Abstract

Poly(L-lactic-acid) (PLLA) has shown significant promise in the fields of orthopedics and dentistry. However, its lack of inherent osteogenic activity limits its potential for further application in bone repair and fixation. In this study, we synthesized strontium carbonate (SrCO3) nanoparticles and incorporated them into PLLA to prepare bioactive composite scaffolds using selective laser sintering technology. The synthesized SrCO3 particles exhibited a unique microrod morphology with spike-like structures. In vitro degradation experiments demonstrated that SrCO3 effectively neutralized acidic byproducts and promoted the degradation of PLLA in a dose-dependent manner. Furthermore, in vitro cell culture experiments revealed that composite scaffolds containing 1–2 wt % SrCO3 significantly enhanced the adhesion, proliferation, and osteogenic differentiation of mouse bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells compared to the PLLA scaffolds. This can be attributed to the sustained release of Sr ions from the composite scaffolds. Overall, our study elucidates the positive effects of incorporating SrCO3 into the PLLA matrix, highlighting its potential as an alternative to the currently used PLLA implants for promoting degradation and facilitating osteogenesis.

1. Introduction

Poly(L-lactic-acid) (PLLA) has been widely used in absorbable sutures, bone tissue engineering scaffolds, orthopedic internal fixation materials, and related products due to its good biocompatibility, biosafety, and degradability. − PLLA degradation products can be metabolized in the body, ultimately generating carbon dioxide and water, thereby posing no toxic side effects to the human body. , Nonetheless, the absence of osteogenic activity associated with PLLA constrains its broader application in bone repair and fixation. ,

Numerous efforts have been undertaken to enhance osteogenic ability of PLLA, primarily involving the integration of bioactive ions and/or growth factors. − For instance, due to the excellent osteogenesis of strontium (Sr), Ding et al. incorporated Sr-doped hydroxyapatite into chitosan/dextran hydrogel. Their findings demonstrated that the hydrogel containing Sr-doped hydroxyapatite obviously promoted the cell proliferation and osteogenic differentiation of osteoblasts, consequently augmenting new bone formation in vivo. Additionally, various growth factors, such as bone morphogenetic protein-2, vascular endothelial growth factor, and platelet-derived growth factor BB, were incorporated into PLLA to enhance osteogenesis and vascularization. However, these active factors are expensive and prone to inactivity, while ensuring their safety and optimal dosages remains challenging. Furthermore, the efficacy of active ion doping is typically limited by the dopant content, thus hindering the attainment of optimal osteogenic effects. − In contrast, the addition of bioactive compounds to PLLA represents a straightforward and effective approach for enhancing its osteogenic properties.

Strontium carbonate (SrCO3), also recognized as strontianite, has recently gained great attention as a bioactive compound due to its sustained release of strontium (Sr) ions. , Sr is a crucial nutrient trace element in the human body, accounting for 0.00044% of body mass and 0.035% of the overall calcium content. , Sr, chemically and physically similar to Ca, is known to promote osteoblast activity while inhibiting osteoclast activity. − Studies have reported the efficacy of SrCO3 in treating osteoporosis at an oral dose of 600–700 mg/day, demonstrating favorable therapeutic outcomes. , In another study, a strontianite film deposited on a sodium titanate surface facilitated the local release of Sr ions in vivo, thereby promoting bone formation. Given its multiple functions in modulating bone physiology, SrCO3 presents a promising strategy for enhancing the bone regeneration capability of biomaterials.

In this study, we synthesized SrCO3 microrods with a spike-like structure and incorporated varying amounts of these microrods into PLLA to fabricate bioactive composite scaffolds via selective laser sintering technology. − Given that the degradation of SrCO3 produces alkaline degradation products capable of neutralizing the lactic acid generated during PLLA degradation, we examined the influence of SrCO3 on the neutralization effect and degradation characteristics of PLLA. Additionally, we conducted a systematic investigation into the mechanical strength, ion release, and cellular responses of the composite scaffolds.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Raw Materials

Strontium chloride hexahydrate (SrCl2·6H2O, purity 99.5%), sodium carbonate (Na2CO3, purity 99.99%), and citric acid were bought from Shanghai Aladdin Bio-Chem Technology Co., Ltd. Anhydrous ethanol is purchased from Tianjin Yufutai Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd.

2.2. Preparation of Strontium Carbonate

SrCO3 particles were synthesized via a coprecipitation method. Initially, 0.267 g of SrCl2·6H2O was dissolved in a 180 mL ethanol–water solution with a volume ratio of 8:1, denoted as solution A. Separately, 0.106 g of Na2CO3 was dissolved in a 40 mL ethanol–water solution with a volume ratio of 1:1, designated as solution B. Subsequently, 0.026 g of citric acid was added to solution A, followed by stirring for 36 h upon the addition of solution B to solution A. The resulting SrCO3 powder was obtained via centrifugation, followed by washing and drying at 60 °C.

2.3. Physicochemical Characterizations of SrCO3

The morphology of SrCO3 was observed by using scanning electron microscopy (SEM; EVO18, ZEISS, Germany). The phases of SrCO3 were measured by using X-ray diffraction (XRD; D8 Advance, Bruker Co., Germany). The functional groups of SrCO3 were identified by using Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy (ATR-FTIR; Nicolet 6700, Thermoelectric Corporation). Furthermore, the microstructure of SrCO3 was analyzed by using transmission electron microscopy (TEM; JEOL, 2100F, Japan).

2.4. Preparation and Characterization of Composite Scaffolds

Selective laser sintering (SLS) technology was employed to fabricate the PLLA and SrCO3/PLLA scaffolds. Initially, 50 mg of SrCO3 powder was uniformly mixed with 9.95 g of PLLA powder to produce a 0.5% SrCO3/PLLA composite powder. Similarly, PLLA composite powders of 1%, 2%, and 4% SrCO3 particles were prepared by adding 100 mg, 200 mg, and 400 mg of SrCO3 powder to 9.90 g, 9.80 g, and 9.60 g of PLLA, respectively. Following powder preparation, these composite powders were printed into composite scaffolds by a custom-built selective laser sintering system. The parameters utilized were a scanning space of 0.1 mm, layer thickness of 0.1 mm, laser power of 2 W, and scanning speed of 200 mm/s. The fracture morphologies of PLLA, 0.5% SrCO3/PLLA, 1% SrCO3/PLLA, 2% SrCO3/PLLA, and 4% SrCO3/PLLA scaffolds were observed using SEM (EVO18, ZEISS, Germany).

2.5. Mechanical Properties of Composite Scaffolds

The mechanical properties of the composite scaffolds were evaluated using a universal mechanical testing machine (Metes industrial systems Co. Ltd., China). For compressive strength testing, scaffold specimens sized at 5 × 4 × 3 mm3 were utilized, with a loading rate set to 1 mm/min. Tensile strength tests were conducted on specimens sized at 2 × 2 × 15 mm3, also with a loading rate set to 1 mm/min. Three-point bending strength tests were performed on 2 × 4 × 30 mm3 specimens using a 20 mm support span and a loading rate of 1 mm/min. Following the tests, the stress–strain curves and moduli of the scaffolds were automatically recorded by the software.

2.6. Ion Release of Composite Scaffolds

To assess the release of Sr ions from the prepared SrCO3/PLLA scaffolds, composite scaffolds (length: 5 mm, width: 4 mm, height: 5 mm) were immersed in 10 mL of phosphate buffer solution (PBS, pH 7.4) at a ratio of 62.5 g/L and kept in a shaker at 37 °C at a rate of 60 rpm for different time intervals (1, 4, 7, 14, 21, and 28 days). After soaking for a predetermined soaking period, the soaking solution was replaced with fresh PBS. The concentration of Sr ions in the soaking solution was quantified using inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectrometry (ICP-AES, Optima 5300DV, PerkinElmer, USA).

2.7. Degradation Experiment of Composite Scaffolds

The degradation experiment of composite scaffolds was conducted by immersing them in PBS at 37 °C under oscillating conditions. First, the weight of the dried composite scaffolds was measured (denoted as W 0). Subsequently, the composite scaffolds were immersed in PBS at a volume-to-weight ratio of 16 mL/g and kept in a shaker at 37 °C for 1, 4, 7, 14, 21, and 28 days. The pH value of the soaking solutions was monitored using a pH meter (Mettler Toledo, FE28, Switzerland). Simultaneously, the weight of the immersed scaffolds was measured (labeled as W 1). The weight loss (W L) of the composite scaffolds was then calculated using the following equation: W L % = (W 0–W 1)/W 0 × 100%.

2.8. Cell Behaviors

2.8.1. Cell Culture and Seed

Mouse bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (mBMSCs, ATCC) were used in this study. The cells were cultured in high-glucose Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (H-DMEM; Solarbio, China) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Cyagen, China), 100 μg/mL penicillin, and 100 U/mL streptomycin and incubated at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. Upon reaching 80–90% confluence, the cells were detached using 2.5% trypsin (Solarbio, China), followed by expansion until the desired cell number was attained. mBMSCs at passages 3–4 were utilized for assessing their biological behaviors.

2.8.2. Cell Cytotoxicity of Composite Scaffolds

The sterilized composite scaffolds (Φ 6 mm × 2 mm) were immersed in H-DMEM containing 10% FBS at a volume-to-weight ratio of 40 mL/g for 48 h, following which the extracts from the various scaffolds were collected via centrifugation. The cytotoxicity of these scaffold extracts was evaluated by using mBMSCs. Specifically, 150 μL of cell suspension at a density of 2 × 104 cells/mL was seeded into each well of a 96-well plate. After culturing for 1 day, the culture medium was replaced with extracts from different scaffolds. Subsequently, the cell viability was assessed by the Cell Counting Kit 8 (CCK-8, Solarbio, Beijing, China) at predetermined time points. Meanwhile, mBMSCs cultured with different extracts for varying durations were stained with calcein-AM/PI (Beyotime, Shanghai, China), and the stained cells were observed by using a fluorescence microscope (BX51 Olympus, Japan).

2.8.3. ALP and Alizarin Red Staining Assays

The alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity of mBMSCs on the scaffolds was evaluated as follows: initially, the different scaffolds were soaked in the medium for 24 h, and the extraction solution was collected. The weight-to-volume ratio of the scaffold in the culture medium was 25 mg mL–1. Subsequently, an osteogenic induction solution with 0.1 μM dexamethasone, 50 mM ascorbic acid, and 10 mM sodium β-glycerophosphoric acid was added. Cells were seeded at a density of 1 × 104 cells per well in a 48-well plate. The culture medium was refreshed with the extract solution every other day. After 7 days of incubation, the cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min, followed by three washes with PBS three times. Finally, the cells were stained using alkaline phosphatase (Beyotime, Shanghai, China) and Alizarin red staining kits (Solarbio, Beijing, China), and the staining results were observed under a fluorescence microscope (BX51, Olympus, Japan).

2.9. Statistical Analysis

All experimental data were obtained from at least three independent experiments and the data expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Differences between two groups were analyzed using Student’s t-test, with significance set at *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Synthesis and Characterization of SrCO3

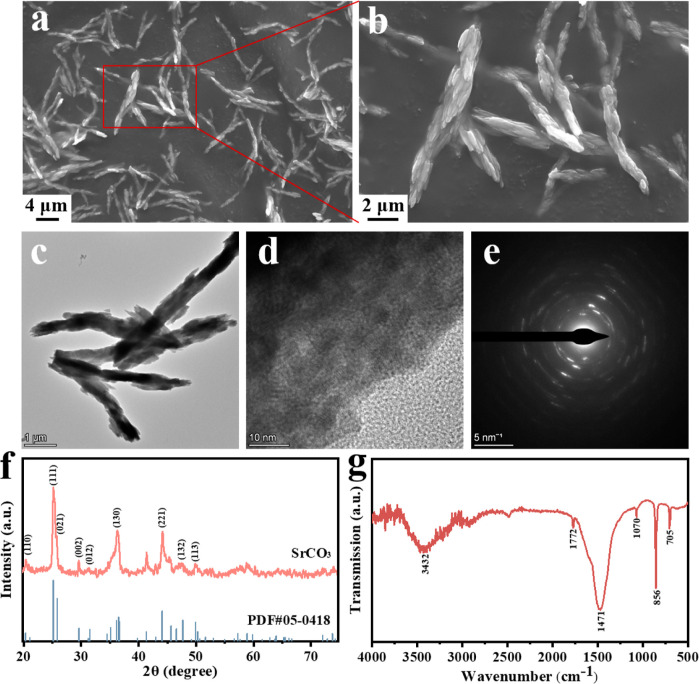

The microscopic morphology of SrCO3 particles synthesized via the coprecipitation method was observed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM). As shown in Figure a,b, the SrCO3 particles showed a rod-shaped morphology with a spike-like microstructure. The particle diameter ranged from approximately 600 to 1000 nm, with a length of about 10 μm, and exhibited a surface adorned with numerous rice-like granules. Further characterization of the synthesized SrCO3 particles was conducted by using transmission electron microscopy (TEM). As depicted in Figure c, a more detailed observation revealed that the SrCO3 microrods comprised numerous small nanorods resembling rice grains, each having a diameter of approximately 100 nm and a length ranging from 400 to 500 nm. Analysis of the lattice stripes in Figure d revealed a crystal face spacing of 2.05 Å, corresponding to the (221) face spacing of the SrCO3 crystals. Moreover, the selected area electron diffraction (SAED) pattern in Figure e exhibited regularly aligned bright spots and blurred diffraction rings, indicating the crystalline nature of the small nanorods within the larger microrods. Notably, the diffraction rings containing bright spots were identified as (132), (130), (002), and (111) planes, consistent with the XRD results of SrCO3 (Figure f). The crystal structure of the synthesized SrCO3 particles was further elucidated via X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis. The characteristic diffraction peaks observed at 2θ values of 20.32°, 25.17°, 29.61°, 31.49°, 36.52°, 44.08°, 47.69°, and 49.92° corresponded well with (110), (111), (002), (012), (130), (221), (132), and (113) crystal planes of strontianite (PDF#05–0418), respectively. Additionally, Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) was employed to identify the functional groups present in the synthesized SrCO3 powder (Figure g). The absorption peaks at 3432 and 1772 cm–1 were attributed to the O–H stretching and bending vibrations induced by hydrogen bonding in residual water, respectively. Furthermore, owing to the D3h point group symmetry of CO3 2–, the absorption peaks within the range of 400–800 cm–1 can be attributed to the vibration of CO3 2–. Specifically, the distinctive peaks at 1463, 1071, 862, and 708 cm–1 correspond to the asymmetric C–O stretching, symmetric C–O stretching, out-of-plane (φ) bending, and in-plane (β) bending vibrations, respectively. − These results indicate the successful synthesis of SrCO3 particles.

1.

Low (a) and high (b) magnification SEM images of SrCO3; TEM image (c), high-resolution TEM image (d), and SAED pattern (e) of SrCO3; XRD patterns (f) and FTIR spectra (g) of SrCO3.

3.2. Scaffold Degradation, pH Change, and Ion Release Kinetics

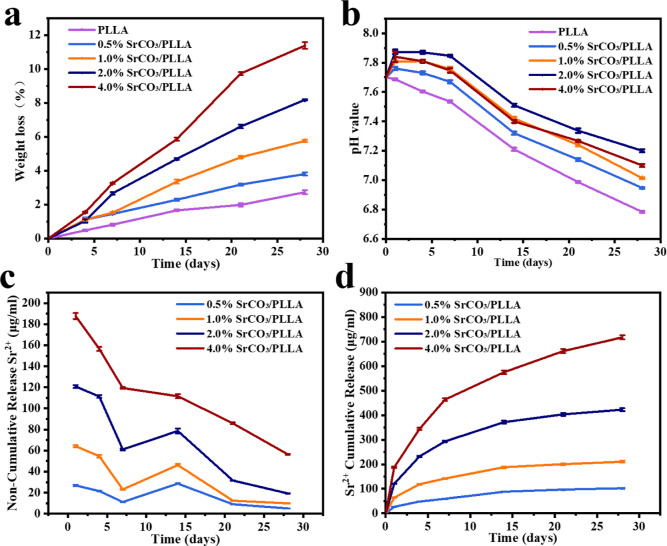

The rate of degradation of the bone scaffolds plays a crucial role in bone repair. If the degradation rate of bone scaffolds is too slow, it will hinder the formation and growth of new bone and may even trigger a chronic inflammatory response. , As shown in Figure a, we investigated the degradation properties of PLLA composite bone scaffolds composed of different amounts of SrCO3 particles. The mass loss of all scaffolds increased with the duration of immersion. After 28 days of immersion, the degradation rates of PLLA, 0.5% SrCO3/PLLA, 1% SrCO3/PLLA, 2% SrCO3/PLLA, and 4% SrCO3/PLLA scaffolds were measured at 2.71%, 3.80%, 5.75%, 8.18%, and 11.37%, respectively. Notably, the degradation rates of PLLA composite bone scaffolds containing SrCO3 were higher than those of the PLLA scaffolds. This indicates that SrCO3 significantly promotes the degradation of PLLA, with a higher proportion of SrCO3 resulting in a faster degradation rate of the composite bone scaffolds. Furthermore, the change of pH after the scaffolds were immersed for different times was also examined. As illustrated in Figure b, after 28 days of immersion, the pH values of the PLLA, 0.5% SrCO3/PLLA, 1% SrCO3/PLLA, 2% SrCO3/PLLA, and 4% SrCO3/PLLA scaffolds groups were recorded as 6.78, 6.94, 7.1, 7.2, and 7.01, respectively. A decreasing trend in pH values was observed with increasing soaking days, which was due to the lactic acid produced by the degradation of PLLA within scaffolds. Notably, the pH values of the composite bone scaffold groups exceeded those of the PLLA scaffold group. This disparity arises from the alkaline nature of SrCO3 in the composite bone scaffolds, which, as a strong alkali and weak acid salt, tends to alkalize upon degradation. Consequently, it effectively neutralizes a portion of the lactic acid generated by PLLA degradation. Interestingly, contrary to expectations, the pH values of the composite scaffold groups did not consist of higher proportions of the SrCO3 content, even after the same duration of immersion. Notably, after 28 days of immersion, the pH of the 4% SrCO3/PLLA scaffold group was lower than that of the 1% SrCO3/PLLA scaffold group. This unexpected observation could be attributed to several factors. First, the higher SrCO3 content in the 4% SrCO3/PLLA scaffold group might have led to a greater release of alkaline degradation products during immersion, initially raising the pH. However, the presence of a higher number of cavities produced in the scaffolds during degradation, likely due to the higher SrCO3 content, could have facilitated increased water penetration and consequently accelerated PLLA degradation. This accelerated degradation would result in a greater accumulation of lactic acid within the scaffold, potentially overwhelming the alkaline buffering capacity of the SrCO3 degradation products. Therefore, despite the higher initial alkalinity from the increased SrCO3 content, the inability of the alkaline degradation products to sufficiently neutralize the excess lactic acid could have caused the pH of the 4% SrCO3/PLLA scaffold group to be lower compared to the 1% SrCO3/PLLA scaffold group after 28 days of immersion.

2.

Weight loss (a) of the PLLA and SrCO3/PLLA composite scaffolds and the pH changes (b) of five groups of the scaffolds after being soaked in PBS for different times; noncumulative (c) and cumulative (d) release curves of Sr2+ from the SrCO3/PLLA composite scaffolds in PBS. Data are presented as mean ± SD (N = 3).

Based on the results of the scaffold degradation experiments and the observed pH changes of the scaffold soaking solution, it can be inferred that the degradation rate of PLLA is relatively slow. However, the alkaline byproduct of SrCO3 demonstrates a crucial role in neutralizing the lactic acid generated during PLLA degradation. This phenomenon initiates a positive feedback loop, thereby expediting the degradation of PLLA. Conversely, if the scaffold were to degrade more rapidly, resulting in an accumulation of lactic acid and the creation of an acidic microenvironment, it could trigger inflammation and stimulate the proliferation of osteoclasts. This, in turn, could lead to excessive bone resorption, potentially undermining the efficacy of bone repair processes. Notably, the alkaline products produced by SrCO3 degradation effectively counteract lactic acid accumulation, thereby forestalling the rapid formation of an acidic microenvironment during scaffold degradation. This delicate balance highlights the critical role of SrCO3 in modulating the degradation kinetics of PLLA scaffolds and maintaining a conducive environment for optimal bone regeneration.

Strontium is an important nutritional trace element within the human body, constituting approximately 0.00044% of the body mass. Its resemblance to elemental calcium, both chemically and physically, enables it to stimulate osteoblast proliferation while simultaneously inhibiting osteoclast activity. To explore the release of Sr ions from the composite scaffolds, the concentration of Sr ions from the composite bone scaffold groups was measured using inductively coupled plasma-atomic emission spectrometry (ICP-AES) on different days. The noncumulative release of Sr ions from the 0.5% SrCO3/PLLA, 1% SrCO3/PLLA, 2% SrCO3/PLLA, and 4% SrCO3/PLLA scaffolds is shown in Figure c. Notably, the concentration of Sr ions experiences an initial rapid decline within the first 7 days, succeeded by a subsequent increase followed by a decline post-7 days. Furthermore, Figure d displays the cumulative release of Sr ions from these scaffolds, showing a gradual augmentation in the Sr ion concentration with prolonged immersion duration. Importantly, a direct correlation is observed between the proportion of SrCO3 integrated into the scaffolds and the cumulative concentration of released Sr ions, with higher SrCO3 contents corresponding to elevated Sr ion release concentrations. These findings shed light on the intricate dynamics governing Sr ion release from composite scaffolds, underscoring the influence of the SrCO3 content on this phenomenon.

The results of the release of Sr ions from the scaffolds showed that when the SrCO3/PLLA scaffolds were immersed in PBS at an early stage, the SrCO3 microrods on the surface of the scaffolds initially degraded, resulting in the release of Sr ions. Consequently, higher concentrations of Sr ions were detected in the SrCO3/PLLA scaffolds up to 5 days postimmersion. However, upon prolonging the immersion period to 7 days, a gradual increase in the Sr ion concentration was observed. This augmentation can be attributed to the degradation of SrCO3 microrods within the scaffolds. Moreover, as the soaking duration increased, the SrCO3 content within the scaffolds diminished, consequently resulting in a gradual decline in the Sr ion concentration.

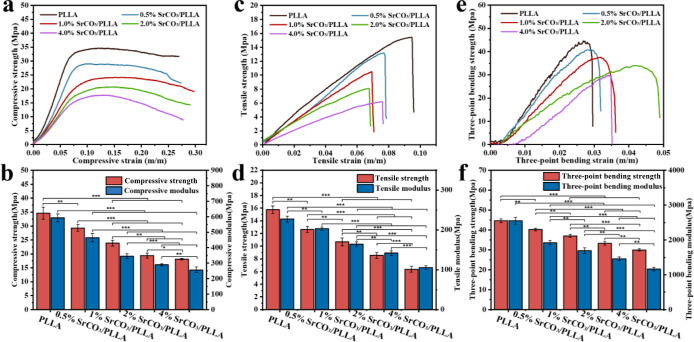

3.3. Mechanical Properties of Scaffolds

Bone scaffolds play a crucial role in providing temporary support during the early stage of implantation. − To determine the mechanical properties of these scaffolds, we conducted tests using a universal mechanical testing machine. The compressive stresses of the five scaffold groups increased with the strain up to the yield strength, followed by a gradual decrease (Figure a). The compressive strengths of the PLLA, 0.5% SrCO3/PLLA, 1% SrCO3/PLLA, 2% SrCO3/PLLA, and 4% SrCO3/PLLA scaffolds were 34.62, 29.30, 23.87, 19.41, and 18.12 MPa, respectively (Figure b). Correspondingly, the compressive moduli were 592.94, 464.63, 345.14, 289.39, and 256.83 MPa, respectively (Figure b). Additionally, the tensile and bending stress–strain curves of the scaffolds showed a linear increase without an obvious yielding stage, indicating evident brittle characteristics (Figure c,e). Moreover, the tensile strengths of the PLLA, 0.5% SrCO3/PLLA, 1% SrCO3/PLLA, 2% SrCO3/PLLA, and 4% SrCO3/PLLA scaffolds were 15.74 MPa, 12.63 MPa, 10.68 MPa, 8.54 MPa, and 6.35 MPa, respectively. The respective tensile moduli of these scaffolds were 227.13, 202.97, 163.99, 141.84, and 105.23 MPa (Figure d). Furthermore, the bending strengths of the PLLA, 0.5% SrCO3/PLLA, 1% SrCO3/PLLA, 2% SrCO3/PLLA, and 4% SrCO3/PLLA scaffolds were 44.69 MPa, 40.18 MPa, 37.06 MPa, 33.30 MPa, and 29.97 MPa, respectively. The bending moduli of these scaffolds were 2549.92 MPa, 1923.47 MPa, 1694.86 MPa, 1462.03 MPa, and 1164.52 MPa, respectively (Figure f).

3.

Compressive stress–strain curves (a) and compressive strength and modulus (b) of the PLLA and SrCO3/PLLA composite scaffolds; the tensile stress–strain curves (c) and tensile strength and modulus (d) of the composite scaffolds; the three-point bending stress–strain curves (e) and bending strength and modulus (f) of the composite scaffolds. Data are presented as mean ± SD (N = 3). *p < 0.05, * *p < 0.01, * **p < 0.001.

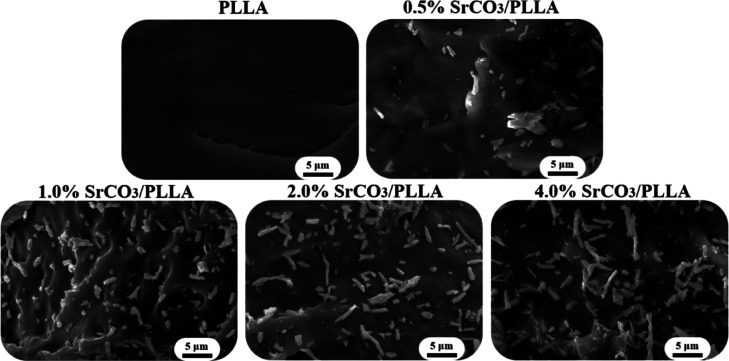

The stress–strain curves and strength modulus plots of the scaffolds demonstrate a notable decrease in the mechanical properties of the composite bone scaffolds with an increase in the SrCO3 content. In an effort to understand this phenomenon, the fracture surfaces of the PLLA and SrCO3/PLLA scaffolds were observed using SEM. As shown in Figure , the fracture surface of the PLLA scaffold was smooth. In contrast, the presence of visible SrCO3 microrods on the fracture surfaces of the SrCO3/PLLA scaffolds indicated a lack of clear bonding or interaction with the PLLA matrix. This observation suggests interfacial incompatibility between SrCO3 and the PLLA matrix. Therefore, the mechanical properties of the SrCO3/PLLA scaffolds were significantly lower than those of the PLLA scaffolds. Furthermore, it was evident that the higher SrCO3 content in the scaffolds corresponded to poorer mechanical properties. The degradation of the SrCO3 releases Sr ions, thereby enhancing the Sr ions concentration in the immersion solution. Moreover, a higher degradation rate of the scaffolds leads to increased release of Sr ions and a corresponding reduction of mechanical properties. In addition, the compressive strength of the scaffolds declines with the increase of the SrCO3 amount, which is probable because the increase in SrCO3 content is not beneficial to the scaffolds’ sintering, preventing the PLLA matrix from being sufficiently densified.

4.

SEM images of the fracture surface of the PLLA and SrCO3/PLLA composite scaffolds.

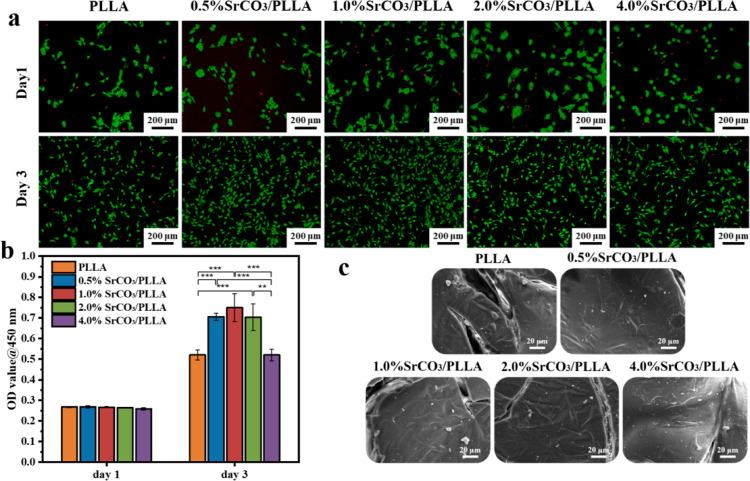

3.4. Cytocompatibility Evaluation

mBMSCs, known for their high self-renewal and potential for multidirectional differentiation into mesenchymal lineages such as osteoblasts, chondrocytes, and adipocytes, were widely used for assessing the cytocompatibility and osteogenic activity of biomaterials. − The cytocompatibility of mBMSCs following coculture with the scaffold-conditioned media was evaluated using fluorescent staining and a CCK-8 assay. As shown in Figure a, composite scaffold groups and PLLA scaffold group exhibited similar quantities of live and dead cells after a single day of coculturing with mBMSCs. Over the subsequent days of culture, there was a notable increase in the number of cells. After 3 days of coculturing mBMSCs with the scaffold-conditioned media, the number of live and dead cells in the PLLA scaffold group and the 4% SrCO3/PLLA scaffold group was comparable, displaying the lowest number of live cells. In contrast, the 1% SrCO3/PLLA scaffold group had the highest number of live cells. Moreover, as depicted in Figure b, the CCK-8 results indicated no substantial difference in the optical density (OD) values among the five scaffold groups after 1 day of coculturing. However, after 3 days of coculturing, a significant increase in the OD values was observed compared to the first day. This variation concurred with the observations of the live–dead fluorescent staining of the cells, suggesting favorable cytocompatibility across all five scaffold groups.

5.

(a) Fluorescent staining of the live and dead mBMSCs after culture with different scaffold-conditioned media for 1 and 3 days; (b) CCK-8 results of mBMSCs cultured with different scaffold-conditioned media for 1 and 3 days; (c) SEM images of mBMSCs adhesion after cocultured with different scaffolds for 3 days. Data are presented as mean ± SD (N = 3). *p < 0.05, * *p < 0.01, * **p < 0.001.

After 3 days of coculturing mBMSCs with the scaffolds, the adhesion of cells on the scaffolds is shown in Figure c. Notably, the spreading area of mBMSCs within the SrCO3/PLLA scaffolds surpassed that observed in the PLLA scaffolds, exhibiting more pronounced pseudopods. This observation indicates that SrCO3 in the composite scaffolds played a significant role in enhancing the adhesion and spreading of the cells.

Based on the comprehensive results of the cytocompatibility experiments of the scaffolds, it can be concluded that SrCO3 possesses the capability to enhance the proliferation of mBMSCs. However, it is noteworthy that the effect of promoting proliferation is not directly proportional to the SrCO3 content. Among the different scaffolds, the 1% SrCO3/PLLA scaffold showed the best effect in promoting cell proliferation. Furthermore, it was observed that an excessive Sr ion may lead to a certain degree of cytotoxicity.

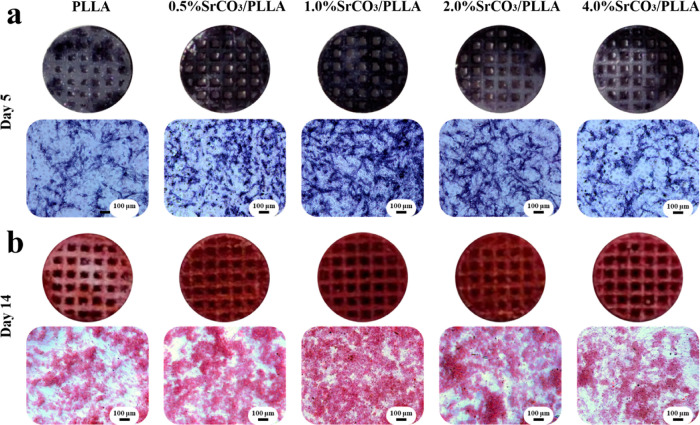

3.5. Osteogenic Properties Evaluation

The ALP activity serves as an early marker of osteogenesis, frequently employed to assess the osteogenic potential of materials. − As depicted in Figure a, ALP staining was performed on mBMSCs after a 5 day coculture with scaffolds under osteogenic induction conditions. Notably, the 1% SrCO3/PLLA scaffold group exhibited the most intense staining, accompanied by the largest staining area, indicative of the highest ALP activity. In contrast, the 0.5% SrCO3/PLLA and 2% SrCO3/PLLA scaffold groups demonstrated the second-highest ALP activity, while the PLLA and 4% SrCO3/PLLA scaffold groups exhibited the least ALP activity.

6.

(a) ALP staining of mBMSCs after coculturing with different scaffolds and their conditioned media for 5 days; (b) Alizarin red staining of mBMSCs after coculturing with different scaffolds and their conditioned media for 14 days.

Calcium nodules are formed through the deposition of calcium salts on the surface by osteoblasts, a process typically occurring during later stages of osteoblast differentiation, often regarded as a marker of late osteogenesis. , Alizarin red has the ability to undergo a chromogenic reaction with the calcium nodules, resulting in the production of a red compound. The results of Alizarin red staining of mBMSCs after a 14 day coculture with scaffolds under osteogenic induction conditions are shown in Figure b. These results are similar to those of the ALP staining results.

The collective results from the ALP and Alizarin red staining experiments indicate that Sr ions play a substantial role in promoting the osteogenic differentiation of stem cells, which is consistent with the results reported in the literature. For example, Zhou et al. fabricated a Sr-incorporated micro/nano-rough titanium surface (MNT-Sr) by hydrothermal treatment and showed that MNT-Sr was able to promote the recruitment and osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs, thus enhancing rapid osseointegration. However, the osteogenic properties of the scaffolds did not become stronger with the increase in the concentration of Sr ions, which may be caused by the fact that too many Sr ions can cause cytotoxicity.

Cell behavior is influenced by many factors such as scaffold composition and mechanical properties. Sr2+ has a promoting effect on osteoblasts in a certain concentration range and also inhibits osteoclast activity and differentiation. Benjamin et al. concluded that the concentration range for increased osteogenic differentiation by strontium ions was 0.4–0.9 mM, while proliferation of HBMSC was highest at 0.9–1.8 mM. In a physiological condition, mechanical stress can regulate cell shape, cytoskeletal organization, and gene expression. Wu et al. found that the osteogenic-related mRNA expression of ALP, Col I, and OCN in BMSCs was promoted under tensile stresses of 5% and 10%. The ALP staining and Alizarin red staining results in the experiments of the scaffolds and their extracts cocultured with mBMSCs all showed that the osteoblast differentiation effect of mBMSCs cocultured with the 1.0% SrCO3/PLLA scaffold and its extract was the best. The scaffold and cell coculture were affected by a combination of scaffold degradation rate, mechanical properties, and Sr ions, whereas the effect of scaffold extracts on osteogenic differentiation was the main factor due to the effect of Sr ions released from the scaffold. The consistent results of these two experiments indicate that Sr ions play a major role in promoting osteogenesis. In addition, our cell experiments were performed in a static culture environment and the effect of the mechanical properties of the scaffolds was negligible. It is noted that the effect of the Sr2+ ion on osteoblast differentiation depends on its concentration. The higher the SrCO3 content, the faster the rate of scaffold degradation and the higher the concentration of Sr ions released (Figure ). Therefore, the Sr2+ ion is more important in promoting osteogenesis.

4. Conclusions

SrCO3 microrods with a spike-like microstructure were successfully prepared by a coprecipitation method. The prepared SrCO3 was incorporated into PLLA to prepare SrCO3/PLLA composite scaffolds by SLS technology. The results showed that the prepared composite scaffolds exhibit favorable degradation properties and effectively counteract the acidic microenvironment triggered by the rapid production of lactic acid during PLLA degradation. However, it is noteworthy that the mechanical properties of the composite bone scaffolds were reduced compared with pure PLLA scaffolds, primarily due to the interfacial incompatibility between SrCO3 and PLLA. Moreover, the SrCO3/PLLA composite scaffold demonstrated sustained release of Sr ions. The composite scaffold exhibited the capacity to promote the proliferation and osteogenic differentiation of mBMSCs. Notably, the 1% SrCO3/PLLA scaffold demonstrated the most promising osteogenic properties. Nonetheless, it is important to note that an excessive concentration of Sr ions also led to a degree of cytotoxicity. In summary, our study underscores the significance of SrCO3 in the development of bone scaffolds for future investigations.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support to this research work from the National Science Foundation of China under Grant No. 32360232 and Jiangxi Provincial Natural Science Foundation under Grant Nos. 20232BAB216052 and 20242BAB23059.

§.

K.H. and Y.M. contributed equally to this work.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Khouri N. G., Bahú J. O., Blanco-Llamero C.. et al. Polylactic Acid (PLA): Properties, Synthesis, and Biomedical Applications-A Review of the Literature. J. Mol. Struct. 2024;1309:138243. doi: 10.1016/j.molstruc.2024.138243. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Qian G., Zhang L., Wang G., Zhao Z., Peng S., Shuai C.. 3D printed Zn-doped mesoporous silica-incorporated poly-L-lactic acid scaffolds for bone repair. Int. J. Bioprinting. 2024;7(2):346. doi: 10.18063/ijb.v7i2.346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopes M. S., Jardini A. L., Filho R. M.. Poly (lactic acid) production for tissue engineering applications. Procedia Eng. 2012;42:1402–1413. doi: 10.1016/j.proeng.2012.07.534. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rosli N. A., Karamanlioglu M., Kargarzadeh H.. et al. Comprehensive exploration of natural degradation of poly (lactic acid) blends in various degradation media: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021;187:732–741. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2021.07.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paula E. L., Mano V., Duek E. A. R., Pereira F. V.. Hydrolytic degradation behavior of PLLA nanocomposites reinforced with modified cellulose nanocrystals. Química Nova. 2015;38:1014–1020. doi: 10.5935/0100-4042.20150108. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmadi M., Seyedjafari E., Zargar S. J.. et al. Osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells cultured on PLLA scaffold coated with Wharton’s Jelly. EXCLI journal. 2017;16:785. doi: 10.17179/excli2016-741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kontogianni G. I., Bonatti A. F., De Maria C.. et al. Promotion of in vitro osteogenic activity by melt extrusion-based plla/pcl/phbv scaffolds enriched with nano-hydroxyapatite and strontium substituted nano-hydroxyapatite. Polymers. 2023;15(4):1052. doi: 10.3390/polym15041052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahraminasab M., Janmohammadi M., Arab S.. et al. Bone scaffolds: an incorporation of biomaterials, cells, and biofactors. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2021;7(12):5397–5431. doi: 10.1021/acsbiomaterials.1c00920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian G., Mao Y., Shuai Y.. et al. Enhancing bone scaffold interfacial reinforcement through in situ growth of metal–organic frameworks (MOFs) on strontium carbonate: Achieving high strength and osteoimmunomodulation. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2024;655:43–57. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2023.10.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szwed-Georgiou A., Płociński P., Kupikowska-Stobba B.. et al. Bioactive materials for bone regeneration: biomolecules and delivery systems. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2023;9(9):5222–5254. doi: 10.1021/acsbiomaterials.3c00609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding X., Li X., Li C.. et al. Chitosan/dextran hydrogel constructs containing strontium-doped hydroxyapatite with enhanced osteogenic potential in rat cranium. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2019;5(9):4574–4586. doi: 10.1021/acsbiomaterials.9b00584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oryan A., Alidadi S., Moshiri A.. et al. Bone morphogenetic proteins: A powerful osteoinductive compound with non-negligible side effects and limitations. Biofactors. 2014;40(5):459–481. doi: 10.1002/biof.1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z., Hu J., Ma P. X.. Nanofiber-based delivery of bioactive agents and stem cells to bone sites. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2012;64(12):1129–1141. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2012.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Witte T. M., Fratila-Apachitei L. E., Zadpoor A. A.. et al. Bone tissue engineering via growth factor delivery: from scaffolds to complex matrices. Regen. Biomater. 2018;5(4):197–211. doi: 10.1093/rb/rby013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahoo S., Sinha A., Das M.. Synthesis, characterization and in vitro biocompatibility study of strontium titanate ceramic: A potential biomaterial. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2020;102:103494. doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2019.103494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tovani C. B., Oliveira T. M., Gloter A.. et al. Sr2+-substituted CaCO3 nanorods: impact on the structure and bioactivity. Cryst. Growth Des. 2018;18(5):2932–2940. doi: 10.1021/acs.cgd.8b00017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anders D., Osmanovic A., Vohberger M.. Intra-and inter-individual variability of stable strontium isotope ratios in hard and soft body tissues of pigs. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2019;33(3):281–290. doi: 10.1002/rcm.8350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baptista, L. D. M. Antimicrobial properties of a Strontium-rich Hybrid System for bone regeneration. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng J., Guo J., Sun Z.. et al. Osteoblastic and anti-osteoclastic activities of strontium-substituted silicocarnotite ceramics: In vitro and in vivo studies. Bioactive materials. 2020;5(3):435–446. doi: 10.1016/j.bioactmat.2020.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demirel M., Kaya A. I.. Effect of strontium-containing compounds on bone grafts. J. Mater. Sci. 2020;55(15):6305–6329. doi: 10.1007/s10853-020-04451-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nedobukh T. A., Semenishchev V. S.. Strontium: source, occurrence, properties, and detection. Strontium Contamination in the Environment. 2020;88:1–23. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-15314-4_1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kołodziejska B., Stępień N., Kolmas J.. The influence of strontium on bone tissue metabolism and its application in osteoporosis treatment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021;22(12):6564. doi: 10.3390/ijms22126564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng X., Li C., Wang Z.. et al. Advanced applications of strontium-containing biomaterials in bone tissue engineering. Materials Today Bio. 2023;20:100636. doi: 10.1016/j.mtbio.2023.100636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meka S. R. K., Jain S., Chatterjee K.. Strontium eluting nanofibers augment stem cell osteogenesis for bone tissue regeneration. Colloids Surf., B. 2016;146:649–656. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2016.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian G., Zhang L., Shuai Y.. et al. 3D-printed CuFe2O4-MXene/PLLA antibacterial tracheal scaffold against implantation-associated infection. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2023;614:156108. doi: 10.1016/j.apsusc.2022.156108. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Qian G., Wang J., Yang L.. et al. A pH-responsive CaO2@ ZIF-67 system endows a scaffold with chemodynamic therapy properties. J. Mater. Sci. 2023;58(3):1214–1228. doi: 10.1007/s10853-022-08103-w. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Qian G., Wen T., Shuai Y.. et al. Photothermal and photodynamic effects of g-C3N4 nanosheet/Bi2S3 nanorod composites with antibacterial activity for tracheal injury repair. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2022;5(11):16528–16543. doi: 10.1021/acsanm.2c03569. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y., Zhong X., Li Y.. et al. Morphology-controllable self-assembly of strontium carbonate (SrCO3) crystals under the action of different regulators. J. Mater. Sci.: Mater. Electron. 2019;30:21150–21159. doi: 10.1007/s10854-019-02487-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Salmoria G. V., Pereira R. V., Fredel M. C.. et al. Properties of PLDLA/bioglass scaffolds produced by selective laser sintering. Polym. Bull. 2018;75:1299–1309. doi: 10.1007/s00289-017-2093-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nassar A. M., Elseman A. M., Alsohaimi I. H.. et al. Diaqua oxalato strontium (II) complex as a precursor for facile fabrication of Ag-NPs@SrCO3, characterization, optical properties, morphological studies and adsorption efficiency. Journal of coordination chemistry. 2019;72:771–785. doi: 10.1080/00958972.2019.1588964. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tipcompor N., Thongtem T., Phuruangrat A.. et al. Characterization of SrCO3 and BaCO3 nanoparticles synthesized by cyclic microwave radiation. Materials letters. 2012;87:153–156. doi: 10.1016/j.matlet.2012.08.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Divya A., Mathavan T., Harish S.. et al. Synthesis and characterization of branchlet-like SrCO3 nanorods using triethylamine as a capping agent by wet chemical method. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019;487:1271–1278. doi: 10.1016/j.apsusc.2019.04.173. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Için K., Öztürk S., Sünbül S. E.. Investigation and characterization of high purity and nano-sized SrCO3 production by mechanochemical synthesis process. Ceram. Int. 2021;47(23):33897–33911. doi: 10.1016/j.ceramint.2021.08.302. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shuai C., Yang W., Feng P.. et al. Accelerated degradation of HAP/PLLA bone scaffold by PGA blending facilitates bioactivity and osteoconductivity. Bioactive Materials. 2021;6(2):490–502. doi: 10.1016/j.bioactmat.2020.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu G., Liu Y., Iizuka T.. et al. The effect of a slow mode of BMP-2 delivery on the inflammatory response provoked by bone-defect-filling polymeric scaffolds. Biomaterials. 2010;31(29):7485–7493. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian G., Zhang L., Liu X.. et al. Silver-doped bioglass modified scaffolds: A sustained antibacterial efficacy. Mater. Sci. Eng: c. 2021;129:112425. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2021.112425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu S., Liu X., Yeung K. W. K.. et al. Biomimetic porous scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. Mater. Sci. Eng. R: Rep. 2014;80:1–36. doi: 10.1016/j.mser.2014.04.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ho-Shui-Ling A., Bolander J., Rustom L. E.. et al. Bone regeneration strategies: Engineered scaffolds, bioactive molecules and stem cells current stage and future perspectives. Biomaterials. 2018;180:143–162. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2018.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bose S., Bhattacharjee A., Banerjee D.. et al. Influence of random and designed porosities on 3D printed tricalcium phosphate-bioactive glass scaffolds. Addit. Manuf. 2021;40:101895. doi: 10.1016/j.addma.2021.101895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao H., Liu M., Wang J.. et al. 3D-printed bone scaffolds containing graphene oxide/gallium nanocomposites for dual functions of anti-infection and osteogenesis differentiation. Surf. Interfac. 2025;57:105770. doi: 10.1016/j.surfin.2025.105770. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zong H., Liu Y., Miao J.. et al. RIOK3 potentially regulates osteogenesis-related pathways in ankylosing spondylitis and the differentiation of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Genomics. 2023;115(6):110730. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2023.110730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian G., Zhang L., Li X.. et al. Construction of Fe3O4-loaded mesoporous carbon systems for controlled drug delivery. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2021;4(6):5304–5311. doi: 10.1021/acsabm.1c00422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S., Jia Z., Dai M.. et al. Advances in natural and synthetic macromolecules with stem cells and extracellular vesicles for orthopedic disease treatment. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024;268:131874. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.131874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croes M., Oner F. C., Kruyt M. C.. et al. Proinflammatory mediators enhance the osteogenesis of human mesenchymal stem cells after lineage commitment. PloS one. 2015;10(7):e0132781. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0132781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao L., Xia L., Chang J.. et al. The synergistic effects of Sr and Si bioactive ions on osteogenesis, osteoclastogenesis and angiogenesis for osteoporotic bone regeneration. Acta biomaterialia. 2017;61:217–232. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2017.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian G., Mao Y., Zhao H.. et al. pH-Responsive nanoplatform synergistic gas/photothermal therapy to eliminate biofilms in poly (L-lactic acid) scaffolds. J. Mater. Chem. B. 2024;12(5):1379–1392. doi: 10.1039/D3TB02600K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao D., Zhang J., Zhang C.. et al. The role of calcium phosphate surface structure in osteogenesis and the mechanisms involved. Acta biomaterialia. 2020;106:22–33. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2019.12.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Declercq H. A., Verbeeck R. M. H., De Ridder L. I.. et al. Calcification as an indicator of osteoinductive capacity of biomaterials in osteoblastic cell cultures. Biomaterials. 2005;26(24):4964–4974. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al Mamun M. A., Hosen M. J., Khatun A.. et al. Tridax procumbens flavonoids: a prospective bioactive compound increased osteoblast differentiation and trabecular bone formation. Biol. Res. 2017;50:1–10. doi: 10.1186/s40659-017-0134-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Zhou C., Xu A., Wang D.. et al. The effects of Sr-incorporated micro/nano rough titanium surface on rBMSC migration and osteogenic differentiation for rapid osteointegration. Biomater. Sci. 2018;6(7):1946–1961. doi: 10.1039/C8BM00473K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen F., Tian L., Pu X.. et al. Enhanced ectopic bone formation by strontium-substituted calcium phosphate ceramics through regulation of osteoclastogenesis and osteoblastogenesis. Biomater. Sci. 2022;10(20):5925–5937. doi: 10.1039/D2BM00348A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruppke B., Heinemann C., Wagner A. S.. et al. Strontium ions promote in vitro human bone marrow stromal cell proliferation and differentiation in calcium-lacking media. J. Development, Growth & Differentiation. 2019;61(2):166–175. doi: 10.1111/dgd.12588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu P., Tu J., Wang W.. et al. Effects of mechanical stress stimulation on function and expression mechanism of osteoblasts. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022;10:830722. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2022.830722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y., Zhang P., Dai Q.. et al. Effect of mechanical stretch on the proliferation and differentiation of BMSCs from ovariectomized rats. Mol Cell Biochem. 2013;382:273–282. doi: 10.1007/s11010-013-1744-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]