in hydrophobic contact with Y496 in α-helical S6 to stabilize the active state upon the agonist binding. It is interesting that TRPML2Y496A retains some activity in the presence of (+)ML-SI3 (Fig. 4c). Our structures showed that Y496 is crucial for the π-to-α transition upon ML2-SA1 and (+)ML-SI3 binding. However, in the open states without a π-to-α transition, Y496 is 4.5-5 Å away from (+)ML-SI3, contributing less to the substrate interactions than in the ML2-SA1–bound state (3.5 Å between Y496 and ML2-SA1). As a result, TRPML2Y496A can still partially sense (+)ML-SI3 without the π-to-α transition.

Engineering TRPML1 for TRPML2-specific agonists

Superposition of agonist-bound TRPML1 and TRPML2 revealed two key residues in the S5 — V432/A433 in TRPML1 and A424/G425 in TRPML2 — that play crucial roles in agonist recognition, determining agonist selectivity (Figs. 2e, g, 3c, g). The ML-SI3 in TRPML1 adopts the same conformation as that of (-)ML-SI3 (Fig. 2b). In contrast, when we docked the (+)ML-SI3 into the TRPML1 structure, it seems that the piperazine ring of (+)ML-SI3 would clash with V432 and A433 of TRPML1 (Fig. 5a). Moreover, when we docked the ML2-SA1 into the TRPML1 structure, the norbornane ring of ML2-SA1 is positioned close to V432 which would potentially clash with ML2-SA1. Additionally, residue Y507 prevents the accommodation of the 2,6-dichlorophenyl group of ML2-SA1 (Fig. 5b). Compared to TRPML1, the binding pocket in TRPML2 is more spacious, allowing for better accommodation of the entire ML2-SA1 molecule.

Fig. 5. Docking and electrophysiological characterization of TRPML1VA/AG in the presence of (+)ML-SI3 and ML2-SA1.

a Docking of (+)ML-SI3 (dark blue) from the (+)ML-SI3 bound TRPML2 open conformation into ML-SI3 bound TRPML1 (PDB: 7MGL; gray). b Docking of ML2-SA1 (dark pink) from the ML2-SA1 bound TRPML2 pre-open conformation into ML-SI3 bound TRPML1 (PDB: 7MGL; gray). The TRPML1 residues of importance are labeled and represented as sticks. The red arrow indicates potential clashes between the compound and TRPML1. c Representative current density-voltage (I/Cm-V) relation of transiently expressed and endolysosomal localized human TRPML1-eYFP variants, WT (left) and V432A/A433G mutant (right). Basal levels are shown in black. Channels were activated by application of (+)ML-SI3 (10 µM, blue, top) or ML2-SA1 (10 µM, pink, bottom). Statistical analysis of experiments is shown in bar graphs (far right), with each dot representing mean of biological replicate measurements withdrawn at −100 mV, with the exact n indicated above each bar, and the precise p value shown (mean ± SEM, one-way ANOVA, Tukey’s post hoc test using GraphPad Prism 10.2.3, ****p < 0.0001).

To investigate this further, we generated a TRPML1 variant with V432A/A433G mutations (TRPML1VA/AG). The immunoblotting showed that the expression level of TRPML1WT and TRPML1VA/AG in HEK293 cells are similar (Fig. S8b). Compared to TRPML1WT, TRPML1VA/AG responded to ML2-SA1 stimulation, albeit the activation faded within 30 s (Fig. 5c and Fig. S8e). Additionally, we determined the structure of the TRPML1VA/AG variant in the presence of ML2-SA1 at a resolution of 2.4 Å (Fig. S9a–d and Table S2). Structural analysis revealed that the lower gate of TRPML1VA/AG is slightly open (Fig. 6a, b and Fig. S3a, d), which could explain the short activation by ML2-SA1 presumably owing to its relatively weak binding. ML2-SA1 was clearly defined in the cryo-EM map, adopting a pose different from either of its poses in TRPML2, but akin to that of ML-SA1 in TRPML1. Indeed, the pose of ML2-SA1 in the TRPML1VA/AG variant is much shallower than either of its poses in TRPML2, both of which are much deeper, regardless of the presence of PI(3,5)P2, (Fig. S9e–g). This deep binding in the pocket fosters greater contacts between the ligand and the protein causing ML2-SA1 to be highly selective for TRPML2.

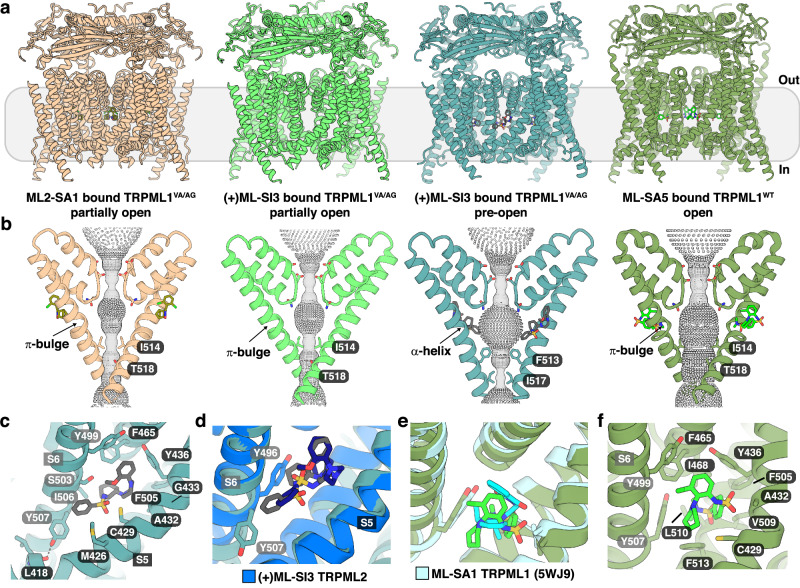

Fig. 6. Structures of ML2-SA1 and (+)ML-SI3–bound TRPML1VA/AG, and ML-SA5–bound TRPML1WT.

a Side view of TRPML1VA/AG and TRPML1WT bound to different ligands (from left to right): ML2-SA1–bound TRPML1VA/AG in tan with the substrate in olive; (+)ML-SI3–bound TRPML1VA/AG in a partially open state in green; (+)ML-SI3–bound TRPML1VA/AG in a pre-open state in teal with (+)ML-SI3 indicated in gray sticks; and ML-SA5–bound TRPML1WT in green with ML-SA5 shown in light green sticks. b Side view of the ion pore of each structure with the pore and the α-helix or π-bulge in S6 labeled. The lower gate residues and compounds are shown in sticks and colored as in (a). Gray balls indicate the path of the cation pore as calculated by HOLE. c Interaction details of (+)ML-SI3–bound TRPML1VA/AG pre-open state with residues shown as sticks. Residues in gray denote a neighboring subunit. d Comparison of the binding orientation of (+)ML-SI3–bound TRPML1VA/AG (teal/gray) with (+)ML-SI3–bound TRPML2 in an open state (blue/dark blue). e Comparison of the binding orientation of ML-SA5–bound TRPML1WT (green) with ML-SA1–bound TRPML1 (5WJ9, cyan). f Interaction details of ML-SA5–bound TRPML1WT with residues shown as sticks.

Our electrophysiological experiments showed that TRPML1VA/AG also responded to stimulation by (+)ML-SI3 (Fig. 5c). Therefore, we determined the structure of the (+)ML-SI3 bound TRPML1VA/AG. The final particles were classified into four classes. Two classes showed the open conformation and the other two revealed the closed conformation (Fig. 6a, b). The particle ratio of the open to closed states is 3:5. We selected one class from each state based on the quality of the maps and carried out further refinement. The two states were determined at 2.4 Å and 2.7 Å, respectively (Fig. 6a, Fig. S10a–g and Table S2). In one conformation, the density of (+)ML-SI3 is not well defined and the distance between the diagonally opposed I514 and T518 in the lower gate is 6.4 Å and 7.6 Å, indicating a partially open state (Fig. 6b and Fig. S3a, e). However, in the other map, a putative (+)ML-SI3 can be identified bound to TRPML1VA/AG, which triggers the π-to-α transition in S6 causing the distances between the diagonally opposed F513 and I517 in the lower gate being 7.7 Å and 5.0 Å, representing a pre-open state (Fig. 6b and Fig. S3a, e). Similar to our findings on TRPML2 (Figs. 2e and 3c), the hydroxyl group of Y507 forms a hydrogen bond with the carbonyl group of the main chain of L418 to stabilize the α-helix in S6. Residues F465 in PH1; M426, C429, A432, G433, and Y436 in S5, F505 in S6 along with Y499, S503, I506 and Y507 in S6 of the neighboring subunit bind to (+)ML-SI3 and Y436 in S5 contacts (+)ML-SI3 via a π-π interaction (Fig. 6c). While (+)ML-SI3 adopts a similar conformation to that in the open (+)ML-SI3 bound TRPML2, (+)ML-SI3 in the TRPML1VA/AG inserts more towards the pore center causing the π-to-α transition (Fig. 6d).

A previous study identified ML-SA5 as a more potent agonist of TRPML1 than ML-SA110,36. However, how ML-SA5 activates TRPML1WT remains unclear. Our structure of ML-SA5 bound TRPML1WT at 2.8 Å resolution presented in an open conformation (Fig. 6a, b, Fig. S10h–k and Table S2), and revealed that ML-SA5 binds to a similar site like ML-SA1 (Fig. 6e); nevertheless, the S6 still retains the π-bulge conformation. Residues F465 and I468 in PH1; C429, A432, and Y436 in S5, F505, V509, L510 and F513 in S6 along with Y499 and Y507 in S6 of the neighboring subunit bind to ML-SA5 (Fig. 6f). Since no agonist-bound TRPML1WT structure shows a π-to-α transition in S6 so far, it is tempting to speculate that the activation mechanism of TRPML1 may be different from TRPML2.

The transition of S6 during activation

Structural comparison reveals that unlike TRPML131 and TRPML326, the luminal domain of TRPML2 does not rotate during gating; however, the S6 presents notable changes in the distinct states. The π-bulge gating elements have been identified in the S6 of most TRP channels and classified into three groups37: (1) those with a π-bulge in S6 in both closed and open conformations (like TRPML129, TRPA138 and TRPV139) (Fig. S7f); (2) those with an α-helical S6 in the closed state that undergo an α-to-π transition upon activation (like TRPV240, TRPV341 and TRPC442) (Fig. S7g); and (3) those with a π-bulge turn in their S6 helices in the closed state that undergo a π-to-α transition upon binding their agonists43. To the best of our knowledge, the only observed case of a π-to-α transition in the same channel during activation was identified in a comparison between PKD2 and its variant PKD2F604P43 (Fig. S7h), but this transition was introduced by a F604P mutation in S5 to compensate for the loss of the S6 π-bulge rather than binding agonists. In addition to these groupings based on activation, the S6IV of some voltage-gated calcium channels and sodium channels can undergo an α-to-π transition upon the binding of pore blockers to close the pore44. Our results provide structural evidence to present how the π-bulge in TRPML2 is involved in agonist engagement, and how agonist binding mediates this π-to-α transition, highlighting and complementing the diverse role of the π-bulge in channel modulation.

There are two possible mechanisms for the opening of the lower gate: 1) the S6 helix rotates upon its transition from the apo to pre-open to open states; or 2) the lower gate can open when the S6 contains a π-bulge or after a π-to-α transition occurs. We performed molecular dynamic simulations using the transmembrane domain of the (+)ML-SI3 bound pre-open and open states individually. After 200 ns simulations, the results from the open state showed that when S6 contains a π-bulge, the lower gate remains stable with a symmetric central pore. In contrast, simulations from the pre-open state reveal that the π-to-α transition in S6 is retained during the 200 ns; the channel becomes more dynamic, and the central pore becomes asymmetrical, with an opening only in one direction (Fig. S11). Based on these results, we favor the second mechanism of opening the lower gate. Since we are currently not able to capture the open state after a π-to-α transition, it is likely that this state may need additional factors (e.g., lipid or other ligands) in the local environment to be stabilized in vitro.

Discussion

TRPML2 is essential for endolysosomal integrity as well as chemokine trafficking and secretion. Activation of TRPML2 promotes intracellular trafficking through recycling endosomes. Here, we report the structures of TRPML2 in multiple states bound to distinct modulators, revealing its diverse regulatory mechanisms among ion channels. Our findings show how ligand isomerism affects the regulation of TRPML2, how a π-bulge in S6 is involved in the recognition of TRPML2-specific agonists, and how a lipid allosteric modulator affects the agonist binding mode. Moreover, combined with our findings on TRPML2, our studies on the TRPML1VA/AG variant elucidate the agonistic mechanism of the TRPML family.

The o-dichlorobenzene ring of ML2-SA1 and the cyclohexane ring of (+)ML-SI3 insert more deeply into the center of TRPML2, interacting with residues in the π-bulge of the neighboring monomer to trigger the π-to-α transition of S6 (Figs. 2e and 3c). However, this insertion considerably reduces the contacts between the agonist and S6. (+)ML-SI3 just contacts I498 in S6 in the pre-open state (Fig. 2e), but interacts with F494, L499, and F502 in the open state (Fig. 2g). ML2-SA1 interacts with I498 in S6 in the pre-open state (Fig. 3c), but interacts with F494, I498, L499 and F502 in the open state (Fig. 3g). In PKD2, F604 in S5 has hydrophobic contact with F670 in S6 (Fig. S7h), F604P disrupts this interaction to offer S6 more flexibility during activation. In contrast, the lower gate of ML2-SA1 bound TRPML2 has extensive interactions with S5 in our structure. Nevertheless, it remains unclear how these agonists trigger the lower gate to completely open and additional structural or dynamics studies should be conducted.

Unlike TRPML1, TRPML2 exhibits distinct agonist binding modes for one ligand. Our findings provide the structural evidence that ligand isomerism may be a critical determinant of their biological functions and some ligands that have different isomers may be reviewed to test their individual effects on channel regulation. Our structures suggest that the smaller residues A424 and G425 in the S5 segment of TRPML2 reduce steric hindrance in the ligand-binding pocket. This structural feature allows diverse ligands to access the channel core to adopt multiple binding poses, thereby facilitating channel activation. Additionally, a previous study demonstrated that proline substitutions at similar positions in the S5 segment of TRPMLs, as well as in TRPV5 and TRPV6, lead to constitutive activation of TRP channels45. This finding underscores the critical role of the S5 segment in channel activation. It is likely that the S5 segment is crucial in recognizing diverse ligands, which either trigger the π-α transition in the S6 segment or directly push S6, leading to the opening of the lower gate. Contrary to previous knowledge about TRP channels, our results demonstrate that the conformation of the π-bulge in S6, observed in both TRPML1 variants and TRPML2, can be regulated by agonists during activation. Owing to the important roles of TRPML channels in lysosomal function and immune response, our work may aid the development of selective modulators of TRPML channels.

Methods

Protein expression and purification of human TRPML2

The complementary DNA (cDNA) encoding full length human wild-type TRPML2 (TRPML2WT, NCBI NP694991.2) with an N-terminal FLAG tag was cloned into the pEG BacMam vector46,47. The protein was expressed using baculovirus-mediated transduction of mammalian HEK-293S GnTI- cells (ATCC no. CRL-3022). Transfected cells were grown at 30 °C for 72 h post transduction. Cells were then harvested and disrupted by sonication in lysis buffer (20 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM PMSF, and 5 mg/mL leupeptin). Lysate was subjected to centrifugation for 10 min at 3220 x g, and the supernatant was incubated with 1% (w/v) Lauryl Maltose Neopentyl Glycol (LMNG, Anatrace) at 4 °C for 1 h. The lysate was clarified by a 30-minute centrifugation at 38,759 x g, and the resulting supernatant was loaded onto a Flag-M2 affinity column (Sigma-Aldrich). The resin was washed with 10 column volumes of wash buffer (20 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.01% LMNG, and 5 mM EGTA). The protein was then eluted with elution buffer (20 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.01% LMNG, and 2 mM EGTA, 100 mg/mL 3xFlag peptide). The eluate was then concentrated and purified by size exclusion chromatography (SEC) on a Superose 6 Increase column (Cytiva). The SEC buffer contained 20 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EGTA, and 0.06% (w/v) Digitonin (ACROS Organics). Peak fractions were collected and concentrated for grid preparation.

Protein expression and purification of human TRPML1 constructs

The complementary DNA (cDNA) encoding either full length human wild-type TRPML1 (TRPML1WT, NCBI NP065394.1), or full length human TRPML1 with the V432A/A433G mutations (TRPML1VA/AG), both with N-terminal FLAG tags, were separately cloned into the pEG BacMam vector46. The protein was expressed according to the previously published protocol29. Briefly, the proteins were expressed using baculovirus-mediated transduction of mammalian HEK-293S GnTI- cells. Transfected cells were grown at 37 °C for 48 h post transduction. Cells were then harvested and disrupted by sonication in lysis buffer (20 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM PMSF, and 5 mg/mL leupeptin). Lysate was subjected to centrifugation for 10 min at 3220 x g, and the supernatant was incubated with 1% (w/v) LMNG at 4 °C for 1 h. The lysate was clarified by a 30-minute centrifugation at 38,759 x g, and the resulting supernatant was loaded onto a Flag-M2 affinity column (Sigma-Aldrich). The resin was washed with 10 column volumes of wash buffer (20 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, and 0.01% LMNG). The protein was then eluted with elution buffer (20 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.01% LMNG, and 100 mg/mL 3xFlag peptide). The eluate was then concentrated and purified by size exclusion chromatography (SEC) on a Superose 6 Increase column. The SEC buffer contained 20 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, and 0.06% (w/v) Digitonin. Peak fractions were collected and concentrated for grid preparation.

Cryo-EM sample preparation and data acquisition

For the apo TRPML2 data collection, concentrated protein sample was applied directly to the grids. For all other structures, concentrated protein was incubated with the compound(s) of interest for 30 min to 1 h on ice prior to grid preparation. Small molecule compounds, (-)ML-SI3, (+)ML-SI3, ML2-SA1, and ML-SA5, were solubilized in DMSO to 50 mM and added to the protein to a final concentration of 1 mM. PI(3,5)P2 was solubilized in water at 10 mM and added to the protein to a final concentration of 0.2 mM. For grid preparation, 3 μl of each protein sample was applied to R1.2/1.3 400 mesh Au holey carbon grids (Quantifoil). After 3 s, the grids were blotted for 4-5 s and plunged into liquid ethane using a Vitrobot Mark IV (FEI) operated at 22 °C and 100% humidity. The grids were loaded onto a 300 kV Titan Krios transmission electron microscope for data collection, and data was collected using SerialEM version 3.7.10. All datasets were collected with a Falcon 4i camera with the exception of the ML2-SA1/PI(3,5)P2–bound TRPML2 dataset, which was collected with a Gatan K3 camera. Raw movie stacks for the Falcon 4i were collected at a physical pixel size of either 0.738 or 0.936 Å per pixel. The raw movie stacks from the K3 camera were collected at a physical pixel size of 0.826 Å per pixel. All datasets were collected with a nominal defocus range of −0.8 to −1.8 μm. Exposure time for the Falcon 4i datasets was 4 s, with about 1271 frames total in EER format, while the exposure time for the Gatan K3 dataset was 5 s, dose-fractionated into 50 frames with a dose rate of ~1.2-1.4 e–/pixel/s, and collected in CDS (correlated double sampling) mode. All micrographs had a total dose of ~60 electrons per Å2.

Cryo-EM image processing

For each dataset, the dark-subtracted images were first gain-normalized, corrected for beam-induced motion, and the contrast transfer function (CTF) was estimated using cryoSPARC v3.3.148. Auto picking was performed with crYOLO v1.9.6 using the general model49 with a particle threshold of 0.1. Subsequent 2D classification, multi-class ab-initio reconstruction, heterogeneous 3D refinement, and nonuniform refinements were performed in cryoSPARC. For certain datasets, further 3D classification, 3D refinement, and masked 3D classification without alignment were performed in RELION v3.1.350. Good classes from RELION were transferred to cryoSPARC where they were further refined using nonuniform refinements. The per-particle defocus was then refined using the local CTF refinement, followed by local refinements with soft masks covering TRPML1 or 2 to further improve the map quality. The final maps were sharpened to half the value of the default cryoSPARC sharpened maps, as this seemed to give the best side chain and main chain densities. The mask-corrected FSC curves were calculated in cryoSPARC, and reported resolutions are based on the 0.143 criterion. Local resolution estimations were performed in cryoSPARC.

Model building and refinement

A predicted model of TRPML2 was generated by AlphaFold51. This model was then docked into the density map using ChimeraX 1.852. The model was then refined iteratively using Coot 0.9.853 and Phenix 1.2154. After the apo TRPML2 model was built, it was used as the base model to build the other conformations. For TRPML1, we used the apo TRPML1 model PDB-5WJ5 to build the initial models, and the ML-SA1–bound TRPML1 model (PDB-5WJ9) to build the ML-SA5–TRPML1WT structure. These were then refined iteratively by manually fitting in Coot and Phenix. Due to the limited local resolution, the following residues in each structure were not built: apo TRPML2, 1–40, 172–174, 328–337, 520–566; (-)ML-SI3 TRPML2, 1–40, 172–174, 328–337, 520–566; (+)ML-SI3–bound TRPML2 (pre-open), 1–35, 171–179, 281–285, 331–339, 517–566; (+)ML-SI3–bound TRPML2 (open), 1–35, 171–179, 281–285, 331–339, 517–566; ML2-SA1–bound TRPML2, 1–40, 172–179, 328–339, 514–566; ML2-SA1/PI(3,5)P2–bound TRPML2, 1–35, 171–179, 281–285, 331–339, 520–566; ML2-SA1–bound TRPML1VA/AG, 1–46, 200–215, 293–295, 336–345, 526–580; (+)ML-SI3–bound TRPML1VA/AG (partially open), 1–59, 201–215, 293–295, 336–345, 527–580; (+)ML-SI3–bound TRPML1VA/AG (pre-open), 1–59, 201–215, 293–295, 336–345, 521–580; ML-SA5–bound TRPML1WT, 1–40, 202–216, 338–343, 527–580. Structural model validation was performed using Phenix 1.21 and MolProbity 4.355. Figures were prepared using HOLE 2.3.1, PyMOL 3.0, and ChimeraX 1.8.

Cell transfection and immunoblotting for TRPML1 constructs

For immunoblotting, the FLAG-tagged TRPML1WT and TRPML1VA/AG constructs were the same constructs used for protein purification, while the YFP-tagged TRPML2WT, TRPML2L414A, TRPML2Y496A, and TRPML2F457A were the same constructs used in patch clamp experiments. HEK293 cells were seeded onto 6-well plates at a density of 300 k cells per well in DMEM low glucose (Sigma) with 5% FCS (Gemini Bio) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Gibco). 24 h later, the cells were transfected with either the construct of interest, or empty vector as a control using Fugene6 (Promega). 48 h after the transfection, the cells were harvested and rinsed by PBS and lysed with Pierce RIPA buffer (Thermo Scientific) with the addition of EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche) and benzonase (Millipore Sigma). The cells were incubated with the lysis buffer for 30 min at 4 °C. After, the lysate was spun down for 10 min at 1000 x g, and the supernatant was analyzed by SDS-PAGE and subsequently incubated with primary antibodies against FLAG (anti-DDDDK-tag mAb, MBL Life Sciences, 1:3000 dilution), GFP (anti-GFP rabbit mAb, Cell Signaling Technology, 1:1000 dilution), or actin (anti-Beta Actin mouse mAb, Cell Signaling Technology, 1:1000 dilution) as a control overnight. The next morning, the blots were washed and incubated with HRP-linked secondary antibodies against either mouse or rabbit (anti-mouse IgG HRP-linked or anti-rabbit IgG HRP-linked antibodies, Cell Signaling Technology, both at 1:2000 dilutions) for 1 h at room temp and developed. Experiments were repeated at least 3 times with similar results each time.

cDNA constructs and cell transfection for electrophysiological experiments

Human wild-type TRPML1 and TRPML2 (C-terminally tagged with YFP) were subcloned into the pcDNA3.1 expression vector9. All point mutations were manufactured and generated using the CloneEZ method, site-directed mutagenesis (Genscript Biotech, Netherlands). HEK293 cells (ATCC) were maintained in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) (Gibco, containing 1 g/L glucose) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Thermo Fisher) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Sigma-Aldrich). HEK293 cells were seeded onto poly-L-lysine-coated coverslips at a density of 2.5 ×104 cells. The cells were transiently transfected with plasmid DNA at a concentration of 0.5 µg using 3 µL TurboFect Transfection Reagent (Thermo Scientific). 24 h post-transfection, the cells were treated overnight with apilimod (Axon Medchem) at a concentration of 1 µM to induce lysosomal enlargement. All cultures were incubated at 37 °C under a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2.

Manual whole endolysosomal and inside-out patch-clamp experiments

Manual whole endolysosomal patch-clamp recordings were conducted as previously described56. In the case of TRPML2L414A and TRPML2F457A mutants with TRPML2WT as control, standard inside-out patch-clamp was performed57. Briefly, HEK293 cells transfected with constructs tagged at the C-terminus with YFP were treated overnight at 37 °C with 5% CO2 in 1 µM apilimod (Axon Medchem) to enlarge endolysosomes. Before the patch-clamp experiments, apilimod was washed out. Enlarged endolysosomes were carefully released from the cell membrane using a glass pipette. Recordings were obtained at room temperature, with only one endolysosome recorded per coverslip.

Currents were recorded using an EPC-10 patch-clamp amplifier (HEKA, Lambrecht, Germany) and PatchMaster software (v2x90.4, HEKA), allowing data digitization at 40 kHz, filtering at 2.8 kHz, pre-analysis, and cancellation of capacitive transients. Borosilicate glass pipettes were polished to achieve resistances between 6–9 MΩ.

The pipette solution (simulating the luminal endolysosomal environment) contained 140 mM sodium methanesulfonate (NaMSA), 5 mM potassium methanesulfonate (KMSA), 2 mM calcium methanesulfonate (CaMSA), 1 mM CaCl2, 10 mM HEPES, and 10 mM MES, with the pH adjusted to 4.6 using MSA or 20 mM HEPES with pH adjusted to 7.2 with NaOH. The bath solution (mimicking the cytosolic environment) consisted of 140 mM KMSA, 5 mM KOH, 4 mM NaCl, 0.39 mM CaCl2, 1 mM EGTA, and 20 mM HEPES, with the pH adjusted to 7.2 using KOH.

All compounds were prepared as high-concentration stock solutions and added to the bath to achieve the desired final concentrations. The bath solution was completely exchanged when applying these compounds. Voltage ramps (500 ms, from −100 to +50 mV) were applied every 5 s at a holding potential of 0 mV, with current amplitudes at −100 mV extracted from individual ramp recordings. Liquid junction potential corrections were applied. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism software (version 10.2.3).

Construction of model

The “open” and “pre-open” TRPML2 structures (residues 340-519) were modeled in the lipid bilayer as follows. The atomic coordinates were constructed from the transmembrane domains of the TRPML2 ( + )ML-SI3 bound pre-open (residues 340-517) and open (residues 340-519) structures; hydrogen atoms were constructed using H-build from CHARMM58. To assign an initial protonation pattern for each structure at pH 7, the pKa values of all titratable residues were calculated with PROPKA59. Force field parameters for (+)ML-SI3 were obtained using the CGenFF server60. Next, using the OPM database61 and the CHARMM-GUI62, the (+)ML-SI3-bound protein was inserted in a lipid bilayer consisting of cholesterol (10%), 2,3-dioleoyl-D-glycero-1-phosphatidylglycerol (DOPG) (10%), and 3-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-D-glycero-1-Phosphatidylcholine (POPC) (80%). Next, the protein-membrane system was solvated in explicit TIP3 water63 with 150 mM KCl concentration. The models of the final solvated systems are displayed in Table 1:

Table 1.

TRPML2 simulation conditions, one simulation per model was performed

| TRPML2 conformation | K+ ions | Cl- ions | TIP3 water molecules | Total atoms | Simulation box dimensions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| “pre-open” | 126 | 87 | 31,805 | 157,399 | 127.13 Å × 127.13 Å × 106.11 Å |

| “open” | 124 | 85 | 31,442 | 156,430 | 127.13 Å × 127.26 Å × 105.11 Å |

Geometry optimizations and molecular dynamics

Energy minimizations and geometry optimizations of each solvated (+)ML-SI3-protein-membrane complex were carried out with NAMD64 using the all-atom CHARMM36 parameter set for the protein and lipid molecules65 and the TIP3P model for water molecules63; the parameters for (+)ML-SI3 were obtained from the CGenFF server60. The initial geometry of each structure was optimized with two rounds of 100 steps of steepest descent (SD) energy minimization, followed by 100 adopted basis Newton-Raphson (ABNR) steps to remove any close contacts. The solvated (+)ML-SI3-protein-membrane complex was simulated with molecular dynamics (MD) at 310 K according to the following protocol: 1) equilibration MD with Langevin dynamics (time step of 1 fs) for 375 ps followed by Langevin dynamics (time step 2 fs) for 1.5 ns; 2) production MD with Langevin dynamics (time step 2 fs) for 200 ns. The simulations were carried out a totoal of n = 1 times.

To simulate a continuous system, periodic boundary conditions were applied; electrostatic interactions were summed with the Particle Mesh Ewald method66 (grid spacing ~0.88 Å; fftx 144, ffty 144, fftz 120). A nonbonded cutoff of 16.0 Å was used, and Heuristic testing was performed at each energy call to evaluate whether the nonbonded pair list should be updated. MD trajectories were analyzed with VMD (Version 1.94)67.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Source data

Acknowledgements

The Cryo-EM data were collected at the UT Southwestern Medical Center Cryo-EM Facility (funded in part by the CPRIT Core Facility Support Award RP170644). This research was supported in part by the computational resources provided by the BioHPC supercomputing facility located in the Lyda Hill Department of Bioinformatics, UT Southwestern Medical Center. URL: https://portal.biohpc.swmed.edu. We thank L. Esparza for tissue culture and C-H. Lee for discussion. This work was supported by NIH P01 HL160487, R35 GM149533, the Welch Foundation (I-1957) and The G. Harold and Leila Y. Mathers Charitable Foundation (to X.L.) as well as by DFG grants GR4315/2-2, GR4315/6-1, GR4315/7-1, SFB1328 A21 and TRR152 P04 (to C.G.).

Author contributions

P.S. and X.L. conceived the project with the help of M.F. P.S. purified proteins and carried out cryo-EM work with the help of A.H.; D.J., with the help of N.P.S., carried out functional characterization by electrophysiology. N.E-M. conducted the MD simulations. All the authors analyzed data and contributed to manuscript preparation. P.S., C.G., and X.L. wrote the paper.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Data availability

The data that support this study are available from the corresponding authors upon request. The 3D cryo-EM density maps have been deposited in the Electron Microscopy Data Bank under the accession numbers EMD-48139 (apo TRPML2 closed); EMD-48140 ((-)ML-SI3–bound TRPML2 closed); EMD-48141 ((+)ML-SI3–bound TRPML2 pre-open); EMD-48142 ((+)ML-SI3–bound TRPML2 open); EMD-48143 (ML2-SA1–bound TRPML2 pre-open); EMD-48144 (ML2-SA1/PI(3,5)P2–bound TRPML2 open); EMD-48135 (ML2-SA1–bound TRPML1VA/AG partially open); EMD-48136 ((+)ML-SI3–bound TRPML1VA/AG partially open); EMD-48137 ((+)ML-SI3–bound TRPML1VA/AG pre-open); and EMD-48138 (ML-SA5–bound TRPML1WT open). Atomic coordinates for the atomic model have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank under the accession number 9EKW (apo-TRPML2 closed); 9EKX ((-)ML-SI3–bound TRPML2 closed); 9EKY ((+)ML-SI3–bound TRPML2 pre-open); 9EKZ ((+)ML-SI3–bound TRPML2 open); 9EL0 (ML2-SA1–bound TRPML2 pre-open); 9EL1 (ML2-SA1/PI(3,5)P2–bound TRPML2 open); 9EKS (ML2-SA1–bound TRPML1VA/AG partially open); 9EKT ((+)ML-SI3–bound TRPML1VA/AG partially open); 9EKU ((+)ML-SI3–bound TRPML1VA/AG pre-open); and 9EKV (ML-SA5–bound TRPML1WT open). Initial/final PDB states for MD simulations are provided as Source data. The source data underlying Figs. 4a–c, 5c, and Supplementary Fig. 8 are provided with this paper. Previously published structures referred to in this paper include: 5WJ5, 7DYS, 6AYE, 5T4D, 5WJ9, 6MHO, 6DVZ, and 6D1W. Source data are provided with this paper.

Competing interests

These authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Philip Schmiege, Dawid Jaślan.

Contributor Information

Christian Grimm, Email: Christian.Grimm@med.uni-muenchen.de.

Xiaochun Li, Email: xiaochun.li@utsouthwestern.edu.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-025-60710-8.

References

- 1.Venkatachalam, K. & Montell, C. TRP channels. Annu. Rev. Biochem.76, 387–417 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Taberner, F. J., Fernandez-Ballester, G., Fernandez-Carvajal, A. & Ferrer-Montiel, A. TRP channels interaction with lipids and its implications in disease. Biochimica et. biophysica acta1848, 1818–1827 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rohacs, T. Phosphoinositide Regulation of TRP Channels: A functional overview in the structural era. Annu Rev. Physiol.86, 329–355 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Venkatachalam, K., Wong, C. O. & Zhu, M. X. The role of TRPMLs in endolysosomal trafficking and function. Cell Calcium58, 48–56 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fine, M. & Li, X. A structural overview of TRPML1 and the TRPML family. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol.278, 181–198 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang, W., Zhang, X., Gao, Q. & Xu, H. TRPML1: an ion channel in the lysosome. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol.222, 631–645 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garcia-Anoveros, J. & Wiwatpanit, T. TRPML2 and mucolipin evolution. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol.222, 647–658 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Plesch, E. et al. Selective agonist of TRPML2 reveals direct role in chemokine release from innate immune cells. Elife7, 10.7554/eLife.39720 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Chen, C. C. et al. A small molecule restores function to TRPML1 mutant isoforms responsible for mucolipidosis type IV. Nat. Commun.5, 4681 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang, X. et al. MCOLN1 is a ROS sensor in lysosomes that regulates autophagy. Nat. Commun.7, 12109 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Siow, W. X. et al. Lysosomal TRPML1 regulates mitochondrial function in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. J. Cell Sci.135, 10.1242/jcs.259455 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Spix, B. et al. Lung emphysema and impaired macrophage elastase clearance in mucolipin 3 deficient mice. Nat. Commun.13, 318 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yu, L. et al. Small-molecule activation of lysosomal TRP channels ameliorates Duchenne muscular dystrophy in mouse models. Sci. Adv.6, eaaz2736 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dong, X. P. et al. PI(3,5)P(2) controls membrane trafficking by direct activation of mucolipin Ca(2+) release channels in the endolysosome. Nat. Commun.1, 38 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Samie, M. et al. A TRP channel in the lysosome regulates large particle phagocytosis via focal exocytosis. Developmental cell26, 511–524 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang, X., Li, X. & Xu, H. Phosphoinositide isoforms determine compartment-specific ion channel activity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA109, 11384–11389 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leser, C. et al. Chemical and pharmacological characterization of the TRPML calcium channel blockers ML-SI1 and ML-SI3. Eur. J. medicinal Chem.210, 112966 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rather, M. A. et al. TRP channels: Role in neurodegenerative diseases and therapeutic targets. Heliyon9, e16910 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Riederer, E., Cang, C. & Ren, D. Lysosomal Ion Channels: What Are They Good For and Are They Druggable Targets?. Annu Rev. Pharm. Toxicol.63, 19–41 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen, C. C. et al. TRPML2 is an osmo/mechanosensitive cation channel in endolysosomal organelles. Sci. Adv.6, 10.1126/sciadv.abb5064 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Cheng, X., Shen, D., Samie, M. & Xu, H. Mucolipins: Intracellular TRPML1-3 channels. FEBS Lett.584, 2013–2021 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Karacsonyi, C., Miguel, A. S. & Puertollano, R. Mucolipin-2 localizes to the Arf6-associated pathway and regulates recycling of GPI-APs. Traffic8, 1404–1414 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rinkenberger, N. & Schoggins, J. W. Mucolipin-2 cation channel increases trafficking efficiency of endocytosed viruses. mBio9, 10.1128/mBio.02314-17 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Santoni, G. et al. Involvement of the TRPML mucolipin channels in viral infections and anti-viral innate immune responses. Front Immunol.11, 739 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hirschi, M. et al. Cryo-electron microscopy structure of the lysosomal calcium-permeable channel TRPML3. Nature550, 411–414 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhou, X. et al. Cryo-EM structures of the human endolysosomal TRPML3 channel in three distinct states. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol.24, 1146–1154 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen, Q. et al. Structure of mammalian endolysosomal TRPML1 channel in nanodiscs. Nature550, 415–418 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang, S., Li, N., Zeng, W., Gao, N. & Yang, M. Cryo-EM structures of the mammalian endo-lysosomal TRPML1 channel elucidate the combined regulation mechanism. Protein cell8, 834–847 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schmiege, P., Fine, M., Blobel, G. & Li, X. Human TRPML1 channel structures in open and closed conformations. Nature550, 366–370 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Song, X. et al. Cryo-EM structure of mouse TRPML2 in lipid nanodiscs. J. Biol. Chem.298, 101487 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gan, N. et al. Structural mechanism of allosteric activation of TRPML1 by PI(3,5)P2 and rapamycin. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America119, 10.1073/pnas.2120404119 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Fine, M., Schmiege, P. & Li, X. Structural basis for PtdInsP2-mediated human TRPML1 regulation. Nat. Commun.9, 4192 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schmiege, P., Fine, M. & Li, X. Atomic insights into ML-SI3 mediated human TRPML1 inhibition. Structure29, 1295–1302.e1293 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Viet, K. K. et al. Structure of the Human TRPML2 ion channel extracytosolic/lumenal domain. Structure27, 1246–1257.e1245 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shen, P. S. et al. The structure of the polycystic kidney disease channel PKD2 in lipid nanodiscs. Cell167, 763–773.e711 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sahoo, N. et al. Gastric acid secretion from parietal cells is mediated by a Ca(2+) efflux channel in the tubulovesicle. Dev. Cell41, 262–273.e266 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zubcevic, L. & Lee, S. Y. The role of pi-helices in TRP channel gating. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol.58, 314–323 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu, C. et al. A non-covalent ligand reveals biased agonism of the TRPA1 ion channel. Neuron109, 273–284.e274 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cao, E., Liao, M., Cheng, Y. & Julius, D. TRPV1 structures in distinct conformations reveal activation mechanisms. Nature504, 113–118 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zubcevic, L. et al. Cryo-electron microscopy structure of the TRPV2 ion channel. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol.23, 180–186 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Singh, A. K., McGoldrick, L. L. & Sobolevsky, A. I. Structure and gating mechanism of the transient receptor potential channel TRPV3. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol.25, 805–813 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tang, Q. et al. Structure of the receptor-activated human TRPC6 and TRPC3 ion channels. Cell Res28, 746–755 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zheng, W. et al. Hydrophobic pore gates regulate ion permeation in polycystic kidney disease 2 and 2L1 channels. Nat. Commun.9, 2302 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Huang, G. et al. High-resolution structures of human Na(v)1.7 reveal gating modulation through alpha-pi helical transition of S6(IV). Cell Rep.39, 110735 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Grimm, C. et al. A helix-breaking mutation in TRPML3 leads to constitutive activity underlying deafness in the varitint-waddler mouse. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA104, 19583–19588 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Goehring, A. et al. Screening and large-scale expression of membrane proteins in mammalian cells for structural studies. Nat. Protoc.9, 2574–2585 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Guo, X. et al. Structure and mechanism of human cystine exporter cystinosin. Cell185, 3739–3752.e18 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Punjani, A., Rubinstein, J. L., Fleet, D. J. & Brubaker, M. A. cryoSPARC: algorithms for rapid unsupervised cryo-EM structure determination. Nat. Methods14, 290–296 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wagner, T. et al. SPHIRE-crYOLO is a fast and accurate fully automated particle picker for cryo-EM. Commun. Biol.2, 218 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zivanov, J. et al. New tools for automated high-resolution cryo-EM structure determination in RELION-3. Elife7, 10.7554/eLife.42166 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 51.Jumper, J. et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature596, 583–589 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pettersen, E. F. et al. UCSF Chimera-a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput Chem.25, 1605–1612 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Emsley, P. & Cowtan, K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D. Biol. Crystallogr60, 2126–2132 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Adams, P. D. et al. PHENIX: a comprehensive python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr D. Biol. Crystallogr66, 213–221 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chen, V. B. et al. MolProbity: all-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Crystallogr D. Biol. Crystallogr66, 12–21 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chen, C. C. et al. Patch-clamp technique to characterize ion channels in enlarged individual endolysosomes. Nat. Protoc.12, 1639–1658 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hamill, O. P., Marty, A., Neher, E., Sakmann, B. & Sigworth, F. J. Improved patch-clamp techniques for high-resolution current recording from cells and cell-free membrane patches. Pflug. Arch.391, 85–100 (1981). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Brooks, B. R. et al. CHARMM: A program for macromolecular energy, minimization, and dynamics calculations. J. Comput. Chem.4, 30 (1983). [Google Scholar]

- 59.Li, H., Robertson, A. D. & Jensen, J. H. Very fast empirical prediction and rationalization of protein pKa values. Proteins61, 704–721 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Vanommeslaeghe, K. et al. CHARMM general force field: A force field for drug-like molecules compatible with the CHARMM all-atom additive biological force fields. J. computational Chem.31, 671–690 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lomize, M. A., Lomize, A. L., Pogozheva, I. D. & Mosberg, H. I. OPM: orientations of proteins in membranes database. Bioinformatics22, 623–625 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jo, S., Kim, T., Iyer, V. G. & Im, W. CHARMM-GUI: a web-based graphical user interface for CHARMM. J. computational Chem.29, 1859–1865 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jorgensen, W., Chandrasekhar, J., Madura, J., Impey, R. & Klein, M. Comparison of simple potential functions for simulating liquid water. J. Chem. Phys.79, 9 (1983). [Google Scholar]

- 64.Phillips, J. C. et al. Scalable molecular dynamics with NAMD. J. computational Chem.26, 1781–1802 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.MacKerell, A. D. et al. All-atom empirical potential for molecular modeling and dynamics studies of proteins. J. Phys. Chem. B102, 3586–3616 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Essmann, U. et al. A smooth particle mesh Ewald method. J. Chem. Phys.103, 16 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- 67.Humphrey, W., Dalke, A. & Schulten, K. VMD: Visual molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Graph Model14, 33–38 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support this study are available from the corresponding authors upon request. The 3D cryo-EM density maps have been deposited in the Electron Microscopy Data Bank under the accession numbers EMD-48139 (apo TRPML2 closed); EMD-48140 ((-)ML-SI3–bound TRPML2 closed); EMD-48141 ((+)ML-SI3–bound TRPML2 pre-open); EMD-48142 ((+)ML-SI3–bound TRPML2 open); EMD-48143 (ML2-SA1–bound TRPML2 pre-open); EMD-48144 (ML2-SA1/PI(3,5)P2–bound TRPML2 open); EMD-48135 (ML2-SA1–bound TRPML1VA/AG partially open); EMD-48136 ((+)ML-SI3–bound TRPML1VA/AG partially open); EMD-48137 ((+)ML-SI3–bound TRPML1VA/AG pre-open); and EMD-48138 (ML-SA5–bound TRPML1WT open). Atomic coordinates for the atomic model have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank under the accession number 9EKW (apo-TRPML2 closed); 9EKX ((-)ML-SI3–bound TRPML2 closed); 9EKY ((+)ML-SI3–bound TRPML2 pre-open); 9EKZ ((+)ML-SI3–bound TRPML2 open); 9EL0 (ML2-SA1–bound TRPML2 pre-open); 9EL1 (ML2-SA1/PI(3,5)P2–bound TRPML2 open); 9EKS (ML2-SA1–bound TRPML1VA/AG partially open); 9EKT ((+)ML-SI3–bound TRPML1VA/AG partially open); 9EKU ((+)ML-SI3–bound TRPML1VA/AG pre-open); and 9EKV (ML-SA5–bound TRPML1WT open). Initial/final PDB states for MD simulations are provided as Source data. The source data underlying Figs. 4a–c, 5c, and Supplementary Fig. 8 are provided with this paper. Previously published structures referred to in this paper include: 5WJ5, 7DYS, 6AYE, 5T4D, 5WJ9, 6MHO, 6DVZ, and 6D1W. Source data are provided with this paper.