Abstract

Background

Teenage pregnancy remains a pressing public health issue with profound effects on health, education, and socio-economic outcomes. Rural areas, such as parts of Teso, often face higher prevalence of teenage pregnancy due to socioeconomic challenges. This study aimed at determining the prevalence of teenage pregnancy and associated factors in Atutur sub-county, Kumi district.

Methodology

The authors employed a cross-sectional study design and sampled 444 teenage girls aged 13–19 years from 12 randomly selected villages in Atutur sub-county, Kumi district in April 2024. They were interviewed using structured researcher administered questionnaire. Data was collected using kobo collect tool, downloaded, cleaned and exported to SPPS version 27.0 for further management and analysis. Descriptive statistics was conducted to determine the prevalence of teenage pregnancy. After adjusting for covariates, multivariate analysis was conducted using modified Poisson regression to determine predictors of teenage pregnancy. Results were reported with a 95% confidence interval (CI) and factors whose CI did not contain a null (1.0), with p-value (P < 0.05) for adjusted PR, were considered statistically significant.

Results

Of the 444 teenage girls, the mean age was 17 (standard deviation = 1.9) years. About one third of the participants, 132(29.7%) had ever conceived. Teenage girls in cohabitation were 3.0 times more likely to have conceived (aPR = 3.0, 95% CI: 2.23–4.10, P < 0.001) compared to those staying with their parents. Teenagers with both parents deceased were 1.9 times more likely to conceive (aPR = 1.9, 95% CI: 1.15–3.31, P = 0.032) compared to those whose parents were both alive. Teenage girls who were not satisfied with basic needs provided by parents were 3.3 times more likely to conceive (aPR = 3.3, 95% CI: 2.26–4.85, P < 0.001) compared to those satisfied with the basic needs provided by their parents.

Conclusion

Teenage pregnancy rates in Atutur sub-county Kumi district was higher than the national average, due to adverse socio-economic situation. Strengthening parental support of the girl child, with legal and community measures to reduce early marriages in rural settings may reduce teenage pregnancy. There is need to make deliberate efforts to provide socio-economic strengthening for the teenage girls to reduce their vulnerability.

Keywords: Teenage pregnancy, Prevalence, Cross-sectional, Early marriage

Introduction

The world Health organization (WHO) defines teenage pregnancy as a pregnancy carried by a female aged 10–19 years [26]. The current figures of teenage pregnancy are still high at 15% globally with about 23 million teenage girls becoming pregnant annually and almost half of which are unintended (49%) [21, 23] and over 2 million pregnancies occurring in girls less than 15 years [23]. Unfortunately, only 16 million are able to deliver each year and this constitute 11% of all births globally [6] with majority taking place in developing countries [7]. The remaining 7 million pregnancies are unaccounted for as they end up with unsafe abortions, thus posing serious life threatening and financial implications on the teenagers, their communities and countries at large [1].

The greatest burden of teenage pregnancy is in the sub-Saharan African region (SSA), with approximately 13 million girls delivering their first baby by 18 years [21]. Still in the SSA, there is significant variation across countries with the lowest prevalence recorded in South African countries ranging from 2.3% to 19.2%. In the East Africa, Rwanda has lowest rate at 5%, Kenya with 15.3%, Tanzania at 23% and highest reported in Uganda at 25% where about 1,000 teenage pregnancies are reported daily [15, 19]. This high teenage pregnancy in Uganda is attributed to the very high prevalence of early marriages, with Uganda ranking only 16th of the 25 countries globally having the highest rates of early child marriages [22].

The trends of teenage pregnancy in the country initially declined in the early 2000’s from 31 to 25% in 2006, after which it remained relatively stable at 25% up to 2022 [15, 24, 25]. Recent studies have indicated an exponential rise in teenage pregnancies through the years 2019–2021 attributable to the COVID 19 pandemic and its associated lockdown that left many young girls vulnerable [10].

Teenage pregnancy thrives amidst stringent international, regional and local legislative frameworks aimed at protecting children’s rights. Evolution of these legal processes emanate all the way from the Convention on the elimination of all forms of discrimination against women in 1985 through African Union campaign to end child marriage in 2015 [20] as well as the interventions of local policies by Ministries of gender and Education such as the National Strategy for Girls’ Education (NSGE) in Uganda (2015–2019) and Girls not Brides [18]. All these were aimed at curbing early child marriage and pregnancy. Other initiatives include establishment of youth friendly services and improved contraceptive accessibility in hospitals plus introduction of sexual and reproductive health education in schools.

Even with existence of such interventions, teenage pregnancy has continued to entrench itself in Teso sub region and Uganda at large. The objective of this study was therefore to assess the prevalence of teenage pregnancy in the rural settings and the associated factors. This will help design tailored interventions to reduce teenage pregnancy and contribute to the elimination of health and socio-economic related impacts in the region.

Methods and materials

Study design and setting

A community-based cross-sectional study was conducted in April 2024 to determine the prevalence of teenage pregnancy and establish the underlying factors associated with it in the rural settings of Uganda. The study was conducted in Atutur sub-county, Kumi District. However much there are varying reports of teenage pregnancy rates in Teso from 31% in 2016 [13] to 16% in 2022 [14] and 21% in 2024 [9], Kumi is still among the districts in Teso with a high prevalence of teenage pregnancy at above 20% [9]. The study aimed at determining the actual prevalence and associated factors in the rural settings of Atutur sub-county.

Besides, a study which had been conducted in Pakwach district, Northern Uganda showed a significant increase in teenage pregnancy in rural settings after the COVID-19 lockdowns [2]. Kumi district is bordered by Katakwi, Nakapiripirit, Bukedea, Pallisa and Ngora districts in the north, northeast, east, south and west respectively. It is 54 km by road, southeast of the sub region’s city, Soroti and about 240 km from Kampala, Uganda’s capital city. The district has a population of 287,275 with main economic activities being farming, and small businesses in the many trading centers and municipality [16]. Kumi district is along the great Northern corridor route from Mombasa to Sudan, and it is a resting place for long distance truck drivers.

Study population, inclusion and exclusion criteria

The study was conducted among adolescent girls aged 13–19 years in twelve (12) randomly selected villages of Atutur sub-county. Adolescent girls aged 18 to 19 years and emancipated minors who were able and willing consented. Those between 13 to 17 years and not emancipated assented after which their parents or guardians had provided parental consent. Girls who had impaired mental judgement, too sick, in pain, girls below 18 years whose parents or guardians declined to provide informed consent and those with prior teenage pregnancies but outside the age category at the time of the study were excluded from the study.

Sample size determination and participant recruitment

Yamane formula (1967) was used to determine the sample size. At 95% confidence interval and the precision error margin of 5% (level of significance), using the district teenage girl population of 11.5% of the district general female population, a sample size of 390 was obtained. After adjusting the sample size by 10% for non-response rate, 444 participants were recruited from the 12 randomly selected villages of the 24 villages of Atutur sub-county, giving an average of 37 participants per village. Village Health Team (VHT) leaders in respective villages led the researchers to the households with teenage girls. We worked with VHTs in this process because they are often the first line contacts of most of the households and it was presumed, they know individual households by their occupants. Consecutive recruitment of the teenage girls from the identified households was done until the allocated sample size per village was reached.

Study variables

The dependent primary variable was prevalence of teenage pregnancy measured as the proportions of teenage girls being currently pregnant or ever conceived irrespective of the outcome. Independent variables included participant demographics such as current age, Religion, current occupation/work, age of first penetrative coitus, living with male partner, being an orphan, use of alcohol and other substances of abuse, among others. Family, Social and Cultural factors such as violence by parents at home, parents’ financial dependency, large family sizes, socio cultural norms, and parents’ levels of educations. Program and Health system factors such as provision of sexual education at schools, the distance to the nearest facility, receipt of health education talks, and access to contraceptives.

Data collection procedures

A researcher administered questionnaire was used to obtain primary data from study participants. The questionnaire was developed with checks and quality control measures to reduce instances of missing variables and then uploaded on an android tablet and entered into an online survey tool, the kobo toolbox (https://ee.kobotoolbox.org/x/GY3LZRj9) for ease of data collection and management. The research assistants were trained on online data collection with kobo toolbox and the ethical processes in the conduct of research involving minors. A pilot study was done in which a test re-test reliability study on 20 teenage girls in the neighboring district of Bukedea with similar population characteristics was done within a one-week interval and a reliability co-efficient value, r was 0.95.

Data management and analysis

The online data was checked for completeness for every participant at the end of the data collection process. Participants found to be missing key variables were dropped to allow for enrollment of new participants. The data was then downloaded from the online system and exported to Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) software program version 27.0 for further management and analysis.

Descriptive data was summarized and reported as means, standard deviations, frequencies, and proportions and presented as texts, tables, charts and graphs. At the bivariate level, Chi-square independent test was used to test the association between background characteristics and teenage pregnancy; at 95% confidence interval. Modified Poisson regression analysis was conducted at multivariate level to determine the factors associated with teenage pregnancy. A P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents

Majority 75.2% (334/444) of the respondents were aged 16–19 years, about 55.9% (248/444) had primary education, with a majority 70.9% (315/444) in school. About 66.4% (295/444) of the respondents were middle born with both parents alive 83.3% (370/444). About 67.8% (301/444) of the respondents were staying with both parents who were married 77.9% (346/444) (Table 1) 0.3.2

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents

| Variable | Number, N = 444 | Proportions, %age | Teenage pregnancy, n (%) | Test statistics X2 Value | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age CAT/years | |||||

| 13–15 | 110 | 24.8 | 0(0.0) | ||

| 16–19 | 334 | 75.2 | 132(39.5) | ||

| Education Level | |||||

| No formal education | 2 | 0.5 | 0(0.0) | 8.3 | 0.027 |

| Primary | 247 | 55.6 | 86(34.8) | ||

| Secondary | 184 | 41.4 | 42(22.8) | ||

| Tertiary | 11 | 2.5 | 4(36.4) | ||

| Religion | |||||

| Anglican | 154 | 34.7 | 58(37.7) | 18.5 | 0.001 |

| Pentecostal | 93 | 20.9 | 20(21.5) | ||

| Muslims | 51 | 11.5 | 5(9.8) | ||

| Catholics | 132 | 29.7 | 45(34.1) | ||

| Others | 14 | 3.2 | 4(28.6) | ||

| Occupation | |||||

| Unemployed | 109 | 24.5 | 88(80.7) | 207.3 | 0.000 |

| Student | 315 | 70.9 | 31(9.8) | ||

| Employed | 20 | 4.5 | 13(65.0) | ||

| Birth order | |||||

| Lastborn | 41 | 9.2 | 10(24.4) | 1.7 | 0.419 |

| Others | 295 | 66.4 | 85(28.8) | ||

| First born | 108 | 24.3 | 37(34.3) | ||

| Stays with | |||||

| Parents | 301 | 67.8 | 59(19.6) | 128.8 | 0.000 |

| Relatives | 71 | 16 | 12(16.9) | ||

| Friends/alone | 8 | 1.8 | 4(50.0) | ||

| Partner | 64 | 14.4 | 56(87.5) | ||

| Orphan status | |||||

| Both alive | 370 | 83.3 | 99(26.8) | 16.6 | 0.001 |

| Only father alive | 15 | 3.4 | 5(33.3) | ||

| Only mother alive | 48 | 10.8 | 19(39.6) | ||

| Both diseased | 11 | 2.5 | 9(81.8) | ||

| Parents Marital Status | |||||

| Traditionally married | 303 | 68.2 | 84(27.7) | 5.1 | 0.274 |

| Divorced | 45 | 10.1 | 15(33.3) | ||

| Wedded | 43 | 9.7 | 11(25.6) | ||

| Unmarried | 29 | 6.5 | 11(37.9) | ||

| Others | 24 | 5.4 | 11(45.8) | ||

The prevalence of teenage pregnancy

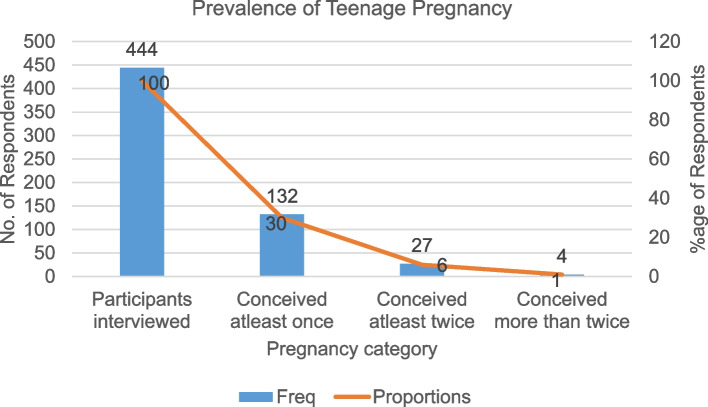

Among the respondents in this study, 29.7% (132/444) had ever conceived at least one time, about 6.1% (27/444) conceived twice and 0.9% (4/444) conceived more than 2 times (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

The prevalence of teenage pregnancy

Factors associated with teenage pregnancy

After adjusting for covariates, the multivariate analysis revealed that staying with a male partner, being an orphan and being unsatisfied with basic needs provided by parents were factors that were significantly associated with teenage pregnancy.

Teenage girls who stay with male partners were 3.0 times more likely to conceive (aPR = 3.0, 95% CI: 2.23–4.10, P < 0.001) compared to those staying with their parents.

Teenage girls with both parents deceased were 1.9 times more likely to conceive (aPR = 1.9, 95% CI: 1.15–3.31, P = 0.032) compared to those whose parents were both alive.

Teenage girls who were not satisfied with basic needs provided by parents were 3.3 times more likely to conceive (aPR = 3.3, 95% CI: 2.26–4.85, P < 0.001) compared to those satisfied with the basic needs (Table 2).

Table 2.

Multivariable analysis of factors associated with teenage pregnancy

| Variable | Teenage pregnancy | Crude PR (95% CI) | Adjusted PR (95% CI) | P-Value for aPR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n = 132) n (%) | No (n = 312) n (%) | ||||

| Highest Level of Education | |||||

| Primary/No education | 86(34.7) | 162(65.3) | 1 | 1 | |

| Post Primary | 46(23.5) | 150(76.5) | 0.7 (0.49–0.92) | 0.9(0.72–1.26) | 0.729 |

| School Enrolment status | |||||

| In school | 82(26.0) | 233(74.0) | 1 | 1 | |

| Out school | 50(38.8) | 79(61.2) | 1.5 (1.12–1.98) | 1.1(0.76–1.46) | 0.768 |

| No. of sexual partners | |||||

| None | 48(25.4) | 141(74.6) | 1 | 1 | |

| One partner | 32(24.2) | 100(75.8) | 0.9(0.65–1.41) | 0.9(0.66–1.35) | 0.750 |

| Two partners and more | 52(36.6) | 71(57.7) | 1.7(1.21–2.29) | 1.2(0.82–1.78) | 0.330 |

| Stays with | |||||

| Parents | 59(19.6) | 242(80.4) | 1 | 1 | |

| Partner | 56(87.5) | 8(12.5) | 4.5(3.49–5.71) | 3.0(2.23–4.10) | 0.000 |

| Relatives, friends or alone | 17(21.5) | 62(78.5) | 1.1(0.68–1.77) | 0.8(0.52–1.31) | 0.416 |

| Orphan Status | |||||

| Both a live | 99(26.8) | 271(73.2) | 1 | 1 | |

| One deceased | 24(38.1) | 39(61.9) | 1.4(0.99–2.04) | 0.9(0.57–1.28) | 0.434 |

| Both deceased | 9(81.8) | 2(18.2) | 3.1(2.21–4.24) | 1.9(1.15–3.31) | 0.013 |

| Satisfied with basic needs provided by parents | |||||

| Yes | 24(11.5) | 184(88.5) | 1 | 1 | |

| No | 108(45.8) | 128(54.2) | 3.9(2.66–5.92) | 3.3(2.26–4.85) | 0.000 |

| Drunkard Parents | |||||

| No | 90(33.1) | 182(66.9) | 1 | 1 | |

| Yes | 42(24.4) | 130(75.6) | 0.7(0.54–1.01) | 0.7(0.54–1.94) | 0.058 |

| Sexual education at home | |||||

| No | 57(33.3) | 114(66.7) | 1 | 1 | |

| Yes | 75(27.5) | 198(72.5) | 0.8(0.62–1.09) | 0.9(0.77–1.26) | 0.909 |

| Peer pressure to get pregnant | |||||

| No | 100(26.9) | 272(73.1) | 1 | 1 | |

| Yes | 32(44.4) | 40(55.6) | 1.7(1.22–2.25) | 1.2(0.83–1.61) | 0.400 |

| Religious support to the use of contraceptives | |||||

| No | 117(30.5) | 267(69.5) | 1 | 1 | |

| Yes | 15(25.0) | 45(75.0) | 0.8(0.52–1.30) | 0.7(0.49–1.06) | 0.098 |

*p < 0.05 indicates significant variables, PR is the Prevalence Rate Ratio, aPR is the adjusted Prevalence Rate Ratio. All variables were adjusted for each other

Discussion

The aim of our study was to determine the prevalence and the predictors of teenage pregnancy in the rural settings of Uganda. Our findings revealed that in Atutur sub-county, about 3 in 10 teenage girls had ever been pregnant, which is way above the national average of 25% [17, 25]. Studies in other parts of Uganda which have found teenage pregnancy to be higher than the national average include; a study in Hoima district which found the prevalence at 30% among in-school teenage girls [10] and another at 41% among teenage girls in Palabek refugee settlement [11]. These are much higher than in our study, probably due to the vulnerable nature of girls in refugee settlements. However, a study conducted in Northern Uganda reported a low prevalence of teenage pregnancy at 2.8%. This figure may be underestimated, as the study focused only on current pregnancies, and some adolescents who were aware of their pregnancy status might have declined to participate [12]. Teenage pregnancy prevalence in other countries of SSA such as Ethiopia are estimated to be 23.6% [7], slightly lower than the Ugandan average. In a multi-country analysis of SSA, Congo expressed the highest teenage pregnancy prevalence rate at 44% while Rwanda was the lowest at 7.2% [1], with the overall prevalence being high at 25% in high fertility SSA countries [3].

Our findings revealed the following factors as predictors of teenage pregnancy; staying with a male partner, being a total orphan and not being satisfied with parents’ provisions of basic needs.

In our study, teenage girls who stay with male partners were thrice more likely to have ever conceived compared to those staying with their parents. Teenage girls staying with male partners are those who are victims of early marriages and this facilitates their early pregnancy. Teenage girls staying with their male partners exposes them to routine unplanned and unprotected sexual behaviors which predisposes them to unintended pregnancies [1, 3, 7]. Staying with male partners also exposes the teenage girls to peer pressure of conceiving and becoming mothers [4, 27].

Teenage girls who were total orphans (both parents diseased) in our study were about twice as likely to have conceived compared to those whose parents were both alive. In absence of their parents, these girls fall victims to crafty men who promise gifts and money [5]. This is also true for girls who are not satisfied with the basic needs provided by their parents. Once parents fail to provide, the children will devise strategies to have their needs met [8]. Economic challenges and loss of parents push girls into early relationships and eventual pregnancies. Consequently, as a means to find a solution to their financial needs, some girls take on petty trade, others transactional sex as personal survival strategies [5].

Families need to plan and have a manageable number of children to ensure adequate social and financial support, more especially in ensuring that they meet all their basic needs and keep them in schools. In addition, there is need to sensitize the community on the dangers of early marriages and teenage pregnancy and advocate for girl child education as a means of mitigating the risks associated with teenage pregnancy.

Study strengths and limitations

Our study had a high response rate which improved the credibility of the findings. In addition, the study included all the self-reported cases of teenage pregnancies, which we think gives an actual reflection of the problem. On the other hand, being a cross-sectional study conducted during school days; some potential respondents could have been missed, more so those in boarding schools as the researchers did not go to education institutions. There was potential reporting desirability bias as the prevalence of teenage pregnancy was based on self-reports of the adolescent girls rather than recommended screening modalities. In addition, the narrow geographic scope of this study limits its generalizability.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the Department of Public Health, School of Health Sciences, Soroti University for the guidance throughout the process of proposal development, data collection and report writing. We also wish to acknowledge Dr.Sarah Asio, the Medical Superintendent of Atutur Hospital for her mentorship and guidance while we were for our placement and data collection.

Authors’ contributions

M.A, J.K, M.C, H.M, N.M.C, J.P.M Conceptualization, proposal development, data collection, analysis and report writing RO; Proposal development, supervision, data analysis and report writing. BO; Report writing, original and review HA; Proposal development and supervision ME; Data analysis and report writing SK; Proposal development, supervision and review.

Funding

There was no funding for this study.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This was a student led research project and as such the proposal was presented to the Department of Public Health, School of Health Sciences of Soroti University for review and approval and later submitted to Mbale Regional Referral Hospital Research and Ethics Committee (MRRHREC), which reviewed and granted ethical approval, REC No. MRRH-2024–405, as required by the Declaration of Helsinki (2013). Administrative clearance to conduct the study was sought and obtained from Kumi District Health Office.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Participant recruitment process

Participants were recruited from the 12 randomly selected villages of the 24 villages of Atutur sub-county. Consecutive recruitment of the teenage girls from the identified households was done until the allocated sample size per village was reached.

Informed consent procedures

In accordance with recommendations from Belmont Report (1979), written informed consent was sought from participants who were of consenting age (18 years and above) and emancipated minors (those girls below 18 years but already living with a male partner, heading a household or breastfeeding a baby) while assent of the non-emancipated minors and their parental informed consent was obtained prior to interviewing.

Confidentiality and privacy measures

Confidentiality was upheld by administering questionnaires in a secure place and personal identifiers such as name, national identification number or phone contacts were excluded. The computerized data was kept secure by pass-wording and encrypting it only to be accessible to the authorized study team.

Voluntary participation

The participants were informed of their free will to withdraw from the study at any point without any penalty.

Compensation

There was no compensation for the study participants as the research did not have any funding.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Ahinkorah BO, Kang M, Perry L, Brooks F, Hayen A. Prevalence of first adolescent pregnancy and its associated factors in sub-Saharan Africa: A multi-country analysis. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(2 February):1–16. 10.1371/journal.pone.0246308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alunyo JP, Mukunya D, Napyo A, Matovu JKB, Okia D, Benon W, Okello F, Tuwa AH, Wenani D, Okibure A, Omara G, Olupot PO. Effect of COVID ‑ 19 lock down on teenage pregnancies in Northern Uganda : an interrupted time series analysis. Reprod Health. (2023);1–6. 10.1186/s12978-023-01707-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Asmamaw DB, Tafere TZ, Negash WD. Prevalence of teenage pregnancy and its associated factors in high fertility sub-Saharan Africa countries: a multilevel analysis. BMC Women’s Health. 2023;23(1):1–10. 10.1186/s12905-023-02169-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ayele BG, Gebregzabher TG, Hailu TT, Assefa BA. Determinants of teenage pregnancy in degua tembien district, Tigray, Northern Ethiopia: A community-based case-control study. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(7):1–15. 10.1371/journal.pone.0200898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kabwigu S, Nsibirano R. Determinants of adolescent pregnancy in Luuka District, Eastern Uganda: a mixed methods study. Texila Int J Public Health. 2022;10(2):1–16. 10.21522/TIJPH.2013.10.02.Art007. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kassa BG, Belay HG, Ayele AD. Teenage pregnancy and its associated factors among teenage females in Farta woreda, Northwest, Ethiopia, 2020: A community-based cross-sectional study. Population Med. 2021;3:1–8. 10.18332/popmed/139190. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mamo K, Siyoum M, Birhanu A. Teenage pregnancy and associated factors in Ethiopia : a systematic review and meta-analysis Teenage pregnancy and associated factors in Ethiopia. Int J Adolesc Youth. 2021;26(1):501–12. 10.1080/02673843.2021.2010577. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Manzi F, Ogwang J, Akankwatsa A, Wokali OC, Obba F, Bumba A, Nekaka R, Gavamukulya Y. Factors associated with teenage pregnancy and its effects in Kibuku. J Prim Health Care. 2018;8(2). 10.4172/2167-1079.1000298.

- 9.Ministry of Health. Annual Health Sector Report. (2024). 2023/2024.

- 10.Musinguzi M, Kumakech E, Auma AG, Akello RA, Kigongo E, Tumwesigye R, Opio B, Kabunga A, Omech B. Prevalence and correlates of teenage pregnancy among in-school teenagers during the COVID-19 pandemic in Hoima district western Uganda-A cross sectional community-based study. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(12 December):1–16. 10.1371/journal.pone.0278772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Okello EO, Musinguzi M, Opollo MS, Eustes K, Akello AR. Factors associated with teenage pregnancy among refugees in Palabek refugee settlement , Northern Uganda. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2024. 10.1186/s12884-024-06909-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Okot C, Laker F, Apio PO, Madraa G, Kibone W, Pebolo FP, Bongomin F, Okot C, Laker F, Apio PO, Madraa G, Kibone W, Pebolo FP, Bongomin F, Okot C, Laker F, Apio PO, Madraa G, Kibone W, Bongomin F. Prevalence of teenage pregnancy and associated based survey prevalence of teenage pregnancy and associated factors in agago district , uganda : a community-based surveyprevalence of teenage pregnancy and associated based survey prevalence of teenage pregnancy and associated factors in Agago District , Uganda : a community-based survey. 2023. 10.2147/AHMT.S414275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.UDHS. Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS) and ICF. 2018. Uganda Demographic and Health Survey 2016. Kampala, Uganda and Rockville: UBOS and ICF. Udhs. 2016;625. www.DHSprogram.com.

- 14.UDHS. Uganda Bureau of Statistcs 2023. Uganda Demographic and Health Survey. 2022;2022.

- 15.Uganda Bureau of Statistics(UBOS). Uganda demographic and health survey ( UDHS ) 2022 EXTENSION. 2023.

- 16.Uganda Bureau of Statistics(UBOS). National Population and Housing Census 2024: Preliminary Results. 2024.

- 17.Uganda Bureau of Statistics(UBOS) and ICF. Uganda Demographic and Health Survey 2016. Udhs. 2016;625.

- 18.Uganda Ministry of Gender Labour and Social Development. The national strategy to end child marriage and teenage pregnancy. 2022.

- 19.Uganda Ministry of Health. Annual Health Sector Performance Report. 2016.

- 20.United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). Review of the African Union campaign to end child marriage. 2018.

- 21.United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). Protecting child rights in a time of crises. UNICEF Annual Report 2021. 2021.

- 22.United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). UNICEF Innocenti-Global office of research and foresight: Annual Report 2023. 2024.

- 23.United Nations Populations Fund. Girlhood, not motherhood: Preventing adolescent pregnancy. In United Nations Popuplations Fund. 2015. https://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/Girlhood_not_motherhood_final_web.pdf.

- 24.United Nations Populations Fund. Uganda fact sheet on teenage pregnancy. 2021;2021.

- 25.Wasswa R, Kabagenyi A, Kananura RM, Jehopio J, Rutaremwa G. Determinants of change in the inequality and associated predictors of teenage pregnancy in Uganda for the period 2006 – 2016 : analysis of the Uganda Demographic and Health Surveys. 2021;1–13. 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-053264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.World Health Orgnaization. Adolescent Pregnancy. Key facts: World Health Organization; 2024. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yakubu I. Determinants of adolescent pregnancy in sub-Saharan Africa : a systematic review. 2018. 10.1186/s12978-018-0460-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.