ABSTRACT

The inoculation of microbes into soil environments has numerous applications for improving soil quality and crop health; however, the ability of exogenous and engineered microbes to survive and spread in soil remains uncertain. To address this challenge, we assayed the survival and spread of Mycobacterium smegmatis, engineered with either plasmid transformation or genome integration, as well as its mycobacteriophage Kampy, in both sterilized and non-sterilized soil microcosms over a period of 49 days. Although engineered M. smegmatis and Kampy persisted in all soil microcosms, there was minimal evidence of spread to 5 cm away from the inoculation site. There was a higher prevalence of Kampy observed in sterilized soil than in non-sterilized soil, suggesting a detrimental effect of the native soil biotic and viral community on the ability of this phage to proliferate in the soil microcosm. Additionally, a higher abundance of the genome-integrated bacteria relative to the plasmid-carrying bacteria, as well as evidence for loss of plasmid over the duration of the experiment, suggests a burden associated with bacteria harboring plasmids, although plasmids were still retained across 49 days. To our knowledge, this is the first study to simultaneously measure the persistence and spread of bacteria and their associated phage in both sterilized and non-sterilized soil microcosms, employing bacteria with plasmid-based and genome-integrated engineered circuits. As such, this study provides a novel understanding of challenges associated with the deployment of bioengineered microbes into soil environments.

IMPORTANCE

Healthy soil is essential to sustain life, as it provides habitable land, enables food production, promotes biodiversity, sequesters and cycles nutrients, and filters water. Given the prevalence of soil degradation, treatment of soil with microbes that promote soil and crop health could improve global soil sustainability; furthermore, the application of bioengineering and synthetic biology to these microbes allows fine-tunable and robust control of gene-of-interest expression. These solutions require the introduction of bacteria into the soil, an environment in which abundant competition and often limited nutrients can result in bacterial death or dormancy. This study employs Mycobacterium smegmatis as a chassis alongside its bacteriophage Kampy in soil microcosms to assess the ability of non-native microbes to survive and spread in soil. Insights from this experiment highlight important challenges, which must be overcome for successful deployment of engineered microbes in the field.

KEYWORDS: soil, microcosm, phage, Mycobacterium smegmatis, synthetic biology

INTRODUCTION

Soil health is at risk globally (1, 2), threatening biodiversity (3), nutrient cycling (4), and food production (5). Scientists have recently issued an urgent call to action for the utilization of microbes to address escalating climate change (6) due to their constantly evolving capabilities to catabolize pollutants (7, 8), sequester greenhouse gasses (9, 10), restore degraded soils and prevent erosion (11, 12), and promote crop growth (13, 14). Bioengineering enables the finely tunable expression of genes capable of performing such actions in organisms adapted for growth in diverse environments (15); these genetic circuits have already demonstrated the potential to remediate soil environments (16, 17). However, these engineered microbes are often studied exclusively in model species grown under optimal laboratory conditions, using nutrient-rich media and with protection from adversaries—conditions that promote exponential growth and bountiful protein production (18, 19) and differ greatly from those of the soil in which the microbes must perform once deployed. In soil environments, unlike under typical laboratory conditions, bacteria can face variable temperature (20, 21) and pH (22, 23), scarce nutrients (24, 25), as well as competitors, predators, and symbionts (26–28). These harsh conditions typically promote dormancy; it is estimated that only 2% of bacteria in the soil are non-dormant (29). For engineered cells inoculated into the soil, genetic circuits can impact fitness, either positively such as by conferring antibiotic resistance (30, 31), or negatively such as by imposing a burden on their chassis (32–34).

Furthermore, in natural environments, continual interactions with bacteriophage (phage) drive alterations in bacterial population dynamics, underlying the importance of examining both populations concurrently in soil. Bacterial relative fitness in communities with inoculated phage has been found to be significantly lower in natural environments, including soil microcosms, compared with high-nutrient broths (35, 36). Additionally, phage presence in soil has been correlated with changes in bacterial diversity (37) as well as nutrient contents key for healthy soils (37–40). Due to the profound effect of the soil virome on soil health and the soil microbiome, several recent reviews and opinion articles have suggested that phages can be utilized to improve soil and crop health (41–44).

Although some studies have evaluated microbial survival and growth dynamics in soil, the results from these studies have been inconsistent, likely due to differences in experimental design such as bacteria type, soil conditions, and presence of inoculated phage. For example, in the absence of added phage, bacteria inoculated into sterilized soil have been shown both to increase overall in abundance (45, 46) and spread (45, 47) as well as to decrease overall in abundance (45, 46, 48). However, when bacteria are co-inoculated with phage in sterilized soil, bacteria populations tend to decrease in abundance on average (35, 49, 50). Alternatively, bacteria inoculated into non-sterilized soil have generally been shown to decrease in abundance overall, whether in the presence of co-inoculated phage (35, 50–53) or not (46, 48, 53–58). Despite this observed decline of exogenous bacterial abundance in non-sterilized soil, bacteria have still been measured spreading vertically through non-sterilized soil columns (53, 59, 60), with phage presence impeding migration (53). There is a clear need for research that systematically compares multiple key variables in order to provide a more unified perspective on microbial persistence and spread in soil environments.

To our knowledge, no single study to date has simultaneously analyzed the population dynamics of both engineered bacteria and their associated phage in soil microcosms while also comparing two major conditions that reveal essential information about the feasibility of soil synthetic biology: soil type (sterilized versus non-sterilized) and the method of genetically engineering the bacteria (plasmid-transformed versus genome-integrated). This study addresses this gap in the literature by assessing the persistence and spread of Kampy phage and its host Mycobacterium smegmatis—engineered to produce red fluorescence through either plasmid transformation or genome integration—when co-inoculated into soil microcosms. The findings offer critical insights into the challenges and limitations of deploying engineered bacteria for soil remediation, particularly in understanding microbial persistence, spread, and interactions with native biotic communities, and will inform future applications in sustainable agriculture and environmental restoration.

RESULTS

Experimental overview

Our study tested the persistence and spread to 5 cm of M. smegmatis engineered with mCherry and its mycobacteriophage Kampy (“Kampy”) in soil microcosms over 49 days and across two comparisons: sterilized versus non-sterilized soil and plasmid-based (Ms-pC3) versus genome-integrated (Ms-pML(int)) M. smegmatis engineered strains (Fig. 1). In brief, triplicate soil microcosms were inoculated with Kampy and either Ms-pC3 or Ms-pML(int); half of the microcosms were sterilized prior to inoculation, whereas the rest were left non-sterilized. Additional sterilized and non-sterilized soil microcosms with only PBS added were used as controls. Each was sampled at the inoculation site and at 5 cm away from the inoculation site for six time points across 49 days. Soil samples were plated for bacteria and phage to assay M. smegmatis and Kampy absolute abundance, respectively, and also used to identify the percentage of pink Ms-pC3 colonies over time to provide insight into plasmid retention. Additionally, DNA was extracted from soil samples for 16S rRNA and shotgun metagenomic sequencing to assay M. smegmatis relative abundance, as well as to perform a principal component analysis (PCA) on broader microbial community structure over time after inoculation (Fig. 1). P values were computed through two-way and three-way repeated measures ANOVA, with P < 0.05 indicating significance and P < 0.10 indicating a trend.

Fig 1.

Experimental design for microcosms. A total of 18 microcosms were constructed: nine sterilized and nine non-sterilized. For each sterility type, there were three replicate control microcosms with only PBS added, three microcosms with Ms-pC3 and Kampy added, and three microcosms with Ms-pML(int) and Kampy added. Microcosms were sampled six times over a 49-day period, each time at the inoculation site and 5 cm away from the inoculation site. Each sample was plated for bacteria and phage and had DNA extracted for 16s rRNA and shotgun metagenomic sequencing.

Engineered M. smegmatis persisted in both sterilized and non-sterilized soil microcosms over 7 weeks

In order to assess the persistence of engineered M. smegmatis co-inoculated with its associated mycobacteriophage Kampy in soil over 49 days, Ms-pC3 and Ms-pML(int) absolute abundances at the inoculation site of sterilized and non-sterilized soil microcosms were measured using colony counts, whereas their relative abundances in non-sterilized microcosms were assayed using 16S rRNA analysis and shotgun metagenomic analysis. M. smegmatis abundances in these microcosms were measured at six time points over 7 weeks and across two comparisons: soil sterilization (sterilized versus non-sterilized) and method of strain engineering (plasmid-transformed versus genome-integrated).

Overall, all three assays (colony counts, 16S rRNA, and shotgun metagenomic analysis) suggest M. smegmatis abundance decreases over time yet remains detectable in soil at levels significantly different from control microcosms (with no inoculation) even after 49 days. The colony counting assay showed that, across both soil types and engineered strains, M. smegmatis’s absolute abundance changed significantly over time (P = 0.007), decreasing 3.6-fold in sterilized soil and 38-fold in non-sterilized soil on average by day 49 (relative to day 4) (Fig. 2A; Table S1). This corresponded to an average final absolute abundance of approximately 107 CFU/g of sterilized soil and 106 CFU/g of non-sterilized soil. 16S rRNA analysis similarly showed significant changes in M. smegmatis relative abundance in non-sterilized microcosms over time (P = 0.033), with the relative abundance decreasing 1.6-fold by day 49 (relative to day 4) to 0.578% on average (Fig. 2B; Table S2). Likewise, the shotgun metagenomic analysis showed an apparent decrease in the relative abundance of both M. smegmatis-engineered strains between days 7 and 49, although this change was not statistically significant (P = 0.16).

Fig 2.

M. smegmatis persistence at the inoculation site over 49 days. (A) M. smegmatis CFU/g dry soil was determined by colony counting in both sterilized (left) and non-sterilized (right) soil. M. smegmatis counts in control microcosms are shown in black, Ms-pC3 in blue, and Ms-pML(int) in red. Lines depict the average of 3 biological replicates, with each replicate displayed as an individual point. (B) M. smegmatis 16S rRNA relative abundance (as a percentage) in non-sterilized soil. M. smegmatis relative abundance in control microcosms is shown in black, Ms-pC3 in blue, and Ms-pML(int) in red. Lines depict the average of three biological replicates, with each replicate displayed as an individual point. (C) M. smegmatis shotgun metagenomic relative abundance (as a percentage) in non-sterilized soil on days 7 and 49. White circles show the mean of three biological replicates, with each replicate displayed as a blue (Ms-pC3) or red (Ms-pML(int)) point.

Despite the observed differences in M. smegmatis’s final absolute abundance between sterilized and non-sterilized soil, there was limited evidence for a statistically significant effect of soil sterilization on M. smegmatis abundances over time. The colony count assay revealed there were no statistically significant differences in absolute abundances at the inoculation site between sterilized versus non-sterilized soil microcosms (P = 0.26). However, when performing separate two-way repeated measures ANOVAs on the sterilized and non-sterilized count data, only the non-sterilized soil microcosms demonstrated a statistically significant change in absolute abundance over time (P < 0.001). This significance in non-sterilized soil is in line with the aforementioned 16S rRNA results.

Additionally, the three assays suggest there was an effect due to the strain engineering method on M. smegmatis abundance. For the colony count assay, there was a trend of colony counts differing between microcosms inoculated with Ms-pC3 and Ms-pML(int) (P = 0.089), with Ms-pML(int) absolute abundance typically being higher. Separate two-way repeated measures ANOVAs on absolute abundances measured from microcosms inoculated with either Ms-pC3 or Ms-pML(int) revealed that Ms-pML(int) counts had a trend of changing over time (P = 0.059), whereas Ms-pC3 counts did not significantly change over time (P = 0.27). Furthermore, when comparing both engineered strains but considering only counts from non-sterilized microcosms, there was a statistically significant difference between Ms-pC3 counts and Ms-pML(int) counts (P = 0.025), with Ms-pML(int) populations generally more abundant. We performed a permutation analysis on these data as another means of testing statistical significance: when Ms-pC3 absolute abundances from one replicate of the non-sterilized soil colony count data were swapped with those of a replicate from Ms-pML(int), eight of the nine possible permutations were not statistically significant (Table S8), consistent with the result of a difference between plasmid-transformed and genome-integrated bacterial absolute abundances. In support of colony count data, the 16S rRNA results demonstrated a significant effect of engineered strain on M. smegmatis relative abundance in non-sterilized soil samples (P = 0.043), with Ms-pML(int) relative abundances higher on average. Permutational analysis found that none of the nine possible permutations demonstrated statistical significance (Table S8), supporting the finding that the Ms-pC3 engineered strain affects the abundance of M. smegmatis in non-sterilized soil. Conversely, shotgun metagenomic analysis, which considered only days 7 and 49, showed no significant effect of engineered strain on M. smegmatis relative abundance in non-sterilized microcosms (P = 0.28).

Limited evidence for horizontal spread of inoculated M. smegmatis to 5 cm over 7 weeks in soil microcosms

Spread of engineered M. smegmatis to 5 cm away from the inoculation site in sterilized and non-sterilized soil microcosms over 49 days was assessed by measuring Ms-pC3 and Ms-pML(int) absolute and relative abundances using colony counts and 16S rRNA analysis, respectively. All microcosms were co-inoculated with the mycobacteriophage Kampy. Colony counts showed no significant differences in M. smegmatis absolute abundance at 5 cm away from the inoculation site between microcosms inoculated with M. smegmatis and the control microcosms with no inoculation for both sterilized (P = 0.12) and non-sterilized (P = 0.72) soil (Fig. 3A; Table S3). This indicates no apparent increase in M. smegmatis colony counts at 5 cm over time as a result of the spread of our inoculated bacteria. However, 16S rRNA analysis did show statistically significant differences in M. smegmatis relative abundance between non-sterilized treatments and controls at 5 cm from the inoculation site (P = 0.015), with significant changes in M. smegmatis relative abundance over time (P = 0.041) (Fig. 3B; Table S4). This suggests that inoculation of M. smegmatis and Kampy into soil alters the relative abundance of M. smegmatis at 5 cm from the inoculation site over time, a possible indicator of spread. Additionally, the strain engineering method revealed no significant effect on the relative abundance of M. smegmatis at 5 cm from the inoculation site (P = 0.54).

Fig 3.

M. smegmatis abundance at 5 cm away from the inoculation site. (A) M. smegmatis CFU/g dry soil at 5 cm from the inoculation site as measured by colony counting. M. smegmatis counts in control microcosms are shown in black, Ms-pC3 in blue, and Ms-pML(int) in red. Lines depict the average of three biological replicates, with each replicate displayed as an individual point. (B) M. smegmatis 16S rRNA relative abundances (as a percentage) in non-sterilized soil microcosms at 5 cm from the inoculation site. M. smegmatis relative abundances in control microcosms are shown in black, Ms-pC3 in blue, and Ms-pML(int) in red. Lines depict the average of three biological replicates, with each replicate displayed as an individual point.

Inoculated mycobacteriophage Kampy persisted in soil microcosms over 7 weeks, with levels 105-fold higher in sterilized soil than in non-sterilized soil

In the same sterilized and non-sterilized soil microcosms inoculated with the mycobacteriophage Kampy and either Ms-pC3 or Ms-pML(int) as detailed above, the persistence of Kampy in soil was assessed over 49 days. Kampy abundances at the inoculation site were measured using plaque counts and were compared over time and across two comparisons: soil sterilization (sterilized versus non-sterilized) and method of M. smegmatis strain engineering (plasmid-transformed versus genome-integrated). Kampy, regardless of soil sterilization or whether Ms-pC3 or Ms-pML(int) was co-inoculated, remained detectable at levels statistically significantly different from control microcosms (with no inoculation) throughout the experiment.

There was a strong effect of soil sterilization on Kampy populations over time. Plaque count assays reveal statistically significant changes in Kampy absolute abundances at the inoculation site over time only in sterilized soil microcosms (P < 0.001), where Kampy initially increased in abundance at the inoculation site for the first 28 days before stabilizing at approximately 109 PFU/g of soil, corresponding to an 11,900-fold increase in abundance from days 4 to 49. Comparatively, there was no statistically significant change in abundance over time for non-sterilized soil microcosms (P = 0.51) in which Kampy populations remained consistent at approximately 104 PFU/g across 49 days (Fig. 4A; Table S5). Accordingly, there were statistically significant differences in Kampy absolute abundances between sterilized soil and non-sterilized soil microcosms (P < 0.001). Permutation analysis of Kampy absolute abundances between sterilized and non-sterilized soil microcosms indicated that none of the nine possible permutations demonstrated significance (Table S8), supporting the result that there is an effect of soil sterilization on Kampy abundance.

Fig 4.

Kampy persistence at the inoculation site. (A) Kampy PFU/g dry soil at the inoculation site over 49 days. Kampy population density was measured by plaque counting on plates with M. smegmatis lawns. Kampy counts in control microcosms are shown in black, Kampy counts in Ms-pC3 microcosms in blue, and Kampy counts in Ms-pML(int) microcosms in red. Lines depict the average of 3 biological replicates, with each replicate displayed as an individual point. (B) The correlation between the relative abundance (as a percentage) of Kampy metagenomic shotgun sequencing reads and phage plaque counts at the inoculation site in non-sterilized soil on days 4 and 49. Soil microcosm replicates are represented by individual points, with the dotted line representing the linear correlation between the plaque assay measurement and the relative abundance of Kampy within each sample.

Additionally, there was a limited effect of the method of engineering M. smegmatis on Kampy abundances over time. Plaque counting revealed that there was a trend of differential Kampy absolute abundance between Ms-pC3 microcosms and Ms-pML(int) microcosms (P = 0.052). However, when comparing absolute abundances between engineered M. smegmatis strains but under only one soil sterility condition at a time, this trend was only reflected in sterilized soil microcosms (P = 0.058), but not non-sterilized soil microcosms (P = 0.92).

To determine whether the plaque count assay was a precise measure of Kampy persistence, metagenomic shotgun sequencing reads derived from DNA extracted from non-sterilized microcosms on days 7 and 49 were analyzed using BLASTn against the Kampy genome. Although anywhere up to 0.00025% of reads within each sample showed significant identity to Kampy ( >99% identity, >99% query length), the length and count of these reads were too ambiguous and too small to effectively quantify the presence of Kampy. This difficulty reflects ongoing challenges in the field of metagenomics, where phages are notoriously hard to detect due to understudied factors such as short read lengths, sequencing errors, assembly quality, and the complexities of phage taxonomy (61). However, PFU/g of dry soil and shotgun metagenomic relative abundance of putative Kampy reads showed a weakly positive correlation (R2 = 0.47), suggesting that the plaque assay correlates with Kampy DNA in the soil microcosms (Fig. 4B; Table S6). A perfectly linear correlation is not expected as absolute abundance and relative abundance are not always correlated in soil environments (62).

Inoculated mycobacteriophage Kampy spread horizontally to 5 cm over 7 weeks when co-inoculated with plasmid-transformed M. smegmatis in sterilized soil

To examine the spread of Kampy over 49 days alongside two M. smegmatis engineered strains and in sterilized versus non-sterilized soil, soil was sampled from the aforementioned microcosms at 5 cm away from the inoculation site, and Kampy’s absolute abundance was quantified using a direct plating plaque assay (Table S7). There was only a significant difference in Kampy abundances at 5 cm between control microcosms and inoculated microcosms in sterilized soil microcosms inoculated with Ms-pC3 (P = 0.043), but not for sterilized soil microcosms with Ms-pML(int) or non-sterilized microcosms with M. smegmatis of either engineered strain (Fig. 5). For this reason, statistical testing was performed only on counts from sterilized soil microcosms with Ms-pC3; this test showed a significant change over time in Kampy abundances at 5 cm from the inoculation site, suggesting that spread occurred specifically in Ms-pC3 sterilized microcosms (P = 0.025).

Fig 5.

Kampy PFU/g dry soil 5 cm away from the inoculation site. Kampy density was measured by plaque counting on plates with M. smegmatis lawns. Kampy counts in control microcosms are shown in black, Kampy counts in Ms-pC3 microcosms in blue, and Kampy counts in Ms-pML(int) microcosms in red. Lines depict the average of 3 biological replicates, with each replicate displayed as an individual point.

Mycobacteriophage Kampy populations at the inoculation site experienced a greater fold change in abundance than M. smegmatis populations

Patterns in bacteria and phage relationships over time were assessed by comparing the absolute abundance of M. smegmatis and Kampy within the same microcosms (Fig. S1). At the inoculation site, the ratio of the Kampy abundance fold-change from days 4 to 49 relative to the M. smegmatis abundance fold-change from days 4 to 49 is 43,100 in sterilized soil and 24.3 in non-sterilized soil. This corresponds to Kampy abundance increasing while M. smegmatis abundance decreased in sterilized soil and Kampy abundance decreasing less than M. smegmatis abundance decreased in non-sterilized soil, with this difference occurring to a much greater degree in sterilized soil.

Although still detectable in both sterilized and non-sterilized soil, the pCherry3 plasmid was progressively lost over 7 weeks

Because Ms-pC3 plates showed both pink and non-pink M. smegmatis colony colors, the percentage of pink M. smegmatis colonies over time was calculated to qualitatively investigate the loss of the plasmid. Pink colonies were assumed to have a higher copy number of pCherry3, which was corroborated by band density PCR amplifying DNA from the pCherry3 plasmid, performed on Ms-pC3 colonies from sterilized soil microcosms (Fig. 6A). The mean percentage of pink colonies decreased from days 4 to 49 in both sterilized (63% decrease) and non-sterilized (45% decrease) microcosms, suggesting the loss of plasmid over time (Fig. 6B; Table S9).

Fig 6.

Qualitative analysis of plasmid retention in Ms-pC3. (A) Gel electrophoresis on PCR amplicons from both non-pink and pink Ms-pC3 colonies, with PCR targeting the pCherry3 plasmid. The last lane is a no-template control. (B) Percentage of pink colonies over time for sterilized and non-sterilized microcosms inoculated with Ms-pC3 (plasmid-transformed). The percentage of pink colonies in sterilized soil is shown in blue, and the percentage of pink colonies in non-sterilized soil is shown in red. Lines depict the average of up to three biological replicates (replicates with no colonies were not considered), with each replicate displayed as an individual point.

Inoculation of exogenous M. smegmatis and mycobacteriophage Kampy affected soil community structure

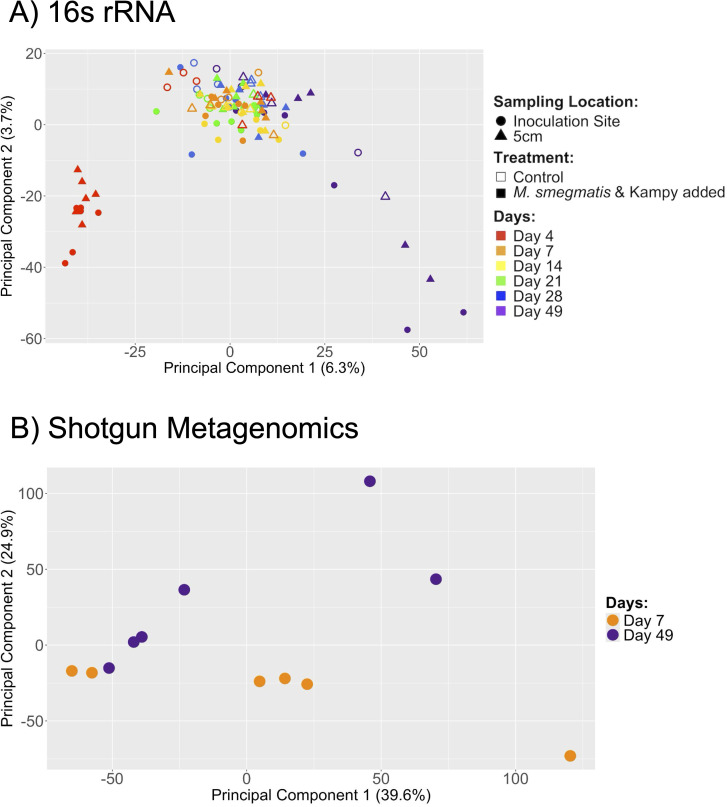

To determine if there was an effect of inoculating engineered M. smegmatis and Kampy on soil microbial community composition in non-sterilized soil microcosms, principal component analyses (PCAs) were performed on 16S rRNA relative abundances (all time points) and shotgun metagenomic relative abundances (days 7 and 49). PCAs on both assays revealed grouping of samples by time. For the 16S rRNA relative abundance PCA, the first time point (day 4) and the last time point (day 49) clustered separately from the rest of the data (Fig. 7A). Moreover, day 4 samples of microcosms inoculated with M. smegmatis and Kampy clustered separately from control microcosms with only PBS added, suggesting inoculation creates an initial disruption in bacterial community structure within the first few days. Similarly, the shotgun metagenomic PCA showed grouping of samples by time, differentiating days 7 and 49 (Fig. 7B). This further suggests an effect of M. smegmatis and Kampy inoculation on the relative abundances of species members within the broader microbial community.

Fig 7.

Microbial community structure after inoculation of engineered M. smegmatis and Kampy phage. Principal component analysis performed in R. (A) PCA on 16S rRNA sequencing reads from non-sterilized soil microcosms across all time points. (B) PCA on shotgun metagenomic sequencing reads from the inoculation site for non-sterilized soil microcosms on days 7 and 49.

DISCUSSION

Overview

This study evaluates the persistence and spread of genetically engineered M. smegmatis and its mycobacteriophage Kampy in sterilized and non-sterilized soil microcosms, providing crucial insights into the challenges of using exogenous microbes to address environmental issues within soil ecosystems. Four major findings emerge from our study. First, inoculated M. smegmatis and Kampy phage persist in soil microcosms over 7 weeks regardless of the method used to engineer M. smegmatis (plasmid transformation or genome integration) or whether the soil was sterilized. Second, Kampy population densities were several orders of magnitude lower in non-sterilized soil compared to sterilized soil, suggesting that non-sterilized soil conditions may limit the persistence of this phage. Third, although the higher abundance of Ms-pML(int) than Ms-pC3 in non-sterilized soil and the plasmid loss observed throughout the experiment is indicative of plasmid burden, some plasmids were nonetheless retained over 7 weeks. Fourth, observation of the spread of M. smegmatis and Kampy to 5 cm away from the inoculation site over 49 days was minimal, indicating potential challenges for future deployment of exogenous bacteria into soil environments.

Engineered M. smegmatis and mycobacteriophage Kampy persisted in microcosms regardless of soil sterilization or bacterial engineering method

If exogenous bacteria are to be deployed into the field, the persistence of inoculated constructs is essential. Although M. smegmatis remained detectable on average for all assays across all inoculated microcosms over the 49 day experiment, it decreased significantly in abundance in non-sterilized soil over time according to colony counting and 16S rRNA analysis, although this was not supported by shotgun metagenomic analysis. This declining prevalence of bacteria over several weeks when co-inoculated with phage into non-sterilized soil is consistent with other reports in the literature (35, 50–53). Although the decreased abundance of M. smegmatis over time in non-sterilized soil microcosms of the present study could suggest a continuing decline beyond the duration of the experiment, its survival over 49 days is nonetheless promising for in-field applications.

Although statistical tests on our colony count data indicate that M. smegmatis population densities at the inoculation site are not significantly altered by soil sterilization, important differences in the behavior of M. smegmatis between sterilized and non-sterilized soil were still observed. Notably, M. smegmatis abundance only changed significantly over time in non-sterilized soil, and the effect of the engineering method on M. smegmatis abundance was only significant in non-sterilized soil. Previous soil microcosm studies have shown significant differences in inoculated bacterial abundance between sterilized and non-sterilized soil; for example, P. fluorescens populations were significantly greater in sterilized than non-sterilized soil, by a factor of about 4, when co-inoculated with its lytic phage SBW25ø2 after 20 days (35). Additionally, E. coli population densities have been found to be approximately 1,000 times greater in sterilized than non-sterilized soil 21 days after the temperate transducing P1 phage and its E. coli host were co-inoculated into soil microcosms (50). These results suggest that there are species-specific differences in the persistence of bacteria inoculated into the soil and affirm that soil sterilization does impact bacterial colonization patterns.

The microbial community present in our non-sterilized soil samples was assessed through principal component analysis (PCA) of 16S rRNA and shotgun metagenomic relative abundance data. Grouping of samples by day observed in both PCA plots suggests that microbial community compositions change following inoculation with M. smegmatis and Kampy, remain steady for the next several weeks, and then change again after a longer period of incubation. These results support previous literature, which has characterized an effect of bacterial inoculation on the clustering of bacterial reads from soil microcosms (63, 64). The impact of inoculated M. smegmatis and Kampy on the broader biotic community emphasizes the importance of microcosm studies to ensure future field deployment does not adversely affect ecosystems.

Mycobacteriophage Kampy persisted at significantly lower abundance in non-sterilized soil than in sterilized soil

Understanding the persistence of phage inoculated into the soil is imperative both in consideration of phage as a predator for added engineered bacteria or even as a possible vector for in-situ editing in soil (65). As measured by plaque counts, the absolute abundance of Kampy on day 4 at the site of inoculation was less than an order of magnitude greater in sterilized than non-sterilized soil, but by day 49, it was about five orders of magnitude greater in sterilized soil. This corresponds to a statistically significant change in plaque counts over time in sterilized soil but not in non-sterilized soil microcosms. Kampy appears to increase in abundance over time in sterilized soil. The significant difference in Kampy counts between sterilized and non-sterilized microcosms may be explained by the abiotic and biotic aspects of non-sterilized soil dampening Kampy phage populations. Concentrations of nitrate, ammonia, phosphate, potassium, and organic matter have all been shown to change by less than 3-fold after 4 h of autoclaving soil at 150°C (66), whereas concentrations of dissolved organic carbon (DOC) can increase by 20-fold to 37-fold (67, 68). Past studies have demonstrated positive correlations between viral abundance and organic carbon, nitrate, potassium, and calcium (38, 69), but the effect of DOC on phage abundance still appears to be unknown. pH changes from autoclaving soil are unlikely to explain our results since autoclaving soil typically induces only small decreases in soil pH (66–68, 70–72).

Autoclaving soil also significantly reduces bacterial and fungal species richness and diversity (73); these changes may be beneficial to phage persistence. Many soil bacteria enter a dormant state due to carbon limitation resulting from the intense competition of natural soil environments (25, 57). Mimicking this state by limiting carbon in E. coli growth media has been shown to halt the replication of T4, λ, and P1 phages; this could similarly explain the low Kampy populations in our non-sterilized soil microcosms as a result of bacterial competition and dormancy (74, 75). Furthermore, native bacteria can release outer membrane vesicles that capture free phage virions, thereby blocking infection (76). In alignment with our results, phage populations have been observed to be substantially more abundant in sterilized than non-sterilized soil, with phage densities ranging from 104 to 106 PFU/g in sterilized soil versus nearly zero in non-sterilized soil (50). A later study reaffirmed this trend (35), but with much smaller magnitudes of difference likely due to variation in bacterial and phage species used and soil type. In particular, inoculation of either temperate or lytic phage can result in significantly different population abundances in soil; measurement of phage population density in sterilized soil microcosms inoculated with B. subtilis and temperate phage THø versus lytic phage SP10C demonstrated that the lytic phage population density leveled out at about 100 times greater than that of the temperate phage over 40 days (49). These results may be attributable to the higher replication rate of lytic phages or may suggest the presence of a hidden population of lysogenic phages integrated within their hosts and thereby undercounted by standard plate counts. Although this study extended these conclusions by investigating the behavior of temperate phage in non-sterilized soil microcosms, further investigation into the role of lysogeny or lytic phages in non-sterilized soil systems is necessary.

The pCherry3 plasmid is detrimental to the survival of M. smegmatis in non-sterilized soil

The novelty of this study, particularly, is examining the effect of the method utilized to engineer M. smegmatis (plasmid transformation versus genome integration) on the persistence and spread of M. smegmatis and its associated mycobacteriophage Kampy co-inoculated into soil microcosms. It is known that the genetic elements comprising a plasmid affect plasmid retention (77). Although antibiotic resistance genes (such as the hygromycin resistance gene on both of our engineered strains) can be advantageous in the soil (30, 31) and could therefore have resulted in some pressure for Ms-pC3 to maintain its plasmid, no exogenous hygromycin was added to our microcosms in order to minimize this effect.

M. smegmatis population densities at the inoculation site, as determined by colony counts, trend non-significantly higher in microcosms inoculated with M. smegmatis modified with genome integration (Ms-pML(int)) than in those with plasmid transformation (Ms-pC3). In non-sterilized soil specifically, M. smegmatis population densities were significantly different in microcosms inoculated with Ms-pML(int) than with Ms-pC3; this amounts to approximately a 3-fold greater abundance for Ms-pML(int) on average. Furthermore, the decline in the percentage of pink colonies from microcosms inoculated with Ms-pC3 indicates that over 49 days, on average, only about 27% of CFUs in sterilized soil and 50% of CFUs in non-sterilized soil retained the pCherry3 plasmid. 16S rRNA analysis also showed significantly different M. smegmatis relative abundances in non-sterilized microcosms inoculated with Ms-pML(int) compared with Ms-pC3, with Ms-pML(int) generally more abundant. Although this statistically significant difference in Ms-pC3 and Ms-pML(int) relative abundances was not supported by shotgun metagenomic analysis, the evidence from 16S rRNA, colony count, and colony color assays indicates a small but measurable survival advantage of the genome-integrated construct in non-sterilized soil. This affirms concerns about the negative impact of plasmid burden on host growth (32–34). However, the continued detection of pink colonies, the presence of Ms-pC3 colonies at approximately 106 CFU/g dry soil, and the non-zero relative abundances for all Ms-pC3 16S rRNA samples even after 49 days suggest plasmid-transformed constructs could still serve as an effective tool for deployment into non-sterilized soil.

Limited horizontal spread of M. smegmatis and mycobacteriophage Kampy under dry soil conditions

Successful deployment of engineered microbes in the field also requires the spread of these microbes through the inoculated environment. Although previous literature has demonstrated bacterial spread over time both horizontally over smaller distances and vertically (45, 47, 53, 59, 60), many of these experiments included regular watering (47, 53, 59, 60) and motile bacteria (45, 47, 53, 59, 60). M. smegmatis, the bacterial species used in our study, is traditionally considered a non-motile bacterium as it lacks flagellar structures, although it does have sliding motility across surfaces that have yet to be quantified in soil environments (78). Notably, fluid flow is a major driver of scalable bacterial spread through soil environments (79), and therefore, motility is not required for spread. Our experiment, which watered microcosms only twice over seven weeks, did not provide determinative support for a statistically significant spread of M. smegmatis in either sterilized or non-sterilized soil to 5 cm from the inoculation site over 49 days. Specifically, M. smegmatis population densities at 5 cm from the inoculation site were only significantly different than the abundances from control microcosms with no inoculation as assayed by 16S rRNA sequencing but not as measured by colony counts. In the plaque counting assay, spread was only suggested for phage in sterilized soil microcosms inoculated with Ms-pC3, indicating that spread to 5 cm over 49 days may be possible for phage under certain conditions but not all. Going forward, although research has shown an inverse relationship between soil microbial diversity and the survival of invading bacteria likely due to competition over resources (80), this must be extended to examining the impact of community structure on bacterial spread.

Furthermore, microcosm experiments cannot fully replicate the complexity of natural soil environments, including effectors of spread such as rainfall, the churning of soil by animals and plant roots, and non-homogeneity across soil types. Moreover, as autoclaving does not fully sterilize the soil (73, 81), abiotic conditions cannot be truly simulated. The limited research on bacterial spread, particularly investigating bacteria and phage in non-sterilized soil, highlights a critical gap in understanding the real-world applicability of exogenous microbes in soil environments.

Conclusions

This microcosm study was the first of its kind, to our knowledge, to measure the persistence and spread of co-inoculated phage and bacteria, engineered with plasmid transformation or genome integration, in sterilized and non-sterilized soil. The lack of conclusive spread observed for M. smegmatis and Kampy and the significantly lower Kampy abundance in non-sterilized soil compared with sterilized soil highlights a critical limitation for bioremediation applications requiring field deployment of bacteria or phages. However, the persistence of M. smegmatis and Kampy in both sterilized and non-sterilized soil over 49 days poses a promising avenue for future environmental applications of synthetic biology. The minor differences in persistence between plasmid-transformed and genome-integrated M. smegmatis constructs indicate that although it has some effect, plasmid burden may not be the most significant determinant of bacterial survival in soil conditions; however, loss of plasmid does occur without selection. Moving forward, this work underscores the necessity of developing approaches that enhance both persistence and dispersal of microbes in non-sterilized soils, providing a clear direction for future research aimed at optimizing microbial deployment for environmental applications.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

M. smegmatis engineering

M. smegmatis, a non-pathogenic, fast-growing, gram-positive microbe, was chosen for this experiment because of its ubiquity across soil ecosystems and potential for bioengineering applications (82). Two different engineered strains of M. smegmatis mc2155 (ATCC #700084) were used in the microcosm experiments: one with mCherry, a red fluorescence protein gene, transformed in a plasmid (called Ms-pC3) and one with mCherry integrated into the genome (called Ms-pML(int)). Both types of transformed DNA also conferred hygromycin resistance for selection during cloning. In brief, electrocompetent M. smegmatis cells were prepared by chilling cells (OD600 0.8–1.0) on ice, centrifuging (ThermoScientific Sorvall Legend Micro 17R Centrifuge) at approximately 2500 × g for 10 min, washing cells three times in 10% glycerol with centrifugation after each wash, and then resuspending cells in 10% glycerol and storing at −80°C until use (83, 84).

To engineer Ms-pC3, as adapted from several protocols (85, 86, Eppendorf Protocol No. 4308 915.522), 1 µg of pCherry3 (87) (AddGene #24659) DNA was added to 60 µL of electrocompetent M. smegmatis, mixed by pipetting, and then incubated on ice for 10 min. This mixture was transferred to a 1 mm gap electroporation cuvette and inserted into an Eppendorf Eporator. One pulse (5.0 msec time constant, 12 kV/cm field strength) was delivered. Electroporated cells were incubated on ice in the cuvette for 5 min, and then resuspended in 1 mL of Middlebrook 7H9 Media with 10% AD Supplement and transferred to a microcentrifuge tube. Cells were then incubated at 37°C with constant shaking (250 rpm) for 2 h before being plated (~100 µL per plate) on 7H9 agar plates with hygromycin (200 µg/mL) for selection. Plates were incubated at 37°C for 48 h. Single colonies were selected and incubated in 7H9 media with hygromycin (200 µg/mL) for 72 h at 37°C and 250 rpm. Fluorescence of the construct was confirmed on a BioTek Synergy H1 Microplate Reader (600 nm absorbance, 488 nm excitation wavelength, 530 nm emission wavelength).

To engineer Ms-pML(int), the construct ‘pMLcherry’ was created using pCherry3 (87) (AddGene #24659) and the integration vector pML1357 (88) (AddGene #32378). To replace the green fluorescence protein gene in pML1357 with mCherry, a restriction digest was performed on both pML1357 and pCherry3 using XbaI (cut site: TCTAGA) and HindIII (cut site: AAGCTT). The mCherry insert of pCherry3 and the backbone of pML1357 were gel extracted and purified using a Qiagen MinElute Gel Extraction Kit (#28604) following the manufacturer’s protocol and ligated overnight using a T4 ligase. The resulting 6408 bp ‘pMLcherry’ plasmid (Fig. S2) was transformed, as adapted from several protocols (89, 90), into Escherichia coli DH5-alpha by mixing ~100 ng of DNA with 50 µL of competent cells (Invitrogen DH5a #18258012) and incubating on ice for 30 min. Then, the microcentrifuge tube containing the cells and DNA was held in 42°C water for 45 s and then incubated on ice for 2 min. Cells were afterward suspended in 950 µL SOC Medium (NEB #B9020S) and incubated at 37°C with constant shaking (250 rpm) for 1 h. Cells (~100 µL per plate) were then plated on LB agar with hygromycin (200 µg/mL) and incubated overnight at 37°C. The plasmid was isolated with a New England BioLabs Monarch Plasmid MiniPrep Kit (#T1010S) according to the manufacturer and electroporated into M. smegmatis as previously described. This M. smegmatis strain was grown for approximately 72 h at 37°C on 7H9 agar plates with hygromycin (200 µg/mL). Fluorescence of this strain was confirmed via plate reader as previously described. Integration of the plasmid into the genome was confirmed by diagnostic PCR performed on a Thermocycler with NEB Q5 High-Fidelity Master Mix at an annealing temperature of 55°C with one primer (5’ - GGACGAGCTGTACAAGTGAAA) targeting pMLcherry and the other (5’ - TTCTTCTCGACACCGTTGAAG) targeting the M. smegmatis genome near the attB site. Confirmed colonies were then inoculated into 7H9 media without antibiotics to encourage the loss of unintegrated plasmid. Accordingly, Ms-pML(int) media displayed 3–5-fold lower red fluorescence levels compared to Ms-pC3 media (results not shown).

Soil collection and characterization

Soil was collected from a home garden in Williamsburg, Virginia (Latitude: 37.283115/N 37° 16' 59.215'', Longitude: −76.664902/W 76° 39' 53.646'') and homogenized by passage through a 1 mm sieve. A portion of the soil was sterilized by autoclaving on a G60 cycle three times and then baking at 150°C in an oven for 24 h. The dry weight of the soil was calculated by baking 60 g of wet weight of both the sterilized and non-sterilized soil for 16 h in an oven at 150°C. The soil moisture content was calculated using the difference in weight before and after baking divided by the dry weight.

The composition of the sterilized and non-sterilized soil was assessed (Table 1). In brief, organic carbon (as a percentage of weight) was measured by weight loss on ignition. Total carbon and nitrogen (as a percentage of weight) were measured using a Perkin-Elmer 2400 Elemental Analyzer. Total phosphorus (as a percentage of weight) was measured using an ashing/acid hydrolysis method (91).

TABLE 1.

Organic material, carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus concentrations (as a percentage of weight), as well as soil moisture content, of sterilized and non-sterilized soil

| % Organic material | % Carbon | % Nitrogen | % Phosphorous | Dry basis moisture content (g water/g dry soil) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-sterilized soil | 5.95 | 3.00 | 0.23 | 0.03 | 0.417 |

| Sterilized soil | 6.05 | 3.16 | 0.24 | 0.04 | 0.286 |

Preparation and sampling of soil microcosms

Microcosms were constructed in 1.9 L plastic containers, approximately 20 × 20 × 7 cm in dimensions with 16 evenly spaced drainage holes drilled into the bottom. There were a total of 18 microcosms, each containing approximately 500 g (dry weight) of soil. To bring the microcosms to approximately similar moisture contents, 25 mL of autoclaved (L60) water was added to each non-sterilized microcosm, and 130 mL was added to each sterilized microcosm.

Sterilized and non-sterilized soil microcosms were inoculated either with Ms-pC3 and Kampy or with Ms-pML(int) and Kampy (n = 3) (Fig. 7). There were additionally three sterilized and three non-sterilized control microcosms with no inoculation. Kampy, an A4 temperate mycobacteriophage, was selected due to existing transcriptomic characterization and its soil origins (92).

To add the M. smegmatis and Kampy, 13 g cores of soil were taken from the center of each microcosm. M. smegmatis was pelleted (4100 × g for 5 min), suspended in 1 mL of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to a concentration of approximately 108 CFU/g of dry soil, combined with approximately 107 PFU/g of dry soil of Kampy Phage, and added to the 13 g soil core. This soil core was thoroughly mixed and then placed back into the center of the microcosms. For control microcosms, 1 mL of uninoculated PBS was added to the soil core, thoroughly mixed, and placed back into the center. Hygromycin was not added to any of the microcosms so as to not increase the relative fitness of our engineered bacteria in the microcosms.

Sterilized microcosms were kept in a sterile hood throughout the duration of the experiment, whereas non-sterilized microcosms were kept on a benchtop, both receiving ambient room light. All microcosms were covered loosely with a plastic lid. Microcosms were watered on days 6 and 42 by sprinkling 15 and 50 mL, respectively, of autoclaved (L60) water over the top of each microcosm, resulting in relatively dry soil conditions.

Soil was sampled with a sterilized scoopula at the center of each microcosm (the inoculation site) and approximately 5 cm away from the inoculation site on days 4, 7, 14, 21, 28, and 49. Previous literature assaying inoculated bacteria and phage in soil microcosms supports sampling weekly for approximately a month to characterize early changes in microbial populations and then performing a final sample after, on average, a 3-week gap to test for stable persistence over time (40, 49). A distance of 5 cm from the inoculation site was selected by scaling previously characterized spread of non-motile bacteria in water-saturated non-sterilized soil microcosms (93) to our chosen timeframe.

Approximately 1 g of soil was removed each time soil was sampled. DNA was extracted from 0.25 g of this soil using a Qiagen DNeasy PowerSoil Pro Kit (#47014), according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and eluted into 50 µL of Elution Buffer. Approximately 0.5 g of the remaining sampled soil was used for standard bacterial plate counting and direct phage plaque assays. In brief, the ~0.5 g soil sample was suspended in 2 mL of phage buffer (10 mM Tris [pH 7.5], 10 mM MgSO4, 68 mM NaCl, and 1 mM CaCl2 dissolved in ddH2O), vortexed, and diluted in PBS as necessary. A relatively high dilution of the soil suspension (10−5–10−4) was used for bacterial plating of samples taken from the inoculation site to prevent non-M. smegmatis colonies from obscuring M. smegmatis colonies on the plate. For bacterial counting, 100 µL of the diluted suspension was spread on 7H9 agar plates. Then, the remaining solution was centrifuged (2,000 × g for 10 min), and the supernatant was filtered through a 0.22 µm filter and diluted in phage buffer as necessary. For direct plaque counting, 100 µL of this filtered sample was added to 1 mL of untransformed M. smegmatis and 900 µL of phage buffer, incubated for 20 min, then plated on LB bottom agar plates with 2 × 7H9 top agar (without antibiotics). Bacterial plates were typically counted after 72 h, and phage plates were typically counted after 48 hours. For bacterial plates, only colonies with morphology similar to M. smegmatis (identified as small, yellow-tinted, and wrinkled) were counted (94). Plates with no colonies or plaques were recorded as having an abundance of zero. Phage plates for which webbed lysis occurred were recorded as having 5,000 plaques, and plates that were completely cleared were recorded as having 10,000 plaques. CFU and PFU counts were normalized to the dry weight of the soil sample (Fig. 8).

Fig 8.

Normalization of CFU or PFU/g dry soil. Y = CFU or PFU/g dry soil, Vs = volume of liquid for soil suspension (2 mL in all cases here), MD = dry basis moisture content of soil (Table 1), mwet = mass of wet soil sampled, F = dilution factor (negative exponent), Vp = volume of dilution plated, X = CFU or PFU counted on a given plate.

PCR confirmation of colony and plaque identities

To confirm the identities of colonies and plaques being counted, random samples were selected from plates, underwent DNA amplification using PCR, and visualized via agarose gel electrophoresis. A 30-cycle PCR was performed on a Thermocycler at 55°C annealing for colony PCR and 67°C annealing for plaque PCR, with 98°C denaturation and 72°C extension steps for both. For colony PCR, 12 distinct colonies counted as M. smegmatis from four unique plates were selected using sterilized toothpicks. PCR was performed as previously described with 5 µL of NEB Q5 Hot-Start Hi-Fi Master Mix, 3 µL nuclease-free water, 0.5 µL each of M. smegmatis forward (5' - ATGGAACCTGTCGACGGGGC) and reverse (5' - ACTGCTCGTCGCGTGTCTGG) primers, and 1 µL of colony suspension. Products were run on a 1% agarose gel. For plaque PCR, 5 plugs from five unique plates, including one from a microcosm without M. smegmatis or Kampy added to serve as a negative control, were selected. Plaque plugs were heated to 85°C for 15 min to promote phage DNA solvation, then PCR was performed as previously described with 5 µL of NEB Q5 Hot-Start Hi-Fi Master Mix, 3 µL nuclease-free water, 0.5 µL each of Kampy forward (5′-CGTTCCTCACACCCATTCC) and reverse (5′-ACGCTGTGATCGAGACTGAC) primers, and 1 µL of plug suspension. Products were run on a 1% agarose gel with two Kampy-positive controls. Gel electrophoresis with both M. smegmatis and Kampy PCR products showed amplicons of the expected length for every colony and plaque tested, suggesting that counted colonies and plaques were accurately identified as M. smegmatis and Kampy, respectively.

Color analysis of plasmid retention in Ms-pC3

To qualitatively investigate the loss of plasmid in Ms-pC3, the amount of both pink and non-pink M. smegmatis colonies were counted for all Ms-pC3 plates sampled from the inoculation site on days 4, 7, 14, and 49 by two independent researchers. These counts were used to calculate the percentage of pink colonies on each plate. On plates with no colonies, no percentage was calculated. The average percentage of pink colonies for each group of at most three replicates calculated between the two researchers was always within 15% of each other, and these two values were averaged when there was disagreement.

To assess whether this colorimetric analysis was an appropriate measure of plasmid retention, PCR targeting plasmid DNA was performed on three non-pink and three pink colonies from sterilized soil microcosms on day 28 as previously described with 5 µL of NEB Q5 Hot-Start Hi-Fi Master Mix, 3 µL nuclease-free water, 0.5 µL each of M. smegmatis forward (5' - CTACAGCGTGAGCTATGAGAAA) and reverse (5' - CGAAACCCGACAGGACTATAAA) primers, and 1 µL of colony suspension. Products were run on a 1% agarose gel to confirm that pink colonies resulted in a visually denser band than non-pink colonies.

Bacterial 16S rRNA sequencing

Using DNA extractions from microcosm samples detailed above, 16S rRNA sequencing was performed by Illumina on all non-sterilized soil extractions. In brief, Omega Bioservices amplified 16S rRNA gene V3-V4 regions using a forward primer (5'- TCGTCGGCAGCGTCAGATGTGTATAAGAGACAGCCTACGGGNGGCWGCAG) and reverse primer (5'- GTCTCGTGGGCTCGGAGATGTGTATAAGAGACAGGACTACHVGGGTATCTAATCC). A 25-cycle PCR reaction using KAPA HiFi HotStart ReadyMix (Kapa Biosystems, Wilmington, MA) was performed with an initial denaturation at 95°C, followed by 55°C annealing, 72°C extension, and 72°C elongation steps. Mag-Bind RxnPure Plus magnetic beads (Omega Bio-tex, Norcross, GA) were used to clean up the PCR product. Another index PCR amplification and elongation step was then performed. Agilent 2200 TapeStation and QuantiFluor dsDNA System (Promega, Madison, WI) were used, respectively, to check and quantify the ~600 bp library. Nextseq (Illumina, San Diego, CA) then normalized, pooled, and sequenced the library on a 2 × 300 bp end-read setting.

To independently calculate M. smegmatis’s relative abundance in the microcosms, query sequences were created using the first and last 300 bp of M. smegmatis’s V3-V4 16S region (NCBI genome #CP000480.1). Both query sequences were reduced to the internal 280 bp to account for discrepancies at the edges of the 16S amplicons caused by PCR. The forward read files were queried with their respective M. smegmatis 16S region query sequence, and only 100% identity hits were used. The number of hits, relative to the total number of reads provided by Illumina in that sample, was considered the relative abundance of M. smegmatis in that microcosm (Tables S2 and S4).

Shotgun metagenomic sequencing

DNA extractions from non-sterilized microcosm samples on days 7 and 49 were sent for shotgun metagenomic sequencing by the Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation NGS Core using a NovaSeq X Plus (Illumina, San Diego, CA) with paired-end settings of 2 × 150 bp. Whole DNA genome libraries were prepared by the provider using the IDT xGen DNA EZ prep kit and with Kapa qPCR and Agilent TapeStation for quality control. Twelve paired-end shotgun metagenomic sequencing samples were first assessed for quality and adapter content utilizing FastQC v0.12.1 (95). Adapters and low-quality base pairs were trimmed with default parameters utilizing trim_galore v.0.6.10 and evaluated with FASTQC once more to ensure adapters were removed. Once the raw sequences were processed for quality, two main classifications of specific microbial presence were utilized.

First, the taxonomic classification of trimmed reads was performed utilizing Kraken2 v.2.1.3 (96) across RefSeq Bacterial (97) and Viral (98) libraries using default parameters. Confidence score thresholds of 0.2 and 0.5 were tested across all twelve samples, yielding a lower classification rate ranging from 3.63% to 11.43% and 0.85% to 8.61% reads classified, respectively. A default confidence score of 0.0 yielded the highest percentage of reads classified, ranging from 22.45% to 29.04%. Kraken2 classification results were then run through Bracken v2.9 with default parameters to estimate relative abundance.

Second, putative Kampy phage reads were identified by first converting trimmed reads from FASTQ to FASTA format utilizing seqtk v.1.4-r122. A reference database was then constructed from Kampy’s genome derived from PhagesDB (99) utilizing BLAST v2.15.0+ (100). Each FASTA sequencing read file was then run using the BLASTn command utilizing the new Kampy reference database (Table S6). All software applications were installed and managed on Anaconda3 conda environments and run using the Hima and Gust subclusters of the William & Mary High-Performance Computing cluster, which offered up to 128 cores per node for run parallelization and optimized computing time.

Statistical analysis and data visualization

All statistical analyses were performed in R v4.4.1 (101). The count data were analyzed with three-way repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) tests, with differences among M. smegmatis and Kampy counts assessed on the sterility of microcosms, the engineered bacterial strain, and time. We additionally performed two-way repeated measures ANOVAs on M. smegmatis and Kampy counts to further investigate specific sterility or engineered strain treatment, when applicable. Two-way repeated measures ANOVA tests were employed for 16S rRNA forward sequence relative abundances to compare differences across engineered bacterial strain and time. Two-way repeated measures ANOVA tests were also performed for shotgun metagenomic relative abundances found using Bracken v2.9 default settings to analyze engineered bacterial strain and time differences. Significance was set for all statistical tests at P < 0.05. As an additional test, permutational analysis was performed on all ANOVA tests for each replicate combination. To do this, replicates were manually switched one pair at a time across a comparison (sterilized versus non-sterilized soil or Ms-pC3 versus Ms-pML(int)) to assess whether the results became nonsignificant.

Visualization of data was performed with the ggplot2 package (102). The tidyr package was used to organize the data set nesting (103).

Principal component analysis

PCA plots were generated in R v4.4.1 (101) on 16S rRNA and shotgun metagenomic relative abundances. The 16S rRNA taxonomic classifications were obtained using Basespace 16S Metagenomics Labs v1.0.0 with the RefSeq RDP 16S v3 May 2018 DADA2 Database (104). For each sample, the counts were normalized to the total reads in that sample, yielding relative abundance. The shotgun metagenomic values were obtained using Bracken v2.9, as described above. Species for which every microcosm had the same relative abundance were removed from the data set since they contributed no information about variance (105). The PCAs were performed on the whole-community profile and visualized using factoextra (106), ggplot2 (102), and cowplot (107) packages.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We sincerely thank the Vice Provost for Research Dennis Manos for his financial and scientific support as well as the Dean of Arts and Science and Charles Center for student financial support. William & Mary’s High Performance Computing aided with computational resources. We also thank the 2023 William and Mary iGEM team, in particular Sofia Najjar and Lin Fang, for their assistance with the project.

This research was supported by the National Institute of Health through grant no. 1R15HD114135-01.

Contributor Information

Margaret S. Saha, Email: mssaha@wm.edu.

Julia C. van Kessel, Indiana University Bloomington, Bloomington, Indiana, USA

DATA AVAILABILITY

Relative abundance data from 16S rRNA sequencing are available on the SRA database under accession number PRJNA1189583. Relative abundance data from shotgun metagenomic sequencing are available on the SRA database under accession number PRJNA1189582. All other data are included in the article and supplemental material or available from the corresponding author upon request.

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

The following material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1128/aem.00212-25.

Comparison of bacteria and phage abundance within each microcosm.

All supplemental raw and processed data tables, and pMLcherry DNA sequence.

ASM does not own the copyrights to Supplemental Material that may be linked to, or accessed through, an article. The authors have granted ASM a non-exclusive, world-wide license to publish the Supplemental Material files. Please contact the corresponding author directly for reuse.

REFERENCES

- 1. Gebremedhin M, Coyne MS, Sistani KR. 2022. How much margin is left for degrading agricultural soils? The coming soil crises. Soil Systems 6:22. doi: 10.3390/soilsystems6010022 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Timmis K, Ramos JL. 2021. The soil crisis: the need to treat as a global health problem and the pivotal role of microbes in prophylaxis and therapy. Microb Biotechnol 14:769–797. doi: 10.1111/1751-7915.13771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Costantini EAC, Mocali S. 2022. Soil health, soil genetic horizons and biodiversity. J Plant Nutr Soil Sci 185:24–34. doi: 10.1002/jpln.202100437 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Schröder JJ, Schulte RPO, Creamer RE, Delgado A, van Leeuwen J, Lehtinen T, Rutgers M, Spiegel H, Staes J, Tóth G, Wall DP. 2016. The elusive role of soil quality in nutrient cycling: a review. Soil Use Manag 32:476–486. doi: 10.1111/sum.12288 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Pozza LE, Field DJ. 2020. The science of soil security and food security. Soil Security 1:100002. doi: 10.1016/j.soisec.2020.100002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Peixoto R, Voolstra CR, Stein LY, Hugenholtz P, Falcao Salles J, Amin SA, Häggblom M, Gregory A, Makhalanyane TP, Wang F, Adoukè Agbodjato N, Wang Y, Jiao N, Lennon JT, Ventosa A, Bavoil PM, Miller V, Gilbert JA. 2024. Microbial solutions must be deployed against climate catastrophe. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 100:fiae144. doi: 10.1093/femsec/fiae144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zhang T, Zhang H. 2022. Microbial consortia are needed to degrade soil pollutants. Microorganisms 10:261. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms10020261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ayilara MS, Babalola OO. 2023. Bioremediation of environmental wastes: the role of microorganisms. Front Agron 5:1183691. doi: 10.3389/fagro.2023.1183691 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ahmed AAQ, Odelade KA, Babalola OO. 2020. Microbial inoculants for improving carbon sequestration in agroecosystems to mitigate climate change, p 381–401. In Leal Filho W (ed), Handbook of climate change resilience. Springer International Publishing, Cham. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mason ARG, Salomon MJ, Lowe AJ, Cavagnaro TR. 2023. Microbial solutions to soil carbon sequestration. J Clean Prod 417:137993. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.137993 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Coban O, De Deyn GB, van der Ploeg M. 2022. Soil microbiota as game-changers in restoration of degraded lands. Science 375:abe0725. doi: 10.1126/science.abe0725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Xiao Z, Hou R, Li T, Meng F, Fu Q, Li M, Liu D, Ji Y, Dong S. 2023. Mechanism of microbial inhibition of rainfall erosion in black soil area, as a soil structure builder. Soil Tillage Res 233:105819. doi: 10.1016/j.still.2023.105819 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13. de Souza R, Ambrosini A, Passaglia LMP. 2015. Plant growth-promoting bacteria as inoculants in agricultural soils. Genet Mol Biol 38:401–419. doi: 10.1590/S1415-475738420150053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kozaeva E, Eida AA, Gunady EF, Dangl JL, Conway JM, Brophy JA. 2024. Roots of synthetic ecology: microbes that foster plant resilience in the changing climate. Curr Opin Biotechnol 88:103172. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2024.103172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Garner KL. 2021. Principles of synthetic biology. Essays Biochem 65:791–811. doi: 10.1042/EBC20200059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Aminian-Dehkordi J, Rahimi S, Golzar-Ahmadi M, Singh A, Lopez J, Ledesma-Amaro R, Mijakovic I. 2023. Synthetic biology tools for environmental protection. Biotechnol Adv 68:108239. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2023.108239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Xiang L, Li G, Wen L, Su C, Liu Y, Tang H, Dai J. 2021. Biodegradation of aromatic pollutants meets synthetic biology. Synth Syst Biotechnol 6:153–162. doi: 10.1016/j.synbio.2021.06.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Adams BL. 2016. The next generation of synthetic biology chassis: moving synthetic biology from the laboratory to the field. ACS Synth Biol 5:1328–1330. doi: 10.1021/acssynbio.6b00256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gonzalez JM, Aranda B. 2023. Microbial growth under limiting conditions-future perspectives. Microorganisms 11:1641. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms11071641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lembrechts JJ, van den Hoogen J, Aalto J, Ashcroft MB, De Frenne P, Kemppinen J, Kopecký M, Luoto M, Maclean IMD, Crowther TW, et al. 2022. Global maps of soil temperature. Glob Chang Biol 28:3110–3144. doi: 10.1111/gcb.16060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Weedon JT, Bååth E, Rijkers R, Reischke S, Sigurdsson BD, Oddsdottir E, van Hal J, Aerts R, Janssens IA, van Bodegom PM. 2023. Community adaptation to temperature explains abrupt soil bacterial community shift along a geothermal gradient on Iceland. Soil Biol Biochem 177:108914. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2022.108914 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rengel Z. 2011. Soil pH, soil health and climate change, p 69–85. In Singh BP, Cowie AL, Chan KY (ed), Soil health and climate change. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wu Y, Zeng J, Zhu Q, Zhang Z, Lin X. 2017. pH is the primary determinant of the bacterial community structure in agricultural soils impacted by polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon pollution. Sci Rep 7:40093. doi: 10.1038/srep40093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Demoling F, Figueroa D, Bååth E. 2007. Comparison of factors limiting bacterial growth in different soils. Soil Biol Biochem 39:2485–2495. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2007.05.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hobbie JE, Hobbie EA. 2013. Microbes in nature are limited by carbon and energy: the starving-survival lifestyle in soil and consequences for estimating microbial rates. Front Microbiol 4:324. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2013.00324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chevallereau A, Pons BJ, van Houte S, Westra ER. 2022. Interactions between bacterial and phage communities in natural environments. Nat Rev Microbiol 20:49–62. doi: 10.1038/s41579-021-00602-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wang C, Kuzyakov Y. 2024. Mechanisms and implications of bacterial–fungal competition for soil resources. ISME J 18:wrae073. doi: 10.1093/ismejo/wrae073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Schlatter DC, Bakker MG, Bradeen JM, Kinkel LL. 2015. Plant community richness and microbial interactions structure bacterial communities in soil. Ecology 96:134–142. doi: 10.1890/13-1648.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Blagodatskaya E, Kuzyakov Y. 2013. Active microorganisms in soil: critical review of estimation criteria and approaches. Soil Biol Biochem 67:192–211. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2013.08.024 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Leisner JJ, Jørgensen NOG, Middelboe M. 2016. Predation and selection for antibiotic resistance in natural environments. Evol Appl 9:427–434. doi: 10.1111/eva.12353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Billet L, Pesce S, Rouard N, Spor A, Paris L, Leremboure M, Mounier A, Besse-Hoggan P, Martin-Laurent F, Devers-Lamrani M. 2021. Antibiotrophy: key function for antibiotic-resistant bacteria to colonize soils—case of sulfamethazine-degrading Microbacterium sp. C448. Front Microbiol 12:643087. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.643087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ceroni F, Boo A, Furini S, Gorochowski TE, Borkowski O, Ladak YN, Awan AR, Gilbert C, Stan G-B, Ellis T. 2018. Burden-driven feedback control of gene expression. Nat Methods 15:387–393. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Radde N, Mortensen GA, Bhat D, Shah S, Clements JJ, Leonard SP, McGuffie MJ, Mishler DM, Barrick JE. 2024. Measuring the burden of hundreds of BioBricks defines an evolutionary limit on constructability in synthetic biology. Nat Commun 15:6242. doi: 10.1038/s41467-024-50639-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bentley WE, Mirjalili N, Andersen DC, Davis RH, Kompala DS. 1990. Plasmid-encoded protein: the principal factor in the “metabolic burden” associated with recombinant bacteria. Biotechnol Bioeng 35:668–681. doi: 10.1002/bit.260350704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Gómez P, Buckling A. 2011. Bacteria-phage antagonistic coevolution in soil. Science 332:106–109. doi: 10.1126/science.1198767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Meaden S, Paszkiewicz K, Koskella B. 2015. The cost of phage resistance in a plant pathogenic bacterium is context-dependent. Evolution 69:1321–1328. doi: 10.1111/evo.12652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Braga LPP, Spor A, Kot W, Breuil M-C, Hansen LH, Setubal JC, Philippot L. 2020. Impact of phages on soil bacterial communities and nitrogen availability under different assembly scenarios. Microbiome 8:52. doi: 10.1186/s40168-020-00822-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Roy K, Ghosh D, DeBruyn JM, Dasgupta T, Wommack KE, Liang X, Wagner RE, Radosevich M. 2020. Temporal dynamics of soil virus and bacterial populations in agricultural and early plant successional soils. Front Microbiol 11:1494. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.01494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wang Y, Liu Y, Wu Y, Wu N, Liu W, Wang X. 2022. Heterogeneity of soil bacterial and bacteriophage communities in three rice agroecosystems and potential impacts of bacteriophage on nutrient cycling. Environ Microbiome 17:17. doi: 10.1186/s40793-022-00410-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wei X, Ge T, Wu C, Wang S, Mason-Jones K, Li Y, Zhu Z, Hu Y, Liang C, Shen J, Wu J, Kuzyakov Y. 2021. T4-like phages reveal the potential role of viruses in soil organic matter mineralization. Environ Sci Technol 55:6440–6448. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.0c06014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Wang X, Tang Y, Yue X, Wang S, Yang K, Xu Y, Shen Q, Friman V-P, Wei Z. 2024. The role of rhizosphere phages in soil health. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 100:fiae052. doi: 10.1093/femsec/fiae052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Siyanbola KF, Ejiohuo O, Ade-adekunle OA, Adekunle FO, Onyeaka H, Furr C-L, Hodges FE, Carvalho P, Oladipo EK. 2024. Bacteriophages: sustainable and effective solution for climate-resilient agriculture. Sustain Microbiol 1:qvae025. doi: 10.1093/sumbio/qvae025 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Pratama AA, Terpstra J, de Oliveria ALM, Salles JF. 2020. The role of rhizosphere bacteriophages in plant health. Trends Microbiol 28:709–718. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2020.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ye M, Sun M, Huang D, Zhang Z, Zhang H, Zhang S, Hu F, Jiang X, Jiao W. 2019. A review of bacteriophage therapy for pathogenic bacteria inactivation in the soil environment. Environ Int 129:488–496. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2019.05.062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Henschke RB, Schmidt FRJ. 1989. Survival, distribution, and gene transfer of bacteria in a compact soil microcosm system. Biol Fert Soils 8. doi: 10.1007/BF00260511 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Locatelli A, Spor A, Jolivet C, Piveteau P, Hartmann A. 2013. Biotic and abiotic soil properties influence survival of Listeria monocytogenes in soil. PLoS One 8:e75969. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0075969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Juyal A, Eickhorst T, Falconer R, Baveye PC, Spiers A, Otten W. 2018. Control of pore geometry in soil microcosms and its effect on the growth and spread of Pseudomonas and Bacillus sp. Front Environ Sci 6:73. doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2018.00073 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Jiang J, Zhang R, Li R, Gu J-D, Li S. 2007. Simultaneous biodegradation of methyl parathion and carbofuran by a genetically engineered microorganism constructed by mini-Tn5 transposon. Biodegradation 18:403–412. doi: 10.1007/s10532-006-9075-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Pantastico-Caldas M, Duncan KE, Istock CA, Bell JA. 1992. Population dynamics of bacteriophage and Bacillus subtilis in soil. Ecology 73:1888–1902. doi: 10.2307/1940040 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Zeph LR, Onaga MA, Stotzky G. 1988. Transduction of Escherichia coli by bacteriophage P1 in soil. Appl Environ Microbiol 54:1731–1737. doi: 10.1128/aem.54.7.1731-1737.1988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Ye M, Sun M, Zhao Y, Jiao W, Xia B, Liu M, Feng Y, Zhang Z, Huang D, Huang R, Wan J, Du R, Jiang X, Hu F. 2018. Targeted inactivation of antibiotic-resistant Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa in a soil-lettuce system by combined polyvalent bacteriophage and biochar treatment. Environ Pollut 241:978–987. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2018.04.070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Yu P, Mathieu J, Yang Y, Alvarez PJJ. 2017. Suppression of enteric bacteria by bacteriophages: importance of phage polyvalence in the presence of soil bacteria. Environ Sci Technol 51:5270–5278. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.7b00529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Sun M, Ye M, Zhang Z, Zhang S, Zhao Y, Deng S, Kong L, Ying R, Xia B, Jiao W, Cheng J, Feng Y, Liu M, Hu F. 2019. Biochar combined with polyvalent phage therapy to mitigate antibiotic resistance pathogenic bacteria vertical transfer risk in an undisturbed soil column system. J Hazard Mater 365:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2018.10.093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Zhang R, Xu X, Chen W, Huang Q. 2016. Genetically engineered Pseudomonas putida X3 strain and its potential ability to bioremediate soil microcosms contaminated with methyl parathion and cadmium. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 100:1987–1997. doi: 10.1007/s00253-015-7099-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Molina L. 2000. Survival of Pseudomonas putida KT2440 in soil and in the rhizosphere of plants under greenhouse and environmental conditions. Soil Biol Biochem 32:315–321. doi: 10.1016/S0038-0717(99)00156-X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Araujo MAV, Mendonça-Hagler LC, Hagler AN, Elsas JD. 1994. Survival of genetically modified Pseudomonas fluorescens introduced into subtropical soil microcosms. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 13:205–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.1994.tb00067.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Maraha N, Backman A, Jansson JK. 2004. Monitoring physiological status of GFP-tagged Pseudomonas fluorescens SBW25 under different nutrient conditions and in soil by flow cytometry. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 51:123–132. doi: 10.1016/j.femsec.2004.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Sjogren RE. 1994. Prolonged survival of an environmental Escherchia coli in laboratory soil microcosms. Water Air Soil Pollut 75:389–403. doi: 10.1007/BF00482948 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Trevors JT, van Elsas JD, van Overbeek LS, Starodub ME. 1990. Transport of a genetically engineered Pseudomonas fluorescens strain through a soil microcosm. Appl Environ Microbiol 56:401–408. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.2.401-408.1990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. van Elsas JD, Trevors JT, van Overbeek LS. 1991. Influence of soil properties on the vertical movement of genetically-marked Pseudomonas fluorescens through large soil microcosms. Biol Fert Soils 10:249–255. doi: 10.1007/BF00337375 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Schackart KE, Graham JB, Ponsero AJ, Hurwitz BL. 2023. Evaluation of computational phage detection tools for metagenomic datasets. Front Microbiol 14:1078760. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2023.1078760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Zhang Z, Qu Y, Li S, Feng K, Wang S, Cai W, Liang Y, Li H, Xu M, Yin H, Deng Y. 2017. Soil bacterial quantification approaches coupling with relative abundances reflecting the changes of taxa. Sci Rep 7:4837. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-05260-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]