Abstract

Background

Stroke is one of the leading causes of adult disability, often resulting in motor dysfunction and brain network reorganization. Brain-computer interface (BCI) systems offer a novel approach to post-stroke motor rehabilitation, with motor imagery (MI) serving as a key paradigm that requires decoding left and right-hand MI differences to optimize system performance. However, the neural dynamics underlying these differences, especially from the perspective of Electroencephalography(EEG) microstate, remain poorly understood in acute stroke patients.

Methods

This study enrolled 14 acute stroke patients and recorded their EEG data during left and right-hand MI tasks. Four EEG microstate (A, B, C, and D) were analyzed to extract temporal feature parameters, including Duration, Occurrence Coverage, and transition probabilities(TP). Significant features were used to construct classification models using Linear Discriminant Analysis(LDA), Support Vector Machines(SVM), and K-Nearest Neighbors(KNN) algorithms.

Results

Microstate analysis revealed significant differences in temporal features of microstate A and C during left and right-hand MI tasks. During left-hand MI, microstate A exhibited longer Duration(Pfdr=0.032), higher Occurrence(Pfdr=0.018), and greater Coverage(Pfdr=0.004) compared to the right-hand, whereas microstate C showed the opposite pattern(Pfdr=0.044, Pfdr=0.004, Pfdr=0.004). Additionally, the TP from microstate B→A, D→A and D→C also demonstrated significant differences(Pfdr=0.04, Pfdr<0.001, Pfdr=0.006). Among classification models, the KNN algorithm achieved the highest accuracy of 75.00%, outperforming LDA and SVM. Fisher analysis indicated that the Occurrence of microstate C was the most discriminative feature for distinguishing between left and right-hand MI tasks in acute stroke patients.

Conclusion

Differences in EEG microstate features during left and right-hand MI tasks in acute stroke patients may reflect lateralized mechanisms of brain network reorganization. Microstate features hold significant potential for both post-stroke brain function assessment and the optimization of BCI systems. These features could enhance adaptive BCI strategies in acute stroke rehabilitation.

Keywords: EEG microstate, Acute stroke, Motor imagery, Brain-Computer interface, Brain network dynamics

Introduction

Stroke is a severe neurological disorder that causes motor impairments, cognitive deficits, and language difficulties, imposing a significant burden on patients and their families [1]. Globally, stroke is one of the leading causes of adult disability [2]. Brain-computer interface (BCI) technology, as an advanced neurorehabilitation tool, offers promising possibilities for post-stroke motor function recovery [3]. BCI systems decode neural activity to interpret user intentions, enabling patients to control external devices through thought, bypassing damaged neural pathways. Motor imagery (MI) is a key paradigm in BCI applications, allowing users to operate BCI systems by imagining body movements [4]. Accurate differentiation of left and right-hand MI is crucial for developing effective BCI systems and optimizing rehabilitation strategies in acute stroke patients.

Currently, signals for BCI systems can be acquired through various modalities, including Electroencephalography(EEG), Near-Infrared Spectroscopy(NIRS), functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging(fMRI), and Magnetoencephalography(MEG) [5]. EEG, due to its non-invasive nature, high temporal resolution, accessibility, and cost-effectiveness, is widely used [6]. Studies have shown that EEG signals demonstrate classification capabilities for different motor states and movements during MI tasks. Chatterjee et al. extracted EEG features using statistical, wavelet, and power-based methods, achieving classification accuracies of 85% and 85.71% for left and right-hand MI using Support Vector Machines(SVM) and Multilayer Perceptron(MLP,) respectively [7]. Wang et al. extracted EEG features using statistical, wavelet, power, Sample Entropy(SampEn), and Common Spatial Patterns(CSP) methods, achieving a classification accuracy of 75.22% for left and right-hand MI using SVM [8]. Wang et al. demonstrated the effectiveness of EEG signals in distinguishing MI tasks by extracting SampEn features for training and classification [9]. However, most studies focus on single channels (e.g., C3, C4) or specific brain regions for left and right-hand MI analysis, potentially overlooking spatial information. Some studies suggest that incorporating more EEG electrodes improves the performance of MI-BCI systems [10, 11].

EEG microstate analysis incorporates all EEG channels across the cerebral cortex and serves as an effective tool for studying brain network dynamics. It evaluates brain network changes on a millisecond timescale with high temporal resolution and reliability [12–15]. Several researchers have explored MI of the left and right-hand using EEG microstate. Liu et al. extracted microstate parameters such as duration, occurrence frequency, coverage, and transition probability during left and right-hand MI tasks in healthy individuals. The study found significant differences in parameters of microstate 3 and 4 between left and right-hand MI, achieving an average classification accuracy of 89.17% using an SVM model [16]. Cui et al. investigated average EEG microstate parameters for left and right-hand MI across sessions in healthy individuals, achieving an average classification accuracy of 70.21% and an AUC of 0.83 using an SVM model [17]. These studies demonstrate the effectiveness of EEG microstate in distinguishing between left and right-hand MI. Nevertheless, to the best of our knowledge, no studies have investigated the use of EEG microstate to differentiate left and right-hand MI in acute stroke patients, particularly considering the significant alterations in brain network dynamics caused by stroke. Acute stroke patients are typically in the early stages of brain network reorganization, with high neuroplasticity and significant potential for functional recovery. Investigating their brain dynamic features is crucial for understanding the neural mechanisms underlying early-stage rehabilitation following a stroke.

In summary, we hypothesize that significant differences in large-scale brain network dynamics exist during left and right-hand MI in acute stroke patients, aiding in the differentiation of these tasks. To test this hypothesis, we included EEG data from 14 acute stroke patients during left and right-hand MI. We analyzed microstate feature differences and used significantly different parameters to construct machine learning models for MI classification. This study aims to validate the effectiveness of EEG microstate in distinguishing left and right-hand MI in acute stroke patients and to explore their potential applications in stroke rehabilitation.

Method

Participant

The participants in this study were selected from the publicly available dataset provided by Liu et al. [18]. Due to data quality issues in some of the raw recordings—such as motion artifacts, non-stationarity, and feature covariance shift—only 14 acute stroke patients were included following a rigorous quality screening process. Among them, 12 were male, with a mean age of 58 ± 11.64 years and an average onset time of 4.14 ± 3.96 h. All participants and their families provided informed consent, and acquisition of this public dataset was approved by the Ethics Committee of Xuanwu Hospital, Capital Medical University (No. 2021 − 236). Detailed clinical information is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinical information for stroke patients

| ID | Sex | Age | Handedness | Duration | Stroke Location | Paralysis Side | NIHSS | MBI | mRS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | male | 45 | right | 1 | Left pons | right | 11 | 50 | 4 |

| 2 | male | 60 | right | 2 | Left cerebellum, bilateral paraventricular, Right corona radiata | left | 3 | 90 | 1 |

| 3 | male | 62 | right | 5 | Left pons | right | 2 | 100 | 1 |

| 4 | male | 57 | right | 3 | Left paraventricular | right | 6 | 55 | 1 |

| 5 | male | 55 | right | 2 | Right pons | left | 3 | 55 | 0 |

| 6 | male | 31 | right | 7 | Right paraventricular | left | 5 | 55 | 4 |

| 7 | female | 67 | right | 2 | Left pons | right | 2 | 75 | 1 |

| 8 | male | 63 | left | 1 | Right fronto-parietal temporo-occipital lobe, Right inner watershed | left | 7 | 55 | 1 |

| 9 | male | 60 | right | 3 | Right paraventricular, Right basal ganglia | left | 3 | 85 | 1 |

| 10 | male | 53 | right | 16 | Left thalamus | right | 1 | 95 | 0 |

| 11 | female | 59 | right | 5 | Left corona radiata, Left centrum semiovale | right | 3 | 80 | 3 |

| 12 | male | 74 | right | 2 | Left pons | right | 3 | 81 | 4 |

| 13 | male | 49 | right | 7 | Right internal capsule | left | 3 | 88 | 4 |

| 14 | male | 77 | right | 2 | Left pons | right | 7 | 60 | 4 |

Duration: The time from the stroke onset to patient enrolling, unit: hours. ParalysisSide: The side of limb paralysis due to stroke. NIHSS: National Institute of Health stroke scale. MBI: Modified Barthel Index. mRS: modified Rankin scale

Experimental paradigm

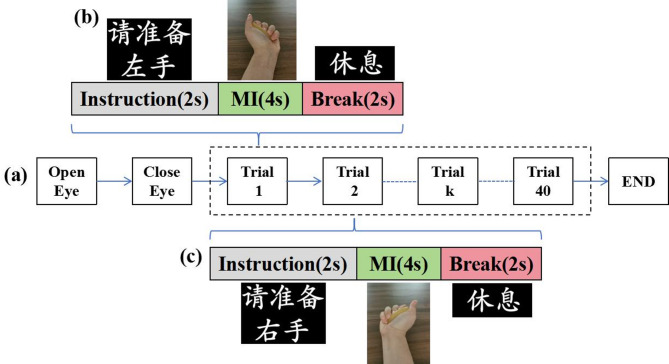

The experimental workflow is illustrated in Fig. 1. Before the experiment, participants were seated comfortably and fitted with an EEG cap. A computer placed 80 cm away displayed task instructions. Each participant completed tasks including 1-minute eye-open, 1-minute eye-closed, and MI sessions (Fig. 1a). The MI session consisted of 40 trials, with each trial divided into three phases: Instruction (2 s), MI (4 s), and Break (2 s) (Figs. 1b, c). During the MI phase, a video was displayed on the screen, guiding participants to imagine grasping a spherical object with their left or right hand. The trials alternated between left-hand MI (first trial) and right-hand MI (second trial) until all 40 trials were completed (END). Each stroke patient performed 20 left-hand and 20 right-hand MI tasks.

Fig. 1.

Experimental flow. (a) MI task paradigm, (b) left-hand MI task, (c) right-hand MI task

EEG data acquisition and preprocessing

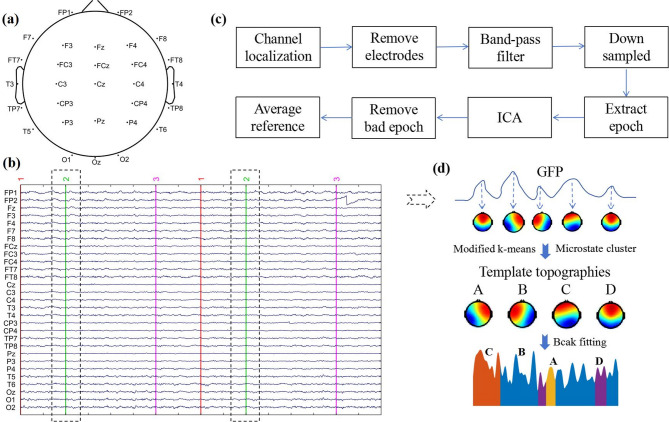

The wireless multi-channel EEG acquisition system (ZhenTec NT1, Xi ‘an ZhenTec Intelligence Technology Co. Ltd., China) was used to obtain the EEG data of subjects during MI. The EEG cap consists of 29 saline electrode channels arranged according to the international 10–10 system, as shown in Fig. 2a. During the data acquisition, electrode impedance was kept ≤ 20 kΩ, with a sampling frequency of 500 Hz, a common-mode rejection ratio of 120 dB, an input impedance of 1 GΩ, input noise less than 0.4 µVrms, and a resolution of 24 bits.

Fig. 2.

EEG acquisition and processing analysis. (a) electrode channel location, (b) EEG marker during the MI task, “2” indicates the start of MI, (c) EEG preprocessing process, (d) EEG microstate analysis process

The raw EEG data were preprocessed using MATLAB 2016a, including channel localization, removal of irrelevant electrodes, band-pass filtering (1–30 Hz), downsampling to 250 Hz, extraction of MI segments, Independent Component Analysis (ICA), removal of bad segments, and re-referencing to the average:

Channel localization: EEG data were matched to specific channel locations.

Removal electrodes: Non-analytical electrodes, including HEOL and HEOR, were removed.

Band-pass filtering: A 1–30 Hz band-pass filter was applied to retain primary EEG signals.

Down sampled: The sampling rate was reduced from 500 Hz to 250 Hz to improve computational efficiency.

Extraction epoch: EEG data corresponding to MI phases (marked as “2”) were extracted, resulting in 40 segments (Fig. 2b), including 20 left-hand MI segments (80 s) and 20 right-hand MI segments (80 s), for subsequent analysis.

Independent Component Analysis (ICA): ICA was applied to identify and remove artifacts caused by eye, cardiac, and muscle activity. Non-brain components were manually excluded where possible.

Remove bad epoch: after ICA, we removed the remaining severely artifact-contaminated segments based on experience and the thresholding method (voltage amplitude exceeding ± 100 µV).

Average reference: EEG data were re-referenced to achieve a zero-mean spatial distribution, aiding standardization and reducing individual variability.

Finally, 60 s of continuous EEG data for both left and right-hand MI were used for microstate analysis.

EEG microstate analysis

We used the EEGLAB-based microstate analysis toolbox (Microstate1.0) [19] and conducted the analysis following five key steps(Fig. 2d):

(1) Global field power (GFP) Calculation: GFP was computed for each participant by evaluating the potential values of all electrode channels at a given time. GFP serves as an indicator of the consistency of signals across all electrodes at any given moment and is defined by the following formula:

|

where  represents each electrode,

represents each electrode,  denotes the number of electrodes, and

denotes the number of electrodes, and  is the measured voltage at each channel.

is the measured voltage at each channel.

During the GFP peak extraction, the minimum peak distance was set to 30 ms, the maximum number of peaks to 20,000, and the GFP threshold to 0.

-

(2)

Microstate segmentation: EEG signals were segmented into short intervals based on GFP values, with each interval representing a microstate. Microstate are brief, stable patterns of brain activity that typically last for tens of milliseconds. The convergence threshold is 1e-06 during the segmentation process.

(3) Microstate clustering: We initially set the possible cluster numbers between 3 and 8 and used both the Cross-Validation (CV) criterion [14] and the Global Explained Variance (GEV) method to determine the optimal cluster number. When the number of clusters was 4, the CV curve stabilized, and based on the GEV evaluation, the fit of the clustering results improved significantly. The GEV value for 4 clusters exceeded 70%, which confirmed that 4 was the optimal number of microstate. Subsequently, after randomly selecting four initial scalp topographies as the starting cluster centers, the program performs clustering analysis on all scalp topographies using a modified k-means clustering algorithm. During the clustering process, the algorithm iteratively adjusts the initial cluster centers to maximize the similarity within clusters and the difference between clusters. This process is repeated until the final cluster centers accurately represent the main EEG activity patterns in the dataset, which are referred to as “Template topographic”. Based on all subjects’“Template topographic”, a second-level clustering was conducted using the modified k-means algorithm, resulting in four group-level topographic maps, which were labeled as microstate A, B, C, and D.

(4) Microstate fitting and labeling: The four template topographic were matched with the raw EEG data using spatial correlation. Each time point in the raw data was labeled as the microstate with the highest spatial correlation. This process enabled tracking of brain topography dynamics over time and facilitated extraction of temporal microstate parameters.

(5) Key microstate features extracted: (a) Duration: The average time each microstate remains stable before transitioning to another state. This metric reflects the stability of specific neural components. (b) Occurrence: The average number of times each microstate appears per second, indicating the activation frequency of underlying neural generators. (c) Coverage: The proportion of time each microstate occupies during the analysis period, reflecting its temporal dominance relative to other neural generators. (d) Transition Probability (TP): The likelihood of one microstate transitioning to another. For example, the probability of transitioning from microstate A to B is calculated as the ratio of transitions from A to B to the total transitions from A to all other microstate. This metric reflects the sequential activation patterns of neural networks [13].

Machine learning classification

To evaluate whether EEG microstate parameters can distinguish between left and right-hand MI tasks in acute stroke patients, significant microstate features were selected and sent to machine learning models for classification. Three models were used: Linear Discriminant Analysis(LDA) [20], Support Vector Machines(SVM) [21], and K-Nearest Neighbors(KNN) [22]. We used MATLAB’s fitcdiscr, fitcsvm, and fitcknn functions to train the LDA, SVM, and KNN classifiers, respectively. For the LDA classifier, we selected the linear discriminant type and set the gamma parameter to 0. Additionally, coefficient filling was disabled to prevent overfitting. For the SVM classifier, we chose a linear kernel function and kept the other parameters at their default settings, such as the kernel scale set to ‘auto’. For the KNN classifier, we selected the Euclidean distance metric and set the number of neighbors to 10. Feature standardization was enabled for both the SVM and KNN classifiers to ensure all features were on the same scale, thereby improving classification performance.

Classification performance was assessed using 10-fold cross-validation with multiple metrics, including accuracy (ACC), precision (PRE), sensitivity (SEN), specificity (SPE), F1 score (F1), and the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC). Meanwhile, the performance of the three classifiers was statistically compared using the McNemar test. Finally, Fisher discriminant analysis was employed to rank the microstate features that showed significant differences between left and right-hand MI, in order to evaluate the contribution of each feature to the classification task.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses in this study were conducted using SPSS 19. The normality of the data was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test, and all variables met or approximately met the assumption of normal distribution. Differences in EEG microstate parameters between left and right-hand MI were analyzed using two-tailed paired-sample t-tests, with the significance level set at 0.05. To control the false discovery rate (fdr) due to multiple comparisons, P-values were adjusted using fdr correction. An adjusted P-value (Pfdr) less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant, indicating significant differences in microstate parameters between left and right-hand MI tasks.

Result

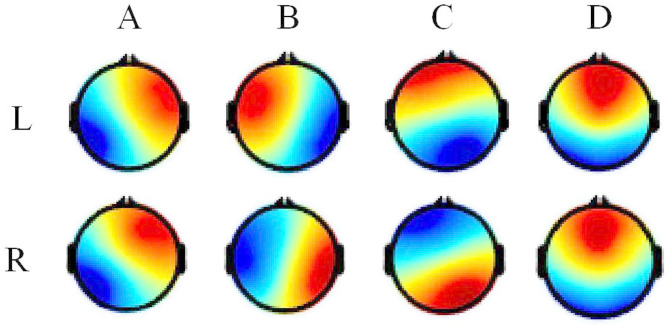

EEG microstate topographic

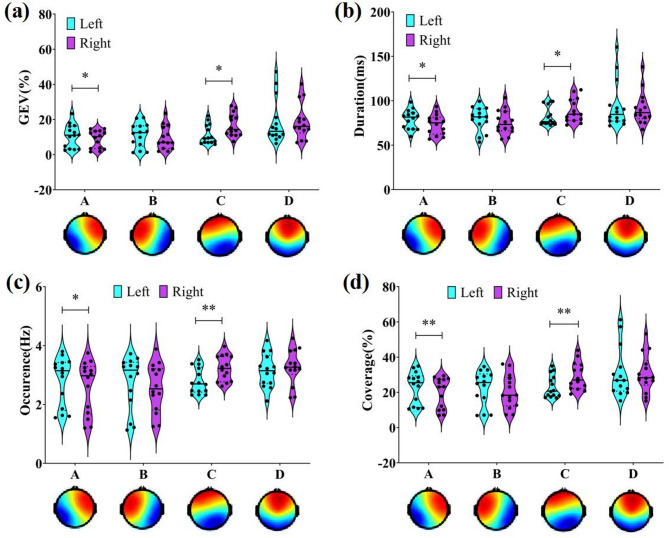

Topographic Analysis of Variance (TANOVA) was performed using the Ragu toolbox to examine statistical differences in microstate topographies during left and right-hand MI tasks [23]. No significant differences were found between the two groups (Fig. 3). To assess the explanatory power of microstate topographies for raw EEG data, GEV was calculated. Results showed that for left-hand MI, GEV of microstate A was significantly higher (Cohen’s d = 0.735, Pfdr=0.034), while GEV of microstate C was significantly lower compared to the right-hand MI (Cohen’s d=-0.996, Pfdr=0.012) (Fig. 4a).

Fig. 3.

Topography of EEG microstate at left and right-hand MI. “L” represents the left-hand MI, “R” represents the right-hand MI

Fig. 4.

EEG microstate GEV, Duration, Occurrence and Coverage at left and right-hand MI. (a) GEV, (b) Duration, (c) Occurrence, (d) Coverage

EEG microstate Temporal parameters

Temporal parameters of EEG microstate, including Duration, Occurrence, Coverage, and TP, were extracted to explore brain network dynamics during left and right-hand MI tasks. Results showed similar trends for Duration, Occurrence, and Coverage: microstate A parameters were significantly higher during left-hand MI, while microstate C parameters were significantly lower compare to right-hand (Fig. 4b, c, d) (Table 2). No significant differences were observed for microstate B and D. Regarding TP, microstate B to A and D to A transitions were significantly higher for left-hand MI, whereas microstate D to C transitions were significantly lower compare to right-hand (Fig. 5b, d) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of EEG microstate Temporal parameters with significant differences between left and right-hand MI in acute stroke patients

| Mean ± sd | Cohen’s d | P fdr | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Left | Right | |||

| Duration(ms) | ||||

| A | 79.04 ± 10.96 | 73.20 ± 11.44 | 0.84 | 0.032 |

| C | 82.60 ± 10.85 | 88.93 ± 13.33 | -0.70 | 0.044 |

| Occurrence(Hz) | ||||

| A | 2.80 ± 0.82 | 2.59 ± 0.89 | 0.82 | 0.018 |

| C | 2.79 ± 0.44 | 3.23 ± 0.43 | -1.14 | 0.004 |

| Coverage(%) | ||||

| A | 22.85 ± 9.02 | 19.75 ± 8.70 | 1.16 | 0.004 |

| C | 23.35 ± 6.41 | 29.18 ± 7.82 | -1.03 | 0.004 |

| TP(%) | ||||

| B→A | 32.15 ± 12.62 | 29.09 ± 14.51 | 0.82 | 0.04 |

| D→A | 34.24 ± 9.58 | 27.79 ± 8.21 | 1.25 | < 0.001 |

| D→C | 34.28 ± 15.04 | 43.85 ± 15.29 | -1.22 | 0.006 |

Fig. 5.

TP of EEG microstate at left and right-hand MI. (a) A to others, (b) B to others, (c) C to others, and (d) D to others

Machine learning classification

Based on the above analysis, temporal parameters of EEG microstate during left and right-hand MI tasks were obtained. To evaluate their discriminative ability, parameters with significant differences between the two groups were input into machine learning models, including LDA, SVM, and KNN. As shown in Fig. 6; Table 3, the classification accuracies for LDA, SVM, and KNN were 60.71 ± 3.63%, 60.71 ± 6.59%, and 75.00 ± 7.94%, respectively. Notably, the KNN model achieved the highest classification accuracy. Through conducting McNemar tests for the three pairs of classifiers (LDA & SVM, LDA & KNN, SVM & KNN), it was found that all computed χ² values were less than the critical value of 3.841. This indicates that, at the 0.05 significance level, there were no significant performance differences between the three classifiers (Table 4).

Fig. 6.

Machine learning classification results. (a) confusion matrix of the LDA model, (b) confusion matrix of the SVM model, (c) confusion matrix of the KNN model, and (d) the ROC curve of the three machine learning models. “L” indicates left-hand MI, “R” indicates right-hand MI

Table 3.

Classification performance of tree, SVM and KNN models based on EEG microstate Temporal parameters

| ML | ACC(%) | PRE(%) | SEN (%) | SPE (%) | F1 (%) | AUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LDA | 60.71 ± 3.63 | 60.00 ± 5.17 | 64.29 ± 3.92 | 57.14 ± 6.09 | 62.07 ± 5.08 | 0.6582 ± 0.0578 |

| SVM | 60.71 ± 6.59 | 61.54 ± 3.75 | 57.14 ± 6.66 | 64.29 ± 3.07 | 59.26 ± 4.57 | 0.7398 ± 0.0781 |

| KNN | 75.00 ± 7.94 | 68.42 ± 4.49 | 92.86 ± 3.37 | 57.14 ± 4.09 | 78.79 ± 6.88 | 0.6607 ± 0.0411 |

Table 4.

Performance differences between classifiers based on the McNemar test

| Classifier Pair | χ 2 | df | Significance Level (Critical Value) |

|---|---|---|---|

| LDA & SVM | 0.0909 | 1 | 3.841 (0.05) |

| LDA & KNN | 3.571 | 1 | 3.841 (0.05) |

| SVM & KNN | 3.571 | 1 | 3.841 (0.05) |

Fisher analysis

We employed Fisher discriminant analysis to rank the microstate features that showed significant differences between left and right-hand MI tasks, in order to assess each feature’s contribution to classification. The Fisher scores, from highest to lowest, were as follows: Occurrence-C (0.53), Coverage-C (0.33), D→A transition (0.26), D→C transition (0.20), Duration-C (0.14), Duration-A (0.14), Coverage-A (0.06), Occurrence-A (0.029), and B→A transition (0.025). The results are illustrated in Fig. 7. These findings indicate that the Occurrence of microstate C are the most important features for distinguishing between left and right-hand MI tasks.

Fig. 7.

Feature importance ranking based on Fisher analysis Occurrence-C represents the Occurrence of microstate C, D→A represents the TP from microstate D to A, and so on

Discussion

This study is the first to reveal significant differences in the temporal parameters of microstate A and C during left and right-hand MI tasks in acute stroke patients. Specifically, microstate A showed significantly higher Duration, Occurrence, and Coverage during left-hand MI compared to right-hand MI, while microstate C demonstrated significantly elevated parameters during right-hand MI. Based on Fisher analysis, it was found that the Occurrence of microstate C is the most important feature for distinguishing between the left and right-hand MI tasks in acute patients. These distinct microstate distributions between the two tasks may reflect a lateralized activation mechanism of brain networks involved in MI regulation.

Previous studies have demonstrated that microstate A is closely associated with the auditory network (AN), which plays a critical role in task-related attention allocation and sensory information processing [24, 25]. The significant enhancement of microstate A during left-hand MI suggests that patients rely more heavily on AN involvement to focus attention and facilitate MI regulation. The participants in this study were predominantly right-hand MI, requiring right-hemispheric motor cortex activation for left-hand MI, along with interhemispheric communication via the corpus callosum to integrate signals from the auditory and motor networks [26]. Enhanced auditory network activity may improve the efficiency of this interhemispheric coordination. Additionally, acute stroke patients may experience reduced motor network functionality due to damage and potentially compensate for the loss by recruiting other networks, such as the auditory network, to complete left-hand MI tasks [27]. Our findings are consistent with those of Liu et al. [16], who reported that microstate 3 (microstate A) parameters were higher during left-hand MI than right-hand MI in healthy individuals, supporting our observations.

Microstate C is strongly associated with the Default Mode Network (DMN) [28], which is typically activated during introspection, thought processing, and scenario imagination [29]. The significant increase in microstate C during the right-hand MI task may indicate greater reliance on the DMN in stroke patients. In right-handed individuals, right-hand motor control is predominantly governed by the left motor cortex [30]. After a stroke, the functionality of the right motor network may be impaired, while the left motor network remains partially functional. Consequently, right-hand MI is more likely to activate task-related DMN regions to facilitate task regulation. Another plausible explanation is that right-hand MI in right-handed patients may rely more on scenario-based task simulation, such as visualizing the detailed actions of grasping an object with the right hand. The DMN plays a critical role in processing such scenario-based information [29], leading to a significant increase in microstate C. At the same time, the increase in microstate C may also represent pathological overactivation of the DMN. After brain injury, the DMN may become excessively involved in regulating motor tasks, which is a manifestation of the brain attempting to compensate for impaired motor network functions. However, this overactivation may also reflect a suboptimal allocation of neural resources, suggesting potential abnormalities in neuroplasticity or insufficient functional reorganization. Unlike Liu et al., we observed significant differences in microstate C parameters between left and right-hand MI, which were not present in their study. This suggests that the microstate C abnormalities identified in our acute stroke patients are likely disease-specific features rather than general features of MI.

We utilized significantly different parameters of microstate A and C to construct machine learning models for distinguishing left and right-hand MI. The results showed that the KNN model achieved the highest classification accuracy of 75.00%, outperforming both LDA and SVM. The superior performance of the KNN model may be attributed to its greater adaptability to small sample sizes. Compared to previous studies on stroke patients, our classification accuracy demonstrated a slight improvement. Benzy et al. achieved a classification accuracy of 74.44% in distinguishing left and right-hand MI tasks in stroke patients using a Naive Bayes Classifier (NBC) based on EEG PLV features [31]. Similarly, Gangadharan K et al. utilized a PLV-based EEG epochs selection algorithm and achieved a classification accuracy of 74.4% with an LDA model [32]. The relatively limited classification accuracy in this study may be attributed to the small sample size, which restricts the generalization performance of the models. Additionally, the high heterogeneity of EEG data among stroke patients, such as variations in lesion location and severity, could also impact classification performance.

Although the study revealed the features and classification performance of EEG microstate in patients with acute stroke during left and right-hand MI tasks, there are still some limitations. Firstly, the small sample size, coupled with the fact that the data comes from a single dataset, may affect the generalization ability of the machine learning model. Secondly, the enrolled acute stroke patients were mostly male, and the gender imbalance may have influenced the results [33]. In the future, we need to expand the sample size, balance the gender ratio. Finally, differences in lesion location and medication status among the included patients may introduce heterogeneity, which could limit the generalizability of the findings. Future studies should consider using more homogeneous samples to validate and further extend the conclusions of this study.

Conclusion

This study is the first to investigate the differences in EEG microstate features during left and right-hand MI tasks in acute stroke patients and to validate the effectiveness of these microstate features in classifying left and right-hand MI. The results demonstrated significant differences in the temporal parameters and TP of microstate A and C, indicating that the brain network dynamics of left and right-hand MI in acute stroke patients exhibit distinct features. Furthermore, the KNN classification model, based on significantly different microstate parameters, achieved high classification accuracy, further supporting the utility of microstate features in MI tasks. These findings not only deepen our understanding of post-stroke brain network reorganization but also provide theoretical foundations and practical guidance for optimizing BCI system design.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Liu et al. for providing the original database (https://www.nature.com/articles/s41597-023-02787-8.).

Author contributions

LS, RX, and XM wrote the original manuscript. ZY, PT, ZX, ZZ, YY, and GZ made guided revisions to the original manuscript.

Funding

(1) Innovative Research Team (in Science and Technology) in University of Henan Province (No. 24IRTSTHN042). (2) the Major Science and Technology Projects of Henan Province (No. 221100310500). (3) the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82201709,82302298). (4) the Science and Technology Research Project of Henan Province (No. 242102310055, 242102310005). (5) the Open Project Program of Henan Collaborative Innovation Center of Prevention and Treatment of Mental Disorder (No. XTkf01, XTkf07). (6) International Science and Technology Cooperation Project of Henan Province (No.242102521012).

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Shiyang Lv and Xiangying Ran contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Yi Yu, Email: yuyi@xxmu.edu.cn.

Zhixian Gao, Email: gaozhixian@xxmu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Feigin VL et al. Jan., World Stroke Organization (WSO): Global Stroke Fact Sheet 2022, Int J Stroke, vol. 17, no. 1, pp. 18–29, 2022, 10.1177/17474930211065917 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Feigin VL, et al. Global, regional, and National burden of stroke and its risk factors, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet Neurol. Oct. 2021;20(10):795–820. 10.1016/S1474-4422(21)00252-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Xu F, et al. A transfer learning framework based on motor imagery rehabilitation for stroke. Sci Rep. Oct. 2021;11(1):19783. 10.1038/s41598-021-99114-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Duan X, Xie S, Xie X, Obermayer K, Cui Y, Wang Z. An online data visualization feedback protocol for motor Imagery-Based BCI training. Front Hum Neurosci. 2021;15:625983. 10.3389/fnhum.2021.625983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Min B-K, Marzelli MJ, Yoo S-S. Neuroimaging-based approaches in the brain-computer interface. Trends Biotechnol. Nov. 2010;28(11):552–60. 10.1016/j.tibtech.2010.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Salahuddin U, Gao P-X. Signal generation, acquisition, and processing in brain machine interfaces: A unified review. Front Neurosci. 2021;15:728178. 10.3389/fnins.2021.728178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chatterjee R, Bandyopadhyay T. EEG Based Motor Imagery Classification Using SVM and MLP, in 2016 2nd International Conference on Computational Intelligence and Networks (CINE), Jan. 2016, pp. 84–89. 10.1109/CINE.2016.22

- 8.Wang J, Chen Y-H, Yang J, Sawan M. Intelligent classification technique of hand motor imagery using EEG Beta rebound Follow-Up pattern. Biosens (Basel). Jun. 2022;12(6):384. 10.3390/bios12060384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Wang L, Xu G, Yang S, Wang J, Guo M, Yan W. Motor Imagery BCI Research Based on Sample Entropy and SVM, in 2012 Sixth International Conference on Electromagnetic Field Problems and Applications, Jun. 2012, pp. 1–4. 10.1109/ICEF.2012.6310370

- 10.Lakshminarayanan K, et al. Evaluation of EEG oscillatory patterns and classification of compound limb tactile imagery. Brain Sci. Apr. 2023;13(4):656. 10.3390/brainsci13040656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Blanco-Mora DA, Aldridge A, Jorge C, Vourvopoulos A, Figueiredo P, Bermúdez S, Badia I. Impact of age, VR, immersion, and spatial resolution on classifier performance for a MI-based BCI, Brain-Computer Interfaces, vol. 9, no. 3, pp. 169–178, Jul. 2022, 10.1080/2326263X.2022.2054606

- 12.Zhao Z, et al. Causal link between prefrontal cortex and EEG microstates: evidence from patients with prefrontal lesion. Front Neurosci. 2023;17:1306120. 10.3389/fnins.2023.1306120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gao Z, et al. Visual feedback gain modulates the activation of Task-Related networks and the suppression of Non-Task networks during precise grasping. IEEE Trans Neural Syst Rehabil Eng. 2024;32:2873–82. 10.1109/TNSRE.2024.3438674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhao Z et al. Dec., Common and differential EEG microstate of major depressive disorder patients with and without response to rTMS treatment, J Affect Disord, vol. 367, pp. 777–787, 2024, 10.1016/j.jad.2024.09.040 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Ren H, et al. Abnormal nonlinear features of EEG microstate sequence in obsessive-compulsive disorder. BMC Psychiatry. Dec. 2024;24(1):881. 10.1186/s12888-024-06334-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Liu W, Liu X, Dai R, Tang X. Exploring differences between left and right hand motor imagery via spatio-temporal EEG microstate, Comput Assist Surg (Abingdon), vol. 22, no. sup1, pp. 258–266, Dec. 2017, 10.1080/24699322.2017.1389404 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Cui Y, Xie S, Fu Y, Xie X. Predicting Motor Imagery BCI Performance Based on EEG Microstate Analysis, Brain Sci, vol. 13, no. 9, p. 1288, Sep. 2023, 10.3390/brainsci13091288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Liu H, et al. An EEG motor imagery dataset for brain computer interface in acute stroke patients. Sci Data. Jan. 2024;11(1):131. 10.1038/s41597-023-02787-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Nagabhushan Kalburgi S, Kleinert T, Aryan D, Nash K, Schiller B, Koenig T. MICROSTATELAB: The EEGLAB Toolbox for Resting-State Microstate Analysis, Brain Topogr, vol. 37, no. 4, pp. 621–645, Jul. 2024, 10.1007/s10548-023-01003-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Dos Santos EM, San-Martin R, Fraga FJ. Comparison of subject-independent and subject-specific EEG-based BCI using LDA and SVM classifiers, Med Biol Eng Comput, vol. 61, no. 3, pp. 835–845, Mar. 2023, 10.1007/s11517-023-02769-3 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Fan D et al. Aug., Multimodal ischemic stroke recurrence prediction model based on the capsule neural network and support vector machine, Medicine (Baltimore), vol. 103, no. 35, p. e39217, 2024, 10.1097/MD.0000000000039217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Zhang S, Li X, Zong M, Zhu X, Wang R. Efficient kNN classification with different numbers of nearest neighbors. IEEE Trans Neural Netw Learn Syst. May 2018;29(5):1774–85. 10.1109/TNNLS.2017.2673241. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Koenig T, Kottlow M, Stein M, Melie-García L. Ragu: a free tool for the analysis of EEG and MEG event-related scalp field data using global randomization statistics. Comput Intell Neurosci. 2011;2011:938925. 10.1155/2011/938925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bréchet L, Brunet D, Birot G, Gruetter R, Michel CM, Jorge J. Capturing the spatiotemporal dynamics of self-generated, task-initiated thoughts with EEG and fMRI, Neuroimage, vol. 194, pp. 82–92, Jul. 2019, 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2019.03.029 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Payne L, Rogers CS, Wingfield A, Sekuler R. A right-ear bias of auditory selective attention is evident in alpha oscillations, Psychophysiology, vol. 54, no. 4, pp. 528–535, Apr. 2017, 10.1111/psyp.12815 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Bundy DT, Leuthardt EC. The Cortical Physiology of Ipsilateral Limb Movements, Trends Neurosci, vol. 42, no. 11, pp. 825–839, Nov. 2019, 10.1016/j.tins.2019.08.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Wang H et al. Feb., Motor network reorganization after motor imagery training in stroke patients with moderate to severe upper limb impairment, CNS Neurosci Ther, vol. 29, no. 2, pp. 619–632, 2023, 10.1111/cns.14065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Al Zoubi O, et al. Canonical EEG microstates transitions reflect switching among BOLD resting state networks and predict fMRI signal. J Neural Eng. Jan. 2022;18(6). 10.1088/1741-2552/ac4595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Menon V. 20 years of the default mode network: A review and synthesis. Neuron. Aug. 2023;111(16):2469–87. 10.1016/j.neuron.2023.04.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Ocklenburg S, Guo ZV. Cross-hemispheric communication: insights on lateralized brain functions. Neuron. Apr. 2024;112(8):1222–34. 10.1016/j.neuron.2024.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Benzy VK, Vinod AP, Subasree R, Alladi S, Raghavendra K. Motor Imagery Hand Movement Direction Decoding Using Brain Computer Interface to Aid Stroke Recovery and Rehabilitation, IEEE Trans Neural Syst Rehabil Eng, vol. 28, no. 12, pp. 3051–3062, Dec. 2020, 10.1109/TNSRE.2020.3039331 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.K SG, Vinod AP, Subasree R. A Phase-based EEG Epoch Selection Method for Decoding Bi-directional Hand Movement Imagination in Stroke Patients, Annu Int Conf IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc, vol. 2023, pp. 1–4, Jul. 2023. 10.1109/EMBC40787.2023.10340319 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Niu Y, et al. A gender recognition method based on EEG microstates. Comput Biol Med. May 2024;173:108366. 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2024.108366. [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.