Abstract

Extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL)-producing Escherichia coli resists broad-spectrum cephalosporins, considered as a critical priority pathogen, and its presence in animals, humans, and the environment highlights its significance as a One Health issue. Dairy farm waste is a potential environmental contaminant and can serves as a significant reservoir for the emergence and spread of ESBL-producing E. coli, which belongs to One Health clones and poses a serious global threat. This study aimed to investigate the occurrence and genomic characteristics of ESBL-producing E. coli clones of One Health concern from dairy farm waste in Gansu, China. In this study, we isolated and characterized two CTX-M-55 ESBL-producing E. coli strains, ZYX8158 and ZYS8091, which belong to One Health clones. The genomic analysis revealed a large resistome, mobilome, virulome, and plasmidome was acquired by both ESBL-producing E. coli strains. The genome-based typing revealed that E. coli ZYX8158 and ZYS8091 belonged to globally disseminated clones ST10 (O73:H31 serotype) and ST2325 (O66:H25 serotype), respectively. Phylogeographical analysis revealed both strains as potential One Health clones due to their clustering with related E. coli strains isolated from animal, human, and environmental sources, regardless of geographical boundaries, indicating their zoonotic potential and clonal spread in the One Health sector. This study highlights that dairy farm waste can be a potential source of the emergence and dissemination of One Health clones of critical priority ESBL-producing E. coli in One Health settings, which demands continuous and integrated genomic surveillance for comprehensive knowledge and mitigation strategies.

Keywords: Genomic surveillance, ESBL-producing E. coli, Resistome, Virulome, Mobilome, One Health clones

1. Introduction

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is a global public health crisis that undermines the effectiveness of antibiotics, complicating the treatment of once-manageable infections [1]. The high occurrence of multidrug-resistant (MDR) bacteria is the most concerning outcome of AMR, particularly at One Health (animal-human-environment) interface, which has been recognized as a critical global issue [[2], [3], [4]]. The emergence of MDR bacteria has led to a significant rise in disease burden, including increased morbidity, mortality, financial costs, and threats to food safety, making it one of the most critical challenges [5]. To address the growing AMR crisis, the World Health Organization (WHO) has designed the One Health approach as a global strategy emphasizing the intimate connection between One Health sectors [6,7]. Salman et al. [8] highlighted that antibiotic-resistant bacteria (ARB) and antibiotic-resistance genes (ARGs), particularly the ESBL-producing E. coli, are pervasive in One Health sectors, including animal, human, food, and environmental settings. The unjustified antibiotic usage in animal settings, including dairy farms, has driver the evolution of ARBs and their spread to human beings through contaminated food, close contact, and environmental exposure [1,2,9]. Dairy farm waste is a significant source of the spread of ARB through environmental contamination, including soil, water reservoirs, the aquatic environment, and close human settings [[10], [11], [12], [13]]. These factors significantly contribute to the spread of ARB and their associated ARGs across One Health sectors, representing a potential risk to public health [[14], [15], [16], [17]]. The emergence of ARGs (e.g., ESBL genes) is the most concerning pollutant of dairy farm waste, which poses potential environmental and human health risks due to horizontal gene transfer (HGT) [13]. The environment, especially human-disturbed ecosystems, is increasingly recognized as a hotspot for the evolution and transmission of ARB and ARGs [18,19]. Controlling ARB in the One Health sector is critical to protecting human and animal health [18,20]. This highlight the need for ongoing genomic surveillance of WHO-critical pathogens such as E. coli at the One Health interfaces.

Escherichia coli (E. coli) is a normal resident of the human and animal intestinal tracts, possessing a dynamic interplay from commensal microbe to pathogenic E. coli responsible for causing gastrointestinal infections, bacteremia, septicemia, neonatal meningitis and urinary tract infections [[21], [22], [23]]. The virulence potential of E. coli is determined by its ability to acquire genetic determinants encoding diverse pathogenicity mechanisms, including: cell adherence and invasion, toxin and secretion system deployment, biofilm development, immune evasion, and nutritional acquisition systems [24,25]. The rise in AMR also increases the pathogenicity of colonized bacteria by rendering the infections refractory to antibiotic therapy, thereby evaluating the public health risks. Notably, both pathogenic and commensal E. coli serve as key vectors for ARGs dissemination among human and animal populations, facilitating interspecies transmission of resistant phenotypes [26,27]. Globally, the significant rise of AMR in E. coli is of great public health concern because of its wide host and source adoptability [28]. E. coli is a good indicator for evaluating, determining the current status, and comparing AMR across multiple sectors and possible transmission between One Health components [5,29]. E. coli carrying resistance plasmids with horizontal transferability plays a significant role in disseminating ARGs. Other mobile genetic elements (MGEs) including integrons (Ints), insertion sequences (ISs), and composite transposons (CTs), also mediate the spread of ARGs [30]. Ints linked to the plasmids play a pivotal role in the spread of ARGs across diverse bacterial species. Ints can also capture multiple ARGs, forming new gene cassettes. Due to their mobile nature, these newly formed cassettes facilitate the rapid spread of MDR phenotypes among bacterial populations [31]. Several investigations have demonstrated that intI1 is more prevalent in antibiotic-polluted environments and may serve as a general environmental pollution indicator [32,33]. Moreover, the ISs (e.g., IS2) and transposons (e.g., Tn3 and similar elements) also serve as key drivers of ARG spread in environmental reservoirs [[33], [34], [35]].

Beta-lactams are the most widely used antibiotics in human and animal settings worldwide [36]. Production of ESBL enzymes by bacteria renders broad-spectrum beta-lactams, particularly cephalosporins, ineffective. Among Enterobacteriaceae, ESBL-producing E. coli is the most prevalent pathogen distributed in One Health components [8]. Notably, the dairy farm environment has also emerged as a potential reservoir of ESBL-producing E. coli in China [28]. Multiple other studies have also identified the ESBL-producing E. coli strains from livestock [[37], [38], [39]] and environmental settings [40]. Among various ESBL types, CTX-M has been recognized as the most prevalent ESBL among Enterobacteriaceae globally [[41], [42], [43], [44]]. Although dairy farm waste is a suspected hotspot for antimicrobial resistance, few studies have genomically characterized ESBL-producing E. coli strains of One Health concern from this environment. Hereby, we report the emergence and genomic characteristics of two ESBL-producing Escherichia coli ST10 and ST2325 clones of One Health concern recovered from dairy farm waste in Gansu province, China.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Bacterial isolation, identification, and antimicrobial susceptibility testing

Between 2017 and 2019, we conducted a local surveillance study to investigate the occurrence and AMR characteristics of critical priority pathogen E. coli in dairy farm waste in Gansu province, China [45]. We collected the feces (50 g) and sewage (50 mL) samples (n = 319) from two large dairy farms (Farms S and X, herd size >10,000 cows) located in Zhangye County. The samples were collected in sterile bags (feces) and tubes (sewage) and stored at 4 °C during transportation to the laboratory. First, we enriched the samples in Luria Bertani (LB) broth, and the pre-enrichment stock was stored at −80 °C in 20 % glycerol for later use. The small pre-enriched inoculum was sub-cultured on MacConkey (MAC) and Eosin Methylene Blue (EMB) agar for selective differentiation following the incubation conditions at 37 °C for 24 h. As described earlier, we subjected the purified colonies to the 16S rDNA gene detection and MALDI-TOF MS for species identification [46]. We performed antimicrobial susceptibility testing and interpreted the results according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standard Institute [47] and European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) (http://www.eucast.org/, accessed on 10 September 2024) guidelines and breakpoints. The tested antibiotics belong to different classes were ampicillin, cefotaxime, ceftazidime, cefazolin, ceftriaxone, ceftazidime/clavulanate, cefotaxime/clavulanate, meropenem, kanamycin, gentamicin, amikacin, apramycin, polymyxin B, tetracycline, tigecycline, erythromycin, chloramphenicol, fosfomycin, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, norfloxacin, ciprofloxacin, and ofloxacin. The E. coli ATCC 25922 was used as a susceptibility quality control strain.

2.2. Whole genome sequencing and data processing

We extracted the bacterial DNA using the TIANamp bacterial DNA extraction kit (Tiangen, China). The extracted DNA was quality checked by Qubit 4.0 fluorometer (ThermoFisher Scientific, USA) and sequencing was performed by Novogene Technology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). The sequencing libraries was prepared using the NEBNext® Ultra™ DNA library kit and NovaSeq PE150 (Illumina, USA) was used to sequence the prepared libraries. The raw data obtained was quality-checked by FastQC version 0.11.8. We filtered the data using Trimmomatic v.0.39 [48] and de novo assembly using SPAdes v4.2.0 [49]. We refined the draft assembly with GapClose v1.12, eliminating low-coverage regions (<0.35×) and short fragments (<500 bp) to produce the final assembly for bioinformatics analysis. The coding genes were predicted using the GeneMarkS version 4.17 [50], and functional annotation of genes was performed using the Cluster of Orthologous Groups (COG) database [51] to classify protein coding sequences into functional categories.

2.3. Bioinformatics analysis

The assembled data were subjected to the CARD and ResFinder 2.0 [52] using Abricate to identify resistome. PlasmidFinder 2.1 [53] and ISfinder [54] were used to identify plasmid typing and mobile elements. The virulome analysis was conducted by the Virulence Factor Database (VFDB) [55], and Pathogen prediction as a human pathogen by PathogenFinder 1.1 [56]. Molecular typing, such as serotype, CH Type, fimH allele type, multilocus sequence type (MLST), and core genome MLST (cgMLST), was determined by SerotypeFinder 2.0, CHTyper 1.0, FimTyper 1.0, MLST 2.0, and cgMLSTFinder 1.2 under the Center for Genomic Epidemiology (CGE) server (https://cge.food.dtu.dk/services/, accessed on 20 September 2024).

For comparative phylogenomic analysis, we constructed the phylogenetic tree using the BacWGSTdb database (https://bacdb.cn/BacWGSTdb/, accessed on 15 November 2024) based on core-genome MLST (cgMLST) and extracted their epidemiological and genomic information (host, country, and isolation source). We utilized the ChiPlot (https://www.chiplot.online/, accessed on 25 November 2024) online web-based tool for the final editing and visualization of the tree.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Antimicrobial susceptibility of CTX-M-55 ESBL-producing E. coli strains

Among the isolated strains, only two CTX-M-55 ESBL-producing E. coli, ZYX8158 and ZYS8091, belonging to ST10 and ST2325, were retrieved from sewage and feces samples, respectively. The MICs of ESBL-producing E. coli strains indicated that they are both multidrug-resistant (MDR) and ESBL-producing. Both of the strains showed resistance to all antimicrobials except meropenem (≤0.25 μg/mL), tigecycline (≤0.25 μg/mL), ofloxacin (≤0.25 μg/mL), and norfloxacin (≤0.25 μg/mL). The MIC of erythromycin was noted at 256 μg/mL and 512 μg/mL by E. coli ZYX8158 and E. coli ZYS8091 strains, respectively. The CLSI and EUCAST have no clinical breakpoints for erythromycin against Enterobacterales. Table 1 presents the MICs of all other antimicrobials tested. Recently, there have been increasing reports on the MDR ESBL-producing E. coli from various settings [[57], [58], [59], [60]], contributing significantly to the rising AMR crisis globally. Emergence of MDR ESBL-producing E. coli from dairy farm waste in Gansu province, China, recommends further surveillance and immediate control measures among all One Health components.

Table 1.

Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of CTX-M-55 ESBL-producing E. coli strains.

| Antibiotic class | Antibiotics |

E. coli ZYX8158 |

E. coli ZYS8091 |

E. coli ATCC 25922 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIC (μg/mL) | Phenotype | MIC (μg/mL) | Phenotype | MIC (μg/mL) | ||

| Penicillin | AMP | ≥512 | R | ≥512 | R | 4 |

| Cephems | CTX | ≥256 | R | ≥256 | R | 0.12 |

| CAZ | 128 | R | 32 | R | 0.25 | |

| KZ | ≥256 | R | ≥256 | R | 2 | |

| CRO | ≥64 | R | ≥64 | R | <0.25 | |

| Cephems+ β-lactamase inhibitor |

CAZ/CLV | ≤4 | ESBL | ≤1 | ESBL | <0.015 |

| CTX/CLV | ≤16 | ESBL | ≤16 | ESBL | <0.03 | |

| Carbapenem | MEM | ≤0.25 | S | ≤0.25 | S | <0.12 |

| Aminoglycosides | KAN | ≥512 | R | ≥512 | R | 2 |

| CN | 128 | R | 64 | R | 0.5 | |

| AMK | 256 | R | 256 | R | 2 | |

| APR | ||||||

| Quinolone's | CIP | 4 | R | 4 | R | <0.12 |

| OFX | ≤0.25 | S | ≤0.25 | S | ≤0.12 | |

| NOR | ≤0.25 | S | ≤0.25 | S | ≤0.12 | |

| Macrolides | ERY | ≥512 | NB | 256 | NB | NB |

| Tetracycline | TET | ≥512 | R | ≥256 | R | 1 |

| TGC | ≤0.25 | S | ≤0.25 | S | ≤0.25 | |

| Phosphonic | FOS | ≥512 | R | ≥512 | R | 1 |

| Phenicol | CHL | 128 | R | 128 | R | 2 |

| Peptide | PB | 16 | R | 16 | R | 1 |

| Trimethoprim-Sulfamethoxazole | SXT | ≥256/512 | R | ≥256/512 | R | ≤0.5/9.5 |

R = Resistant, S = Susceptible, ESBL = Extended-spectrum beta-lactamase, NB = No breakpoint, AMP = Ampicillin, CTX = Cefotaxime, CAZ = Ceftazidime, KZ = Cefazolin, CRO = Ceftriaxone, CAZ/CLV = Ceftazidime-Clavulanate, CTX/CLV = Cefotaxime-Clavulanate, MEM = Meropenem, KAN = Kanamycin, CN = Gentamicin, AMK = Amikacin, APR = Apramycin, CIP = Ciprofloxacin, OFX = Ofloxacin, NOR = Norfloxacin, ERY = Erythromycin, TET = Tetracycline, FOS = Fosfomycin, CHL = Chloramphenicol, PB = Polymyxin B, SXT = Trimethoprim-Sulfamethoxazole.

3.2. Resistome and mobilome

The genomic analysis revealed diverse ARGs and mobile elements identified by CARD, ResFinder, and ISFinder. Each of the E. coli strains acquired a total of n = 26 ARGs. The similar genes acquired by both strains were blaTEM-1B, blaCTX-M-55 (confer resistance to β-lactams), rmtB (confer resistance to aminoglycosides), pmrF, eptA, ugd, bacA (confer resistance to peptides), cmlA1 (confer resistance to phenicols), and AcrAB-TolC-AcrR, AcrAB-TolC-MarR, soxS, soxR, marA (confer resistance to multiple antimicrobials). The other ARGs acquired by E. coli ZYX8158 (ST10) strain were consisted of β-lactams (blaCTX-M-14, blaEC-15, blaLAP-2), trimethoprim (dfrA14), macrolides (mph(A), mrxA), sulfonamides (sul2), aminoglycosides (aph(6)-Id, aac(3)-IId, aph(3″)-Ib, aac(6′)-Ib-cr, aac(6′)-Ib3), fluoroquinolones (qnrS1, aac(6′)-Ib-cr), and tetracycline (tetA). The other strain, E. coli ZYS8091 (ST2325), harbored β-lactams (blaCARB-2), aminoglycosides (aadA1, aadA2, aadA3), and phosphonic resistance genes (fosA3, glpT) along with trimethoprim (dfrA16), sulfonamide (sul3), and quinolone resistance determinant (gyrA) (Table 2). The E. coli ZYX8158 strain co-harbored blaCTX-M-14 and blaCTX-M-55 genes in this study. A recent study by Yang et al. [61] also reported the co-occurrence of blaCTX-M-14 and blaCTX-M-64 genes in a clinical E. coli strain from China. Another study also reported that 7.7 % of ESBL-producing E. coli strains from chickens were also co-harboring CTX-M-1 and CTX-M-9 group genes [62]. A similar study reported that 36.1 % (13/36) isolates carried two different blaCTX-M genes among CTX-M-producing E. coli from piglets in China [63]. The co-occurrence of blaCTX-M genes may indicate the growing trend of convergence of multiple ESBL genes, which may be associated with MGEs in the presence of antibiotic selective pressure, co-selection, and spread of successful bacterial clones in China. Multiple studies have highlighted that the environment, particularly at human-animal interfaces, servers as a key reservoir of clinically important ARGs, posing cross-species transmission risks that threaten public health [40,64,65]. The environment, especially human-disturbed ecosystems, is increasingly recognized as a hotspot for the evolution and transmission of ARB and ARGs [18,19]. The identification of One Health clones carrying a large resistome in dairy farm waste in Gansu, China, contributes to the growing AMR crisis globally and needs potential consideration.

Table 2.

Genomic characteristics of CTX-M-55 ESBL-producing E. coli strains.

| Genomic features | E. coli ZYX8158 | E. coli ZYS8091 |

|---|---|---|

| Resistome | ||

| β-lactam | blaTEM-1B, blaCTX-M-55, blaCTX-M-14, blaEC-15, blaLAP-2 | blaTEM-1B, blaCTX-M-55, blaCARB-2 |

| Trimethoprim | dfrA14 | dfrA16 |

| Macrolide | mph(A), mrx(A) | – |

| Sulfonamides | sul2 | sul3 |

| Aminoglycosides | rmtB, aph(6)-Id, aph(3″)-Ib, aac(6′)-Ib3, aac(3)-IId | aadA1, aadA2, aadA3, rmtB |

| Peptide | pmrF, eptA, ugd, bacA | pmrF, eptA, ugd, bacA |

| Phosphonic | – | fosA3, glpT |

| Fluoroquinolones | qnrS1, aac(6′)-Ib-cr | gyrA |

| Phenicol | cmlA1 | cmlA1 |

| Tetracycline | tet(A) | – |

| MDR-related | AcrAB-TolC-AcrR, AcrAB-TolC-MarR, soxS, soxR, marA | AcrAB-TolC-AcrR, AcrAB-TolC-MarR, soxS, soxR, marA |

| Mobile genetic elements | ISKpn19, IS5075, IS102, IS6100, ISEc81, MITEEc1, IS30, IS911, ISKox3, ISEc1, cn_2244_ISEc1, ISKpn8, IS629, ISEc9, IS421, ISEhe3 | ISKpn26, IS100, MITEEc1, IS5, ISEc1, ISKpn8, IS421, IS30 |

| Plasmid replicon types | IncCol(pHAD28), IncFIB(K), IncFIB(pHCM2), IncFII(pHN7A8), IncI1-I(Alpha) |

IncFIA(HI1), IncFII(pHN7A8), IncN, IncR |

| MLST | ST10 | ST2325 |

| CH Type | fumC11:fimH23 | fumC7-fimH40 |

| Phylogroup | A | A |

AMR = Antimicrobial resistance, MDR = Multi-drug resistance, MLST = Multi-locus sequence typing.

The results of ISFinder revealed that the predominant MGEs detected in the E. coli ST10 genome at ≥90 % identity and query coverage were multiple insertion sequences (ISKpn19, IS5075, IS102, IS6100, ISEc81, IS30, IS911, ISKox3, ISEc1, ISKpn8, IS629, ISEc9, IS421, ISEhe3) followed by miniature inverted repeats (MITEEc1), and composite transposon (cn_2244_ISEc1). The genome of E. coli ST2325 strain was integrating ISKpn26, IS100, MITEEc1, IS5, ISEc1, ISKpn8, IS421, and IS30 mobile elements (Table 2). The MGEs are important in disseminating ARGs within and between bacterial species of the One Health sectors. They can pick up multiple genes or large DNA pieces, transform them into new gene clusters, genomic islands, or prophages, and transfer them through recombination or horizontal gene transfer (HGT) events [66,67]. ISs are predominant and widely distributed MGEs, as demonstrated by Che et al. [68]. Their study revealed that >77 % of plasmid-mediated ARGs were linked with ISs, and nearly 63 % of ARG transfer events occurred between resistant plasmids and bacterial chromosomes. Moreover, the CTs facilitate the spread of ARGs through transposition [69]. CTs facilitate the translocation of ARGs between the chromosome and plasmids, thereby accelerating their dissemination via HGT [70].

3.3. Virulome, serotyping, prediction as a human pathogen, and relationship with E. coli pathotypes

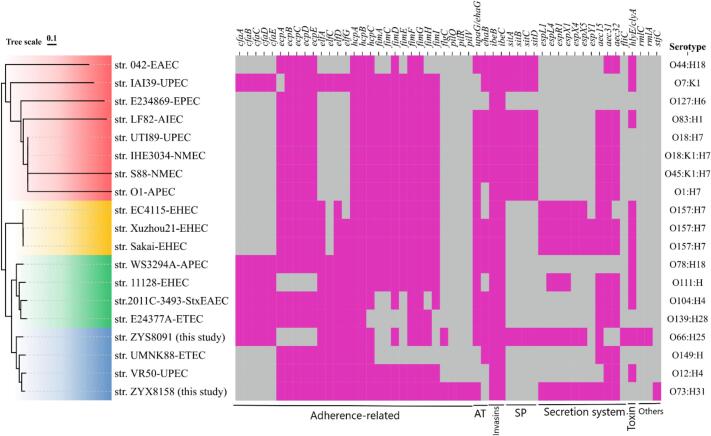

This study identified virulence determinants carried by E. coli ST10 (ZYX8158) and ST2325 (ZYS8091) strains using the Virulence Factor Database (VFDB) and their prediction as human pathogens by PathogenFinder. PathogenFinder predicted both strains as human pathogens based on virulence gene matches with known E. coli strains in the PathogenFinder database. The VFDB results revealed that ZYX8158 acquired 38 virulence determinant subtypes, while ZYS8091 contained 36 subtypes (Fig. 1), indicating both strains possess substantial virulence potential. E. coli ZYS8091 virulence determinants included 17 adherence factors, 2 autotransporters (upaG/ehaG, ehaB), 2 invasions (ibeB/C), the complete sitABCD iron uptake system, 6 non-LEE T3SS effectors (espL1/L4/R1/X1/X4/X5), 2 secretion systems (aec15, fliC), hemolysin hlyE/clyA, and immune evasion factors rmlC (anti-phagocytosis) and rmlA (serum resistance). The E. coli strain ZYX8158 harbored 24 adherence factors, 1 autotransporter (upaG/ehaG), 2 invasions (ibeB/C), 7 non-LEE-encoded TTSS effectors (espL1/L4/R1/X1/X4/X5/Y1), 3 secretion systems (aec15, aec31, aec32), but lacked iron acquisition and immune evasion mechanisms. The ZYX8158 strain also harbored a gene similar to stjC, a fimbrial adherence determinant of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi [71]. A recent study by Carramaschi et al. [72] also identified the stjC fimbrial determinant in E. coli ST9499 harboring blaNDM-1 from Brazil. The stjC determinant substantially contributes to long-term host colonization and adaptation. Both genomes contained abundant virulence determinants - particularly adherence factors, non-LEE T3SS effectors, invasions, and autotransporters - that collectively enhance host colonization capacity. Moreover, the serotype analysis revealed that both strains, ZYX8158 and ZYS8091, belonged to two distinct serotypes: O73:H31 and O66:H25. Previously, two E. coli strains (accessions UNQE01 and UNQG01) belonging to the O73:H31 serotype were reported from France and recovered from human feces. An earlier study reported an E. coli O66:H25 strain (accession LR134000) from an unknown source and country. To determine clonal relatedness, we performed core-genome SNP phylogeny in CSIPhylogeny, comparing both strains against verified E. coli pathotypes (Table S1). Phylogenetic analysis revealed that the ZYX8158 strain clusters closely with uropathogenic E. coli (UPEC) strain VR50. In contrast, the ZYS8091 strain showed a close relationship with enterotoxigenic E. coli (ETEC) strain UMNK88. All strains form a monophyletic clade (highlighted in light blue, Fig. 1), suggesting shared ancestry despite pathotype differences.

Fig. 1.

Phylogenetic analysis based on core-genome SNPs and distribution of virulence factors (VFs) and serotypes of the present study E. coli strains and their comparison with verified E. coli pathotypes. AT = autotransporter, SP = siderophore. EAEC, Enteroaggregative E. coli; AIEC, Adherent-invasive E. coli; UPEC, Uropathogenic E. coli; APEC, avian pathogenic E. coli; NMEC, Neonatal meningitis E. coli; EHEC, Enterohemorrhagic E. coli; STEC, Shiga toxin-producing E. coli; ETEC, Enterotoxigenic E. coli.

3.4. Plasmid replicon typing and their geographical distribution

Plasmids critically facilitate the dissemination of ARGs through HGT, presenting a serious risk to human health [73]. Most of the plasmid-mediated ARGs originate from the environment, animal, and human habitats, and plasmids allow the spread of ARGs at different biological levels, different bacteria within the same microbiome, between microbiomes within the same habitat, and between different One Health settings [74]. We performed in silico plasmid replicon typing using WGS data through PlasmidFinder (PF) on the CGE web server. The PF results revealed that E. coli ST10 strain was carrying five plasmid replicon types; Col(pHAD28), IncFIB(K), IncFIB(pHCM2), IncFII(pHN7A8), and IncI1-I(Alpha) while the E. coli ST2325 strain was carrying four plasmids; IncFIA(HI1), IncFII(pHN7A8), IncN, and IncR (Table 2). We used the single-genome analysis tool in BacWGSTdb (https://bacdb.cn/BacWGSTdb/; accessed 15 November 2024) to determine the geographical distribution of identified plasmid types among Enterobacteriaceae. The results of BacWGSTdb revealed 51 and 27 hits with ≥99 % similarity against ZYX8158 and ZYS8091 genomes, respectively (Table 3, Table 4). Among the 51 hits against the ZYX8158 genome, n = 28 hits were of IncFII(pHN7A8), n = 13 of IncI1-I(Gamma), and n = 10 of IncFIB(K) plasmid type. The size of IncFII(pHN7A8), IncFIB(K), and IncI1-I(Gamma) ranged from 62,594–91,701 bp, 41,152–83,157 bp, and 18,052–96,532 bp, respectively. Our analysis revealed that IncFII(pHN7A8) plasmid type predominates in China (24/28, 85.7 %), with sporadic occurrence in Bolivia (2/28, 7.1 %), South Korea (1/28, 3.6 %), and Brazil (1/28, 3.6 %). Similarly, the IncFIB(K) was also most frequently reported from China (n = 5), USA (n = 2), Nigeria (n = 1), Australia (n = 1), and Tanzania (n = 1). In contrast, the IncI1-I plasmid type was reported dynamically from multiple countries, including China, the USA, the United Kingdom, Singapore, Portugal, and Denmark (Table 3). Our analysis revealed that IncFII(pHN7A8), IncFIB(K), and IncI1-I(γ) plasmids have disseminated across diverse bacterial species, hosts, and geographical regions, underscoring their significant transmission potential with the One Health sectors. Additionally, the hits against the other two plasmid replicon types, Col(pHAD28) and IncFIB(pHCM2), were not identified, which may indicate the novel plasmid types identified in the E. coli ZYX8158 strain isolated from cattle feces of the dairy farm environment. Among the plasmids acquired by E. coli ZYS8091, IncFII(pHN7A8) was the most predominant type in China, with additional reports from South Korea, Bolivia, and Brazil. The IncFIA(HI1) and IncR plasmids have only been reported from Germany in an E. coli strain (accession NZ_CP018105.1) of clinical origin. The IncN incompatibility group plasmid has been previously identified in an E. coli strain (accession NZ_CP032991.1) isolated from river water in Chengdu, China (Table 4).

Table 3.

Geographical distribution of closely related plasmids acquired by the E. coli ZYX8158 strain (ST10 clone).

| Plasmid name | Size (bp) | Species | Host | Source | Region/country | Plasmid replicon types | Accession number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pS39-3 | 41,152 | Citrobacter sp. | – | – | Guangzhou, China | IncFIB(K) | CP045558.1 |

| pHNMPC51 | 69,654 | K. pneumoniae | Food | Pork | Guangzhou, China | IncFII(pHN7A8) | MG197500.1 |

| pHNMPC43 | 69,666 | K. pneumoniae | Food | Pork | Guangzhou, China | IncFII(pHN7A8) | MG197501.1 |

| pLWY24J-3 | 68,718 | E. coli | Chicken | Feces | China | IncFII(pHN7A8) | MN702385.1 |

| pHNMPC32 | 74,768 | E. coli | Food | Pork | Guangzhou, China | IncFII(pHN7A8) | MG197499.1 |

| p477Kp | 74,768 | K. pneumoniae | Homo sapiens | – | Bolivia | IncFII(pHN7A8) | LN897475.2 |

| pCREC-591_2 | 64,564 | E. coli | Homo sapiens | Peritoneal fluid | Incheon, South Korea | IncFII(pHN7A8) | NZ_CP024823.1 |

| pLSH-KPN148-2 | 72,060 | K. pneumoniae | Homo sapiens | Sputum | China | IncFII(pHN7A8) | NZ_CP040124.1 |

| pTEM-CBG | 75,044 | E. cloacae | Homo sapiens | Sputum | Guangzhou, China | IncFII(pHN7A8) | NZ_CP046117.1 |

| pHNAH33 | 74,962 | E. coli | Chicken | – | Anhui, China | IncFII(pHN7A8) | MG197496.1 |

| pHNHNC02 | 76,869 | E. coli | Chicken | – | Henan, China | IncFII(pHN7A8) | MG197497.1 |

| p397Kp | 76,863 | K. pneumoniae | Homo sapiens | – | Bolivia | IncFII(pHN7A8) | LN897474.2 |

| pHN7A8 | 76,878 | E. coli | Dog | – | Guangdong, China | IncFII(pHN7A8) | NC_019073.1 |

| pHNMC02 | 70,619 | E. coli | Chicken | – | Guangdong, China | IncFII(pHN7A8) | MG197489.1 |

| pHNGD4P177 | 70,643 | E. coli | Pig | – | Guangdong, China | IncFII(pHN7A8) | MG197492.1 |

| pCTX-M-55_005237 | 70,688 | E. coli | Homo sapiens | Rectal swab | Sichuan, China | IncFII(pHN7A8) | NZ_CP026576.2 |

| pFA27_2 | 66,924 | E. coli | Poultry | Fecal swab | Brazil | IncFII(pHN7A8) | KX608544.1 |

| pHNBC6-3 | 65,161 | K. pneumoniae | Food | Retail vegetable | Guangzhou, China | IncFII(pHN7A8) | MK079570.1 |

| pSAN1-08-1092 | 85,439 | S. enterica | Homo sapiens | Stool | USA | IncI1-I(Gamma) | CP019996.1 |

| unnamed2 | 78,308 | S. flexneri | Homo sapiens | – | Hangzhou, China | IncFIB(K) | NZ_CP020344.1 |

| pSa27-HP | 83,480 | Salmonella sp. | Food | Meat | Hong Kong, China | IncI1-I(Gamma) | MH884654.1 |

| psg_wt5 | 84,511 | S. enterica | Food | Wet market | Singapore | IncI1-I(Gamma) | NZ_CP037994.1 |

| pECF12 | 77,822 | E. coli | Chicken | Feces | China | IncFII(pHN7A8) | KY865322.1 |

| pSCE516-3 | 85,126 | E. coli | Chicken | – | China | IncFII(pHN7A8) | KX023260.1 |

| pFZ11 | 79,147 | E. coli | – | – | Fujian, China | IncFIB(K) | KY051550.1 |

| pRmtB_020023 | 73,313 | E. coli | Homo sapiens | – | Sichuan, China | IncFII(pHN7A8) | NZ_CP025949.1 |

| p14EC033e | 87,351 | E. coli | Homo sapiens | Clinical patient | China | IncI1-I(Gamma) | NZ_CP024152.1 |

| pRC960-1 | 75,231 | S. flexneri | Pig | Stool | China | IncFIB(K) | KY848295.1 |

| pI1_WCHEC050613 | 84,615 | E. coli | Environment | Sewage | Sichuan, China | IncI1-I(Gamma) | NZ_CP019215.2 |

| p2 | 84,987 | S. enterica | Homo sapiens | Blood | United Kingdom | IncI1-I(Gamma) | NZ_LN890525.1 |

| pSa44-CRO | 91,411 | S. enterica | – | – | China | IncI1-I(Gamma) | MH430883.1 |

| p12478-rmtB | 62,594 | K. pneumoniae | – | Beijing, China | IncFII(pHN7A8) | MN419308.1 | |

| pEC36-2 | 91,597 | E. coli | – | – | Henan, China | IncFII(pHN7A8) | MG591701.1 |

| p2 | 65,273 | S. enterica | – | Unknown | Tanzania | IncFIB(K) | NZ_LT904889.1 |

| unnamed1 | 69,554 | S. flexneri | – | – | USA | IncFIB(K) | NZ_CP024474.1 |

| unnamed | 68,319 | S. flexneri | – | – | USA | IncFIB(K) | NZ_CP026764.1 |

| p3 | 69,446 | S. flexneri | – | Feces | Australia | IncFIB(K) | NZ_LR213454.1 |

| pEF02 | 90,871 | E. fergusonii | Chicken | Feces | Zhejiang, China | IncFII(pHN7A8) | NZ_CP040807.1 |

| p92944-CTXM | 69,018 | E. coli | – | – | Beijing, China | IncFII(pHN7A8) | MH329656.1 |

| PHNEC46 | 74,046 | E. coli | – | – | Hong Kong, China | IncFII(pHN7A8) | KX503323.1 |

| pLWY24J-4 | 89,065 | E. coli | Chicken | Feces | China | IncI1-I(Gamma) | MN702386.1 |

| pPGRT46 | 83,155 | E. coli | – | – | Nigeria | IncFIB(K) | KM023153.1 |

| pWA8 | 83,157 | E. coli | – | – | Shandong, China | IncFIB(K) | MG773378.1 |

| p2009C-3554-1 | 83,424 | E. coli | – | Stool | USA | IncI1-I(Gamma) | NZ_CP034804.1 |

| pHNEC55 | 81,498 | E. coli | – | – | Hong Kong, China | IncFII(pHN7A8) | KT879914.1 |

| p13P477T-3 | 91,701 | E. coli | Pig | Stool | Hong Kong, China | IncFII(pHN7A8) | NZ_CP019276.1 |

| pYUW043 | 74,227 | S. enterica | Pig | – | Yangzhou, China | IncFII(pHN7A8) | MK778454.1 |

| pSAG-76334 | 96,532 | S. enterica | – | – | USA | IncI1-I(Gamma) | NZ_CP025455.1 |

| pLV23529-CTX-M-8 | 89,458 | E. coli | Pig | Portugal | IncI1-I(Gamma) | KY964068.1 | |

| pAMSC6 | 95,328 | E. coli | Giant panda | Feces | Sichuan, China | IncI1-I(Gamma) | NZ_CP031111.1 |

| unnamed | 18,052 | E. coli | Homo sapiens | Stool | Denmark | IncI1-I(Gamma) | NZ_CP011336.1 |

Table 4.

Geographical distribution of closely related plasmids acquired by the E. coli ZYS8091 strain (ST2325 clone).

| Plasmid name | Size (bp) | Species | Host | Source | Region/country | Plasmid replicon types | Accession number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p92944-CTXM | 69,018 | E. coli | – | – | Beijing, China | IncFII(pHN7A8) | MH329656.1 |

| pHNMC02 | 70,619 | E. coli | Chicken | – | Guangzhou, China | IncFII(pHN7A8) | MG197489.1 |

| pHNGD4P177 | 70,643 | E. coli | Pig | – | Guangzhou, China | IncFII(pHN7A8) | MG197492.1 |

| pLWY24J-3 | 68,718 | E. coli | Chicken | Feces | China | IncFII(pHN7A8) | MN702385.1 |

| pCTX-M-55_005237 | 70,688 | E. coli | Homo sapiens | Rectal swab | Sichuan, China | IncFII(pHN7A8) | NZ_CP026576.2 |

| pHNBC6-3 | 65,161 | K. pneumoniae | Food | Retail vegetable | Guangzhou, China | IncFII(pHN7A8) | MK079570.1 |

| pCREC-591_2 | 64,564 | E. coli | Homo sapiens | Peritoneal fluid | South Korea | IncFII(pHN7A8) | NZ_CP024823.1 |

| pFA27_2 | 66,924 | E. coli | Poultry | Fecal swab | Brazil | IncFII(pHN7A8) | KX608544.1 |

| pSCE516-3 | 85,126 | E. coli | Chicken | – | China | IncFII(pHN7A8) | KX023260.1 |

| pHNMPC51 | 69,654 | K. pneumoniae | Food | Pork | Guangzhou, China | IncFII(pHN7A8) | MG197500.1 |

| pHNMPC43 | 69,666 | K. pneumoniae | Food | Pork | Guangzhou, China | IncFII(pHN7A8) | MG197501.1 |

| pMR0716_PSE | 67,946 | E. coli | Homo sapiens | Clinical | Germany | IncFIA(HI1), IncR | NZ_CP018105.1 |

| pRmtB_020023 | 73,313 | E. coli | Homo sapiens | – | Sichuan, China | IncFII(pHN7A8) | NZ_CP025949.1 |

| pYUW043 | 74,227 | S. enterica | Pig | – | Yangzhou, China | IncFII(pHN7A8) | MK778454.1 |

| pTEM-CBG | 75,044 | E. cloacae | Homo sapiens | Sputum | Guangzhou, China | IncFII(pHN7A8) | NZ_CP046117.1 |

| pHNHNC02 | 76,869 | E. coli | Chicken | – | Henan, China | IncFII(pHN7A8) | MG197497.1 |

| pHNAH33 | 74,962 | E. coli | Chicken | – | Anhui, China | IncFII(pHN7A8) | MG197496.1 |

| p397Kp | 76,863 | K. pneumoniae | Homo sapiens | – | Bolivia | IncFII(pHN7A8) | LN897474.2 |

| pHN7A8 | 76,878 | E. coli | Dog | – | Guangdong, China | IncFII(pHN7A8) | NC_019073.1 |

| pHNMPC32 | 74,768 | E. coli | Food | Pork | Guangzhou, China | IncFII(pHN7A8) | MG197499.1 |

| p477Kp | 74,768 | K. pneumoniae | Homo sapiens | – | Bolivia | IncFII(pHN7A8) | LN897475.2 |

| pLSH-KPN148-2 | 72,060 | K. pneumoniae | Homo sapiens | Sputum | China | IncFII(pHN7A8) | NZ_CP040124.1 |

| p13P477T-3 | 91,701 | E. coli | Pig | Stool | Hong Kong, China | IncFII(pHN7A8) | NZ_CP019276.1 |

| p2_W2-5 | 83,867 | E. coli | Environment | River water | Chengdu, China | IncFII(pHN7A8), IncN | NZ_CP032991.1 |

3.5. Comparative phylogeographical analysis of E. coli ST10 and ST2325 clones

We performed a comparative phylogeographical analysis of ST10 and ST2325 clones using the BacWGSdb database based on core genome MLST (cgMLST) allelic profiles (Fig. 2A & B). The results revealed that E. coli ZYX8158 was clustered within the ST10 lineage, carrying multiple isolates from France, the USA, China, Australia, Germany, and the United Kingdom with allelic differences ranging from 192 to 260 (Table S2). Most isolates belonging to this cluster lineage were recovered from human, pig, and cow feces (Fig. 2A) except UMEA_3318_1 (accession AWDG01), isolated from the urine of a human patient suffering from urinary tract infection. Two isolates, MOD1_EC5362 (accession NOED01) from Branta feces and MOD1_EC5700 (accession NLHL01) from Antilocapra americana feces, clustered in the same lineage, suggesting possible cross-species transmission of this lineage. Our study also identified ST10 E. coli strains from diverse geographical regions including Ireland, Mexico, Tanzania, South Korea, Germany, and Ecuador, across multiple hosts. Additionally, two isolates (MOD1_EC908, accession NKDF01; and CAP28, accession JAAKCD01) from Mexico and Canada, isolated from Tadarida brasiliensis and cattle feces belonging to ST10 also showed close relatedness, with 420 and 428 allelic differences, respectively (Table S2). These results revealed that ST10 exhibits broad geographical distribution across multiple countries, host species, and environmental sources, representing a significant One Health concern due to its transmission potential.

Fig. 2.

The phylogenetic tree of geographically closely related clones based on core-genome MLST allelic profiles (Table S2, Table S3). (A) The phylogeographical analysis of ESBL-producing E. coli ST10 (ZYX8158) and closely related isolates. Our study revealed E. coli ST10 clones circulating across France, the USA, Australia, China, the United Kingdom, South Korea, Germany, Mexico, Canada, Tanzania, Ireland, and Ecuador (Retrieved data in Table S2). (B) The phylogeographical analysis of ESBL-producing E. coli ST2325 (ZYS8091) and closely related isolates. Our study revealed that ST2325 clones have been identified in the USA, the United Kingdom, Germany, China, and Pakistan (Retrieved data in Table S3).

The phylogenetic tree of geographically closely related clones based on core-genome MLST allelic profiles (Tables S2 and S3). (A) The phylogeographical analysis of ESBL-producing E. coli ST10 (ZYX8158) and closely related isolates. Our study revealed E. coli ST10 clones circulating across France, the USA, Australia, China, the United Kingdom, South Korea, Germany, Mexico, Canada, Tanzania, Ireland, and Ecuador (Retrieved data in Table S2). (B) The phylogeographical analysis of ESBL-producing E. coli ST2325 (ZYS8091) and closely related isolates. Our study revealed that ST2325 clones have been identified in the USA, the United Kingdom, Germany, China, and Pakistan (Retrieved data in Table S3).

The cgMLST cluster analysis of E. coli ZYS8091 (ST2325) showed a close relationship with the MOD1_EC6679 isolate (144 allele difference, accession NNSZ01) belonging to ST2325 and recovered from cow feces in the USA (Fig. 2B). Three dog isolates (accessions PUSV01, PUSR01, PUSQ01) belonging to ST2325, recovered from feces samples, were clustered under the same lineage and showed a close relationship with only 159 allelic differences (Table S3). Within this lineage, our study noted two isolates from the USA (cow and Odocoileus virginianus fecal origin) and one isolate of unknown origin (accession LR134000). ST2325 isolates have been widely reported, primarily from the United Kingdom, with additional cases identified in China, the USA, Pakistan, and Switzerland (Table S3). We noted that cows, pigs, humans, and caprines' feces were the primary reservoir for these isolates. Notably, two ST2325 isolates, G194 (accession LOOA01) isolated from the mammary gland and MOD1_EC5149 (accession NOGF01) isolated from the cow uterus, showing the multi-tissue tropism (Fig. 2B). Three isolates, (accessions UEKX01, UCYC01, and UCYW01) belonging to ST2325 also showed a close relationship with E. coli ZYS8091 (ST2325) with 185 allelic differences. These results demonstrate that ST2325 persists at dynamic levels across multiple geographical regions, host species, and ecological niches, highlighting its potential for intersectoral transmission within the One Health framework.

4. Conclusion

The present study comprehensively characterized two CTX-M-55 ESBL-producing E. coli strains belonging to One Health clones from the dairy farm waste in Gansu province, China. Genomic analysis revealed that both strains acquired numerous ARGs, VFs, and MGEs and predicted human pathogenic potential, suggesting potential risks to humans and animals through contaminated food chains and environmental routes. Moreover, the geographical distribution and clonal relationship analysis revealed that E. coli ST10 and ST2325 clones are spreading across multiple sources, hosts, and geographic boundaries, which may indicate their rapid adaptation in different settings. Detecting CTX-M-55-producing E. coli ST10 and ST2325 clones in dairy farm waste highlights a critical One Health concern. ST10 and ST2325 are globally disseminated clones linked to animal and human infections, suggesting zoonotic transmission potential. The environmental release of these strains, carrying broad resistomes and virulomes, may facilitate their spread from dairy farm waste to water, soil, and food chains, posing cross-sectoral One Health threats. Our findings underscore the urgent need for integrated One Health surveillance and intervention strategies to mitigate AMR risks at the human-animal-environment interface, such as improved farm management and strict antibiotic use regulations.

The following are the supplementary data related to this article.

SNP matrix of E. coli ZYX8158 and ZYS8091 with E. coli pathotypes.

Allele differences and metadata of E. coli (ZYX8158) ST10 clone with other strains from the database.

Allele differences and metadata of E. coli (ZYS8091) ST2325 clone with other strains from the database.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Muhammad Shoaib: Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Data curation. Muhammad Muddassir Ali: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Formal analysis. Minjia Tang: Software, Methodology, Investigation. Wang Weiwei: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Resources. Xuejing Zhang: Methodology, Investigation. Zhuolin He: Software, Methodology, Investigation. Zhongyong Wu: Writing – review & editing, Resources. Shengyi Wang: Validation, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization. Baocheng Hao: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Project administration. Ruichao Li: Writing – review & editing, Software, Resources. Wanxia Pu: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Resources, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization.

Funding statement

This project was supported by the Agricultural Science and Technology Innovation Program of the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (25-LZIHPS-03) and Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions (PAPD).

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare no financial and personal competing interests.

Contributor Information

Ruichao Li, Email: rchl88@yzu.edu.cn.

Wanxia Pu, Email: puwanxia@caas.cn.

Data availability

The whole genome sequence data of E. coli ZYX8158 and ZYS8091 have been deposited in NCBI under BioSample IDs SAMN41582031 and SAMN41581077, respectively.

References

- 1.Almansour A.M., Alhadlaq M.A., Alzahrani K.O., Mukhtar L.E., Alharbi A.L., Alajel S.M. The silent threat: antimicrobial-resistant pathogens in food-producing animals and their impact on public health. Microorganisms. 2023;11 doi: 10.3390/microorganisms11092127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zinno P., Perozzi G., Devirgiliis C. Foodborne microbial communities as potential reservoirs of antimicrobial resistance genes for pathogens: a critical review of the recent literature. Microorganisms. 2023;11 doi: 10.3390/microorganisms11071696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shoaib M., He Z., Geng X., Tang M., Hao R., Wang S., Shang R., Wang X., Zhang H., Pu W. The emergence of multi-drug resistant and virulence gene carrying Escherichia coli strains in the dairy environment: a rising threat to the environment, animal, and public health. Front. Microbiol. 2023;14 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2023.1197579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang Q., Wang W., Zhu Q., Shoaib M., Chengye W., Zhu Z., Wei X., Bai Y., Zhang J. The prevalent dynamic and genetic characterization of mcr-1 encoding multidrug resistant Escherichia coli strains recovered from poultry in Hebei, China. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2024;38:354–362. doi: 10.1016/j.jgar.2024.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dong N., Zeng Y., Cai C., Sun C., Lu J., Liu C., Zhou H., Sun Q., Shu L., Wang H., Wang Y., Wang S., Wu C., Chan E.W., Chen G., Shen Z., Chen S., Zhang R. Prevalence, transmission, and molecular epidemiology of tet(X)-positive bacteria among humans, animals, and environmental niches in China: an epidemiological, and genomic-based study. Sci. Total Environ. 2022;818 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.151767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sagar P., Aseem A., Banjara S.K., Veleri S. The role of food chain in antimicrobial resistance spread and One Health approach to reduce risks. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2023;391-393 doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2023.110148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hao R., Shoaib M., Tang M., Cao Z., Liu G., Zhang Y., Wang S., Shang R., Zhang H., Pu W. Genomic insights into resistome, virulome, and mobilome as organic contaminants of ESKAPE pathogens and E. coli recovered from milk, farm workers, and environmental settings in Hainan, China. Emerg. Contam. 2024;10 doi: 10.1016/j.emcon.2024.100385. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Salman S., Umar Z., Xiao Y. Current epidemiologic features and health dynamics of ESBL-producing Escherichia coli in China. Biosaf. Health. 2024;6:40–49. doi: 10.1016/j.bsheal.2024.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nawaz S., Shoaib M., Huang C., Jiang W., Bao Y., Wu X., Nie L., Fan W., Wang Z., Chen Z., Yin H., Han X. Molecular characterization, antibiotic resistance, and biofilm formation of Escherichia coli isolated from commercial broilers from four Chinese provinces. Microorganisms. 2025;13 doi: 10.3390/microorganisms13051017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shoaib M., Gul S., Majeed S., He Z., Hao B., Tang M., Zhang X., Wu Z., Wang S., Pu W. Pathogenomic characterization of multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli strains carrying wide efflux-associated and virulence genes from the dairy farm environment in Xinjiang, China. Antibiotics (Basel) 2025;14 doi: 10.3390/antibiotics14050511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gaeta N.C., Bean E., Miles A.M., Carvalho D.U.O.G.d., Alemán M.A.R., Carvalho J.S., Gregory L., Ganda E. A cross-sectional study of dairy cattle metagenomes reveals increased antimicrobial resistance in animals farmed in a heavy metal contaminated environment. Front. Microbiol. 2020;11 - 2020 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.590325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ibekwe A.M., Bhattacharjee A.S., Phan D., Ashworth D., Schmidt M.P., Murinda S.E., Obayiuwana A., Murry M.A., Schwartz G., Lundquist T., Ma J., Karathia H., Fanelli B., Hasan N.A., Yang C.H. Potential reservoirs of antimicrobial resistance in livestock waste and treated wastewater that can be disseminated to agricultural land. Sci. Total Environ. 2023;872 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.162194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mpongwana N., Kumari S., Rawat I., Zungu P.V., Bux F. The potential ecological risk of co and cross-selection resistance between disinfectant and antibiotic in dairy farms. Environ. Adv. 2024;17 doi: 10.1016/j.envadv.2024.100588. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Savin M., Bierbaum G., Hammerl J.A., Heinemann C., Parcina M., Sib E., Voigt A., Kreyenschmidt J. Antibiotic-resistant bacteria and antimicrobial residues in wastewater and process water from German pig slaughterhouses and their receiving municipal wastewater treatment plants. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;727 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anh H.Q., Le T.P.Q., Da Le N., Lu X.X., Duong T.T., Garnier J., Rochelle-Newall E., Zhang S., Oh N.H., Oeurng C., Ekkawatpanit C., Nguyen T.D., Nguyen Q.T., Nguyen T.D., Nguyen T.N., Tran T.L., Kunisue T., Tanoue R., Takahashi S., Minh T.B., Le H.T., Pham T.N.M., Nguyen T.A.H. Antibiotics in surface water of East and Southeast Asian countries: a focused review on contamination status, pollution sources, potential risks, and future perspectives. Sci. Total Environ. 2021;764 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.142865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu C., Liu Y., Feng C., Wang P., Yu L., Liu D., Sun S., Wang F. Distribution characteristics and potential risks of heavy metals and antimicrobial resistant Escherichia coli in dairy farm wastewater in Tai'an, China. Chemosphere. 2021;262 doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2020.127768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang K., Xin R., Zhao Z., Ma Y., Zhang Y., Niu Z. Antibiotic resistance genes in drinking water of China: occurrence, distribution and influencing factors. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2020;188 doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2019.109837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.García J., García-Galán M.J., Day J.W., Boopathy R., White J.R., Wallace S., Hunter R.G. A review of emerging organic contaminants (EOCs), antibiotic resistant bacteria (ARB), and antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) in the environment: increasing removal with wetlands and reducing environmental impacts. Bioresour. Technol. 2020;307 doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2020.123228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nadimpalli M.L., Marks S.J., Montealegre M.C., Gilman R.H., Pajuelo M.J., Saito M., Tsukayama P., Njenga S.M., Kiiru J., Swarthout J., Islam M.A., Julian T.R., Pickering A.J. Urban informal settlements as hotspots of antimicrobial resistance and the need to curb environmental transmission. Nat. Microbiol. 2020;5:787–795. doi: 10.1038/s41564-020-0722-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Swift B.M.C., Bennett M., Waller K., Dodd C., Murray A., Gomes R.L., Humphreys B., Hobman J.L., Jones M.A., Whitlock S.E., Mitchell L.J., Lennon R.J., Arnold K.E. Anthropogenic environmental drivers of antimicrobial resistance in wildlife. Sci. Total Environ. 2019;649:12–20. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.08.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee K.S., Jeong Y.J., Lee M.S. Escherichia coli Shiga toxins and gut microbiota interactions. Toxins (Basel) 2021;13 doi: 10.3390/toxins13060416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mansour S., Asrar T., Elhenawy W. The multifaceted virulence of adherent-invasive Escherichia coli. Gut Microbes. 2023;15 doi: 10.1080/19490976.2023.2172669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ju T., Bourrie B.C.T., Forgie A.J., Pepin D.M., Tollenaar S., Sergi C.M., Willing B.P. The gut commensal Escherichia coli aggravates high-fat-diet-induced obesity and insulin resistance in mice. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2023;89 doi: 10.1128/aem.01628-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Riley L.W. Distinguishing pathovars from nonpathovars: Escherichia coli. Microbiol. Spectr. 2020;8 doi: 10.1128/microbiolspec.AME-0014-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pakbin B., Brück W.M., Rossen J.W.A. Virulence factors of enteric pathogenic Escherichia coli: a review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021;22 doi: 10.3390/ijms22189922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ellabaan M.M.H., Munck C., Porse A., Imamovic L., Sommer M.O.A. Forecasting the dissemination of antibiotic resistance genes across bacterial genomes. Nat. Commun. 2021;12:2435. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-22757-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leekitcharoenphon P., Johansson M.H.K., Munk P., Malorny B., Skarżyńska M., Wadepohl K., Moyano G., Hesp A., Veldman K.T., Bossers A., Zając M., Wasyl D., Sanders P., Gonzalez-Zorn B., Brouwer M.S.M., Wagenaar J.A., Heederik D.J.J., Mevius D., Aarestrup F.M. Genomic evolution of antimicrobial resistance in Escherichia coli. Sci. Rep. 2021;11:15108. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-93970-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shoaib M., Tang M., Awan F., Aqib A.I., Hao R., Ahmad S., Wang S., Shang R., Pu W. Genomic characterization of extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL) producing E. coli harboring blaOXA−1-catB3-arr-3 genes isolated from dairy farm environment in China. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2024;2024 doi: 10.1155/2024/3526395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Holcomb D.A., Stewart J.R. Microbial indicators of fecal pollution: recent progress and challenges in assessing water quality. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2020;7:311–324. doi: 10.1007/s40572-020-00278-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Partridge S.R., Kwong S.M., Firth N., Jensen S.O. Mobile genetic elements associated with antimicrobial resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2018;31 doi: 10.1128/cmr.00088-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang S., Abbas M., Rehman M.U., Huang Y., Zhou R., Gong S., Yang H., Chen S., Wang M., Cheng A. Dissemination of antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) via integrons in Escherichia coli: a risk to human health. Environ. Pollut. 2020;266 doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2020.115260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Haenelt S., Wang G., Kasmanas J.C., Musat F., Richnow H.H., da Rocha U.N., Müller J.A., Musat N. The fate of sulfonamide resistance genes and anthropogenic pollution marker intI1 after discharge of wastewater into a pristine river stream. Front. Microbiol. 2023;14 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2023.1058350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pérez-Etayo L., Berzosa M., González D., Vitas A.I. Prevalence of integrons and insertion sequences in ESBL-producing E. coli isolated from different sources in Navarra, Spain. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2018;15 doi: 10.3390/ijerph15102308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pong C.H., Moran R.A., Hall R.M. Evolution of IS26-bounded pseudo-compound transposons carrying the tet(C) tetracycline resistance determinant. Plasmid. 2020;112 doi: 10.1016/j.plasmid.2020.102541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang W., Wei X., Zhu Z., Wu L., Zhu Q., Arbab S., Wang C., Bai Y., Wang Q., Zhang J. Tn3-like structures co-harboring of bla(CTX-M-65), bla(TEM-1) and bla(OXA-10) in the plasmids of two Escherichia coli ST1508 strains originating from dairy cattle in China. BMC Vet. Res. 2023;19:279. doi: 10.1186/s12917-023-03847-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jung H.-R., Lee Y.J., Hong S., Yoon S., Lim S.-K., Lee Y.J. Current status of β-lactam antibiotic use and characterization of β-lactam-resistant Escherichia coli from commercial farms by integrated broiler chicken operations in Korea. Poult. Sci. 2023;102 doi: 10.1016/j.psj.2023.103091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.De Koster S., Ringenier M., Xavier B.B., Lammens C., De Coninck D., De Bruyne K., Mensaert K., Kluytmans-van den Bergh M., Kluytmans J., Dewulf J., Goossens H. Genetic characterization of ESBL-producing and ciprofloxacin-resistant Escherichia coli from Belgian broilers and pigs. Front. Microbiol. 2023;14 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2023.1150470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li M., Li Z., Zhong Q., Liu J., Han G., Li Y., Li C. Antibiotic resistance of fecal carriage of Escherichia coli from pig farms in China: a meta-analysis. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2022;29:22989–23000. doi: 10.1007/s11356-021-17339-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu Z., Wang K., Zhang Y., Xia L., Zhao L., Guo C., Liu X., Qin L., Hao Z. High prevalence and diversity characteristics of bla(NDM), mcr, and bla(ESBLs) harboring multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli from chicken, pig, and cattle in China. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2021;11 doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2021.755545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ji X., Zheng B., Berglund B., Zou H., Sun Q., Chi X., Ottoson J., Li X., Lundborg C.S., Nilsson L.E. Dissemination of extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli carrying mcr-1 among multiple environmental sources in rural China and associated risk to human health. Environ. Pollut. 2019;251:619–627. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2019.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lin H., Wang P., Lu Y., Gao K., Hao H., Tong Z., Li W. Clinical and genomic characteristics of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates from acute pancreatitis with infection in China. Clin. Lab. 2023;69 doi: 10.7754/Clin.Lab.2022.221017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Misumi W., Magome A., Okuhama E., Uchimura E., Tamamura-Andoh Y., Watanabe Y., Kusumoto M. CTX-M-55-type ESBL-producing fluoroquinolone-resistant Escherichia coli sequence type 23 repeatedly caused avian colibacillosis in Kagoshima Prefecture, Japan. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2023;35:325–331. doi: 10.1016/j.jgar.2023.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liao Y.S., Wei H.L., Kuo H.C., Chen B.H., Wang Y.W., Teng R.H., Hong Y.P., Chang J.H., Liang S.Y., Tsao C.S., Chiou C.S. Chromosome-borne CTX-M-65 extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Salmonella enterica Serovar Infantis, Taiwan. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2023;29:1634–1637. doi: 10.3201/eid2908.230472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cameron A., Mangat R., Mostafa H.H., Taffner S., Wang J., Dumyati G., Stanton R.A., Daniels J.B., Campbell D., Lutgring J.D., Pecora N.D. Detection of CTX-M-27 β-lactamase genes on two distinct plasmid types in ST38 Escherichia coli from three U.S. states. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2021;65 doi: 10.1128/aac.00825-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shoaib M., Tang M., Aqib A.I., Zhang X., Wu Z., Wen Y., Hou X., Xu J., Hao R., Wang S., Pu W. Dairy farm waste: a potential reservoir of diverse antibiotic resistance and virulence genes in aminoglycoside- and beta-lactam-resistant Escherichia coli in Gansu Province, China. Environ. Res. 2024;263 doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2024.120190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hammad A.M., Gonzalez-Escalona N., El Tahan A., Abbas N.H., Koenig S.S.K., Allué-Guardia A., Eppinger M., Hoffmann M. Pathogenome comparison and global phylogeny of Escherichia coli ST1485 strains. Sci. Rep. 2022;12:18495. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-20342-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.CLSI, in, 2023.

- 48.Bolger A.M., Lohse M., Usadel B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2114–2120. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bankevich A., Nurk S., Antipov D., Gurevich A.A., Dvorkin M., Kulikov A.S., Lesin V.M., Nikolenko S.I., Pham S., Prjibelski A.D., Pyshkin A.V., Sirotkin A.V., Vyahhi N., Tesler G., Alekseyev M.A., Pevzner P.A. SPAdes: a new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J. Comput. Biol. 2012;19:455–477. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2012.0021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Besemer J., Lomsadze A., Borodovsky M. GeneMarkS: a self-training method for prediction of gene starts in microbial genomes. Implications for finding sequence motifs in regulatory regions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:2607–2618. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.12.2607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Galperin M.Y., Makarova K.S., Wolf Y.I., Koonin E.V. Expanded microbial genome coverage and improved protein family annotation in the COG database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:D261–D269. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Florensa A.F., Kaas R.S., Clausen P., Aytan-Aktug D., Aarestrup F.M. ResFinder - an open online resource for identification of antimicrobial resistance genes in next-generation sequencing data and prediction of phenotypes from genotypes. Microb. Genom. 2022;8 doi: 10.1099/mgen.0.000748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Carattoli A., Zankari E., García-Fernández A., Voldby Larsen M., Lund O., Villa L., Møller Aarestrup F., Hasman H. In silico detection and typing of plasmids using PlasmidFinder and plasmid multilocus sequence typing. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2014;58:3895–3903. doi: 10.1128/aac.02412-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Siguier P., Perochon J., Lestrade L., Mahillon J., Chandler M. ISfinder: the reference centre for bacterial insertion sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:D32–D36. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chen L., Yang J., Yu J., Yao Z., Sun L., Shen Y., Jin Q. VFDB: a reference database for bacterial virulence factors. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:D325–D328. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Camacho C., Coulouris G., Avagyan V., Ma N., Papadopoulos J., Bealer K., Madden T.L. BLAST+: architecture and applications. BMC Bioinforma. 2009;10:421. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gelalcha B.D., Ensermu D.B., Agga G.E., Vancuren M., Gillespie B.E., D’Souza D.H., Okafor C.C., Kerro Dego O. Prevalence of antimicrobial resistant and extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli in dairy cattle farms in East Tennessee. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2022;19:408–416. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2021.0101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bezabih Y.M., Sabiiti W., Alamneh E., Bezabih A., Peterson G.M., Bezabhe W.M., Roujeinikova A. The global prevalence and trend of human intestinal carriage of ESBL-producing Escherichia coli in the community. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2021;76:22–29. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkaa399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yoon S., Lee Y.J. Molecular characteristics of ESBL-producing Escherichia coli isolated from chickens with colibacillosis. J. Vet. Sci. 2022;23 doi: 10.4142/jvs.21105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sultan I., Siddiqui M.T., Gogry F.A., Haq Q.M.R. Molecular characterization of resistance determinants and mobile genetic elements of ESBL producing multidrug-resistant bacteria from freshwater lakes in Kashmir, India. Sci. Total Environ. 2022;827 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.154221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yang M., Liu D., Li X., Xiao C., Mao Y., He J., Feng J., Wang L. Characterizations of blaCTX–M–14 and blaCTX–M–64 in a clinical isolate of Escherichia coli from China. Front. Microbiol. 2023;14 - 2023 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2023.1158659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tong P., Sun Y., Ji X., Du X., Guo X., Liu J., Zhu L., Zhou B., Zhou W., Liu G., Feng S. Characterization of antimicrobial resistance and extended-spectrum β-lactamase genes in Escherichia coli isolated from chickens. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2015;12:345–352. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2014.1857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhang W.-H., Ren S.-Q., Gu X.-X., Li W., Yang L., Zeng Z.-L., Liu Y.-H., Jiang H.-X. High frequency of virulence genes among Escherichia coli with the blaCTX-M genotype from diarrheic piglets in China. Vet. Microbiol. 2015;180:260–267. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2015.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Li R., Lu X., Munir A., Abdullah S., Liu Y., Xiao X., Wang Z., Mohsin M. Widespread prevalence and molecular epidemiology of tet(X4) and mcr-1 harboring Escherichia coli isolated from chickens in Pakistan. Sci. Total Environ. 2022;806 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.150689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhang W., Lu X., Chen S., Liu Y., Peng D., Wang Z., Li R. Molecular epidemiology and population genomics of tet(X4), bla(NDM) or mcr-1 positive Escherichia coli from migratory birds in southeast coast of China. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2022;244 doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2022.114032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Shikov A.E., Savina I.A., Nizhnikov A.A., Antonets K.S. Recombination in bacterial genomes: evolutionary trends. Toxins. 2023;15:568. doi: 10.3390/toxins15090568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Horne T., Orr V.T., Hall J.P. How do interactions between mobile genetic elements affect horizontal gene transfer? Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2023;73 doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2023.102282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Che Y., Yang Y., Xu X., Břinda K., Polz M.F., Hanage W.P., Zhang T. Conjugative plasmids interact with insertion sequences to shape the horizontal transfer of antimicrobial resistance genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2021;118 doi: 10.1073/pnas.2008731118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Brkljacic J., Wittler B., Lindsey B.E., III, Ganeshan V.D., Sovic M.G., Niehaus J., Ajibola W., Bachle S.M., Fehér T., Somers D.E. Frequency, composition and mobility of Escherichia coli-derived transposable elements in holdings of plasmid repositories. Microb. Biotechnol. 2022;15:455–468. doi: 10.1111/1751-7915.13962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yao Y., Maddamsetti R., Weiss A., Ha Y., Wang T., Wang S., You L. Intra- and interpopulation transposition of mobile genetic elements driven by antibiotic selection. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2022;6:555–564. doi: 10.1038/s41559-022-01705-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Townsend S.M., Kramer N.E., Edwards R., Baker S., Hamlin N., Simmonds M., Stevens K., Maloy S., Parkhill J., Dougan G., Bäumler A.J. Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi possesses a unique repertoire of fimbrial gene sequences. Infect. Immun. 2001;69:2894–2901. doi: 10.1128/iai.69.5.2894-2901.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Carramaschi I.N., de C.Q.M.M., da Mota F.F., Zahner V. First identification of bla (NDM-1) producing Escherichia coli ST 9499 isolated from Musca domestica in the urban center of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Curr. Microbiol. 2023;80:278. doi: 10.1007/s00284-023-03393-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Redondo-Salvo S., Fernández-López R., Ruiz R., Vielva L., de Toro M., Rocha E.P.C., Garcillán-Barcia M.P., de la Cruz F. Pathways for horizontal gene transfer in bacteria revealed by a global map of their plasmids. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:3602. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-17278-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Baquero F., Coque T.M., Martínez J.L., Aracil-Gisbert S., Lanza V.F. Gene transmission in the one health microbiosphere and the channels of antimicrobial resistance. Front. Microbiol. 2019;10:2892. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.02892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

SNP matrix of E. coli ZYX8158 and ZYS8091 with E. coli pathotypes.

Allele differences and metadata of E. coli (ZYX8158) ST10 clone with other strains from the database.

Allele differences and metadata of E. coli (ZYS8091) ST2325 clone with other strains from the database.

Data Availability Statement

The whole genome sequence data of E. coli ZYX8158 and ZYS8091 have been deposited in NCBI under BioSample IDs SAMN41582031 and SAMN41581077, respectively.