ABSTRACT

Objective:

This trial evaluated the effectiveness of a joint health coach and dietitian lifestyle clinic led by a family physician for overweight and obese adults in lowering body mass index (BMI) and improving waist circumference (WC) measurement among overweight and obese individuals.

Design and Setting:

The study was a 6-month, parallel, open-label, clustered, randomized trial with control involving four primary health care centers in Hail City.

Participants:

Of the 300 healthy adult volunteers screened, 198 met the inclusion criteria and completed the study. Participants were randomized into four clusters and assigned to either the intervention or control group.

Intervention:

A structured dietary, physical exercise, behavioral, and cognitive lifestyle intervention provided by a joint health coach and dietitian clinic led by a family physician.

Primary Measures:

The primary outcomes were reductions in BMI, improvements in WC distribution, and weight loss differences from baseline to 6 months, with a target of 5% weight loss.

Results:

A significant reduction in BMI in the intervention arm (mean BMI intervention before = 36.74, mean BMI intervention after = 33.82, mean difference = 2.91, P < 0.001) compared to the control (routine care) arm is evident. Additionally, the intervention group had notable improvements in WC measurements; however, it is not statistically significant.

Conclusion:

The joint lifestyle clinic run by a health coach and a dietitian and led by a family physician is effective in reducing BMI and improving WC measurement. The trial was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov under the identification number NCT05654337 and did not receive specific funding.

Keywords: Body mass index, cluster trial, comparative study, intervention program, obesity, waist circumference

Introduction

The global burden of overweight and obesity is overwhelming as over 3 million people die every year.[1,2] As a result, there is an urgent need for innovative, context-oriented, and effective approaches to obesity health services organized and led by family physicians in primary care worldwide.

The escalating trend of obesity is a major concern in the Gulf Cooperation Countries, particularly in Saudi Arabia, as it significantly contributes to the epidemic of various chronic diseases and cancers.[3,4,5,6]

In Saudi Arabia, particularly in the Hail region, there is a high prevalence of overweight and obesity, pointing to the importance of tackling the problem from different dimensions. The potential association with this high prevalence is linked to various factors related to the context, such as dietary habits, large family size, physical exercise, and maternal employment.[7,8]

A new policy from the Saudi Ministry of Health recommends a 6-month lifestyle modification intervention program that limits the number and criteria of obese people who are eligible for bariatric surgery. Obese individuals were forced by this new policy to consider a dietary, exercise, behavioral change, and cognitive lifestyle modification intervention program as a first-line therapy and possible course of action.[9,10,11]

In Saudi Arabia, interdisciplinary and economically viable initiatives aimed at preventing noncommunicable illnesses are the primary concern of policymakers in the health system. This is accomplished by promoting exercise, helping people quit smoking, and offering dietary advice.[12]

The last updated clinical practice guideline for the nonpharmacological management of overweight and obese Saudi adults strongly suggests lifestyle intervention rather than usual care alone, individualized counseling interventions rather than a generic educational pamphlet, physical activity rather than no physical activity, and physical activity in addition to diet rather than diet alone.[13]

Many countries have implemented taxes on unprocessed sugar or sugar-added foods to reduce their consumption and prevent obesity and other adverse health events. However, there is no concrete evidence of the effectiveness of the intervention on the ground.[14]

Mobile intervention technologies like pedometers or accelerometers with displays, activity trackers, smartphones, or tablets have a great effect on supporting sustainable health behavior, increasing physical activity, and preventing the risk of chronic disease.[15,16,17]

Body mass index (BMI) and waist circumference (WC) are the two vital signs requested to be considered in clinical practice.[18] Despite the presence of efficient antiobesity medications such as semaglutide 2.4 and other modalities for weight loss in the clinical setting, like dietary counseling and health coaching.,[19,20] planning an established clinic-based weight reduction program requires paying attention to different barriers to the retention of patients in the program.[21]

Inspiring insights from previous studies and field-expert opinions, this clustered trial is aimed at estimating the effectiveness of the obesity pathway intervention utilizing an innovative, practical, and context-oriented approach: the joint health coach and dietitian clinic led by a family physician in reducing BMI and WC compared to routine care for individuals with overweight and obesity at primary health care centers.

Research questions

To what extent is the application of the joint life-style clinic led by a family physician for overweight and obese adults implemented at primary health care centers effective in achieving a reduction in the BMI in the intervention clusters compared to the control clusters?

To what extent is the application of a joint health coach and dietitian lifestyle clinic led by a family physician for overweight and obese adults implemented at primary health care clinics effective in achieving improvement in the WC in the intervention clusters compared to the control clusters?

General objective

To investigate the effectiveness of a joint health coach and dietitian lifestyle clinic led by a family physician in reducing BMI and improving measurements of WC compared to routine care for individuals with overweight and obesity at primary health care centers.

Specific objectives

Aim 1: To identify the difference in the proportion of BMI reduction among overweight and obese adults between clusters receiving the intervention and those in the control clusters (receiving routine care) at primary healthcare centers.

Aim 2: To examine the differences in the changes in WC proportion among overweight and obese adults between clusters receiving the intervention and those in the control clusters (receiving routine care) at primary health care centers.

Research methods

A 6-month, parallel, open-label, clustered, randomized trial was done to see how well an obesity pathway intervention using a joint lifestyle clinic led by a family physician lowered BMI and improved measurements of WC compared to regular care at primary health care centers for people who are overweight or obese. The trial registered under the identifier NCT05654337.

Study participants

Healthy Saudi adult participants of both genders, who were obese or overweight, were assessed by family physicians at the start (baseline) to collect baseline data about BMI and WC. A similar report on BMI and WC was obtained for each participant at 6 months from the beginning of the trial.

Intervention

Family physicians at primary care centers lead the process of preparation of a weight reduction schedule provided for overweight and obese patients by a joint effort of a certified health coach and registered dietician working inside the lifestyle clinic. The family physician at the primary care center identifies eligible individuals in the first encounter. Then she/he coordinates with a health coach and dietitian for a suitable intervention and plan for follow-up, assessment, and reporting the results. The outcome of the intervention was compared to that of the control clusters that received routine care, which included health education and information related to diet and physical exercise for weight reduction without any plan or framed instructions tailored to obesity reduction.

Outcomes

The primary outcome for Aim 1 is the difference in the proportion of reduction in BMI between the intervention and control clusters aiming for a >5% reduction from baseline.

The primary outcome for Aim 2 is the difference in the measurement of WC between the intervention and control clusters aiming for a >5% reduction in WC from the baseline.

Sample size

A sample of 440 participants for the two trial arms with an average cluster sample (m) of about 11 participants per cluster is calculated using the STATA clustersampsi command; this is done by specifying the total number of clusters (k) = 20, the mean for sample 1 (mu1) = 0.6, the mean for sample 2 (mu2) = 0.31, and the intraclass correlation coefficient (rho) = 0.01 at a power beta of 0.8 and a significant alpha level of 0.05.

Randomization

The randomization was held centrally by the research investigators, and the selected health centers were identified before the starting date of the trial using random number generator software available at https://www.random.org/. Each trial cluster is composed of two health centers.

The selected centers were maintained throughout the trial, and no changes were allowed.

Data analysis

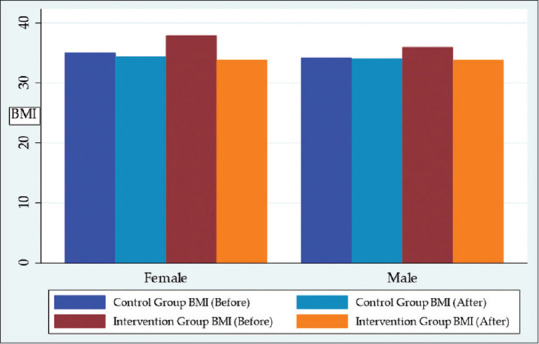

Primary outcomes were analyzed using a paired T-test to compare the mean BMI between the intervention and control arms. Also, a pictorial analysis, a bar chart, was generated to help support the result of the test [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Comparison of BMI between intervention and control arms

Results

Participants

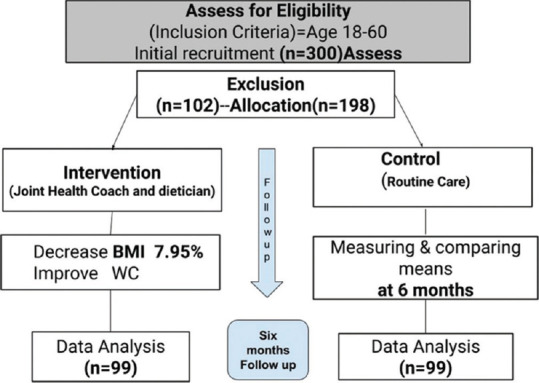

Recruitment began in December 2023, and the last participant completed in June 2024. A total of 300 participants, free of chronic disease, in the age range of 18–60 with overweight and various grades of obesity, were recruited, with 198 meeting the inclusion criteria and completing the study. Randomization of 4 clusters to either the intervention or control group was held centrally before recruitment using a random number generator. The intervention arm involved connecting participants from two clusters to a comprehensive program that included the expertise of a certified health coach and a registered dietitian, providing an integrated, comprehensive, planned, and patient-centered follow-up and assessment program for weight reduction and continuous support for 6 months. The control arm includes participants in the other two clusters with similar criteria receiving routine care for overweight and obesity. The main outcome measures were a 5% reduction in BMI and improvements in WC in the clusters that received the intervention in comparison to the clusters with routine care. The allocation of clusters for the intervention arm was made by the central team, and the allocation was based on the cluster level [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Client flow and recruitment

Primary outcomes

In this study, we examined the effects of the joint health coach and dietitian lifestyle clinic led by family physicians on BMI and WC among clients with overweight and obesity in the two trial arms: the intervention clusters and the control clusters at primary care centers. Paired t-tests were conducted to compare the variables before and after the intervention in each cluster arm. Chi-square test followed by Fisher exact test was also conducted to investigate the difference in the distribution of WC measurements among males and females’ groups. The mean age of participants in both the intervention and control arms is 32 years.

A total of four clusters were randomized to receive either the intervention or routine care at the start of the study; two clusters per arm were identified, and 99 participants for each arm successfully completed the study, Figure 2.

Paired T-test results showed a significant reduction in BMI in the intervention arm (mean BMI_interven. before = 36.74, mean BMI_interven. after = 33.82, mean difference = 2.91, P < 0.001) compared to the control (routine care) arm, with a reduction of approximately 7.95% in the mean BMI as reflected in Table 1. No significant changes in BMI were observed in the control arm (mean BMI control before = 34.54, mean BMI control after = 34.22, mean difference = 0.318, P = 0.6292) as shown in Table 2.

Table 1.

Paired t-test Results for Body-Mass Index in the Intervention Arm (Before and After)

| Variable | Obs | Mean | Std.Err. | Std.Dev. | {95% Conf.Interval |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMI interven. before | 99 | 36.74 | 0.5755 | 5.73 | 35.59 – 37.88 |

| BMI interven. after | 99 | 33.82 | 0.534 | 5.31 | 32.76 – 34.88 |

| Diff | 99 | 2.91 | 0.819 | 8.15 | 1.286-4.535 |

| Mean (diff)=mean (BMI interven. before -BMI interven. after) | t=3.556 | ||||

| H0: mean (diff)=0 | Degrees of freedom=98 | ||||

| Ha: mean (diff)<0 | Ha: mean (diff)!=0 | Ha: mean > (diff) > 0 | |||

| Pr (T<t)=0.9997 | Pr ( |T| >|t|)=0.0006 | Pr (T>t > )=0.0003 | |||

Table 2.

Paired t-test Results for Body-Mass Index in the Control Arm (Before and After)

| Variable | Obs | Mean | Std.Err. | Std.Dev. | {95% Conf.Interval |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMI control before | 99 | 34.54 | 0.845 | 8.41 | 32.86 –336.22 |

| BMI control after | 99 | 34.22 | 0.469 | 4.66 | 33.29 – 35.15 |

| Diff | 99 | 0.318 | 0.964 | 9.595 | -1.595 – 2.233 |

| Mean (diff)=mean (BMI control before -BMI control after) | t=0.0.331 | ||||

| H0: mean (diff)=0 | Degrees of freedom=98 | ||||

| Ha: mean (diff)<0 | Ha: mean (diff)!=0 | Ha: mean > (diff) > 0 | |||

| Pr (T<t)=0.6292 | Pr ( |T| >|t|)=0.7415 | Pr (T>t > )=0.3708 | |||

Chi-square test showed no statistically significant association or change in the WC in the intervention and control arms before and after intervention. The distribution analyses revealed notable changes in the measurements of WC in the intervention arm, Table 3 and Table 4.

Table 3.

Frequency Distribution Results for Waist Circumference Measurement by Sex in the Intervention Arm (Before)

| Risk and % | High Risk | Moderate Risk | Normal Wight | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Female | 14 | 42.42 | 19 | 57.57 | 0 | 0 | 33 | 100 |

| Male | 44 | 74.14 | 14 | 24.14 | 1 | 1.72 | 59 | 100 |

| Total | 58 | 63.04 | 33 | 35.86 | 1 | 1.09 | 92 | 100 |

Table 4.

Frequency Distribution Results for Waist Circumference Measurement by Sex in the Intervention Arm (After)

| Risk and % | High Risk | Moderate Risk | Normal Wight | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Female | 8 | 20.51 | 17 | 54.24 | 14 | 35.89 | 39 | 100 |

| Male | 10 | 16.95 | 14 | 24.14 | 18 | 28.81 | 60 | 100 |

| Total | 18 | 18.18 | 49 | 49.49 | 32 | 32.32 | 99 | 100 |

Chi-square and Fisher exact tests for male and female distribution of risk in the intervention arm: Pearson chi2 (4)=6.0000 P=0.199. Fisher’s exact=1.000

Discussion

This trial aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of the obesity pathway intervention composed of a joint health coach and dietitian lifestyle clinic led by a family physician clinic program in the primary care centers in reducing BMI and improving WC in overweight and obese adults in the intervention clusters in comparison to the clusters in the control arm (receiving routine care).

The mean age of 32 years for participants indicates the compliance of youth and young adults with the planned intervention. This result reflects the effectiveness and convenience of the intervention in the context, and it is coherent with other studies.[22,23]

The significant reduction in the mean BMI in the intervention arm over 6 months as a result of implementing a joint health coach and dietitian lifestyle clinic led by family physician, as reflected in Table 1, is a strong indicator of the success of the joint clinic program. This reduction in the mean BMI is 7.95%, which is equivalent to a significant weight loss.[24] The results of this study are consistent with those of earlier studies, demonstrating the necessity and value of the interdisciplinary approach for weight loss intervention at the primary care level.[25,26]

This finding confirms that the joint efforts exerted by the health coach and dietitian and led by family physicians at primary care in the Saudi context had a positive effect in reducing BMI among the group of participants in the intervention arm.

In contrast, the control arm did not show any significant change in the BMI before and after the intervention, as depicted in Table 2. These results indicate that the intervention had a specific impact on reducing BMI among participants in the intervention arm, while the participants in the control arm did not experience any significant changes.

This result is consistent with results from other studies about the role of personalized dietary intervention, physical exercise, structured lifestyle modification, and health provider support programs in reducing BMI among overweight and obese people.[27,28,29,30]

Waist circumference

The frequency distribution of WC measurements among participants in the intervention arm revealed that 42.42% of females and 74.14% of males were classified as having a BMI in the high-risk category at the beginning of the study and before the start of the intervention as reflected in Table 3.

After 6 months of follow-up with a joint health coach and dietitian lifestyle clinic led by family physician intervention, the proportion of females in the high-risk category decreased to 20.51%, and for males, it decreased to 16.95%, as shown in Table 4. Although the finding is not statistically significant (P value = 0.199), these results suggest that the intervention had a positive effect in reducing the overall risk level of morbid obesity by reducing the proportion of individuals with high-risk WCs in both sexes. This result is coherent with other research findings that revealed reduced WC with aerobic exercise or a combined effect of exercise and a low-carbohydrate ketogenic dietary intervention.[31,32,33]

In the control arm, the frequency distribution of the measurements of WC showed that 21.63% of females and 18.64% of males were classified as high-risk at the beginning of the study and before the start of the intervention [Table 5]. After the intervention, the proportion of females in the high-risk category remained relatively stable at 21.63%, while for males, it increased slightly to 27%, as reflected in Table 6. Although the result is statistically not significant (P value = 0.199), these distributions indicate that the intervention did not show improvement in WC among the participants in the control arm.

Table 5.

Frequency Distribution Results for Waist Circumference Measurement by Sex in the Control Arm (Before)

| Risk and % | High Risk | Moderate Risk | Normal Wight | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Female | 8 | 21.63 | 29 | 78.38 | 0 | 0 | 37 | 100 |

| Male | 12 | 18.64 | 32 | 81.36 | 0 | 0 | 60 | 100 |

| Total | 20 | 20.62 | 77 | 79.38 | 0 | 0 | 97 | 100 |

Table 6.

Frequency Distribution Results for Waist Circumference Measurement by Sex in the Control Arm (After)

| Risk and % | High Risk | Moderate Risk | Normal Wight | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Female | 9 | 21.63 | 28 | 78.38 | 0 | 0 | 37 | 100 |

| Male | 27 | 18.64 | 33 | 81.36 | 0 | 0 | 60 | 100 |

| Total | 36 | 37.11 | 61 | 62.89 | 0 | 0 | 97 | 100 |

Chi-square, and Fisher exact tests for male and female distribution of risk in the control arm: Pearson chi2 (4)=6.0000 P=0.199. Fisher’s exact=1.000

Overall effect of the intervention

The results indicate that the joint health coach and dietitian lifestyle clinic led by family physician intervention had a significant effect in reducing BMI and WC among the participant group in the intervention arm. Although not statistically significant, the frequency distribution results further support the positive impact of the intervention in reducing the proportion of individuals at high risk for WC, particularly in the intervention arm. However, the control arm did not experience any significant changes in BMI or WC, highlighting the effectiveness of the joint health coach and dietitian lifestyle clinic led by family physician intervention in reducing BMI and improving WC measurements among participants at primary care centers.

These findings emphasize the importance and the benefit of targeted interventions and interventions tailored to specific risk factors, such as BMI and WC. Future research should explore further organization and improvement of a family physician-led lifestyle clinic model at primary care and the long-term effects of such interventions.

Finally, the results of this study support the effectiveness of the intervention in reducing BMI and WC in the intervention clusters, which includes a joint effort of the health coach and dietician led by family physicians at primary care. These findings are consistent with those from other studies.[34,35,36,37] Furthermore, this finding contributes to the existing body of knowledge on interventions targeting weight-related health risks and provides valuable insights for designing future interventions and weight management programs aimed at improving overall health, reducing the prevalence of overweight and obesity, and improving the adoption of an innovative, integrated, context-oriented, and healthy lifestyle intervention. These trial findings are applicable and could be generalized to another similar context in Saudi Arabia and the Gulf region.

Strength and limitations

One of the strengths of this study is the pragmatic study design and the innovative joint program reflecting a real-world experience of cooperation led by family physicians and shared by both health coaches and dietitians at the primary care level, which takes a snapshot of the Saudi context. One drawback is that the trial was carried out in a rural area, which may not be convenient for people who live in big cities. This is because it is easier to adopt the suggested diet and regular exercise in rural areas than in metropolitan ones. In addition, unlike the densely populated parts of large towns like Riyad and Jeddah, the rural area has both walking trails and open, green spaces. The study’s short duration, which does not provide adequate time for all findings, is another drawback.

Implications for practice

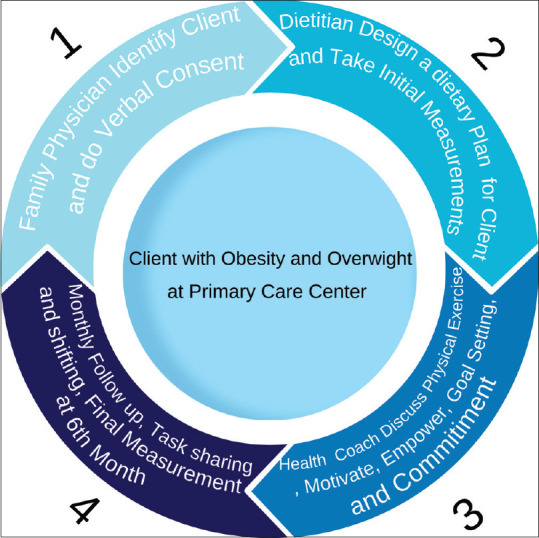

The joint lifestyle clinic led by a family physician at primary care, involving a health coach and a dietitian, is a collaborative effort aimed at supporting clients with overweight and obesity to comply with the provided service. The clinic led by a family physician, operated by a health coach and a dietitian, was established specifically for individuals in the intervention arm of the study and maintained for a period of 6 months [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

Client flow inside the lifestyle clinic

The process begins after identification of the client by the family physician at clinic visit; the dietitian designs a suitable dietary plan after obtaining initial consent from the client. The dietary plan may include the preparation of diets and the development of meals and diets according to what is appropriate to the references or the client, taking into account the client’s budget and food preferences.

Once the plan is established, the client is referred to the health coach for preparation and empowerment sessions as well as scheduling follow-up appointments at their convenience. For the sake of retaining and best serving the client, both the dietician and health coach were prepared for task-shifting and task-sharing roles in the event of each other’s look busy or absence during the client visit.

The role of the health coach involves the following key steps:

Goal Setting: The client articulates his or her weight loss goal, such as aiming to lose a specific amount of weight within a defined timeframe.

Determining Strategies: Together with the health coach, the client identifies the necessary steps to achieve his or her goal, which may include changes to dietary habits or increasing physical activity as per the dietitian’s plan.

Providing Assistance: The health coach supports the client in creating a timeline for each step toward their goal, whether related to diet or exercise.

Scheduling Appointments: The health coach helps the client determine the frequency and spacing of follow-up appointments to monitor progress and adherence to the goal.

In the empowerment and counseling sessions, the health coach aims to:

Motivate Continued Effort: Encourage the client to persist with their weight loss efforts according to the prepared plan.

Draw Inspiration: Help the client find motivation from past successful weight loss experiences.

Identify and Overcome Obstacles: Discuss potential barriers to implementing the plan and explore solutions or alternatives.

The health coach may refer the client back to consult the dietitian for advice on various aspects of a healthy lifestyle, such as:

Reducing sugary drink intake; ensuring adequate sleep; educating on healthy lifestyle practices; explaining healthy meal preparation; monitoring food intake and weight changes; providing tailored dietary plans based on individual factors like height, weight, age, and activity level; and educating on daily fluid requirements.

This collaborative approach between the health coach and dietitian led by family physicians at primary care centers ensures comprehensive support for clients in complying with and adopting and maintaining the newly learned healthier habits to manage their weight effectively.

Conclusions

The findings of this trial demonstrate the value and effectiveness of the joint health coach and dietitian lifestyle clinic led by family physicians in reducing BMI and improving WC measurements in the intervention arm compared to the control arm. These results highlight the importance of comprehensive and valuable lifestyle interventions achieved by this joint clinic program. Further research is required to explore the long-term effects of such interventions with a fully supported and well-organized staff clinic to develop tailored strategies for obesity management.

Recommendations

The joint health coach and dietitian lifestyle clinic led by family physicians will change the health coach and dietician’s existing competitive perspective to a collaborative, cooperative, and more productive one that will improve the services they deliver to the overweight and obese clients seeking health care.

Together with each other, dieticians and health coaches led by a family physician at primary care should plan and execute a regular combined training course that will help them collaborate successfully in the future.

Expanding the number of health centers that participate in the joint health coach and dietitian lifestyle clinic led by family physicians is a worthwhile goal that may yield new insights on the management of obesity at the primary care level.

Although participant perception of the intervention was not among the study objectives, future research could explore participants’ motivation and compliance, providing further insight into the intervention’s effectiveness.

Trial Registration: The trial was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov under the identifier NCT05654337.

Link: https://classic.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/results/NCT05654337?view=results.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board in the Hail region.

Informed consent

Written informed consent was obtained from each client in each cluster immediately after randomization but before the participant underwent any study intervention or data collection procedures. The informed consent was obtained by the family physician at the primary healthcare center in a special room at the health center. The family physician provided information about the trial and also ensured that the participant understood the information. This was achieved by adequately answering the questions raised by participants. Additionally, the participants were encouraged to ask questions about the trial. They were allowed adequate time to decide voluntarily whether to participate or not in the trial. If a participant needed more time to decide, then the primary healthcare physician gave the participant another appointment.

The contents of the informed consent included the following elements:

Information about the study, including the purpose of the trial: Obesity pathway intervention among overweight and obese adults led by family physicians at a primary care center.

The description of the study procedures: The intervention would be a joint lifestyle intervention clinic schedule provided by a certified health coach and registered dietitian and led by family physician.

The description of the risks: There were no risks as the intervention was prevention and counseling.

The description of the benefits included free medical check-ups for BMI and counseling during the trial.

Participation was voluntary, and the participant could withdraw at any time during the trial without penalty.

The institution and investigator maintained the confidentiality of the records and data by saving them on a personal computer with a password accessible only to the concerned research team members. The records and data were used for trial purposes and were not disclosed under any circumstances to any person or for any reason.

The name, address, and phone number of the principal investigator were clearly written in the consent form.

The informed consent was written in simple Arabic with the avoidance of technical or medical terms to facilitate apprehension by the participants.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Funding Statement

Nil.

References

- 1.Ryan D, Barquera S, Barata Cavalcanti O, Ralston J. Handbook of Global Health. Springer; 2021. The global pandemic of overweight and obesity: Addressing a twenty-first century multifactorial disease; pp. 73–739. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alsulami S, Baig M, Ahmad T, Althagafi N, Hazzazi E, Alsayed R, et al. Obesity prevalence, physical activity, and dietary practices among adults in Saudi Arabia. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1124051. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1124051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alanazi J, Unnisa A, Patel R, Itumalla R, Alanazi M, Alharby T, et al. Prevalence of cardiovascular disease and osteoarthritis in obese population of Hail region, Saudi Arabia. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2022;26:7161–8. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_202210_29903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Althumiri N, Basyouni M, AlMousa N, AlJuwaysim M, Almubark R, BinDhim N, et al. Obesity in Saudi Arabia in 2020: Prevalence, distribution, and its current association with various health conditions. Healthcare. 2021;9:311. doi: 10.3390/healthcare9030311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alreshidi F, Alreshidi F, Ahmed H. An insight into the prevalence rates of obesity and its related risk factors among the Saudi community in the Hai'l Region. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2022;26:5755–62. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_202208_29512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Al Hammadi H, Reilly J. Prevalence of obesity among school-age children and adolescents in the Gulf cooperation council (GCC) states: A systematic review. BMC Obes. 2019;6:1–10. doi: 10.1186/s40608-018-0221-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alazzeh AY, AlShammari EM, Smadi MM, Azzeh FS, AlShammari BT, Epuru S, et al. Some socioeconomic factors and lifestyle habits influencing the prevalence of obesity among adolescent male students in the Hail Region of Saudi Arabia. Children. 2018;5:39. doi: 10.3390/children5030039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ahmed HG, Ginawi IA, Elasbali AM, Ashankyty IM, Al-Hazimi AM. Prevalence of obesity in Hail region, KSA: In a comprehensive survey. J Obes 2014. 2014:961861. doi: 10.1155/2014/961861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aldubikhi A. Obesity management in the Saudi population. Saudi Med J. 2023;44:725. doi: 10.15537/smj.2023.44.8.20220724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wadden TA, Tronieri JS, Butryn ML. Lifestyle modification approaches for the treatment of obesity in adults. Am Psychol. 2020;75:235. doi: 10.1037/amp0000517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alrashid FF, Idris SA, Alshammari HA, Dawas A, Altamimi HSA. Current status of bariatric surgery perceptions in Hail region, Saudi Arabia. Med Sci. 2022;26 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alqunaibet A, Herbst CH, El-Saharty S, Algwizani A. Noncommunicable Diseases in Saudi Arabia: Toward Effective Interventions for Prevention. World Bank Publications. 2021 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alfadda AA, Al-Dhwayan MM, Alharbi AA, Al Khudhair BK, Al Nozha OM, Al-Qahtani NM, et al. The Saudi clinical practice guideline for the management of overweight and obesity in adults. Saudi Med J. 2016;37:1151. doi: 10.15537/smj.2016.10.14353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pfinder M, Heise TL, Boon MH, Pega F, Fenton C, Griebler U, et al. Taxation of unprocessed sugar or sugar-added foods for reducing their consumption and preventing obesity or other adverse health outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;4:CD01233. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012333.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mönninghoff A, Kramer JN, Hess AJ, Ismailova K, Teepe GW, Car LT, et al. Long-term effectiveness of mHealth physical activity interventions: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23:e26699. doi: 10.2196/26699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bretschneider MP, Klásek J, Karbanová M, Timpel P, Herrmann S, Schwarz PE. Impact of a digital lifestyle intervention on diabetes self-management: A pilot study. Nutrients. 2022;14:1810. doi: 10.3390/nu14091810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alencar MK, Johnson K, Mullur R, Gray V, Gutierrez E, Korosteleva O. The efficacy of a telemedicine-based weight loss program with video conference health coaching support. J Telemed Telecare. 2019;25:151–7. doi: 10.1177/1357633X17745471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ross R, Neeland IJ, Yamashita S, Shai I, Seidell J, Magni P, et al. Waist circumference as a vital sign in clinical practice: A Consensus Statement from the IAS and ICCR Working Group on Visceral Obesity. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2020;16:177–89. doi: 10.1038/s41574-019-0310-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Qin W, Yang J, Deng C, Ruan Q, Duan K. Efficacy and safety of semaglutide 2.4 mg for weight loss in overweight or obese adults without diabetes: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis including the 2-year STEP 5 trial. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2024;26:911–23. doi: 10.1111/dom.15386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Enright C, Thomas E, Saxon DR. An updated approach to antiobesity pharmacotherapy: Moving beyond the 5% weight loss goal. J Endocr Soc. 2023;7:bvac195. doi: 10.1210/jendso/bvac195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hampl S, Paves H, Laubscher K, Eneli I. Patient engagement and attrition in pediatric obesity clinics and programs: Results and recommendations. Pediatrics. 2011;128((Suppl 2)):S59–64. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-0480E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Karmore UP, Ukey UU, Sharma SK. Effect of dietary modification and physical activity on obese young adults going to gym for weight loss in central India: A before and after study. Cureus. 2023;15:e4083. doi: 10.7759/cureus.40832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Al Ghareeb G, Abdoh D, Kuffy M, Afify A, City R, Arabia S. Lifestyle interventions can work with super-super obese patient BMI of 90.5 kg/m2: Case Report. 2024 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Williamson DA, Bray GA, Ryan DH. Is 5% weight loss a satisfactory criterion to define clinically significant weight loss? Obesity. 2015;23:2319. doi: 10.1002/oby.21358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tapsell LC, Lonergan M, Batterham MJ, Neale EP, Martin A, Thorne R, et al. Effect of interdisciplinary care on weight loss: A randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e014533. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Walsham JM. The Importance of Nutrition and Fitness Professionals in Weight Loss Weight Loss Maintenance and Body Recomposition. 2022 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pinto LFLQ. Scientific Evidence on Food and Nutrition Policy Actions: A Literature Review. 2022 [Google Scholar]

- 28.An J, Yoon SR, Lee JH, Kim H, Kim OY. Importance of adherence to personalized diet intervention in obesity related metabolic improvement in overweight and obese Korean adults. Clin Nutr Res. 2019;8:171. doi: 10.7762/cnr.2019.8.3.171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bolognese MA, Franco CB, Ferrari A, Bennemann RM, Lopes SMA, Bertolini SMMG, et al. Group nutrition counseling or individualized prescription for women with obesity? A clinical trial. Front Public Health. 2020;8:127. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee HS, Lee J. Effects of exercise interventions on weight, body mass index, lean body mass and accumulated visceral fat in overweight and obese individuals: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:2635. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18052635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee HS, Lee J. Effects of combined exercise and low carbohydrate ketogenic diet interventions on waist circumference and triglycerides in overweight and obese individuals: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:828. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18020828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Armstrong A, Jungbluth Rodriguez K, Sabag A, Mavros Y, Parker HM, Keating SE, et al. Effect of aerobic exercise on waist circumference in adults with overweight or obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2022;23:e13446. doi: 10.1111/obr.13446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.El-Deyarbi M, Ahmed L, King J, Al Nuaimi H, Al Juboori A, Mansour NA, et al. Effect of structured diet with exercise education on anthropometry and lifestyle modification in patients with type 2 diabetes: A 12-month randomized clinical trial. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2024;213:111754. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2024.111754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Suminski RR, Leonard T, Obrusnikova I, Kelly K. The impact of health coaching on weight and physical activity in obese adults: A randomized control trial. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2024;18:233–42. doi: 10.1177/15598276221114047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gorczyca AM, Washburn RA, Ptomey LT, Mayo MS, Krebill R, Sullivan DK, et al. Weight management in rural health clinics: Results from the randomized midwest diet and exercise trial. Obes Sci Pract. 2024;10:e753. doi: 10.1002/osp4.753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rotunda W, Rains C, Jacobs SR, Ng V, Lee R, Rutledge S, et al. Weight loss in short-term interventions for physical activity and nutrition among adults with overweight or obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Prev Chronic Dis. 2024;21:E21. doi: 10.5888/pcd21.230347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.García-Rodríguez R, Vázquez-Rodríguez A, Bellahmar-Lkadiri S, Salmonte-Rodríguez A, Siverio-Díaz A, De Paz-Pérez P, et al. Effectiveness of a nurse-led telehealth intervention to improve adherence to healthy eating and physical activity habits in overweight or obese young adults. Nutrients. 2024;16:2217. doi: 10.3390/nu16142217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]