ABSTRACT

The ability to parasitize living hosts as well as decompose dead organic matter is both common and widespread across prokaryotic and eukaryotic taxa. These parasitic decomposers have long been considered merely accidental or facultative parasites. However, this is often untrue: in many cases, parasitism is integral to the ecology and evolution of these organisms. Combining life cycle information from the literature with a generalised eco‐evolutionary model, we define four distinct life history strategies followed by parasitic decomposers. Each strategy has a unique fitness expression, life cycle, ecological context, and set of evolutionary constraints. Correctly classifying parasitic decomposers is essential for understanding their ecology and epidemiology and directly impacts efforts to manage important medical and agricultural pathogens.

Keywords: biotroph‐necrotroph spectrum, entomopathogens, evolution of parasitism, facultative parasites, life history, nosocomial diseases, opportunistic pathogens, sapronosis, trade‐offs

Despite being widespread, common, and important to medicine and agriculture, parasitic decomposers are poorly understood. Drawing on literature spanning bacteria to animals, we show that these deadly decomposers follow similar life history strategies regardless of taxon. We define four such strategies, providing diverse biological examples and deriving a unique R 0 expression for each.

1. Introduction

Parasitism of living hosts and decomposition of dead organic material appear, at first glance, to be mutually exclusive trophic strategies. In other words, parasites exploit living hosts, whereas saprotrophs exploit dead matter, and these two strategies come with unique challenges. Parasites often depend on their hosts for metabolic or enzymatic products and typically cannot be cultured on simple media (Solomon et al. 2003). Further, they must simultaneously overcome host defences and balance exploitation of a limited, renewable resource against the reduction in host life span (and thus parasite life span) associated with that exploitation (Cressler et al. 2016). Saprotrophs, in contrast, are often biosynthetically self‐sufficient and have relatively simple nutritional requirements (Solomon et al. 2003) but face intense competition with other decomposers for a resource that is limited and non‐renewable. Given that conditions for parasitism are at least partly orthogonal to those for saprotrophy, it stands to reason that adaptations for one strategy could trade off against adaptations for the other. Indeed, while evidence is sometimes mixed (Daniels 1963; Parmeter 1970), there is a large amount of empirical evidence for trade‐offs between parasitism and saprotrophy, spanning fungi (Abang et al. 2006; Akinsanmi et al. 2007; Boddy and Hiscox 2016; Butler 1953; Delaye et al. 2013; Hoyt et al. 2021; Jaffee and Zehr 1985; Kelly et al. 2021; Lee et al. 2021; Norros et al. 2023; Olson et al. 2012; Parmeter 1970; Reynolds et al. 2015; del Rocío Reyes‐Montes et al. 2016; Samson et al. 2013), oomycota (Cerenius and Söderhäll 1985), bacteria (Campbell et al. 2021; Godfray et al. 1999), and even animals (Stevens et al. 2006). Given these trade‐offs, species that combine these strategies—i.e., parasitic decomposers—would seemingly be outcompeted by obligate parasites when infecting live hosts, while likewise being outcompeted by obligate saprotrophs when exploiting non‐living matter.

Yet many organisms are capable of both parasitism and saprotrophy. That parasitism and saprotrophy exist on a spectrum has been recognised since the late 19th century (de Bary 1887; Hueppe 1886; Rice 1935; Smith 1887; van Tieghem and le Monnier 1873). While many familiar organisms occupy the extremes of this spectrum, capable of only parasitism or only saprotrophy, a surprising diversity of life spans its middle reaches. Various terms have been used to describe these “intermediate” organisms. Early mycologists coined the terms “facultative parasite” and “facultative saprophyte,” emphasising the idea that such organisms were accidentally straying outside of their life history wheelhouse (de Bary 1887; van Tieghem and le Monnier 1873). Around the same time, bacteriologists adopted the similar “facultative septic form” (Hueppe 1886), and later introduced “necroparasites” and “half‐parasites” to denote finer gradations within the parasitic decomposers (Bail 1911). Plant pathologists adopted the “biotroph‐necrotroph” spectrum to classify pathogens that exploit living plant tissues (“bio‐”) or kill plant tissues and exploit the dead material (“necro‐”) (Lewis 1973). Epidemiologists, recognising the substantial number of human infections caused by organisms that typically reproduce outside of a living host, coined the concept of “sapronoses”: diseases (nosos) caused by organisms that primarily obtain nutrition from non‐living organic material (sapros) (Terskikh 1958). While the definition of sapronoses has been inflated since its inception to include nearly any pathogens transmitted from “environmental” sources (Belov and Kulikalova 2016; Belov 2017; Belov and Kuzin 2017; Litvin et al. 2010; Pushkareva et al. 2010), there is growing recognition that a more constrained definition hewing closer to the etymological roots of the term is most useful (Belov and Kulikalova 2016; Belov 2017; Belov and Kirov 2018; Belov and Kuzin 2017; Domaradskiĭ 1988; Petrovskaia 1990). Recent estimates suggest that approximately 33% of human and animal disease‐causing agents can be classified as sapronoses (Kuris et al. 2014).

This glut of jargon is partly responsible for the fact that parasitic decomposers are poorly understood, despite being quite common and directly impacting human, animal, and crop health. Explicit incorporation of parasitic decomposers into formal epidemiological, ecological, and evolutionary models has been stymied by unclear definitions, conflation of unrelated life histories, taxonomic pigeon‐holing, and an unfortunate tendency of researchers to either focus on a single aspect of the life cycle (e.g., parasitism) while ignoring others, or to dismiss such organisms as mere “facultative parasites” with uninteresting dynamics.

Here, we seek to address the uncertainty surrounding parasitic decomposers in three ways. First, we simplify the tangle of conflicting and often vaguely specified jargon used to classify parasitic decomposers by defining four distinct life history strategies employed by such organisms regardless of their taxonomy or that of their hosts (Table 1). Our new classification system divides parasitic decomposers according to where they are able to grow, develop, and/or reproduce (i.e., on living and/or decaying matter), and their transmission routes (i.e., from living to living, living to decomposing, decomposing to living, or decomposing to decomposing matter). Second, we present a taxonomically diverse range of exemplar species to serve as case studies for each of the four life history strategies proposed here. Our intent is not to exhaustively classify all known parasitic decomposers using our system, but rather to demonstrate that living things across taxa seem to naturally group together according to the criteria we outline here. Third, we leverage an existing mathematical framework to show that each of the four life history strategies is associated with a unique fitness expression. Analysing these fitness expressions in the context of trade‐offs between parasitic ability and decomposition ability reveals unique ecological and evolutionary insights into the different strategies.

TABLE 1.

The four life history strategies employed by parasitic decomposers can be distinguished from one another, and from obligate parasites and obligate saprotrophs, by their non‐zero transmission parameters.

| Life history strategy | Transmits from | Example | Synonyms | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dead to dead: | Living to dead: | Dead to living: | Living to living: | |||

| Parasaprotroph | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Fusarium oxysporum—This fungus produces spores both when infecting living hosts and infesting dead plant matter, and spores can colonise both living and dead material. Mycelia can spread to new live or dead substrate. Vertical transmission is possible. | Facultative parasite1, entomopathogen2, facultative saprotroph3,4,5, hemibiotroph5,6, necrotroph4,5, anthropophilic dermatophyte7, zoophilic dermatophyte7, certain myiatic flies and saproxylic insects (see text) |

| Opportunistic sapronotic agent | Yes | Yes | Aspergillus fumigatus —This fungus grows and reproduces on dead organic material, but occasionally proliferates in immunocompromised individuals. However, host‐to‐host and host‐to‐non‐living transmission is impossible. | Facultative parasite1, opportunistic parasite8, sapronotic agent9,10, facultative necrotroph4,5 | ||

| Adapted sapronotic agent | Yes | Yes | Yes | Rhodococcus equi —This bacterium mainly decomposes herbivore faeces, but can transmit to hosts that inhale or consume infested materials. The bacterium proliferates in infected hosts and returns to the environment in host faeces to re‐enter the decomposer cycle, but typically does not transmit from host‐to‐host. | Facultative parasite1, opportunistic parasite8, sapronotic agent9,10, obligate biotroph4,5, hemibiotroph5,6, geophilic dematophyte7 | |

| Saprotrophic parasitoid | Yes | Yes | Ophiocordyceps unilateralis sensu lato—Infects and kills ant hosts, then decomposes the host while producing propagules. These propagules are only infective to live ants and cannot colonise other dead substrates. | Entomopathogen2, sapronotic agent9,10, parasitoid11 | ||

| Parasite | Yes | Ascaris lumbricoides—A nematode that infects humans. It produces eggs that pass with faeces into the environment. Ingestion of the eggs transmits the parasite. | Biotroph4,5, necrotroph4,12, parasitoid11, mycoheterotroph13, myiatic fly14,15 | |||

| Saprotroph | Yes | Phlebia tremellosus—A wood‐decaying fungus that transmits exclusively from dead organic material to dead organic material. | Saprobe16, saprophyte1, saprovore17, detritivore14, decomposer14, carrion feeder14, saproxylic insect18 | |||

Note: References: 1Young (1927); 2Roy et al. (2006); 3Hueppe (1886); 4Lewis (1973); 5Suzuki and Sasaki (2019); 6Luttrell (1974); 7Moskaluk and VandeWoude (2022); 8Symmers (1965); 9Kuris et al. (2014); 10Terskikh (1958); 11Lafferty and Kuris (2002); 12Rajarammohan (2021); 13Leake (1994); 14Stevens et al. (2006); 15Stevens and Wallman (2006); 16Martin (1932); 17Heal and MacLean (1975); 18Ulyshen (2018). An example of an organism adopting each strategy is presented. As demonstrated in the synonyms column, these strategies are taxon‐agnostic and do not clearly map onto host‐centric classification schemes.

In defining these life history strategies, we have attempted to adopt existing terminology as much as possible. Further, we do not seek to replace other classification systems (see Table 1), such as the nutrition‐source‐focused biotrophy‐necrotrophy spectrum long used by plant pathologists. Rather, we propose that our system, being applicable across taxa, is better suited to addressing questions of ecology, epidemiology, and evolution when considering parasitic decomposers.

Below, we present four strategies employed by parasitic decomposers to complete their life cycles. There are almost certainly exceptions, but the four strategies we identify here seem to be the most common. Each strategy spans taxa, as we demonstrate with examples from diverse phyla. For each strategy, we present the criteria used to define the strategy and the equation defining the basic reproductive number for each strategy, based on a simple epidemiological model (Suzuki and Sasaki 2019). We also discuss the trade‐offs between parasitism and saprotrophy revealed by the model and discuss possible trade‐offs related to virulence.

2. Parasaprotrophs: Those Who Can Do It All

The quintessential parasitic decomposer is an organism freely capable of reproducing in both parasitic and saprotrophic life stages and of transmitting along all possible routes. While we have attempted to avoid introducing neologisms here, we found that there is no satisfactory term in the literature to describe such a life history strategy (see above). “Facultative parasite” or “facultative saprotroph” are the closest such terms, but these are quite nebulously applied in the literature (Table 1) and rather strongly imply that the “facultative” aspect of the life cycle is an accident or a departure from optimality. As we show below, however, selection can strongly favour organisms capable of being both parasites and decomposers. To simplify the field and introduce clarity, we propose a term that combines the core themes of this synthesis—parasitism and saprotrophy—into a single word: parasaprotroph. This jack of all trades can infect living hosts, transmit from host‐to‐host, spread from live hosts to non‐living biomass (sometimes including dead hosts killed by the organism) and from there transmit back to live hosts. It can also spread from non‐living to non‐living biomass without requiring a live host. It is a life history generalist: therefore, we present it first because, as we shall see below, the life cycle of a parasaprotroph contains all other parasitic decomposer life history strategies on the parasite‐saprotroph spectrum.

Pathogenic fungi are often parasaprotrophs, capable of acting as both parasites and decomposers. The fungus Fusarium oxysporum Schltdl. is a prime example. It is a ubiquitous plant‐pathogenic fungus capable of infecting the roots of a range of plant species worldwide and causing wilt disease. F. oxysporum transmits between living hosts via direct host‐to‐host transmission or spores deposited into the soil (Gordon 2017) and through vertical transmission via infected seeds or stolons (Bennett et al. 2008; Pastrana et al. 2019). The fungus is also capable of growing saprotrophically: spores deposited in the soil from infected plants are able to colonise and grow on dead plant tissue (Gordon and Okamoto 1990), while the fungus can also spread from infested to uninfested plant residues (Gordon and Okamoto 1990). Spores produced via the saprophytic life cycle are able to infect living roots (Gordon 2017). Thus, all transmission routes are possible for Fusarium, diagnosing it as a parasaprotroph. The genus Armillaria is another example: a “forest pathogen,” it produces infective rhizomorphs and fruiting bodies from infected live trees and dead wood alike (Kedves et al. 2021; Lee et al. 2021). Similarly, some species of amphibian‐infecting chytrid fungus have been found to possess saprotrophic ability, capable of decomposing both dead host skin (Longcore et al. 1999) and plant matter (Frenken et al. 2017; Kelly et al. 2021) in addition to host‐to‐host transmission.

While common among fungi, parasaprotrophy is found in other phyla. Several Oomycota, including the plant‐infecting Pythium, can transmit between live hosts, colonise dead host and non‐host matter, and freely move between parasitic and saprotrophic forms (Fiore‐Donno and Bonkowski 2021; Hendrix and Campbell 1973; Kramer et al. 2016). The dangerous nosocomial (i.e., hospital‐acquired) bacterium Acinetobacter baumannii Bouvet & Grimont, 1986 can infect humans via direct transmission (Harris et al. 2019; Munoz‐Price et al. 2013; Spellberg and Bonomo 2013) and is commonly found proliferating saprotrophically in hospitals, soils, and in freshwater settings (Ahuatzin‐Flores et al. 2024). New substrates for decomposition can be inoculated via host‐derived aerosols (Munoz‐Price et al. 2013), while patients are frequently infected from “environmental” sources (Ahuatzin‐Flores et al. 2024). Even some animals can alternate between saprotrophy and parasitism. For example, some carrion‐feeding flies can infect and complete development in live hosts. While larvae of the common green bottle fly Lucilia sericata (Meigen, 1826) typically infest carrion, they can also infect open wounds of animals (including humans) and can cause serious pathology (Choe et al. 2016; Daniel et al. 1994; Hall 1997; Kaczmarczyk et al. 2011; Talar et al. 2004). This is especially problematic in sheep husbandry, as the ability of L. sericata to transmit between sheep, from sheep to carrion, and from carrion to sheep makes control of sheep strike quite difficult (Hall 1997). Likewise, many species of saproxylic (deadwood‐inhabiting) insects preferentially infest dead trees and break down dead wood as they develop. However, some of these decomposers will happily infect live plants that are weakened or otherwise cannot defend against attack (Dodds et al. 2023; Ulyshen 2018). Some invasive species, such as the emerald ash borer Agrilus planipennis Fairmaire, 1888, have switched from primarily infesting dead wood in the native range to infecting healthy, live hosts in their introduced range (Herms and McCullough 2014). Insects such as these can colonise dead trees, spread from dead host to dead host, infect living trees from dead trees, transmit from living trees to living trees, and colonise dead trees from living trees.

What unites these disparate organisms, from bacteria to fungi to animals, is that all are capable of (1) developing in either living hosts or dead biomass, and (2) transmitting between and among living hosts and dead biomass (Figure 1A, Table 1). We can formalise this verbal classification of parasaprotrophs by mathematically defining how such organisms transmit and reproduce. The basic reproductive number, R 0, is an expression of whole‐life‐cycle fitness (more precisely: “invasion fitness” when an organism is introduced to a naïve habitat (Brännström et al. 2013)). Deriving a mathematical expression for the R 0 of parasaprotrophic organisms will permit a rigorous definition of what, exactly, constitutes the parasaprotroph life history strategy. Importantly, as we shall see below, different strategies are characterised by different and unique expressions of R 0.

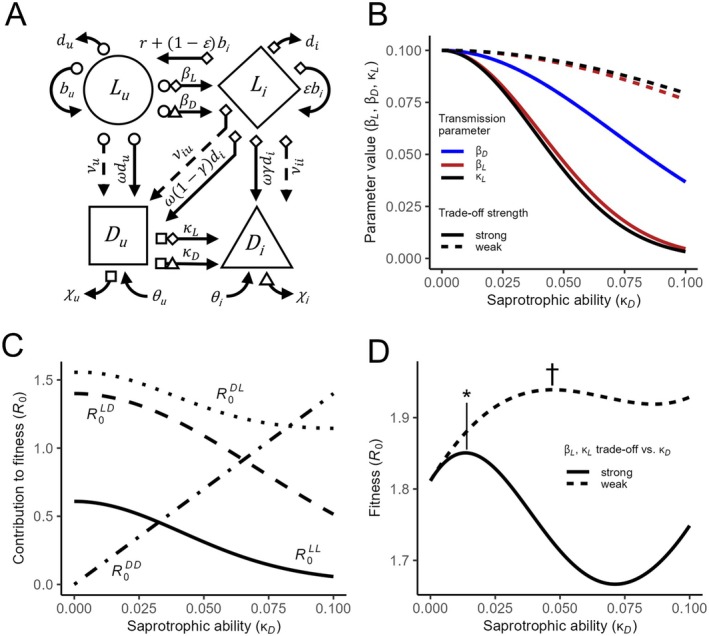

FIGURE 1.

Parasaprotrophs. (A) A flow diagram shows how organisms using the parasaprotroph strategy can both infect living hosts and infest dead organic substrates using a variety of pathways. Uninfected living hosts () can become infected hosts () by exposure to infectious propagules arising from either parasaprotroph‐infested dead organic substrates () or infected hosts () at the rates (dead‐to‐host transmission) and (host‐to‐host transmission), respectively. If vertical transmission is possible (), infected hosts () can give birth to new infected hosts at the rate . Both infected and uninfected hosts can produce dead uninfested substrate () either by shedding dead material ( or ) or dying ( or ). Infected hosts can also directly generate infested dead substrate, either by shedding already infested dead matter () or by dying and having the cadaver colonised by the already‐present parasaprotoph (). Infected live hosts () can produce propagules that colonise uninfested dead substrate (), converting it to infested substrate () at the living‐to‐dead transmission rate Propagules from infested dead substrate () can also colonise uninfested substrate () at the dead‐to‐dead transmission rate . Live uninfected and infected hosts die (, ) and give birth to uninfected offspring ( or ). Infected hosts () can recover from infection (). Uninfested and infested dead substrates ( and ) can replenish from some external source ( and ) and decay ( and ). Shapes at the tail of each arrow correspond to the shape of each state variable (, or ) and indicate which variable(s) are multiplied by the rate associated with the arrow to generate a transition to a new state (see Table 2 for parameter definitions). (B) Transmission trade‐offs assumed for numerical evaluation of the fitness equation (Equation 5) are shown as functions of saprotrophic ability (dead‐to‐dead transmission ). Assuming trade‐offs take the form , where is the parameter value, is its value when , and is some shape parameter, then the strength of the trade‐off between and the parameter in question is determined by . For “weak” trade‐offs, the value of was 5 for and and 10 for . For “strong” trade‐offs, the value of was 15 for and and 10 for . for all. Overlapping curves for (red) and (black) are offset for visualisation. (C) Fitness components of the parasaprotroph life cycle (Equation 6) vary with investment in saprotrophic ability (dead‐to‐dead transmission ). Curves displayed in this panel correspond to “strong” trade‐offs (dashed lines in panels B and D). The fitness components are saprotrophy (), parasitism (), infection of live hosts from infested dead material (), and infestation of dead material from live hosts (). When the full invasion expression (Equations 5 and 6) is evaluated (as in panel D), these components combine to produce whole‐life‐cycle fitness curves across a range of saprotrophic ability. (D) Numerical solutions to the invasion fitness expression (Equation 5) across a range of dead‐to‐dead transmission values (saprotrophic ability ) show that selection can favour the maintenance of “mixed” life history strategies utilising a balance of parasitism and saprotrophy. If trade‐offs with and are strong (dashed line), investment in parasitism (and reduced investment in saprotrophic ability ) may be favoured over investment in saprotrophy (asterisk indicates greatest ). If these trade‐offs are weak (solid line), a more mixed strategy is possible (dagger indicates greatest ). The strength of the trade‐off between and also influences the combinations of parameter values associated with an optimum, with weak trade‐offs favouring investment in saprotrophy (). .

To derive the R 0 expression of parasaprotrophs, we adapted an existing model (Suzuki and Sasaki 2019) that was originally created to describe the dynamics of fungal parasites and saprotrophs of plants. Generalising this prior work lets us represent the ecology of parasitic decomposers as a host‐focused compartmental model. This model considers the dynamics of “uninfected” living () and “uninfested” non‐living () organic material, as well as living hosts and non‐living organic material that has been “infected” with a parasite or “infested” with a decomposer ( and , respectively):

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

Living, uninfected hosts have a maximum birth rate of , which is modulated by population density relative to carrying capacity . Uninfected hosts die at a rate . They can become infected by propagules from either living, infected hosts at a rate or by infested non‐living organic material at a rate . Infected hosts give birth at a rate (modulated by density, as above); these newborns are infected with vertical transmission probability Infected hosts recover from infection at a rate and die at a rate .

Uninfected living hosts produce uninfested non‐living biomass , both by shedding exuvia (such as skin flakes or leaves) at the rate and by dying and becoming usable substrate at the rate , where is the average biomass of material produced by a living host. Likewise, infected living hosts may produce uninfested biomass at the rate , where is the probability that an infected host will become infested biomass immediately following host death. Infected hosts can also produce uninfested exuvia at the rate , or already infested exuvia at the rate (producing new infested non‐living organic material ). Uninfested non‐living biomass can be converted to infested biomass by propagules from living, infected hosts at a rate or from infested non‐living biomass at a rate . The flux terms and represent the input of uninfected and infected non‐living organic material from non‐host sources, whereas is removal of uninfested dead biomass (e.g., by competing decomposers) and is the removal rate of dead biomass when infested by the focal parasitic decomposer (see Table 2 for condensed definitions of these parameters).

TABLE 2.

Parameter definitions for ecological models, next‐generation matrices and expressions (see figure captions for parameter values used in each numerical analysis).

| Parameter | Definition | |

|---|---|---|

|

|

Live host (uninfected) abundance, density, and/or quality | |

|

|

Live host (infected) abundance, density, and/or quality | |

|

|

Non‐living organic substrate (uninfested) abundance, density, and/or quality | |

|

|

Non‐living organic substrate (infested) abundance, density, and/or quality | |

|

|

Maximum birth rate of uninfected hosts | |

|

|

Maximum birth rate of infected hosts | |

|

|

Carrying capacity of host population | |

|

|

Mortality rate of uninfected hosts | |

|

|

Mortality rate of infected hosts | |

|

|

Recovery rate | |

|

|

Vertical transmission rate | |

|

|

Host‐to‐host transmission rate | |

|

|

Dead substrate to host transmission rate | |

|

|

Host to dead substrate transmission rate | |

|

|

Dead substrate to dead substrate transmission rate (saprotrophic ability) | |

|

|

Live host to dead substrate conversion factor upon host death | |

|

|

Probability that an infected live host will become an infested cadaver at death | |

|

|

Decomposable exuvia production rate from uninfected hosts | |

|

|

Decomposable, uninfested exuvia production rate from infected hosts | |

|

|

Infested exuvia production rate from infected hosts | |

|

|

Uninfested dead substrate removal rate | |

|

|

Infested dead substrate removal rate (cadaver exploitation rate) | |

|

|

Decomposable uninfested substrate influx rate | |

|

|

Infested substrate influx rate | |

|

|

The fitness contribution of host‐to‐host parasitism | |

|

|

The fitness contribution of dead‐to‐dead saprotrophic transmission | |

|

|

The fitness contribution of propagules from dead substrate infecting live hosts | |

|

|

The fitness contribution of propagules from live hosts infesting dead substrate |

Having defined the above ecological model to describe parasaprotrophs, we can use the next‐generation matrix method (Diekmann et al. 1990; Diekmann and Heesterbeek 2000) to obtain a single equation defining (see Supporting Information S1 for calculations). Parasaprotrophs, having rather complicated life cycles, have a correspondingly complicated expression:

|

(5) |

However, this expression can be conceptualised in terms of discrete parts of the overall life cycle, each of which corresponds to an element of the next‐generation matrix (Suzuki and Sasaki 2019) (see Supporting Information S1). Rewriting Equation (5), we can express the parasaprotroph life cycle as

| (6) |

Here, is the contribution of parasitism, or host‐to‐host transmission, to the whole‐life‐cycle . This is not merely equivalent to direct host‐to‐host transmission, as includes both transmission between live hosts and transmission to new hosts from live hosts that have been killed by disease (see Supporting Information S1). Likewise, is the contribution of saprotrophy, or dead‐to‐dead transmission, to the invasion fitness of the whole life cycle. The terms and correspond to transmission from non‐living material to live hosts, and to transmission from live hosts to non‐living material, respectively (see the Supporting Information S1 for a full discussion and definitions of these terms).

The utility of having an expression for , whether in the form of Equations (5) or (6), is that it lets us explore how trade‐offs among different aspects of the life cycle (Equation 6) or different parameters (Equation 5) influence the fitness of parasaprotrophs. While an adaptive dynamics analysis is beyond the scope of this synthesis, simple numerical evaluation of can yield some insight into conditions for the existence of parasitic decomposer life history strategies. For example, if saprotrophic ability (, which is directly proportional to ) trades off against the transmission parameters , , and (i.e., against , , and ), the strength of such trade‐offs determines the optimum balance between parasitism and saprotrophy in the mixed life cycle (Figure 1B–D).

We might predict that parasaprotrophs should be selected to be highly virulent, as high virulence directly increases the fitness of the decomposer phase by producing more dead material (Pandey et al. 2022). However, virulence in parasaprotrophs is often quite variable or low. Fungi in the “Rhizoctonia” group, for instance, often have unpredictable effects on host mortality even within individual strains (Parmeter 1970). It is not immediately clear, from an evolutionary standpoint, why this might be the case. Physiological constraints likely play a role in preventing the evolution of hyper‐virulent “deadly” decomposers: virulence relies at least in part on parasitic ability (e.g., or specific transmission parameters such as host‐to‐host transmission or host‐to‐non‐living transmission ) and, because parasitic ability and saprotrophic ability must be orthogonal to some degree, there is likely some trade‐off limiting virulence. Indeed, solutions to the fitness expression (Equation 5) highlight this possibility. When trade‐offs between saprotrophic ability (non‐living‐to‐non‐living colonisation rate ) and virulence‐associated parasitic ability ( or ) are weak (Figure 1B, dashed lines), there is little selective pressure against maintaining parasitic ability: the curve is relatively flat (Figure 1D, dashed line). This could permit the maintenance of unpredictable or highly variable parasitic ability in parasaprotrophs. In contrast, strong trade‐offs (Figure 1B, solid lines) push the optimum strategy towards either pure parasitism or pure saprotrophy (Figure 1D, solid line). Exploration of virulence evolution in parasaprotrophs is a promising avenue of future research.

While parasaprotrophs may be the exemplar of the group, many parasitic decomposers do not have such free‐wheeling and complicated life cycles. In these cases, simplifies considerably.

3. Opportunistic Sapronotic Agents

A sapronosis is a disease which spreads from non‐living biomass to living hosts (see Section 1), and the organisms that cause such diseases are sapronotic agents. An opportunistic sapronotic agent is an organism that can opportunistically or “accidentally” cause infection, but which only reproduces as a saprotroph (Figure 2A, Table 1). Much of the literature and theory concerning parasitic decomposers focuses on opportunistic sapronoses (Belov and Kulikalova 2016; Kuris et al. 2014). This is a medically important category, as immunocompromised or otherwise stressed hosts are most at risk for infection by opportunistic sapronotic agents, with hospital‐associated transmission being an especially important avenue for infection (Brusina 2015; Kuris et al. 2014).

FIGURE 2.

Opportunistic sapronotic agents. (A) A flow diagram shows how organisms using the opportunistic sapronosis strategy can only produce infections in live hosts from the decomposition part of the life cycle. Refer to the caption for Figure 1 for a detailed description of the transitions evident in this life cycle, and see Table 2 for parameter definitions. (B) Numerical solutions to the invasion fitness expression (Equation 7) show that, because infections cannot contribute to fitness, investment in greater saprotrophic ability (the dead substrate to dead substrate transmission rate ) is always favoured. Increasing the abundance or quality of dead substrate () (solid line) increases the per‐unit payoff of investment in . (C) If investment in is a saturating function (here represented as , where and ), then there may be little cost to maintaining some level of parasitic ability at the expense of saprotrophic ability () if investment in saprotrophic ability is saturated.

A common agent of opportunistic sapronoses is Aspergillus fumigatus Fresen., which can cause aspergillosis. This fungus is a ubiquitous saprotroph (Latgé and Chamilos 2019), the airborne conidia of which are present in nearly every cubic meter of air in human‐occupied areas worldwide (Lacey 1996; Mullins et al. 1976). The lung tissues of up to one third of all healthy adult humans contain A. fumigatus conidia (Denning et al. 2011). While typically harmless, these conidia can germinate and proliferate inside of immunocompromised individuals, leading to devastating and deadly disease. The primary, and perhaps sole, habitat permitting A. fumigatus reproduction and dissemination is non‐living biomass. This fungus cannot transmit from host‐to‐host (), and does not appear capable of transmission from infected hosts to non‐living biomass () (Tekaia and Latgé 2005). Infection of living hosts from airborne conidia () is accidental, and such infection does not contribute to the fitness of A. fumigatus (Figure 2A).

A bacterial example of opportunistic sapronosis is infection by Serratia marcescens Bizio, 1823. This Gram‐negative species, often encountered as a pink or reddish film in bathrooms and other moist areas, is responsible for a large proportion of hospital‐acquired infections worldwide (Grimont and Grimont 1992; Hejazi and Falkiner 1997; Mahlen 2011). It is capable of growing on an extremely wide variety of organic substrates, including petroleum‐based plastics, fatty acids in soaps, and organic compounds in disinfectants (Hejazi and Falkiner 1997). Transmission from these substrates to human hosts can occur via several pathways, including inhaled aerosols (e.g., coughing or sneezing), contaminated medical equipment, contaminated antiseptics and medications, and wound inoculation (Mahlen 2011). While medical workers have been implicated in outbreaks of hospital‐acquired S. marcescens (Mahlen 2011), there is as yet no strong evidence of human‐to‐human transmission of the pathogen. This bacterium reproduces and disseminates as a saprotroph, and infection of living hosts does not appear to contribute to its fitness.

To be classified as an opportunistic sapronotic agent, an organism must meet two criteria (Table 1): (1) it grows/develops and produces propagules in or on non‐host dead biomass (), and (2) when infecting a living host, it does not produce viable propagules (or produces a negligible amount; ). Opportunistic sapronotic agents, lacking any ability for host‐to‐host or host‐to‐dead‐biomass transmission, have a fitness equal to (see Supporting Information S1 for calculations):

| (7) |

Because living hosts do not contribute to the fitness of opportunistic sapronotic agents (the latter are not capable of decomposing any host‐derived biomass) (Figure 2A), any investment in parasitic ability would be “wasted.” This investment would thus be detrimental if it came at the expense of the organism's ability as a saprotroph (Figure 2B,C). Therefore, the optimum strategy for an organism employing this life history strategy is always to maximise saprotrophic ability (, equivalently ). Parasitic ability would thus be reduced in the presence of any trade‐off between the two. Any “accidental” infective ability displayed by opportunistic sapronotic agents, therefore, would likely not trade off strongly against saprotrophic ability and may simply be the expression of saprotrophic behaviours in a living host. Alternatively, if investment in saprotrophic ability saturates (Figure 2C) there may be little selective pressure against maintaining some amount of parasitic ability at high levels of saprotrophy, even if that ability is “wasted.”

Due to the lack of host–parasite coevolution, some authors have proposed that sapronotic agents in general are likely to be highly virulent (Belov and Kulikalova 2016; Kuris et al. 2014). High virulence could also arise from selection for rapid saprotrophic growth. Alternatively, a trade‐off between virulence (as part of parasitic ability) and saprotrophic ability could work to selectively reduce virulence, as virulence contributes nothing to fitness. In either case, it may be more appropriate to say that virulence is not predictable for this class of organism: lack of coevolution could just as easily permit avirulence as virulence.

4. Adapted Sapronotic Agents

Whereas in opportunistic sapronoses parasitism makes a negligible contribution to the infectious agent's population dynamics, parasitism can have a profound effect on the dynamics of adapted sapronotic agents. The primary discriminant between the two categories of sapronosis is that adapted sapronotic agents produce propagules as parasites that transmit to new dead biomass, while opportunistic sapronotic agents do not (Figure 3A, Table 1). A consequence of this is that adapted sapronotic agents are not typically limited to immunocompromised or weakened hosts. Another important difference is that adapted sapronotic agents are not restricted to non‐host‐derived dead biomass for decomposition. Material such as abscised leaves, shed exoskeletons or skins, or host waste can be saprotrophically exploited by these organisms.

FIGURE 3.

Adapted sapronotic agents. (A) A flow diagram shows how organisms using the adapted sapronosis strategy can only infect live hosts via transmission from decomposers, but infected hosts can themselves contribute to the decomposer cycle. Refer to the caption for Figure 1 for a detailed description of the transitions evident in this life cycle, and see Table 2 for parameter definitions. (B) Assuming parameter trade‐offs take the form , where is the parameter value, is its value when , and is some shape parameter, then the strength of the trade‐off between and either or is determined by . The value of was 10 for “weak” trade‐offs and 15 for “strong” trade‐offs. (C) Numerical solutions to the invasion fitness expression (Equation 8) show that, if abundance or quality of live hosts () is low relative to that of dead substrate () (red lines), saprotrophy is likely favoured regardless of trade‐off strength. However, when live host abundance or quality is high, the contribution of parasitism to the life cycle increases to the point where selection favours sacrificing some saprotrophic ability to enhance parasitism. Adapted sapronoses thus become possible (black lines). When adapted sapronosis is possible, strong trade‐offs (solid line) favour less investment in saprotrophic ability and more investment in live to dead transmission or dead to live transmission (dagger). Weaker trade‐offs (dashed line) permit reduced investment in or and increased saprotrophic ability () (asterisk). Parameters not listed in figure: .

Vibrio cholerae Pacini, 1854, the causative agent of cholera, is an example of an adapted sapronotic agent. This bacterium proliferates as a saprotroph in freshwater or brackish environments (Lutz et al. 2013; Vezzulli et al. 2010), where it is often found attached to crustacean exoskeletons (Colwell et al. 1977; Erken et al. 2015; Huq et al. 1983; Vezzulli et al. 2010). Upon ingestion by a human, pathogenic strains rapidly proliferate and are expelled from the body via diarrhoea, where they return to the saprotrophic cycle (Almagro‐Moreno and Taylor 2013; Faruque et al. 1998). Importantly, direct transmission from human to human is uncommon: cholera is primarily spread via contaminated water and food. The importance of indirect transmission and the saprotrophic cycle to cholera epidemiology renders this disease difficult to model using traditional compartmental models that assume host‐to‐host spread (Usmani et al. 2021). While infection of living hosts can contribute to fitness, this contribution is mediated through the saprotrophic part of the life cycle (Figure 3A).

The actinomycete bacterium Rhodococcus equi (Magnusson, 1923) Goodfellow & Alderson 1977, capable of infecting multiple mammal species (including humans) but best known as a pathogen of horses, is another example of an adapted sapronotic agent. It primarily exists as a decomposer of herbivore faeces, but it can infect live hosts when they inhale or consume contaminated material (Vázquez‐Boland et al. 2013). While host‐to‐host transmission typically does not occur, R. equi readily transmits from infected hosts to non‐living organic substrate (faeces), upon which it thrives as a decomposer.

The diagnostic criteria of adapted sapronotic agents are (Table 1): (1) growth and propagule production in dead biomass (); (2) living hosts are only infected by propagules produced in dead biomass (); and (3) growth and propagule production in living hosts followed by transmission back to dead biomass (). Adapted sapronotic agents have a fitness equal to (see Supporting Information S1 for calculations):

| (8) |

We see from this expression that the invasion fitness of adapted sapronotic agents () depends on saprotrophic ability (, equivalently ), but also on host‐to‐dead‐biomass and dead‐biomass‐to‐host transmission (, or ). In this case, parasitic ability and saprotrophic ability are both capable of contributing to fitness. Because host‐to‐host transmission is impossible, some level of saprotrophic ability must be maintained. While trade‐offs between dead‐to‐dead transmission (), dead‐to‐living transmission (), and living‐to‐dead transmission () influence the importance of parasitism versus saprotrophy in the overall life cycle of adapted sapronotic agents (Figure 3B), the abundance or quality of living hosts () relative to that of dead biomass () could also be important. When live hosts are not particularly available, selection may disfavour maintenance of parasitic ability (Figure 3C, red lines). In contrast, relatively abundant or high‐quality live hosts may favour a mix of parasitism and saprotrophy (Figure 3C, black lines).

The ability of adapted sapronotic agents to proliferate inside infected hosts and transmit back to dead biomass can result in host–parasite coevolution, permitting selection on classical epidemiological parameters such as virulence. Indeed, some adapted sapronotic agents, such as V. cholerae , can be very virulent. If there is little or no trade‐off between virulence (e.g., death rate of infected hosts in excess of the baseline death rate of uninfected hosts ) and saprotrophic ability , but a trade‐off does exist between some other aspect of parasitism (e.g., ability to infect living hosts from non‐living organic material ) and saprotrophy, then selection may increase virulence if it is positively associated with transmission back to dead biomass . Mirroring the situation in “facultative” parasites (Pandey et al. 2022), selection for virulence in adapted sapronotic agents is strongly driven by the ecology of the organism in question.

5. Saprotrophic Parasitoids

A parasitoid is an organism that, upon infecting a host, necessarily drives that host's fitness to zero by way of mortality (Lafferty and Kuris 2002). Exclusive transmission of infectious propagules from dead host biomass to living hosts is the defining characteristic of saprotrophic parasitoids (Figure 4A). Unlike typical parasitoids, saprotrophic parasitoids are intimately associated with the cadaver of their host, sometimes for long periods after host death.

FIGURE 4.

Saprotrophic parasitoids. (A) While they must infect a living host () to complete their life cycle, saprotrophic parasitoids require a dead host body () within which to develop and produce propagules. Refer to the caption for Figure 1 for a detailed description of the transitions evident in this life cycle, and see Table 2 for parameter definitions. (B) We assume a positive association between cadaver exploitation (dead substrate removal rate ) and transmission to live hosts () modelled as . is the asymptotic maximum of (set to 2), while is the value of when is zero (set to 0.01). The shape parameter was 1 for a weak association (dashed line) and 2 for a strong association (solid line). (C) Numerical solutions to the invasion fitness expression (Equation 9) show that is maximised (asterisk) at a moderate exploitation rate if the association is strong (solid line), while a weaker association favours faster exploitation (dashed line). As indicated by the sharp increase in as approaches 0, any amount of transmission at very low levels of could favour a “cadaver preservation” strategy. Parameter not listed in figure: .

Perhaps the best‐known saprotrophic parasitoids are the entomopathogenic fungi, which infect and kill insects and other arthropods and produce propagules from the dead body (Roy et al. 2006). In some cases, as demonstrated in Ophiocordyceps and Hirsutella, the parasitoid can continue decomposing the host body and producing propagules for months to over a year following host death (Mongkolsamrit et al. 2012). Given the importance of the host cadaver's final position to the transmission of these parasites back to living hosts, saprotrophic parasitoids have evolved impressive mechanisms to ensure their hosts are correctly positioned for the dispersal of infectious propagules to new live hosts. Ophiocordyceps and Entomophthora, for example, are well‐known for their ability to manipulate the behaviour of infected hosts to maximise infection success (Andersen et al. 2009; Elya and De Fine Licht 2021; Lovett et al. 2020). Other entomopathogens, such as Erynia, grow strong anchoring structures to ensure the dead host remains in an optimum location despite wind, rain, or water currents (Roy et al. 2006). Those saprotrophic parasitoids that do not obviously manipulate host position just prior to death often have remarkable adaptations for environmental persistence.

A perhaps surprising example of a saprotrophic parasitoid is the causative agent of coccidiomycosis (Coccidioides sp.), which is increasingly recognised as having parasitoid dynamics in its non‐human mammalian hosts (Taylor and Barker 2019). These fungi typically infect and kill rodents, breaking down the resulting cadaver to produce resistant spores that persist for long periods in soil. Similarly, the anthrax bacterium Bacillus anthracis Cohn, 1872 is released into soils following the death and decomposition of its animal host; direct host‐to‐host transmission does not occur and growth in soil is negligible (Beyer and Turnbull 2009; Dragon and Rennie 1995). By some definitions, obligate necrotrophic fungi are saprotrophic parasitoids. These plant parasites infect living hosts, kill them, and grow and reproduce on the dead host tissues (Suzuki and Sasaki 2019). In other definitions, necrotrophs invade and kill plant tissues, but not necessarily the entire plant (Lewis 1973; Rajarammohan 2021); these are better considered as parasaprotrophs (see above).

The diagnosis of saprotrophic parasitoids requires (Table 1): (1) living hosts are infected by propagules originating from dead hosts (), never from living hosts () or non‐host dead biomass; (2) the parasite must kill the host to complete its life cycle (, where is the conversion factor of live hosts to usable dead biomass, is the probability that the infecting organism will successfully colonise its host's body after death, and is the death rate of infected hosts); and (3) non‐host dead biomass is not infested from living hosts () or from the host cadaver (). Saprotrophic parasitoids have fitness equal to (see Supporting Information S1 for calculations):

| (9) |

This invasion fitness expression shows that saprotrophic parasitoids must successfully colonise their host () after it dies () and becomes decomposable dead material (). This process is modulated by the recovery rate of infected hosts () and host death rate (). Uninfected hosts are infected by propagules released by infested dead material (the host cadaver) at the transmission rate , but only until the cadaver is fully exploited or otherwise removed (). While infested dead material is essential for the life cycle of saprotrophic parasitoids (Figure 4A), such material is exclusively generated from infected live hosts; this reflects the dependence of saprotrophic parasitoids on infection of living hosts. While this expression has parallels with , which is equivalent to (infection via infestation), we note that Equation (9) is actually a reduced form of (see Equation (5) and Supporting Information S1).

It is reasonable to assume that the exploitation/exhaustion rate of dead host biomass is positively related to transmission to live hosts . If a higher value of corresponds to a faster rate of resource acquisition from the host cadaver, then the transmission rate to new hosts could increase as increases (Figure 4B), creating a trade‐off analogous to the classic virulence—transmission trade‐off (Cressler et al. 2016), where transmission rate increases at the cost of a shorter duration of infectiousness. This leads to selection for an intermediate rate of exploitation (Figure 4C). If some amount of transmission is possible at low exploitation rates, and competition with other decomposers is low, saprotrophic parasitoids might be selected to “preserve” the host body (i.e., is very low) and continually emit a trickle of propagules for long periods (“cadaver preservation” in Figure 4C).

6. Context Dependence of Classification

It is important to clearly define the context in which one is classifying parasitic decomposers: models built from an inappropriate context could lead to misleading predictions. For example, Coccidioides sp., the causative agent of coccidiomycosis, has long been treated as an opportunistic sapronotic agent that proliferates in arid soils and only infects mammals facultatively (Nguyen et al. 2013; Taylor and Barker 2019). In this disease model, coccidiomycosis can be predicted by monitoring abiotic parameters such as soil moisture and consistency. However, evidence is emerging that this fungus obligately infects and kills small mammals and only proliferates in soils enriched with rodent cadavers, and that the epidemiology of coccidiomycosis most closely tracks small rodent population dynamics (del Rocío Reyes‐Montes et al. 2016; Taylor and Barker 2019). From an anthropocentric perspective, Coccidioides sp. fits the definition of an opportunistic saprotrophic agent no matter which of these hypotheses is true: human infection has no influence on its fitness, while the saprotrophic cycle does. From an ecological perspective, however, the population dynamics of Coccidioides can likely only be understood in the context of its rodent‐host life cycle, where it is best considered a saprotrophic parasitoid.

7. Evolution of Parasitic Decomposers

The idea that many parasitic organisms evolved from decomposers arose shortly after the advent of germ theory (Hueppe 1886). This idea has proved one of the most long‐standing evolutionary hypotheses in biology (Smith 1887; Zumpt 1965), yet remains largely untested. The general logic of the hypothesis is that decomposers may accidentally become capable of parasitism via preadaptation, thus finding themselves in a selective landscape in which parasitism can contribute to fitness. From here, obligate parasitism and complex life cycles could evolve.

While rarely tested explicitly, evidence for and against this enduring hypothesis is scattered throughout the literature. Among plant parasites, evolutionary transitions between necrotrophs (which induce necrosis and decompose necrotic tissue) and avirulent endophytes (parasites deriving nutrition without causing necrosis or obvious tissue damage) are common and reversible; transitions from either of these strategies to biotrophy (virulent parasitism), however, appear to be irreversible (Delaye et al. 2013). In the Chytridiomycota, saprotrophy seems to have independently evolved several times from a parasitic common ancestor (Thome et al. 2024). However, it is unclear whether that parasitic common ancestor itself may have arisen from a saprotroph. In myiatic flies, transitions between saprotrophy and parasitism seem common (Stevens and Wallman 2006). For example, all known parasitic or parasaprotrophic species of calliphorid flies have at least one closely related species that is saprotrophic (Stevens et al. 2006). Whether saprotrophy is a general preadaptation for parasitism remains an outstanding question.

The general model describing parasitic decomposer life history strategies (see above) offers some insight into possible evolutionary routes between strategies. If obligate saprotrophs maintain some chance of becoming opportunistic parasites via preadaptation, then we might expect some proportion of saprotrophs to become opportunistic sapronotic agents. If, over time, some of those opportunistic sapronotic agents gained the ability to transmit from living hosts back to their non‐living organic substrate (), this would mark an evolutionary transition to adapted sapronosis. Alternatively, saprotrophic parasitoids may have arisen from opportunistic sapronotic agents that gained the ability to “convert” live host bodies into useful substrates for decomposition () while losing the ability to transmit from cadaver to cadaver (). If an adapted sapronotic agent were to gain the ability to transmit from host‐to‐host (), this could permit a transition to parasaprotrophy.

8. Outstanding Questions

Despite having been noted and remarked upon for nearly 140 years, the ecological, evolutionary, and physiological links between parasitism and saprotrophy remain largely unexplored. Outstanding questions abound. We mentioned several such questions in the sections above. Here, we point out a handful of other pressing concerns.

Perhaps the most basic unanswered issue concerning parasitic decomposers is the question of what ecological and evolutionary factors permit the maintenance of a particular life history strategy. What circumstances prevent parasaprotrophs, for example, from evolving towards pure parasitism or pure saprotrophy? Related to this is the question of how frequently populations transition between life history strategies, and the role that such transitions play in speciation. Our general evolutionary model points towards plausible trade‐offs and ecological conditions underpinning both stability and transitions, each of which stands to be tested empirically.

A major step towards such empirical exploration would be the identification of physiological and genetic mechanisms driving parasitism‐decomposition trade‐offs, and the extent to which parasitic and saprotrophic ability are plastic within species. Such information would not only aid our understanding of how selection operates on this spectrum, but could also give us valuable insight into the ways by which saprotrophs become infectious. Given the large proportion of human pathogens that are parasitic decomposers (Kuris et al. 2014), understanding this relationship could light the path towards improved medical treatments or interventions.

Similarly, the effectiveness of epidemiological interventions targeting the decomposer stage of the life cycle of problematic pathogens is an under‐explored area of research. Interventions targeting non‐human hosts of human pathogens with complex life cycles have sometimes had promising results (Hopkins et al. 2022; Sokolow et al. 2015). Identifying such interventions for parasitic decomposers may have similar benefits, especially as sources of decomposition are not universally kept separate from at‐risk people, livestock, or crops (see refs in Curtis 2011).

Establishing a model system for the study of parasitic decomposers would greatly aid in closing these knowledge gaps. An ideal system would be easy to maintain in a laboratory setting. Host, parasite, and decomposition substrate should all be conducive to genetic control; all would ideally be clonal. Rapid generation time in the parasitic decomposer would facilitate experiment design and data collection, as would a straightforward ability to measure epidemiological parameters (e.g., fitness). The ideal experimental parasitic decomposer would have different aspects of its life cycle amenable to experimental manipulation and have the ability to at least simulate all four life history strategies. Sadly, such an ideal system does not yet exist. Crop pests such as the “Rhizoctonia” fungi and Fusarium are so far the most established candidates for such study. These, however, suffer from long generation times and the frequent occurrence of heterokaryosis, which complicates models of evolution that rely on strict inheritance (Buxton 1956; Parmeter 1970). Regardless, finding a model system approaching at least some of these ideal features would greatly enhance our ability to explore the biology of parasitic decomposers.

9. Conclusion

Parasitic decomposers are diverse, both in the taxa they comprise and the life history strategies encompassed by the term. Far from being simple “facultative” parasites that only find themselves infecting live hosts by happenstance, many parasitic decomposers are finely adapted to complex life cycles involving both living and dead substrates. Some of the most devastating human, livestock, wildlife, crop, and forest diseases are caused by parasitic decomposers.

In our synthesis of this underappreciated group of organisms, we endeavoured to apply a taxon‐agnostic approach to the existing knowledge. In doing so, we found four distinct life history strategies that apply to organisms across the tree of life, from bacteria to myiatic flies. The ability of parasites to act as decomposers, and decomposers to act as parasites, is a strategy that has arisen time and again. These are not merely conglomerations of well‐known strategies like pure parasitism or pure saprotrophy, but represent unique ecological niches and epidemiological situations. As new pathogens continuously emerge, perhaps it is wise to monitor sapronoses and parasaprotrophs as closely as we do zoonoses.

Author Contributions

Daniel C.G. Metz and Clayton E. Cressler conceived the synthesis, and together with Kelly L. Weinersmith designed the literature search. All authors conducted the search. Daniel C.G. Metz and Clayton E. Cressler produced code and performed theoretical analysis. Daniel C.G. Metz produced the initial manuscript and drafted all figures. All authors provided editorial input and approved the final submitted manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Peer Review

The peer review history for this article is available at https://www.webofscience.com/api/gateway/wos/peer‐review/10.1111/ele.70135.

Supporting information

Data S1.

Metz, D. C. G. , Weinersmith K. L., Beagle A. S., Dixit R. M., Fragel C. G., and Cressler C. E.. 2025. “Deadly Decomposers: Distinguishing Life History Strategies on the Parasitism‐Saprotrophy Spectrum.” Ecology Letters 28, no. 6: e70135. 10.1111/ele..

Editor: Jonathan M. Chase

Data Availability Statement

Mathematica code for calculation and analysis and R code for figures are available in the FigShare Digital Repository (DOI: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28710770). No new data were analysed or created in this study.

References

- Abang, M. M. , Baum M., Ceccarelli S., et al. 2006. “Differential Selection on Rhynchosporium Secalis During Parasitic and Saprophytic Phases in the Barley Scald Disease Cycle.” Phytopathology 96: 1214–1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahuatzin‐Flores, O. E. , Torres E., and Chávez‐Bravo E.. 2024. “ Acinetobacter baumannii , A Multidrug‐Resistant Opportunistic Pathogen in New Habitats: A Systematic Review.” Microorganisms 12: 644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akinsanmi, O. A. , Chakraborty S., Backhouse D., and Simpfendorfer S.. 2007. “Passage Through Alternative Hosts Changes the Fitness of Fusarium Graminearum and Fusarium Pseudograminearum.” Environmental Microbiology 9: 512–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almagro‐Moreno, S. , and Taylor R. K.. 2013. “Cholera: Environmental Reservoirs and Impact on Disease Transmission.” Microbiology Spectrum 1. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen, S. B. , Gerritsma S., Yusah K. M., et al. 2009. “The Life of a Dead Ant: The Expression of an Adaptive Extended Phenotype.” American Naturalist 174: 424–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bail, O. 1911. Das Problem Der Bakteriellen Infektion. W. Klinkhardt. [Google Scholar]

- Belov, A. , and Kulikalova E.. 2016. “Sapronoses: Ecology of Infection Agents, Epidemiology, Terminology and Classification.” Epidemiology and Vaccinal Prevention 1: 5–17. [Google Scholar]

- Belov, A. B. 2017. “Controversial Issues of Sapronoses and Possible Solutions.” Fundamental and Clinical Medicine 2: 34–44. [Google Scholar]

- Belov, A. B. , and Kirov S. M.. 2018. “Innovative Approach to Solving Theoretical Issues of the Ecological and Epidemiological Concept of Sapronoses.” Epidemiology and Vaccinal Prevention 17: 87–94. [Google Scholar]

- Belov, A. B. , and Kuzin A. A.. 2017. “Health Care‐Associated Sapronous Infections: Problematic Questions of Epidemiological Theory.” Permsk. Meditsinskiy Zhurnal 34: 94–102. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, R. , Hutmacher R., and Davis R.. 2008. “Seed Transmission of Fusarium Oxysporum f. sp. Vasinfectum Race 4 in California.”

- Beyer, W. , and Turnbull P. C. B.. 2009. “Anthrax in Animals.” Molecular Aspects of Medicine 30: 481–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boddy, L. , and Hiscox J.. 2016. “Fungal Ecology: Principles and Mechanisms of Colonization and Competition by Saprotrophic Fungi.” Microbiology Spectrum 4. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brännström, Å. , Johansson J., and Von Festenberg N.. 2013. “The Hitchhiker's Guide to Adaptive Dynamics.” Games 4: 304–328. [Google Scholar]

- Brusina, E. 2015. “Epidemiology of Healthcare‐Associated Infections, Caused by Sapronosis‐Group Pathogens.” Epidemiology and Vaccine‐Preventable Diseases 14: 50–56. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, F. C. 1953. “Saprophytic Behaviour of Some Cereal Root‐Rot Fungi.” Annals of Applied Biology 40: 284–297. [Google Scholar]

- Buxton, E. W. 1956. “Heterokaryosis and Parasexual Recombination in Pathogenic Strains of Fusarium Oxysporum .” Microbiology 15: 133–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, L. J. , Burger J., Zappalorti R. T., et al. 2021. “Soil Reservoir Dynamics of Ophidiomyces Ophidiicola, the Causative Agent of Snake Fungal Disease.” Journal of Fungi 7: 461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerenius, L. , and Söderhäll K.. 1985. “Repeated Zoospore Emergence as a Possible Adaptation to Parasitism in Aphanomyces.” Experimental Mycology 9: 9–63. [Google Scholar]

- Choe, S. , Lee D., Park H., et al. 2016. “Canine Wound Myiasis Caused by Lucilia Sericata (Diptera: Calliphoridae) in Korea.” Korean Journal of Parasitology 54: 667–671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colwell, R. R. , Kaper J., and Joseph S.. 1977. “ Vibrio cholerae , Vibrio Parahaemolyticus, and Other Vibrios: Occurrence and Distribution in Chesapeake Bay.” Science 198: 394–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cressler, C. E. , McLEOD D. V., Rozins C., Hoogen J. V. D., and Day T.. 2016. “The Adaptive Evolution of Virulence: A Review of Theoretical Predictions and Empirical Tests.” Parasitology 143: 915–930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis, V. 2011. “Why Disgust Matters.” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, B: Biological Sciences 366: 3478–3490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniel, M. , Šrámová H., and Zalabska E.. 1994. “Lucilia Sericata (Diptera: Calliphoridae) Causing Hospital‐Acquired Myiasis of a Traumatic Wound.” Journal of Hospital Infection 28: 149–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniels, J. 1963. “Saprophytic and Parasitic Activities of Some Isolates of Corticium Solani.” Transactions of the British Mycological Society 46: 485. [Google Scholar]

- de Bary, A. 1887. Comparative Morphology and Biology of the Fungi, Mycetozoa and Bacteria. Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- del Rocío Reyes‐Montes, M. , Pérez‐Huitrón M. A., Ocaña‐Monroy J. L., et al. 2016. “The Habitat of Coccidioides spp. and the Role of Animals as Reservoirs and Disseminators in Nature.” BMC Infectious Diseases 16: 550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaye, L. , García‐Guzmán G., and Heil M.. 2013. “Endophytes Versus Biotrophic and Necrotrophic Pathogens—Are Fungal Lifestyles Evolutionarily Stable Traits?” Fungal Diversity 60: 125–135. [Google Scholar]

- Denning, D. W. , Park S., Lass‐Florl C., et al. 2011. “High‐Frequency Triazole Resistance Found in Nonculturable Aspergillus fumigatus From Lungs of Patients With Chronic Fungal Disease.” Clinical Infectious Diseases 52: 1123–1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diekmann, O. , and Heesterbeek J. A. P.. 2000. Mathematical Epidemiology of Infectious Diseases: Model Building, Analysis and Interpretation. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Diekmann, O. , Heesterbeek J. A. P., and Metz J. A. J.. 1990. “On the Definition and the Computation of the Basic Reproduction Ratio R0 in Models for Infectious Diseases in Heterogeneous Populations.” Journal of Mathematical Biology 28: 365–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodds, K. J. , Sweeney J., and Allison J. D.. 2023. “Woodborers in Forest Stands.” In Forest Entomology and Pathology: Volume 1: Entomology, 361–415. Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Domaradskiĭ, I. V. 1988. “Is the Term “Sapronoses” Needed?” Zhurnal Mikrobiologii, Epidemiologii i Immunobiologii 12: 117–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dragon, D. C. , and Rennie R. P.. 1995. “The Ecology of Anthrax Spores: Tough but Not Invincible.” Canadian Veterinary Journal 36: 295–301. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elya, C. , and De Fine Licht H. H.. 2021. “The Genus Entomophthora: Bringing the Insect Destroyers Into the Twenty‐First Century.” IMA Fungus 12: 34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erken, M. , Lutz C., and McDougald D.. 2015. “Interactions of Vibrio spp. With Zooplankton.” Microbiology Spectrum 3. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faruque, S. M. , Albert M. J., and Mekalanos J. J.. 1998. “Epidemiology, Genetics, and Ecology of Toxigenic Vibrio cholerae .” Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews 62: 1301–1314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiore‐Donno, A. M. , and Bonkowski M.. 2021. “Different Community Compositions Between Obligate and Facultative Oomycete Plant Parasites in a Landscape‐Scale Metabarcoding Survey.” Biology and Fertility of Soils 57: 245–256. [Google Scholar]

- Frenken, T. , Alacid E., Berger S. A., et al. 2017. “Integrating Chytrid Fungal Parasites Into Plankton Ecology: Research Gaps and Needs.” Environmental Microbiology 19: 3802–3822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godfray, H. C. J. , Briggs C. J., Barlow N. D., O’Callaghan M., Glare T. R., and Jackson T. A.. 1999. “A Model of Insect—Pathogen Dynamics in Which a Pathogenic Bacterium can also Reproduce Saprophytically.” Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences 266, no. 1416: 233–240. 10.1098/rspb.1999.0627. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon, T. R. 2017. “ Fusarium oxysporum and the Fusarium Wilt Syndrome.” Annual Review of Phytopathology 55: 23–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon, T. R. , and Okamoto D.. 1990. “Colonization of Crop Residue by Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. Melonis and Other Species of Fusarium .” Phytopathology 80: 381–386. [Google Scholar]

- Grimont, F. , and Grimont P. A.. 1992. “The Genus Serratia .” In The Prokaryotes: A Handbook on the Biology of Bacteria, edited by Balows A., Truper H. G., Dworkin M., Harder W., and Schleifer K.‐H., 2822–2848. Springer‐Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, M. 1997. “Traumatic Myiasis of Sheep in Europe: A Review.” Parassitologia 39: 409–413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris, A. D. , Johnson J. K., Pineles L., O'Hara L. M., Bonomo R. A., and Thom K. A.. 2019. “Patient‐To‐Patient Transmission of Acinetobacter baumannii Gastrointestinal Colonization in the Intensive Care Unit.” Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 63: e00392‐19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heal, O. W. , and MacLean S. F.. 1975. “Comparative Productivity in Ecosystems—Secondary Productivity.” In Unifying Concepts in Ecology: Report of the Plenary Sessions of the First International Congress of Ecology, the Hague, the Netherlands, September 8–14, 1974, edited by van Dobben W. H. and Lowe‐McConnell R. H., 89–108. Springer Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- Hejazi, A. , and Falkiner F. R.. 1997. “ Serratia marcescens .” Journal of Medical Microbiology 46: 903–912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrix, F. , and Campbell W.. 1973. “Pythiums as Plant Pathogens.” Annual Review of Phytopathology 11: 77–98. [Google Scholar]

- Herms, D. A. , and McCullough D. G.. 2014. “Emerald Ash Borer Invasion of North America: History, Biology, Ecology, Impacts, and Management.” Annual Review of Entomology 59: 13–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins, S. R. , Lafferty K. D., Wood C. L., et al. 2022. “Evidence Gaps and Diversity Among Potential Win–Win Solutions for Conservation and Human Infectious Disease Control.” Lancet Planetary Health 6: e694–e705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyt, J. R. , Kilpatrick A. M., and Langwig K. E.. 2021. “Ecology and Impacts of White‐Nose Syndrome on Bats.” Nature Reviews. Microbiology 19: 196–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hueppe, F. 1886. The Methods of Bacteriological Investigation. D. Appleton and comapny. [Google Scholar]

- Huq, A. , Small E. B., West P. A., Huq M. I., Rahman R., and Colwell R. R.. 1983. “Ecological Relationships Between Vibrio Cholerae and Planktonic Crustacean Copepods.” Applied and Environmental Microbiology 45: 275–283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffee, B. A. , and Zehr E. I.. 1985. “Parasitic and Saprophytic Abilities of the Nematode‐Attacking Fungus Hirsutella Rhossiliensis.” Journal of Nematology 17: 341–345. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaczmarczyk, D. , Kopczynski J., Kwiecien J., Michalski M., and Kurnatowski P.. 2011. “The Human Aural Myiasis Caused by Lucilia Sericata.” Wiadomości Parazytologiczne 57: 27–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kedves, O. , Shahab D., Champramary S., et al. 2021. “Epidemiology, Biotic Interactions and Biological Control of Armillarioids in the Northern Hemisphere.” Pathogens 10: 76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, M. , Pasmans F., Muñoz J. F., et al. 2021. “Diversity, Multifaceted Evolution, and Facultative Saprotrophism in the European Batrachochytrium Salamandrivorans Epidemic.” Nature Communications 12: 6688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer, S. , Dibbern D., Moll J., et al. 2016. “Resource Partitioning Between Bacteria, Fungi, and Protists in the Detritusphere of an Agricultural Soil.” Frontiers in Microbiology 7. 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuris, A. M. , Lafferty K. D., and Sokolow S. H.. 2014. “Sapronosis : A Distinctive Type of Infectious Agent.” Trends in Parasitology 30: 386–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacey, J. 1996. “Spore Dispersal—Its Role in Ecology and Disease: The British Contribution to Fungal Aerobiology.” Mycological Research 100: 641–660. [Google Scholar]

- Lafferty, K. D. , and Kuris A. M.. 2002. “Trophic Strategies, Animal Diversity and Body Size.” Trends in Ecology & Evolution 17: 507–513. [Google Scholar]

- Latgé, J.‐P. , and Chamilos G.. 2019. “ Aspergillus fumigatus and Aspergillosis in 2019.” Clinical Microbiology Reviews 33: e00140‐18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leake, J. R. 1994. “The Biology of Myco‐Heterotrophic (‘Saprophytic’) Plants.” New Phytologist 127: 171–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, C. A. , Holdo R. M., and Muzika R.‐M.. 2021. “Feedbacks Between Forest Structure and an Opportunistic Fungal Pathogen.” Journal of Ecology 109: 4092–4102. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, D. H. 1973. “Concepts in Fungal Nutrition and the Origin of Biotrophy.” Biological Reviews 48: 261–277. [Google Scholar]

- Litvin, V. Y. , Somov G. P., and Pushkareva V. I.. 2010. “Sapronoses as Natural Focal Diseases.” Epidemiology and Vaccinal Prevention 1: 10–16. [Google Scholar]

- Longcore, J. E. , Pessier A. P., and Nichols D. K.. 1999. “Batrachochytrium Dendrobatidis Gen. Et sp. Nov., a Chytrid Pathogenic to Amphibians.” Mycologia 91: 219–227. [Google Scholar]

- Lovett, B. , Macias A., Stajich J. E., et al. 2020. “Behavioral Betrayal: How Select Fungal Parasites Enlist Living Insects to Do Their Bidding.” PLoS Pathogens 16: e1008598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luttrell, E. 1974. “Parasitism of Fungi on Vascular Plants.” Mycologia 66: 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Lutz, C. , Erken M., Noorian P., Sun S., and McDougald D.. 2013. “Environmental Reservoirs and Mechanisms of Persistence of Vibrio cholerae .” Frontiers in Microbiology 4: 375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahlen, S. D. 2011. “Serratia Infections: From Military Experiments to Current Practice.” Clinical Microbiology Reviews 24: 755–791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin, G. W. 1932. “Systematic Position of the Slime Molds and Its Bearing on the Classification of the Fungi.” Botanical Gazette 93: 421–435. [Google Scholar]

- Mongkolsamrit, S. , Kobmoo N., Tasanathai K., et al. 2012. “Life Cycle, Host Range and Temporal Variation of Ophiocordyceps Unilateralis/Hirsutella Formicarum on Formicine Ants.” Journal of Invertebrate Pathology 111: 217–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moskaluk, A. E. , and VandeWoude S.. 2022. “Current Topics in Dermatophyte Classification and Clinical Diagnosis.” Pathogens 11: 957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullins, J. , Harvey R., and Seaton A.. 1976. “Sources and Incidence of Airborne Aspergillus fumigatus (Fres).” Clinical and Experimental Allergy 6: 209–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munoz‐Price, L. S. , Fajardo‐Aquino Y., Arheart K. L., et al. 2013. “Aerosolization of Acinetobacter baumannii in a Trauma ICU*.” Critical Care Medicine 41: 1915–1918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, C. , Barker B. M., Hoover S., et al. 2013. “Recent Advances in Our Understanding of the Environmental, Epidemiological, Immunological, and Clinical Dimensions of Coccidioidomycosis.” Clinical Microbiology Reviews 26: 505–525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norros, V. , Halme P., Norberg A., and Ovaskainen O.. 2023. “Spore Production Monitoring Reveals Contrasting Seasonal Strategies and a Trade‐Off Between Spore Size and Number in Wood‐Inhabiting Fungi.” Functional Ecology 37: 551–563. [Google Scholar]

- Olson, Å. , Aerts A., Asiegbu F., et al. 2012. “Insight Into Trade‐Off Between Wood Decay and Parasitism From the Genome of a Fungal Forest Pathogen.” New Phytologist 194: 1001–1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey, A. , Mideo N., and Platt T. G.. 2022. “Virulence Evolution of Pathogens That Can Grow in Reservoir Environments.” American Naturalist 199: 141–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parmeter, J. R. 1970. Rhizoctonia Solani: Biology and Pathology. University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pastrana, A. , Watson D., and Gordon T.. 2019. “Transmission of Fusarium Oxysporum f. sp. Fragariae Through Stolons in Strawberry Plants.” Plant Disease 103: 1249–1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrovskaia, V. G. 1990. “Is the Term “Sapronoses” Needed?” Zhurnal Mikrobiologii, Epidemiologii i Immunobiologii 12: 111–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pushkareva, V. I. , Ermolaeva S. A., and Litvin V. Y.. 2010. “Hydrobionts as Reservoir Hosts for Infectious Agents of Bacterial Sapronoses.” Zoologicheskiĭ Zhurnal 1: 37–47. [Google Scholar]

- Rajarammohan, S. 2021. “Redefining Plant‐Necrotroph Interactions: The Thin Line Between Hemibiotrophs and Necrotrophs.” Frontiers in Microbiology 12. 10.3389/fmicb.2021.673518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds, H. T. , Ingersoll T., and Barton H. A.. 2015. “Modeling the Environmental Growth of Pseudogymnoascus Destructans and Its Impact on the White‐Nose Syndrome Epidemic.” Journal of Wildlife Diseases 51: 318–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice, M. A. 1935. “The Cytology of Host‐Parasite Relations.” Botanical Review 1: 327–354. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, H. E. , Steinkraus D. C., Eilenberg J., Hajek A. E., and Pell J. K.. 2006. “Bizarre Interactions and Endgames: Entomopathogenic Fungi and Their Arthropod Hosts.” Annual Review of Entomology 51: 331–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samson, R. A. , Evans H. C., and Latgé J.‐P.. 2013. Atlas of Entomopathogenic Fungi. Springer Science & Business Media. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, T. 1887. “Parasitic Bacteria and Their Relation to Saprophytes.” American Naturalist 21: 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Sokolow, S. H. , Huttinger E., Jouanard N., Hsieh M. H., and Lafferty K. D.. 2015. “Reduced Transmission of Human Schistosomiasis After Restoration of a Native River Prawn That Preys on the Snail Intermediate Host.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 112: 9650–9655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon, P. S. , Tan K.‐C., and Oliver R. P.. 2003. “The Nutrient Supply of Pathogenic Fungi; a Fertile Field for Study.” Molecular Plant Pathology 4: 203–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spellberg, B. , and Bonomo R. A.. 2013. ““Airborne Assault”: A New Dimension in Acinetobacter baumannii Transmission.” Critical Care Medicine 41: 2042–2044. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31829136c3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens, J. R. , and Wallman J. F.. 2006. “The Evolution of Myiasis in Humans and Other Animals in the Old and New Worlds (Part I): Phylogenetic Analyses.” Trends in Parasitology 22: 129–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens, J. R. , Wallman J. F., Otranto D., Wall R., and Pape T.. 2006. “The Evolution of Myiasis in Humans and Other Animals in the Old and New Worlds (Part II): Biological and Life‐History Studies.” Trends in Parasitology 22: 181–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki, S. U. , and Sasaki A.. 2019. “Ecological and Evolutionary Stabilities of Biotrophism, Necrotrophism, and Saprotrophism.” American Naturalist 194: 90–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]